Abstract

Technology plays an increasingly vital role in modern education, providing new opportunities to enhance engagement and conceptual understanding. Among emerging innovations, Augmented Reality (AR) enables interactive visualization that supports deeper comprehension of abstract and spatially complex concepts. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of AR technology integrated with the STEAM approach on fifth-grade students’ learning of geometric solids, focusing on spatial skills, motivation, and academic achievement. A quasi-experimental design was implemented, involving an experimental group that engaged in AR- and STEAM-based activities and a control group that followed traditional instruction. Results indicated significant improvement in geometry test performance within the experimental group (p < 0.001) and higher post-test performance compared to the control group (p = 0.005). Although motivation scores were higher in the experimental group, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.083), suggesting a positive trend that merits further exploration with a larger sample. Overall, the findings highlight the pedagogical potential of integrating AR and STEAM approaches to support engagement and conceptual understanding in geometry education.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, societies have been facing rapid technological transformations that have influenced various areas of life, including education. Developments in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) have opened new horizons for how the learning process is conceived and implemented. The integration of digital tools and interactive technologies in teaching has created opportunities to make education more personalized, practical, and aligned with the needs of the new generation of learners. In this context, Augmented Reality (AR) emerges and is increasingly attracting attention in the field of education due to its potential to connect abstract concepts with tangible and comprehensible experiences [1].

Augmented Reality offers real-time interaction between the physical and virtual worlds, enriching learning experiences through three-dimensional visualizations and dynamic interactions. In a classroom environment, this means that students are no longer limited to printed illustrations or theoretical explanations, but can instead explore objects and phenomena through vivid simulations that foster deeper and more active engagement. Even more importantly, AR functions not merely as a visual aid, but as a didactic mediator that bridges theoretical knowledge with practical applications.

This becomes especially significant when AR is combined with the STEAM approach (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics). STEAM aims at interdisciplinary integration, placing students in projects that demand collaboration, critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity [2]. The synergy of AR with STEAM creates a rich pedagogical environment where students not only visualize abstract concepts but also experience them through practical interactions. For example, during geometry lessons, students can use AR to view a cube or pyramid from multiple perspectives, analyzing faces, vertices, and edges directly. This process not only facilitates the construction of conceptual understanding but also supports spatial visualization and interpretation processes that are frequently required in learning 3D geometry, which are essential for learning mathematics and other scientific disciplines. However, school practice and research literature consistently indicate that geometry remains one of the most challenging topics for primary students [3]. This often impacts student motivation resulting in lower performance. The difficulties are linked not only to the acquisition of mathematical knowledge but also the spatial demands of interpreting and reasoning about 3D objects from 2D representations, which are fundamental for logical thinking and the development of 21st-century competences [4].

At this point, the exploration of innovative approaches that can provide effective alternatives to traditional methods becomes essential. AR represents a promising solution, as it combines visual experience with practical interaction, offering a more engaging and meaningful learning process [5]. Researchers have shown that the use of AR in education not only increases student motivation and engagement but also has a direct impact on the acquisition of mathematical concepts and the development of spatial skills [6,7].

This study is grounded in the idea that key functional features of AR (3D visualization, manipulation/rotation, and multiple viewpoints) may support spatial visualization and interpretation processes that are frequently required in learning 3D geometry. These spatial aspects are operationalized at the task level (i.e., performance on spatially demanding geometry items), rather than as a separately measured spatial ability construct [8,9]. In this sense, dynamic 3D representations may help students move from predominantly visual recognition to the analysis of properties [10], by making the structure of solids (faces, edges, vertices) and part–whole relationships more salient. Given that the study employs a quasi-experimental design implemented in an authentic school setting, the observed effects are interpreted cautiously as the outcome of interactions among the technology (AR), the instructional organization (STEAM), and contextual factors (e.g., teacher/class).

Based on these challenges and potentials, this study aims to evaluate the impact of AR on improving the academic performance of fifth-grade students in learning geometric solids, through its integration with the STEAM approach. The study focuses on three core dimensions: (1) the development of spatial skills, (2) the enhancement of student motivation for active participation in the learning process, and (3) the improvement of academic results in geometry-related assessments. Led by the following research questions: How does the use of AR affect the development of spatial skills compared to traditional methods? To what extent does the integration of AR with STEAM influence student motivation? And what effect does this technology have on academic outcomes in geometry tests? This study tests the following hypotheses:

H1.

