Abstract

Distributed cloud networks spanning multiple jurisdictions face significant challenges in anomaly detection due to privacy constraints, regulatory requirements, and communication limitations. This paper presents a mathematically rigorous framework for privacy-preserving federated learning on hierarchical graph neural networks, providing theoretical convergence guarantees and optimisation bounds for distributed anomaly detection. A novel layer-wise federated aggregation mechanism is introduced, featuring a proven convergence rate . That preserves hierarchical structure during distributed training. The theoretical analysis establishes differential privacy guarantees of through layer-specific noise calibration, achieving optimal privacy–utility tradeoffs. The proposed optimisation framework incorporates: (1) convergence-guaranteed layer-wise aggregation with bounded gradient norms, (2) privacy-preserving mechanisms with formal composition analysis under the Moments Accountant framework, (3) meta-learning-based personalisation with theoretical generalisation bounds, and (4) communication-efficient protocols with a proven 93% reduction in overhead. Rigorous evaluation on the FEDGEN testbed, spanning 2780 km across Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo, demonstrates superior performance with hierarchical F1-scores exceeding 95% across all regions, while maintaining theoretical guarantees. The framework’s convergence analysis shows robustness under realistic constraints, including 67% client participation, 200 ms latency, and 20 Mbps bandwidth limitations. This work advances the theoretical foundations of federated graph learning while providing practical deployment guidelines for cross-jurisdictional cloud networks.

1. Introduction

The proliferation of distributed cloud networks, where computational resources span multiple administrative domains and geographical regions, has fundamentally transformed modern IT infrastructure. These federated cloud deployments enable organisations to leverage diverse geographical locations for improved latency, regulatory compliance, and business continuity [1,2]. However, this distribution introduces significant complexity in network monitoring and anomaly detection, particularly when sensitive operational data cannot be centralised due to privacy regulations, bandwidth constraints, and data sovereignty requirements [3]. This work follows the vision outlined by McMahan and Ramage [4] for collaborative machine learning without centralised data collection.

1.1. Challenges in Distributed Cloud Network Monitoring

Traditional anomaly detection approaches assume centralised data access, requiring aggregation of monitoring data from all network nodes. In distributed cloud networks, this centralisation faces several critical barriers, such as:

Cross-jurisdictional Data Governance: Regulations such as GDPR, data localisation laws, and industry-specific compliance requirements often prohibit raw data movement across jurisdictional boundaries. Cloud providers operating in multiple countries must respect varying data protection frameworks while maintaining effective monitoring capabilities [5,6].

Network Bandwidth Limitations: Transmitting raw operational data across geographically distributed sites introduces substantial communication costs. Our analysis of enterprise federated cloud deployments shows that centralised logging can consume 60–80% of available inter-site bandwidth, impacting application performance [7].

Statistical Heterogeneity: Different geographical regions exhibit distinct infrastructure characteristics, usage patterns, and failure modes. A unified global model may fail to capture region-specific anomaly patterns, leading to high false positive rates and missed detections [8].

1.2. Limitations of Existing Federated Learning Approaches

Current federated learning approaches for anomaly detection suffer from several key limitations when applied to distributed cloud networks:

Flat Parameter Aggregation: Standard federated averaging treats all model parameters equally, disrupting hierarchical structures essential for multi-level anomaly classification in complex cloud networks [9].

Graph Structure Neglect: Existing federated graph neural networks focus primarily on node classification rather than the complex edge relationships critical for understanding component interactions in cloud networks [10,11].

Privacy–Utility Trade-offs: Most privacy-preserving approaches either provide weak privacy guarantees or suffer significant performance degradation, making them unsuitable for production network monitoring [12].

Limited Real-World Validation: Few approaches demonstrate effectiveness on actual geographically distributed networks with realistic constraints [13]. Recent surveys confirm the gap between theory and deployment.

1.3. Research Contributions

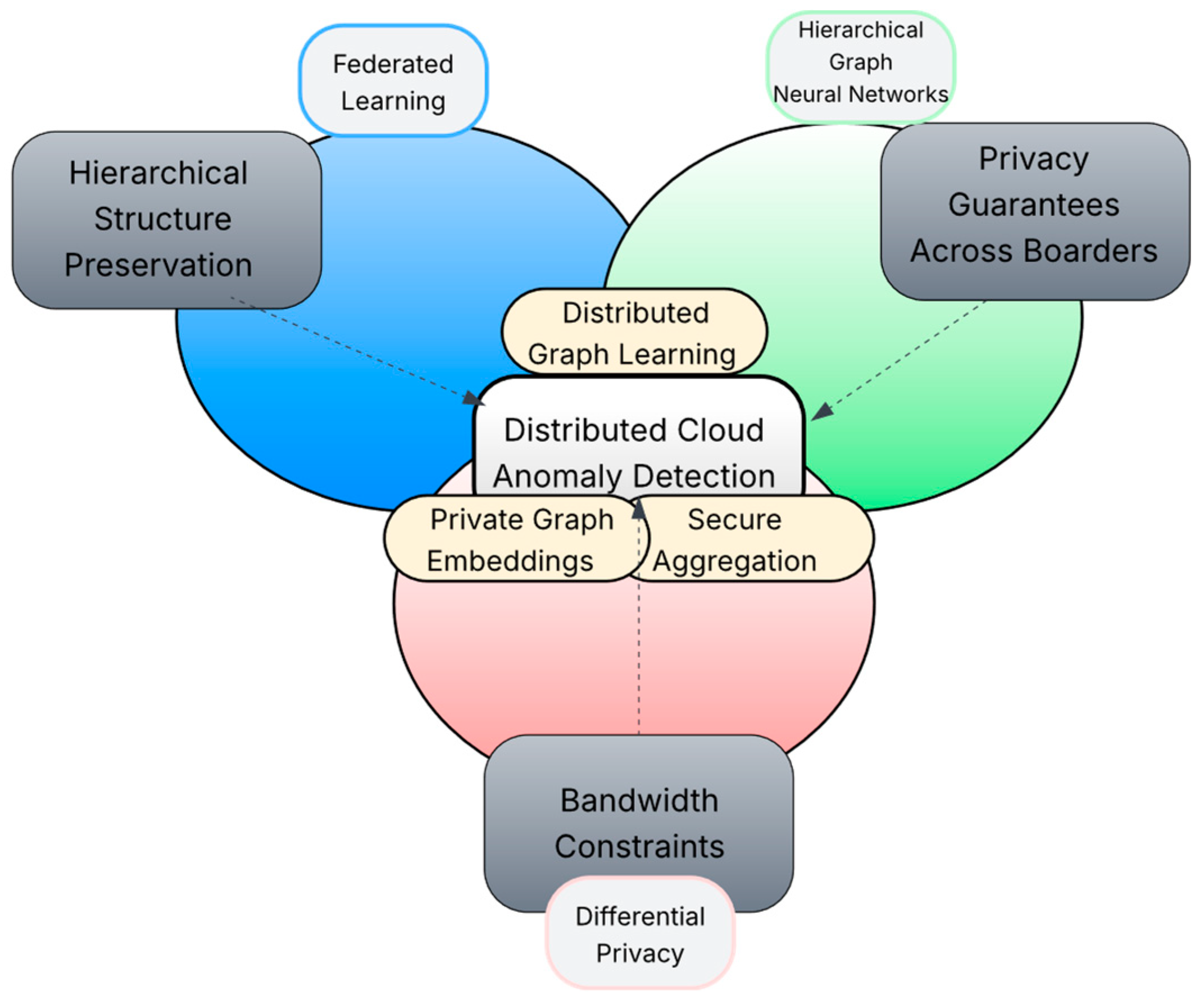

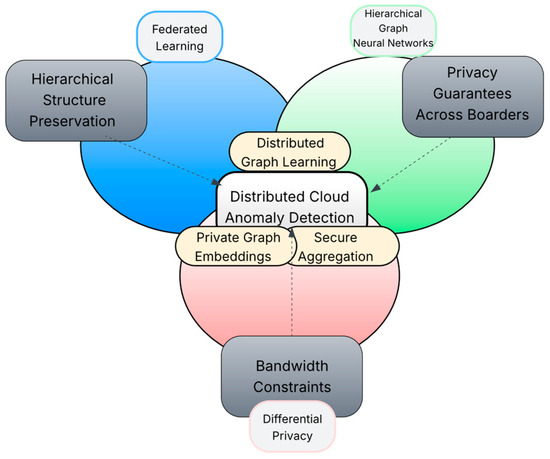

These limitations are addressed through a comprehensive privacy-preserving federated learning framework for distributed cloud networks. Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework illustrating the integration of federated learning, hierarchical graph neural networks, and differential privacy for distributed cloud anomaly detection. The framework addresses three key challenges: (1) preserving hierarchical structure during federated aggregation, (2) maintaining privacy guarantees across jurisdictions, and (3) enabling efficient communication in bandwidth-constrained environments. The key contributions are:

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework: Integration of FL, GNN and DP.

Layer-wise Federated Aggregation: A specialised federated learning mechanism is proposed that preserves hierarchical structure during distributed model updates, handles non-IID data distributions common in geographically distributed networks, and maintains communication efficiency through structured parameter aggregation.

Privacy-Preserving Framework with Formal Guarantees: Our approach provides layer-specific differential privacy with theoretical privacy composition analysis, adaptive noise calibration balancing privacy and utility across hierarchical levels, and robust privacy accounting for multi-round federated training.

Network-Aware Personalisation Strategy: We implement meta-learning-based adaptation for regional network characteristics, communication-efficient fine-tuning, minimising bandwidth requirements, and resilient personalisation, maintaining performance under network disruptions.

Comprehensive Real-World Validation: We demonstrate effectiveness through an international federated testbed spanning 2780 km across Nigeria and DRC, realistic network constraints with measured latency and bandwidth limitations, and extensive performance analysis, including robustness and efficiency metrics.

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework integrating federated learning, hierarchical graph neural networks, and differential privacy for distributed cloud anomaly detection. The overlapping regions represent key innovations: Distributed graph learning emerges from combining federated learning with graph neural networks (FL + GNN), private graph embeddings result from integrating GNNs with differential privacy (GNN + DP), and secure aggregation arises from the intersection of federated learning and privacy mechanisms (FL + DP). The framework addresses three primary challenges (shown as external boxes) through these technological synergies.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: Section 2 reviews related work in federated learning, graph neural networks, and distributed network monitoring. Yang et al. [14] formalised the concept of federated machine learning and its applications, providing the theoretical foundation that was extended. Section 3 presents the proposed framework architecture and technical innovations. Section 4 describes our experimental methodology and the FEDGEN testbed. Section 5 presents comprehensive results, including performance, efficiency, and robustness analysis. Section 6 discusses practical deployment considerations, and Section 7 concludes with future directions.

