Research on Transfer Learning-Based Fault Diagnosis for Planetary Gearboxes Under Cross-Operating Conditions via IDANN

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

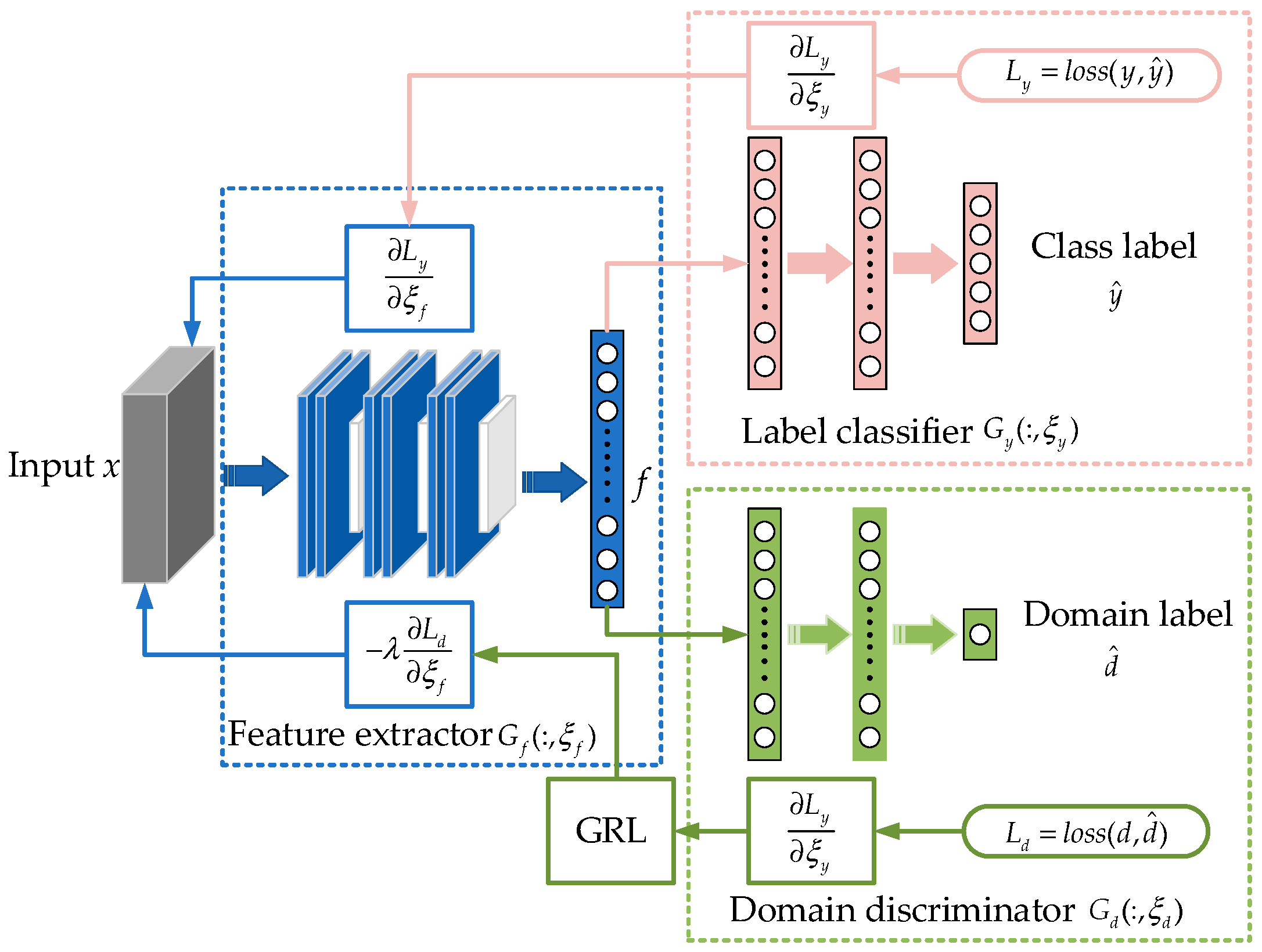

2.1. DANN

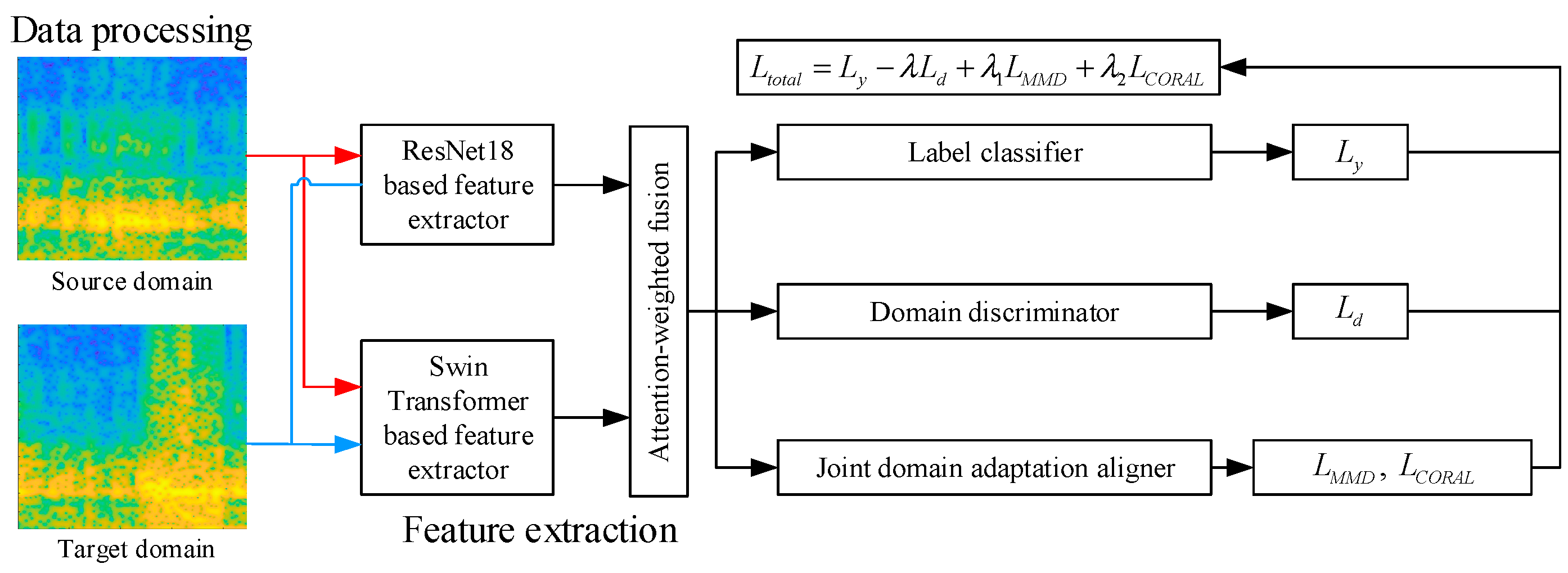

2.2. Improved Domain-Adversarial Neural Network

2.2.1. Joint Domain-Adaptation Aligner

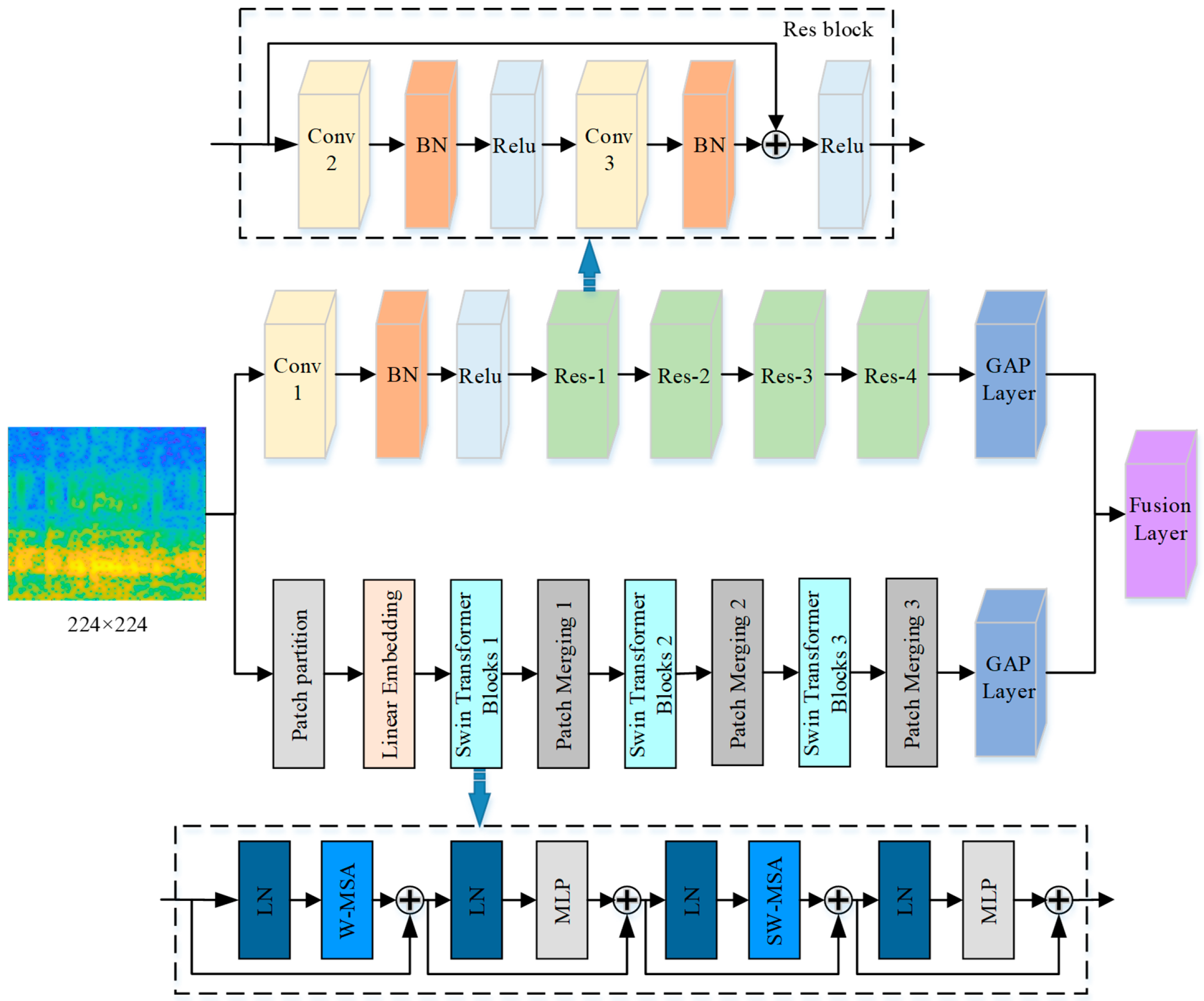

