Abstract

Machine learning models and web-based tools have been developed for predicting key properties of imidazolium-based ionic liquids. Two high-quality datasets containing experimental density and viscosity values at 298 K were curated from the ILThermo database: one containing 434 systems for density and another with 293 systems for viscosity. Molecular structures were optimized using the GOAT procedure at the GFN-FF level to ensure chemically realistic geometries, and a diverse set of molecular descriptors, including electronic, topological, geometric, and thermodynamic properties, was calculated. Three support vector regression models were built: two for density (IonIL-IM-D1 and IonIL-IM-D2) and one for viscosity (IonIL-IM-V). IonIL-IM-D1 uses three simple descriptors, IonIL-IM-D2 improves accuracy with seven, and IonIL-IM-V employs nine descriptors, including DFT-based features. These models, designed to predict the mentioned properties at room temperature (298 K), are implemented as interactive applications on the atomistica.online platform, enabling property prediction without coding or retraining. The platform also includes a structure generator and searchable databases of optimized structures and descriptors. All tools and datasets are freely available for academic use via the official web site of the atomistica.online platform, supporting open science and data-driven research in molecular design.

1. Introduction

Ionic liquids (ILs) are a class of salts that remain in the liquid state at or near room temperature, typically below 100 °C [1,2]. Unlike conventional salts such as sodium chloride, which form rigid crystalline solids at room temperature, ILs are composed entirely of bulky organic cations and various anions that inhibit lattice formation due to their asymmetry and charge delocalization [3]. This structural nature leads to a low melting point and a liquid state over a wide temperature range. ILs can be broadly classified based on the nature of their cations (e.g., imidazolium, pyridinium, ammonium, phosphonium) and anions (e.g., halides, tetrafluoroborate, hexafluorophosphate, bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide). Further subclassifications may include protic vs. aprotic ILs, task-specific ILs, and deep eutectic solvents, which share similar behavior under certain conditions.

ILs are widely recognized for their unique physicochemical properties that distinguish them from conventional molecular solvents [4,5,6]. These properties include very low and almost negligible vapor pressure, high thermal and chemical stability, non-flammability, high ionic conductivity, and a wide electrochemical window. ILs also possess significant structural tenability. Namely, by varying the cation–anion combinations, it is possible to obtain target values of properties such as viscosity, density, hydrophobicity, polarity, and solvation ability [4,7,8,9,10,11]. In particular, imidazolium-based ILs have been extensively studied due to their balanced physical properties and chemical stability. However, even though ILs have promising potential, some of their physical properties can vary dramatically depending on molecular structure and operating conditions, which complicates their design and application.

Due to this unique suite of properties, ILs have attracted widespread attention for various practical applications. They are used as green solvents in synthetic chemistry and catalysis, as electrolytes in batteries and supercapacitors, as lubricants, and in separation processes such as CO2 capture, biomass dissolution, and liquid–liquid extraction [7,12,13]. ILs also show promise in pharmaceutical formulations, electrochemical devices, and the stabilization of nanomaterials [14,15,16]. Nevertheless, challenges remain. Many ILs are costly to synthesize and purify, their biodegradability and toxicity profiles are still under investigation, and their physical properties are not always predictable a priori. These limitations emphasize the need for predictive models and digital tools that can accelerate IL design and screening, particularly for critical properties such as viscosity and density.

Atomistic modeling has become a crucial step in the development of novel materials [17,18,19,20,21,22]. By simulating systems at the atomic and electronic levels, quantum mechanical methods such as density functional theory (DFT) or modern wavefunction-based methods, combined with molecular dynamics (MD), enable researchers to investigate electronic configurations, thermodynamic behavior, conformational dynamics, and intermolecular forces with high precision [23,24,25]. These approaches offer the possibility to predict properties that complement and extend beyond experimental observation, guiding the design of functional materials and molecules across chemistry, physics, and materials science.

Due to their complexity and ability to fine-tune properties, ionic liquids are especially well-suited for atomistic calculations. Methods like DFT are commonly used to explore the electronic structure and chemical behavior of their components. These calculations offer insights into charge distribution, molecular orbitals, hydrogen bonding, and interactions between ions [26,27,28]. DFT calculations are also helpful for quantifying properties such as dipole moments, polarizability, electrostatic potential maps, and binding energies between cations and anions [29,30,31]. These electronic-level descriptors are crucial for understanding how subtle variations in ion structures affect macroscopic properties, such as viscosity, conductivity, and thermal stability. In addition, DFT-derived data often serve as the basis for developing machine learning (ML) models, providing a consistent and reproducible way to represent molecular systems numerically.

Aside from atomistic calculations, ML has emerged as a crucial approach in molecular science, providing new strategies for predicting properties, providing insights into structure–property relationships, and informing the design of novel compounds [32,33,34]. By analyzing data and through learning patterns, ML models can simulate complex quantum or thermodynamic behaviors without the need for computationally intensive simulations for each new system. This is important when it comes to ILs, where small structural changes can lead to significant variations in their properties. ML algorithms such as support vector regression (SVR), random forests, and neural networks can use molecular descriptors, derived from quantum mechanical calculations, cheminformatics, or topology, to construct accurate predictive models for properties like viscosity and density [35,36,37]. As an addition to atomistic calculations, ML enables high-throughput screening of candidate molecules and accelerates the discovery of new materials.

In the area of ML modeling of ionic liquid properties, density prediction has been the subject of a significant number of studies [38]. One of the earliest examples was reported by Valderrama et al. [39], who combined group-contribution theory with an artificial neural network (ANN). The model achieved excellent accuracy, with average absolute deviations of only 0.15% for the training set and 0.26% for an external prediction set (maximum deviation below 2.5%). Barati-Haroon et al. [40] developed a hybrid adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) to predict the densities of neat ionic liquids as well as IL–water mixtures, focusing on various imidazolium-based systems. Using 602 data points covering 146 ILs, their model achieved excellent predictive test-set performance, with overall and an average absolute relative deviation of only 0.66%. Paduszyński [41] compiled an extensive dataset of over 41,000 density values for 2267 ionic liquids and developed a group-contribution QSPR model. The final recommended approach combined multiple linear regression (MLR) for the reference density with a least-squares support vector machine (LSSVM) for temperature–pressure corrections. This model achieved excellent accuracy, with above 0.998 and average errors of about 1%. More recently, Baran and Kloskowski [42] critically evaluated the use of graph neural networks (GNNs) for predicting density, viscosity, and surface tension of ionic liquids. Their study demonstrated that GNNs can effectively process structural information from cations and anions, achieving predictive performance with test-set values up to ~0.95 for density, ~0.69 for viscosity, and ~0.79 for surface tension, while also showing robustness to mislabeled or noisy data. Other interesting studies where deep learning methods were applied for predicting various properties of ionic liquids are by Acar et al. [43], Fan et al. [44], and Abranches et al. [45].

To support the integration of atomistic modeling in molecular research, we developed atomistica.online two years ago as a freely accessible, web-based platform tailored for academic use [46,47]. Launched initially as a single-tool website offering an input file generator for the widely used ORCA [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] molecular modeling code, the platform quickly evolved to address broader computational needs. It was soon expanded with additional input generators and remote execution interfaces for semiempirical codes such as xTB [56,57,58,59], g-xTB [60], and MOPAC [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69], as well as powerful utilities like Multiwfn [70,71,72,73] for wavefunction analysis, Packmol [74,75] for building initial molecular structures, and interfaces for running recently developed ML models for energy prediction and geometry optimization based on Meta’s FAIR initiative [76]. Atomistica.online provided a unified environment where users can upload molecular structures, perform automated atomistic calculations, and access predictive ML models. Today, all these capabilities, along with over 20 specialized applications, are integrated into a comprehensive online application called Atomistica Online 2025, available at https://atomistica.online.

