Abstract

Miniscrews are devices that allow for absolute skeletal anchorage. However, their use has a higher failure rate (10–30%) than dental implants (10%). To overcome these flaws, chemical and/or mechanical treatment of the surface of miniscrews has been suggested. There is no consensus in the current literature about which of these methods is the gold standard; thus, our objective was to carry out a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature on surface treatments of miniscrews. The review protocol was registered (PROSPERO CRD42023408011) and is in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. A bibliographic search was carried out on PubMed via MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Embase and Web of Science. The initial search of the databases yielded 1684 results, with 98 studies included in the review, with one article originating from the search in the bibliographic references of the included studies. The results of this systematic review show that the protocols of miniscrew surface treatments, such as acid-etching; sandblasting, large-grit and acid-etching; photofunctionalization with ultraviolet light; and photobiomodulation, can increase stability and the success of orthodontic treatment. The meta-analysis revealed that the treatment with the highest removal torque is SLA, followed by acid-etching. On the other hand, techniques such as oxidative anodization, anodization with pre-calcification and heat treatment, as well as deposition of chemical compounds, require further investigation to confirm their effectiveness.

1. Introduction

With the increasing use of dental implants to replace missing teeth, implants of different sizes have been manufactured to meet different clinical situations [1]. Unlike dental implants which are made up of two parts (the implant and the abutment), mini dental implants have a single-piece titanium screw with a spherical head to stabilize the prosthesis or a square prosthetic head for fixed applications instead of the classic abutment. Mini implants are smaller in diameter and are often used to stabilize dentures or as temporary anchorage devices in orthodontic treatment. They are typically around 1.0 to 2.0 mm in diameter and 6 to 10 mm in length, whereas conventional implants used in dentistry for replacing missing teeth are larger, usually ranging from 3.0 to 6.0 mm in diameter and 7 to 16 mm in length [2,3]. Orthodontic mini implants are solely used as temporary anchorage devices (TADs), providing absolute anchorage and aid in eliminating unwanted forces and deleterious tooth movements [4,5]. These devices were first described in 1997 by Kanomi [5]. The use of these systems makes it possible to perform movements that would otherwise be unachievable [6]. The use of miniscrews can be beneficial in a wide variety of orthodontic movements, such as retraction and intrusion of anterior and posterior teeth, mesialization or distalization of molars and elimination of undesirable spaces [7]. In turn, these movements will allow for the correction of deep bites, midline deviations and sagital discrepances and will help improve the Spee curve [4]. The use of TADs will ideally result in greater treatment efficacy due to the optimization of orthodontic movement. These particularities, together with their ease of use, the lack of the need for extensive surgery and an agreeable cost–benefit ratio, as well as their small size, are factors that contribute to therapeutic success and satisfaction for both patients and providers [4,5].

The stability of miniscrews is divided into two stages: primary and secondary. Primary stability is achieved by the mechanical retention of the device to the bone, and it varies according to the type of implant, mechanical characteristics, implantation condition and properties of the target bone. In the weeks following insertion, the stability of miniscrews varies according to the type of miniscrew, implantation method and properties of the target bone. In order to achieve this, it is vital to consider the characteristics of the bone, for example whether medullar or alveolar bone is present, the attributes of the implant surface and the timings of bone cell remodeling [5]. Similarly, an important characteristic of miniscrews which can influence their success is the material from which they are produced. Initially, the materials recommended for the manufacture of these devices were based on stainless steel, an alloy composed mainly of iron, nickel, chromium and carbon. With the evolution of materials and search for compounds that were more biocompatible, there was a paradigm shift, and today most of them are produced from titanium, with purity levels ranging from grade I to V [4,5].

As a result of its properties and close connection to the surrounding bone, the miniscrew has a lower loss of anchorage over time compared to other anchorage methods [8]. However, when compared to the devices from which they were initially derived, conventional dental implants, their failure rate is higher. Studies have reported that 10–30 percent of miniscrews fail, a figure that is significantly higher than the 10 percent of traditional implants [6,9,10]. The initial stability is often lacking in cases of inadequate cortical bone thickness. Furthermore, the loss of miniscrew stability can be attributed to inflammation or bone remodeling [10]. There is evidence, on the other hand, that more failures of these devices are reported in the mandible, although the literature is not in complete agreement. These results may be due, for example, to the higher density of the mandibular bone, causing higher insertion torque values, as well as necrosis due to excessive bone heating during placement and lower cortical bone production around the miniscrew [10].

A miniscrew is considered lost when it is no longer able to irreversibly anchor the fixed appliance, and thus is no longer resisting the forces created by reactions, leading to its removal and consequent need for replacement [10]. In its initial phase, loss can occur due to the device unscrewing, a situation that can be prevented by improving the technique and properties of the miniscrew [6]. Its loss is not, however, a one-off occurrence. This perpetuates complications not only in soft tissue, but also in hard tissue, namely root damage to adjacent teeth, perforation of the maxillary sinus, inflammation of the soft tissues and hypertrophy of the peripheral mucosa [11]. In order to overcome the limitations described above, surface treatment techniques for orthodontic miniscrews have been suggested. In general, these strategies aim to improve the anchoring properties so that early loss of these devices, being of mechanical and/or chemical origin, can be prevented. These techniques are intended to improve the topography of the coils and their surface roughness, promoting good adhesion and cell interaction. Certain treatments may also provide decontamination of the miniscrew length [12,13].

The miniscrew can be produced with an untreated or altered surface, maintaining only the properties of the chosen titanium alloy. In order to modify the surface, there are techniques described in the literature that aim to meet the requirements explained above, such as microgrooving, sterilization, surface anodization, sandblasting and plasma ion implantation, as well as ultraviolet light treatment [14]. Table 1 describes the main advantages and disadvantages of the surface treatments most cited in the literature.

Table 1.

Summary of advantages and disadvantages of the most-cited surface treatments.

One of the most used surface treatments to date is acid-etching of the surface of miniscrews. It primarily submerges the miniscrews in an acid, such as phosphoric acid, to improve roughness and resistance to compressive forces [19,20]. Additionally, another surface treatment commonly described is sandblasting, large-grit and acid-etching (SLA). It takes advantage of the properties of an acid and tallies it to particle abrasion with aluminium oxide, for example, to better cultivate cell adhesion to the miniscrew and augment its mechanical stability [21,22]. In recent years, these techniques have been widely investigated, but there is no consensus on which method is the gold standard. The authors, therefore, set out to carry out a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature on possible surface treatments for miniscrews, comparing their characteristics and protocols and evaluating their influence on clinical stability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol

The protocol for this systematic review was registered on the PROSPERO platform, having received approval with the registration number CRD42023408011. Its organization and methodology followed the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) [23], which resulted in the following PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome) question: “What is the effect of surface treatment on the mechanical stability of miniscrews in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment?”.

2.2. Study Strategy and Selection

After obtaining the PICO question, a comprehensive literature search was performed in the following databases: PubMed (via MEDLINE), Cochrane Library (Trials), Embase and Web of Science (all databases). For each database, different variations of the same search key were used in order to respect the particularities of each platform.