2.2.2. Dual-Branch Feature Extraction

2.2.3. IDANN Structure

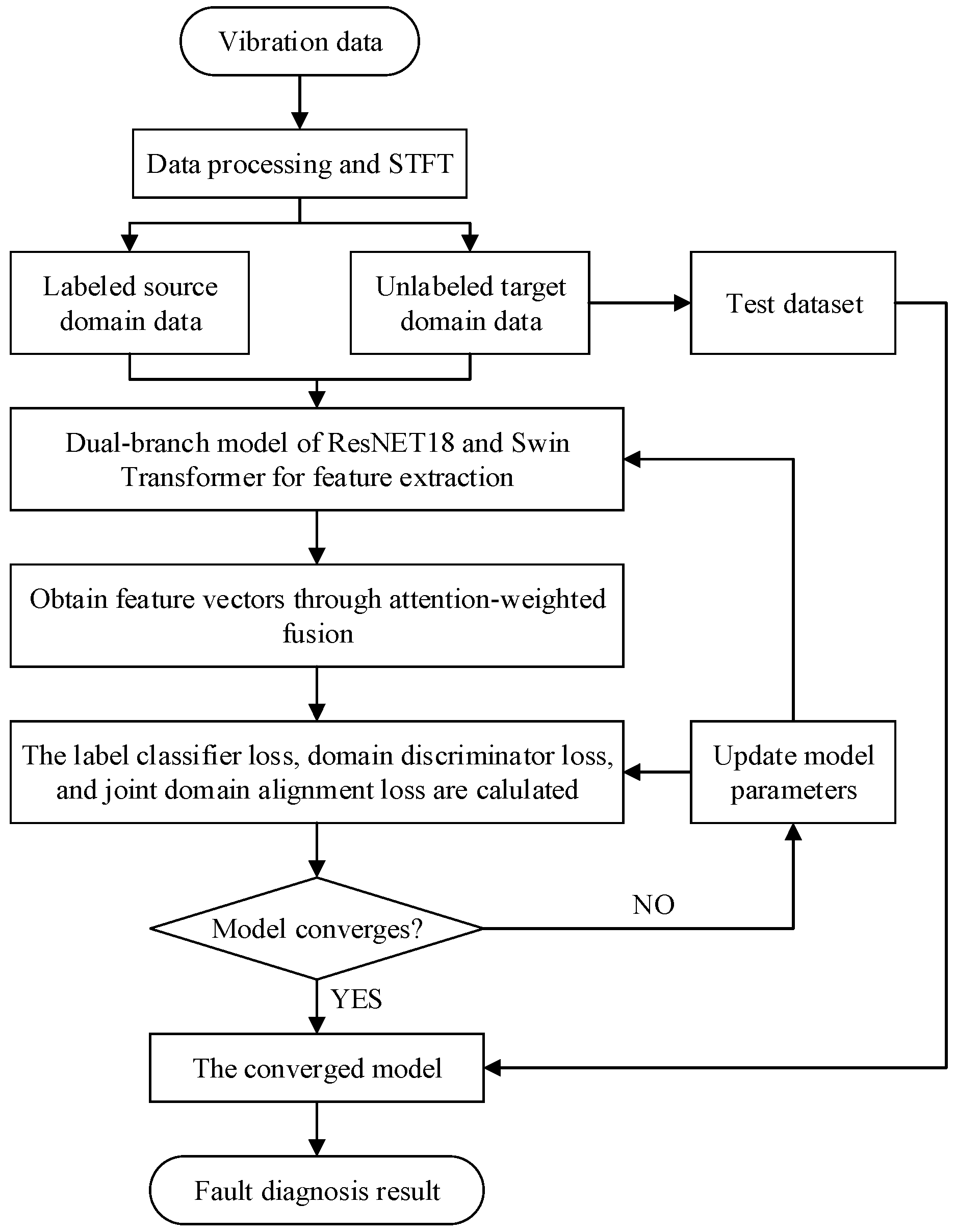

3. Flow of the Proposed Fault Diagnosis Method

4. Experiments

4.1. Description of Experimental Data

4.2. Data Preprocessing and Experimental Settings

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Diagnostic Results

4.3.1. Comparison of Cross-Operating-Condition Diagnostic Results

4.3.2. Feature Visualization Analysis

4.3.3. Ablation Experiment Analysis

4.3.4. Analysis of the Impact of Source Domain Sample Size on Diagnostic Results

4.3.5. Model Complexity and Efficiency Analysis

4.4. Validation on PHM2009 Gearbox Dataset

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Compared to the single ResNet18 feature extractor, the dual-branch feature extraction module based on ResNet18 and Swin Transformer can more fully mine diagnosis-related features, significantly improving the fault diagnosis accuracy of the model.

- (2)

- Both MMD and CORAL can improve the source-target domain alignment effect and enhance the fault diagnosis accuracy of DANN. The joint domain adaptation alignment method based on the two further strengthens this effect, continuously optimizing diagnostic performance.

- (3)

