Abstract

Optoelectronic synapses based on transition metal dichalcogenides have received much attention as artificial synapses due to their good stability in the air and excellent photoelectric properties; however, they suffer from ultraviolet light-triggered synapses due to the ultraviolet insensitivity of transition metal dichalcogenides. In this paper, an ultraviolet-enhanced artificial synapse was achieved on WSe2 combined with SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ phosphor. The strong ultraviolet absorption of SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ phosphor and radiation reabsorption are responsible for the ultraviolet-enhanced response of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 synapse. The excitatory post-synaptic current of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 synapse triggered by a single pulse at 365 nm was enhanced 4 times more than that from 2D WSe2, while the decay time of the post-synaptic current was 9.7 times longer than those from the WSe2 device. The excellent ultraviolet sensitivity and decay time promoted the good regulation of the synaptic plasticity of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device in terms of power densities, pulse widths, pulse intervals, and pulse numbers. Furthermore, outstanding learning behavior was simulated successfully with a forgetting time of 25 s. Handwritten digit recognition was realized with 96.39% accuracy, based on the synaptic weight of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 synapse. This work provides a new pathway for ultraviolet photoelectric synapse and brain-inspired computing.

1. Introduction

The development of artificial intelligence and big data has placed new demands on computing power. Traditional computers using the Newman system cannot meet current needs, due to the separation of computation and storage [1]. Brain-like artificial neural networks have been proposed as a breakthrough approach, due to their low energy consumption, parallel processing capabilities for data computation and storage, and their memory properties with 1011 neurons and 1015 synapses [2,3]. Thus, more attention has been paid to the simulation of artificial synapses and neurons. Among all of the materials, two-dimensional (2D) materials have attracted much attention, due to their advantages of atomic layer thickness and low energy consumption [4,5]. In particular, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) have become core materials for artificial synapse simulation because of their good stability in the air and excellent photoelectric properties [6,7,8,9,10].

Visible light-triggered artificial synapses of TMDCs were first developed and implemented in a MoS2/PTCDA hybrid heterojunction [11], where the type-II heterojunction enabled the carriers to be injected, separated, and captured in the interface, along with a high facilitation ratio of 500% for the optoelectronic synapses. Then, visible light-triggered artificial synapses sparked a research boom, based on the visible response of TMDCs themselves or those constructed from heterogeneous structures, such as MoS2 [12], WSe2 [13], WS2 [14], MoS2/MoTe2 [15], Ta2NiS5/MoS2/Gr [16], and WSe2/Gr [17]. In these studies, van der Waals heterostructures have emerged as a pivotal platform for high-performance optoelectronic devices [18,19,20,21,22], owing to their tunable interfacial barriers, highly controllable band alignment engineering, and exceptional optoelectronic coupling capabilities [23,24]. This flexible stacking configuration enables the integration of diverse functional materials, overcoming the limitations inherent in single-component systems. It facilitates not only enhanced photodetection but also complex neuromorphic functionalities, such as high-sensitivity, wavelength-discriminative, and multimodal sensing [25,26,27], thereby laying the foundation for advanced artificial visual systems. Compared to the lush and vibrant visible synapses, little attention has been paid to ultraviolet (UV)-triggered synapses, due to the insensitive response of TMDCs to UV light (Table S1) [28,29].

In 2018, Guo et al. first reported photonic potentiation and electric habituation in a monolayer MoS2 with excitation at 310 nm [30]. Four years later, Roy et al. reported the MoS2 artificial optoelectronic synapses triggered at 300 nm, where gate-tunable potentiation was achieved with the number of UV pulses as high as 512 [31]. Subsequently, Jo et al. confirmed the weak response of UV pulses in trilayer MoS2, MoSe2, MoTe2, and WSe2, where the linearly enhanced synapse potentiation was excited at 400 nm [32]. Then, UV-sensitized materials were utilized to construct the heterojunctions between TMDCs to attain UV artificial synapses [33,34]. ZnO/WSe2 and ZnO/MoS2 were explored to establish UV artificial synapses for the large absorption cross section and ultrasensitive UV response of ZnO [33,34]. The paired pulsed facilitation (PPF) of ZnO/MoS2 optoelectronic synapses was improved to 160% triggered by 375 nm [33]. Later, the heterojunction of GaN/WSe2 was built to extend the response range of optoelectronic synapses to the UV range, giving a high image recognition accuracy of 96.6 [35]. Although significant progress was achieved in the UV photo-synapse of TMDCs, they are still in their infancy.

