Abstract

The article reports on a bilingual and interpretable book recommendation platform for schoolchildren. This platform uses a lightweight K-Nearest Neighbors algorithm combined with gamification and learning analytics. This application has been designed for a bilingual learning environment in Kazakhstan, supporting learning in Kazakh and Russian languages, and is intended to improve reading engagement through culturally adjusted personalization. The recommendation engine combines content and collaborative filtering in that it leverages structured book data (genres, target age ranges, authors, languages, and semantics) and learner attributes (language of instruction, preferences, and learner history). A hybrid ranking function combines the similarity to the user and the item similarity to produce top-N recommendations, whereas gamification elements (points, achievements, and reading challenges) are used to foster sustained activity.Teacher dashboards show learners’ overall reading activity and progress through real-time data visualization. The initial calibration of the model was carried out using an open-source book collection consisting of 5197 items. Thereafter, the model was modified for a curated bilingual collection of 600 books intended for use in educational institutions in the Kazakh and Russian languages. The validation experiment was carried out on a pilot test involving 156 children. The experimental outcome suggests a stable level of recommendation in terms of the Precision@10 and Recall@10 values of 0.71 and 0.63 respectively. The computational complexity remained low. Moreover, the bilingual normalization technique increased the relevance of recommendations of non-majority language items by 12.4%. In conclusion, the proposed approach presents a scalable and transparent framework for AI-assisted reading personalization in bilingual e-learning systems. Future research will focus on transparent recommendation interfaces and more adaptive learner modeling.

1. Introduction

In today’s fast-paced digital paradigm shift scenario, encouraging critical thinking skills and ensuring constant reading interests among school-going children have become prime learning demands. Conventional education systems continue to focus on knowledge creation and reproduction as their primary objectives, meaning often there is no scope to develop the advanced cognitive skills necessary for 21st century learners. This is largely true for reading outside of classroom environments, where there is often a lack of relevance to the interests of students, leading to the disengagement of learners and scattered learning paths among children [1,2].

Existing studies have consistently shown that personalized reading experiences play a crucial role in improving motivational, cognitive, and sustained engagement outcomes among learners, especially among the young generation [1]. Additionally, studies examining digital reading adoption patterns show that relevance and usefulness perceptions have a stronger effect than interface usability alone, indicating the importance of intelligent content selection and recommendation tools [2].

In light of these challenges, there has been an increased need to incorporate AI-based technologies and gamification techniques into education systems around the world. Since AI-based recommender systems contribute to the recommendation of adaptive content based on users’ behavior patterns, gamification techniques such as points, badges, levels, and challenges have been shown to promote greater motivation among learners and participation in learning tasks [3,4]. In an education setting, these techniques not only improve motivation, but also promote the development of analytical skills within learners.

Within the multilingual and multicultural learning and teaching environments found in Kazakhstan and various other countries, AI-assisted recommendation systems also have immense potential to enhance the inclusion and equality of learning processes. Bilingual approaches to learning personalization, taking into account the language of instruction and learners’ language preferences (Kazakh and Russian), are paramount in making learning innovative and inclusive. However, despite significant advances in book recommendation studies, involving collaborative filtering, hybrid models, and deep learning models [5,6,7], many existing systems remain computationally intensive and difficult to interpret.

Within bilingual educational settings, personalization not only involves the technical problem of tagging and translating content, but is also an educational and cognitive challenge. Bilingual education studies and cognitive science studies suggest that understanding and motivation for bilingual learners depend on linguistic accessibility, cognitive load, and the consistency of the target language presentation, so bilingual learning systems should not treat the two languages equivalently in recommendations and feedback. From the point of view of translanguaging, bilingual learners could easily switch between two languages, but educational systems should guaranty the developmental suitability and educational relevance of recommendations with respect to the target learner’s language of education and reading literacy. In this work, we take a pragmatic position, considering bilingual normalization as an integral design component balancing bilingualism-induced bias and providing fair visibility of Kazakh and Russian content, while preserving interpretability and low computational complexity for deployment in educational settings. Based on the above, bilingual personalization in our system will be considered not only an interface localization, but rather an educationally informed recommendation constraint that balances inclusion and relevance in extracurricular reading.

This paper will describe the design of a bilingual KNN-based book-suggesting system that seeks to overcome the issues involved in personalizing extracurricular reading for school-going children. The developed system will incorporate both content-based filtering and collaborative filtering approaches that consider both structured information about books, along with learner-specific information, for the provision of recommended books that are both age-friendly and linguistically relevant. The rationale for using the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) approach for the design of the above-mentioned system can be attributed to the fact that KNN is transparent, computationally efficient, and proven in the context of educational recommendation systems [8].

In addition to making learning more engaging for students, the recommendation tool can be coupled with a gamification interface that uses points, badges, and reading challenges based on individual reading levels. At the same time, learning analysis tools provide teachers with aggregated real-time data on students’ reading engagement patterns.

This document continues the research initiated within the framework of the national project “Development of an Intelligent Educational Resource for the Formation of Critical Thinking Skills among Schoolchildren” (BR24993072), supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan. The proposed system, which incorporates personalization, the adaptation of bilingual content, gamification, and analytics in an educational environment, fulfills the demand for local e-reading systems and thus contributes to the development of an extracurricular reading culture.

However, several significant gaps and challenges have not been adequately addressed in educational recommendation systems, especially in bilingual educational environments. First, the majority of the current approaches focus on deep learning models or graph-based models for better predictive accuracy, often to the detriment of interpretability, efficiency, and deployability. Second, bilingual/multilingual aspects have been implicitly addressed by translation or language-agnostic embeddings, without explicitly dealing with bilingual/multilingual biases in calculating similarity and content ranking. As such, educational content in non-majority languages can potentially have systematically reduced visibility, undermining the principles of inclusiveness and educational relevance. Third, bilingual/multilingual educational recommendation systems have never been developed to holistically combine personalized recommendations, bilingual/multilingual adaptation, and gamification. This research aims to fill these gaps by developing and presenting an interpretable and lightweight bilingual recommendation system that holistically addresses bilingual normalization, hybridized similarity computation, and engagement design.

Unlike many existing educational recommendation systems that have focused on the novelty of the algorithm or the improvement of accuracy, this research positions itself in the area of an interpretable bilingual educational recommendation system. The main point of this research is not the novelty of the recommendatory algorithm itself but the integration of the concepts of interpretation, bilingual normalization, and educational constraints.

Language bias can implicitly arise during similarity calculation in bilingual educational settings, and this can systematically result in the under-recommendation of content in non-majority languages. In order to address the aforementioned challenge, bilingual normalization should be considered a core design principle and not a secondary preprocessing task. This will ensure that the design at the framework level affects similarity estimation, representation, and ranking. In this respect, the system will demonstrate the effective adaptation of transparent and resource-efficient recommender systems in bilingual educational settings.

The remainder of this paper will be structured as follows. Section 2 will introduce existing research efforts on AI-based recommender systems, bilingual education tools, and gamification-based learning. Section 3 will outline the proposed architecture and framework of the system that involves data processing, followed by a KNN-based recommendation model. Section 4 will discuss the design and results of the experiment. Section 5 will elaborate on some of the current challenges, theoretical implications, and directions for future research on the matters of explainability in AI.

2. Related Work

The integration of artificial intelligence technologies in education technology has marked a significant era aimed at enhancing personalized learning experience opportunities, where intelligent recommender systems form a key part of these technologies. During the past two decades, these systems have been developed extensively, ranging in applications from digital libraries to learning environments. In relation to school-level education, recommendations systems are increasingly being explored concerning opportunities to enhance engagement levels, reading literacy, and personalized learning opportunities for learners.

