Abstract

This paper presents a human-centered, AI-driven framework for font design that reimagines typography generation as a collaborative process between humans and large language models (LLMs). Unlike conventional pixel- or vector-based approaches, our method introduces a Continuous Style Projector that maps visual features from a pre-trained ResNet encoder into the LLM’s latent space, enabling zero-shot style interpolation and fine-grained control of stroke and serif attributes. To model handwriting trajectories more effectively, we employ a Mixture Density Network (MDN) head, allowing the system to capture multi-modal stroke distributions beyond deterministic regression. Experimental results show that users can interactively explore, mix, and generate new typefaces in real time, making the system accessible for both experts and non-experts. The approach reduces reliance on commercial font licenses and supports a wide range of applications in education, design, and digital communication. Overall, this work demonstrates how LLM-based generative models can enhance creativity, personalization, and cultural expression in typography, contributing to the broader field of AI-assisted design.

1. Introduction

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into creative design practices is gradually transforming the relationship between human imagination and computational intelligence. Historically, creativity was considered a domain exclusive to human intuition and esthetic judgment. However, AI systems capable of analyzing, generating, and interpreting visual and conceptual forms are now co-shaping this creative process [1,2]. Typography, which bridges linguistic meaning and visual expression, stands at the intersection of language, emotion, and design [3]. As AI evolves from a tool of automation to a creative collaborator, typography provides a rich context for exploring how machine intelligence can enhance human creativity and elevate design expression. Recent developments in generative AI, particularly large language models (LLMs) and diffusion-based architectures, have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in generating both semantically and visually coherent artifacts [2,4,5]. These systems have been successfully applied in fields such as image synthesis, texture generation, and style transfer, allowing designers to explore new esthetic possibilities [1,2].

In typography, several models have achieved substantial progress, such as MX-Font [6], DeepSVG [7], and Diff-Font [8], which focus on font generation. However, most of these approaches are still primarily pixel-based, emphasizing visual fidelity and stylistic blending while paying limited attention to the human-centered, iterative, and interpretive aspects of typographic design. Typography, as both a communicative and esthetic medium, is deeply tied to cultural identity, perception, and emotion [3,9]. While traditional Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based [1] and diffusion-based models [2] effectively generate fonts, they often fail to address the reflective and experiential qualities of design practice.

This paper addresses this issue by reframing font generation as a human-centered, design-led process. Rather than treating font creation as a purely computational task, we employ a sequence-based modeling approach using large language models to represent glyphs as stroke contour coordinate sequences. To our knowledge, this is among the first attempts to introduce LLM-based sequence modeling into typography, providing a stroke-level generative framework that is not achievable with existing GAN- or diffusion-based methods. This framework enables designers to manipulate typographic features such as stroke curvature, weight, and rhythm, while maintaining interpretability and esthetic coherence. The method transforms AI from a mere generator of outcomes into a co-creative partner that supports exploration, reflection, and material understanding. By embedding style conditioning and interactive control into the generative process, our approach facilitates real-time creative iteration and user participation—an embodiment of human-centered design principles [10,11,12].

This study demonstrates that AI-driven systems can facilitate more accessible, personalized, and emotionally expressive typographic experiences. In summary, this research contributes to the emerging field of AI-driven design by positioning typography as a collaborative medium between human designers and intelligent systems. By integrating LLM-based sequence modeling with design thinking and participatory evaluation, this framework offers a novel approach to AI tools that enhance creativity, inclusivity, and esthetic engagement—advancing the dialog between computational intelligence and human expression in design.

2. Related Work

2.1. AI-Driven Creativity and Generative Design

The intersection of artificial intelligence and creativity has introduced a new paradigm in computational design, where algorithms are capable of autonomously generating esthetic and functional outputs. GANs and diffusion models have been widely recognized as key enablers of this transformation, enabling significant progress in visual synthesis, image translation, and stylistic exploration. These models learn complex feature distributions from large datasets, enabling the generation of novel visual content with minimal human intervention. Recent studies have further expanded the concept of AI as a creative collaborator, emphasizing augmentation rather than full automation [13,14,15]. This shift from viewing AI as a tool to seeing it as a partner aligns with the core principles of human-centered AI [10] and the emerging paradigm of co-creative design frameworks.

2.2. Human-Centered AI and Co-Creative Design Frameworks

While algorithmic sophistication has advanced rapidly, ensuring that AI systems align with human values, intentions, and creative judgment remains an ongoing challenge. Human-centered AI (HCAI) seeks to balance computational efficiency with usability, interpretability, and ethical responsibility [10]. Shneiderman [10] advocates for “reliable, safe, and trustworthy” AI systems that empower rather than replace human judgment, while Norman and Stappers [11] emphasize that the ultimate goal of technology in design is to extend human capability and foster creative self-expression.

In the context of design, the co-creative paradigm has emerged as a methodological bridge between design thinking and artificial intelligence. Studies in human–AI collaboration reveal that creativity is best fostered through iterative interaction and reflective dialog between human designers and intelligent systems [13,14]. Such systems are characterized by adaptability, feedback-driven evolution, and sensitivity to user intent. For example, Davis et al. [14] proposed a framework for computational co-creativity in generative art, suggesting that successful AI collaborators should support exploration, surprise, and mutual learning.