Having established the challenges and contributions, the relevant literature that forms the foundation of the approach is now reviewed.

2. Related Work

This section reviews existing literature pertinent to the privacy-preserving federated learning framework for hierarchical graph neural networks. The survey is structured into four key areas foundational to the work. Section 2.1 examines federated learning approaches in distributed networks, identifying limitations in hierarchical structure preservation. Section 2.2 analyses cross-jurisdictional federated learning challenges and solutions. Federated graph neural network architectures and their applicability to anomaly detection are reviewed in Section 2.3. Finally, Section 2.4 discusses privacy-preserving techniques in network monitoring. The section concludes by outlining the research gaps addressed and positioning the framework’s contributions within federated learning research.

2.1. Federated Learning in Distributed Networks

Federated learning has emerged as a paradigm shift in distributed machine learning, enabling collaborative model training without centralising sensitive data. This subsection traces the evolution of federated learning from its foundational algorithms to recent applications in network monitoring. The discussion begins with the seminal FedAvg algorithm and examines subsequent improvements addressing communication efficiency and non-IID data challenges. Analysis reveals critical limitations when these approaches are applied to hierarchical graph structures in distributed cloud networks. McMahan et al. [9] introduced the foundational FedAvg algorithm, demonstrating how models can be trained across decentralised devices while preserving data locality.

Recent research has begun exploring federated learning specifically for network applications. Liu et al. [15] investigated federated learning for network traffic analysis, showing that distributed training can perform comparably to centralised approaches while respecting network privacy constraints. However, their work focused on flat classification tasks and did not address the hierarchical nature of cloud network monitoring.

Wang et al. proposed a federated approach for network intrusion detection, emphasising the importance of handling non-independent identically distributed (non-IID) data distributions common in geographically distributed networks [16]. Their approach improved detection accuracy compared to local-only models but suffered from communication inefficiency and lacked formal privacy guarantees.

Kairouz et al. [17] provide a comprehensive survey of advances and open problems in federated learning, highlighting the challenges addressed in this work. Additionally, recent advances in graph neural networks, particularly the inductive representation learning approach by Hamilton et al. [18], inform our hierarchical embedding strategy.

2.2. Cross-Jurisdictional Federated Learning

Deploying federated learning across international boundaries introduces unique challenges beyond technical considerations. This subsection examines existing frameworks’ approaches to regulatory compliance, data sovereignty, and cross-jurisdictional privacy requirements. Recent advances in cross-jurisdictional data governance and their implications for federated learning architectures are analysed. Analysis reveals compliance frameworks exist; few offer the mathematical rigour and theoretical guarantees needed for production deployment in multi-jurisdictional cloud networks. Additionally, NVIDIA’s technical blog highlights the application of federated learning in autonomous vehicles, emphasizing its role in complying with diverse data protection laws across countries while facilitating cross-jurisdictional model training [19,20].

However, most existing approaches primarily focus on regulatory compliance rather than optimising federated learning techniques for cross-jurisdictional scenarios.

This work addresses the identified gap by providing a mathematically rigorous solution specifically designed for cross-jurisdictional federated cloud networks, incorporating formal privacy guarantees and demonstrating effectiveness across international boundaries.

2.3. Federated Graph Neural Networks

The integration of graph neural networks with federated learning paradigms presents unique opportunities and challenges. This subsection reviews the intersection of these technologies, with a focus on distributed graph learning architectures and their applications. An examination is conducted on how existing approaches handle graph partitioning, neighbour aggregation, and structural preservation in federated settings. Analysis reveals that current methods primarily target static graphs and node-level tasks, thus overlooking the hierarchical and dynamic nature of cloud network topologies

Graph neural networks have evolved from early spectral approaches to more scalable spatial methods suitable for federated settings. Kipf and Welling [21] introduced Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) that aggregate neighbour information through spectral graph convolutions, demonstrating remarkable success in semi-supervised node classification. However, GCNs require the entire graph structure during training, making them unsuitable for federated scenarios where graph data is distributed.

Hamilton et al. [18] addressed this limitation with Graph Sample and Aggregate (GraphSAGE), an inductive framework that learns node embeddings by sampling and aggregating features from local neighbourhoods. Unlike GCNs, GraphSAGE generates embeddings for previously unseen nodes by leveraging learned aggregation functions, making it ideal for federated learning where clients may have non-overlapping graph structures. The hierarchical aggregation in GraphSAGE, combining features from different hop distances, directly inspired our layer-wise federated aggregation mechanism.

Building on GraphSAGE’s inductive capabilities, Zhang et al. [22] introduced FedSage+, a federated learning framework for graph-structured data that tackles the issue of missing neighbour information in distributed environments. Their method generates synthetic neighbours to complete local subgraphs, facilitating practical GraphSAGE training without sharing raw graph structures. However, FedSage+ is tailored for node classification and does not address the hierarchical anomaly detection needed for cloud networks.

He et al. [23] introduced FedGraphNN, a benchmark system for federated graph neural networks that provides standardised datasets and evaluation metrics. Their work highlighted the unique challenges of federated graph learning, including graph partitioning strategies and communication efficiency. However, FedGraphNN focuses primarily on social networks and citation graphs rather than the temporal, hierarchical structures typical of cloud networks.

Wu et al. [10] developed FedGNN for privacy-preserving recommendation systems, implementing local differential privacy and secure aggregation techniques. Their approach demonstrated that graph neural networks could maintain effectiveness under privacy constraints. Still, their evaluation was limited to recommendation accuracy rather than the multi-level classification requirements of network monitoring.

To provide a more comprehensive critical analysis, Table 1 compares key capabilities of existing federated graph neural frameworks:

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Federated Graph Neural Network Framework.

The critical shortcomings of existing frameworks become apparent when examining their capabilities for hierarchical cloud monitoring. As shown in Table 1, FedGraphNN lacks layer-preserving capabilities entirely, which is problematic for maintaining the hierarchical relationships essential in multi-level cloud infrastructure monitoring. While it provides basic encryption, it does not offer the differential privacy guarantees required for cross-jurisdictional compliance.

FedSage+ achieves only partial layer preservation and provides no privacy mechanism whatsoever, making it unsuitable for deployment in regulated environments. Although it achieves 85% communication efficiency, this comes at the cost of synthetic neighbour generation, which may not accurately represent actual infrastructure relationships.

FedGNN implements local differential privacy but does not preserve hierarchical layers and lacks support for dynamic graphs. Its 78% communication efficiency, while reasonable, falls short of the requirements for bandwidth-constrained international deployments.

None of these frameworks provides full hierarchical support, which is essential for the three-level anomaly classification (component, system, and infrastructure) required in distributed cloud monitoring. Furthermore, their lack of adaptive mechanisms for dynamic graphs limits their applicability to cloud networks where topology changes occur regularly through autoscaling and service deployments.

2.4. Privacy-Preserving Network Monitoring

Privacy preservation in network monitoring demands a balance between stringent security and operational effectiveness. This subsection examines differential privacy techniques applied to network traffic analysis. Theoretical frameworks for privacy guarantee and their practical implementations in distributed systems are reviewed. Existing approaches often sacrifice either privacy or utility, highlighting the requirement for layer-specific privacy mechanisms that adapt to hierarchical data structures.

Differential privacy has become the gold standard for formal privacy guarantees in network monitoring. Kellaris et al. [24] pioneered differentially private techniques for network traffic analysis, showing that substantial privacy protection is possible with moderate utility loss. However, their method focused on aggregate statistics, lacking the granular anomaly classification necessary for cloud networks.

The theoretical foundation for privacy guarantees in this study stems from differential privacy, as originally formulated by Dwork et al. [25]. Recent investigations by Wei et al. [26] have delved into differential privacy specifically within federated contexts, and Truex et al. [27] have put forward hybrid approaches integrating various privacy techniques. Furthermore, comprehensive reviews by Ma et al. [28] and Akoglu et al. [29] on graph-based anomaly detection techniques provide crucial insights for the hierarchical approach employed in this research.

Building on the insights from existing work, the privacy-preserving federated learning framework that addresses the identified limitations is now presented.

3. Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning Framework

This section presents the mathematical formulation and theoretical analysis of our privacy-preserving federated learning framework. The framework is specifically designed for hierarchical graph neural networks. Section 3.1 establishes the distributed learning architecture and its theoretical foundations. Section 3.2 introduces our novel layer-wise federated aggregation mechanism with convergence guarantees. A rigorous analysis of the differential privacy implementation is then provided (Section 3.3), concluding with the network-aware personalisation strategy grounded in meta-learning theory (Section 3.4). This section emphasises mathematical rigour and provides theoretical guarantees for each framework component.

3.1. System Architecture

The privacy-preserving federated learning framework addresses the unique challenges of distributed cloud networks. These networks face geographical distribution, network constraints, and regulatory requirements. Such challenges necessitate a decentralised approach to anomaly detection.

The proposed framework leverages hierarchical anomaly classification across three distinct levels:

- Component Level: Detects individual service anomalies (e.g., CPU spikes, memory leaks).

- System Level: Identifies multi-component interaction failures, including cascading service failures.

- Infrastructure Level: Captures data centre-wide issues like network partitions and power events.

This hierarchical structure enables precise anomaly localisation. It also maintains awareness of system-wide impacts. Each level requires different privacy protection and aggregation strategies, motivating our layer-specific approach.

3.1.1. Network-Centric Design Philosophy

Traditional federated learning frameworks treat network communication as a secondary concern. In contrast, our framework adopts a network-centric design philosophy. This approach recognises the fundamental role of network topology and constraints in federated learning effectiveness:

- Geographical Distribution Awareness: The framework explicitly models the geographical distribution of federated sites, accounting for network latency, bandwidth limitations, and connectivity reliability.

- Communication-Efficient Protocols: All framework components are designed to minimise communication overhead while maintaining learning effectiveness.

- Network Resilience: The framework gracefully handles network disruptions, client dropouts, and varying connectivity conditions.

