Abstract

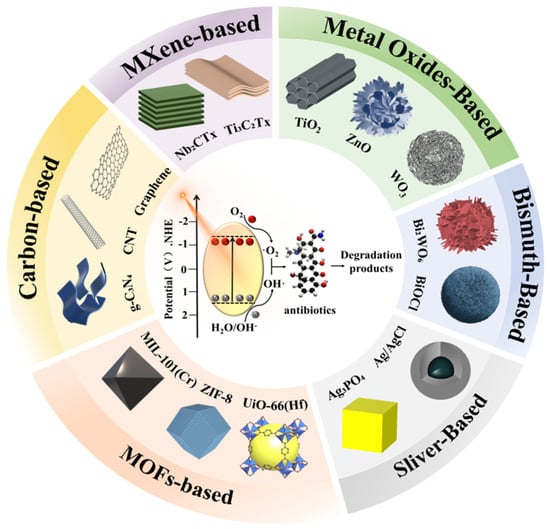

Widespread antibiotic residues in aquatic environments pose escalating threats to ecological stability and human health, highlighting the urgent demand for effective remediation strategies. In recent years, photocatalytic technology based on advanced nanomaterials has emerged as a sustainable and efficient strategy for antibiotic degradation, enabling the effective utilization of solar energy for environmental remediation. This review provides an in-depth discussion of six representative categories of photocatalytic nanomaterials that have demonstrated remarkable performance in antibiotic degradation, including metal oxide-based systems with defect engineering and hollow architectures, bismuth-based semiconductors with narrow band gaps and heterojunction designs, silver-based plasmonic composites with enhanced light harvesting, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) featuring tunable porosity and hybrid interfaces, carbon-based materials such as g-C3N4 and biochar that facilitate charge transfer and adsorption, and emerging MXene–semiconductor hybrids exhibiting exceptional conductivity and interfacial activity. The photocatalytic performance of these nanomaterials is compared in terms of degradation efficiency, recyclability, and visible-light response to evaluate their suitability for antibiotic degradation. Beyond parent compound removal, we emphasize transformation products, mineralization, and post-treatment toxicity evolution as critical metrics for assessing true detoxification and environmental risk. In addition, the incorporation of artificial intelligence into photocatalyst design, mechanistic modeling, and process optimization is highlighted as a promising direction for accelerating material innovation and advancing toward scalable, safe, and sustainable photocatalytic applications.

1. Introduction

The ubiquitous presence of antibiotics in aquatic environments has emerged as a pressing global environmental challenge, threatening both ecological balance and human health [1]. Designed to combat bacterial infections, these pharmaceutical compounds are increasingly detected in surface water, groundwater, and even drinking water, largely because conventional wastewater treatment processes exhibit limited ability to fully remove them [2]. Their continuous discharge into the environment promotes the development and proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes, thereby diminishing the efficacy of antibiotic therapies and constituting a serious public health crisis. Furthermore, even at low concentrations, antibiotics can exert toxic effects on non-target aquatic organisms and pose potential risks to human health through chronic exposure [3]. Thus, there is an urgent need for effective and sustainable technologies to eliminate or degrade antibiotics from contaminated water sources [4,5].

Traditional water treatment methods, such as physical adsorption, flocculation, and chemical oxidation, face inherent limitations, including incomplete removal, generation of toxic byproducts, high energy demand, and the production of secondary waste requiring further treatment [6]. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), which involve the generation of highly reactive species such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide radicals (), have shown great potential for degrading persistent organic pollutants, including antibiotics [7]. Among these processes, heterogeneous photocatalysis stands out for its ability to utilize solar or artificial light to convert pollutants into less harmful substances, mainly carbon dioxide and water, with the added benefits of low cost, high efficiency, and minimal secondary pollution [8]. It is well established that the efficiency of photocatalysis is heavily dependent on the properties of the photocatalyst, especially its capacity to absorb light, generate electron–hole pairs, and facilitate charge separation and transfer to react with adsorbed pollutants and water/oxygen to form reactive oxygen species (ROS) [9]. In this context, nanomaterials, with their large surface areas, unique electronic band structures, and quantum size effects, have emerged as highly promising candidates in the design of efficient photocatalysts for environmental remediation [10].

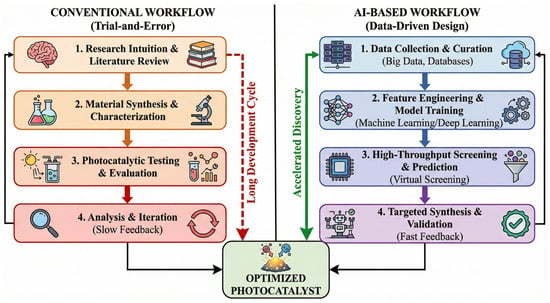

Recent advances in nanotechnology have facilitated the design and fabrication of a wide range of nanomaterial-based photocatalysts, such as metal oxides, bismuth-based semiconductors, silver-based composites, MOFs, carbon-based materials, and emerging MXene hybrids [4,11,12]. However, while existing reviews have extensively documented the synthesis and laboratory-scale efficiency of these materials, a critical gap remains in bridging the disconnect between fundamental material design and practical environmental application. Most current literature tends to focus heavily on degradation rates in ultrapure water, often overlooking the complexity of real-world water matrices (e.g., pH variability, coexisting ions, and natural organic matter) that drastically influence catalyst performance and stability. Furthermore, the potential formation of intermediate byproducts that may be more toxic than the parent antibiotics is frequently under-addressed, necessitating a shift from simple “pollutant removal” to comprehensive “toxicity elimination”. Moreover, the rapid emergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI) offers a transformative opportunity to overcome the trial-and-error limitations of traditional catalyst development. Unlike previous reviews that treat AI as a disconnected or supplementary topic, this review posits AI as a central pillar for the future of photocatalysis, from accelerating material screening and predicting structure-activity relationships to optimizing complex reactor parameters.

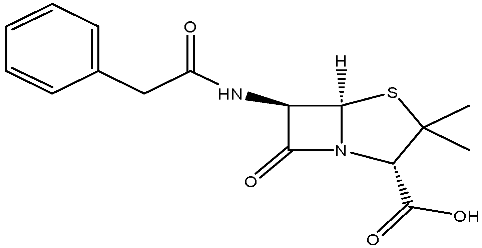

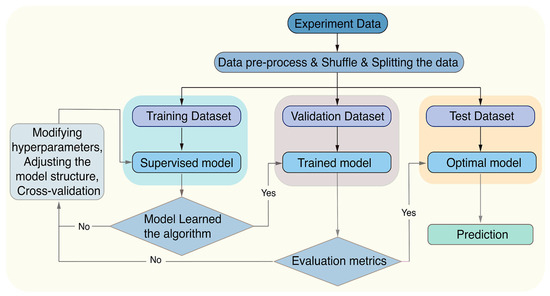

Therefore, this review provides a comprehensive and critical analysis of state-of-the-art photocatalytic nanomaterials, distinguishing itself by integrating three key dimensions: (i) A systematic evaluation of six major classes of photocatalysts (Figure 1), focusing on how specific nanostructures (e.g., defects, heterojunctions) drive performance; (ii) An in-depth discussion on the challenges of scalability, matrix effects, and toxicity evolution, emphasizing the gap between laboratory proof-of-concept and real-world detoxification; and (iii) A holistic perspective on AI-driven strategies that are reshaping the roadmap for discovering next-generation photocatalysts. By connecting material engineering with environmental toxicity assessment and data-driven science, this review aims to provide a clear pathway toward scalable, safe, and sustainable photocatalytic water treatment technologies.

Figure 1.

Overview of advanced photocatalytic nanomaterials for antibiotic degradation.