In creative industries, these principles are increasingly reflected in tools that combine user experience design (UXD) with machine learning feedback loops. Hassenzahl [12] highlights the affective dimension of interaction, suggesting that meaningful experiences arise not merely from efficiency but from emotional engagement and narrative coherence. Thus, integrating AI into creative workflows requires not only technical precision but also empathic and transparent design thinking—ensuring that intelligent systems remain interpretable, responsive, and emotionally resonant [10,11,12].

Recent work has begun to examine the integration of generative AI within human–design workflows, moving beyond automation toward co-creative partnerships. For example, Wang et al. [16] propose a structured Human–AI Co-Creative Design Process and show its impact on designers’ creative performance across experience levels, reflecting a broader shift toward understanding AI’s role in design cognition and collaboration. Similarly, Yu [17] explores AI’s role as both a co-creator and a design material, emphasizing its impact on ideation and evaluation stages of the design process and highlighting challenges and opportunities for AI to enhance creativity. Anasuri and Pappula [18] provide a broad overview of human–AI co-creation systems in design and art, identifying key design principles, interaction modalities, and evaluation approaches that characterize current practice.

Existing co-creative tools operate at image-level or prompt-level, while our work enables stroke-level, continuous, typographic structure modeling. Our model integrates LLM latent style tokens into a sequence-based generative pipeline, enabling controllable, interpretable, and procedural type design. We bridge symbolic reasoning (LLM) with esthetic stroke modeling—a novel conceptual shift in computational creativity. This strengthens the distinction between our contributions and prior work.

2.3. AI Applications in Typography and Visual Communication

MX-Font [6] introduced a multi-style model that disentangles content and style to produce new typefaces from limited samples. DeepSVG [7] proposed a hierarchical vector representation for scalable glyph generation, and Diff-Font [8] extended diffusion modeling to enable controllable typographic synthesis. Despite these advances, most AI-based typography research remains data-driven rather than design-driven, prioritizing accuracy, fidelity, and reconstruction quality over interpretability or esthetic exploration. Few studies have examined the designer’s cognitive process or their experiential interaction with AI tools. Lupton [3] and Bringhurst [9] remind us that typography is not merely a technical system of shapes but a cultural and emotional medium that encodes rhythm, proportion, and texture as forms of meaning. Bridging computational generation with human-centered design intent remains a critical challenge in this emerging intersection.

Recent developments offer promising directions for such integration. Experiments in interactive AI typography and co-creative vector manipulation demonstrate that combining generative models with real-time designer feedback can enhance both efficiency and expressiveness [13,14]. These findings resonate with the broader goals of human-centered AI—suggesting that future font design systems should not aim to replace human intuition, but to amplify it, enabling designers to explore esthetic boundaries through intelligent, interpretable, and emotionally attuned tools [10,11,12].

3. Methodology

This study adopts a design-led, human-centered research methodology, integrating computational modeling, creative practice, and user evaluation. The objective is not solely to improve technical performance in font generation, but to also explore how large language models (LLMs) can be meaningfully integrated into the creative process of typography. This approach aligns with the principles of Research through Design (RtD), where design is treated as both a process of inquiry and a means of knowledge production. Rather than reducing the task of font creation to a purely computational or generative task, this research focuses on fostering an iterative, co-creative process between humans and AI, emphasizing design as a form of exploration and reflection.

The methodology can be broken down into three complementary components:

- The conceptual framing of human–AI co-creation;

- The development of a sequence-based generation model aligned with designer cognition; and

- Evaluation through design practice and user feedback.

3.1. Conceptual Framework: Human–AI Co-Creation in Typeface Design

The foundation of this research is based on the human-AI co-creation paradigm, where both the designer and algorithm engage in an iterative partnership to generate, refine, and reflect on typographic ideas. This approach emphasizes the dialog between human intuition and machine inference, positioning AI not as a mere tool, but as a creative partner that contributes to expanding the design space and offering generative alternatives. Unlike traditional automated design pipelines, which focus primarily on predefined outputs, our model fosters a more exploratory, reflective process that encourages iteration.

In typography, expressive details—such as stroke rhythm, proportional balance, and emotional tone—are crucial for achieving not only esthetic coherence but also cultural and personal relevance. Therefore, co-creation is pivotal in typography, as it enables more responsive and dynamic design outcomes that allow for greater artistic freedom. This methodology aligns with the principles of Human-Centered AI (HCAI) [10], which advocate for systems that are reliable, safe, and enhance human agency, enabling designers to have a stronger role in shaping the design process.

Here, the LLM does not replace the designer but complements their creativity by offering stylistic variations and interpretive mappings that align computational outcomes with the designer’s esthetic goals. The process allows designers to influence aspects of the font’s structure, enabling fine-grained control over its typographic features such as stroke curvature and weight, all of which are essential to typography.