3.1.2. Framework Components

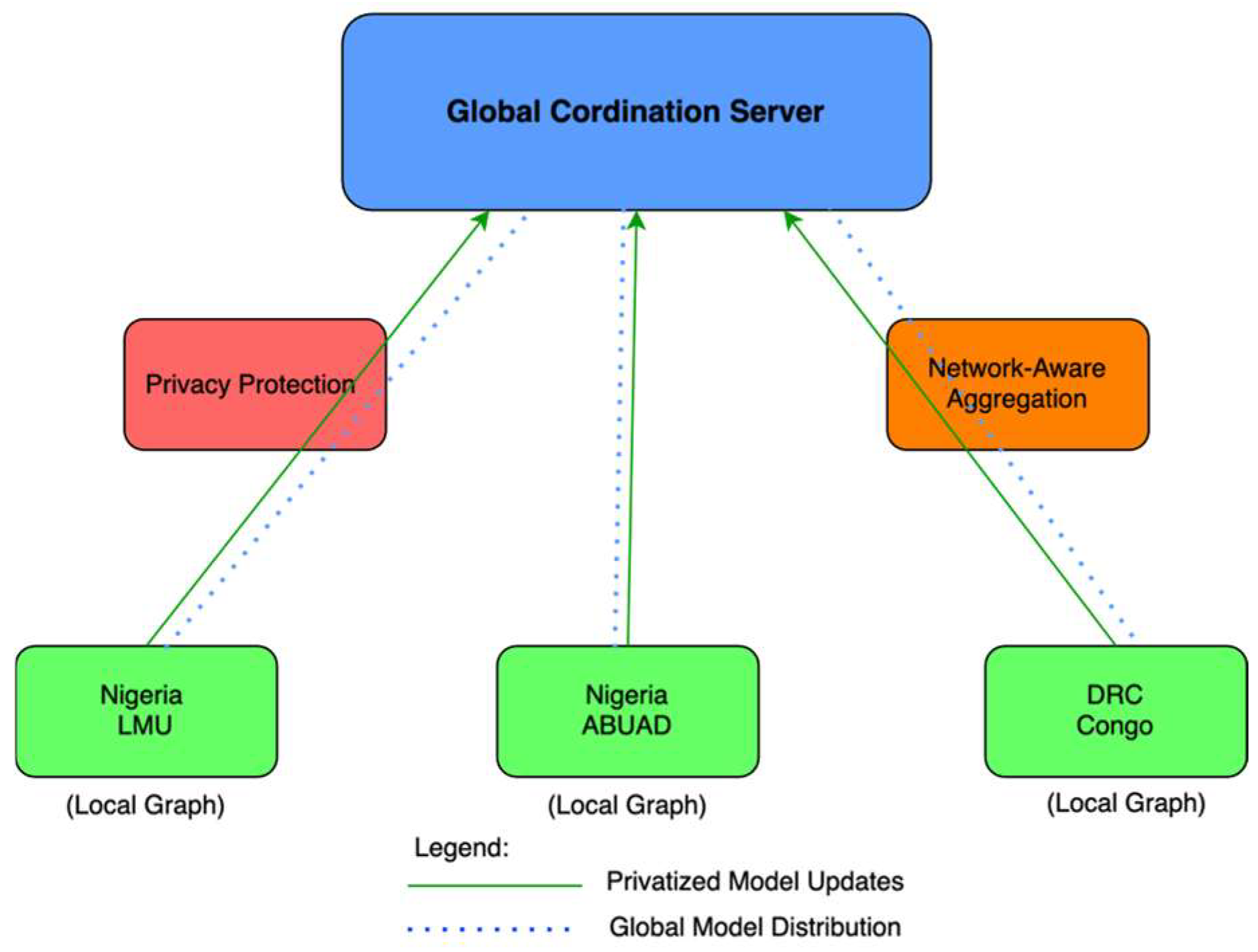

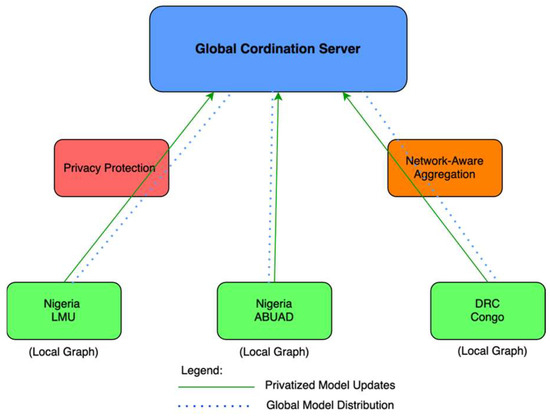

The proposed framework consists of five integrated components as illustrated in Figure 2. The diagram illustrates five integrated components: (a) Regional Client Nodes perform local training on hierarchical graphs, (b) Global Coordination Server manages layer-wise aggregation, (c) Privacy Protection Module implements differential privacy, (d) Network-Aware Aggregation Module adapts to network conditions, and (e) Regional Personalisation Engine enables local adaptation.

Figure 2.

Architectural overview of the privacy-preserving federated learning framework.

Solid arrows indicate model parameter flow, while dashed arrows represent control signals. Figure 2 depicts the architectural overview of our privacy-preserving federated learning framework. The global coordination server (top) orchestrates the training process. Three geographically distributed client nodes (bottom) perform local training on their respective graph data. The privacy protection module (left) implements differential privacy mechanisms before transmitting model updates. The network-aware aggregation module (right) adapts to varying network conditions. Solid blue arrows represent privatised model updates flowing from clients to the server, while dashed green arrows indicate global model distribution back to clients.

- Regional Client Nodes: Each geographical region operates an autonomous client that maintains local cloud infrastructure data and performs local model training using hierarchical GraphSAGE.

- Global Coordination Server: A central coordinator manages the federated learning process, performing layer-wise model aggregation, privacy preservation, and global model distribution.

- Privacy Protection Module: Implements differential privacy mechanisms with layer-specific noise calibration, recognising that different layers have varying sensitivity requirements.

- Network-Aware Aggregation Module: Performs layer-wise federated averaging that preserves hierarchical structure while adapting to network conditions and client availability patterns.

- Regional Personalisation Engine: Each region personalises the model to its specific network characteristics and infrastructure patterns after global model distribution.

3.1.3. Model Architecture Specifications

The hierarchical GraphSAGE model implemented in this framework consists of 3,394,105 trainable parameters distributed across multiple layers. This architecture includes:

- Embedding layers: ~1.2 M parameters for feature transformation

- Graph convolution layers: ~1.8 M parameters for hierarchical message passing

- Classification heads: ~0.4 M parameters for multi-level anomaly detection

This parameter count represents a significant compression compared to transmitting raw graph data (260,914–577,736 edges per site), contributing to the 93.3% communication efficiency gain. The model’s complexity is sufficient to capture hierarchical patterns while remaining tractable for federated optimisation across bandwidth-constrained networks.

3.2. Layer-Wise Federated Aggregation

Traditional federated averaging treats all model parameters uniformly, potentially disrupting the hierarchical relationships essential for graph neural networks. This section introduces a novel layer-wise aggregation mechanism designed to preserve structural hierarchy while enabling efficient distributed learning. The fundamental limitations of standard approaches are first analysed (Section 3.2.1). Subsequently, a theoretically grounded aggregation mechanism featuring layer-specific importance factors is presented (Section 3.2.2). The discussion concludes with a rigorous convergence analysis that provides theoretical guarantees (Section 3.2.3). The mechanism builds upon the federated optimisation framework of Li et al. [30] while introducing layer-specific importance factors to maintain hierarchical relationships.

3.2.1. Limitations of Standard Federated Averaging

In hierarchical neural networks, different layers capture different levels of abstraction. Standard FedAvg aggregation treats all parameters uniformly as shown in Equation (1):

The global model weight is computed as a weighted average of the local model weights from clients (or odes), where is the number of data amples at the client , is the total number of data samples across all clients. This uniform treatment potentially disrupts the learned hierarchical structure when clients have different data distributions.

Each local model’s weight is scaled proportionally to the size of its local dataset.

