Abstract

Background: Thermophilic Campylobacter species are among the main culprits behind bacterial gastroenteritis globally and have grown progressively resistant to clinically important antimicrobials. Many studies have been carried out to explore innovative and alternative strategies to control antibiotic-resistant campylobacters in animal reservoirs and human hosts; however, limited studies have been performed to develop efficient control schemes against Campylobacter biofilms. Methods: This study investigated the antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of some herbal extracts against multidrug-resistant (MDR) Campylobacter species recovered from different sources using phenotypic and molecular techniques. Results: The overall Campylobacter species prevalence was 21.5%, representing 15.25% and 6.25% for C. jejuni and C. coli, respectively. Regarding C. jejuni, the highest resistance rate was observed for amoxicillin–clavulanic acid and colistin (85.25% each), followed by cefotaxime (83.61%) and tetracycline (81.97%), whereas C. coli isolates showed absolute resistance to cefotaxime followed by erythromycin (92%) and colistin (88%). Remarkably, all Campylobacter isolates were MDR with elevated multiple antimicrobial resistance (MAR) indices (0.54–1). The antimicrobial potentials of green tea (Camellia sinensis), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) and ginger (Zingiber officinale) extracts against MDR Campylobacter isolates were assessed by the disk diffusion assay and broth microdilution technique. Green tea extract showed a marked inhibitory effect against tested isolates, exhibiting growth inhibition zone diameters of 8 to 38 mm and a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) range of 1.56–3.12 mg/mL, unlike the rosemary and ginger extracts. Our findings reveal a respectable antibiofilm activity (>50% biofilm formation inhibition) of green tea against the preformed biofilms of Campylobacter isolates. Furthermore, real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) results showed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the expression levels of biofilm biosynthesis gene and its regulator (FlaA and LuxS, respectively) in Campylobacter isolates treated with the green tea extract in comparison with untreated ones. Conclusion: This is the first in vitro approach that has documented the inhibitory activity of green tea extract against MDR-biofilm-producing Campylobacter species isolated from different sources. Further in vivo studies in animals’ models should be performed to provide evidence of concept for the implementation of this alternative candidate for the mitigation of MDR Campylobacter infections in the future.

1. Introduction

Campylobacteriosis is a zoonotic illness caused by Campylobacter species; these have been reported as the main foodborne pathogens and the most common bacterial causes of gastroenteritis in humans worldwide [1]. Campylobacter is a gram-negative bacilli, spiral or slightly curved, motile, non-spore forming and microaerophilic bacteria [2]. Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) and Campylobacter coli (C. coli) are the two major species responsible for severe cases of human gastroenteritis [3].

Campylobacter species may exist in aggregated communities enclosed in a self-produced matrix known as a biofilm [4]. The molecular basis of biofilm development in Campylobacter is still not fully understood, although there is evidence that quorum sensing represented by S-ribosylhomocysteine lyase (luxS), flagella, and surface proteins, are necessary to optimize biofilm formation. Several studies have demonstrated that the luxS gene is implied in various physiological pathways in C. jejuni, including motility, flagellar expression, oxidative stress, autoagglutination, and animal colonization [5,6,7,8]. The biofilm formation results in increased resistance to negative environmental influences, including resistance to antimicrobial agents, resulting in chronic infections [9]. Treatment of campylobacteriosis may be complicated by the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Campylobacter species, which may be attributed to the excessive and uncontrolled use of antimicrobials in the poultry industry, livestock farming and veterinary medicine [10,11]. The ongoing spread and emergence of drug-resistant Campylobacter species exacerbate therapeutic challenges, raising the frequency of diseases and fatalities.

In the literature, green tea (Camellia sinensis), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) and ginger (Zingiber officinale) extracts have been shown to exhibit resonant antimicrobial activities against pathogenic gram-negative bacteria and thus may support the development of antimicrobial supplements [12,13,14]. Green tea is rich in polyphenols termed catechins, especially epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) which is a major antimicrobial compound against various pathogenic organisms [15]. These catechins showed high activity against gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria using several molecular mechanisms, including the inhibition of the cell membrane, cell wall, nucleic acid and protein syntheses, and the inhibition of various metabolic pathways, such as extracellular matrix virulence factors, toxins, iron chelation, and oxidative stress. Rosemary extract is a household herb that comprehends a number of phytochemicals, comprising rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, camphor, betulinic acid, ursolic acid, and the antioxidant carnosic acid [16]. Rosemary leaf extracts have a variety of in vitro bioactivities including antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-tumor, antiulcerogenic, antidiuretic, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic activities [17]. Additionally, ginger extract is an excellent source of a variety of bioactive composites, including bioactive phenols (shogaols, gingerols, and zingerones) [18]. Thus, more studies pertaining to the use of plant extracts as therapeutic agents should be emphasized, especially those related to the control of antibiotic-resistant microbes. The objective of this study is to investigate the antimicrobial, antibiofilm and anti-quorum sensing activities of plant-derived natural products as promising contenders of sustainable alternatives for combating drug resistance and treatment of biofilm-associated infections.

2. Results

2.1. Prevalence of Campylobacter Species in Animal, Environmental and Human Sources

As illustrated in Table 1, out of 290 chicken samples, 66 (22.76%) Campylobacter isolates were recovered, represented as 15.52% C. jejuni and 7.24% C. coli. However, examination of environmental samples revealed only C. jejuni with a percentage of 8.33%. Regarding human samples, Campylobacter species was detected in 30% of cases, with 20% being C. jejuni and 10% C. coli. Statistical analysis showed significant disparities in the prevalence of Campylobacter isolates among chickens and their products, environmental sources, and human stool (p = 0.0137). Noteworthy variations were also found within each source category, especially between chickens and their products, with the highest rates appearing in liver samples (60.00%). Conversely, no significant distinctions were observed in the occurrence of these microbial isolates across different environmental sources.

Table 1.

Occurrence of Campylobacter species in animal, environmental and human sources.

Conventional identification of Campylobacter species was simply determined. On mCCDA agar, C. jejuni appeared as grey and moist spreading colonies, whereas C. coli was creamy-grey with slightly raised discrete colonies. Biochemical characteristics of campylobacters yielded positive results for catalase, oxidase, and nitrate reduction tests. All isolates were sensitive to nalidixic acid and resistant to cephalothin. However, at the species level, C. jejuni isolates were hippurate and indoxyl acetate positive, while C. coli isolates were indoxyl acetate positive and hippurate negative. Molecular confirmation of the recovered isolates was performed based on the genus-specific (23S rRNA) and species-specific (mapA, and ceuE) primers, giving characteristic bands at 650, 589 and 462 bps for Camplobacter species, C. jejuni and C. coli, respectively.