2. Antibiotics in Aquatic Systems: Physicochemical Characteristics, Transformation, and Ecological Risks

2.1. Chemical Structure and Physicochemical Properties of Antibiotics

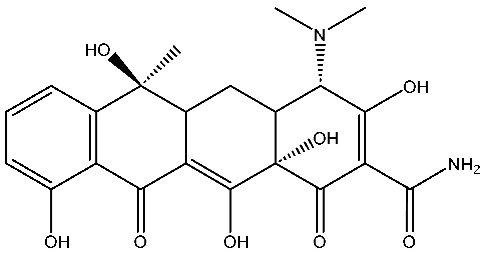

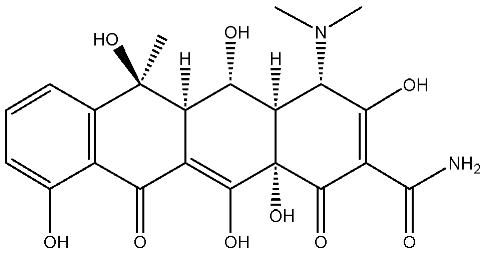

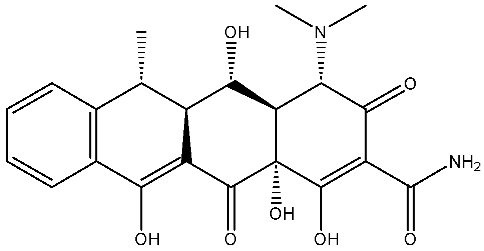

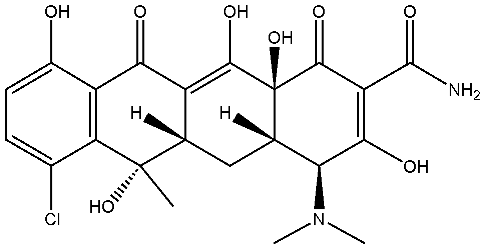

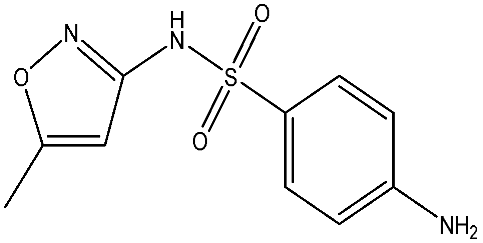

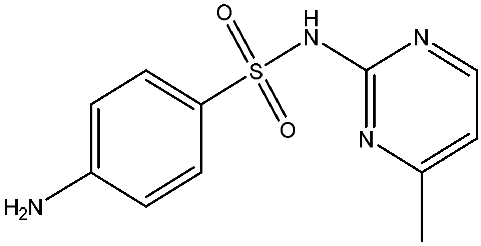

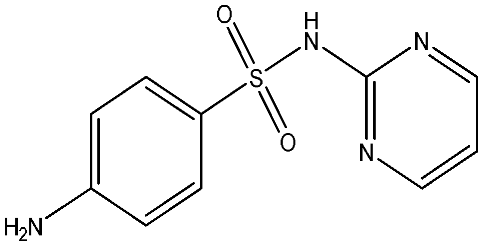

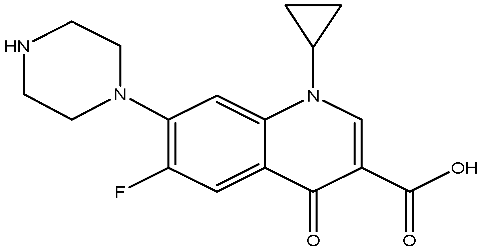

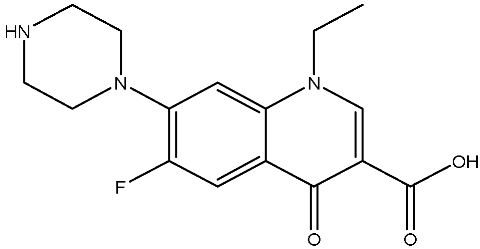

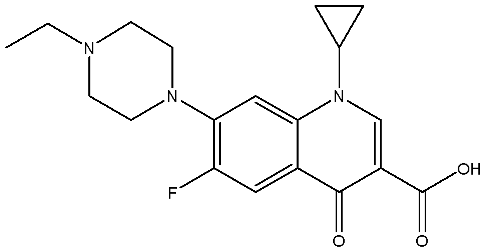

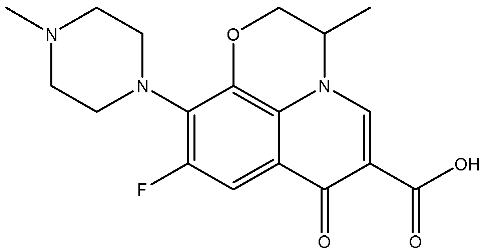

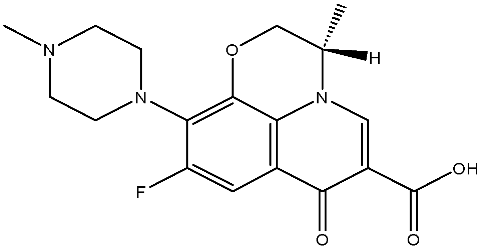

As emerging contaminants, antibiotics exert adverse effects that extend beyond their clinical application in humans and animals to impact ecosystems. Based on differences in chemical structures and characteristics, antibiotics are mainly classified into β-lactams (e.g., penicillin, cephalosporins), tetracyclines (e.g., tetracycline (TC), doxycycline), fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin (CIP), norfloxacin (NOR)), and sulfonamides [13]. While these antibiotics can kill or inhibit pathogenic microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi in human and animal hosts, their use may also lead to side effects, such as persistent toxicity to aquatic organisms, allergic reactions, and even organ damage in humans [14]. However, from a photocatalytic perspective, the significance of these classifications lies not just in their biological activity, but in their specific structure-activity relationships that dictate degradation efficiency. The molecular structure determines both the “anchoring groups” required for catalyst adsorption and the “reactive sites” susceptible to radical attack.

The structural diversity of antibiotics directly governs their environmental behavior. Tetracyclines, characterized by a four-ring system containing hydroxyl, keto, and dimethylamino groups, exhibit strong adsorption onto biochar and metal oxides due to their hydrophilicity and ability to form hydrogen bonds [15]. Crucially, the keto-enol functional groups in TCs can act as ligands to form inner-sphere surface complexes with metal sites via ligand-to-metal charge transfer. This specific interaction significantly lowers the activation energy for interfacial electron transfer, often serving as a primary pathway for direct hole (h+) oxidation. Furthermore, the high electron density of the phenolic ring makes it a preferential target for electrophilic attack by •OH [16]. In contrast, fluoroquinolones, with their aromatic quinolone core and carboxyl groups, preferentially adsorb onto hydrophobic materials such as sludge-derived biochar [17]. Recent theoretical calculations indicate that the piperazine ring in FQs usually possesses the highest Fukui index, making it the most fragile site for oxidative cleavage during photocatalysis [18]. However, structural modifications, such as halogenation at the C-8 position (e.g., lomefloxacin), can prolong environmental persistence by resisting enzymatic and photolytic breakdown [19]. The zwitterionic nature of certain FQs (e.g., CIP) further complicates removal, as it allows dual interactions with both hydrophilic and hydrophobic matrices depending on the solution pH. Regarding other classes, it is understood that β-lactams are rapidly degraded through hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring under neutral or alkaline conditions; however, derivatives with bulky substituents (e.g., third-generation tetracyclines like tigecycline) exhibit enhanced resistance to degradation. In photocatalytic systems, the cleavage of the strained β-lactam ring is often accelerated by attack. Sulfonamides, which harbor sulfonamide (-SO2NH2) and aromatic amine groups, typically exhibit moderate persistence; while the S-N bond is vulnerable to attack, their degradation intermediates may still retain antimicrobial activity, necessitating deep mineralization to ensure detoxification.

Most antibiotics possess stable physicochemical properties, such as acidity, alkalinity, and electrostatic properties, which are determined by their molecular composition. Antibiotics are typically ionic polar organic compounds containing functional groups like hydroxyl (-OH), amine (-NR3+), and carboxyl (-COOH), along with their corresponding acid dissociation constants (pKa). Depending on the pH conditions, antibiotics can exist in various forms including cationic, amphoteric, neutral, or anionic forms [20]. This speciation is critical for the “electrostatic gatekeeping” effect in photocatalysis. It has been established that dissociation sites change at different pH values: when pH ≤ pKa1, the antibiotic exists as a cation, enabling adsorption onto negatively charged surfaces via electrostatic attraction. Conversely, when the pH exceeds the Point of Zero Charge of the photocatalyst and the pKa of the antibiotic, electrostatic repulsion hinders the approach of pollutant molecules to the active sites, thereby suppressing the reaction rate [21]. Thus, the pH of the solution plays a significant role in affecting not only the generation of ROS and dissociation of surface charges but also the protonation state of antibiotic molecules The basic properties of antibiotics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physical and chemical properties of principal classes of antibiotics.

2.2. Transformation Products, Detoxification, and Environmental Risk

In photocatalytic antibiotic removal, it is increasingly recognized that “disappearance of the parent molecule” does not necessarily equate to detoxification, because partial oxidation often yields transformation products (TPs) that can retain bioactivity or even exhibit higher ecotoxicity than the pristine antibiotic. Therefore, an environmentally meaningful assessment should couple kinetic removal with mechanistic elucidation of TP formation (e.g., hydroxylation, dealkylation, ring-opening, and defluorination pathways) and a clear accounting of mineralization (TOC/COD) rather than relying solely on C/C0. For example, detailed TP identification during antibiotic phototransformation has been performed by combining kinetics with intermediate tracking, enabling a more defensible discussion of pathway reliability and controlling factors such as water matrix components and catalyst surface chemistry [22,23]. Importantly, TP analysis should be integrated with bioassays to verify true detoxification, because post-treatment solutions may contain reactive aromatic intermediates and short-chain oxygenates whose health and ecological impacts are not captured by routine concentration-based metrics. Evidence from pharmaceutical photodegradation illustrates this “double-edged” nature of photocatalysis: acetaminophen can yield intermediates that are potentially valorisable (e.g., 1,2,4-benzenetriol) under certain photocatalytic systems [24,25,26], yet hazardous intermediates such as p-nitrophenol have also been detected depending on catalyst and irradiation conditions, underscoring that pathway steering is central to risk control [27]. Beyond TP-derived risks, the catalyst itself may introduce environmental burdens via photo/chemical corrosion and consequent leaching of metal ions or nanoscale fragments; such “nanotoxicity” concerns motivate the use of greener synthesis, protective surface coatings, and rigorous post-reaction characterization to ensure that improved reactivity does not trade off against stability and safety [28,29]. Collectively, a robust “TP–detoxification–risk” narrative should explicitly link (i) TP fingerprints and dominant pathways, (ii) mineralization and detoxification endpoints, and (iii) catalyst stability/leaching, so that photocatalysis is evaluated not only for antibiotic degradation, but also for verified risk reduction in realistic water-treatment contexts.

3. Principle and Fundamental Mechanism of Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics

AOPs have emerged as an innovative solution for wastewater purification, characterized by mild conditions, exceptional degradation performance, and reliable process stability. These systems leverage diverse mechanisms such as electromagnetic wave-assisted decomposition (ultrasound/microwave), acoustic cavitation, ozone-based oxidation, low-temperature plasma techniques, iron-catalyzed redox processes (Fenton variants), electrochemical treatments, and light-driven catalytic reactions to produce reactive intermediates, including •OH, , and electron vacancies (h+) [30]. These oxidizing agents possess robust redox potential capable of mineralizing recalcitrant organic compounds through combined oxidation-reduction pathways. Photocatalytic processes are characterized by a high degree of mineralization efficiency, achieving comprehensive degradation via radical-mediated chain reactions [31]. This green technology demonstrates environmental compatibility, cost-effectiveness, and operational simplicity, holding significant potential for application in the elimination of antibiotic compounds from water. However, it should be emphasized that the apparent removal of antibiotics does not necessarily indicate complete mineralization, as partial oxidation may lead to the formation of transformation products with altered environmental behavior and biological effects.