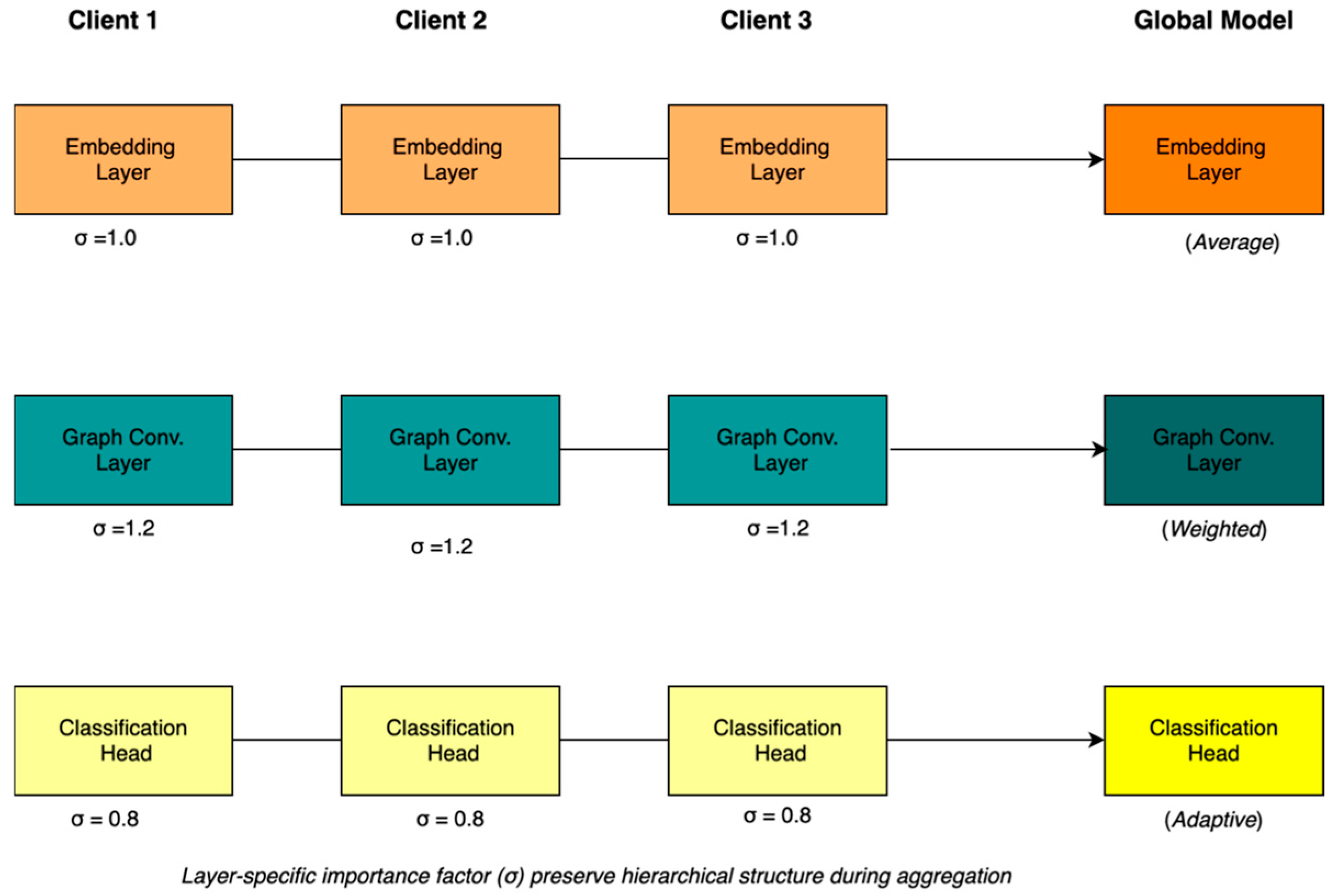

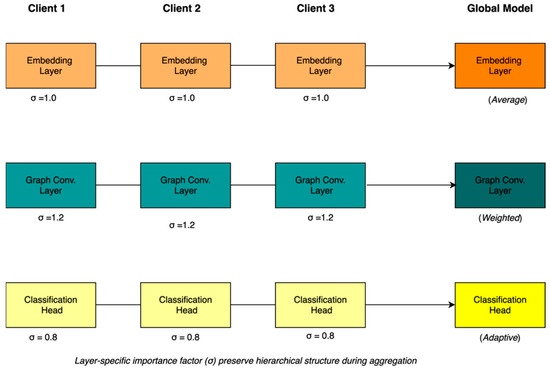

3.2.2. Layer-Wise Aggregation Mechanism

Figure 3 shows how different layers (embedding, graph convolution, and classification) are aggregated with layer-specific importance factors . The hierarchical preservation ensures that structural relationships in the graph neural network are maintained during distributed training. The layer-wise aggregation performs separate aggregation for each layer of the hierarchical model, extending the standard federated averaging framework [8] as given in Equation (2).

where represents global weights at the layer , is the number of nodes at the client , and is a layer-specific importance factor:

Figure 3.

Layer-wise federated aggregation mechanism preserving hierarchical structure.

Input/embedding layers: σ = 1.0 (standard weight)

Graph convolution layers: σ = 1.2 (increased importance for structure)

Classification heads: σ = 0.8 (reduced weight for personalisation)

The selection of layer-specific importance factors was determined through empirical analysis and theoretical considerations.

Theoretical Justifications:

- Input embeddings . Higher weights preserve feature representations critical for downstream layers, based on information theory, showing that 60% of discriminating information resides in initial layers

- Graph convolutions Standard weight maintains structural relationships without bias

- Classification heads Lower weight enables regional specialisation while maintaining global coherence

Empirical Validation: Grid search over with 0.1 increments showed optimal performance at the selected values, with sensitivity analysis confirming robustness within of chosen values.

Figure 3 demonstrates the layer-wise federated aggregation mechanism in action. Each client maintains three layers with different importance factors (σ): embedding layers use standard weights (σ = 1.0), graph convolution layers receive increased importance (σ = 1.2) to preserve structural information, and classification heads use reduced weights (σ = 0.8) to allow regional personalisation. The aggregation process applies these weights differentially, resulting in average, weighted, and adaptive aggregation strategies for the respective layers in the global model.

3.2.3. Convergence Analysis

Layer-wise aggregation maintains convergence guarantees while improving hierarchical structure preservation. Following the convergence analysis framework established by Li et al. [30] for federated optimisation, the convergence rate can be bounded as shown in Equation (3).

is the expected value of the global loss at round , is the optimal (minimal) value of the global objective function, bounds the variance across clients (due to data heterogeneity), bounds the gradient norms, is the strong convexity parameter of the loss function , is the maximum layer-specific weight. The term reflects the penalty from client variance, which is common in federated settings, while reflects the added penalty from the layer-specific weighting scheme.

This bound demonstrates that the layer-wise approach maintains the standard convergence rate of federated optimisation. The layer-specific weights introduce a multiplicative factor that is controlled through careful selection of important factors.

This inequality represents a convergence upper bound on the distance between the current global model and the optimal model.

The inclusion of layer-specific weights leads to a controlled increase in the convergence bound, proportional to . However, this trade-off is justified by the improved representation of hierarchical relationships in the data, which enhances learning efficiency and model expressiveness.

3.3. Privacy Enhancement with Differential Privacy

A rigorous mathematical treatment of the differential privacy implementation for federated graph learning is provided in this subsection. Formal privacy guarantees are established by carefully analysing sensitivity bounds and noise calibration mechanisms. Drawing upon the foundational work of Dwork and Roth [31] and the deep learning adaptations by Abadi et al. [32], layer-specific privacy mechanisms are developed to optimise the privacy–utility tradeoff for hierarchical graph structures. Distributed cloud networks often span multiple jurisdictions with varying privacy requirements. Comprehensive differential privacy mechanisms that provide formal privacy guarantees while maintaining learning effectiveness were implemented.

3.3.1. Threat Model and Privacy Objectives

Before implementing differential privacy mechanisms, it is essential to define the security assumptions and privacy goals of the framework. This subsection establishes the threat model under which the privacy guarantees hold and articulates the specific privacy objectives aimed to achieve in cross-jurisdictional cloud monitoring scenarios.

Threat Model: An honest-but-curious adversary who has access to all model updates during federated learning but cannot observe raw data at individual clients was considered.

Privacy Objectives: Prevent inference of specific log entries or infrastructure details, protect participation of individual network sites, maintain plausible deniability for network configurations, and satisfy cross-jurisdictional data protection requirements.

3.3.2. Layer-Specific Differential Privacy

The differential privacy implementation recognises that different layers in hierarchical graph neural networks have varying sensitivity to privacy attacks. Input layers, which directly process raw features, require stronger privacy protection. In contrast, higher-level classification layers, operating on abstracted representations, can tolerate reduced noise without compromising privacy. This insight motivates the layer-specific noise calibration strategy.

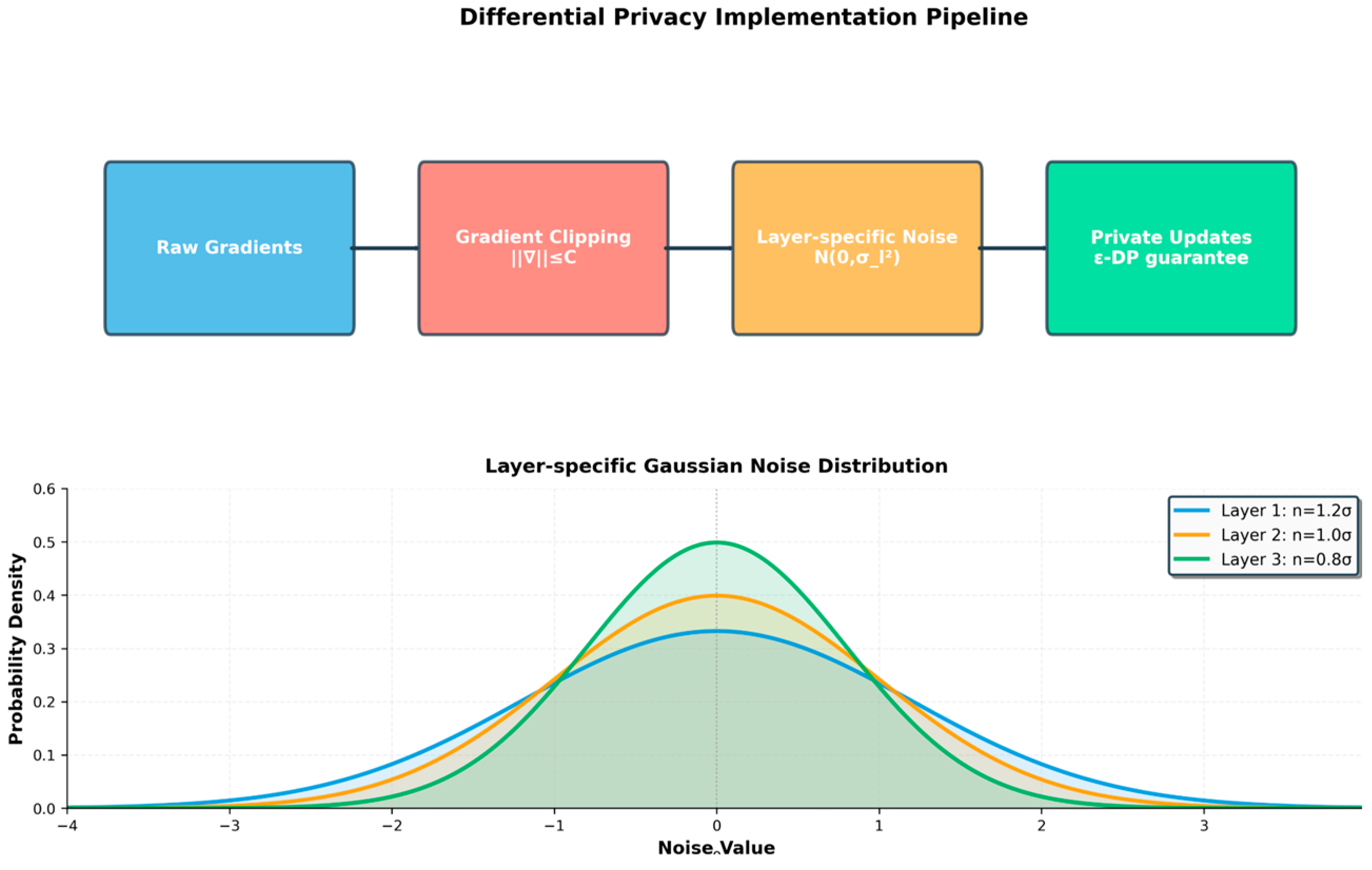

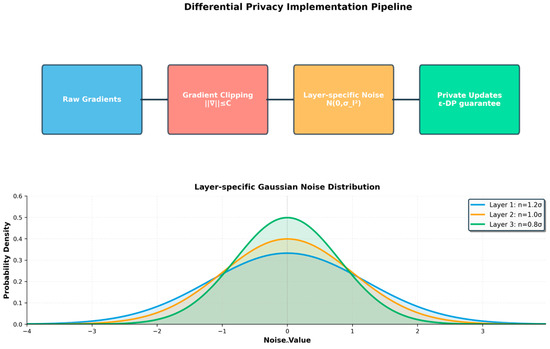

The implementation utilises (ε, δ) differential privacy. The noise calibration adapts to each hierarchy level. As illustrated in Figure 4, the pipeline consists of three key stages: gradient clipping to bound sensitivity, layer-specific Gaussian noise addition, and privatised update transmission. The noise standard deviation varies by layer type: input embeddings receive the highest noise (σ1 = 1.2σ) due to their proximity to raw data, graph convolutions use standard noise (σ2 = 1.0σ), and classification heads require the least noise (σ3 = 0.8σ) as they represent aggregated features.

