Abstract

Electrospun nanofibers possess a large surface area and a three-dimensional porous network that makes them a perfect material for embedding functional nanoparticles for diverse applications. Herein, we report the trends in embedding upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) in polymeric nanofibers for making an advanced miniaturized (bio)analytical device. UCNPs have the benefits of several optical properties, like near-infrared excitation, anti-Stokes emission over a wide range from UV to NIR, narrow emission bands, an extended lifespan, and photostability. The luminescence of UCNPs can be regulated using different lanthanide elements and can be used for sensing and tracking physical processes in biological systems. We foresee that a UCNP-based nanofiber sensing platform will open opportunities in developing cost-effective, miniaturized, portable and user-friendly point-of-care sensing device for monitoring (bio)analytical processes. Major challenges in developing microfluidic (bio)analytical systems based on UCNPs@nanofibers have been reviewed and presented.

1. Introduction

Lab-on-a-chip, frequently referred to as micro-fabricated, (bio)analytical devices provide an efficient interface for multiple physiologically significant chemical evaluations. The creation and application of microfluidic-based (bio)analytical techniques encompasses a variety from both established ideas and innovations such as micromachining, microlithography, the field of nanotechnology, and micro-electromechanical systems [1]. Mechanism-based (bio)analytical methods (MBBTs) can reveal the presence of individual molecules and compounds that are toxic and harmful. The gene induction assays, enzyme inhibition assays, receptor assays, and immunoassays are included in MBBTs. The initial interaction of a chemical species with a biological target and their subsequent transformation into a specific signal forms the basis of (bio)analytical techniques. For instance, the chemical binding of a ligand to a biological receptor may be the first step in the chemical–biological interaction. It would then be feasible to quantify the actual ligand–receptor association by determining the gene that encodes luciferase expression in a cell sensor gene bioassay. The (bio)analytical techniques are also preferred over conventional equipment like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) because of the requirement for smaller sample volumes, quicker response time, and economical benefits.

Microfluidics is an emerging technology that has been regarded as crucial in various fields, from material science to biomedical engineering. Bioluminescence-based optical biosensors are used to analyze variations in the bioluminescence pattern of a luminous bacteria-incubated sample in comparison to a control sample [2,3]. By absorbing low-energy photons in the near-infrared (NIR) range, lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) can exhibit high-energy photon emission in the visible spectrum. The UCNPs’ high-energy luminescent emission has lengthy decay times, a minimum background signal, and remarkably crisp optical characteristics. The energy associated with these excited states further splits under the crystal field once it is entwined in massive crystals and nanostructures, establishing an array of modes with several distant energies. On the anatomical scale, the physical mechanisms causing upconversion in nanoparticles are the same as those in bulk crystals; however, there are special concerns in the realm of nanoparticles regarding their overall efficiency and other ensemble effects. The 4f-4f or 4f-5d transitions underlie the lanthanides’ (Ln3+) distinctive emission [4], which on excitation produces strong emissions in the NIR, visible, and UV regions, thus acting as optically active centers. Lanthanide-doped UCNPs can be regarded as host–guest systems where Ln3+ are guest molecules that occupy the host lattice. Host materials like NaYF4, NaGdF4, CaF2, etc., [5,6,7,8] are generally used to hold the lanthanides (sensitizer and activator ions) within a proper distance to generate intense NIR-to-visible upconversion (UC) fluorescence. When doped with sensitizers (Yb3+) and activators (Er3+, Tm3+, Ho3+), the host can emit strong green and red light. Although the photon upconversion mechanism in lanthanide-doped nanoparticles is generally the same as in bulk material, it has been demonstrated that certain factors linked to the surface and size of the UCNPs have significant implications [9]. Since the 4f electrons are suitably localized, quantum confinement is not predicted to affect the energy levels in lanthanide ions; nonetheless, other phenomena have been demonstrated to have significant influence on the emission spectra and efficiency of UCNPs. The conflict between radiative and non-radiative relaxation makes the phonon density of states a crucial consideration. Furthermore, phonon-assisted processes play a crucial role in bringing the f orbitals’ energy states into range for energy transfer to take place. Although low-frequency vibrations are not found in the spectrum in nanocrystals/nanomaterials, the phonon band diminishes to a distinct collection of states. The repercussions of dimensionality are convoluted because of the competition between non-radiative relaxation, which shortens the durations of excited states, and phonon-assistance, which enhances the energy transfer. The color and efficiency of luminescence are also influenced by surface-related factors. Large vibrational energy levels of surface ligands on nanocrystals can greatly enhance phonon-assisted actions [10].

Therefore, research has been attracted to their applications in bioimaging-guided disease monitoring, photodynamic therapy (PDT), (bio)analytical sensing, photovoltaics, and so on [11,12,13]. Obtaining quick, consistent, and reliable analytical signals is a crucial component of a sensing platform that qualifies for bioassay in bio(analytical) sensing. Most fluorescent dyes have modest luminous life spans, light bleaching, auto-fluorescence in living tissues, as well as moderate Stokes shifts, which limit their potential in biosensing and biochemical tests. However, UCNPs can circumvent these limitations due to their unique capacity to absorb NIR light and display compact emission bands at an inferior wavelength. This can lessen light dispersion, enable deep tissue penetration without inducing autofluorescence, and can have an extended luminescence lifespan. When developing assays, UCNPs’ ruggedness and broad chemical range provide a variety of choices, including the recognition of ions in the inside region of the cells and analytes as well as biomarkers [14]. Upconversion nanoparticles based on a crystalline host lattice (in most cases hexagonal NaYF4) and doped with different combinations of lanthanide ions diverge from other nanoscale luminescent probes mainly in using infrared excitation waves, as they frequently cause biological tissues and polymeric materials to become transparent in the infrared spectrum, low auto-fluorescence, and high signal-to-noise ratios. The numerous long-lived electronic states of lanthanide ions are sequentially absorbed by several photons, converting the NIR light into visible and UV light into a nonlinear process. This method permits lower excitation intensity because it increases the likelihood of attaining higher excited states than two-photon excitation of dyes [15].

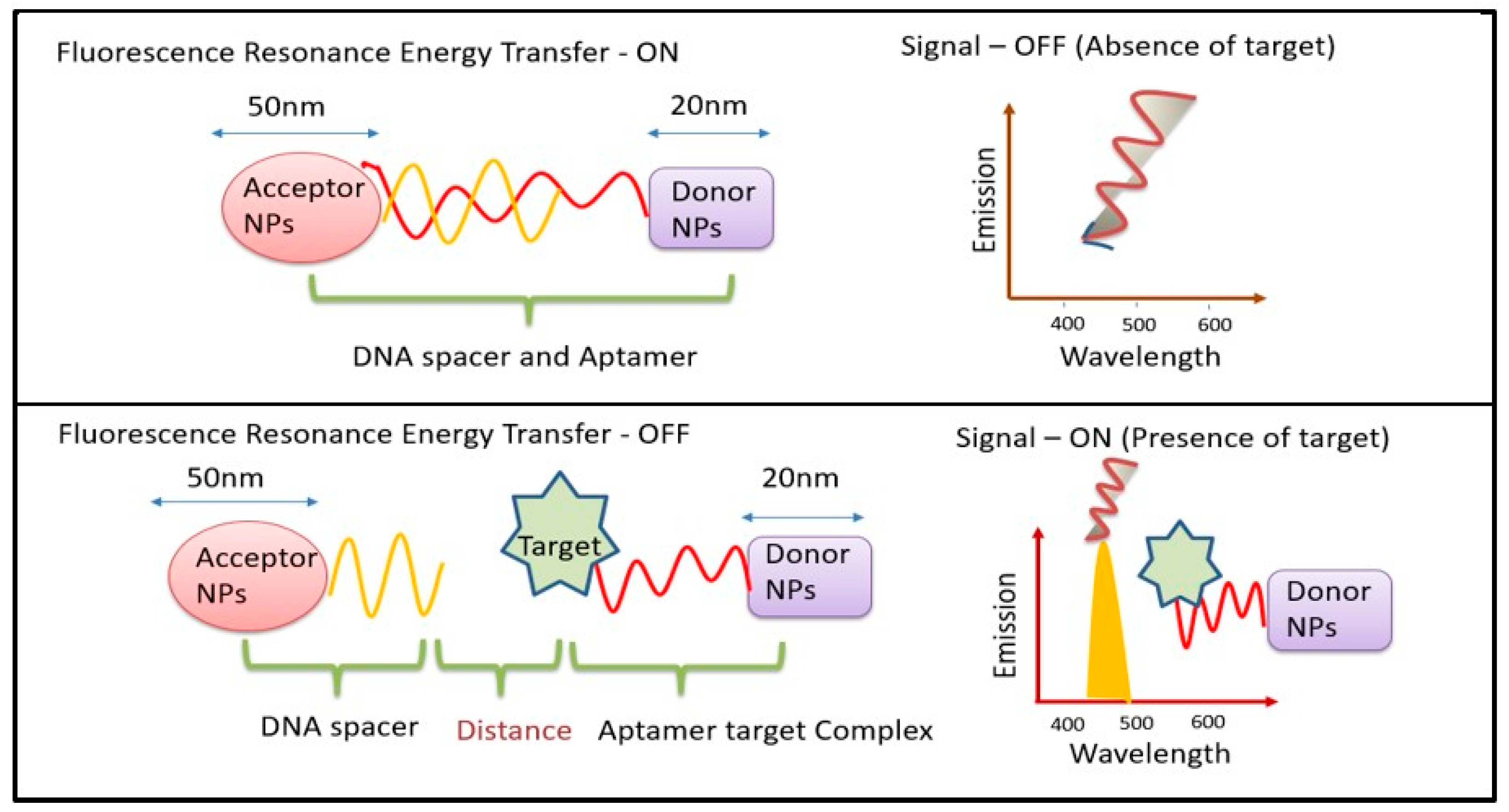

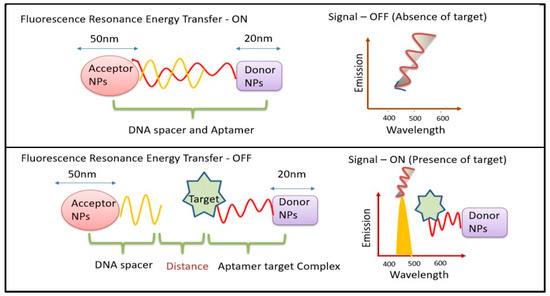

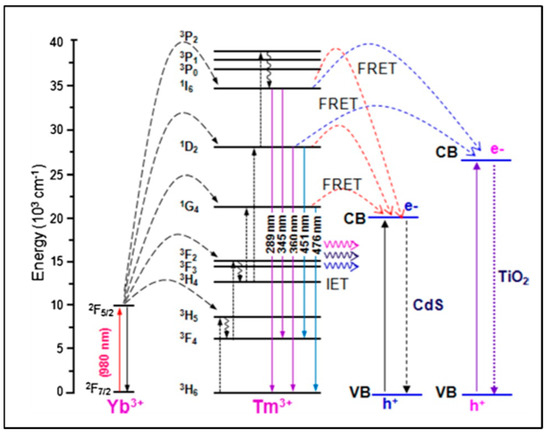

The two main mechanisms used by UCNP-using biosensors are fluorescence and FRET. One of the three methods—fluorescence enhancement (turning on), fluorescence quenching (turning off), or fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)—is employed by fluorescence-based biosensors. Generally, turn/switch/signal-ON or turn/switch/signal-OFF FRET tests are categorized. FRET can occur when an acceptor and a donor molecule are brought close to one another under specific circumstances, as shown in (Figure 1). Numerous techniques can be used to achieve FRET detection and quantification. The phenomenon can be observed by exciting a specimen that contains molecules of both the donor and the acceptor, with light emitted at wavelengths centered near the acceptor’s emission maximum. The two signals can be used for a ratiometric analysis since FRET can result in both an increase in the acceptor’s fluorescence and a decrease in the donor molecule’s fluorescence. The benefit of this method is that it takes interaction measurement independent of the absolute concentration of the sensor. Since not all acceptor moieties are fluorescent, they can be employed to dampen fluorescence. In these situations, there would be a decrease in the signal from interactions that cause a fluorescent donor molecule to become near to such a molecule. As UCNPs have an electron relaxation period in the temporal frame, UCNP-based FRET systems are commonly referred to in the literature as luminescent resonance energy transfer (LRET). The fact that the stimulus needed to activate the donor must be outside of the environment’s absorption range makes UCNPs excellent options for biological-sample detection [16]. An increasing number of UCNPs have been integrated onto nanofibers in recent years to serve as both on- and off-chip transducers in biosensors.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram for mechanism of FRET biosensors.

