Cefto Real-Life Study: Real-World Data on the Use of Ceftobiprole in a Multicenter Spanish Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Cohort Description

2.2. Microbiological Isolation

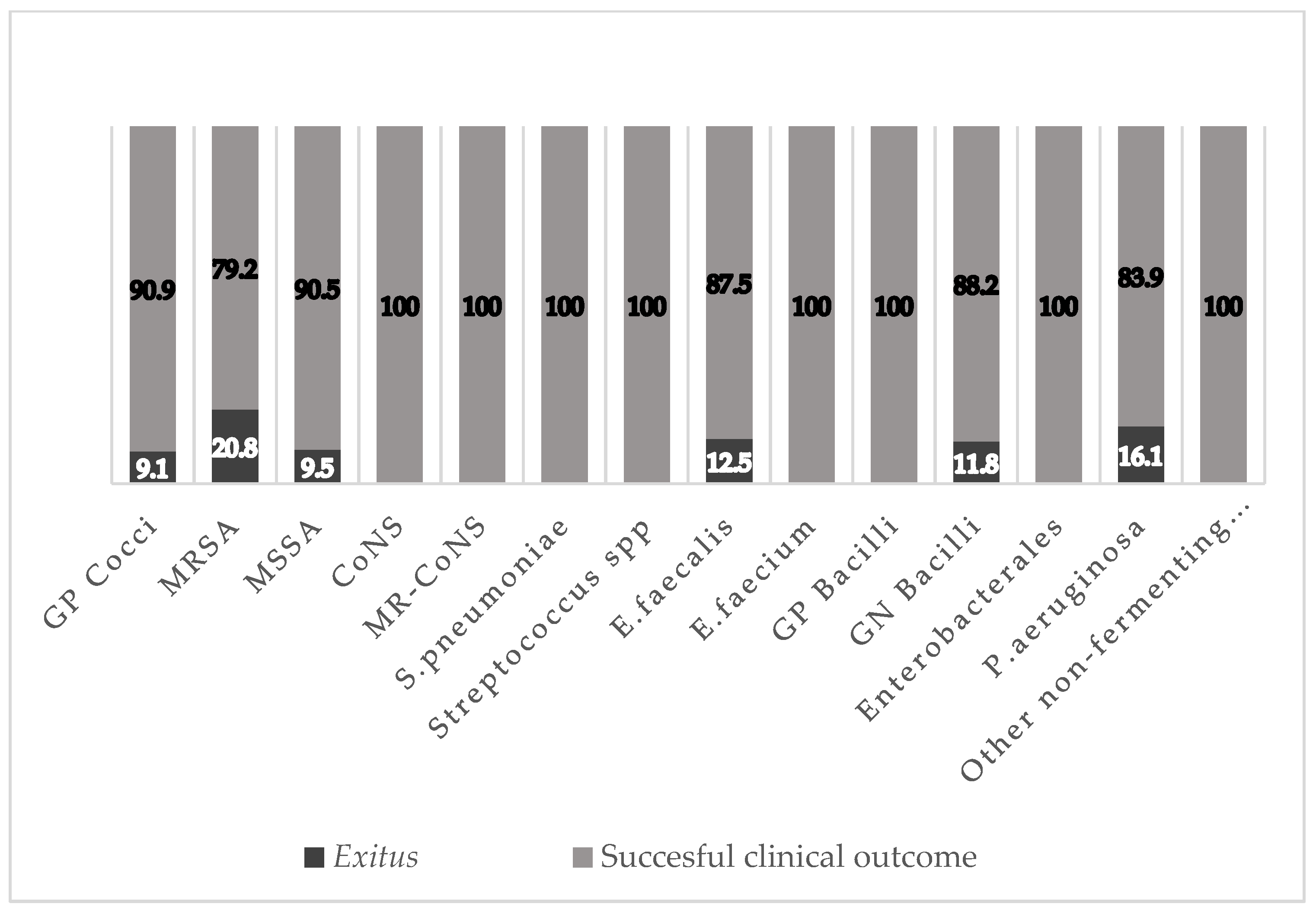

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Adverse Effects

2.5. Bi- and Multivariate Analyses of Mortality-Related Factors

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Variables and Definitions

- -

- Nosocomial infection: onset > 72 h after hospitalization.

