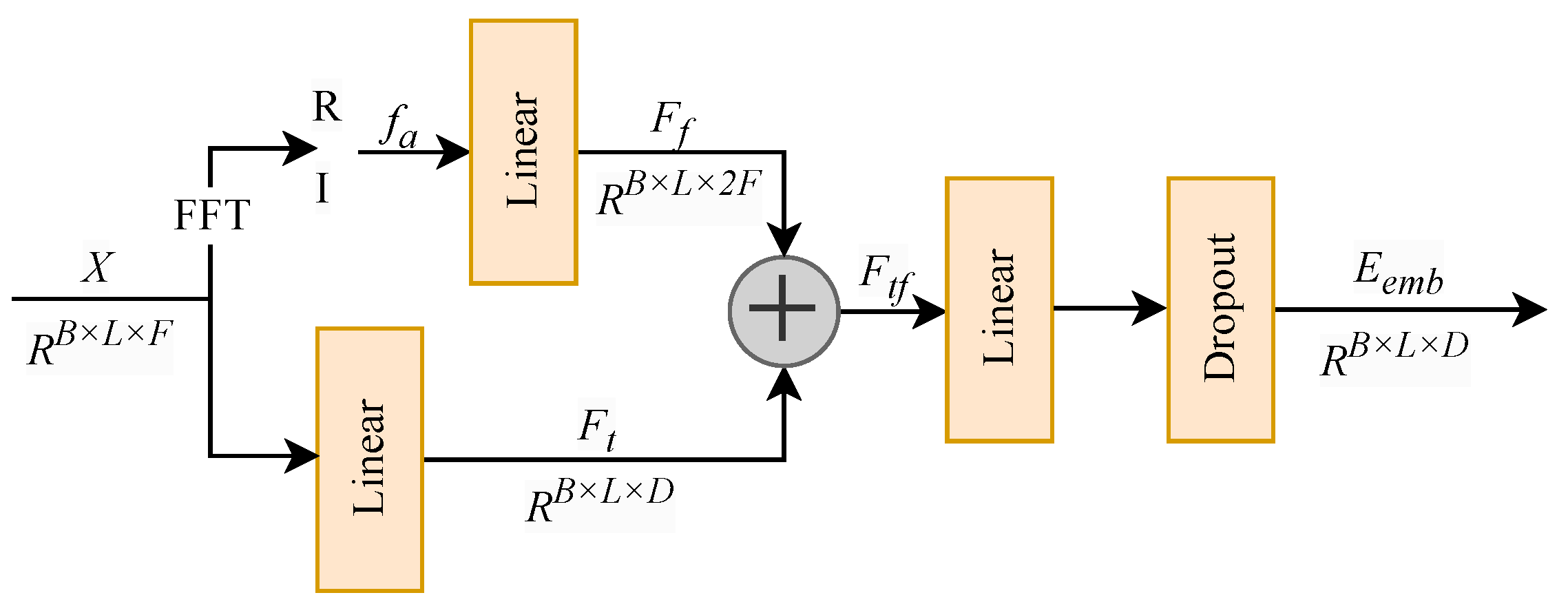

This paper proposes a sequence-to-sequence prediction model based on multi-scale convolutions and an adaptive hierarchical attention mechanism, aimed at addressing long-term sequence prediction tasks. The model integrates frequency-domain feature embedding, an adaptive attention mechanism, multi-scale convolution operations, and a transformer structure to enhance prediction accuracy by efficiently extracting diverse features from temporal data. By processing anchor, positive, and negative samples at the same time, the model captures both temporal and frequency-domain relationships among different sequences. This design enhances its robustness and generalization ability. Experiments further show that the model delivers strong prediction performance across multiple benchmark datasets.

