Abstract

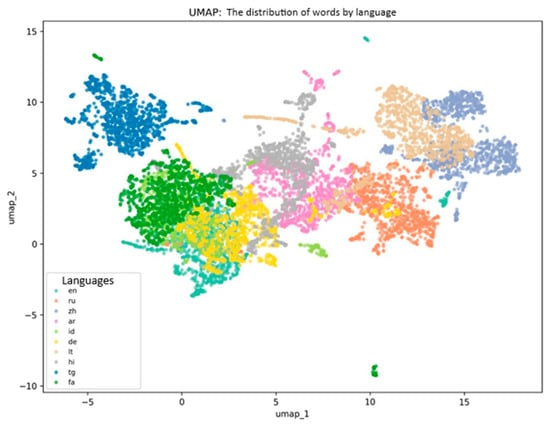

Understanding how linguistic typology shapes multilingual embeddings is important for cross-lingual NLP. We examine static MUSE word embedding for ten diverse languages (English, Russian, Chinese, Arabic, Indonesian, German, Lithuanian, Hindi, Tajik and Persian). Using pairwise cosine distances, Random Forest classification, and UMAP visualization, we find that language identity and script type largely determine embedding clusters, with morphological complexity affecting cluster compactness and lexical overlap connecting clusters. The Random Forest model predicts language labels with high accuracy (≈98%), indicating strong language-specific patterns in embedding space. These results highlight script, morphology, and lexicon as key factors influencing multilingual embedding structures, informing linguistically aware design of cross-lingual models.

Keywords:

word embeddings; MUSE; random forest; UMAP; cross-lingual NLP; language typology; multilingual data 1. Introduction

The development of multilingual NLP has raised interest in how typological differences (script, morphology, lexicon) affect word embeddings. In contrast to English, many languages (e.g., Russian or Arabic) have different scripts and rich inflection, which could influence their embedding representations. Prior work has explored multilingual embedding methods: for instance, Devlin et al. [1] proposed multilingual BERT for cross-lingual tasks, and Pires et al. [2] analyzed mBERT’s capabilities. Conneau et al. [3] introduced XLM-R, a large-scale cross-lingual model, and Ruder et al. [4] surveyed cross-lingual embedding models. However, these studies focus on model performance and do not explicitly measure the role of script, morphology, or lexical overlap in embedding geometry. In this work, we focus explicitly on these mechanisms by combining quantitative analysis of multilingual MUSE word embeddings with visualization techniques.

Research questions. This study addresses the following questions:

- Do clear language clusters form in the MUSE embedding space?

- How close are word vectors for different languages depending on shared script, morphological complexity, and lexical overlap?

- Which factors are most strongly associated with language separation in the embedding space?

To address these research questions, we analyze 300-dimensional MUSE word embeddings for ten typologically diverse languages using three complementary tools: a Random Forest classifier that quantifies how strongly language identity is encoded in the embeddings; cosine distance analysis between mean language vectors, which summarizes global separation between languages; and two-dimensional UMAP projections that make the geometry of language clusters interpretable. Each of these methods is described in detail in Section 4.

The advancement of artificial intelligence and automatic machine translation systems—encompassing both individual words and entire documents—has heightened the importance of research in cross-lingual word comparison. Understanding how linguistic properties influence multidimensional embeddings is critical: languages with different scripts and morphological properties may exhibit different geometric patterns in embedding spaces. Identifying appropriate mathematical embedding models for text analysis, multi-page document translation, and financial document processing is essential.

For example, the SWIFT system (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications), which conveys financial messages in English, incorporates built-in mechanisms for generating bank guarantees that can be automatically issued, translated into 2–3 languages, and verified by SWIFT while accurately accounting for the legal terminology characterizing bank guarantees across different languages.

Cognitive linguistic principles prove valuable in intercultural and interlingual communication, particularly when translational analysis and text transformation from primary to secondary forms (metatexts) are necessary [5,6,7,8].