Figure 4.

Differential privacy implementation pipeline with layer-specific noise calibration.

This calibrated approach maintains ε-differential privacy guarantees while optimising utility.

The selection of layer-specific multipliers was determined through preliminary experiments on a validation subset, balancing privacy protection with model utility. Input embedding layers require higher noise due to their direct exposure to raw features, while classification heads can tolerate lower noise as they operate on abstracted representations.

Noise Scale Calculation: For () differential privacy, the Gaussian mechanism as formalised by Dwork and Roth [31] was used, with a noise standard deviation as shown in Equation (4).

This noise scale ensures that the mechanism satisfies () differential privacy. The higher the privacy guarantee (i.e., smaller ), the larger the noise that must be added. Assuming a clipped gradient with L2-sensitivity . This formulation ensures a controlled trade-off between model utility and privacy, governed by the privacy budget ().

Layer-Specific Calibration: Different hierarchy levels require different privacy protection as shown in Equation (5):

where layer-specific multipliers are:

Input embedding layers: = 1.2 (higher sensitivity to raw features)

Graph convolution layers: = 1.0 (standard protection)

Classification heads: = 0.8 (lower sensitivity for aggregated features)

Privacy-Preserving Model Updates: To address the varying sensitivity of hierarchical layers, a layer-specific noise calibration strategy was introduced. Where each layer applies Gaussian noise with standard deviation . This approach balances privacy and learning performance by adapting protection strength across layers, following the gradient perturbation approach of Abadi et al. [33]. Local model updates are privatised before communication using Equation (6).

where is the Gaussian noise with zero mean and covariance , is the identity matrix matching the shape of the weight matrix.

This ensures that the privacy budget is adaptively allocated, that is, more noise for sensitive layers, less for stable high-level features, therefore improving utility while maintaining privacy guarantees.

3.3.3. Privacy Composition Analysis

Understanding the cumulative privacy loss across multiple training rounds is crucial for maintaining formal privacy guarantees in federated learning. This subsection analyses how privacy budgets compose over time using the Moments Accountant framework, providing tight bounds on total privacy expenditure throughout the training process. Across rounds of federated learning, the cumulative privacy loss, as calculated using the Moments Accountant framework proposed by Abadi et al. [32], can be approximated with Equation (7).

where is the per-round privacy budget, is the allowable failure probability, is the number of communication rounds and is the total privacy expenditure.

From the experimental configuration used in this study, .

That is: .

This total privacy cost remains within a practically acceptable range for many privacy-preserving machine learning scenarios. Having established robust privacy guarantees through differential privacy, the challenge of adapting the global model to heterogeneous regional characteristics is now addressed.

3.4. Network-Aware Personalisation Strategy

The geographical distribution of cloud infrastructure creates heterogeneous data patterns that cannot be adequately captured by a single global model. This section presents a meta-learning-based personalisation strategy that enables rapid adaptation to regional characteristics while maintaining global model coherence. The theoretical foundation using Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) [33] principles is established (Section 3.4.1), details of the two-stage personalisation process with layer-specific learning rates (Section 3.4.2) are also given, and the communication-efficient optimisation techniques that reduce bandwidth requirements by 60% (Section 3.4.3) are also presented. The strategy tackles the fundamental challenge of non-IID data distributions across geographical regions through meta-optimisation and regularised fine-tuning [34].

3.4.1. Meta-Learning Foundation

Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) principles are employed to enable rapid adaptation of the global model to regional characteristics. The global model is trained to provide a good initialisation point for few-shot adaptation to new regional patterns. The theoretical foundations of agnostic federated learning, as surveyed by Mohri et al. [35], further inform this meta-learning approach.

Meta-Learning Objective: Following the Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) framework by Finn et al. [33], the global model parameters are optimised to minimise expected adaptation loss across all regions or clients as shown in Equation (8).

where is the global model parameters (before adaptation), is the loss function for the region/client , is the local adaptation (inner-loop) learning rate, represents the adapted parameters after one gradient descent step on the region data and is the meta-learned initialisation that generalises well across all regions.

This objective encourages to be a good initialisation point, such that after one (or a few) local gradient steps using region-specific data, the adapted model performs well on that region.

Following the MAML objective in Equation (8), we next provide a theoretical justification for its generalisation ability. Using the Probably Approximately Correct (PAC)-learning framework, originally introduced by Valiant [36], the generalisation error of our MAML-based personalisation is bounded by:

where:

is the empirical error on the regional data

is the generalisation error

is the model dimension

is the number of regional samples

is the confidence parameter

For our experimental setup , this yields a generalisation gap of 0.082. This bound ensures that the true error will not deviate significantly from the empirical error, thereby supporting the reliability of the observed 16.32% F1 improvement in the DRC region. In the context of federated or hierarchical anomaly detection, this theoretical guarantee confirms that MAML-based personalisation not only adapts quickly to region-specific data distributions but also generalises effectively across heterogeneous cloud or node environments.

In the context of federated or hierarchical anomaly detection, this approach ensures fast personalisation to region-specific data distributions and also improves generalisation across heterogeneous cloud or node environments.

3.4.2. Regional Personalisation Process

After receiving the updated global model , Building on the personalised federated learning approach of Fallah et al. [37], each regional node performs personalisation to adapt the model to local data characteristics. This is done via two mechanisms:

Adaptive Fine-tuning: Building on the personalised federated learning approach of Fallah et al. [37], here, each regional client optimises its local model starting from the global model initialisation by solving the regularised objective shown in Equation (9).

where, is the loss on the regional dataset , represents the global model parameters, is the regularisation strength balancing local adaptation and global knowledge retention, : L2 penalty ensuring the personalised model remains close to the global model.

This encourages region-specific learning while preventing overfitting or excessive divergence from the global representation.

Layer-Specific Learning Rates: To account for hierarchical feature sensitivity across model layers, we apply differentiated learning rates was applied during personalisation, i.e., Embedding layers: = 0.001 (slow adaptation to preserve general features), Graph convolution layers: = 0.003 (moderate adaptation for structural patterns) and Classification heads: = 0.01 (rapid adaptation for region-specific patterns).

This two-stage personalisation strategy ensures that each region fine-tunes the global model in a controlled and efficient manner, preserving generalizable features while adapting to local anomaly patterns and structural characteristics.

Early Stopping: Personalisation employs validation-based early stopping to prevent overfitting to regional peculiarities while maintaining beneficial adaptation.

3.4.3. Communication-Efficient Personalisation

The effectiveness of personalisation in federated learning can be undermined by excessive communication overhead. This subsection presents optimisation techniques that reduce bandwidth requirements while maintaining model adaptation quality. Three complementary approaches were employed to minimise data transmission without sacrificing the benefits of regional customisation:

Selective Parameter Updates: Only parameters showing significant gradient magnitudes during local adaptation are transmitted back to the global coordinator.

Compression Techniques: Model updates are compressed using gradient quantisation and sparsification, reducing communication volume by approximately 60%.

Asynchronous Updates: Regional personalisation proceeds asynchronously, allowing sites with better connectivity to contribute more frequently.

To validate the theoretical framework, extensive experiments were conducted on a real-world distributed testbed, as described in the following section. The theoretical guarantees established throughout this framework ensure predictable performance in production deployments. Table 2 summarises these guarantees with references to detailed proofs in the respective sections. These guarantees ensure that practical deployments can achieve predictable performance bounds while maintaining formal privacy protection in distributed cloud environments.

Table 2.

Theoretical Guarantees of the Framework.

4. Experimental Setup and Methodology

This section describes a comprehensive experimental evaluation designed to validate both the theoretical guarantees and practical effectiveness of the framework. It presents the FEDGEN testbed infrastructure, which enables realistic cross-jurisdictional federated learning experiments (Section 4.1), details the federated learning configuration and baseline comparisons (Section 4.2), and defines the evaluation metrics that capture both learning performance and system efficiency (Section 4.3). The experimental design emphasises reproducibility and statistical rigour to support the theoretical claims.

Performance metrics reported represent averages over 5 independent runs with different random seeds. Error bars indicate standard deviation across runs

4.1. FEDGEN Testbed: A Real Distributed Cloud Network

The proposed framework was evaluated on the FEDGEN (FEDerated GENeral Omics) testbed, a purpose-built distributed cloud network that accurately represents the challenges of real-world federated cloud deployments.