However, the state of the art has examined the entire range of methods for educational recommendation, from collaborative and content filtering, through hybrid methods, to more recent approaches using deep learning and semantic modeling. There has also been considerable focus on gamification for motivation or on learning analytics for the analysis and support of student activities. Moreover, with the increasing reach of e-learning in diverse language environments, bilingual or multilingual systems for educational recommendation are being explored.

Although these developments have been achieved, several issues still exist regarding the interpretability, compatibility with school infrastructure, and relevance to younger students of these developments. The following sections provide a specific literature review on current developments surrounding key areas essential to developing the proposed bilingual KNN-based book recommendation system.

2.1. Book Recommendation Systems in Education

Book recommendation systems have long been used in academic and library settings, primarily to optimize circulation and collection management. For example, Khademizadeh et al. used collaborative item-based filtering and rule extraction to model borrowing behavior in large-scale library datasets, demonstrating the feasibility of computer-assisted book recommendation in academic libraries [9]. Similarly, Tsuji et al. applied support vector machines to bibliographic and circulation data to improve the accuracy of recommendations for university students, highlighting the value of integrating user behavior with bibliographic features [10]. Despite their effectiveness in improving system efficiency, these early approaches showed limited educational relevance.

With the expansion of e-learning environments, recommender systems gradually shifted their focus from system-centric optimization to learner-centered support. González Crespo et al. proposed an intelligent e-book system that delivers dynamic content suggestions based on user input, with the aim of helping readers within online learning environments [4]. This work represents an early step toward positioning recommender systems as tools for supporting learning-oriented reading rather than simple content retrieval.

Recent research has further expanded the conceptual and technical foundations of book recommendations. Lee et al. demonstrated that incorporating multimodal features, such as textual reviews and book cover images, can improve satisfaction prediction [11]. Complementarily, Liu et al. showed that the sentiment analysis of user reviews can uncover key evaluative dimensions of educational materials, emphasizing the role of nuanced textual signals in understanding reading intentions [12].

Beyond algorithmic innovation, several studies have examined the epistemological assumptions embedded in recommendation practices. Pattee analyzed professional discourse in library recommendations and illustrated how the notion of a “hypothetical adolescent” is constructed through adult-oriented recommendation criteria, revealing implicit normative biases [13]. These findings support a shift from norm-based recommendation models toward learner-centric approaches that better reflect individual reading contexts.

More recently, large language models (LLMs) have been explored to automate book evaluation and assessment tasks. Liu analyzed GPT-generated scholarly book reviews and concluded that despite rhetorical fluency, LLMs fail to capture deeper contextual understanding [14]. Similarly, Thelwall and Cox reported weak correlations between ChatGPT-generated book scores and citation-based impact measures, questioning the reliability of such models for educational recommendation [15]. These findings reinforce the importance of behavior-driven and interaction-based models when recommending reading materials to learners.

Finally, artificial intelligence has also been applied to broader library infrastructure tasks. Sokil and Andrukhiv investigated the use of autonomous AI agents, such as AutoGPT and AgentGPT, to automate cataloging and acquisition processes, indicating a growing interest in AI-supported library management [16]. Although such approaches primarily target operational efficiency, they reflect a broader shift toward intelligent support systems within library ecosystems.

Together, these studies indicate an ongoing transition from operationally focused recommendation systems to pedagogically informed approaches that prioritize learner behavior, content relevance, and contextual factors in reading development.

2.2. Hybrid and KNN-Based Recommendation Approaches

Recent advances in book recommendation research have enabled the development of hybrid models that combine collaborative filtering with deep semantic representations and attention mechanisms. In particular, graph-based and deep learning approaches have gained popularity because of their strong predictive performance.

For example, Xiao et al. proposed a collaborative knowledge-aware recommendation model using multi-relational attention modeling and user interest [17]. Similarly, Sun introduced a graph convolutional network (GCN)-based model to represent interactions among readers, books, and knowledge points [18]. Although these approaches demonstrate high accuracy, their structural complexity and computational demands limit their suitability for educational environments where interpretability and efficiency are essential.

Deep hybrid architectures have also been extensively explored. Gao presented a transformer-based hybrid model that incorporates self-attention mechanisms [19], while Shi et al. combined attention mechanisms with CNN-based features and factorization machines [7]. More complex deep models, such as SKGRec [20], Wide&Deep [21], and DPBD based on temporal modeling [22], further improve recall and accuracy. However, despite their performance advantages, these architectures are often difficult to deploy in school contexts due to their limited transparency and high computational overhead.

Several hybrid recommendation approaches have been developed specifically for library applications. Verma and Patnaik proposed a fuzzy ranking method integrating collaborative, content-based, and temporal features through a Hidden Markov framework [6]. Ifada et al. addressed data sparsity using collaborative techniques based on probabilistic keywords [5], while Chen et al. introduced a feature fusion approach that maps book categories and user attributes into a shared vector space [23]. Sarkar further proposed a multi-dimensional hybrid model that incorporates temporal patterns to improve ranking performance in library systems [24]. Although effective in transactional domains, these approaches do not explicitly address learner-centric personalization or educational objectives.

More recent studies have explored hybrid strategies based on clustering. Amin et al. combined K-means clustering with association rule mining to improve the accuracy of recommendation [25], while Ji introduced a time-aware hybrid model integrating temporal borrowing information, latent features, and clustering techniques [26]. Although these methods mitigate cold start issues, they primarily operate on aggregate behavioral patterns and offer limited support for real-time learning adaptation.

Additional techniques include BERT-based group recommendation models [27], sentiment-aware, category-based approaches to enhance serendipity [28], and cross-domain architectures combining BERT and CNN representations [29]. Despite their potential, these models are typically domain specific, data intensive, and architecturally complex, restricting their transferability to resource-constrained educational settings.

In contrast, the proposed system adopts a lightweight and interpretable K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)-based hybrid approach. By combining content-based features (e.g., genre, age range, and instructional language) with learner attributes (e.g., preferences and reading history), the model achieves effective personalization while maintaining transparency and computational efficiency. These characteristics make KNN particularly suitable for school environments and accessible to non-technical educational stakeholders. A concise comparison between contemporary hybrid techniques and the proposed KNN-based approach is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of KNN-based approach with recent hybrid recommendation models.

2.3. Bilingual and Multilingual Recommender Systems

As AI technologies become increasingly embedded in educational environments, the demand for bilingual and multilingual personalization has grown, particularly in multilingual contexts such as Kazakhstan. Although direct research on bilingual book recommendation algorithms remains limited, a growing body of interdisciplinary work provides important insights into AI-supported bilingual learning environments that inform recommender system designs.

Recent studies have explored the use of large language models and generative AI in bilingual education. Xiao et al. investigated a bilingual conversational AI powered by a large language model within an interactive English-as-a-foreign-language e-book, demonstrating that AI-supported bilingual dialogue can enhance early literacy and dialogic reading practices [30]. Similarly, Liu et al. examined the application of ChatGPT-4o and DeepSeek-v3 models in bilingual asthma education, highlighting advantages related to clarity, linguistic flexibility, and domain-specific precision [31].

Beyond conversational agents, Chang and Sun analyzed multimodal generative AI tools—including text generation, visual systems, and writing assistants—within adaptive bilingual educational environments [32]. Their findings emphasize the instructional potential of dynamic AI systems and outline methodological principles for real-time, adaptive recommendation in bilingual learning contexts, extending the role of AI beyond simple content dissemination.