Contribution and Structure of the Paper

We analyze MUSE-compatible word embeddings for ten typologically diverse languages (English, Russian, Chinese, Arabic, Indonesian, German, Lithuanian, Hindi, Tajik, and Persian) using cosine distance analysis, a Random Forest classifier, and UMAP projections.

This paper makes three main contributions. (1) We systematically study language-level structure in a shared embedding space by combining quantitative cosine distance measures, supervised classification, and low-dimensional visualization. (2) We introduce simple interpretable indicators for script type and morphology proxies and relate them to distances between languages in the embedding space. (3) We provide a qualitative interpretation of language clusters in UMAP space, discussing how script, morphology, and lexical connections can be related to the observed patterns.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the key terminology. Section 3 reviews related work on multilingual and cross-lingual embeddings. Section 4 describes the dataset, the methodological setup (Random Forest classifier, cosine distance analysis, and UMAP visualization), and presents the empirical results. Section 5 concludes and outlines directions for future research.

2. Terminology

Embedding: A vector representation of a word in multidimensional space, reflecting its semantic and lexical properties [1,9].

MUSE: An instrument for constructing multilingual embeddings [10,11].

Random Forest (RF): An ensemble machine learning method for classification, employed here to predict language from word embeddings [12].

Cosine Distance: A similarity measure between vectors in embedding space, where 0 indicates complete correspondence and 2 represents opposite directions [13].

UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection): A nonlinear dimensionality reduction method for projecting high-dimensional data into low-dimensional space, enabling visualization of structural relationships [14].

Script: The writing system of a language (Latin, Cyrillic, Arabic, logographic characters) [15].

Morphology: The system governing word formation and inflection [16].

Zipf Frequency (zipf_freq): Word frequency normalized according to Zipf’s law within the corpus [17,18,19,20].

These definitions follow standard usage in cross-lingual representation learning and multilingual NLP (see, e.g., Devlin et al. [1], Pires et al. [2], Ruder et al. [4], and Bojanowski et al. [9]).

3. Related Works

The automation of cross-lingual translation and data preprocessing has been addressed by numerous researchers [1,2,4,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Notably, Pires et al. [2] conducted a comprehensive empirical comparison of Wikipedia articles on the same term across 104 languages. Their study compared baseline language articles with analogous articles in other languages and developed a cross-transfer model preserving semantic meaning. While the work primarily focused on mBERT and transfer tasks, it provided limited clustering analysis and lacked sufficient interpretable metrics for explaining clustering behavior.

Kvapilíková et al. [27] examined methods for obtaining shared word embeddings across multiple languages without parallel data, establishing a foundation for measuring “linguistic identity” in embeddings. However, their work insufficiently addressed linguistic factors such as script and morphology, instead concentrating on algorithmic alignment and downstream metrics rather than UMAP visualizations and interpretation of clustering causes.

Ruder et al.’s [4] survey on cross-lingual word embedding models highlights a fundamental challenge: words in different languages may not have complete correspondence across their characteristic features.

Thus, cross-lingual word representations in machine translation systems constitute a critical contemporary challenge. These representations enable reasoning about word meaning in multilingual contexts and are fundamental to interlingual transfer in natural language processing model development. Ruder et al.’s survey [4] systematizes various approaches (supervised/unsupervised, linear mappings, joint training) and proposes a typology encompassing word, sentence, and document alignment. The authors emphasize that alignment methods substantially affect outcomes and that source data characteristics and language alignment types must be considered. Whether data are parallel or merely comparable (addressing the same topic) significantly influences methodology selection.

However, the survey lacks sufficient treatment of practical applications. Its primarily review-oriented nature does not provide foundations for new empirical experiments involving UMAP visualization or specific morphology/script case studies. While valuable as a reference resource, it does not serve as a direct replicable model for analogous experimentation.

Modern vector representation techniques—particularly word embeddings—enable systematic investigation of the lexical and semantic properties of languages within multidimensional spaces. MUSE (Multilingual Unsupervised and Supervised Embeddings) represents a key instrument for constructing multilingual embeddings by establishing a unified embedding space across languages.