In all searches, the language filter was applied to include only studies in English, Portuguese, Spanish and French. The last search carried out in all databases was performed on 19 November 2023, by two researchers, independently. Additionally, the investigation included searching ProQuest (Database, Ebooks and Technology for research), HSRProj and Onegrey, as well as a manual search of the bibliographic references of included studies. Supplementary Materials, Table S1 summarizes the search strategies used. To better manage the results obtained, the bibliographic reference tool Endnote Web (version 21, Clarivate Analytics) was used.

Subsequently, studies eligible for review and analysis were selected. From the results obtained, all duplicate studies were first removed using the Find duplicates tool on EndNote Web. After extraction, three independent reviewers scrutinized the remaining studies (A.L.F., R.T., I.F.), choosing only those in compliance with the established eligibility criteria. Firstly, the selection was carried out according to the title and abstract, and, finally, the residual studies were verified, analyzing their text in full. In case of any doubt or disagreement, a fourth reviewer was contacted and consulted (F.V.).

The primary outcome was defined as the mechanical stability of the miniscrews. However, the secondary outcomes were as follows: tooth movement, periodontal health, pain and discomfort felt by the patient, possible changes in speech and aesthetics and, finally, the analysis of the cost of the treatment.

The following inclusion criteria were defined: in-vitro studies; in-vivo studies; ex-vivo studies; randomized, non-randomized, case-control and cohort clinical studies; and studies that evaluated the stability of miniscrews as the primary outcome. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria applied were as follows: editorials or books and book chapters; studies with incomplete information; case report/clinical case series; and descriptive studies.

2.3. Data Extraction

For each study included, three independent investigators (A.L.F., R.T., I.F.) extracted the following information: authors, year of publication, study design (in vitro, in vivo, ex vivo or clinical), sample characteristics such as species (if applicable), sex and age, sample size, test group and control group, material and protocol (application time and dose) used for treatment, outcomes evaluated, type of intervention evaluation, main follow-up period(s), results and conclusions.

A first reviewer performed data extraction and synthesis (A.L.F.). This condensation was then reviewed and, when necessary, corrected, by two other researchers (R.T. and I.F.), with a fourth reviewer being contacted in case of doubts or disagreement (F.V.).

2.4. Quality Assessment

In order to assess the quality of the methodology of the studies included in this review, we took advantage of several already validated tools in order to assess the risk of bias of each of them. Two reviewers (A.L.F. and R.T.) independently analyzed the quality of the studies, with a third (I.F.) mediating any disagreements.

With regard to in vitro studies, these were evaluated using Faggion Jr.’s guidelines for reporting pre-clinical studies related to dental materials [24]. Equivalently, the SYRCLE tool (Systematic Review Center for Laboratory Animal Experimentation, Netherlands) was used when analyzing the risk of bias of in vivo studies [25]. Finally, for clinical studies, the Cochrane guidelines were used (RoB-2 and ROBINS-I tools) [26,27].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The objective of this study is to assess and compare surface treatments applied to miniscrews, specifically examining SLA (sandblasting, large-grit and acid-etching) and AE (acid-etching). The evaluation criteria include removal torque (RTV), insertion torque (ITV), success rate (SR) and bone contact interface (%BIC). The analysis encompasses studies conducted in patients, along with in vivo studies, and incorporates meta-analyses of the gathered data.

In the analysis, the primary outcome measures were the raw mean and odds ratio, utilizing random-effects models for data processing. To assess the heterogeneity among the included studies, both the Q-test for heterogeneity and the I² statistic were calculated, offering insights into the variability of effect sizes across studies. Each meta-analysis was summarized through the creation of a forest plot. The statistical procedures were executed using the “metafor” package in R (version 4.4-0, Wolfgang Viechtbauer), and the plots were generated using MS® Excel® (version 16.16.27, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

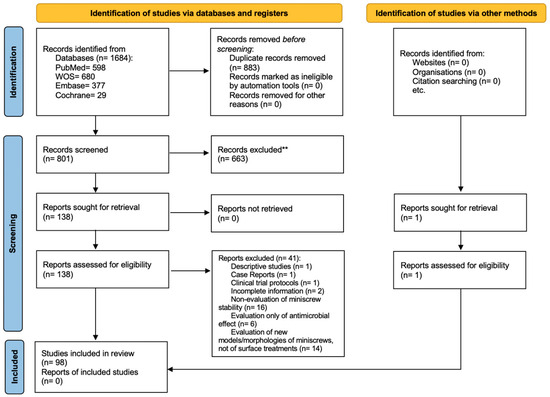

The initial search was conducted in various databases and resulted in 1684 studies. After the identification and removal of the 883 duplicates, the titles and abstracts were read and 633 studies were excluded. Subsequently, 138 potentially relevant references were read in full. The complete reading resulted in the exclusion of 41 additional articles. In parallel, after searching the references of the results obtained in the search in the databases, one gray literature article was included. Thus, 98 studies were included in this systematic review. The process of identification, screening and eligibility is summarized in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart diagram.

3.2. Included Studies Characteristics

The present systematic review included 41 in vitro studies, 56 studies in vivo and 16 clinical trials (11 randomized and 5 non-randomized). The characteristics and results of the previously mentioned studies are described below.

3.2.1. In Vitro Studies

The most commonly mentioned surface treatments were as follows: oxidative anodization in 8 studies; SLA (sandblasting, large-grit and acid-etching) in 5 studies; AE (acid-etching) in 6 studies; photofunctionalization in 3 studies; deposition of different fluids, solutions and chemical compounds in 11 studies; and different sterilization methods in 11 studies.

In order to assess the effect of the surface treatments, follow-up times ranged from 12 h 20 to 10 [28] and 12 weeks [29]. The in vitro studies were published between 2010 [30] and 2023 [31,32,33,34]. Table 2 presents the characteristics and results of the in vitro studies.

Table 2.

Summary of extrapolated data from included in vitro studies.

3.2.2. In Vivo Studies

The surface treatment most used in this study design was the deposition of different fluids, solutions and chemical compounds (n = 13), followed by photofunctionalization/photobiomodulation (n = 10), SLA (n = 10), oxidative anodization (n = 10), acid-etching (n = 7) and novel auxiliary devices (n = 1).

The sample of animals included ranged from 2 [45] to 144 [67] and these studies were performed between 2003 [68] and 2023 [31,69,70,71].

Table 3 presents the characteristics and results of the in vivo studies.

Table 3.

Summary of extrapolated data from included in vivo studies.

3.2.3. Clinical Trials

These studies were published between 2008 [16,73] and 2023 [110,111]. The number of patients included varied mostly between 20 and 40 patients, except in four studies that included 8, 9, 13 and 17 participants [14,111,112,113].

As far as randomized clinical trials are concerned, the surface treatments tested were photofunctionalization using ultraviolet light and LED (light emitting diode) in one study each and low-intensity laser photobiomodulation (LLLT) in two studies. Additionally, SLA and acid-etching were evaluated in four studies. One study researched the effects of precipitation of hydroxyapatite.

The results obtained were reported after follow-up times ranging from 3 days [114,115] to 22 months [73]. Table 4 presents the characteristics and results of the clinical trials.

Table 4.

Summary of extrapolated data from included clinical trials.

3.3. Studied Outcomes and Chosen Tests

The majority of the included studies assessed stability as the primary outcome using various methods: measurement of insertion, removal and fracture torques; RFA (resonance frequency analysis); analysis of contact between bone and miniscrews; histological methods and electron microscopy; assessment of mobility using the Periotest; and periodontal changes. On the other hand, factors such as biocompatibility, the patient’s perception of pain (using the NRS-11 pain scale), tooth movement through comparisons between study models and, finally, the surface characteristics of the miniscrews created by surface treatment were also evaluated. In general, outcomes were assessed using experimental groups subjected to one or more surface treatments compared to an untreated control group.

3.4. Risk of Bias

The risk of bias analysis of the clinical trials, in vitro and in vivo studies is shown in Supplementary Materials, Tables S2–S5.

With regard to randomized clinical trials, the majority of studies had a low risk of bias, with the exception of four articles. Two studies show concerns in measuring their outcomes [114,115] and one study in deviations from the intended outcome [21]. On the other hand, one trial was classified as having a high risk of bias due to the non-referencing of the randomization method [21].

With regard to in vivo and in vitro studies, the majority of studies presented a high risk of bias. The main reasons for bias were the lack of randomization and blinding in the allocation of treatments, lack of blinding in the measurement of outcomes, failure to mention the limitations of the studies and the availability of their protocols.

3.5. Meta-Analysis

The analysis underwent an initial meticulous selection process in which priority was given to those articles containing indispensable information pertaining to the control and test groups. In this meta-analysis, of the 98 studies of the systematic review, 13 were included.

The emphasis was particularly on data related to the mean and standard deviation in quantitative variables such as RTV, ITV, BIC and SR. For dichotomous variables, the focus was directed towards the proportion of event occurrence in both groups, with special attention to the success rate (SR). It is noteworthy that, among the scrutinized treatments, only the SLA and AE groups exhibited a sufficient number of elements to perform a comprehensive meta-analysis. The ensuing results from the diverse meta-analyses conducted are now presented with clarity and visual coherence through forest plots.

3.5.1. Clinical Studies

Regarding clinical studies, it was possible to carry out four meta-analyses.

The calculated mean difference in removal torque between the control and SLA groups is −1.22, signifying a greater value in the SLA group. Notably, the observed difference attains statistical significance, as evident from the confidence interval (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of RTV (removal torque value) in RCTs using SLA surface treatmen: blue color- results of individual studies; red color- meta-analysis result [12,18].

Concerning the success rate, an inclination towards improvement is noted in the test group (SLA), characterized by an average odds ratio of 2.08. Nonetheless, statistical significance was not reached (CI95% [0.58; 7.54]) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of SR (success rate) in RCTs using SLA surface treatment: blue color- results of individual studies; red color- meta-analysis result [13,18].

The insertion torque values exhibit similarity between the two groups, with a mean difference of −0.05 (95% CI [−0.44; 0.34]) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of ITV (insertion torque value) in RCTs using SLA surface treatment: blue color- results of individual studies; red color- meta-analysis result [12,18].

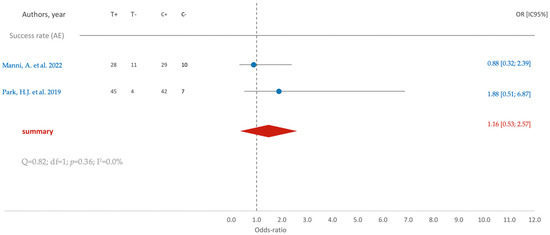

Regarding the success rate associated with the acid-etching (AE) surface treatment, a subtle inclination toward improvement is observable, as indicated by an average odds ratio of 1.16. However, the confidence interval (95% CI [0.53; 2.57]) reveals a lack of statistical significance (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of SR (success rate) in RCTs using AE surface treatment: blue color- results of individual studies; red color- meta-analysis result [12,18].

3.5.2. In Vivo Studies

Figure 6 shows that similar to previous observations, the removal torque is higher in the test group (SLA), as is evident from the mean difference (−1.09), which achieves statistical significance, as affirmed by the confidence interval (95% CI [−1.55; −0.63]).

Figure 6.

Comparison of RTV (removal torque value) using SLA surface treatment: blue color- results of individual studies; red color- meta-analysis result [71,74,84,88].

The insertion torque within the SLA group, on average, appears slightly smaller (1.18) than that in the control group (Figure 7). However, upon considering the confidence interval (95% CI [−0.10; 2.46]), it is appropriate to conclude that there are no statistically significant differences between the groups.

Figure 7.

Comparison of ITV (insertion torque value) using SLA surface treatment: blue color- results of individual studies; red color- meta-analysis result [71,80,84].

Figure 8 illustrates that there are no statistically significant differences (95% CI [−1.09; 0.95]) between the control and SLA groups concerning the bone contact interface.

Figure 8.

Comparison of BIC (bone contact interface percentage) using SLA surface treatment: blue color- results of individual studies; red color- meta-analysis result [84,88].

For the acid-etching (AE) surface treatment, a parallel trend in removal torque is noted, mirroring that of the SLA group (Figure 9). The average removal torque value (RTV) is higher in the AE group, with statistically significant differences observed (95% CI [−2.24; −0.30]).

Figure 9.

Comparison of RTV (removal torque value) using AE surface treatment: blue color- results of individual studies; red color- meta-analysis result [49,99].

4. Discussion

The main differences between orthodontic miniscrews and conventional implants are the size, purpose, positioning, stability and duration of use. Orthodontic miniscrews are typically removed after they have served their purpose in orthodontic treatment, once the desired tooth movement has been achieved. Conventional implants are intended to create a direct structural and functional connection between living bone and the surface of a load-bearing artificial implant, providing long-term stable support for dental restorations [118]. As orthodontic miniscrews are designed for temporary use, they may not require as high a degree of stability as conventional implants [2,3]. Therefore, the complete osseointegration of TADs is a disadvantage that complicates the removal process; most of these devices are manufactured with a smooth surface, thus minimizing the development of bone growth and promoting soft tissue fixation under normal conditions [4]. Primary stability is obtained through mechanical retention of the screw in the bone, which depends on the design of the screw, bone properties and placement technique. On the other hand, secondary stability occurs due to the biological union of the screw with the surrounding bone and depends on bone characteristics, implant surface and bone turnover (cortical versus medullary bone). Over time, secondary stability increases while primary stability decreases [2,3]. Surface treatments on miniscrews can promote effective integration with the surrounding tissue, thus increasing the stability and longevity. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to summarize the surface treatments available on miniscrews in order to understand which ones could be adopted in the clinic and to compare their effectiveness in improving the outcomes proposed in the methods. A previous study, which included a meta-analysis of 14 studies, attempted to answer this question [12]. However, the results of this study should be assessed with caution as it presented several limitations in its methodology, namely: heterogeneity and poor quality of the animal studies included; observed faults in terms of methodology, such as the assessment of only one outcome; lack of coverage of in vitro and ex vivo studies; and the fact that PRISMA guidelines were not followed. Therefore, this review followed PRISMA guidelines in order to overcome the limitations previously described.

The SLA surface treatment was tested in all the types of studies reviewed. It involves the use of a beam of 100 to 500 µm aluminum oxide particles at constant pressure, followed by cleaning and then acid-etching [21,37,116]. Its aim is to increase surface roughness, promoting mechanical retention and greater integration into the underlying bone through greater fibroblast differentiation and proliferation [21]. This, in turn, allows for greater cell adhesion and protein absorption [21]. A previous study concluded that the action of SLA is related to improved cell adhesion to the surface in both healthy and diabetic individuals, the latter of which generally present with alterations in terms of bone metabolism [87]. This result was obtained through the excellent wettability of all the biological processes that derive from it, such as the increase in the exposed surface of the implant and the increase in bone–implant contact [22].

Acid-etching of surfaces, as shown in clinical studies included in our review, has been investigated through immersion in various acids in solution, such as nitric [102], sulfuric [20,93], phosphoric [39], hydrofluoric [28] and hydrochloric acid [38,50,93,102]. No studies were included that compared the effectiveness of the various types of acid. Two different studies have observed that surface acid-etching creates higher insertion torque values than untreated controls [93,117]. Fernandes et al. emphasized that insertion torque values are usually higher than removal torque values due to the predominance of compressive forces on insertion, which disperse with healing, reducing stability to a stable point [20]. With regard to the success rate of this treatment, Park et al. showed that although there is an increase in the number of successful miniscrews, this difference is not significant. These results are in line with those found in the literature on dental implants [117].

Additionally, some studies, mostly in vitro and in vivo, have proposed oxidative anodization protocols. This treatment is possible through immersing the miniscrew in an electrolytic solution at a constant voltage, promoting a potentiostatic system that creates a nanostructured titanium oxide matrix [90]. The anodization process can be carried out in one [105,109,119] or two steps [90,95,99], opening pores and depositing oxides, which provides the surface with nanoporosity that allows fibroblast proliferation [105]. These cells adhere to both flat and rough sites, confirming biocompatibility with the formation of dense bone tissue [105]. The data are in agreement with the systematic review and meta-analysis by Nagay et al., which aimed to understand the clinical efficacy of implants subjected to anodization used in different implant-supported prosthodontic solutions. It was concluded that the use of anodized implants as a form of prosthetic rehabilitation support is safe, but this method does not increase the effectiveness of the procedure [120].

APH treatment involves the use of anodization, followed by pre-calcification to incorporate calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite, and heating. The results of this protocol are more favorable than those of anodization, with higher values for removal torque and bone formation. It is suggested that hydroxyapatite formation is accelerated, which is crucial for achieving stability in clinical cases of lower quality bone [44]. However, the risk of bias in interpreting the results must be taken into account. In fact, the authors failed to promote conditions for the correct randomization of the interventions, as well as the blinding of the participants and the evaluators of the outcomes.

Using energy-radiating devices, it is possible to perform photofunctionalization using ultraviolet light [14,49,92,98,106], photobiomodulation using low-intensity lasers [51,81,84,89,114,115] and diode light emission [18,82,104].

In photofunctionalization using UV light, the miniscrew is placed in an ultraviolet chamber, such as TheraBeam SuperOsseo, for 12 to 15 min. The radiation imparts superhydrophilicity to the surface, with increased stability and improved values for mobility, bone contact, resistance to lateral pressure and removal torque [14,49,92,98,106]. In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Dini et al. showed similar results regarding the osseointegration and stability of conventional dental implants subjected to photofunctionalization using ultraviolet light in in vivo models. There was an improvement in osseointegration after the initial healing period through an increase in measured bone contact and cohesion strength, although the high risk of bias of the studies included in this publication, as well as the limited inclusion of study designs (animal models), should be noted [121].

Photobiomodulation can be carried out by laser emission at low wavelengths (635 to 1064 nm). Flieger et al. and Matys et al. used 635 nm and 808 nm lasers, respectively, and assessed stability and pain perception. They observed lower mobility values in the treated groups and no significant differences in the pain perception questionnaires [114,115]. However, the interpretation of pain perception in these studies raises some concerns when assessing the risk of bias, due to its subjectivity.

With regard to sterilization procedures, it was found that they do not lead to a decrease in stability due to previous use or sterilization [43], nor do they have a pronounced effect on fracture resistance [35]. The manufacturer of the miniscrew is the most differentiating factor in resistance [35]. Dry heat sterilization, which interfered with the mechanical properties of miniscrews, is noteworthy [63].

Regarding the meta-analysis, it was only possible to carry out this analysis for two surface treatments: SLA and acid-etching. The results of the meta-analysis found that both methods present enhanced attachment of the miniscrews, suggesting a better result for SLA than for acid-etching (odds ratio for the success rate 2.08 and 1.16, respectively). Despite the insertion torque in SLA treatment showing that the surface treatment of the miniscrews likely does not exert a noticeable impact on the initial attachment difficulty to the bone, the outcome of in vivo studies about the removal torque is higher in the SLA group, reinforcing the consistency of findings with prior results derived from RCT studies.

Reflecting on the large number of in vivo and in vitro studies that have been reviewed, although they reach conclusions that are mostly in agreement, they incur bias associated with blinding and allocation, as well as randomization. It is therefore recognized that the experience of the researchers, clinicians and collaborators involved in carrying out the different studies may have influenced the assessment of the results created. Future studies should evaluate the effectiveness of surface treatments with other variables such as screw designs, surface treatment protocols (e.g., acid concentration, composition, treatment time), implantation sites and animal models that can affect RTV, ITV and BIC.