Students who learn geometry with AR will show greater improvement in spatial skills than students taught with traditional methods.

H2.

Integrating AR within a STEAM-based approach will lead to higher student motivation than traditional instruction.

H3.

Students taught geometry using AR will achieve higher academic performance on geometry tests than students taught without AR.

In this way, this research study contributes to contemporary literature on technology-enhanced education by offering a model for integrating Augmented Reality and the STEAM approach into mathematics teaching. The expected results will not only help identify the practical benefits of this approach but also provide recommendations for educational policy and teacher professional development, making the teaching of geometry more effective, engaging, and aligned with the needs of 21st-century learners.

2. Related Work

STEAM education represents an interdisciplinary paradigm where advanced academic concepts are interwoven with authentic real-life problems, placing students in contexts that demand the application of knowledge in science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics. This approach seeks to connect theoretical knowledge with practical situations, enabling learners to develop critical thinking and problem-solving competences in reflective real-world contexts [11]. According to [12], the integration of STEAM disciplines should not remain purely theoretical, but must extend into applied settings of technology and engineering, where knowledge is employed to solve problems related to natural processes, plant development, or ecosystem functioning. A key element of this approach is self-discovery, which deepens students’ awareness of the value and relevance of the problem at hand. STEAM draws heavily on constructivist theory, emphasizing experiential learning and “learning by doing”. In this sense, STEAM projects move away from linear approaches and predetermined solutions, instead promoting creativity, innovation, and originality [13]. To maximize students’ potential, schools and teachers design methods that encourage experimentation, creation, and reformulation of ideas into new understandings. Thus, STEAM is not merely a methodological approach but a long-term strategy for developing sustainable skills for the future [14]. For teachers, this means assuming a deeper role as designers of learning environments, where project-based learning and questioning strategies stimulate critical analysis, deeper thinking, and innovation [15].

Modern technologies have played a transformative role in strengthening STEAM education. Beyond traditional digital tools, Augmented Reality (AR) has emerged as one of the most influential technologies in education. AR blends elements of the real and virtual worlds to create rich and interactive learning experiences [16]. In an era where students, as members of a digital generation, are immersed in devices and applications, the use of AR in education responds to the demand for more sophisticated, personalized, and engaging learning environments [1,17]. Research has shown that AR enhances motivation, improves visual and spatial skills, and provides more concrete experiences for understanding abstract concepts [4,6,7]. The integration of AR into STEAM is considered a crucial step toward creating interdisciplinary and practically applicable learning environments, as also emphasized by [18], who explored Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality as supported strategies for K-12 STEM learning. An umbrella review conducted by [19] further reinforces this potential, identifying AR as a transformative educational medium that enhances spatial reasoning, engagement, and learning performance across STEM disciplines. Coming back to AR, ref. [20] claimed that students can explore complex concepts via 3D visualizations, developing not only technological but also creative skills. For example, projects involving the 3D modeling of buildings through AR allow students to connect art with science and mathematics, blending aesthetic design with mathematical calculations as complementary dimensions of a single project. However, effective integration requires teachers to be trained and capable of using AR meaningfully; otherwise, its potential may remain underutilized [21].

In geometry education specifically, AR has demonstrated clear benefits. Unlike traditional drawings or rigid models, AR allows students to manipulate three-dimensional shapes in real time, facilitating the understanding of spatial relationships and improving visualization skills [19]. Its integration with Van Hiele’s theory of geometric thinking supports students’ progressive movement from basic visualization toward more advanced deductive reasoning [8,10]. Through interactive visualization, learners can better understand complex relationships between geometric elements and strengthen their confidence in mathematical abilities. Existing literature suggests that the impact of AR is not only cognitive but also emotional. Active involvement and the sense of achievement students experience when manipulating 3D objects enhance motivation, engagement, and self-confidence in subjects such as mathematics, which is often perceived as challenging [22]. Furthermore, AR enables personalized learning, allowing students to progress at their own pace, addressing individual needs and improving academic performance [23]. These avantages position AR as a powerful tool for sustainable integration into STEAM curricula.

