Abstract

E-learning content and participants in the learning process are usually annotated with metadata. Complicated metadata models are necessary for organizing personalized learning, so an ontological metadata representation is used. Since ontologies represent static knowledge, changes in e-learning systems and related description metadata require frequent changes to corresponding ontologies. Only a few professionals in the educational domain have some expertise in ontology development. So, maximal possible automation is of great importance for the development and maintenance of knowledge models, needed for intelligent e-learning environments. Ontology learning is an approach for automatic ontology development and evolution, affected significantly by recent advances in Artificial Intelligence and Language Models. The main objective of this study is to explore and analyze ontology learning approaches and techniques and the specifics of their use in an intelligent e-learning environment. It examines and summarizes recent scientific research to reveal the degree of development and the extent to which ontology learning is applied to support personalized tutoring. The paper outlines trends and challenges of ontology learning from textual e-learning content and comprehensively discusses ontology learning and its applications in intelligent e-learning. It also describes a use case concerning the implementation and practical usage of ontology learning.

1. Introduction

In recent years, with the penetration of computer-related information and communication technologies (ICT) and because of the COVID-19 pandemic, e-learning has become an essential form of education for a broad audience of students. Thus, e-learning is widely applied in schools, universities, and even business companies where lifelong learning is necessary, so it has already proven effective. With vast amounts of learning resources, such as online courses, videos, articles, podcasts, and e-books, learners can quickly become overwhelmed by the options available to them. Clear guidance is needed to indicate which sources are credible or relevant to their learning objectives. Many digital innovations have been involved in the educational context to do so, changing the educational paradigm to smart education in this manner [1,2]. The implementation of intelligent technologies and approaches has the potential to significantly improve the quality of educational services [3,4,5]. Intelligent education takes place in a smart e-learning environment that integrates emerging technologies (e.g., learning analytics, Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, ontologies, data mining, and cloud computing) and various innovative ICT tools [6,7,8].

In contemporary intelligent e-learning environments, it is essential to support personalized learning and, thus, enhance learning performance. The adoption of intelligent educational technologies and specialized software for processing learning-related data enables personalized learning [9,10,11]. The approaches to personalization include finding and recommending particular learning resources that meet students’ characteristics [12] or using criteria to select the most appropriate educational methods for a specific learning context [13] to improve knowledge acquisition. Another approach is the creation and provision of learning resources personalized according to students’ profiles, including prior knowledge and other learning-related features [14]. Ontologies can significantly help personalization and enhance e-learning.

An ontology is a formal, explicit description of a shared conceptualization of a domain. Usually, ontologies are built as a hierarchy of concepts and relationships and constraints, expressed by axioms in a machine-interpretable language to support semantic consistency, knowledge sharing, interoperability, and automated mathematical logic-based reasoning.

In education, ontologies can provide a structured model for organizing, representing, and sharing knowledge, defining the relationships among various concepts, disciplines, learning resources, and learner profiles, enabling a more organized, personalized, and efficient learning experience. Learning domain ontologies also have great potential to contribute to the content development of personalized educational resources [11]. In addition, ontologies can support semantic search and the discovery of learning content, as well as interoperability across educational systems. Thus, integrating ontology techniques can promote resource reuse and enhance their usage in intelligent e-learning systems.

Although innovative technologies enable improved educational services, updating the usual e-learning systems is challenging. Integrating ontology approaches into e-learning systems helps overcome information overhead and enables an easy-to-adapt, easily modified e-learning process, including intelligent functionality such as scalability, content reusability, and personalized learning [15]. Such information overload often requires students to exert extra cognitive load or mental effort while processing and navigating learning resources. In this context, ontologies can significantly reduce information overload by providing a structured semantic model for organizing, representing, and retrieving knowledge. Ontologies can help learners and educators manage complex information more efficiently and meaningfully by simplifying the organization of the adaptive and personalized learning and tutoring process. Ontologies are also valuable for supporting collaboration between resource developers, teachers in collaborative resource development, and learners in cooperative learning. They also help improve information retrieval for learners, including searching for external learning content or scientific news in the area of the learning domain. Teachers can also use ontologies to stimulate reasoning of available knowledge and, thus, a deep understanding of learning content.

Ontology development is difficult, time-consuming, and requires knowledge and engineering skills. Considerable efforts have been made to develop ontologies in many domains, such as Linguistics, Mathematics, Medicine, Chemistry, Agriculture, Geosciences, Education, and Computer science [16]. The ontologies created in almost all scientific fields can serve as initial domain ontologies in e-learning courses. Most of these ontologies are available online, but they are not suitable for direct usage in personalized learning. Some of these ontologies have been successfully used in e-learning for curriculum modeling and management, modeling tutoring strategies, learning domains, learners’ metadata, and e-learning services, but only after significant modifications. Well-developed general domain ontologies are not aligned with specific curricula, educational standards, or the specific needs of learners. They also lack information about difficulty, prerequisites, and pedagogical dependencies. And most of them contain a large amount of knowledge, unnecessary for every concrete course, that can lead to very big computational complexity, making them unusable in real-time applications. All these ontologies represent static knowledge, and real-time adaptation is needed before their usage. So, ontologies have great potential to improve learning and to dynamically adapt to frequent changes and dynamics in the e-learning domain, which is crucial for their use in practical intelligent educational environments.

Ontology development is difficult, time-consuming, and requires educational domain modeling, which is performed mainly by teachers or learning content developers. These specialists often are required to possess significant expertise in the knowledge engineering field, and they consider ontology development very challenging. Direct reuse of previously developed ontologies is not applicable, as each learning course has its own specifics. Moreover, some of the metadata used in personalized learning change dynamically during tutoring, and corresponding ontologies need to be updated accordingly. Therefore, in this field, it is essential to use ontology learning, which is one of the main factors in supporting the widespread adoption of ontologies in e-learning.

There is a wide variety of ontology learning approaches, methods, and techniques depending on the sources used and the requirements of the learned ontologies. This review analyses ontology learning approaches and techniques from the perspective of their usability in e-learning environments. The main aim is to outline the applicability of ontology learning approaches and techniques in e-learning and, thereby, facilitate the development and maintenance of educational ontologies. It presents the strengths and drawbacks of ontology learning approaches and techniques in the context of their usage for learning educational ontologies. Since the usual type of learning content is unstructured text, this article mainly discusses ontology learning from plain text. Thus, the research questions are as follows:

- •

- RQ1: For the development of the types of ontologies that are used in e-learning, which ontology learning techniques are valuable and useful?

- •

- RQ2: What are the significant specifics of ontology learning for usage in e-learning tasks in an educational context?

- •

- RQ3: How can a combination of Large Language Models (LLMs) and ontology learning techniques make ontology development and ontology evolution in e-learning easier and effective?

- •

- RQ4: For what types of tasks in e-learning are the (semi) automatically developed ontologies the most applicable or valuable?

- •

- RQ5: What are the main trends and challenges of ontology learning for the e-learning domain?

The current review explores the role of ontology learning techniques. It analyzes their specifics and uses in e-learning, both for supporting the ontology maintenance process and directly applying knowledge extraction results in the learning and tutoring process. The article sheds light on the methods for automating ontology development, including the impact of recent advances of Artificial Intelligence (AI), as LLMs on ontology learning, which can improve the effectiveness and quality of e-learning services within an intelligent educational environment. Ontology learning will make ontology development and evolution more effortless and more efficient, which is of great importance for the educational domain. Dynamic (semi-) automated ontology development and maintenance can help provide personalized education by adapting the resource authoring and delivery to match individual student skills and preferences. This review outlines and discusses trends and challenges of ontology learning from textual e-learning content, web content, and databases, and its possible impact on knowledge modeling for personalized e-learning.

2. Methodology

E-learning as an interdisciplinary field comprises four main subfields of knowledge that can be modeled ontologically: learning content, scientific domain, pedagogical domain, learner description domain (including personal data, psychology, etc.), and technology domain. Since e-learning content is mainly stored in textual sources and web documents, and learner data is stored in databases, the focus of research is primarily on methods and approaches for ontology learning from text, databases, and web documents. Ontology learning refers to the automation of ontology development. The field of ontology learning encompasses various technologies, depending on the resources utilized and the types of ontologies, such as unstructured, semi-structured, and non-structured resources, where the range of applicable techniques is extensive [17].

