Biodegradable Antibacterial Nanostructured Coatings on Polypropylene Substrates for Reduction in Hospital Infections from High-Touch Surfaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of α-Zirconium Hydrogen Phosphate Intercalated with Chlorhexidine (ZrP-CHX)

2.3. Preparation of CS- and PCL-Based Active Films

2.4. Preparation of CS- and PCL-Based Active Coatings on PP Substrates

2.5. Chemical–Physical Characterization

2.5.1. Synthesized ZrP-CHX

2.5.2. Films and Coatings

2.6. Biocompatibility Evaluation

2.6.1. Cell Cultures

2.6.2. Cytotoxicity Tests

2.6.3. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Antibacterial Activity Evaluation

3. Results

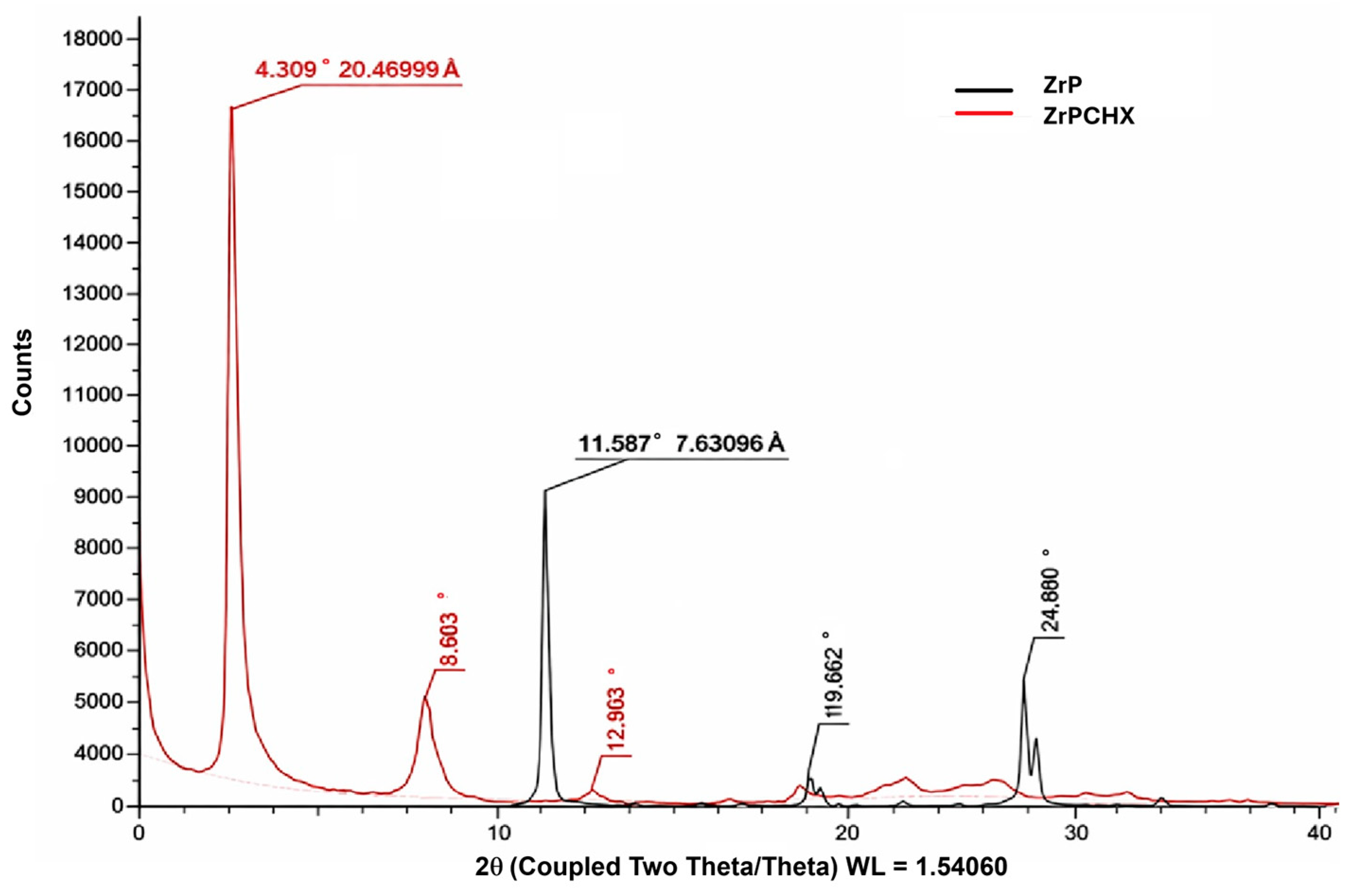

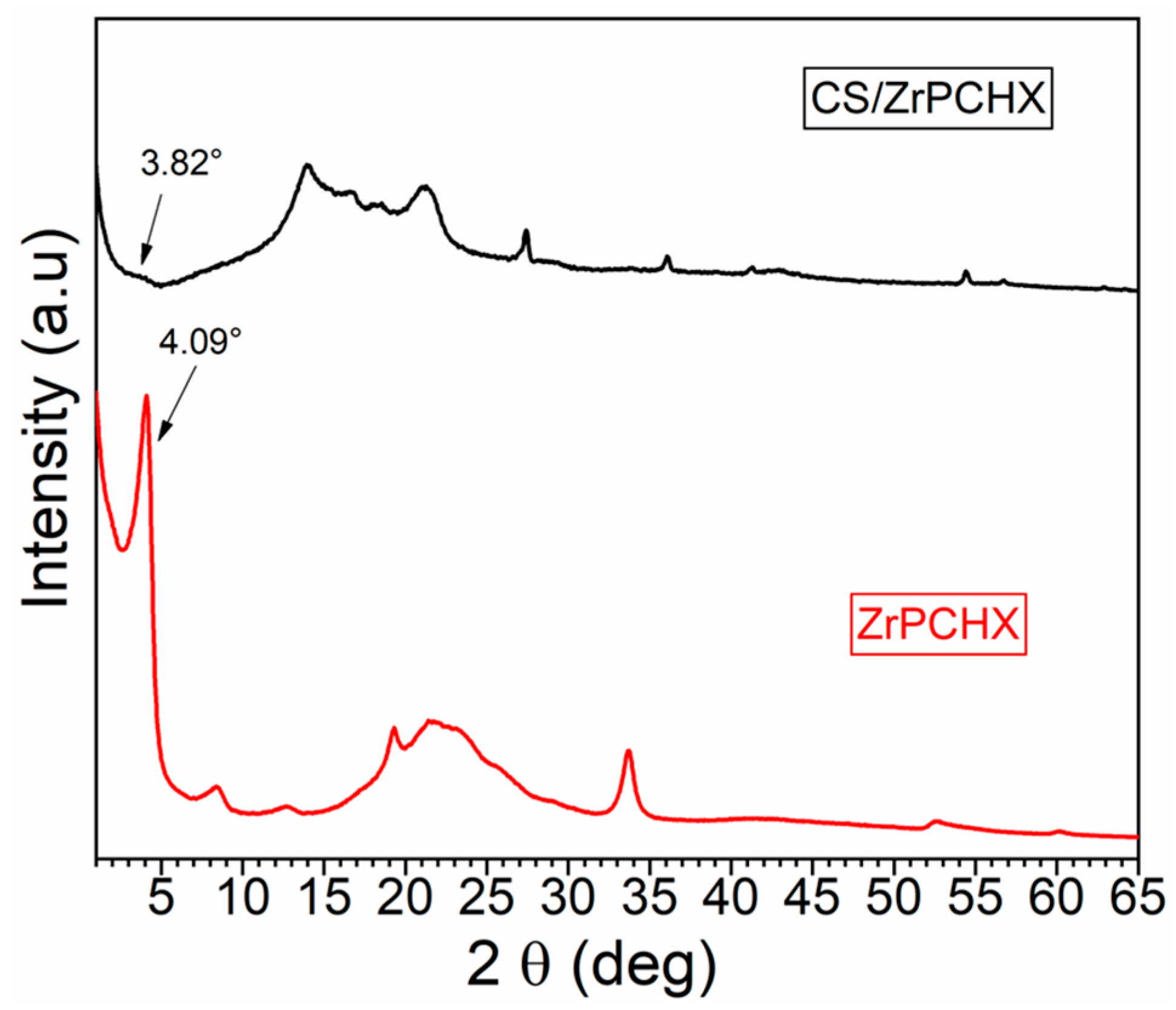