In light of these insights, our study focuses on exploring the impact of integrating Augmented Reality with the STEAM approach in teaching geometry. Unlike much of the existing research, which often emphasizes general technology use in education or higher levels of learning, this study addresses a critical gap by examining how AR can support the acquisition of fundamental geometric concepts among younger learners. By assessing performance on spatially demanding geometry tasks, motivation, and academic performance, this research seeks to provide empirical evidence on the effectiveness of this innovative approach. Furthermore, it contributes to contemporary research by proposing a practical model of technology and pedagogy integration that can inform teaching practice and educational policy, thereby enhancing the quality of mathematics education in schools.

3. Materials and Methods

The research is conducted using a quasi-experimental design consisting of pre-test and post-test to two distinct groups: an experimental group and a control group. Besides the pre and post-test, in both stages, a standardized motivation questionnaire was employed to capture and evaluate students’ levels of engagement throughout the instructional process. This design enhances both the internal validity of the study and the reliability of its outcomes, while also contributing empirically to the ongoing discourse on the integration of innovative technologies in education.

3.1. Data Collection and the Instrument Used

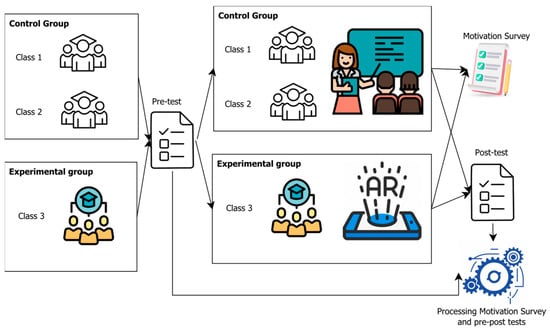

As illustrated in Figure 1, the sample consisted of 40 students aged 11–12 years, drawn purposively from three fifth-grade classes. Two classes, each with 10 students, were assigned as control groups and received traditional instruction, while one class of 20 students was designated as the experimental group, in which the teacher implemented a series of learning activities incorporating Augmented Reality (AR). The total number of participants therefore represented the entire population of the three classes involved in the study.

Figure 1.

Experimental Design.

Data were collected using two instruments: a pre- and post-test to assess spatial and geometric understanding, and a motivation questionnaire to measure students’ attitudes toward the learning process. Each test comprised eight closed-ended questions totaling 20 points, designed to evaluate students’ ability to identify the faces, vertices, and edges of three-dimensional geometric solids. The pre-test established baseline knowledge, while the post-test measured learning gains following the AR intervention. The test items were adapted from standardized materials provided by BBC Skillswise [24], ensuring alignment with core geometry learning objectives.

Student motivation was measured using the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI), which consisted of 15 items distributed across five subscales: interest/enjoyment, perceived competence, effort, pressure/tension, and perceived interaction. Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability of the instrument was verified using Cronbach’s Alpha, which yielded a coefficient of 0.771 indicating good internal consistency and confirming that the questionnaire reliably measured students’ motivational constructs [25].

3.2. Data Collection Procedures

The tests were carefully designed and adapted to the level of the participating students, and further it was analyzed from an expert of the field. Prior to the implementation, formal approval was obtained from the Municipal Directorate of Education, school principals, and classroom teachers. Student participation was voluntary, and consent was secured from the parents after they were informed about the nature and purpose of the study. Data collection adhered to strict principles of confidentiality and anonymity.