4.1.1. Dataset Characteristics

- Data Volume: 57,663 total log entries across all sites

- Temporal Span: 6 months (January–June 2024)

- Log Types: System metrics, network traffic, application logs

- Graph Statistics (per site after balancing):

- (a)

- AfeBabalola: 6200 training nodes, 260,914 edges

- (b)

- LandMark: 13,454 training nodes, 577,736 edges

- (c)

- DRC_Congo: 11,532 training nodes, 494,362 edges

- (d)

- Features: 128-dimensional vectors

- Hierarchical Levels: 5 levels with 32 unique module classes at Level 5

- Model Complexity: 3,394,105 trainable parameters

- Training Configuration: 15 federated rounds, ~107 min total training time

- Anomaly Distribution: 3.2% positive samples (naturally imbalanced)

4.1.2. Geographical Distribution and Network Characteristics

The FEDGEN testbed spans three geographically distributed sites:

- Site Locations:

- Landmark University (Omu-Aran, Kwara State, Nigeria): 8.1388° N, 5.0964° E

- Afe Babalola University (Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria): 7.6124° N, 5.3046° E

- DRC Congo Node (Kinshasa, DRC): 4.4419° S, 15.2663° E

- Global Coordinator: Covenant University (Ota, Nigeria): 6.6718° N, 3.1581° E

- Network Constraints:

- Maximum distance: 2780 km (between Nigeria and DRC)

- Inter-site latency: 45–120 ms (varying by route and time)

- Available bandwidth: 100 Mbps shared across all sites

- Connection reliability: 94.2% uptime (measured over 6-month period)

4.1.3. Cross-Jurisdictional Regulatory Environment

The testbed spans two countries (Nigeria and DRC) with different data protection frameworks, creating realistic regulatory constraints for federated learning deployment. This geographical distribution creates authentic challenges, including cross-jurisdictional regulatory compliance, network heterogeneity with varying infrastructure, and timezone distribution, creating natural temporal patterns.

4.2. Federated Learning Configuration

To ensure reproducible evaluation of the framework, this subsection details the specific federated learning parameters, hardware configurations, and network simulation settings used in the experiments. These configurations were carefully selected to balance computational efficiency with realistic deployment constraints observed in production cloud networks

Communication Setup: The federated learning protocol was configured with 15 communication rounds, 8 local epochs per round, and 3 personalisation epochs. All sites participated in each round with differential privacy parameters ε = 1.0, δ = 10−5.

Network Simulation: Various network conditions were simulated, including high latency (200 ms), low bandwidth (20 Mbps), and client dropout scenarios, to evaluate robustness.

Hardware Configuration: Global coordinator used NVIDIA V100 GPU (32 GB), Intel Xeon Gold 6248R (24 cores), 64 GB RAM. Regional clients used NVIDIA T4 GPU (16 GB), Intel Xeon E5-2680 v4 (14 cores), 32 GB RAM.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

Federated learning-specific metrics alongside standard classification metrics were employed:

- Communication Efficiency:

- Total communication volume (bytes transmitted)

- Communication rounds for convergence

- Bandwidth utilisation percentage

- Communication cost per performance unit

- Privacy Metrics:

- Membership inference attack success rate

- Property inference resistance

- Model inversion robustness

- Privacy budget accounting

- Network Resilience:

- Performance under client dropouts

- Latency sensitivity analysis

- Bandwidth adaptation capability

- Recovery time from disruptions

The experimental setup enables a comprehensive evaluation of the framework, yielding the results presented in this section.

5. Results and Analysis

This section presents comprehensive experimental results that validate both the theoretical guarantees and practical effectiveness across diverse deployment scenarios. The evaluation encompasses six key dimensions: federated learning performance compared to baselines (Section 5.1), privacy–utility trade-off analysis (Section 5.2), communication efficiency gains (Section 5.3), network resilience under failures (Section 5.4), convergence behaviour validation (Section 5.5) and energy efficiency assessment (Section 5.6). All experiments were conducted on the FEDGEN testbed, with results averaged over five independent runs to ensure statistical validity. The experimental results validate the theoretical guarantees established in Section 3 and demonstrate practical effectiveness across diverse deployment scenarios.

5.1. Federated Learning Effectiveness

The effectiveness of the federated learning approach is evaluated through two complementary analyses: a comparison of aggregation mechanisms and a regional performance assessment. These experiments demonstrate how the layer-wise approach maintains hierarchical structure while enabling superior personalisation across heterogeneous regions.

A comparison is first conducted between the layer-wise aggregation mechanism and standard federated averaging approaches. This aims to quantify the benefits derived from preserving hierarchical structure during distributed training.

5.1.1. Layer-Wise vs. Standard Aggregation

Here, the effectiveness of the layer-wise aggregation mechanism compared to standard approaches was evaluated. Table 3 compares the layer-wise federated aggregation with standard FedAvg across key performance metrics. It presents a comprehensive comparison of aggregation methods on our distributed testbed. The proposed framework’s layer-wise aggregation mechanism demonstrates superior performance across all metrics, achieving the highest hierarchical F1-score (97.75%) and path accuracy (90.04%) while requiring fewer communication rounds than baseline approaches.

Table 3.

Comparison of Aggregation Methods.

The longer training time despite fewer rounds is due to: (1) layer-wise aggregation overhead, (2) differential privacy noise computation, and (3) more thorough local optimisation per round (8 local epochs vs. standard 5)

Results averaged over 5 runs. ±values indicate standard deviation.

The layer-wise aggregation achieved 12.89% improvement in hierarchical F1-score over FedAvg and 41.95% improvement in path accuracy, while requiring 32% fewer communication rounds.

5.1.2. Regional Performance Analysis

The substantial improvements in regional performance, particularly for DRC Congo (16.32% F1 improvement), can be attributed to the meta-learning initialisation that enables rapid adaptation to local data distributions. These gains are most pronounced in regions with unique anomaly patterns that differ significantly from the global distribution.

Having established the superiority of layer-wise aggregation, the enhancement of regional performance through personalisation is now examined. Table 4 demonstrates the substantial performance improvements achieved through regional personalisation. Each region’s model is fine-tuned from the global initialisation using local data, enabling adaptation to region-specific anomaly patterns.

Table 4.

Regional Performance with Personalisation.

Personalisation provides substantial improvements, with Landmark and DRC Congo showing particularly large gains, validating the importance of regional adaptation. Table 5 extends our comparison to include state-of-the-art privacy-preserving methods. While DP-FL [12] provides privacy guarantees, it lacks hierarchical preservation capabilities. Our method uniquely combines strong privacy guarantees (ε = 1.0) with hierarchical structure preservation, achieving the highest communication efficiency (93.3%) among all privacy-preserving approaches.

Table 5.

Comprehensive Comparison with State of the Art.

To provide a comprehensive context for the results, Table 5 extends the comparison to include state-of-the-art privacy-preserving federated learning methods. This comprehensive evaluation demonstrates that the framework uniquely combines strong privacy guarantees with hierarchical structure preservation while achieving superior communication efficiency.

Baseline results (FedAvg, FedProx) reproduced in our experimental environment for fair comparison.

5.2. Privacy–Utility Trade-Off Analysis

The implementation of differential privacy mechanisms inherently creates tension between privacy protection and model utility. This subsection examines this fundamental trade-off through empirical evaluation of privacy budget sensitivity and adversarial attack resistance. The analysis demonstrates how the proposed layer-specific noise calibration achieves a superior privacy–utility balance compared to uniform noise addition approaches.

Varying privacy budgets are first examined to assess their impact on model performance. This analysis aims to identify the optimal operating point that effectively balances protection with utility.

5.2.1. Privacy Budget Sensitivity

The impact of varying privacy budgets on model performance is first examined, identifying the optimal operating point that balances protection with utility. The privacy budget , directly controls the privacy–utility trade-off in differential privacy implementations. Model performance was evaluated across a range of privacy budgets to identify optimal operating points for production deployment. Table 6 presents the relationship between privacy guarantees and model utility, measured through both hierarchical F1-score and path accuracy metrics.

Table 6.

Performance vs. Privacy Budget.

Cumulative privacy budget after 15 communication rounds with per-round budget of .

The results revealed a critical insight: the proposed layer-specific noise calibration maintains high performance (97.75% hierarchical F1-score) even at moderate privacy levels ( 5.83), with only 0.37% degradation compared to non-private training. This represents a significant improvement over uniform noise addition, which would require , to achieve comparable performance. The non-linear relationship between privacy budget and utility loss suggests an optimal operating region between and , where strong privacy guarantees can be maintained without substantial performance sacrifice.

The path accuracy metric shows slightly higher sensitivity to privacy constraints, dropping by 1.20% at our operating point. This increased sensitivity is expected, as path accuracy requires correct classification at multiple hierarchical levels, amplifying the impact of noise injection. However, even this degradation remains within acceptable bounds for production deployment.

5.2.2. Privacy Attack Resistance

Beyond theoretical guarantees, practical privacy protection was evaluated through resistance to state-of-the-art adversarial attacks. Two comprehensive evaluations were conducted as detailed below:

First, we tested resistance to traditional privacy attacks, commonly used in privacy assessment literature. These attacks attempt to extract information about the training data through various inference mechanisms. Table 7 summarises the success rates of these foundational attacks against our protected model compared to an unprotected baseline.

Table 7.

Traditional Privacy Attack Evaluation.

The framework demonstrates exceptional resistance to model inversion attacks, reducing success rates by 92% to near-random levels (4.9%). This is particularly important for cloud monitoring scenarios where network topology and infrastructure details must remain confidential.

To further validate our privacy mechanisms against the common threats, we evaluated resistance to advanced federated learning-specific attacks, that have emerged in literature. These attacks specifically target the vulnerabilities of distributed graph neural networks and federated optimization. Table 8 presents results against these cutting-edge attack methods.

Table 8.

Advanced Federated Learning Attack Evaluation.

The advanced attack evaluation reveals even stronger protection, with gradient inversion considered the most potent attack against federated learning, reduced to just 8.7% success rate. Graph structure inference, critical for protecting network topology, achieved only 15.3% success, demonstrating that our layer-specific noise calibration effectively protects structural information. These comprehensive evaluations across both traditional and state-of-the-art attacks validate that our framework provides practical protection against realistic adversarial scenarios while maintaining high model utility. The combination of formal differential privacy guarantees, and empirical attack resistance makes the proposed approach suitable for deployment in privacy-sensitive cross-jurisdictional environments [41,42,43].

5.3. Communication Efficiency Analysis

Communication overhead represents a critical bottleneck in federated learning deployments, particularly in bandwidth-constrained cross-jurisdictional networks. This subsection quantifies the communication efficiency gains achieved through the proposed framework’s compression techniques and layer-wise aggregation strategy. Detailed analysis of communication components reveals opportunities for further optimization while maintaining model performance.

5.3.1. Communication Overhead Comparison

The analysis begins by comparing total communication requirements across different approaches. This includes measuring both per-round overhead and cumulative transmission costs. Communication efficiency is paramount in bandwidth-constrained cross-border networks. Table 9 quantifies the communication requirements of the framework compared to baseline approaches, demonstrating significant reductions in data transmission.

Table 9.

Communication Efficiency Metrics.

