Abstract

Background: Ceftobiprole is a fifth-generation cephalosporin that has been approved in Europe solely for the treatment of community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonia. The objective was to analyze the use of ceftobiprole medocaril (Cefto-M) in Spanish clinical practice in patients with infections in hospital or outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT). Methods: This retrospective, observational, multicenter study included patients treated from 1 September 2021 to 31 December 2022. Results: A total of 249 individuals were enrolled, aged 66.6 ± 15.4 years, of whom 59.4% were male with a Charlson index of four (IQR 2–6), 13.7% had COVID-19, and 4.8% were in an intensive care unit (ICU). The most frequent type of infection was respiratory (55.8%), followed by skin and soft tissue infection (21.7%). Cefto-M was administered to 67.9% of the patients as an empirical treatment, in which was administered as monotherapy for 7 days (5–10) in 53.8% of cases. The infection-related mortality was 11.2%. The highest mortality rates were identified for ventilator-associated pneumonia (40%) and infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococus aureus (20.8%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (16.1%). The mortality-related factors were age (OR: 1.1, 95%CI (1.04–1.16)), ICU admission (OR: 42.02, 95%CI (4.49–393.4)), and sepsis/septic shock (OR: 2.94, 95%CI (1.01–8.54)). Conclusions: In real life, Cefto-M is a safe antibiotic, comprising only half of prescriptions for respiratory infections, that is mainly administered as rescue therapy in pluripathological patients with severe infectious diseases.

1. Introduction

There has been a disturbing increase in multi-resistant microorganisms worldwide over the past decade [1], presenting clinicians with major diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. This phenomenon has been associated with a rise in the failure of empirical antibiotic therapies [2] and with a delay before the administration of an effective drug [3], thereby increasing mortality rates [4]. The rate of carbapenemase-resistant Pseudomonas spp. is currently >20% in Spain [1], mainly due to efflux pumps and porin losses. Therefore, carbapenem sparing strategies are recommended to attempt to decrease the rate of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. A randomized controlled trial (MERINO) reported a lower mortality rate using meropenem than using piperacillin/tazobactam in patients with ceftriaxone-resistant Escherichia coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections. The findings did not support the utilization of piperacillin-tazobactam against these infections [5]. This has fostered the administration of bactericide antibiotics other than piperacillin/tazobactam to treat gram-negative bacteria such as P. aeruginosa, including ceftobiprole. Ceftobiprole medocaril (Cefto-M) is a broad-spectrum, fifth-generation cephalosporin against gram-negative cocci and bacilli, ranging from methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) to ampicillin-susceptible Enterococcus faecalis, faecium, and P. aeruginosa. It is not affected by efflux pumps or porin losses [6]. It has a spectrum of potential interest for the treatment of catheter-related bacteremia, endocarditis, or complicated urine infections. In an experimental study, the bactericide capacity of Cefto-M in biofilm was higher than that of linezolid, vancomycin, or daptomycin against infections caused by MRSA, methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), or coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) [7]. It may, therefore, be useful for treating infections related to devices (intracardiac, cranial leads, etc.), prosthetic valves, endoprostheses, or osteosynthesis materials. It has demonstrated a similar effectiveness to that of other antibiotics in skin and soft tissue infections [8]. Nevertheless, it has only been approved in Europe for the treatment of community-acquired (CAP) and nosocomial (NP) pneumoniae, excluding ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP).

Clinical trials are the gold standard for approving novel pharmaceutical products or therapies. However, they can differ from actual clinical experience due to their strict eligibility criteria and optimal conditions. Real-world data can help bridge this gap, thereby supporting and accelerating the incorporation of effective new therapies and technologies into routine clinical practices [9]. However, sample sizes have been limited in previous real-life studies on Cefto-M [10]. With this background, this real-life study in Spain was designed to examine the routine administration of Cefto-M in patients with any type of infection in hospital or receiving outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT), considering the health and safety outcomes and the mortality-related factors.

2. Results

2.1. Cohort Description

The study included 249 individuals with a mean age of 66.6 ± 15.4 years. A total of 59.4% were male and 92.8% were Caucasian with a mean age-adjusted Charlson index of four (IQR 2–6) and 49.4% had cardiovascular risk factors, primarily cardiovascular disease (31.3%), arterial hypertension (29.3%), and diabetes mellitus (28.1%). A total of 20.9% were immunosuppressed, 14.1% had chronic kidney failure, and 11.6% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Table 1). The infection origin was nosocomial/healthcare-related in 57% of the patients. Cefto-M was administered in hospital to 95.6% of the patients (80.4% in the medical department) and as OPAT in 4.4% of the patients. Sepsis was present in 26.5%, septic shock in 4.4%, and concomitant COVID-19 infection in 13.7% of the patients. The median number of foci was one (IQR: 1–1). The type of infection was respiratory in 55.8% (CAP in 24.1%, NP in 24.9%, and VAP in 2%); skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) in 21.7%; and bacteremia in 17.7% of the patients (catheter-related in 2.8% and no focus in 14.9%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Epidemiological characteristics, comorbidities, and infection pathways.

2.2. Microbiological Isolation

Microbiological isolates were obtained from 137 patients (55%) and were polymicrobial in 56 (40.6%). Among the isolates, 87 (35.3%) were gram-positive cocci (GPC), 20 (22.9%) of which were coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), including 13 (65%) that were methicillin-resistant. A total of 46 (18.4%) were S. aureus, including 21 (45.6%) methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and 24 (52.3%) methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) isolates. A total of nine (10.3%) were Enterococcus spp., including eight (88.9%) E. faecalis and one (11.1%) ampicillin-susceptible E. faecium isolates. A total of 10 (11.5%) were Streptococcus spp., including five (50%) S. pneumoniae and five (50%) Streptococci of other species. A total of 49 were gram-negative bacilli (GNB), including 13 (26.5%) multi-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae, 31 (63.3%) non-fermenting GNB (100% P. aeruginosa), and five (10.2%) GNB of other species (Hemophilus influenzae [2], Morganella spp. [2], and Moraxella spp. [1]). Table 2 lists the other variables.

Table 2.

Microbial isolates.

All the isolated microorganisms treated with Cefto-M were susceptible to this drug (three MRSA, three MSSA, one enterococcus, one streptococcus, and 10 GNB, including four P. aeruginosa). Among the GPC, 97.2% (n = 35) were susceptible to vancomycin (100% of MRSA, 93.3% of MSSA, and 100% of both enterococci and streptococci). In terms of the GNB susceptibility, 83.3% of the P. aeruginosa isolates were susceptible to meropenem, 40% to cefepime, and 70% to piperacillin/tazobactam (Table 3).

Table 3.

Susceptibility of microbial isolates.

2.3. Outcomes

The median (IQR) stay was 20 (13–32) days. The total Cefto-M dose per patient was 10.5 (7.5–15) g for 7 days (5–10), what was administered in monotherapy to 134 patients (53.8%). It was prescribed as an empirical antibiotic treatment in 67.9% of the patients, and was appropriate in 82.8% of these. It was used as a first-line antibiotic in 74 (29.7%) patients and a second-line or more in 176 (70.3%). It was administered due to the failure of previous antibiotic therapy in 33.7% of the patients and after receiving the microbiology results from 26.1%. The death of 54 patients (21.7%) during the 6-month follow-up was directly attributable to infection in 28 (11.2%) patients, 17 (60.7%) of whom died during the first 14 days, nine (32.1%) between days 15 and 28, and two (7.1%) between day 29 and 6 months. Readmission for the same reason was recorded in 15 patients (6%) and for recurrence during the first month of follow-up in three (1.2%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes.

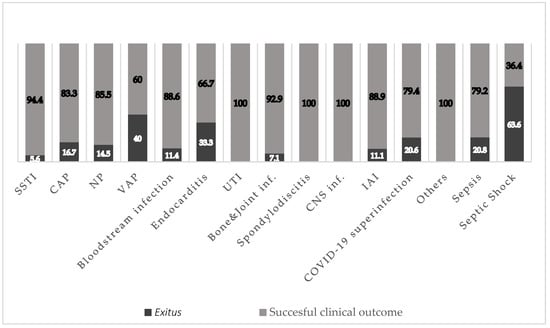

The mortality rate by infection type was 16.7% (10/60) for CAP, 14.5% (9/62) for NP, 40% (2/5) for VAP, 11.4% (5/44) for bacteremia, 5.6% (3/54) for SSTI, and 20% (7/34) for concomitant COVID-19 infection (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical outcomes by the primary infection type (n = 249). SSTI: skin and soft tissue infection, CAP: community-acquired pneumonia; NP: nosocomial pneumonia; VAP: ventilator-associated pneumonia; UTI: urinary tract infection; CNS: central nervous system; IAI: intra-abdominal infection; Exitus: death.

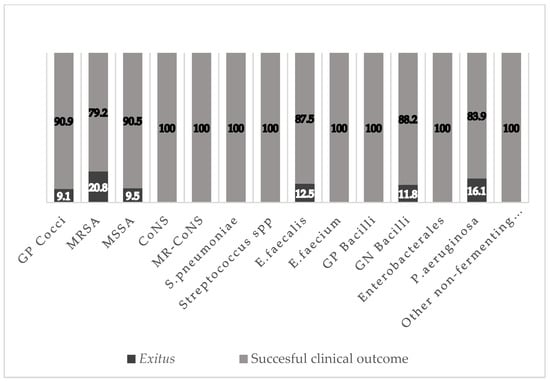

The mortality rate was 9.1% (8/88) for infections caused by GPC (MRSA 20.8% [5/24], E. faecalis 12.5% [1/8], MSSA 9.5% [2/21], CNS-MR 0% [0/13], Pneumococcus 0% [0/5], E. faecium S-ampicillin 0% [0/1], S. pneumoniae 0% [0/5], and Streptococcus spp. 0% [0/5]). The mortality rate was 11.8% (6/51) for infections caused by GNB (P. aeruginosa 16.1% [5/31], multi-susceptibility Enterobacteriaceae 0% [0/12], and other non-fermenting GNB 0% [0/2]), and 0% in infections by gram-positive bacilli (0/1) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinical outcomes of the microbial isolates. GP: gram-positive; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA: methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; CoNS: coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp; MR-CoNS: methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp; GN: gram-negative; GNB: gram-negative bacilli; Exitus: death.

2.4. Adverse Effects

No adverse effect was recorded in 96.4% of the treated patients, a mild effect in 1.6%, and a moderate effect in 1.6%. No patient abandoned the treatment due to adverse effects. Mild hypertransaminasemia was reported in 1.2% of the patients; diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting in 0.8%; and skin rash in 0.4% (Table 5).

Table 5.

Adverse drug effects.

2.5. Bi- and Multivariate Analyses of Mortality-Related Factors

In the bivariate analysis, mortality was associated with higher age (76.7 ± 13.3 vs. 65.3 ± 15.2 yrs.; p = 0.0001), ICU admission (28.6 vs. 2.1%; p = 0.001), cardiovascular risk factors (78.6 vs. 45.7%, p =0.001), underlying neurological disease (21.4 vs. 6.8%; p = 0.019), immunodepression (35.7 vs. 19%; p = 0.04), sepsis/septic shock (57.1 vs. 27.6%; p = 0.0001), VAP (7.1 vs. 1.4%, p = 0.04), fewer days of Cefto-M treatment (six [P25–P75: 3–8.5] vs. seven [P25–P75: 5–10] days, p = 0.029), and a lower total dose (in mg) of Cefto-M (nine [4.5–12.75] vs. 10.5 [7.5–15], p = 0.049). Hospitalization in a department/unit of infectious diseases emerged as a protective factor (24.9% vs. 7.1%; p = 0.035).

In the multivariate analysis, the factors associated with infection-related mortality were age (OR: 1.1 95% CI [1.04–1.16]), sepsis/septic shock (OR 2.94, 95% CI [1.01–8.54]), and ICU admission (OR 42.02, 95% CI [4.49–393.4]) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Mortality risk factors: bivariate and multivariate analyses.

3. Discussion

The patients in this real-life study were elderly, largely male, and pluripathological, with a high comorbidity index and a predominance of cardiovascular risk factors. Around one in five were immunodepressed, one in seven had kidney failure, and one in ten had COPD. More than half of the infections were nosocomial or healthcare-related, and approx. 5% received OPAT. As in the case of other beta-lactams, the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Cefto-M favor its infusion for 24 h, making it a potentially useful antibiotic for OPAT regimens in the patients with infections caused by GPC, including MRSA and ampicillin-susceptible Enterococcus spp., and by non-ESLB-producing GNB such as Pseudomonas spp. [11].

More than one-third of the participants had sepsis/septic shock, and one-seventh were co-infected with SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Septic shock was described as an independent mortality risk factor with an increase in the risk of up to 12% for every hour in shock, regardless of the focus, isolate, type of poly/monomicrobial infection, or presence/absence of bacteremia [12]. A multicenter study of more than 5000 individuals with septic shock reported a mortality rate of approx. 50% when the antibiotic treatment was appropriate and 89% when it was not [13]. Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 in critical patients with NP or VAP has been known to worsen the prognosis, although it does not increase the rate of invasive fungal infection or change the type of microorganism isolated at respiratory level [14]. In the present study, only approx. half of the patients received Cefto-M for respiratory infections (half NP and half CAP), which is the sole indication for this antibiotic in Spain [15]. One-fifth of the patients were treated for skin/soft tissue infections and one-sixth for bacteremia. Cefto-M was effective against Enterococcus in a murine model of a UTI [16] and was proposed as a possible treatment for a complicated UTI produced by Pseudomonas spp. [17]. Three non-inferiority clinical trials in the patients with skin and soft tissue infections reported no difference between Cefto-M and its comparators in terms of clinical or microbiological responses or safety profiles [18]. The decisions of clinicians to prescribe Cefto-M to the remaining patients in this real-life study were supported by pharmacokinetic [19] and in vitro [20] studies. In addition, Cefto-M was used to treat gram-negative bacterial (GNB) infections to avoid the utilization of carbapenems and help reduce the incidence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Furthermore, in the cases of infection caused by methicillin-resistant CGP such as MRSA, which were all susceptible to vancomycin, Cefto-M was prescribed instead of this lipoglycopeptide due to its rapid bactericidal activity, high volume of distribution to tissues, and excellent safety profile. Only two real-life studies have been published on this issue, one with only 51 patients [10] and a recent study [21] with a smaller sample size (n = 198) than in the present investigation (n = 249).

The total crude infection-related mortality in these patients was 11.2%, most frequently due to VAP (40%), followed by pneumonia with COVID-19 co-infection (20%), CAP requiring hospitalization (16.7%), NP (14.5%), bacteremia (11.4%), and skin/soft tissue infections (5.6%). Among the microorganisms, the highest mortality rates were for MRSA (20.8%) and P. aeruginosa (16.1%). The mortality rate was <1% in the clinical trials of Cefto-M in the patients with CAP. The difference between the present findings might be explained by their stricter eligibility criteria, with the exclusion of the patients receiving an antibiotic for >24 h in the previous three days and those with aspiration pneumonia, viral respiratory infections, polymicrobial infections, or radiological or clinical suspicions of atypical pneumonia [22]. In the trial for the patients with NP, the total mortality rate was 16.7% and the infection-attribution rate was 5.9%. This major discrepancy with the present findings can again be attributed to the trial eligibility criteria, which excluded the patients receiving systemic antibiotic treatment for >24 h in the previous two days and those with severe kidney failure or liver failure, evidence of infection with ceftazidime- or Cefto-M-resistant pathogens, and clinical circumstances potentially hampering the evaluation of the effectiveness, e.g., sustained shock, active tuberculosis, pulmonary abscess, or post-obstructive pneumonia [23].

Only one patient (0.4%) had a severe complication. However, the treatment was not withdrawn from any patient due to an adverse effect, similar to the findings of a single-center real-life study on the use of Cefto-M in 29 patients with infections in a third-level hospital [24].

Finally, the main factors related to mortality in this cohort of Cefto-M-treated patients were older age (the mean age of the patients was 76.7 years), the presence of sepsis/septic shock, and ICU admission, which have all been independently related to higher infection-related mortality rates in the previous studies [25].

The study was limited by its retrospective design and possible selection bias. Its strengths included its multicenter design, sample size (largest to date), and real-life nature, reflecting as faithfully as possible the utilization of Ceftobiprole-M in routine clinical practices in Spain.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

This real-life, retrospective, multicenter, observational, and descriptive study on the use of Cefto-M included patients in hospital or receiving OPAT with nosocomial/nosohusial or community-acquired infections from 12 Spanish centers in six autonomous communities (Andalusia, Madrid, Cataluña, Valencia, Murcia, and Cantabria). The study period was from the time of the drug’s approval in 2021 to 31 December 2022. The study was approved by the Provincial Ethics Committee of Granada (ref: 0095-N-22), with no requirement for the informed consent of the patients. All the data were gathered in accordance with the Spanish personal data protection legislation (Organic Law 3/5 December 2018) and the Declaration of Helsinki.

This descriptive study did not involve a pharmacological intervention. The treatments were always prescribed by the attending physicians according to their clinical practice.

The inclusion criteria was as follows: age > 17 years; receipt of Cefto-M as the first-line or rescue treatment for ≥48 h (≥six vials in the patients with normal renal function, creatinine clearance-adjusted in the patients with kidney failure); and ≥30 days of follow-up post-discharge or, in the case of the patients with osteomyelitis o endocarditis, ≥6 months post-discharge.

The exclusion criteria was as follows: pregnancy, allergy to beta-lactams, or any formulation excipient.

4.2. Variables and Definitions

The variables of this study included the following: age, sex, ethnicity, days of hospitalization (dates of admission and discharge), prescribing hospital department, age-adjusted Charlson index, and comorbidities.

The infection types in this study included the following: bacteremia (complicated/non-complicated], endocarditis (definite/probable/suspected, native/early prosthetic/late prosthetic/on pacemaker), respiratory infection (upper tract/CAP/NP/VAP), urinary tract infection (UTI), central nervous system infection, spondylodiscitis, osteoarticular infection, intra-abdominal infection, or other foci of infection. The etiology of the infections in this study included the following: community or nosocomial/nosohusial/healthcare-related; sepsis or septic shock, monomicrobial/polymicrobial infection, and co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19).

In this study, Cefto-M was administration as monotherapy or combination therapy (for the same infection); empirical or targeted administration; first-line or rescue (due to poor response to previous antibiotherapy, microbiology results, or toxicity with previous antibiotherapy), and was based on the days of administration, dose, and adverse events.

Previous antibiotic (for same infection) with treatment duration.

The microbiology for this study consisted of the microorganism causing the infection and the antibiogram according to the EUCAST criteria [26]. The EUCAST cutoff points were as follows for: Staphylococci (Vancomycin (S. aureus): 2; Vancomycin (CoNS): 4; Oxacillin (S. aureus): 2; Oxacillin (CoNS): 0.25); Enterococci (Vancomycin: 4); Pneumococci (Cefepime: 1; Ceftobiprole: 0.5; Vancomycin: 2; Meropenem: 2); Enterobacteriaceae (Cefepime: 1; Ceftobiprole: 0.25; Meropenem: 2); and Pseudomonas aeruginosas (Cefepime: 0.001; Ceftobiprole: insufficient evidence; Meropenem: 2).

Infection-related mortality at 14 and 28 days (at 6 months for endocarditis or osteomyelitis); readmission for the same reason during the first month; and relapse/recurrence of the infection.

The definitions of the terms used in this study are as follows.

- -

- Nosocomial infection: onset > 72 h after hospitalization.

- -

- Nosohusial/nosocomial infection: healthcare-related (day hospital, residence, day center for elderly).

- -

- The age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index was used to estimate the 10-year life expectancy of the patients as a function of their age and the presence of comorbidities at admission for the infectious episode [27].

- -

- Sepsis/septic shock: refractory hypotension and end-organ perfusion dysfunction despite adequate fluid resuscitation [28].

- -

- Immunodepression: congenital or acquired immunodeficiency or receipt of immunosuppressive treatment [29].

- -

- Relapse/recurrence of the infection was defined by a second episode within three months [30].

- -

- The adverse effect classification used in this study is as follows.

- -

- Mild: required no antidote or treatment; brief hospitalization.

- -

- Moderate: required treatment modification (e.g., dose adjustment, combination with another drug) but no interruption of drug administration. A longer hospitalization or prescription of a specific treatment may be needed.

- -

- Severe: threatened the life of the patient and mandated an interruption of the drug administration and prescription of a specific treatment.

- -

- Lethal: directly or indirectly contributed to the death of a patient.

4.3. Sample Size

A sample size of approx. 250 individuals was estimated to be adequate to analyze the use of Cefto-M in routine clinical practices with a confidence interval of 95% and an error of 5%. The information was obtained from the electronic records of the different hospital pharmacy departments, gathering the number of patients to whom the drug was administered based on the type of infection. These data were introduced into an anonymized database in an SPSS format, following the national data protection legislation and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

In a descriptive analysis, the absolute and relative frequencies (%) were calculated for the qualitative variables. The means with standard deviation were calculated for the quantitative variables with a normal distribution and the medians were4 calculated with an interquartile range (IQR) for the variables with a non-normal distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test).

In the bivariate analyses of the mortality-related factors, the chi-squared test was used to compare the qualitative variables, the Student’s t-test was used for the quantitative variables a with normal distribution, and the Mann–Whitney U test for those with non-normal distribution. A multivariate logistic regression analysis considered the variables that were statistically significant in a bivariate analysis or deemed relevant (i.e., chronic kidney failure, active hematological or solid organ neoplasia, co-infection by SARS-CoV-2, rescue/first-line treatment).

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This study was approved by the ethics committee of the coordinating center and was exempted from the need to obtain informed consent due to its retrospective design and large size. All the data were gathered in accordance with Spanish personal data protection legislation.

5. Conclusions

Ceftobiprole-M is a safe antibiotic, comprising only half of the prescriptions for patients with respiratory infection, that is mainly administered as rescue therapy in pluripathological patients with severe infections. The infection-related mortality was 11.2%, which was largely associated with higher age, the presence of sepsis/septic shock, and ICU admission.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.H.-T.; methodology, C.H.-T.; software, I.P.-R., F.J.M.d.N., L.M., R.M., O.B.d.P., V.A.L.d.M., M.S.L., P.V., J.L.-T., A.A.G., L.M.N., M.M. and M.P.R.S.; formal analysis, C.H.-T. and I.P.-R.; validation, I.P-.R., F.J.M.d.N., L.M., R.M., O.B.d.P., V.A.L.d.M., M.S.L., P.V., J.L.-T., A.A.G., L.M.N., M.M. and M.P.R.S.; formal analysis, C.H.-T., I.P.-R. and D.A.G.; investigation, C.H.-T., I.P.-R. and D.A.G.; resources, I.P.-R. and D.A.G.; data curation, I.P.-R. and D.A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.H.-T.; writing—review and editing, I.P.-R. and S.S.-D.; visualization, F.J.M.d.N., L.M., R.M., O.B.d.P., V.A.L.d.M., M.S.L., P.V., J.L.-T., A.A.G., L.M.N., M.M. and M.P.R.S.; supervision, S.S.-D.; project administration, C.H.-T. and I.P.-R.; funding acquisition, C.H.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Project received partial funding from the laboratory ADVANZ PHARMA Switzerland, at 2 rue de Jargonnant, 5th floor, 1207 Geneva, Switzerland. FIB-CEF-2021-01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Granada (CEIM/CEI of Granada); code: 0095-N-22.

Informed Consent Statement

This study was exempt from the need to obtain patient consent due to its retrospective design and large size.

Data Availability Statement

The researchers confirm the accuracy and availability of the data used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Annual Surveillance Reports on Antimicrobial Resistance. EARS-Net. For 2019. Available online: https://antibiotic.ecdc.europa.eu/en (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Kollef, M.H. Inadequate antimicrobial treatment: An important determinant of outcome for hospitalized patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 31 (Suppl. 4), S131–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, D.J.; Parrillo, J.E.; Kumar, A. Sepsis and septic shock: A history. Crit. Care Clin. 2009, 25, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micek, S.T.; Hampton, N.; Kollef, M. Risk Factors and Outcomes for Ineffective Empiric Treatment of Sepsis Caused by Gram-Negative Pathogens: Stratification by Onset of Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 62, e01577-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.N.A.; Tambyah, P.A.; Lye, D.C.; Mo, Y.; Lee, T.H.; Yilmaz, M.; Alenazi, T.H.; Arabi, Y.; Falcone, M.; Bassetti, M.; et al. Effect of Piperacillin-Tazobactam vs Meropenem on 30-Day Mortality for Patients with E coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae Bloodstream Infection and Ceftriaxone Resistance: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 320, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo, J.L.; Patel, R. Ceftobiprole medocaril: A new generation beta-lactam. Drugs Today 2008, 44, 801–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbanat, D.; Shang, W.; Amsler, K.; Santoro, C.; Baum, E.; Crespo-Carbone, S.; Lynch, A.S. Evaluation of the in vitro activities of ceftobiprole and comparators in staphylococcal colony or microtitre plate biofilm assays. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 43, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noel, G.J.; Strauss, R.S.; Amsler, K.; Heep, M.; Pypstra, R.; Solomkin, J.S. Results of a double-blind, randomized trial of ceftobiprole treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections caused by gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.L.; Sox, H.; Willke, R.J.; Brixner, D.L.; Eichler, H.G.; Goettsch, W.; Madigan, D.; Makady, A.; Schneeweiss, S.; Tarricone, R.; et al. Good practices for real-world data studies of treatment and/or comparative effectiveness: Recommendations from the joint ISPOR-ISPESpecial Task Force on real-world evidence in health care decision making. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2017, 26, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhanel, G.G.; Kosar, J.; Baxter, M.; Dhami, R.; Borgia, S.; Irfan, N.; MacDonald, K.S.; Dow, G.; Lagacé-Wiens, P.; Dube, M.; et al. Real-life experience with ceftobiprole in Canada: Results from the CLEAR (CanadianLEadership onAntimicrobialReal-life usage) registry. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 24, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cortés, L.E.; Herrera-Hidalgo, L.; Almadana, V.; Gil-Navarro, M.V.; DOMUS OPAT Group. Ceftobiprole, a new option for multidrug resistant microorganisms in the outpatient antimicrobial therapy setting. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2022, 40, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Roberts, D.; Wood, K.E.; Light, B.; Parrillo, J.E.; Sharma, S.; Suppes, R.; Feinstein, D.; Zanotti, S.; Taiberg, L.; et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ellis, P.; Arabi, Y.; Roberts, D.; Light, B.; Parrillo, J.E.; Dodek, P.; Wood, G.; Kumar, A.; Simon, D.; et al. Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a fivefold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Antimicrobial Therapy of Septic Shock Database Research Group. Chest 2009, 136, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouzé, A.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Povoa, P.; Makris, D.; Artigas, A.; Bouchereau, M.; Lambiotte, F.; Metzelard, M.; Cuchet, P.; Geronimi, C.B.; et al. Relationship between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the incidence of ventilator-associated lower respiratory tract infections: A European multicenter cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. CIMA. Ministerio de Sanidad. Gobierno de España. Available online: https://cima.aemps.es/cima/publico/home.html (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Singh, K.V.; Murray, B.E. Efficacy of ceftobiprole Medocaril against Enterococcus faecalis in a murine urinary tract infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3457–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, M. Strategies for management of difficult to treat Gram-negative infections: Focus on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infez. Med. 2007, 15, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lan, S.H.; Lee, H.Z.; Lai, C.C.; Chang, S.P.; Lu, L.C.; Hung, S.H.; Lin, W.-T. Clinical efficacy and safety of ceftobiprole in the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, A.; Schmidt, S.; Rout, W.R.; Ben-David, K.; Burkhardt, O.; Derendorf, H. Soft-tissue penetration of ceftobiprole in healthy volunteers determined by in vivo microdialysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 2773–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.Y.; Calhoun, J.H.; Thomas, J.K.; Shapiro, S.; Schmitt-Hoffmann, A. Efficacies of ceftobiprole medocaril and comparators in a rabbit model of osteomyelitis due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 1618–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, I.; Buonomo, A.R.; Corcione, S.; Paradiso, L.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Bavaro, D.F.; Tiseo, G.; Sordella, F.; Bartoletti, M.; Palmiero, G.; et al. CEFTO-CURE study: CEFTObiprole Clinical Use in Real-lifE-a multi-centre experience in Italy. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2023, 62, 106817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S.C.; Welte, T.; File, T.M., Jr.; Strauss, R.S.; Michiels, B.; Kaul, P.; Balis, D.; Arbit, D.; Amsler, K.; Noel, G.J. A randomised, double-blind trial comparing ceftobiprole medocaril with ceftriaxone with or without linezolid for the treatment of patients with community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalisation. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2012, 39, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, S.S.; Rodriguez, A.H.; Chuang, Y.C.; Marjanek, Z.; Pareigis, A.J.; Reis, G.; Scheeren, T.W.L.; Sánchez, A.S.; Zhou, X.; Saulay, M.; et al. A phase 3 randomized double-blind comparison of ceftobiprole medocaril versus ceftazidime plus linezolid for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durante-Mangoni, E.; Andini, R.; Mazza, M.C.; Sangiovanni, F.; Bertolino, L.; Ursi, M.P.; Paradiso, L.; Karruli, A.; Esposito, C.; Murino, P.; et al. Real-life experience with ceftobiprole in a tertiary-care hospital. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.H.; Marson, E.J.; Elhadi, M.; Macleod, K.D.M.; Yu, Y.C.; Davids, R.; Boden, R.; Overmeyer, R.C.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Thomson, D.A.; et al. Factors associated with mortality in patients with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia 2021, 76, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 13.0, 2023. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Charlson, M.E.; Charlson, R.E.; Paterson, J.C.; Marinopoulos, S.S.; Briggs, W.M.; Hollenberg, J.P. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecconi, M.; Evans, L.; Levy, M.; Rhodes, A. Sepsis and septic shock. Lancet 2018, 392, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.A.; Musher, D.M.; Evans, S.E.; Dela Cruz, C.; Crothers, K.A.; Hage, C.A.; Aliberti, S.; Anzueto, A.; Arancibia, F.; Arnold, F.; et al. Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Immunocompromised Adults: A Consensus Statement Regarding Initial Strategies. Chest 2020, 158, 1896–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel Cisneros-Herreros, J.; Cobo-Reinoso, J.; Pujol-Rojo, M.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Salavert-Lletí, M. Guía para el diagnóstico y tratamiento del paciente con bacteriemia. Guías de la Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC). Enfermedades Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2007, 25, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).