Abstract

Elderly patients often experience multimorbidity and long-term polypharmacy, making medication safety a critical challenge in disease management. In China, the concurrent use of Western medicines and proprietary Chinese medicines (PCMs) further complicates this issue, as potential drug interactions are often implicit, increasing risks for physiologically vulnerable older adults. Although large language model-based medical question-answering systems have been widely adopted, they remain prone to unsafe outputs in medication-related contexts. Existing retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) frameworks typically rely on static retrieval strategies, limiting their ability to appropriately allocate retrieval and verification efforts across different question types. This paper proposes FusionGraphRAG, an adaptive RAG framework for geriatric disease management. The framework employs query classification-based routing to distinguish questions by complexity and medication relevance; integrates dual-granularity knowledge alignment to connect fine-grained medical entities with higher-level contextual knowledge across diseases, medications, and lifestyle guidance; and incorporates explicit contradiction detection for high-risk medication scenarios. Experiments on the GeriatricHealthQA dataset (derived from the Huatuo corpus) indicate that FusionGraphRAG achieves a Safety Recall of 71.7%. Comparative analysis demonstrates that the framework improves retrieval accuracy and risk interception capabilities compared to existing graph-enhanced baselines, particularly in identifying implicit pharmacological conflicts. The results indicate that the framework supports more reliable geriatric medical question answering while providing enhanced safety verification for medication-related reasoning.

1. Introduction

Driven by extended life expectancy and declining fertility rates, the global demographic structure is undergoing an irreversible transition toward population aging. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the global population aged 60 years and above is projected to double to 2.1 billion by 2050 [1]. This demographic shift places significant and increasing pressure on healthcare systems worldwide, characterized by a rising prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and complex multimorbidity patterns. Older adults frequently suffer from multiple coexisting conditions—such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases—leading to the widespread phenomenon of polypharmacy [2,3,4].

Polypharmacy involves not merely the accumulation of medications but also intricate interactions across pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) dimensions. In East Asian clinical settings, this complexity is further exacerbated by the integration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) with conventional Western pharmacotherapy. Elderly patients often concurrently use proprietary Chinese medicines (PCMs) and chemical drugs, increasing the risk of overlooked herb–drug and drug–drug interactions (DDIs) [5,6]. Consequently, there is an urgent demand for intelligent medical information systems capable of supporting complex disease management with high levels of accuracy, interpretability, and individualized risk assessments.

However, existing information access technologies exhibit notable limitations in high-stakes geriatric consultations. Traditional search engines suffer from fragmented information organization and limited contextual understanding, while older adults often face additional barriers caused by information overload, declining digital literacy, and cognitive impairment [7,8,9,10].

Meanwhile, recent studies have demonstrated that large language models (LLMs), despite their strong generative capabilities, may produce factually incorrect or unsafe medical responses when applied to healthcare scenarios [11,12,13]. Although Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) has been proposed to mitigate these issues by grounding generation in external knowledge, current RAG paradigms frequently encounter challenges regarding logical inconsistency, brittle reasoning chains, and semantic granularity mismatch when addressing complex medical queries [14,15,16,17].

Despite these advancements, a critical research gap persists in bridging the disconnect between unstructured medical narratives and structured pharmacological knowledge graphs (KGs) while maintaining safety in high-stakes geriatric care [11,12,13,14,15]. Current systems frequently rely on static retrieval pipelines that perform poorly when faced with varying query complexities and retrieval-sensitive performance variations [16,17,18]. Furthermore, the lack of explicit semantic verification layers limits the ability to intercept latent logical conflicts in polypharmacy scenarios, particularly in safety-critical medical settings [19,20,21]. Crucially, medication safety risks can be amplified by implicit pharmacological conflicts, including active-ingredient overlap (cumulative dosing) and pharmacological antagonism, which may not appear as explicit textual contradictions and thus can be missed by standard hallucination-mitigation or consistency-checking strategies.

To address the aforementioned challenges in geriatric health-oriented medical dialogue, we propose FusionGraphRAG, an adaptive RAG framework designed to support reliable and interpretable reasoning under heterogeneous medical contexts. The framework explicitly addresses the limitations of static RAG pipelines by integrating an intent-aware routing mechanism, dual-granularity knowledge alignment, and a closed-loop safety verification process, thereby enabling adaptive retrieval, structured reasoning, and risk-aware response generation in complex polypharmacy scenarios. By incorporating a hierarchical triage–verification–reasoning workflow inspired by human medical experts, FusionGraphRAG aims to enhance both interpretability and safety in high-stakes elderly care applications.

The primary contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- Adaptive Hierarchical Retrieval: To address the limitations of static retrieval pipelines under varying query complexities, an intent-aware routing controller based on fuzzy logic is proposed to dynamically allocate retrieval depth and reasoning resources according to the semantic complexity and risk profile of user queries, thereby balancing computational efficiency with clinical accuracy.

- Dual-Granularity Collaboration: To mitigate the semantic granularity mismatch between unstructured medical narratives and structured KGs, a dual-granularity agent is designed to align fine-grained medical entities with coarse-grained graph community summaries, enabling coherent semantic integration across micro-level factual evidence and macro-level clinical context.

- Enhanced Safety Interception: To address the lack of semantic verification mechanisms in existing RAG-based medical systems, a DeepSearch agent incorporating a cross-encoder-based contradiction detection module is introduced to proactively identify implicit logical conflicts and high-risk pharmacological interactions during the reasoning process.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on medical RAG, GraphRAG, and safety-aware agentic systems. Section 3 presents the FusionGraphRAG framework, including the routing coordinator, dual-granularity retrieval, and the DeepSearch safety verification module. Section 4 reports experimental settings and results on GeriatricHealthQA and PolyPharm-NLI. Section 5 discusses clinical implications and deployment considerations, followed by conclusions in Section 6.

2. Related Work

2.1. Evolution and Reliability Bottlenecks of RAG Technology

RAG has emerged as a widely adopted paradigm for enhancing factual grounding and extending the knowledge boundaries of LLMs in knowledge-intensive tasks [22]. Early RAG systems primarily relied on dense vector retrieval techniques, such as Dense Passage Retrieval (DPR), to identify relevant textual evidence [23]. Subsequent studies have explored hybrid retrieval strategies and large-scale benchmark evaluations to analyze retriever robustness across heterogeneous query types [24].

In recent years, extensive surveys have systematically examined the application of RAG in healthcare and medical domains, highlighting its potential to improve factual consistency and domain coverage compared with standalone LLMs [11,12,13,14,15]. However, these studies consistently report that the effectiveness and reliability of RAG systems are highly sensitive to retrieval quality and pipeline design choices. Empirical evaluations further indicate that retrieval performance often determines the upper bound of downstream generation quality, particularly in specialized and safety-critical scenarios [18].

A key reliability bottleneck arises from the rigidity of retrieval strategies, where static retrieval depths and uniform reasoning pipelines are applied indiscriminately across diverse query types. Such rigid retrieval pipelines fail to account for substantial variations in query complexity and clinical risk, especially in geriatric health consultations where medication-related queries require deeper evidence aggregation and safety-oriented reasoning than routine informational requests [16,17].

As a result, static RAG frameworks may exhibit brittle reasoning chains and unstable outputs in retrieval-sensitive medical scenarios, underscoring the necessity of adaptive retrieval mechanisms that dynamically adjust retrieval and reasoning behaviors according to query-specific characteristics [18].

2.2. GraphRAG and Semantic Granularity Mismatch

To enhance reasoning, KGs have been incorporated into retrieval pipelines to provide explicit relational evidence paths [25]. Early approaches attempted to jointly encode textual and graph-structured information. However, local expansion strategies often suffer from subgraph explosion, where excessive irrelevant nodes introduce knowledge noise.

To mitigate this issue, global abstraction frameworks and factuality-oriented graph reasoning methods shift the focus from local entity expansion toward holistic graph summarization and factuality-oriented graph reasoning [26,27]. By applying community detection algorithms such as the Leiden algorithm, hierarchical community representations can be constructed to support high-level thematic reasoning [28]. Despite these advances, a persistent challenge in clinical applications is semantic granularity mismatch, where systems overemphasize micro-level entity anchoring while exhibiting challenges in capturing macro-level intents [29].

This imbalance leads to fragmented reasoning logic, in which inference paths fail to coherently bridge localized pharmacological facts and holistic safety assessments in complex polypharmacy scenarios, limiting the applicability of existing GraphRAG methods in geriatric disease management tasks.

2.3. Agent Collaboration and Safety Deficits in Medical Decision-Making

Agent-based frameworks have enabled models to autonomously plan and execute multi-step workflows [30,31]. In the medical domain, agentic architectures have shown promise in simulating expert consultation processes [32]. However, existing systems often exhibit a deficiency in explicit safety mechanisms for high-risk scenarios involving polypharmacy.

A critical limitation lies in the implicit assumption that retrieved evidence is inherently consistent. In geriatric care settings, medical knowledge is often heterogeneous or even contradictory due to multimorbidity, population-specific contraindications, and herb–drug or DDIs [2,3,4,5,6]. Recent studies indicate that agentic systems tend to over-trust retrieved contexts and struggle to detect latent logical conflicts, even when generated reasoning chains appear linguistically coherent [19]. Consequently, unsafe medical conclusions may be silently propagated through seemingly valid reasoning trajectories.

Current safety-oriented approaches primarily rely on self-reflection or post hoc reasoning correction mechanisms to mitigate hallucinations and logical inconsistencies [20,21]. While such methods can improve surface-level coherence, they often exhibit limited effectiveness in preventing cascading reasoning errors in safety-critical environments. These observations motivate the integration of explicit semantic verification and contradiction detection mechanisms into agentic medical systems, particularly for high-risk applications such as geriatric polypharmacy management.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Framework Overview

To address three critical challenges in geriatric polypharmacy management—namely rigid retrieval strategies, fragmented reasoning logic, and insufficient safety verification—this study presents FusionGraphRAG, a hierarchically governed intelligent question-answering framework. This framework provides the unification of high accuracy, safety, and response efficiency in medical consultations through dynamic resource scheduling and multi-granular knowledge fusion.

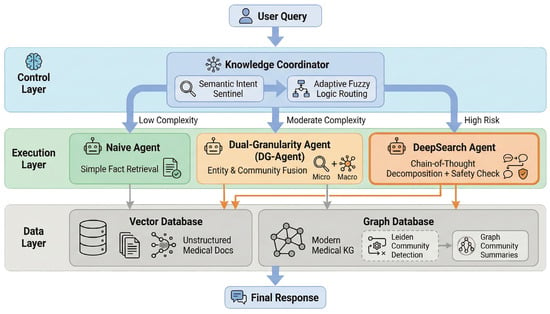

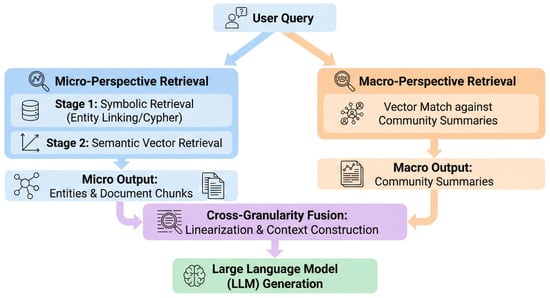

As illustrated in Figure 1, the overall architecture of FusionGraphRAG comprises three core layers:

Figure 1.

The overall architecture of FusionGraphRAG.

Data Layer: Contains unstructured medical document indices based on a Vector Database and an integrated medical KG encompassing both modern medicine and PCM based on a Graph Database. During graph construction, the Leiden community detection algorithm is applied to pre-compute and generate multi-level graph community summaries.

Execution Layer: Includes three specialized Agents optimized for varying task difficulties:

- •

- Naive Agent: Rapidly responds to simple factual queries.

- •

- Dual-Granularity Agent (DG-Agent): Resolves semantic granularity issues.

- •

- DeepSearch Agent: Addresses deep reasoning and safety concerns.

Control Layer: Deploys a modular Knowledge Coordinator that functions as the core orchestration module, responsible for parsing user queries and executing a cascade dynamic routing strategy to address resource misallocation caused by rigid strategies.

3.2. Knowledge Coordinator

We first introduce the Knowledge Coordinator, which routes each query to an appropriate agent based on estimated complexity and safety risk. To address computational inefficiency and functional inadequacy arising from uniform retrieval strategies in traditional RAG systems when handling queries of varying complexity, a dynamic routing mechanism with a two-stage cascade design is introduced.

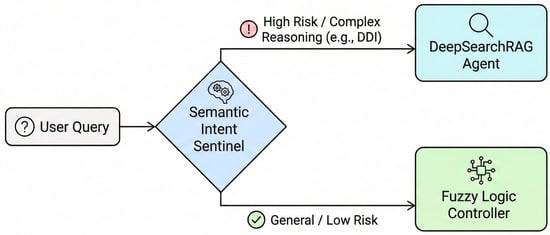

3.2.1. Semantic Intent Sentinel

To balance system safety and response efficiency within the high-risk environment of medical QA, FusionGraphRAG departs from the singular static routing strategy of traditional RAG systems and designs a cascade dynamic decision-making mechanism. The primary component of this mechanism is the Semantic Intent Sentinel, whose core responsibility is to perform qualitative risk assessment and intent recognition on user queries (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Workflow of the Semantic Intent Sentinel (Stage 1) for rapid risk assessment and routing.

In clinical consultation scenarios, tolerance for errors varies significantly across different types of queries. The Semantic Intent Sentinel utilizes a lightweight intent recognition module to parse user inputs, mapping them to predefined medical intent categories. If the system detects that a query involves high-risk intents such as polypharmacy risk assessment, DDI analysis or complex pathological reasoning, it determines that the query is directly correlated with the patient’s life safety and health.

Under these conditions, the routing mechanism adopts an early-exit strategy to preserve semantic consistency and logical alignment. This process enables the system to bypass subsequent computational quantification steps and prioritize the activation of the DeepSearch Agent. While involving higher operational costs, this agent provides comprehensive multi-step evidence exploration reasoning and dual-track contradiction detection. These capabilities enable an effective reduction in the risk of medical hallucinations. For routine queries without high-risk warnings such as medical terminology explanations and basic drug property inquiries, the sentinel performs a transfer to the second-stage resource scheduling module.

3.2.2. Adaptive Fuzzy Logic Routing

After high-risk requests are screened by the Intent Sentinel, Stage 2 focuses on allocating computational resources for routine queries under latency constraints. For routine queries filtered by the Intent Sentinel, the system balances response speed and contextual integrity. Traditional agent routing mechanisms frequently utilize rigid heuristic thresholds, which exhibit fragility when addressing the epistemic uncertainty of user intents. The Knowledge Coordinator performs query routing via an Adaptive Fuzzy Inference System (AFIS) based on the Mamdani model to replace brittle linear weighting models [33]. Feature functions define Query Volume () and Semantic Density () to establish input variable rigor. represents the information scale:

where denotes the string length. characterizes the logical depth:

where and measure inquiry frequency and medical term density, respectively. The weighting coefficient performs an adjustment of the system’s sensitivity to domain-specific terminology. In this configuration, , prioritizing medical term density as a primary indicator of query complexity.

For clarity, we describe the controller in the order of fuzzification, rule inference, and defuzzification. System operation follows three sequential phases. Fuzzification maps crisp input variables and into the fuzzy space . The system utilizes the Gaussian Membership Function (MF) to manage natural language boundary ambiguity [34]. The Gaussian function provides smooth transitions and differentiability for complexity boundaries:

where and govern the center position and the width of the membership function.

The second phase comprises Fuzzy Rule Inference based on an intent mapping matrix. This matrix delineates nonlinear correlations between , , and corresponding agent strategies. Rules interpret queries with high volume and high semantic density as possessing elevated cognitive complexity. The T-norm operator (algebraic product) computes the firing strength of each rule :

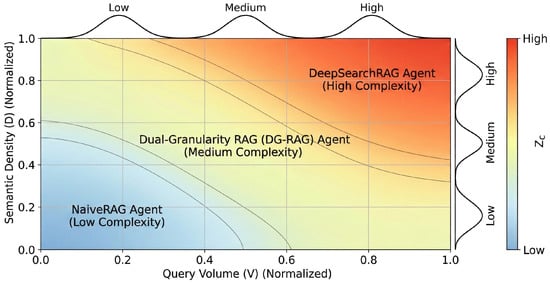

The third phase comprises Defuzzification via the Center of Gravity (CoG) method. The system transforms the aggregated fuzzy output into a continuous agent routing score (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Fuzzy Routing Intent Mapping Matrix.

Discretization of the continuous score through a threshold set determines the agent executor :

The Fuzzy Logic Controller (FLC) provides a continuous complexity assessment, while thresholds enable discrete computational resource allocation in high-concurrency medical environments. Empirical calibration determines the specific threshold values . Distribution analysis of across representative medical query samples identifies inflection points for balancing reasoning depth and response efficiency. In this configuration, = 0.35 and = 0.70. These thresholds define utility function boundaries for resource allocation. Crossing boundary indicates that utility gains from employing complex agent resources outweigh associated marginal computational costs. These thresholds map resource utility to continuous complexity metrics.

3.3. Dual-Granularity Agent

Traditional Hybrid RAG systems often encounter semantic granularity mismatch due to a lack of structured semantic support. This occurs during medium-complexity inquiries, such as attribute queries involving macro-contexts or comprehensive assessments of treatment regimens. The Dual-Granularity RAG (DG-RAG) Agent synergizes micro-entity localization with macro-graph community intent completion. The system processes queries through parallel micro (entity-centric) and macro (community-centric) pathways, utilizing knowledge linearization to fuse heterogeneous evidence into a unified prompt context. The DG-Agent is described in three steps: micro-level entity anchoring, macro-level community retrieval, and heterogeneous knowledge fusion.

As illustrated in Figure 4, the system processes queries through parallel micro (entity-centric) and macro (community-centric) pathways, utilizing knowledge linearization to fuse heterogeneous evidence into a unified prompt context.

Figure 4.

The architecture of the Dual-Granularity Retrieval Agent.

3.3.1. Micro-Perspective Retrieval for Hybrid Entity Anchoring

The micro-level retrieval pathway focuses on precise matching of concrete medical facts within user queries. It adopts a cascade retrieval strategy that prioritizes symbolic KG matching and falls back to semantic vector retrieval when structured evidence is insufficient, thereby combining the precision of symbolic reasoning with the generalization capability of dense retrieval.

- •

- Stage 1: Exact symbolic retrieval via KG. The system executes entity linking on the user query as the primary retrieval priority to map keywords to standardized entity nodes within the KG. Subsequently, the system utilizes the Cypher query language to retrieve direct attributes of these nodes from the graph database. This step enables high-fidelity structured knowledge extraction, reducing probabilistic errors inherent in model generation.

- •

- Stage 2: Semantic vector retrieval as fallback. In the absence of valid results from Stage 1, the system triggers vector retrieval as a fallback mechanism. This phase utilizes the multilingual, multi-granularity pre-trained embedding model BGE-M3 to map the user query into a dense vector. The system performs an Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) search within the vector index, retrieving semantically relevant unstructured document chunks and similar KG entity nodes:

3.3.2. Macro-Perspective Retrieval for Community-Aware Intent Completion

The DG-Agent performs a macro-retrieval mechanism grounded in graph topological structure to capture implicit macro-intents, such as inquiries regarding general medication side effects. The macro-level retrieval module retrieves synthesized community-level knowledge representations, distinguishing them from the micro-level retrieval of fine-grained factual fragments. This mechanism abstracts high-level semantic structures from isolated entity nodes, addressing the scope limitations inherent in the micro-perspective.

During the pre-processing phase, the system applies the Leiden algorithm to perform a global topological analysis of the medical KG. By maintaining intra-community connectivity and optimizing modularity, the Leiden algorithm prevents the generation of structurally loose pseudo-communities, making it suitable for sparse and heterogeneous medical graphs. This algorithm partitions the graph into coupled semantic communities, aggregating drugs with similar pharmacological mechanisms, related indications, and potential complications. This realizes the unsupervised clustering and structured reorganization of discrete medical knowledge.

The system utilizes LLMs as knowledge compressors to generate structured community summaries for each partitioned graph community. Standardized prompts guide the LLM to traverse core nodes and edges within the community to distill shared pharmacological features, risk alerts, and interaction patterns. These summaries convert implicit topological information into natural language meta-knowledge stored in the vector index, connecting the graph structure with the semantic space.

During the inference phase, the system utilizes the BGE-M3 model to map the user query into the community summary index space. The retrieval target consists of summative community descriptions rather than specific document chunks. For instance, for a query regarding contraindications for hypertension medication, the macro-pathway recalls general risk alerts from the antihypertensive drug community, addressing the potential omissions of the micro-perspective.

3.3.3. Heterogeneous Knowledge Linearization and Context Fusion

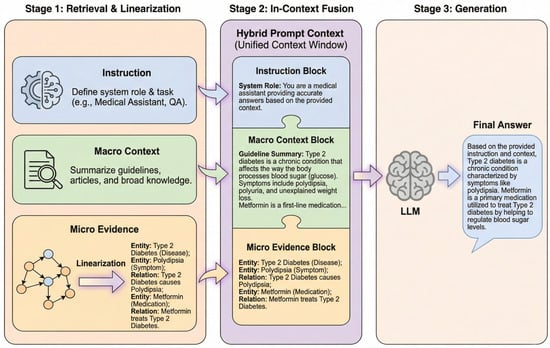

With micro evidence and macro summaries retrieved, the remaining challenge is to present heterogeneous graph structures in a Transformer-compatible form, which we address via knowledge linearization and hierarchical fusion. A fusion paradigm bridges the modal gap between structured graph data and unstructured text. As illustrated in Figure 5, the heterogeneous knowledge processing workflow comprises three sequential stages including parallel retrieval of macro-community summaries and micro-graph evidence, conversion of micro-graph structures into serialized natural language via a linearization protocol, and hierarchical fusion of linearized evidence and macro-summaries in-context.

Figure 5.

The framework of Heterogeneous Knowledge Linearization and In-Context Fusion.

The system employs a template-based serialization mapping strategy to resolve the incompatibility between native graph data and transformer architectures. Node attributes are serialized into a standardized textual format consisting of an entity name, type, and description, while triplet relationships are converted into natural language descriptions specifying the head entity, relation type, and tail entity. This linearization process transforms complex structured relationships into natural language sequences, preserving knowledge precision while mitigating modality discrepancies.

The linearization protocol ensures factual transparency and structural fidelity. The conversion of graph elements into human-readable text maintains a clear evidentiary chain for the interpretability of medical advice. Furthermore, the protocol preserves multi-hop topological logic by converting Cypher-retrieved paths into sequential narratives. This approach enables the Transformer self-attention mechanism to process relational dependencies (e.g., DrugA → IngredientX → SideEffectY) while maintaining the structured precision required for healthcare applications.

During the information fusion phase, the DG-Agent constructs a hierarchically structured hybrid prompt context. A background-to-detail assembly strategy organizes the retrieval results. The top layer contains system instructions regarding task objectives; the middle layer embeds macro community summaries to provide global background context; and the bottom layer incorporates linearized micro evidence to provide a concrete factual basis. This hierarchical arrangement guides the model to cite microdata while comprehending the macro-background, addressing disjointed logic and facts in single-retrieval pathways.

3.4. DeepSearch Agent

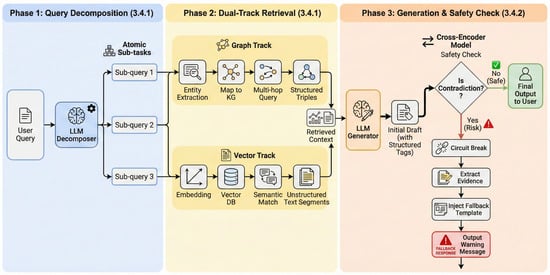

Accordingly, DeepSearch proceeds through three stages: decomposition and evidence harvesting, contradiction verification, and evidence tracing for interpretability (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The architectural overview of the DeepSearch Agent.

The DeepSearch Agent realizes graph-guided exploration chain and polypharmacy contradiction detection, mitigating precision limitations and logical fractures associated with single-retrieval modes in complex clinical narrative queries. The framework incorporates logical disassembly, synergistic recall of heterogeneous evidence, deep semantic consistency verification, and reasoning path visualization. A dedicated semantic contradiction detection mechanism constrains generated content within evidence-based medical standards, while a full-link evidence tracing mechanism achieves computational transparency. These components collectively support system interpretability and clinical recommendation safety.

3.4.1. LLM-Based Query Decomposition and Dual-Path Entity-Semantic Retrieval

The system transforms ambiguous natural language narratives into executable retrieval instructions to provide an evidentiary foundation for contradiction detection. LLMs perform intent analysis on long-text input to decompose queries into independent, atomic sub-queries. For example, the system isolates composite questions into specific disease treatment inquiries and drug interaction inquiries.

Following query decomposition, the system executes a dual-path retrieval strategy that combines entity-centric and semantic-level evidence. Named Entity Recognition (NER) is employed to extract core medical entities for multi-hop querying over the medical KG, while vector-based retrieval is used to recall unstructured long-text evidence. This dual-path design provides structured knowledge constraints alongside complementary unstructured contextual support.

3.4.2. Polypharmacy Semantic Contradiction Detection Based on Structured Isolation

Given the harvested evidence pool, we next verify whether the candidate recommendation introduces contradictions under polypharmacy constraints.

The system performs deep semantic contradiction detection based on structured isolation to manage risks in polypharmacy scenarios during the generation phase. The DeepSearch Agent utilizes a prompt-induced strategy to encapsulate drug-related content within specific structured tags via system instructions to address logical inconsistencies or the tendency of general-purpose LLMs to overlook retrieved contraindication evidence in long-text generation.

This mechanism transforms unstructured natural language streams into computable risk attention domains. This conversion enables the system to locate core recommendations within lengthy dialogue texts and dynamically trigger the deep detection process when the attention domain contains two or more drug entities. For activated polypharmacy recommendations, the system utilizes a fine-tuned Cross-Encoder model to perform Natural Language Inference (NLI), identifying deep logical conflicts between the generated content and the retrieved evidence.

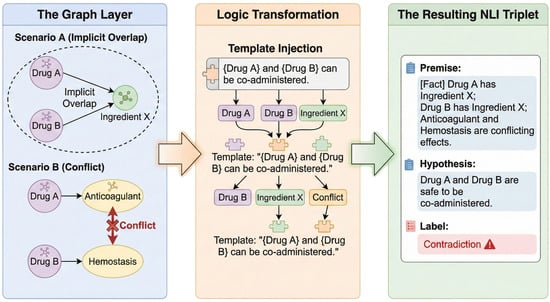

The construction of PolyPharm-NLI provides adversarial fine-tuning tailored for geriatric polypharmacy scenarios to enable the identification of implicit pharmacological conflicts. Rather than random sampling, the dataset utilizes the explicit constraint logic of medical KGs to systematically mine and create highly deceptive hard negatives. Sample construction focuses on the following three high-risk conflict categories (Figure 7):

Figure 7.

The construction pipeline of the PolyPharm-NLI dataset.

- Implicit Component Overlap: The system traverses graph data to identify drug combinations with distinct names mapping to the same active ingredient node (e.g., Tylenol and Yanlixiao Tablets both contain Acetaminophen). Component attribution relationships from the graph convert into natural language premises with contradictory hypotheses suggesting concurrent use. This mechanism enables the model to identify risks of chemical component superposition beyond commercial drug names.

- Disease-Specific Contraindication: The system utilizes contraindication relationships in the graph and caution/prohibited fields in drug package inserts to extract exclusion links between drug entities and specific disease nodes (e.g., Hypertension, Glaucoma). The system constructs erroneous recommendation samples that omit patient medical history to reinforce model sensitivity to clinical contraindication conditions.

- Pharmacological Antagonism: The system extracts attribute pairs with opposing functional semantics from pharmacological attribute nodes within the graph (e.g., potent anticoagulation versus hemostasis/coagulation). The retrieval of drug combinations with opposing pharmacodynamic mechanisms enables the construction of negative samples that omit pharmacological antagonism.

The inclusion of these three categories of adversarial training data establishes a deep discriminative capability for complex medical contexts during fine-tuning, supplementing the logical reasoning of general-purpose models regarding specialized pharmacological logic.

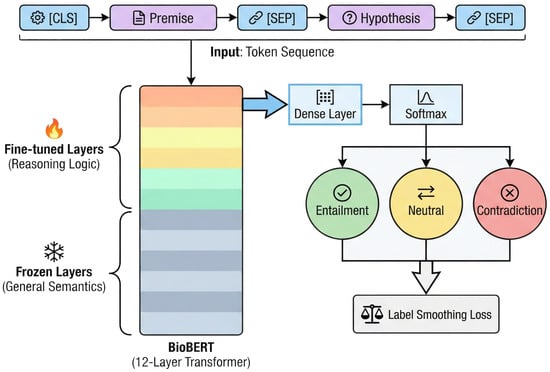

The integration of these adversarial training categories provides the Cross-Encoder with discriminative capabilities for complex medical contexts. This process supplements general-purpose models with specialized pharmacological logic. The PolyPharm-NLI dataset utilizes standard triplets where the premise field combines unstructured package insert segments with structured graph attribute descriptions to represent integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine scenarios. BioBERT-v1.1 [35] functions as the base model, providing prior knowledge of medical entity recognition and relationship understanding. The system utilizes a fully interactive Cross-Encoder architecture to perform logical reasoning for safety verification.

Input representation utilizes the standard BERT paradigm, concatenating the premise and hypothesis via special separators in the format [CLS] Premise [SEP] Hypothesis [SEP]. This configuration facilitates deep token-level interactions between text segments through the Transformer self-attention mechanism. During fine-tuning, the [CLS] vector is mapped to a three-class probability distribution corresponding to entailment, neutral, and contradiction labels through a fully connected layer followed by a softmax activation.

A parameter-efficient transfer learning strategy [36] supports generalization performance under limited labeled data. Implementation involves layer freezing during the initial training phase, where parameters of the bottom six layers of BioBERT remain fixed while the system updates only the weights of the upper Transformer layers and the classification head [37]. This approach utilizes the functional hierarchy of the network, where lower-level layers capture general syntactic and lexical features, while higher-level layers process semantic logic and domain-specific reasoning patterns.

The training objective function utilizes Cross-Entropy Loss with Label Smoothing () [38] to mitigate the model’s overconfidence when addressing ambiguous medical expressions, thereby reducing the risk of overfitting. Gray blocks signify frozen layers capturing general semantics, while colored blocks denote fine-tuned layers for specialized reasoning. Through these mechanisms, the Cross-Encoder successfully realized the knowledge transfer from general medical semantic understanding to specific pharmacological logical reasoning (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The architecture of the Cross-Encoder model with a layer-freezing strategy.

These mechanisms enable the Cross-Encoder to perform deep logical reasoning grounded in component attribution and pharmacological mechanisms, establishing an explicit semantic verification layer beyond literal matching. When the Cross-Encoder outputs a contradiction label with a confidence score exceeding the preset threshold, the system performs an interception and correction strategy. The contradiction confidence threshold is calibrated on a held-out validation split of PolyPharm-NLI via grid search. The selected threshold is then fixed and used for all test-time evaluations. Activation of this mechanism involves discarding the original LLM-generated draft, preventing the transmission of erroneous recommendations.

The system bypasses LLM regeneration and constructs the final response using an evidence-based template-filling strategy to maintain response safety. Core evidence derived from the contradiction verdict, such as statements indicating that both Tylenol and Yanlixiao Tablets contain acetaminophen, is incorporated into a predefined risk-alert template. This procedure generates responses supported by medical grounds. The mechanism utilizes retrieved evidence to supersede generated content, providing objective warning information upon the detection of high-risk scenarios and mitigating safety hazards associated with LLM hallucinations.

3.4.3. Visualization of Reasoning Paths and Full-Link Evidence Tracing

An end-to-end reasoning tracing mechanism addresses transparency requirements in medical AI and validates the contradiction detection mechanism. This mechanism converts implicit cognitive processes into structured reasoning logs to establish an evidentiary chain from the initial query to the final recommendation. The system records intermediate states in real-time during the RAG workflow to maintain an audit trail.

The system persists the task decomposition structure generated in Section 3.4.1 into execution logs to document the logical decomposition of clinical narratives into verification steps. For risk alerts triggered in Section 3.4.2, the system retains the key evidence anchors used for contradiction judgment together with their original indices. Contraindication description fragments from the vector repository and component conflict paths from the KG (e.g., DrugA→has_ingredient→X←has_ingredient←DrugB) receive unique source identifiers and are recorded in full6. This white-box logging approach provides full-process tracing for post hoc logical review and error attribution, establishing a forensic basis to support medical recommendations with traceable evidence.

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Data Acquisition and Knowledge Base Construction

A dual-source-driven data acquisition strategy establishes the professional knowledge foundation for geriatric chronic disease management. This strategy integrates specialized pharmacological databases with clinical medical encyclopedias to construct a medical KG covering multi-dimensional relationships among medication, disease, and diet.

The system utilizes the Oriental Medicine Data Center as the primary pharmaceutical data source. The dataset initially comprises 2348 raw drug entries, which are refined into 1948 clinically common medications through data cleaning and deduplication. These medications maintain a balanced 1:1 ratio between PCM and modern chemical drugs. This refined repository includes 926 drugs specifically categorized for geriatric chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular, endocrine, and respiratory conditions. These medication entities provide the knowledge foundation for generating the 2500 NLI triplets utilized in Cross-Encoder training and testing.

The system performs granular field parsing on unstructured web data to extract core attributes, including generic names, trade names, drug categories covering chemical drugs and PCMs, characteristics, active ingredients, indications, dosage, geriatric-specific prompts, adverse reactions, contraindications, and drug interactions. Entity normalization unifies disparate expressions in active ingredient fields, such as mapping acetaminophen tablets and Tylenol to a standardized chemical component node. This process establishes the foundation for detecting implicit component superposition.

The DXY Medical Encyclopedia serves as the primary clinical knowledge source for disease data, comprising 450 medical conditions with a particular focus on 90 common geriatric chronic diseases. Information extraction covers key clinical dimensions, including etiology, symptoms, complications, medication regimens, and lifestyle interventions. In addition, natural language processing techniques transform unstructured dietary advice and nursing guidelines into lifestyle management nodes within the graph.

Directional logical relationships define fine-grained lifestyle modeling. Specifically, recommended-for relationships represent positive guidance, such as bland diets, while avoid relationships correspond to negative restrictions, such as strict alcohol abstinence. This configuration enables the delivery of comprehensive health guidance tailored to specific nursing requirements during macro-level community retrieval.

A graph–text dual-modality storage architecture supports diverse retrieval requirements by abstracting logically strong correlations into five core entity types, including drug, disease, ingredient, symptom, and lifestyle management. Neo4j stores explicit relationships, such as treats and contraindicated, to facilitate downstream logical reasoning.

Simultaneously, vectorization of the full corpus of unstructured medical texts establishes a high-coverage semantic retrieval space. The data scope encompasses complete drug package inserts (including pharmacological, toxicological, and pharmacokinetic mechanisms), disease encyclopedias (covering diagnostic flows and pathological analysis), and summaries of clinical practice guidelines and dietary nutrition texts.

The graph database and the vector database serve complementary roles within the dual-modality architecture by providing structural logic and semantic richness, respectively. The graph database extracts high-density logical topological structures through the removal of redundant descriptive text, providing precise navigation paths and constraint boundaries for reasoning. Conversely, the vector database retains the full spectrum of semantic details to provide contextual support for generation. This structured navigation and semantic filling design addresses the inherent trade-off in traditional RAG systems between weak logical reasoning capabilities and high noise levels in long-text retrieval.

4.1.2. Benchmark Datasets

Evaluation of individual system components and overall question-answering efficacy utilizes two distinct datasets. The PolyPharm-NLI dataset enables the fine-tuning of the Cross-Encoder contradiction detection module. Systematic generation of 2500 NLI triplets originates from explicit topological paths within the Medical Knowledge Graph rather than random sampling. PolyPharm-NLI constructs “hard negatives” by traversing conflict paths (e.g., Drug A Ingredient X Drug B) to simulate deceptive clinical scenarios.

The dataset maintains a balanced distribution with 1300 positive (Safe/Entailment) and 1200 negative (Unsafe/Contradiction) samples to ensure discriminative robustness. To rigorously address geriatric medication risks, the negative samples are stratified into three high-stakes categories:

- •

- Implicit Component Overlap (35%): Targeting implicit duplication risks where distinct brand names share active ingredients (e.g., Xiaoke Pills containing Glibenclamide), aiming to prevent adverse events caused by cumulative dosage and overdose.

- •

- Pharmacological Antagonism (25%): Covering drug pairs with opposing mechanisms (e.g., anticoagulants vs. hemostatics), which require logical deduction beyond semantic similarity.

- •

- Specific Population Contraindications (40%): Focusing on risks exacerbated by geriatric physiology (e.g., contraindication of Anticholinergic drugs in elderly patients with prostatic hyperplasia).

These samples support the training of the model to discern logical contradictions between generated recommendations and medical facts. Typical training samples are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Example samples from the PolyPharm-NLI dataset constructed via graph topology.

The GeriatricHealthQA dataset enables the end-to-end holistic performance evaluation of the system (Table 2). Screening and extraction of consultation records from the consultation-style subset of the Huatuo-26M dataset provide high ecological validity [39]. Huatuo-26M is crawled from open-source web resources, covering online encyclopedias, knowledge bases, and consultation-style medical QA; it is released with either URL pointers or full-text records, enabling traceability. These records capture authentic patient expressions and complex multimorbidity patterns typical of online medical platforms.

Table 2.

Statistics of the GeriatricHealthQA Dataset.

Implementation of rigorous inclusion criteria targets cases of patients aged 60 and above characterized by multimorbidity and polypharmacy. Secondary processing and classification of these records establishes this evaluation benchmark. Through an additional round of manual screening and adaptation, we ensured that each record contains explicit pharmacological constraints (e.g., contraindications and indications), thereby forming a robust benchmark for safety-sensitive evaluation.

We adopt a task-aligned benchmark because our evaluation is safety-centric and requires explicit medication constraints (e.g., contraindications, indications, and dosing restrictions) as well as risk patterns such as implicit ingredient conflicts. In contrast, general-purpose medical QA settings typically emphasize broad diagnostic or factual correctness and do not systematically stress-test multi-medication safety reasoning. Therefore, GeriatricHealthQA is better suited to evaluate the proposed retrieval–verification pipeline under geriatric multimorbidity and polypharmacy conditions.

Through an additional round of manual screening and adaptation, we ensured that each record contains explicit pharmacological constraints (e.g., contraindications and indications), thereby forming a robust benchmark for safety-sensitive evaluation. Through an additional round of manual screening and adaptation, we ensured that each record contains explicit pharmacological constraints (e.g., contraindications and indications), thereby forming a robust benchmark for safety-sensitive evaluation.

The data screening process prioritized the following four dimensions to ensure experimental logical rigor:

- •

- Demographic characteristics: Inclusion criteria require patients aged 60 years or older with confirmed diagnoses of two or more chronic comorbidities, such as hypertension complicated by diabetes.

- •

- Polypharmacy scenarios: Consultation records comprise a medication list involving a total drug count N 2 to assess the resolution of complex pharmacological interactions.

- •

- Multimodal context: Records must include unstructured chief complaints, medical history, and lifestyle descriptions, such as dietary habits and alcohol consumption history, to evaluate the system’s recall effectiveness for long-tail lifestyle management queries.

To verify system robustness, we stratified the dataset into three difficulty subsets based on the number of entities involved and logical depth:

- •

- Simple Fact: This subset involves single-drug attribute queries, such as dosage and administration information for metformin, and primarily evaluates the system’s accuracy in basic information retrieval.

- •

- Inference: This subset requires multi-hop reasoning that integrates patient medical history and lifestyle context, such as evaluating medication suitability for a patient with gout following dietary intake of high-purine foods. It assesses the DG-Agent’s capability to perform cross-contextual and multi-source reasoning.

- •

- High-Risk Conflict: This subset includes samples involving implicit component overlap, severe DDIs, or contraindication risks, such as the concurrent use of warfarin with compound Danshen preparations. This category evaluates the DeepSearch agent’s ability to intercept safety-critical risks. Cases in which the system fails to identify potential hazards or prevent unsafe recommendations are recorded as critical safety breaches.

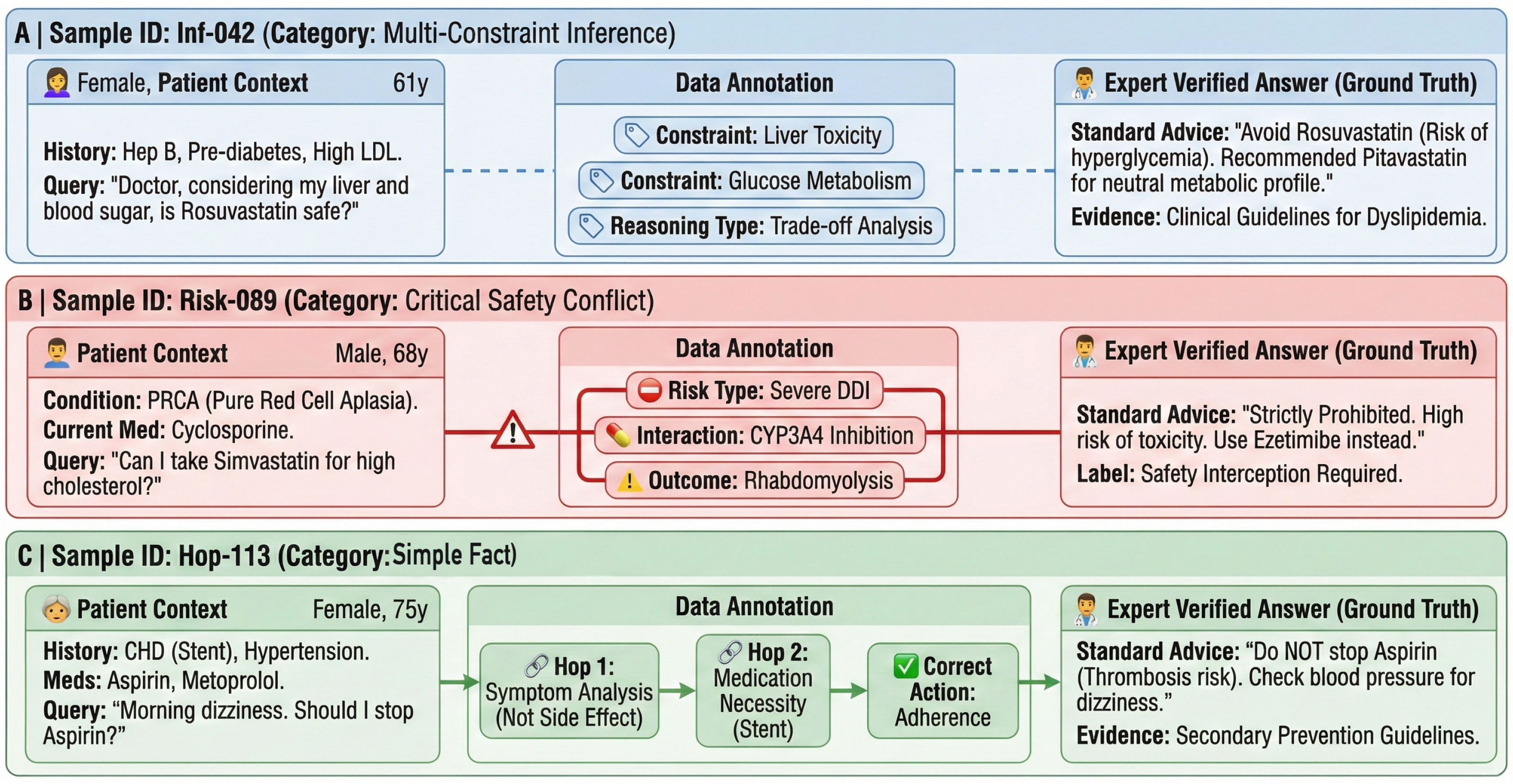

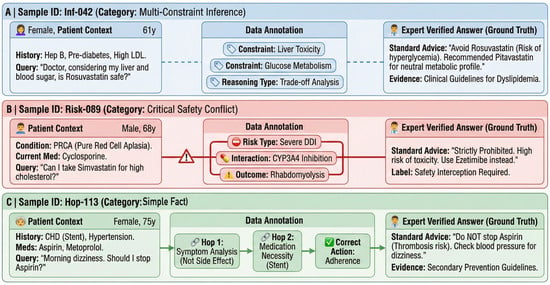

Figure 9 illustrates one representative sample from each subset (Simple Fact/Inference/High-Risk Conflict). Background colors are used to visually distinguish the subsets: blue for Inference, red for High-Risk Conflict, and green for Simple Fact. The three panels correspond to the stratification adopted in our robustness analysis. Each card follows a consistent structure, presenting the patient context (left), annotated complexity cues (middle), and the expert-verified answer with supporting evidence (right). Color denotes subset membership; conflict-related cues (e.g., “Severe DDI” and “Safety Interception Required”) are explicitly labeled.

Figure 9.

Annotated visualization of representative samples from the GeriatricHealthQA dataset.

4.2. Main Results and Performance Analysis

4.2.1. Retrieval Performance Comparison

Retrieval module recall quality determines the system response performance upper bound. Table 3 presents Hit Rate@5, Hit Rate@10, and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) metrics for evaluated models across subsets of varying difficulty. To provide a comprehensive evaluation, we incorporated comparisons ranging from foundational baselines (Naive RAG, GraphRAG) to representative graph-enhanced frameworks (G-Retriever, MedGraphRAG).

Table 3.

Retrieval performance comparison on GeriatricHealthQA dataset.

We include G-Retriever and MedGraphRAG as advanced baselines because they inject KG signals into the same retrieval pipeline as FusionGraphRAG, but at different stages [40,41]. G-Retriever improves recall through KG-guided candidate expansion, whereas MedGraphRAG improves evidence ordering (MRR) via KG-aware reranking over the initially retrieved set.

Naive RAG achieved a Hit Rate@5 of 0.363 on the Inference subset. This performance indicates that traditional vector retrieval exhibits a failure probability exceeding 63% in locating key evidence within the top-5 results when addressing multi-hop logical queries. While standard GraphRAG improves this to 0.452 by introducing topological connections, it still lags behind more recent strategies. Specifically, G-Retriever (KG-Expand) achieves the highest Hit Rate@10 (0.801) on Simple Facts due to aggressive subgraph expansion, but its MRR gain remains limited (0.512), suggesting that relevant evidence is more frequently retrieved yet not consistently ranked near the top positions. Conversely, MedGraphRAG (KG-Rerank) improves precision via path connectivity, but its performance on the Inference subset remains constrained (Hit Rate@5 = 0.479), indicating that reranking alone cannot fully compensate when the initial candidate set is incomplete.

FusionGraphRAG increases the Hit Rate@5 to 0.497. Surpassing both the foundational GraphRAG (0.452) and the reranking-based MedGraphRAG (0.479), this measured improvement demonstrates that explicit graph paths provide navigational support when vector semantics are ambiguous, reducing retrieval aimlessness.

The performance difference is most critical on the High-Risk subset. Although GraphRAG (Hit@5 = 0.491) and MedGraphRAG (Hit@5 = 0.535) improve over vector-only retrieval, FusionGraphRAG shows consistent gains across Hit@5, Hit@10, and MRR (0.548 vs. 0.535, 0.673 vs. 0.658, and 0.476 vs. 0.465, respectively), indicating a coherent improvement pattern rather than a single-metric fluctuation. This result indicates that explicit path-guided navigation with dual-modality fusion better prioritizes constraint-bearing evidence in safety-sensitive queries, where basic graph traversal or reranking may still under-rank key contraindication-related passages.

4.2.2. Generation Quality and Safety Evaluation

The generation phase prioritizes clinical plausibility and risk control. For safety evaluation, high-risk interception is treated as a binary classification task, reporting Precision, Recall (denoted as Contradiction Detection Rate, CDR), and F1-score (Table 4).

Table 4.

End-to-end generation quality and safety interception performance.

- •

- Safety Recall (71.7%): FusionGraphRAG achieved a Safety Recall of 71.7%, representing the interception of approximately 70% of high-stakes pharmacological conflicts. Critically, this performance outperforms the advanced MedGraphRAG baseline (65.2%) by an absolute margin of +6.5 percentage points. This gap suggests differences in how retrieved evidence is operationalized during generation. MedGraphRAG primarily mitigates explicit conflicts via reranking, while implicit component-level contradictions remain more challenging under this mechanism. The proposed graph-based verification provides an additional check for such cases.

- •

- Safety F1 (0.699): A composite F1-score of 0.699 indicates a balance between safety and response utility. Although our strict detection strategy results in a slightly lower Precision (0.682) compared to MedGraphRAG (0.698), the system yields the highest overall F1-score. The system exhibits a conservative profile, aligning with medical risk control principles that prioritize sensitivity (Recall) over specificity to maximize patient safety in geriatric scenarios.

- •

- Generation Quality: G-Eval results indicate that FusionGraphRAG achieves an average score of 3.91. While slightly trailing the highly fluent MedGraphRAG (3.95) due to the constraints of safety verification, our score consistently exceeds the GPT-4 zero-shot baseline (3.85). When considered alongside a BERTScore of 0.715, these results suggest that the framework successfully preserves the linguistic coherence of LLMs while enforcing necessary structured knowledge constraints to prevent hallucinations.

4.3. Ablation Study

A layered ablation study quantitatively evaluates the independent contribution of core FusionGraphRAG components, including AFIS, DG-Agent, and NLI-based Contradiction Detection. The analysis focuses on trade-offs between F1-score, CDR, and system latency, with results summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Ablation study results of FusionGraphRAG component.

4.3.1. Efficiency Hedging via Adaptive Routing

Direct integration of the KG into the retrieval pipeline without a scheduling mechanism (Group 2 in Table 5) results in a substantial latency increase to 15.8 s. This latency stems from the computational overhead of graph traversal required for every query.

The AFIS routing module (Group 3 in Table 5) improves system efficiency by dynamically dispatching simple factual queries to a lightweight retrieval path and reserving intensive graph reasoning for high-complexity requests. This implementation reduces average response latency to 8.5 s, representing a 46.2% decrease. These results demonstrate that fuzzy-logic-based routing hedges the computational cost of complex knowledge fusion while maintaining overall system accuracy.

4.3.2. Gains from Dual-Granularity Semantic Alignment

Integration of the Dual-Granularity Agent (DG-Agent, Group 4 in Table 5) improves the system F1-score to 0.682. This module enhances semantic coverage for multi-hop reasoning tasks by performing micro-level entity anchoring and macro-level community summarization. These tasks require both fine-grained factual precision and high-level contextual understanding. Parallel multi-granular retrieval introduces a marginal latency increase of approximately 0.7 s. However, the resulting robustness in handling mixed PCM and Western medicine semantics confirms the necessity of this design for specialized medical domains.

4.3.3. Safety Gains via Semantic Consistency Verification

The Cross-Encoder-based NLI module establishes a safety closed-loop system within the complete FusionGraphRAG configuration (Group 5 in Table 5). This module performs deep semantic inference to verify the logical consistency between generated pharmacological recommendations and retrieved medical evidence, moving beyond surface-level lexical matching.

Experimental results show that NLI-based verification increases the Safety Recall (CDR) from 62.5% to 71.7%. This improvement enables the detection of explicit contraindications and latent logical conflicts arising from heterogeneous terminologies and implicit ingredient overlaps between PCMs and conventional pharmaceuticals. In high-risk geriatric polypharmacy scenarios, the NLI module operates as an automated second-opinion layer that intercepts unsafe recommendations. The enforcement of semantic consistency transitions FusionGraphRAG from a retrieval-oriented system to a clinically oriented decision-support framework, supporting practitioner trust and system interpretability.

From a deployment perspective, Table 5 highlights where runtime overhead concentrates and how it may scale. The latency gap between Group 4 (9.2 s) and the full model (12.4 s) mainly reflects the added cost of DeepSearch-style iterative verification, in which the cross-encoder NLI model is invoked across multiple evidence pairs. As the retrieval scope expands—such as when more candidate medications are retrieved, larger query-specific subgraphs are constructed, or deeper graph expansion is allowed—the verification workload increases accordingly. This growth is driven by a larger candidate set to be checked, a higher number of implied evidence-pair comparisons, and potentially more exploration rounds. In practice, the trade-off can be managed by capping DeepSearch rounds and graph expansion radius, triggering NLI verification only for high-risk routes or multi-medication cases, and batching/caching frequent verification results to improve throughput.

5. Discussion

5.1. Clinical Efficacy and Pharmacological Scope

Experimental validation of FusionGraphRAG on the GeriatricHealthQA dataset demonstrates the efficacy of the framework in managing complex geriatric polypharmacy. A Hit Rate@5 of 0.497 in semantic inference tasks indicates that the integration of macro-graph community summaries bridges the gap between micro-entity anchoring and macro-level clinical intent. Additionally, the 71.7% safety recall of the DeepSearch Agent addresses a primary safety challenge of hallucination-induced risks in medical AI systems.

The performance extends to heterogeneous medication scenarios involving integrated PCM and Western medicine. However, the 28.3% margin of unidentified risks identifies a limitation in KG coverage, particularly regarding complex PCM compatibility theories such as the “Eighteen Incompatible Medicaments”. Rare or long-tail PCM interaction theories remain under-represented in the current knowledge base, which may lead to false negatives in safety interception. We therefore interpret the reported safety gains as evidence of mechanism effectiveness under offline evaluation, rather than a substitute for real-world clinical validation.

Regarding the depth of pharmacological modeling, we did not incorporate molecular-level target databases (e.g., TCMSP), as their emphasis on theoretical mechanisms aligns more closely with exploratory drug discovery than with our current experimental focus on clinical decision support. Prioritizing clinically verified interactions helps minimize semantic noise during retrieval, ensuring that the generated advice remains strictly practical for geriatric management.

Furthermore, although validated within an integrative TCM–Western context, our proposed Dual-Granularity architecture is inherently region-agnostic. Fundamentally, the risks associated with PCMs stem from pharmacological interactions (e.g., active ingredient overlaps or antagonism), which share the same logical structure as Western DDIs. Consequently, our core methodology—fine-tuning a Cross-Encoder using graph-derived NLI triplets to detect safety conflicts—is highly transferable. By simply mapping the underlying knowledge source to international standards like DrugBank or RxNorm, this “mechanism-based” verification pipeline can be seamlessly redeployed to enforce FDA or EMA regulatory requirements, thereby supporting broader cross-cultural geriatric care.

While FusionGraphRAG mitigates several known limitations of RAG-based medical QA, it does not eliminate uncertainty arising from incomplete KGs or ambiguous clinical narratives. We note that this work does not provide formal guarantees (e.g., bounds on false negatives) for medication-conflict detection. Current constraints also include the absence of multimodal parsing for clinical reports (e.g., OCR or medical imaging) and the inherent logical limitations of the base LLM. In addition, we note that the reported safety metrics are obtained under offline evaluation and do not constitute real-world clinical validation; human expert assessment and prospective studies are required before deployment in clinical workflows.

5.2. Deployment Feasibility and System Evolution

Computational feasibility and deployment practicality are important for real-world adoption, particularly in resource-constrained healthcare settings. Compared with vector-only retrieval, FusionGraphRAG introduces additional overhead due to graph reasoning and verification.

Under our current implementation, the full system incurs an average latency of 12.4 s per query (Table 5), reflecting the cost of safety-oriented processing. This latency profile is better aligned with non–ultra time-critical workflows (e.g., outpatient decision support, follow-up, or home health management). Stricter real-time settings would require further optimization.

To manage resource consumption, the framework does not inject the entire KG into the LLM context. Instead, micro-scope retrieval extracts query-relevant subgraphs and evidence snippets on demand, helping keep context size and external tool usage bounded. This dynamic subgraph extraction strategy helps keep GPU VRAM usage manageable, allowing the system to be deployed on standard medical workstations without requiring high-performance computing clusters. All experiments were conducted on a single workstation (RTX 3090 24 GB, i9-12900K, 64 GB RAM). Under the default inference setting, the peak GPU memory usage was 20.7 GB, and the peak host memory usage was 15.4 GB.

The full configuration (12.4 s; Table 5) is most suitable for non-ultra-time-critical workflows (e.g., outpatient decision support and pharmacist medication review), where comprehensive safety verification can be completed before clinical action. In bedside or emergency settings with tighter latency budgets, we adopt a tiered verification strategy: the system first returns a rapid, conservative response via the AFIS/DG pathway (8.5–9.2 s in Table 5) to provide timely guidance, and then triggers DeepSearch/NLI selectively for high-risk cases (e.g., multi-medication regimens, suspected contraindications, or severe interaction patterns). This design prioritizes intensive verification for safety-sensitive queries while maintaining responsiveness for routine requests. For edge deployment, DeepSearch/NLI can be offloaded to a server-side service or replaced with distilled/quantized verifiers and caching to further improve latency.

5.3. Future Work: System Evolution and Maintenance

Maintaining a medical KG in production also entails ongoing curation costs and integration with clinical information systems. In practice, knowledge updates are typically handled by designated maintainers under governance and audit requirements. We therefore plan a lightweight maintenance interface with role-based access control and change logging to support routine updates, including node-level edits (e.g., contraindications or dosing guidance) and evidence index management (e.g., retiring outdated snippets and adding updated references), reducing reliance on frequent full model retraining.

To preserve the Dual-Granularity design, we will investigate a community summary cascade refresh mechanism, where updates to micro-level nodes/relations selectively trigger regeneration of the corresponding macro-level community summaries to mitigate semantic drift. In parallel, we will explore semi-automated ingestion of new guidelines and documents via structured parsing and consistency checks before updating the graph and retrieval index.

Finally, long-term research directions involve expanding the knowledge foundation to incorporate multimodal graph structures (processing medical imaging and OCR reports) and exploring safety alignment through Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF).We will also evaluate generalizability on public medical QA benchmarks (e.g., MedQA and PubMedQA) under aligned, safety-centric protocols that explicitly represent medication constraints and interaction risks, to better quantify transfer beyond our domain-specific setting.

To strengthen external validity, we plan geriatrician-in-the-loop assessments with blinded review and inter-rater agreement, as well as scenario-based simulations that inject polypharmacy error patterns for stress testing. We also plan to extend the framework to multilingual queries via cross-lingual normalization and entity linking, followed by evaluation on multilingual safety-critical test sets. These directions are expected to improve system robustness in complex real-world polypharmacy scenarios where knowledge incompleteness and modality gaps remain prevalent.

6. Conclusions

FusionGraphRAG provides an adaptive RAG framework tailored for complex polypharmacy management to address semantic granularity mismatches and safety deficits in geriatric healthcare. Integration of a dual-modality knowledge foundation and an agent-based collaborative workflow establishes a functional safety barrier for high-risk medication reasoning.

Experimental results demonstrate that FusionGraphRAG consistently outperforms traditional naive RAG baselines, achieving balanced improvements in both generation quality and safety performance. In particular, the framework attains a high level of response quality as measured by automatic evaluation metrics while substantially enhancing the system’s ability to detect and intercept unsafe pharmacological recommendations.

These findings suggest that the integration of structured medical KGs with LLMs provides a viable pathway toward reliable and interpretable medical decision support. More broadly, this work offers practical insights into the design of trustworthy retrieval-augmented systems for risk-sensitive domains, highlighting the importance of adaptive reasoning strategies, multi-granular knowledge alignment, and explicit safety verification mechanisms in medical AI applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number L222048.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Mendeley Data at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/3cvnnrxrd3/1 (accessed on 2 January 2026; DOI: 10.17632/3cvnnrxrd3.1; reference number: Geriatric_Health).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| DG | Dual-Granularity |

| PCM | Proprietary Chinese Medicine |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| NER | Named Entity Recognition |

| DDI | Drug–Drug Interaction |

| KG | Knowledge Graph |

| AFIS | Adaptive Fuzzy Inference System |

| CoG | Center of Gravity |

| MRR | Mean Reciprocal Rank |

| NLI | Natural Language Inference |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Clinical Consortium on Healthy Ageing 2023: Meeting Report, Geneva, Switzerland, 5–7 December 2023; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, L.; Johnell, K.; Laroche, M.L.; Fastbom, J.; Wastesson, J.W. The epidemiology of polypharmacy in older adults: Register-based prospective cohort study. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 10, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennie, M.; Santa-Ana-Tellez, Y.; Galistiani, G.F.; Trehony, J.; Despres, J.; Jouaville, L.S.; Poluzzi, E.; Morin, L.; Schubert, I.; MacBride-Stewart, S.; et al. The prevalence of polypharmacy in older Europeans: A multi-national database study of general practitioner prescribing. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 90, 2124–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasian, M.; Sarbazi, E.; Allahyari, A.; Vaez, H. Polypharmacy in older adults. Int. J. Drug Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 2, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.Y.K. Interaction between warfarin and danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza). Ann. Pharmacother. 2001, 35, 501–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Fan, X.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y. Herb-drug interactions in oncology: Mechanisms and risk prediction. Chin. Med. 2025, 20, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.C.; Zhao, M.; Song, S. Online health information seeking behaviors among older adults: Systematic scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e34790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.; Li, W.; Xin, X.; Wang, J. Strategies for assessing health information credibility among older social media users in China: A qualitative study. Health Commun. 2024, 39, 2767–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivion, M.; Reid, V.; Dubé, E.; Gagneur, A.; Farrands, A.; Lemaire, C.; Baron, G.; Guay, M. How older adults manage misinformation and information overload: Qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Dong, Q.; Sun, Q.; Dong, H.; Bu, X.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Liu, C. Trajectories and influencing factors of online health information–seeking behaviors among community-dwelling older adults: Longitudinal mixed methods study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e77549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neha, F.; Bhati, D.; Shukla, D.K. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) in Healthcare: A Comprehensive Review. AI 2025, 6, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amugongo, L.M.; Mascheroni, P.; Brooks, S.; Doering, S.; Seidel, J. Retrieval augmented generation for large language models in healthcare: A systematic review. PLoS Digit. Health 2025, 4, e0000877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y. Improving large language model applications in medical and nursing domains with retrieval-augmented generation: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e80557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo El-Enen, M.; Saad, S.; Nazmy, T. A survey on retrieval-augmented generation models for healthcare applications. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 28191–28267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Ning, Y.; Keppo, E.; Ngiam, K.Y.; Bibault, J.E.; Feng, M. Retrieval-augmented generation for generative artificial intelligence in health care. npj Health Syst. 2025, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Baek, J.; Cho, S.; Hwang, S.J.; Park, J.C. Adaptive-RAG: Learning to Adapt Retrieval-Augmented Generation to Query Complexity. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), Mexico City, Mexico, 16–21 June 2024; pp. 7015–7033. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Huang, W.C.; Wu, Y.; Luo, J.; Bei, Y.; Zou, H.P.; Luo, X.; Zhao, Y.; et al. A Survey of RAG-Reasoning Systems in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2025, Suzhou, China, 4–9 November 2025; pp. 12120–12145. [Google Scholar]

- Kozhipuram, V.A.; Shailendra, S.; Kadel, R. Retrieval-Augmented Generation vs. baseline LLMs: A Multi-metric evaluation for knowledge-intensive content. Information 2025, 16, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, N.; Frieske, R.; Yu, T.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; Ishii, E.; Bang, Y.J.; Madotto, A.; Fung, P. Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yu, W.; Ma, W.; Zhong, W.; Feng, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Peng, W.; Feng, X.; Qin, B.; et al. A Survey on Hallucination in Large Language Models: Principles, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Open Questions. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2025, 43, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Q.; Havaldar, S.; Stein, A.; Zhang, L.; Rao, S.; Wong, E.; Sayeed, A.; Callison-Burch, C. Faithful chain-of-thought reasoning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.13379. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–12 December 2020; pp. 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Karpukhin, V.; Oguz, B.; Min, S.; Lewis, P.; Ledgi, L.; Wu, S.; Yih, W.T. Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 6769–6781. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, N.; Reimers, N.; Rücklé, A.; Srivastava, A.; Gurevych, I. BEIR: A Heterogenous Benchmark for Zero-shot Evaluation of Information Retrieval Models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:arXiv:2104.08663. [Google Scholar]

- Yasunaga, M.; Bosselut, A.; Ren, H.; Zhang, X.; Manning, C.D.; Liang, P.; Leskovec, J. Deep Bidirectional Language-Knowledge Graph Pretraining. In Proceedings of the 36th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2022), New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Edge, D.; Trinh, H.; Cheng, N.; Bradley, J.; Chao, A.; Mody, A.; Truitt, S.; Larson, J. From local to global: A graph RAG approach to query-focused summarization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.16130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Yue, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Guo, Q.; Hu, X.; Tang, X.; Zhang, T.; et al. Survey on factuality in large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.07521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traag, V.A.; Waltman, L.; van Eck, N.J. From Louvain to Leiden: Guaranteeing well-connected communities. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.K.; Wang, H.H. An innovative RAG framework for stage-specific knowledge translation. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, J.; Yu, D.; Du, N.; Shafran, I.; Narasimhan, K.; Cao, Y. ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schick, T.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Dessi, R.; Raileanu, R.; Lomeli, M.; Hambro, E.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Cancedda, N.; Scialom, T. Toolformer: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Use Tools. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, K.; Tu, T.; Gottweis, J.; Sayres, R.; Wulczyn, E.; Amin, M.; Hou, L.; Clark, K.; Pfohl, S.R.; Cole-Lewis, H.; et al. Toward expert-level medical question answering with large language models. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamdani, E.H.; Assilian, S. An experiment in linguistic synthesis with a fuzzy logic controller. Int. J. Man-Mach. Stud. 1975, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: A pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlsby, N.; Giurgiu, A.; Jastrzebski, S.; Brunskill, B.; Choromanski, K.; Silva, R.; von Mattern, F.; Gelly, S. Parameter-Efficient Transfer Learning for NLP. In Proceedings of the 36 th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 2790–2799. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J.; Ruder, S. Universal Language Model Fine-Tuning for Text Classification. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Long Papers), Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 328–339. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Chen, J.; Fu, J.; Wan, X.; et al. Huatuo-26M, a Large-scale Chinese Medical QA Dataset. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2025, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 29 April–4 May 2025; pp. 3828–3848. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Tian, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chawla, N.V.; Laurent, T.; LeCun, Y.; Bresson, X.; Hooi, B. G-Retriever: Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Textual Graph Understanding and Question Answering. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 37 (NeurIPS 2024), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024; pp. 132876–132907. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhu, J.; Qi, Y.; Chen, J.; Xu, M.; Menolascina, F.; Jin, Y.; Grau, V. Medical Graph RAG: Evidence-based Medical Large Language Model via Graph Retrieval-Augmented Generation. In Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Vienna, Austria, 27 July–1 August 2025; pp. 28443–28467. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.