The present study evaluates how linguistic properties influence embedding structure, quantifies language differentiation, and explains the underlying factors determining language positioning in reduced-dimensional visualizations (UMAP). Understanding these mechanisms is essential for advancing cross-lingual natural language processing applications and improving multilingual machine learning systems (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of related work on cross-lingual embeddings.

4. Data and Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

For every selected word we store the language label (lang), the word form, word length in characters, script type (Latin, Cyrillic, Arabic, logographic, etc.), and the 300-dimensional embedding vector (emb_0 … emb_299). For visualization, we additionally compute two-dimensional UMAP coordinates (umap_1, umap_2). All analyses in this paper are based on this tabular dataset of word-level embeddings. A full description of the dataset (including the list of selected word types) is available from the authors upon request.

For each language, we select the 1000 most frequent word types from the corresponding fastText vocabulary. Frequencies are estimated using Zipf scores from the wordfreq library, and tokens consisting solely of punctuation marks or special symbols are removed. This procedure yields a balanced sample of 10,000 word types (1000 per language).

We use 300-dimensional word embeddings for ten languages: English, Russian, Chinese, Arabic, Indonesian, German, Lithuanian, Hindi, Tajik, and Persian. As input vector representations, we rely on standard fastText word vectors [9] that are compatible with the MUSE framework. We do not retrain MUSE or perform additional alignment, but instead use these monolingual embeddings in the form in which they are commonly distributed.

4.2. Materials and Methods

We compute the following variables for our analysis: language identity (language label), script type, proxies for morphological complexity (such as average word length and the presence of affixes), and lexical overlap between each pair of languages (the proportion of shared word forms or lexical correspondences estimated from the cross-lingual vocabulary).

UMAP is sensitive to hyperparameters, so we explicitly set n_neighbors = 15 and min_dist = 0.1 and fix the random seed to ensure reproducibility. These parameters control the granularity of clusters and the preservation of local neighborhood structure in the two-dimensional projection.

4.2.1. Random Forest Classification

To assess how well the embeddings separate languages, we train a Random Forest classifier. The 300-dimensional word embeddings serve as input features, and the target label is the language (lang). The dataset is split into training and test subsets. After training, the classifier predicts the language of each word based on its embedding. The resulting test accuracy of approximately 0.987 indicates that the model almost always correctly predicts the language, which we interpret as evidence that the embeddings carry strong language-specific information. (This result is expected, since the embeddings are trained separately for different languages).

4.2.2. Cosine Distance Analysis

Cosine distance between two embedding vectors A and B is computed as

Here, A and B are embedding vectors, and (A · B)/(‖A‖ ‖B‖) is the cosine of the angle between them. When vectors coincide, = 0; when vectors are orthogonal, = 1; when vectors point in opposite directions, = 2.

To evaluate global language differentiation, we apply cosine distance defined in Equation (1) to mean embeddings for each language. For every pair of languages, we compute the cosine distance between their mean vectors. The resulting cosine distance matrix is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cosine Distance Matrix.

Diagonal elements of the matrix are equal to 0 (within-language distance), while the off-diagonal values reflect differences between languages. In our case, off-diagonal dcos values lie approximately between 0.87 and 1.11. This indicates that languages are, on average, well separated in embedding space (values close to 1) while still being partially similar (values are well below the maximum possible distance of 2).

4.2.3. UMAP-Visualization

UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) represents a dimensionality reduction technique that preserves local structures within data (Figure 1) and projects 300-dimensional embeddings into 2D while preserving local neighborhood structure; global distances can be distorted, so the visualization should be interpreted qualitatively.

Figure 1.

Multidimensional embedding structure (authors’ Python 3.11 computation).

UMAP was applied to visualize the structure of high-dimensional word embeddings. This method projects multidimensional vectors (300-dimensional word embeddings in this study) into low-dimensional space (2D) while preserving local neighborhood structures and global patterns. Coordinates umap_1 and umap_2 represent each word’s position in this reduced space.