This work aimed to develop robust ML models capable of accurately predicting two key physicochemical properties of imidazolium-based ILs, density and viscosity at room temperature (298 K), based on molecular descriptors derived from simple molecular and atomistic calculations. In addition to the model development, a central goal was to build accessible, user-friendly online applications incorporated within the Atomistica Online 2025 application, enabling researchers to quickly estimate these properties by inputting descriptors obtained from their calculations. The platform is freely available for academic use and is designed to support research, teaching, and early-stage screening of novel ILs. Another important objective was to curate and publish high-quality, descriptor-rich datasets for both properties, which can not only serve as training resources for further ML efforts but can also be expanded and enriched by platform users. Through this work, it was aimed to accelerate the design, understanding, and application of ILs by bridging advanced atomistic modeling with modern data-driven tools.

2. Workflow and Computational Details

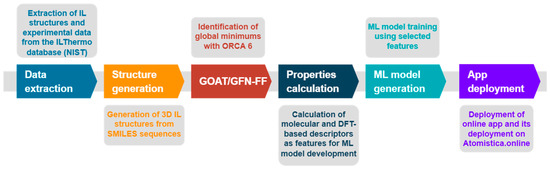

The development of ML models for predicting density and viscosity of imidazolium-based ILs followed a structured multi-step computational workflow, integrating data extraction, structure generation, descriptor calculations, model training, and app deployment (Figure 1). All IL structures used in this study were sourced from the ILThermo database [77] maintained by NIST, which provides a comprehensive collection of experimentally measured thermophysical properties of ILs. However, since ILThermo does not offer 3D molecular structures, the ILThermoPy [72] Python (version 3.10.16) library was used to extract molecular information in the form of SMILES strings for both cations and anions.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the workflow adopted in this work.

To reconstruct 3D structures from SMILES representations, a custom Python pipeline based on the RDKit [78] and Open Babel [79] libraries was developed. This script systematically generated initial 3D geometries of ILs by converting SMILES to spatial coordinates and pre-optimizing each ion using the universal force field (UFF). Ionic liquid ion pairs were assembled by placing the cation and anion at an initial separation distance of 5 Å, ensuring a consistent and non-overlapping starting configuration. This procedure was carried out independently for two datasets: one corresponding to ILs with experimentally measured density and another for those with viscosity data.

Following initial geometry construction, the GOAT [80,81,82] workflow was applied to locate low-energy, likely global minimum structures. The GOAT workflow was used as implemented in the ORCA6 molecular modeling code [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,83]. This step employed the GFN-FF force field [84], developed by Prof. Stefan Grimme and coworkers as a part of their activities in developing modern semiempirical methods [56,57,58,59]. GFN-FF was selected as a practical compromise between computational efficiency and accuracy for high-throughput geometry optimization of ionic liquids. While such systems pose challenges due to strong electrostatic interactions, charge delocalization, and polarization effects, GFN-FF offers a substantial speed advantage compared to semiempirical methods such as GFN2, enabling optimization of hundreds of structures within a reasonable timeframe. Importantly, GFN-FF is derived from the GFN family of methods and has been parameterized and benchmarked on diverse datasets, including GMTKN55, which contains ionic liquid structures. This provided confidence that it could deliver geometries of sufficient quality for descriptor generation, while acknowledging that, as a non-polarizable generic force field, it may be less accurate for highly charged, strongly polarizable systems. Given these considerations, we regard GFN-FF as fully adequate for this initial step, with plans to re-optimize the structures using higher-level methods in our future research efforts.

These optimized geometries were then subjected to calculations of simple molecular descriptors and quantum-mechanically obtained descriptors through single-point energy calculations at the M06-2X/6-31+G(d,p) level using ORCA6 and Maestro. Maestro was used as incorporated in the Schrödinger Materials Science 2024-1 Suite [85,86,87,88,89].

The outcome of this pipeline was two high-quality datasets containing computed descriptors for 434 ILs (density set) and 294 ILs (viscosity set). Each dataset included a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors, including quantum-derived electronic properties, topological indices, geometric features, and thermodynamic quantities such as the heat of formation (calculated using the MOPAC code [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69]). These datasets were used to train and evaluate several ML regression models using Python and scikit-learn, including random forest, gradient boosting, and SVR. Among these, SVR provided the most accurate and robust predictions for both properties.

The units of targets were kg/m3 for density and Pa·s for viscosity. Targets were modeled on the natural-log scale. Model fitting and cross-validation used the log-transformed targets; test-set predictions were back-transformed to the original units for reporting, and all errors and figure axes are shown on the original scales unless stated otherwise.

For the density models (IonIL-IM-D1 and IonIL-IM-D2), the dataset was split into training and test sets using an 80:20 ratio via the train_test_split function from scikit-learn, with a fixed random_state = 42 to ensure reproducibility. The split was performed after descriptor calculation and dataset assembly, ensuring that both sets were processed identically. For the viscosity model (IonIL-IM-V), a slightly different split ratio of 85:15 was applied, also using a fixed random_state = 42. This choice was made to retain a somewhat larger training set for the more complex viscosity prediction task, where data availability is more limited.

Given these considerations, the repeated 5-fold cross-validation results (50 folds in total) are considered the reliable indicators of generalizability for all models. Cross-validation averages performance across multiple randomized partitions, thereby mitigating the influence of any single favorable train–test split and reducing the risk of overestimating model performance.

Trained models were further evaluated through repeated k-fold cross-validation, and their performance was assessed using metrics such as R2, MAE, and RMSE. To improve interpretability and ensure model transparency, a feature importance analysis was performed. The SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) approach was used to identify the most influential molecular descriptors contributing to each property prediction. The final, validated models, IonIL-IM-D1 and IonIL-IM-D2 for density and IonIL-IM-V for viscosity, were deployed as interactive online tools on the atomistica.online platform, enabling users to estimate IL properties based on calculations of descriptors on their ILs.

Feature selection was performed using a structured multi-step procedure designed to reduce redundancy and improve model interpretability. Descriptor importance was first assessed using the random forest algorithm. Their contributions to predictive performance were then evaluated with SHAP. Finally, subsets of descriptors were systematically tested, and those yielding the highest accuracy with the smallest number of features were retained for the final models. This approach resulted in compact descriptor sets.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Machine Learning Models for Density (IonIL-IM-D1 and IonIL-IM-D2)

In designing a predictive model for the density of imidazolium-based ILs, an innovative and practical strategy was adopted. The primary goal was to develop a model with the smallest possible number of features, making it usable in an online application where the user can quickly perform predictions based on calculations for their ionic liquids. At the same time, an alternative model was built with a slightly higher number of features to achieve somewhat improved accuracy, thus balancing simplicity with predictive performance.

All selected descriptors are readily obtainable using free and open-source cheminformatics software, ensuring wide accessibility and ease of use. Under this framework, two SVR models were developed:

- IonIL-IM-D1, a three-feature model designed to maximize simplicity and practical deployability while retaining strong predictive performance.

- IonIL-IM-D2, a seven-feature model incorporating additional physicochemical descriptors to achieve somewhat higher accuracy at the cost of slightly increased complexity.

The details and performance of each model are described in the following subsections.

3.1.1. IonIL-IM-D1

The IonIL-IM-D1 model was designed to predict ionic liquid density using only three informative yet straightforward descriptors: molecular weight, number of atoms, and AlogP. These quantities can be easily obtained using free, open-source software, which supports fast and practical applications, such as online screening tools. Specifically, molecular weight reflects the overall mass of the ionic liquid’s ion pair; the number of atoms serves as a proxy for molecular size and complexity; and AlogP estimates the hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance, correlating with molecular packing and cohesive interactions relevant to density. Permutation importance analysis confirmed the strong relevance of these features, while their simplicity guarantees rapid calculation and broad accessibility for users. Despite this minimal feature set, IonIL-IM-D1 demonstrates robust predictive performance, as discussed in the following sections.