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Campylobacter Species

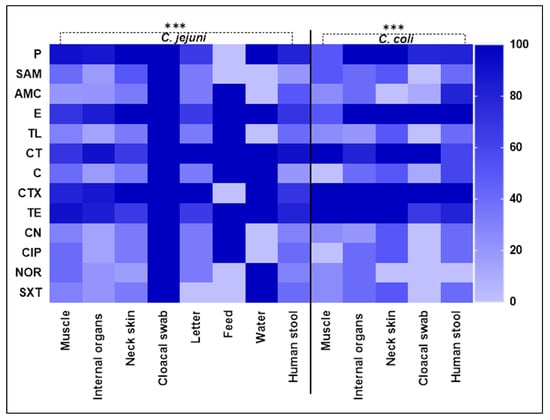

The antibiogram of Campylobacter isolates (n = 86) comprising 61 C. jejuni and 25 C. coli against 13 tested antimicrobial agents is presented in Table 2 and in Figure 1. Regarding C. jejuni isolates, the greatest rate of resistance was noted for penicillin and colistin (85.25% each), followed by cefotaxime (83.61%) and tetracycline (81.97%), whereas gentamycin showed the least resistance rate (22.95%), followed by ampicillin–sulbactam and tylosin (26.23% each), chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, and sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim (27.87% each) and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (29.51%). On the other hand, C. coli isolates showed absolute resistance to cefotaxime, followed by erythromycin (92%) and colistin (88%). Interestingly, all Campylobacter isolates were found to be MDR, exhibiting resistance to 8 to 13 antimicrobial agents. The antimicrobial resistance of C. jejuni isolates exhibited significant differences across all studied antimicrobials, with the exception of erythromycin, colistin, and tetracycline (p = 0.5416, 0.6129, and 0.4534, respectively; Table 2). In the case of C. coli, significant differences were observed against all examined antimicrobials, except for the three mentioned earlier (p = 0.5153, 0.7641, 1.00, and 0.5686, respectively; Table 2).

Table 2.

Antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter species isolated from animal, environmental and human sources.

Figure 1.

The heatmap illustrates the antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter species recovered from different sources. Dark colors refer to the antimicrobials displaying high resistance levels and light colors refers to the antimicrobials displaying low resistance. Color bar on the right side indicates color intensity. AMA, antimicrobial agent; P, penicillin; SAM, ampicillin–sulbactam; AMC, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid; E, erythromycin; TL, tylosin; CT, colistin; C, chloramphenicol; CTX, cefotaxime; TE, tetracycline; CN, gentamycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; NOR, norfloxacin; SXT, sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim. *** indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

2.3. Biofilm Formation by Multidrug-Resistant Campylobacter Isolates

The antimicrobial resistance patterns and the degrees of biofilm formation in 20 MDR Campylobacter isolates (16 C. jejuni and 4 C. coli) are presented in Table 3. The MDR Campylobacter isolates exhibiting high MAR indices (0.54–1) were examined for biofilm production using the microtiter plate method. The results reveal that tested isolates differ in their ability to form biofilms. All examined Campylobacter isolates of human origin (n = 3) were strong biofilm producers, whereas 8 (57.1%), 5 (35%) and 1 (7.11%) out of 14 Campylobacter isolates of chicken origin were strong, moderate, and weak biofilm producers, respectively. Moreover, the three isolates of environmental source were strong biofilm producers.

Table 3.

Characterization and biofilm formation by MDR Campylobacter isolates.

2.4. Antimicrobial Activities of Green Tea, Rosemary and Ginger Extracts Against MDR Campylobacter Species

As shown in Table 4, all MDR Campylobacter isolates were sensitive to the green tea extract, exhibiting zones of growth inhibition ranging from 8 to 38 mm and MIC values of 1.56–3.12 mg/mL. Meanwhile, MDR Campylobacter isolates were inhibited by rosemary extract at higher concentrations (MIC range of 25–50 mg/mL). On the other hand, MDR Campylobacter isolates showed modest sensitivity to the ginger extract, exhibiting growth inhibition zones ranging from 6 to 20 mm and an MIC range of 12.5–50 mg/mL. The negative control phosphate buffer saline (PBS) revealed no inhibition zones for all examined isolates. The impact of various concentrations of plant extracts on C. jejuni and C. coli exhibited noteworthy variances (p < 0.05). Regression analysis for the disc diffusion unveiled that the zone diameters decreased by 0.576 mm, 0.334 mm, and 0.370 mm with every unit decrease in concentrations of green tea, rosemary, and ginger extracts, respectively (p < 0.05). Moreover, the MIC values significantly differed, notably being lower with green tea compared with rosemary and ginger extracts.

Table 4.

Antibacterial activities of various plant extracts against Campylobacter isolates.

2.5. Characterization of Green Tea Extract Using HPLC

Analysis of green tea extract revealed eight characteristic components; the gallic acid was the most abundant constituent (424.69 µg/mL) followed by rutin (176.50 µg/mL) and catechin (150.77 µg/mL). Various constituents were not detected in the study extract when compared with the standard green tea, as presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

HPLC analysis results showing the constituents of green tea extract.

2.6. Analysis of Green Tea Extract Using Liquid Chromatography–Electrospray Ionization–Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS)

2.6.1. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents of Green Tea

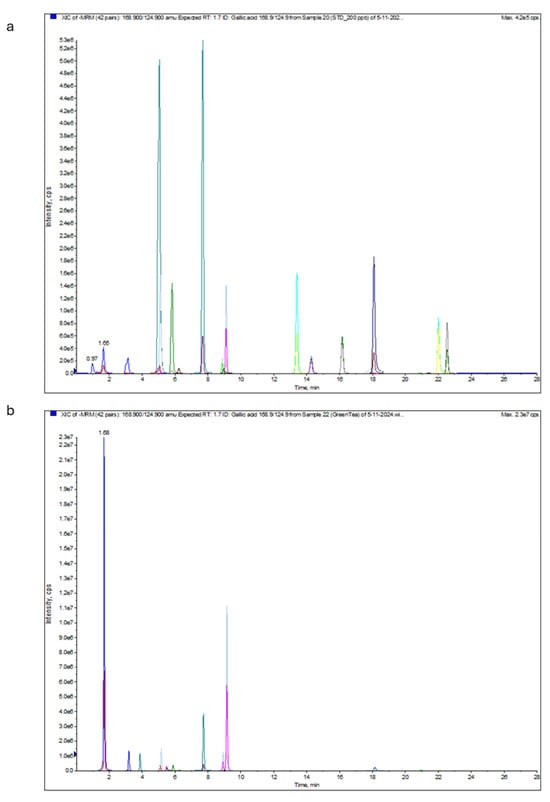

The total phenolic and flavonoid contents of green tea extract are shown in Table 6 and Figure 2. LC-ESI-MS/MS could identify 20 phenolic and flavonoid constituents in the analyzed green tea sample. Gallic acid was the most abundant at the negative mode with a concentration of 86.51 µg/mL, followed by naringenin (47.01 µg/mL). Peak identification was based on analysis of the obtained data and direct comparison with standards.

Table 6.

Total phenolic and flavonoid compounds of the green tea extract analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS.

Figure 2.

LC-ESI-MS/MS multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) chromatogram of the standard sample (a) and green tea extract sample (b). Different colours indicate extract constituents, and each analyte has two fragments generated at the same extension time. The scientific notation (i.e., 1.0e+6 is equal to 1 × 106) could be converted into decimal notation using the following website: https://converthere.com/numbers/2.3e+7-written-out (accessed on 2 December 2024).