A one-dimensional nanostructure with a diameter usually between 10 and 100 nm makes up a nanofiber. When loaded with biorecognition molecules, nanofibers with a high surface-to-volume ratio can offer a large sensing surface without removing a significant amount of sample volume [17]. An emerging field of study for biomedical applications is the controlled manufacturing of well-defined fibrillar nano-structured composites, which may be tailored to acquire desired mechanical and chemical properties that can also resemble a cellular matrix. Until now, the majority of UCNP-based sensor devices and applications have been intensity-based; variations in particle concentration result in unfavorable uncertainties and a larger detection limit. PMMA, polystyrene nanofibers, PVP poly(ε-caprolactone), and TiO2 nanofibers have all effectively incorporated UCNPs [18,19]. An oxygen sensor based on the ruthenium complex’s spectrum overlap with the emission of Tm3+ doped UCNPs embedded in polysulfone nanofibers was described by Presley et al. [20], and Fu et al. investigated a microRNA detection technique. Light scattering effects on the surface are enhanced when nanomaterials, such as luminous nanofibers, are incorporated into microfluidic channels, which hinders an adequate signal response [21].

We have covered in depth the effects of UCNP embedding on luminescence efficiency in this review, along with the developments and difficulties associated with UCNP@nanofibers, particularly in (bio)analytical devices. We have also focused on the fundamental process that UCNPs use for these (bio)analytical devices. We have examined both conventional and novel approaches to circumvent the quenching effect of UCNP@nanofibers.

1.1. Impact of Morphology of UCNP@nanofibers on Luminescence Efficiency

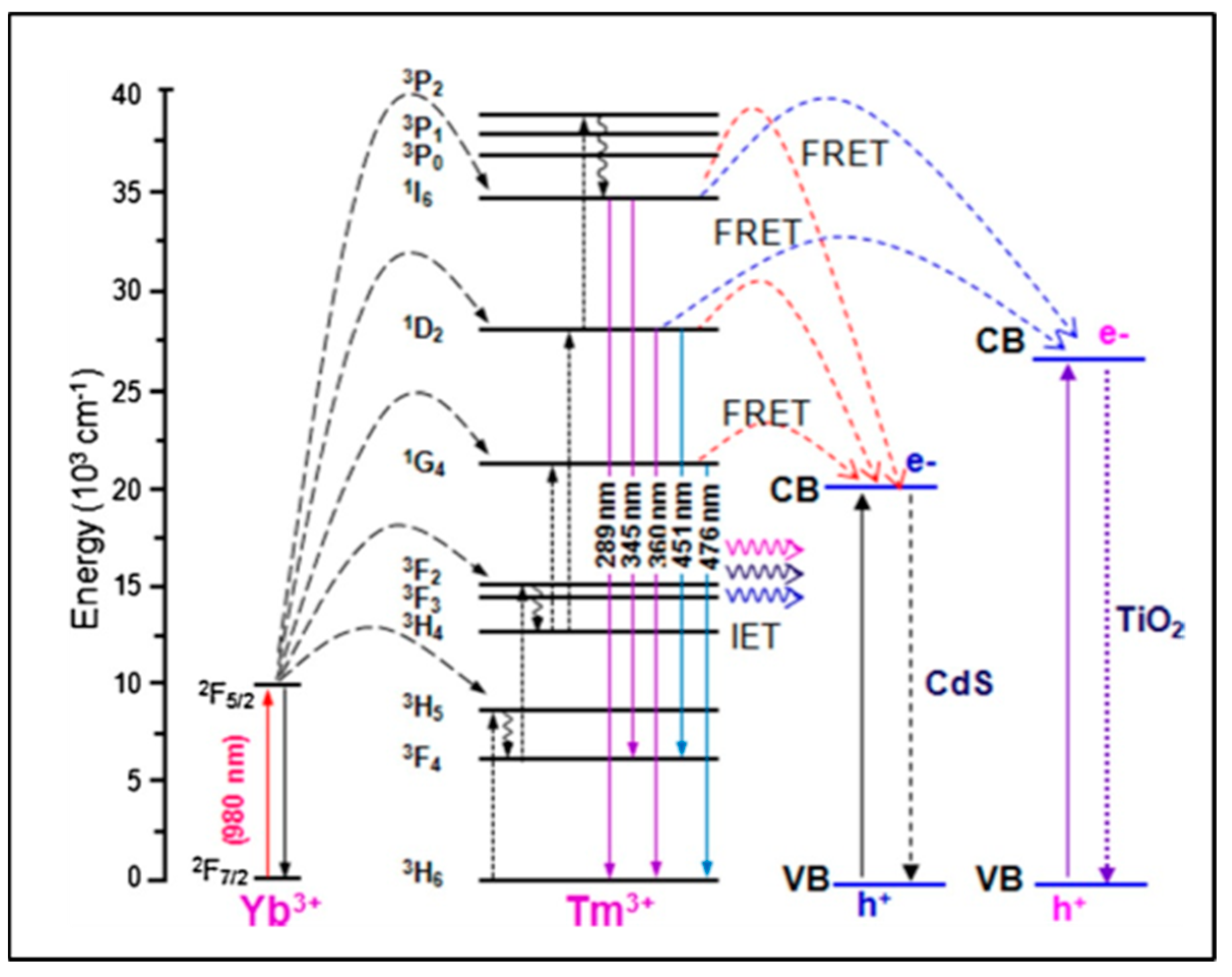

The design and morphology of UCNP@nanofibers have a significant effect on plasmon-enhanced luminescence efficiency which depends on a complex interplay between different dopant ions and host lattices. Electrospinning has been considered as one of the best techniques for fabricating both organic and inorganic nanofibers mainly because the nanoparticles can be easily combined with the fibers to form composite nanofibers. Mainly, the nanoparticles are either doped inside the nanofibers or loaded on their surface. These nanofibers may range within tens to hundreds of nanometers in diameter. Various other parameters that contribute to the formation of nanofibers are the electrospinning solution (polymer blend/nanoparticles/biomolecules), electrical conductivity and rheological properties of the blend, and processing conditions like applied voltage, flow rate of the blend. Yang and colleagues in 2012 reported, for the first time, the upconverted fluorescence of lanthanide-doped YOF nanofibers [22]. Varying the composition of the lanthanides and at 980 nm excitation, blue and red emissions were obtained using YOF: Yb3+,Tm3+, and YOF:Yb3+,Er3+, respectively. The morphology and size of the Ln3+-doped YOF nanofibers were governed using electrospinning parameters like voltage, distance between the tip and collector, relative humidity, and, most importantly, the mass ratio of PVP in the solution. An increase in the diameter of the nanofibers was observed with the increase in the mass ratio of precursor/PVP in solution. Large-scale free-standing and flexible uniform NaYF4:Yb/Tm@NaYF4@TiO2 nanofibers were reported by Qian and colleagues [23] in which water dispersible UCNPs were first assembled into a polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP)/tetrabutyl titanate (TBT) matrix with electrospinning and then calcined at a high temperature to form the TiO2-based nanofibers. The TiO2 nanofibers were activated with the UCNPs via a non-irradiative resonant energy transfer process (FRET) upon excitation with the near-IR light. The energy conversion efficiency between the donor and the acceptor chromophore depends on the structure and distance between the chromophores [24]. The energy transfer occurs through charge–charge interaction between the diploes of the oscillating donor and acceptor molecules that are in close proximity (~1 to 10 nm). In addition to the distance, a favorable orientation of the transition dipole moments of donor and acceptor molecules are also required for an effective FRET. An overlap of lanthanide PL (photo-luminescence) emission and the FRET acceptor absorption spectra can be applied for multiplexed bio-analytical analyses. To enable full-spectrum absorption of solar energy (280 to 800 nm), the UCNPs@TiO2 nanofibers were embedded with semiconductor CdS nanoparticles which caused efficient transfer of the NIR photon energy to the CdS nanoparticles and TiO2 using irradiative energy-transfer (IET) and FRET processes (Figure 2) [25]. With respect to the shape of the host matrix, hexagonal NaYF4 has been reported to be a better upconverting host lattice than the cubic lattice NaYF4. Further, core–shell UCNPs are considered to be the best NIR-to-UV UCNPs, particularly with a concentration range of NaYF4:Yb(20–30%)/Tm(0.2–0.5%)@NaYF4 [26]. The low doping ratio of Tm prevented cross-relaxations. However, the choice of emitting UCNPs is limited to NaYF4:Yb/Tm@NaYF4 with low NIR-to-UV efficiency for application in live systems where quenching of the emission is induced by molecules containing hydroxyl (-OH) groups like water, proteins, etc., [27]. This is due to the high-energy vibrational frequency of -OH which increases the non-radiative relaxation of the excited states of the lanthanides. Bogdan et al. [28] reported the quenching of Er3+ ions with -OH groups due to multiphonon relaxation of the 4I11/24I13/2 and 2H11/2/4S3/24F9/2 transitions. They also mentioned that the relaxation pathways favored the formation of 4F9/2 states with red emission that occurred at the expense of the green luminescence. The requirements of high laser power and heating effects also limit the use of UCNPs to a greater extent. While polymeric nanofibers can be used to harbor the UCNPs to monitor (bio)analytical processes, on the other hand, it remains a challenge to integrate functionalized nanofibers within a microfluidic platform. The main advantage of incorporating the nanofibers is to create more surface area and porosity for immobilizing the recognition moieties for the detection of analyte. The integration of nanofibers into microfluidics has an edge over macro-electrode biomedical devices as the small geometry of a microfluidics chip provides better mass transport and diffusion, a low detection limit, and high signal-to-noise ratio [29]. The detection method based on emission luminescence of the UCNPs can provide a meaningful readout of the desired analysis. The effective synthesis of beta-phase NaYF4:20% Yb3+, 2% Er3+ nanocrystals with controllable dimensions ranging from 4.5 to 15 nm was demonstrated by Cohen and colleagues. They optimized the temperature, ratio of Y3+ to F− ions, concentration of basic surfactants, and other test variables to modify the dimensions of the UCNPs [30]. Lanthanide-doped NaYF4 nanoparticles with governed crystal phase and peak performance of upconversion luminosity with thermal breakdown were demonstrated by Milliron and colleagues using an automated platform [31]. Hence, we could say that by adjusting and monitoring the test variables of the UCNPs and polymeric nanofiber, one can synthesize UCNP@nanofibers of variable sizes and shapes, such as cylinder, beads-on-string, and ribbon [11]. Large-scale synthesis of pure, super-long, single-crystalline YAG nanofibers using one-step calcination has also been reported wherein enhanced Photoluminescence (PL) from solitary YAG:Eu3+ electrospun nanofibers was influenced by Eu3+ ions; this polarized PL also depended on the dimension of the nanofibers [32].

Figure 2.

Irradiative energy transfer (IET) and non - irradiative energy transfer (FRET) processes (Adapted from Ref. [26]).

1.2. Impact of Design of UCNP@nanofibers on Luminescence Efficiency

Pang and his colleagues [33] incorporated hydrophilic NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+ Nanoparticles (UCNP-COOH) into photoluminescent nylon 6 (PA6)/PMMA nanofiber using co-electrospinning and spin-coating processes. The transparent UCNP-COOH/PA6/PMMA nanofiber mats exhibited strong green and red upconverted emission under 980 nm laser excitation, and the upconversion could be tuned by adjusting the weight fraction of the nanoparticles. Two green and one red emission band of Er3+ were observed at 521 nm (2H11/24I15/2), 539 nm (4S3/24I15/2), and 654 nm (4F9/24I15/2). However, the upconverted emission decreased slightly in the polymeric PMMA matrix due to the slow relaxation processes [34]. When NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+ was electrospun in PVP nanotubes, significant upconversion luminescence was observed [35].