- -

- Nosohusial/nosocomial infection: healthcare-related (day hospital, residence, day center for elderly).

- -

- The age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index was used to estimate the 10-year life expectancy of the patients as a function of their age and the presence of comorbidities at admission for the infectious episode [27].

- -

- Sepsis/septic shock: refractory hypotension and end-organ perfusion dysfunction despite adequate fluid resuscitation [28].

- -

- Immunodepression: congenital or acquired immunodeficiency or receipt of immunosuppressive treatment [29].

- -

- Relapse/recurrence of the infection was defined by a second episode within three months [30].

- -

- The adverse effect classification used in this study is as follows.

- -

- Mild: required no antidote or treatment; brief hospitalization.

- -

- Moderate: required treatment modification (e.g., dose adjustment, combination with another drug) but no interruption of drug administration. A longer hospitalization or prescription of a specific treatment may be needed.

- -

- Severe: threatened the life of the patient and mandated an interruption of the drug administration and prescription of a specific treatment.

- -

- Lethal: directly or indirectly contributed to the death of a patient.

4.3. Sample Size

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Annual Surveillance Reports on Antimicrobial Resistance. EARS-Net. For 2019. Available online: https://antibiotic.ecdc.europa.eu/en (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Kollef, M.H. Inadequate antimicrobial treatment: An important determinant of outcome for hospitalized patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 31 (Suppl. 4), S131–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, D.J.; Parrillo, J.E.; Kumar, A. Sepsis and septic shock: A history. Crit. Care Clin. 2009, 25, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micek, S.T.; Hampton, N.; Kollef, M. Risk Factors and Outcomes for Ineffective Empiric Treatment of Sepsis Caused by Gram-Negative Pathogens: Stratification by Onset of Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 62, e01577-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.N.A.; Tambyah, P.A.; Lye, D.C.; Mo, Y.; Lee, T.H.; Yilmaz, M.; Alenazi, T.H.; Arabi, Y.; Falcone, M.; Bassetti, M.; et al. Effect of Piperacillin-Tazobactam vs Meropenem on 30-Day Mortality for Patients with E coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae Bloodstream Infection and Ceftriaxone Resistance: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 320, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo, J.L.; Patel, R. Ceftobiprole medocaril: A new generation beta-lactam. Drugs Today 2008, 44, 801–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbanat, D.; Shang, W.; Amsler, K.; Santoro, C.; Baum, E.; Crespo-Carbone, S.; Lynch, A.S. Evaluation of the in vitro activities of ceftobiprole and comparators in staphylococcal colony or microtitre plate biofilm assays. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 43, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noel, G.J.; Strauss, R.S.; Amsler, K.; Heep, M.; Pypstra, R.; Solomkin, J.S. Results of a double-blind, randomized trial of ceftobiprole treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections caused by gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.L.; Sox, H.; Willke, R.J.; Brixner, D.L.; Eichler, H.G.; Goettsch, W.; Madigan, D.; Makady, A.; Schneeweiss, S.; Tarricone, R.; et al. Good practices for real-world data studies of treatment and/or comparative effectiveness: Recommendations from the joint ISPOR-ISPESpecial Task Force on real-world evidence in health care decision making. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2017, 26, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhanel, G.G.; Kosar, J.; Baxter, M.; Dhami, R.; Borgia, S.; Irfan, N.; MacDonald, K.S.; Dow, G.; Lagacé-Wiens, P.; Dube, M.; et al. Real-life experience with ceftobiprole in Canada: Results from the CLEAR (CanadianLEadership onAntimicrobialReal-life usage) registry. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 24, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cortés, L.E.; Herrera-Hidalgo, L.; Almadana, V.; Gil-Navarro, M.V.; DOMUS OPAT Group. Ceftobiprole, a new option for multidrug resistant microorganisms in the outpatient antimicrobial therapy setting. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2022, 40, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Roberts, D.; Wood, K.E.; Light, B.; Parrillo, J.E.; Sharma, S.; Suppes, R.; Feinstein, D.; Zanotti, S.; Taiberg, L.; et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ellis, P.; Arabi, Y.; Roberts, D.; Light, B.; Parrillo, J.E.; Dodek, P.; Wood, G.; Kumar, A.; Simon, D.; et al. Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a fivefold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Antimicrobial Therapy of Septic Shock Database Research Group. Chest 2009, 136, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouzé, A.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Povoa, P.; Makris, D.; Artigas, A.; Bouchereau, M.; Lambiotte, F.; Metzelard, M.; Cuchet, P.; Geronimi, C.B.; et al. Relationship between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the incidence of ventilator-associated lower respiratory tract infections: A European multicenter cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. CIMA. Ministerio de Sanidad. Gobierno de España. Available online: https://cima.aemps.es/cima/publico/home.html (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Singh, K.V.; Murray, B.E. Efficacy of ceftobiprole Medocaril against Enterococcus faecalis in a murine urinary tract infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3457–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, M. Strategies for management of difficult to treat Gram-negative infections: Focus on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infez. Med. 2007, 15, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lan, S.H.; Lee, H.Z.; Lai, C.C.; Chang, S.P.; Lu, L.C.; Hung, S.H.; Lin, W.-T. Clinical efficacy and safety of ceftobiprole in the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, A.; Schmidt, S.; Rout, W.R.; Ben-David, K.; Burkhardt, O.; Derendorf, H. Soft-tissue penetration of ceftobiprole in healthy volunteers determined by in vivo microdialysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 2773–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.Y.; Calhoun, J.H.; Thomas, J.K.; Shapiro, S.; Schmitt-Hoffmann, A. Efficacies of ceftobiprole medocaril and comparators in a rabbit model of osteomyelitis due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 1618–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, I.; Buonomo, A.R.; Corcione, S.; Paradiso, L.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Bavaro, D.F.; Tiseo, G.; Sordella, F.; Bartoletti, M.; Palmiero, G.; et al. CEFTO-CURE study: CEFTObiprole Clinical Use in Real-lifE-a multi-centre experience in Italy. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2023, 62, 106817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S.C.; Welte, T.; File, T.M., Jr.; Strauss, R.S.; Michiels, B.; Kaul, P.; Balis, D.; Arbit, D.; Amsler, K.; Noel, G.J. A randomised, double-blind trial comparing ceftobiprole medocaril with ceftriaxone with or without linezolid for the treatment of patients with community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalisation. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2012, 39, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, S.S.; Rodriguez, A.H.; Chuang, Y.C.; Marjanek, Z.; Pareigis, A.J.; Reis, G.; Scheeren, T.W.L.; Sánchez, A.S.; Zhou, X.; Saulay, M.; et al. A phase 3 randomized double-blind comparison of ceftobiprole medocaril versus ceftazidime plus linezolid for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durante-Mangoni, E.; Andini, R.; Mazza, M.C.; Sangiovanni, F.; Bertolino, L.; Ursi, M.P.; Paradiso, L.; Karruli, A.; Esposito, C.; Murino, P.; et al. Real-life experience with ceftobiprole in a tertiary-care hospital. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.H.; Marson, E.J.; Elhadi, M.; Macleod, K.D.M.; Yu, Y.C.; Davids, R.; Boden, R.; Overmeyer, R.C.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Thomson, D.A.; et al. Factors associated with mortality in patients with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia 2021, 76, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 13.0, 2023. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Charlson, M.E.; Charlson, R.E.; Paterson, J.C.; Marinopoulos, S.S.; Briggs, W.M.; Hollenberg, J.P. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecconi, M.; Evans, L.; Levy, M.; Rhodes, A. Sepsis and septic shock. Lancet 2018, 392, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.A.; Musher, D.M.; Evans, S.E.; Dela Cruz, C.; Crothers, K.A.; Hage, C.A.; Aliberti, S.; Anzueto, A.; Arancibia, F.; Arnold, F.; et al. Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Immunocompromised Adults: A Consensus Statement Regarding Initial Strategies. Chest 2020, 158, 1896–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel Cisneros-Herreros, J.; Cobo-Reinoso, J.; Pujol-Rojo, M.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Salavert-Lletí, M. Guía para el diagnóstico y tratamiento del paciente con bacteriemia. Guías de la Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC). Enfermedades Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2007, 25, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cohort N = 249 | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (years), (±SD) | 66.6 (±15.4) |

