Over-Prescription of Antibiotics for Pulpitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Surveys

Abstract

1. Introduction

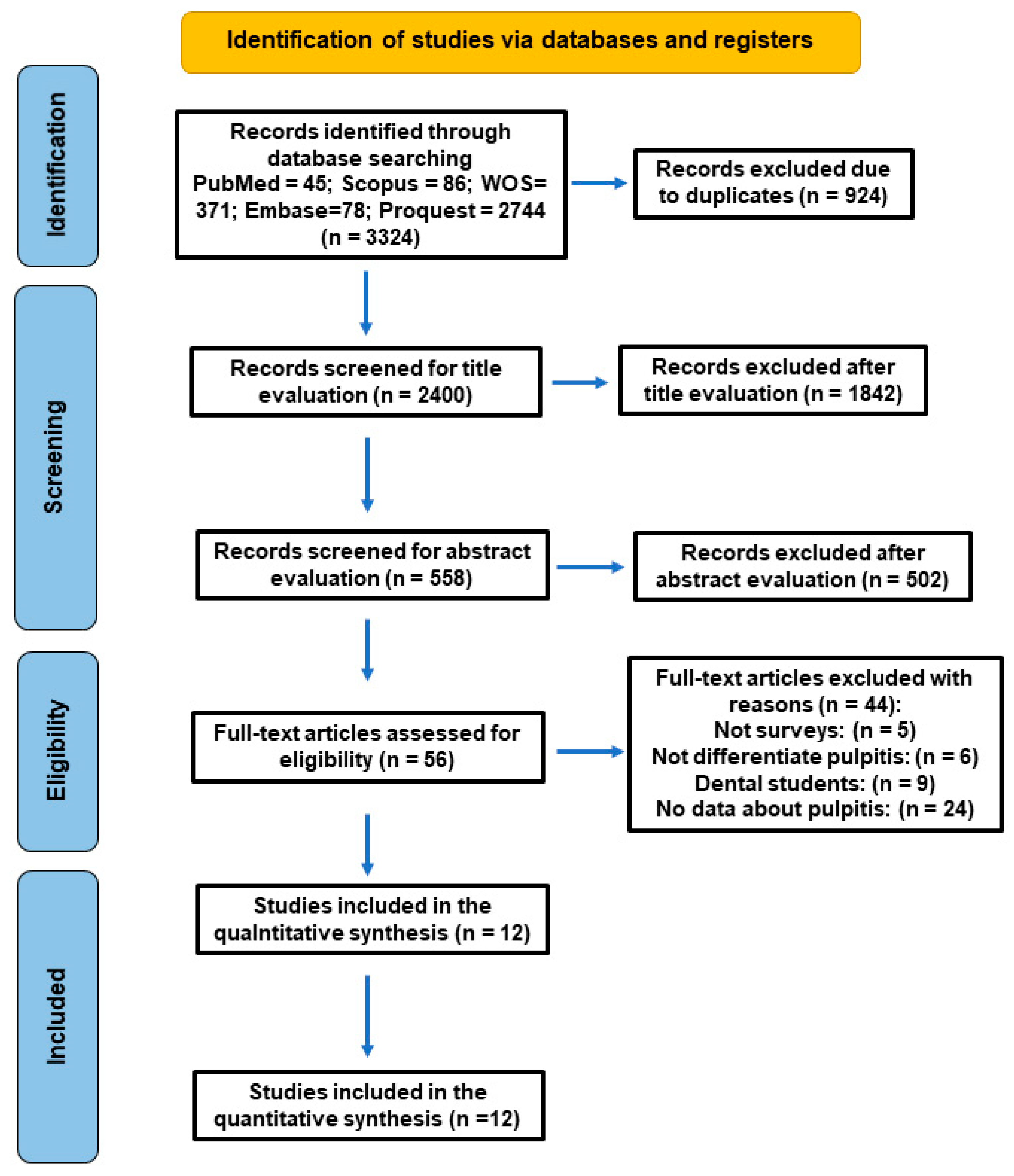

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Question

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy and Information Sources

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Certainty of Evidence (GRADE Assessment)

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. Pattern of Antibiotic Prescription in Pulpitis

