Abstract

Condition monitoring has come to the forefront of intelligent manufacturing and is particularly important in Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining processes, where reliability, precision, and productivity are crucial. The traditional methods of monitoring, which are mostly premised on single sensors, the localized capture of data, and offline interpretation, are proving too small to handle current machining processes. Being limited in their scale, having limited computational power, and not being responsive in real-time, they do not fit well in a dynamic and data-intensive production environment. Recent progress in the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), cloud computing, and edge intelligence has led to a push into distributed monitoring architectures capable of obtaining, processing, and interpreting large amounts of heterogeneous machining data. Such innovations have facilitated more adaptive decision-making approaches, which have helped in supporting predictive maintenance, enhancing machining stability, tool lifespan, and data-driven optimization in manufacturing businesses. A structured literature search was conducted across major scientific databases, and eligible studies were synthesized qualitatively. This systematic review synthesizes over 180 peer-reviewed studies found in major scientific databases, using specific inclusion criteria and a PRISMA-guided screening process. It provides a comprehensive look at sensor technologies, data acquisition systems, cloud–edge–IoT frameworks, and digital twin implementations from an architectural perspective. At the same time, it identifies ongoing challenges related to industrial scalability, standardization, and the maturity of deployment. The combination of cloud platforms and edge intelligence is of particular interest, with emphasis placed on how the two ensure a balance in the computational load and latency, and improve system reliability. The review is a synthesis of the major advances associated with sensor technologies, data collection approaches, machine operations, machine learning, deep learning methods, and digital twins. The paper concludes with what can and cannot be performed to date by providing a comparative analysis of what is known about this topic and the reported industrial case applications. The main issues, such as the inconsistency of data, the lack of standardization, cyber threats, and old system integration, are critically analyzed. Lastly, new research directions are touched upon, including hybrid cloud–edge intelligence, advanced AI models, and adaptive multisensory fusion, which is oriented to autonomous and self-evolving CNC monitoring systems in line with the Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0 paradigms. The review process was made transparent and repeatable by using a PRISMA-guided approach to qualitative synthesis and literature screening.

1. Introduction

The key to contemporary manufacturing industries such as aerospace, automotive, energy, mold-and-die, and precision medical device manufacturing is Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machine tools [1]. The emerging requirements of high precision, productivity, sustainability, and operational independence require CNC systems to be capable of providing consistent quality with minimum downtime. Although CNC machines are critical, they are by nature vulnerable to the wearing of tools, thermal deformation, vibration, structural degradation, and control-related faults, all of which negatively influence machining precision and productivity [2,3,4].

CNC machine tools represent intricate cyber-physical manufacturing systems [1]. These systems bring together high-speed spindles, multi-axis servo drives, numerical controllers, and cutting processes. Their goal is to achieve both high precision and impressive productivity. Machining processes are inherently sensitive to several factors, including tool wear, chatter vibration, thermal deformation, spindle and bearing wear, servo drive issues, and unusual energy use. Therefore, continuous monitoring of their condition and status is essential to ensure machining accuracy, reliability, and reduced downtime.

Conventional approaches to maintenance, e.g., reactive repair and planned preventive maintenance, have been found to be unable to meet the needs of complex, high-mix, and low-volume production settings [3,5]. These solutions have the side effect of causing needless downtime, higher maintenance expenses, and low responsiveness to unforeseen failures [6,7]. In response, condition monitoring (CM), predictive maintenance (PdM), and intelligent diagnostic methods have become the enabling technologies of smart manufacturing and Industry 4.0, and provide proactive solutions that enhance reliability, efficiency, and operational flexibility [5,7,8].

The recent developments in sensor technology, the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI), and digital twin (DT) models have created an essential change in how CNC machines are monitored, analyzed, and optimized throughout their life cycle of operation [5,9,10]. Technology makes it possible to take data in real-time, perform advanced analytics, and use closed-loop decision-making, assisting CNC machining systems that are becoming more adaptive, data-driven, and autonomous [11].

The earliest CNC condition-monitoring systems were mostly based on a single sensor, e.g., vibration or spindle current, coupled with threshold-based alarm strategies. Although these methods were suitable for determining serious faults, they were not strong, flexible, or scalable to different machining conditions [12,13]. With increasingly complicated machining processes, studies began to concentrate more on multi-sensor monitoring strategies that combined vibration, acoustic emission, cutting force, temperature, and power consumption signals to improve diagnostic quality [5,14,15].

Since then, data-driven models such as support vector machines, artificial neural networks, random forests, and deep architectures have been applied to the research of CNC condition monitoring [14,16,17,18]. Such techniques have been shown to perform well in tool wear prediction, chatter detection, and fault classification. Nonetheless, these are frequently constrained by limitations on their effectiveness, including limited data access, inability to generalize to a different machining scenario, and limited physical interpretability [4,14].

Hybrid methods that use physics-based models combined with data-driven techniques have received more interest in recent years. Combining the models of analytical machining and machine learning algorithms, such approaches contribute to improving robustness and improving interpretability [2,7,19]. This development has inherently contributed to the implementation of digital twin systems, where virtual models of CNC machines are kept in real-time contact with their real-world equivalents with real-time data streams [20,21].

High CNC sensor data scaling has revealed the weaknesses of standalone and edge-only monitoring architectures, especially in processing capability, storage capacity, and scalability. An alternative solution is provided by cloud computing, as it allows for managing data centrally, performing massive analytics, and sharing knowledge across machines [22,23]. Manufacturers can use cloud-based CNC monitoring systems to gather information across geographically scattered machines, implement AI models with heavy computational demands, and conduct fleet-level diagnostics and benchmarking [24,25]. A further improvement in long-term reliability and performance is provided by continuous model updating and lifecycle optimization.

Other research papers have shown that cloud-based CNC monitoring systems are feasible and have advantages such as better accuracy in fault detection, less expensive maintenance, and greater transparency of the system [26,27,28,29]. However, the use of architectures based solely on cloud-based solutions exposes major difficulties, including communication delays, bandwidth restrictions, information privacy, and constraints to real-time control [30,31].

To address these drawbacks, cloud–edge collaborative architectures have become the paradigm in CNC condition monitoring and the implementation of digital twins. Time-critical activities, like signal pre-processing and anomaly detection, can be performed on the edge in such systems, and computationally intensive analytics, long-term learning, and optimization can be distributed to the cloud [27,32,33]. Edge intelligence allows us to respond quickly and improve data reliability, whereas cloud intelligence allows us to optimize globally and reuse knowledge in production systems [27,34]. Recently, applications in thermal error compensation, tool wear prediction, and adaptive CNC have been effectively implemented with the help of cloud–edge frameworks [35,36,37]. Such architectures have also been used to build digital twin-driven CNC systems, which allow the constant alignment of physical machines and their virtual representations during the stages of design, operation, and maintenance [29,38,39]. Although the research on CNC condition monitoring, cloud manufacturing, and digital twin technologies has grown very fast, the literature has not been integrated, with a large portion of studies looking at separate elements instead of system-level solutions. The majority of the current research is still dispersed and concentrates on discrete technical elements, despite the fact that many reviews have looked at specific facets of CNC condition monitoring, such as sensing technologies, machine learning algorithms, cloud manufacturing, or digital twin modeling [1,3,5,6,7,10,13]. Integrative, system-level reviews that collectively examine sensor technologies, data acquisition systems, communication infrastructures, and cloud–edge–IoT architectures while specifically addressing architectural trade-offs, scalability limitations, and industrial deployment maturity are still lacking. Specifically, there is still a lack of synthesis in the literature regarding the relationship between cloud–edge collaboration and digital twin implementation in actual CNC monitoring systems.

In line with this, the purpose of this review is to come up with an extensive synthesis of the research on cloud-based CNC condition monitoring. It is structured so that sensor technologies and data acquisition systems are considered first, and then signal processing and AI-based diagnostic methods are discussed. Architectures such as cloud, edge, and hybrid are then examined in terms of scalability and the integration of digital twins. Case studies on the industry are evaluated to determine their practical relevance, unresolved issues, and future research directions. This review is inclined towards subtractive CNC machining, like milling, turning, and multi-axis machine tools, but related hybrid machining and robotic machining studies are referred to where necessary.

This review seeks to address the following research inquiries:

- Which sensing, data acquisition, and analytics methodologies are prevalent in cloud-based CNC monitoring?

- How are cloud–edge architectures and digital twins currently integrated within existing systems?

- What obstacles impede industrial scalability and standardization?