| Charlson index, median (IQR) | 4 (2–6) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 148 (59.4) |

| Female | 101 (40.6) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 231 (92.8) |

| Latin | 17 (6.8) |

| African | 1 (0.4) |

| Acquisition of the infection, n (%) | |

| Community-acquired infection | 107 (43) |

| Nosocomial/Nosohusial infection | 142 (57) |

| Presence of sepsis or septic shock, n (%) | |

| Sepsis | 66 (26.5) |

| Septic shock | 11 (4.4) |

| Inpatient departments, n (%) | 238 (95.6) |

| Medical department | 188 (75.5) |

| Intensive care unit | 12 (4.8) |

| Surgical department | 38 (15.2) |

| Outpatient antibiotic treatment, n (%) | 11 (4.4) |

| Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), n (%) | 34 (13.7) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | 123 (49.4) |

| Hypertension | 73 (29.3) |

| Dyslipidemia | 11 (4.4) |

| Obesity | 1 (0.4) |

| ≥2 Risk factors | 38 (15.2) |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 78 (31.3) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 26 (33.3) |

| Heart failure | 9 (11.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 15 (19.2) |

| Pacemaker carrier | 1 (1.3) |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 1 (1.3) |

| Other conditions | 9 (11.5) |

| ≥2 Conditions | 17 (21.8) |

| Respiratory diseases, n (%) | 74 (29.7) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 29 (39.2) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) | 9 (12.2) |

| Thromboembolic pulmonary vascular disease (TPVD) | 4 (5.4) |

| Bronchiectasis | 8 (10.8) |

| Asthma | 4 (5.4) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 3 (4.1) |

| Other conditions | 6 (8.1) |

| ≥2 Conditions | 11 (14.9) |

| Gastrointestinal and hepatic diseases, n (%) | 45 (18.1) |

| Chronic liver disease | 18 (40) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 8 (17.8) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 6 (13.3) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 3 (6.7) |

| Liver transplantation | 3 (6.7) |

| Other conditions | 7 (15.6) |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 35 (14.1) |

| Active solid malignancy, n (%) | 20 (8) |

| Active hematologic malignancy, n (%) | 33 (13.3) |

| Metabolic disorders, n (%) | 83 (33.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 70 (84.3) |

| Hypothyroidism | 11 (13.3) |

| Adrenal insufficiency | 2 (2.4) |

| Neurological diseases, n (%) | 21 (8.4) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 14 (5.6) |

| Psychiatric conditions, n (%) | 9 (3.6) |

| Immunocompromised patients, n (%) | 52 (20.9) |

| Immunosuppressant drugs therapy, n (%) | 43 (17.3) |

| Infection pathway | |

| Bloodstream infection, n (%) | 44 (17.7) |

| Primary bacteremia | 37 (14.9) |

| Catheter-associated bloodstream infection | 7 (2.8) |

| Infective endocarditis, n (%) | 3 (1.2) |

| Respiratory tract infections, n (%) | 139 (55.8) |

| Nosocomial pneumonia | 62 (24.9) |

| Community-acquired pneumonia | 60 (24.1) |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 5 (2) |