The research focuses on the possibilities for automating the development of tutoring-domain ontologies and the automated generation and maintenance of learner profile ontologies. Thus, this review aims to identify key trends and developments in ontology learning and to discuss the applicability of the most useful ontology learning approaches and methods aligning with the specifics of the learning content used and the targeted type of ontologies needed for personalization in education. The research methodology was designed to correspond to the review goal and the research questions. The research process consists of three steps:

- Formulating a search query;

- Data retrieval, selection, and pre-processing;

- Descriptive analysis and classification.

Firstly, the search was performed with the keyword “ontology learning” to gain an idea of scientific publications in this area. As a source of information, reputable scientific databases such as Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and IEEE are used. Also, recent, scientifically valuable surveys and research papers found on Google Scholar are included. The search was performed in the titles, keywords, and abstracts of scientific papers published over the last 20 years, from 2006 to 2025, in English only.

The number of publications on ontology learning is significant (Table 1); however, the goal of this research is not to provide an exhaustive review of all these works. Considering the specific knowledge stored in e-learning systems that can serve as resources for ontology learning, and the knowledge about ontology learning methods that work well with these resources, the authors initially aimed to analyze ontology learning approaches specialized for these resources and discuss possibilities to adapt these general methods to the educational context.

Table 1.

Number of results of search queries by years and scientific databases.

Then, to gain a more detailed picture of ontology learning in the educational context, the authors formulated three search queries to find original research on this topic: SQ1: “ontology learning” and e-learning, SQ2: “ontology learning” and education, and SQ3: “ontology learning” and education and LLMs. Although all results retrieved by SQ3 theoretically are included within the broader result set of SQ2, some SQ3-related results are challenging to locate or may be inaccessible when searching directly using SQ2. Therefore, SQ3 enables more reliable retrieval of relevant publications on ontology learning for education that include LLMs.

It was challenging to find relevant research on ontology learning in the educational domain due to two factors: most research in ontology learning is not related to this domain, and most research on ontologies in education focuses on ontology usage or manual ontology development. Ontology learning in the e-learning domain is a specific research area. For many research papers, it is difficult to determine whether they are truly relevant, as the abstracts often do not clearly explain whether any automation is used in the ontology development process. Therefore, in many cases, a scan reading of the entire publication is essential to classify a study precisely as ontology learning. This specificity makes the free availability of papers (i.e., open access) a significant factor for current research. For this reason, open access publications are noted in Table 1, which presents search results over scientific databases and digital libraries.

The search results in reputable scientific databases were few, and analysis of their titles and abstracts classified most of them as thematically irrelevant. Only 12 results seemed suitable. After a brief analysis of the publication’s content, the authors selected four papers from Scopus, three from WoS as relevant to SQ1 and SQ2, and one paper relevant to SQ3. Then, a comprehensive search was conducted across the digital library of Google Scholar, which returns many more results (Table 1). Titles, snippets, and abstracts of the first 1000 returned results were carefully analyzed. A selection technique based on citation counts was used to identify the highest-quality, thematically related papers. It included browsing and exploring most citations of scientifically valuable (with an impact factor score, impact rank, or a considerable number of citations) and thematically relevant papers.

From Google Scholar results, 42 were selected based on the analysis of titles and abstracts. After reviewing these publications, only eight papers that comprehensively discussed ontology learning applied to the development of ontologies in the e-learning field were found. The query SQ3 returned 236 results. Among them were very significant research papers and reviews on the application of LLMs to ontology learning, but none of them were directly related to the educational field. From these results, it can be inferred that the automation of ontology development in the e-learning area lacks sufficient research attention. The impact of advances in generative AI models for ontology learning, which support personalized education, was also not explored. As there were only a few studies on ontology learning in the e-learning field, the analysis performed and classification of ontology learning methods based on the types of resources used in education, and exploration of the impact of LLM advances on ontology learning methods using these resource types were the most significant parts of the research. The authors explored the possibilities of ontology learning techniques to support the development of educational ontologies and, specifically, the impact of LLM-based technologies on ontology learning methods suitable for automating ontology development in education.

3. Ontology Learning in the Context of the Educational Field

The usage of ontologies in e-learning and the applicability of ontology learning methods are closely related to the desired ontology properties. It is essential to classify ontologies based on the properties that are valuable for e-learning and ontology learning. Ontologies can be classified according to several dimensions, e.g., purpose, modeling domain, structure, and logical complexity.

3.1. Classifications of Ontologies in the e-Learning Domain

The classification of ontologies according to their modeling domain and purpose can be as follows: domain ontologies, application ontologies, global (upper) ontologies, and hybrid ontologies. Global ontologies usually contain well-known general terminology classification. Typically, developers use some of the available standardized upper ontologies (e.g., UFO DOLCE or WordNet) or parts of them when needed for general concept classification. Application ontologies that represent knowledge models specific to some applications require manual development by professionals. Ontology learning in the e-learning field is most frequently used for domain ontologies.

According to their structure and logical complexity, ontologies can be classified into the following categories: taxonomies, ontologies with specific type relations or properties, logically rich ontologies, and populated ontologies.

Particular methods exist for concept extraction, learning relations specific to the learning content type, or ontology population [18]. Therefore, suitable ontology learning techniques should be selected and used according to the target type of developed ontologies. Usage of ontologies in e-learning is task-specific. For example, domain-related taxonomies are frequently used for resource searching and personalized recommendations, whereas logically rich ontologies are most useful in learning and assessment.

In [19], Rahayu et al. classified ontologies based on their use in e-learning environments into five categories:

- •

- Ontologies modeling the curriculum (e.g., modeling the relationships among learning objects, learning goals, and the objectives of the study program);

- •

- Ontologies intended for data integration (e.g., to integrate knowledge in closely related domains);

- •

- Ontologies describing domains and learning activities;

- •

- Ontologies describing student profiles (as PAPI, LIP, or FOAF ontology);

- •

- Ontologies that are developed for usage in tasks related to resource or tool recommendations for personalized learning.

Based on the previously discussed classifications, we can classify ontologies, used in education, thematically as follows:

- •

- Tutoring domain ontologies (including simple taxonomies, modeling subdomains, complex relations, inter-domain relations, etc.);

- •

- Task-specific ontologies (for resource recommendation, for personalization, based on learning performance, learning disabilities, etc.);

- •

- Learner profile modeling ontologies (IMS LIP, IEEE PAPI, including behavioral data, learning preferences, disabilities, competences, motivations, etc.);

- •

- Learning content structure modeling ontologies (related to e-learning standards, as IMS LD, SCORM, IMS CP, or organizing other specific metadata categories for learning objects);

- •

- Pedagogical ontologies (for modeling teaching knowledge, including instructional methods, learning strategies and theories, pedagogical goals, teaching activities and roles, sequencing and instructional design logic, pedagogical constraints and dependencies, didactic models, learning theories, and educational principles, etc.).

This classification is essential for the current research, as some of the ontologies (as those modeling standards) represent clearly specified and rarely changed and standardized knowledge and should be well developed manually, but others, such as specific domain ontologies, include dynamically changed knowledge (most learning courses need periodical updates to their content, including terminology), and automating ontology maintenance is essential for course domain ontologies. It is also challenging to extract relationships among learning objects and learning goals automatically, storing them in task-specific ontologies. The best way to guarantee their correctness is to evaluate them manually. As learning domain knowledge and its sources are usually changed frequently, ontology learning will be the most useful for developing or evolving corresponding learning domain ontologies.

3.2. Analysis of Ontology Learning Techniques and Approaches and Their Possible Applications in the Educational Domain

Ontology learning is the automatic or semi-automatic process of developing an ontology by extracting information from various sources, including plain text, diagrams, databases, and social networks. Ontology learning research proposes techniques for constructing different types of ontologies and automating many ontology development steps to simplify the process of ontology building for experts or educators. Diverse classes of approaches are used, including statistical, data mining, logic-based, linguistic, machine learning, and deep learning approaches, among others. As the applicability of specific ontology learning methods closely relates to the available information sources, this review will analyze ontology learning methods from various types of learning content and learner information sources (such as textual e-learning content, diagrams, concept maps, databases, linked data), classify ontology learning techniques for essential types of information sources in the e-learning domain, and discuss its applicability for automating ontology development to support intelligent learning and tutoring.

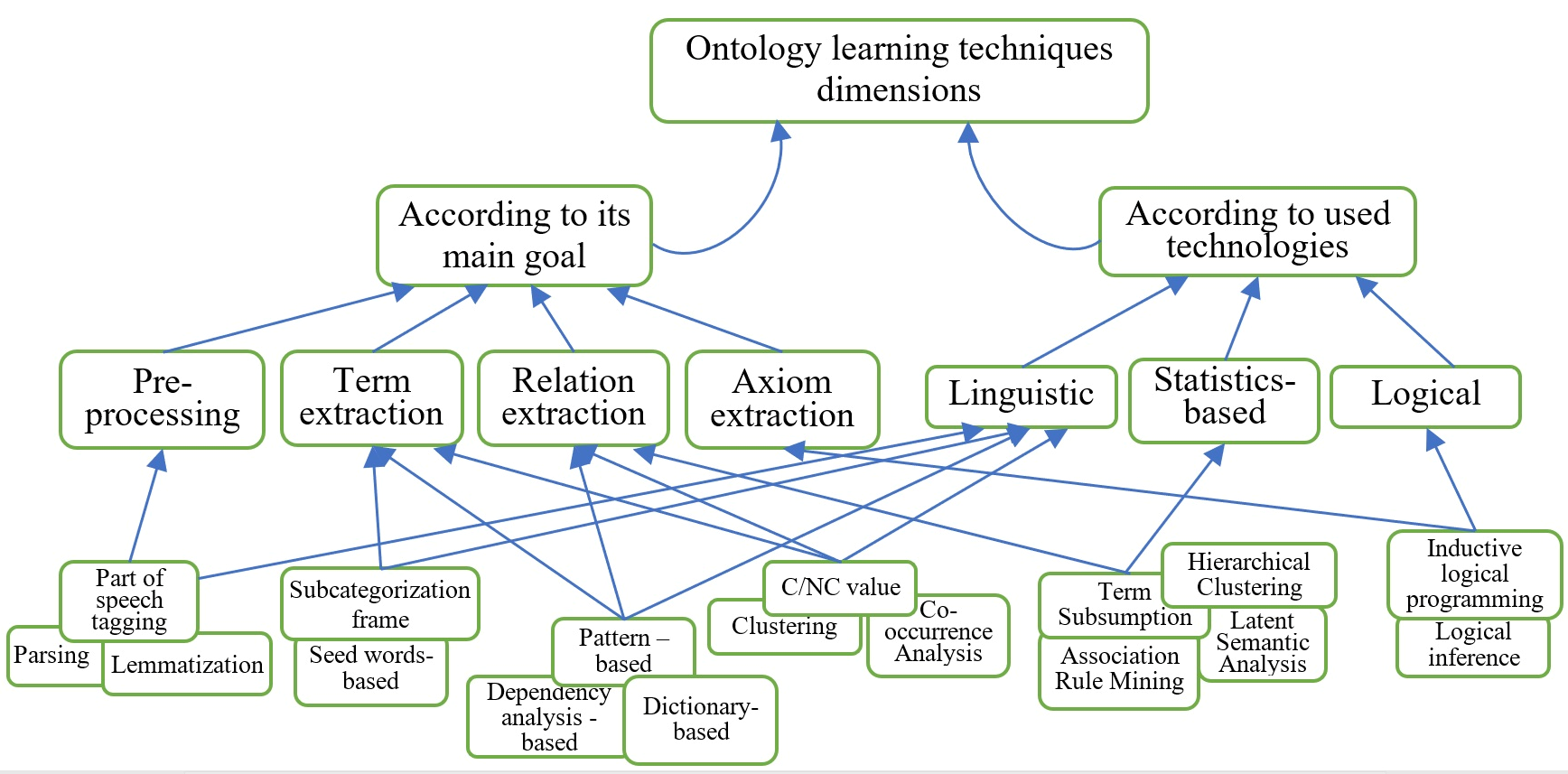

After examining the scientific literature on the topic, the authors developed a classification of ontology learning from text techniques, which can be useful in the e-learning domain. Figure 1 presents the authors’ two-dimensional classification of techniques for ontology learning from textual educational content (including pre-processing) based on ontology learning goals and the technologies used. Most of these techniques will be discussed in the following subsections.

Figure 1.

Classification of classical ontology learning from text techniques.

This paper first systematizes ontology learning techniques, useful for the development of ontologies for intelligent tutoring, in three main categories according to the used sources: learning from unstructured sources (as plain text), learning from semi-structured sources (as web documents, databases), and learning using structured sources (as UML diagrams, thesauruses, and other ontologies). As most learning content has a plain textual format, ontology learning from text is the most frequently used approach and is analyzed first, with learning objects’ structural and grammatical specifics in mind.

3.2.1. Techniques for Ontology Learning from Unstructured Text

Ontology learning [20] and enrichment [21] techniques from natural language text can be categorized into the following five main categories:

- •

- Natural language processing (NLP);

- •

- Machine learning;

- •

- Statistical techniques;

- •

- Data mining and information retrieval;

- •

- Logic-based.

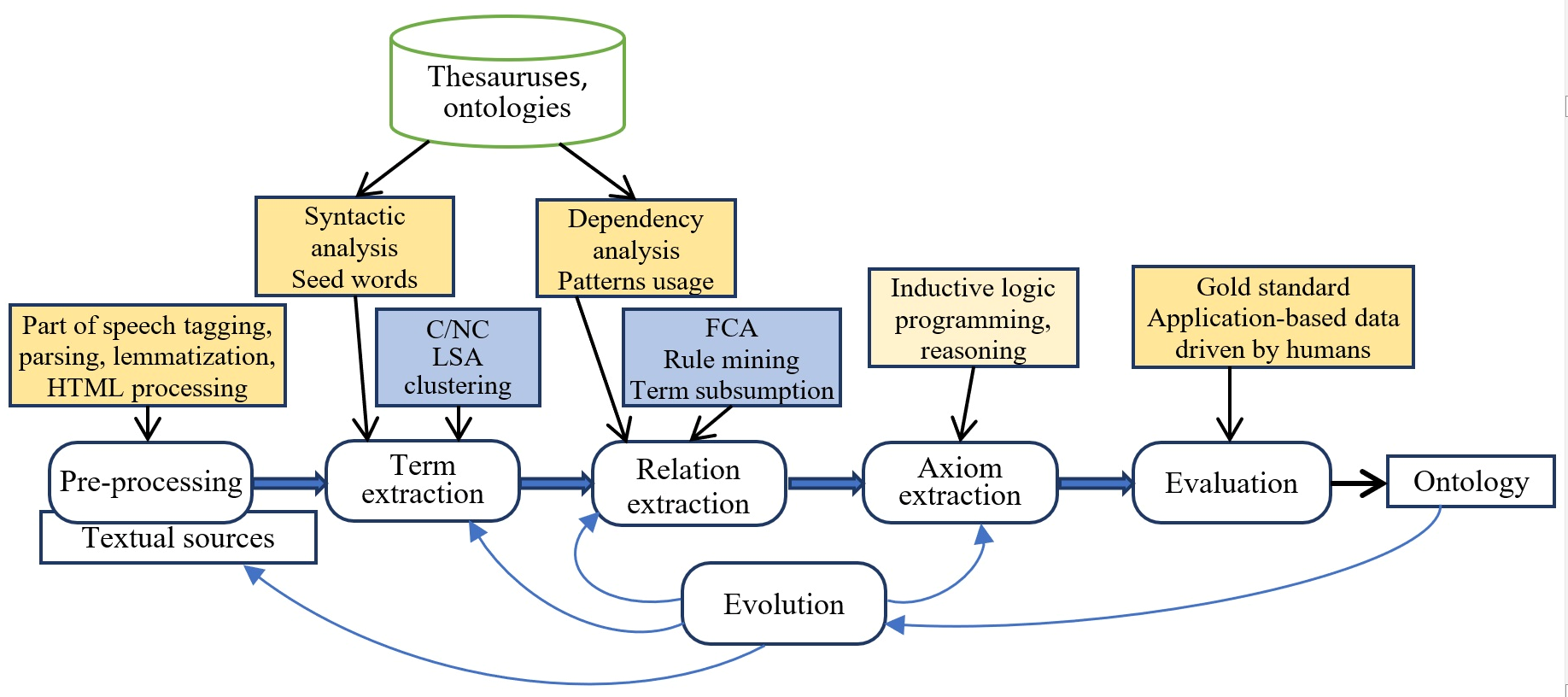

The authors visualize the step-by-step process of ontology learning from textual sources based on traditional approaches in Figure 2. The main steps are pre-processing, term extraction, concept formation, extraction of taxonomic and non-taxonomic relations, axiom extraction, and evaluation. Learning content is pre-processed using linguistic techniques such as parsing, lemmatization, and part-of-speech tagging. Syntactic parsing techniques are also used. Using linguistics or statistical methods helps to extract terms. Then, concepts are extracted using linguistic or statistical techniques, such as pattern-based techniques, C-/NC-value, and co-occurrence analysis. Subcategorization frames, latent semantic analysis (LSA), and clustering, or semantic lexicons, serve to extract taxonomic and non-taxonomic relations among concepts.

Figure 2.

The process of ontology learning from text.

NLP techniques and statistical approaches, including Dependency analysis, lexico-syntactic analysis, term subsumption, formal concept analysis (FCA), hierarchical clustering, and association rule mining (ARM), can be used at both the term/concept extraction and relationship extraction stages. Extracting axioms is mainly performed by reasoning or using Inductive Logical Programming (ILP).

Automatically developed ontologies usually contain terminological, linguistic, or logical errors or inconsistencies, and evaluation is an essential step in creating high-quality ontologies. Four main approaches (gold standard-based evaluation, application-based evaluation, data-driven evaluation, and human evaluation) and several evaluation measures (including precision, recall, and F-measure) are used to evaluate the integrity and quality of the developed ontology. The following subsections briefly discuss ontology learning technologies in the context of their application in the educational domain.

LLMs can perform most classical NLP tasks directly but without task-specific training. But LLMs do not replace all NLP techniques. They may generate plausible but incorrect facts, or LLM-based terminology extraction may lack deterministic precision. A discussion of the benefits and drawbacks of using LLMs for each of the following subtasks of ontology learning in the educational context is given below.

3.2.2. Ontology Learning from Textual e-Learning Content

There are two different tasks related to ontology learning: learning for developing new ontologies and learning for enriching and evolving previously developed ontologies.

Developing ontology from scratch is a complex, time-consuming, and labor-intensive task. Pre-existing seed ontologies are used frequently in the ontology learning process. There are also cases when dynamic changes in the existing ontology are needed. In e-learning, when the main aim is ontology enrichment, some of the above-mentioned steps can be applied independently of others. For example, if the targeted task is to compare the definition of a particular concept in the ontology and external textual resources, full pre-processing and lexical analysis are unnecessary. It is sufficient to identify the defined concept and its pattern, then extract properties and relations used in this definition and compare them with the definition in the ontological representation of the course.

When the main task is the development of a new ontology that describes learning content, the entire step-by-step ontology learning process should be followed (see Figure 2). However, in this case, ontology learning can be semiautomatic or interactive. In the e-learning domain, two contexts of interactive ontology learning exist: interacting with resource developers (teachers or experts) and interacting with learners. When the primary aim is to develop an ontology describing learning content, the developer can use ontology learning methods for a long time. In the case of ontology enrichment, some of the steps in Figure 2 can be applied independently of the others. However, it is necessary to manually verify the final results of ontology learning, as the quality of the domain ontology is essential in the learning domain. In particular, it is useful for some learners to develop small ontologies. This can stimulate comprehension and logical thinking. Ontology learning methods can provide guidance and suggestions to the learners during ontology development.

Pre-Processing of Textual e-Learning Content

Pre-processing textual sources using robust linguistic techniques is a prerequisite for ontology learning tasks [15]. Three main linguistic techniques are applied for pre-processing: part-of-speech tagging, parsing, and lemmatization. Preparing these steps is crucial for applying knowledge extraction techniques to natural language text. Usually, e-learning texts have a good structure, follow correct grammatical rules, and use restricted dictionaries. These facts can make pre-processing simpler and more efficient.

Considering a simple sentence structure of learning content, rule-based part-of-speech taggers, such as Brill Tagger [22], are effective pre-processing tools due to their better performance. Probabilistic taggers such as Tree Tagger [23] are rarely used. Parsing is a syntactic analysis of text aimed at identifying various dependencies between words in a sentence and representing them in a tree-based data structure called a parsing tree. GATE [24] and OpenNLP [25] are also good tools for pre-processing the learning content for ontology learning. Lemmatization is a linguistic pre-processing technique that brings words into their base form. The Stanford CoreNLP API [26] or WordNet-based Java Library [27] contribute to the lemmatization of textual data for ontology learning. LLMs can perform context-aware, semantic preprocessing that goes far beyond traditional rule-based methods.

Because they understand meaning, syntax, and world knowledge, LLMs can preprocess text based on context and language understanding, rather than rigid rules. LLMs can perform preprocessing tasks at high accuracy and, according to some researchers, often achieve higher F1 scores than those using classical pre-processing [28]. LLMs can generate shorter, clearer versions of text while preserving meaning. This is extremely useful before sentiment classification, topic modeling, semantic search, or information extraction. Also, LLMs can be used to extract topic-relevant nouns/phrases.

Traditional pre-processing techniques generally work well for e-learning content because of its precise semantic structure and correct grammar. Nevertheless, e-learning content can contain domain-specific elements such as formulas and definitions. Domain- or task-specific pre-processing is often better performed using LLMs. Another specific aspect of learning texts is the frequent usage of terminology in two or more natural languages. Extraction and recognition of multilingual terminology are essential for future steps in ontology learning, and, in this context, LLM-based techniques also are more useful. LLM-based pre-processing also can be used for text simplification and the removal of grammatical or terminological errors.

Linguistic Techniques for Knowledge Extraction

Linguistic techniques are used in many research projects to extract terms, concepts, and relations [16,17,19]. Syntactic structure analysis and subcategorization frames are useful for term extraction from well-structured texts, such as e-learning content. Dependency analysis and lexicon-syntactic patterns will also work well for relation extraction from e-learning content. Lexicons such as WordNet or other domain-specific web-based lexicons could also be used for concept extraction and relations, particularly for compound domain-specific terms. The extraction of domain-specific terms and concepts has improved by introducing seed words in the ontology learning pipeline.

The three main approaches used for relation extraction are based on Dependency analysis, patterns, and dictionaries. Dependency analysis uses parsing trees to extract relations between terms [29]. Dependency paths are used for finding relationship patterns [30]. They identify relations between two specific concepts by extracting the shortest path between those concepts in the parsing tree. Dependency analysis is an appropriate approach in e-learning because the extracted relations between concepts can be very useful in the learning process. The proposed educational content is good when it contains new, previously not shown, thought-provoking connections between concepts, and their explicit representation benefits learning. Research reveals that relationships between songs, extracted through Dependency analysis, can be successfully used for music recommendation [31]. Automatic extraction of dependencies between learning resources can be used to recommend external resources and support learning.

A pattern-based approach is rule-based, with rules often presented as lexical or syntactic patterns. A lexico-syntactic variant of this pattern-based approach is appropriate for extracting taxonomic or non-taxonomic relations to support ontology learning. Regular expressions are used to extract well-known domain-independent or domain-specific relations. The pattern-based approach is easily applicable in the e-learning domain, as many domain-dependent patterns are known in advance, so there is no need to extract them using complex algorithms. When a precise evaluation of content similarity is required, well-known lexico-syntactic patterns for this content domain are used. The main limitations of pattern-based approaches are related to the need to create specific patterns. This task is time-consuming and challenging to maintain as the domain evolves. It requires domain experts and NLP experts to collaborate and can fail when texts deviate from the expected linguistic structure. It also has poor scalability across domains or subdomains, and this makes pattern reuse difficult.