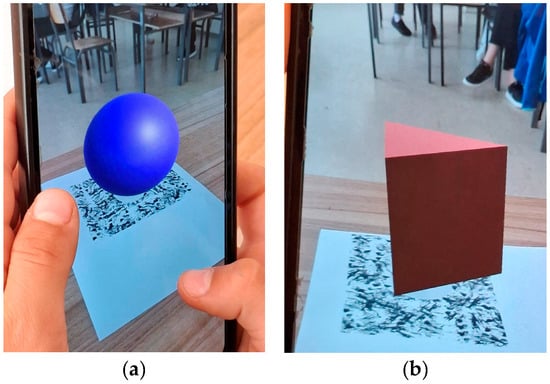

Before the implementation of the intervention, fifth-grade teachers were informed about the study’s objectives and methodological procedures. Figure 2, illustrates the use of AR technology in classroom settings. The image on the left (a) illustrates a virtual sphere projected through the AR application onto a printed marker. Students were able to move their devices around the marker to observe the object from multiple perspectives, helping them understand the concepts of curvature, symmetry, and spatial orientation. The image on the right (b) depicts a virtual rectangular prism rendered on a classroom desk. This activity allowed students to examine the relationships between faces, edges, and vertices in three-dimensional shapes and to manipulate the solid interactively in real time. Together, these visualizations illustrate how AR may support students’ spatial reasoning by connecting abstract geometric concepts to tangible, hands-on experiences.

Figure 2.

Visualization of geometric solids using Augmented Reality technology: (a) A virtual sphere projected on a printed marker through the AR application. (b) A three-dimensional prism displayed in real time, allowing students to observe faces, edges, and vertices interactively.

In the control classes, instruction was delivered by two experienced teachers, one with over 25 years of teaching experience and the other with more than 6 years. Each teacher independently administered the pre- and post-tests to their students to ensure authenticity and instructional continuity.

In the experimental class, instruction and test administration were conducted by the researcher, who has over 6 years of teaching experience in primary education. To ensure consistency across groups, control class teachers were provided with traditional lesson plans, while the experimental group followed daily lesson plans specifically adapted to integrate AR technology and the STEAM approach.

Each testing session lasted approximately 35 min per student. Initially, both groups completed the pre-test to evaluate their prior knowledge of geometric solids. Subsequently, the experimental group engaged in interactive learning activities using the “Augmented Polyhedrons—Mirage” application, which allows students to visualize three-dimensional shapes superimposed onto a marker sheet, enabling them to observe, analyze, and manipulate solids in real space. The intervention spanned a three-week period, with a total of six instructional hours (two hours per week) integrated into regular mathematics lessons.

The control group received the same amount of instructional time and covered identical content, but using only traditional methods and without the researcher’s presence, thereby maintaining parity in instructional time and content coverage across groups. Following the intervention, both groups completed the post-test and the motivation questionnaire, allowing for comparison of the effects of AR-based instruction versus traditional teaching methods on students’ performance and engagement.

3.3. Data Analysis

For this research paper, the authors used SPSS version 29 for data analysis. The Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were used to describe motivational subcomponents and to analyze students’ pre- and post-test results. Reliability analysis using Cronbach’s Alpha was conducted to assess the internal consistency of the 15-item motivation questionnaire. Paired Samples T-Test was applied to compare student performance before and after the intervention within both groups (experimental and control). Independent Samples T-Test was performed to compare final results between the experimental and control groups. Pearson’s Correlation analysis was used to explore relationships among motivation subcomponents and between overall motivation and final test performance.

These analyses served as the basis for addressing the guiding research questions, thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of the effects of AR and STEAM integration on the teaching and learning process.

4. Results

Results from the experimental group demonstrated a marked improvement following the intervention. The mean pre-test score was M = 13.55 (SD = 4.14), while the post-test mean rose to M = 16.70 (SD = 2.81). This increase, alongside reduced variability, suggests not only higher overall achievement but also greater consistency in student performance after learning through AR and STEAM. In contrast, the control group taught using traditional methods showed little change. The pre-test mean was M = 14.70 (SD = 2.98), while the post-test mean was M = 14.40 (SD = 1.96), for further details see Table 1. Although variability decreased slightly, the mean remained virtually unchanged, indicating that traditional teaching did not significantly improve student outcomes.

Table 1.

Comparison of Pre-Test and Post-Test Results in the Experimental and Control Groups.

4.1. Paired Samples T-Tests

The paired samples analysis revealed a statistically significant improvement between pre-test and post-test results, t (19) = 6.600, p < 0.001, with an average gain of 3.15 points. The correlation between pre-test and post-test scores was also strong (r = 0.879, p < 0.001), suggesting consistency in learning progression at the experimental group. As shown in Table 2, these results confirm that AR and STEAM integration had a substantial positive impact on students’ learning of geometric solids.

Table 2.

Paired Sample T-Test—Experimental Group.