- The experiments verify the positive gain of each improved module proposed in this paper on the cross-operating-condition fault diagnosis performance of planetary gearboxes; moreover, the model can still maintain high diagnostic accuracy in scenarios with scarce labeled data, which is in line with practical application needs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, H.; Cheng, W.; Xing, J.; Wang, W.; Du, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, R.; Chen, X.; Lu, J. Deep learning-based fault diagnosis of planetary gearbox: A systematic review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 77, 730–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, F.; Wang, X.; Wu, S. Incipient fault detection of planetary gearbox under steady and varying condition. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 233, 121003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhao, M.; Ou, S.; Li, S.; Han, X. A self-sensing framework for weak fault detection of planetary gearbox. ISA Trans. 2025, 165, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Ding, K.; He, G.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z. Resonance modulation vibration mechanism of equally-spaced planetary gearbox with a localized fault on sun gear. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 166, 108450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Xia, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Jin, Y. Mechanism analysis for GDTE-based fault diagnosis of planetary gears. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 259, 108627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Cui, L.; Cheng, W. Fault diagnosis of wind turbines under nonstationary conditions based on a novel tacho-less generalized demodulation. Renew. Energy 2023, 206, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Huang, X.; Yang, L.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Intelligent fault diagnosis method of planetary gearboxes based on convolution neural network and discrete wavelet transform. Comput. Ind. 2019, 106, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.; Ha, J.M.; Youn, B.D. Robust deep learning-based fault detection of planetary gearbox using enhanced health data map under domain shift problem. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2023, 10, 1677–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Liu, D.; Cen, J.; Xiong, J.; Wang, N.; Liu, X. Fault diagnosis method of wind turbine planetary gearbox based on improved CNN. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. An intelligent diagnosis scheme based on generative adversarial learning deep neural networks and its application to planetary gearbox fault pattern recognition. Neurocomputing 2018, 310, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Rao, M.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ji, Y. Explicit speed-integrated LSTM network for non-stationary gearbox vibration representation and fault detection under varying speed conditions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 254, 110596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Liu, C.; Han, T.; Yao, J.; Jiang, D. A planetary gearbox fault diagnosis method based on time-series imaging feature fusion and a transformer model. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2022, 34, 024006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Rauf, Z.; Sohail, A.; Khan, A.R.; Asif, H.; Asif, A.; Farooq, U. A survey of the vision transformers and their CNN-transformer based variants. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 2917–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Lang, G.; Zeng, L. Bearing fault diagnosis based on efficient cross space multiscale CNN transformer parallelism. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Feng, G.; Zhen, D.; Jing, H.; Liang, X.; Gu, F. Cross-Condition Fault Diagnosis of Planetary Gearboxes Driven by Data-Model Fusion Based on Improved Domain-Adversarial Transfer Learning. Shock. Vib. 2025, 2025, 9982177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.M.; Xiong, Z.C.; Zhong, J.H.; Xiao, S.G.; Tang, Y.H. Research on fault diagnosis method of planetary gearbox based on dynamic simulation and deep transfer learning. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lv, Y.; Yuan, R.; Dang, Z.; Cai, Z.; An, B. Fault diagnosis of planetary gears based on intrinsic feature extraction and deep transfer learning. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2022, 34, 014009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Yao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Mao, Y. Parameter sharing adversarial domain adaptation networks for fault transfer diagnosis of planetary gearboxes. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 160, 107936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.M.; Youn, B.D. A health data map-based ensemble of deep domain adaptation under inhomogeneous operating conditions for fault diagnosis of a planetary gearbox. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 79118–79127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Feng, Z. Deep subclass alignment transfer network based on time–frequency features for intelligent fault diagnosis of planetary gearboxes under time-varying speeds. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2022, 33, 105010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Lin, W.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Z.; Li, W. Fault diagnosis of gearbox driven by vibration response mechanism and enhanced unsupervised domain adaptation. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 61, 102460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Du, M.; Yang, Y. Intelligent Fault Diagnosis of Planetary Gearbox Across Conditions Based on Subdomain Distribution Adversarial Adaptation. Sensors 2024, 24, 7017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Shi, B.; Feng, Z.; Tang, J. An unsupervised domain adaptation method for intelligent bearing fault diagnosis based on signal reconstruction by cycle-consistent adversarial learning. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 18477–18485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicilia, A.; Zhao, X.; Hwang, S.J. Domain adversarial neural networks for domain generalization: When it works and how to improve. Mach. Learn. 2023, 112, 2685–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, C.; Wei, Z.; Lu, F. An online milling deformation prediction method for thin-walled features with domain adversarial neural networks under small samples. Comput. Ind. 2025, 172, 104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Zuo, R. Domain adversarial neural network for mapping mineral prospectivity. Math. Geosci. 2025, 57, 471–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Peng, F.; Li, H.; Huang, J.; Sun, G. Cross-domain health status assessment of three-phase inverters using improved DANN. J. Power Electron. 2023, 23, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Gong, G.; Li, G.; Chun, L.; Peng, P.; Li, W. A general multi-source ensemble transfer learning framework integrate of LSTM-DANN and similarity metric for building energy prediction. Energy Build. 2021, 252, 111435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Zhu, Y. Domain-Adaptive Transformer Partial Discharge Recognition Method Combining AlexNet-KAN with DANN. Sensors 2025, 25, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Wang, Y. Domain-specific sentiment analysis for tweets during hurricanes (DSSA-H): A domain-adversarial neural-network-based approach. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2020, 83, 101522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Duan, L.; Gao, S. Domain Adversarial Reinforcement Learning for Partial Domain Adaptation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, M.K.; Sharma, A.; Bajpai, V.; Subudhi, B.N.; Thangaraj, V.; Jakhetiya, V. Encoder and decoder network with ResNet-50 and global average feature pooling for local change detection. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2022, 222, 103501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, N.; Won, C.S. Global–local feature learning for fine-grained food classification based on Swin Transformer. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, L.; Ma, J. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on STFT-deep learning and sound signals. Shock. Vib. 2016, 2016, 6127479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Cui, L.; Cheng, W. A review on deep learning in planetary gearbox health state recognition: Methods, applications, and dataset publication. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 35, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, J.; Peng, X.; Wang, J.; He, C. Deep dynamic adaptation network: A deep transfer learning framework for rolling bearing fault diagnosis under variable working conditions. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, G.; Lin, M.; Peng, Z.; Meng, G. An instance and feature-based hybrid transfer model for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery with different speeds. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Block | Parameters | Output Dimensions |