Dictionary-based approaches have high precision, but their application in general lexicons such as WordNet is very limited, as usually domain-specific terminologies are not included in these dictionaries or have significant differences in meaning. Some domains, such as medicine [32] or mathematics, have good semantic lexicons. They offer a wide range of predefined concepts and relations and can be used to extract terms, concepts, and taxonomic and non-taxonomic relations. The semantic organization of terms in the lexicons, as a set of similar words (synsets) and predefined associations such as hypernymy, meronymy, etc., makes them very useful for (semi-) automatic ontology learning and for direct use by learners. The usefulness of dictionary-based approaches depends heavily on the available dictionaries. Finding a helpful dictionary or different linguistic resources in international languages such as English or Russian is easy. However, the availability of such resources in many other languages is limited. Therefore, educational content and curricula usually rely heavily on the following components: standardized terminology, controlled vocabularies, official curriculum frameworks, and competency frameworks, all represented in various natural languages. Dictionary-based approaches can be beneficial for building semantic ontologies, including all the terminology above, with high accuracy, reducing ambiguity (e.g., “function” in math vs. programming), aligning learning materials to official standards, supporting automatic curriculum mapping, and improving search, recommendation, and adaptivity in e-learning systems. The authors found many good papers related to ontology learning, using dictionary-based approaches, but none of them are especially directed to the development of ontologies for education. In the authors’ opinion, most well-working dictionary-based ontology learning techniques are directly applicable for the development of tutoring domain ontologies.

Statistical Techniques for Ontology Learning and Their Application in the Educational Domain

Statistical techniques are like types of “black box” techniques. These techniques do not use concept semantics or relations between lexemes in the text, nor do they use semantic reasoning. Their main idea is that the co-occurrence of lexical units in a text often means that they are related or identical. Clustering, LSA, Association Rule Mining, Term Subsumption, Co-occurrence Analysis, and Contrastive Analysis are the most frequently used statistics-based ontology learning techniques. These techniques draw conclusions from statistical distributions of entity types across large amounts of previously selected texts (corpora) and do not consider underlying semantics. Such techniques require large, high-quality text corpora and are mainly used for term extraction, concept extraction, and taxonomic relation extraction. Frequently used statistical techniques for term/concept extraction are C/NC-value, Contrastive Analysis, Co-occurrence Analysis, LSA, and Clustering. In ontology learning, the algorithm LSA is used for concept extraction. The basic idea is that terms occurring together will be close in meaning.

The C/NC-value technique is particularly applicable to the extraction of multi-word terminology. It takes multi-word terms as input and returns a score for each of them [20]. This score combines two values—the C-value and the NC-value. The C-value tends to find a group of terms valid in the corpus. The NC-value considers the context of multi-word terms and tries to find longer strings that appear more frequently in the corpus [20]. The C/NC-value is a useful approach for term extraction in domains containing a significant amount of multi-word terms.

Contrastive analysis is a technique for filtering terms obtained through the term-extraction procedure. This technique uses two types of corpora: a relevant corpus (target domain) and an irrelevant corpus (contrastive domain). It also uses two measures of ontological learning—domain relevance and consensus. Such situations are occasional in the e-learning domain, and contrastive analysis is rarely used to develop learning ontologies in the e-learning domain.

Co-occurrence analysis is a concept-extraction technique that identifies lexical units frequently used together in texts. It applies to related-term extraction or to the identification implicit associations between various terms. Co-occurrences can appear on different levels: the phrase level, paragraph level, or document level. Various co-occurrence measures are used to evaluate the relationships between terms (e.g., Cosine Similarity, Dice Similarity, Mutual Information, etc.). Researchers report precision and recall of 60–70%. This approach can benefit learners in interactive ontology learning tasks. The ontology learning algorithm proposes related terms and asks learners about the type or correctness of the proposed relations.

LSA assumes that terms that occur together are close in meaning. LSA uses singular value decomposition on the term-document matrix as a mathematical technique. This approach is mainly used to find similar words and can be very useful for learners in interactive ontology learning to understand semantic relations in depth and find synonyms [33].

Statistical techniques for relation extraction include direct usage of statistical methods and machine-learning approaches. Term subsumption, FCA, Hierarchical Clustering, and ILP are statistics-based techniques used mainly for relation extraction during the ontology learning process. Term subsumption is used to extract hierarchical relations between terms. Hierarchical clustering is frequently applied to identify taxonomic relationships by grouping extracted terms into clusters based on similarity measures (e.g., Jaccard Similarity or Cosine Similarity). Two main strategies are used when building a cluster hierarchy—divisive clustering (top–down approach) and agglomerative clustering (bottom–up approach) [34].

Statistical methods rely mainly on term frequencies, co-occurrence, and distributional patterns. Usually, they do not capture comprehensive pedagogical meaning, e.g., prerequisite relationships between concepts, instructional intent, and cognitive difficulty levels. Educational materials use discipline-specific terminology and hierarchical concepts. Statistical techniques struggle to distinguish synonyms vs. related but different concepts. Ontologies frequently contain rich relations, and understanding complex dependencies is also very important in education, but statistical methods tend to detect only simple associations. Statistical methods often extract irrelevant terms or propose vague concept clusters or weak or spurious relations. Such an approach results in noisy ontologies that require extensive manual cleanup. Also, statistical methods cannot be easily adapted to evolving curricula. All this limits the usefulness of statistical methods for ontology development in adaptive educational systems.

Logic-Based Techniques for Ontology Learning in the Educational Domain

Logic-based techniques are mainly used to verify correctness and consistency and to extract relations and axioms. Finding contradictions in statements or relations between concepts can also be very useful for learners in the knowledge understanding process. The most frequently used logic-based techniques are inductive logic programming and logical inference [35].

Logical inferences are used mainly for extracting hidden relations from the existing ones in the ontology, using transitivity or inheritance rules. The main problem when using this method is extracting conflicting relations. Apart from ontology maintenance, logical inferences can be directly used in the tutoring process to support learners’ logical thinking and active participation in the learning process.

ILP is a machine learning discipline that derives hypotheses from background knowledge and a set of examples using logic programming. In inductive logic, programming rules are extracted from a collection of concepts and their relations. A methodology for automatically building domain ontology using Deep Learning techniques to identify taxonomic and semantic relations between concepts is proposed in [36]. The relation classification model is trained using Wikipedia and WordNet through the distant supervision technique. Learners can be encouraged to compare all the automatically extracted hypotheses to their own conclusions on the related topics and discuss similarities or differences.

Logic-based techniques can ensure high semantic precision and full explainability. They are excellent for hierarchy extraction, determining prerequisites based on ordering in syllabi, modules, or textbooks, and applying pedagogical theories. Their use is restricted due to the need for specific expert-defined rules.

LLM-based knowledge extraction is a new approach that combines elements of classical knowledge extraction techniques but operates at a qualitatively different level. It is a new knowledge extraction paradigm that combines classical statistical NLP, logic-, and linguistically rule-based knowledge extraction [37]. An LLM-based approach mainly relies on statistical AI, but being a logic-based approach, it can infer implicit relationships. It can also be used to integrate background knowledge and to directly restructure text into knowledge graphs or ontology triples (in JSON, RDF, or OWL formats) [38,39]. So, this new approach combines lexical, syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic cues.

Hybrid classical techniques combine linguistic, statistical, and logical approaches to ontology learning, applying them in previously defined or flexible orders. Since various methods are most useful at different levels of the ontology learning process, a hybrid approach is the most common technique for the entire ontology learning process. Some automatic hybrid ontology-building strategies start from an initial (possibly small) ontology and extend it later through text processing. Most frequently, term extraction and statistical models are combined. Term extraction methods are first used to identify the essential terms from learning resources. Then, statistical models such as Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) or co-occurrence analysis are applied to determine the importance of each term within the domain. The importance helps to identify which terms should be included as classes or concepts in the ontology.

NLP-based and machine learning techniques can also be successfully combined. NLP-based techniques can be used for dependency parsing and named entity recognition (NER) to identify key entities and their relationships in a sentence. Then, machine learning models (e.g., supervised or unsupervised learning, such as clustering or classification) can be used to categorize these entities into higher-level concepts or to determine relationships between them.