3.1. Structural Characterization of ZrPCHX Powders

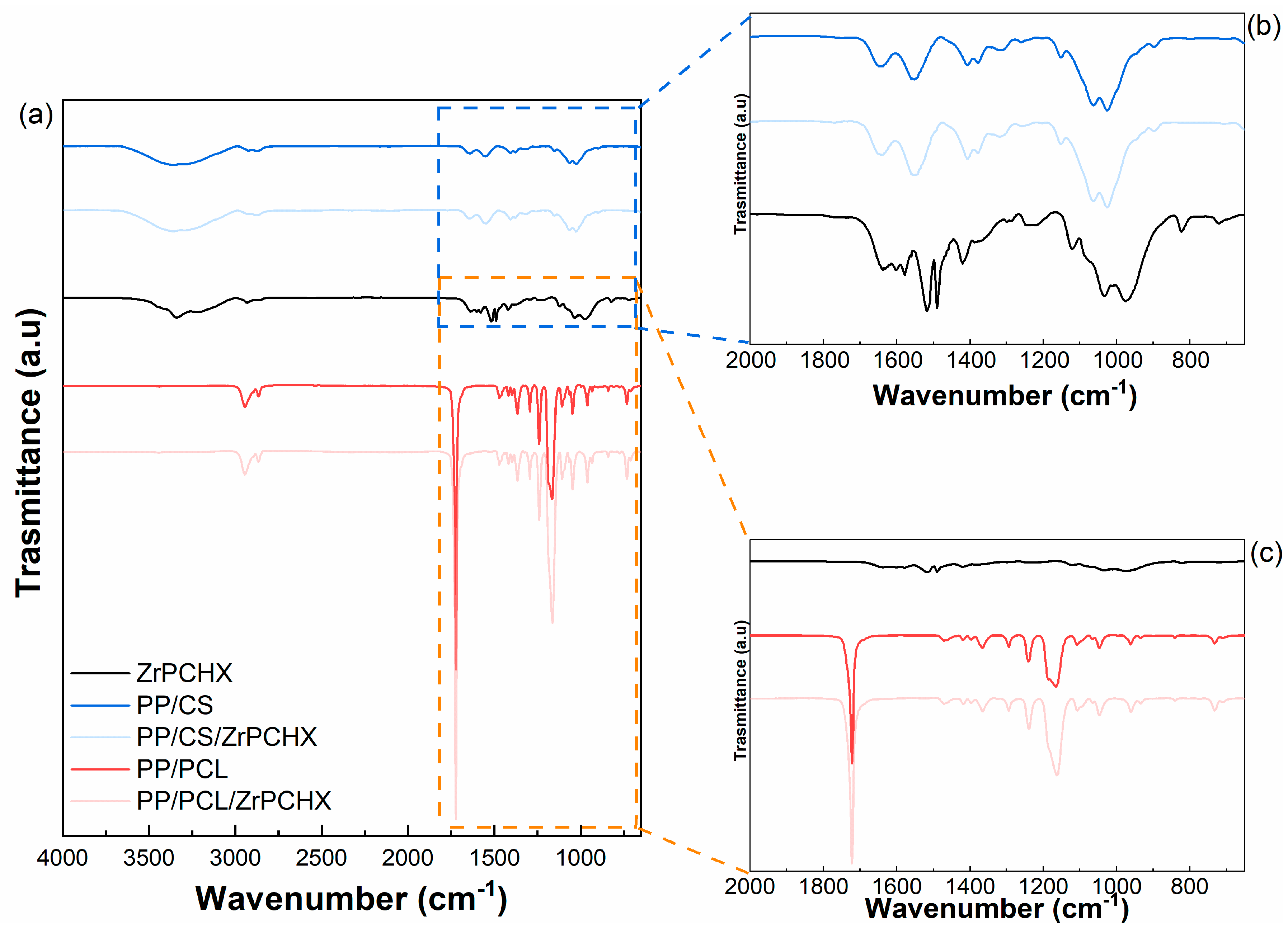

3.2. Morphological and Physicochemical Characterization of CS- and PCL-Based Films

3.3. Wettability Analysis

3.4. Coating Adhesion Tests

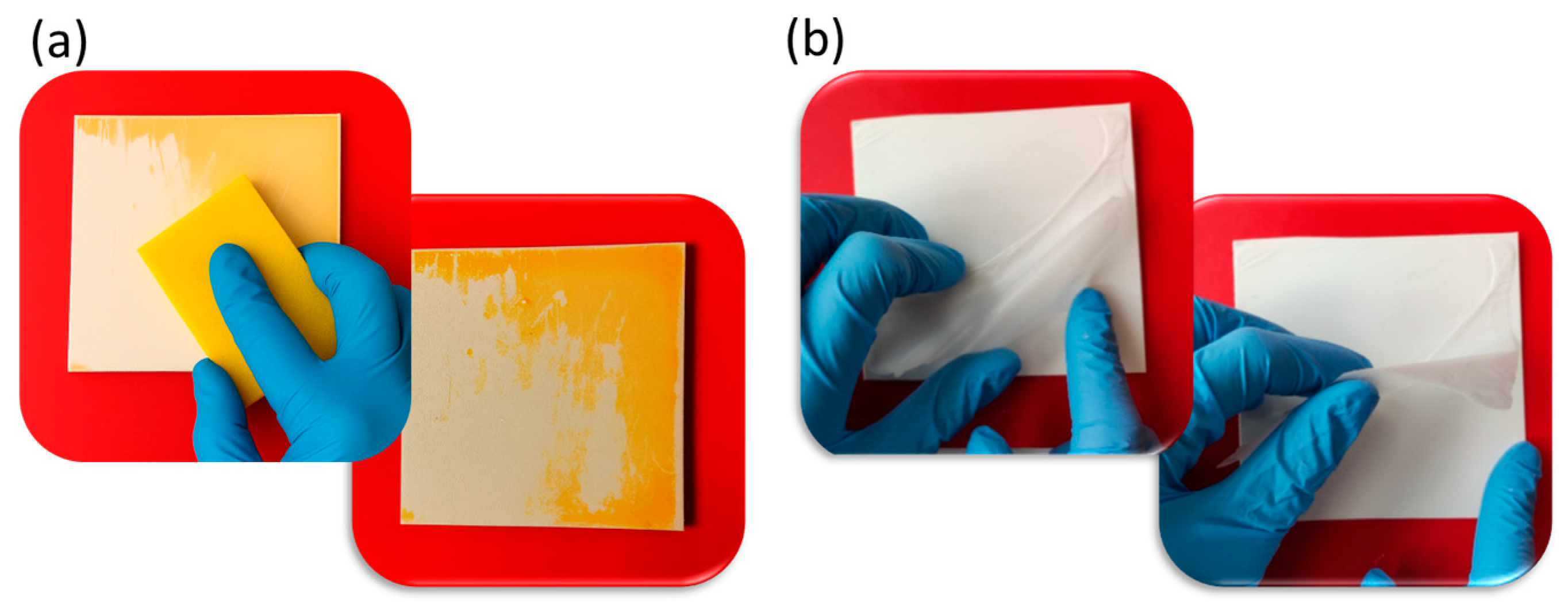

3.5. Coating Resistance to Washing/Disinfection and Removability

3.6. Biocompatibility Studies