Instead of treating font generation as a static image synthesis task, we model it as a conditional sequence generation problem. Let be a sequence of contour coordinates representing a glyph. Our goal is to model the probability distribution , where is the content identity (character) and is the reference style. Our architecture consists of three key components:

- Style-Aware Latent Injector: A module that projects visual style features into the LLM’s continuous embedding space.

- Generative Decoder: An autoregressive Transformer that predicts the sequential evolution of glyph contours.

- Probabilistic Head: A Mixture Density Network (MDN) that outputs the statistical parameters of the next coordinate.

By using a sequence-based generation approach, this study reframes font creation not as a static image generation process but as a dynamic creative act. Instead of generating bitmap images or pixel-based outputs, glyphs are represented as stroke trajectories—mirroring the flow and motion of handwriting and calligraphy. This approach merges computational precision with the expressiveness inherent in human creativity, treating the generation process as a form of digital craftsmanship [3,9,12].

3.2. Network Architecture

3.2.1. Style-Aware Latent Injection and Initialization

To ensure robust style representation, we avoid training the style encoder from scratch. Instead, we initialize the style encoder with a ResNet-50 backbone pre-trained on a large-scale font classification task. Given a reference image , extracts a global feature vector . To enable smooth style interpolation, we introduce a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) projector that maps to the latent dimension of the LLM, yielding a continuous style token . This token is prepended to the input sequence

where represents the char of the generated font and represents the start token of the LLM-style input. Through the self-attention mechanism, serves as a global prompt, guiding the structural deformation (e.g., stroke weight, slope) for the entire sequence.

3.2.2. Mixture Density Networks (MDN) for Trajectory Modeling

Direct Coordinate Regression (MSE) often leads to over-smoothed glyphs as it predicts the average of all possible variations. To address this, we model the conditional probability of the next point as a mixture of Gaussian distributions. Specifically, each point in the sequence is represented as a displacement vector relative to the previous point, rather than an absolute position on the canvas. We chose relative coordinates for translation invariance and numerical stability. The output layer of our decoder predicts the parameters for a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM):

where is the number of mixture components. This allows the model to capture complex topological nuances, such as sharp corners and serifs, by selecting the most probable mode rather than averaging them.

3.3. Optimization Objectives

We employ a compound objective function to ensure geometric precision, adversarial realism, and stylistic fidelity. First of all, the LLM prediction is used to maximize the likelihood of the ground truth coordinates under the predicted GMM distribution:

To enhance the visual realism of the generated vectors, we employ a Dual-Discriminator framework. A differentiable rasterizer converts the generated sequence into an image, which is then critiqued by a visual discriminator . We use the Hinge GAN loss:

In aid to enforce strict adherence to the reference style, we minimize the distance between the generated and reference images in the deep feature space of the pre-trained ResNet:

High-frequency jitter in the generated splines is another key point in this work; to overcome this challenge, we penalize abrupt changes in the second-order derivatives of the coordinates:

The total loss is defined as

where represents the negative log-likelihood of the ground truth coordinates under the predicted GMM distribution, represents the visual realism of the generated vectors, indicates the distance between the generated and reference images in the deep feature space of the pre-trained ResNet, prevent high-frequency jitter in the generated splines, and represents the hyper parameters in experiments.

3.4. Sequence Modeling and Design Control Interface

During generation, designers can manipulate latent style vectors z that represent features such as stroke curvature, contrast, and serif structure, allowing parametric customization without model retraining.