3.3. Meta-Analysis of Antibiotic Prescription for Pulpitis by Dentists

3.4. Meta-Analysis of Antibiotic Prescription for Pulpitis by Dental General Practitioners

3.5. Meta-Analysis of Antibiotic Prescription for Pulpitis by Endodontists

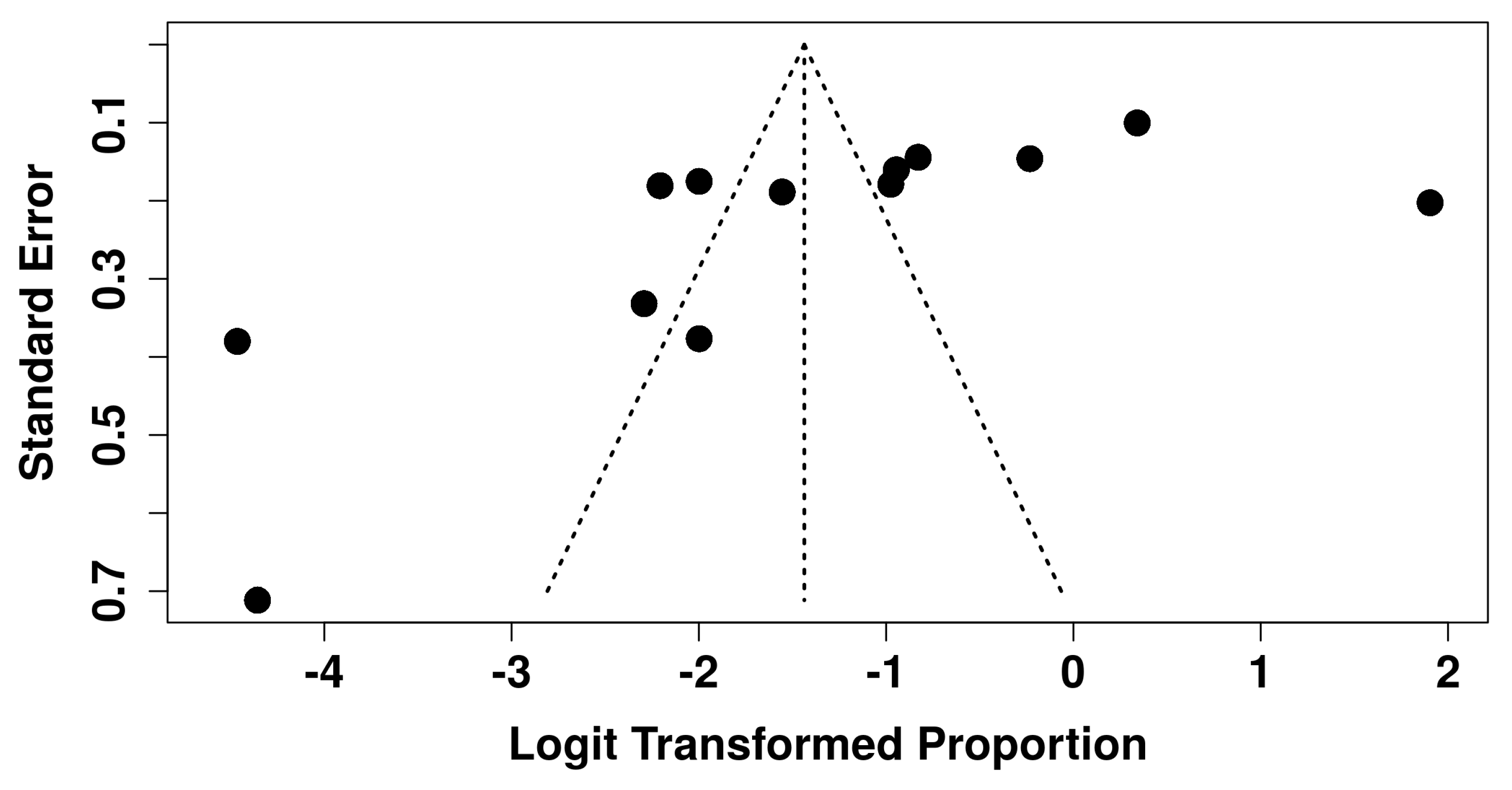

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis and Publication Bias

3.7. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.8. GRADE Assessment of Evidence Quality