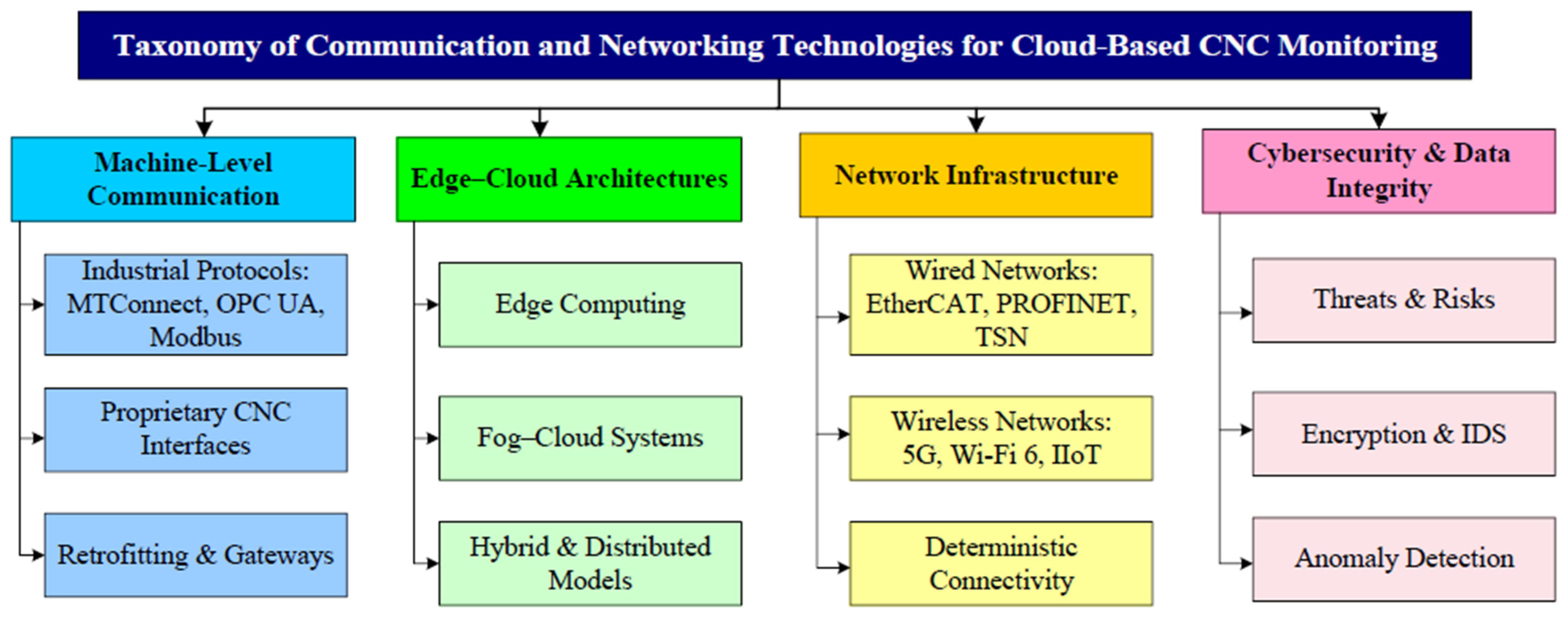

The format of this review is as follows. Sensor technologies and multisensory methods for CNC condition monitoring are reviewed in Section 2. Data acquisition architectures, synchronization techniques, and edge-enabled DAQ systems are covered in Section 3. The networking and communication technologies that enable cloud-based CNC monitoring are reviewed in Section 4. Digital twin integration frameworks and cloud–edge–IoT architectures are examined in Section 5. A comparative analysis of previous research is presented in Section 6, emphasizing methodological trends and constraints. Case studies and reported industrial applications are examined in Section 7. Performance evaluation and validation procedures are reviewed in Section 8. The paper is concluded in Section 10, and open challenges and future research directions are summarized in Section 9.

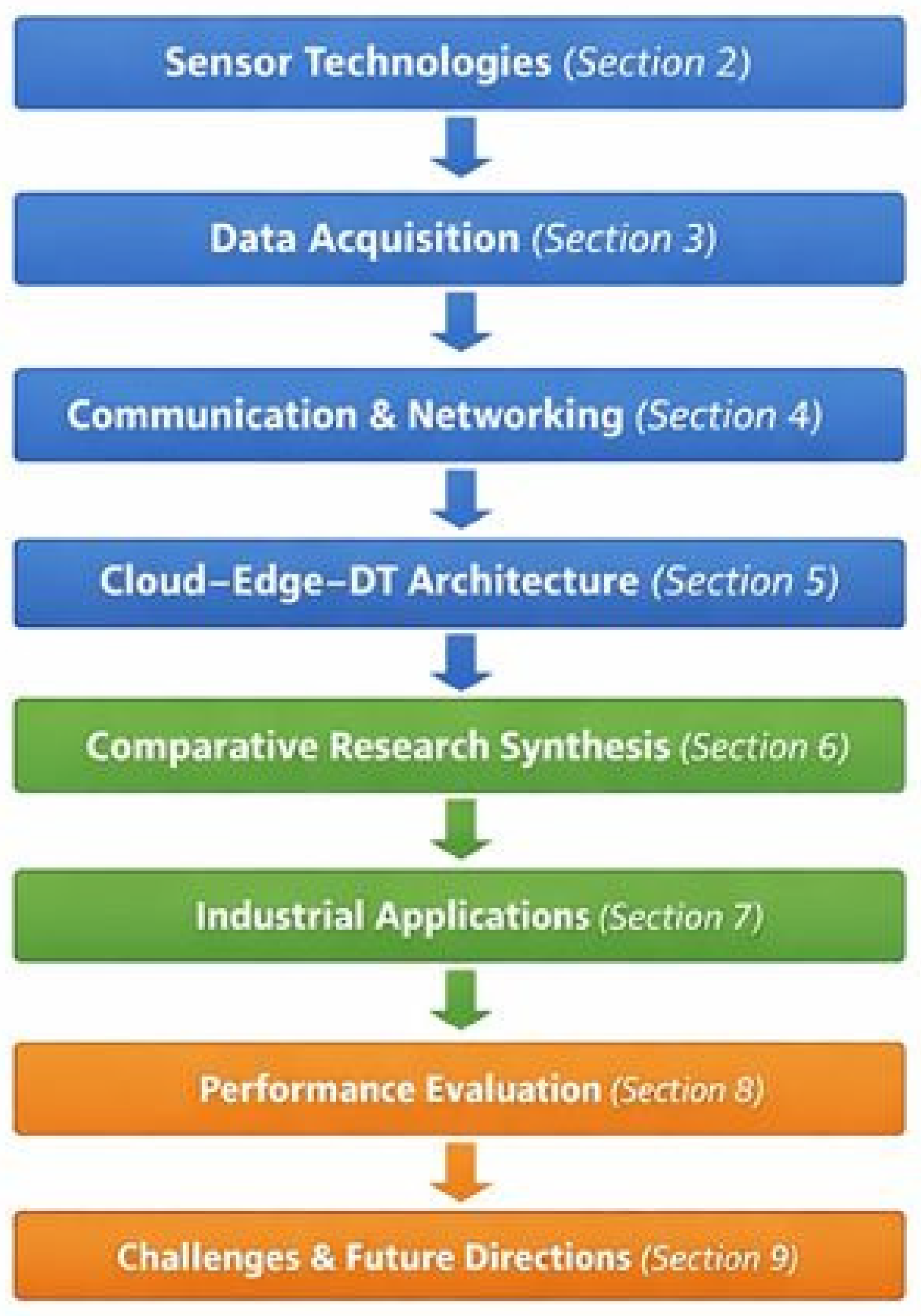

The logical progression of the discussion from sensing technologies and data acquisition to communication infrastructures, cloud–edge–digital twin architectures, comparative research synthesis, industrial applications, performance evaluation, and finally open challenges and future research directions is depicted in Figure 1, which provides a clear overview of the organization of this review. This structured flow highlights how individual technological components evolve into integrated intelligent monitoring systems and how research advances translate into practical industrial deployment.

Figure 1.

Logical framework of the review.