Insights from bilingual human–computer interaction research further inform the design of educational recommender systems. Atghaei et al. demonstrated that language separation, as opposed to code mixing, can reduce cognitive load and improve comprehension in bilingual guide sign systems [33]. Although conducted in transportation settings, these findings are transferable to bilingual educational platforms, where cognitive load management is equally critical.

Interdisciplinary educational research also supports the pedagogical justification of bilingual recommendation systems. Newell et al. proposed a participatory, data-driven decision support framework integrating early reading assessment and intervention for bilingual learners, underscoring the need for context-sensitive and inclusive educational support [34]. This perspective extends naturally to recommender systems aimed at fostering equitable reading development.

Finally, studies on bilingual teacher education and curriculum design provide additional guidance. Martínez-Álvarez et al. highlighted the benefits of multimodal approaches in bilingual education, demonstrating improved learning engagement through visual and reflective instructional strategies [35]. Similarly, Scherzinger and Brahm’s systematic review of bilingual education competencies emphasized the importance of aligning instructional support with learners’ developmental and linguistic readiness [36]. These findings reinforce the need for recommendation systems that adapt not only to language preferences but also to pedagogical appropriateness.

Together, these studies demonstrate the need for integrated bilingual and multilingual recommendation systems that extend beyond technical translation or language-agnostic embedding. From an educational perspective, bilingual personalization should account for cognitive load, linguistic alignment, and instructional relevance. Treating bilinguality as a purely technical translation problem can undermine comprehension and reduce educational effectiveness, highlighting the importance of pedagogically informed bilingual normalization in educational recommender systems.

2.4. Gamification in Learning and Recommendation

Gamification is widely recognized as an effective paradigm for enhancing learner motivation, engagement, and agency across both traditional and technology-mediated educational settings. In AI-based learning environments, gamification serves a dual role: it functions as a motivational mechanism while also supporting personalized, feedback-driven, and autonomous learning processes. Within recommender systems, gamification facilitates sustained interaction and goal reinforcement by aligning recommendations with learners’ motivational states.

Empirical studies on digital reading environments demonstrate that learner engagement can be enhanced through multisensory and motivational design principles. For example, Gacumo et al. reported that the incorporation of olfactory elements into digital books increased children’s persistence and enthusiasm for reading [37]. Such findings suggest that gamification and learner-centered design principles can meaningfully enrich recommendation systems targeting young readers.

Gamified AI systems have also been explored in non-educational domains, offering transferable design insights. Assaf et al. developed a collaborative, game-based decision support system for supply chain management that promoted participation and shared situational awareness [38]. Similarly, Arif et al. proposed a decentralized recommender system embedded within a gamified tourism application, where recommendations guided scenario generation [39]. Although these applications fall outside formal education, they illustrate how recommender systems can be effectively integrated into gamified environments.

Within educational contexts, gamification has been extensively applied to support formative assessment and learner motivation. Zainuddin et al. demonstrated that a game-based electronic quiz system significantly improved student engagement and performance compared to conventional assessment methods [40]. Maimaiti and Hew further showed that a gamified self-regulated learning design combining game mechanics with learning analytics yielded sustained improvements in terms of motivation and metacognitive skills [41]. These findings highlight the potential of integrating gamification with recommendation services to support long-term learning behaviors.

Research in higher education further clarifies the conditions under which gamification supports learning. Murillo-Zamorano et al., using the “8-Pointed Gamification Star”, found that gamification enhances learning efficiency and engagement, with satisfaction indirectly mediated by learning achievement [42]. Alt reported that only problem-based digital gamification significantly influenced intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, underscoring the importance of pedagogically grounded game designs [43].

Recent work emphasizes adaptive and data-driven approaches to gamification. Hong et al. identified personalization, adaptation, and recommendation as key tailoring strategies grounded in learner modeling, highlighting the need for further research on the specific learning effects of gamified design choices [44]. Similarly, Tsay et al. demonstrated that engagement behavior in gamified online learning environments can serve as a strong predictor of academic achievement, reinforcing the role of analytics-supported personalization [45].

Cross-domain synthesis studies further stress the importance of sustainable and context-aware gamification practices. Gonçalves et al. analyzed the motivational benefits and limitations of extrinsic reward-based gamification, arguing for the systematic evaluation of its educational impact [46]. Mabalay’s comprehensive review of gamification in relation to the UN Sustainable Development Goals identified education as a primary application domain, highlighting the demand for innovative technology integration [47].

Overall, the literature indicates that gamification, when aligned with pedagogical models and learning design, can substantially enhance recommender systems in educational settings. Rather than treating gamification as an auxiliary feature, future research should focus on its dynamic integration with learner progress, motivation, and personalized recommendation strategies.

2.5. Learning Analytics and Adaptive Feedback

The integration of learning analytics with adaptive feedback delivery is a defining characteristic of contemporary AI-based educational platforms. These approaches enable dynamic personalization, real-time monitoring, and pedagogically informed responses. In the context of intelligent book recommendation systems, learning analytics support not only content alignment but also motivation tracking and adaptive feedback, which are particularly relevant for extracurricular reading activities.

Several studies demonstrate the effectiveness of analytics-driven recommendation designs. Tavakoli et al. proposed an open learning recommender system aligned with labor market requirements, showing that learning analytics can enhance personalization and learning-related outcomes in goal-oriented learning scenarios [48]. Similarly, Lalitha and Sreeja emphasized learner autonomy by designing a recommendation system that adapts to students’ cognitive and strategic profiles, reinforcing the role of adaptability in self-directed learning environments [49]. Complementarily, Liu et al. explored adaptive recommendation in child–robot interaction using Bayesian inference and fuzzy natural language processing to adjust content in real time according to children’s interests [50].

From a pedagogical perspective, multimodal learning has been shown to support adaptive engagement, particularly in bilingual contexts. Martínez-Álvarez et al. argued that multimodal curriculum mediation transforms learning environments into reflective hybrid spaces, underscoring the importance of feedback mechanisms that adapt to individual learning styles [35]. Sustainability-oriented research further supports this view. Bagherimajd and Khajedad proposed a meta-synthesized model of sustainable AI-based education, identifying personalized feedback and adaptive learning as core dimensions with direct implications for recommendation-driven reading support [51].

Conversational interfaces and generative models have recently expanded the scope of adaptive feedback. El Mourabit et al. conducted a large-scale analysis of AI-powered chatbots in higher education, demonstrating their potential to personalize content and learner support [52]. Martínez-Araneda et al. examined generative AI feedback in programming education and reported high usability and acceptance, even though measurable learning gains were not consistently observed [53]. These findings highlight both the promise and limitations of generative feedback when deployed without carefully designed pedagogical frameworks.

Additional studies reinforce the importance of pedagogically informed implementation. Breideband et al. developed the CoBi system for visualizing classroom discourse to support pupils’ reflections, emphasizing coherence between AI functionality and instructional design [54]. Similarly, Naz and Robertson showed that ChatGPT-3 can support second language acquisition when embedded within a framework that includes teacher supervision and adaptive logic, but performs inadequately as a standalone instructional agent [55].

Beyond feedback delivery, adaptive learning models increasingly rely on multidimensional learner modeling. Sayed et al. proposed an adaptive learning framework for K–12 education that integrates cognitive, behavioral, and affective learner dimensions, demonstrating improvements in learner satisfaction and effectiveness, particularly among low-achieving students [56]. In library recommendation contexts, Yang introduced a hybrid fuzzy and deep learning framework for LILRRF, achieving notable performance gains over traditional methods [57]. Zhao et al. further reviewed generative recommender systems, identifying the substantial engineering challenges associated with deploying large language models in recommendation pipelines [58].

