4. Experimental Setup

This section evaluates FedRazor on standard image classification benchmarks under federated unlearning scenarios. We first describe the experimental setup, including datasets, models, federated learning configuration, metrics, baselines, ablation design, and implementation details. Subsequent subsections present quantitative and qualitative results based on this setup.

4.1. Datasets

We use three widely adopted image classification datasets. This choice covers simple and complex label spaces and both grayscale and color images.

First, we use

MNIST [

47], which is a ten-class handwritten digits dataset. Each image has resolution

and a single grayscale channel. The dataset contains

training images and

test images. MNIST provides a simple benchmark to study basic unlearning behavior.

Second, we use

CIFAR-10 [

48], which is a ten-class natural image dataset. Each image has resolution

and three color channels. The dataset has

training images and

test images. CIFAR-10 introduces more diverse content and background, which is useful to test robustness of unlearning under realistic conditions.

Third, we use

CIFAR-100 [

48], which is a hundred-class natural image dataset. Each image also has resolution

with three channels. The dataset has

training images and

test images. CIFAR-100 has a much larger label space, which makes both backdoor injection and unlearning more challenging.

We simulate different client data heterogeneity levels by partitioning each dataset into client shards. We denote by N the total number of clients and by the number of distinct classes assigned to each client. We use four partition patterns.

In the Pat-10 setting, each client holds only of the total classes. For MNIST and CIFAR-10, this corresponds to . For CIFAR-100, this corresponds to . This pattern creates highly non-IID data.

In the Pat-20 setting, each client holds of the total classes. For MNIST and CIFAR-10, this corresponds to . For CIFAR-100, this corresponds to . This pattern remains non-IID but less extreme.

In the Pat-50 setting, each client holds of the total classes. For MNIST and CIFAR-10, this corresponds to . For CIFAR-100, this corresponds to . This pattern approximates a moderate heterogeneity level.

In the IID setting, each client can observe all classes. For MNIST and CIFAR-10, this corresponds to . For CIFAR-100, this corresponds to . For all patterns, we use balanced partitioning, that is, each client receives approximately the same number of samples. This balanced design avoids degenerate cases where one client dominates the training signal.