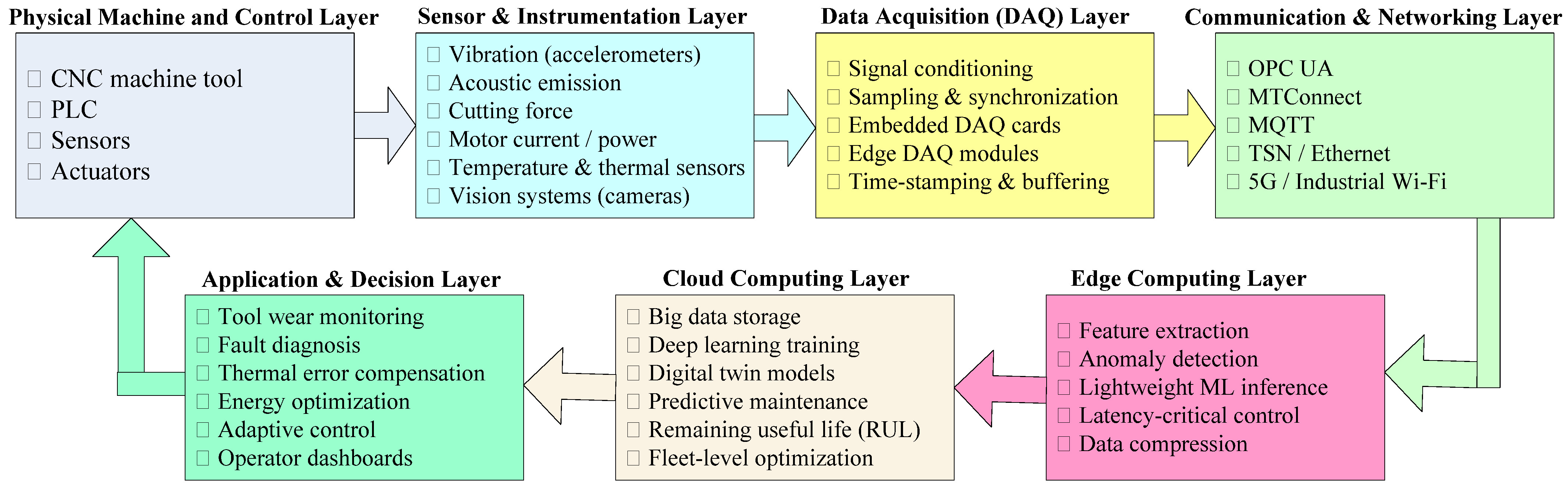

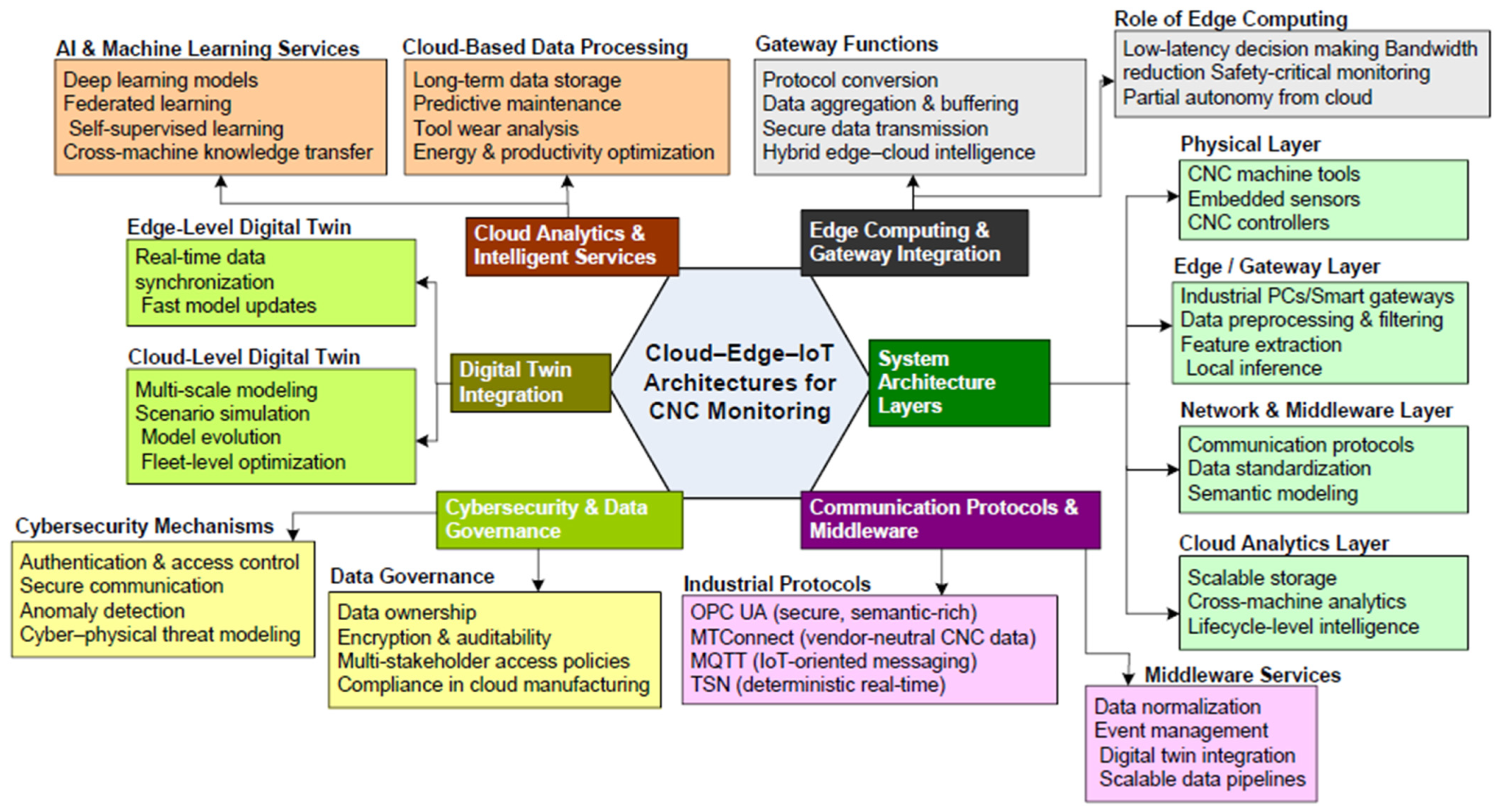

From a system standpoint, sensor technologies, data acquisition systems, industrial communication protocols, and cloud–edge computing platforms must all be integrated for cloud-enabled CNC condition monitoring. The general taxonomy and layered system architecture that support contemporary intelligent CNC monitoring and digital twin integration are shown in Figure 2. While Figure 2 presents the technical architecture of cloud-enabled CNC monitoring systems, the organization of the present review itself is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Taxonomy and layered system architecture of cloud-enabled condition monitoring for CNC machine tools.

Methodology of Literature Search and Selection

The method used to find and choose literature was carefully designed to ensure that the most relevant and high-quality studies were included. The search strategy used major scientific databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and MDPI. These databases are well-known for their comprehensive coverage of engineering and technology research. To broaden the scope and include more relevant studies, we also used backward and forward citation tracking. This method helped us find research that either cited or was cited by the articles we initially found.

The search strategy used structured queries, combining key terms about CNC machining and machine tools with ideas related to condition monitoring, predictive maintenance, and advanced digital technologies. These technologies included cloud computing, edge computing, digital twins, and the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). Search queries included combinations of keywords such as the following: (“CNC” OR “machine tool”) AND (“condition monitoring” OR “predictive maintenance”) AND (“cloud computing” OR “edge computing” OR “digital twin” OR “IIoT”). This approach guaranteed a search that was both focused and representative of the various strategies currently being investigated.

To maintain both rigor and focus, specific eligibility criteria were established. The study included only peer-reviewed journal articles and high-quality conference papers. These sources were chosen because they specifically discussed CNC machining or machine tools. The research needed to include topics like condition monitoring, diagnostics, prognostics, or systems that used cloud, edge, or digital twin technologies. In addition, only English-language publications were included to ensure both accessibility and consistency in the analysis.

The selection process was straightforward, but it was also systematic. We first screened the titles and abstracts to find relevant articles. Then, we reviewed the full text of the articles that passed this initial screening to confirm they met the inclusion criteria. This focused approach avoided unnecessary complexity, ensuring that only relevant studies were included. For each study that met the criteria, the data collection process focused on gathering detailed information about the sensing methods used, the data acquisition systems, the analytical techniques, the deployment setups, and the reported results of the applications. These elements were essential for creating comparative tables. These tables highlight the similarities and differences found in the studies, providing a structured way to analyze the data.

Finally, a qualitative assessment of bias risk was performed. To assess the dependability and applicability of the results, we considered factors such as the dataset’s size, the thoroughness of the validation process, the degree to which the study reflected real-world industrial conditions, and any limitations in the ability to reproduce the findings. This step ensured that the synthesis of evidence was thorough and also critically assessed the strengths and weaknesses of the existing research.

The results were synthesized qualitatively, and no quantitative meta-analysis or sensitivity analysis was carried out due to the heterogeneity of study objectives, datasets, and evaluation metrics.

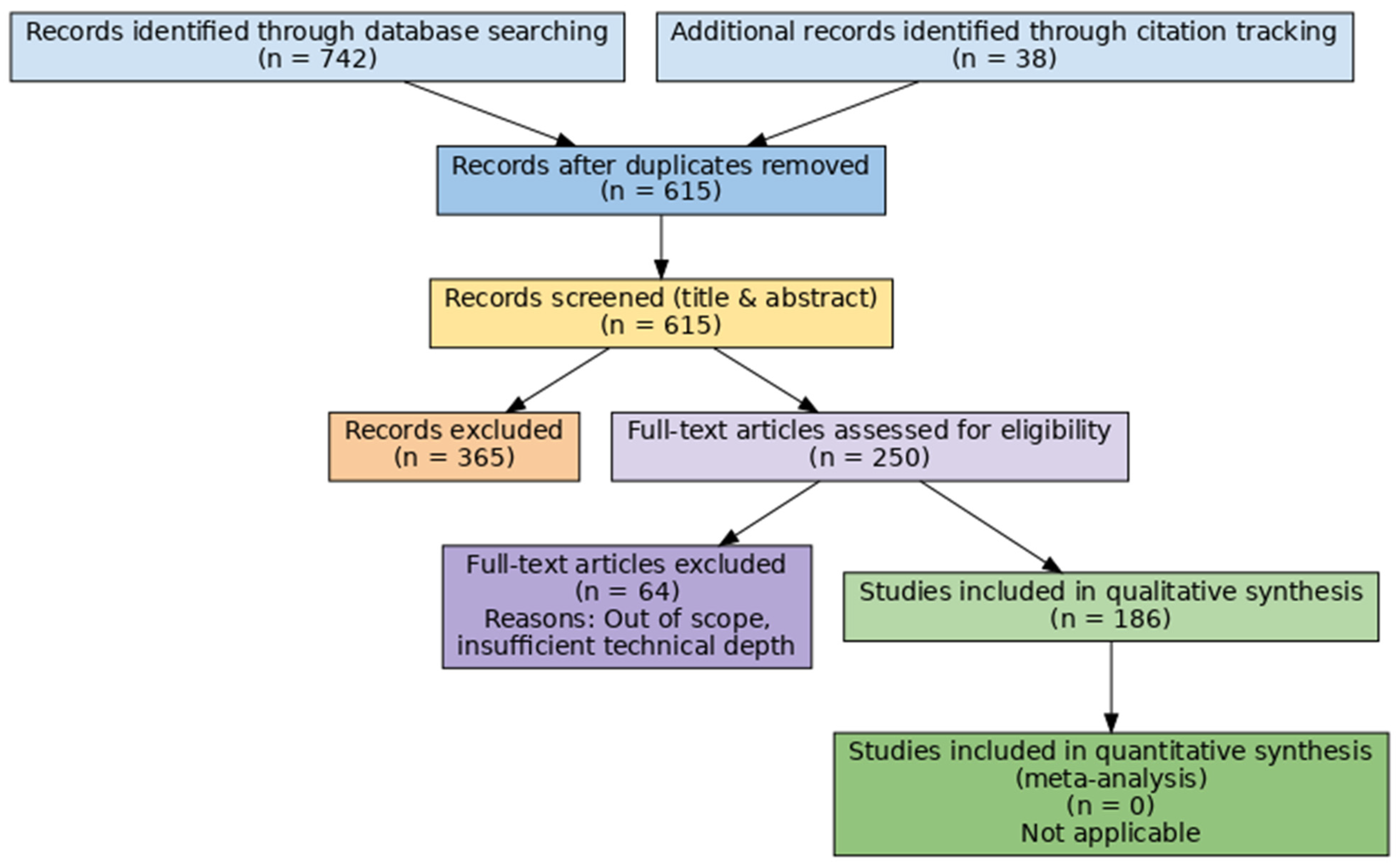

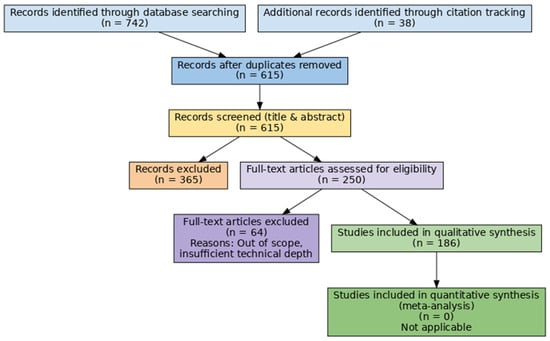

In order to uphold transparency and facilitate reproducibility within the literature selection procedure, this review adheres to the Supplementary Materials, PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework. While this investigation employs a qualitative, engineering-focused review methodology, as opposed to a quantitative meta-analysis, PRISMA guidelines are utilized to explicitly document the processes of identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and the ultimate inclusion of pertinent studies. The flow diagram presented in Figure 3 provides a summary of the multi-stage literature search and selection process, encompassing database retrieval, duplicate removal, title and abstract screening, full-text eligibility assessment, and the final compilation of studies incorporated into the qualitative synthesis of cloud-based CNC condition monitoring and digital twin-enabled architectures.

Figure 3.

The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram shows how studies were found, screened, evaluated for eligibility, and ultimately included in the review. This review focused on cloud-based CNC condition monitoring and digital twin-enabled architectures.

2. Sensor Technologies for CNC Monitoring

Intelligent CNC condition monitoring systems are based on sensor technologies, which enable the real-time recording of process, machine, and environmental data. This shift towards multi-sensor and cyber-physical sensing systems as opposed to traditional, single sensors has dramatically enhanced detection of faults, improved transparency in the processes involved, and enhanced predictive maintenance in contemporary CNC machining machines. Table 1 shows a sensor-based taxonomy of CNC condition monitoring.

Table 1.

Sensor-based taxonomy of CNC condition monitoring.