UMAP application is justified because it enables visual assessment of embedding similarity and differentiation between languages, broadly preserves local neighborhoods that reflect cosine similarity relationships (even though the projection may distort global structure), and provides a two-dimensional space (umap_1–umap_2) that facilitates interpretation and identification of language clusters for subsequent lexical and morphological analysis.

UMAP visualization revealed semantic spaces of language-specific words using 300-dimensional embeddings trained on large text corpora. Word embeddings are constructed based on distributional patterns reflecting semantic and functional properties. Thus, vector distances in embedding space characterize semantic proximity, and language-level vector averaging estimates lexical system similarity and differentiation.

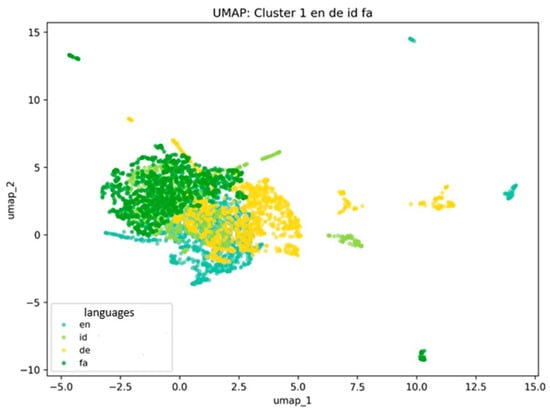

English, German, Indonesian, and Persian form a unified cluster, explained by both historical-genetic factors and lexical borrowing. English and German, both Germanic languages, share common etymological roots in basic vocabulary, while Indonesian has extensively borrowed contemporary lexicon from English, particularly in technology and culture domains. Persian, though genetically unrelated, demonstrates semantic proximity through historical borrowing and shared conceptual fields. In UMAP space, these languages cluster together because their words occupy similar positions in embedding space, reflecting lexical overlap and common semantic categories. The cluster of English, German, Indonesian, and Persian is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Visualization of Multidimensional Embedding Structure: en = English, de = German, id = Indonesian, fa = Persian (Authors’ computation in Python 3.11).

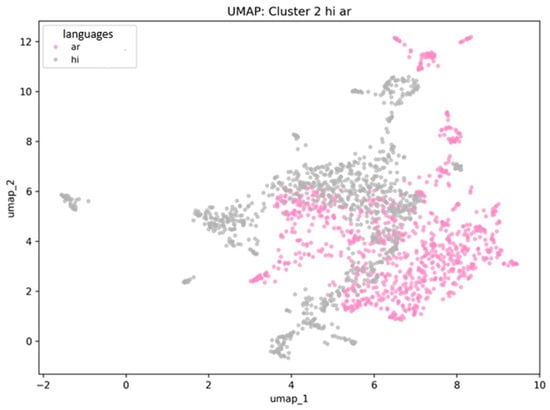

Hindi and Arabic languages are positioned in close proximity with partial cluster overlap. This spatial configuration reflects deep historical and cultural interactions: Hindi incorporates substantial loanwords from Sanskrit and Arabic transmitted through Urdu, in addition to shared religious and cultural terminology. Within embedding space, words exhibiting similar contextual patterns are positioned proximally; UMAP visualizes this proximity as partial cluster intersection, suggesting semantic proximity in this embedding space. The Arabic–Hindi partial overlap is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Visualization of Multidimensional Embedding Structure: ar = Arabic and hi = Hindi Languages. (Authors’ computation in Python 3.11).