5. Results

5.4. Ablation Study

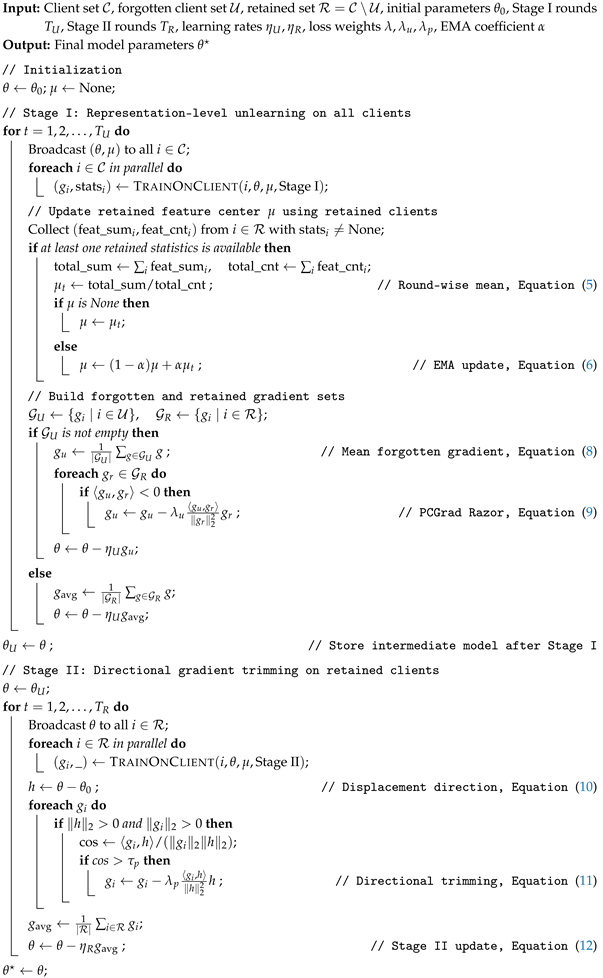

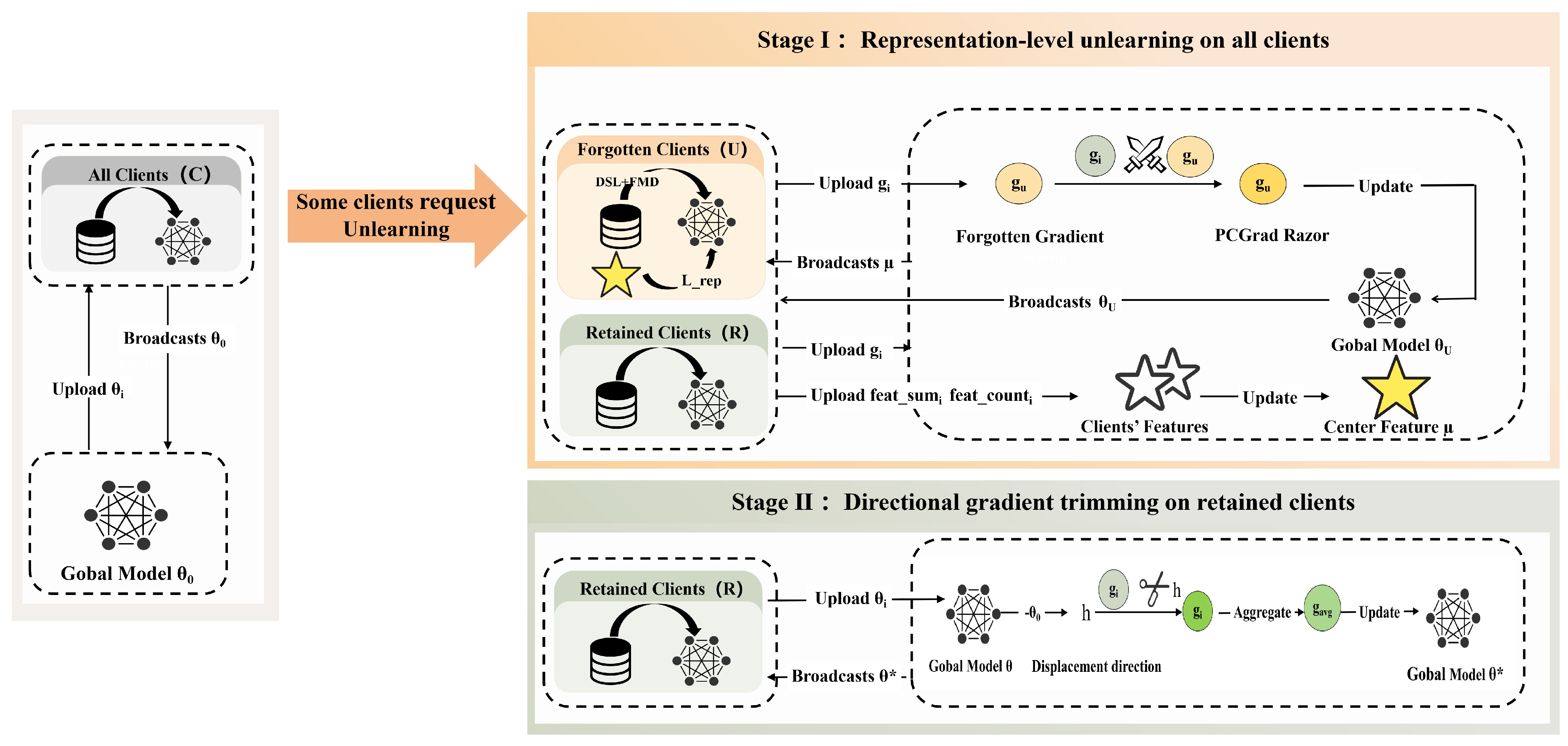

FedRazor consists of two key components in our final ablation design: (i) GradRazor, which trims harmful/forgetting-aligned gradients to stabilize forgetting and recovery; (ii) CombProj, a combination projection mechanism that constrains update directions to mitigate conflicts. To quantify their contributions and interactions, we remove one component at a time and also remove both jointly. We report the final model performance after Stage II (post-training), using ASR (lower is better) and retained accuracy R-Acc (higher is better). We also study FedRazor’s sensitivity to key hyperparameters to assess robustness.

Table 7 and

Table 8 summarize the ablation results under Pat-20 and Pat-50 across MNIST, CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100.

Full denotes FedRazor with both components enabled.

Table 9 reports the performance of the

Full FedRazor under different hyperparameter settings.

(1) GradRazor is the most critical component. Removing GradRazor consistently increases ASR and often reduces retained utility, especially under non-IID settings. For example, on MNIST Pat-50, ASR rises from 0.016 (Full) to 0.154 (w/o GradRazor); on CIFAR-10 Pat-20, ASR increases from 0.018 to 0.116. In many cases, R-Acc also drops when GradRazor is removed (e.g., MNIST Pat-20: 0.951 → 0.917; CIFAR-10 Pat-20: 0.598 → 0.536), indicating that GradRazor benefits both forgetting and utility preservation.

(2) Strong synergy between GradRazor and CombProj. Jointly removing GradRazor and CombProj causes severe forgetting failure in non-IID scenarios: MNIST Pat-20 ASR reaches 0.603, CIFAR-10 Pat-20 reaches 0.649, and MNIST Pat-50 reaches 0.862. These values are dramatically higher than removing GradRazor alone, demonstrating that CombProj is most effective when paired with GradRazor.