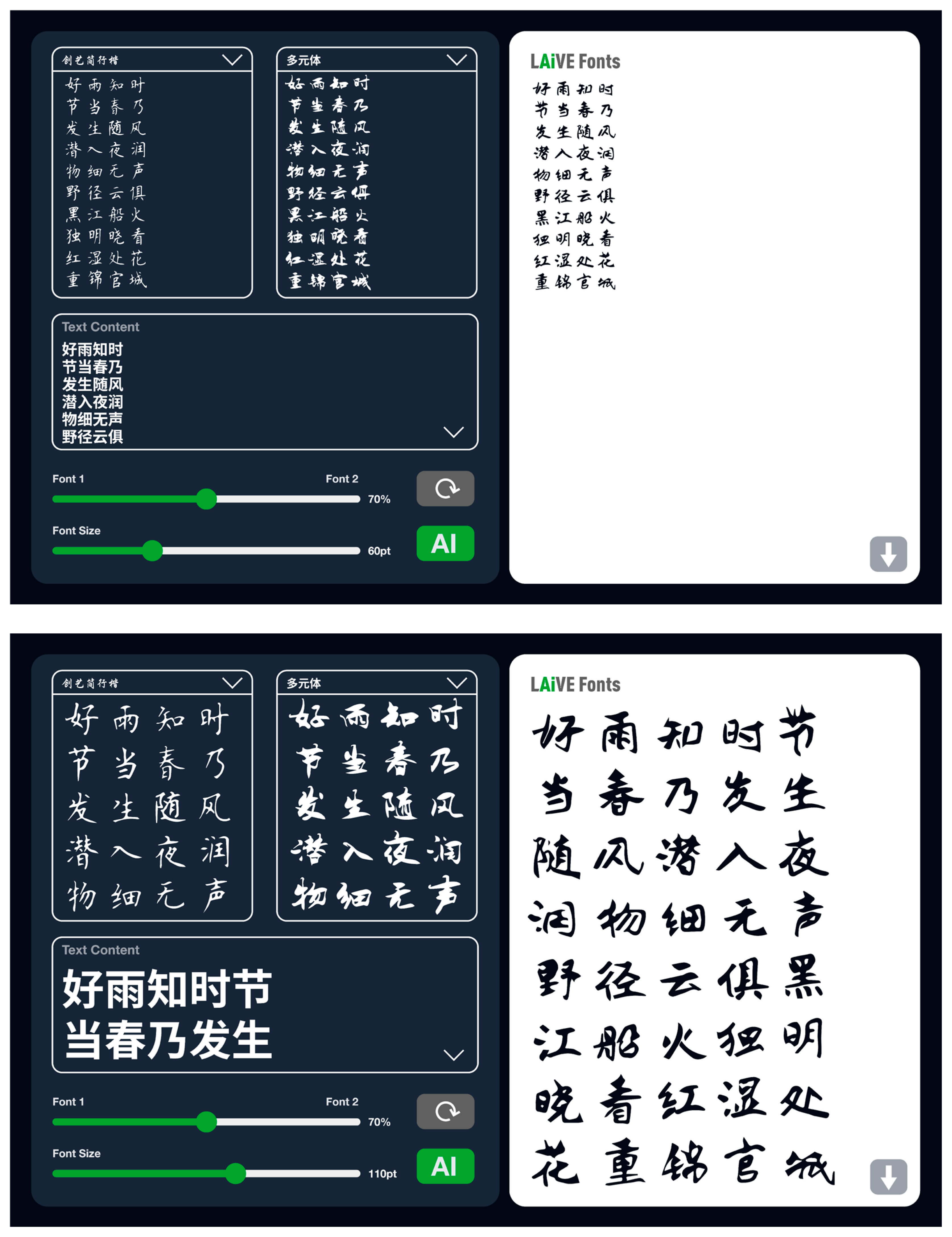

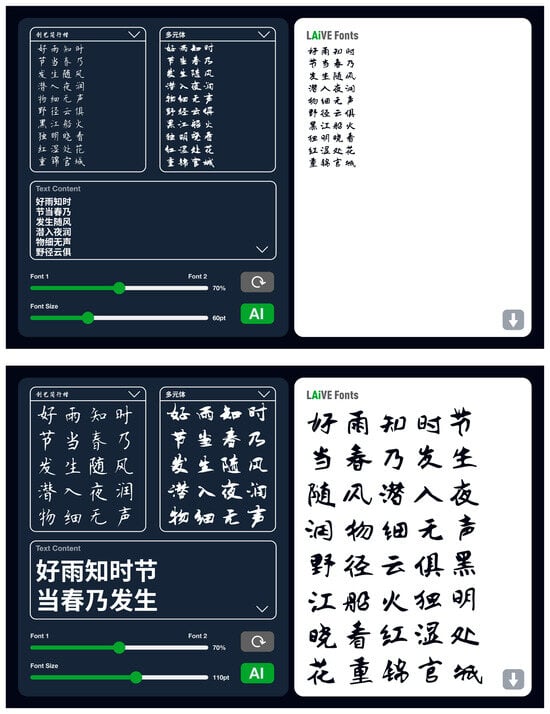

To enhance accessibility and creative control, a graphical co-creation interface was developed (see Figure 1). The interface allows users to:

Figure 1.

User interface of the co-creative font generation system, showing real-time parameter adjustment and glyph preview. In the image, users adjust the sliders for Font 1 and Font 2 to control font weight and size, while the AI generates corresponding typeface variations based on the input values. The content of the generated Chinese font is Happy Rain on a Spring Night, a classic poem by Du Fu, a Tang Dynasty poet of China. This poem depicts the revival of all things in the spring night rain scene and the longing for a vibrant life.

- Input seed glyphs or stylistic references: users can choose two existing fonts as inputs.

- Adjust parameters: users have control over font weight and size that influence the output.

- Generate multiple typographic variations in real-time: the system can adjust these parameters dynamically and generate new fonts based on the selected inputs.

- Provide evaluative feedback for iterative refinement.

In the interface shown in Figure 1, users can input the desired text content and adjust two fonts in terms of their weight and size. The AI then generates the output in real-time, offering users an interactive and responsive design experience. This method emphasizes reflective design principles as outlined by Norman [11], promoting a balance between analytical and intuitive engagement during the design process. The system offers designers a hybrid environment where computational intelligence enhances the natural workflow of typographic exploration, maintaining transparency and interpretability.

This approach emphasizes a human-centered design philosophy, ensuring that AI is an accessible tool for both expert and non-expert designers. By incorporating these interactive features, the system not only generates fonts based on stylistic constraints but also aligns the output with user intentions and emotional engagement [10,11,12].