For the control group, no statistically significant difference was observed, t (19) = 0.653, p = 0.522, with only a marginal increase of 0.30 points. This further highlights the effectiveness of AR and STEAM compared to traditional methods.

4.2. Independent Samples T-Tests

Table 3, shows a comparison of post-test results revealing a statistically significant difference between the groups. The experimental group achieved a higher mean (M = 16.70, SD = 2.81) compared to the control group (M = 14.40, SD = 1.96). The Independent Samples T-Test confirmed this difference as significant, t (38) = −3.002, p = 0.005, with a mean difference of 2.30 points.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics of Post-Test Results by each group.

The effect size (Cohen’s d) was calculated at 0.93, which represents a large effect. This demonstrates that AR and STEAM had a strong practical and educational impact, not merely a statistical one, on improving students’ academic performance in geometry.

4.3. Analysis of Student Motivation

The Intrinsic Motivation Inventory revealed generally high levels of motivation among the experimental group, see Table 4. The highest mean was for perceived competence (M = 13.50, SD = 1.47), followed by interest/enjoyment (M = 12.50) and perceived interaction (M = 12.40). Pressure/tension scored lower but remained within acceptable levels, suggesting that AR did not create excessive stress. Overall motivation averaged M = 60.75 (SD = 7.64), reflecting a strong positive motivational effect of AR integration.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics for the Motivation Subcomponents.

Further, the Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed significant positive relationships between total motivation and several subcomponents, particularly pressure and interaction (r = 0.838, p < 0.01), and effort (r = 0.834, p < 0.01). Interestingly, pressure was not interpreted negatively but rather as a positive challenge, stimulating higher engagement. These findings emphasize that interactive technologies like AR foster deeper emotional and cognitive involvement, which in turn sustain intrinsic motivation. When comparing total motivation, the experimental group reported higher scores (M = 60.85, SD = 7.45) than the control group (M = 56.80, SD = 6.91). However, this difference did not reach statistical significance, t (38) = 1.782, p = 0.083. While not conclusive, the trend indicates a positive influence of AR and STEAM, which could become more pronounced in studies with larger samples.

To evaluate whether there was a significant difference in overall motivation between students who learned through the AR and STEAM method and those who followed traditional methods, an independent samples t-test was conducted. The results showed that although the experimental group reported a higher mean motivation score (M = 60.85) compared to the control group (M = 56.80), this difference was not statistically significant, t (38) = 1.782, p = 0.083. While this result does not meet the conventional threshold for statistical significance (p < 0.05), the positive trend is evident and suggests a potential effect of the AR and STEAM intervention, which may become clearer in future studies with larger samples and more refined designs.

5. Discussion

The overall findings provide compelling evidence that the combination of AR technology and STEAM-based instruction yields significant educational benefits, particularly in cognitive and performance related outcomes.

5.1. Spatial Skills Development

The findings related to geometry test performance clearly indicate that AR technology can serve as a powerful cognitive scaffold in the comprehension of three-dimensional geometrical concepts [8,9,20]. Students exposed to AR-enhanced learning demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in their geometry test scores, with the experimental group’s mean score rising from 13.55 to 16.70 (p < 0.001). Conversely, the control group, which received traditional instruction, showed no notable gains over the same period. Given that spatial ability was not assessed using a separate validated instrument, spatial aspects are discussed here as a theoretical interpretation rather than a distinct measured outcome.