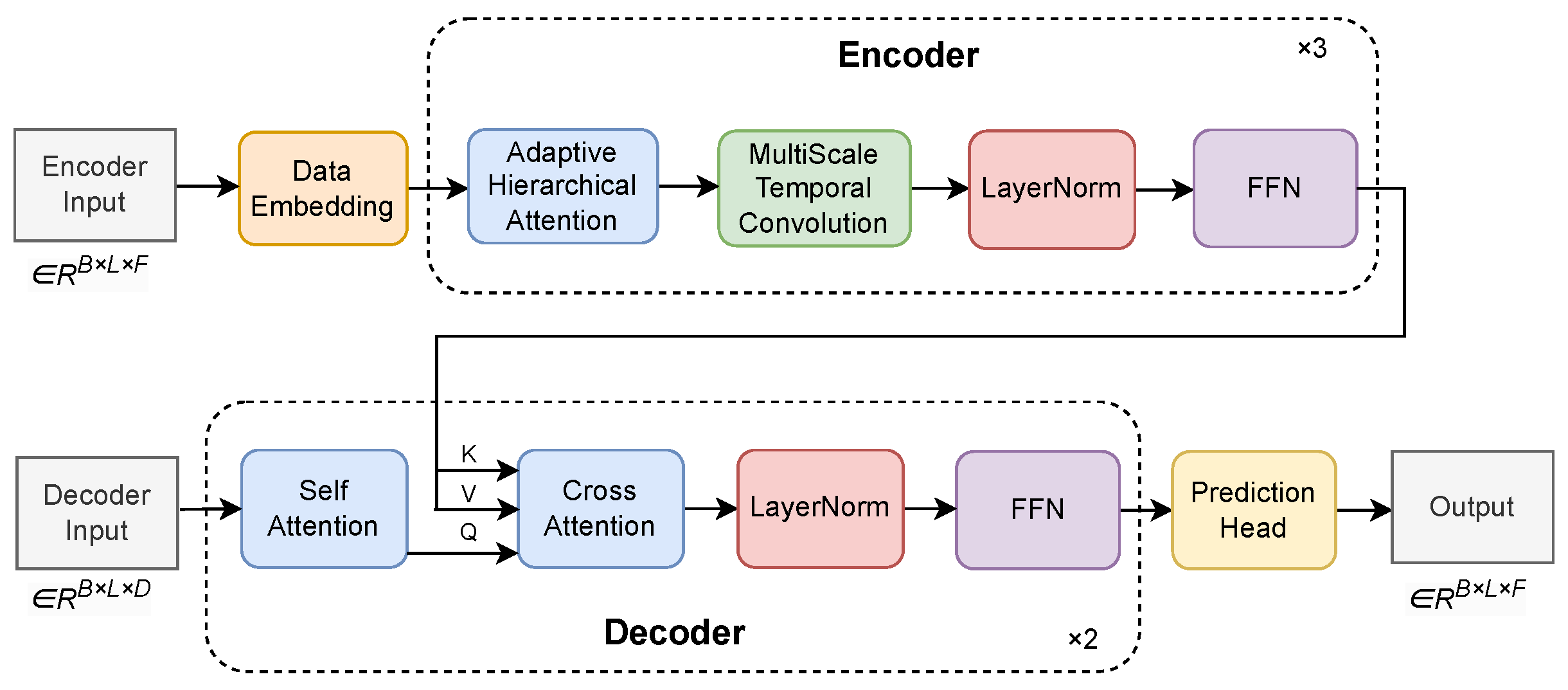

2.3.2. Encoder

The encoder module is designed to effectively capture both global and local temporal dependencies in long time-series data, which is critical for improving representation learning and imputation accuracy. To this end, we propose an encoder architecture that integrates adaptive hierarchical attention with multi-scale temporal convolution.

The encoder is composed of multiple stacked encoding layers, each consisting of an adaptive hierarchical attention module and a multi-scale temporal convolution block.

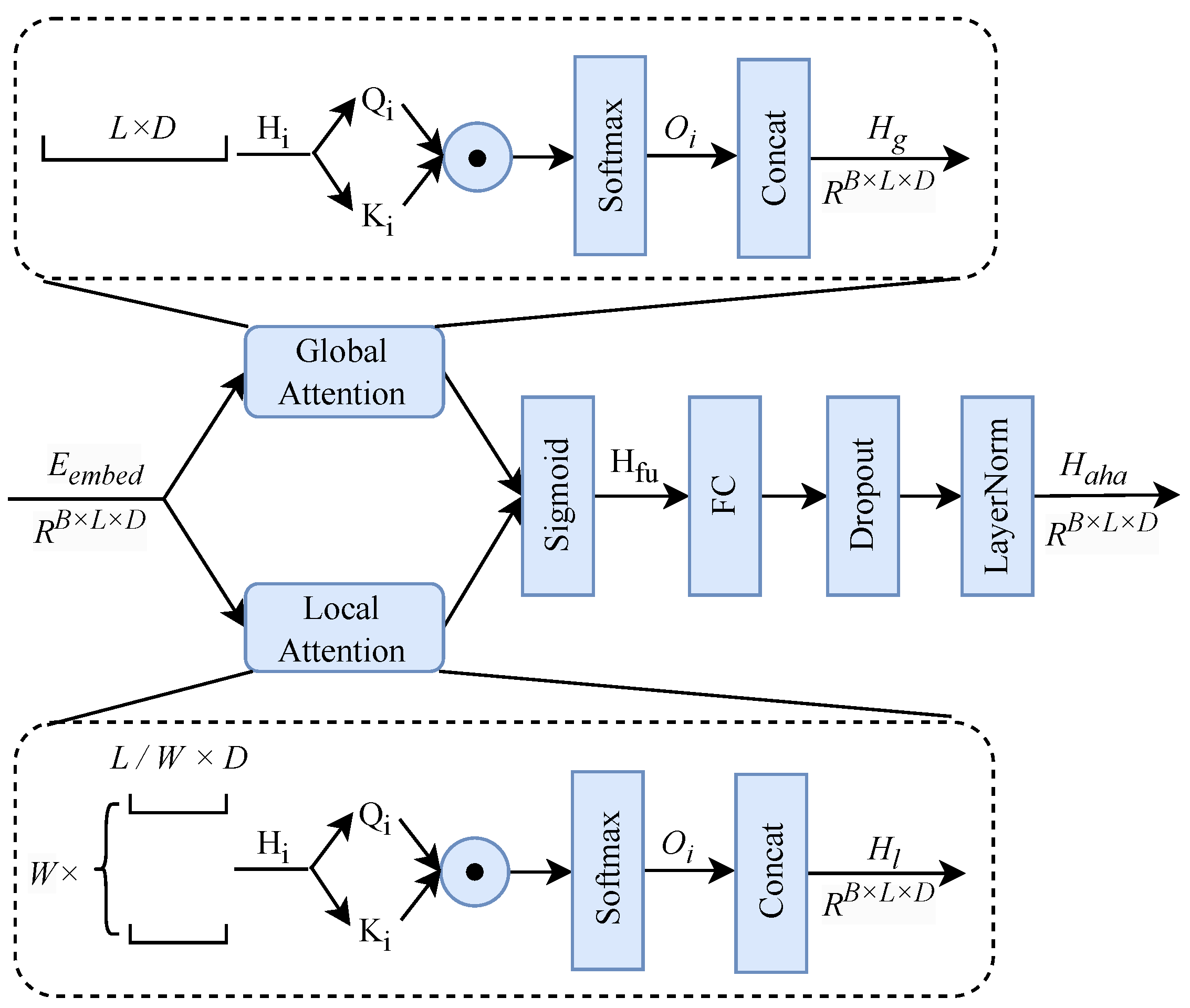

Adaptive hierarchical attention module: This module combines global attention and local attention to simultaneously model long-range dependencies and local contextual patterns. A gated fusion mechanism is introduced to dynamically balance the contributions of global and local attention based on input characteristics.

Given the embedded input features , the adaptive hierarchical attention mechanism jointly models global and local attention representations. For each attention head , the global attention component captures long-term dependencies across the entire sequence, producing , while the local attention component focuses on short-term dependencies within local windows, yielding . The local attention operates within a predefined temporal window centered at each query position. The window size is fixed and shared across all samples during training, providing a stable inductive bias for modeling short-term temporal dependencies.

These two representations are adaptively fused through a learnable gating mechanism based on a Sigmoid activation function, allowing the model to dynamically adjust the importance of global and local information. The fused representation is then processed through a fully connected layer, followed by layer normalization and residual connections to enhance training stability and representation robustness. The overall workflow of the adaptive hierarchical attention module is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The core objective of the adaptive hierarchical attention mechanism is to enable the model to fuse and weight-adjust information features from data embedding layer outputs across multiple levels by introducing global and local multi-layer multi-head attention operations. Ultimately, this yields feature representations enhanced by multi-scale contextual information. This facilitates more effective capture of long-term and short-term dependencies as well as information from different hierarchical levels. Unlike traditional attention mechanisms that usually compute attention weights at a single level, the adaptive hierarchical attention mechanism adjusts weights across multiple levels. It integrates information progressively from local (short-term dependencies) to global (long-term dependencies) and flexibly balances their importance. Through this hierarchical structure, the model can also dynamically measure the correlations between different positions in the sequence, creating direct connections across layers. For example, lower-level features often capture fine-grained details, while higher-level features represent more abstract patterns. Hierarchical attention allows the model to decide which level is more important for the current task and to adjust the contribution of each layer accordingly.

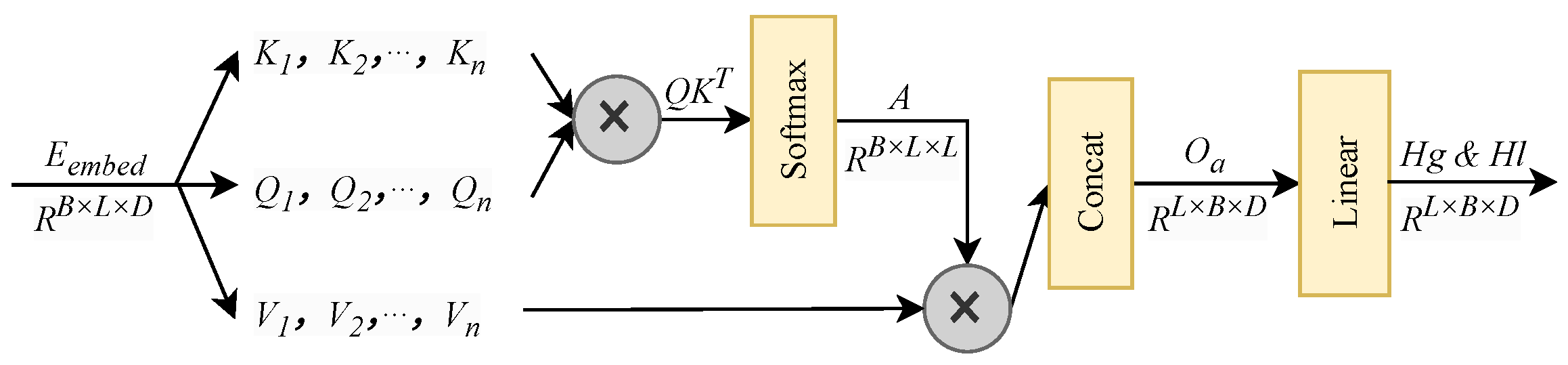

The multi-head self-attention layer captures both global and local patterns by modeling global dependencies across the input sequence through its Query–Key–Value (

Q-

K-

V). Given an input

, the query (

Q), key (

K), and value (

V) are derived after a permutation of its dimensions. Within this mechanism, the core operation involves computing the similarity between

Q and

K, which fundamentally extracts the global correlations across different time steps through a weighted aggregation. The multi-head mechanism computes the attention scores

,

for each head through projection calculations using

h independent attention heads

and their respective weight matrices

,

. These scores are normalized via Softmax for positions

i and

j, then weighted and summed to yield the feature for each head:

The output of a single attention head

i is computed as

. The outputs from all heads are then concatenated into a composite representation

. A subsequent linear projection is applied to

to fuse the features from all heads, allowing them to interact and learn an optimal combination. This process yields a unified and enhanced sequence representation, denoted as the final results

and

. The complete data flow is depicted in

Figure 5.