3.5. Evaluation Through Design Practice and User Feedback

Evaluation in this study adopts a mixed-method design, combining quantitative performance assessment with qualitative design reflection and user experience evaluation. This dual perspective acknowledges that AI-driven design systems should be judged not only by computational accuracy but also by their creative affordances, usability, and emotional resonance [12,13].

- (a)

- Design Practice Evaluation

The system was tested through experimental design sessions involving five professional type designers and five design graduate students. Participants used the co-creation interface to produce new fonts under various stylistic conditions (e.g., serif, sans-serif, handwritten). Observations focused on interaction patterns—particularly how AI suggestions influenced ideation, iteration pace, and stylistic innovation [14,15].

- (b)

- Quantitative Analysis

Objective performance was evaluated using metrics adapted from generative modeling research: Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) for realism [19], Stroke Consistency (SC) for geometric coherence [6], and Diversity Score (DS) for stylistic variability [8]. These measures provided empirical grounding for assessing model fidelity and generative breadth. The FID metric evaluates how perceptually similar the generated typefaces are to real reference samples, while the Stroke Consistency (SC) ensures that the strokes of the generated glyphs maintain geometric stability. The Diversity Score (DS) quantifies the ability of the system to generate a variety of distinct and visually appealing typefaces from user input.

- (c)

- User Experience and Creativity Assessment

To assess user perception, a structured questionnaire was developed based on the Creativity Support Index (CSI) [20] and the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) [21]. Participants rated aspects such as creative stimulation, control, clarity, and emotional engagement. Results were analyzed through thematic coding and descriptive statistics, revealing patterns of trust, co-ownership, and perceived expressiveness. The study’s qualitative evaluation highlighted how users perceived the system as both a supportive and intuitive tool for creative exploration, allowing them to engage more deeply with the design process and produce fonts that resonated with their artistic intent.

The integration of subjective and objective evaluation reflects a broader movement toward design-inclusive AI evaluation [12], ensuring that system performance aligns with human-centered and creative goals. The findings suggest that the LLM-based framework not only improves typographic fidelity but also enhances the designer’s sense of authorship and exploration. Participants reported increased creative freedom through the system’s ability to offer new stylistic variations and adapt to their input in real-time, thus fostering an enriched sense of ownership over the generated designs.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents both quantitative and qualitative findings from the proposed LLM-based font generation system. Beyond measuring algorithmic performance, the results highlight how AI-driven co-creation reshapes both the workflow and the esthetic experience of typographic design. The discussion integrates computational evaluation with reflective analysis, following the principles of human-centered and design-led inquiry.

4.1. Datasets and Implementation Details

To address the ambiguity in previous definitions, we formally define the Mixed Cultural Typeface Set (MCT) used in this study. MCT is a multimodal dataset specifically constructed to learn universal stroke topologies across diverse writing systems. Unlike the datasets used in Diff-Font [8] and MX-Font [6] which primarily focus on pixel-level representation of homogenous scripts (e.g., Chinese and Korean), MCT emphasizes topological diversity. It contains 240,000 vector glyph sequences spanning 2 distinct writing systems: (1) Logographic System (Chinese): Comprising 1000 fonts with 2000 commonly used characters each, selected to cover varying structural complexities (from simple to dense strokes). (2) Alphabetical System (Latin): Comprising 50 fonts (including Serif, Sans-Serif, and Handwriting styles) with 52 upper/lower case letters and symbols. Strict ethical standards were applied during data collection. All glyphs are represented as variable-length sequences of Bézier control points, strictly curated from SIL Open Font License (OFL) sources to ensure reproducibility and copyright compliance.

All models were trained on a high-performance computing cluster equipped with 8 NVIDIA A100 (80 GB) GPUs. The transformer decoder consists of 24 layers with a hidden dimension of 512. The Style Projector is an MLP with 2 linear layers. AdamW optimizer is used with , and the weight decay is set to . The learning rate is initialized at with a cosine annealing schedule and a warm-up period of 2000 steps. Batch size is set to 256 per GPU. Our model was trained for 400 K steps until coverage. To ensure a fair comparison, the baselines (Diff-Font and GAN-based model) were retrained from scratch on our MCT dataset using their official open-source implementations, ensuring consistent training splits and convergence criteria.

A key advantage of our Continuous Style Projector is the capability for zero-shot style interpolation. As illustrated in Figure 1, we can synthesize novel hybrid styles by linearly interpolating the latent style tokens of two distinct source fonts (e.g., a Serif and a Sans-Serif) via . The results show that our model smoothly transitions the stroke weight and bracket curvature (geometry) in the vector space, confirming that the model has learned a continuous manifold of typographic features rather than merely memorizing discrete styles.

4.2. Evaluation

In this section, we present a comprehensive evaluation of our proposed LLM-based font generation method. The experiments aim to quantify the performance of the approach in comparison with state-of-the-art GAN- and diffusion-based models, and to examine the effects of key architectural and hyperparameter choices through ablation studies. Both objective metrics and subjective human evaluations are used to assess the quality, diversity, and stylistic consistency of the generated fonts. In addition, we analyze the scalability of the method by testing different model sizes and demonstrate how incorporating style parameters into the LLM influences the generation results.