The IonIL-IM-D1 model presented excellent predictive performance on the independent test set. Namely, it achieved an of 0.906, a mean absolute error (MAE) of 28.352, and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 49.803. These results demonstrate the ability of this model to estimate IL density from molecular descriptors accurately. Robustness was confirmed through repeated cross-validation (5 folds × 10 repeats), yielding a mean of 0.835 with a standard deviation of 0.0575 across 50 folds. The final tuned SVR used an RBF kernel with , , and . Together, these results indicate the model’s reliability and suitability for high-throughput screening and rational design of ILs.

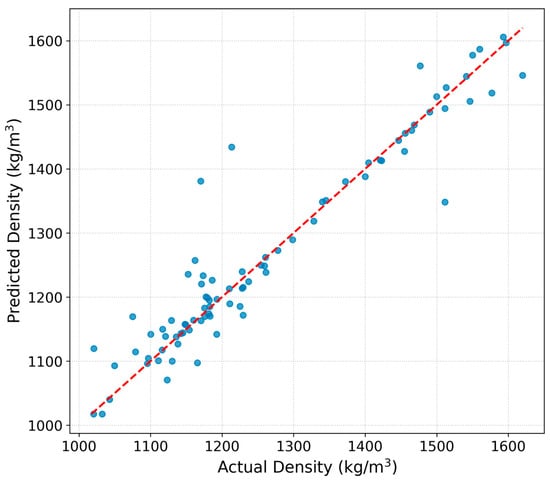

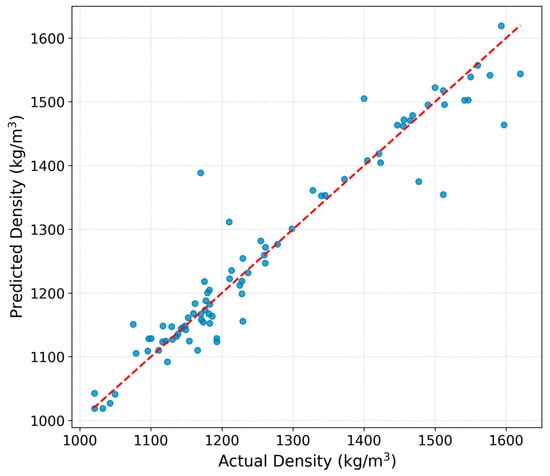

The parity plot (Figure 2) shows excellent agreement between the predicted and measured densities, with the majority of data points clustering tightly around the ideal correlation line. This pattern confirms the high predictive accuracy of the IonIL-IM-D1 model, reflected in a test set of 0.906.

Figure 2.

Predicted vs. experimental density values for the test set using the IonIL-IM-D1 model.

While minor deviations are visible at lower density values, these can reasonably be attributed to the greater structural diversity and conformational flexibility of ionic liquid constituents in that range. Remarkably, this level of performance was achieved using only three simple and easily accessible molecular descriptors, underlining the efficiency and practicality of the model. Overall, the model captures the trend and scale of experimental densities with high reliability, strongly supporting its utility for predictive screening, virtual design, and rapid evaluation of new ILs.

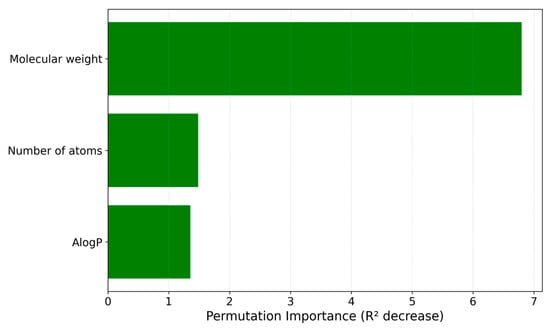

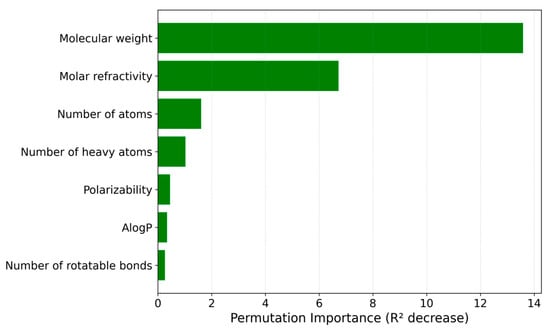

Next, a feature importance analysis based on the permutation importance measure has been performed to gain insights into how individual molecular descriptors contribute to the predictive performance of the IonIL-IM-D1 model (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Permutation-based feature importance plot for the IonIL-IM-D1 model.

Permutation-based importance results revealed that molecular weight is the dominant feature, having the most significant influence on the density predictions of the model. This is consistent with the fundamental role of molecular mass in determining volumetric packing and density in ILs.

The number of atoms emerged as the second most significant contributor. As a descriptor, it describes important aspects of molecular size and complexity, which in turn affect how ILs organize in the condensed phase. The third feature, AlogP, contributed positively to the model’s performance by reflecting the hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance of the ionic liquid components, a property closely linked to cohesive forces and thus to the final density.

Overall, this feature importance profile confirms that even a minimalist descriptor set can provide a robust and physically meaningful basis for predicting ionic liquid densities. This ranking further supports the interpretability of the IonIL-IM-D1 model. It reinforces its suitability for use in accessible, user-friendly online tools aimed at the rapid evaluation and rational design of new ILs.

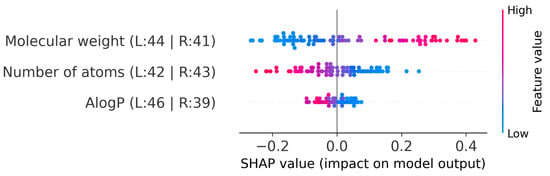

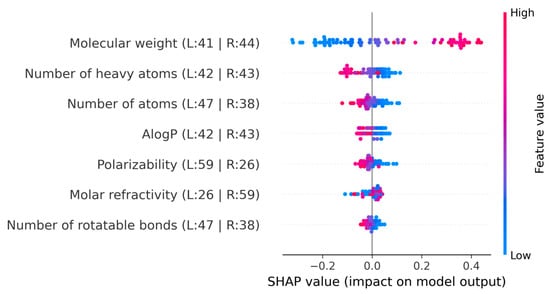

To further explore the IonIL-IM-D1 model, a SHAP analysis was performed. Figure 4 presents the SHAP summary plot, which illustrates the contribution of each descriptor to the model’s density predictions across the test set.

Figure 4.

SHAP summary plot for the IonIL-IM-D1 model.

Consistent with the permutation importance results, molecular weight was again the most influential feature, with SHAP values demonstrating a predominantly positive contribution to predicted density. This confirms that higher molecular weights generally shift the predicted density upwards, as would be expected from fundamental volumetric considerations.

In contrast, the number of atoms showed a predominantly negative SHAP pattern for higher feature values, with red points concentrated on the negative side of the SHAP scale. This suggests that, after accounting for molecular weight, molecules with a larger number of atoms tend to decrease the predicted density. This trend is logical and can be easily explained. Smaller and simpler molecules typically pack more efficiently in the liquid state, which leaves less free volume and thereby increases density. On the other hand, more complex molecules with a greater number of atoms may exhibit branched structures unable to pack tightly, resulting in reduced density.

Finally, AlogP displayed a distribution of SHAP values centered near zero but with both positive and negative effects depending on the specific compound. This pattern may suggest that, while AlogP is less dominant than molecular weight, it still modulates the predicted density through its impact on polarity and hydrophobic interactions within the ionic liquid.

3.1.2. IonIL-IM-D2

The IonIL-IM-D2 model was developed to check whether a larger set of molecular descriptors could enhance predictive accuracy for ionic liquid density. Similar to IonIL-IM-D1, this model incorporated four additional descriptors alongside molecular weight, number of atoms, and AlogP: molar refractivity, polarizability, number of rotatable bonds, and number of heavy atoms. These features can also be easily calculated using free and open-source cheminformatics tools, maintaining accessibility. By expanding the number of descriptors, IonIL-IM-D2 aims to achieve improved performance while preserving interpretability and practical usability. Its details and results are discussed in the following sections.

The IonIL-IM-D2 model achieved better predictive performance on the independent test set, achieving an of 0.922, a MAE of 27.00 kg/m3, and an RMSE of 45.47 kg/m3. The final tuned SVR in this case used an RBF kernel with , , and . Compared to IonIL-IM-D1, these results indicate a modest but meaningful improvement in predictive accuracy, reflecting the result of incorporating additional molecular descriptors. Robustness was also improved, confirmed by repeated cross-validation (5 folds × 10 repeats), yielding a mean R2 of 0.8846 with a standard deviation of 0.0474 across 50 folds. These values are slightly better and indicate higher stability than the corresponding values for IonIL-IM-D1.

In Figure 5, the differences between measured and predicted values are presented. The results indicate an excellent agreement between predicted and measured densities, with the majority of points clustering closely along the ideal correlation line. Compared to the IonIL-IM-D1 model, the IonIL-IM-D2 model achieves slightly improved alignment across the whole density range, confirming its enhanced predictive accuracy.

Figure 5.

Predicted vs. experimental density values for the test set using the IonIL-IM-D2 model.

Minor deviations are still observed at lower densities, likely due to structural variability among the ILs; however, the model captures both trends and absolute values with high accuracy overall. These results further support the IonIL-IM-D2 model’s practical applicability for predictive screening and rational design of new ILs.

To better understand how each of the seven input descriptors influenced the IonIL-IM-D2 model, a permutation-based feature importance analysis was again performed, and the results are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Permutation-based feature importance plot for the IonIL-IM-D2 model.

Consistent with the IonIL-IM-D1 results, molecular weight was once again recognized as the most significant predictor, indicating its fundamental influence on the density of ILs. The second most important feature was molar refractivity, which captures contributions from electronic polarizability and molecular packing characteristics. The number of heavy atoms contributed meaningfully to the model, showing it is relevant in describing the backbone structure and overall size of the ionic liquid’s ion pair. Descriptors such as the number of atoms, polarizability, AlogP, and number of rotatable bonds showed smaller, though still noticeable, contributions to the overall predictive performance. These features likely captured subtler aspects of molecular flexibility, polarity, and cohesive interactions that, while not dominant, help fine-tune the model’s predictions.

Last, regarding the models for density, the SHAP analysis for the IonIL-IM-D2 model has been performed (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

SHAP summary plot for the IonIL-IM-D2 model.

The molecular weight showed a high positive contribution in SHAP analysis, with higher values contributing to increased predicted densities. Both the number of heavy atoms and the number of atoms showed similar influences, generally reducing predicted density as their values increased. This suggests that larger or more structurally complex ion pairs may hinder tight packing and introduce more free volume, thereby lowering density.

AlogP displayed SHAP values centered around zero, with a balanced distribution of positive and negative effects depending on the compound, indicating a subtle and context-dependent contribution related to hydrophobicity and polarity. Polarizability contributed slightly to the decrease in density predictions, suggesting that highly polarizable molecules may have less efficient packing due to their ability to distort and interact. Molar refractivity showed some small positive SHAP values, which indicates that structures with higher refractivity may favor stronger cohesive interactions and enhanced packing, thereby marginally increasing density. The number of rotatable bonds exhibited SHAP values tightly located around zero, which indicates a limited direct role in density prediction. However, it may still interact indirectly with other structural features.

Overall, these SHAP results confirm that, while molecular weight remains the dominant factor, the additional descriptors in IonIL-IM-D2 help capture more subtle effects relevant to ionic liquid density, supporting the model’s accuracy and interpretability for practical screening applications.

3.2. ML Model for Viscosity (IonIL-IM-V)

In addition to density modeling, the SVR approach was used again to develop an ML model for predicting the viscosity of imidazolium-based ILs, referred to as IonIL-IM-V. Unlike the density models, IonIL-IM-V required a broader and more complex feature set to achieve acceptable performance, ultimately using nine descriptors. Several of these descriptors, such as quantities related to average local ionization energy (ALIE), electrostatic potential, and the energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), were derived from quantum mechanical calculations at the DFT level, reflecting the greater complexity of modeling viscosity compared to density. Minimal value of ESP (ESP min) and mean value of ALIE (ALIE mean) were expressed in kcal/mol, negative variance of ESP (ESP neg variance) was expressed in (kcal/mol)2, while LUMO was expressed in a.u. Although the model did not reach the same level of robustness as IonIL-IM-D1 or IonIL-IM-D2, it still achieved promising predictive results on the test set, suggesting it could serve as a valuable starting point for future adjustments and the development of better prediction models. Details of its structure, performance, and interpretability are presented in the following sections.

The IonIL-IM-V model achieved an R2 of 0.918 on the independent test set, with a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.175 and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.280. Using the final tuned configuration, the model is an RBF-kernel SVR with hyperparameters , , and . While these numbers suggest strong predictive accuracy on a single hold-out set, the mean cross-validation R2 was considerably lower at 0.5573, with a relatively high standard deviation of 0.1111 across 50 folds. This large gap between the static test split and the averaged CV performance clearly indicates that the model suffers from limited generalizability and is prone to overfitting. Such a discrepancy is a known phenomenon when a specific train–test split happens to be particularly favorable, and it underlines the importance of using cross-validation as the more reliable indicator of expected performance on new, unseen data.

It is important to mention that viscosity is a significantly more complex property than density, because it depends on numerous factors, including molecular size, shape, intermolecular forces, ion pairing, and dynamic interactions within the liquid phase. Capturing all of these contributions in a single predictive framework is inherently challenging, especially when the dataset is limited in both size and diversity. In this context, IonIL-IM-V should be seen as a proof-of-concept model that demonstrates the feasibility of viscosity prediction for imidazolium-based ILs but also makes clear the need for larger, more balanced datasets and advanced feature engineering to achieve higher generalizability.

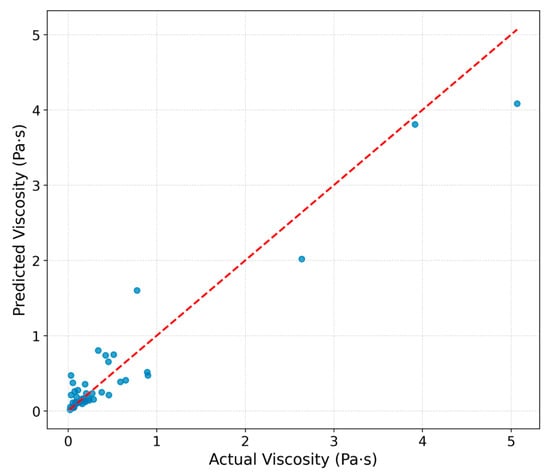

The parity plot for IonIL-IM-V (Figure 8) highlights good alignment to a certain extent between predicted and measured viscosities, particularly within the lower viscosity range, where most of the data points are concentrated. However, a clear imbalance in the dataset is evident, with far fewer samples at higher viscosities.

Figure 8.

Predicted vs. experimental viscosity values for the test set using the IonIL-IM-V model.

This imbalance, coming from the current limitation of the ILthermo dataset when it comes to the imidazolium-based ionic liquids, has direct implications for the model’s performance and generalizability. Because the dense cluster of low-viscosity samples dominates the training process, the model can learn patterns in this region very effectively, while the sparsely represented high-viscosity points are more likely to be treated as noise. This imbalance is therefore a possible contributor to the observed overfitting and the large discrepancy between the optimistic R2 value obtained on the static test set and the considerably lower mean cross-validation score.

The lower number of high-viscosity data likely contributes to the increased scatter and larger errors observed for these points. Such an imbalance is expected to a certain extent because reliable measurements of highly viscous ILs are experimentally more demanding and less frequently reported. Nevertheless, the model showed relatively significant accuracy in the low-viscosity region, which marks it as a promising first step. To improve generalization and reduce overfitting, future work should focus on rebalancing the dataset by incorporating a greater proportion of high-viscosity IL measurements, thereby ensuring that the model learns from a more uniform distribution of the target property.