Taken together, these studies illustrate a clear shift from static recommendation approaches toward interactive, analytics-driven, and pedagogically integrated systems. At the same time, they reveal persistent trade-offs between predictive performance and practical applicability in educational contexts. While deep learning and graph-based models often achieve superior accuracy in large-scale commercial settings, their computational complexity and limited interpretability constrain their deployment in school environments.

Moreover, despite the growing interest in multilingual and language-agnostic embeddings, language-induced bias and bilingual fairness remain underexplored. Most existing approaches address language diversity implicitly rather than incorporating it directly into similarity computation and ranking mechanisms. These gaps motivate the development of the proposed lightweight, learner-centric, and bilingual-aware recommendation framework based on KNN, which is described in the following section.

3. Materials and Methods

The proposed intelligent recommendation approach will be incorporated into a bilingual educational platform intended for developing personalized reading experiences, along with cultivating critical thinking in schoolchildren. Its main advantage is the use of artificial intelligence techniques for content adaptation, combined with a gamification approach. At its core, the proposed platform will use a K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm, on top of which the recommendation approach will be established. This section will outline the proposed main system framework, its data representation scheme, the problem formulation of the proposed approach, as well as the performance evaluation method through aggregated interaction measures.

3.1. System Architecture

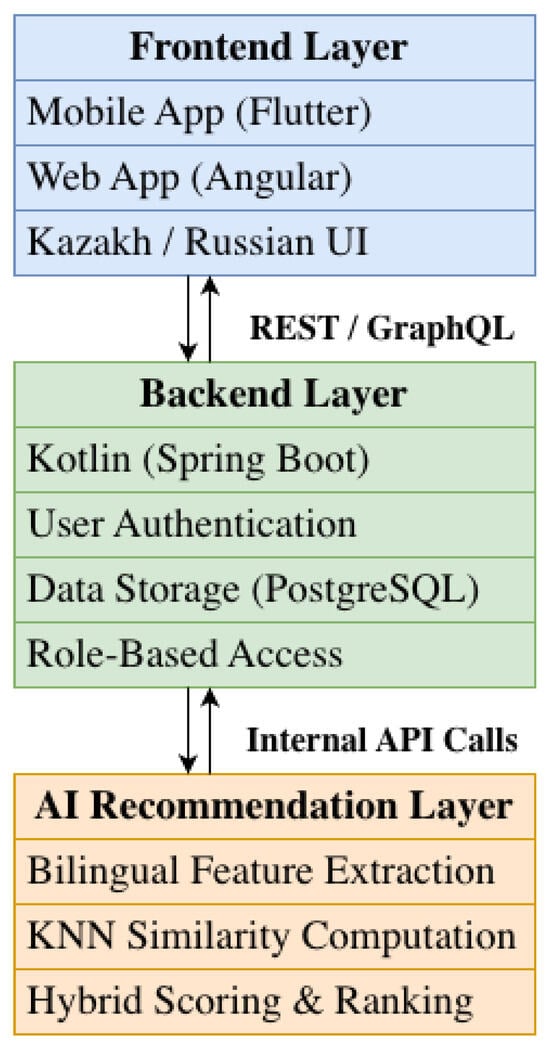

The architecture of this system is described in terms of the following three major layers (as depicted in Figure 1):

Figure 1.

System architecture of the bilingual book recommendation system, illustrating user inputs from frontend interfaces, interaction with backend services, and the generation of personalized book recommendations by the AI recommendation engine.

- 1.

- Frontend layer;

- 2.

- Backend layer;

- 3.

- AI recommendation layer.

The frontend layer consists of an Angular-built online interface and a Flutter-developed mobile application that is cross-platform and supports both Kazakh and Russian languages to be fully inclusive of the bilingual environs of Kazakhstan.

The backend layer developed in Kotlin and utilizing Spring Boot is responsible for user authentication and proper communication between components of this system, ensuring proper role-based access for all possible users, including differing access for teachers, students, and admin.

The artificial intelligence suggestion level is responsible for bilingual extract and similarity comparison, as well as the ranking of book recommendations. This AI module also communicates with the backend via API endpoints. All structured data, including user profiles, reading activities, and book entries, reside persistingly on a PostgreSQL database environment which supports multilingual indexing and optimized queries.

3.2. Data Sources and Datasets

Three different data sources have been used to design, modify, and test the bilingual recommended book system.

Firstly, an open-access public book recommendation dataset with 5197 records of books was used in calibrating and validating the model initiated through the KNN approach. The dataset offered generic book information and interaction and did not specialize in an educational setting.

Second, a well-filtered bilingual corpus of 600 books was designed in both Kazakh and Russian languages by the authors. This corpus incorporates educationally relevant features, such as genre, age range, language, author, and brief semantic descriptions, mirroring the national curriculum requirements for reading in schools.

Thirdly, anonymized and aggregated interaction data were collected in a pilot deployment among 156 schoolchildren. This set of data includes variables like reading completion, interaction with the recommended items, and participation in gamified activities. Student-level data were not analyzed or stored.

3.3. Data Structure and Feature Representation

The suggested recommendation system relies on an organized form that captures the aggregate interactions of students with reading materials within the bilingual education platform. Specifically, the dataset can be formally defined by the following:

where denotes a user (also a student), symbolically represents a book item, and denotes the observed interaction between user and book item . Note that the interaction signal is derived from anonymized, aggregated, and processed feedback, encompassing both explicit cues (e.g., ratings) and implicit cues (e.g., reading completion, engagement time, quiz participation, and interaction events).

3.3.1. Book Feature Representation

In the current setting, each book is represented by the following feature vector , as defined in Equation (2).

where each component encodes a distinct pedagogical or semantic attribute, as follows:

- is a genre vector, represented through a multi-hot or weighted approach to reflect those texts that encompass more than one genre category, like fiction, science, and history;

- represents the author’s vector, which is learned based on co-occurrence patterns or through pre-trained semantic models to identify thematic links between authors;

- represents the target age value or recommended age range that has been normalized to be consistent with the learner’s grade levels;

- is used for encoding the language of the book (Kazakh or Russian) in a categorical or binary form, which is necessary for bilingual personalization and language-specific recommendations;

- represents the semantic embedding of the book description, achieved through language-specific or cross-lingual text embedding models;

- is the aggregated average rating or quality score based on the historical usage pattern, and provides a global popularity and quality indication.

The structured representation strikes a balance between expressing semantics and efficiency in computation, making it possible to compute similarities in an interpretable way by forgoing the complexities of deep learning architecture.

3.3.2. User Feature Representation

Each user is represented by a personalized feature vector , constructed from anonymized and aggregated interaction indicators, as defined in Equation (3).

where each item is defined as follows:

- represents the learner’s preferred instructional language, which plays a key role in bilingual recommendation and content filtering;

- captures genre preferences inferred from past reading interaction data;

- represents the learner’s class or grade level and is used as a proxy for reading ability;

- represents past reading behavior based on aggregated engagement measures, including reading completion, interaction frequency, and participation in learning activities, normalized in the learner population.

This representation enables personalization aligned with cognitive level, linguistic context, and expressed interests, which are critical considerations when designing recommender systems for school-aged children.

Demographic attributes such as gender were intentionally excluded from the final model to avoid introducing potential bias and to ensure that recommendations are driven solely by educationally relevant and behavior-based features.

3.3.3. Bilingual Normalization as a Core Design Component

Systemic biases can arise in bilingual educational environments due to variations in linguistic resources, corpus size, and semantic representation. These biases could potentially lead to reduced visibility for content in languages that are not dominant. As such, bilingual normalization within the system being proposed will not only be viewed as a preprocessing task, it will also have a direct impact on the system’s recommendation and fairness.