|---|---|---|

| Conv 1 | Convolution kernel: 7 × 7 Output channels: 64 | 112 × 112 × 64 |

| Res-1 | 2 Convolution kernel: 3 × 3 Output channels: 64 | 112 × 112 × 64 |

| Res-2 | 2 Convolution kernel: 3 × 3 Output channels: 128 | 56 × 56 × 128 |

| Res-3 | 2 Convolution kernel: 3 × 3 Output channels: 256 | 28 × 28 × 256 |

| Res-4 | 2 Convolution kernel: 3 × 3 Output channels: 512 | 14 × 14 × 512 |

| GAP | 512 |

| Block | Parameters | Output Dimensions |

|---|---|---|

| Patch partition | Block size: 4 × 4 Output channels: 96 | 3136 × 96 |

| Linear Embedding | 3136 × 96 | |

| Swin Transformer block 1 | Window size: 7 × 7 Output channels: 96 | 3136 × 96 |

| Patch Merging 1 | Output channels: 192 | 784 × 192 |

| Swin Transformer block 2 | Window size: 7 × 7 Output channels: 192 | 784 × 192 |

| Patch Merging 2 | Output channels: 384 | 196 × 384 |

| Swin Transformer block 2 | Window size: 7 × 7 Output channels: 384 | 196 × 384 |

| Patch Merging 2 | Output channels: 768 | 49 × 768 |

| GAP | 768 |

| Fault Type | Operating Conditions | Number of Samples for Each Operating Conditions | Fault Type Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broken tooth | A, B, C, D, E | 400 | 1 |

| Missing tooth | 400 | 2 | |

| Healthy | 400 | 3 | |

| Root crack | 400 | 4 | |

| Wear gear | 400 | 5 |

| Transfer Tasks | DDC | DAN | DANN | Proposed Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A → B | 84.93 ± 2.08 | 93.81 ± 2.12 | 91.85 ± 1.15 | 97.11 ± 0.56 |