Herein, UV-enhanced response artificial optoelectronic synapses have been created on WSe2-SrAl2O4 composites, where SrAl2O4: 6% Eu, 4% Dy is responsible for responding to UV light for its large UV absorption section. SrAl2O4: 6% Eu, 4% Dy transfers UV to visible light centered at 522 nm by the downshift process, followed by absorption and photoelectric conversion in WSe2. The UV response was improved to 4 times higher than that from 2D WSe2. The photo-synapse performance was obtained, including excitatory post-synaptic current (EPSC), short-term memory (STM), long-term memory (LTM), and the transition from short-term memory (STM) to long-term memory (LTM), excited by 365 nm with various power densities, pulse widths, pulse intervals, and pulse numbers. The simulation of the learning–forgetting–relearning process was imitated with a forgetting time as long as 22 s. Furthermore, the optoelectronic synapses based on WSe2-SrAl2O4 composites can simulate recognition of handwritten digit images with a high accuracy of 96.39%. The study provides a simple approach for UV-enhanced optoelectronic synapses, suggesting the high potential in neuromorphic computing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Synthesis

In this experiment, layered WSe2 was prepared via physical vapor deposition (PVD) in a tube furnace under atmospheric pressure (Figure S1). WSe2 powder (99.9%, Alfa Aesar, Shanghai, China) was used as the precursor, and a silicon wafer (Lijing Electronics Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) with a surface oxide layer served as the substrate. The detailed procedure was as follows. First, the silicon wafer was cleaned. Then, a quartz boat loaded with WSe2 powder was placed at the center of the heating zone, while another quartz boat carrying the silicon substrate was positioned in the deposition zone near the tube mouth in the low-temperature region, with a distance of 8–15 cm maintained between them. Before the reaction, the chamber was evacuated to remove impurities, followed by the introduction of high-purity argon (99.999%, Wangzhou Gas Co., Ltd., Nanning, China) to establish an inert growth atmosphere. During the growth stage, the precursor was heated to the set temperature via a temperature-control system, causing a solid-to-vapor phase transition. The resulting vapor was transported by argon carrier gas to the substrate surface in the low-temperature zone, where layered WSe2 was deposited. After growth, the sample was cooled inside the furnace, and its morphology was preliminarily characterized using optical microscopy.

By systematically optimizing the key parameters such as the growth temperature, holding time, and gas flow rate, the optimal process conditions were determined as follows: growth temperature 1185 °C, holding time 5 min, and gas flow rate 30 sccm. Under these conditions, layered WSe2 samples with uniform morphology suitable for subsequent device fabrication were successfully obtained.

2.2. Device Fabrication

The device fabrication primarily involved two key steps: electrode preparation and SrAl2O4 powder (SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+, Longli Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) coating. The specific procedure was as follows:

- Electrode preparation and curing. First, silver paste (01H-1803, Sryeo Electronic Paste Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) electrodes are precisely applied on both sides of the WSe2 material using a probe. The device is then cured at 70 °C for 2 min to ensure stable and reliable contact between the electrodes and the material.

- SrAl2O4 coating and post-treatment. SrAl2O4 powder is dissolved in ultrapure water and ultrasonically dispersed for 5 min to form a homogeneous suspension. The suspension is spin-coated onto the device surface at 1000 rpm for 60 s, using a spin coater. Finally, the device is baked at 100 °C for 1 min to remove the residual moisture. After confirming the uniformity of the coating under an optical microscope, the final WSe2-SrAl2O4 composite device is obtained.

2.3. Characterization

The synthesized 2D WSe2 was characterized through a suite of microscopic and spectroscopic techniques. The morphology was examined by optical microscopy (OM, Olympus BX43F, Shinjuku City, Japan) and atomic force microscopy (AFM, Bruker Dimension Icon, Billerica, MA, USA). Raman and photoluminescence (PL) spectra were performed on a Horiba iHR550 confocal Raman spectrometer (Horiba, iHR550, Loos, France) with 532 nm laser excitation.

2.4. Measurements

The electrical characterization was performed using a semiconductor parameter analyzer (Keithley 4200A-SCS, Solon, OH, USA) equipped with a probe station (Lake Shore CRX-VF, Westerville, OH, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

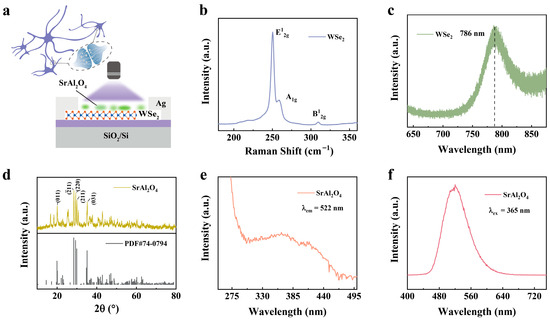

A UV-enhanced artificial optoelectronic synapse was constructed with WSe2 as the electronic synapses and SrAl2O4: 6% Eu, 4% Dy as the UV-responsive layer (Figure 1a and Figure S2). Layered WSe2 was grown by physical vapor deposition (PVD) [36]. The Raman spectrum of WSe2 presented three peaks centered around 250 cm−1, 260 cm−1 and 309 cm−1, which are ascribed to E12g and A1g modes and the interlayer interactions B12g of 2H WSe2, respectively (Figure 1b). The atomic force microscopy (AFM) image shows the thickness of 2H WSe2 is 1.6 nm (Figure S3), indicating bilayer WSe2 for this optoelectronic synapse, consistent with the interlayer interactions B12g. The luminescence spectra showed a peak at 786 nm (Figure 1c), agreeing with the bandgap of bilayer 2H WSe2 [37]. The XRD patterns of the SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ phosphor were matched very well with the patterns of the monoclinic phase (Figure 1d), revealing the pure phase of SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ phosphor. The specific parameters are listed in Table S2. Excitation spectra of the SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ phosphor were detected, which provided a broadband luminescence centered around 380 nm (Figure 1e), suggesting the absorption potential of broadband UV for electronic synapses [38]. The luminescence spectra of SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ phosphor displayed a broad band around 522 nm [39], fitting well with the absorption of 2H WSe2 and implied an enhanced UV response in WSe2-SrAl2O4 optoelectronic synapses (Figure 1f).

Figure 1.

Structure and optical properties of WSe2-SrAl2O4 device. (a) Schematic structure of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device. (b) Raman spectrum of WSe2. (c) PL spectrum of WSe2. (d) XRD patterns of the SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ phosphor. Excitation (e) and emission (f) spectra of the SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ phosphor.

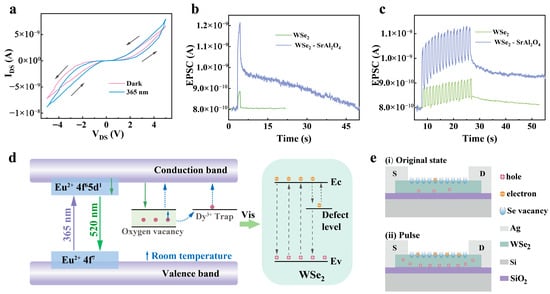

The output curve of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device was first measured to evaluate the UV synaptic potential (Figure 2a). The output curve showed a nonlinear characteristic, indicating Schottky contact between the WSe2 and Ag electrodes. The corresponding energy-level diagram of the WSe2/Ag contact is provided in Figure S4. The loop scan of the source–drain voltages showed a hysteresis window, revealing the potential of synaptic memory due to incompletely released trapped electrons in traps of 2H WSe2 or defects at interface between WSe2 and SiO2 [40]. Upon excitation at 365 nm, the output curve of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device exhibited a larger enhanced current and a large hysteresis window, originating from the strong absorption of SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ phosphor and radiation reabsorption from SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ to WSe2 (Figure 2d). The UV photons were absorbed by SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ and pumped the electrons from the valence band to the conduction band upon excitation at 365 nm, followed by relaxing to the 5d state of Eu2+ by multiphonon relaxation. The populated 5d state of Eu2+ gave a green luminescence band around 522 nm with the transition from the 5d to 4f state of Eu2+. The green luminescence was reabsorbed by WSe2 and pumped the electrons of WSe2 from the valence band to the conduction band, resulting in a larger photogenerated carrier concentration and enhanced current. The large hysteresis window was also originated from the larger current, which suggest that defect states captured a large number of electrons and that there was a long release time of the captured electrons. Therefore, the larger enhanced current and hysteresis window of the output curves of WSe2-SrAl2O4 device suggested a good UV synaptic potential.

Figure 2.

Output curves and EPSC of WSe2-SrAl2O4 device excited by 365 nm. (a) Output hysteresis curves of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device with and without excitation at 365 nm. (The arrows indicate the voltage sweep direction.) (b) EPSC generated by single pulse in WSe2 and WSe2-SrAl2O4 devices excited at 365 nm with the power intensity (P) at 7.2 mW/cm2 and pulse width (W) at 1 s. (c) EPSC evoked by a sequence of pulses in WSe2 and WSe2-SrAl2O4 devices with pulse numbers (N) at 16 (λ = 365 nm, P = 7.2 mW/cm2, W = 0.5 s, Δt = 0.5 s). (d) Microscopic mechanism of UV-enhanced photoresponse of WSe2-SrAl2O4 device. (e) Working mechanism of WSe2-SrAl2O4 device and the electron capture by Se vacancies or defects at the interface between WSe2 and SiO2 under (i) initial state and (ii) single pulse.

To confirm the UV synaptic performance, the EPSC of the WSe2 and WSe2-SrAl2O4 devices were assessed via triggering by single and multi-pulses (Figure 2b,c). When excited by a single pulse at 365 nm with the power intensity (P) at 7.2 mW/cm2 and pulse width (W) at 1 s, an EPSC was generated, because the photogenerated carriers, accompanied by parts of electrons, were captured in the defects in WSe2 or the interface between WSe2 and SiO2 (Figure 2e). After removing the pulse, the EPSC reduced rapidly first and then relaxed to its initial state after 4.7 s. The rapid reduction is connected to the fast recombination of photogenerated carriers. The slow relaxation is ascribed to the tardy release of captured electrons. What is exciting is that the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device presented a higher EPSC and a slower decay time when excited by the same pulse (Figure 2b). The EPSC was almost 4 times higher than that from 2D WSe2 owing to the super-sensitive absorption of the SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ phosphor and radiation reabsorption from SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ to WSe2. The decay time was explored to 45.6 s, which is almost 9.7 times longer than those from a WSe2 device, and originated from the long persistence of SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+. At the same time, the enhanced EPSC and decay time were obtained by a sequence of pulses in the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device compared to the WSe2 device (Figure 2c), which reconfirmed the ability to regulate the synaptic plasticity.

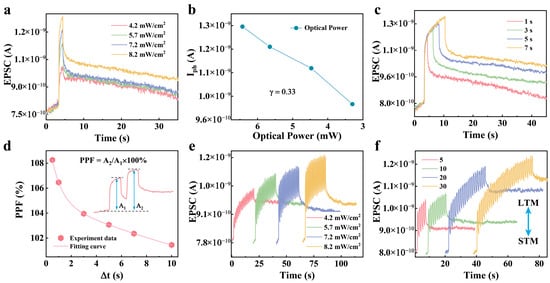

The synaptic plasticity of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device was modulated by power densities, pulse widths, pulse intervals, and pulse numbers (Figure 3). The EPSC increased significantly with increasing power densities from 4.2 mW/cm2 to 8.2 mW/cm2 and pulse widths from 1 s to 7 s (Figure 3a,c). The growing EPSC was ascribed to the augmented photogenerated carriers, which also induced a larger number of captured electrons in defects. In addition, the slower release of captured electrons in defects after removing the pulse led to a longer recovered time with increasing power densities and pulse widths. Further, the photocurrent obtained at different optical powers in Figure 3a was fitted using a power-law model, yielding a weak capture coefficient (γ) [41] and establishing a relationship between responsivity (R) and optical power [42]. The calculated γ ≈ 0.33 (<1) confirms the presence of significant trap effects in the device (Figure 3b), while R also shows an increasing trend with optical power (Figure S5). This occurs, because at low optical power, carriers are captured by defects, resulting in lower responsivity. As the optical power increases, the traps gradually become saturated, which improves the carrier transport efficiency and, correspondingly, enhances the responsivity. This mechanism is consistent with that described in Figure 2. Then, the PPF index was measured with varying pulse intervals (Figure 3d). The PPF index was calculated as [43]

where A1 and A2 represent the EPSCs triggered by the first and second pulses, respectively. The PPF index can be fitted by a double-exponential function [44]:

where C is a constant, B1 and B2 correspond to the initial magnitudes of rapid and slow decay, and τ1 and τ2 are the respective relaxation time constants. Fitting of the results shows 0.80 s and 20.65 s for time constants τ1 and τ2, respectively. The order-of-magnitude difference between the two time constants is similar to the synaptic performance of organisms [45]. In addition, the synaptic plasticity of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device was also regulated successfully by multiple pulses with different pulse counts and densities (Figure 3e). Further, the transition from STM to LTM was realized easily by increasing the pulse count from 5 to 30 at 365 nm (Figure 3f). The gradual decay of EPSC after the termination of the UV pulses represents an optical habituation or erasing process of the synaptic weight, analogous to the natural forgetting behavior observed in biological synapses.