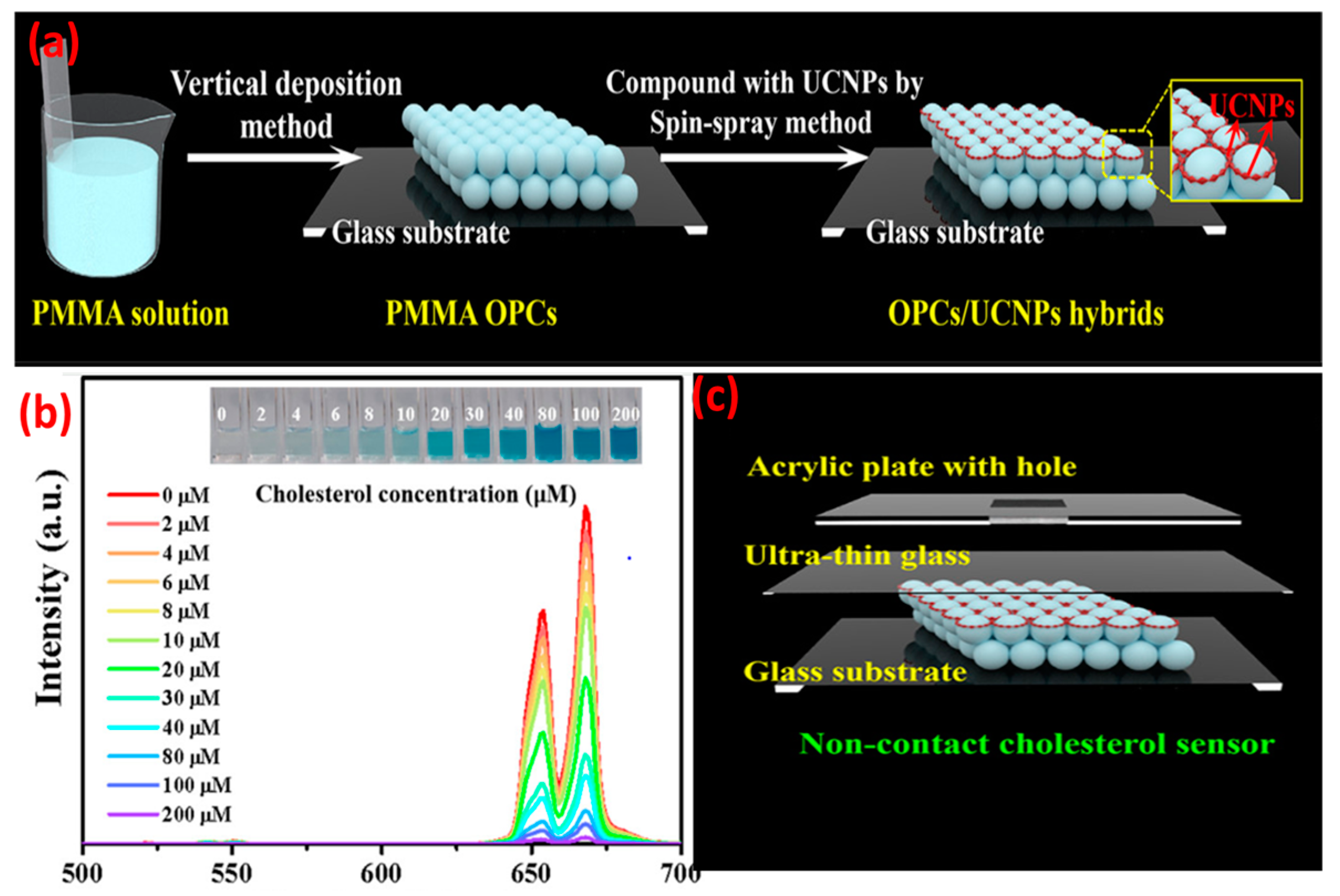

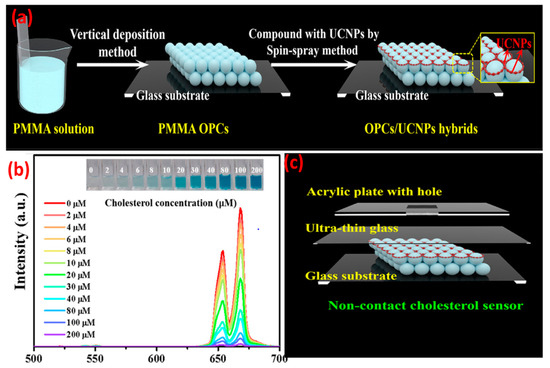

When compared with NaYF4:Yb3+, Er3+ nanoparticles, the UCNPs@PVP nanofibers showed enhanced violet (381 nm), blue (409 nm), green (520 and 541 nm), and red (653 nm) emissions of Er3+. In the case of UCNPs, presence of non-radiative centers on the surface and high-phonon-energy groups would transfer the energy to non-radiative centers and enhance the non-radiation relaxation. Presence of PVP on the UCNPs could effectively eliminate such energy surface traps and suppress the quenching of non-radiative pathways. Concentration of activators in UCNPs has a significant effect on upconversion efficiency. Lahtinen and colleagues [36] studied the effects of varying doping percentages of Tm3+ and Er3+ on luminescence intensity. NaYF4:Yb3+ with Er3+ (3 and 20% doping) and NaYF4:Yb3+ with Tm3+ (0.5 and 8% doping) were selected for measuring the brightness and decay behavior of upconversion at high excitation intensity. NaYF4:Yb3+ with 8% Tm3+ favored 1D23F4 transition in the blue spectral region with an emission at 450 nm. Higher Tm doping also shortened the luminescence decay time to 31 μs. UCNPs with lightly (3%) and highly (20%) doped Er3+ activator ions exhibited a shorter decay time and emissions at 550 nm (4S3/24I15/2 transition). However, higher doping of Er3+ did not show significant enhancement in the emission intensity. There has been a growing interest in using UCNPs in (bio)analytical applications, for example, to monitor the redox state of an enzyme. Oakland et al. [37] monitored the presence of a flavoprotein, pentaerythritol tetranitrate reductase (PETNR), by detecting the variation in energy transfer from the UCNPs (Tm-based) to the flavin cofactor (flavin mononucleotide) of the redox state of PETNR. The emission at 475 nm (1G43H6) was quenched by the enzyme. By altering the rare-earth dopant, the emission profile of the UCNPs can be tuned to monitor biological molecules, e.g., glucose oxidase, vitamin B12, and heme cofactor of cytochrome c. However, it is also important to maximize the apparent energy transfer (AET) between the donor UCNPs and the acceptor biomolecules. This can be achieved by attaching the biomolecules to the surface of the UCNPs and placing the donor–acceptor moieties within the Förster radius. Rare-earth upconversion phosphors (UCPs) were also used to probe the redox chemistry of PETNR [38] wherein the changes in FRET between the emission band of the UCPs and the absorbance band of the enzyme was monitored. With a continuous wave excitation at 980 nm, the UCPs showed two emission bands in the blue (475 nm; 1G43H6) and near IR regions’ (800 nm; 3H43H6) transitions of Tm3+. The separation of the transition bands () allowed for a ratiometric analysis of the enzyme concentration by monitoring the variation in the ratio of the two emission bands. The spectral multiplexing capability of UCNP-QDs was used for the recognition of biotin-streptavidin in a competitive replacement assay. Due to the spectral overlap of QDs FRET acceptor with the UCNPs donor, the PL quantum yield was enhanced [39]. The FRET process was effective because both the donor and acceptor were fluorescent and the distance between them was <10 nm. The study opened the possibility of developing upconverted luminescent probes for the ratiometric detection of enzyme–substrate metabolism. Zhang et al. [40] modified the immobilization technique in which, firstly, the detection solution containing the enzyme (cholesterol oxidase) and different concentrations of cholesterol were mixed and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The cholesterol was catalyzed with the enzyme to produce H2O2 and choleste-4-en-3-one. The generated H2O2 oxidized 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) in the presence of HRP to form the oxidation products (Ox-TMB) which showed intense absorption at ~652 nm that overlapped with the red upconversion of LiErF4:0.5%Tm3+@LiYF4 UCNPs. The detection mixture was dropped into an ultrathin glass sheet containing the UCNPs-and-PMMA-based opal photonic crystal. The monochromic red UC emission of the UCNPs were quenched with Ox-TMB, and the intensity of the quenching was proportional to the cholesterol concentration (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(a) Formation process for OPCs/UCNPs; (b) UC emission change of LiErF4:0.5%Tm3+@LiYF4 UCNPs versus concentration of cholesterol (2 to 200 μM) under 980 nm excitation. (c) Construction of a non-contact OPCs/UCNPs cholesterol sensor. The inset shows the corresponding photographs of the colored products. (Adapted from Ref. [40]).

2. Trends in Embedding UCNP’s in Nanofiber

In addition to natural and synthetic polymers, nanofibers can also be synthesized using ceramic, carbon-based, and semiconducting nanomaterials. Because of their wide diameter range (10–1000 nm), controlled pore size, and potential for use in bio(analytical) devices, polymeric nanofibers have drawn the most attention among various types of nanofiber materials. Some standard spinning methods for synthesizing polymeric nanofibers include melt-blowing, centrifugal spinning, electrospinning, template synthesis, self-assembly, phase separation, and melt spinning. Innovative approaches have been focused on creating reliable and affordable spinning methods, and making them more scalable and easier to use. Considering this, further cutting-edge techniques for the creation of nanofibers have been presented, including solution-blown spinning, CO2 laser supersonic drawing, airflow bubble spinning, plasma-induced synthesis, and electro-blown spinning [41].

2.1. Recent Techniques Used for Embedding UCNPs into Nanofiber

We have explained a few techniques briefly in the following section.

Airflow bubble spinning: Liu and his colleagues fabricated highly oriented PLA nanofibers with nanoporous structures by processing variables of solution concentration and airflow temperature, and collecting distance and relative humidity. The innovative method effectively eliminates the possible safety risks brought about by unanticipated static electricity to manufacture highly orientated nanoporous fibers [42].

Plasma-induced synthesis: CuO and ZnO nanoparticles were formed by bombarding the electrodes’ surface rapidly with energetic radicals, subsequently followed by atom vapor diffusion, plasma development, solution medium water retention, in situ oxygen response, and additional growth. Hu et al. synthesized fiber-shaped cupric oxide (CuO) nanoparticles and flower-shaped ZnO nanoparticles using a plasma-induced technique directly from a copper and zinc electrode pair in water [43].

CO2 laser supersonic drawing: To create nylon 66 nanofibers, as-spun nylon 66 fibers have been drawn at supersonic speeds and then subjected to radiation from a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. Using the fiber injector orifice, air was thrust into a vacuum chamber resulting in a supersonic jet. A nanofiber with an average diameter of 0.337 m and a draw ratio of 291,664 was achieved at a laser power of 20 W and a chamber pressure of 20 kPa. Its drawing speed in the CO2 laser supersonic drawing was 486 ms−1. Two melting peaks were visible in the nanofibers at roughly 257 °C and 272 °C. The lower melting peak is observed at the same temperature as that of the as-spun fiber, whereas the higher melting peak is about 15 °C higher than the lower one [44].

The above techniques can be used for synthesizing UCNPs’ embedded nanofibers which can be used in (bio)analytical devices. As electrospinning is one of the most cost effective and flexible approaches, we are focusing this review specifically on the trends of UCNP@nanofibers synthesized using electrospinning techniques. These techniques have an assortment of perks, which involve the need for effortless, cost-effective furnishings, an outstanding rate of success, the capacity to track the NFs’ morphology, and the practical use of most polymers—even those with large molecular weights [45].

2.2. Advantages of Entrapment of Upconversion Nanoparticles inside Nanofibers

While on one hand, nanofibers provide an anchoring platform and stability to the nanoparticles, on the other hand, nanoparticles provide functionalities to the nanofibers. Therefore, the combination of both constituents gives rise to a newer material that has the advantages of both the components or the synergistic effect from both components. In the present scenario, the development of a single multifunctional platform is in demand in almost every field of application like catalysis, drug delivery, biosensors, bio-imaging, and energy devices. The incorporation of functional nanoparticles into electrospun nanofibers provides improved chemical, electrochemical, mechanical, and optical performances. However, tuning of the material’s structure and its function is crucial in developing an effective single multifunctional platform. The porosity of the nanofibers allows for embedment of a substantial amount of guest molecules on their large surface area and helps in their retention within the nanofibers [46,47]. The field of UCNPs research makes advances on various fronts including chemical and optical stability, and narrow-band-gap emission. Most recent research into the development of the UCNP@nanofiber composite material has demonstrated that nanofibers can provide solutions to the obstacles the mere nanoparticles themselves cannot overcome. This includes protection from the destructive influence of molecular oxygen [48], protection from water quenching exhibiting a 50-fold increase in luminescence intensity [49], and negation of any problem with colloidal stability as the UCNPs are distributed wherever nanofibers are placed. Yet, doping nanofibers with UCNPs changes the nanofiber fabrication conditions [50], which need to be thoroughly investigated and possible light scattering of the fibrous mats must be considered for bioimaging and quantitative analyses [51].