5. Conclusions

Miniscrew surface treatments such as acid-etching; sandblasting, large-grit and acid-etching; photofunctionalization with ultraviolet light; and photobiomodulation were tested following well-defined and reliable protocols for increasing stability and the success of orthodontic treatment. These treatments can be applied in clinical orthodontic practice to enhance the effectiveness of miniscrews. Techniques such as oxidative anodization, anodization with pre-calcification and heat treatment, as well as deposition of chemical compounds, should be studied further, preferably in randomized, controlled clinical studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jfb15030068/s1, Table S1: Search Strategies/Phrases; Table S2: Assessment of Risk of Bias for Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials; Table S3: Assessment of Risk of Bias for Non-Randomized Clinical Trials; Table S4: Assessment of Risk of Bias for In vivo Studies; Table S5: Assessment of Risk of Bias for in vitro studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.F. and F.V.; methodology, R.T., C.M.M. and F.C.; validation, A.B.P., C.N. and C.M.M.; formal analysis, F.C.; investigation, A.L.F., R.T. and I.F.; resources, F.I. and M.S.; data curation, F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L.F. and R.T.; writing—review and editing, M.P.R. and I.F.; visualization, M.S., C.N. and A.B.P.; supervision, I.F.; project administration, F.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al-Johany, S.S.; Al Amri, M.D.; Alsaeed, S.; Alalola, B. Dental Implant Length and Diameter: A Proposed Classification Scheme. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 26, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, J.C.; Suarez, F.; Chan, H.-L.; Padial-Molina, M.; Wang, H.-L. Implants for Orthodontic Anchorage: Success Rates and Reasons of Failures. Implant. Dent. 2014, 23, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upendran, A.; Gupta, N.; Salisbury, H.G. Dental Mini-Implants. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, M.A.; Tarawneh, F. The Use of Miniscrew Implants for Temporary Skeletal Anchorage in Orthodontics: A Comprehensive Review. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endodontology 2007, 103, e6–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proffit, R.F.; Larson, E.; Sarver, M.D. Contemporary Orthodontics, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, K.; Mitchell, B.; Sakamaki, T.; Hirai, Y.; Kim, D.-G.; Deguchi, T.; Suzuki, M.; Ueda, K.; Tanaka, E. Mechanical Stability of Orthodontic Miniscrew Depends on a Thread Shape. J. Dent. Sci. 2022, 17, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasoria, G.; Kalra, A.; Jaggi, N.; Shamim, W.; Rathore, S.; Manchanda, M. Miniscrew Implants as Temporary Anchorage Devices in Orthodontics: A Comprehensive Review. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2013, 14, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, M.A.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Zogakis, I.P. Clinical Effectiveness of Orthodontic Miniscrew Implants: A Meta-Analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.; Kuroda, S.; Yasue, A.; Horiuchi, S.; Kyung, H.-M.; Tanaka, E. Torque Ratio as a Predictable Factor on Primary Stability of Orthodontic Miniscrew Implants. Implant. Dent. 2014, 28, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, S.N.; Zogakis, I.P.; Papadopoulos, M.A. Failure Rates and Associated Risk Factors of Orthodontic Miniscrew Implants: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2012, 142, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, A.L.; Rustico, L.; Longo, M.; Oteri, G.; Papadopoulos, M.A.; Nucera, R. Complications Reported with the Use of Orthodontic Miniscrews: A Systematic Review. Korean J. Orthod. 2021, 51, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thomali, Y.; Basha, S.; Mohamed, R.N. Effect of Surface Treatment on the Mechanical Stability of Orthodontic Miniscrews. Angle Orthod. 2022, 92, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Lee, S.-J.; Cho, I.-S.; Kim, S.-K.; Kim, T.-W. Rotational Resistance of Surface-Treated Mini-Implants. Angle Orthod. 2009, 79, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampurawala, A.; Patil, A.; Bhosale, V. Bone-Miniscrew Contact and Surface Element Deposition on Orthodontic Miniscrews After Ultraviolet Photofunctionalization. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2020, 35, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratu, D.C.; Popa, G.; Petrescu, H.; Karancsi, O.L.; Bratu, E.A. Influence of Chemically-Modified Implant Surfaces on the Stability of Orthodontic Mini-Implants. Rev. Chim. 2014, 65, 1222–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Chaddad, K.; Ferreira, A.H.; Geurs, N.; Reddy, M.S.; Chaddada, A.H.F.K.; Bueno, R.C.; Basting, R.T.; Jung, S.-A.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, D.-W.; et al. Influence of Surface Characteristics on Survival Rates of Mini-Implants. Angle Orthod. 2008, 78, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manni, A.; Drago, S.; Migliorati, M. Success Rate of Surface-Treated and Non-Treated Orthodontic Miniscrews as Anchorage Reinforcement in the Lower Arch for the Herbst Appliance: A Single-Centre, Randomised Split-Mouth Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Orthod. 2022, 44, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekizer, A.; Türker, G.; Uysal, T.; Güray, E.; Taşdemir, Z. Light Emitting Diode Mediated Photobiomodulation Therapy Improves Orthodontic Tooth Movement and Miniscrew Stability: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Lasers Surg. Med. 2016, 48, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benalcázar Jalkh, E.B.; Parra, M.; Torroni, A.; Nayak, V.V.; Tovar, N.; Castellano, A.; Badalov, R.M.; Bonfante, E.A.; Coelho, P.G.; Witek, L. Effect of Supplemental Acid-Etching on the Early Stages of Osseointegration: A Preclinical Model. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 122, 104682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, D.J.; Marques, R.G.; Elias, C.N. Influence of Acid Treatment on Surface Properties and in Vivo Performance of Ti6Al4V Alloy for Biomedical Applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2017, 28, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, S.F.; Mohammadi, A.; Behroozian, A. The Effect of Sandblasting and Acid Etching on Survival Rate of Orthodontic Miniscrews: A Split-Mouth Randomized Controlled Trial. Prog. Orthod. 2021, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervino, G.; Fiorillo, L.; Iannello, G.; Santonocito, D.; Risitano, G.; Cicciù, M. Sandblasted and Acid Etched Titanium Dental Implant Surfaces Systematic Review and Confocal Microscopy Evaluation. Materials 2019, 12, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggion, C.M. Guidelines for Reporting Pre-Clinical In Vitro Studies on Dental Materials. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2012, 12, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; De Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s Risk of Bias Tool for Animal Studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinar-Escalona, E.; Bravo-Gonzalez, L.-A.; Pegueroles, M.; Gil, F.J. Roughness and Wettability Effect on Histological and Mechanical Response of Self-Drilling Orthodontic Mini-Implants. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2016, 20, 1115–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattos, C.T.; Ruellas, A.C.D.O.; Elias, C.N. Is It Possible to Re-Use Mini-Implants for Orthodontic Anchorage? Results of an in Vitro Study. Mat. Res. 2010, 13, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Im, C.; Park, J.-H.; Jeon, Y.-M.; Kim, J.-G.; Jang, Y.-S.; Lee, M.-H.; Jeon, W.-Y.; Kim, J.-M.; Bae, T.-S. Improvement of Osseointegration of Ti–6Al–4V ELI Alloy Orthodontic Mini-Screws through Anodization, Cyclic Pre-Calcification, and Heat Treatments. Prog. Orthod. 2022, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byeon, S.-M.; Jeon, J.; Jang, Y.-S.; Jeon, W.-Y.; Lee, M.-H.; Jeon, Y.-M.; Kim, J.-G.; Bae, T.-S. Evaluation of Osseointegration of Ti-6Al-4V Alloy Orthodontic Mini-Screws with Ibandronate-Loaded TiO2 Nanotube Layer. Dent. Mater. J. 2023, 42, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gezer, P.; Yilanci, H. Comparison of Mechanical Stability of Mini-Screws with Resorbable Blasting Media and Micro-Arc Oxidation Surface Treatments under Orthodontic Forces: An in Vitro Biomechanical Study. Int. Orthod. 2023, 21, 100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, M.; Wei, L.; Werner, A.; Liu, Y. Biomimetic Calcium Phosphate Coating on Medical Grade Stainless Steel Improves Surface Properties and Serves as a Drug Carrier for Orthodontic Applications. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baser, B.; Ozel, M.B. Comparison of Primary Stability of Used and Unused Self-Tapping and Self-Drilling Orthodontic Mini-Implants. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattos, C.T.; Ruellas, A.C.; Sant’Anna, E.F. Effect of Autoclaving on the Fracture Torque of Mini-implants Used for Orthodontic Anchorage. J. Orthod. 2011, 38, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muguruma, T.; Iijima, M.; Brantley, W.A.; Yuasa, T.; Kyung, H.-M.; Mizoguchi, I. Effects of Sodium Fluoride Mouth Rinses on the Torsional Properties of Miniscrew Implants. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2011, 139, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.-S.; Kim, S.-K.; Chang, Y.-I.; Baek, S.-H. In Vitro and in Vivo Mechanical Stability of Orthodontic Mini-Implants: Effect of Sandblasted, Large-Grit, and Anodic-Oxidation vs. Sandblasted, Large-Grit, and Acid-Etching. Angle Orthod. 2012, 82, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, C.; Piemontese, M.; Ravanetti, F.; Lumetti, S.; Passeri, G.; Gandolfini, M.; Macaluso, G.M. Effect of Surface Treatment on Cell Responses to Grades 4 and 5 Titanium for Orthodontic Mini-Implants. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2012, 141, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorollahian, S.; Alavi, S.; Monirifard, M. A Processing Method for Orthodontic Mini-Screws Reuse. Dent. Res. J. 2012, 9, 447–451. [Google Scholar]