Although sophisticated sensing technologies, including vibration analysis, acoustic emission monitoring, and vision-based systems, provide considerable diagnostic sensitivity and a wealth of information [8,40,44,51], their widespread implementation in industrial settings frequently encounters limitations [8,12,37]. These limitations stem from the complexities associated with installation, the extensive calibration requirements, the need for environmental resilience, and the overall lifecycle costs [8,12]. Conversely, indirect sensing methodologies, including spindle motor current and power monitoring, offer enhanced integration simplicity, diminished maintenance demands, and superior scalability within industrial CNC settings, despite a compromise in the direct observation of specific mechanical fault modes. Consequently, practical CNC condition monitoring systems frequently balance diagnostic accuracy with how easy they are to implement. They do this by combining high-quality sensors with more affordable, scalable sensing methods, particularly in large-scale or existing manufacturing environments.

2.1. Vibration Sensors

The act of monitoring the condition of CNC machines with vibration is a highly sensitive technique that is still the most frequently used, since it is highly sensitive to the dynamic abnormalities of machine tools, like wear, chatter, issues in bearings, and spindle imbalance. Spindles, tool holders, and machine frames have accelerometers that gather time–domain vibration data, which is processed with frequency–domain, time–frequency, or deep learning models to discern diagnostic information.

As recent studies have discovered, vibration-based monitoring is particularly effective with the use of sophisticated feature extraction and machine learning algorithms. Deep residual (and transfer) learning has been applied to detect chatter and predict tool wear in a range of machining conditions [14,17,52,53]. Simultaneously, data development, especially aimed at vibration-based CNC monitoring, has also facilitated the testing of anomaly detection techniques, and more reproducible studies are possible [15,54]. Recent studies include vibration sensing in digital twins with the ability to keep the actual vibration responses and virtual machine models synchronized to enhance problem diagnosis and prediction capabilities [33,49,55].

2.2. Cutting Force and Motor Current Sensors

Force sensors for the cutting force and measurements of the current in the motor provide firsthand data concerning the forces of interaction between the tool and workpiece. Even though dynamometers offer very high levels of measurement precision, their high cost and complexity of installation have produced an increase in the adoption of indirect sensing (i.e., measuring spindle motor currents and feed drive signals). Practical advantages of these alternatives include integration and scalability, which make them particularly attractive in industrial CNC monitoring applications.

Monitoring of motor currents has also been useful in estimating the tool wear, breakage, and determining energy efficiency [42,44,56]. On this basis, AI-enhanced models for force prediction can enhance resilience because they consider nonlinear dynamics and the complex, coupled effects of processes [57,58]. More recently, force models powered by digital twins have allowed forces to be measured in real-time without intrusive sensors and thus allow adaptive control and compensation in CNC machining strategies [59,60].

2.3. Acoustic Emission and Audio Sensors

Acoustic emission (AE) sensors are used in the detection of the high-frequency stress waves produced during plastic deformation, crack propagation, and tool–chip interactions. Monitoring AE-based AE has especially excelled in detecting tool wear in the early stages and detecting micro-faults, which otherwise would have been overlooked by conventional vibration and force measurements. More recent advancements have used AE signals with deep learning structures to categorize raw signals, leading to high detection rates even in noisy shop-floor conditions [61,62]. Meanwhile, audio-based sensing has also been developed as a cheaper substitute, wherein the microphone data is combined with machine learning to enable the classification of defects and the real-time detection of anomalies [61,63].

2.4. Temperature and Thermal Sensors

The most common causal factor of machining error is that of thermal effects, which contribute nearly 70 percent of the geometric errors in precision CNC machines. In order to minimize distortions, temperature sensors installed in spindles, ball screws, and machine structures will give important information to model and modify thermal errors and achieve higher dimensional accuracy and process stability. Cloud-based thermal monitoring schemes and federated learning schemes have been suggested to enhance the generalization between machines and operating systems [37,46,64]. To complement these enhancements, it should be mentioned that digital twin-assisted thermal models can predict and control volumetric errors introduced by thermal processes in real-time and thereby increase the accuracy and stability of machining in precision CNC systems [36,65,66].

2.5. Vision-Based Sensors

Cameras and laser profilers can be used in machine vision systems as non-contact tools to measure tool wear and surface quality, dimensional accuracy, and defects on the workpiece, without making physical contact with the item being inspected. Monitoring based on vision is being linked more frequently to CNC controllers through IoT and edge computing systems that allow real-time analysis and reactive control in milling systems. High-level image processing methods, coupled with convolutional neural networks, have been very precise in localizing tool wear, surface scars, and geometric anomalies [47,48,67,68]. By improving these innovations, hybrid vision-sensors also enhance the strength of monitoring through the combination of visual and other supplementary signals, like vibration or cutting force data, hence enhancing their dependability across diverse machining conditions [18,69].

2.6. Multi-Sensor Fusion and Cyber-Physical Sensing

Single-sensor devices are often less observable and prone to noise, which reduces the reliability of their diagnostics. Multi-sensor fusion has become the prevailing paradigm in CNC monitoring in order to break these limitations, and consists of vibration, force, temperature, sound emission, vision, and energy information. New frameworks combine deep learning, GNNs, and attention mechanisms to effectively combine dissimilar sensor runs, leading to considerable gains in defect detection and RUL prediction accuracy [51,70,71,72]. Furthering this idea, multi-sensory digital twins align actual physical measurements with the virtual representation of a VM, which enables predictive maintenance and optimization of processes in complex machining scenarios [50,73,74].

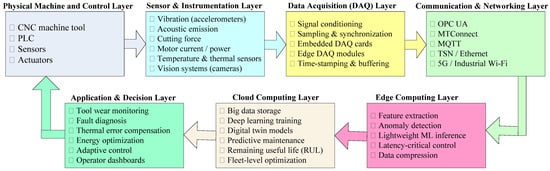

3. Data Acquisition Systems for CNC Condition Monitoring

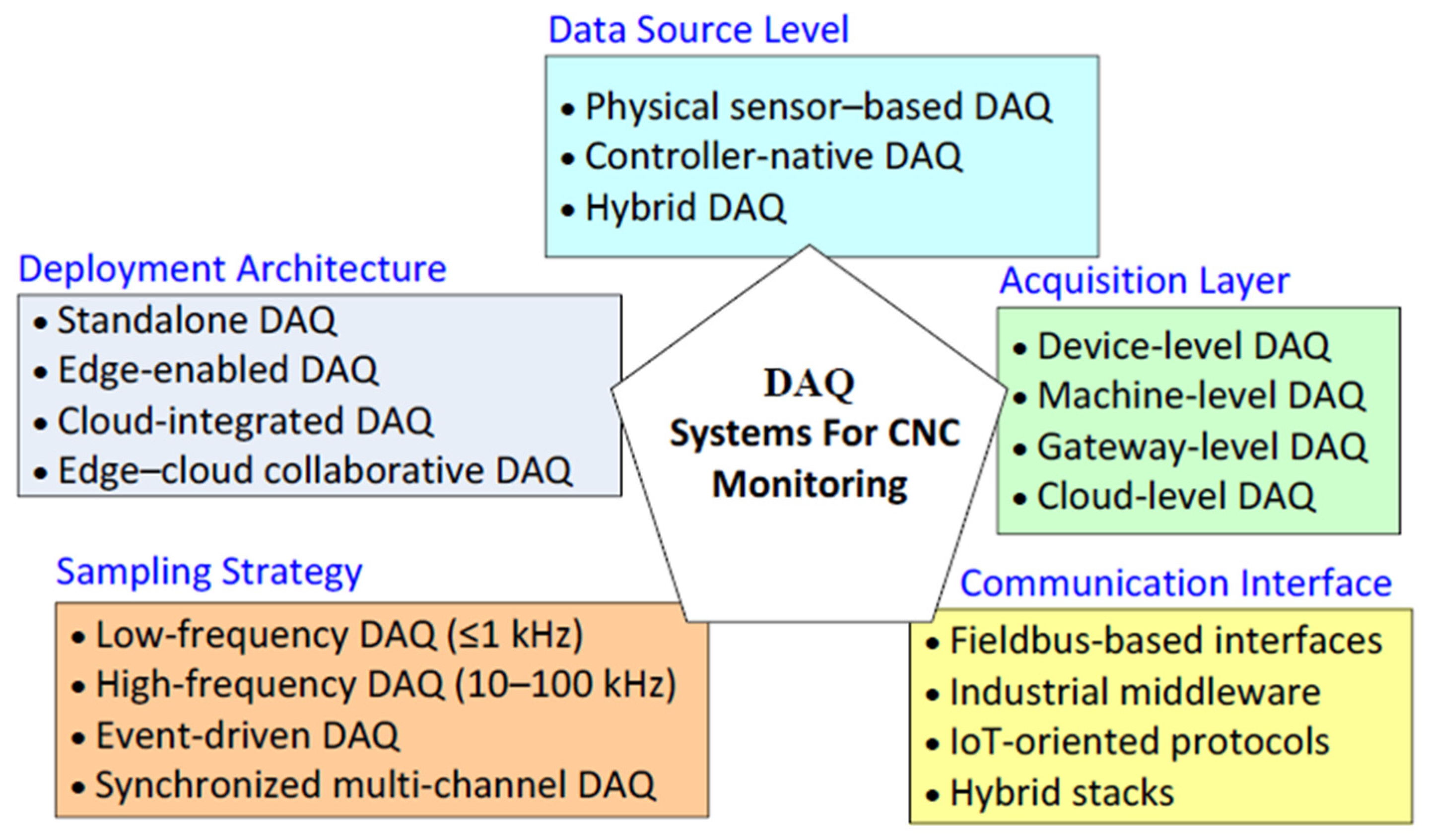

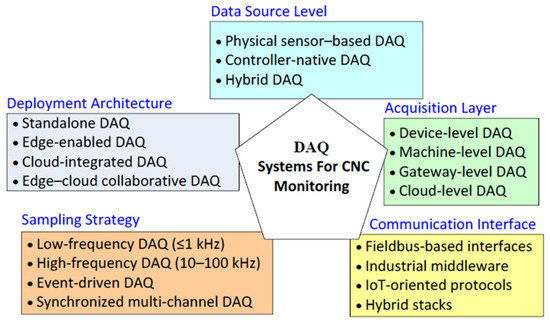

Data acquisition (DAQ) systems serve as a critical interface between real CNC machine tools and upper levels of monitoring, analytics, and cloud intelligence. Cloud-enabled CNC condition monitoring through a system of DAQ is charged with the dependable, high-fidelity acquisition of various heterogeneous signals such as vibration, force, current/temperature, and acoustic emissions, as well as with temporal synchronization, scalability, and seamless interoperability with edge–cloud architecture [15,27,75,76]. Modern data capture systems should enable the simultaneous collection of raw data as well as real-time preprocessing, compression, buffering, and transferring of the data to downstream systems such as digital twins, predictive maintenance engines, and cloud analytics frameworks [27,30,77]. The growing popularity of high-frequency sensing beyond tens of kilohertz underscores the necessity of superior designs for DAQ systems that can accommodate large volumes of data without the loss of packets or other latency-induced degradations [15,78]. In accordance with the literature review, a CNC monitoring system in the form of a DAQ system can be relevantly structured around five complementary dimensions, namely, data origin, layer at which the data is captured, sampling nature, communication interface, and general deployment architecture. Not only does this taxonomy offer a basis on which previous works can be compared, but it also offers a foundation on which the cloud–edge integration solutions in Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7 will be formed. Figure 4, below, is a summary of the said taxonomy.