All the textual features, such as book descriptions, are subject to language normalization, tokenization, as well as the removal of stop words. The semantic features are processed by employing language-aware embedding techniques, and when the need arises, they can be transformed into a common vector space to facilitate comparison between the content of the Kazakh and Russian sources.

By including bilingual normalization as part of its similarity measurement process, it helps to ensure language distortion is eliminated in distance measurement while also ensuring the equal coverage of content in both languages. This is especially important in learning institutions where language equity is a key aspect.

Although the use of sophisticated multilingual models based on the transformer architecture might provide a more detailed linguistic form of knowledge, their computational complexity and associated infrastructural and interpretability issues might not be feasible in an educational context at the school level. Thus, the proposed system will incorporate a cross-lingual semantic mapping solution that will focus on interpretability and efficiency in addition to control in an educational context. The normalization of the linguistic form of knowledge will be performed using language-aware preprocessing and alignment of the embedding space in a common semantic space that will allow similarity measurements while considering language-specific constraints in an educational context.

3.3.4. Design Rationale

These structure and representation of data are based on three basic design elements:

- 1.

- Interpretability: Features provide semantic meaningfulness and traceability, allowing instructors to understand and trust the results of suggestions.

- 2.

- Educational Relevance: “User” and “item” feature sets explicitly include educational attributes like age, language, and reading behavior.

- 3.

- Computational Efficiency: The vector representation system is efficient for similarity computation within the KNN framework, making it school infrastructure compatible.

Taken together, these provide a solid starting point for the hybrid KNN-based recommendation modeling presented in the following subsections.

3.4. KNN-Based Recommendation Model

The essential building block of the proposed recommendation system is a hybrid K-Nearest Neighbor algorithm that merges similarity measures based on users and items. The reason for choosing such an architecture is that it is interpretable, efficient, and suitable for a bilingual learning environment with limited resources.

3.4.1. User/User Similarity via Weighted Cosine Distance

In order to determine the similarity between two users, and , a weighted version of the cosine similarity measure is used, based on the vectors mentioned in Section 3.2:

where

- and are referred to as the n-th normalized feature value for users and , respectively;

- represents a weight given either directly or heuristically in an attempt to reflect the relevancy of each particular variable (for instance, genre preferences could be weighted more than language, which could be weighted more than grade);

- N is the number of user features used in calculating the similarity.

Justification: This allows for the domain-specific weighting of features. In the context of a bilingual education environment, alignment with genre might be an even better prediction of user preference than alignment with grade level; however, language compatibility is still important for accessibility purposes.

3.4.2. User-Based Rating Prediction

After calculating the similarity between users, another task of this model is to estimate the predicted rates or interactions of each user towards book , based on the preferences of his/her most similar neighbors. This can be modeled as follows:

where

- is the predicted rating or engagement likelihood for book by user , based on neighbor feedback;

- denotes the set of top-k most similar users (or neighbors) to ;

- is the observed feedback for user on book (if available).

Interpretation: “The proposed formulation captures social affinity based on the assumption that individuals with similar profiles have corresponding preferences. This formulation is most useful during the early stages of usage when the amount of individual feedback is limited but information about peer patterns is available”.

3.4.3. Hybrid Recommendation Score: Combining User- and Item-Based Signals

To overcome the weaknesses of purely user-based or item-based methods, for example, the problem of cold start and popularity bias, this study uses a weighted hybridization approach incorporating both sources of data:

where

- is the predicted engagement based upon item–item similarity. This is calculated in a similar fashion to user–user similarity from Equation (4), except that it is computed for item (book) vectors;

- is a parameter that controls how much personalization (user-based) and content features (item-based) are considered.

Example: A value of favors a peer-based personalization approach, while favors a content similarity-based approach when the amount of user interaction information is small.

3.4.4. Pedagogical and Technical Justification

- The k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm works well in an academic setting where transparency is a key requirement for the human understanding of recommendations made by an algorithm;

- The hybrid model improves the robustness in the cold start setting for introduced users or books without interaction history;

- The use of weighted cosine similarity helps to ensure that the recommendation is bilingual, age related, and interest based;

- The system retains low computational complexity, thus allowing the use of school-level computational power instead of cloud-based deep learning capabilities.

3.5. Gamification Layer and User Engagement Tracking

To better support learner interest, maintain reading engagement, and promote autonomous learning participation, a gamification aspect is also included within the recommendation system. From a theoretical basis, the gamification aspect is supported by the tenets of Self-Determination Theory and constructivist learning, addressing the existing system with the additional aspect in a complementary manner to better pursue desired learner behaviors.

3.5.1. Gamification Elements and Mechanics

Gamification layer: This layer has different gamification components which are based on mapping reading activity to reward-based challenges. The components are as follows:

- Points System: Those participating can earn points for action items like opening a recommended text, turning over a certain number of pages, completing a text, or giving feedback. Points can be set based on the difficulty level and relevance of the recommended material;

- Badges and Achievements: Badges are earned when specific milestones are attained, for example, “First Book Completed”, “Five books in target language”, or “Top genre explorer”. This is intended to be encouraging visual reinforcement of intrinsic motivation;

- Reading Challenges/Missions: This platform comes up with time-bound missions to read certain books along with a certain theme (e.g., “Read three fantasy books this month” and “Read a Kazakh-language book this week”). These reading missions are designed according to the learning profile of the reader;

- Leaderboards (Optional): Optional leader boards help learners assess their progress alongside other learners in a non-competitive manner. Data indicating comparisons is carefully balanced to avoid overemphasization and ensure that no one is left out.

3.5.2. Integration with Recommendation Engine

The gamification framework is tightly coupled within the recommendation system by the following means:

- Reward Weights for Relevance: The weightage of rewards for reading suggested books would be higher than that for books selected randomly. This approach would encourage participants to read suggested books and also promote the credibility of the recommendations system;

- Challenge Generation: The reading challenges are partly formulated on the basis of previous reading behaviors and the recommended vectors. For instance, if a person is a fan of Russian books, then a recommended challenge could be to read books in Kazakh to promote bilingual proficiency;

- Feedback Loop into the Recommendation Layer: The gamified interactions (e.g., ratings of a book, completing a challenge, or skipping a video) are taken into consideration in the profile of user behavior.

3.5.3. User Engagement Tracking and Analytics

Real-time user engagement monitoring is incorporated into the system, with a module that aggregates data on user interaction at the micro and macro levels. Data collected using the module includes the following metrics:

- Session length and reading time;

- Book completion rates;

- Challenge participation and success rates;

- Reactions to recommendations (e.g., accept, skip, and delay);

- Preferred language based on user engagement.

Such performance measures are retained in the backend and then displayed periodically on dashboards to monitor performance either by the learners themselves or the lecturers.

3.5.4. Pedagogical Justification and Design Considerations

The gamification approach is pedagogically integrated with formative assessment because immediate feedback and the observation of progress play an integral part in self-regulated learning. Each game function is carefully designed to supplement rather than weaken intrinsic motivation to read and thus offset the potential dangers stemming from overdependence on extrinsic motivators for reading improvement as referenced in [46,47]. Gender-neutral and culturally integrated visual components will be utilized for the purpose of accessibility and acceptability for a wide range of learning audiences. Game components may be scaled based on age/grade level for appropriateness.

3.5.5. Privacy and Ethical Safeguards

- Anonymized data for engagement tracking is stored securely with appropriate consent for participation in leader boards;

- Teachers’ and administrators’ view privileges are limited to the aggregate dashboards and do not involve user log data, and this helps ensure learner privacy.

In addition to anonymizing data, the system design tackles fairness, governance, and power dynamics in the context of AI-assisted educational settings. “All recommendations are generated as decision support recommendations, not prescriptive directives, and teachers retain complete pedagogical control over the use and application of the recommendations”. This “teacher in the loop” approach helps mitigate any imbalances in the dynamics of power among students, teachers, and the algorithmic system. “Fairness is addressed by bilingual normalization, which is integrated into similarity computation and ranking, and which helps to mitigate the systematic underrepresentation of content in non-dominant languages”. Data governance follows a minimal collection approach, where only aggregated and unidentifiable interaction data are processed, and “no decisions with educational consequences are made solely based on algorithmic output”.

3.6. Model Evaluation

To assess the efficacy of the proposed bilingual KNN-based recommendation system, a rigorous test was undertaken by combining offline quantitative analysis with aggregated behavioral feedback. Such a two-fold assessment method is imperative because it ascertains the correctness, relevancy, and utility of the system regarding supporting personalized learning.

3.6.1. Offline Evaluation Metrics

The performance of recommendation model recommendations is first assessed on test data, where a batch of observed interaction signals between users and books is withheld to resemble unseen recommendations. The traditional evaluation metrics are as follows:

Precision@k and Recall@k

where

- is defined as the top-k recommended items for user i;

- denotes items related to aggregated interaction signals, such as completion and engagement signals, for user i;

- Precision@k calculates how many of the recommended items are actually relevant, whereas Recall@k calculates how many relevant items are correctly recommended.

These metrics are especially used in top-N recommendation tasks, such as the one considered in this study, which emphasizes the most appropriate items for each learner. For experimentation, both and were considered, as they are commonly used when evaluating educational recommender systems.

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE)

where

- refers to the actual observed feedback (such as rating or completion);

- is the predicted score produced by the model;

- T is the test set containing M user–item pairs.

RMSE measures the predictive ability of the model based on continuous feedback. A smaller RMSE value implies that the estimated scores are closer to the real feedback provided by users.

3.6.2. Behavioral and Subjective Evaluation

To complement these quantitative measures, feedback from users using the app was collected using post-recommendation surveys and activity logs. The feedback variables collected were as follows:

- Personal relevance of suggested books;

- User satisfaction with reading suggestions;

- Challenge engagement and completion rates;

- Inferred language preference from selected content;

- Teacher dashboard feedback on observed student engagement.

The behavioral data has two uses:

- 1.

- It is used in model parameter optimization, specifically for k, , and weights ;

- 2.

- It helps to identify if the recommendations are matched to the students’ interest, language ability, or intellect.

All behavioral and subjective measures are examined on a group level, with no individual data reported for students.

The participation survey was conducted as an exploratory instrument intended to capture perceived relevance and usability, rather than as a validated measure of learning outcomes.

3.6.3. Parameter Tuning and Optimization

Based on the results of the evaluation, the following are the fine-tuned parameters of the model:

- k (number of neighbors), varied in the range ;

- (weight for the hybrid model), adjusted for a balanced score between the user-based and item-based methods;

- (weights for features), initialized by hand and adjusted by grid search according to domain-specific considerations (e.g., weighting genre similarity more than language).

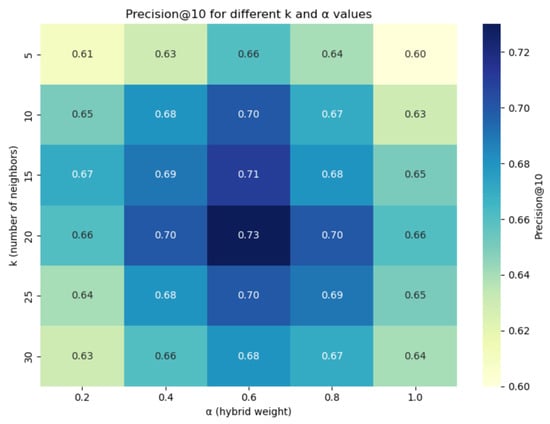

Figure 2 illustrates the Precision@10 scores under varying and k values, confirming an optimal performance at and .

Figure 2.

Sensitivity analysis of the hybrid KNN model, showing how variations in the number of neighbors (k) and the hybrid weighting parameter () affect Precision@10.

3.6.4. Baseline Models and Reproducibility Details

For a fair and reproducible comparison, the performance evaluation of all the baseline models was performed using the same datasets, preprocessing, and training and testing splits as proposed in the approach. The performance metrics were computed using the same evaluation protocols for all models.

In the collaborative filtering baseline based on the users, cosine similarity was used in the user interaction vectors. The number of neighbors was fixed at k = 20. Language-specific preprocessing was not performed except for standard tokenization.

The matrix factorization was performed under a standard latent factor model with 50 latent dimensions. The hyperparameters were optimized through a grid search for the learning rate and regularization coefficients. The model was trained until convergence with early stopping.

The neural recommender baseline was implemented as a multilayer perceptron (MLP) with two hidden layers (128 and 64 units) and ReLU activation. Dropout regularization (rate = 0.3) was applied to reduce overfitting. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001.

For the proposed hybrid KNN-based model, cosine similarity was used for user–user and item–item comparisons. The feature weights were initialized heuristically based on domain relevance, with higher weights assigned to genre preference and age compatibility, followed by language alignment. The hybrid parameter controlling the balance between user-based and item-based signals was selected through validation and set at = 0.6 in the final experiments.

These implementation details are provided to support transparency and facilitate the reproducibility of the reported results.

3.6.5. Summary of Evaluation Outcomes

As highlighted in Table 2, the system achieves robust precision, high language adaptability, and considerable user engagement during the gamified tasks.

Table 2.

Summary of model performance and engagement outcomes.

3.7. System Flow Diagram

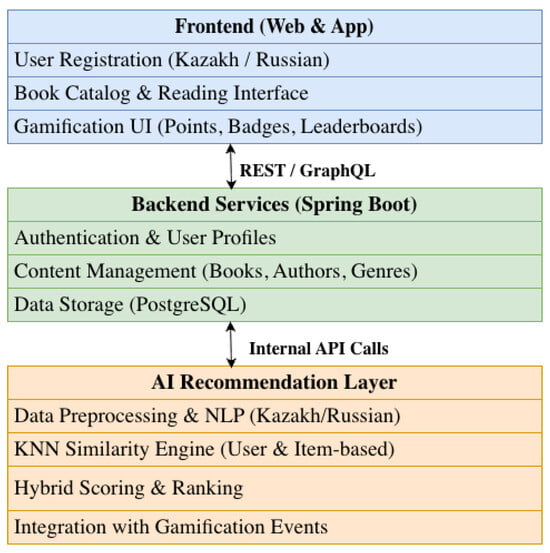

This proposed bilingual KNN-based recommendation system architectural design ensures modularity, scalability, and transparency in a way that makes it easy to integrate recommendation, gamification, and analytics features seamlessly. These system architectural layers comprise three main layers:

- 1.

- Frontend layer;

- 2.

- Backend Services Layer;

- 3.

- AI Recommendation Layer (Ref: Figure 3).

Figure 3. System flow diagram of the bilingual KNN-based recommendation platform, illustrating the flow from user interaction inputs through frontend and backend layers to the AI engine, including preprocessing, KNN-based similarity computation, scoring, and the output of ranked book recommendations.

Figure 3. System flow diagram of the bilingual KNN-based recommendation platform, illustrating the flow from user interaction inputs through frontend and backend layers to the AI engine, including preprocessing, KNN-based similarity computation, scoring, and the output of ranked book recommendations.

The layer-based structure facilitates flexible deployment and maintainable development, as well as language-dependent customizations for the Kazakh and Russian language interfaces. This also promotes appropriate real-time responsiveness, which is required for a dynamic environment like an educational setup.

3.7.1. Frontend Layer

The frontend includes a web interface that is cross-platform, implemented using the Angular framework, as well as a mobile app developed using Flutter technology. Both have the ability to be fully bilingual, allowing the display as well as the interaction to be presented in Kazakh as well as in the Russian language.

The essential functionality for end-users includes the following:

- Bilingual registration and authentication system, which includes the functionality of setting a preferred language;

- Capabilities of search and navigation within a digital library of curated content that are filtered based on appropriate age and interests;

- An interactive reading interface with the ability to annotate and track the reader’s progress;

- A gamification layer with support for points, badges, and leaderboards, as well as a visual progress mechanism;

3.7.2. Backend Services Layer

The backend is developed using Kotlin and Spring Boot technology and serves as a data orchestration gateway that connects the interface to the AI engine. Some of its functions include the folllowing:

- Providing secure authentication and role-based access control for students, teachers, and administrators;

- Handling anything relating to book metadata, genres, authors, or user profiles;

- Offering persistent storage through PostgreSQL, with multilingual indexes to support efficient search and retrieval in different languages;

- Providing REST and GraphQL APIs to enable smooth integration with frontend clients and microservices.

3.7.3. AI Recommendation Layer

Functionally, this core module provides for personalization using behavioral data, book information, and cross-language semantics. The following comprise the main functions that it provides for:

- Natural language processing (NLP) pipelines for Kazakh and Russian languages that handle tasks such as tokenization, lemmatization, and embedding creation;

- Feature extraction from user and book vectors (Section 3.3) in the calculation of personalized relevance scores;

- User- and item-based KNN similarity computation, enabling flexible adaptation to sparse datasets;

- A hybrid scoring method that combines both cooperative and content filtering approaches using a weighting parameter (Section 3.4);

- Event tracking for gamification, such as achievement detection (first book completed and explorations of different genres), milestone detection, and achievement triggering.

Additionally, this level records interaction information along with feedback for the benefit of real-time learning analytics, which helps instructors track engagement behaviors and inform their instructional design accordingly.

3.7.4. Figure and System Flow

The entire flow of information from user interaction to recommendation delivery is represented in Figure 3. It shows how user interactions in the frontend are channeled to the backend services, and eventually to the AI engine, which responds to the request with reading suggestions in both languages and by incorporating gamification elements.

4. Results and Evaluation

In this section, there is an in-depth analysis of the concept of developing a bilingual KNN recommender model. The experiment was designed to test three main areas: (1) recommendation accuracy, (2) model interpretability or efficiency, and, finally, (3) educational impact, namely learner engagement. The section that follows examines each area further.

4.1. Experimental Setup

This recommendation system was implemented and tested with real data obtained from the bilingual platform that was created during the national initiative BR24993072. Although personalized accounts were used in the platform, this study will be performed using anonymous aggregated data.

The initial calibration was conducted using an open-access book dataset that contained a total of 5197 pieces, and then the model was modified using a curated bilingual dataset that consisted of 600 Kazakh- and Russian-language books. It must be noted that the curated dataset used here is essentially the active content repository used in the deployed environment and was chosen to ensure that it was age-appropriate, relevant, and that comprehension questions/activities could be generated.

For experimental evaluation, a pilot group consisting of 156 schoolchildren aged 7 to 17 (grades 1–11) was chosen from around 1250 student accounts that were registered.

The data analyzed for this study included the following:

- Interaction data from 156 schoolchildren;

- 600 carefully selected bilingual books;

- Around 12,000 interaction records aggregated, including the following:

- −

- Reading completion events;

- −

- Interactions with recommended items;

- −

- Participation in the online quiz after the readings.

Data Preprocessing Steps

To achieve semantic consistency as well as the relevance of recommendations, the following preprocessing steps were conducted:

- The multilingual normalization of bibliographic metadata (titles and descriptions);

- TF-IDF vectorization of book summaries for semantic embedding extraction;

- Categorical encoding for genre, language, and age groups;

- Min–max normalization on numerical attributes (e.g., reading times and rating scores).

This recommendation system was developed in python using Scikit-learn. The comparison study on similarity measures was carried out with cosine similarity, Manhattan, and Euclidean, and the best one was cosine similarity. The value of k was chosen as ten after experimentation.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

The prediction accuracy and capability of the model are evaluated in relation to a conventional recommender system defined in Section 3.6 as follows:

- Precision@k: The number of relevant recommendations in the top-k recommendations.

- Recall@k: The proportion of relevant books that are correctly suggested.

- F1-score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall.

- RMSE: The root mean squared error of rating predictions.

In addition, a user-centered assessment was conducted, which entailed the following:

- Likert scales for surveys to measure the quality of recommendations and levels of user satisfaction, using values from one to five.

- Behavioral analytics, such as weekly reading activity, reading time, book finish, and quiz attempts.

4.3. Quantitative Results

A performance comparison of the developed KNN-based method with three popular baseline approaches is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of recommendation models.

In addition to reporting average performance metrics, variability measures were computed to assess the stability of the proposed model. The Precision@10 and Recall@10 values are reported as mean ± standard deviation between users. The proposed KNN-based model achieved Precision@10 = 0.71 ± 0.04 and Recall@10 = 0.63 ± 0.05, indicating consistent performance in different learning profiles.

To evaluate the statistical significance of the observed performance differences, a nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted between the proposed KNN model and the baseline approaches. This test was selected because of the non-Gaussian distribution of the recommendation outcomes. The results indicate that the improvements achieved by the proposed method over the collaborative filtering baseline of users are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Key Findings.

- The proposed KNN approach reaches the same level of accuracy as that achieved using neural networks, but it has the following benefits:

- −

- It has a four to six times faster training time;

- −

- It has full interpretability, which is necessary in educational contexts.

- Bilingual normalization results in an improvement of 12.4% over a monolingual baseline in the accuracy measure for the Kazakh language, hence proving the success of the strategy for bilingual feature integration.

4.4. Engagement and Educational Outcomes

The data on user interactions post deployment shows encouraging trends in terms of engagement and learning results:

- The average weekly reading time per user increased by 28%.

- A 34% increase in the number of finished books was observed.

- A 22% increase in quiz responses was observed.

- A 17% increase in self-perceived levels of motivation was observed using a survey (n = 490).

Qualitative User Feedback

The three beneficial components that were constantly cited are as follows:

- 1.

- Suggestions related to their interests, reading levels, and corresponding age ranges;

- 2.

- Gamification features such as badges, points, and levels were an incentive mechanism that motivated engagement with the system;

- 3.

- The bilingual interface supported flexible switching between the texts in Kazakh and Russian.

In addition, the teachers noted that the system exhibited high alignment with the national curriculums, as well as the ability to track the independent reading development of students using dashboards and analytics reports.

However, despite its focus on participation, the trend of participation in quiz activities is considered an indicator of engagement with learning activities. It is important to note that despite the increase in reading activities and participation in quiz activities, it represents an increase in participation in learning materials and not necessarily an indicator of learning achievement. The current study uses quiz activities and behavioral data as an indicator of the engagement and motivation of learners and not as an indicator of improvement in reading comprehension and literacy skills. Hence, despite the increased engagement in quiz activities after reading the suggested readings, it represents increased interaction with the learning content.

4.5. Discussion of Results

The assessment clearly shows that there is an ideal blend of accuracy, efficiency, and educative significance that the KNN-based model achieves. The prominent benefits of this model include the following:

- High levels of interpretability: The educators will be in a position to understand the reasoning behind the recommendations of the books (for instance, the genre and age appropriateness).

- Low computational cost: It is appropriate for implementation within the school setting.

- Strong bilingual capabilities: It meets linguistic diversity requirements in Kazakhstan.

- Integration of Gamification: Gamification reinforces learning motivation and literacy practices.

Unlike deep learning methods or so-called graph models, KNN retains transparency and integrity, which play vital roles when working in a pedagogically delicate environment.

4.6. Visualization Example

For the purposes of demonstrating the operation of the recommended system, Table 4 lists the example recommendations produced for a number of learner profiles defined in relation to their grade levels as well as language preferences. The operation of the recommended system in responding to learner characteristics in a bilingual environment may be observed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparative overview of recommendation approaches, combining quantitative performance metrics with qualitative design characteristics to provide a holistic assessment of model suitability for educational deployment.

One major limitation of this research is that there are no direct measures of learning effectiveness, such as reading comprehension or literacy skills. Rather, the measures taken are those that relate to engagement, such as reading completion, the amount of reading that has occurred, quiz attendance, and self-reported levels of motivation. These measures are best seen as indirect measures of learning behavior, and not as measures that demonstrate actual learning outcomes. This also relates to the constraints that exist in conducting pilots in schools, which relate to ethical approvals and school policies that prevent actual learning outcome measures from being taken.

In ethical terms, the proposed system can be interpreted as a supporting educational technology, rather than being a decision-making authority. In line with transparency, teaching surveillance, and large-scale analysis, the proposed system seeks to reconcile the advantages and disadvantages related to learner autonomy, as well as data privacy and responsibility.

Please note that all learner profiles and their recommendations described in Table 4 are anonymized and used only for illustrative purposes.

4.7. Summary

The results show that the bilingual KNN-based recommendation model proposed achieves the following:

- Strips away overly specific elements from educational reading recommendations,

- Promotes student engagement and autonomous behaviors.

- Adapts effectively in resource-limited educational environments,

- Most importantly, it fits within teaching goals like inclusiveness, transparency, and relevance.

The results confirm the potential of lightweight and explainable AI solutions for country-wide adoption in Kazakhstan’s bilingual educational environment.

4.8. Example of Interpretable Recommendation

For the purposes of demonstrating the interpretability of the proposed method, a specific example of how a recommendation is made based upon explicit user and item features shall be presented. For this purpose, a Grade 6 student with their preferred learning language being Kazakh, whose reading background shows a strong interest in folklore and adventure stories, with moderate engagement, shall be considered.

The recommendation for the Kazakh-speaking learner would be based on the following interpretable factors for the Kazakh-language folklore book: (i) similarity in genre between the historical preferences of the learner and the genre of the book, (ii) similarity in the level of the learner and the intended age of the book, (iii) compatibility of the languages ensured by bilingual normalization, and (iv) positive aggregation of the signals of interaction for similar learners.

As a result, it becomes possible for educators to relate the result of a recommendation to explicit semantic meaningful attributes rather than latent representations. It becomes easier for educators to validate recommendations in a pedagogical manner that informs the intervention. Thus, it becomes evident that it is appropriate to apply the proposed model in a learning environment that demands explainability.

5. Discussion

The resulting validation confirms the effectiveness of the designed bilingual recommendation system using the KNN algorithm on a range of parameters. Here, the implications of the result findings are discussed in a broader context. Moreover, there lies limitations in the findings.

5.1. Interpretability and Efficiency

One major benefit associated with the suggested technique is its strong interpretability capability when compared to deep learning algorithms as well as black box recommendation systems. This is because the logic behind providing a recommendation on a particular book can be explained using visible attributes such as genre choice, language type, as well as a student’s reading habits.

Furthermore, the model is computationally efficient in that it requires only a small amount of the training time of neural network models. As a result, this model will be ideal for use in an educational environment where computing speeds are limited. For example, in rural educational institutions.

5.2. Bilingual Adaptation and Language Equity

The fusion of bilingual processing pipelines with multilingual normalization resulted in a significant boost in recommendation performance, especially on Kazakh content, where general models tend to deteriorate since there are fewer linguistic resources available. This kind of result lends credibility to the choice to conduct language-specific preprocessing, which is not always considered in relation to educational recommenders.

In addition, the bilingual framework supports language inclusion and equity with the ability to present information to students in the language of choice. This is especially important in environments like Kazakhstan, with multiple languages such as Russian and Kazakh being widely spoken in academic circles. The findings on increased levels of engagement and motivation also confirm that bilingual personalization significantly helps empower learners.

The direct integration of bilingual normalization improves the explainability of the proposed system. With similarity calculations based on normalized and meaningful semantic features instead of latent representations, it becomes easier for educators to understand why a set of recommendations is made for a given learner based on different bilingual contexts. It is a significant prerequisite for the adoption of AI in a school setting. Thus, bilingual normalization plays a dual role in the proposed framework. It ensures bilingual fairness while improving the explainability of the system.

5.3. Gamification and Motivation

Adding gamification elements—that is, points, badges, and reading levels—and achieving positive outcomes in terms of reader engagement metrics like reading time, number of completed books, or quiz activity participation can certainly be considered in line with the general body of research that establishes the vital role that gamification elements play in fundamental self-regulated learning tasks.

In addition, the blending of recommendation logic with gamified feedback, such as unlocking achievements based on interaction with a variety of genres, was an added feature to enhance the learning experience without requiring additional infrastructure to manage these goals. The ability of the system to merge educational goals with play features is an essential element in its adoptability.

5.4. Educational Alignment and Teacher Feedback

The teachers also found the recommendations produced by the system to be educationally sound, in line with educational goals, and promoting independent reading. The presence of analytical dashboards also allowed the teachers to access student activity and make instructional decisions based on reading patterns. This supports the idea that recommendation systems in education should not only be algorithm-based but facilitators in teaching.

Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of lightweight and interpretable recommender systems in educational contexts. For example, Chang and Dao (2026) [59] proposed a K-nearest neighbors-based recommender system to support self-regulated learning in online higher education, reporting improvements in learner motivation, engagement, and learning outcomes while reducing cognitive load. These findings reinforce the viability of similarity-based recommendation models as transparent alternatives to complex deep learning approaches. In contrast to higher education-focused and monolingual settings, the present study extends this line of work to bilingual school education, emphasizing language inclusiveness, fairness, and pedagogical interpretability [59].

Beyond performance considerations, recent research has highlighted that explanations in recommender systems do not merely enhance transparency but can actively influence users’ choices and preferences. Studies on persuasive explanations demonstrate that explanation strategies may unintentionally bias user decision making and shape user profiles over time, raising ethical concerns regarding manipulation and long-term behavioral effects. This perspective further motivates the design choice adopted in this work, where interpretability is achieved through explicit feature representations and similarity-based reasoning rather than persuasive or behavior-shaping explanation mechanisms [60].

Recent work on explainable artificial intelligence has also shown that transparency mechanisms can help users recognize algorithmic bias and perceive potential unfairness in AI-driven systems. Explanation-by-example approaches have been found, in particular, to raise awareness of exclusion when users detect incongruence between explanatory outputs and their own contexts. These insights further support the importance of interpretable system designs that allow educators and learners to scrutinize recommendation logic—an especially critical requirement in bilingual and inclusive educational environments [61].

5.5. Limitations

However, in spite of the outstanding performance shown by the proposed system, there are some limitations that need to be pointed out.