2.6.2. Catechins of Green Tea Extract

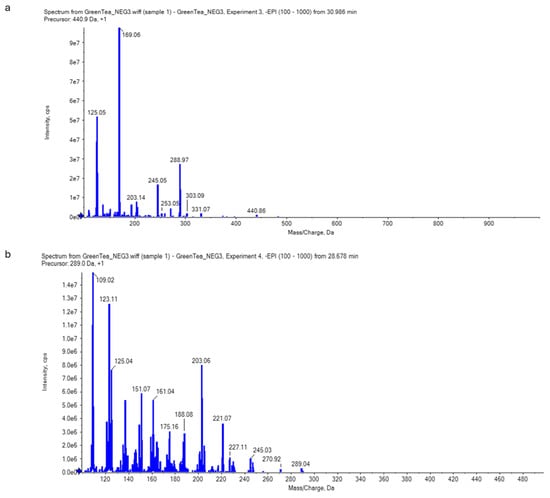

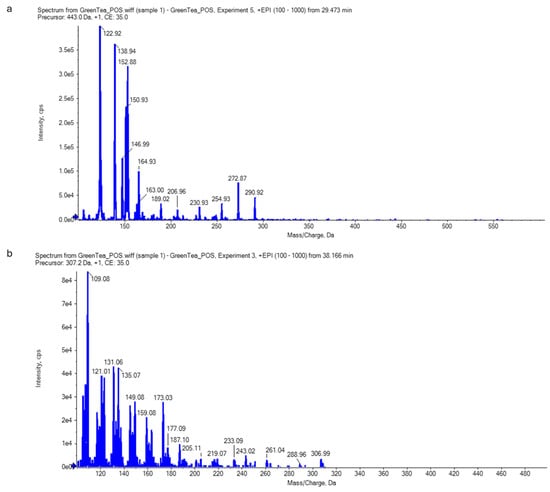

The LC-ESI-MS/MS could identify the main secondary metabolites of green tea, especially of catechins, using the retention time and mass spectral information. The results were found to reveal epigallocatechin gallate, EGCG [M-H2O-H]- at the negative mode (Figure 3) and both epicatechin–gallate (ECG) and epigallocatechine (EGC) at the positive mode (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Catechins (a) and epigallocatechin gallate [M-H2O-H]- (EGCG) (b) identified in the green tea extract by LC-ESI-MS/MS in negative mode. The scientific notation (i.e., 1.0e6 is equal to 1 × 106) could be converted into decimal notation using the following website: https://converthere.com/numbers/2.3e+7-written-out (accessed on 2 December 2024).

Figure 4.

Epicatechin–gallate (ECG) (a) and epigallocatechine (EGC) (b) identified in the green tea extract by LC-ESI-MS/MS in positive mode. The scientific notation (i.e., 1e4 is equal to 1 × 104) could be converted into decimal notation using the following website: https://converthere.com/numbers/2.3e+7-written-out (accessed on 2 December 2024).

2.7. Antibiofilm Activity of Green Tea Extract Against Campylobacter Species

The antibiofilm activity of green tea extract against pre-existing biofilms produced by C. jejuni and C. coli isolates appeared to be concentration dependent (1.56–3.12 mg/L). Our results show good antibiofilm activity (>50% inhibition of biofilm formation) of green tea extract against the preformed biofilms of Campylobacter isolates (Table 7). The results were compared with those of untreated C. jejuni and C. coli biofilm producers (positive control) as well as non-biofilm producers (negative control). Statistical analysis revealed that the antibiofilm activity values of green tea extract against MDR biofilm-producing Campylobacter isolates were markedly greater pre-treatment compared with post-treatment, with a significant difference noted (p = 0.0001).

Table 7.

Antibiofilm activity of green tea extract against MDR-biofilm-producing Campylobacter isolates.

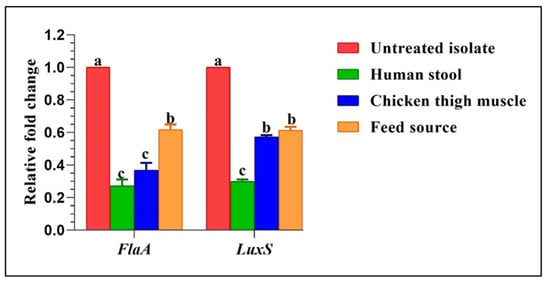

2.8. Transcriptional Changes of Biofilm Genes Post Treatment by Green Tea Extract

To further confirm the subinhibitory concentration (SIC) effects of green tea extract on pre-existing biofilms of the strong biofilm-producing Campylobacter isolates, transcript levels of the expression of the biofilm-associated genes, FlaA and LuxS, were evaluated by RT-qPCR (Figure 5). In all examined isolates, the transcription levels of both genes were notably decreased in comparison to the untreated isolates (p < 0.05), which are assigned a value of 1.0, minimizing in human stool (changes of up to 0.2432 and 0.3078-fold for the abovementioned genes, respectively), which illustrated the strong antibiofilm activity of the green tea against MDR strong biofilm-producing Campylobacter isolates. No significant variances were found between Campylobacter isolates recovered from human stool and chicken thigh muscles concerning the FlaA gene expression, as well as between those obtained from the environmental source (feed) and chicken thigh muscles regarding the LuxS gene expression (p > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Fold changes in the expression levels of examined biofilm genes after treatment of Campylobacter isolates with sub-inhibitory concentrations of green tea extract. a–c Values of the same row with different superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05).

3. Discussion

Thermotolerant campylobacters, predominantly C. coli and C. jejuni, are considered the most important agents of bacterial gastroenteritis worldwide. Currently, an emerging problem among campylobacters is the elevating resistance to major antibiotics in use [19]. Hence, this study investigated the antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of some plant-derived extracts against MDR biofilm-producing Campylobacter isolates.

Herein, the prevalence of Campylobacter species in chicken samples was 22.76%, which was lower than a previous study in Egypt (58.11%) [19]. However, a slightly higher prevalence rate of Campylobacter species has been previously documented in the united states (25.4%) [20]. It is known that poultry can be contaminated from a variety of sources on farms and that the contaminants are dispersed through processing, scalding, defeathering, evisceration and giblet operations; further spread can occur during handling in markets and kitchens [21]. On the other hand, examination of environmental samples revealed only C. jejuni, with a percentage of 8.33%, which was lower than a previous record in Egypt (13.3%) [22]. Regarding human samples, Campylobacter species was detected in 30% of examined stool samples, which was lower than previous studies at 14.7% [22], 26% [23] and 83.33% [24], but higher than another report in Egypt (2.7%) [25]. Variations in the prevalence of Campylobacter species across different studies can be attributed to numerous factors, such as bacterial contamination, health conditions, geographical locations, climate influences, sources of the samples analyzed, and the traditional methods used for identification [26].

Lately, resistance of Campylobacter species to antimicrobial agents has become an important public health problem around the world, particularly resistance to fluoroquinolones, macrolides, tetracycline, aminoglycoside and beta lactams [27]. Furthermore, intrinsic resistance has been described in C. jejuni and C. coli against penicillin, most cephalosporins, trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole, vancomycin and rifampicin [28,29,30]. Interestingly, all Campylobacter isolates in this study were MDR, exhibiting resistance to 8 to 13 antimicrobial agents, which is similar to the results of a previous study in China [31]. Unsurprisingly, there is variation in antimicrobial resistance between and within different countries, which is closely related to the types of drugs prescribed as well as variation in guidelines for the use of antimicrobial drugs. These findings are alarming and correlate well with the uncontrolled use of drugs as growth promotors and prophylaxes in animal production [32,33,34]. Hence, this study highlighted the necessity of using antimicrobial agents sparingly in veterinary medicine to avoid the emergence of antimicrobial resistance in both humans and animals. Furthermore, it is highly recommended to look for novel, appropriate, and potent natural antimicrobial compounds, especially against Campylobacter infections.

Medicinal plants possess remarkable potential for generating a wide array of bioactive molecules with antibacterial properties, offering a vast and inexhaustible repertoire [35,36,37,38]. Moreover, they interact safely with the body’s vital systems, exhibiting minimal side effects [39]. In the current study, we evaluated the antimicrobial activities of green tea, rosemary and ginger extracts against MDR Campylobacter species. Our findings proved that green tea extract demonstrated strong antimicrobial activity against examined isolates, whereas rosemary and ginger extracts exhibited only moderate to weak antimicrobial effects.

The important components of green tea that show antimicrobial properties are the catechins. The four main catechins in green tea are epicatechin (EC), epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG), epigallocatechin (EGC), and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG). Of these catechins, EGCG and EGC are abundant and have been shown to demonstrate antimicrobial properties against various bacterial species [40]. Upon reviewing the literature, numerous natural compounds have been used to combat a variety of microbial genera and/or species [41,42,43]. However, there were no reports found to be available on the antimicrobial activity of green tea against Campylobacter species, at least in Egypt. However, previous studies have focused on the inhibitory activity of green tea on E. coli, S. Typhi and S. Typhimurium [44].

On the other hand, Friedman and coworkers [45] have demonstrated that ginger extract exhibits moderate antimicrobial effect against Campylobacter species, whereas Mutlu-Ingok et al. [46] have reported the low activity of the abovementioned extract against corresponding isolates. The active ingredients in the ginger extract, including phenyl propanoid-derived compounds, particularly gingerols, paradol, shogaols, and zingerone, are responsible for its antimicrobial activity against certain pathogens [47]. However, the inhibitory activity of rosemary oil against Campylobacter species may be attributed to the inclusion of rosmarinic acid, carnosic acid and their derivatives, such as carnosonal, rosmanol and isorosmanol. These substances interact with bacteria cell membranes to modify their genetic materials, electron transport, cellular component leakage, and fatty acid synthesis [48,49]. It has been documented that the effectiveness of carsonic acid against pathogenic bacteria exceeds that of other major extract components, including rosmarinic acid [50].

As the green tea extract exerted potent antimicrobial activity against the Campylobacter species under study, it was characterized using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS). As demonstrated in the HPLC analysis datasheet of green tea extract, gallic acid presented the most abundant constituent. Gallic acid is a natural component in many traditional Chinese medications, and has antibacterial, and antiseptic activities. Gallic acid exerted a bactericidal effect against MDR E. coli via its disruption of the integrity of the outer and inner membranes and by suppressing the expression of efflux pump genes. Thus, gallic acid holds promise as a possible bactericidal agent with which to combat the emergence and spread of MDR E. coli [51]. Similarly, LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis revealed that gallic acid was the most abundant ingredient at the negative mode, with a concentration of 86.51 µg/mL. Moreover, EGCG, ECG and EGC could be separated and have been documented previously to demonstrate strong antimicrobial activities [52].

Biofilms are microbial communities that develop on surfaces or interfaces (e.g., air and liquid) and are embedded in a three-dimensional matrix of self-produced extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), primarily including exopolysaccharides, nucleic acids, and proteins [53]. Their development involves the initial attachment of planktonic (free-swimming) microorganisms to a surface, followed by proliferation and EPS production, microcolony formation, maturation (i.e., development of a characteristic biofilm architecture), and detachment. Within biofilms, microorganisms are protected against the antimicrobial activities of various substances, including well-established antibiotics [54]. Herein, the green tea extract exhibited good antibiofilm activity (>50% inhibition of biofilm formation) against the performed biofilms of Campylobacter isolates. This may be attributed to the EGCG component of the analyzed extract, which has previously been shown to have antibiofilm activities against bacterial biofilms [55].

The molecular ways by which biofilms shield bacteria from antimicrobial action are multifactorial. The EPS structure hinders the penetration of specific antibiotics and can contain enzymes that actively inactivate the antibiotics through molecular modifications [56]. In addition, the dormant state of bacteria in biofilms may passively promote tolerance to antimicrobial substances [57]. On the other hand, the proximity of cells within biofilms and the environmental DNA in the EPS structure favor horizontal gene transfer. Accordingly, C. jejuni transmits chromosomally encoded antibiotic resistance genes more frequently in biofilms than in a bacterial planktonic manner [58]. In this study, significant down regulation of the biofilm biosynthesis gene and the quorum sensing regulator (FlaA and LuxS, respectively) are reported after treatment with green tea extract. Castillo et al. [44] found that the epigallocatechin ingredient of green tea could inhibit the movement and biofilm formation of Campylobacter species by phenotypic methods, though no molecular method could confirm their results.

Although this in vitro approach is considered an alternative to conventional antimicrobials, it is still ignored by medical practice due to the lack of suitable scientific and clinical evidence. Therefore, numerous in vivo studies should be carried out to assess the efficacy and safety of the medicinal plants in animal and human models. Despite the drawbacks of the in vitro model systems, it may be more suitable than in vivo models for the understanding of the mechanisms of drug-induced toxicity due to their lower structural and functional heterogeneity [59,60]. This is a preliminary in vitro validation of the natural products used to mitigate bacterial resistance. However, there is no way to support their clinical use in the treatment of gastroenteritis due to Campylobacter infection without in vivo studies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sampling

A total of 400 samples of various sources, comprising chicken (n = 290), the environment (n = 60) and human (n = 50), were collected from Zagazig city, Sharkia governorate, Egypt between September 2021 and December 2023. Chicken samples, including cloacal swabs, cecal parts, breast meat, thigh meat and neck skin (n = 50 each), gizzard, and liver (n = 20 each), were collected from recently slaughtered, apparently healthy broiler chickens from 20 different outlets, with each sample representing one bird. Environmental samples, including water, feed and litter (n = 20 each), were obtained from the same outlets. However, human feces were collected from gastroenteritis patients attending clinical laboratories. Samples were collected in sterile Bolton enrichment broth (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK) and transported to the laboratory within three hours in an ice box for bacteriological analysis. Collection of samples complied with the general guidelines of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt. The human study was performed according to the World Medical Associates Ethics (Declaration of Helsinki) for studies involving humans. Written informed consent was acquired from the patients participating in the investigation after a full explanation of the purpose of the study.

4.2. Isolation and Identification of Thermophilic Campylobacter Species

For the isolation of Campylobacter species, samples were incorporated in Bolton enrichment broth then incubated at 41 °C for 24 h in culture vessels with <1 cm and with firmly capped lids. After enrichment, a loopful of broth culture was streaked onto modified Cefoperazone Charcoal Deoxycholate agar (mCCDA, Oxoid, UK) prepared from Campylobacter blood-free selective agar base CM0739 and CCDA selective supplement SR0155 (Oxoid, UK). The plates were incubated at 41.5 °C in darkness for 48 h under microaerophilic condition (5% O2, 10% CO2 and 85% N2) using CamyGen sachets (Oxoid, UK) [61]. Presumptive identification of the isolates as C. jejuni or C. coli was performed adopting biochemical reactions including oxidase, catalase, indoxyl acetate and hippurate hydrolysis as well as their susceptibilities to cephalothin and nalidixic acid (30 µg/disc, each) [62].

4.3. Molecular Confirmation of Campylobacter Species

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was applied for the confirmation of Campylobacter species. DNA extraction was operated using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) obeying the guidelines provided by the manufacturer. Conventional PCR amplification procedures were performed to detect the 23S rRNA, mapA, and ceuE genes of genus Campylobacter, C. jejuni, and C. coli, respectively, using the oligonucleotide primer sets presented in Table S1 [63,64]. All PCR procedures were carried out in triplicate using the Emerald Amp GT PCR Master Mix (Takara, Mountain View, CA, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer`s instructions. The DNAs of C. jejuni (NCTC11322) and C. coli (NCTC11366) were included in all PCR assays as positive controls whereas PCR grade water was considered a negative control.

4.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Campylobacter isolates were examined for their susceptibilities to 13 antimicrobials representing different categories adopting the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method [65]. The antimicrobial classes included β-lactams [penicillin (P; 10 µg), ampicillin–sulbactam (AMS; 20 µg), amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (AMC; 30 µg) and cefotaxime (CTX; 10 µg)], aminoglycosides [gentamycin (CN; 10 µg)], fluoroquinolones [norfloxacin (NOR; 5 µg) and ciprofloxacin (CIP; 5 µg)], macrolides (erythromycin (E; 15 µg) and tylosin (TL; 15 µg)], phenicols [chloramphenicol (C; 30 µg)], tetracyclines [tetracycline (TE; 30 µg)], polypeptides [colistin (CT; 10 µg)], and sulphonamides [sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim (SXT (25 µg)] (Oxoid, UK). The interpretive criteria of the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute [66] and the European committee for antimicrobial susceptibility testing [67] were followed for analysis of the results. The multiple antimicrobial resistance (MAR) indices were estimated as previously documented [68] and MDR (resistance to ≥ three antimicrobial categories) were detected as documented elsewhere [69].

4.5. Quantitative Assessment of Biofilm Formation by Campylobacter Species

Induction of biofilm formation by Campylobacter isolates was performed in triplicate using flat-bottom 96-well polystyrene microtiter plate (Techno plastic products, Trasadingen, Swizerland) as presented elsewhere [70]. Briefly, 20 µL of 106 CFU/mL initial bacterial suspension in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Oxoid, UK) was put into each well, then incubated for 48 h at 41.5 °C. The wells were completely aspirated and underwent two rounds of washing with PBS (200 µL, pH 7.2) to remove the planktonic bacteria, they were then airdried for 15 min. Biofilms were stained with 100 µL/well of crystal violet (0.01% w/v) for 30 min. The wells were then washed twice with PBS and air-dried. After resuspending the stained biomass in an 80:20, v/v ethanol acetone solution, an ELISA reader (Stat-fax 2100, Foster City, CA, USA) was used to measure the optical density (OD) at 570 nm. Wells with non-inoculated medium and biofilm-producing bacterium were employed, respectively, as positive and negative controls. Campylobacter isolates were categorized using the cut-off optical density value (OD cut = OD avg of negative control + 3 × standard deviation (SD) of ODs negative control) based on biofilm formation ability as follows: no biofilm producers (OD ≤ DO cut), weak biofilm producers (OD cut ≤ OD × OD cut), moderate biofilm producer (2 × OD cut, OD ≤ 4 × OD cut) or strong biofilm producers (OD > 4 × OD cut) [71].

4.6. Plant Extracts and Their Preparation

Plant extracts of green tea (Camellia sinensis), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) and ginger (Zingiber officinale) were purchased from Makin Company, Egypt. The plant extracts were prepared according to Yam and coauthors [72] with a few modifications. In brief, 200 g of each plant powder was extracted into 500 mL of ethanol (70%) for 2 h. Then, high-speed centrifugation and filtration were used to remove the insoluble particles. The filtrate was reduced to 120 mL in a rotary evaporator then extracted five times with 180 mL of ethyl acetate. The organic phases were collected and concentrated to 25 mL at a rotary evaporator, 25 mL of distilled water was added before the remaining ethyl acetate and aqueous phase were freeze-dried. Five grams of the dried precipitate were dissolved in 100 mL of PBS (pH 7.4), which were used together as a stock solution of the forementioned plant extracts. Finally, two-fold serial dilution of the stock solutions, i.e., 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.12 and 1.56 mg/mL, were prepared in order to test their antimicrobial activities against MDR campylobacters.

4.7. Antimicrobial Activities of the Plant Extracts

The antimicrobial activities of green tea, rosemary and ginger plant extracts were estimated against drug-resistant Campylobacter isolates using the standard disc diffusion and broth microdilution techniques [73]. For the disc diffusion assay, 100 µL bacterial suspension of 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL in TSB was cultured in Muller–Hinton agar media (MHA, Oxoid, UK). A sterile Whatman No. 5 filter paper of 6 mm diameter (Machery-Magel, Doren, Germany) was impregnated with 20 µL of each plant extract at various concentrations (50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.12 and 1.56 mg/mL) then placed on the agar culture media and incubated under microaerophilic condition at 41.5 °C for 48 h. The inhibition zone diameters were measured in millimeters, and interpretation of results was reported as documented elsewhere [74]. A sterile filter paper disk soaked in 50 µL of PBS was considered a control negative, whereas an antibiotic disk of gentamycin (10 µg) was also used as a control positive.

The broth microdilution technique was carried out to determine the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of tested plant extracts against drug-resistant Campylobacter isolates using the 96-well culture plates. Two-fold serial dilutions of each plant extract were performed from the stock solution, then 100 µL of each dilution was dispended in 96-well culture plates. Thereafter, 100 µL of bacterial suspension was added to each well and incubated under a microaerophilic environment at 41.5 °C for 1–2 days. The lowest concentration of each plant extract exhibiting no growth was considered as MIC.

4.8. Antibiofilm Assay

The activities of natural antimicrobials on mature biofilms performed by Campylobacter isolates were studied using the microtiter plate technique as presented elsewhere [75] with modifications. In brief, 20 µL of bacterial suspension (106 cells/mL) was placed into each well containing 180 µL of TSB. After 24 h of biofilm development, the medium was withdrawn, and each well was washed by sterile PBS. Two hundred TSB microliters, having different concentrations of the green tea extract (SIC, MIC and 2MIC) were added, then incubated for 24 h. The biofilms that developed on the wells’ sides were stained for 15 min with 100 μL of 0.1% crystal violet and then washed again with PBS to remove the excess dye. The stained biofilms were then dissolved with 33% acetic acid for 15 min. The dissolved biofilms were transferred to a new 96-well microtiter plate and then measured using a microplate reader (PowerWave 340, Bio-tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) at 570 nm. The percentage of biofilm inhibition was determined using the following formula:

where A is the ELISA reader’s absorbance measurement at 570 nm (stat fax 2100, Awareness Technology, Palm City, FL, USA). Both a positive control (wells containing biofilms) and a negative control (a non-biofilm generator) were involved. All procedures were conducted in triplicate.

(A570 of the test/A570 of non-treated control isolate) × 100

4.9. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Analysis of Green Tea Extract

Green tea HPLC analysis was carried out using an Agilent 1260 series, Canada. The separation was carried out using Zorbax Eclipse Plus C8 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm). The mobile phase comprised water (A) and 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile (B) at a flow rate of 0.9 mL/min. The mobile phase was sequentially programmed using the following linear gradient: 0 min (82% A); 0–1 min (82% A); 1–11 min (75% A); 11–18 min (60% A); 18–22 min (82% A); 22–24 min (82% A). The multi-wavelength detector was monitored at 280 nm. The injection volume was 5 μL for each of the sample solutions. The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C [76].

4.10. Green Tea Analysis Using Liquid Chromatography–Electrospray Ionization–Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS) [77]

4.10.1. Quantitative Analysis of the Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents of Green Tea Extract

This was performed using LC-ESI-MS/MS with an ExionLC AC system for separation and a SCIEX Triple Quad 5500+ MS/MS system equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) for detection. For the negative ionization mode, the separation was performed using a Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (3.0 × 100 mm, 2.7 µm). The mobile phases consisted of two eluents; A: 0.1% formic acid in water and B: acetonitrile (LC grade). The mobile phase was programmed as mentioned in Table S2. The injection volume was 5 µL. The negative ionization mode was applied with the following mass spectrometer parameters; curtain gas: 25 psi, ion spray voltage: –4500, and source temperature: 400 °C. Ion source gases 1 and 2 were 55 psi with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) parameters, as described in Table 8.

Table 8.

Summary of optimized parameters for the quantitative analysis of the phenolic and flavonoid contents of green tea.

4.10.2. Non-Targeted Screening for Catechins (Qualitative Analysis)

The analysis of the sample was performed using LC-ESI-MS/MS with an ExionLC AC system for separation and SCIEX Triple Quad 5500+ MS/MS system equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) for detection. For the negative ionization mode, the separation was performed with an Ascentis® Express 90 Å C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 2.7 µm). The mobile phases consisted of two eluents; A: 5 mM ammonium formate, pH 8 and B: acetonitrile (LC grade). The mobile phase gradient was programmed as in Table S3. The flow rate was 0.25 mL/min, and the injection volume was 5 µL. For MS/MS analysis, negative ionization mode was applied with a scan (EMS-IDA-EPI) from 100 to 1000 Da for MS1 with the following parameters; curtain gas: 25 psi, ion spray voltage: −4500, source temperature: 500 °C. Ion source gases 1 and 2 were 45 psi and from 50 to 1000 Da for MS2 with a declustering potential of −80 and collision energy: −35.

For the positive ionization mode, the separation was performed with an Ascentis® Express 90 Å C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 2.7 µm). The mobile phases consisted of two eluents; A: 5 mM ammonium formate, pH 3 and B: acetonitrile (LC grade). The mobile phase gradient was programmed as depicted in Table S3.

4.11. Reverse Transcriptase Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

After biofilm formation, as described above, the strong biofilm producer Campylobacter isolates were separately exposed to the SIC of the green tea extract then incubated at 41.5 °C for 48 h. Campylobacter biofilms with no treatment were considered controls. Biofilms were precisely harvested then gently rinsed with PBS to remove the non-adherent cells. Total RNA was extracted from biofilms of both treated and untreated Campylobacter isolates using aQIAampRN easy Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Relative expression of the biofilm genes, FlaA and LuxS [78,79], were detected by one step RT-qPCR using the QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Germany) in the MX3005p real-time PCR thermal cycler (Stratagene, Lajolla, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each sample was subjected to RT-qPCR in triplicate, and the mean values were used for subsequent analysis. Oligonucleotide primer sequences involved in the RT-qPCR technique are shown in Table S1. Melting curves were created to confirm the amplified products’ specificity (one cycle of 94 °C for 1 min, 50 °C for 1 min, and 94 °C for 1 min for each of the FlaA and LuxS genes). The relative expression levels of the examined genes were normalized to the constitutive expression of the 23S rRNA housekeeping gene. Fold changes in the target gene’s transcript levels in treated Campylobacter biofilm producers, compared with their levels in untreated producers, were estimated according to the 2−∆∆CT method [80].

4.12. Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests were employed to confirm both the homogeneity and normality of variances. The occurrence of Campylobacter species in animals, alongside antimicrobial resistance, was analyzed using the chi-square test (χ2). The inhibitory effects of different concentrations of plant extracts on Campylobacter isolates were assessed through the Kruskal–Wallis test. Linear regression was utilized to determine the amount of decrease in the inhibition zone with each unit decrease in the concentration of various plant extracts. To investigate the significant differences in the MICs among different plant extracts, the Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test was applied. The significant distinctions in the optical density pre- and post-treatment were evaluated using the t-test. Fold changes in the expression of examined biofilm genes after treatment of Campylobacter isolates with the SICs of green tea extract were examined through a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

These results provide new perspectives on the antimicrobial possibility of natural herbal products against planktonic Campylobacter cells. Additionally, the current study demonstrates the anti-quorum sensing and antibiofilm activities of green tea against MDR biofilm-producing Campylobacter isolates using molecular methods. The knowledge gained from this study is an in vitro preliminary validation for the application of green tea extract as a promising therapy for the mitigation of Campylobacter resistance in veterinary medicine. However, further in vivo studies should be implemented in the future to confirm its predictions of safety, toxicity, and efficacy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antibiotics14010061/s1, Table S1: Oligonucleotide primers used in the study; Table S2: The mobile phase for quantitative analysis of the total phenolic and flavonoid contents of Camellia sinensis; Table S3: The mobile phase used for non-targeted screening for catechins (qualitative analysis).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.E., A.M.A., A.M.O.A. and N.K.A.E.-A.; methodology, M.S.E. and A.A.E.; validation, M.S.E., A.M.A., A.M.O.A., N.K.A.E.-A., A.A., E.P., G.D. and M.A.; formal analysis, M.S.E., A.M.O.A. and N.K.A.E.-A.; investigation, A.A., E.P., G.D. and M.A.; data curation, M.S.E., A.M.O.A., A.A.E. and N.K.A.E.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.E., A.M.O.A. and N.K.A.E.-A.; writing—review and editing, M.S.E., A.M.A., A.M.O.A., N.K.A.E.-A., A.A., E.P., G.D. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The human study was performed according to the World Medical Associates Ethics (Declaration of Helsinki) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was acquired from the patients participating in the investigation after a full explanation of the purpose of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Campylobacter. World Health Organisation Web Page. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/campylobacter (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Salehi, M.; Shafaei, E.; Bameri, Z.; Zahedani, S.S.; Bokaeian, M.; Mirzaee, B.; Mirfakhraee, S.; Rigi, T.B.; Akbari, M. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter jejuni. Int. J. Infect. 2014, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwaran, A.; Okoh, A.I. Human campylobacteriosis: A public health concern of global importance. Heliyon 2019, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donlan, R.M.; Costerton, J.W. Biofilms: Survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 15, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakura, H.; Yamasaki, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Igimi, S. Deletion of peb4 gene impairs cell adhesion and biofilm formation in Campylobacter jejuni. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007, 275, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvers, K.T.; Park, S.F. Quorum sensing in Campylobacter jejuni: Detection of a luxS encoded signalling molecule. Microbiology 2002, 148 Pt 5, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmokoff, M.; Lanthier, P.; Tremblay, T.L.; Foss, M.; Lau, P.C.; Sanders, G.; Austin, J.; Kelly, J.; Szymanski, C.M. Proteomic analysis of Campylobacter jejuni 11,168 biofilms reveal a role for the motility complex in biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 4312–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Park, C.; Kim, Y.J. Role of flgA for flagellar biosynthesis and biofilm formation of Campylobacter jejuni NCTC11168. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 1871–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Hu, W.; Tian, Z.; Yuan, D.; Yi, G.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Zhu, J.; Li, M. Developing natural products as potential anti-biofilm agents. Chin. Med. 2019, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.C.; Targino, B.N.; Gonçalves, A.G.; Silva, M.R.; Hungaro, H.M. Campylobacter: An important food safety issue. In Food Safety and Preservation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 391–430. [Google Scholar]