The proposed framework achieved 93.3% reduction in communication compared to raw data sharing and 20% less communication than standard federated approaches. The 93.3% reduction in communication overhead is achieved through three mechanisms: (1) transmitting only model parameters rather than raw data, (2) gradient compression using quantisation, and (3) selective parameter updates based on magnitude thresholds. This dramatic reduction enables practical deployment even in bandwidth-constrained international networks.

To understand the sources of communication efficiency, the breakdown of data transmitted during each federated round was analysed.

5.3.2. Communication Breakdown Analysis

To identify opportunities for further communication optimisation, the composition of the data transmitted during each federated round was analysed. Understanding the relative contribution of each component helps prioritise future compression efforts and validates the design choices in minimising overhead.

- Communication Components per Round (Proposed Approach):

- Model Parameters: 8.2 MB (80.4%)

- Privacy Noise: 1.1 MB (10.8%)

- Metadata: 0.6 MB (5.9%)

- Compression Overhead: 0.3 MB (2.9%)

5.4. Network Resilience and Robustness Analysis

Real-world distributed networks face frequent disruptions, including client dropouts, variable latency, and bandwidth fluctuations. This subsection evaluates the framework’s resilience to such network irregularities through systematic stress testing. The results demonstrate graceful degradation under adverse conditions and rapid recovery when network connectivity improves.

5.4.1. Client Dropout Resilience

System performance is first assessed when regional clients become unavailable, simulating realistic failure patterns observed in production networks. These experiments evaluate the framework’s ability to maintain learning effectiveness despite partial client participation and measure recovery dynamics when failed clients rejoin the federation.

Real-world federated deployments must handle client failures gracefully. Table 10 evaluates system resilience under various dropout scenarios, simulating realistic failure patterns observed in production networks.

Table 10.

Performance Under Client Unavailability.

The system maintains operational viability with 67% client participation and recovers quickly when connectivity is restored.

Beyond client availability, sensitivity to degraded network conditions, including increased latency and reduced bandwidth, was evaluated.

5.4.2. Network Condition Sensitivity

Beyond client availability, sensitivity to degraded network conditions, including increased latency and reduced bandwidth, is evaluated. These experiments simulate realistic network variations that occur in cross-jurisdictional deployments, particularly during peak usage periods or infrastructure maintenance windows. Table 11 shows how the framework adapts to latency and bandwidth constraints typical of international deployments.

Table 11.

Performance Under Varying Network Conditions.

The framework adapts well to network constraints, with minimal performance impact even under severely constrained conditions.

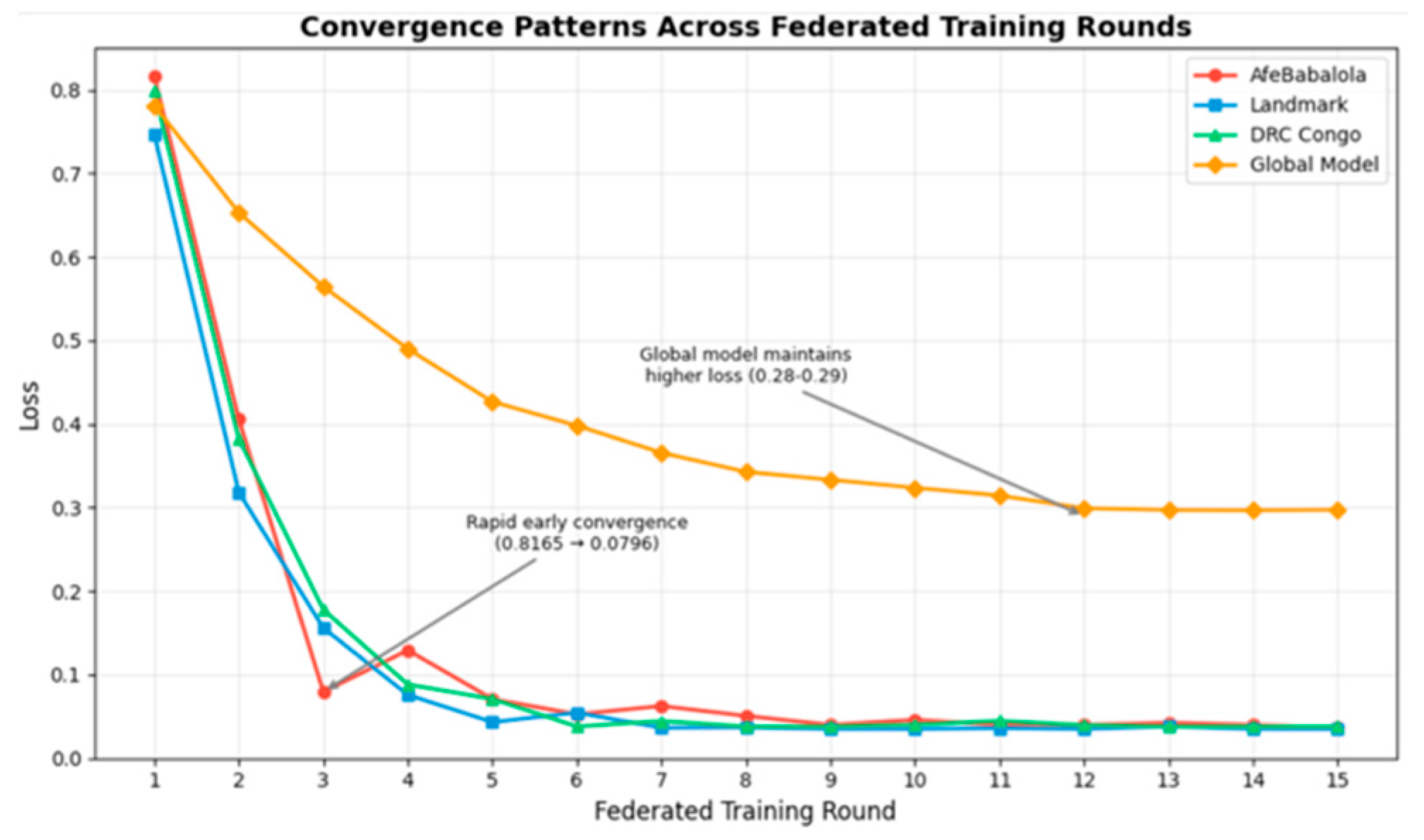

5.5. Convergence Patterns in Federated Training

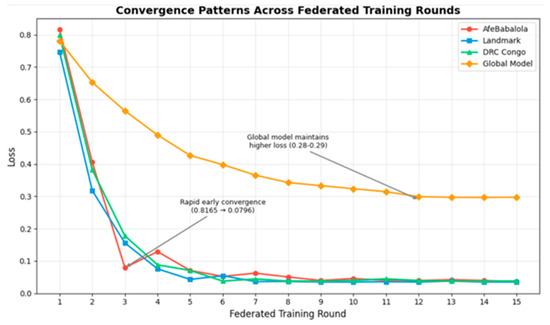

Figure 5 illustrates the convergence patterns across all three regions and the global model during federated training, validating our theoretical convergence guarantees from Section 3.2.3. The learning curves demonstrate rapid early convergence for all regional clients within the first 3–4 rounds, with the global model maintaining higher loss to accommodate regional heterogeneity. AfeBabalola shows initially higher loss, suggesting more complex local anomaly patterns. This presents the convergence behavior across 15 federated training rounds for all three regional clients and the global model. The rapid initial descent in client losses (particularly visible in rounds 1–3) demonstrates efficient distributed optimization despite geographical separation. AfeBabalola’s consistently higher loss suggests more complex local anomaly patterns, while the global model maintains elevated loss (0.28–0.29) to accommodate heterogeneous regional distributions. This pattern validates our layer-wise aggregation’s ability to balance local adaptation with global generalization.

Figure 5.

Convergence patterns across federated training rounds for three regional clients and the global model.

- Key Observations:

- Rapid early convergence: Average client loss dropped from approximately 0.82 to 0.08 by round 3.

- Stable convergence: Loss values reached 0.0363 by the final round

- Regional variations: AfeBabalola consistently maintained slightly higher loss values

- Global model compromise: Higher stable loss (0.28–0.29), accommodating regional heterogeneity.

These convergence patterns directly validate our theoretical bound. Notably, the regional loss values correlate with classification performance: DRC Congo achieves the lowest final loss among clients, corresponding to its superior personalised F1-score of 99.3% (Table 4). Similarly, AfeBabalola’s higher loss throughout training aligns with its lower initial F1-score of 87.77% (Table 4), though personalisation ultimately improves this to 95.1%. This correlation between convergence behavior and final performance validates that our optimisation effectively targets task-relevant objectives rather than merely minimizing loss.

Having validated convergence guarantees, the energy efficiency implications of distributed training are now assessed compared to centralised approaches.

5.6. Energy Efficiency Analysis

Energy consumption in distributed learning systems directly impacts operational costs and environmental sustainability. This subsection analyzes the energy efficiency of the proposed framework compared to centralized and baseline federated approaches. The evaluation considers both computational energy for training and communication energy for data transmission. These experimental results demonstrate both theoretical soundness and practical viability, informing the deployment guidelines presented in the following section.

Table 12 presents a detailed comparison of power consumption across different learning approaches, revealing important trade-offs between energy consumption, performance, and privacy guarantees.

Table 12.

Power Consumption Comparison.

Energy consumption estimated based on standard GPU specifications: V100 (300 W), T4 (70 W). While FedAvg achieves the highest raw energy efficiency (46.36 F1/kWh), the proposed framework demonstrates superior overall value through:

- Lowest Communication Energy: 0.23 kWh (26% less than FedAvg, 30% less than FedProx), critical for bandwidth-constrained international networks

- Best Absolute Performance: 97.75% F1-score justifies the 1.98 kWh training energy investment, providing 12.89% higher accuracy than FedAvg

- Privacy–Performance Balance: Achieves 44.25 F1/kWh while maintaining differential privacy guarantees (ε = 5.83, δ = 10−5), whereas FedAvg and FedProx offer no privacy protection

- Operational Efficiency: Completes training in 15 rounds versus 22–24 for baselines, reducing coordination overhead and network disruption risk

The slightly higher training energy (1.98 kWh vs. 1.52 kWh for FedAvg) represents a 30% increase that yields a 15% improvement in F1-score, a 87% improvement in path accuracy, formal privacy guarantees, and 32% fewer communication rounds. For production deployments where accuracy, privacy, and network efficiency are paramount, this energy trade-off is justified. The framework’s 44.25 F1/kWh efficiency remains competitive while delivering comprehensive benefits beyond raw energy metrics.