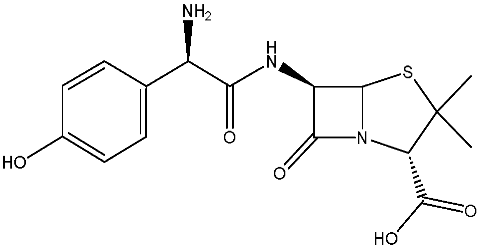

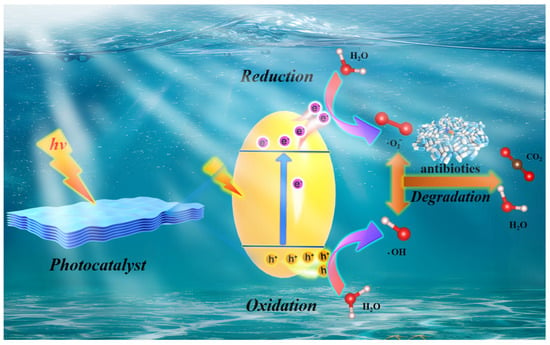

Photocatalytic reactions are now understood to occur in three main stages. Initially, when the energy of light (including ultraviolet, visible, and infrared light) meets or exceeds the semiconductor bandgap (Eg), electrons in the photocatalytic material are excited from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), forming photogenerated electrons (e−), which possess reducing properties. Corresponding photogenerated holes (h+) with oxidizing abilities are created in the VB. At this point, a highly active photogenerated electron–hole pair, interconnected by Coulomb forces, is formed in the semiconductor [32]. Due to the discontinuity in the semiconductor’s energy bands, these photogenerated electron–hole pairs separate under the influence of an electric field and diffuse toward the surface of the semiconductor. However, not all diffused electrons and holes will participate in the catalytic reaction. Due to their short lifespans, photogenerated electrons and holes are prone to recombination through diffusion, a process known as bulk recombination. Even if they reach the semiconductor surface, surface recombination may occur due to their mutual attraction [33]. Finally, electrons and holes that successfully reach the surface react with various compounds through redox reactions. At the catalyst surface, electrons may reduce O2 to produce , or further react to form •OH. Holes can react with OH− in water or oxidize adsorbed hydroxyl groups on the catalyst surface, also generating •OH [34]. Due to the potent oxidative activity of holes and •OH radicals, and to a lesser extent, radicals, these species can chemically interact with the target pollutants, producing intermediate products that contribute to the degradation of pollutants. Because these processes occur competitively and simultaneously, the relative contribution of different reactive species strongly depends on band-edge positions, surface chemistry, defect states, and solution conditions such as pH and dissolved oxygen. Figure 2 illustrates the mechanism of photocatalytic degradation of pollutants.

Figure 2.

The general photocatalytic mechanism of antibiotic degradation by photocatalysts.

Research has established that, in photocatalytic decomposition systems, the principal oxidizing agents responsible for contaminant transformation are light-induced h+ and •OH formed through valence band charge carriers interacting with surface-bound hydroxyl groups or water molecules [35]. While participate in the reaction network, their contribution is less pronounced due to diminished oxidative capacity. The degradation mechanism is formalized through a series of chemical Equations (1)–(5), delineating the sequential electron transfer processes and radical-mediated breakdown pathways.

Semiconductor + hν → e− + h

h+ + OH− → •OH

The primary goal involves converting hazardous contaminants into benign substances while pursuing complete transformation into inorganic constituents (such as carbon dioxide, water, and mineral salts) when technologically feasible. Critical technical challenges include suppressing both bulk-phase electron–hole pair annihilation and interfacial charge recombination phenomena. Nanomaterials, by virtue of their unique physicochemical properties, offer robust solutions to these challenges. Their high specific surface area provides abundant active sites and enhances pollutant adsorption. Quantum size effects and tailorable electronic band structures enable the modulation of bandgap energies for improved visible-light utilization [36]. Furthermore, nanoscale dimensions facilitate shorter charge migration distances to the surface, reducing bulk recombination losses. Engineered nanostructures (e.g., hollow spheres, heterojunctions, defect engineering) can further optimize light harvesting, charge separation dynamics, and interfacial reactions [37]. Therefore, the rational design and engineering of advanced photocatalytic nanomaterials have emerged as the central strategy to enhance the efficiency and applicability of photocatalytic antibiotic degradation.

4. Key Photocatalytic Nanomaterials Used in Antibiotic Degradation

4.1. Metal Oxide-Based Photocatalysts

Metal oxide-based photocatalysts are widely employed alone or in combination with other materials to accelerate the degradation of organic pollutants such as insecticides, dyes, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [38]. The past decade has witnessed a burgeoning interest in leveraging metal oxide-containing photocatalysts specifically for the degradation of antibiotics. These materials effectively absorb both visible (Vis) and ultraviolet (UV) light and exhibit high biocompatibility, safety, and stability under various environmental conditions. However, their practical application is hindered by their wide bandgap and the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs, which limits the formation of strong oxidizing species such as •OH, , and singlet oxygen (1O2) under light irradiation [39]. Therefore, strategic modifications or the development of composite systems is essential to improve electron–hole separation and fully realize their photocatalytic potential.

In recent years, spherical metal oxides have been widely employed as efficient heterogeneous photocatalysts for antibiotic degradation, owing to their distinctive features such as high specific surface area, excellent permeability, and pronounced porosity. In a study by Ding et al. [40], who fabricated a hollow-spherical CuFe2O4 catalyst enriched with oxygen vacancies (HS-CuFe2O4-σ) via a one-step hydrothermal approach for heterogeneous Fenton-like degradation of CIP. The hollow architecture provides a larger accessible surface and facilitates mass transport, while oxygen vacancies act as key redox-active sites that promote electron transfer and accelerate H2O2 activation toward radical generation. Notably, HS-CuFe2O4-σ achieved complete CIP removal within 30 min over a relatively broad pH window (6.5–9.0), and the apparent rate constant at neutral pH was markedly enhanced compared with pristine CuFe2O4. Beyond demonstrating high removal efficiency, this work also highlights an important design principle for metal oxides in antibiotic treatment: vacancy-rich surfaces and nanoconfined hollow structures can cooperatively lower activation barriers for oxidant activation and pollutant oxidation, thereby mitigating the pH sensitivity that commonly restricts Fenton-like systems. In addition, Xu et al. [41] synthesized a Z-scheme Cu2O/Bi/Bi2MoO6 heterojunction featuring Bi-decorated hollow microflower spheres. This material leveraged surface plasmon resonance (SPR) from Bi nanoparticles to simultaneously oxidize sulfadiazine and reduce Ni (II), while the hollow structure enhanced light harvesting and localized electric fields. The Z-scheme configuration further promoted charge separation. Besides vacancy engineering, multicomponent oxide assemblies have been developed to extend solar responsiveness and strengthen interfacial charge utilization. Zhang et al. [42] prepared SiO2@Fe2O3@TiO2 hollow spheres (SFT) using an SiO2 template strategy, where ultrafine Fe2O3 domains are integrated with TiO2 to promote charge separation and surface redox reactions. Importantly, SFT was evaluated under natural sunlight in addition to simulated irradiation, which better reflects practical solar-driven scenarios. Under sunny conditions, TC could be completely decomposed within 80 min, and near-complete TC degradation was still achieved under cloudy weather after extended irradiation; ENR was also rapidly removed (complete degradation reported within 80 min). These findings emphasize that rationally designed oxide composites can maintain high activity under fluctuating solar intensity; however, they also imply that cross-study comparison of “rate constants” should be made cautiously, because weather, photon flux, reactor geometry, and adsorption contributions can substantially alter apparent kinetics even when the same catalyst is used.

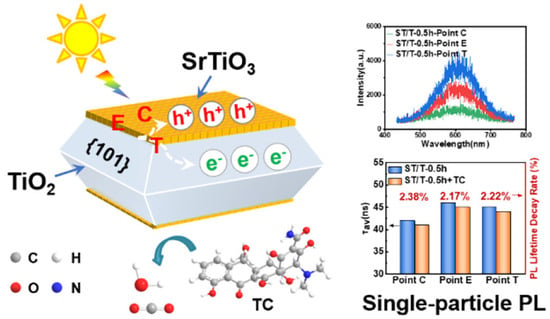

To address the inherent limitations of single-component metal oxide photocatalysts, advanced composite systems that integrate distinct functionalities have emerged as a dominant strategy for enhancing antibiotic degradation efficiency. While TiO2 remains a cornerstone material due to its superior UV-driven activity in the anatase phase, its wide bandgap (~3.2 eV) and rapid charge recombination necessitate advanced design strategies. To overcome these drawbacks, hybrid architectures combining TiO2 with carbonaceous supports or hierarchical structures have shown great promise. Abdullah et al. [43] synthesized activated carbon-TiO2 composites (ACT-X) via hydrothermal methods. Among these, the ACT-4 photocatalyst demonstrated the highest photocatalytic degradation (99.6%) of ceftriaxone sodium through synergistic adsorption–photocatalysis. The conductive carbon matrix enhanced visible-light absorption and suppressed electron–hole recombination, showcasing the efficacy of hybrid designs. To bridge performance enhancement with mechanistic and application-oriented outcomes, single-atom or quasi-atomic cocatalyst strategies have recently been introduced into oxide photocatalysis. Wang et al. [44] constructed a biochar-supported single-atom iron cocatalyst coupled with anatase TiO2 (SA-Fe@TiO2), in which isolated Fe sites are anchored on nitrogen-doped biochar and interfaced with TiO2 This architecture was shown to facilitate charge-carrier separation/transfer and to increase the apparent rate constant for SMX degradation by 4.3 times relative to TiO2, while also exhibiting an enhanced capacity for inactivating antibiotic-resistance-related genetic risks. Beyond pollutant disappearance, the authors further considered mineralization and broader applicability: substantial TOC elimination was reported during SMX treatment, and immobilized SA-Fe@TiO2 films enabled rapid degradation of multiple antibiotics (five distinct antibiotics degraded within 20 min), highlighting a pathway toward more deployable systems. Such results are highly relevant to the recurring concern in antibiotic photocatalysis that “degradation” does not necessarily equal “detoxification”: catalyst designs that concurrently improve oxidation capacity and suppress harmful by-products/secondary risks (e.g., ARG propagation) should be preferentially emphasized in future evaluations. Beyond conventional ensemble measurements, single-particle spectroscopy has recently been used to elucidate charge dynamics in metal oxide heterojunctions for antibiotic degradation. Li et al. constructed a facet-selective SrTiO3/TiO2 epitaxial heterojunction, in which SrTiO3 mesocrystals are topotactically grown on the {001} facets of decahedral TiO2, enabling photogenerated electrons to migrate to the TiO2 {101} facets while holes accumulate in SrTiO3 (Figure 3). By combining this interfacial charge-transfer scheme with position-resolved PL intensity and lifetime mapping of individual particles, they showed that the epitaxial heterointerface substantially prolongs carrier lifetimes and suppresses PL decay during in situ tetracycline degradation, directly linking ordered oxide interfaces with enhanced photocatalytic performance toward antibiotics [45].