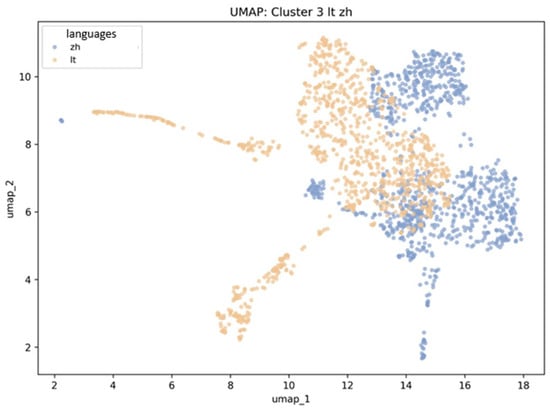

Lithuanian and Chinese demonstrate partial cluster overlap, which may initially appear unexpected. The vast majority of vocabulary in both languages is unique to their cultural-typological systems, explaining their relative isolation from other languages. Lithuanian and Chinese proximity in UMAP does not reflect lexical commonality; rather, both languages show minimal overlap with other languages represented in the study. In embedding terms, their words exhibit unique contextual distributions distinguished from others. UMAP’s 2D projection preserves local distances: words and languages with substantial semantic field intersection cluster together, while unique semantic spaces (with minimal cross-linguistic overlap) occupy peripheral positions. Consequently, Lithuanian and Chinese form adjacent but separate clusters not because they share lexical content, but because both are semantically “distant” from the remaining languages. Their proximity in 2D space reflects similarity in degree of isolation rather than lexical affinity. The Lithuanian–Chinese configuration is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Visualization of Multidimensional Embedding Structure: lt = Lithuanian and zh = Chinese Languages. (Authors’ computation in Python 3.11).

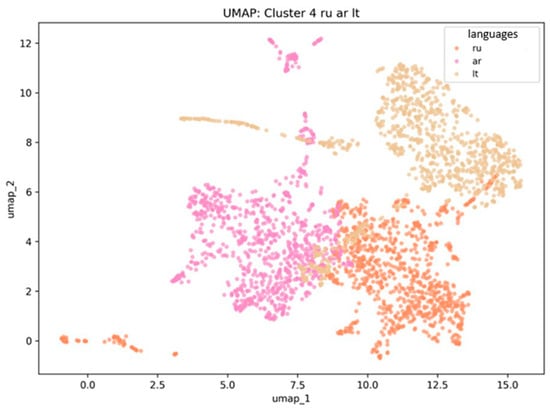

Russian occupies an intermediate position between Arabic and Lithuanian. This positioning reflects the combined influence of its Slavic foundation, extensive borrowings from European languages such as German and French, and Eastern lexical influences through historical contact. In embedding space, Russian words create a bridge between European and East Asian lexical spaces, reflecting the richness and multilayered semantic relationships within Russian vocabulary. The intermediate position of Russian is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Visualization of Multidimensional Embedding Structure: ru = Russian, ar = Arabic, and lt = Lithuanian Languages. (Authors’ computation in Python 3.11).

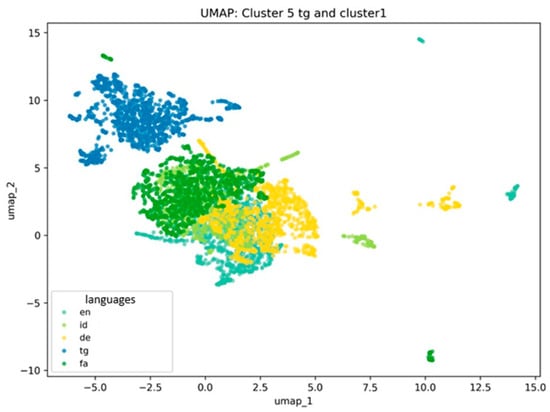

Tajik forms a distinct cluster yet positions closer to the English, German, Indonesian, and Persian cluster. This proximity reflects genetic affinity with Persian: Tajik shares cognate vocabulary and preserves semantic connections through closely related conceptual fields. Despite distinct clustering, proximity to the European-Persian language group reflects lexical overlap, particularly through shared borrowing patterns and common semantic categories. The Tajik cluster relative to the European–Persian group is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Visualization of Multidimensional Embedding Structure: tg = Tajik, en = English, de = German, id = Indonesian and fa = Persian Languages. (Authors’ computation in Python 3.11).