- Ammar, A.M.; El-Hamid, A.; Marwa, I.; El-Malt, R.M.S.; Azab, D.S.; Albogami, S.; Al-Sanea, M.M.; Soliman, W.E.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Bendary, M.M. Molecular detection of fluoroquinolone resistance among multidrug-, extensively drug-, and pan-drug-resistant Campylobacter species in Egypt. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roua, M.A.; Altuwijri, L.A.; Aldosari, N.S.; Alsakabi, N.; Dawoud, T.M. Antimicrobial and synergistic properties of green tea catechins against microbial pathogens. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2024, 36, 103277. [Google Scholar]

- Alimohammadi, Z.; Shirzadi, H.; Taherpour, K.; Rahmatnejad, E.; Khatibjoo, A. Effects of cinnamon, rosemary and oregano on growth performance, blood biochemistry, liver enzyme activities, excreta microbiota and ileal morphology of Campylobacter jejuni-challenged broiler chickens. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 10, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamedin, A.; Elsayed, A.; Shakurfow, F.A. Molecular effects and antibacterial activities of ginger extracts against some drug resistant pathogenic bacteria Egypt. J. Bot. 2018, 58, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.M.; Seong, B.L. Tea catechins as a potential alternative anti-infectious agent. Expert Rev. Anti-infect. Ther. 2007, 5, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akela, M.A.; El-Atrash, A.; El-Kilany, M.I.; Tousson, E. Qualitative and quantitative characterization of biologically active compounds of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) Leaf Extract. J. ATBAS 2018, 2, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tousson, E.; Masoud, A.; Hafez, E.; Almakhatreh, M. Protective role of rosemary extract against etoposide induced liver toxicity, injury and KI67 alterations in rats. J. Biosci. Appl. Res. 2019, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsherbiny, M.A.; Abd-Elsalam, W.H.; El Badawy, S.A.; Taher, E.; Fares, M.; Torres, A.; Chang, D.; Li, C.G. Ameliorative and protective effects of ginger and its main constituents against natural, chemical and radiation-induced toxicities: A comprehensive review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 123, 72–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Aziz, N.K.; Ammar, A.M.; Hamdy, M.M.; Gobouri, A.A.; Azab, E.; Sewid, A.H. First report of aacC5-aadA7Δ4 gene cassette array and phage tail tape measure protein on class 1 integrons of Campylobacter species isolated from animal and human sources in Egypt. Animals 2020, 10, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Li, T.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, W.; Sukumaran, A.T.; Kiess, A.S.; Zhang, L. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and molecular characterization of Campylobacter isolated from broilers and broiler meat raised without antibiotics. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 1, e00251-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, F.L.; Doyle, M.P. Health risks and consequences of Salmonella and Campylobacter jejuni in raw poultry. J. Food Protec. 1995, 58, 326–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, K. Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. and its pathogenic genes in poultry meat, human and environment in Aswan, Upper Egypt. Assiut Vet. Med. J. 2019, 65, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa, N.O.; Afify, J.S.A.; Rabie, N.S. Zoonotic and molecular characterizations of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from beef cattle and children. Glob. Vet. 2013, 11, 585–591. [Google Scholar]

- El-Naenaeey, E.Y.; Abd El-Aziz, N.K.; Sewid, A.H.; Hashem, A.; Hefny, A.A. Antimicrobial resistance, virulence-associated genes, and flagellin typing of thermophilic Campylobacter species isolated from diarrheic humans, raw milk, and broiler niches. Slov. Vet. Res. 2021, 58 (Suppl. S24), 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadallah, M.; Ahmed, H.; El-Gedawy, A.; Saad, A. Molecular identification of C. jejuni and C. coli in chicken and humans, at Zagazig, Egypt, with reference to the survival of C. jejuni in chicken meat at refrigeration and freezing temperatures. Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 21, 1801–1812. [Google Scholar]

- Chatur, Y.A.; Brahmbhatt, M.N.; Modi, S.; Nayak, J.B. Fluoroquinolone resistance and detection of topoisomerase gene mutation in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from animal and human sources. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 773–783. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Mendoza, D.; Martínez-Flores, I.; Santamaría, R.I.; Lozano, L.; Bustamante, V.H.; Pérez-Morales, D. Genomic analysis reveals the genetic determinants associated with antibiotic resistance in the zoonotic pathogen Campylobacter spp. distributed Globally. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 513070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasti, J.I.; Gross, U.; Pohl, S.; Lugert, R.; Weig, M.; Schmidt-Ott, R. Role of the plasmid-encoded tet(O) gene in tetracycline-resistant clinical isolates of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 56, 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Baaboua, A.; El Maadoudi, M.; Bouyahya, A.; Kounnoun, A.; Bougtaib, H.; Belmehdi, O. Prevalence and antimicrobial profiling of Campylobacter spp. isolated from meats, animal, and human faeces in Northern of Morocco. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 349, 109202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debelo, M.; Mohammed, N.; Tiruneh, A.; Tolosa, T. Isolation, identification and antibiotic resistance profile of thermophilic Campylobacter species from bovine, knives and personnel at Jimma Town Abattoir, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Dong, J.; Cheng, Y.; Lu, Q.; Luo, Q.; Wen, G.; Liu, G.; Shao, H. Genotypic diversity, antimicrobial resistance and biofilm-forming abilities of Campylobacter isolated from chicken in Central China. Gut Pathog. 2017, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.M.; Abd El-Hamid, M.I.; Eid, S.E.A.; El Oksh, A.S. Insights into antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes of emergent multidrug resistant avian pathogenic Escherichia coli in Egypt: How closely related are they? Rev. Med. Vet. 2015, 166, 304–314. [Google Scholar]

- Samad, A.; Abbas, F.; Ahmed, Z.; Akbar, A.; Naeem, M.; Sadiq, M.B.; Ali, I.; Saima; Roomeela; Bugti, F.S.; et al. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility, and virulence of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from chicken meat. J. Food Saf. 2019, 39, 12600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Aziz, N.K.; Abd El-Hamid, M.I.; Bendary, M.M.; El-Azazy, A.A.; Ammar, A.M.; Abd El-Aziz, N.K.; Abd El-Hamid, M.I.; Bendary, M.M.; El-Azazy, A.A.; Ammar, A.M. Existence of vancomycin resistance among methicillin resistant S. aureus recovered from animal and human sources in Egypt. Slov. Vet. Res. 2018, 55, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Aziz, N.K.; Ammar, A.M.; El-Naenaeey, E.Y.M.; El Damaty, H.M.; Elazazy, A.A.; Hefny, A.A.; Shaker, A.; Eldesoukey, I.E. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm potentials of cinnamon oil and silver nanoparticles against Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from bovine mastitis: New avenues for countering resistance. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahim, A.E.; Abd El-Aziz, N.K.; Elariny, E.Y.T.; Shindia, A.; Osman, A.; Hozzein, W.N.; Alkhalifah, D.H.M.; El-Hossary, D. Antibacterial activity of bioactive compounds extracted from red kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) seeds against multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1035586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelatti, M.A.I.; Abd El-Aziz, N.K.; El-Naenaeey, E.-s.Y.M.; Ammar, A.M.; Alharbi, N.K.; Alharthi, A.; Zakai, S.A.; Abdelkhalek, A. Antibacterial and anti-efflux activities of cinnamon essential oil against pan and extensive drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from human and animal sources. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, S.M.; Abd El-Aziz, N.K.; Abdelkhalek, A.; Pet, I.; Ahmadi, M.; El-Nabtity, S.M. Chitosan-loaded Lagenaria siceraria and Thymus vulgaris potentiate antibacterial, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory activities against extensive drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: In Vitro and in vivo approaches. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, M. The world is running out of antibiotics. Aust. Med. 2017, 29, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Reygaert, W.C. Green tea catechins: Their use in treating and preventing infectious diseases. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 9105261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butucel, E.; Balta, I.; Ahmadi, M.; Dumitrescu, G.; Morariu, F.; Pet, I.; Stef, L.; Corcionivoschi, N. Biocides as biomedicines against foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftei, N.-M.; Raileanu, C.R.; Balta, A.A.; Ambrose, L.; Boev, M.; Marin, D.B.; Lisa, E.L. The potential impact of probiotics on human health: An update on their health-promoting properties. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcionivoschi, N.; Balta, I.; Butucel, E. Natural antimicrobial mixtures disrupt attachment and survival of E. coli and C. jejuni to non-organic and organic surfaces. Foods 2023, 12, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, S.; Heredia, N.; Garcia, S. 2(5H)-Furanone, epigallocatechin gallate, and a citricbased disinfectant disturb quorum-sensing activity and reduce motility and biofilm formation of Campylobacter jejuni. Folia Microbiol. 2015, 60, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, M.; Henika, P.R.; Mandrell, R.E. Bactericidal activities of plant essential oils and some of their isolated constituents against Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella enterica. J. Food Prot. 2002, 65, 1545–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu-Ingok, A.; Catalkaya, G.; Capanoglu, E.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of fennel, ginger, oregano and thyme essential oils. Food Front. 2021, 2, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giriraju, A.; Yunus, G.Y. Assessment of antimicrobial potential of 10% ginger extract against Streptococcus mutans, Candida albicans, and Enterococcus faecalis: An in vitro study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2013, 24, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanissery, R.; Smith, D.P. Marinade with thyme and orange oils reduces Salmonella Enteritidis and Campylobacter coli on inoculated broiler breast fillets and whole wings. Poult. Sci. 2014, 93, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeddes, W.; Majdi, H.; Gadhoumi, H.; Affes, T.G.; Mohamed, S.N.; Wannes, W.A. Optimizing ethanol extraction of rosemary leaves and their biological evaluations. J. Explor. Res. Pharmacol. 2022, 7, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegara, S.; Funes, L.; Martí, N.; Saura, D.; Micol, V.; Valero, M. Bactericidal activities against pathogenic bacteria by selected constituents of plant extracts in carrot broth. Food Chem. 2011, 128, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Wei, S.; Su, H.; Zheng, S.; Xu, S.; Liu, M.; Bo, R.; Li, J. Bactericidal activity of gallic acid against multi-drug resistance Escherichia coli. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 173 Pt A, 105824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyvani-Ghamsari, S.; Rahimi, M.; Khorsand, K. An update on the potential mechanism of gallic acid as an antibacterial and anticancer agent. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5856–5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrascosa, C.; Raheem, D.; Ramos, F.; Saraiva, A.; Raposo, A. Microbial biofilms in the food industry-a comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Misba, L.; Khan, A.U. Antibiotics versus biofilm: An emerging battleground in microbial communities. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, S.; Yang, D.; Zhao, L.; Shi, F.; Ye, G.; Fu, H.; Lin, J.; Guo, H.; He, R.; Li, J.; et al. EGCG-mediated potential inhibition of biofilm development and quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.W.; Mah, T.F. Molecular mechanisms of biofilm-based antibiotic resistance and tolerance in pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 276–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, O.E.; Sauer, K. Escaping the biofilm in more than one way: Desorption, detachment or dispersion. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2016, 30, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Oh, E.; Jeon, B. Enhanced transmission of antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter jejuni biofilms by natural transformation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. J. 2014, 58, 7573–7575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Lin, Y. Traditional Chinese medicine: An approach to scientific proof and clinical validation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 86, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, J.C.; Rodriguez, R.J.; Melchert, R.B.; Acosta, D., Jr. Predictive value of in vitro model systems in toxicology. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1998, 38, 63–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, F.J.; Hutchinson, D.N.; Coates, D. Blood-free, selective medium for isolation of C. jejuni from feces. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1984, 19, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, P.J.; Carter, M.E.; Markey, B.; Carter, G.R. Clinical Veterinary Microbiology, 1st ed.; Wolf publishing Mosby: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, E.; Lee, Y.H. Comparison of three different methods for Campylobacter isolation from porcine intestines. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 19, 647–650. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Clark, C.G.; Taylor, T.M.; Pucknell, C.; Barton, C.; Price, L.; Woodward, D.L.; Rodgers, F.G. Colony multiplex PCR assay for identification and differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, C. lari, C. upsaliensis, and C. fetus subsp. fetus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 4744–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disc method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1966, 45, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. In CLSI Supplement M100, 30th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 7.1, 2017. Available online: https://www.megumed.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/v_14.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pan-drug resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, R.; Dahiya, S.; Sayal, P. Evaluation of multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index and doxycycline susceptibility of Acinetobacter species among inpatients. Indian J. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 3, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tendolkar, P.M.; Baghdayan, A.S.; Gilmore, M.S.; Shankar, N. Enterococcal surface protein, Esp, enhances biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecalis. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 6032–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanović, S.; Vuković, D.; Hola, V.; Bonaventura, G.D.; Djukić, S.; Ćirković, I.; Ruzicka, F. Quantification of biofilm in microtiter plates: Overview of testing conditions and practical recommendations for assessment of biofilm production by Staphylococci. APMIS 2007, 115, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, T.S.; Shah, S.; Hamilton-Miller, J.T.M. Microbiological activity of whole and fractionated crude extract of tea (Camellia sinensis) and of tea components. FEMS. Microbiol. Lett. 1997, 152, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fani, M.M.; Kohanteb, J. Inhibitory activity of Aloe vera gel on some clinically isolated cariogenic and periodontopathic bacteria. J. Oral Sci. 2012, 54, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, O.; Choi, S.K.; Kim, J.; Park, C.G.; Kim, J. In vitro antibacterial activity and major bioactive components of Cinnamomum verum essential oils against cariogenic bacteria, Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2016, 4, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, A.F.; Ali, F.; Khan, I.A.; Shwal, A.S.; Arora, D.S.; Shah, B.A.; Taneja, S.C. Antistaphylococcal and biofilm inhibitory activities of acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid from Boswellia serrata. BMC Microbiol. 2011, 11, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Yao, K.; Jia, D.; Fan, H.; Liao, X.; Shi, B. Determination of total catechins in tea extracts by HPLC and spectrophotometry. Nat. Prod. Res. 2009, 23, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olech, M.; Nowak, R.; Los, R.; Rzymowska, J.; Malm, A.; Chruściel, K. Biological activity and composition of teas and tinctures prepared from Rosa rugosa Thunb. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2012, 7, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Meng, J.; Zhao, S.; Singh, R.; Song, W. Adherence to and invasion of human intestinal epithelial cells by Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates from retail meat products. J. Food Prot. 2006, 69, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, B.R.; Upadhyay, A.; Upadhyaya, I.; Shrestha, S.; Arsi, K.; Liyanage, R.; Venkitanarayanan, K.; Donoghue, D.J.; Donoghue, A.M. Trans-cinnamaldehyde, eugenol and carvacrol reduce Campylobacter jejuni biofilms and modulate expression of select genes and proteins. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.S.; Reed, A.; Chen, F.; Stewart, C.N. Statistical analysis of real-time PCR data. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).