These outcomes suggest that AR environments may facilitate mental visualization and spatial reasoning by enabling learners to manipulate virtual geometric models in real time but it is important to emphasize that teachers need to be competent to integrate AR in classes otherwise as [21] claimed, the effect of AR potential may remain underutilized. Such interactivity bridges the gap between abstract geometric representations and their real-world spatial counterparts. This finding resonates with constructivist learning theory, which posits that knowledge construction occurs through active engagement and experiential learning. Moreover, it aligns with empirical evidence from previous studies [8] emphasizing that immersive, visual, and interactive modalities promote the internalization of complex spatial relationships. By visualizing three dimensional solids dynamically, students are better able to understand geometric transformations, recognize patterns, and mentally manipulate shapes, which are commonly associated with spatial reasoning in geometry learning. In the present study, however, these spatial aspects are discussed as a theoretical interpretation rather than a separately measured outcome. Although the results align with literature suggesting that AR supports 3D visualization and interpretation [8,9], alternative explanations should also be considered. Part of the observed improvement may be attributable to a novelty effect and the initial engagement often associated with short-term technology-based interventions [9]. In addition, outcomes may have been influenced by alignment between the intervention and the assessment: because the experimental group practiced 3D manipulation during instruction, they may have had an advantage on tasks requiring 3D interpretation [9], even though assessment conditions were identical across groups. Finally, teacher effects and activity facilitation (e.g., pacing, feedback, classroom interaction) may have contributed, especially given the role of instructional mediation in supporting progress from visual recognition to property analysis within the Van Hiele framework [10]. From a theoretical perspective, the findings suggest that AR may make the structure of solids and part–whole relations more accessible, reducing reliance on static 2D representations [8]. However, due to the quasi-experimental design and lack of randomization, interpretation remains appropriately cautious and warrants replication in future studies with higher levels of control.

Additionally, the visual immediacy offered by AR may reduce cognitive load, allowing learners to allocate cognitive resources more efficiently toward conceptual understanding rather than mental reconstruction of geometric figures. The combination of AR and STEAM, therefore, not only supports spatial visualization processes but also situates learning within authentic, interdisciplinary contexts that encourage problem-solving and critical thinking, core attributes of 21st-century competencies.

5.2. Student Motivation

The integration of AR and the STEAM approach also revealed notable, though not statistically significant, improvements in students’ motivation toward geometry learning in line with the findings in [13,17,21] who also claimed that AR in general STEM education highlighted multiple benefits on the educational and cognitive levels, including effective visualization and understanding of abstract content, improved academic performance, heightened motivation and satisfaction, and stronger classroom engagement and interaction. While the mean total motivation score was higher for the experimental group (M = 60.85) compared to the control group (M = 56.80), the difference narrowly missed statistical significance (p = 0.083). Despite this, correlation analyses demonstrated meaningful associations between effort, interaction with technology, and perceived competence, suggesting that AR learning environments promote both affective and cognitive engagement.

These outcomes can be interpreted within established motivational frameworks. According to Keller’s ARCS model [26], motivation in learning environments arises from the interplay of attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction. AR experiences, by their nature, capture learners’ attention through novelty and interactivity while increasing relevance by connecting abstract mathematics to tangible, real-world applications. Similarly, Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination Theory [27] underscore the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in fostering intrinsic motivation. AR environments inherently support these conditions by allowing learners to explore content autonomously, receive immediate feedback, and collaborate with peers within an engaging digital space.

Existing research supports these results [18,19]. Prior research [9,22,28] has shown that AR-based learning enhances interest and emotional involvement by promoting active exploration, creativity, and interdisciplinary thinking fundamental principles of STEAM pedagogy. The current study extends this body of work by situating AR within a geometry-specific context, showing that motivational benefits may emerge even when statistical significance is not reached.

It is worth noting that motivational effects may depend on duration and continuity of exposure. The relatively short intervention period in this study may have limited the full realization of AR’s motivational potential. Longitudinal studies could explore whether sustained exposure to AR-enhanced learning environments results in cumulative motivational gains and greater persistence in mathematics learning.

5.3. Academic Performance

In terms of academic achievement, the results were both statistically and practically significant. Students in the experimental group achieved higher post-test mean scores (M = 16.70) than those in the control group (M = 14.40), representing a difference of 2.30 points (p = 0.005) with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.93). The Mann–Whitney U test corroborated this outcome (U = 99.00, Z = −2.789, p = 0.005), confirming that the AR-based intervention had a substantial and meaningful impact on learning performance. AR’s influence on academic achievement may be explained by its ability to merge visual, auditory, and kinesthetic modalities, fostering multisensory learning. The use of AR allowed students to view and manipulate geometric solids from different perspectives, facilitating a deeper understanding of shape properties, symmetry, and volume. Such multimodal learning environments are supported by Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning, which suggests that presenting information through multiple channels enhances comprehension and retention. Empirical research supports these observations [18]. Studies by [18,29] and [6] have consistently reported that AR-based instruction improves academic performance by strengthening conceptual clarity and increasing students’ sense of ownership over their learning process. Within the STEAM framework, this integration also encourages cross-disciplinary connections, prompting learners to apply mathematical reasoning to artistic, scientific, and engineering problems.