The following section focuses on the inherent advantages demonstrated for quantitative analyses through the integration of UCNPs into nanofibers. UCNPs have been successfully incorporated into electrospun nanofibers made up of polymers (e.g., PMMA, polystyrene, PVP, poly(e-caprolactone)) and demonstrated that unique properties of this composite material enable biomedical in vivo detection and (bio)analytical sensor applications [52]. Specifically, Baeumner and colleagues [49] reported that core–shell NaYF4(20%Yb, 2%Er, 10%Gd)@NaYF4 electrospun PVP nanofibers in a microfluidic channel could overcome limitations like the colloidal stability of the nanoparticles, photo-bleaching of the UCNPs, and high background signals. The porous nanofiber mat helped in retaining the luminescence intensity of UCNPs@nanofibers that was unaltered by changes in buffer or pH, and hence, the in situ generated light onside the platform could be used for sensing or as a light source for photoreactions. Similarly, Song et al. [53] reported the retention of photophysical properties of UNCPs inside a composite nanofiber material. The photoluminescent UCNPs@nanofibers is envisaged to provide insights into biological mechanisms and metabolic pathways as they can serve, unlike traditional imaging tools, as label-free sensitive tools for the detection of changes in metabolic activities in vivo, with high resolution and sensitivity [54]. The composite material can also be used as trigger for drug-release, or as activators in photo-dynamic therapy [55,56].

Zhang et al. [57] reported electrospinning of hydrophilic core–shell β-NaYF4:Yb,Tm@NaYF4 nanoparticles (containing 30% Yb3+ and 0.5% Tm3+) in CdS/PVP/TBT nanofiber mats. The average diameter of the nanofibers was 600 nm in which UCNPs and CdS were embedded. The UCNPs@nanofibers demonstrated good photocatalytic degradation of Rhodium B dyes and the authors envisaged the potential of the UCNPs@nanofibers for applications in solar cells, bio-imaging, and PDT. Along similar lines, Y2Ti2O7:Tm3+/Yb3+ nanoparticles were electrospun into nanofibers which, on irradiation with 980 nm laser, showed prominent emissions at 480, 656, 689, and 803 nm assigned to the Tm3+ transitions of 1G43H6, 1G43F4, 2F2,33H6, and 3H43H6. An increase in the emission intensity was observed with an increase in Yb3+ concentration; however, their shape and positions remained the same [58]. Maria et al. [59] reviewed the applications of lanthanide doped UCNPs for physical sensing by monitoring the change in the photoluminescence of the nanoparticles. Hirsch and colleagues [60] developed a self-assembled Tm3+-doped NaYF4 and gold nanotriangle for NIR to UV upconversion, and it was used for sensing Vitamin B12 in the serum. The plasmonic properties and geometry of the nanoparticles played an important role in emission enhancement by creating localized surface plasmons. Peng et al. [61] used homogenous core–shell NaYF4:Yb/Tm@NaYF4 upconversion nanocrystals as energy donors to a dye receptor for sensitive and rapid monitoring of Zn2+ ions. The sensing platform (PAA-UCNPs) showed blue emissions of Tm3+ at 475 nm under excitation at 980 nm in the absence of Zn2+. The upconversion luminescence was quenched in the presence of Zn2+ with a blue-shift of the band from 475 to 360 nm. Recently, Gu and Zhang [62] provided a comprehensive review on UCNP-based biodetections of inorganic ions, gas molecules, reactive oxygen species, thiols, and hydrogen sulfide. Generally, biological macromolecules like enzymes, proteins, DNA, aptamers, and yeast are immobilized onto nanofibers with physical (embedded or adsorbed) or chemical (cross-linked or covalently bonded) interactions [63] to prevent degradation and retain metabolic efficiency in biological activities [64]. An electrospun poly(methyl methacrylate)/polyaniline material nanofiber was used for the effective immobilization of laccase through both adsorption and covalent binding [65]. The relatively high enzyme immobilizations (110 mg/g and 185 mg/g of laccase attached using adsorption and covalent binding, respectively) were attributed to the fiber porosity and functional groups present on it. Both the systems showed retention of 80% of catalytic activity after one month and after 10 consecutive cycles that proved the stability of the enzymes within the nanofibers. Likewise, nanofibers of terpolymer poly (glycidyl methacrylate-co-methylacrylate)-g-polyethylene oxide containing reactive epoxy groups and a hydrophilic polyethylene oxide branch chain were used to covalently bind lipase for providing good thermal and organic solvent stability to the enzyme [66]. Nylon 6,6 nanofibers were used to embed multiwalled carbon nanotubes for developing an immobilization matrix for glucose. The presence of free aldehyde groups on the polymeric surface provided attachment sites for the enzyme using covalent bonds. The nanofibrous platform was made electroactive by coating it with a conducting polymer,(poly-4-(4,7-di(thiophen-2-yl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)benzaldehyde) wherein immobilization was enhanced due to the large surface area of the nanofibers [67]. Thus, besides providing stability to biological macromolecules against thermal, solvent, proteolytic attack, and other denaturing agents, the nanofibers also provide better control over enzymatic reactions and a platform for embedding multiple enzymes or different admixture molecules [68,69]. Multiple emission bands of UCNPs can be used to design ratiometric enzymatic sensors in which one emission band can be used as a reference and the other can be indicative of the analyte variation [70]. There are two ways in which emission can be modulated: firstly, through the selection of specific biorecognition units (indicator) whose absorption band specifically overlaps the emission band of the UCNPs (not the reference band), and secondly, by monitoring the changes in the emission intensity of the UCNPs in the presence of analyte [71,72]. Ni et al. [73] developed an optical probe using β-NaYF4:Yb3+/Er3+ nanoparticles for sensing cysteine in an aqueous solution. The UCNPs underwent the FRET process, in which an energy transfer took place from the donor UCNPs to an acceptor dye molecule (Rhodamine). A variation in emission spectra of UCNPs is seen in which the green emission intensity at 521 nm and 540 nm decreased with the increasing concentration of cysteine. No change in the red emission at 651 nm was observed because it does not overlap with the absorption band of the dye and hence is used as an internal reference.

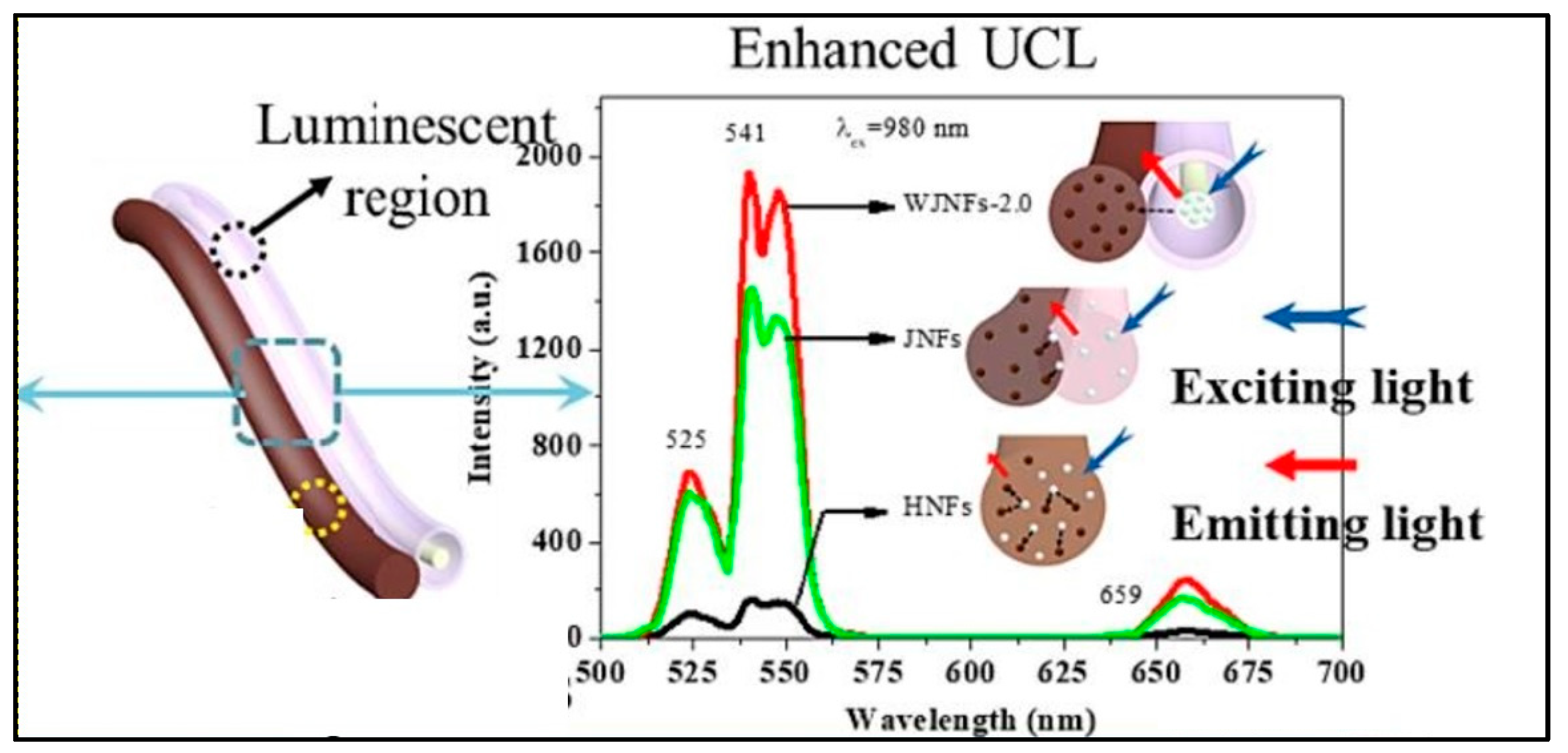

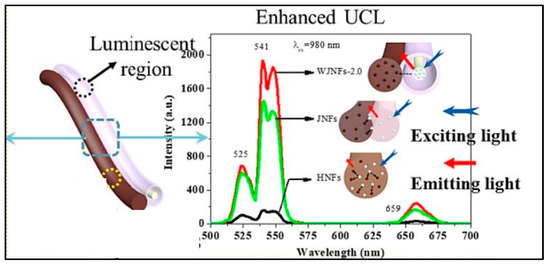

In a work, Sheng et al. created a novel, unusual, 1D wire-in-tube nanofiber, called a Janus nanofiber (WJNF), wherein [YF3+:Yb3+, Er3+@SiO2]/CoFe2O4 was electrospun parallelly to the nanofiber. Simultaneous synthesis of SiO2, rare earth fluoride, wire-in-tube nanofibers, Janus nanofibers, and magnetic CoFe2O4 was achieved without the need for any extra protective gases. The in situ synthesis of unique Janus nanofibers via a one-pot mode offers the avoidance of post-processing procedures, and significantly improved the luminescence property (Figure 4) [74].

Figure 4.

Enhanced PL (Phololuminescence) of UCNP@Nanofiber ([YF3+:Yb3+, Er3+@SiO2]//CoFe2O4 WJNFs) (Adapted from [74]).

The trend to embed fluorescent or upconverted nanoparticles onto the enzyme immobilized nanofiber for the monitoring of enzymatic activities is on rise. A change in the luminescence emission or quenching of the fluorescent or upconverted nanoparticles on exposure to varying physical or chemical environments forms the basis of sensing or imaging. Thus, once the nanoparticles are embedded or attached to the enzyme mobilized nanofibers, they contribute to a highly sensitive and specific sensing platform due to the specificity of the analyte recognition unit. Functionalization of the nanofibers with recognition units can synergize the luminescence response and ratiometric sensing of analytes. However, assembling the UCNPs on the functionalized nanofibers (containing specific enzymes, proteins, antibodies, etc.) and optimization of the sensing layer are the challenges of an electrospun nanofiber. A major advantage of an electrospun-based sensing platform is that, on one hand, the nanofibers can be easily functionalized with bio-recognition units like enzyme, proteins, etc., using conventional coupling methods, while on the other hand, the nanoparticles can be directly incorporated into spinning solution. Therefore, the functionalization method becomes easy and post-processing steps can be avoided. Further, the bio-recognition molecules and nanoparticles could retain their functions and demonstrate better stability. Progress has been made in increasing the luminescence of the UCNPs embedded in the nanofibers.