Figure 4.

Taxonomy of DAQ systems for CNC monitoring.

Studies show clear differences in performance when comparing centralized, cloud-based DAQ systems to those that use edge computing. Cloud-based data acquisition systems often have end-to-end latencies of several hundred milliseconds [15,27,30]. This is due to data transmission and centralized processing, which makes them less suitable for applications that require real-time monitoring and control [15,76]. Conversely, edge-enabled DAQ systems, which conduct local preprocessing and feature extraction, have demonstrated the capacity to diminish effective latency to less than 50 ms [78]. This reduction facilitates near-real-time anomaly detection and adaptive compensation within high-speed CNC machining applications [30]. Synchronization precision, as reported, frequently falls within the microsecond range when employing hardware triggering or network-time protocols. Throughput, however, is contingent upon the specific sensor modality and its corresponding sampling rate; for instance, high-frequency vibration and acoustic emission signals necessitate continuous data rates spanning from tens to hundreds of kilohertz [15,78].

3.1. Hardware Architectures of CNC DAQ Systems

3.1.1. Embedded DAQ Modules

Directly embedded data acquisition modules are being brought into CNC controllers, drive systems, and the cabinets of machine tools. Such architecture frequently employs industrial microcontrollers or higher-speed platforms based on an FPGA to collect high-speed signals with fine timing [75,79]. Redundant and embedded DAQ systems are more suitable for closed-loop tasks involving monitoring and real-time compensation, such as chatter suppression and thermal error correction [37,80]. Nevertheless, embedded DAQ products are limited in their extendibility and computing capability at times, especially in multimodal sensing or sophisticated machine learning applications [30].

3.1.2. External and Modular DAQ Systems

External modular DAQ systems continue to be common in both research and industrial retrofitting applications, particularly with brownfield CNC machines [15,81]. These platforms frequently have multi-channel signal conditioning units, analog-to-digital converters (ADCs), and communication interfaces to connect them to external edge computers or industrial PCs [75]. The increased versatility of modular DAQ systems can easily be reconfigured to a broad spectrum of sensor modalities and experiment configurations. They have found extensive application in tool condition monitoring benchmarks and dataset development projects, where their high accuracy and configurability are of special benefit [15,54].

3.2. Signal Conditioning and Sampling Strategies

Signal conditioning is essential to achieve good quality and reliability of CNC monitoring data results. Amplification, filtering, impedance matching, and isolation are typical conditioning steps that are used to combine and reduce noise due to hostile machining environments [12,82]. Specific adjustments are also required in sampling procedures for the physical phenomena under observation. High-frequency vibration and acoustic emission signals are often examples of signals that require sample rates larger than 20 kHz, although thermal and power signals can be adequately recorded at lower frequencies [43,78]. Multi-rate sampling architectures are also extensively used to strike a balance between data quality and computational performance and permit optimum acquisition of a wide range of sensory modalities [27,35].

3.3. Synchronization and Time-Stamping Mechanisms

Multimodal data fusion and digital twin fidelity require a precise synchrony between different sensor channels. Most CNC DAQ systems require hardware-based triggers, shared clocks, or network-time synchronization protocols to provide temporal alignment [27,83]. Recent studies note that precise time-stamping in the connection between machine dynamics, control signals, and machining processes is important in cloud–edge collaborative settings [32,34]. Fault detection, prediction of tool wear, and causal analysis in cyber-physical CNC systems are more accurate with time-synchronized DAQ data [35,84].

3.4. Communication Interfaces and Data Transmission

DAQ systems are based on industrial communication protocols that transmit gathered data to the edge or cloud platforms. Some of the most widespread interfaces are Ethernet-based protocols, such as OPC UA and EtherCAT, wireless IoT solutions, and hybrid edge–cloud communication systems [27,76,85]. As cloud manufacturing and distributed analytics grow, buffering, compression, and adaptive transmission algorithms are gradually being integrated into DAQ systems to minimize their bandwidth and latency [27,86]. The improved transfer of data is now one of the primary objectives in these systems due to rising concerns about factory cybersecurity [87,88].

3.5. Edge-Enabled DAQ Systems

The extension of edge computing functionality to DAQ systems is a significant deviation from conventional centralized data collection designs. DAQ architectures that are edge-enabled also perform local signal processing, feature extraction, and anomaly detection, and communicate a subset of the data to the cloud [27,33,76]. This distributed approach reduces overhead in communication, enables faster response mechanisms, and enables real-time decision making in applications to CNC condition monitoring [32,34]. Edge-based DAQ systems have been very helpful for high-frequency vibration measurements, chatter measurement, and adaptive control applications [14,53].

4. Communication and Networking Technologies for Cloud-Based CNC Monitoring

The basis of cloud-based CNC monitoring and manufacturing systems that use digital twins is reliable communication and networking infrastructures. The ever-present transfer of high-frequency sensor data, machine control data, predictive analytics data, and machine control orders requires low-latency, scalable, secure, and interoperable communication frameworks. These systems are needed in modern smart machining environments to enable them to stream real-time data between machine tools, edge gateway systems, cloud systems, and enterprise-level manufacturing execution systems (MES) [22,34,85]. Cloud-integrated CNC systems, unlike standalone types, are cyber-physical entities, and the quality of their communication is directly related to the quality of condition monitoring and the reliability of fault diagnosis and predictive maintenance performance [27,33]. Consequently, communication technologies have ceased to be support tools and have instead become strategic enablers of the Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0 manufacturing paradigms [22,89].

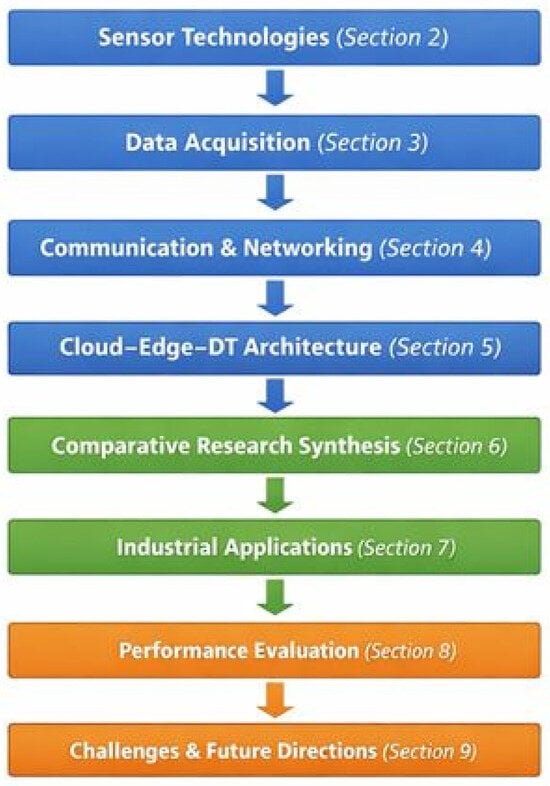

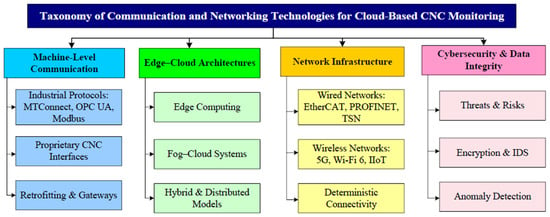

Figure 5 shows a hierarchy of the taxonomy of the available communication and networking technologies applied in cloud-based CNC monitoring. This taxonomy consists of machine-level protocols, edge–cloud architecture, network infrastructure, cybersecurity methods, and new paradigms. It gives a coherent conceptual framework, which forms the basis of the in-depth discussion in Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4.

Figure 5.

A hierarchical taxonomy of communication technologies for cloud-based CNC monitoring.

4.1. Machine-to-Gateway Communication Protocols

Communication protocols are essential at the machine level to transmit raw information to CNC controllers, sensors, and embedded devices. Industrial standards that are generally accepted include MTConnect, OPC UA, Modbus, and proprietary CNC controller interfaces. The data model for machine tool monitoring offered by MTConnect is read-only and vendor-neutral and can be easily integrated with cloud systems [75,85]. OPC UA extends these aspects with two-way communication, semantic data representation, and in-built security processes, which make it especially well suited to smart manufacturing environments [30,85]. Retrofitting is a common practice that allows older controllers to be used with current cloud systems by providing retrofitting options to older CNC machines through industrial gateways and protocol converters [25,81,90]. These data-driven monitoring and analytics solutions with gateways enable brownfield machines to engage in data-driven solutions without extensive hardware improvements [15,91].

4.2. Edge-to-Cloud Communication Architectures

With large quantities of data being frequently generated by CNC systems, direct cloud transmission is not a viable option because of bandwidth and latency issues. Edge computing is one of the essential levels of development because it provides the ability to prepare data in the simplest way before sending it to the cloud [27,33,76]. Designs based on edge–cloud collaboration provide the opportunity to run local operations such as feature extraction, anomaly detection, and data compression, reducing the load on the network and shortening response times [27,34]. Other developments are multi-access edge computing (MEC) and task offloading systems, which allow the intelligent allocation of computing functions among edge nodes and cloud servers [32,34].

4.3. Industrial Communication Networks and Connectivity Technologies

In addition to protocol-level communication, the physical and network layers are significant in ensuring that the data delivery is reliable. Wired industrial Ethernet networks like EtherCAT, PROFINET, and Time-Sensitive Networking (TSN) are common in precision CNC applications due to their deterministic behavior and low latency [79,83]. Simultaneously, wireless networks, including Wi-Fi 6 and 5G, industrial IoT, are fast becoming a tool to facilitate adaptable manufacturing layouts and portable CNCs [22,32]. Interestingly, CNC monitoring based on 5G has enormous potential to provide smart industrial spaces with extraordinarily low latency and vast connectivity of devices [32,34]. However, wireless communication poses challenges with regard to reliability, cybersecurity, and electromagnetic interference, so robust network structure and resilience architectures must be paid attention to [88,92].