4.2.1. Datasets

We evaluate our model using two commonly adopted datasets for font generation:

- Google Fonts Dataset

This dataset contains more than 1000 publicly available fonts that span a wide variety of styles, including serif, sans-serif, script, and decorative fonts. Each typeface includes a full character set (A–Z, a–z, digits, punctuation, etc.) in both regular and bold weights, offering rich stylistic diversity for training and evaluation.

- 2.

- Chinese Fonts Dataset

This dataset includes 500 Chinese typefaces, each covering thousands of characters. Owing to the structural complexity and high stroke density of Chinese characters, this dataset provides a challenging benchmark and enables evaluation of the model’s cross-lingual generalization capabilities.

Each dataset is randomly divided into 80% for training, 10% for validation, and 10% for testing.

4.2.2. Baseline Models

To establish a fair comparison, we evaluate our LLM-based method against several state-of-the-art approaches:

- MX-Font

A GAN-based multi-style font generation model designed to disentangle style and content, enabling few-shot typeface generation. MX-Font is known for producing stylistically consistent results with limited data.

- 2.

- TTF-GAN

A hybrid model that integrates GANs with diffusion-based refinement processes to improve resolution and visual detail. While capable of generating high-quality outputs, it relies heavily on pixel-level synthesis.

- 3.

- DeepFont

A deep convolutional neural network for font recognition and generation. Although earlier than recent models, it serves as a strong baseline representative of traditional convolutional approaches.

4.2.3. Evaluation Metrics

We employ a combination of objective metrics and subjective assessments:

- Fréchet Inception Distance (FID)

FID is widely used to measure the quality and diversity of generated images. Lower scores indicate that the generated fonts more closely match the real font distribution.

- 2.

- Structural Similarity Index (SSIM)

SSIM evaluates similarity in luminance, contrast, and structure between generated and ground truth glyphs, making it suitable for assessing fine structural fidelity.

- 3.

- Stroke Consistency (SC)

We introduce this custom metric to quantify the consistency of stroke patterns across glyphs. SC is computed based on the variance in stroke width, curvature, and alignment across characters within a font.

- 4.

- Diversity Score (DS)

DS measures the stylistic variability of generated results. It is computed from the variance of style-related parameters across font sets, with higher scores indicating more diverse outputs.

4.2.4. Quantitative Comparison with Baseline Models

Table 1 shows the performance of our LLM-based method compared to the baseline models on the Google Fonts and Chinese Fonts datasets. Our model consistently achieves better performance across all metrics, demonstrating its ability to generate fonts with higher fidelity and diversity.

Table 1.

Comparison of font generation results across font generation methods.

Our model achieves a significantly lower FID score, indicating that the generated fonts closely match the distribution of real fonts. Additionally, the higher SSIM and stroke consistency (SC) scores demonstrate the model’ s ability to preserve fine details and maintain consistency across glyphs. The diversity score (DS) also shows that our model generates a wider range of stylistically distinct fonts compared to baseline models.

4.2.5. Subjective User Study

While metrics like FID capture statistical distributions, they correlate imperfectly with human esthetic perception. To evaluate the practical utility and visual quality of the generated typefaces, we conducted a structured user study.

We recruited participants, stratified into two groups: Group A (Experts, ) consisting of professional graphic designers and typographers with at least 5 years of experience, and Group B (Novices, ) representing general users without formal design training. We adopted a blind evaluation protocol. Participants were presented with 50 randomly sampled font generation results (including outputs from our model, Diff-Font, and MX-Font) alongside the ground truth reference images. The model identities were anonymized to prevent bias.

Participants rated each sample on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Very Poor, 5 = Excellent) across three dimensions:

- Visual Fidelity: How well does the generated glyph preserve the structure and details of the reference style?

- Stylistic Coherence: Are the stroke weights and serifs consistent across different characters?

- Usability: Is the generated font legible and suitable for professional design applications?

The scores reported in Table 2 represent the mean ratings (μ) with standard deviations (σ). To ensure statistical significance, we performed paired t-tests between our model and the second-best baseline. The results indicate that our method is preferred with a significance level of . Notably, expert users rated our “Stylistic Coherence” 25% higher than the diffusion-based baseline, validating the effectiveness of our continuous style projector.

Table 2.

Subjective User Study Results (Mean ± Std). Best results are bolded.

These quantitative findings confirm the robustness and flexibility of the model, providing a solid foundation for future exploration into co-creative affordances and experiential design aspects.

4.3. Design Reflections: Human–AI Co-Creation in Practice

To understand how the system supports creative exploration, qualitative data were collected from 10 participants (5 professional type designers and 5 design graduate students). Each conducted a 90 min co-design session using the interactive interface. Through these sessions, three key themes emerged: (1) ideation through variation, (2) negotiation of authorship, and (3) reflective esthetic learning.