Figure 3.

Single-particle charge-transfer behavior of SrTiO3/TiO2 heterointerfaces for photocatalytic tetracycline degradation [45].

Beyond TiO2, iron-based oxides, such as α-Fe2O3 and Fe3O4, have attracted significant interest due to their visible-light absorption (bandgap 2.1–2.3 eV) and magnetic recoverability. However, their low charge separation efficiency remains a challenge. Recent advances have addressed this through composite design. In this regard, Yilmaz et al. [46] designed TiO2@ Fe3O4@C-NFs composites, where magnetic Fe3O4 nanospheres modified with TiO2 nanoparticles and carbon nanofibers achieved 80–100% degradation of antibiotics and azo dyes under UV light. The carbon nanofibers enhanced electron transfer, while Fe3O4 enabled easy magnetic separation, addressing both stability and recyclability issues.

Cerium oxide (CeO2) has attracted significant interest given its oxygen vacancy-driven redox properties. Lu et al. [47] synthesized CeO2 nanorods with abundant oxygen vacancies, which achieved 89.35% TC degradation under visible light. The vacancies acted as electron traps, prolonging carrier lifetimes and enabling efficient Ce3+/Ce4+ cycling, thereby outperforming CeO2 nanomaterials with other morphologies (such as nanocubes and nanosheets). Zinc oxide (ZnO), despite its high electron mobility, suffers from photocorrosion in aqueous environments. Recent studies have integrated ZnO with carbon-based materials to enhance its stability. For instance, Roy et al. [48] synthesized ferrocene-functionalized rGO-ZnO nanocomposites, achieving >95% removal of CIP and SMX. The rGO framework provided conductive pathways for charge separation, while its 3D structure enhanced light absorption, demonstrating the versatility of metal oxide-carbon hybrids in improving both stability and performance. Another effective route is to couple metal oxides with carbonaceous components and engineer built-in electric fields through step-scheme heterojunctions. Wang et al. [49] synthesized an MOF-derived N-doped ZnO carbon skeleton and grew hierarchical Bi2MoO6 nanosheets in situ to form a 3D layered S-scheme heterojunction (N-ZnO/C@Bi2MoO6). By combining structural advantages (highly open 3D framework) with defect features (oxygen vacancies) and an S-scheme charge-transfer pathway, the composite achieved strongly improved kinetics for SMX photodegradation under visible light. The pseudo-first-order kinetic constant reached 0.022 min−1, reported as 10× that of the MOF-derived ZnO component and 27.5× that of pristine Bi2MoO6; high SMX removal was achieved within 60 min in the authors’ tests. Importantly, this study also devoted attention to charge-transfer driving forces and degradation pathways, including mechanistic interpretation of S-scheme behavior and pathway analysis supported by computation, which is crucial for moving the field beyond empirical “activity boosting” toward more predictive design rules. The photocatalysis characteristics of antibiotics by metal oxide-based photocatalysts are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Photocatalysis characteristics of antibiotic by Metal oxide-based photocatalysts.

4.2. Bismuth-Based Photocatalysts

Bismuth, a metallic element from Group 5 of Period 6 in the periodic table, has an atomic electron configuration of 6s26p3 and typically exists in the form of Bi3+. Notably, the lone-pair distortion of the Bi 6s orbital in bismuth-based complex oxides can result in the overlap between the O 2p and Bi 6s orbitals in the valence band, which contributes to a reduced band gap and enhances the mobility of photoinduced charges, thereby improving the material’s visible light absorption performance [50]. Furthermore, the Bi5+ valence state, once the 6s orbital is empty, exhibits effective visible light absorption. Among the most extensively studied bismuth-based photocatalysts are Bi2O3, BiVO4, Bi2PO4, Bi2WO6, and bismuth-based halogen oxides (BiOX, where X = Cl, Br, or I) [51].

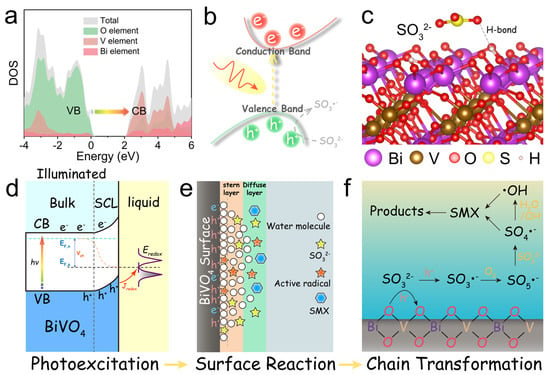

Recent advancements in bismuth-based photocatalysts underscore the pivotal roles of heterojunction engineering and defect modulation in enhancing antibiotic degradation. Notably, the Cd0.5Zn0.5S/carbon dots/Bi2WO6 (CZS/CDs/BWO) S-scheme heterojunction, synthesized via hydrothermal and solvothermal methods, utilizes carbon dots as interfacial electron mediators to suppress charge recombination, achieving a 6.4-fold higher TC degradation rate than pristine Bi2WO6 by preserving redox potentials through directional charge transfer [52]. Employing an alternative approach, a Z-scheme Au@TiO2/Bi2WO6 heterojunction was fabricated through reverse micelle sol–gel and hydrothermal techniques, combines plasmonic Au nanoparticles with Bi2WO6 nanosheets. This design broadened visible-light absorption via Au’s surface plasmon resonance and enhanced charge separation, enabling 96.9% SMX degradation within 75 min [53]. Beyond heterojunction configurations, defect engineering has emerged as an equally pivotal strategy. For instance, TaON/Bi2WO6 nanofibers with OVs, prepared by electrospinning and in situ growth, harness OVs as electron traps to suppress recombination while maintaining redox capacity via an S-scheme pathway, resulting in a 2.8-fold TC degradation improvement over bare Bi2WO6 [54]. While the rational design of heterojunctions and defects optimizes light absorption and bulk charge separation, the ultimate photocatalytic degradation efficiency is often governed by the interfacial charge transfer kinetics at the solid–liquid interface. For many bismuth-based photocatalysts that operate via non-radical pathways (e.g., direct hole oxidation), the reaction is confined to the immediate catalyst surface. Organic pollutant molecules, especially those with low polarity, can be effectively excluded from this reactive zone due to surface solvation and the formation of an electrical double layer, leading to severely limited kinetics despite thermodynamically favorable conditions. This critical barrier was systematically investigated in a study focusing on BiVO4. The researchers revealed that although BiVO4 has a high valence band potential, it could not degrade SMX directly. They identified a “surface solvation-induced inactivation” mechanism, where a hydrophilic surface and structured water layer prevent organic molecules from reaching the photo-generated holes [55]. To overcome this, they introduced sulfite (SO32−) as a redox mediator. Sulfite, with its higher adsorption affinity and lower ionization potential, can penetrate the compact layer, be oxidized by holes, and initiate a chain reaction to generate highly oxidizing sulfate radicals (SO4•−) that diffuse out to degrade pollutants (Figure 4). This work highlights that interface engineering, such as employing judicious redox mediators, is a crucial strategy to complement material-level modifications for achieving high degradation performance with bismuth-based photocatalysts.

Figure 4.

Electronic structure and solid–liquid interface reaction mechanism of BiVO4. (a) DOS calculation for BiVO4; (b) the proposed photocatalytic decomposition process of SO32− on the BiVO4; (c) adsorption of monodentate SO32− on the BiVO4 with (110) facet; (d) quasistatic energy profile and charge transfer pathways of BiVO4 under continuous illumination in contact with the aqueous solution. Jredox is the target charge transfer from the valence band to the redox reagent, SCL is space charge layer, Vph is the open-circuit photovoltage. EF,n and EF,p are the quasi-Fermi levels of electrons and holes under illumination, respectively; (e) model of the double-layer structure of BiVO4 in contact with the aqueous solution under equilibrium conditions; (f) transformation pathways of major species in Na2SO3/BiVO4 [55].

For many Bi-based oxides/oxyhalides, the intrinsic limitation is still the rapid recombination of photoinduced electrons and holes and the insufficient antibiotic, catalyst contact under realistic matrices. Thus, defect modulation (especially oxygen vacancies) and morphology control (ultrathin/porous structures) are widely adopted to simultaneously enhance light harvesting, adsorption, active-site density, and charge separation. Using TC as a representative antibiotic. Gao et al. [56] reported oxygen-vacancy–rich ultrathin porous Bi2WO6 nanosheets (VO-rich BWO), where the nanosheets were only 1.83 nm thick and exhibited abundant porous channels for mass transfer and interfacial reaction acceleration. The adsorption behavior of TC on VO-rich BWO followed pseudo-second-order kinetics (with R2 ≈ 0.9993), and the rate-controlling steps were attributed to diffusion and pore-filling processes, highlighting that well-designed porosity is not merely “surface area increase” but can reshape the adsorption–photocatalysis coupling mode in Bi-based systems. Under visible light, VO-rich BWO achieved 95.12% TC removal within 100 min (10 mg/L TC,0.2 g/L catalyst), and showed stable performance over multiple cycles; superoxide radicals () were identified as the dominant reactive species.

Another mainstream route to upgrade Bi-based photocatalysts is to build heterojunctions that enforce directional charge migration while preserving strong redox potentials. However, heterojunction effectiveness is highly sensitive to interface quality, band alignment, and built-in electric fields; consequently, the same “strategy label” (e.g., vacancy engineering or heterojunction construction) can produce widely scattered efficiencies across reports if interface and kinetics are not carefully controlled. In a recent study, a novel dual S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst, β-Bi2O3/NiAl-LDH/α-Bi2O3, was designed and fabricated. This composite was constructed through the phase transformation of Bi2O3 and coupling with layered double hydroxides (LDHs). The dual heterojunction was driven by internal electric fields (IEFs) and favorable band bending at the interface, significantly enhancing charge carrier separation and redox potential. Mechanistic investigations, corroborated by XPS and DFT calculations, revealed that electrons could migrate from the LDH to Bi2O3, generating internal electric fields and facilitating directional charge transfer. This charge transfer process promoted efficient photodegradation via synergistic radical pathways (, •OH, h+) [57].