4.4. Cybersecurity and Data Integrity in CNC Communication Networks

With the increased interconnectedness of CNC machines, cybersecurity has become a significant issue. Communication networks may be attacked in the form of data tampering, unauthorized access, and denial-of-service, which may compromise the accuracy of machining and operational safety [84,87,88]. Secure communication structures may be applied to ensure the security of CNC data streams based on encryption, authentication, intrusion detection systems, and an anomaly-based scheme [84,92,93]. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of integrating cybersecurity methods into communication protocols and digital twin architectures directly, so that it is possible to proactively adapt to cyber threats as well as ensure operational resilience against emerging cyber threats [77,88].

Beyond the preservation of data confidentiality and integrity, cybersecurity weaknesses within cloud-connected CNC systems can precipitate tangible physical and operational repercussions [77,87,93]. Cyber-attacks directed at communication pathways, control signals, or monitoring data streams have the potential to engender unsafe machine operations, thereby causing tool breakage, excessive vibration, dimensional inaccuracies, or the production of defective components [88]. In more critical scenarios, the compromise of control or monitoring functions can lead to unanticipated operational interruptions, equipment degradation, or safety risks for personnel [77]. These cyber-physical vulnerabilities highlight the necessity for security protocols that are seamlessly integrated with real-time monitoring, anomaly detection, and fail-safe control methodologies within CNC communication frameworks.

5. Cloud–Edge–IoT Architectures for CNC Monitoring

5.1. Overview of Cloud-Based CNC Monitoring Architectures

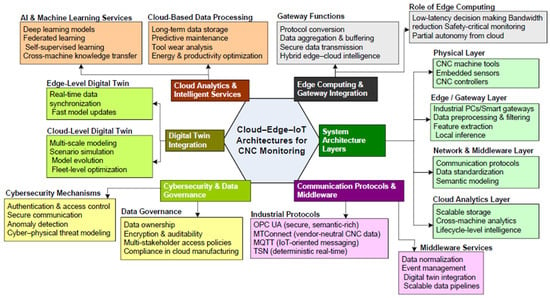

Cloud CNC monitoring architecture. Cloud-based systems offer central data storage and scalable analytics as well as cross-machine intelligence by linking machine tools to cloud computing environments through industrial communications systems. In contrast to single machine-level observations, cloud methods provide visible, rapid, long-term data storage and joint optimization of production lines and factories. In general, cloud-based CNC monitoring designs have a hierarchy of four layers: (i) the physical layer, comprising machine tools and sensors; (ii) the edge or gateway layer; (iii) the network and middleware layer; and (iv) the cloud analytics layer. This multifaceted paradigm is widely applicable to cloud manufacturing systems and digital twins due to its scalability and versatility [20,22,89]. According to recent studies, cloud-based CNC monitoring is not a simple form of data dumping, but a transition towards a service-centered, data-driven industrial setting [89,94,95]. Figure 6 is a taxonomy of cloud–edge IoT-based CNC monitoring, which offers an ordered literature review. The taxonomy classifies the existing research into architectural layers, edge and gateway integration, communication protocols and middleware, cloud analytics, digital twin integration, and cybersecurity and data governance concerns. This classification allows for a logical conversation about the most advanced CNC monitoring technologies.

Figure 6.

Taxonomy of cloud–edge–IoT architectures for CNC monitoring.

While cloud–edge–IoT architectures present significant advantages concerning scalability, analytical capabilities, and inter-device intelligence, their integration into industrial settings is contingent upon factors such as implementation expenses, organizational preparedness, and technological dependencies [89,95]. For small- and medium-sized manufacturers, the adoption of fully centralized cloud solutions can present financial and operational challenges, particularly concerning infrastructure investments, data management protocols, and reliance on external services. Consequently, phased adoption strategies, which commence with edge-level monitoring and progressively incorporate cloud-based analytics and digital twin services, can serve to reduce investment risk while facilitating the incremental development of both technical and organizational competencies. These staged deployment models, therefore, support a gradual digital transformation without jeopardizing production stability or operational independence.

5.2. Edge Computing and Gateway Integration

5.2.1. Role of Edge Computing in CNC Systems

Edge computing has become an essential facilitator of real-time CNC monitoring through the execution of data preprocessing, feature extraction, and early inference near the machine tool. This localization minimizes the latency of communication, reduces the bandwidth, and limits the reliance on a constant connection with the cloud. Industrial PCs, embedded controllers, or smart gateways typically implement edge nodes and connect to CNC controllers via OPC UA, MTConnect, or proprietary protocols [32,76,96]. These systems promote fast decision-making in safety-critical operations like chatter detection, tool breakage identification, and thermal drift compensation with the implementation of intelligence at the periphery [33,44].

5.2.2. Gateway Architectures and Functions

Gateways are used to communicate between CNC machines and cloud applications at a high level in order to provide interoperability and secure data transfer. They not only feature protocol conversion (as in fieldbus to OPC UA), but they are also capable of data aggregation and synchronization, secure data transmission, and fault-tolerant local buffering. The more recent architectures of gateways have been expanded to include lightweight machine learning models and digital twin synchronization tools to facilitate hybrid edge–cloud intelligence and enhance real-time CNC monitoring capabilities [25,34,75].

5.3. Communication Protocols and Middleware

5.3.1. Industrial Communication Protocols

Cloud-based CNC monitoring requires reliability in communication, for which myriad protocols are widely deployed to ensure compatibility and data sharing security. OPC UA also has standardized, semantic, and rich communication with inherent security capabilities [30,85], but MTConnect can stream CNC operation data in a vendor-neutral manner. MQTT offers lightweight publish–subscribe communication that is best suited to IoT scenarios [97], whereas Time-Sensitive Networking (TSN) offers deterministic, real-time communication of data, which is needed in high-precision machining [83]. Together, these standards enhance interoperability between different CNC machines and manufacturers, an important factor in brownfield manufacturing set-ups [81,90].

5.3.2. Middleware and Data Management

Middleware platforms perform important tasks, including data standardization, semantic modeling, and event management in distributed CNC systems. They offer scalable data pipelines, simple connectivity to digital twin frameworks, and effective communication with analytics services. A number of research works have indicated the importance of semantic data models and standardized information layers in the consistency of real CNC machines and their virtual counterparts [30,39,98].

5.4. Cloud Analytics and Intelligent Services

5.4.1. Cloud-Based Data Storage and Processing

Cloud solutions provide long-term storage for high-frequency CNC data, which can be analyzed historically, cross-learned between machines, and analyzed at the lifecycle level. Cloud analytics are especially effective for the analysis of tool wear tendencies, predictive maintenance, energy optimization, and production performance. Empirical studies have shown that cloud-based analytics regularly do better than local-only systems in identifying slow-trending degradation patterns and systemic anomalies [26,77,99].

5.4.2. AI and Machine Learning in the Cloud Layer

Deep learning, federated learning, and self-supervised AI models are other advanced models that are rapidly being deployed to cloud environments to meet their high computing requirements. Cloud-hosted models can be continuously retrained, share information between machines, and transfer their learning across machine environments. Recent studies have shown that there are great improvements in the accuracy of prediction and generalization when using cloud-based learning structures [37,100,101].

5.5. Digital Twin Integration Within Cloud–Edge Architectures

Digital twins are the smart middleware between physical CNC machines on the one hand and cloud analytics on the other. Cloud–edge architectures enable real-time synchronization, multi-scale modeling, and lifecycle management of CNC digital twins. On the edge, nodes process the importing of real-time data and model updates, whereas cloud platforms process model evolution, scenario simulation, and cross-machine optimization [33,102,103]. Some of the models demonstrate that the combination of cloud analytics and edge-level digital twin synchronization can significantly enhance resilience, scalability, and responsiveness in CNC monitoring systems [73,104,105].

5.6. Cybersecurity and Data Governance Considerations

Cloud-based CNC monitoring raises major issues for cybersecurity, such as data integrity, authentication, and access control. According to research, secure communication protocols, anomaly detection, and cyber-physical threat modeling are essential to guard CNC systems [84,87,88]. Simultaneously, robust data management approaches such as access control policies, encryption, and auditability play a significant role in industrial-level adoption, particularly in cloud manufacturing environments with numerous stakeholders [106,107,108].

6. Comparative Review of Existing Studies

In this section, the state-of-the-art research on cloud-based, edge-assisted, and digital twin-based condition monitoring and prognosis in CNC machine tools is critically and comparatively reviewed. Instead of duplicating research efforts independent of each other, the debate revolves around recurring architectural patterns, methodological tendencies, performance trade-offs, and gaps in the research. Comparison tables of techniques are presented in a structured form that demonstrates the similarities and differences between the techniques, which gives a consolidated view of the current work and further advances in the monitoring of intelligent CNCs.

6.1. Architectural Paradigms for CNC Condition Monitoring

Digital twins provide the intelligence layer that is the central component between physical CNC machines and cloud analytics. Cloud–edge solutions can synchronize CNC digital twins in real-time, model at scale, and manage their lifecycle. Early CNC monitoring systems were typically centralized around cloud architecture, with raw or pre-processed sensor data being transmitted to remote servers so that they could be analyzed and decisions could be made. Although these technologies offered scalable processing and long-term storage of data, they were often faced with several limitation issues, including latency, bandwidth limitations, and reduced responsiveness, which became more pronounced when machining at high speeds [22,27]. Recent works have indicated that there has been a very explicit transition to cloud–edge and fog–cloud hybrid configurations, where latency-sensitive applications, such as anomaly detection, chatter identification, and emergency shutdown, are executed at the edge, and computationally intensive applications, such as long-horizon prognosis, digital twin synchronization, and model retraining, are processed in the cloud [27,32,33]. This development in architecture indicates the growing demand for real-time intelligence, resiliency in the network, and heightened privacy of data within the monitoring ecosystems of CNCs. Table 2 presents a summary and comparison of cloud-only, edge–cloud and fog-based systems regarding latency, scalability, the distribution of computations, and their ability to be applied to CNC monitoring and prognosis.

Table 2.

Comparative summary of cloud–edge/fog–cloud architectures for CNC monitoring and prognosis.

Overall, the comparative analysis shows a clear architectural shift from centralized cloud-only monitoring systems to hybrid edge–cloud intelligence. This evolution is mainly driven by latency constraints, data privacy requirements, and the need for localized autonomy in safety-critical CNC operations. While cloud-centric approaches excel in fleet-level optimization and long-term analytics, edge-enabled architectures increasingly support real-time anomaly detection, adaptive control, and resilience against network disruptions. These findings suggest that future CNC monitoring systems are likely to use layered, hybrid architectures that strike a balance between scalable cloud analytics and real-time responsiveness.