- Akyalcin, S.; McIver, H.P.; English, J.D.; Ontiveros, J.C.; Gallerano, R.L. Effects of Repeated Sterilization Cycles on Primary Stability of Orthodontic Mini-Screws. Angle Orthod. 2013, 83, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, G.; Morais, L.; Elias, C.N.; Semenova, I.P.; Valiev, R.; Salimgareeva, G.; Pithon, M.; Lacerda, R. Nanostructured Severe Plastic Deformation Processed Titanium for Orthodontic Mini-Implants. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 4197–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozlu, M.; Nalbantgil, D.; Ozdemir, F. Effects of a Newly Designed Apparatus on Orthodontic Skeletal Anchorage. Eur. J. Dent. 2013, 7, S083–S088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estelita, S.; Janson, G.; Chiqueto, K.; Ferreira, E.S. Effect of Recycling Protocol on Mechanical Strength of Used Mini-Implants. Int. J. Dent. 2014, 2014, 424923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.-J.; Nguyen, T.-D.T.; Lee, S.-Y.; Jeon, Y.-M.; Bae, T.-S.; Kim, J.-G. Enhanced Compatibility and Initial Stability of Ti6Al4V Alloy Orthodontic Miniscrews Subjected to Anodization, Cyclic Precalcification, and Heat Treatment. Korean J. Orthod. 2014, 44, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyawaki, S.; Tomonari, H.; Yagi, T.; Kuninori, T.; Oga, Y.; Kikuchi, M. Development of a Novel Spike-like Auxiliary Skeletal Anchorage Device to Enhance Miniscrew Stability. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2015, 148, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischmann, L.; Crismani, A.; Falkensammer, F.; Bantleon, H.-P.; Rausch-Fan, X.; Andrukhov, O. Behavior of Osteoblasts on TI Surface with Two Different Coating Designed for Orthodontic Devices. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2015, 26, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzorig, K.; Kuroda, S.; Maeda, Y.; Mansjur, K.; Sato, M.; Nagata, K.; Tanaka, E. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Enhances Bone Formation around Miniscrew Implants. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2015, 60, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Yan, Y.; Qi, M.; Hu, M. Strontium Coating by Electrochemical Deposition Improves Implant Osseointegration in Osteopenic Models. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 9, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tabuchi, M.; Ikeda, T.; Hirota, M.; Nakagawa, K.; Park, W.; Miyazawa, K.; Goto, S.; Ogawa, T. Effect of UV Photofunctionalization on Biologic and Anchoring Capability of Orthodontic Miniscrews. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2015, 30, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Upadhyay, M.; Roberts, W.E. Biomechanical and Histomorphometric Properties of Four Different Mini-Implant Surfaces. Eur. J. Orthod. 2015, 37, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.-K.; Chu, T.-M.; Dechow, P.; Stewart, K.; Kyung, H.-M.; Liu, S.S.-Y. Laser-Treated Stainless Steel Mini-Screw Implants: 3D Surface Roughness, Bone-Implant Contact, and Fracture Resistance Analysis. Eur. J. Orthod. 2016, 38, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y.; Kim, S.-C. Bone Cutting Capacity and Osseointegration of Surface-Treated Orthodontic Mini-Implants. Korean J. Orthod. 2016, 46, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, S.I.; Bratu, D.C.; Chiorean, R.; Balan, R.A.; Bud, A.; Petrescu, H.P.; Simon, C.P.; Dudescu, M. Biochemical Characteristics of Mini-Implants Sterilised by Different Chemical and Physical Procedures. Mater. Plast. 2017, 54, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejani, H.; Venugopal, A.; Yu, W.; Kyung, H.M. Effects of UV Treatment on Orthodontic Microimplant Surface after Autoclaving. Korean J. Dent. Mater. 2017, 44, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaci, N.; Hakem, K.; Laraba, S.; Benrekaa, N.; Le Gall, M. Micrographic Study and Torsional Strength of Grade 23 Titanium Mini-Implants Recycled for Orthodontic Purposes. Int. Orthod. 2018, 16, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, S.I.; Chiorean, R.; Bratu, D.C.; Pacurar, M.; Merie, V.; Manuc, D.; Bechir, E.S.; Teodorescu, E.; Tarmure, V.; Dudescu, M. Surface Properties and Maximum Insertion Energy of Sterilized Orthodontic Mini-Implants with Different Chemical Materials. Rev. Chim. 2018, 69, 3218–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hergel, C.A.; Acar, Y.B.; Ateş, M.; Küçükkeleş, N. In-Vitro Evaluation of the Effects of Insertion and Sterilization Procedures on the Mechanical and Surface Characteristics of Mini Screws. Eur. Oral. Res. 2019, 53, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iodice, G.; Perinetti, G.; Ludwig, B.; Polishchuk, E.V.; Polishchuk, R.S. Biological Effects of Anodic Oxidation on Titanium Miniscrews: An In Vitro Study on Human Cells. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongwannasiri, C.; Charasseangpaisarn, T.; Watanabe, S. Preliminary Testing for Reduction of Insertion Torque of Orthodontic Mini-Screw Implant Using Diamond-like Carbon Films. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1380, 012062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, N.T.K.; Shin, H.; Gupta, K.C.; Kang, I.K.; Yu, W. Bioactive Antibacterial Modification of Orthodontic Microimplants Using Chitosan Biopolymer. Macromol. Res. 2019, 27, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oga, Y.; Tomonari, H.; Kwon, S.; Kuninori, T.; Yagi, T.; Miyawaki, S. Evaluation of Miniscrew Stability Using an Automatic Embedding Auxiliary Skeletal Anchorage Device. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlic, A.; Perissinotto, F.; Turco, G.; Contardo, L.; Stjepan, S. Do Chlorhexidine and Probiotics Solutions Provoke Corrosion of Orthodontic Mini-Implants? An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2019, 34, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, S.; Asadi, F.; Raji, S.H.; Samie, S. Effect of Steam and Dry Heat Sterilization on the Insertion and Fracture Torque of Orthodontic Miniscrews. Dent. Res. J. 2020, 17, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, M.; Sabapathy, K.; Govindasamy, B.; Rajamurugan, H. Evaluation of Insertion Torque and Surface Integrity of Zirconia-Coated Titanium Mini Screw Implants. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2020, 9, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwanami-Kadowaki, K.; Uchikoshi, T.; Uezono, M.; Kikuchi, M.; Moriyama, K. Development of Novel Bone-like Nanocomposite Coating of Hydroxyapatite/Collagen on Titanium by Modified Electrophoretic Deposition. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2021, 109, 1905–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zogheib, T.; Walter-Solana, A.; De La Iglesia, F.; Espinar, E.; Gil, J.; Puigdollers, A. Do Titanium Mini-Implants Have the Same Quality of Finishing and Degree of Contamination before and after Different Manipulations? An In Vitro Study. Metals 2021, 11, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, G.; Wang, M.; Hunziker, E.B.; Liu, Y. Crystalline Biomimetic Calcium Phosphate Coating on Mini-Pin Implants to Accelerate Osseointegration and Extend Drug Release Duration for an Orthodontic Application. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.H.; Evans, C.A.; Zaki, A.M.; George, A. Use of Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 and Dentin Matrix Protein-1 to Enhance the Osteointegration of the Onplant System. Connect. Tissue Res. 2003, 44, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka-Sakamoto, K.; Hotokezaka, H.; Hotokezaka, Y.; Nashiro, Y.; Funaki, M.; Ohba, S.; Yoshida, N. Fixation of an Orthodontic Anchor Screw Using Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate in a Screw-Loosening Model in Rats. Angle Orthod. 2023, 93, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okawa, K.; Matsunaga, S.; Kasahara, N.; Kasahara, M.; Tachiki, C.; Nakano, T.; Abe, S.; Nishii, Y. Alveolar Bone Microstructure Surrounding Orthodontic Anchor Screws with Plasma Surface Treatment in Rats. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, K.; Oga, Y.; Kwon, S.; Maeda-Iino, A.; Ishikawa, T.; Miyawaki, S. A Novel Auxiliary Device Enhances Miniscrew Stability under Immediate Heavy Loading Simulating Orthopedic Treatment. Angle Orthod. 2023, 93, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Ogawa, K.; Miyazawa, K.; Kawai, T.; Goto, S. The Use of Bioabsorbable Implants as Orthodontic Anchorage in Dogs. Dent. Mater. J. 2005, 24, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, S.-H.; Cho, J.-H.; Chung, K.-R.; Kook, Y.-A.; Nelson, G. Removal Torque Values of Surface-Treated Mini-Implants after Loading. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 134, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.-W.; Baek, S.-H.; Kim, J.-W.; Chang, Y.-I. Effects of Microgrooves on the Success Rate and Soft Tissue Adaptation of Orthodontic Miniscrews. Angle Orthod. 2008, 78, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Lee, T.; Chang, C.; Liu, J. The Effect of Microrough Surface Treatment on Miniscrews Used as Orthodontic Anchors. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2009, 20, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwa, K.; Ogawa, K.; Miyazawa, K.; Aoki, T.; Kawai, T.; Goto, S. Application of α-Tricalcium Phosphate Coatings on Titanium Subperiosteal Orthodontic Implants Reduces the Time for Absolute Anchorage: A Study Using Rabbit Femora. Dent. Mater. J. 2009, 28, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.-S.; Kim, S.-H.; Kook, Y.-A.; Jeong, D.-M.; Chung, K.-R.; Nelson, G. Resistance to Immediate Orthodontic Loading of Surface-Treated Mini-Implants. Angle Orthod. 2010, 80, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, I.-S.; Kim, T.-W.; Ahn, S.-J.; Yang, I.-H.; Baek, S.-H. Effects of Insertion Angle and Implant Thread Type on the Fracture Properties of Orthodontic Mini-Implants during Insertion. Angle Orthod. 2013, 83, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-H.; Cha, J.-Y.; Joo, U.-H.; Hwang, C.-J. Surface Changes of Anodic Oxidized Orthodontic Titanium Miniscrew. Angle Orthod. 2012, 82, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmarker, S.; Yu, W.; Kyung, H.-M. Effect of Surface Anodization on Stability of Orthodontic Microimplant. Korean J. Orthod. 2012, 42, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omasa, S.; Motoyoshi, M.; Arai, Y.; Ejima, K.-I.; Shimizu, N. Low-Level Laser Therapy Enhances the Stability of Orthodontic Mini-Implants via Bone Formation Related to BMP-2 Expression in a Rat Model. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2012, 30, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, T.; Ekizer, A.; Akcay, H.; Etoz, O.; Guray, E. Resonance Frequency Analysis of Orthodontic Miniscrews Subjected to Light-Emitting Diode Photobiomodulation Therapy. Eur. J. Orthod. 2012, 34, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-C.; Cha, J.-Y.; Hwang, C.-J.; Park, Y.-C.; Jung, H.-S.; Yu, H.-S. Biologic Stability of Plasma Ion-Implanted Miniscrews. Korean J. Orthod. 2013, 43, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues Pinto, M.; Dos Santos, R.L.; Pithon, M.M.; De Souza Araújo, M.T.; Braga, J.P.V.; Nojima, L.I. Influence of Low-Intensity Laser Therapy on the Stability of Orthodontic Mini-Implants: A Study in Rabbits. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. 2013, 115, e26–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuairán, C.; Campbell, P.M.; Kontogiorgos, E.; Taylor, R.W.; Melo, A.C.; Buschang, P.H. Local Application of Zoledronate Enhances Miniscrew Implant Stability in Dogs. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2014, 145, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, K.; Motoyoshi, M.; Inaba, M.; Iwai, H.; Karasawa, Y.; Shimizu, N. A Preliminary Study of the Effects of Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Exposure on the Stability of Orthodontic Miniscrews in Growing Rats. Eur. J. Orthod. 2014, 36, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, N.-H.; Kim, E.-Y.; Paek, J.; Kook, Y.-A.; Jeong, D.-M.; Cho, I.-S.; Nelson, G. Evaluation of Stability of Surface-Treated Mini-Implants in Diabetic Rabbits. Int. J. Dent. 2014, 2014, 838356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Wassefy, N.; El-Fallal, A.; Taha, M. Effect of Different Sterilization Modes on the Surface Morphology, Ion Release, and Bone Reaction of Retrieved Micro-Implants. Angle Orthod. 2015, 85, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goymen, M.; Isman, E.; Taner, L.; Kurkcu, M. Histomorphometric Evaluation of the Effects of Various Diode Lasers and Force Levels on Orthodontic Mini Screw Stability. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2015, 33, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, I.; Shim, S.-C.; Choi, D.-S.; Cha, B.-K.; Lee, J.-K.; Choe, B.-H.; Choi, W.-Y. Effect of TiO2 Nanotubes Arrays on Osseointegration of Orthodontic Miniscrew. Biomed. Microdevices 2015, 17, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisa-Ard, A.; Michael, S.N.W.; Ahmed, K.; Dunstan, C.R.; Pearce, S.G.; Bilgin, A.A.; Dalci, O.; Darendeliler, M.A. Histomorphological and Torque Removal Comparison of 6 Mm Orthodontic Miniscrews with and without Surface Treatment in New Zealand Rabbits. Eur. J. Orthod. 2015, 37, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabuchi, M.; Ikeda, T.; Nakagawa, K.; Hirota, M.; Park, W.; Miyazawa, K.; Goto, S.; Ogawa, T. Ultraviolet Photofunctionalization Increases Removal Torque Values and Horizontal Stability of Orthodontic Miniscrews. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2015, 148, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilani, G.N.L.; Ruellas, A.C.D.O.; Elias, C.N.; Mattos, C.T. Stability of Smooth and Rough Mini-Implants: Clinical and Biomechanical Evaluation—An in Vivostudy. Dent. Press. J. Orthod. 2015, 20, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bayani, S.; Masoomi, F.; Aghaabbasi, S.; Farsinejad, A. Evaluation of the Effect of Platelet-Released Growth Factor and Immediate Orthodontic Loading on the Removal Torque of Miniscrews. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2016, 31, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, B.-K.; Choi, D.-S.; Jang, I.; Choe, B.-H.; Choi, W.-Y. Orthodontic Tunnel Miniscrews with and without TiO2 Nanotube Arrays as a Drug-Delivery System: In Vivo Study. Bio-Medical Mater. Eng. 2016, 27, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, K.-J.; Sung, S.-J.; Chun, Y.-S.; Hwang, C.-J. Stress Distributions in Peri-Miniscrew Areas from Cylindrical and Tapered Miniscrews Inserted at Different Angles. Korean J. Orthod. 