Unlike conventional attention mechanisms that focus on a single temporal scope, the proposed adaptive hierarchical attention jointly models multiple temporal ranges within each encoding layer and adaptively fuses them through a gated mechanism. The formulas for GlobalAttention and LocalAttention are as follows:

where

Q,

K, and

V represent the query, key, and value matrices, respectively. After modeling global and local attention, the module concatenates the global attention output and local attention output through a gating mechanism. The Sigmoid activation function is used in the gating mechanism to fuse the outputs of global attention and local attention. The purpose is to obtain a weight (a value between 0 and 1) through learning to determine the contribution of global and local features. Through the gating mechanism, the weights of global and local attention are dynamically adjusted based on the context to fuse the two types of features:

The gating weight

is learned automatically from data and determines the relative contribution of global attention output

and local attention output

, yielding the fused representation

. The gate mechanism enables the model to dynamically adapt, balancing between global and local attention based on the characteristics of the input sequence, and adaptively selecting the optimal attention pattern under different contextual conditions. Finally, the output

of the data embedding layer is obtained through the fully connected layer and residual connections:

By integrating adaptive hierarchical attention with multi-scale temporal modeling, the encoder effectively captures temporal dependencies across different resolutions, improving robustness to noise, missing values, and long-term sequence variations.

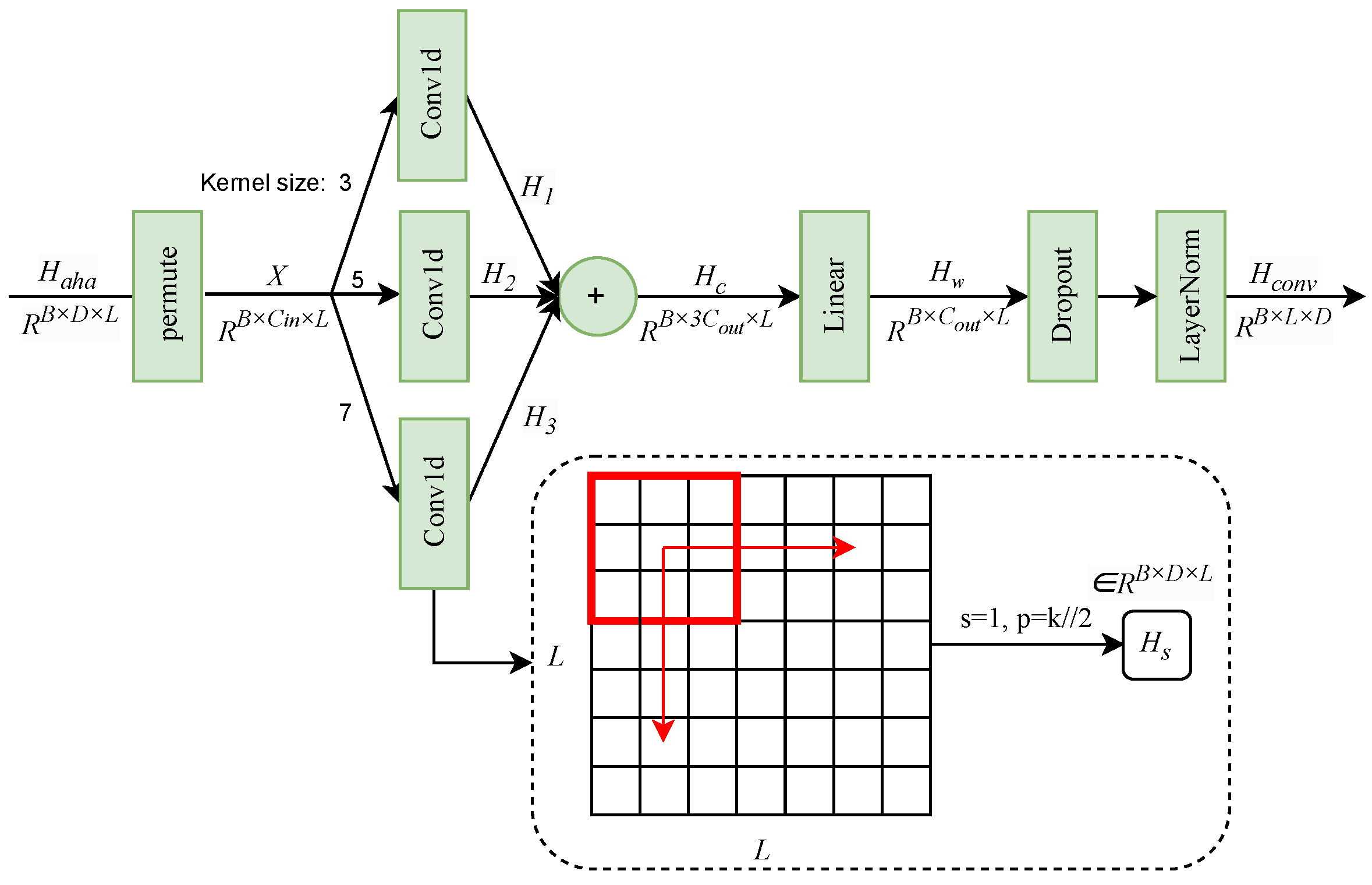

Multi-scale temporal convolution module: This module serves as a complementary local feature extractor to the attention mechanism, enabling the model to capture temporal patterns at multiple resolutions through convolution kernels of different sizes. While attention mechanisms are effective at modeling global dependencies, convolution operations focus on localized temporal structures, thereby enhancing the representation of short-range dependencies at different temporal scales. The overall workflow of the multi-scale temporal convolution module is illustrated in

Figure 6.

We first transpose the output of the adaptive hierarchical attention layer to form the input tensor for the multi-scale convolution module, where B denotes the batch size, is the embedding dimension, and L is the sequence length. The module employs multiple one-dimensional convolution kernels with different kernel sizes to capture temporal patterns at different scales.

For each convolution scale

s, the output feature map is computed as

where

and

denote the convolution weights and bias at scale

s, respectively.

The outputs from different scales are concatenated to form a multi-scale representation

. A linear projection layer is then applied to fuse the multi-scale features:

resulting in a unified feature representation

.

Finally, residual connections, dropout, and layer normalization are applied to obtain the output representation . By integrating multi-scale convolution with attention-based representations, this module enhances the model’s robustness to noise, missing values, and temporal variations commonly observed in real-world sensor data, while effectively capturing both short-term fluctuations and long-term trends.