6.2. Sensing Modalities and Data Fusion Strategies

The most frequently adopted sensing modalities covering the studied literature are vibration, spindle current, acoustic emission, temperature, and power consumption [12,91,118]. One of the recent work trends, though, is the development of multi-sensor fusion schemes, rather than a single sensor. The underlying cause of this change is the inherent limitations of individual signals in changing cutting conditions, as well as the tool work interactions with the piece. Fusion methods are more robust, diagnostically accurate, and flexible [40,119,120]. The recent literature highlights feature-level and decision-level fusion, commonly trained by convolutional neural networks, long-short-term memory networks, and hybrid physics-informed models [33,36,120]. Although these methods enhance the resilience and generalization of CNC condition monitoring, they also introduce other challenges, especially in sensor synchronization, data redundancy, and model interpretability. Table 3 gives a comparative overview of the studies on tool condition monitoring (TCM), wear, chatter, and anomaly detection.

Table 3.

Comparative summary of tool condition monitoring (TCM), wear, chatter, and anomaly detection studies.

In addition to machine learning-based tool wear and fault diagnosis models often suffering from dataset imbalance, controlled laboratory conditions, and limited cross-machine validation, which may introduce bias and restrict generalizability, many reviewed studies rely on limited experimental setups, short-duration trials, or small-scale simulations, especially in edge–cloud collaboration scenarios, despite reported performance improvements. These methodological constraints highlight the need for larger, more diverse datasets and long-term industrial validation to substantiate reported gains.

The comparative analysis further indicates a shift from using single sensors to multisensory fusion strategies. This change is driven by the need for more reliable performance across different cutting conditions and machine setups. While using multiple sensors improves diagnostic accuracy and generalization, it also introduces more complexity in synchronization, data management, and system maintenance. This creates a trade-off between performance and how easily the system can be scaled up for deployment.

6.3. Digital Twin-Driven Monitoring and Prognostics

Digital twin (DT) technology is no longer an inert virtual analog of a CNC machine, but an active, data-driven, and adaptive cyber-physical response to data [20,131]. DTs offer a two-way interaction between physical and virtual machines for condition monitoring, providing state estimates, fault detection, and what-if analysis [55,132]. Two notable modeling frameworks for digital twins (DT) are identified in a comparative study. The former are physics-based and hybrid DTs, that is, models that integrate kinematic, thermal, and dynamic models with sensor feedback to generate interpretable and extrapolative representations [55,133]. The second paradigm is data-driven DTs, which are based on machine learning models that are trained on past and current data sources [36,132]. Physics-based DTs are more interpretable and able to make extrapolations, but often need significant calibration and knowledge of the domain. On the other hand, data-driven DTs are scalable to large machine operation spaces but can be susceptible to model drift and lack transparency [131]. Table 4 contrasts digital twin applications in CNC monitoring on the basis of the components monitored and application orientation.

Table 4.

Digital-twin-driven monitoring, prediction, and compensation in CNC machining.

The literature reveals that issues with model fidelity, calibration effort, and lifecycle management continue to be major obstacles to widespread industrial adoption, highlighting the need for standardized validation and maintenance strategies. Comparative analysis of digital twin implementations indicates an increasing shift from static or offline models toward continuously synchronized, data-driven, and hybrid digital twins.

6.4. Prognostics, Remaining Useful Life (RUL), and Decision Support

One of the most common usages of cloud-based CNC monitoring systems is prognostic modeling, especially tool wear prediction and remaining usable life (RUL) estimation [46,119]. Deep learning and hybrid physics–data networks (long short-term memory (LSTM), gated recurrent units (GRUs), and physics-informed neural networks [35,36,120]) have largely supplanted traditional statistical and regression-based methods. These advanced models give more precision, flexibility to nonlinear machining dynamics, and more generalization to diverse operating conditions. The inculcation of prognostic outcomes into decision-making paradigms is one of the major differences between these studies. Some of the studies are mainly focused on the accuracy of the forecasts, whereas others have included prognostic data for adaptive control, maintenance scheduling, and energy optimization plans [27,77,99]. This juxtaposition exposes a fundamental research defect in prediction-focused studies and practical, closed-loop frameworks, in which prognostic information is instantly transformed into operational choices. Table 5 compares interoperability, platforms, and standards (facilitators of massive comparative adoption).

Table 5.

Interoperability, platforms, and standards (enablers for large-scale comparative adoption).

7. Applications and Case Studies of Cloud-Based CNC Monitoring and Digital Twins

This section summarizes and critically reviews the reported applications and industrial case studies of cloud-, edge-, and digital twin-enabled CNC monitoring systems. Unlike Section 6, which analyzed methodological frameworks, the current section discusses the implementation of these technologies in real or near-real production, what performance gains were achieved, and what limitations were not addressed.

7.1. Tool Condition Monitoring and Wear Prognostics

The most advanced and most frequently reported field of cloud-based CNC monitoring is tool condition monitoring (TCM). The applicability of multi-sensor data capture, edge analytics, and cloud-enabled learning models in detecting tool wear and predicting the remaining usable life (RUL) has been proven in a number of studies. In recent case studies, multimodal sensing methodologies were applied that comprised vibration, cutting force, audio emission, spindle current, and visual data. Transformer-based models and CNN-LSTM hybrids such as these were tested on industrial milling data and demonstrated better generalization to different cutting regimes in a cloud-based architecture [70,118,146,147]. TCM systems based on vision that can be deployed using on-machine cameras and deep convolutional networks have also proven to be promising in terms of their accuracy, but remain vulnerable to illumination variation, chip adhesion, and coolant interference [8,47]. TCM with digital twins is a breakthrough in the industry. With these methods, a simulated representation of the tool wear occurs alongside actual machining, thus permitting proactive instead of reactive maintenance measures [46,49,148,149]. In spite of the fact that simulation-augmented twins were more robust in sparse data settings, most of the reported implementations were semi-online, i.e., based on periodical cloud updates instead of real-time two-way synchronization. One crucial finding was that, unlike laboratory and pilot-scale validations, which showed good prediction accuracy (over 90 percent), few studies had extended industry validation over a variety of tools, machines, and materials. This shortcoming restricted the researchers’ ability to make sound conclusions regarding the scalability and soundness of the provided methodologies [139,140,150]. Table 6 gives a summary of case studies on cloud-based and digital twin-assisted tool condition monitoring, including sensing modalities, analytical models, deployment topologies, and reported performance results. This shows that there has been a dynamic change from single-sensor, offline analysis to multi-sensor, learning-fueled, and dynamically updated digital twin frameworks.

Table 6.

Cloud- and digital twin-based tool condition monitoring case studies.

7.2. Machining Accuracy, Thermal Error, and Geometric Deviation Control

Other common applications included the removal of thermal error, improvement of geometric accuracy, and the management of contour error. The use of cloud-based monitoring allowed long-term thermal and positional data to be consolidated on multiple devices, which led to more accurate error models. Experiments demonstrated that collaborative learning automated edge–cloud control systems were better than single-boundary controllers in offsetting temperature variations in spindles, ball screws, and machine frames [27,35,37,64]. Physics-based thermal models coupled with machine learning estimators supported by digital twins have delivered less-than-micrometer-scale accuracy in controlled conditions [36,65,152]. It is interesting to note that multi-scale digital twins have been implemented in five-axis CNC machines and gantry systems, where structural deformation, thermal expansion, and servo dynamics can be simultaneously simulated [38,55,103]. Nevertheless, these systems required thick sensor arrays and high-quality calibration, which made them more expensive and difficult to implement. One of the most significant findings was that most of the reported case studies were concerned with the optimization of single machines. It has also been mostly unexplored how learned compensation models can be cross-machine generalized and transferred to different machine setups [131,153]. The loss of machining accuracy due to heat and geometrical defects was still a significant issue with a high-precision CNC system. Recent studies have been based on digital twin-driven error modeling that merges physical knowledge and data-driven education on edge–cloud infrastructures. A summary of typical applications in thermal error compensation and dimensional accuracy increase is summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Digital twin-based machining accuracy and thermal error compensation applications.

7.3. Energy Consumption Monitoring and Sustainable Machining

CNC monitoring has become energy conscious in line with environmental and carbon-reduction objectives. Cloud systems provide a centralized approach to machine power usage, lessening power consumption and idleness, and allowing the benchmarking and optimization of entire lines of production. In multiple industrial case studies, it has been mentioned that energy sensors were integrated with cloud dashboards successfully and that they offered real-time input to the operators and planners [155,156,157,158]. Digital twin-driven energy models provide what-if analysis, which enables energy-optimal toolpath projection and federated optimization [99,159]. Unlike tool wear applications, energy monitoring systems are more scalable and cheaper, as are their sensors, making them attractive to SMEs and brownfield sites [15,27,37]. Nevertheless, their effects on the quality of products and on the lifespan of tools are often indirect and immeasurably small. In addition to quality and reliability, energy economy has also become a significant performance parameter in smart CNC machining. Monitoring systems based on cloud and virtual energy digital twins facilitate the possibility of analyzing and optimizing power consumption in real-time. Table 8 is a summary of the energy-related applications that have been reported in the recent literature.

Table 8.

Energy monitoring and sustainability-oriented CNC applications.

7.4. Fault Diagnosis and Predictive Maintenance of CNC Subsystems

Fault diagnosis solutions have been provided as cloud-based solutions, including faults in spindles, feed drives, bearings, and servo systems, utilizing anomaly detection and classification methods. Deep autoencoders, transfer learning, and federated learning have been demonstrated to be useful in early failure detection in a distributed CNC fleet [84,87,92,162]. Digital twin-based predictive maintenance models rely on deterioration models and operational data to predict failure modes and maintenance time [77,139,163]. Pilots working in various industries have also noted reduced unplanned downtime and maintenance expenses, especially in high-value machining centers [164,165]. However, the issue of cybersecurity arises due to the continuous flow of information between CNC machines and cloud servers. Other studies have provided physics-based intrusion detection and secure edge processing as potential solutions for mitigation [88,165]. An important finding was that the majority of fault diagnosis case studies had been component-based and did not contain system-wide health indicators that encompassed mechanical, electrical, and control properties [131,140]. The most developed industrial uses of CNC digital twins have been in fault detection and predictive maintenance. These solutions have contributed to reductions in unplanned downtime and the early detection of faults by integrating a degradation model, anomaly detection, and cloud analytics. Table 9 represents typical predictive maintenance case studies on CNC subsystems.

Table 9.

Fault diagnosis and predictive maintenance case studies in CNC systems.