5.4. Overall Implications and Educational Significance

Collectively, the findings of this study offer strong empirical support for the pedagogical value of AR-enhanced STEAM instruction in primary education. The integration of AR and STEAM methodologies substantially improved geometry test performance, including tasks with higher spatial demand, and academic performance while fostering positive, albeit not statistically significant, trends in motivation.

These results align with international research demonstrating that AR, when embedded in constructivist and interdisciplinary learning frameworks, enhances cognitive engagement and conceptual mastery [8,9,20]. AR provides learners with opportunities for experiential learning that would be otherwise unattainable in traditional classrooms, allowing them to explore geometric principles through interactive manipulation and visual immersion [18]. From a pedagogical perspective, these findings underscore the need for teacher training programs that emphasize the integration of technology, specifically AR tools, within STEAM curricula [21]. Teachers play a central role in facilitating the transition from passive content consumption to active knowledge construction. Therefore, professional development should focus on equipping educators with the digital and pedagogical competencies necessary to design AR-based lessons that align with curricular standards and learning objectives [19].

5.5. Limitations

One notable limitation of the present study concerns the relatively small sample size, comprising only forty participants divided evenly between the control and experimental groups. This limited number of participants constrains the statistical power of the analyses and restricts the extent to which the findings can be generalized to broader educational contexts. Moreover, the use of different instructors for each group may have introduced uncontrolled pedagogical variability, potentially influencing learner engagement and outcomes. The observed positive responses from the experimental group may also be partially attributed to the novelty effect associated with the introduction of Augmented Reality (AR) technology, rather than solely reflecting genuine improvements in geometry learning (including spatially demanding task performance) or motivation. Consequently, future studies will consider employing larger and more diverse cohorts, ensuring teacher consistency across groups, and implementing longitudinal designs to better isolate the pedagogical effects of AR from short-term motivational factors.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that integrating Augmented Reality (AR) with the STEAM approach in teaching yields significant pedagogical benefits for primary school students, particularly in the learning of geometric concepts. Comparison between the experimental and control groups revealed that students exposed to AR and STEAM-based instruction achieved higher geometry test performance and demonstrated greater motivation throughout the learning process. Statistical analyses confirmed a significant improvement in academic performance among the experimental group, indicating that AR supports a more concrete and meaningful comprehension of geometric relationships, including tasks with higher spatial demand. Although the increase in motivation did not reach statistical significance, the positive trend observed suggests the potential of AR and STEAM to enhance learner engagement and interest.