Furthermore, coupling bismuth-based materials with carbonaceous or metallic components has been shown to enhance stability and reactivity. In this regard, a study revealed that surface oxygen vacancies in Nd-doped BiVO4 enabled efficient chlorite activation, converting to reactive ClO2 for 96% cephalexin degradation under visible light [58]. Importantly, DFT calculations and in situ DRIFTS suggest that the OV-introduced surface -OH serves as the Bronsted acidic center for chlorite adsorption. Likewise, reduced graphene oxide (rGO)/Bi4O5Br2 nanocomposites achieved 97.6% CIP removal through synergistic adsorption and a multi-radical (, •OH, h+) pathway [59]. Similarly, BiVO4/O-g-C3N4 heterojunctions were engineered with interfacial chemical bonds and Ovs, achieving 99.8% TC removal via synergistic redox pathways [60]. For BiOX (BiOBr in particular), a practical bottleneck is that pristine BiOBr often suffers from high carrier recombination and limited affinity toward certain organics; moreover, the preparation of complex multi-phase heterojunctions can be synthetically demanding. Using an in situ self-reduction route, Jiang et al. constructed a regenerable (Bi) BiOBr/rGO composite, in which metallic Bi nanoparticles are “perfectly lattice-matched” with the BiOBr matrix and can strengthen visible-light utilization through a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect, while rGO serves as an adsorptive support and fast electron-transfer network. Experimentally, the incorporation of Bi and rGO broadened visible-light absorption, lowered PL intensity (indicating suppressed recombination), and improved photocurrent/EIS behavior, collectively supporting more efficient charge separation and interfacial electron transport. Importantly, the study went beyond typical batch tests: the catalyst showed robustness in a continuous photocatalytic operation for 50 h, and in a continuous-flow column configuration almost 100% TC removal could be maintained for 10 h using TC-spiked river water, highlighting a device-oriented pathway for translating Bi-based powders toward application-relevant reactor modes [10]. In another study, surface oxygen vacancies in BiCrO4/g-C3N4 composites facilitated 92.5% levofloxacin (LEV) degradation within 120 min under LED light irradiation, where vacancies acted as electron highways to enhance interfacial charge transfer, outperforming vacancy-free counterparts by 2.3-fold [61].

To address the long-standing practical issue of nanopowder recovery and to better bridge laboratory degradation to engineered water-treatment units, another promising direction is immobilizing Bi-based photocatalysts on flexible/porous scaffolds that also offer adsorption enrichment. Using carbonized eggshell membrane (CEM) as a bio-derived support, Zhou et al. prepared a CQDs/BiOCl/CEM composite and achieved a clear adsorption–photodegradation synergy: under 10 mg/L TC and 0.5 g/L catalyst loading, the optimized sample delivered 98% total TC removal by combining 30 min dark adsorption and 30 min visible-light degradation [62]. Beyond concentration removal, the work also evaluated mineralization-related performance in a more complex matrix: in industrial wastewater the COD removal reached 73.1% after 120 min, substantially higher than pristine BiOCl (49.9%), suggesting that structural/charge modulation and support-assisted adsorption can improve not only decolorization/degradation but also deeper oxidation outcomes in realistic water samples. Given that post-treatment toxicity can be driven by transformation intermediates, embedding such “COD/mineralization-aware” comparisons into Bi-based photocatalyst discussions is particularly valuable for a review that aims to connect performance metrics with environmental safety.

Moreover, support materials play a crucial role in enhancing the performance of bismuth-based photocatalysts. Recent studies have highlighted the effectiveness of 3D porous sponges and zeolites as supports. For instance, Gao et al. [63] developed a 3D lignosulfonate-composited poly(vinyl formal) (PVF) sponge with a ternary photocatalyst, BiVO4/polyaniline (PANI)/Ag (PLS-BiVO4/PANI/Ag), for fluoroquinolone degradation. In this system, the lignosulfonate enhanced the sponge’s 3D structure, improving its adsorption capabilities for fluoroquinolones, while the uniformly distributed photocatalysts facilitated efficient photodegradation. Under near-neutral pH, over 90% removal was achieved in batch tests, with stable removal rates of 80% over 1800 min in continuous treatment. Similarly, zeolites have been used as supports to improve photocatalytic performance. Shabani et al. [64] synthesized Bi2Sn2O7-C3N4/Y (BSO-BCN/Y) photocatalysts supported on zeolites. Their findings indicate that the zeolite support enhanced the distribution of active phases, increased active sites, and improved the separation of electron–hole pairs, significantly boosting both adsorption and photocatalytic activity. Furthermore, novel BiOBr/CsXWO3@SiO2 aerogels further utilized pore-expansion templates to achieve near-complete antibiotic removal through adsorption/self-heating photothermal synergy [65]. These results emphasize the importance of selecting suitable support materials to optimize the efficiency of bismuth-based photocatalysts. The photocatalytic performance of various bismuth-based photocatalysts for antibiotic degradation is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Photocatalysis characteristics of antibiotic by Bismuth-based photocatalysts.

4.3. Silver-Based Photocatalysts

Silver (Ag) nanoparticles and silver-based compounds are frequently incorporated into photocatalytic systems to enhance performance, primarily due to the unique properties of silver, such as its strong light absorption, high conductivity, surface plasmon resonance property, narrow bandgap, outstanding quantum efficiency, photosensitive property, and photo-electrochemical features [66]. Among these, Ag3PO4, Ag3VO4, and Ag/AgX (X = Cl, Br, I) systems stand out for their visible-light responsiveness and redox capabilities. These silver-based photo-catalysts exhibit remarkable effectiveness in degrading antibiotics, primarily due to their ability to limit the recombination rate of electron–hole pairs and their wide spectrum of light absorption [67].

Silver-based semiconductors exhibit exceptional photooxidation potential under visible light. However, their practical application is limited by rapid photo-corrosion and electron–hole recombination. To address these dual challenges, constructing Z-scheme heterojunctions has proven effective. Cai et al. [68] developed an inorganic–organic Z-scheme photocatalyst by anchoring Ag3PO4 onto self-assembled PDI supramolecular rods (PDIsm) via electrostatic interactions. This improvement was attributed to the promoted charge separation/transfer enabled by the Z-scheme architecture, which also helps mitigate photocorrosion by reducing undesired electron accumulation on Ag3PO4. Building on this, Fan et al. [69] integrated 0D Ag3PO4 with 2D NiAl-LDH via a room-temperature precipitation strategy, establishing a Z-scheme system that exhibited 61.6-fold higher TC degradation rates than NiAl-LDH alone. Beyond conventional heterojunctions, structural engineering has been employed to further enhance performance. For instance, novel Ag/AgBr/AgI@SiO2 composite aerogels with controlled pore structures were developed, improving TC removal through a synergistic adsorption–photocatalysis effect. By optimizing pore volume and specific surface area via N,N-dimethylacetamide expansion, these aerogels achieved efficient -mediated degradation across a broad pH range (2–10) while maintaining high recyclability [70]. Liu et al. [71] developed Ag nanocluster-modified Ag3PO4 containing silver vacancies (Ag/Ag3PO4-VAg) via an in situ reduction method, significantly enhancing SMX degradation activity and stability. The Ag nanoclusters provided a localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect, while Ag vacancies improved electron trapping and water adsorption capacity, enabling complete degradation of 100 mL 20 mg/L SMX within 15 min with a remarkable rate constant of 0.306 min−1, which was 17 times that of pure Ag3PO4. The enhanced performance was attributed to improved charge separation and strong LSPR-induced local electric fields.

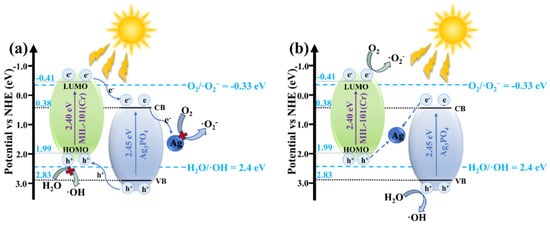

In this context, Wang et al. [72] designed an all-solid-state Z-scheme Ag/Ag3PO4/MIL-101(Cr) (AAM) heterostructure, which provides a representative example of how band engineering and metallic Ag bridges can be exploited to reconcile activity and stability in silver-based systems. On the basis of Tauc plots, Mott–Schottky analysis and VB-XPS, they showed that a conventional type-II band alignment between Ag3PO4 (E_CB ≈ +0.38 V vs. NHE) and MIL-101(Cr) (E_LUMO ≈ −0.41 V vs. NHE) would place photogenerated electrons on the CB of Ag3PO4 and holes on the HOMO of MIL-101(Cr), which is thermodynamically insufficient to drive O2/ and H2O/•OH conversions, in conflict with ESR and radical-trapping results. Consequently, an indirect Z-scheme pathway mediated by interfacial metallic Ag was proposed. As illustrated by the band-structure models of AAM (Figure 5), photoexcited electrons in the CB of Ag3PO4 and holes in the HOMO of MIL-101(Cr) are funneled to Ag nanoparticles, where they recombine, leaving highly reducing electrons in MIL-101(Cr) to generate and strongly oxidizing holes in the VB of Ag3PO4 to form •OH. This Z-scheme configuration markedly enhances spatial charge separation while preserving strong redox potentials on both components, thereby underpinning the superior TC degradation efficiency and photostability of the Ag/Ag3PO4/MIL-101(Cr) photocatalyst compared with its single counterparts.

Figure 5.

(a) Traditional type II heterojunction model and (b) Z-type heterojunction model of AAM [72].