Hybrid approaches are the most useful for automatic ontology extension during learning content evolution. Examples of statistical and rule-based technique combinations include learning patterns using machine learning and then using the learned patterns as rules in the pattern-based approach. Ontology learning, supported by external semantic resources (seed words, thesauri, and other ontologies), is also a frequently used tool in e-learning, where most ontology learning tasks are of the ontology enrichment and evolution type.

Ontology learning from educational textual content aims to extract concepts, relations, learning objectives, prerequisites, skills, and pedagogical structures from learning resources (e.g., textbooks, syllabi, LMS content). Traditional techniques cannot extract missing (implicit) concepts, complex relations, and higher-level abstractions and struggles with synonyms/homonyms. LLM-based techniques can understand some context and conceptual meaning, extract fine-grained concepts, skills, and competencies, and identify synonyms, paraphrases, and pedagogical terminology. Some LLMs can also automatically convert text into structured knowledge. LLM-based techniques offer greater automation in relation extraction and ontology generation, but they cannot propose ontology validation, based on strict logical grounds.

3.2.3. Ontology Learning from Semi-Structured or Structured Sources

Ontology learning from semi-structured or structured sources refers to the automated or semi-automated extraction of concepts, relations, and hierarchical structures from structured data formats. Such structured sources mainly contain relational databases (tables, foreign keys), CSV files, spreadsheets, and existing knowledge bases (Wikidata, DBpedia). Semi-structured sources are XML, JSON, files, HTML pages (including tables, lists, infoboxes, and Web 2.0 sources), log files with formatting, Wikipedia infoboxes or template-based documents, and RDF datasets. Sources of most of listed types can contain valuable information for education.

Ontology learning from databases is a relatively new and prominent research area. Both relational and non-relational databases are appropriate. Some ontology learning approaches rely on the automatic translation of UML diagrams into ontology. There are well-working rules for such translation, but the logical complexity of the resulting ontology is highly restricted. Another ontology learning approach uses LOD. The process involves sending SPARQL queries to the LOD, analyzing the results, and, often, using them for further ontology development or updates. Due to the continuous enrichment of warehouses with open, linked data, this approach is gaining growing popularity. A significant problem in its use is the heterogeneity and dynamics of LOD, which make the possibilities for metadata extraction and corresponding ontology development challenging to predict.

Ontology Learning from Databases in the Educational Domain

Ontology learning from educational databases is an automated extraction of concepts, relationships, and hierarchies from (semi)structured data (e.g., tables, logs, learning analytics) to build or refine educational ontologies. Learning ontologies from databases involves establishing semantic correspondences between the data models and ontology-based knowledge models. In particular, when using relational databases in learning OWL ontologies, it is necessary to use the correspondences between the relational model and the ontology model, which are based on the relationships between the relational model and Descriptive Logic (DL).

Ontology learning from RDB includes two main tasks: constructing ontologies from RDB schema and extracting ontology instances from RDB data (ontology population) [40]. There are two main approaches to extracting the database schema for ontology building: transformation-based and mapping-based. They both work by applying rules. In [41], a set of rules is defined to analyze database components and convert them to corresponding ontology components. Researchers also define rules to explore and extract ontology elements from stored procedures, user-defined functions, views, multiple inheritance, and other database characteristics, treating these as constraints on tables and their columns. Some research explores relational and logical inference, as well as machine learning methods to extract instances from databases [42].

Many Learning Management Systems (LMSs) use relational databases to store data about learners. Ontology learning from databases can extract the semantics of the data stored in LMS databases and describe the learners’ performance, navigation, or communication. The resulting ontology can then be used to support personalized learning. The main difficulties in ontology learning from databases stem from the relatively poor explicit semantics implemented in the relational database model. Standardized rules are used to map the following:

- •

- Database tables onto OWL classes;

- •

- Simple attribute to DatatypeProperty;

- •

- Composition attribute to DatatypeProperty;

- •

- Multi-valued attribute to DatatypeProperty;

- •

- Primary key to DatatypeProperty;

- •

- Bi-directional relationship to ObjectProperty;

- •

- One-to-many relationships to OWL restrictions;

- •

- Subtype relations (IS-A) to OWL:subClassOf.

However, the semantics of relationships and entity names in databases are usually unclear. A database schema is a relatively simple, incomplete model of related practical domains, and it is usually an insufficient resource for extracting domain knowledge to develop a domain ontology. Methods for extracting knowledge from databases are more useful for ontology enrichment, evolution, and population.

When applied to educational databases, ontology learning techniques can extract concepts, relationships, constraints, and semantics from LMS databases, Student information systems, Learning analytics dashboards, Assessment systems, Curriculum repositories, Course catalogues, and Library or resource databases, and they can generate, enrich, or actualize learning domain ontologies, learner profile ontologies, or resource description ontologies. This is of great importance for dynamically updating ontologies in Intelligent Educational Systems (IESs) in response to ongoing changes in educational systems. In this way, data (raw or processed using learning analytics) are represented as structured data and are added to knowledge structures that support semantic search, personalized recommendations, adaptive learning, and teaching/learning decision support.

Ontology Learning from UML Documents and Its Usage in the Educational Domain

Instructional systems rely on structured representations of knowledge, learning content, or learner models. UML class diagrams, activity diagrams, or use-case diagrams are used to describe domain concepts, relationships, workflows, or processes in some e-learning systems. UML diagrams can also contain inheritance hierarchies, process steps, SCORM metadata, MS Learning Design metadata, etc.

Ontology learning from the UML approach uses well-defined rules to translate UML diagrams into ontology, based on semantic correspondences between the two models. The UML-to-OWL translation algorithm maps UML symbols to OWL identifiers and UML elements to OWL axioms [43]. Some of the essential transformation rules are the following:

- •

- A UML class is transformed into an OWL class;

- •

- A UML association or association class between two or more classes is transformed into an OWL class;

- •

- A UML attribute of a class is transformed to an OWL datatype property;

- •

- A UML role associated with a UML association and a UML class is transformed to an OWL object property between the two OWL classes;

- •

- A UML generalization set is transformed to a set of OWL class axioms (i.e., subClassOf type axioms);

- •

- The disjointness constraints are transformed to OWL DisjointClasses.

UML descriptions help represent the structure of learning resources in a simple graphical way. Standard rules work well for transforming a UML description into an OWL ontology. For example, such transformations perform a semantic description of Educational Adaptive Hypermedia [44]. A semantic description of the learning content structure resulting from translation enables the automation of the organization of the personalized learning process. The transformation of UML content diagrams of tutoring content developed by students can also be used for automated assessment of students’ knowledge.

Ontology learning from UML diagrams can be used to improve interoperability between systems by automating the creation of a formal semantic model (from a UML diagram to an ontology), enabling different e-learning systems to share data more effectively and exchange it. Ontologies, quickly generated from UML diagram can also allow for the structured storage of e-learning content, such as courses, assessments, student progress, etc. Such ontologies can also be used to recommend courses or assessments to students based on their prior knowledge or learning path. Students’ evaluations can also benefit from methods for creating ontologies from UML. Students can make UML diagrams during the assessment, which can be converted to ontologies, and evaluation can be automated by a comparison of these ontologies to domain ontologies, modeling the course knowledge. Despite the various possibilities for using ontology learning from UML in education, the authors found no research papers related to the extraction of educational ontologies from UML documents.

Ontology Learning from Web Sources and Its Applications in the Educational Domain

Web 2.0 semi-structured resources from social media (folksonomies, XML documents, social networks, web services, etc.) can be used for ontology learning. User-generated content, collaboration, tagging, social interaction, social networks, e-commerce-related data, and web services messages give essential information for personalized learning. Tags created by learners show how they conceptualize information, which can guide adaptive systems. Tags also include information about the learner’s interests and vocabulary. Learners’ connections, groups, or interactions also reveal their educational interests and capabilities. Folksonomy mining and text mining from Web 2.0 content, social network analysis, learning path extraction, and methods for analyzing learner behavior are specific techniques for information extraction from Web 2.0. Using thematic searches, the authors found some publications related to learning educational ontologies from Web 2.0, but these do not contain significant results.

E-learning 2.0-based educational systems are most frequently used in higher education. These systems are flexible regarding resource adoption, knowledge acquisition, and the use of cloud computing. A rich dataset for learners’ descriptions is stored and used in Web 2.0-based e-learning systems. In such systems, combining Web, Semantic Web, and social network-based technologies is easy. There are only a few studies on ontology learning from social web data [18,45], and none of them are related to e-learning. Some of these methods do not use HTML markup. These methods remove it and then process the extracted plain text. Thus, valuable information about the concepts and their relations discussed on webpages is discarded and not used. Other methods use HTML tags but do not exploit the entire document structure and paths. The HTML pages are handled by extracting semantics from titles, subtitles, bold, italic, underlined texts, tags, hyperlinks, lists, etc.; the related full text is also used for extracting knowledge. Digital textbooks, educational websites, MOOCs, forums, and open knowledge repositories are also web sources. They provide a rich base for extracting domain concepts, relationships, and pedagogical structures. So, web sources include various types of resources that can enrich several educational ontology types, and a wide variety of ontology learning techniques can be useful for automating ontology development.

Research [45] proposes Xhtml TREE Mining methods (called XTREEM) for ontology learning from web documents, exploiting the specific domain and language-independent semi-structure of webpages. Combining these methods, manual selection of high-quality e-learning content from the web, and some NLP-based techniques, can yield good results in automating ontology development and evolution. Other semi-structured resources used for ontology learning are Wikipedia, Webopedia, dictionaries, and thesauruses such as WordNet. Wikipedia is a rich source of knowledge for automatic processing. Many research projects on ontology extraction [46,47,48,49,50,51] use the Wikipedia corpus and its category system as a large-scale taxonomy. Wikipedia’s pages are also used to disambiguate terms. In [50], Tramontana and Verga propose a well-working algorithm for expanding domain ontologies using open semi-structured resources such as Wikipedia. Bhatt’s research suggests a dictionary-based ontology learning method for developing multilingual ontologies [51].

A well-defined structure of textual HTML documents can help with terminology and relation extraction. It enables the simultaneous application of methods for ontology learning from text and methods that exploit the structure and presentation of web documents.

Despite a wide variety of sources and possible techniques for automated development of educational ontologies using web sources, the authors found only two significant research studies in this area. One study [52] proposes a mechanism for the automatic construction of concept maps from online discussion forums, which can be used in an e-learning environment. Another paper [53] presents a semi-automatic domain ontology development process based on knowledge extraction from existing SCORM educational content found in online educational systems. These studies are relatively old and, in our view, not very significant. So, research on educational ontology learning from the web is limited.

Challenges in ontology learning from web sources are related to data and content quality (web data can be noisy, inconsistent, and unreliable, making it difficult to extract meaningful concepts and relationships); domain ambiguity (terms in the educational domain can have multiple meanings); a need for the integration of heterogeneous sources (e.g., academic papers, blogs, educational platforms); dynamic and evolving content; and semantic heterogeneity.

To summarize, ontology learning from web sources can provide educational systems with dynamic, context-aware, and personalized knowledge. By applying automatic extraction of concepts and relationships from vast web-based resources, ontologies can evolve more efficiently, offering tailored learning experiences and more accurate knowledge representation. However, developers must address challenges such as data quality, integration, and scalability to ensure the effective use of ontologies in e-learning systems.

Using the Linked Open Data (LOD) Cloud for the Development of Ontologies for Intelligent Tutoring

The LOD cloud (including simple RDF resources, dictionaries, and thesauri) contains a large amount of freely available knowledge, represented in machine-processable formats (RDF, RDFs, OWL, OBO, etc.) as thesauri or linked ontologies. This knowledge is easily usable as background knowledge by many ontology learning methods in support of knowledge extraction from texts or other types of learning objects to create more enriched ontologies. The knowledge contained in the LOD cloud spans almost all scientific domains and can support ontology learning in the context of every e-learning course. There are also suitable ontologies covering most scientific domains that can serve as initial variants for the development of course or learning content ontologies. By harnessing the power of linked data, ontologies can be created or dynamically managed to structure, organize, and enrich learning content. Thus, a more personalized, context-aware, and efficient learning experience is achieved, reducing information overload and helping students engage with the learning material in a meaningful way.

The main advantages of using LOD to automate the development of ontologies for e-learning are interoperability, access to rich knowledge, up-to-date data, and scalability (LOD datasets are designed to scale and handle large amounts of information). LOD can support ontology development by enhancing domain knowledge representation, by linking to open educational resources, linking with pedagogical data in LOD, dynamically pulling in related articles, videos, or exercises from LOD datasets to provide additional learning support, and linking to sources like Linked Data for Education, which could offer frameworks for assessment models, etc.

The most relevant LOD datasets for education and tutoring systems are DBpedia, Wikidata, YAGO, Open Educational Data Repositories, Competency, and Skills Ontologies Linked as LOD. DBpedia provides concept definitions, type hierarchies, semantic relations (e.g., part-of, subclass, relatedTo), and entity links to other datasets, which are very useful for building domain ontologies in almost all areas. Wikidata is a rich, human-curated knowledge graph comprising multilingual labels, well-structured statements, and fine-grained educational domain concepts. Open Educational Data Repositories contain education-focused datasets, OpenCourseWare data, Curriculum vocabularies, LODE (LOD for Education), and BabelNet (multilingual lexical and semantic resource). All these datasets and vocabularies can be very useful for the rapid development of educational ontologies, but the authors could not find serious research on educational ontology learning based on the LOD cloud.

Challenges in using LOD for the development of e-learning ontologies are data quality and consistency (not all LODsets are of the same quality). Some datasets may have incomplete or inconsistent data, integration complexity, and dynamic, evolving data. This is due to the LOD data changing over time, requiring constant updates and maintenance of the ontology to ensure consistency.

Ontology Reuse for the Development of Ontologies for Intelligent Tutoring

As the development of ontologies from scratch is difficult, labor-intensive, and time-consuming, and some previously developed ontologies can be found in almost every learning domain, finding and using appropriate ontologies is essential for easier ontology development. Search engines can help in finding suitable initial versions of learning domain ontologies, and ontology learning can support its primary adaptation. SPARQL queries are also useful solutions for extracting knowledge from previously developed ontologies, downloaded from the Internet, or created in other courses for intelligent e-learning. The facts obtained from these queries can support ontology extension, evolution, or evaluation.

Ontology mapping, merging, or partitioning can also support the development of educational domain ontologies using previously developed ontologies. For example, the ontology model for e-learning activities and actions can be mapped to the terminological domain ontology to define essential relationships between course terminology and learning activities.

Usually, ontology reuse in Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITSs) involves ontology maintenance and is performed in the following steps: identify relevant existing ontologies; analyze the compatibility of existing ontologies with the ITS’s requirements; adapt or extend existing ontologies; and evaluate and test the resulting ontology. Ontology learning is used mainly in the extension phase. Some well-known ontologies that could be reused or adapted for ITS are the IEEE Learning Object Metadata (LOM) Ontology [54], useful for describing learning materials, resources, and metadata, and the Competency Ontology (COMP) [55], useful for competencies modeling and skills development in students.

Ontology reuse is a powerful method for automating the development of e-learning ontologies. By leveraging existing ontologies from domains such as pedagogy, student modeling, and domain knowledge, ITS developers can create more robust, scalable, and efficient systems. However, careful adaptation and integration are necessary to ensure the ontologies meet the specific requirements of the ITS and remain flexible enough to accommodate evolving educational practices.

Challenges in ontology reuse for ITSs include domain-specific variability, integration issues (combining multiple ontologies from different domains can lead to conflicts or redundancies), and scalability (some ontologies might not scale well when dealing with large, complex educational environments or massive amounts of student data).