4.3.1. Ideation Through Variation

Participants described the system as “a collaborator that never runs out of ideas.” The ability to adjust latent style vectors in real-time facilitated rapid exploration—designers could visualize multiple structural alternatives in real-time, which traditionally would require hours of manual refinement. This aligns with findings by Davis et al. [15], who emphasized that AI’s role in co-creation is to expand the breadth of ideation rather than replace the depth of human creativity.

4.3.2. Negotiating Authorship and Control

A central theme of co-creation is the negotiation of authorship. While participants appreciated the system’s efficiency, they emphasized the importance of retaining creative control over the final typographic expression. One designer remarked, “It feels like the AI sketches ideas for me, but I decide which one speaks with my tone.” This observation resonates with theoretical perspectives by McCormack et al. [14] and Boden [17], who argue that genuine creative partnerships emerge when human intentionality remains central. The interpretability of stroke-level representations further supported the users’ sense of agency, in contrast to the “black-box” nature of many deep learning models [10].

4.3.3. Esthetic Learning and Reflective Practice

Participants also highlighted the esthetic learning benefits of the system. The real-time visualization of stroke structures enhanced their understanding of typographic principles like balance, contrast, and rhythm. Echoing Schön’s concept of reflection-in-action [22], designers engaged in a feedback loop where AI suggestions prompted re-evaluations of form and composition, deepening their esthetic understanding. This suggests that AI-driven systems can serve as pedagogical tools, nurturing esthetic literacy alongside creative productivity.

4.4. User Experience and Emotional Engagement

User perception was evaluated using the Creativity Support Index (CSI) [20] and User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) [21].

Quantitative results indicated high ratings in exploration (4.5/5), enjoyment (4.3/5), and perceived control (4.2/5), demonstrating a balanced sense of autonomy and guidance.

Qualitative responses revealed deeper emotional engagement:

- “The AI gives me a sense of flow—I lose track of time while experimenting.”

- “It feels like sharing a sketchbook with an intelligent assistant.”

These experiences resonate with Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of creative flow [23], suggesting that adaptive feedback and esthetic responsiveness foster immersive collaboration. Importantly, users perceived the AI as a creative amplifier, not a competitor—highlighting the success of human-centered design principles in maintaining psychological comfort and emotional resonance [10,11,12].

4.5. Discussion: Toward Human-Centered AI Typography

The results collectively demonstrate that integrating LLM-based modeling with human-centered design principles fosters a new paradigm of AI-augmented creativity in typography. Technically, the model achieves superior resolution, coherence, and stylistic diversity. Conceptually, it supports reflection, authorship, and affective engagement, reinforcing AI’s role as a creative collaborator rather than an autonomous generator [13,14,15,17].

From a theoretical standpoint, this study positions typography as a microcosm for studying AI’s role in creative authorship. By translating visual structure into symbolic sequences, the LLM bridges linguistic reasoning and esthetic form, echoing broader interdisciplinary goals in human-centered AI [10,11].

Future work may extend this framework toward interactive illustration, calligraphy, or motion typography, further examining how AI systems can engage with the embodied, emotional, and cultural dimensions of design practice [3,9,12].

5. Conclusions, Limitation and Future Work

This study presents a design-led, human-centered approach to AI-driven typography, showcasing how large language models (LLMs) can function as co-creative partners in the process of type design. By reimagining font generation as a sequence-based modeling problem, the research moves beyond traditional pixel-oriented methods, enabling greater control over stroke structure, stylistic variation, and expressive form [6,7,8].

The findings indicate that this approach not only improves technical metrics—such as fidelity, stroke consistency, and stylistic diversity—but also enhances designers’ creative engagement and reflective awareness. Through interactive co-creation, participants experienced the system as an intelligent collaborator, fostering ideation, supporting authorship, and promoting emotional flow [14,17,23]. These results affirm that when AI systems are designed with human-centered values, they can amplify rather than constrain creative agency, transforming the design process into a dynamic dialog between human intuition and computational intelligence [10,11,13].

From a broader perspective, this research contributes to the discourse on AI-augmented creativity by positioning typography as both a technical testbed and a conceptual metaphor for human–machine collaboration. The transformation of visual forms into linguistic stroke sequences demonstrates how symbolic reasoning and esthetic expression can converge, offering a new framework for cross-domain creative computation [4,10,12].

This work has several limitations. First, the model’s performance depends on large transformer architectures and GPU resources, which may limit accessibility in real-world design settings. Second, the system remains constrained by the composition of the training dataset; despite using open-license fonts, the current distribution still reflects stylistic and cultural imbalance, which may affect generalization to underrepresented scripts and typographic traditions.

Building on these findings, several directions emerge for further exploration:

- Deepening Co-Creative Intelligence: Future systems may integrate reinforcement learning from designer feedback (RLHF) and context-aware prompting, enhancing the AI’s ability to adapt dynamically to personal design preferences and cultural nuances [14,15]. This will involve: (1) collecting explicit and implicit interaction data during design sessions; (2) training preference models that adjust stroke behavior and style projection dynamically; and (3) developing real-time adaptation algorithms that update style vectors as the designer iterates. Implementing these mechanisms will allow the system to evolve into a continuously learning co-creative partner rather than a static generative tool.