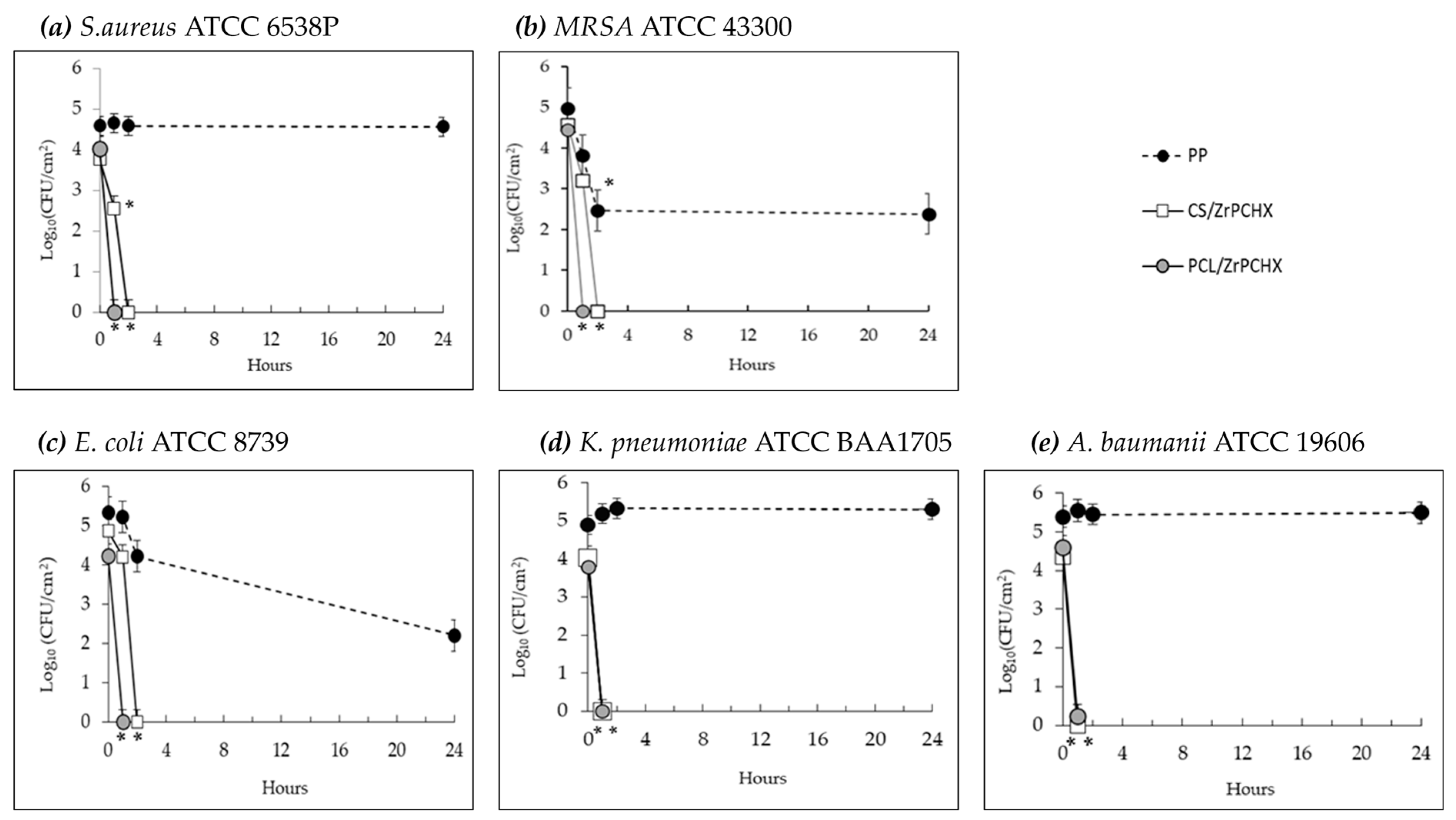

3.7. Antibacterial Activity Studies

- U0 represents the average of the common logarithm of the number of viable bacteria (CFUs/cm2) recovered from the PP specimens immediately after inoculation (T0);

- Ut indicates the average of the common logarithm of the number of viable bacteria (CFUs/cm2) recovered from the PP specimens after 24 h of incubation;