| Soft tissue and skin infection, n (%) | 54 (21.7) |

| Diabetic foot infection | 20 (37) |

| Cellulitis | 10 (18.5) |

| Soft tissue abscess | 7 (13) |

| Infected pressure ulcer | 7 (13) |

| Surgical wound infection | 6 (11.1) |

| Myositis | 2 (3.7) |

| Other type | 2 (3.7) |

| Urinary tract infection, n (%) | 10 (4) |

| Complicated UTI (pyelonephritis) | 5 (50) |

| Non-complicated UTI | 3 (30) |

| Renal abscess | 2 (20) |

| Central nervous system infection, n (%) | 8 (3.2) |

| Ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection | 3 (37.5) |

| Epidural abscess | 2 (25) |

| Cerebral abscess | 2 (25) |

| Meningitis | 1 (12.5) |

| Intra-abdominal infection, n (%) | 9 (3.6) |

| Bone and joint infection, n (%) | 14 (5.6) |

| Prosthetic joint Infection | 6 (42.9) |

| Osteomyelitis | 4 (28.6) |

| Infectious tenosynovitis | 3 (21.4) |

| Septic arthritis | 1 (7.1) |

| Spondylodiscitis, n (%) | 3 (1.2) |

| Other type of infection, n (%) | 4 (1.6) |

| Cohort N = 249 | |

|---|---|

| General microbial profile, n (%) | |

| No isolation | 111 (45) |

| Positive microbial samples | 137 (55) |

| Microbial profile of isolates, n (%) | |

| Monomicrobial infection | 81 (59.2) |

| Polymicrobial infection | 56 (40.8) |

| Gram-positive cocci, n (%) | 87 (63.5) |

| Staphylococus aureus | 46 (52.9) |

| MRSA | 24 (52.2) |

| MSSA | 21 (45.6) |

| Non-categorized Staphylococcus aureus | 1 (2.2) |

| CoNS | 20 (22.9) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 15 (75) |

| Staphylococcus hemolyticus | 2 (10) |

| Staphylococcus hominis | 2 (10) |

| Staphylococcus schleiferi | 1 (5) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 9 (10.3) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 8 (88.9) |

| Enterococcus faecium | 1 (11.1) |

| Streptococcus spp. | 10 (11.5) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 5 (50) |

| Streptococcus anginosus | 4 (40) |

| Streptococcus peroris | 1 (10) |

| Other cocci | 2 (2.3) |

| Rhottia spp. | 2 (100) |

| Gram-positive bacilli, n (%) | 1 (0.7) |

| Cutibacterium acnes | 1 (100) |

| Gram-negative bacilli, n (%) | 49 (35.8) |

| Enterobacterales | 13 (26.5) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 5 (38.5) |

| Escherichia coli | 4 (30.8) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 1 (7.7) |

| Proteus mirabilis | 1 (7.7) |

| Proteus vulgaris | 1 (7.7) |

| Non-fermenting gram-negative bacilli | 31 (63.2) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 31 (100) |

| Other gram-negative bacilli | 5 (10.2) |

| Morganella spp. | 2 (40) |

| Hemophilus influenzae | 2 (40) |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 1 (20) |

| Microorganisms, n (%) | Vanco-S | Cloxa-S | Dapto-S | Ceftobi-S | Cefe-S | Mero-S | Pip/Taz-S | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 46 (18.4) | 35 (97.2) | 14 (41.2) | 21 (67.7) | 6 (100) | |||

| MRSA | 24 (9.6) | 21 (100) | 0 (0) | 16 (80) | 3 (100) | |||

| MSSA | 21 (8.4) | 14 (93.3) | 14 (100) | 5 (45.5) | 3 (100) | |||

| Enterococcus spp. | 10 (4) | 5 (100) | NT | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | |||

| Streptococcus spp. | 10 (4) | 3 (100) | NT | NT | 1 (100) | |||

| GNB | 49 (20.5) | 10 (100) | 4 (33.3) | 5 (83.3) | 16 (84.2) | |||

| Enterobacteriaceae | 13 (5.2) | 5 (100) | 1 (50) | NT | 6 (100) | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 31 (12.4) | 4 (100) | 2 (40) | 5 (83.3) | 7 (70) | |||