In addition, the integration of plasmonic Ag nanoparticles has emerged as a successful strategy to amplify light harvesting and charge carrier dynamics in photocatalytic systems. Specifically, Liu et al. [73] designed Ag/Ag3PO4/C3N5 S-scheme heterojunctions, where the LSPR from Ag nanoparticles broadened visible-light absorption, achieving 28.38-fold higher LEV degradation than C3N5. Similarly, another practical direction is building multifunctional composites that integrate adsorption enrichment, photocatalysis, and convenient recovery. Liao et al. [74] prepared a magnetic Fe3O4@mTiO2@Ag@GO composite via a microwave-assisted route, combining (i) Fe3O4 for magnetic recyclability, (ii) TiO2 as a stable photocatalytic scaffold, (iii) Ag nanoparticles to broaden visible-light response through LSPR, and (iv) GO to enhance adsorption and interfacial electron transport. For NOR removal, Fe3O4@mTiO2@Ag@GO delivered a photodegradation rate 4.6× that of Fe3O4@mTiO2 and 1.4× that of Fe3O4@mTiO2@Ag, underscoring the synergistic contribution of GO-assisted adsorption/charge transfer on top of Ag plasmonic enhancement. Furthermore, a synergistic approach combining photocatalysis with other methods has also proven effective. For instance, a 3D Bombax-structured Ag3PO4/carbon nanotube sponges demonstrated 90% TC degradation under combined ultrasound–visible light irradiation. The ultrasound-induced cavitation effect (100 W) enhanced charge transfer efficiency, contributing over 50% of the total degradation kinetics while reducing energy demand [75]. Crucially, the synergistic effect of Ag NPs and GO is crucial for achieving significant enhancements in photocatalytic performance.

Recent advancements have further demonstrated that integrating silver catalysts with tailored carriers improves both stability and scalability. Importantly, recent review emphasized the gap between powder photocatalyst demonstrations and real-world deployment (recovery, continuous operation, matrix effects). In this context, immobilization into films is a valuable Ag-based implementation pathway. Vanlalhmingmawia et al. [4] developed Clay/TiO2/Ag0 nanocomposite films and demonstrated simultaneous degradation of TC and SMZ, achieving 72.4% TC and 58.3% SMZ removal within 60 min, while maintaining >90% stability over six cycles, which features that directly address catalyst retrieval and reuse. In parallel, Negoescu et al. [76] harnessed activated carbon (AC) as a co-surfactant for TiO2-based photocatalysts: the Ag/Ag2O/TiO2-AC composite leveraged AC hydrophobicity and large surface area to synergize adsorption and photocatalysis for CIP removal. Collectively, these carrier-integrated systems transcend mere activity enhancement, offering scalable solutions for practical implementation. The photocatalysis characteristics of antibiotics by silver-based photocatalysts are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Photocatalysis characteristics of antibiotic by Silver-based photocatalyst.

4.4. MOFs-Based Photocatalysts

In recent years, MOFs, a new class of functional inorganic-organic hybrid materials, have experienced rapid development. They are porous, crystalline structures formed by the coordination of metal ions or small metal ion clusters (nodes) with organic ligands (linkers) [77]. MOFs offer several advantages over traditional photocatalytic semiconductors, making them promising for applications in antibiotic adsorption and degradation in water. First, their porosity of MOFs and their open frame structure facilitate the diffusion of degraded substances to the active sites of the catalyst. Secondly, MOFs have an extremely high specific surface area and adjustable porosity. Such properties are suitable for constructing composite catalytic materials with other active substances. Finally, the spectral response range of MOFs can be well regulated by introducing functional groups [78,79]. These properties make MOFs promising as effective materials for antibiotic adsorption and photocatalysis in water. Recent efforts have focused on combining MOFs with other materials to bolster catalytic efficiency, yielding MOF composite photocatalysts, which underscores the viability of this approach.

The establishment of heterojunctions significantly improves the photocatalytic efficiency of MOFs by enhancing the separation of photo-generated electron–hole pairs, increasing light absorption, and providing more reactive sites, which collectively boost photocatalytic performance. A representative approach is to couple MOFs with visible-light-active semiconductors to form heterojunctions that promote charge separation while retaining the adsorption capability of MOFs. Li et al. [80] fabricated an S-scheme MIL-101(Fe)/Bi2WO6 heterostructure. The integration of MIL-101(Fe) octahedrons enlarged the surface area and introduced oxygen vacancies, facilitating charge carrier separation. This engineered heterojunction exhibited a 10.5-fold increase in the photocatalytic activity toward TC degradation compared to the individual components. Importantly, mineralization was also evaluated, with a measurable TOC reduction reported within the same reaction period, indicating that the process went beyond mere transformation. Similarly, Su et al. [81] constructed direct Z-scheme Bi2MoO6/UiO-66-NH2 heterojunctions with flower-like morphology, enabling 100% ofloxacin (OFL) and 96% CIP degradation within 90 min via synergistic •OH/h+/ pathways while reducing toxicity. Ternary heterojunctions further optimize performance: Liu et al. [82] designed a Z-scheme NH2-MIL-125(Ti)/Ti3C2 QDs/ZnIn2S4 system, wherein MXene quantum dots accelerated interfacial electron transfer, achieving 96% TC degradation in 50 min. Nano-heterojunction engineering has also demonstrated efficacy. Cao et al. [77] synthesized SnS2@UiO-66 via crystal regrowth, enlarging active sites and achieving 90% TC degradation in 75 min (5.1× faster than UiO-66) under visible light.

Metal doping represents another effective approach to modify MOF photocatalysts. Current evidence suggests that doped metals can facilitate electron transfer through metal-to-metal electron transfer (MMCT). A typical example is Cu incorporation into UiO-66 to generate oxygen-vacancy-related defects and broaden light utilization [83]. The modified MOF exhibited substantially improved adsorption toward CIP: about half of the target antibiotic could be captured, corresponding to an adsorption capacity on the order of 53.7 mg g−1, which was far higher than that of pristine UiO-66. Under full-spectrum Xe lamp irradiation, the optimized Cu-doped UiO-66 removed 93% of CIP within 1 h with a kinetic constant of 0.03257 min−1, and the overall photocatalytic performance was reported to be several-fold higher than that of the parent UiO-66. Mechanistically, the enhancement was attributed to the synergistic role of (i) adsorption enrichment in the porous framework, (ii) defect/metal-assisted electron transfer, and (iii) improved separation of photogenerated carriers, which collectively increased ROS formation and accelerated CIP breakdown. In addition, cyclic tests indicated that the catalyst retained activity after repeated use, with only a slight decline attributed to partial occupation of adsorption sites by residual organics. Similarly, Du et al. [84] utilized Co-MOFs as precursors to fabricate nitrogen-rich Co-doped C3N5 (Co-C3N5). The highly dispersed Co sites narrowed the bandgap to ∼1.20 eV, enabling complete degradation of 30 mg/L chlortetracycline hydrochloride (TCH) within 6 min under a 50 W LED lamp via peroxymonosulfate (PMS) activation. Li et al. [14] demonstrated that sulfidation of Zn/In-MOFs yielded self-assembled hollow microtubular Zn-In-S structures (e.g., ZnS/ZnIn2S4). The Zn dopant was crucial for forming a direct Z-scheme heterojunction, which enhanced charge separation and boosted reactive oxidant generation (•OH, , h+), achieving >90% TC degradation within 1 h under solar light (kinetic constant: 0.0379 min−1). Beyond elemental doping, Liu et al. [85] constructed a Z-scheme Ti-MOF/Ag/NiFeLDH photocatalyst by depositing plasmonic Ag nanoparticles onto NH2-MIL-125(Ti)/NiFe LDH hybrids. The Ag nanoparticles acted as electron bridges, facilitating interfacial charge transfer and significantly enhancing visible-light degradation of LEV (92% in 70 min) primarily via and •OH radicals, while maintaining >90% efficiency after 5 cycles.

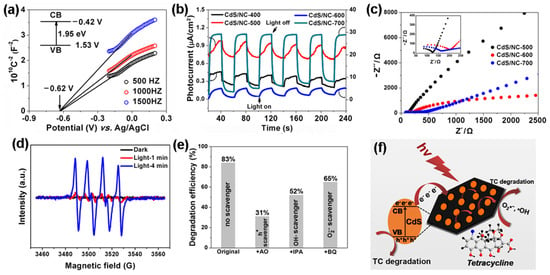

MOFs can also be used as sacrificial templates/precursors to construct semiconductor–carbon composites with boosted charge transport. Cao et al. [86] prepared CdS/nitrogen-doped carbon (CdS/NC-T) photocatalysts by in situ carbonization of a cadmium MOF, and the optimized CdS/NC-500 sample showed markedly enhanced visible-light degradation of tetracycline compared with pristine CdS and low-temperature analogs. Electrochemical analyses, including Mott–Schottky plots, transient photocurrent responses and EIS measurements (Figure 6), confirmed efficient separation and interfacial transfer of photogenerated carriers in CdS/NC-500. Combined with DMPO–ESR and scavenger experiments, which identified h+, •OH and as the dominant reactive species, they proposed a mechanism in which the conductive N-doped carbon matrix acts as an electron highway and adsorption platform, thereby accelerating redox reactions during antibiotic photodegradation. Morphological control can also effectively improve the photodegradation efficiency of antibiotics within MOFs. In this regard, Yu et al. [87] immobilized UiO-66-NH2/BiOBr heterojunctions on macroscale carbon fiber cloth via solvothermal and dip-coating methods. This unique macroscopic morphology enabled strong antibiotic adsorption (65.4% LEV) and facilitated recyclability, achieving 92.2% visible-light degradation within 120 min while maintaining stable efficiency over 4 cycles. Similarly, Zhang et al. [88] designed pomegranate-shaped ZnO@ZIF-8 through a template-directed synthesis, in which ZIF-8 was grown in situ on petal-shaped ZnO. This hierarchical structure provided high specific surface area to enrich TC, resulting in 91% degradation within 50 min under visible light and 100% activity retention after 5 cycles. Fang et al. [89] further demonstrated that sulfidation of MIL-68-In precursors yielded hollow In2S3 nanorods with invaginated hexagonal morphology. The hollow structure enhanced light absorption and electron–hole separation, enabling efficient degradation of both dyes and TC hydrochloride. To address the practical challenge of catalyst recovery and to bridge the gap between powder photocatalysts and engineering deployment, MOF-based photocatalysts have also been integrated into structured or immobilized architectures. A notable route is to assemble MOF-containing hybrids with conductive carbon and semiconductor components, then fabricate monolithic or 3D-structured photocatalysts for easier handling. In a WO3–UiO-66@reduced graphene oxide (rGO) system, coupling UiO-66 with WO3 and rGO improved both adsorption and charge transport, while the structured (3D) configuration further increased accessibility and facilitated reuse [90]. Such results highlight that structural engineering (e.g., 3D configuration) can be an effective complement to compositional engineering, enabling both high activity and improved operational convenience.