4. Discussion

4.1. Consistency of the Findings

4.2. Factors Explaining the Variability

4.3. Clinical Implications

4.4. Limitations of the Evidence

4.5. Future Directions

4.6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, L.; Lin, C.; Chen, Z.; Yue, L.; Yu, Q.; Hou, B.; Ling, J.; Liang, J.; Wei, X.; Chen, W.; et al. Expert Consensus on Pulpotomy in the Management of Mature Permanent Teeth with Pulpitis. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2025, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, P.B.; Tampi, M.P.; Abt, E.; Aminoshariae, A.; Durkin, M.J.; Fouad, A.F.; Gopal, P.; Hatten, B.W.; Kennedy, E.; Lang, M.S.; et al. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline on Antibiotic Use for the Urgent Management of Pulpal- and Periapical-Related Dental Pain and Intraoral Swelling: A Report from the American Dental Association. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 150, 906–921.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Gould, K.; Şen, B.H.; Jonasson, P.; Cotti, E.; Mazzoni, A.; Sunay, H.; Tjäderhane, L.; Dummer, P.M.H. European Society of Endodontology Position Statement: The Use of Antibiotics in Endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Domínguez, L.; López-Marrufo-Medina, A.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M.C.; Areal-Quecuty, V.; López-López, J.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Martin-González, J. Antibiotics Prescription by Spanish General Practitioners in Primary Dental Care. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnihotry, A.; Gill, K.S.; Stevenson, R.G.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Kumar, V.; Sprakel, J.; Cohen, S.; Thompson, W. Irreversi Bl e Pulpitis—A Source of Antibiotic over-Prescription? Braz. Dent. J. 2019, 30, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskin, E.; Veitz-Keenan, A. Antibiotics Are Not Useful to Reduce Pain Associated with Irreversible Pulpitis. Evid. Based Dent. 2016, 17, 81–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Martín-González, J.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M.d.C.; Crespo-Gallardo, I.; Saúco-Márquez, J.J.; Velasco-Ortega, E. Worldwide Pattern of Antibiotic Prescription in Endodontic Infections. Int. Dent. J. 2017, 67, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Vázquez-Cancela, O.; Piñeiro-Lamas, M.; Herdeiro, M.T.; Figueiras, A.; Zapata-Cachafeiro, M. Magnitude and Determinants of Inappropriate Prescribing of Antibiotics in Dentistry: A Nation-Wide Study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2023, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marra, F.; George, D.; Chong, M.; Sutherland, S.; Patrick, D.M. Antibiotic Prescribing by Dentists Has Increased. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2016, 147, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Millán, J.A.; León-López, M.; Martín-González, J.; Saúco-Márquez, J.J.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Segura-Egea, J.J. Antibiotic Over-Prescription by Dentists in the Treatment of Apical Periodontitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Smith, E.G.; Suda, K.J.; Lew, D.; Rowan, S.; Hanna, D.; Bach, T.; Shimpi, N.; Foraker, R.E.; Durkin, M.J. How Decisions Are Made: Antibiotic Stewardship in Dentistry. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2023, 44, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banjar, A.A. Dentists’ Awareness of Antibiotic Stewardship and Their Willingness to Support Its Implementation: A Cross-Sectional Survey in a Dental School. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2025, 31, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, S.B.; Abdulla, N.; Himratul-Aznita, W.H.; Awad, M.; Samaranayake, L.P.; Ahmed, H.M.A. Antibiotic Prescribing Practices of Dentists for Endodontic Infections; a Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; MClinSc, S.M.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological Guidance for Systematic Reviews of Observational Epidemiological Studies Reporting Prevalence and Cumulative Incidence Data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of Endodontists. Glossary of Endodontic Terms; American Association of Endodontists: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020; Volume 9, p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.S.; Velasco-Ortega, E.; Torres-Lagares, D.; Velasco-Ponferrada, M.C.; Monsalve-Guil, L.; Llamas-Carreras, J.M. Pattern of Antibiotic Prescription in the Management of Endodontic Infections amongst Spanish Oral Surgeons. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20487455 (accessed on 9 April 2016).