| Hemophilus influenzae | 2 (0.4) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | NT | NT |

| N = 249 | |

|---|---|

| Total dose of ceftobiprole, median (IQR) | 10.5 (7.5–15) |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy, median (IQR) | 7 (5–10) |

| Treatment regimen, n (%) | |

| Ceftobiprole monotherapy | 134 (53.8) |

| Antibiotic combination | 115 (46.2) |

| Ceftobiprole + Daptomycin | 27 (23.5) |

| Ceftobiprole + Vancomycin | 4 (3.5) |

| Ceftobiprole + Linezolid | 8 (7) |

| Ceftobiprole + Dalbavancin | 1 (0.9) |

| Ceftobiprole + Clindamycin | 2 (1.7) |

| Ceftobiprole + Tigecycline | 4 (3.5) |

| Ceftobiprole + Cloxacillin | 3 (2.6) |

| Ceftobiprole + Ceftazidime | 1 (0.9) |

| Ceftobiprole + Ceftaroline | 2 (1.7) |

| Ceftobiprole + Ceftriaxone | 2 (1.7) |

| Ceftobiprole + Ceftazidime/Avibactam | 2 (1.7) |

| Ceftobiprole + Meropenem | 9 (7.8) |

| Ceftobiprole + Levofloxacin | 10 (8.7) |

| Ceftobiprole + Ciprofloxacin | 4 (3.5) |

| Ceftobiprole + Piperacillin/Tazobactam | 2 (1.7) |

| Ceftobiprole + Amikacin | 6 (5.2) |

| Ceftobiprole + Azithromycin | 10 (8.7) |

| Ceftobiprole + Metronidazole | 13 (11.3) |

| Ceftobiprole + Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole | 7 (6.1) |

| Ceftobiprole + Doxycycline | 2 (1.7) |

| Ceftobiprole + Fosfomycin | 1 (0.9) |

| Ceftobiprole + Antifungal agents | 6 (5.2) |

| Ceftobiprole + Antiviral agents | 2 (1.7) |

| Length of hospital stay, median (IQR) | 20 (13–32) |

| Ceftobiprole as empirical treatment, n (%) | 169 (67.9) |

| Appropriate empirical treatment, n (%) | 140 (82.8) |

| Prescription of Ceftobiprole, n (%) | |

| As first-line treatment | 74 (29.7) |

| As second-line or more | 175 (70.3) |

| Reason for switching to Ceftobiprole, n (%) | |

| Failure of previous antibiotic treatment | 84 (48) |

| Toxicity/adverse effects of previous antibiotic treatment | 3 (1.7) |

| Guided by microbiological results | 65 (37.1) |

| Other reasons (or combination of previous) | 23 (13.1) |

| Recurrence and readmission, n (%) | |

| Recurrence of infection (in the first month) | 3 (1.2) |

| Hospital readmission | 15 (6) |

| Mortality, n (%) | |

| Total mortality | 54 (21.7) |

| Non-related-to-infection mortality | 26 (10.4) |

| Related-to-infection mortality | 28 (11.2) |

| 14-day mortality | 17 (60.7) |

| 28-day mortality | 9 (32.1) |

| 6-month mortality | 2 (7.1) |

| N = 249 | |

|---|---|

| Total adverse effects, n (%) | 9 (3.6) |

| Severity of adverse effects, n (%) | |

| Mild | 4 (1.6) |

| Moderate | 4 (1.6) |

| Severe | 1 (0.4) |

| Adverse effects by symptoms, n (%) | |

| Elevated liver enzymes | 3 (1.2) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 2 (0.8) |

| Urticaria-like cutaneous rash | 1 (0.4) |

| Non-Survivor N = 31 | Survivor N = 219 | Bivariate p * | Multivariate HR, 95% IC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (±DS) | 76.7 (±13.3) | 65.3 (±15.2) | 0.0001 | 1.1 (1.04–1.16) |