- Cross-Cultural and Emotional Typography: Expanding the dataset to include diverse writing systems (Arabic, Devanagari, Hangul, etc.) and incorporating affective labeling could enable the exploration of emotionally expressive and culturally adaptive typefaces, bridging computational design with semiotics and communication theory [3,9,12]. This expansion will involve: (1) constructing balanced, open-license datasets across language families; (2) annotating fonts with affective labels (e.g., formal, playful, solemn) to support emotional typography modeling; and (3) evaluating cross-cultural usability through user studies involving multilingual designers. This will enable the exploration of emotionally expressive and culturally adaptive typefaces, bridging computational design with linguistic and cultural semantics.

- Design Education and AI Literacy: The co-creative interface could also serve as a valuable pedagogical tool in design education, promoting AI literacy and reflective learning. By making computational processes transparent and interpretable, such tools can cultivate a new generation of designers who are fluent in both algorithmic and esthetic reasoning [23]. Future work will (1) deploy the system in classroom settings to study how students develop hybrid algorithmic–esthetic reasoning; (2) design curriculum modules that expose students to interpretable machine creativity; and (3) evaluate learning outcomes through mixed-method studies (task performance, reflection logs, pre/post-competency surveys). These steps will help cultivate AI literacy and empower emerging designers to understand, critique, and co-create with generative models.

In summary, this work underscores that AI-driven creativity should not focus on automation but on augmentation. The integration of LLMs with design thinking principles opens new horizons for adaptive, interpretable, and emotionally resonant creative systems—where intelligence is not only artificial but also empathetic, reflective, and aligned with human creativity [10,11,13].

Through the convergence of AI, art, and human-centered design, the study advances a broader vision of computational co-creativity—one where machines do not simply imitate human imagination but extend its reach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.D.; methodology, Y.D. and M.G.; software, Y.D. and M.G.; validation, Y.D. and M.G.; formal analysis, Y.D. and M.G.; investigation, Y.D. and M.G.; resources, Y.D. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.D. and M.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.D.; visualization, Y.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of School of Architecture and Design, Beijing Jiaotong University on 1 January 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

All individuals acknowledged in this section have provided their consent to be acknowledged. The authors would like to acknowledge the use of GPT-5 for language polishing and refinement of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, E. Thinking with Type: A Critical Guide for Designers, Writers, Editors, and Students; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lian, Z.; Tang, Y. MX-Font: Multi-Style Coordinate Network for Few-Shot Typeface Generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; IEEE: New Orleans, LA, USA, 2022; pp. 14365–14374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlier, A.; Danelljan, M.; Alahi, A.; Van Gool, L. DeepSVG: A Hierarchical Generative Network for Vector Graphics Animation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 16351–16361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Ryu, J.; Joo, J.; Lee, S.; Ko, B. Diff-Font: Diffusion Model for Robust and High-Fidelity Font Generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; IEEE: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023; pp. 11902–11911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringhurst, R. The Elements of Typographic Style; Hartley & Marks: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shneiderman, B. Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence: Reliable, Safe & Trustworthy. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A.; Stappers, P.J. DesignX: Complex Sociotechnical Systems. She Ji J. Des. Econ. Innov. 2015, 1, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassenzahl, M. Experience Design: Technology for All the Right Reasons. In Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics; Morgan & Claypool: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, J.; Gifford, T.; Hutchings, P. Autonomy, Authenticity, Authorship and Intention in Computer Generated Art. In Computational Intelligence in Music, Sound, Art and Design; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadenhe, N.; Al Musleh, M.; Lompot, A. Human-AI Co-Design and Co-Creation: A Review of Emerging Approaches, Challenges, and Future Directions. Proc. AAAI Symp. Ser. 2025, 6, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M. Co-Creativity with AI: A Human-Centered Approach. Doctoral Dissertation, State University of New York, New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Kim, H.; Peng, J.; Wang, J. Exploring Creativity in Human–AI Co-Creation: A Comparative Study Across Design Experience. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 7, 1672735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.F. AI as a Co-Creator and a Design Material: Transforming the Design Process. Des. Stud. 2025, 97, 101303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasuri, S.; Pappula, K.K. Human-AI Co-Creation Systems in Design and Art. Int. J. AI Big Data Comput. Manag. Stud. 2024, 5, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heusel, M.; Ramsauer, H.; Unterthiner, T.; Nessler, B.; Hochreiter, S. GANs Trained by a Two Time-Scale Update Rule Converge to a Local Nash Equilibrium. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 6626–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, E.; Latulipe, C. Quantifying the creativity support of digital tools through the creativity support index. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. (TOCHI) 2014, 21, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugwitz, B.; Held, T.; Schrepp, M. Construction and Evaluation of a User Experience Questionnaire. In Human–Computer Interaction and Usability Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Happiness; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.