- At is the average of the common logarithm of the number of viable bacteria (CFUs/cm2) recovered from the antibacterial coating specimens after 24 h of incubation.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montero, D.A.; Arellano, C.; Pardo, M.; Vera, R.; Gálvez, R.; Cifuentes, M.; Berasain, M.A.; Gómez, M.; Ramírez, C.; Vidal, R.M. Antimicrobial Properties of a Novel Copper-Based Composite Coating with Potential for Use in Healthcare Facilities 06 Biological Sciences 0605 Microbiology. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, S.M.; Ladouceur, L.; Marshall, T.; Maclachlan, R.; Soleymani, L.; Didar, T.F. Antimicrobial Nanomaterials and Coatings: Current Mechanisms and Future Perspectives to Control the Spread of Viruses Including SARS-CoV-2. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 12341–12369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobrado, L.; Silva-Dias, A.; Azevedo, M.M.; Rodrigues, A.G. High-Touch Surfaces: Microbial Neighbours at Hand. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 2053–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichner, A.; Holzmann, T.; Eckl, D.B.; Zeman, F.; Koller, M.; Huber, M.; Pemmerl, S.; Schneider-Brachert, W.; Bäumler, W. Novel Photodynamic Coating Reduces the Bioburden on Near-Patient Surfaces Thereby Reducing the Risk for Onward Pathogen Transmission: A Field Study in Two Hospitals. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 104, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, S.; Xie, L.; Ying, Y. Conventional and Emerging Detection Techniques for Pathogenic Bacteria in Food Science: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 81, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Jiang, G.; Gao, R.; Chen, G.; Ren, Y.; Liu, J.; van der Mei, H.C.; Busscher, H.J. Circumventing Antimicrobial-Resistance and Preventing Its Development in Novel, Bacterial Infection-Control Strategies. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, I.B.; Simões, M.; Simões, L.C. Copper Surfaces in Biofilm Control. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrhar, R.; Singh, J.; Eesaee, M.; Carrière, P.; Saidi, A.; Nguyen-Tri, P. Polymeric Nanocomposites-Based Advanced Coatings for Antimicrobial and Antiviral Applications: A Comprehensive Overview. Results Surf. Interfaces 2025, 19, 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M.; Ilic, K.; Juganson, K.; Ivask, A.; Ahonen, M.; Vrček, I.V.; Kahru, A. Potential Ecotoxicological Effects of Antimicrobial Surface Coatings: A Literature Survey Backed up by Analysis of Market Reports. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkett, M.; Dover, L.; Cherian Lukose, C.; Wasy Zia, A.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Recent Advances in Metal-Based Antimicrobial Coatings for High-Touch Surfaces. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, E.; Okuthe, G.E. Silver Nanoparticle-Based Antimicrobial Coatings: Sustainable Strategies for Microbial Contamination Control. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husak, Y.; Olszaniecki, J.; Pykacz, J.; Ossowska, A.; Blacha-Grzechnik, A.; Waloszczyk, N.; Babilas, D.; Korniienko, V.; Varava, Y.; Diedkova, K.; et al. Influence of Silver Nanoparticles Addition on Antibacterial Properties of PEO Coatings Formed on Magnesium. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 654, 159387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wen, T.; Mao, F.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, X.; Zhai, C.; Zhang, H. Engineering Copper and Copper-Based Materials for a Post-Antibiotic Era. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1644362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.; Mezzadrelli, A.; Senaratne, W.; Pal, S.; Thelen, D.; Hepburn, L.; Mazumder, P.; Pruneri, V. Towards Transparent and Durable Copper-Containing Antimicrobial Surfaces. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molling, J.; Seezink, J.; Teunissen, B.; Muijrers-Chen, I.; Borm, P. Comparative Performance of a Panel of Commercially Available Antimicrobial Nanocoatings in Europe. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2014, 7, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira-Silva, P.; Borges, J.; Sampaio, P. Recent Advances in Metal-Based Antimicrobial Coatings. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 344, 103590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierascu, I.; Fierascu, I.C.; Dinu-Pirvu, C.E.; Fierascu, R.C.; Anuta, V.; Velescu, B.S.; Jinga, M.; Jinga, V. A Short Overview of Recent Developments on Antimicrobial Coatings Based on Phytosynthesized Metal Nanoparticles. Coatings 2019, 9, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.T.; Galvão, C.N.; Betancourt, Y.P.; Mathiazzi, B.I.