Figure 6.

(a) Mott–Schottky plots for CdS/NC-500. (Inset) Energy diagram of the CB and VB levels. (b) Transient photocurrent plots for CdS/NC-T. (c) Electrochemical impedance spectra of CdS/NC-T. (d) DMPO– spin-trapping ESR spectra for CdS/NC-500. (e) Photocatalytic efficiency of CdS/NC-500 toward TC degradation with exposure to various scavengers. (f) Proposed mechanism of photocatalytic degradation of antibiotics for CdS/NC-500 [86].

Catalyst recovery has long been a limiting factor for the practical application of photocatalysis. To address this, researchers have explored various methods for recovering MOF-based materials, including the preparation of magnetic materials to assist in separation. For instance, Zhang et al. [91] fabricated a novel MOF-derived ZnFe2O4/Fe2O3 perforated nanotube photocatalyst via direct calcination of MIL-88B/Zn, forming an intimate Z-scheme heterojunction with hierarchical porous architecture. The optimized sample of ZnFe2O4/Fe2O3 perforated nanotubes achieved a high CIP degradation efficiency of 96.5% under simulated light irradiation. The degradation of CIP under these conditions follows two main pathways. The first pathway involves hydroxylation and piperazine ring cleavage of CIP, leading to various intermediates that are eventually mineralized into CO2 and H2O. The second pathway involves the electrophilic addition of •OH, resulting in intermediates such as IP8 (m/z = 348) and IP9 (m/z = 304). In addition, the photocatalyst exhibited magnetic behavior with a saturation magnetization of 0.44 emu/g, enabling rapid magnetic separation and maintaining 92.6% of its activity after five consecutive cycles, confirming its excellent reusability. Similarly, Suo et al. [92] engineered a spindle-shaped ZnO/ZnFe2O4 Z-scheme heterojunction from MIL-88A(Fe)@Zn, achieving 86.3% TC hydrochloride degradation under visible light. Its intrinsic magnetism (coercivity: 108 Oe) facilitated effortless recovery from tap water, maintaining 83.74% efficiency after five uses. Overall, these studies confirm that magnetic MOF-derived photocatalysts enhance recyclability without compromising performance, addressing a critical barrier for scalable wastewater treatment. The photocatalysis characteristics of MOF-based photocatalysts for antibiotic degradation are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Photocatalysis characteristics of antibiotic by MOFs-based photocatalysts.

4.5. Carbon-Based Photocatalyst

Carbon-based photocatalysts, including graphene derivatives, biochar, and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4 or CN), have demonstrated significant potential in photocatalytic antibiotic degradation. Key advantages include inexpensive synthesis, high SSA, a well-developed and adjustable network of micropores, mesopores, and macropores, and a large number of oxygen-containing functional groups, all contributing to their efficacy [93,94].

Graphene and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) are widely employed as electron mediators in heterojunction systems to suppress charge recombination and broaden light absorption [95]. For instance, a Z-scheme Cu2O/rGO/BiVO4 composite, synthesized via a two-step solvothermal method, achieved 96% TC degradation under visible light. The in situ growth of Cu2O and BiVO4 on rGO nanosheets created intimate interfacial contact, enabling rGO to act as an electron bridge for directional charge transfer while preserving the high redox potentials of individual components [96]. Similarly, rGO-ZnS-CuS nanocomposites, prepared by a surfactant-free microwave-assisted approach, degraded 93% OFL via dominant and •OH radical pathways. The microwave-induced rapid nucleation ensured uniform dispersion of ZnS-CuS nanoparticles on rGO, enhancing light absorption and exposing active sites for radical generation [97]. Graphene and its derivatives are typically incorporated as conductive 2D networks to promote interfacial electron migration and to increase accessible surface area, thereby improving both adsorption and photocatalytic kinetics. A recent study employed cerium-doped leaf-like CdS coupled with ultrathin nitrogen-doped rGO (Ce-CdS/N-rGO). The preparation process of Ce-CdS/N-rGO composites involves multiple steps, including ultrasonic dispersion of GO, followed by hydrothermal synthesis to form Ce-CdS, and further modification with nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide (N-rGO). The Ce3+/Ce4+ redox pairs act as electron capture sites within the CdS matrix, facilitating the interfacial charge transfer, which is enhanced by the strong interaction between Ce-CdS and N-rGO, as confirmed by DFT calculations. This synergistic effect of doping and interface engineering, combined with the enhanced adsorption capacity provided by N-rGO, resulted in a remarkably high TC removal efficiency of 94.5% under visible light, primarily driven by generated through the efficient interfacial charge transfer. The mass spectrometry (MS) results further suggested stepwise oxidation/reduction and bond-cleavage processes, ultimately producing smaller molecules and partial mineralization products [98].

It is well established that biochar, a sustainable carbon matrix derived from biomass, enhances photocatalytic performance by improving adsorption capacity and providing defect-rich active sites. For example, TiO2 nanoparticles were uniformly immobilized onto pomelo-peel-derived biochar via a liquid-phase deposition followed by pyrolysis, forming a dense and crystalline composite structure. The optimal sample exhibited a low Raman ID/IG ratio of 0.05, indicating well-restored graphitic domains that facilitated electron transport. Combined with the hierarchical porosity of the biochar matrix, this architecture significantly enhanced charge separation and pollutant adsorption, ultimately achieving a TC degradation rate constant of 0.021 min−1 under simulated solar light, and maintained near 80% removal efficiency after five cycles, indicating acceptable reusability (with the slight loss mainly attributed to catalyst loss during recovery) [99]. Similarly, CoFe-LDH supported on petrochemical sludge biochar was prepared through a hydrothermal co-precipitation method. The biochar’s high conductivity (Raman D/G ratio of 0.05) enabled rapid electron transfer, achieving complete SMX removal within 100 min, while the LDH’s layered structure provided abundant active sites for hydroxyl radical generation [100]. Biochar composites further facilitate the integration of noble metals. For instance, Ag@biochar-rGO nanohybrids, synthesized using marine algae Trentepohlia sp. as a green reductant, demonstrated dual functionality by degrading rifampicin via •OH while reducing Cr(VI) under sunlight, leveraging rGO electron shuttling and Ag’s localized surface plasmon resonance [101]. In addition, a pinecone-derived biochar, when used in a CaIn2S4-ZnO/Biochar S-scheme system fabricated via hydrothermal-wet impregnation, achieved >95% TC degradation. The biochar’s oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., C-OH) anchored the heterojunction, stabilizing charge transfer pathways and enhancing H2O2 production for radical-driven degradation [102].