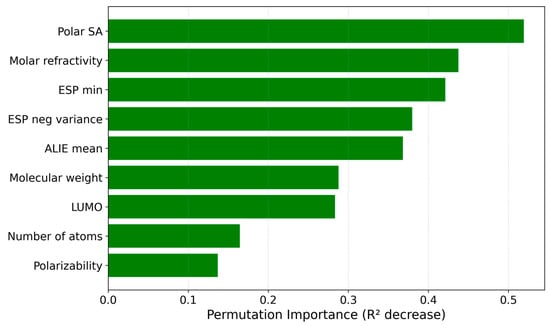

Further, a permutation-based feature importance study has been performed to understand better how each of the nine input descriptors influenced the IonIL-IM-V model (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Permutation-based feature importance plot for the IonIL-IM-V model.

The permutation importance analysis highlighted molar refractivity and polar surface area (Polar SA) as the most influential features for predicting ionic liquid viscosity, suggesting that molecular volume and accessible surface area play a significant role in flow resistance and ion mobility. ESP min and ESP negative variance also ranked highly. They showed the importance of charge distribution and electrostatic interactions in controlling viscosity. Furthermore, ALIE mean, which reflects local ionization energies, and molecular weight contributed meaningfully, indicating the importance of molecular size and stability. Features describing frontier orbital energy (LUMO), atomic count (number of atoms), and polarizability showed additional relevance, supporting the notion that viscosity arises from a complex interplay of geometric, electronic, and dynamic molecular properties. These insights could inform future feature engineering by emphasizing descriptors linked to molecular packing, intermolecular forces, and ion–ion interactions, thereby further improving the IonIL-IM-V model. Further, the SHAP analysis for the IonIL-IM-V model has been performed (Figure 10).

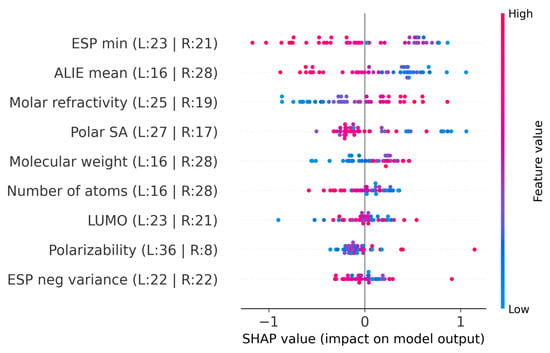

Figure 10.

SHAP summary plot for the IonIL-IM-V model.

The SHAP analysis presented in Figure 10 was crucial for understanding the importance of individual features in the IonIL-IM-V model. Among the most impactful descriptors, ESP minimum and ALIE mean exhibited clear inverse contributions, with lower ESP minimum values and lower ALIE mean values tending to decrease the predicted viscosity. Molar refractivity showed a direct positive contribution, where higher values increased the model’s viscosity estimates. This can be interpreted as the role of molecular volume in reducing ion mobility. Polar SA showed a relatively strong negative influence, meaning that larger surface areas lowered predicted viscosity, potentially due to higher charge delocalization and reduced ion pairing strength. Molecular weight and number of atoms displayed similar importance in terms of magnitude but in opposite directions: higher molecular weight increased the predicted viscosity, while a higher number of atoms tended to decrease it, highlighting subtle differences between mass-driven resistance and structural complexity. Finally, LUMO energy, ESP negative variance, and polarizability showed mixed influences, with both higher and lower values variably shifting the predictions toward increased or decreased viscosity.

It is important to note that these interpretations are derived from an overfit model and, therefore, may not represent true physical structure–property relationships but rather reflect the patterns the model learned to fit the specific training data. As such, while the SHAP results offer insight into how the model processed the input features, they should be interpreted with caution, particularly in the context of the limited generalizability demonstrated by the IonIL-IM-V model.

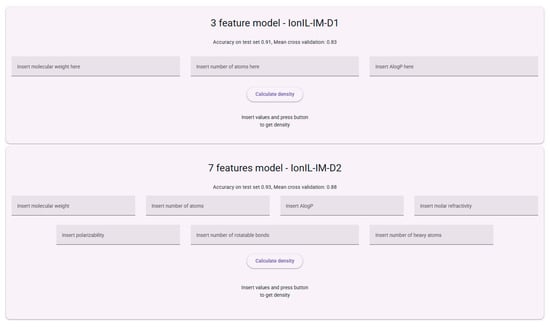

3.3. Online Applications for Predicting Properties of Ionic Liquids and Datasets

The IonIL-IM-D1, IonIL-IM-D2, and IonIL-IM-V models are freely available as interactive web applications hosted on the Atomistica Online 2025 application (https://atomistica.online). These applications are designed to make predictive modeling of ILs highly accessible to both experts and non-experts in materials science. By inputting a set of pre-calculated molecular descriptors, users can instantly obtain predicted values for either the density or viscosity of their ionic liquid candidates.

The web interface is streamlined for intuitive use. Users first select the property they wish to predict from the main menu on the left-hand side (via the “IL Density Predictor” and “IL Viscosity Predictor” links). For density prediction, two models are available: IonIL-IM-D1 and IonIL-IM-D2. Interfaces for using these models are presented in Figure 11. Users can enter the descriptor values manually or via copy–paste, and the predicted density is displayed immediately after pressing the “Calculate density” button.

Figure 11.

The interface for using the IonIL-IM-D1 and IonIL-IM-D2 ML models.

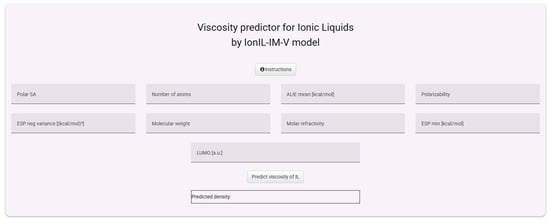

For viscosity, the model requires nine molecular descriptors, including quantum-mechanically derived features, which reflect the increased complexity of this property (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

The interface for using the IonIL-IM-V model.

These applications are helpful for teaching, research, and exploratory design of ILs by eliminating the need for coding, software installation, or model retraining. They are particularly valuable for early-stage hypothesis testing, enabling researchers to screen candidate ILs before starting time- and resource-intensive synthesis or experimental characterization. The platform is entirely web-based and optimized for both desktop and mobile use, free for academic and teaching purposes.

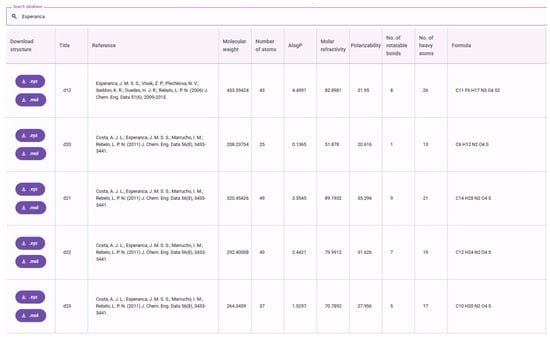

In addition to the predictive models, each corresponding application includes, at the bottom of the page, curated and searchable databases of the ILs used to train the density and viscosity models (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Searchable and interactive dataset for density, used for the generation of IonIL-IM-D models.

These interactive and searchable datasets, developed as part of this study, include 434 imidazolium-based ILs for density and 293 ILs for viscosity. Each entry is annotated with experimentally measured properties and a suite of molecular descriptors. For every ionic liquid in the datasets, users can download optimized global minimum structures, available in both xyz and mol formats. These optimized structures can be used immediately for property calculations or serve as reliable starting points for further re-optimizations at higher levels of theory. Each table entry also includes the molecular formula, SMILES representation, and the full reference citation associated with the IL.