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Microbicidal Dispersions and Coatings from Hybrid Nanoparticles of Poly (Methyl Methacrylate), Poly (Diallyl Dimethyl Ammonium) Chloride, Lipids, and Surfactants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnadio, A.; Ambrogi, V.; Pietrella, D.; Pica, M.; Sorrentino, G.; Casciola, M. Carboxymethylcellulose Films Containing Chlorhexidine-Zirconium Phosphate Nanoparticles: Antibiofilm Activity and Cytotoxicity. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 46249–46257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, B.M.; Selvan, S.T.; Narayanan, K.; Fawzy, A.S. Characterization of Chlorhexidine-Loaded Calcium-Hydroxide Microparticles as a Potential Dental Pulp-Capping Material. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Kassaee, M.; Elahi, S.H.; Bolhari, B. A Novel Binary Chlorhexidine-Chitosan Irrigant with High Permeability, and Long Lasting Synergic Antibacterial Effect. Nanochem. Res. 2018, 3, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, A.S.K.; Kumar, T.S.S.; Sanghavi, R.; Doble, M.; Ramakrishna, S. Antibacterial and Bioactive Surface Modifications of Titanium Implants by PCL/TiO2 Nanocomposite Coatings. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkaddour, A.; Jradi, K.; Robert, S.; Daneault, C. Grafting of Polycaprolactone on Oxidized Nanocelluloses by Click Chemistry. Nanomaterials 2013, 3, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Li, J.; Tang, Q.; Qiu, P.; Gou, D.; Zhao, J. Chitosan-Based Materials: An Overview of Potential Applications in Food Packaging. Foods 2022, 11, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.T.; Alam, M.N.-E.; Khan, M.N. Water-Borne Chitosan/CuO-GO Nanocomposite as an Antibacterial Coating for Functional Leather with Enhanced Mechanical and Thermal Properties. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 12162–12178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukaisho, K.; Nakayama, T.; Hagiwara, T.; Hattori, T.; Sugihara, H. Two Distinct Etiologies of Gastric Cardia Adenocarcinoma: Interactions among PH, Helicobacter Pylori, and Bile Acids. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, S.; Folliero, V.; Chianese, A.; Zannella, C.; De Filippis, A.; Rosati, L.; Prisco, M.; Falanga, A.; Mali, A.; Galdiero, M.; et al. Synthesis of Chitosan-Coated Silver Nanoparticle Bioconjugates and Their Antimicrobial Activity against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Jiang, Y.; Napiwocki, B.; Mi, H.; Peng, X.; Turng, L.S. Fabrication of Poly(ϵ-Caprolactone) Tissue Engineering Scaffolds with Fibrillated and Interconnected Pores Utilizing Microcellular Injection Molding and Polymer Leaching. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 43432–43444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrelli, D.; Mardirossian, M.; Musciacchio, L.; Pacor, M.; Berton, F.; Crosera, M.; Turco, G. Antibacterial Electrospun Polycaprolactone Membranes Coated with Polysaccharides and Silver Nanoparticles for Guided Bone and Tissue Regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 17255–17267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samokhin, Y.; Varava, Y.; Diedkova, K.; Yanko, I.; Korniienko, V.; Husak, Y.; Iatsunskyi, I.; Grebnevs, V.; Bertiņs, M.; Banasiuk, R.; et al. Electrospun Chitosan/Polylactic Acid Nanofibers with Silver Nanoparticles: Structure, Antibacterial, and Cytotoxic Properties. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 1027–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouilloux, J.; Abbad Andaloussi, S.; Langlois, V.; Dammak, L.; Renard, E. Straightforward Way to Provide Antibacterial Properties to Healthcare Textiles through N-2-Hydroxypropyltrimethylammonium Chloride Chitosan Crosslinking. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 5440–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Johnson, M.; Milne, C.; A, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, N.; Xu, Q. A Novel Hydrophilic, Antibacterial Chitosan-Based Coating Prepared by Ultrasonic Atomization Assisted LbL Assembly Technique. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabnis, S.; Block, L.H. Improved Infrared Spectroscopic Method of Analysis of Degree of N-Deacetylation of Chitosan. Polym. Bull. 1997, 39, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, T.; Sawyer, A.Y.; Hirai, T.; Schaible, S.; Sy, H.; Wickramasekara, S. Report on Investigation of ISO 10993–12 Extraction Conditions. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 131, 105164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Electrotechnical Commission. International Standard: iTeh Standard Preview; International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 2022, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, G.; Marmottini, F. Preparation of Layered α-Zirconium Phosphate with a Controlled Degree of Hydrolysis via Delamination Procedure. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1993, 157, 513–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, A.; Saxena, V.; González, J.; David, A.; Casañas, B.; Carpenter, C.; Batteas, J.D.; Colón, J.L.; Clearfield, A.; Hussain, M.D. Zirconium Phosphate Nano-Platelets: A Novel Platform for Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 1754–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, M.G.; Kamarudin, N.H.N.; Aktan, M.K.; Zheng, K.; Zayed, N.; Yongabi, D.; Wagner, P.; Teughels, W.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Braem, A. PH-Triggered Controlled Release of Chlorhexidine Using Chitosan-Coated Titanium Silica Composite for Dental Infection Prevention. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, D.; Borges, P.; Grainha, T.; Rodrigues, C.F.; Pereira, M.O. Tailoring the Immobilization and Release of Chlorhexidine Using Dopamine Chemistry to Fight Infections Associated to Orthopedic Devices. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 120, 111742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaffaro, R.; Settanni, L.; Gulino, E.F. Release Profiles of Carvacrol or Chlorhexidine of PLA/Graphene Nanoplatelets Membranes Prepared Using Electrospinning and Solution Blow Spinning: A Comparative Study. Molecules 2023, 28, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, O.; Acevedo, M.; Vélaz, I. Study of PVP and PLA Systems and Fibers Obtained by Solution Blow Spinning for Chlorhexidine Release. Polymers 2025, 17, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamsai, B.; Soodvilai, S.; Opanasopit, P.; Samprasit, W. Topical Film-Forming Chlorhexidine Gluconate Sprays for Antiseptic Application. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, G.; Anusree, V.S.; Ravi, P.; Vedanayagam, S.; Doble, M. LDPE/PCL Nanofibers Embedded Chlorhexidine Diacetate for Potential Antimicrobial Applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 107652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyamani, A.A.; Al-Musawi, M.H.; Albukhaty, S.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Ibrahim, K.M.; Ahmed, E.M.; Jabir, M.S.; Al-Karagoly, H.; Aljahmany, A.A.; Mohammed, M.K.A. Electrospun Polycaprolactone/Chitosan Nanofibers Containing Cordia Myxa Fruit Extract as Potential Biocompatible Antibacterial Wound Dressings. Molecules 2023, 28, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayebi, T.; Baradaran-Rafii, A.; Hajifathali, A.; Rahimpour, A.; Zali, H.; Shaabani, A.; Niknejad, H. Biofabrication of Chitosan/Chitosan Nanoparticles/Polycaprolactone Transparent Membrane for Corneal Endothelial Tissue Engineering. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sati, H.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Hansen, P.; Garlasco, J.; Campagnaro, E.; Boccia, S.; Castillo-Polo, J.A.; Magrini, E.; Garcia-Vello, P.; et al. The WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: A Prioritisation Study to Guide Research, Development, and Public Health Strategies against Antimicrobial Resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Arias, C.A. ESKAPE Pathogens: Antimicrobial Resistance, Epidemiology, Clinical Impact and Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontecha-Umaña, F.; Ríos-Castillo, A.G.; Ripolles-Avila, C.; Rodríguez-Jerez, J.J. Antimicrobial Activity and Prevention of Bacterial Biofilm Formation of Silver and Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle-Containing Polyester Surfaces at Various Concentrations for Use. Foods 2020, 9, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kuk, E.; Yu, K.N.; Kim, J.-H.; Park, S.J.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, S.H.; Park, Y.K.; Park, Y.H.; Hwang, C.-Y.; et al. Antimicrobial Effects of Silver Nanoparticles. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2007, 3, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.F. Microbiology of Pressure-Treated Foods. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 98, 1400–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Castillo, A.G.; Umaña, F.F.; Rodríguez-Jerez, J.J. Long-Term Antibacterial Efficacy of Disinfectants Based on Benzalkonium Chloride and Sodium Hypochlorite Tested on Surfaces against Resistant Gram-Positive Bacteria. Food Control 2018, 93, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