- Whitten, B.H.; Gardiner, D.L.; Jeansonne, B.G.; Lemon, R.R. Current Trends in Endodontic Treatment: Report of a National Survey. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1996, 127, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salako, N.O.; Rotimi, V.O.; Adib, S.M.; Al-Mutawa, S. Pattern of Antibiotic Prescription in the Management of Oral Diseases among Dentists in Kuwait. J. Dent. 2004, 32, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.P.; Kaushik, M.; Kumar, P.U.; Reddy, M.S.; Prashar, N. Antibiotic Prescribing Habits of Dental Surgeons in Hyderabad City, India, for Pulpal and Periapical Pathologies: A Survey. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 2013, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, B.C.; Dahabreh, I.J.; Trikalinos, T.A.; Lau, J.; Trow, P.; Schmid, C.H. Closing the Gap between Methodologists and End-Users: R as a Computational Back-End. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 49, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying Heterogeneity in a Meta-Analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, R.; Álvarez-Pasquin, M.J.; Díaz, C.; Del Barrio, J.L.; Estrada, J.M.; Gil, Á. Are Healthcare Workers Intentions to Vaccinate Related to Their Knowledge, Beliefs and Attitudes? A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, D.; Brooks, P.; Woolf, A.; Blyth, F.; March, L.; Bain, C.; Baker, P.; Smith, E.; Buchbinder, R. Assessing Risk of Bias in Prevalence Studies: Modification of an Existing Tool and Evidence of Interrater Agreement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modesti, P.A.; Reboldi, G.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Agyemang, C.; Remuzzi, G.; Rapi, S.; Perruolo, E.; Parati, G.; Agostoni, P.; Barros, H.; et al. Panethnic Differences in Blood Pressure in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Montori, V.; Akl, E.A.; Djulbegovic, B.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; et al. GRADE Guidelines: 4. Rating the Quality of Evidence—Study Limitations (Risk of Bias). J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultcrantz, M.; Rind, D.; Akl, E.A.; Treweek, S.; Mustafa, R.A.; Iorio, A.; Alper, B.S.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Murad, M.H.; Ansari, M.T.; et al. The GRADE Working Group Clarifies the Construct of Certainty of Evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 87, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alattas, H.A.; Alyami, S.H. Prescription of Antibiotics for Pulpal and Periapical Pathology among Dentists in Southern Saudi Arabia. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2017, 9, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, H.; Naved, N.; Khan, S.A.; Jabeen, S.F.; Raza, S.S.; Khalid, T. Evaluation of Dentists’ Clinical Practices and Antibiotic Use in Managing Endodontic Emergencies in Karachi, Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, N.M.; Moreno, J.O.; Alves, F.R.; Gonçalves, L.S.; Provenzano, J.C. Antibiotic Indication in Endodontics by Colombian Dentists with Different Levels of Training: A Survey. Acta Odontol. Latinoam. 2022, 35, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Ezpeleta, O.; Martín-Jiménez, M.; Martín-Biedma, B.; López-López, J.; Forner-Navarro, L.; Martín-González, J.; Montero-Miralles, P.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M.D.C.; Velasco-Ortega, E.; Segura-Egea, J.J. Use of Antibiotics by Spanish Dentists Receiving Postgraduate Training in Endodontics. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2018, 10, e687–e695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar, P.; Virda, M.; Haider, A.; Alamgir, W.; Afzal, M.; Ahmad Khan, R.M. An Evaluation of Antibiotic Prescribing Practices among Dentists in Lahore: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pakistan J. Health Sci. 2022, 3, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolfoni, M.R.; Pappen, F.G.; Pereira-Cenci, T.; Jacinto, R.C. Antibiotic Prescription for Endodontic Infections: A Survey of Brazilian Endodontists. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobac, M.; Otasevic, K.; Ramic, B.; Cvjeticanin, M.; Stojanac, I.; Petrovic, L. Antibiotic Prescribing Practices in Endodontic Infections: A Survey of Dentists in Serbia. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, A. The Attitudes of Dentists Towards the Prescription of Antibiotics During Endodontic Treatment in North of Saudi Arabia. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, ZC82–ZC84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslamani, M.; Sedeqi, F. Antibiotic and Analgesic Prescription Patterns among Dentists or Management of Dental Pain and Infection during Endodontic Treatment. Med. Princ. Pract. 2018, 27, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengari, L.; Mandorah, A.; Bandahdha, R. Knowledge and Practice of Antibiotic Prescription Among Dentists for Endodontic Emergencies. J. Res. Med. Dent. Sci. 2020, 8, 6–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ozmen, E.E.; Sahin, T.N. Antibiotic Use in Pediatric Dental Infections: Knowledge and Awareness Levels of Dentists. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, D.B.; Durkin, M.J.; Gibson, G.; Jurasic, M.M.; Patel, U.; Poggensee, L.; Fitzpatrick, M.A.; Echevarria, K.; McGregor, J.; Evans, C.T.; et al. Concordance of Antibiotic Prescribing with the American Dental Association Acute Oral Infection Guidelines within Veterans’ Affairs (VA) Dentistry. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2021, 42, 1422–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar-Odeh, N.S.; Abu-Hammad, O.A.; Al-Omiri, M.K.; Khraisat, A.S.; Shehabi, A.A. Antibiotic Prescribing Practices by Dentists: A Review. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2010, 6, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotry, A.; Thompson, W.; Fedorowicz, Z.; van Zuuren, E.J.; Sprakel, J. Antibiotic Use for Irreversible Pulpitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 5, CD004969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khijmatgar, S.; Bellucci, G.; Creminelli, L.; Tartaglia, G.M.; Tumedei, M. Systemic Antibiotic Use in Acute Irreversible Pulpitis: Evaluating Clinical Practices and Molecular Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teoh, L.; Marino, R.J.; Stewart, K.; McCullough, M.J. A Survey of Prescribing Practices by General Dentists in Australia. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Zarza-Rebollo, A.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M.C.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Areal-Quecuty, V.; Martín-González, J. Evaluation of Undergraduate Endodontic Teaching in Dental Schools within Spain. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; León-lópez, M.; Cabanillas-balsera, D.; Sauco-márquez, J.J.; Martin-gonzalez, J. Undergraduate Endodontic Teaching in Dental Schools Around the World: A Narrative Review. Eur. Endod. J. 2025, 10, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, I.; Reed, D.; Brennan, A.M.; Eaton, K.A. An Investigation into Possible Factors That May Impact on the Potential for Inappropriate Prescriptions of Antibiotics: A Survey of General Dental Practitioners’ Approach to Treating Adults with Acute Dental Pain. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamszadeh, S.; Asgary, S.; Shirvani, A.; Eghbal, M.J. Effects of Antibiotic Administration on Post-Operative Endodontic Symptoms in Patients with Pulpal Necrosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021, 48, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Marrufo-Medina, A.; Domínguez-Domínguez, L.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Areal-Quecuty, V.; Crespo-Gallardo, I.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M.C.; López-López, J.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Martin-Gonzalez, J. Antibiotics Prescription Habits of Spanish Endodontists: Impact of the ESE Awareness Campaign and Position Statement. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2022, 14, e48–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doshi, A.; Asawa, K.; Bhat, N.; Tak, M.; Dutta, P.; Bansal, T.K.; Gupta, R. Knowledge and Practices of Indian Dental Students Regarding the Prescription of Antibiotics and Analgesics. Clujul Med. 2017, 90, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, M.; Audino, E.; Venturi, G.; Garo, M.L.; Salgarello, S. Antibiotic Prescribing for Endodontic Infections: A Survey of Dental Students in Italy. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-González, J.; Echevarría-Pérez, M.; Sánchez-Domínguez, B.; Tarilonte-Delgado, M.L.; Castellanos-Cosano, L.; López-Frías, F.J.; Segura-Egea, J.J. Influence of Root Canal Instrumentation and Obturation Techniques on Intra-Operative Pain During Endodontic Therapy. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2012, 17, e912-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Exact Search String Used | No. of Articles | Date of Last Search |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed/ MEDLINE | (pulpitis[MeSH Terms] OR pulpitis[Title/Abstract] OR “irreversible pulpitis”[Title/Abstract]) AND (antibiotic*[Title/Abstract] OR antimicrobial*[Title/Abstract] OR “anti-bacterial agents”[MeSH Terms]) AND (prescribing[Title/Abstract] OR prescription*[Title/Abstract] OR “inappropriate use”[Title/Abstract] OR “overprescription”[Title/Abstract] OR misuse[Title/Abstract]) AND (dentist*[Title/Abstract] OR “dental practitioner*”[Title/Abstract] OR “general dental practitioner*”[Title/Abstract] OR endodontist*[Title/Abstract]) | 45 | From 2015 to 5 November 2025 |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY(pulpitis) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“irreversible pulpitis”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY(antibiotic*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(antimicrobial*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“anti-bacterial agents”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY(prescribing) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(prescription*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“inappropriate use”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(overprescription) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(misuse)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY(dentist*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“dental practitioner*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“general dental practitioner*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(endodontist*)) | 86 | From 2015 to 5 November 2025 |

| Web of Science | (pulpitis OR dental infection) AND (antibiotic OR antimicrobial) AND (prescribing OR prescription) AND (dentist* OR “dental practitioner*” OR “general dental practitioner*” OR endodontist*) | 371 | From 2015 to 5 November 2025 |

| EMBASE | (‘pulpitis’/exp OR pulpitis:ti,ab,kw OR “irreversible pulpitis”:ti,ab,kw) AND (antibiotic*:ti,ab,kw OR antimicrobial*:ti,ab,kw OR ‘antibacterial agent’/exp OR “anti-bacterial agent*”:ti,ab,kw) AND (prescribing:ti,ab,kw OR prescription*:ti,ab,kw OR “inappropriate use”:ti,ab,kw OR overprescription:ti,ab,kw OR misuse:ti,ab,kw) AND (dentist*:ti,ab,kw OR (dental NEXT/1 practitioner*):ti,ab,kw OR (general NEXT/1 dental NEXT/1 practitioner*):ti,ab,kw OR endodontist*:ti,ab,kw OR ‘dentist’/exp OR ‘endodontist’/exp) | 78 | From 2015 to 5 November 2025 |

| ProQuest (Grey Literature) | (pulpitis OR dental infection) AND (antibiotic OR antimicrobial) AND (prescribing OR prescription) AND (dentist* OR “dental practitioner*” OR “general dental practitioner*” OR endodontist*) | 2749 | From 2015 to 5 November 2025 |

| Domain 1: Sample Selection and Representativeness |

| 1. Representativeness of the sample: the sample is truly representative of the target population (e.g., national or regional random sample, or all eligible participants included). |

| 2. Sampling frame and selection method: sampling frame is appropriate (e.g., registry, professional association list) and participants are selected randomly or systematically. |

| 3. Sample size justification: sample size is adequately calculated and justified based on expected prevalence or precision level. |

| 4. Non-response bias: response rate ≥ 70%, or analysis demonstrates no significant difference between respondents and non-respondents. |

| Domain 2: Measurement and Data Collection |

| 5. Case/phenomenon definition: the variable of interest (e.g., antibiotic prescription for a specific condition) is clearly defined and consistent across participants. |

| 6. Measurement tool validity: data are collected using validated or standardized instruments (questionnaire, clinical record, or national survey form). |

| 7. Consistency of data collection: the same data collection methods and definitions are applied to all participants. |

| 8. Statistical analysis: appropriate descriptive and inferential analyses are performed, including 95% confidence intervals for prevalence estimates. |

| Reasons | Excluded Studies |

|---|---|

| Studies that did not provide survey data but instead used clinical records or hospital registries (n = 5). | Al Asmar et al., 2020 Carlsen et al., 2021 Di Giuseppe et al., 2021 Lalloo et al., 2017 Tanwir et al., 2015 |

| Studies that did not differentiate pulpitis from other endodontic pathologies (n = 6). | Baudet et al 2020 Bidar et al., 2015 Gemmell et al 2020 Hamdan et al., 2024 Joji et al., 2024 Khijmatgar et al., 2024 |

| Studies conducted on dental students rather than licensed dentists (n = 9). | Arıcan, 2021 Careddu & Duncan, 2021 Danadneh, 2025 Doshi, 2017 Kumar Giri, 2025 Madarati, 2018 Salvadori, 2019 Schneider-Smith, 2023 Strużycka, 2019 |

| Studies without percentages of antibiotic prescription for pulpitis (n = 24). | Abdellatif, 2025 Ahsan, 2020 Alzahrani, 2020 Bjelovucic, 2019 Buttar, 2017 Edwards, 2024 Goff, 2022 Jain, 2015 Kalantzis, 2024 Khalab, 2024 Khalil, 2022 Kusumoto, 2021 López-Marrufo-Medina et al., 2022 Mathur, 2023 Peric et al., 2015 Roberts, 2018 Robles Raya, 2017 Rodríguez-Fernández, 2023 Shemesh, 2022 Simon, 2023 Sovic, 2024 Sturrock, 2018 Vengidesh et al., 2024 Yu et al., 2020 |

| Authors & Year | Country | Prescriber | Total Sample | Percentage of Respondents | Diagnosis of Pulpitis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alattas & Alyami 2017 [29] | Saudi Arabia | GDP | 200 | 98.0 | Clinical diagnostic criteria through signs and symptoms |

| Alonso-Ezpeleta et al. 2018 [32] | Spain | EN | 73 | 91.0 | Clinical diagnostic criteria through signs and symptoms |

| Babar et al. 2022 [33] | Pakistan | GDP | 216 | 100 | Clinical diagnostic criteria through signs and symptoms |

| Bolfoni et al. 2018 [34] | Brazil | EN | 13,853 | 4.4 | Clinical diagnostic criteria through signs and symptoms |

| Dias et al. 2022 [31] | Colombia | GDP | 363 | 53.2 | Clinical scenarios containing complete criteria for pulpitis consistent with ESE and AAE guidelines |

| Dias et al. 2022 [31] | Colombia | EN | 196 | 55.6 | |

| Domínguez-Domínguez et al. 2021 [4] | Spain | GDP | 200 | 95.0 | Clinical diagnostic criteria through signs and symptoms |

| Drobac et al. 2021 [35] | Serbia | GDP | 628 | 25.2 | Only mentions pulpitis as a diagnostic label without describing symptoms or signs |

| Iqbal et al. 2015 [36] | Saudi Arabia | GDP | 200 | 78.5 | Clinical scenarios with detailed clinical information that allow diagnosis of pulpitis |

| Maslamani & Sedeqi 2018 [37] | Kuwait | GDP | 300 | 75.6 | Clinical diagnostic criteria through signs and symptoms |

| Mengari et al. 2020 [38] | Saudi Arabia | GDP | 1500 | 22.1 | Only mentions pulpitis as a diagnostic label without describing symptoms or signs. |

| Özmen & Şahin 2024 [39] | Turkey | GDP | 360 | 95.3 | Clinical cases with descriptions of symptoms of pulpitis |

| Yaqoob et al. 2024 [30] | Pakistan | GDP | 527 | 77.6 | Clinical scenarios with detailed clinical information that allow diagnosis of pulpitis |

| Authors & Year | Prescriptors | Respondents | Antibiotics Prescription in Pulpitis (%) | First-Choice Antibiotics | Second-Choice Antibiotics | Antibiotics in Allergic Patients | Duration (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alattas & Alyami 2017 [29] | GDP | 195 | 34 (17.5) | Amoxicillin | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | Clindamycin | Mode 5 |

| Alonso-Ezpeleta et al. 2018 [32] | EN | 67 | 8 (11.9) | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | Amoxicillin | Clindamycin | Mode 7 Mean 6.8 ± 1.2 |

| Babar et al. 2022 [33] | GDP | 216 | 188 (87.0) | Amoxicillin | Metronidazole | Clindamycin | Mode 5 |

| Bolfoni et al. 2018 [34] | EN | 615 | 7 (1.1) | Amoxicillin | Azithromycin | Clindamycin | Mode 7 |

| Dias et al. 2022 [31] | GDP | 193 | 54 (28.0) | Amoxicillin | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | Clindamycin | Mode 7 |

| Dias et al. 2022 [31] | EN | 109 | 10 (9.2) | Amoxicillin | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | Clindamycin | Mode 7 |

| Domínguez-Domínguez et al. 2021 [4] | GDP | 190 | 84 (44.0) | Amoxicillin ± clavulanic acid | Metronidazole | Clindamycin | Range 5–7 Mean 6.2 ± 1.4 |

| Drobac et al. 2021 [35] | GDP | 158 | 2 (1.3) | Amoxicillin | Clindamycin | Clindamycin | Mode 5 |

| Iqbal et al. 2015 [36] | GDP | 157 | 43 (27.3) | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | Amoxicillin | Clindamycin | Not specified |

| Maslamani & Sedeqi 2018 [37] | GDP | 227 | 69 (30.4) | Amoxicillin | Clindamycin | Clindamycin | Range 5–7 |

| Mengari et al. 2020 [38] | GDP | 310 | 37 (11.9) | Amoxicillin | Amoxicillin + Metronidazole | Clindamycin | Range 5–7 |

| Özmen & Şahin 2024 [39] | GDP | 343 | 34 (10.0) | Amoxicillin | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | Clindamycin | Range 5–7 |

| Yaqoob et al. 2024 [30] | GDP | 409 | 239 (58.4) | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | Metronidazole | Clindamycin | Mode ≥5 |

| Study (Author, Year) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Total | Risk of Bias Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alattas & Alyami 2017 [29] | * | * | * | * | * | * | ? | 6 | Moderate | |

| Alonso-Ezpeleta et al. 2018 [32] | * | * | * | * | * | * | ? | 6 | Moderate | |

| Babar et al. 2022 [33] | ? | ? | * | * | 2 | High | ||||

| Bolfoni et al. 2018 [34] | * | * | * | * | * | * | ? | 6 | Moderate | |

| Dias et al. 2022 [31] | ? | ? | * | * | * | ? | 3 | High | ||

| Domínguez-Domínguez et al. 2021 [4] | ? | ? | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | Moderate | |

| Drobac et al. 2021 [35] | ? | ? | * | * | * | * | 4 | High | ||

| Iqbal 2015 [36] | ? | ? | * | * | * | 3 | High | |||

| Maslamani & Sedeqi 2018 [37] | ? | * | * | ? | * | * | * | * | 6 | Moderate |

| Mengari et al. 2020 [38] | ? | ? | * | * | * | * | 4 | High | ||

| Özmen & Şahin 2024 [39] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8 | Low |

| Yaqoob et al. 2024 [30] | ? | ? | * | ? | * | 2 | High | |||

| Total | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 5 | 55 | Moderate |

| GRADE Domain | Judgment | Reason for Downgrade | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of bias | Serious ↓ | Most studies were cross-sectional surveys with methodological limitations; majority judged as moderate to high risk of bias; only one low-risk study. | Downgraded one level. |

| Inconsistency | Very serious ↓↓ | Extreme heterogeneity (I2 = 98%, p < 0.0001); prevalence ranged from ~1% to 87%; heterogeneity unexplained by subgroup analyses. | Downgraded two levels. |

| Indirectness | Serious ↓ | All data based on self-reported practices; diagnosis often not strictly defined; variability in healthcare contexts across countries impacts applicability. | Downgraded one level. |

| Imprecision | Serious ↓ | Wide 95% CI (10.4–32.6%); several studies with small sample sizes or low event numbers. | Downgraded one level. |

| Publication bias | Serious ↓ | Funnel plot suggested asymmetry; Egger’s test significant (p = 0.034); LFK index = +1.55 (minor asymmetry). | Downgraded one level. |

| Overall certainty of evidence | VERY LOW ↓↓↓↓ | Cumulative downgrades across all domains. | The true prevalence may differ substantially from the pooled estimate. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Delgado-Giugni, V.; León-López, M.; Crespo-Gallardo, I.; Saúco-Márquez, J.J.; Montero-Miralles, P.; Martín-González, J.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Segura-Egea, J.J. Over-Prescription of Antibiotics for Pulpitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Surveys. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010013

Delgado-Giugni V, León-López M, Crespo-Gallardo I, Saúco-Márquez JJ, Montero-Miralles P, Martín-González J, Cabanillas-Balsera D, Segura-Egea JJ. Over-Prescription of Antibiotics for Pulpitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Surveys. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelgado-Giugni, Vanessa, María León-López, Isabel Crespo-Gallardo, Juan J. Saúco-Márquez, Paloma Montero-Miralles, Jenifer Martín-González, Daniel Cabanillas-Balsera, and Juan J. Segura-Egea. 2026. "Over-Prescription of Antibiotics for Pulpitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Surveys" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010013

APA StyleDelgado-Giugni, V., León-López, M., Crespo-Gallardo, I., Saúco-Márquez, J. J., Montero-Miralles, P., Martín-González, J., Cabanillas-Balsera, D., & Segura-Egea, J. J. (2026). Over-Prescription of Antibiotics for Pulpitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Surveys. Antibiotics, 15(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010013