2.3. UCNP@nanofibers as Sensing Platform for Bio(analytical) Assays

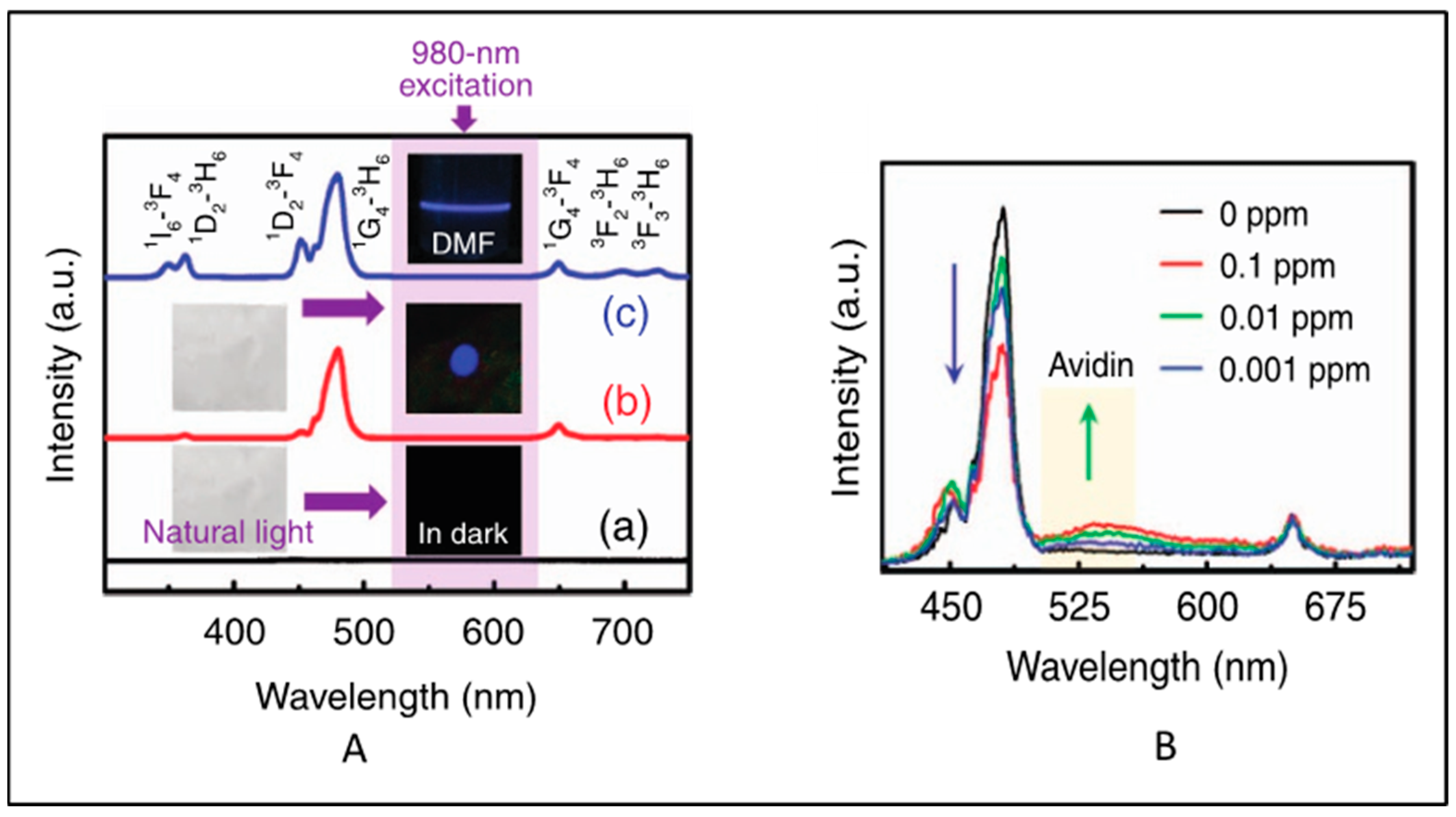

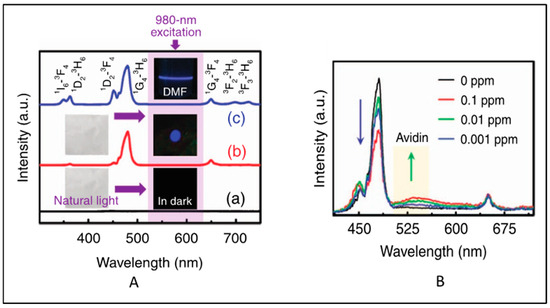

This section focus on the latest research on functionalized electrospun nanofibers containing signal-generating luminescent moieties. UCNPs were used as an NIR-fluorescent-monitoring probe for non-invasive tracking of the degradation of hydrogel [75]. In this work, the polydopamine (PDA)-coated yolk−shell nanoparticles NaGdF4:Yb3+,Er3+@NaGdF4@PDA were cross-linked with carboxymethyl chitosan and sodium alginate hydrogel, and the enzymatic degradation of the hydrogel in lysozyme was monitored using the fluorescence intensity of the UCNPs. In 2018, Yao et al. [76] reported a color-tunable CdTe-QDs-based luminescent nanofibers for glucose sensing. Core–shell UCNPs (NaYF4:Yb3+/Er3+@NaYF4) in PMMA nanofibers exhibited luminescence at 540 (4S3/24I15/2) nm and 660 nm (4F9/24I15/2) upon pulsed near-infrared excitation [77]. Yb3+/Tm3+and Yb3+/Er3+ co-doped NaYF4 nanoparticle/polystyrene (PS) hybrid free-standing nanofiber was used as a fluorescence sensor for detecting avidin from a single water droplet [78]. No upconversion was observed in pure PS films. After incorporation of the UCNPs into the PS nanofibers, strong blue UCL (1G43H6 transition of Tm3+) was observed upon 980 nm excitation (Figure 5A). However, the intensity ratio of pure NaYF4:Yb3+, Tm3+ NPs decreased after embedding in the PS nanofibers. This may be due to the fact that some vibrational transitions of PS may have interacted with the excited levels of NaYF4:Yb3+, Tm3+ NPs and caused a nonradiative energy transfer process. However, the intensity of NaYF4:Yb3+, Er3+ NPs were significantly enhanced after embedding within PS. This may be due to the effective suppression of the thermal effect caused by laser excitation and the cross-relaxation phenomenon [79]. When avidin droplet-loaded NaYF4:Yb3+, Tm3+/PS HFM was excited with a 980 nm laser, an emission band at 530 nm emerged, which increased with the increase in avidin concentration. However, the blue Tm3+ band at 480 nm decreased with the increase in avidin concentration. This is attributed to the fluorescence group of avidin that adsorbed the blue photon and re-emitted a lower-energy green photon through a down-conversion luminescence process (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

(A) Standardized UC emission spectra of (a) PS nanofibrous membrane (b) the NaYF4:Yb3+,Tm3+/PS HFM and (c) the NaYF4:Yb3+,Tm3+ NPs dispersed in DMF solution. The insets show the corresponding optical images obtained under natural-light or 980 nm LD irradiation. (B) Normalized UC emission spectra of the NaYF4:Yb3+,Tm3+/PS HFM loaded with a single water droplet containing different concentrations of avidin (Adapted from Refs. [78,79]).

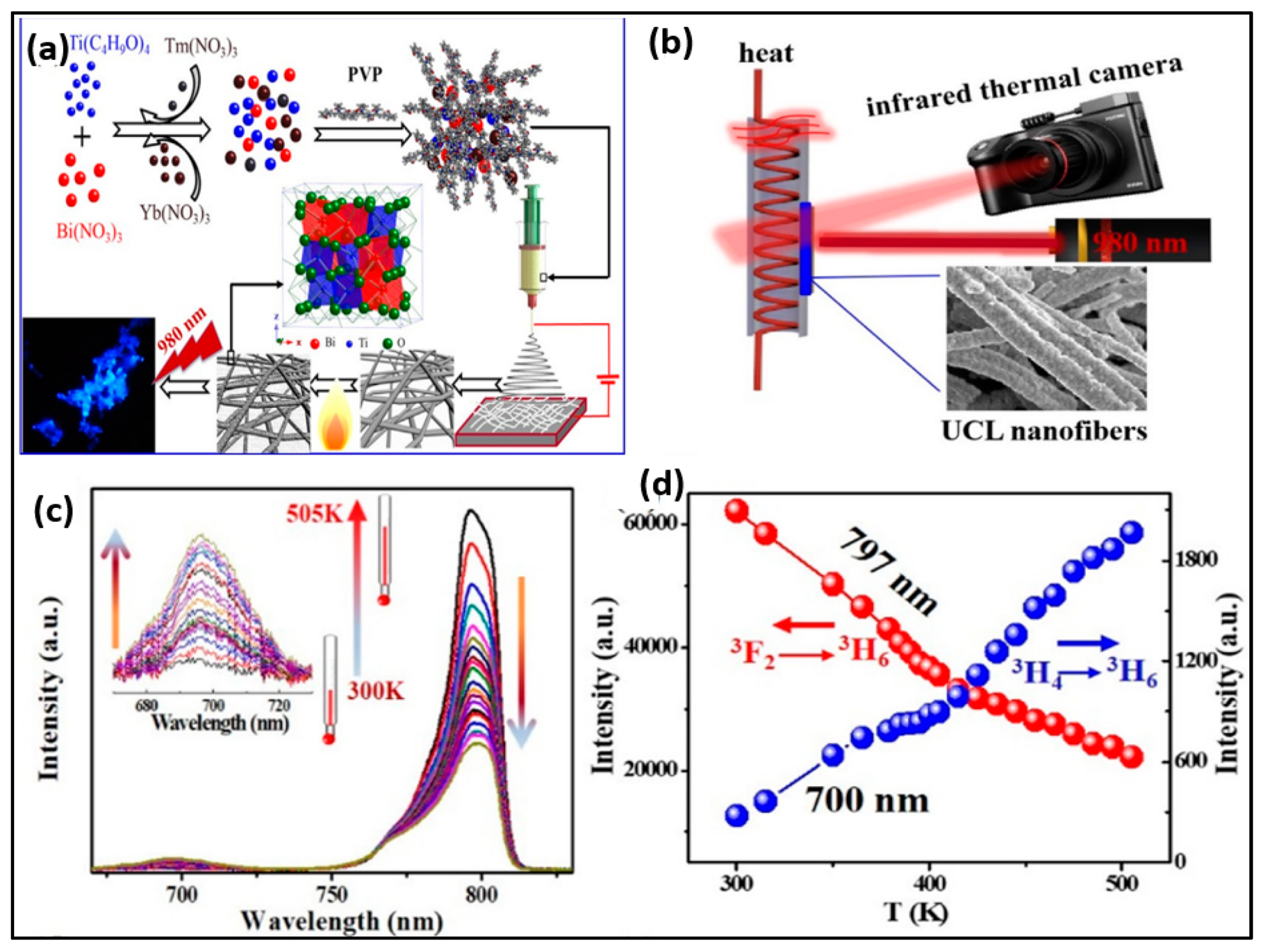

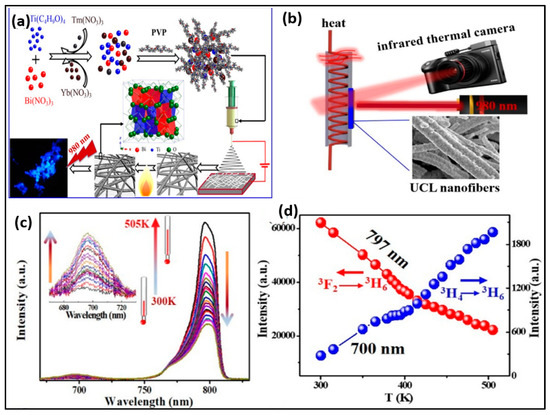

By employing the electrospinning methodology, Ge et al. constructed pyrochlore phase Bi2Ti2O7 matrix nanofibers over an assortment of molar ratios (Tm3+/Yb3+ = 1:2–20) measuring at about tens of micrometres in their length and 200–300 nm in their diameter, producing PL emission bands in the range of 400–800 derived from the transitions of 1G4 → 3H6, 1G4 → 3F4, 3F2,3 → 3H6, and 3H4 → 3H6, respectively. The particles had strong blue emission, and the temperature-sensing properties of Bi2Ti2O7:Tm3+/Yb3+ fibers (Tm3+/Yb3+ = 1:8 showed a relatively high sensitivity value of 0.024 K−1 at 300 K. The findings showed that for the purpose of detecting the surface temperature, the FIR approach had superior temperature-sensing capabilities over the thermal infrared imager. This finding will open up new avenues for the development of contactless FIR temperature-sensing applications of upconversion materials and spark a great deal of interest in upconversion studies in bismuth-based oxides [80].