| A → C | 81.86 ± 2.65 | 91.54 ± 1.95 | 94.74 ± 0.87 | 96.92 ± 0.63 |

| A → D | 79.86 ± 3.12 | 92.60 ± 2.21 | 89.48 ± 1.36 | 98.21 ± 0.48 |

| A → E | 82.41 ± 3.35 | 89.69 ± 2.15 | 92.92 ± 1.09 | 98.84 ± 0.43 |

| B → A | 86.33 ± 2.27 | 87.93 ± 2.08 | 92.72 ± 1.22 | 97.67 ± 0.52 |

| B → C | 85.64 ± 1.95 | 88.21 ± 1.98 | 91.28 ± 0.93 | 95.33 ± 0.67 |

| B → D | 82.05 ± 2.81 | 89.74 ± 2.03 | 89.74 ± 1.25 | 97.50 ± 0.59 |

| B → E | 82.85 ± 3.05 | 92.82 ± 2.24 | 93.28 ± 1.05 | 97.64 ± 0.46 |

| C → A | 82.46 ± 2.44 | 92.62 ± 2.01 | 94.45 ± 0.82 | 97.92 ± 0.51 |

| C → B | 78.29 ± 2.76 | 87.42 ± 1.92 | 91.96 ± 1.45 | 98.56 ± 0.35 |

| C → D | 80.67 ± 3.28 | 89.79 ± 2.18 | 89.64 ± 1.65 | 98.93 ± 0.28 |

| C → E | 81.59 ± 2.15 | 90.69 ± 2.05 | 90.87 ± 1.02 | 98.08 ± 0.31 |

| D → A | 76.94 ± 2.59 | 89.92 ± 1.85 | 90.08 ± 1.41 | 97.33 ± 0.45 |

| D → B | 78.89 ± 3.42 | 91.60 ± 2.27 | 90.97 ± 1.29 | 98.71 ± 0.21 |

| D → C | 84.81 ± 2.33 | 91.40 ± 2.09 | 92.08 ± 1.19 | 97.32 ± 0.42 |

| D → E | 76.32 ± 2.98 | 89.04 ± 1.97 | 92.69 ± 1.37 | 99.07 ± 0.26 |

| E → A | 86.22 ± 1.87 | 90.02 ± 2.14 | 92.21 ± 1.24 | 98.94 ± 0.33 |

| E → B | 84.03 ± 3.19 | 87.11 ± 1.88 | 95.13 ± 0.97 | 98.45 ± 0.34 |

| E → C | 81.37 ± 2.61 | 93.89 ± 2.04 | 92.63 ± 1.43 | 96.94 ± 0.62 |

| E → D | 82.36 ± 2.49 | 90.43 ± 2.22 | 95.61 ± 0.71 | 98.38 ± 0.27 |

| Average value | 81.99 ± 2.67 | 90.71 ± 2.12 | 92.22 ± 1.23 | 97.89 ± 0.43 |

| No. | ResNET18 | Swin Transformer | MMD | CORAL | Average Accuracy (%) | MMD Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | √ | — | — | — | 92.92 | 0.487 |

| 2 | √ | √ | — | — | 94.47 | 0.451 |

| 3 | √ | — | √ | — | 95.74 | 0.107 |

| 4 | √ | — | — | √ | 94.83 | 0.124 |

| 5 | √ | — | √ | √ | 96.68 | 0.018 |

| 6 | √ | √ | √ | 98.12 | 0.020 | |

| 7 | √ | √ | √ | √ | 98.84 | 0.013 |

| Method | Training Time (min) | Inference Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| DANN | 3.574 | 1.045 |

| Proposed method | 5.815 | 1.324 |

| Transfer Tasks | DDC | DAN | DANN | Proposed Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 → 1 | 86.73 ± 2.75 | 91.71 ± 2.05 | 93.04 ± 1.85 | 96.17 ± 1.03 |

| 0 → 2 | 88.21 ± 2.38 | 92.50 ± 2.34 | 93.57 ± 1.73 | 95.50 ± 0.95 |

| 1 → 0 | 78.24 ± 3.21 | 88.38 ± 2.45 | 89.47 ± 2.05 | 97.24 ± 1.08 |

| 1 → 2 | 81.23 ± 2.92 | 94.12 ± 1.98 | 93.73 ± 2.12 | 98.78 ± 0.87 |

| 2 → 0 | 79.26 ± 3.65 | 92.49 ± 2.58 | 92.88 ± 1.91 | 97.54 ± 1.02 |

| 2 → 1 | 80.54 ± 3.09 | 92.74 ± 2.21 | 93.67 ± 2.01 | 98.68 ± 0.84 |

| Average value | 82.37 ± 3.00 | 91.99 ± 2.27 | 92.73 ± 1.95 | 97.32 ± 0.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Wang, A.; Sun, H.; Xia, X. Research on Transfer Learning-Based Fault Diagnosis for Planetary Gearboxes Under Cross-Operating Conditions via IDANN. Information 2025, 16, 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121112

Wang X, Wang A, Sun H, Xia X. Research on Transfer Learning-Based Fault Diagnosis for Planetary Gearboxes Under Cross-Operating Conditions via IDANN. Information. 2025; 16(12):1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121112

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaolu, Aiguo Wang, Haoyu Sun, and Xin Xia. 2025. "Research on Transfer Learning-Based Fault Diagnosis for Planetary Gearboxes Under Cross-Operating Conditions via IDANN" Information 16, no. 12: 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121112

APA StyleWang, X., Wang, A., Sun, H., & Xia, X. (2025). Research on Transfer Learning-Based Fault Diagnosis for Planetary Gearboxes Under Cross-Operating Conditions via IDANN. Information, 16(12), 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121112