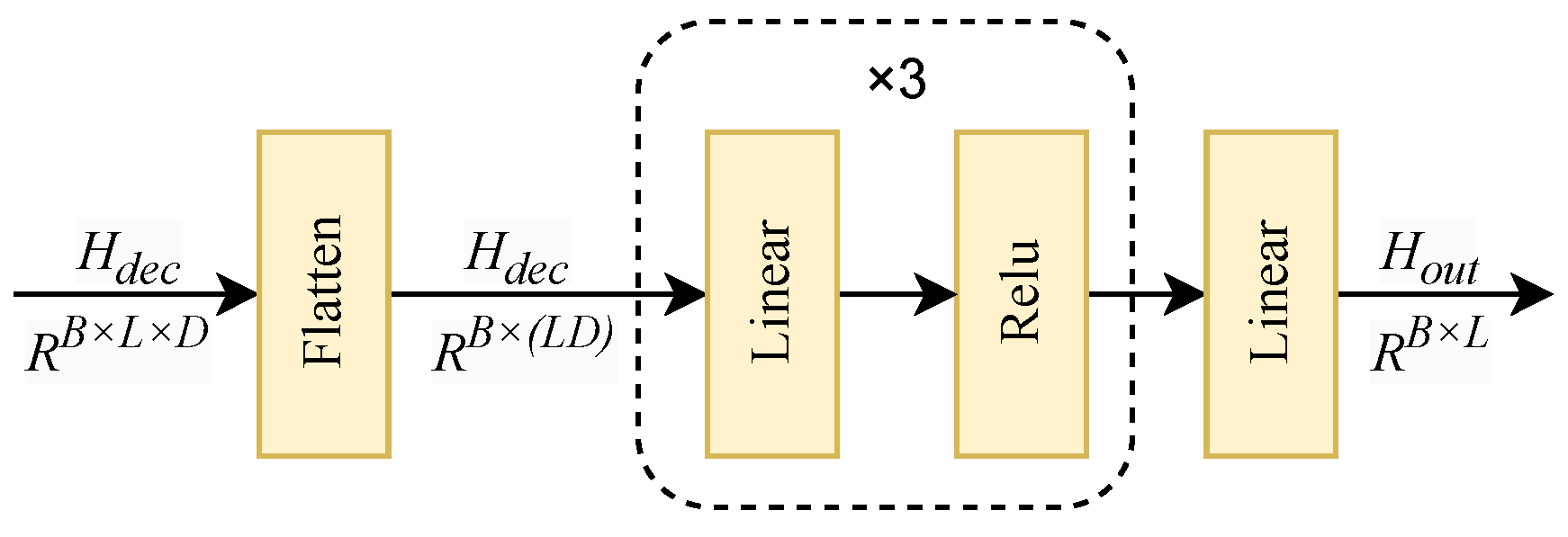

Feedforward neural network (FFN): The feedforward neural network is a standard yet essential component in the encoder and decoder layers, responsible for further transforming and refining the features extracted by the attention and convolution modules. It consists of two fully connected layers with a nonlinear activation function in between. The first linear layer projects the input features into a higher-dimensional intermediate space to enhance expressive capacity, followed by a ReLU activation to introduce nonlinearity and capture complex feature interactions. The second linear layer maps the intermediate representation back to the original feature dimension, ensuring compatibility with subsequent modules. Residual connections and normalization are incorporated to stabilize training and preserve feature consistency. In the proposed model, the FFN operates in a position-wise manner, enabling flexible nonlinear feature transformation for each time step, which is particularly beneficial for handling noisy and partially observed time series commonly encountered in real-world sensor data.

The feedforward network complements the attention and convolution mechanisms by enhancing local feature representations through nonlinear transformations, allowing the model to capture higher-order dependencies while maintaining computational efficiency.

Residual Connections and Layer Normalization: Residual connections and layer normalization are employed to improve training stability and facilitate deep feature learning. Residual connections enable direct information flow across layers by learning residual mappings, effectively mitigating gradient vanishing issues in deep architectures. Layer normalization standardizes intermediate feature distributions, accelerating convergence and improving robustness. These mechanisms are especially important in long time-series modeling scenarios with missing values or long consecutive data gaps, as they help maintain stable representations and reduce sensitivity to noise and distribution shifts.

Overall, the encoder integrates adaptive hierarchical attention, multi-scale temporal convolution, and position-wise feedforward transformation to jointly model global dependencies, local patterns, and nonlinear feature interactions within time-series data.

By combining attention-based long-range modeling with convolutional multi-scale feature extraction, the encoder is able to capture temporal dependencies across different resolutions while maintaining robustness to noise, missing values, and long-term temporal variations. This design is particularly well suited for real-world air quality monitoring data affected by sensor outages and complex environmental variations.