Liu et al. synthesized lanthanide doped polyacrylonitrile (LOS-EY/PAN) nanofibers and proposed a dual temperature feedback fluorescence intensity ratio technique, which opened up the possibility of optical temperature sensing in micro-regions and created a ratiometric strategy for the excitation of Er3+ ions using a unique upconversion (UC) process. Cross-relaxation (CR) of Er3+ ion pairs have been defined as the odd three-photon illumination process implicated for both the red and green UC emissions of Er3+ single doping. Energy transfer from Yb3+ to Er3+ plays a dominant role, and the excitation procedure transforms into the traditional two-photon process. When Yb3+ comes into play, the CR process is compelled to pause, and energy is absorbed by Yb3+ as a result of its massive absorption cross-section contrasted to that of Er3+. With the reorganization of the excitation mechanism, the overall rise in Er3+ emission is followed by a boost in the aggregate quantum yield, which increases from 8.31 × 10−5 to 1.23 × 10−3. Relevant light stimulation enhances the proportion of signal to noise in usage and retains the degree of sensitivity at a high level of 1.29% K−1, proving the remarkable self-feedback nano-temperature-sensing function of LOS-EY/PAN fibers offer as an adaptive sensing component for fabrics and biomedical devices (Figure 6) [81]. Liu et al. prepared Gd2O3:Er3+@Gd2O3:Yb3+ core–shell nanofibers using electrospinning. Visible light upconversion photoluminescence reveals a prominent red emission band with distinct splitting peaks under 980 nm excitation, which is caused by a dramatic splitting of the energy level. The visible emissions exhibit temperature sensitivity within the 303–543 K range. The red emission demonstrates quenching with the rise in temperature. Thermal quenching had an activation energy of 0.1408 eV. The temperature-dependent multi-peaks of red emission were explored, and absolute sensitivity was obtained based on the valley and peak ratio of I680.31 nm/I683.03 nm in upconversion emission spectra. These findings imply that Gd2O3:Er3+@Gd2O3:Yb3+ nanofibers are good candidates for luminescence thermometry, which could lead to their use in both industry and scientific study [82]. Composite material nanofiber fabrication requires delicate circumstances for reaction; therefore, the outcome of the composite nanofiber’s dimensions can be difficult to control. Zhaoxue et al. synthesized the NaYF4 upconversion material, which is composed of Yb3+ as well as Er3+ rare earth ions. Subsequently, a single-stage electrospinning methodology has been employed for encasing the upconversion radiant NaYF4: Yb3+, Er3+ nanoparticles (NaYF4 NPs) beneath poly(lactide-co-glycolide)-gelatin (NaYF4-PLGA-gelatin). A detailed analysis was conducted on the impact of NaYF4 NPs on the mechanical properties, hydrophilicity, upconversion emission spectra, morphology, and degradation of the electrospun NaYF4-PLGA-gelatin nanofiber. When 5 mg/mL of NaYF4 NPs are encapsulated, the electrospun NaYF4-PLGA-gelatin nanofiber exhibited maximum luminous intensity. When compared to nanofibers with various concentrations, the mechanical properties of those with this encapsulated content are likewise often higher. Furthermore, a range of NaYF4 NP concentrations in the electrospun NaYF4-PLGA-gelatin nanofibers exhibit excellent hydrophilicity and degradation rates [83]. In a study, Ag@SiO2 and upconversion nanorods were electrospun into the nanofibers to create filamentous signaling sheets with superior upconversion luminescence, extremely high hydrophobic material, and adaptability. Riboflavin and pH were independently detected in human bloodstreams using the nanofibers. Using a single droplet, the fibrous signal material can identify levels as low as 0.01 ppm riboflavin and 0.1 pH. The droplet of material can be readily ejected after recognition, allowing for great reusability without impacting detection efficiency [84].

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic showing mechanism of Bi2Ti2O7:Tm3+/Yb3+ upconversion nanofibers; (b) schematic diagram for the measurement process; (c) temperature-dependent spectra for Bi2Ti2O7:Tm3+/Yb3+(Tm3+/Yb3+ = 1:8); (d) luminescence intensity of the two thermal coupled levels (3H4, 797 nm; 3F2,3 700 nm) at various temperature samples (Adapted from [80]).

Table 1 presents an overview of various types of polymer that are used to embed UCNPs to form nanofibers.

Table 1.

Various polymers used to embed UCNPs to form nanofibers and their applications.

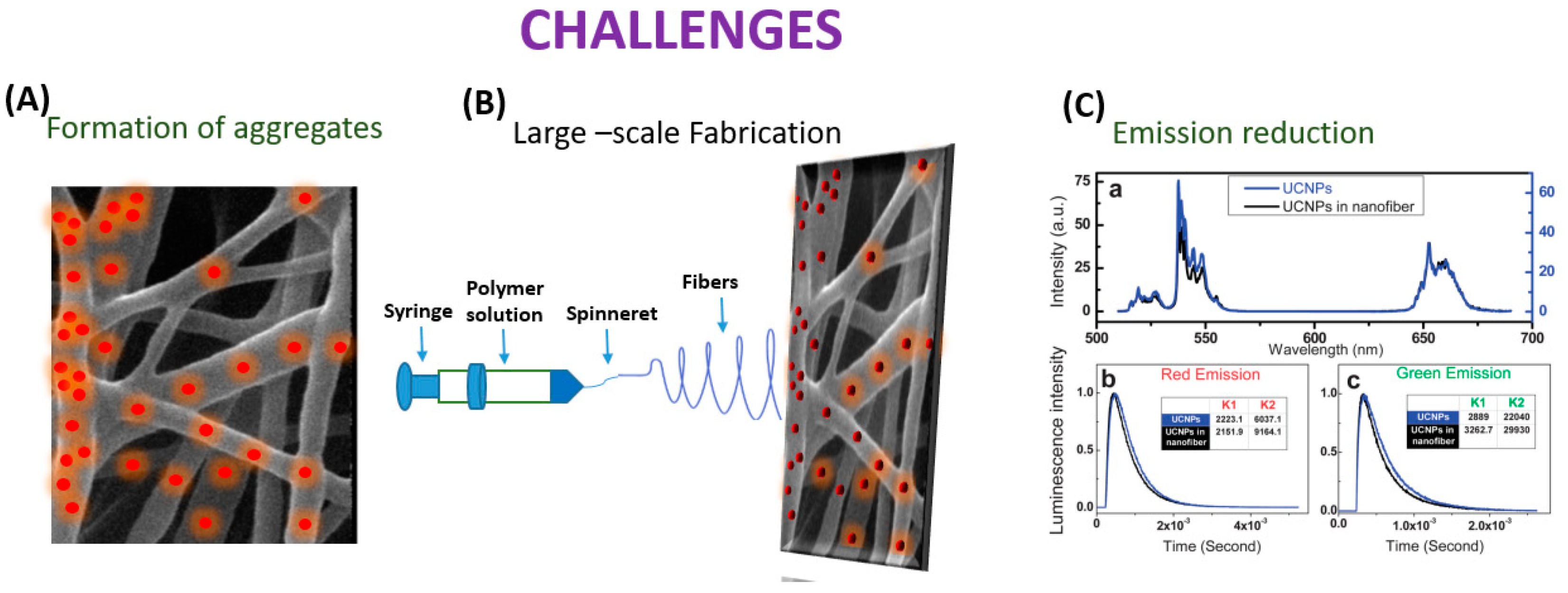

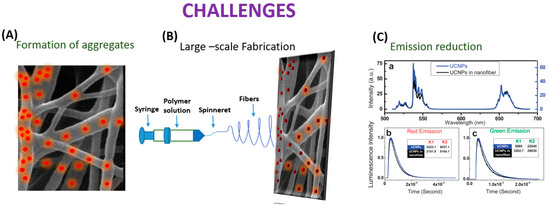

3. Challenges in Embedding UCNP’s in Nanofiber

Even though the process of electrospinning UCNPs into nanofibers has advanced significantly, there is still an assortment of areas that need to be improved (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram depicting challenges in embedding UCNP’s in nanofiber.

In the electrospinning process, UCNPs have the potential to coalesce while UCNP@ nanofibers are being spun. According to Bao et al.’s research, the anisotropic propensity of the UCNPs to coalesce into particle chains near the hexagonal face was most likely caused by the non-polar hydrocarbon tails of the oleate capping ligands maximizing surface-area contact and van der Waals interaction. By using novel electrospinning techniques like coaxial, which provide more control over the orientation of the electrospun nanofibers, this constraint has been lessened. Additionally, Bao discussed the UCNP/PMMA nanofibrous films, and the UCNPs’ powder’s green emission to red emission luminescence intensity ratio (IG/R) in the spectra of the UCNP/PMMA nanofibrous films was lower than in the spectra from the powdered UCNPs. The process of creating sensors using electrospinning is fraught with difficulties. The primary goal is to create a homogenous, spinnable mixture. The consistency of the mixture and the proportions of the components are vital in this instance [85]. RE ions in matrix forms of polymers typically demonstrate relatively low emission efficiency, but effective fabrication of the crystal fiber via electrospinning is not doable, as demonstrated by Toncelli et al.’s review studies. On the other hand, when growing oxide crystal nanofibers, a mixture with the appropriate viscosity for the method can be acquired through the application of a polymeric precursor (which is typically PVP).

The material can then be eliminated through the ensuing calcination procedure, which can occur at conditions lower than those usually necessary for the stable state development of the crystal host. Following the calcination procedure, a further fluorination step is required for the development of fluoride crystal nanofibers. This makes the process more difficult because hazardous reagents are used in the fluorination process. Because of this, incorporating fluoride crystal nanoparticles into polymer fibers is another well-liked method. Fluoride materials are widely used as bulk crystal hosts and as nanoparticles. However, due to the relatively small number of published papers regarding oxide materials, the electrospinning growth of fluoride fibers is still in its early stages. When formed in bulk crystal form, fluoride materials need very high purity of the starting materials with careful management of the growing environment since even very low levels of contaminants greatly impair the emission efficiency of rare earth ions. This kind of material is typically generated using electrospinning and fluorinating oxide electrospun fibers. Bypassing the inherent challenges in the electrospinning growth of fluoride crystal matrixes, the bottom-up growth of nanoparticles has been optimized to produce high-quality monodisperse nanoparticles. Adding these high-quality nanoparticles to polymeric fibers is likely the simplest method to produce highly efficient upconverting nanofibers. To regulate the quality and shape of the materials developed, several other growth factors, such as the composition of the starting solution, the flow rate, the voltage, and the distance between the needle and collector, must be optimized. Moreover, the collector temperature and atmosphere humidity can have a large influence on the fiber quality. The electrospinning technique naturally leads to the growth of amorphous materials; therefore, a calcination step is always needed to obtain crystal nanofibers [86]. Among the obstacles and difficulties is the complexity of the fabrication process, the range of materials that can be spun, the homogeneity of the fibers, and reproducibility. Moreover, one of the present difficulties that researchers hope to solve in the future is the creation of portable sensors without the requirement for large apparatus. Additionally, it becomes difficult to quench and enhance the luminescence of UCNP@nanofiber. When UCNPs are embedded into nanofibers, aggregates may form, which could change the characteristics of both UCNPs and the nanofibers and limit their use in (bio)analytical devices as well as the needle–collector separation. Researchers should try to focus on the enhancement of the luminescence of the UCNP@nanofibers by changing the strategies of embedding lanthanide doped materials into the nanofibers. Enhancing UCNPs with multi-excitation wavelengths or improved UV emission is vital. Well-controlled nanostructures may also have greater potential to increase the energy transfer efficiency of UCNPs [87]. Despite the demands of industrialization, the large-scale production of UCNPs@nanofiber continues to be difficult. There are problems with jet interactions, needle clogging, and cleaning with multi-needle collaborative electrospinning. Initially, the needle-free electrospinning approach produces a lot of nanofibers, but their dispersion is incredibly uneven [88].