Additionally, all GOAT/GFN-FF-optimized structures are available in bundled archives. The datasets are also provided as downloadable csv files containing all calculated molecular descriptors, making them suitable for direct use in ML workflows and further analysis.

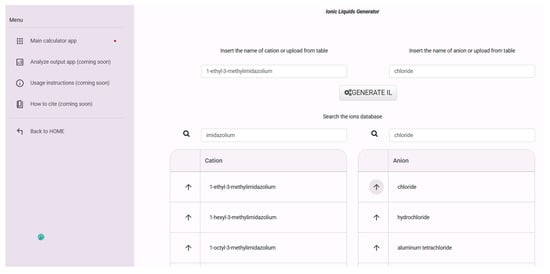

3.4. Ionic Liquid Structure Generator

Last but not least, one more outcome of this study is presented: the development of a simple online structure generator for ILs, available through the Atomistica Online 2025 application. This tool was developed using a systematic approach: first, all unique ionic liquid structures were extracted as SMILES strings from the ILThermoPy Python library. From this curated list of ILs, all cations and anions were programmatically separated and stored in two distinct and searchable tables. Each ion is labeled with its IUPAC convention name, allowing users to browse or filter through them easily. Since it is challenging to know the exact names of ions for generating a certain IL, all ions are available in two easily searchable tables with buttons to invoke ions for the generation of IL. In the search field for cations and anions, it is sufficient to type a part of the desired ion’s name, and the table will be sorted (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Screenshot from the online IL generator.

The platform enables users to select any combination of cation and anion, upon which a 3D structure of the resulting ion pair is generated and pre-optimized using the universal force field (UFF). This process provides immediate access to chemically meaningful starting geometries. The tool addresses a fundamental need in the field of ionic liquid design and modeling. The chemical diversity of ILs is virtually limitless, with millions of theoretically possible combinations of cations and anions. However, generating realistic, pre-optimized 3D structures for these combinations remains a tedious and time-consuming task for most researchers, particularly those without a strong background in programming or computation. By automating this step, the structure generator makes easy access to ready-to-use IL geometries, significantly simplifying the process of exploring new ionic liquid systems, performing quantum mechanical or MD calculations, or integrating structures into ML workflows.

Approximately 1300 cations and 400 anions were extracted from the database, meaning that users can theoretically generate over half a million unique ion pairs. Because the generated structures are UFF-pre-optimized and provided in a standardized format, they can be used directly for further optimization (e.g., via GOAT or DFT) or for generating molecular descriptors. Furthermore, a generated intermolecular system consisting of a cation and an anion allows users to generate MD systems through the Online Packmol application of Atomistica Online 2025, which uses the famous Packmol program [74,75] in the background.

4. Conclusions

In this work, the development, validation, and deployment of ML models designed to predict the density and viscosity of imidazolium-based ILs at room temperature (298 K) using molecular descriptors derived from simple and atomistic calculations have been presented. By collecting high-quality datasets and applying clear computational workflows, including geometry optimization via the GOAT protocol using the GFN-FF force field, a solid foundation has been established for building interpretable, robust, and accessible predictive models.

For density prediction, two models were developed: IonIL-IM-D1, which utilized only three simple descriptors (molecular weight, number of atoms, and AlogP), and IonIL-IM-D2, which employed seven descriptors to capture more complex structural and electronic features. IonIL-IM-D1 achieved a test set R2 of 0.91, MAE of 28.35 kg/m3, and RMSE of 49.80 kg/m3, with a mean cross-validation R2 of 0.84. These results indicated that even a minimal descriptor set can yield high predictive accuracy. IonIL-IM-D2 further improved performance, achieving a test set R2 of 0.92, MAE of 27.00 kg/m3, and RMSE of 45.47 kg/m3, with a mean cross-validation R2 of 0.88. These results confirm that density is a property well-suited to ML prediction using readily accessible molecular features.

Viscosity prediction was a greater challenge due to the more complex nature of this property. The IonIL-IM-V model utilized nine descriptors, including several derived from DFT calculations such as ALIE, ESP, and frontier orbital energies. Despite this complexity, the model achieved a respectable test set R2 of 0.92, MAE of 0.175, and RMSE of 0.280. While cross-validation results indicated reduced robustness (mean R2 of 0.56 with higher variance), the model provides a solid foundation for further development and illustrates the feasibility of using ML to tackle even challenging physicochemical properties. However, the limited size of the viscosity dataset and the strong sensitivity of viscosity to experimental conditions introduce additional sources of uncertainty. Furthermore, the reliance on computationally demanding quantum descriptors may reduce the model’s general applicability, highlighting the need for future work on larger datasets and simplified descriptor sets.

All three models are deployed as web-based applications within atomistica.online platform (https://atomistica.online), which was developed to ensure maximum accessibility for both researchers and students. Users can input pre-calculated descriptors and obtain immediate predictions for density or viscosity without requiring coding expertise, software installation, or model retraining. The platform also includes searchable and interactive databases of all ILs used to train the models, each annotated with descriptors and experimental values. Users can also:

- Download optimized structures obtained via GOAT/GFN-FF in both xyz and mol formats;

- Access and download complete datasets as csv files containing all calculated molecular descriptors;

- Download bundled archives containing all optimized IL structures used in model development.

Additionally, we also developed an ionic liquid structure generator, which theoretically enables users to create over 500,000 cation–anion combinations using a curated library of ~1300 cations and ~400 anions. The resulting structures are automatically built and pre-optimized using the UFF, making them ideal starting points for further quantum mechanical or ML-based investigations.