| Charlson index, mean (IQR) | 4.5 (4–6.75) | 4 (2–6) | 0.253 | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Men | 20 (71.4) | 128 (57.9) | 0.17 | |

| Women | 8 (28.6) | 93 (44.1) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Caucasian | 27 (96.4) | 204 (92.3) | ||

| Latin | 1 (3.6) | 16 (7.2) | 0.718 | |

| African | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Inpatient department, n (%) | 26 (83.9) | 212 (95.9) | 0.9 | |

| Medical services | 24 (92.3) | 167 (78.8) | ||

| Infectious diseases | 2 (7.1) | 55 (24.9) | 0.035 | 0.19 (0.03–1.2) |

| Internal medicine | 9 (32.1) | 43 (19.5) | 0.12 | |

| Pneumology | 2 (7.1) | 37 (16.7) | 0.27 | |

| Intensive care unit | 8 (28.6) | 4 (1.8) | 0.001 | 42.02 (4.49–393.4) |

| Hematology | 1 (3.6) | 10 (4.5) | 0.25 | |

| Oncology | 2 (7.1) | 14 (6.3) | 0.27 | |

| Surgical services | 2 (7.1) | 36 (16.3) | 0.27 | |

| OPAT, n (%) | 2 (7.1) | 9 (4.1) | 0.36 | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Cardiovascular risk factors | 22 (78.6) | 101 (45.7) | 0.001 | 1.67 (0.49–5.62) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 6 (21.4) | 72 (32.6) | 0.231 | |

| Pulmonary disease | 10 (35.7) | 64 (29) | 0.461 | |

| Gastrointestinal and hepatic disease | 5 (17.9) | 40 (18.1) | 0.975 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (14.3) | 31 (14) | 0.97 | 0.94 (0.21–4.33) |

| Active solid malignancy | 3 (10.7) | 17 (7.7) | 0.526 | 1.81 (0.289–11.41) |

| Hematological malignancy | 4 (14.3) | 29 (13.1) | 0.864 | 1.21 (0.24–6.16) |

| Metabolic disorders | 11 (39.3) | 72 (32.6) | 0.478 | |

| Neurological diseases | 6 (21.4) | 15 (6.8) | 0.019 | 2.59 (0.69–9.85) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 0 (0) | 9 (4.1) | 0.6 | |

| Stroke | 3 (10.7) | 11 (5) | 0.199 | |

| Immunosuppression | 10 (35.7) | 42 (19) | 0.04 | 2.03 (0.52–7.88) |

| COVID-19 superinfection, n (%) | 7 (25) | 27 (12.2) | 0.063 | 2.08 (0.43–10.12) |

| Number of pathway infection, mean (IQR) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 0.945 | |

| Pathway infection, n (%) | ||||

| Bloodstream infection | 5 (17.9) | 39 (17.6) | 0.978 | |

| Infective endocarditis | 1 (3.6) | 2 (0.9) | 0.223 | |

| Communitary-acquired pneumonia | 10 (35.7) | 50 (22.6) | 0.127 | |

| Nosocomial pneumonia | 9 (32.1) | 53 (24) | 0.347 | |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 2 (7.1) | 3 (1.4) | 0.04 | 0.12 (0.004–3.89) |

| Skin and soft tissue infection | 3 (10.7) | 51 (23.1) | 0.135 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 (0) | 10 (4.5) | 0.251 | |

| Central nervous system infection | 0 (0) | 8 (3.6) | 0.306 | |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 1 (3.6) | 8 (3.6) | 0.99 | |