Revised UMAP discussion. Our analysis shows that, in UMAP space, language proximity is often associated with lexical and semantic commonalities. For example, languages with substantial mutual influence (through borrowing or shared concepts) tend to appear closer together. However, UMAP clusters must be interpreted with caution: UMAP is a heuristic visualization method that is sensitive to the choice of hyperparameters and random initialization. Proximity in the 2D projection does not prove genetic relatedness, but rather reflects embedding patterns in the data. In particular, UMAP emphasizes local structure: words with similar contextual usage are pulled together, while rare or unique words are pushed apart.

Through UMAP, words with similar contextual meanings form local clusters despite originating from different languages or dialects. Such clusters reflect overlapping universal semantic categories: basic concepts, numerals, object references, actions, and abstract notions. Conversely, words unique to specific cultural or historical contexts occupy peripheral positions, creating isolated semantic spaces.

This methodological approach enables detection of latent semantic relationships between words and concepts that are obscured in traditional dictionary-based analysis, comparison of lexical fields across languages, dialects, and text corpora (facilitating the investigation of loanwords, calques, and patterns of semantic influence), investigation of universal and language-specific semantic categories that are essential for lexicography, cognitive linguistics, and multilingual model development, and assessment of embedding and language model quality by evaluating how effectively they capture lexical semantic structure.

Collectively, embeddings and their UMAP projection enable systematic, quantitative lexical analysis revealing structure, overlap, and differentiation at the semantic category level-capabilities difficult to achieve through traditional dictionary or corpus methods alone. This integrated approach combines statistical methodology with linguistic analysis, creating a robust instrument for contemporary lexicological research.

5. Conclusions

Our results show that language plays an important role in shaping the structure of the embeddings. Languages with similar typological properties (such as a shared script or overlapping lexicon) tend to form neighboring clusters, although no single property fully determines the entire space. For example, Russian (Cyrillic script and rich inflectional morphology) appears as a more isolated cluster, whereas English, Indonesian, and Chinese (analytic languages with relatively simple morphology) exhibit greater proximity in embedding space. Arabic shows some proximity to a group of Southeast-related languages, possibly due to shared religious and cultural terminology. The high Random Forest classification accuracy and the cosine distance values confirm that the embeddings are clearly separated by language, while the UMAP projection additionally reveals details of cluster structure and overlap. Overall, the embeddings reflect a combination of linguistic features-script, morphology, and lexical connections. These findings may help to better account for language typology when designing multilingual NLP models.