─) antibacterial films. Each point indicates the mean number of viable colonies per group of isolates. The number of bacteria was quantified immediately after inoculation and after 1, 2, and 24 h of incubation compared to the control (PP). Mean value of at least 3 experiments ± SD is presented. Differences with respect to controls were defined as statistically significant at p * < 0.01.

─) antibacterial films. Each point indicates the mean number of viable colonies per group of isolates. The number of bacteria was quantified immediately after inoculation and after 1, 2, and 24 h of incubation compared to the control (PP). Mean value of at least 3 experiments ± SD is presented. Differences with respect to controls were defined as statistically significant at p * < 0.01.

─) antibacterial films. Each point indicates the mean number of viable colonies per group of isolates. The number of bacteria was quantified immediately after inoculation and after 1, 2, and 24 h of incubation compared to the control (PP). Mean value of at least 3 experiments ± SD is presented. Differences with respect to controls were defined as statistically significant at p * < 0.01.

─) antibacterial films. Each point indicates the mean number of viable colonies per group of isolates. The number of bacteria was quantified immediately after inoculation and after 1, 2, and 24 h of incubation compared to the control (PP). Mean value of at least 3 experiments ± SD is presented. Differences with respect to controls were defined as statistically significant at p * < 0.01.

| Bacterial Strains | PCL/ZrPCHX | CS/ZrPCHX |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus, ATCC® 6538P | R = 4.02 (1 h) | R = 3.88 (2 h) |

| MRSA, ATCC® 43300 | R = 3.82 (1 h) | R = 2.47 (2 h) |

| E. coli, ATCC® 8739 | R = 5.00 (1 h) | R = 4.21 (2 h) |

| K. pneumoniae, ATCC® BAA-1705 | R = 4.98 (1 h) | R = 2.93 (1 h) |

| A. baumanii, ATCC® 19606 | R = 4.60 (1 h) | R = 4.36 (1 h) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stanzione, M.; Improta, I.; Raucci, M.G.; Soriente, A.; Lavorgna, M.; Buonocore, G.G.; Spogli, R.; Marcelloni, A.M.; Proietto, A.R.; Amori, I.; et al. Biodegradable Antibacterial Nanostructured Coatings on Polypropylene Substrates for Reduction in Hospital Infections from High-Touch Surfaces. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020080

Stanzione M, Improta I, Raucci MG, Soriente A, Lavorgna M, Buonocore GG, Spogli R, Marcelloni AM, Proietto AR, Amori I, et al. Biodegradable Antibacterial Nanostructured Coatings on Polypropylene Substrates for Reduction in Hospital Infections from High-Touch Surfaces. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(2):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020080

Chicago/Turabian StyleStanzione, Mariamelia, Ilaria Improta, Maria Grazia Raucci, Alessandra Soriente, Marino Lavorgna, Giovanna Giuliana Buonocore, Roberto Spogli, Anna Maria Marcelloni, Anna Rita Proietto, Ilaria Amori, and et al. 2026. "Biodegradable Antibacterial Nanostructured Coatings on Polypropylene Substrates for Reduction in Hospital Infections from High-Touch Surfaces" Nanomaterials 16, no. 2: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020080

APA StyleStanzione, M., Improta, I., Raucci, M. G., Soriente, A., Lavorgna, M., Buonocore, G. G., Spogli, R., Marcelloni, A. M., Proietto, A. R., Amori, I., & Mansi, A. (2026). Biodegradable Antibacterial Nanostructured Coatings on Polypropylene Substrates for Reduction in Hospital Infections from High-Touch Surfaces. Nanomaterials, 16(2), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020080