| Bone and joint infection | 1 (3.6) | 13 (5.9) | 0.617 | |

| Spondylodiscitis | 0 (0) | 3 (1.4) | 0.535 | |

| Other type of infection | 0 (0) | 4 (1.8) | 0.473 | |

| Sepsis or shock | 16 (57.1) | 61 (27.6) | 0.0001 | 2.94 (1.01–8.54) |

| Microbiology and acquisition of the infection, n (%) | ||||

| Microbial isolation | 0.758 | |||

| Monomicrobial infection | 9 (32.1) | 84 (38) | ||

| Polymicrobial infection | 6 (21.4) | 50 (22.6) | ||

| Place of acquisition of the infection | 0.762 | |||

| Communitary-acquired infection | 12 (42.9) | 95 (43) | ||

| Nosocomial infection | 10 (35.7) | 90 (40.7) | ||

| Nosohusial infection | 6 (21.4) | 36 (16.4) | ||

| GPC | 8 (28.6) | 80 (36.2) | 0.426 | |

| MRSA | 5 (17.9) | 19 (8.6) | 0.118 | |

| MSSA | 2 (7.1) | 19 (8.6) | 0.794 | |

| CoNS | 0 (0) | 20 (9) | 0.097 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 1 (3.6) | 7 (3.2) | 0.909 | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 0 (0) | 5 (2.3) | 0.421 | |

| GNB | 6 (21.4) | 45 (20.4) | 0.895 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 5 (17.9) | 26 (11.8) | 0.358 | |

| Antimicrobial therapy | ||||

| Total dose of ceftobiprole (mg), mean (IQR) | 9 (4.5–12.75) | 10.5 (7.5–15) | 0.049 | 0.91 (0.73–1.12) |

| Length of ceftobiprole therapy (days), mean (IQR) | 6 (3–8.5) | 7 (5–10) | 0.029 | 1.08 (0.82–1.4) |

| Therapy regimen: | ||||

| Ceftobiprole monotherapy, n (%) | 16 (57.1) | 118 (53.4) | 0.708 | |

| Antibiotic combination, n (%) | 12 (42.9) | 103 (46.6) | ||

| Prescription of ceftobiprole: | ||||

| First-line, n (%) | 6 (21.4) | 68 (30.8) | 0.308 | 1.34 (0.4–4.49) |

| Rescue therapy, n (%) | 22 (78.6) | 153 (69.2) | ||

| Empirical treatment, n (%) | 22 (78.6) | 146 (66.1) | 0.183 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hidalgo-Tenorio, C.; Pitto-Robles, I.; Arnés García, D.; de Novales, F.J.M.; Morata, L.; Mendez, R.; de Pablo, O.B.; López de Medrano, V.A.; Lleti, M.S.; Vizcarra, P.; et al. Cefto Real-Life Study: Real-World Data on the Use of Ceftobiprole in a Multicenter Spanish Cohort. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12071218

Hidalgo-Tenorio C, Pitto-Robles I, Arnés García D, de Novales FJM, Morata L, Mendez R, de Pablo OB, López de Medrano VA, Lleti MS, Vizcarra P, et al. Cefto Real-Life Study: Real-World Data on the Use of Ceftobiprole in a Multicenter Spanish Cohort. Antibiotics. 2023; 12(7):1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12071218

Chicago/Turabian StyleHidalgo-Tenorio, Carmen, Inés Pitto-Robles, Daniel Arnés García, F. Javier Membrillo de Novales, Laura Morata, Raul Mendez, Olga Bravo de Pablo, Vicente Abril López de Medrano, Miguel Salavert Lleti, Pilar Vizcarra, and et al. 2023. "Cefto Real-Life Study: Real-World Data on the Use of Ceftobiprole in a Multicenter Spanish Cohort" Antibiotics 12, no. 7: 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12071218

APA StyleHidalgo-Tenorio, C., Pitto-Robles, I., Arnés García, D., de Novales, F. J. M., Morata, L., Mendez, R., de Pablo, O. B., López de Medrano, V. A., Lleti, M. S., Vizcarra, P., Lora-Tamayo, J., Arnáiz García, A., Núñez, L. M., Masiá, M., Seco, M. P. R., & Sadyrbaeva-Dolgova, S. (2023). Cefto Real-Life Study: Real-World Data on the Use of Ceftobiprole in a Multicenter Spanish Cohort. Antibiotics, 12(7), 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12071218