(3) CombProj alone yields minor changes but stabilizes the full pipeline. When only CombProj is removed, ASR/R-Acc changes are typically small (e.g., CIFAR-10 Pat-20: ASR 0.018 → 0.019; CIFAR-100 Pat-20: ASR 0.003 → 0.004), suggesting that CombProj is not the primary driver of forgetting by itself, but serves as a stabilizer that amplifies the effect of GradRazor when both are used.

(4) Performance Across Hyperparameter Settings. FedRazor is robust to and , causing only minor changes (e.g., ASR 0.001; R-Acc 0.941), while is more sensitive: low values reduce forgetting, moderate values stabilize it (e.g., ASR 0.001 → 0.007; R-Acc 0.941 → 0.933), showing that proper tuning of can improve forgetting without harming retained performance.

Overall, the ablation results support the following mechanism: GradRazor directly controls forgetting stability and prevents re-introduction of forgotten behavior during recovery, while CombProj constrains update directions to reduce harmful interactions and enables GradRazor to operate effectively. Consequently, the full configuration achieves the best balance between low ASR and high R-Acc, particularly under heterogeneous (Pat-20/Pat-50) partitions. Moderate tuning of key hyperparameters can further enhance forgetting without harming retained performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H. (Yanxin Hu) and G.L.; methodology, Y.H. (Yanxin Hu) and X.L.; software, Y.H. (Yanxin Hu); validation, Y.H. (Yanxin Hu), X.L., and Y.H. (Yan Huang); formal analysis, Y.H. (Yanxin Hu); investigation, Y.H. (Yan Huang) and J.P.; resources, C.C. and G.L.; data curation, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H. (Yanxin Hu); writing—review and editing, X.L., Y.H. (Yan Huang), and G.L.; visualization, J.P. and C.C.; supervision, G.L.; project administration, G.L.; funding acquisition, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the Jilin Provincial Department of Education [Grant No. JJKH20240860KJ].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Sheller, M.J.; Edwards, B.; Reina, G.A.; Martin, J.; Pati, S.; Kotrotsou, A.; Milchenko, M.; Xu, W.; Marcus, D.; Colen, R.R.; et al. Federated learning in medicine: Facilitating multi-institutional collaborations without sharing patient data. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairouz, P.; McMahan, H.B.; Avent, B.; Bellet, A.; Bennis, M.; Bhagoji, A.N.; Bonawitz, K.; Charles, Z.; Cormode, G.; Cummings, R.; et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2021, 14, 1–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fan, Y.; Tse, M.; Lin, K.Y. A review of applications in federated learning. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, P.; Von dem Bussche, A. The eu general data protection regulation (gdpr). In A Practical Guide, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10, pp. 141–187. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, E.L.; Vanto, J.J.; Clark, R.; Hannah Ji, L.; Ainsworth, S.C. Understanding the scope and impact of the california consumer privacy act of 2018. J. Data Prot. Priv. 2019, 2, 234–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yang, J. Towards making systems forget with machine unlearning. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, San Jose, CA, USA, 18–20 May 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 463–480. [Google Scholar]

- Halimi, A.; Kadhe, S.; Rawat, A.; Baracaldo, N. Federated unlearning: How to efficiently erase a client in fl? arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.05521. [Google Scholar]

- Romandini, N.; Mora, A.; Mazzocca, C.; Montanari, R.; Bellavista, P. Federated unlearning: A survey on methods, design guidelines, and evaluation metrics. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 11697–11717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Ma, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, J. Federaser: Enabling efficient client-level data removal from federated learning models. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM 29th International Symposium on Quality of Service (IWQOS), Tokyo, Japan, 25–28 June 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Shen, J.; Peng, M.; Lam, K.Y.; Yuan, X.; Liu, X. A survey on federated unlearning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. Acm Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Han, Y.; Fan, L.; Yang, Q. Unlearning during learning: An efficient federated machine unlearning method. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.15474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Sima, J.; Prakash, S.; Rana, V.; Milenkovic, O. Machine unlearning of federated clusters. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.16424. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Zhu, S.; Mitra, P. Federated unlearning with knowledge distillation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.09441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, P.; Zhou, W. Fedrecovery: Differentially private machine unlearning for federated learning frameworks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 4732–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Zheng, K.; Wang, B.; Tang, X.; Zhao, J. Federated unlearning with gradient descent and conflict mitigation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 19804–19812. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; Tao, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Niyato, D. A survey of federated unlearning: A taxonomy, challenges and future directions. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.19218. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Xiong, P.; Zhu, T.; Yu, P.S. A survey on machine unlearning: Techniques and new emerged privacy risks. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2025, 90, 104010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wu, Z.; Wang, C.; Jia, X. Machine unlearning: Solutions and challenges. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2024, 8, 2150–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, S.; Xie, X.; Qi, H. Federated unlearning via class-discriminative pruning. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022, Virtual, 25–29 April 2022; pp. 622–632. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yu, S. Machine unlearning: A comprehensive survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.07406. [Google Scholar]