In future work, we will enlarge the dataset by increasing the number of tokens and words per language and by including additional corpora to reduce sampling bias. We will also evaluate alternative distance measures and classifiers to verify that the conclusions are not driven by a particular metric or model choice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.A. and A.L.B.; methodology, A.V.A. and A.L.B.; software, A.V.A.; validation, A.V.A., A.L.B., Y.X. and L.S.S.; formal analysis, A.V.A.; investigation, A.V.A.; resources, A.L.B.; data curation, A.V.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.A.; writing—review and editing, A.L.B., Y.X. and L.S.S.; visualization, A.V.A.; supervision, A.L.B.; project administration, A.L.B.; funding acquisition, A.L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors’ research is supported by the Moscow Center of Fundamental and Applied Mathematics of Lomonosov Moscow State University under agreement No. 075-15-2025-345.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, T.; Schlinger, E.; Garrette, D. How Multilingual Is Multilingual BERT? Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:174798142 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Conneau, A.; Khandelwal, K.; Goyal, N.; Chaudhary, V.; Wenzek, G.; Guzmán, F.; Grave, E.; Ott, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Unsupervised Cross-Lingual Representation Learning at Scale. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 8440–8451. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1911.02116 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Ruder, S.; Vulić, I.; Søgaard, A. A Survey of Cross-Lingual Word Embedding Models. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1706.04902v2 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Lukoyanova, T.V. Cognitive Terminology as One of the New Schools in Modern Linguistics. Ling. Mobilis 2014, 3, 75–80. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/kognitivnoe-terminovedenie-kak-odno-iz-napravleniy-sovremennoy-lingvistiki (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Boldyrev, N.E.; Belyaeva, I.V. Cognitive Mechanisms for Constructing the Interpretative Meaning of Phraseological Units in the Context of Conflict-Free Communication. Bull. Russ. Univ. Peoples’ Friendsh. Ser. Linguist. Semiot. Semant. 2022, 13, 925–936. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366650980_Cognitive_Mechanisms_of_Phraseological_Units_Interpretive_Meaning_Construction_in_Relation_to_Conflict-Free_Communication (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Boldyrev, N.N.; Efimenko, T.N. The Influence Potential of Media Text: A Cognitive Approach. Issues Cogn. Linguist. 2025, 3, 5–18. Available online: https://vcl.ralk.info/issues/2025/vypusk-3-2025/vozdeystvuyushchiy-potentsial-mediateksta-kognitivnyy-podkhod.html (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Konurbaev, M.E.; Ganeeva, E.R. Cognitive Basis of Speech Compression in Oral Translation. Issues Cogn. Linguist. 2024, 2, 24–32. Available online: https://vcl.ralk.info/issues/2024/vypusk-2-2024/kognitivnye-osnovy-rechevoy-kompressii-v-ustnom-perevode.html (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Bojanowski, P.; Grave, E.; Joulin, A.; Mikolov, T. Enriching Word Vectors with Subword Information. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2017, 5, 135–146. Available online: https://fasttext.cc/docs/en/crawl-vectors.html (accessed on 8 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Meta AI. MUSE: Multilingual Unsupervised and Supervised Embeddings. Available online: https://github.com/facebookresearch/MUSE (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Conneau, A.; Lample, G.; Ranzato, M.; Denoyer, L.; Jégou, H. Word Translation Without Parallel Data. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1710.04087 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salton, G.; Wong, A.; Yang, C.S. A Vector Space Model for Automatic Indexing. Commun. ACM 1975, 18, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Saul, N.; Großberger, L. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, P.T.; Bright, W. (Eds.) The World’s Writing Systems; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 9780195079937. [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff, M.; Fudeman, K. What Is Morphology? 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Speer, R. Rspeer/wordfreq: V3.0. Zenodo 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brysbaert, M.; New, B. Moving beyond Kučera and Francis: A critical evaluation of current word frequency norms and the introduction of a new and improved word frequency measure for American English. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Heuven, W.J.B.; Mandera, P.; Keuleers, E.; Brysbaert, M. SUBTLEX-UK: A New and Improved Word Frequency Database for British English. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2014, 67, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipf, G.K. Human Behavior and the Principle of Least Effort: An Introduction to Human Ecology; Addison-Wesley Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Rayyash, H.; Lacruz, I. Through the Eyes of the Viewer: The Cognitive Load of LLM-Generated vs. Professional Arabic Subtitles. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2025, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saretzki, J.; Knopf, T.; Forthmann, B.; Goecke, B.; Jaggy, A.-K.; Benedek, M.; Weiss, S. Scoring German Alternate Uses Items Applying Large Language Models. J. Intell. 2025, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafron, E. The Accounting Tower of Babel: Language and the Translation of International Accounting Standards. SSRN Electron. J. 2023, 4394442, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; Scala, C.; Samuel, J.; Kumar, V.; Jain, P. Are Emotions Conveyed across Machine Translations? Establishing an Analytical Process for the Effectiveness of Multilingual Sentiment Analysis with Italian Text. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5266525 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Ding, Q.; Cao, H.; Cao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, T. Cross-Lingual Semantic Information Fusion for Word Translation Enhancement. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5062126 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Fu, B.; Brennan, R.; O’Sullivan, D. A Configurable Translation-Based Cross-Lingual Ontology Mapping System to Adjust Mapping Outcome. In Proceedings of the ESWC 2012, Heraklion, Greece, 27–31 May 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvapilíková, I.; Artetxe, M.; Labaka, G.; Agirre, E.; Bojar, O. Unsupervised Multilingual Sentence Embeddings for Parallel Corpus Mining. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Student Research Workshop, Seattle, WA, USA, 5–10 July 2020; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.