Altogether, this work delivers a unified framework for data-driven IL modeling by combining simple molecular descriptors, atomistic calculations, ML, and online software engineering.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and S.J.A.; methodology, S.A. and S.J.A.; software, S.A.; validation, S.A. and S.J.A.; formal analysis, S.A. and S.J.A.; investigation, S.A. and S.J.A.; resources, S.A.; data curation, S.A. and S.J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A. and S.J.A.; visualization, S.A. and S.J.A.; supervision, S.A.; project administration, S.A. and S.J.A.; funding acquisition, S.A. and S.J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Grant Nos. 451-03-137/2025-03/200125 and 451-03-136/2025-03/200125).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The Association for the International Development of Academic and Scientific Collaboration (https://aidasco.org/ accessed on 1 July 2025.), Centrohem d.o.o. (https://www.centrohem.co.rs/ accessed on 1 July 2025.), and Serbian Natural History Society (https://spd.rs/ accessed on 1 July 2025.), who supported the research by providing part of the computer resources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kaur, G.; Kumar, H.; Singla, M. Diverse Applications of Ionic Liquids: A Comprehensive Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 351, 118556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welton, T. Ionic Liquids: A Brief History. Biophys. Rev. 2018, 10, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angell, C.A.; Ansari, Y.; Zhao, Z. Ionic Liquids: Past, Present and Future. Faraday Discuss. 2011, 154, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Dai, C.; Hallett, J.; Shiflett, M. Introduction: Ionic Liquids for Diverse Applications. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 7533–7535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabre, E.; Murshed, S.M.S. A Review of the Thermophysical Properties and Potential of Ionic Liquids for Thermal Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 15861–15879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshina, J.L.; Rogers, R.D. Ionic Liquids: New Forms of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients with Unique, Tunable Properties. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 11894–11953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, D.; Drummond, C.J.; Greaves, T.L. Solvation Properties of Protic Ionic Liquids and Molecular Solvents. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 22, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordness, O.; Brennecke, J.F. Ion Dissociation in Ionic Liquids and Ionic Liquid Solutions. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12873–12902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyckens, D.J.; Henderson, L.C. A Review of Solvate Ionic Liquids: Physical Parameters and Synthetic Applications. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Pathak, A.D.; Lakma, A.; Sharma, C.S.; Sahu, K.K.; Singh, A.K. Synthesis, Characterization and Application of a Non-Flammable Dicationic Ionic Liquid in Lithium-Ion Battery as Electrolyte Additive. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, A.; Shi, K.; Hagen, E.; Wang, Y.; Biswas, P.; Zachariah, M.R. Role of Anions in the Electrochemical Modulation of Flammability of Ionic Liquids. Combust. Flame 2025, 275, 113994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Fernández, I.; Pino, V. Green Solvents in Analytical Chemistry. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2019, 18, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H.; Verpoorte, R. Green Solvents for the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Natural Products Using Ionic Liquids and Deep Eutectic Solvents. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 26, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedeva, O.; Kultin, D.; Kustov, L. Electrochemical Synthesis of Unique Nanomaterials in Ionic Liquids. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrinha, Á.; Oliveira, T.M.B.F.; Ribeiro, F.W.P.; de Lima-Neto, P.; Correia, A.N.; Morais, S. (Bio)Sensing Strategies Based on Ionic Liquid-Functionalized Carbon Nanocomposites for Pharmaceuticals: Towards Greener Electrochemical Tools. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, S.S.; Maciel Filho, R. Are Ionic Liquids Eco-Friendly? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 157, 112039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Mary, Y.S.; Resmi, K.S.; Narayana, B.; Sarojini, S.B.K.; Armaković, S.; Armaković, S.J.; Vijayakumar, G.; Alsenoy, C.V.; Mohan, B.J. Synthesis and Spectroscopic Study of Two New Pyrazole Derivatives with Detailed Computational Evaluation of Their Reactivity and Pharmaceutical Potential. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1181, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, Y.S.; Mary, Y.S.; Thomas, R.; Narayana, B.; Samshuddin, S.; Sarojini, B.K.; Armaković, S.; Armaković, S.J.; Pillai, G.G. Theoretical Studies on the Structure and Various Physico-Chemical and Biological Properties of a Terphenyl Derivative with Immense Anti-Protozoan Activity. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2021, 41, 825–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, K.; Kumar, V.S.; Armaković, S.J.; Armaković, S.; Mary, Y.S.; Thomas, R.; Popoola, S.A.; Almohammedi, A.R.; Roxy, M.S.; Al-Saadi, A.A. Spectral Characterization, Thermochemical Studies, Periodic SAPT Calculations and Detailed Quantum Mechanical Profiling Various Physico-Chemical Properties of 3,4-Dichlorodiuron. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 228, 117580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beegum, S.; Mary, Y.S.; Mary, Y.S.; Thomas, R.; Armaković, S.; Armaković, S.J.; Zitko, J.; Dolezal, M.; Van Alsenoy, C. Exploring the Detailed Spectroscopic Characteristics, Chemical and Biological Activity of Two Cyanopyrazine-2-Carboxamide Derivatives Using Experimental and Theoretical Tools. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 224, 117414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Otaibi, J.S.; Mary, Y.S.; Armaković, S.; Thomas, R. Hybrid and Bioactive Cocrystals of Pyrazinamide with Hydroxybenzoic Acids: Detailed Study of Structure, Spectroscopic Characteristics, Other Potential Applications and Noncovalent Interactions Using SAPT. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1202, 127316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielenica, A.; Beegum, S.; Mary, Y.S.; Mary, Y.S.; Thomas, R.; Armaković, S.; Armaković, S.J.; Madeddu, S.; Struga, M.; Van Alsenoy, C. Experimental and Computational Analysis of 1-(4-Chloro-3-Nitrophenyl)-3-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)Thiourea. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1205, 127587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Arriagada, D. Intermolecular Driving Forces on the Adsorption of DNA/RNA Nucleobases to Graphene and Phosphorene: An Atomistic Perspective from DFT Calculations. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 325, 115229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behbahani, A.F.; Rissanou, A.; Kritikos, G.; Doxastakis, M.; Burkhart, C.; Polińska, P.; Harmandaris, V.A. Conformations and Dynamics of Polymer Chains in Cis and Trans Polybutadiene/Silica Nanocomposites through Atomistic Simulations: From the Unentangled to the Entangled Regime. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 6173–6189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, C.; Levchenko, S.V. First-Principles Atomistic Thermodynamics and Configurational Entropy. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, A.S.; Pinheiro, G.A.; Lourenço, T.C.; Lopes, M.C.; Quiles, M.G.; Dias, L.G.; Da Silva, J.L.F. Screening of the Role of the Chemical Structure in the Electrochemical Stability Window of Ionic Liquids: DFT Calculations Combined with Data Mining. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 4702–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusik, I.; Kook, M.; Pärna, R.; Kivimäki, A.; Käämbre, T.; Reisberg, L.; Kikas, A.; Kisand, V. The Electronic Structure of Ionic Liquids Based on the TFSI Anion: A Gas Phase UPS and DFT Study. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 294, 111580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardak, C.; Atac, A.; Bardak, F. Effect of the External Electric Field on the Electronic Structure, Spectroscopic Features, NLO Properties, and Interionic Interactions in Ionic Liquids: A DFT Approach. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 273, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Jiang, S.; Zheng, P.; Zhou, D.; Qiu, J.; Gao, L. Molecular Mechanism for the Interaction of Natural Products with Ionic Liquids: Insights from MD and DFT Study. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 399, 124440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Vijayalakshmi, K.P.; George, B.K. Kinetic Stability of Imidazolium Cations and Ionic Liquids: A Frontier Molecular Orbital Approach. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 276, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yan, F.; Yu, T.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, T. Density Functional Theory Study of Adsorption of Ionic Liquids on Graphene Oxide Surface. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 245, 116946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, W.P.; Barzilay, R. Applications of Deep Learning in Molecule Generation and Molecular Property Prediction. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noé, F.; Tkatchenko, A.; Müller, K.-R.; Clementi, C. Machine Learning for Molecular Simulation. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2020, 71, 361–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigh, D.S.; Goodman, J.M.; Lapkin, A.A. A Review of Molecular Representation in the Age of Machine Learning. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaei-Kohani, R.; Ali Madani, S.; Mousavi, S.-P.; Atashrouz, S.; Abedi, A.; Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A.; Mohaddespour, A. Machine Learning Assisted Structure-Based Models for Predicting Electrical Conductivity of Ionic Liquids. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 362, 119509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbitt, N.S.; Allers, J.P.; Harvey, J.A.; Poe, D.; Wemhoner, J.D.; Keth, J.; Greathouse, J.A. Machine Learning Predictions of Diffusion in Bulk and Confined Ionic Liquids Using Simple Descriptors. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2023, 8, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racki, A.; Paduszyński, K. Recent Advances in the Modeling of Ionic Liquids Using Artificial Neural Networks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 3161–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoukos, S.; Philippi, F.; Malaret, F.; Welton, T. A Review on Machine Learning Algorithms for the Ionic Liquid Chemical Space. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 6820–6843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valderrama, J.O.; Reátegui, A.; Rojas, R.E. Density of Ionic Liquids Using Group Contribution and Artificial Neural Networks. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 3254–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati-Harooni, A.; Najafi-Marghmaleki, A.; Mohammadi, A.H. ANFIS Modeling of Ionic Liquids Densities. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 224, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paduszyński, K. Extensive Databases and Group Contribution QSPRs of Ionic Liquids Properties. 1. Density. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 5322–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, K.; Kloskowski, A. Graph Neural Networks and Structural Information on Ionic Liquids: A Cheminformatics Study on Molecular Physicochemical Property Prediction. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 10542–10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acar, Z.; Nguyen, P.; Lau, K.C. Machine-Learning Model Prediction of Ionic Liquids Melting Points. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Xue, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Chen, Y.; Cui, P.; Sun, S.; Qi, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y. Modeling the Toxicity of Ionic Liquids Based on Deep Learning Method. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2023, 176, 108293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abranches, D.O.; Zhang, Y.; Maginn, E.J.; Colón, Y.J. Sigma Profiles in Deep Learning: Towards a Universal Molecular Descriptor. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 5630–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaković, S.; Armaković, S.J. Atomistica.Online—Web Application for Generating Input Files for ORCA Molecular Modelling Package Made with the Anvil Platform. Mol. Simul. 2023, 49, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaković, S.; Armaković, S.J. Online and Desktop Graphical User Interfaces for Xtb Programme from Atomistica.Online Platform. Mol. Simul. 2024, 50, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakos, D.G.; Guo, Y.; Neese, F. Comprehensive Benchmark Results for the Domain Based Local Pair Natural Orbital Coupled Cluster Method (DLPNO-CCSD(T)) for Closed- and Open-Shell Systems. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Riplinger, C.; Liakos, D.G.; Becker, U.; Saitow, M.; Neese, F. Linear Scaling Perturbative Triples Correction Approximations for Open-Shell Domain-Based Local Pair Natural Orbital Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles Theory [DLPNO-CCSD(T0/T)]. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 024116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. The SHARK Integral Generation and Digestion System. J. Comput. Chem. 2022, 44, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teale, A.M.; Helgaker, T.; Savin, A.; Adamo, C.; Aradi, B.; Arbuznikov, A.V.; Ayers, P.W.; Baerends, E.J.; Barone, V.; Calaminici, P.; et al. DFT Exchange: Sharing Perspectives on the Workhorse of Quantum Chemistry and Materials Science. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 28700–28781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neese, F.; Wennmohs, F.; Hansen, A.; Becker, U. Efficient, Approximate and Parallel Hartree–Fock and Hybrid DFT Calculations. A ‘Chain-of-Spheres’ Algorithm for the Hartree–Fock Exchange. Chem. Phys. 2009, 356, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software Update: The ORCA Program System, Version 4.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018, 8, e1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. The ORCA Program System. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F.; Wennmohs, F.; Becker, U.; Riplinger, C. The ORCA Quantum Chemistry Program Package. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 224108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannwarth, C.; Caldeweyher, E.; Ehlert, S.; Hansen, A.; Pracht, P.; Seibert, J.; Spicher, S.; Grimme, S. Extended Tight-Binding Quantum Chemistry Methods. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2021, 11, e1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannwarth, C.; Ehlert, S.; Grimme, S. GFN2-xTB—An Accurate and Broadly Parametrized Self-Consistent Tight-Binding Quantum Chemical Method with Multipole Electrostatics and Density-Dependent Dispersion Contributions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 1652–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlert, S.; Stahn, M.; Spicher, S.; Grimme, S. Robust and Efficient Implicit Solvation Model for Fast Semiempirical Methods. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 4250–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Bannwarth, C.; Shushkov, P. A Robust and Accurate Tight-Binding Quantum Chemical Method for Structures, Vibrational Frequencies, and Noncovalent Interactions of Large Molecular Systems Parametrized for All Spd-Block Elements (Z = 1–86). J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 1989–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froitzheim, T.; Müller, M.; Hansen, A.; Grimme, S. G-xTB: A General-Purpose Extended Tight-Binding Electronic Structure Method For the Elements H to Lr (Z = 1–103). ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dewar, M.J.S.; Hashmall, J.A.; Venier, C.G. Ground States of Conjugated Molecules. IX. Hydrocarbon Radicals and Radical Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 1953–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, M.J.S.; Zoebisch, E.G.; Healy, E.F.; Stewart, J.J.P. Development and Use of Quantum Mechanical Molecular Models. 76. AM1: A New General Purpose Quantum Mechanical Molecular Model. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 3902–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, M.J.S.; Thiel, W. Ground States of Molecules. 38. The MNDO Method. Approximations and Parameters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 4899–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, G.B.; Freire, R.O.; Simas, A.M.; Stewart, J.J.P. RM1: A Reparameterization of AM1 for H, C, N, O, P, S, F, Cl, Br, and I. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.J.P. Optimization of Parameters for Semiempirical Methods I. Method. J. Comput. Chem. 1989, 10, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.J.P. Optimization of Parameters for Semiempirical Methods II. Applications. J. Comput. Chem. 1989, 10, 221–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.J.P. MOPAC: A Semiempirical Molecular Orbital Program. J. Comput. Mol. Des. 1990, 4, 1–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.J.P. Optimization of Parameters for Semiempirical Methods V: Modification of NDDO Approximations and Application to 70 Elements. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 13, 1173–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, W.; Voityuk, A.A. Extension of the MNDO Formalism Tod Orbitals: Integral Approximations and Preliminary Numerical Results. Theoret. Chim. Acta 1992, 81, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. A Comprehensive Electron Wavefunction Analysis Toolbox for Chemists, Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 082503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, Q. Van Der Waals Potential: An Important Complement to Molecular Electrostatic Potential in Studying Intermolecular Interactions. J. Mol. Model. 2020, 26, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Manzetti, S. Wavefunction and Reactivity Study of Benzo[a]Pyrene Diol Epoxide and Its Enantiomeric Forms. Struct. Chem. 2014, 25, 1521–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, J.M.; Martínez, L. Packing Optimization for Automated Generation of Complex System’s Initial Configurations for Molecular Dynamics and Docking. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, L.; Andrade, R.; Birgin, E.G.; Martínez, J.M. PACKMOL: A Package for Building Initial Configurations for Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2157–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharing New Breakthroughs and Artifacts Supporting Molecular Property Prediction, Language Processing, and Neuroscience. Available online: https://ai.meta.com/blog/meta-fair-science-new-open-source-releases/ (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Ionic Liquids Database—ILThermo. Available online: https://ilthermo.boulder.nist.gov/ (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Landrum, G.; Tosco, P.; Kelley, B.; Rodriguez, R.; Cosgrove, D.; Vianello, R.; Sriniker; Gedeck, P.; Jones, G.; Kawashima, E.; et al. Rdkit/Rdkit: 2025_03_6 (Q1 2025) Release 2025. Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open Babel: An Open Chemical Toolbox. J. Cheminformatics 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, B. GOAT: A Global Optimization Algorithm for Molecules and Atomic Clusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202500393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goedecker, S. Minima Hopping: An Efficient Search Method for the Global Minimum of the Potential Energy Surface of Complex Molecular Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 9911–9917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wales, D.J.; Doye, J.P.K. Global Optimization by Basin-Hopping and the Lowest Energy Structures of Lennard-Jones Clusters Containing up to 110 Atoms. J. Phys. Chem. A 1997, 101, 5111–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software Update: The ORCA Program System—Version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicher, S.; Grimme, S. Robust Atomistic Modeling of Materials, Organometallic, and Biochemical Systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15665–15673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Balduf, T.; Beachy, M.D.; Bennett, M.C.; Bochevarov, A.D.; Chien, A.; Dub, P.A.; Dyall, K.G.; Furness, J.W.; Halls, M.D.; et al. Quantum Chemical Package Jaguar: A Survey of Recent Developments and Unique Features. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 052502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Halls, M.D.; Vadicherla, T.R.; Friesner, R.A. Pseudospectral Implementations of Long-Range Corrected Density Functional Theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2021, 42, 2089–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Hughes, T.; Giesen, D.; Halls, M.D.; Goldberg, A.; Vadicherla, T.R.; Sastry, M.; Patel, B.; Sherman, W.; Weisman, A.L.; et al. Highly Efficient Implementation of Pseudospectral Time-Dependent Density-Functional Theory for the Calculation of Excitation Energies of Large Molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 2016, 37, 1425–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, L.D.; Bochevarov, A.D.; Watson, M.A.; Hughes, T.F.; Rinaldo, D.; Ehrlich, S.; Steinbrecher, T.B.; Vaitheeswaran, S.; Philipp, D.M.; Halls, M.D. Automated Transition State Search and Its Application to Diverse Types of Organic Reactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 5780–5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochevarov, A.D.; Harder, E.; Hughes, T.F.; Greenwood, J.R.; Braden, D.A.; Philipp, D.M.; Rinaldo, D.; Halls, M.D.; Zhang, J.; Friesner, R.A. Jaguar: A High-Performance Quantum Chemistry Software Program with Strengths in Life and Materials Sciences. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2013, 113, 2110–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).