Overall, the integration of AR technology with interdisciplinary frameworks such as STEAM should not be regarded as a supplementary tool but as an essential component of modern pedagogy. This combination provides a tangible opportunity to improve teaching effectiveness, promote active participation, and foster more engaging and transformative learning experiences in primary education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, formal analysis, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation—A.G.; Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing and writing—review and editing—K.P.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as at the time of approval the Republic of Kosovo did not have a national Institutional Review Board (IRB). The Faculty of Education at the University of Prishtina assumed institutional responsibility for reviewing and approving research involving human participants. The study was approved by the Faculty of Education at the University of Prishtina.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chao, W.-H.; Chang, R.-C. Using augmented reality to enhance and engage students in learning mathematics. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2018, 5, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniari, N.I.; Ridlo, Z.R.; Wahyuni, S.; Ulfa, E.M.; Dharmawan, M.K.S. The effectiveness of implementation learning media based on augmented reality in elementary school in improving critical thinking skills in solar system course. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2392, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, T.; Kondo, Y.; Kumakura, H.; Kunimune, S.; Jones, K. Spatial reasoning skills regarding 2D representations of 3D geometric shapes in grades 4 to 9. Math. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 32, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angraini, L.M.; Alzaber, A.; Sari, D.P.; Yolanda, F.; Muhammad, I. Improving mathematical critical thinking ability through augmented reality-based learning. Aksioma 2022, 11, 3533–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, L.L.; de Oliveira Freitas, R.C. Contributions of the Sólidos RA application to the development of geometric visualization from the perspective of augmented reality. Electron. J. Debates STE 2023, 13, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pujiastuti, H.; Haryadi, R.; Arifin, A.M. Augmented reality-based learning media to improve students’ ability to understand mathematics concept. Int. J. Res. Educ. 2020, 9, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Liu, E.; Shen, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, S. Probability learning in mathematics using augmented reality: Impact on students’ learning gains and attitudes. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 560–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.K.; Lee, S.W.Y.; Chang, H.; Liang, J.C. Current status, opportunities, and challenges of augmented reality in education. Comput. Educ. 2013, 62, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçayır, M.; Akçayır, G. Advantages and challenges associated with augmented reality for education: A systematic review of the literature. Educ. Res. Rev. 2017, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hiele, P.M. Structure and Insight: A Theory of Mathematics Education; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Margot, K.C.; Kettler, T. Teachers’ perception of STEM integration and education: A systematic literature review. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2019, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, S.A.; Pereira, N. Differentiating engineering activities for use in a mathematics setting. In Engineering Instruction for High-Ability Learners in K–8 Classrooms; Dailey, D., Cotabish, A., Eds.; Prufrock Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2017; pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera, D.; Ortiz-Revilla, J. STEM vs. STEAM education and student creativity: A systematic literature review. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odufuwa, T.; Adelana, O.P.; Adekunjo, M.A. Assessment of senior secondary students’ perceptions and career interest in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) in Ijebu-Ode Local Government Area, Ogun State. J. Sci. Technol. Math. Educ. 2022, 18, 146–159. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Jong, M.; Tu, Y.-F.; Hwang, G.-J.; Chai, C.S.; Jiang, M. Trends and exemplary practices of STEM teacher professional development programs in K–12 contexts: A systematic review of empirical studies. Comput. Educ. 2022, 189, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, P.; Takemura, H.; Utsumi, A.; Kishino, F. Augmented reality: A class of displays on the reality–virtuality continuum. In Telemanipulator and Telepresence Technologies; SPIE: Cergy-Pontoise, France, 1994; Volume 2351, pp. 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tene, T.; Marcatoma Tixi, J.A.; Palacios Robalino, M.D.L.; Mendoza Salazar, M.J.; Vacacela Gomez, C.; Bellucci, S. Integrating immersive technologies with STEM education: A systematic review. In Frontiers in Education; Frontiers Media SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 9, p. 1410163. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Zhu, D.; Chugh, R.; Turnbull, D.; Jin, W. Virtual reality and augmented reality-supported K-12 STEM learning: Trends, advantages and challenges. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 12827–12863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feijoo-Garcia, M.A.; Gu, Y.; Popescu, V.; Benes, B.; Magana, A.J. Virtual and augmented reality in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education: An Umbrella Review. Information 2024, 15, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syawaludin, A.; Gunarhadi; Rintayati, P. Development of augmented reality-based interactive multimedia to improve critical thinking skills in science learning. Int. J. Instr. 2019, 12, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanuarto, W.N.; Iqbal, A.M. The augmented reality learning media to improve mathematical spatial ability in geometry concept. Edumatica 2022, 12, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda-Medina, J.; Calvo-Ferrer, J.R. Integrating augmented reality into language learning: Digital competencies and attitudes of pre-service teachers through the TPACK framework. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 12123–12146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, M.; Borromeo Ferri, R. A systematic literature review on augmented reality in mathematics education. Eur. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2023, 11, 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. 3D Shapes Quiz [Educational Material]. 2021. Available online: https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/skillswise/maths/ma343dsh/quiz/ma343dsh-e3-quiz.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference (11.0 Update), 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, J.M. Development and use of the ARCS model of instructional design. J. Instr. Dev. 1987, 10, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bressler, D.M.; Bodzin, A.M. A mixed methods assessment of students’ flow experiences during a mobile augmented reality science game. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2013, 29, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.A.; Elinich, K.; Wang, J.; Steinmeier, C.; Tucker, S. Using augmented reality and knowledge-building scaffolds to improve learning in a science museum. Int. J. Comput.-Support. Collab. Learn. 2012, 7, 519–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).