Future perspectives: Future research in replacing time-consuming analytical monitoring methods with a real-time monitoring system that is quick, sensitive, and efficient has been realized and found to be important in designing a (bio)analytical monitoring system. UCNPs have emerged in applications of biochemical sensors due to their unique and extraordinary optical and chemical features of having a high quantum yield, high resistance to photo-bleaching, low toxicity, long-term lifetime, narrow emission bandwidths, as well as very low optical background noise. Integration of UCNPs@nanofibers into microfluidic systems using bacterial cellulose nanopaper and chitin nanofibers papers [89] has opened an era of rapid and sensitive analyses of analytes using the luminescence of the nanoparticles. This new class of nanosensor can also be used to monitor dynamic processes at the molecular level upon interaction with NIR light, which is often inaccessible using other techniques. Analytical probes based on UCNPs can be used in both solution-phase and in heterogeneous assays and can, therefore, surpass conventional probes (like QDs, dyes, etc.). Heterogeneous assays based on UCNPs@nanofibers can be achieved using a microfluidic platform to fabricate point-of-care devices for on-site monitoring. Such a microfluidic platform can be devised if the UCNPs are of a smaller size, typically less than 10 nm, the synthesis of which is quite challenging. Further, absence of optical background interference in UCNPs, as opposed to other fluorescent molecules, can lead to the development of digital immunoassays where every UCNP can be counted as an optical probe. For that, it is important to synthesize the UCNPs of appropriate size, surface chemistry, and chemical entities (definite concentration/types of sensitizer and activators) and incorporate it in a suitable nanofiber matrix and ensure that they are bright enough to be detected at the single-nanoparticle level. Also, it is important to improve the UC emission efficiency and retain the same levels once it is inside the nanofibers. The upconversion emissions are adversely affected by the presence of surrounding molecules and, therefore, significant research is directed towards improving it, and the upconversion intensity and signal contrast [90]. UCNPs also provide a vehicle in sensing applications by emitting UV-Visible light and providing relevant signals for the measurements. Tsai and colleagues [91] used the green emission band of the UCNPs which was quenched with a pH-dependent inner filter effect (IFE), while the red emission band remained unchanged and acted as the reference signal for ratiometric pH measurements. Shen and colleagues [92] used biocompatible CaF2 to form an epitaxial shell on the UCNPs that showed high optical transparency and was effective in preserving the emission quenching in aqueous medium. The similarity in the lattice of CaF2 and NaYF4, a = 5.448 Å (CaF2, a = 5.451 Å) has paved the way in forming heterogeneous core–shell UCNPs that could provide resistance to aqueous quenchers and further research in this direction would lead to the use of UCNPs in photonics and biophotonics.

In this trend article, we have discussed UCNP-based nanofibers for the detection of analytes and their road to commercialization. A significant increase in sensitivity, ease of use, and easy fabrication techniques has added value to the miniaturized UCNP@nanofibers systems. The possibilities of integrating sensing transducers in microfluidic platforms and their smaller footprints can serve as important tool for evaluating bio(analytical) processes at the point of care. A microfluidic platform with a nanoengineered interface can serve as a sensor for several disease biomarkers. Though there are several benefits of an integrated microfluidics platform, commercialization of such systems may take a slightly longer time. One of the reasons may be since commercialization not only depends on innovations, but also on the feasibility of using the platform on a larger scale.

In our perspective, such systems could be the future of smart sensing technology; particularly when conjugated with a recognition moiety, for example an enzyme, sensors for specific analytes with low detection limit and specificity can be fabricated. However, such a device must be extremely robust and user-friendly. To be used for analytical applications, it is also important to investigate the sensitivity and multiplexing abilities of the UCNPs@nanofibers. For significant optimization, simple and economically feasible set ups are required for commercialization. For optimization, with respect to the activity and accessibility of the bioreceptor, binding events and signal transductions are required for accuracy, sensitivity, and selectivity of a bio(analytical) assay. The future perspectives of the development of a multiplexed microfluidic analytical system and the generation of organ-on-a-chip platforms are envisaged. An integration of bio-imaging and tissue engineering on a same platform may find applications in monitoring different organs and their responses to cellular parameters in situ, paving the way to advancing the field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C., investigation, S.C., writing, N.D. and S.C., Formal analysis, N.D., writing—review and editing, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