- Wichert, L.; Sikdar, S. Rethinking Evaluation Methods for Machine Unlearning. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 4727–4739. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Li, J.; Zeng, P.; de Witt, C.S.; Prabhu, A.; Sanyal, A. Delta-influence: Unlearning poisons via influence functions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.13731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, C.; Lian, D.; Chen, E. Efficient Machine Unlearning via Influence Approximation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.23257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderloui, N.; Yan, S.; Wang, B.; Fu, J.; Wang, W.H.; Liu, W.; Hong, Y. Rectifying Privacy and Efficacy Measurements in Machine Unlearning: A New Inference Attack Perspective. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.13009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Wu, J.; Zhou, M.; Liang, P.; Phung, D. IMU: Influence-guided Machine Unlearning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.01620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, J.; Ram, P.; Yao, Y.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Sharma, P.; Liu, S. Model sparsity can simplify machine unlearning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 51584–51605. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.; Zhu, T.; Xiong, P.; Wu, Y.; Guan, F.; Zhou, W. Zero-shot Class Unlearning via Layer-wise Relevance Analysis and Neuronal Path Perturbation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.23693. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, W.; Yu, P.S. Update selective parameters: Federated machine unlearning based on model explanation. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2024, 11, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ye, H.; Chen, C.; Zheng, Y.; Lam, K.Y. Threats, attacks, and defenses in machine unlearning: A survey. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Liang, H.; Yuan, J.; Jiang, J.; Wang, K.Y.; Hu, C.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, D. Zero-shot federated unlearning via transforming from data-dependent to personalized model-centric. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-25, Montreal, QC, Canada, 29–31 August 2025; pp. 6588–6596. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Tong, X.; Liu, Z.; Ye, H.; Tan, C.W.; Lam, K.Y. Efficient federated unlearning with adaptive differential privacy preservation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Washington, DC, USA, 15–18 December 2024; IEEE: NewYork, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 7822–7831. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, J.; Ma, X.; Jiang, Q.; Ma, Z.; Gao, S.; Ying, Z.; Ma, J. FedWiper: Federated Unlearning via Universal Adapter. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 4042–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, Z. Hierarchical Federated Unlearning for Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.17895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, P.; Qi, H.; Huang, J.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, Q. Federated unlearning with momentum degradation. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 8860–8870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraboni, Y.; Van Waerebeke, M.; Scaman, K.; Vidal, R.; Kameni, L.; Lorenzi, M. Sifu: Sequential informed federated unlearning for efficient and provable client unlearning in federated optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Valencia, Spain, 2–4 May 2024; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 3457–3465. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, J. Federated unlearning via active forgetting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.03363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wu, H.; Fang, L.; Zhou, L. Fedscale: A federated unlearning method mimicking human forgetting processes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Wireless Artificial Intelligent Computing Systems and Applications, Qindao, China, 21–23 June 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 454–465. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z.; Bao, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, J.; Lyu, L.; Lim, W.Y.B. Unlearning through knowledge overwriting: Reversible federated unlearning via selective sparse adapter. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 30661–30670. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Guan, H.; Lee, H. k.; Liu, R.; Zou, J.; Xiong, L. FedSGT: Exact Federated Unlearning via Sequential Group-based Training. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.23393. [Google Scholar]

- Ameen, M.; Wang, P.; Su, W.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Q. Speed up federated unlearning with temporary local models. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 2025, 10, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, W.; Hao, Y.; Yan, X.; Cao, Y.; Lim, W.Y.B. Verifiably Forgotten? Gradient Differences Still Enable Data Reconstruction in Federated Unlearning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.11097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.L.; de Oliveira, M.T.; Braeken, A.; Ding, A.Y.; Pham, Q.V. Towards Verifiable Federated Unlearning: Framework, Challenges, and the Road Ahead. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.00833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Gao, Z.; Du, H.; Ren, J.; Xie, Z.; Niyato, D. Blockchain-enabled trustworthy federated unlearning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.15917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.T.; Nguyen, T.B.; Nguyen, P.L.; Nguyen, T.T.; Weidlich, M.; Nguyen, Q.V.H.; Aberer, K. Fast-fedul: A training-free federated unlearning with provable skew resilience. In Proceedings of the Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Vilnius, Lithuania, 8–12 September 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Zhu, Y. Model Inversion Attack against Federated Unlearning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.14558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 2002, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Hinton, G. Learning Multiple Layers of Features from Tiny Images; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, A.; De, S.; Smith, S.L. Characterizing signal propagation to close the performance gap in unnormalized resnets. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.08692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |