Abstract

Background/Objectives: This research was conducted to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of four molecules present in essential oils (thymol, terpinen-4-ol, citral, and E-2-dodecenal), complementing the study with the observation of structural damage caused by the contact of these compounds with microorganisms. Methods: The micro dilution in plates method was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration, using different concentrations of metabolites in contact with the microorganisms. Optical Microscopy was used to observe structural damage in yeasts, while Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was used for bacteria. Results: In determining the minimum inhibitory concentration, very good activity was observed for all microorganisms at concentrations below 500 µg/mL or 0.05% w/w. In microscopic tests, we can observe three consequences of contact with the molecule to a greater or lesser extent. First, there is a clear decrease in the concentration of microorganisms. Second, we observe damage to the cell membrane. Finally, there are structural changes within the cytoplasm. Conclusions: This study demonstrated that the four metabolites possess good antimicrobial activity, in some of the tests they were even very close to the control antibiotics’ activity. Structural observations show that the activity can be explained by several factors. Many essential oils contain some of the molecules used, so their presence in nature could be a marker of antimicrobial activity.

1. Introduction

Throughout history, microbial, viral, or fungal infections have attacked humans [1]; many of them have remained latent and are common or seasonal processes, while in more complicated cases they have ended up becoming pandemics that have caused millions of deaths [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. The most recent pandemic of COVID-19 highlighted the vulnerability we have as a species to microorganisms, causing immediate and long-term effects on physical and mental health, and on the economy of societies [8,9,10,11,12]. In addition, the pandemic caused a mortality ranging from approximately 5.5 million to 18 million deaths, depending on official data or estimates [13,14,15].

Since the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming almost a century ago [16,17], antibiotics have become the preferred therapy in all health systems around the world in the treatment of infections of diverse nature [18,19]. This widespread use of antibiotics has produced a phenomenon of the global resistance of microorganisms [20,21,22,23], significantly reducing the effectiveness of antimicrobial effects and leading pharmaceutical companies to need new effective molecules every day [24,25,26].

Before the discovery of antibiotics, many infections were treated with natural products showing antimicrobial action that contain secondary metabolites such as polyphenols [27,28,29], alkaloids [30,31], terpenes [32,33,34], anthroquinones [35,36], and coumarins [37], among others.

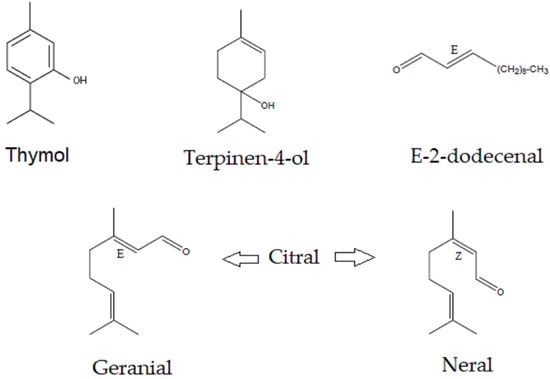

Essential oils are a group of secondary metabolites present in the volatile fraction of various plant organs, whose main components are terpenes (especially monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes) and aromatic compounds (benzene derivatives) [38]. Among the molecules that come from essential oils with a high antimicrobial activity we have thymol [39,40,41], terpinen-4-ol [42,43], citral [44,45,46,47], and E-2-dodecenal [48,49,50].

Thymol is found in several essential oils, the best-known being thyme (Thymus vul-garis) and oregano (Origanum vulgare) [51,52,53], and the antibacterial activity of thymol has been demonstrated in several studies [54], as has its antifungal activity [55,56]. Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) essential oil contains considerable amounts of terpinen-4-ol [57,58], a monoterpene which is also abundant in species such as Juniperus communis [59] and rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus) [60]. Terpinen-4-ol is also a molecule with significant antibacterial activity [61] and antifungal potential [62]. Citral is a mixture of two geometric isomers, neral and geranial [63]. Two plants with a high content of these molecules are Cymbopogon citratus [45] and Aloysia trypylla [64]. Essential oils with high concentrations of citral have been shown to be effective on resistant bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori [65]. Finally, there is the E-2-dodecenal molecule, which is abundant in the Amazonian plant Eryngium foetidum [66], used in digestive disorders; with regard to this molecule, antimicrobial studies are few, but there is a study conducted by Kubo et al. in 2003 [67], which highlights its activity against Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In 2004, the same author verified its good antimicrobial activity against Salmonella sp. [68].

In this study, the antimicrobial activity of each of the mentioned molecules was evaluated against an important number of bacteria and yeasts to corroborate their antibiotic potential; additionally, the damage caused to the microorganism by contact with the molecule was determined by Electron Microscopy.

2. Results

2.1. Antimicrobial Activity

2.1.1. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration in Gram-Positive Bacteria

The results were diverse, depending on the molecule evaluated and the microorganism. The values determined did not exceed 500 µg/mL, meaning that the resulting activity was very good. Table 1 shows the results obtained.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration values in µg/mL in Gram-positive bacteria. Mean ± SD (n = 3), p < 0.05.

2.1.2. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration in Gram-Negative Bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria have a lower sensitivity; however, in the strains evaluated (Proteus vulgaris, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella oxytoca), we can still find very good values of activity below 500 µg/mL. Table 2 describes the antibacterial behavior against Gram-negative bacteria.

Table 2.

Minimum inhibitory concentration values in µg/mL in Gram-negative bacteria. Mean ± SD (n = 3), p < 0.05.

2.1.3. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration in Yeasts

In the case of the two yeasts, both are observed to be very sensitive. Their sensitivity is less than 500 µg/mL, which means that their activity is very good. Table 3 describes the antibacterial behavior of yeasts. (Supplementary Materials detail the procedure for determining the MIC).

Table 3.

Minimum inhibitory concentration values in µg/mL in yeasts. Mean ± SD (n = 3), p < 0.05.

2.2. Structural Damage to Bacteria upon Contact with the Secondary Metabolites

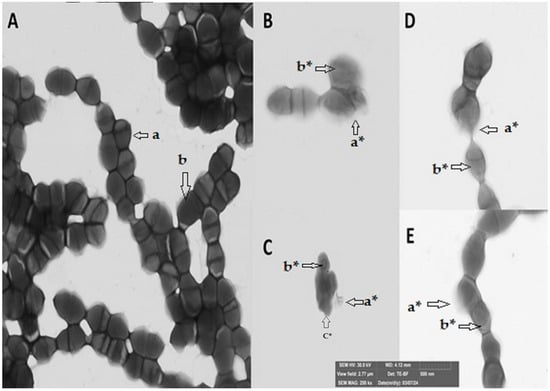

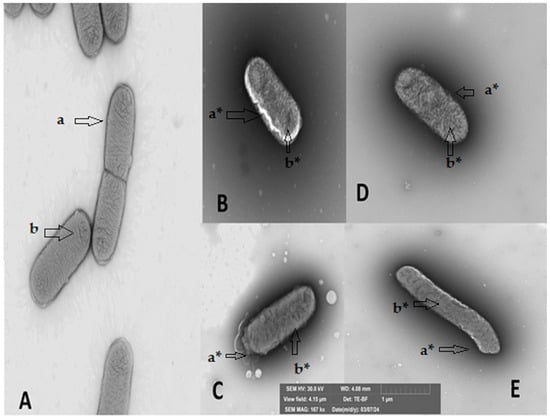

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show what happens when each metabolite comes into contact with bacteria. For this test, a Gram-positive and a Gram-negative bacterium were chosen, taking into account those that had a very satisfactory minimum inhibitory concentration and were easy to grow. The bacteria observed in the study are Streptococcus mutans (ATCC 25175) and Klebsiella oxytoca (ATCC 8724). In both bacteria subjected to the secondary metabolite, it is possible to observe both damage to the cell membrane and the destruction of the interior of the microorganism, which would confirm the activity of the four molecules in inhibiting the growth and proliferation of pathogens.

Figure 1.

Structural damage of the Gram-positive bacterium Streptococcus mutans upon contact with secondary metabolites of essential oils in Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): (A) bacteria without contact with any metabolite, (B) in contact with citral, (C) in contact with E-2-dodecenal, (D) in contact with terpinen-4-ol, and (E) in contact with thymol. a undamaged cell membrane, b undamaged cytoplasm; a* damaged cell membrane, b* damaged cytoplasm, and c* decreased cell size. The arrows indicate the location of the damage caused by the metabolite.

Figure 2.

Structural damage of the Gram-negative bacterium Klebsiella oxytoca upon contact with secondary metabolites of essential oils in Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). (A) Bacteria without contact with any metabolite, (B) in contact with citral, (C) in contact with E-2-dodecenal, (D) in contact with terpinen-4-ol, and (E) in contact with thymol. a undamaged cell membrane, b undamaged cytoplasm; a* damaged cell membrane, and b* damaged cytoplasm. The arrows indicate the location of the damage caused by the metabolite.

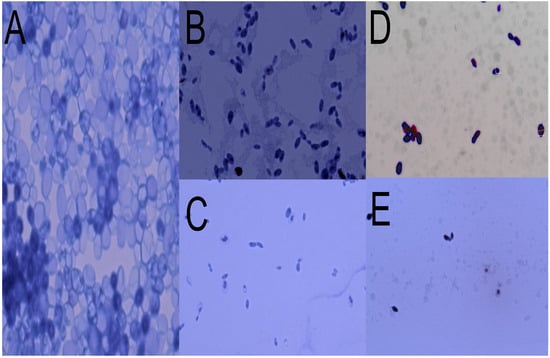

2.3. Structural Damage to Yeast upon Contact with Secondary Metabolites

Figure 3 shows significant damage to the structure of the yeast strain tested, Candida tropicalis ATCC 13803. There is evidence of a decrease in yeast concentration, compaction of cellular material, and disappearance of the microorganism’s membrane. The effects are observable in the four molecules used in this study. (Supplementary Materials show individual photographs of the bacteria in contact with the bioactive molecules).

Figure 3.

Structural damage of the yeast Candida tropicalis upon contact with secondary metabolites of essential oils in Optical Microscopy. (A) Yeast without contact with any metabolite, (B) in contact with citral, (C) in contact with E-2-dodecenal, (D) in contact with terpinen-4-ol, and (E) in contact with thymol.

3. Discussion

Three of the four metabolites (thymol, citral, and terpinen-4-ol) have been studied for their antimicrobial activity.

In the scientific literature, there are several studies on the antimicrobial activity of thymol. One study shows the following MIC values: Staphylococcus aureus from 300 to 600 µg/mL; Escherichia coli from 310 to 5000 µg/mL; and Lactobacillus sp. from 5000 to 10,000 µg/mL [44]. A more extensive study presented by Falcone et al. in 2005 yielded the following MIC values: Bacillus cereus 327 µg/mL; Bacillus subtilis 422 µg/mL; Bacillus licheniformis 422 µg/mL; Lactobacillus curvatus 743 µg/mL; Lactobacillus plantarum 941 µg/mL; Candida lusitaniae 307 µg/mL; Pichia subpelliculosa 422 µg/mL; and Saccharomyces cerevisiae 337 µg/mL [69]. Guarda et al., 2011, obtained the following values: Staphylococcus aureus 250 μg/mL; Listeria innocua 250 μg/mL; Escherichia coli 250 μg/mL; Saccharomyces cerevisiae 125 μg/mL, and Aspergillus niger 250 μg/mL [70]. Finally, Sim et al., 2019, determined the following MIC values: Pseudomonas aeruginosa 400–800 µg/mL; Streptococcus sp. 200 µg/mL; Proteus mirabilis 200 µg/mL; and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius 100–200 µg/mL [71].

With regard to the antimicrobial activity of essential oils with high concentrations of thymol, Thymus pulegoides (24% thymol) has the following results: Streptococcus pyogenes 1250 µg/mL; Staphylococcus aureus 1250 µg/mL; Escherichia coli 5000 µg/mL; Salmonella typhimurium 10,000 µg/mL; Pseudomonas aeruginosa 20,000 µg/mL; Candida albicans 1250 µg/mL; and Candida parapsilosis 1250 µg/mL [72]. For Oregano vulgaris (19% thymol), the following values are obtained: Bordetella bronchiseptica 60–125 µg/mL; Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 125 µg/mL; Escherichia coli 500 µg/mL; and Candida albicans 1000 µg/mL [73]. The MIC values for thymol are quite similar to those obtained in this study, while the antimicrobial activity of essential oils is lower.

The terpinen-4-ol molecule has been shown to be active against Enterococcus faecalis with an MIC of 2500 µg/mL and Fusobacterium nucleatum 500 µg/mL [74]; another study supports its effectiveness against Streptococcus agalactiae with an MIC value of 98.94 µg/mL [62]. A study conducted by Noumi et al. determined activity against Chromobacterium violaceum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa with MIC values close to 50 µg/mL [75]. Finally, antifungal activity was confirmed in Coccidioides posadasii 350–5720 µg/mL and Histoplasma capsulatum 10–5720 µg/mL [76].

Antimicrobial activity studies conducted on Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil and terpinen-4-ol show the following MIC values: S. aureus tea tree 5000 µg/mL; terpinen-4-ol 2500 µg/mL; E. coli tea tree 2500–5000 µg/mL; and terpinen 4-ol 1200–2500 µg/mL, with greater activity observed in the pure molecule [77].

A study on essential oil containing 31% terpinen-4-ol verified its activity on various microorganisms, such as Escherichia coli 8000 µg/mL, Staphylococcus aureus 2000 µg/mL, Pseudomonas aeruginosa 12,000 µg/mL, Penicillium italicum Wehmer 12,000 µg/mL, and Penicillium digitatum Sacc. 24,000 µg/mL [78].

Several studies highlight the antimicrobial capacity of citral. Dai et al. evaluated its activity against Staphylococcus aureus with an MIC of 2500 µg/mL [46]. Adukwu et al. determined MIC values against Acinetobacter baumannii of 1400 µg/mL and Staphylococcus aureus of 280 µg/mL [79]. In a study conducted with Candida albicans yeast, they found an MIC of 64 µg/mL [76]. Extensive research carried out on various microorganisms shows the following MIC results: Aspergillus niger 180 µg/mL; Trichoderma viride 265 µg/mL; Yersinia enterocolitica 200 µg/mL; Cronobacter sakazakii 540 µg/mL; Staphylococcus aureus 695 µg/mL; Bacillus cereus 400 µg/mL; and Enterobacter cloacae 1000 µg/mL [80].

The Cymbopogon citratus essential oil with high citral content demonstrated high antimicrobial effectiveness with the following MIC results: Escherichia coli 128 µg/mL; Klebsiella pneumoniae 124 µg/mL; Staphylococcus aureus 64 µg/mL; and Enterococcus faecalis 64 µg/mL [81]. An essential oil of Aloysia citrodora with a citral content of 34% presented the following MIC values: Enterobacter cloacae 1600 µg/mL; Escherichia coli 1600 µg/mL; Pseudomonas aeruginosa 25,000 µg/mL; Bacillus cereus 800 µg/mL; Listeria monocytogenes 3100 µg/mL; and Staphylococcus aureus 3100 µg/mL [82].

For the molecule E-2-dodecenal, there is little information available on its antimicrobial activity. The only studies found are on the essential oil of Eryngium foetidum, a plant native to the American tropics, which contains a high concentration of the molecule. A study conducted on its essential oil shows MIC values in Staphylococcus aureus of 1000–2000 µg/mL, with the oil containing 44% E-2-dodecenal [83]. Another trial has shown activity against Listeria monocytogenes, Helicobacter pylori, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae [83].

Structural damage assessment tests performed by microscopy show very severe damage to the yeast Candida tropicalis, with a decrease and destruction of cells, a significant reduction in their size, and an exit of the cytoplasm. In the Gram-positive bacteria Streptococcus mutans, the assay shows a decrease in bacterial concentration and destruction of the membrane and cytoplasm, which is particularly noticeable upon contact with E-2-dodecenal. Finally, in the Gram-negative bacteria Klebsiella oxytoca, changes in the cytoplasm and the onset of damage to the membrane are observed, which are more evident upon contact with E-2-dodecenal.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Microorganisms

The following chemical standards were used: 98.5% thymol Merck, code T0501; terpinen-4-ol, primary reference standard Merck, code 03900590; citral, analytical standard Supelco, code 43318; geranial and neral racemic mixture; and 95% E-2-dodecenal Sigma Aldrich, code 30658. In Figure 4, we can see the structures of the four metabolites.

Figure 4.

Molecules evaluated in different antimicrobial tests. (E) trans isomer, (Z) cis isomer, and O oxygenated group.

The microorganisms were used were Listeria grayi ATCC 25401, Streptococcus mutans ATCC 25175, Staphylococcus saprophyticus ATCC 15305, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Proteus vulgaris ATCC 6380, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Klebsiella oxytoca ATCC 8724, Candida tropicalis ATCC 13803, and Candida albicans ATCC 10231.

4.2. Antimicrobial Activity by Microdilution Plate Assay

Antimicrobial activity was performed following the protocol described by Noriega et al., 2023, for essential oils [84], with modifications in the concentrations of secondary metabolites, since this study does not work with mixtures of molecules as in an essential oil.

The process began with the preparation of the microorganism inoculum at concentrations of 108 CFU/mL for bacteria (7.5 × 107 CFU/mL in the wells after deposition) and 106 CFU/mL for yeasts (5.05 × 107 CFU/mL in the wells after deposition). The medium used for activation was Mueller–Hinton agar, the temperature for activating bacteria was 37 °C, and for yeast it was 25 °C, without modification of pH.

The inoculum was placed in the microplate wells in a volume of 150 µL, along with 20 µL of a metabolite solution in descending concentrations and 30 µL of 1% w/w 2,3,5-Triphenyl-tetrazolium chloride reagent (TTC). Secondary metabolites and the positive control were dissolved in DMSO at the following concentrations: 10%, 5%, 2.50%, 1.25%, 0.63%, 0.31%, 0.16%, 0.08, and 0.04%. The incubation time was 24 h, after which the absorbances were read in an Epoch Biotek microplate reader at a wavelength of 405 nm. Chloramphenicol was used as a positive control for bacterial activity and clotrimazole for yeast activity. The negative control was executed bacteria and TTC dye without the secondary metabolite.

The choice of microorganisms was primarily based on the availability of bacteria and yeasts in the laboratory, verification of adequate growth of the microorganisms, and having a homogeneous representation of Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, and yeasts.

4.3. Observation of Damage in the Bacteria Using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Several studies have been conducted to observe damage to bacterial structures using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), some of them on metabolites derived from essential oils such as terpinen-4-ol and citral [46,55].

The test sample was prepared using Gram-positive Streptococcus mutans bacteria and Gram-negative Klebsiella oxytoca bacteria at a concentration of 108 CFU/mL. Bacteria without the addition of any molecules were used as a negative control, while the tests were performed with the addition of chemical molecules at a concentration of 150 μg/mL; 5 μL of the bacterial culture from each treatment was added to a copper grid (formvar/carbon, 300 mesh) and then stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid (PTA, pH = 7) for one second. The samples were observed in a field emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FEG-SEM, TESCAN MIRA 3, Brno, Czech Republic) using a transmission detector.

4.4. Observation of Damage in Yeast Using Optical Microscopy

Yeasts can be observed using Optical Microscopy due to their large size [71], without the need for Electron Microscopy, simply by using a staining reagent to create a contrast that allows for proper observation.

The control inoculum of Candida tropicalis was prepared at a concentration of 106 CFU/mL, then each of the molecules under study was added separately until a concentration of 150 µg/mL was reached, methylene blue was added to each as a staining reagent for 5 min, and the samples were observed under a fluorescence optical microscope (NIKON ECCLIPSE NI-U, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) using Mshot Image Analysis System software version V 1.6.6.

4.5. Statistic

For the evaluation of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values, relative standard deviations and statistical significance. All computations were made using the statistical software STATISTICA 6.0.

5. Conclusions

The antimicrobial results in the four secondary metabolites show significant activity, for most tests between 500 µg/mL (0.05%) and 50 µg/mL (0.005%), concentrations that could be used in pharmaceutical and cosmetic products, as well as food preservatives.

The antimicrobial activity of molecules such as thymol and terpinen-4-ol had already been verified, while fewer studies have been conducted on citral and E-2-dodecenal.

Although the results are not as effective as those of the control antibiotics, they are still produced at low concentrations, suggesting that they could be incorporated into systemic formulations such as capsules or syrups and, above all, into topical antimicrobial and antifungal formulations. Another interesting application could be to prevent the growth of bacteria and yeasts in processed foods and cosmetic products, through their use as preservatives, to extend the shelf life of products without causing harm to human health, replacing synthetic antimicrobials such as parabens.

The structural damage caused by the four molecules confirms the good activity observed in the microplate dilution test. The results of the research serve to propose an antimicrobial use for these molecules derived from essential oils and to suggest the continuous evaluation of these metabolites with new strains of microorganisms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antibiotics14121202/s1. Document S1: MIC determination; Document S2: original photographs of the bacteria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.N. and K.J.; methodology, P.N. and A.D.; software, P.N.; validation, K.V., I.V. and K.J.; formal analysis, P.N. and E.R.; investigation, P.N.; resources, P.N. and A.D.; data curation, I.V.; writing—original draft preparation, P.N.; writing—review and editing, E.R.; visualization, A.D.; supervision, K.J.; project administration, P.N.; and funding acquisition, P.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

To biotechnology engineering students María José Guerrero, Stefanny Quinteros, and Stefanny Rivadeneira.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

References

- Piret, J.; Boivin, G. Pandemics throughout history. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, G.E.; Mclntyre, K.M.; Clough, H.E.; Rushton, J. Societal impacts of pandemics: Comparing COVID-19 with history to focus our response. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, A.; de Souza, F.F.; Pagani, R.N.; Kovaleski, J.L. Big data analytics as a tool for fighting pandemics: A systematic review of literature. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 9163–9180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Garg, S.; Joshi, H.; Ayaz, S.; Sharma, S.; Bhandari, M. Epidemics and pandemics in human history. Int. J. Pharma Res. Health Sci. 2020, 8, 3139–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vögele, J.; Rittershaus, L.; Schuler, K. Epidemics and Pandemics the Historical Perspective. Hist. Soc. Res. 2021, 33, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Vallejo, G. Epidemics and pandemics, a historical approach. Acta Med. Colomb. 2021, 46, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.V. Epidemics and pandemics in human history: Origins, effects and response measures. VNUHCM J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 4, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quteimat, O.M.; Amer, A.M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer patients. Am. J. Clin. Oncolog. 2020, 43, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Lacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, C.A.; Morran, M.P.; Nestor-Kalinoski, A.L. The COVID-19 pandemic: A global health crisis. Physiolog. Genom. 2020, 52, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkar, P. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education system. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 3812–3814. [Google Scholar]

- Laffin, L.J.; Kaufman, H.W.; Chen, Z.; Niles, J.K.; Arellano, A.R.; Bare, L.A.; Hazen, S.L. Rise in blood pressure observed among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Circulation 2022, 145, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msemburi, W.; Karlinsky, A.; Knutson, V.; Aleshin-Guendel, S.; Chatterji, S.; Wakefield, J. The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 2023, 613, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Paulson, K.R.; Pease, S.A.; Watson, S.; Comfort, H.; Zheng, P.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Bisignano, C.; Barber, R.M.; Alam, T.; et al. Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020–2021. Lancet 2022, 399, 1513–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro da Silva, S.J.; Frutuoso do Nascimento, J.C.; Germano Mendes, R.P.; Guarines, K.M.; Targino Alves da Silva, C.; Gomes da Silva, P.; Ferraz de Magalhães, J.J.; Vigar, J.R.; Silva-Júnior, A.; Kohl, A.; et al. Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learned. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 8, 1758–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligon, B.L. Penicillin: Its discovery and early development. Semin. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 2004, 15, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, A.G. Responsibilities and opportunities of the private practitioner in preventive medicine. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1929, 20, 3–11. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1710366/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Hutchings, M.I.; Truman, A.W.; Wilkinson, B. Antibiotics: Past, present and future. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 51, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyler, R.F.; Shvets, K. Clinical pharmacology of antibiotics. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, S.R.; Shrivastava, P.S.; Ramasamy, J. World health organization releases global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. J. Med. Soc. 2018, 32, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neu, H.C. The crisis in antibiotic resistance. Science 1992, 257, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T.H.; Al-Harmoosh, R.A. Mechanisms of antibiotics resistance in bacteria. Sys. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.; Khan, A. Antibiotics resistance of bacterial biofilms. Middle East J. Bus. 2015, 55, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terreni, M.; Taccani, M.; Pregnolato, M. New antibiotics for multidrug-resistant bacterial strains: Latest research developments and future perspectives. Molecules 2021, 26, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, T.M.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Khusro, A.; Zidan, B.R.; Mitra, S.; Emran, T.B.; Dhama, K.; Ripon, M.K.; Gajdács, M.; Sahibzada, M.U.; et al. Antibiotic resistance in microbes: History, mechanisms, therapeutic strategies and future prospects. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 1750–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Biondo, C. Bacterial antibiotic resistance: The most critical pathogens. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, T.V. Natural products and their derivatives with antibacterial, antioxidant and anticancer activities. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manso, T.; Lores, M.; de Miguel, T. Antimicrobial activity of polyphenols and natural polyphenolic extracts on clinical isolates. Antibiotics 2021, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlowska, M.; Ścibisz, I.; Przybyl, J.L.; Laudy, A.E.; Majewska, E.; Tarnowska, K.; Malajowicz, J.; Ziarno, M. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of extracts from selected plant material. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Lv, L.; Gao, B.; Li, M. Research progress on antibacterial activities and mechanisms of natural alkaloids: A review. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushnie, T.T.; Cushnie, B.; Lamb, A.J. Alkaloids: An overview of their antibacterial, antibiotic-enhancing and antivirulence activities. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2014, 44, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A.C.; Meireles, L.M.; Lemos, M.F.; Guimarães, M.C.; Endringer, D.C.; Fronza, M.; Scherer, R. Antibacterial activity of terpenes and terpenoids present in essential oils. Molecules 2019, 24, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paduch, R.; Kandefer-Szerszeń, M.; Trytek, M.; Fiedurek, J. Terpenes: Substances useful in human healthcare. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2007, 55, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Musayeib, N.M.; Musarat, A.; Maqsood, F. Eco-Friendly Biobased Products Used in Microbial Diseases, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 247–270. ISBN 978-100-324-370-0. [Google Scholar]

- Malmir, M.; Serrano, R.; Silva, O. Anthraquinones as potential antimicrobial agents-A review. In Antimicrobial Research: Novel Bioknowledge and Educational Programs, 1st ed.; Méndez-Vilas, A., Ed.; Formatex Research Center: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017; pp. 55–61. ISBN 978-849-475-120-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez Ghoran, S.; Taktaz, F.; Ayatollahi, S.A.; Kijjoa, A. Anthraquinones and their analogues from marine-derived fungi: Chemistry and biological activities. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, F.; Pinna, C.; Dallavalle, S.; Tamborini, L.; Pinto, A. An overview of coumarin as a versatile and readily accessible scaffold with broad-ranging biological activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, P.N. Extracción, química, actividad biológica, control de calidad y potencial económico de los aceites esenciales. LA GRANJA. Rev. Cienc. Vida 2009, 10, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Escobar, A.; Perez, M.; Romanelli, G.; Blustein, G. Thymol bioactivity: A review focusing on practical applications. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 9243–9269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolin, G.A.; Vital, V.G.; de Vasconcellos, S.P.; Lago, J.H.; Péres, L.O. Thymol as Starting Material for the Development of a Biobased Material with Enhanced Antimicrobial Activity: Synthesis, Characterization, and Potential Application. Molecules 2024, 29, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadia, Z.; Rachid, M. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Thymus vulgaris L. Med. Aromat. Plant Res. J. 2013, 1, 5–11. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284967745 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.L.; Wang, W.; Wang, G. Recent updates on bioactive properties of α-terpineol. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2023, 35, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puvača, N.; Milenković, J.; Galonja Coghill, T.; Bursić, V.; Petrović, A.; Tanasković, S.; Pelić, M.; Ljubojević Pelić, D.; Miljković, T. Antimicrobial activity of selected essential oils against selected pathogenic bacteria: In vitro study. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, V.V.; Almeida, J.M.; Barbosa, L.N.; Silva, N.C. Citral, carvacrol, eugenol and thymol: Antimicrobial activity and its application in food. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2022, 34, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valková, V.; Ďúranová, H.; Galovičová, L.; Borotová, P.; Vukovic, N.L.; Vukic, M.; Kačániová, M. Cymbopogon citratus essential oil: Its application as an antimicrobial agent in food preservation. Agronomy 2022, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Bai, M.; Li, C.; San Cheang, W.; Cui, H.; Lin, L. Antibacterial properties of citral against Staphylococcus aureus: From membrane damage to metabolic inhibition. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recio-Cázares, S.L.; López-Malo, A.; Ramírez-Corona, N.; Palou, E. Relationship Between the Chemical Composition and Transport Properties with the Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oil from Leaves of Mexican Lippia (Aloysia citriodora) Extracted by Hydro-Distillation. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2023, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paw, M.; Gogoi, R.; Sarma, N.; Saikia, S.; Chanda, S.K.; Lekhak, H.; Lal, M. Anti-microbial, Anti-oxidant, Anti-diabetic study of leaf Essential Oil of Eryngium foetidum L. Along with the Chemical Profiling Collected from North East India. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2022, 25, 1229–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Ruíz, M.; Navarro-Mengual, J.D.; Jaramillo-Colorado, B.E. In vitro antibacterial activity of essential oils from Eryngium foetidum L. and Clinopodium brownei (Sw.) Kuntze. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Hortic. 2024, 18, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donega, M.A.; Mello, S.C.; Moraes, R.M.; Jain, S.K.; Tekwani, B.L.; Cantrell, C.L. Pharmacological activities of Cilantroʼs aliphatic aldehydes against Leishmania donovani. Planta Med. 2014, 80, 1706–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Przychodna, M.; Sopata, S.; Bodalska, A.; Fecka, I. Thymol and thyme essential oil new insights into selected therapeutic applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, R.J.; Skandamis, P.N.; Coote, P.J.; Nychas, G.J. A study of the minimum inhibitory concentration and mode of action of oregano essential oil, thymol and carvacrol. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 91, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, A.; Orhan, I.E.; Daglia, M.; Barbieri, R.; Di Lorenzo, A.; Nabavi, S.F.; Gortzi, O.; Izadi, M.; Nabavi, S.M. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of thymol: A brief review of the literature. Food Chem. 2016, 210, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachur, K.; Suntres, Z. The antibacterial properties of phenolic isomers, carvacrol and thymol. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 3042–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, S.; Du, S.; Chen, S.; Sun, H. Antifungal activity of thymol and carvacrol against postharvest pathogens Botrytis cinerea. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šegvić Klarić, M.; Kosalec, I.; Mastelić, J.; Pieckova, E.; Pepeljnak, S. Antifungal activity of thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) essential oil and thymol against moulds from damp dwellings. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 44, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linge, K.L.; Cooper, L.; Downey, A. Comparison of approaches for authentication of commercial terpinen-4-ol-type tea tree oils using chiral GC/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 8389–8400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, M.M.; Taktak, N.E.; Badawy, M.E. Comparison of the antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) oil and its main component terpinen-4-ol with their nanoemulsions. Egypt. J. Chem. 2023, 66, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, F.; Panghyová, L.; Vargová, V.; Baxa, S.; Polovka, M.; Kopuncová, M.; Tobolková, B.; Hrouzková, S.; Sádecká, J. Gas-chromatographic analyses of volatile organic compounds in essential oils extracted from Slovak juniper berries and needles (Juniperus communis L.). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 133, 106419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annemer, S.; Farah, A.; Stambouli, H.; Assouguem, A.; Almutairi, M.H.; Sayed, A.A.; Peluso, I.; Bouayoun, T.; Talaat Nouh, N.A.; Ouali Lalami, A.E.; et al. Chemometric investigation and antimicrobial activity of Salvia rosmarinus Spenn essential oils. Molecules 2022, 27, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.G.; Unnikrishnan, V.K.; Muralidharan, N.; Venkatathri, B.N.; Lowrence, R.C.; Ybrd, R.; Nagarajan, S. Human vaginal Lactobacillus Jensenii-derived (-)-Terpinen-4-ol restores antibiotic sensitivity by inhibiting efflux pumps in drug resistant E. coli and K. pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, L.J.; Zhao, Y.H.; Ma, W.X.; Feng, S.L.; Yang, C.Y.; Tu, Y.X.; Zhang, J. Study on the inhibitory effect of essential oil from Artemisia scoparia and its active ingredient terpine-4-ol on Aspergillus flavus. Chin. J. Biol. Control. 2021, 37, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, M.; Maroselli, T.; Casanova, J.; Bighelli, A. A fast and reliable method to quantify neral and geranial (citral) in essential oils using 1H NMR spectroscopy. Flavour Fragr. J. 2023, 38, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elechosa, M.A.; Lira, P.D.; Juárez, M.A.; Viturro, C.I.; Heit, C.I.; Molina, A.C.; Martínez, A.J.; López, S.; Molina, A.M.; van Baren, C.M.; et al. Essential oil chemotypes of Aloysia citrodora (Verbenaceae) in Northwestern Argentina. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2017, 74, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, T.T.; Ngan, L.T.; Le, B.V.; Hieu, T.T. Effects of plant essential oils and their constituents on Helicobacter pylori: A Review. Plant Sci. Today 2023, 10, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.S.; Essien, E.E.; Ntuk, S.J.; Choudhary, M.I. Eryngium foetidum L. essential oils: Chemical composition and antioxidant capacity. Medicines 2017, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, I.; Fujita, K.; Nihei, K.; Kubo, A. Anti-Salmonella activity of (2 E)-alkenals. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 96, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, I.; Fujita, K.I.; Kubo, A.; Nihei, K.I.; Lunde, C.S. Modos de acción antifúngica de los (2 E)-alkenales contra Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Rev. Química Agrícola Aliment. 2003, 51, 3951–3957. [Google Scholar]

- Falcone, P.; Speranza, B.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M. A study on the antimicrobial activity of thymol intended as a natural preservative. J. Food Prot. 2005, 68, 1664–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarda, A.; Rubilar, J.F.; Miltz, J.; Galotto, M.J. The antimicrobial activity of microencapsulated thymol and carvacrol. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 146, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, J.X.; Khazandi, M.; Chan, W.Y.; Trott, D.J.; Deo, P. Antimicrobial activity of thyme oil, oregano oil, thymol and carvacrol against sensitive and resistant microbial isolates from dogs with otitis externa. Vet. Dermatol. 2019, 30, 524-e159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianu, C.; Rusu, L.C.; Muntean, I.; Cocan, I.; Lukinich-Gruia, A.T.; Goleț, I.; Horhat, D.; Mioc, M.; Mioc, A.; Soica, C.; et al. In vitro and in Silico evaluation of the antimicrobial and antioxidant potential of Thymus pulegioides essential oil. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-López, N.; Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Vazquez-Olivo, G.; Heredia, J.B. Essential oils of oregano: Biological activity beyond their antimicrobial properties. Molecules 2017, 22, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondello, F.; Fontana, S.; Scaturro, M.; Girolamo, A.; Colone, M.; Stringaro, A.; di Vito, M.; Ricci, M.L. Terpinen-4-ol, the main bioactive component of tea tree oil, as an innovative antimicrobial agent against Legionella pneumophila. Pathogens 2022, 11, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noumi, E.; Merghni, A.; Alreshidi, M.M.; Haddad, O.; Akmadar, G.; De Martino, L.; Mastouri, M.; Ceylan, O.; Snoussi, M.; Al-Sieni, A.; et al. Chromobacterium violaceum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1: Models for evaluating anti-quorum sensing activity of Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil and its main component terpinen-4-ol. Molecules 2018, 23, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brilhante, R.S.; Caetano, É.P.; Lima, R.A.; Marques, F.J.; Castelo-Branco, D.D.; Silva de Melo, C.V.; de Melo Guedes, G.M.; de Oliveira, J.S.; de Camargo, Z.P.; Bezerra Moreira, J.L.; et al. Terpinen-4-ol, tyrosol, and β-lapachone as potential antifungals against dimorphic fungi. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2016, 47, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, K.A.; Carson, C.F.; Riley, T.V. Effects of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) essential oil and the major monoterpene component terpinen-4-ol on the development of single-and multistep antibiotic resistance and antimicrobial susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borotová, P.; Galovičová, L.; Vukovic, N.L.; Vukic, M.; Tvrdá, E.; Kačániová, M. Chemical and biological characterization of Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil. Plants 2022, 11, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adukwu, E.C.; Bowles, M.; Edwards-Jones, V.; Bone, H. Antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity and chemical analysis of lemongrass essential oil (Cymbopogon flexuosus) and pure citral. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 9619–9627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mei, J.; Xie, J. Citral: Bioactivity, Metabolism, Delivery Systems, and Food Preservation Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.R.; Singh, V.; Singh, R.K.; Ebibeni, N. Antimicrobial activity of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) oil against microbes of environmental, clinical and food origin. Int. Res. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011, 1, 228–236. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260173692 (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Sprea, R.M.; Fernandes, L.H.; Pires, T.C.; Calhelha, R.C.; Rodrigues, P.J.; Amaral, J.S. Volatile compounds and biological activity of the essential oil of Aloysia citrodora Paláu: Comparison of hydrodistillation and microwave-assisted hydrodistillation. Molecules 2023, 28, 4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silalahi, M. Essential oils and uses of Eryngium foetidum L. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 15, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, P.; Calderón, L.; Ojeda, A.; Paredes, E. Chemical composition, antimicrobial and antioxidant bioautography activity of essential oil from leaves of Amazon plant Clinopodium brownei (Sw.). Molecules 2023, 28, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).