N.D. and S.C. are grateful to SVKM’s NMIMS University, Mumbai and Hanse-Wissenschaftskolleg—Institute for Advanced Study (HWK), Delmenhorst, respectively, for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Khandurina, J.; Guttman, A. Bioanalysis in microfluidic devices. J. Chromatogr. 2002, 2, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Soler, M.; Belushkin, A.; Yesilkoÿ, F.; Altug, H. Optofluidic nanoplasmonic biosensor for label-free live cell analysis in real time. In Plasmonics in Biology and Medicine XV; International Society for Optics and Photonics: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; p. 105090. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, Z.; Mahmoudifard, M. Pivotal role of electrospun nanofibers in microfluidic diagnostic systems—A review. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 30, 4602–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Ma, P.; Hou, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Li, C.; Lin, J. Current advances in lanthanide ion (Ln3+)-based upconversion nano-materials for drug delivery. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1416–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Wu, D.; Sathian, J.; Xie, X.; Ryan, M.; Xie, F. Tuning the upconversion photoluminescence lifetimes of NaYF4:Yb3+, Er3+ through lanthanide Gd3+ doping. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Tian, G.; Ren, W.; Yan, L.; Jin, S.; Gu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Lia, J.; Zhao, Y. Design of multifunctional alkali ion doped CaF2 upconversion nanoparticles for simultaneous bioimaging and therapy. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 3861–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; El-Banna, G.; Han, G. Nanoscale “fluorescent stone”: Luminescent calcium fluoride nanoparticles as theranostic platforms. Theranostics 2016, 13, 2380–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfield, D.J.; Borys, N.J.; Hamed, S.M.; Torquato, N.A.; Tajon, C.A.; Tian, B.; Shevitski, B.; Barnard, E.S.; Suh, Y.D.; Aloni, S.; et al. Enrichment of molecular antenna triplets amplifies upconverting nanoparticle emission. Nat. Photonics 2018, 12, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, Q.; Feng, W.; Sun, Y.; Li, F. Upconversion luminescent materials: Advances and applications. Chem. Rev. 2015, 1, 395–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G. Advances in the theoretical understanding of photon upconversion in rare-earth activated nanophosphors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 6, 1635–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Luu, Q.A.N.; Zhao, Y.; Fong, A.; May, P.S.; Jiang, C. Upconversion polymeric nanofibers containing lantha-nide-doped nanoparticles via electrospinning. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 7369–7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, S. Upconversion nanoparticle-based fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay for organo- phosphorus pesticides. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 68, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Dumlupinar, G.; Andersson-Engels, S.; Melgar, S. Emerging applications of upconverting nanoparticles in in-testinal infection and colorectal cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Wang, F. Emerging frontiers of upconversion nanoparticles. Trends Chem. 2020, 5, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroter, A.; Hirsch, T. Control of Luminescence and Interfacial Properties as Perspective for Upconversion Nanoparticles. Small 2023, 2306042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, N.; Chandra, S. Upconversion nanoparticles: Recent strategies and mechanism based applications. J. Rare Earths 2022, 9, 1343–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Kundu, S.C. Electrospinning: A fascinating fibre fabrication technique. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, Z.; Taylor, J.; D’Souza, S.; Britton, J.; Nyokong, T.J. Fluorescence behaviour and singlet oxygen production of aluminium phthalocyanine in the presence of upconversion nanoparticles. J. Fluoresc. 2015, 25, 1417–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, M.; Hoecherl, K.; Schlosser, M.; Baeumner, A.J.; Wongkaew, N. Printable 3D carbon nanofiber networks with embedded metal nanocatalysts. ACS App. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 39533–39540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presley, K.; Hwang, J.; Cheong, S.; Tilley, R.; Collins, J.; Viapiano, M.; Lannutti, J. Nanoscale upconversion for oxygen sensing. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 70, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, G.; Gu, T.; Xie, C.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; Best, S.; Han, G. Production of a fluorescence resonance energy transfer(FRET) biosensor membrane for microRNA detection. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 65, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Qin, G.; Zhao, D.; Zheng, K.; Qin, W. Synthesis and upconversion properties of Ln3+ doped YOF nanofibers. J. Fluo. Chem. 2012, 140, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, C.-L.; Peng, H.-Y.; Cong, H.-P.; Qian, H.-S. Near-infrared photocatalytic upconversion nanoparticles/TiO2 nanofibers assembled in large scale by electrospinning. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2016, 33, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.C.D.; Algar, W.R.; Medintz, I.L.; Hildebrandt, N. Quantum dots for Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET). TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 125, 115819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, C.-L.; Wang, W.-N.; Cong, H.-P.; Qian, H.-S. Titanium dioxide/upconversion nanoparticles/cadmium sulfide nanofibers enable enhanced full-spectrum absorption for superior solar light driven photocatalysis. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Boyer, J.-C.; Habault, D.; Branda, N.R.; Zhao, Y. Near infrared light triggered release of biomacromolecules from hydrogels loaded with upconversion nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16558–16561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arppe, R.; Hyppänen, I.; Perälä, N.; Peltomaa, R.; Kaiser, M.; Würth, C.; Christ, C.; Resch-Genger, U.; Schäferlinga, M.; Soukkaa, T. Quenching of the upconversion luminescence of NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+ and NaYF4:Yb3+,Tm3+ nanophosphors by water: The role of the sensitizer Yb3+ in non-radiative relaxation. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 11746–11757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, N.; Vetrone, F.; Ozin, G.A.; Capobianco, J.A. Synthesis of ligand-free colloidally stable water dispersible brightly luminescent lanthanide-doped upconverting nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Jin, S.; Nugen, S.R. Water-soluble electrospun nanofibers as a method for on-chip reagent storage. Biosensors 2012, 2, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, A.D.; Chan, E.M.; Gargas, D.J.; Katz, E.M.; Han, G.; Schuck, P.J.; Milliron, D.J.; Cohen, B.E. Controlled Synthesis and Single-Particle Imaging of Bright, Sub-10 nm Lanthanide-Doped Upconverting Nanocrystals. ACS Nano 2012, 3, 2686–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.M.; Xu, C.X.; Mao, A.W.; Han, G.; Owen, J.S.; Cohen, B.E.; Milliron, D.J. Reproducible, High-Throughput Synthesis of Colloidal Nanocrystals for Optimization in Multidimensional Parameter Space. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 1874–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Xiao, X.; Chi, Y.; Qian, B.; Liu, X.; Ma, Z.; Wu, E.; Zeng, H.; Chen, D.; Qiu, J. Size-dependent polarized pho-toluminescence from Y 3 Al 5 O 12: Eu3+ single crystalline nanofiber prepared by electrospinning. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 8, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hongrui, J.; Ye, H.; Dai, T.; Yin, X.; He, J.; Chen, R.; Wang, Y.; Pang, X. Facile fabrication of transparent and upconversion photoluminescent nanofiber mats with tunable optical properties. ACS Omega. 2018, 3, 8220–8225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriev, O.P. Effect of confinement on photophysical properties of P3HT chains in PMMA matrix. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.; Hong, X.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chu, X.; Shaymurat, T.; Shao, C.; Liu, Y. Up-Conversion luminescence of NaYF4:Yb3+/Er3+ nanoparticles embedded into PVP nanotubes with controllable diameters. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 5787–5791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, S.; Liisberg, M.K.; Raiko, K.; Krause, S.; Soukka, T.; Vosch, T. Thulium- and erbium-doped nanoparticles with poly(acrylic acid) coating for upconversion cross-correlation spectroscopy-based sandwich immunoassays in plasma. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakland, C.; Andrews, M.; Burgess, L.; Jones, A.; Hay, S.; Harvey, P.; Natrajan, L. Expanding the scope of biomolecule monitoring with ratiometric signaling from rare-earth upconverting phosphors. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 44, 5176–5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.; Oakland, C.; Driscoll, M.D.; Hay, S.; Natrajan, L.S. Ratiometric detection of enzyme turnover and flavin reduction using rare-earth upconverting phosphors. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 5265–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattsson, L.; Wegner, K.D.; Hildebrandt, N.; Soukka, T. Upconverting nanoparticle to quantum dot FRET for homoge-neous double-nano biosensors. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 13270–13277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, S.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, B.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Yan, X.; Wang, C.; Jia, X.; et al. Photonic crystal effects on upconversion enhancement of LiErF4:0.5%Tm3+@LiYF4 for noncontact cholesterol detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnabawy, E.; Sun, D.; Shearer, N.; Shyha, I. Electro-Blown Spinning: New Insight into the Effect of Electric Field and Airflow Hybridized Forces on the Production Yield and Characteristics of Nanofiber Membranes. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Dev. 2023, 8, 100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, S.; Fang, Y.; Zheng, F.; Li, J.; He, J. Fabrication of highly oriented nanoporous fibers via airflow bub-ble-spinning. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 421, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; Shen, X.; Li, H.; Takai, O.; Saito, N. Plasma-induced synthesis of CuO nanofibers and ZnO nanoflowers in water. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2014, 34, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Mikuni, T.; Hasegawa, T. Nylon 66 nanofibers prepared by CO2 laser supersonic drawing. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 6, 40015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Su, B.; Xin, N.; Tang, J.; Xiao, J.; Luo, H.; Wei, D.; Luo, F.; Sun, J.; Fan, H. An upconversion nanoparticle-integrated fibrillar scaffold combined with a NIR-optogenetic strategy to regulate neural cell performance. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Goodge, K.; Delaney, M.; Struzyk, A.; Tansey, N.; Frey, M.A. Comprehensive review of the covalent immobi-lization of biomolecules onto electrospun nanofibers. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, Y.; Shen, W.; Ao, F. Application of blocking and immobilization of electrospun fiber in the biomedical field. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 37246–37265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohnhaas, C.; Friedemann, K.; Busko, D.; Landfester, K.; Baluschev, S.; Crespy, D.; Turshatov, A. All organic nanofibers as ultralight versatile support for triplet− triplet annihilation upconversion. ACS Macro. Lett. 2013, 2, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, M.; Ngoensawat, U.; Schenck, M.; Fenzl, C.; Wongkaew, N.; Matlock-Colangelo, L.; Hirsch, T.; Duerkop, A.; Baeummer, A.J. Embedded nanolamps in electrospun nanofibers enabling online monitoring and ratiometric measurements. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 9712–9720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghju, S.; Bari, M.R.; Khaled-Abad, M.A. Affecting parameters on fabrication of β-D-galactosidase immobilized chi-tosan/poly (vinyl alcohol) electrospun nanofibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 200, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Hernandez, C.; Zuniga, J.P.; Lozano, K.; Mao, Y. Luminescent PVDF nanocomposite films and fibers encapsulated with La2Hf2O7:Eu3+ nanoparticles. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Li, C.; Ma, P.; Li, G.; Cheng, Z.; Peng, C.; Yang, D.; Yang, P.; Lin, J. Electrospinning Preparation and Drug-Delivery Properties of an Up-conversion Luminescent Porous NaYF4:Yb3+, Er3+@Silica Fiber Nanocomposite. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 12, 2356–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yu, L.; Lu, S.; Liu, Z.; Yang, L.; Wang, T. Improved photoluminescent properties in one-dimensional LaPO4: Eu3+ nanowires. Optics. Lett. 2005, 5, 483–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heer, S.; Kömpe, K.; Güdel, H.U.; Haase, M. Highly efficient multicolour upconversion emission in transparent colloids of lanthanide-doped NaYF4 nanocrystals. Adv. Mater. 2004, 16, 2102–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Dai, Y.; Ma, P.; Zhang, X.; Kang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Lin, J. Electrospun upconversion composite fibers as dual drugs delivery system with individual release properties. Langmuir 2013, 29, 9473–9482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucky, S.S.; Idris, N.M.; Li, Z.; Huang, K.; Soo, K.C.; Zhang, Y. Titania coated upconversion nanoparticles for near-infrared light triggered photodynamic therapy. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Hao, L.-N.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, S.; Wang, W.-N.; Zhang, C.-L.; Xu, F.; Qian, H.-S. Hydrothermal-assisted crystallization for the synthesis of upconversion nanoparticles/CdS/TiO2 composite nanofibers by electrospinning. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 6013–6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Jiang, P.; Chen, B.; Sun, J.; Cheng, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, S. Electrospinning preparation and upconversion lumi-nescence of Y2Ti2O7:Tm/Yb nanofibers. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2020, 126, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Béjar, M.; Pérez-Prieto, J. Upconversion luminescent nanoparticles in physical sensing and in monitoring physical processes in biological samples. Methods Appl. Fluoresc. 2015, 3, 042002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesholler, L.M.; Genslein, C.; Schroter, A.; Hirsch, T. Plasmonic enhancement of NIR to UV upconversion by a nanoen-gineered interface consisting of NaYF4:Yb, Tm nanoparticles and a gold nanotriangle array for optical detection of vitamin B12 in serum. Analy. Chem. 2018, 90, 14247–14254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xu, W.; Teoh, C.L.; Han, S.; Kim, B.; Samanta, A.; Jun, C.; Wang, L.; Yuan, L.; Liu, X.; et al. High-efficiency in vitro and in vivo detection of Zn2+ by dye-assembled upconversion nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 2336–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Zhang, Q. Recent advances on functionalized upconversion nanoparticles for detection of small molecules and ions in biosystems. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1700609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Qiao, H.; Li, D.; Luo, L.; Chen, K.; Wei, Q. Laccase biosensor based on electrospun copper/carbon composite nanofibers for catechol detection. Sensors 2014, 14, 3543–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, K.; Ali, M.A.; Agrawal, V.V.; Malhotra, B.D.; Sharma, A. Highly sensitive biofunctionalized mesoporous electrospun TiO2 nanofiber based interface for biosensing. ACS App. Mater. Inter. 2014, 6, 2516–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowska, K.; Zdarta, J.; Grzywaczyk, A.; Kijeńska-Gawrońska, E.; Biadasz, A.; Jesionowski, T. Electrospun poly(methyl methacrylate)/polyaniline fibres as a support for laccase immobilisation and use in dye decolourisation. Environ. Res. 2020, 184, 109332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Fang, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, C. Electrospun nanofibrous membranes containing epoxy groups and hydrophilic polyethylene oxide chain for highly active and stable covalent immobilization of lipase. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 336, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, S.D.; Kayaci, F.; Uyar, T.; Timur, S.; Toppare, L. Bioactive surface design based on functional composite electrospun nanofibers for biomolecule immobilization and biosensor applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2014, 6, 5235–5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, R.; Torab, S.-F.; Naseri-Nosar, P.; Ghasempur, S.; Ranaei-Siadat, S.-O.; Khajeh, K. Electrospun polyvinyl alcohol/bovine serum albumin biocomposite membranes for horseradish peroxidase immobilization. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2016, 93, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Niu, J.; Liu, J.; Yin, L.; Xu, J. In situ encapsulation of laccase in microfibers by emulsion electrospinning: Preparation, characterization, and application. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8942–8947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zuo, J.; Zhang, L.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, L.; Liu, X.; Xue, B.; Li, Q.; Zhao, H.; et al. Accurate quan-titative sensing of intracellular pH based on self-ratiometric upconversion luminescent nanoprobe. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.; Barrio, M.; Heiland, J.; Himmelstoß, S.F.; Galban, J.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Hirsch, T. Spectrally matched upconverting luminescent nanoparticles for monitoring enzymatic reactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2014, 6, 15427–15433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Q.; Fang, A.; Wen, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, S. Rapid and highly-sensitive uric acid sensing based on enzymatic ca-talysis-induced upconversion inner filter effect. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 86, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Shan, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Ma, H.; Luo, Y.; Song, H. Assembling of functional cyclodextrin-decorated upconversion luminescence nanoplatform for cysteine-sensing. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 14054–14056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Qi, H.; Li, N.; Xie, Y.; Shao, H.; Hu, Y.; Li, D.; Ma, Q.; Liu, G.; Dong, X. Wire-in-tube nanofiber as one side to construct specific-shaped Janus nanofiber with improved upconversion luminescence and tunable magnetism. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2024, 655, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, L.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Dong, S.; Hao, J. Formation and degradation tracking of a composite hydrogel based on UCNPs@PDA. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 2430–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Ji, P.; Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Chen, S. Color-tunable luminescent macrofibers based on CdTe QDs-loaded bacterial cellulose nanofibers for pH and glucose sensing. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 254, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Pilch-Wrobel, A.; Riziotis, C.; Tanasă, E.; Krasia-Christoforou, T. Fluorescent electrospun PMMA micro-fiber mats with embedded NaYF4:Yb/Er upconverting nanoparticles. Methods Appl. Fluoresc. 2019, 7, 034002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.-C.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Shan, Z.-Q.; Feng, Z.-Q.; Li, J.-S.; Song, C.-L.; Bao, Y.-N.; Qi, X.-H.; Bong, B. A flexible and superhy-drophobic upconversion-luminescence membrane as an ultrasensitive fluorescence sensor for single droplet detection. Light. Sci. Appl. 2016, 5, 16136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, B.; Song, H.; Yu, H.; Zhang, H.; Qin, R.; Bai, X.; Pan, G.; Lu, S.; Wang, F.; Fan, L.; et al. Upconversion properties of Ln3+ doped NaYF4/polymer composite fibers prepared by electrospinning. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Xu, M.; Shi, J.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y. Highly temperature-sensitive and blue upconversion luminescence properties of Bi2Ti2O7: Tm3+/Yb3+ nanofibers by electrospinning. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 391, 123546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, X.; Pun, E.Y.B.; Lin, H. Excitation Mechanism Rearrangement in Yb3+-Introduced La2O2S: Er3+/Polyacrylonitrile Photon-Upconverted Nanofibers for Optical Temperature Sensors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 14, 13570–13581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, R.X.; Sun, K.W.; Ling, X.C.; Sun, J.W.; Chen, D.H. Upconversion red light emission and luminescence thermometry of Gd2O3:Er3+@Gd2O3:Yb 3+ core-shell nanofibers synthesized via electrospinning. Chalcogenide Lett. 2023, 7, 1841–4834. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Wu, H.; Mu, H.; Jiang, L.; Xi, W.; Xu, X.; Zheng, W. Preparation and properties of electrospun NaYF4: Yb3+, Er3+-PLGA-gelatin nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 26, 52422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.C.; Yan, J.S.; Zhu, H.; Liu, J.J.; Li, R.; Ramakrishna, S.; Long, Y.Z. Ultrasensitive and reusable upconversion-luminescence nanofibrous indicator paper for in-situ dual detection of single drop-let. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 382, 122779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Wang, Y.; Su, J.; Xin, X.; Guo, Y.; Long, Y.Z.; Ramakrishna, S. Fabrication of nanofibrous sensors by electrospinning. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2019, 62, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toncelli, A. RE-based inorganic-crystal nanofibers produced by electrospinning for photonic applications. Materials 2021, 10, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, R.; Mananquil, T.; Scenna, R.; Dennis, E.S.; Castillo-Rodriguez, J.; Koivisto, B.D. Light-Driven Energy and Charge Transfer Processes between Additives within Electrospun Nanofibres. Molecules 2023, 12, 4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Song, W.; Tang, Y.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Yu, D. Polymer-based nanofiber–nanoparticle hybrids and their medical applications. Polymers 2022, 2, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghdi, T.; Golmohammadi, H.; Yousefi, H.; Hosseinifard, M.; Kostiv, U.; Horak, D.; Merkoci, A. Chitin nanofiber paper toward optical (bio) sensing applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Int. 2020, 13, 15538–15552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Malhotra, K.; Fuku, R.; Houten, J.V.; Qu, G.Y.; Piunno, P.A.E.; Krull, U.J. Recent trends in the developments of analytical probes based on lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 139, 116256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, E.S.; Himmelstoß, S.F.; Wiesholler, L.M.; Hirsch, T.; Hall, E.A. Upconversion nanoparticles for sensing pH. Analyst 2019, 18, 5547–5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chen, G.; Ohulchanskyy, T.Y.; Kesseli, S.J.; Buchholz, S.; Li, Z.; Prasad, P.N.; Han, G. Tunable near infrared to ul-traviolet upconversion luminescence enhancement in (α-NaYF4:Yb, Tm)/CaF2 core/shell nanoparticles for in situ real-time recorded biocompatible photoactivation. Small 2013, 9, 3213–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).