7.5. Digital Twin-Driven Smart Manufacturing and Cloud CNC Platforms

In addition to discrete observational tasks, recent studies have reported comprehensive digital twin systems intended to facilitate clever CNC-based manufacturing systems. Such solutions build machine monitoring, production planning, quality, and maintenance planning into cloud–edge architectures [20,22,89,166]. Very high-profile case studies have shown the extent of these practices. These applications include the development of digital twins of adaptive clamping and fixturing systems based on clouds, computer-automated control of production lines [167,168], and edge-based autonomous decision-making in CNC systems [33,74].

Most implementations remain at the Technology Readiness Level (TRL) even though their concepts are conceptually powerful, and there is very limited evidence of sustained industrial adoption at scale. This also shows a vital disparity between laboratory testing and extended industrial use. One really serious problem is the lack of standardization and interoperability between suppliers, controllers, and cloud platforms. Whereas there is some initial momentum with the creation of guidelines such as ISO 23247-1:2021 [169], there is no broad acceptance and standardization. This gap is important to fill in the creation of scalable and vendor-agnostic digital twin ecosystems in CNC production.

Quantitative performance indicators like latency reduction, maintenance cost savings, and downtime avoidance are inconsistently reported across published industrial case studies, which makes cross-study benchmarking challenging and emphasizes the need for standardized evaluation metrics in actual CNC deployments.

Even though many lab and pilot studies have shown promising results, most cloud-based and digital twin-enabled CNC monitoring systems are still in the early stages of industrial use. Most reported applications are often limited to single machines, short-term tests, or controlled environments. There are few examples of long-term reliability, the ability to work across different machines, or integration into existing production workflows. These observations highlight a persistent gap between experimental results and widespread industrial use. This emphasizes the need for future research to focus on technology transfer, operational reliability, and cost-effectiveness in real-world manufacturing settings.

8. Performance Evaluation Metrics and Validation Approaches

The effectiveness, dependability, and manufacturing preparedness of cloud-based CNC condition monitoring and digital twin systems depend on performance assessment. In contrast to traditional machining studies, which tend to study discrete indications like the roughness of the surface or dimensional accuracy, presently, cloud–edge-enabled frameworks demand multidimensional measurement. Factors such as signal-level accuracy, model reliability, computational efficiency, scalability, and decision-support impact are all critical. As per the current literature, the absence of standard and detailed metrics of evaluation remains one of the major obstacles in the way of transforming research prototypes into production systems.

8.1. Signal-Level and Feature-Level Evaluation Metrics

On the simplest level, performance appraisal is initiated by the establishment of the quality and informativeness of received sensor inputs. Statistical and spectral indicators, like root mean square (RMS), kurtosis and skewness, crest factor, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and ratios of frequency band energies, are used in studies of vibration, acoustic emission, current, temperature, and vision data. These indicators are typically applied to evaluate signal preprocessing pipelines and feature extractors prior to combining with machine learning models or digital twin systems. A number of studies on tool wear and chatter detection have established that the combination of time–frequency features and adaptive filtering methods enhances fault separability [12,14,15,17]. Nevertheless, research studies have discovered that good signal characteristics do not always result in good decision-making, particularly when cutting conditions or machine settings vary. This challenge has prompted a change towards model-based analysis, in which the robustness of features to domains is considered directly.

8.2. Model Accuracy Metrics for Condition Monitoring and Prediction

Cloud-based CNC monitoring studies tend to assess prediction capability in terms of conventional machine learning metrics. Classification problems have a tendency to give accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1-score, but regression models are measured in MAE and RMSE. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) is a very important indicator of fault detection studies. RMSE and MAE are widely used as major measures in applications of RMSE and MAE, including tool wear estimation, remaining usable life (RUL), and thermal error compensation models [44,56,118,119]. Although deep learning could be more accurate than classical models, they tend to improve depending on the dataset, which casts doubts on their generalizability [14,17,170]. New studies are seeking to eliminate this challenge by incorporating cross-machine, cross-tool, and cross-material validation. These investigations recurrently show that models that are educated on a distinct machining system experience a high degree of degradation when utilized in a variety of environments [14,140,171]. It is essential to enhance reliability and applicability through standardized benchmarking data and domain-adaptive evaluation procedures.

8.3. Digital Twin Fidelity and Consistency Metrics

CNC systems based on digital twins must have evaluation criteria for model fidelity and exactness in synchronization. In contrast to data-driven methods, digital twins have to be tested based on their ability to recreate real-time physical behavior. The usual examination measures are prediction error between physical and virtual conditions, time error, consistency measures in comparing simulated and measured outputs, and matching dynamic reactions to problems such as thermal drift or spindle vibration. A number of studies have come up with formalized fidelity evaluation schemes wherein digital twins are always compared with live machining data to perform model drift assessment [20,55,139,172]. Hybrid physics-data digital twins do better than data-driven models in the long-term stability, although more modeling effort is required, and they also consume larger quantities of computer resources [131,132,140]. One of the main weaknesses highlighted by the literature is that no common validation criteria have been used, and thus, inconsistency in reporting occurs, and also, it is impossible to compare findings across investigations.

8.4. Computational Performance and Real-Time Constraints

Cloud and edge CNC monitoring systems have to satisfy high latency and throughput demands, particularly when real-time control is required, detecting anomalies, and adaptive compensation. The criteria of evaluation have also been established to be end-to-end system latency, edge vs. cloud processing time, model inference time, and data transfer overhead. When contrasting cloud-only architectures with edge–cloud hybrid systems, it is found that edge intelligence is indeed an effective method to dramatically decrease the response time to allow almost real-time monitoring and control [27,32,34,37]. It has trade-offs between computational efficiency and model complexity, particularly in deep learning and digital twin synchronization. Critical evaluations have shown that in most research, algorithmic accuracy has been prioritized at the expense of deployment ability, which encompasses hardware constraints, network performance, and scalability [77,81,140].

8.5. Reliability, Robustness, and Lifecycle Evaluation

In addition to instantaneous performance, there must be an analysis of a product over its entire equipment life cycle, including industrial use. False alarms and missed detection rates, stability when sensors fail or during loss of data, and erosion of the model over an extended period are all reliability metrics. Long-term studies have shown that machine models deteriorate over time and with tool changes or process variations; thus, the need exists to have adaptive and self-refining evaluation processes [46,49,139,173]. Continuous learning and synchronization of digital twins means that the system is more reliable in the long-term; however, this creates challenges with data governance and model version control.

9. Challenges, Open Issues, and Future Research Directions

Although great progress has been achieved in cloud-based condition monitoring, digital twins, and intelligent CNC machining systems, there are still a number of challenges, including technical, methodological, and practical difficulties, that have not been solved yet. A critical review of the literature shows that most of the reported solutions have proven to have great potential at the concept or laboratory level, but have significant hurdles to scale to be implementable at long-term industry levels. In this section, the most outstanding problems that have been experienced in the literature and research trends are unified, and the research paths that are necessary to further promote CNC monitoring systems to the required level of robustness, credibility, and industrial maturity are outlined.

9.1. Data Quality, Labeling, and Generalization

One of the basic constraints of CNC condition monitoring studies is the lack of high-quality, representative, well-labeled datasets taken under realistic conditions in the industry. Most tool wear, chatter, and fault diagnosis models have been trained on laboratory-scale experiments with controlled cutting parameters, which limit their use in complex and variable production environments [14,15,47,91,119,128]. In the literature that was reviewed in this article, there are several data-related problems that are continuously reported. First, the imbalance in classes between healthy and faulty operating states is used to create bias in model training and evaluation, and in most cases, results in optimistic estimates of accuracy that are not applicable in the real world [126,130,174]. Second, domain changes due to the change in tools, material changes, machine dynamics, and process drift lead to considerable worsening of model performance when used in different machining problems [71,170,174,175]. Third, labeling the stages of tool wear and faults is expensive and subjective, which creates difficulties in developing trustworthy ground truth datasets [56,127]. Taken together, these aspects reduce the validity and sustainability of CNC monitoring solutions that rely on data. Future studies should focus on self-supervised and weakly supervised learning methods to minimize the use of the expensive manual labeling [101,176], training materials, and high-quality cross-study comparisons. Obtaining multimodal data on a benchmark scale and obtained in various machining conditions would be of significant benefit [15,54,128,177]. Moreover, machining-sensitive domain adaptation and transfer learning methods are needed to deal with heterogeneity in tools, materials, and machine platforms, and to make them more robust and deployable [40,71,175,178].

9.2. Scalability and Real-Time Constraints

Although cloud-based architecture allows centralized analytics and the long-term storage of data, latency and bandwidth issues are significant challenges to the real-time monitoring of CNC and safety-critical control applications [27,32,33,34]. The literature is very clear that all cloud-based solutions find it difficult to process high-frequency sensor data, in the form of vibration, current, and acoustic emission data, without adversely affecting responsiveness [27,76]. Edge computing addresses these problems by providing the ability to process locally, but it creates new complexity and challenges for deployment in the system [32,33,76]. The most promising solution is the so-called hybrid cloud–edge framework, but there are no standard strategies so far to partition tasks, orchestrate them, and evaluate their performance within this framework [27,34]. The current literature tends to suggest case-based architecture with no clear guidelines on how to scale out more machines, production lines, or factories. Future studies must also aim to develop adaptive task-offloading algorithms specific to CNC cyber-physical systems to allow greater dynamically allocated computational workloads to the edge and cloud resources, depending on their latency, data criticality, and resource availability [34,44]. Also, it is necessary to develop lightweight AI models that are designed to operate on the edges to guarantee real-time functionality without surpassing hardware limitations [44,76,179]. The reference cloud–edge architectures that are specifically aimed at CNC systems would also contribute to interoperability, scalability, and uniform industrial performance [77,95,117].

9.3. Digital Twin Fidelity and Lifecycle Synchronization

Despite the shift to digital twins as part of intelligent CNC monitoring systems, issues of model fidelity, model synchronization, and model lifecycle evolution are still poorly understood. Numerous existing applications are based on semi-physical or data-driven models, which cannot be maintained accurately as machines age, receive maintenance, and are subjected to environmental variations [20,38,55,131,140]. The main constraints are the lack of mechanisms to constantly update the twins, the poor connectivity of the processes of physical degradation and virtual model degradation [46,132], and the high effort needed in the calibration and maintenance of the model at the industrial level [102]. The future of research promises a hybrid physics–data digital twin system, integrating mechanistic modeling with data-driven flexibility [36,46,132]. It is important to develop self-evolving, consistency-conscious digital twins that identify and rectify model drift to make long-term deployment possible [143,172]. Moreover, additional adherence to new standards, e.g., ISO 23247 and STEP-NC, could be used to help in interoperability and minimize barriers to implementation on heterogeneous CNC platforms [58,141,180].

9.4. Interoperability, Standards, and Legacy Integration