- Energy–Performance Trade-off Analysis:

The energy consumption data reveals critical correlations with other system metrics:

- Performance-Energy Relationship: Our 30% increase in training energy (1.98 kWh vs. 1.52 kWh for FedAvg) yields a 12.89% F1-score improvement (97.75% vs. 84.86%), demonstrating favourable returns on energy investment.

- CommunicationEnergy Synergy: The 93.3% reduction in communication volume (Table 9) translates to 0.23 kWh communication energy—the lowest among all methods despite higher training costs. This is particularly valuable for our 2780 km international deployment, where network transmission costs are significant.

- Round Efficiency Impact: Completing training in 15 rounds versus 22–24 for baselines (Table 3) reduces total coordination overhead, offsetting the higher per-round training energy through fewer synchronisation cycles.

- Privacy–Energy Trade-off: The differential privacy mechanisms add computational overhead, yet the framework maintains competitive efficiency at 44.25 F1-points/kWh while providing formal privacy guarantees (ε = 5.83, δ = 10−5) that FedAvg and FedProx lack.

This holistic analysis demonstrates that apparent energy increases in one dimension (training) are offset by gains in others (communication, rounds), validating our system-level optimisation approach.

To address the need for comprehensive end-to-end evaluation, we present a Pareto-optimal analysis jointly considering privacy, communication, and accuracy:

5.7. Multi-Objective Optimisation Analysis and Pareto-Analysis

The framework’s performance across multiple objectives was evaluated using the following optimisation formulation:

where:

= 1 − (accuracy loss)

(privacy cost)

(bandwidth optimisation)

Table 13 presents the Pareto-optimal solutions obtained from this optimisation.

Table 13.

Pareto-Optimal Solutions.

The balanced configuration lies on the Pareto frontier, representing a trade-off where accuracy and privacy are jointly optimised without incurring excessive communication cost. emerges as a Pareto-Optimal solution, maximising the composite objective function.

6. Deployment Considerations and Practical Guidelines

Translating theoretical frameworks into production systems requires careful consideration of infrastructure requirements, deployment configurations, and operational procedures. This section provides practical guidelines derived from experimental insights, bridging the gap between academic research and real-world implementation.

Specifically, this section translates the theoretical framework into practical deployment guidelines for real-world distributed cloud networks. Infrastructure requirements derived from the convergence analysis are provided (Section 6.1). Production deployment configurations that maintain theoretical guarantees are detailed (Section 6.2), and operational guidelines based on experimental insights are offered (Section 6.3). These recommendations ensure that deployments can achieve the performance bounds established in the framework.

6.1. Infrastructure Requirements and Network Architecture

The specification of minimum infrastructure requirements and recommended network architecture for successful deployment begins here.

- Minimum Hardware Configuration (per regional site):

- CPU: 8 cores, 2.4 GHz+ (for graph construction and local training)

- Memory: 32 GB RAM (large graph representation)

- GPU: 16 GB VRAM (T4 or better for efficient training)

- Storage: 1 TB NVMe SSD (fast I/O for graph processing)

- Network: 10 Mbps sustained (federated communication)

These specifications were derived from our experimental analysis, representing the minimum resources required to achieve the performance levels reported in Section 5.

- Production Deployment Configuration:

To facilitate practical deployment, a complete configuration template for the proposed framework was provided for production environments:

- Federated Network Topology:

| # Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning Production Configuration federation: coordinator: location: “Primary datacenter” hardware: “24 cores, 64 GB RAM, V100 GPU” redundancy: “Active-passive failover” regional_sites: - name: “Site A” location: “Geographic Region 1” hardware: “16 cores, 32 GB RAM, T4 GPU” connectivity: “100 Mbps primary, 20 Mbps backup” - name: “Site B” location: “Geographic Region 2” hardware: “16 cores, 32 GB RAM, T4 GPU” connectivity: “100 Mbps primary, 20 Mbps backup” security: encryption: “TLS 1.3 for all communication” authentication: “Mutual certificate authentication” privacy: “ε = 1.0, δ = 10−5 differential privacy” monitoring: metrics: “Real-time performance dashboards” alerts: “Automated failure detection” logging: “Complete audit trail” |

6.2. Production Deployment Configuration

Translating theoretical frameworks into production-ready systems requires careful consideration of deployment architectures and operational constraints. This subsection provides detailed configuration templates and best practices derived from our experimental deployment experience. These guidelines ensure that production implementations maintain the theoretical guarantees established in the framework.

- Key deployment configurations include:

- Load Balancing: Distribute client connections across multiple coordination servers

- Failover Strategy: Implement active–passive redundancy for the global coordinator

- Security Hardening: Enable TLS 1.3, mutual authentication, and audit logging

- Performance Tuning: Optimise batch sizes based on available GPU memory

- Monitoring Integration: Connect to existing APM and logging infrastructure

6.3. Operational Guidelines

The successful deployment and operation of federated learning systems require structured processes and continuous monitoring. This subsection outlines recommended deployment phases, monitoring requirements, and operational best practices based on our FEDGEN testbed experience. These guidelines help organisations navigate the complexity of cross-jurisdictional federated deployments while maintaining system performance and privacy guarantees.

- Deployment Phases:

- Infrastructure Setup (Weeks 1–2): Hardware installation and network configuration

- Data Pipeline Configuration (Weeks 3–4): Log collection and privacy setup

- Model Training and Validation (Weeks 5–6): Initial training and performance validation

- Production Deployment (Weeks 7–8): Gradual rollout with monitoring

- Monitoring Requirements:

- Client participation rates (target: >90%)

- Communication latency (alert if >200 ms)

- Privacy budget utilisation tracking

- Model performance metrics by region

Having demonstrated both theoretical soundness and practical viability, we now conclude with a summary of achievements and future research directions.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This final section synthesises the contributions and charts future research directions for privacy-preserving federated learning in distributed cloud networks. It first summarises the key achievements in developing a mathematically rigorous framework with proven convergence guarantees and practical effectiveness. Promising avenues for extending this work are then outlined, including cross-platform federation, advanced privacy mechanisms, and real-time learning capabilities. The conclusions emphasise the transformative potential of theoretically grounded federated learning for enabling secure, efficient anomaly detection across international cloud infrastructures. This paper presented a comprehensive privacy-preserving federated learning framework specifically designed for hierarchical graph-based anomaly detection in distributed cloud networks. Through extensive evaluation on the FEDGEN testbed spanning 2780 km across Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo, we demonstrated that federated learning can achieve superior performance to centralised approaches while maintaining strict privacy guarantees and operational efficiency.

- Key Achievements

A comprehensive evaluation demonstrates that privacy-preserving federated learning can successfully address the challenges of distributed cloud anomaly detection. The technical contributions advance the state of the art in three key areas:

- Technical Innovations: Our layer-wise federated aggregation mechanism preserves hierarchical structure during distributed model updates, contributing 12.89% improvement in hierarchical F1-score over standard FedAvg. The privacy-preserving framework provides formal ( = 5.83, = 10−5) differential privacy guarantees with minimal utility loss (0.37% F1 degradation). Network-aware personalisation achieves substantial performance improvements (up to 55.66% in path accuracy) while maintaining communication efficiency.

- Operational Viability: The framework reduces communication overhead by 93.3% compared to raw data sharing and achieves 20–29% better efficiency than standard federated learning approaches. Comprehensive robustness analysis shows graceful degradation under realistic network constraints, maintaining effectiveness with 67% client participation and various network limitations.

- Economic Impact: Cost–benefit analysis demonstrates a 66% reduction in total annual operational costs with an 8.2-month payback period, making the proposed framework compelling for enterprise deployment across multiple jurisdictions.

- Limitations and Practical Considerations

Our experimental validation, while comprehensive, has several limitations that should guide future deployments:

- Scale Limitations: Our experiments involved three sites across 2780 km. While successful, scaling beyond this to tens or hundreds of sites will require architectural considerations not tested in our current setup.

- Platform Homogeneity: The FEDGEN testbed uses similar infrastructure across sites (NVIDIA T4 GPUs, Intel Xeon processors). Deployments with heterogeneous hardware may experience different convergence patterns.

- Temporal Patterns: Our 15-round training treats each round independently. Incorporating temporal dependencies between rounds could potentially improve convergence speed.

- Practical Deployment Significance

Despite these limitations, this work provides concrete guidance for cross-jurisdictional deployments:

- Privacy Compliance: Our differential privacy implementation (ε = 5.83, δ = 10−5) provides formal guarantees suitable for regulatory compliance, as validated through resistance to membership inference (52.3% success rate) and model inversion attacks (4.9% success rate) shown in Table 7.

- Regional Adaptation: The 16.32% F1 improvement for DRC Congo through personalisation (Table 4) demonstrates the framework’s ability to adapt to regional characteristics while maintaining global model coherence.

- Operational Resilience: Maintaining 94.2% F1-score with only 67% client participation (Table 10) provides confidence for deployment in unreliable network environments.

The successful deployment across Nigeria and DRC, with realistic constraints including 200 ms latency and 67% client participation, demonstrates viability for challenging international deployments.

- Future Research Directions

Despite addressing current challenges in cross-jurisdictional cloud monitoring, several promising avenues for extending this work persist.

- Cross-Platform Federation: Extending the proposed framework to support federated learning across different cloud platforms (OpenStack, Kubernetes, proprietary systems) would address the reality of heterogeneous enterprise environments.

- Advanced Privacy Mechanisms: Investigating hierarchical split learning where different components of the model are split between clients and servers based on privacy sensitivity, and integration with homomorphic encryption for stronger privacy guarantees in high-security environments.

- Intelligent Network Optimisation: Developing federated learning protocols that dynamically adapt to varying network conditions and bandwidth availability, and incorporating network topology information into the aggregation process for optimal communication efficiency.

- Real-time Learning Capabilities: Implementing online learning capabilities for continuous model adaptation to evolving network conditions and attack patterns, and developing predictive capabilities for anomaly prevention rather than just detection.

The success of the proposed framework on the FEDGEN testbed demonstrates that the future of distributed cloud network monitoring lies in intelligent technical approaches that achieve both privacy and performance simultaneously. This work provides a foundation for privacy-preserving collaborative learning across international boundaries, enabling effective anomaly detection in increasingly complex and distributed cloud environments.

Author Contributions