Using LLMs for Automating Learning Domain Ontology Development

LLMs can assist in almost all steps of ontology learning from e-learning content, including Concept Extraction (automatically identifying and extracting key concepts and terms from e-learning content) and Relation Extraction (discovering relationships between concepts, identifying hierarchical, associative, and dependency relationships, etc.). LLMs can also understand and process natural languages. This capability can ensure the extraction of definitions and descriptions of concepts directly from the text, enabling the understanding of terms in the e-learning domain and supporting automated semantic modeling. LLMs can also synthesize information from multiple sources to identify overarching themes and concepts or to identify differences in the meaning of closely related terms. LLMs can also be used to classify and cluster educational content into relevant categories or topics, thereby proposing suitable texts for specific ontology learning tasks. For tasks such as generating semantic annotations for educational content, LLMs can also be beneficial. These annotations link terms, concepts and their definitions, interrelationships, and contextual uses, thus enriching the ontology with semantic layers. Additionally, LLMs can propose related terms, synonyms, or alternative terms, considering the context, which can supplement the ontology.

Using LLMs for ontology learning in the context of e-learning is a promising approach, thanks to leveraging advanced NLP capabilities, which can significantly improve the efficiency and accuracy of ontology building. Thus, LLMs can automate the extraction of concepts, relationships, and knowledge from large sets of unstructured educational data, making them highly valuable for the e-learning domain. The limitations of LLM-based techniques are lower transparency, harder-to-justify decisions, and specific needs in interaction (prompt design, structured extraction formats).

3.3. Evaluation of Learned Ontologies in the e-Learning Domain

Automatically developed ontologies usually do not accurately represent all the knowledge from the sources used for ontology learning. They may contain terminological, linguistic, or logical errors or inconsistencies, so evaluation is essential for the development of high-quality ontologies. There are four main approaches to evaluating learned ontologies: gold standard-based, application-based, data-driven, and human evaluation. Human evaluation and the gold standard are used frequently in e-learning. Gold standard-based evaluation is applicable, as complete ontologies have recently been developed across many fields, and parts of these ontologies are used to evaluate the quality of ontologies learned from learning resources.

Ontology evaluation tasks can have two main goals: examining an ontology based on its characteristics (white box evaluation) and measuring its overall performance on a specific task (black box or task-based evaluation). White box evaluation focuses on two directions. The first is empirically evaluating how many (of all) components are learned correctly (empirical evaluation). The second is to consider (and, if possible, correct) the precision or specifics of the learned model by checking each learned element (model-based evaluation). This empirical evaluation is essential when the initial ontology is learned from textual learning sources. However, during ontology enrichment in the e-learning domain, quality evaluation of models for selected entities is predominantly performed. In e-learning, modeling every concept or relation is essential. It can be defined in a specific way in line with learning goals, so model-based evaluation by teachers or experts is highly significant. Usually, humans perform this type of evaluation. Teachers, learning content developers, or even students can make human-based evaluations. Student evaluations during ontology learning or interactive ontology development can make evaluation cheaper while also benefiting the learning process. The drawback of this approach is that the quality of the evaluation needs to be guaranteed, and teachers or resource developers should conduct the final evaluation.

4. Overview of Existing Research on the Automation of Ontology Development for E-Learning

E-learning is a complex domain that embraces e-learning standards; pedagogical, psychological, technological, and tutoring domains; and learner-described knowledge. This specific complexity makes the application of ontology learning methods more difficult. To the authors’ knowledge, the current study is the first attempt to survey the application of ontology learning to support ontology development in the e-learning domain. Table 2 summarizes research on the automation of ontology development in the e-learning domain. NLP algorithms are frequently used to support the extraction of the concept–relation–concept triple from textual resources.

Table 2.

Summary of the research on the automation of ontology development in e-learning.

Atapattu et al. investigated the effectiveness of automated approaches in extracting concepts and auto-generating concept maps from lecture slides [54]. Experts evaluated auto-generated concept maps. The research presents the development of a set of NLP algorithms to support the extraction of the concept–relation–concept triple from tutoring presentations. The natural layout of the lecture slides was also used to help organize extracted concepts in a hierarchy. Thus, various applications can use auto-generated concept maps, including knowledge organization and reflective visualization of course content.

A framework for automatically constructing and extending Educational Domain Ontology, called ‘ADOL’, is proposed in [48]. This ontology learning framework can automatically convert domain textbooks into a corresponding ontology. This was tested in a high school physics course, and researchers found it feasible and efficient. A semi-automatic interactive ontology learning process to facilitate domain ontology enrichment is presented in [55]. Web information sources, such as the Glossary of Programming Terms Used in C++ and lexicosyntax patterns, can support the extraction and recognition of needed relationships from textual resources.

In [56], Gaeta et al. introduce a hierarchical clustering algorithm to derive a concept hierarchy from the textual learning content. Then, background knowledge from WordNet was used to label the extracted hierarchy and detect synonyms. The effectiveness of this method was tested in seven domains: tourism, art, user modeling, problem-solving, databases, and information systems. The F-measure across the experiments ranged from 0.69 to 0.85.

Research by Lau et al. proposed a mechanism for generating a concept map using a fuzzy domain ontology extraction algorithm [52]. Such a mechanism constructs concept maps by extracting information from messages posted to online discussion forums. The context-sensitive text mining method and the fuzzy domain ontology extraction algorithm were applied to automatically generate concept maps that represented the knowledge structures of the learning content to support students’ learning.

SCORM-based hierarchical organization of the learning content in learning objects was used during ontology generation [53]. Navigation rules were applied during ontology creation in correspondence with SCORM rules. For example, a SuggestedOrder relation between two concepts was generated if the item corresponding to the source concept had a Sequencing Control Choice=True. Statistical and data mining algorithms were implemented to identify concepts and their relationships. Transformation rules were used in [59] to build an OWL ontology from the Relational Database used by an LMS Moodle to store information about learners, learning content, and the entire tutoring process. Database-to-ontology transformation rules were enriched by analyzing stored data to detect constraints on disjointedness and totality in hierarchies. Data analysis was also used to recover some missing aspects during the mapping of the conceptual data model to the relational model. The generated ontology also had non-taxonomic relations.

A study [61] presented a robotic multi-agent system that constructed an ontology to analyze student learning behavior in the context of English speaking and listening. A deep neural network (DNN) method was used. The agent integrated three types of intelligence: perception, computational, and cognition.

Recent advancements in LLMs have offered a novel opportunity to automate and refine ontology learning, yet the authors found only one related study in the educational domain [62]. This research applied LLMs to process lecture slide texts for domain ontology extraction and used them to enhance student performance predictions.

Another study [63] discusses two publications related to ontology learning, LLMs, and e-learning. However, a key drawback of both publications is that they do not focus explicitly on educational applications. Instead, they primarily investigate ontology learning for other purposes and merely propose, at a conceptual level, that the learned ontologies could be applied in educational contexts, without providing empirical validation or concrete educational use cases. For example, other research [67,68] investigated how LLMs can support and automate collaborative ontology engineering by gradually shifting from human-centered to LLM-centered workflows, and the authors discussed the usage of the generated ontologies in education.

Recent research on semantic knowledge modeling in education presents a systematic literature review that examines ways of constructing knowledge graphs (KGs) and their applications in the field of education [64]. It highlights the methodologies used to build educational KGs, knowledge extraction techniques, and how knowledge graphs are used across five key educational domains—including adaptive and personalized learning, curriculum design, concept mapping, and semantic search. The research covers automated and semi-automated knowledge graph construction techniques used in education, but the discussion is high-level and descriptive, rather than deeply analyzing ontology/knowledge graph learning algorithms or LLM-based automation.

Other research [66] used data mining techniques to analyze learner data and support the enrichment of learner ontology. The ontology was used as a conceptual backbone to structure learner interactions.

All the research publications on automating ontology development in the e-learning domain presented in Table 2 concern learning ontologies labeled in English. This is because most scientific research is conducted and published in English, as an international language. According to the authors’ experience, bilingual ontologies are often more helpful than monolingual ontologies in e-learning. The following section presents a use case illustrating the advantages of bilingual ontologies.

5. Use Case and Discussion

5.1. Use Case

One of the most valuable specifics of ontology learning in the educational field is the possibility of using semi-automatic ontology development or evaluation as a learning task. Such an approach can both reduce the cost of developed ontologies and deepen the understanding of learning content. To demonstrate how ontology learning can enhance the educational process, a small use case on ontology learning from textual content in a programming course at the Technical University of Sofia is presented.