Figure 3.

UV synaptic plasticity of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device. (a) EPSC triggered by a single 365 nm pulse (W = 1 s) at varying power densities. (b) Variation in photocurrent with optical power. (c) EPSC modulated by a single 365 nm pulse with different widths at a power density of 7.2 mW/cm2. (d) PPF index as a function of pulse interval. Illustration: EPSC response to paired pulses (P = 7.2 mW/cm2, W = 1 s, Δt = 0.5 s). (e) LTP induced by 16 consecutive optical pulses at different power densities (W = 0.5 s, Δt = 0.5 s). (f) EPSC triggered by 5, 10, 20, and 30 light pulses (P = 5.7 mW/cm2, W = 0.5 s, Δt = 0.5 s).

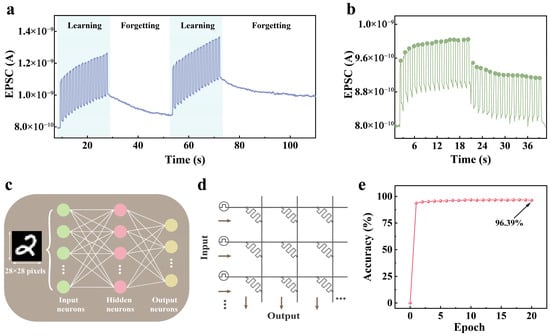

Furthermore, human learning behavior was also simulated based on the WSe2-SrAl2O4 UV synapse (Figure 4a). The first learning was imitated by 16 pulses, with the EPSC increasing to 1.3 × 10−9 A from 7.9 × 10−10 A. Then, the forgetting process began and lasted for 25 s, followed by a relearning process with the same triggering conditions. When the seventh pulse was applied, the EPSC rose to 1.3 × 10−9 A, which was the same outcome as for the first learning process. After continuous triggering with nine subsequent pulses, the EPSC rose to 1.4 × 10−9 A, similar to relearning reinforcement behavior. Later, the forgetting process began again. After a 35 s re-forgetting process, the EPSC still remained higher than the first forgetting value, analogous to the forgetting time of an organism. The learning–forgetting–relearning sequence clearly illustrates the habituation behavior of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 synapse. The EPSC increases during the first learning and then decreases during the subsequent forgetting period. Subsequently, the EPSC recovers more rapidly during relearning, indicating that the device can both store and gradually erase synaptic information. Furthermore, the synaptic behavior of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device can be modulated by 532 nm and 365 nm light illumination. As shown in Figure 4b, 16 pulses of 532 nm light (P = 5.7 mW/cm2, W = 0.5 s, Δt = 0.5 s) were applied first, followed by 16 pulses of 365 nm light (P = 5.7 mW/cm2, W = 0.5 s, Δt = 0.5 s). These results, combined with the modulation of the synaptic behavior by visible light shown in Figure S6, collectively demonstrate that the device can achieve active non-destructive optical synaptic weight erasure in addition to the passive forgetting mechanism.

Figure 4.

Human learning behavior and handwritten digit recognition by ANN-based behavior WSe2-SrAl2O4 synaptic weights. (a) Learning behavior simulated by 365 nm light pulses (P = 5.7 mW/cm2, W = 0.5 s, Δt = 0.5 s). (b) Conductance changes modulated by 532 nm and 365 nm (P = 5.7 mW/cm2, W = 0.5 s, Δt = 0.5 s). (c) Schematic of the three-layer ANN used to recognize MNIST images. (d) Cross-switch array structure. (e) Recognition accuracy from the MNIST simulation for each training.

A three-layer artificial neural network (ANN) was built (Figure 4c) to evaluate the neuromorphic computing capability of the device, consisting of 784 input neurons, 300 hidden neurons, and 10 output neurons. The synaptic weights between layers were extracted from LTP/LTD characteristics and implemented in a crossbar-array simulator (Figure 4d labeled point). When tested on the MNIST dataset, the network achieved a recognition accuracy of 96.39% after 20 training epochs (Figure 4e), demonstrating the device’s potential for practical neuromorphic classification tasks.

4. Conclusions

A UV-enhanced artificial optoelectronic synapse was achieved in a WSe2-SrAl2O4 device. SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ phosphor was used to sensitize UV light and transfer to visible light by a downshift process, followed reabsorbing visible light by 2H WSe2. The EPSC of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 synapse was increased 4 times more than that from 2D WSe2, owing to the super-sensitive absorption of SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ phosphor. The decay time was explored to 45.6 s, which is almost 9.7 times longer than with the WSe2 device. The excellent UV sensitivity and decay time promoted the good regulation of the synaptic plasticity of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device by power densities, pulse widths, pulse intervals, and pulse numbers. In addition, the transition from STM to LTM was achieved easily by increasing the pulse width to 7 s or the pulse number to 20. Perfect human learning behavior was realized, with a forgetting time as long as 25 s. Furthermore, the synaptic weight of the WSe2-SrAl2O4 device was applied to recognize handwritten digits with the accuracy as high as 96.39%. Our strategy provides a new road for a UV optoelectronic synapse based on TMDCs and presents a potential application in neuromorphic computing.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nano15241890/s1, Figure S1: Schematic of WSe2 growth system by PVD method; Figure S2: Optical image of WSe2-SrAl2O4 device; Figure S3: Characterization of 2D WSe2 materials AFM (a) and SEM (b); Figure S4: Band structure diagram of WSe2/Ag; Figure S5: Variation in responsivity with optical power; Figure S6: Synaptic plasticity of the WSe2 devices triggered by 532 nm; Table S1. Comparison of TMDCs-based UV optoelectronic synapses with this work; Table S2. Microstructural parameters of sample SrAl2O4: 6% Eu2+, 4% Dy3+ [46].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.S. and P.C.; material synthesis and device fabrication, Q.S.; synaptic measurements and data analysis, Q.S. and X.L.; characterization, Q.S. and N.Z.; handwritten digit recognition, C.C.; writing and review, P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (No. 2025GXNSFAA069357), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52472153), the special funding for Guangxi Bagui Youth Scholars (Ping Chen), and the National Science and Technology Innovation Talent Cultivation Program (No. 2023BZRC016).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pei, J.; Deng, L.; Song, S.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; Wang, G.; Zou, Z.; Wu, Z.; He, W.; et al. Towards Artificial General Intelligence with Hybrid Tianjic Chip Architecture. Nature 2019, 572, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yang, Y.; Nie, S.; Liu, R.; Wan, Q. Electric-Double-Layer Transistors for Synaptic Devices and Neuromorphic Systems. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 5336–5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuro-Inspired Computing Chips|Nature Electronics. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41928-020-0435-7 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Deng, W.; Yan, X.; Wang, L.; Yu, N.; Luo, W.; Mai, L. Two-Dimensional Materials Based Memtransistors: Integration Strategies, Switching Mechanisms and Advanced Characterizations. Nano Energy 2024, 128, 109861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, A.; Fu, Y.; Xue, G.; Liu, K.; Huang, S.; Xu, Y.; Yu, B. Two-Dimensional Materials Based Two-Transistor-Two-Resistor Synaptic Kernel for Efficient Neuromorphic Computing. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, R.S.; Georgiadou, D.G. 2D Transition Metal Dichalcogenides for Energy-Efficient Two-Terminal Optoelectronic Synaptic Devices. Device 2025, 3, 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Pan, J.; Gao, W.; Wan, B.; Kong, X.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, K.; Du, S.; Ji, W.; Pan, C.; et al. Anisotropic Carrier Mobility from 2H WSe2. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2108615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.L.; Yan, J.H.; Yang, Y.T.; Lu, Y.X.; Liu, N.; Chen, P.; Liu, X.F.; Qiu, J.R.; Xu, B.B. Achieving Enhanced Linear and Nonlinear Optical Absorption in a (PEA)2PbI4/WS2 Heterojunction by Efficient Energy Transfer. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 5877–5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Sun, Q.; Lu, Y.; Chen, P. X-Ray Irradiation Improved WSe2 Optical–Electrical Synapse for Handwritten Digit Recognition. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, C.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, N.; Lv, K.; Chen, Z.; He, Y.; Tang, H.; Chen, P. Near-Infrared Synaptic Responses of WSe2 Artificial Synapse Based on Upconversion Luminescence from Lanthanide Doped Nanoparticles. Inorganics 2025, 13, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, C.; Yu, Z.; He, Y.; Chen, X.; Wan, Q.