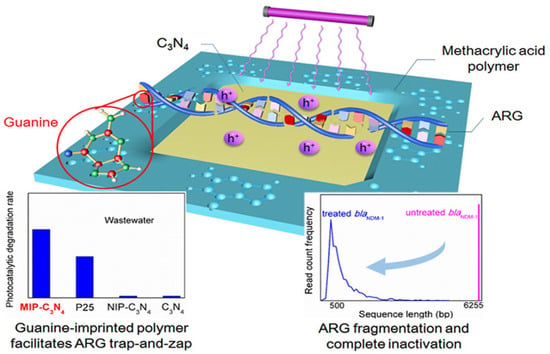

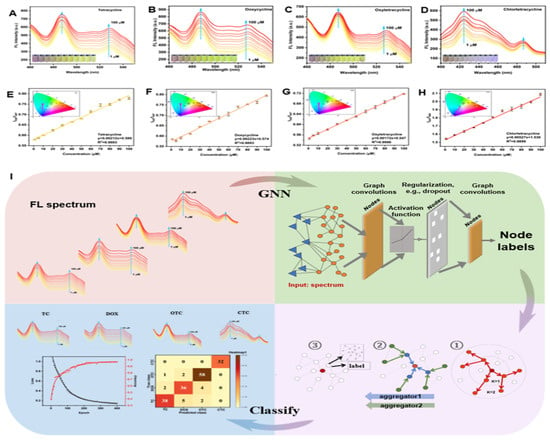

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) has emerged as a research hotspot in carbon-based photocatalysis due to its visible-light responsiveness (bandgap ~2.7 eV), chemical stability, and low cost. Significant improvements in charge separation efficiency and light absorption range have been achieved through morphology engineering, elemental doping, and heterojunction construction. For instance, oxygen-doped biochar-modified g-C3N4 (A-CN), synthesized by calcining hydroxyl-rich aloe fiber-derived precursors, demonstrated a reduced bandgap (2.2 eV vs. pristine 2.7 eV) and achieved 95% TC degradation with 88% mineralization within 1 h under visible light. This performance originated from hole-mediated deamidation and ROS-driven oxidative ring-opening pathways, enabling deep antibiotic mineralization [103]. Moreover, heterojunction designs with transition metal carbides (e.g., Co-Mo2C/g-C3N4) enhanced interfacial electric fields, accelerating charge separation. The composite exhibited a TC degradation rate three times higher than pristine g-C3N4, attributed to enhanced electron density in Mo 3d orbitals and Co-catalyzed oxygen reduction reactions [104]. As a metal-free visible-light-responsive photocatalyst, g-C3N4 is often upgraded via defect engineering (e.g., N vacancies) and/or single-atom modulation to improve light absorption, charge separation, and ROS production, Zhang et al. [105] constructed a Mo single-atom anchored N-vacancy tubular g-C3N4 (Mo/Nv-TCN) photocatalyst through a dual optimization strategy combining morphological control and defect engineering. The introduction of nitrogen vacancies and atomically dispersed Mo enabled the formation of a stable Mo–2C/2N coordination structure, which acted as a bridge for directional charge transfer. This structural refinement led to a narrowed bandgap and enhanced visible-light absorption capacity. Under visible-light irradiation, the optimized Mo/Nv-TCN system achieved 94.45% TC degradation within 60 min, with an apparent rate constant 4.46 times that of pristine g-C3N4. Mechanistic investigations further revealed that the photocatalytic degradation involved multiple ROS, including , h+, and 1O2, with Mo sites serving as the main active centers. Beyond “pure” carbon nitride, constructing 2D/2D heterostructures is another effective carbon-based route to improve adsorption and accelerate interfacial charge transfer, a 2D/2D S-type heterojunction has been developed by intercalating ultrathin g-C3N4 into NH4V4O10 nanosheet. This architecture, exemplified by the 50-CNNS/NH4V4O10 composite, achieved an impressive 92% removal rate of CIP under simulated sunlight, demonstrating excellent stability and photocatalytic performance. Confirming the enhanced photocatalytic degradation when compared to the separate components. The improved catalytic efficiency was attributed to the efficient charge separation, interfacial electron transport, and increased surface adsorption enabled by the exposed NH4+ groups, which promote the adsorption of CIP molecules via hydrogen bonding with fluoride (F−). From an environmental-safety standpoint, the authors also evaluated V leaching by ICP: the dissolved vanadium after recycled reaction was 0.0668 mg/L, which they noted was below the cited drinking-water limit (0.1 mg/L), suggesting manageable secondary-pollution risk under their conditions [106]. Zhang et al. [107] developed xB-PCN, a phosphorus and boron co-doped hollow tubular g-C3N4, which exhibited significantly enhanced photocatalytic activity for CIP degradation under visible light. The introduction of p-n heterojunctions within a single g-C3N4 facilitated efficient charge separation, resulting in 87.56% CIP removal in 60 min and excellent stability after 5 cycles with only a 2.59% reduction in efficiency. Beyond the removal of antibiotic molecules, g-C3N4 can also be engineered to mitigate the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. Yuan et al. [108] fabricated molecularly imprinted graphitic carbon nitride (MIP-C3N4) nanosheets, in which guanine was used as a template to create specific recognition cavities for a plasmid-encoded extracellular antibiotic resistance gene (blaNDM-1) in secondary effluent. As schematically illustrated in Figure 7, the guanine-imprinted sites endow MIP-C3N4 with a “trap-and-zap” function: selective adsorption enriches eARGs near the photocatalyst surface, allowing photogenerated holes to efficiently fragment the DNA while minimizing scavenging by background organic matter. Consequently, photocatalytic removal of blaNDM-1 in real wastewater (k = 0.111 ± 0.028 min−1) was approximately 37-fold faster than with pristine g-C3N4 (k = 0.003 ± 0.001 min−1), and the resulting short DNA fragments exhibited a markedly reduced potential for horizontal gene transfer. This study highlights that molecular imprinting offers a promising strategy to improve the selectivity of carbon-based photocatalysts toward both antibiotics and associated resistance determinants. The photocatalysis characteristics of antibiotics by carbon-based photocatalysts are clearly summarized in Table 6.

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration of molecularly imprinted g-C3N4 (MIP-C3N4) for selective adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of extracellular antibiotic resistance genes [108].

Table 6.

Photocatalysis characteristics of antibiotic by Carbon-based photocatalysts.

4.6. MXene-Based Photocatalysts

MXene, a family of two-dimensional transition metal carbides/nitrides characterized by tunable surface functional groups, exceptional electrical conductivity, and hydrophilic surfaces, has emerged as a highly promising platform for constructing advanced photocatalysts targeting antibiotic degradation [109]. The unique layered structure, abundant exposed active sites, and tailorable electronic properties of MXene facilitate efficient light harvesting and, crucially, promote the spatial separation and transport of photogenerated charge carriers, effectively addressing the key bottlenecks of rapid recombination and sluggish kinetics prevalent in conventional photocatalytic systems [110,111].

Typically synthesized through the selective etching of aluminum layers from MAX phases (e.g., Ti3AlC2) using hydrofluoric acid (HF) or fluoride-containing solutions, MXenes (predominantly Ti3C2TX) are frequently integrated with semiconductors to form heterostructured composites. Advanced synthesis strategies, including in situ oxidation, hydrothermal/solvothermal assembly, electrostatic self-assembly, and surface functionalization, enable precise architectural control over MXene-based photocatalysts. For instance, a Bi2MoO6/TiO2/Ti3C2 composite, fabricated via a hydrothermal process (180 °C, 12 h) utilizing Bi(NO3)3·5H2O, Na2MoO4, and Ti3C2 precursors, demonstrated remarkable efficiency, degrading 87.5% of TC within 150 min under visible light irradiation. This enhanced performance was ascribed to the Ti3C2 nanosheets acting as highly efficient electron mediators within a Z-scheme heterojunction, significantly accelerating interfacial charge transfer between Bi2MoO6 and TiO2 while effectively suppressing electron–hole recombination [112]. Similarly, Ag/TiO2/Ti3C2 hybrids were engineered by thermally oxidizing Ti3C2 in an inert atmosphere (450 °C, Ar) to generate in situ TiO2 nanoparticles, followed by the photodeposition of plasmonic Ag nanoparticles (5 wt%). This composite exhibited superior visible-light photocatalytic activity for the degradation of sulfamethazine compared to pristine TiO2, attributed to the synergistic interplay between Ag’s LSPR effect, which broadens light absorption into the visible spectrum, and the high conductivity of Ti3C2, which facilitates rapid electron extraction and transport, thereby minimizing charge recombination and enhancing ROS generation [113].

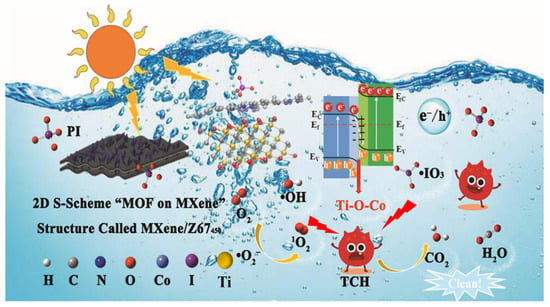

The photocatalytic mechanisms underpinning MXene-based systems are diverse and often involve synergistic effects. Key mechanisms include the formation of Schottky junctions, S-scheme or Z-scheme heterostructures, and the integration of photothermal conversion. For example, in Ti3C2/Bi12O17Cl2 Schottky heterojunctions synthesized via a one-step solvothermal method, a work function difference establishes an interfacial electric field that drives the transfer of photogenerated electrons from Bi12O17Cl2 to Ti3C2. This efficient charge separation facilitates the generation of potent ROS ( and •OH radicals). Optimally, the composite with 3 wt% Ti3C2 achieved an impressive 95.64% removal of tetracycline TCH within just 60 min under visible light, highlighting the critical role of the Schottky barrier in suppressing recombination and leveraging MXene conductivity [114]. In addition to Schottky-type contacts, constructing MOF-on-MXene S-scheme heterostructures has recently emerged as an effective strategy to exploit both the submetallic conductivity of MXenes and the abundant catalytic sites of MOFs. Chen et al. [115] designed a 2D S-scheme “MOF-on-MXene” photocatalyst (MXene/Z67450) by in situ growth and pyrolysis of ZIF-67 on Ti3C2TX, generating interfacial Ti–O–Co and Co–N4 bonds that create an internal electric field and atomic-level charge-transfer channels. In a periodate-based advanced oxidation process, the MXene/Z67450 heterostructure exhibited markedly enhanced activity for tetracycline hydrochloride degradation, outperforming MXene450, Z67450 and several commercial metal oxides, owing to more efficient photocarrier separation and facilitated PI adsorption/activation at the S-scheme interface. Spectroscopic analyses, electrochemical measurements and DFT calculations confirmed that the built-in electric field drives photogenerated electrons from Z67450 to MXene450 through the Ti-O-Co bridge while preserving the strong oxidation capacity of holes in Z67450, thus enabling the generation of multiple reactive oxygen and iodine species (e.g., 1O2, •OH, , •IO4 and •IO3) for selective TCH removal, as schematically illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of the S-scheme MXene/Z67450 “MOF-on-MXene” heterostructure for visible-light-driven PI activation and efficient tetracycline hydrochloride degradation [115].

Surface modification of MXene provides a novel approach for further tailoring its properties. For instance, sulfonated Ti3C2 (Ti3C2-SO3H) was coupled with g-C3N4 via hydrothermal treatment to form a composite. The resulting Schottky junction at the interface significantly reduced charge recombination, enabling 75.4% TC removal under visible light in 120 min. Crucially, the introduced sulfonic acid groups (-SO3H) enhanced the surface hydrophilicity of Ti3C2, improving pollutant adsorption and increasing the accessibility of active sites for ROS-mediated degradation [116]. Beyond charge separation, the inherent photothermal conversion capability of MXenes broadens their utility, particularly under near-infrared (NIR) irradiation. A complex composite, NaYF4: Tm3+/Er3+/Yb3+@BiOI/TiO2-Ti3C2, synthesized via electrostatic self-assembly and calcination, combined upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) with MXene-derived TiO2 [117]. The layered structure of Ti3C2 MXenes, the flower-like morphology of TiO2@Ti3C2, and the uniform dispersion of UCNPs within BiOI nanosheets. The TiO2 nanoflowers in the TiO2@Ti3C2 composite were uniformly distributed across the Ti3C2 MXene layers, enhancing the material’s surface area and, consequently, improving photocatalytic efficiency. Furthermore, the UCNPs were evenly dispersed within BiOI, facilitating effective energy transfer from UCNPs to BiOI. The UCNP@BiOI@TiO2-Ti3C2 composite demonstrated the synergistic effects of UCNPs and TiO2@Ti3C2, where the incorporation of TiO2-derived Ti3C2 MXene not only extended the light absorption to the NIR region but also enhanced the photothermal effect, accelerating the reaction rate. These findings indicate that the integration of Ti3C2 MXenes, UCNPs, and BiOI significantly enhances the photocatalytic performance of the composite by expanding its light spectrum utilization and promoting charge separation.