2016, 46, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gansukh, O.; Jeong, J.-W.; Kim, J.-W.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, T.-W. Mechanical and Histological Effects of Resorbable Blasting Media Surface Treatment on the Initial Stability of Orthodontic Mini-Implants. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 7520959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Motoyoshi, M.; Inaba, M.; Hagiwara, Y.; Shimizu, N. Enhancement of Orthodontic Anchor Screw Stability Under Immediate Loading by Ultraviolet Photofunctionalization Technology. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2016, 31, 1320–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jang, I.; Choi, D.-S.; Lee, J.-K.; Kim, W.-T.; Cha, B.-K.; Choi, W.-Y. Effect of Drug-Loaded TiO2 Nanotube Arrays on Osseointegration in an Orthodontic Miniscrew: An in-Vivo Pilot Study. Biomed. Microdevices 2017, 19, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maino, B.G.; Di Blasio, A.; Spadoni, D.; Ravanetti, F.; Galli, C.; Cacchioli, A.; Katsaros, C.; Gandolfini, M. The Integration of Orthodontic Miniscrews under Mechanical Loading: A Pre-Clinical Study in Rabbit. Eur. J. Orthod. 2017, 39, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.-D.; Choi, S.-H.; Cha, J.-Y.; Yu, H.-S.; Kim, K.-M.; Kim, J.; Hwang, C.-J. Effects of Recycling on the Biomechanical Characteristics of Retrieved Orthodontic Miniscrews. Korean J. Orthod. 2017, 47, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, T.-H.; Park, J.-H.; Moon, W.; Chae, J.-M.; Chang, N.-Y.; Kang, K.-H. Effects of Acid Etching and Calcium Chloride Immersion on Removal Torque and Bone-Cutting Ability of Orthodontic Mini-Implants. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 154, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakopoulou, A.; Hoang, P.; Fathi, A.; Foley, M.; Dunstan, C.; Dalci, O.; Papadopoulou, A.K.; Darendeliler, M.A. A Comparative Histomorphological and Micro Computed Tomography Study of the Primary Stability and the Osseointegration of The Sydney Mini Screw; a Qualitative Pilot Animal Study in New Zealand Rabbits. Eur. J. Orthod. 2019, 41, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücesoy, T.; Seker, E.; Cenkcı, E.; Yay, A.; Alkan, A. Histologic and Biomechanical Evaluation of Osseointegrated Miniscrew Implants Treated with Ozone Therapy and Photobiomodulation at Different Loading Times. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2019, 34, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.-C.; Hung, W.-C.; Lan, W.-C.; Saito, T.; Huang, B.-H.; Lee, C.-H.; Tsai, H.-Y.; Huang, M.-S.; Ou, K.-L. Anodized Biomedical Stainless-Steel Mini-Implant for Rapid Recovery in a Rabbit Model. Metals 2021, 11, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-H.; Shin, J.; Cha, J.-K.; Kwon, J.-S.; Cha, J.-Y.; Hwang, C.-J. Evaluation of Success Rate and Biomechanical Stability of Ultraviolet-Photofunctionalized Miniscrews with Short Lengths. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2021, 159, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auciello, O.; Renou, S.; Kang, K.; Tasat, D.; Olmedo, D. A Biocompatible Ultrananocrystalline Diamond (UNCD) Coating for a New Generation of Dental Implants. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seker, E.D.; Yavuz, I.; Yucesoy, T.; Cenkci, E.; Yay, A. Comparison of the Stability of Sandblasted, Large-Grit, and Acid-Etched Treated Mini-Screws with Two Different Surface Roughness Values: A Histomorphometric Study. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2022, 33, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-T.; Liou, E.J.-W.; Chen, S.-W. Comparison between Microporous and Nanoporous Orthodontic Miniscrews: An Experimental Study in Rabbits. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2024, 85, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrani, O.K. Comparison of in Vivo Failure of Precipitation-Coated Hydroxyapatite Temporary Anchorage Devices with That of Uncoated Temporary Anchorage Devices over 18 Months. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2023, 163, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, J.; Duraisamy, S.; Rajaram, K.; Kannan, R.; Arumugam, E. Survival Rate and Stability of Surface-Treated and Non-Surface-Treated Orthodontic Mini-Implants: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2023, 28, e2321345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Choi, J.-H.; Chung, K.-R.; Nelson, G. Do Sand Blasted with Large Grit and Acid Etched Surface Treated Mini-Implants Remain Stationary under Orthodontic Forces? Angle Orthod. 2012, 82, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, J.H.; Valencia, R.M.; Casasa, A.A.; Sánchez, M.A.; Espinosa, R.; Ceja, I. Biomechanical Anchorage Evaluation of Mini-Implants Treated with Sandblasting and Acid Etching in Orthodontics. Implant. Dent. 2011, 20, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matys, J.; Flieger, R.; Gedrange, T.; Janowicz, K.; Kempisty, B.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Dominiak, M. Effect of 808 Nm Semiconductor Laser on the Stability of Orthodontic Micro-Implants: A Split-Mouth Study. Materials 2020, 13, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flieger, R.; Gedrange, T.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Dominiak, M.; Matys, J. Low-Level Laser Therapy with a 635 Nm Diode Laser Affects Orthodontic Mini-Implants Stability: A Randomized Clinical Split-Mouth Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schätzle, M.; Männchen, R.; Balbach, U.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Toutenburg, H.; Jung, R.E. Stability Change of Chemically Modified Sandblasted/Acid-etched Titanium Palatal Implants. A Randomized-controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2009, 20, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-J.; Choi, S.-H.; Choi, Y.J.; Park, Y.-B.; Kim, K.-M.; Yu, H.-S. A Prospective, Split-Mouth, Clinical Study of Orthodontic Titanium Miniscrews with Machined and Acid-Etched Surfaces. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuereb, M.; Camilleri, J.; Attard, N. Systematic Review of Current Dental Implant Coating Materials and Novel Coating Techniques. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2015, 28, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.-H.; Jang, S.-H.; Cha, J.-Y.; Hwang, C.-J. Evaluation of the Surface Characteristics of Anodic Oxidized Miniscrews and Their Impact on Biomechanical Stability: An Experimental Study in Beagle Dogs. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2016, 149, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagay, B.E.; Dini, C.; Borges, G.A.; Mesquita, M.F.; Cavalcanti, Y.W.; Magno, M.B.; Maia, L.C.; Barão, V.A.R. Clinical Efficacy of Anodized Dental Implants for Implant-supported Prostheses after Different Loading Protocols: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2021, 32, 1021–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, C.; Nagay, B.E.; Magno, M.B.; Maia, L.C.; Barão, V.A.R. Photofunctionalization as a Suitable Approach to Improve the Osseointegration of Implants in Animal Models—A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2020, 31, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).