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, D.W.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; et al. A MoS2 /PTCDA Hybrid Heterojunction Synapse with Efficient Photoelectric Dual Modulation and Versatility. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1806227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, C.; Zhao, X.G.; Xin, W.; Xie, X.; Liu, W.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y. Perceiving the Spectrum of Pain: Wavelength-Sensitive Visual Nociceptive Behaviors in Monolayer MoS2-Based Optical Synaptic Devices. ACS Photonics 2024, 11, 4578–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, D.; Moon, S.; Lee, E.; Kim, H.H. Co-Stimuli-Driven 2D WSe2 Optoelectronic Synapses for Neuromorphic Computing. Small 2025, 21, 2504024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Xing, X.; Wang, X.; Duan, R.; Han, S.T.; Tay, B.K. Integrated Bionic Human Retina Process and In-Sensor RC System Based on 2D Retinomorphic Memristor Array. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2406547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Deng, W.; Yu, N.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Luo, W. Low-Power Reconfigurable MoS2 /MoTe2 Optoelectronic Synapse for Visual Recognition. Nano Res. 2025, 18, 94907741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Hou, P. Self-Powered Polarized Photodetection and Low-Voltage Modulated Bidirectional Visual Synapse of Ta2NiS5/MoS2/Gr Vertical Heterojunction with Asymmetric Interface Modulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 57708–57718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zubair, A.; Xie, D.; Palacios, T. WSe2/Graphene Heterojunction Synaptic Phototransistor with Both Electrically and Optically Tunable Plasticity. 2D Mater. 2021, 8, 035034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Fu, J.; Ruan, H.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhuge, F.; Ma, Y.; et al. Tailoring Lithium Intercalation Pathway in 2D van Der Waals Heterostructure for High-Speed Edge-Contacted Floating-Gate Transistor and Artificial Synapses. InfoMat 2024, 6, e12599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Chen, Y.; Su, L.; Chen, H. Bioinspired Artificial Optoelectronic Synapse for Encrypted Communication Realized via a MoSe2 Based MIS Structural Photodiode. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 243, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Huo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yan, H.; Yu, J.; Cheng, L.; Fu, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; et al. Neuromorphic Tactile-Visual Perception Based on 2D ReS2/CIPS Heterojunction Artificial Synapse. Nano Energy 2025, 144, 111399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, Z.; Deng, W.; Yan, X.; Chen, F. Nonvolatile Memory and Neuromorphic Devices Based on the MoTe2/h-BN/Graphene Floating Gate Transistor. Appl. Mater. Today 2025, 46, 102908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Kazmi, J.; Nawaz, M.Z.; Moutaouakil, A.E.; Zhang, J.; Illarionov, Y.; Wang, Z. Interface Engineering in Van Der Waals Heterostructures: Enhancing Photodetector Efficiency through Structural and Functional Modifications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e16893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Gomez, A.; Duan, X.; Fei, Z.; Gutierrez, H.R.; Huang, Y.; Huang, X.; Quereda, J.; Qian, Q.; Sutter, E.; Sutter, P. Van Der Waals Heterostructures. Nat. Rev. Methods Primer 2022, 2, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Li, M.; Fu, S.; Neumann, C.; Li, X.; Niu, W.; Lee, Y.; Bonn, M.; Wang, H.I.; Turchanin, A.; et al. High-Throughput Synthesis of Solution-Processable van Der Waals Heterostructures through Electrochemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202303929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Wang, D.; Wang, P.; Meng, Y.; Fu, X.; Yan, H.; Meng, C. A Flexible Temperature Sensor with Ultrafast Response Speed and High Stability Achieved by Improving Substrate Thermal Conductivity and Radiative Cooling. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e12296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Cheon, G.J.; Lee, D.; Kim, I.S.; Won, U.; Lee, J.; Won, S.M.; Kang, J. Multicolor Optoelectronic Synapse Enabled by Photon-Modulated Remote Doping in Solution-Processed Van Der Waals Heterostructures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e14177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Lu, H.; Luo, D.; He, L.; Wei, W.; Yang, C.; Yuan, C.; Xu, Y.; Zeng, B.; Dai, L. Coordinatively Attaching an Ultra-Thin Boronate Ester Polymer Layer on the Surface of Monolayer MoS2 for Heterostructures with Widely Tunable Electronic and Optoelectronic Properties. Small 2025, e09929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roldán, R.; Silva-Guillén, J.A.; López-Sancho, M.P.; Guinea, F.; Cappelluti, E.; Ordejón, P. Electronic Properties of Single-Layer and Multilayer Transition Metal Dichalcogenides MX2 (M = Mo, W and X = S, Se). Ann. Phys. 2014, 526, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Winslow, D.; Zhang, D.; Pandey, R.; Yap, Y.K. Recent Advancement on the Optical Properties of Two-Dimensional Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS2) Thin Films. Photonics 2015, 2, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.K.; Yang, R.; Zhou, W.; Huang, H.M.; Xiong, J.; Gan, L.; Zhai, T.Y.; Guo, X. Photonic Potentiation and Electric Habituation in Ultrathin Memristive Synapses Based on Monolayer MoS2. Small 2018, 14, 1800079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Krishnaprasad, A.; Dev, D.; Martinez-Martinez, R.; Okonkwo, V.; Wu, B.; Han, S.S.; Bae, T.S.; Chung, H.S.; Touma, J.; et al. Multiwavelength Optoelectronic Synapse with 2D Materials for Mixed-Color Pattern Recognition. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 10188–10198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, G.; Min, S.Y.; Han, C.; Lee, S.; Ahn, H.; Seo, S.; Ding, F.; Kim, S.; Jo, M. Atomically Thin Synapse Networks on Van Der Waals Photo-Memtransistors. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2203481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zou, G.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, B.; Huo, J.; Peng, J.; Sun, T.; Liu, L. MoS2/ZnO-Heterostructured Optoelectronic Synapse for Multiwavelength Optical Information-Based Sensing, Memory, and Processing. Nano Energy 2024, 127, 109733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Xu, S.; Bao, X.; Zhao, L.; Liu, X.; Pan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Su, S.; et al. Photovoltage Junction Memtransistor for Optoelectronic In-Memory Computing. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 12763–12768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Yu, H.; Su, Z.; Luo, Y.; Memon, M.H.; Chen, W.; Kang, Y.; Sun, H. 2D/3D Integrated Phototransistor for Broadband Artificial Synaptic Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Photonics Conference (IPC), Rome, Italy, 10–14 November 2024; IEEE: Rome, Italy, 2024; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, P.; Duan, X.; Zang, K.; Luo, J.; Duan, X. Robust Epitaxial Growth of Two-Dimensional Heterostructures, Multiheterostructures, and Superlattices. Science 2017, 357, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanai, G.S.; Gupta, B.K. Spectroscopic Studies on CVD-Grown Monolayer, Bilayer, and Ribbon Structures of WSe2 Flakes. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 3102–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Zuo, S.; Huang, C.; Tan, Z.; Lu, F.; Liang, Y.; Mo, X.; Lin, T.; Cao, S.; Qiu, J.; et al. Tunable Excitation Polarized Upconversion Luminescence and Reconfigurable Double Anti-Counterfeiting from Er3+ Doped Single Nanorods. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2023, 11, 2301126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.P.; Chen, P.; Liang, Y.; Mo, X.M.; Pan, C.F. Regulated Polarization Degree of Upconversion Luminescence and Multiple Anti-Counterfeit Applications. Rare Met. 2024, 43, 2172–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High-Performance Artificial Synapse Based on CVD-Grown WSe2 Flakes with Intrinsic Defects|ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acsami.3c00417 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Vashishtha, P.; Dash, A.; Walia, S.; Gupta, G. Self-Bias Mo–Sb–Ga Multilayer Photodetector Encompassing Ultra-Broad Spectral Response from UV–C to IR–B. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 181, 111705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Yang, J.; Zhao, K.; Cui, A.; Zhou, J.; Tian, W.; Li, W.; Hu, Z.; Chu, J. High Responsivity and External Quantum Efficiency Photodetectors Based on Solution-Processed Ni-Doped CuO Films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 11797–11805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Hu, J.; Chen, Z.; Sun, Y.; Xie, D. Spatial Information Inference with Programmable 2D Retinomorphic Devices Enabling Dynamic Trace Perception Inspired by Bee Waggle-Dance Communication. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e16349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.; Kim, D.; Kim, N.; Hong, H.; Heo, C.Y.; Cho, W.; Yoo, H.Y.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Yang, H. Ferroelectric-Induced Phase Change Device with Polymorphic Mo1-xWxTe2 for Neuromorphic Computing. Small 2025, e05378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Huang, C.; Yang, M.; He, D.; Pei, Y.; Kang, Y.; Li, W.; Lei, C.; Xiao, X. Ultra-Low Power Consumption Artificial Photoelectric Synapses Based on Lewis Acid Doped WSe2 for Neuromorphic Computing. Small 2024, 20, 2406402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar Litoriya, P.; Kurmi, S.; Verma, A. Structural, Optical, Morphological and Photoluminescence Properties of SrAl2O4: Dy by Using Urea Fuel Combustion Method. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 66, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).