Abstract

Detecting active failures is important for the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). The IIoT aims to connect devices and machinery across industries. The devices connect via the Internet and provide large amounts of data which, when processed, can generate information and even make automated decisions on the administration of industries. However, traditional active fault management techniques face significant challenges, including highly imbalanced datasets, a limited availability of failure data, and poor generalization to real-world conditions. These issues hinder the effectiveness of prompt and accurate fault detection in real IIoT environments. To overcome these challenges, this work proposes a data augmentation mechanism which integrates generative adversarial networks (GANs) and the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE). The integrated GAN-SMOTE method increases minority class data by generating failure patterns that closely resemble industrial conditions, increasing model robustness and mitigating data imbalances. Consequently, the dataset is well balanced and suitable for the robust training and validation of learning models. Then, the data are used to train and evaluate a variety of models, including deep learning architectures, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory networks (LSTMs), and conventional machine learning models, such as support vector machines (SVMs), K-nearest neighbors (KNN), and decision trees. The proposed mechanism provides an end-to-end framework that is validated on both generated and real-world industrial datasets. In particular, the evaluation is performed using the AI4I, Secom and APS datasets, which enable comprehensive testing in different fault scenarios. The proposed scheme improves the usability of the model and supports its deployment in a real IIoT environment. The improved detection performance of the integrated GAN-SMOTE framework effectively addresses fault classification challenges. This newly proposed mechanism enhances the classification accuracy up to 0.99. The proposed GAN-SMOTE framework effectively overcomes the major limitations of traditional fault detection approaches and proposes a robust, scalable and practical solution for intelligent maintenance systems in the IIoT environment.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence enables data-driven approaches to predict equipment failures, which is called predictive maintenance [1]. It often helps the industry reduce the risk of equipment failures. Consequently, it mitigates costly and unscheduled downtime. This shift help the industries move away from traditional reactive or preventive maintenance techniques to predictive maintenance. In more industries, traditional defect management focuses on the repair or periodic replacement of equipment after failure, such as replacing worn-out motors [2]. In many industrial setups, predictive maintenance can be carried out using the information received through the data collected from various sensors. The collected data are then analyzed to track machinery health and performance in real time [3,4]. These sensors can measure several important factors, including temperature, vibration, pressure, and flow. Patterns, abnormalities, and possible signs of deterioration or future malfunctions are then analyzed using the collected data through installed sensors. Conventionally, equipment maintenance is performed following the defined schedules using the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) [4]. Due to the predictive strategies, the maintenance structure is rapidly changing with the technological advancements of the fourth industrial revolution [5]. The IIoT technology is employed in a business setting where digital technology, internet connectivity, and cloud platforms are integrated with real industrial machines, equipment, sensors, and other digital assets [6,7]. The main goal of the IIoT is to provide businesses with the tools they need to collect, monitor, analyze, and use data to streamline operations, increase productivity, and make informed decisions, especially for small devices or when a maintenance problem occurs during a device’s operation [8]. The IIoT also has the potential to support new business models and revenue streams. The data collected from the sensors embedded with the industrial equipment can be used to provide particular services, including healthcare services [9,10], performance analysis, and remote monitoring [11]. This advancement to data-driven services has the potential to increase competitiveness, enhance user experience, and identify opportunities for creative connections and collaboration [12]. The IIoT continues to change the face of industries in manufacturing, energy and agriculture. It can help the manufacturers achieve greater precision and flexibility by implementing IIoT-enabled smart manufacturing approaches. For example, in the energy industry, it is utilized to optimize energy, strengthen the integration of renewable energy sources, and enhance network performance [13,14].

For most industrial environments, the predictive maintenance techniques are employed to reduce costs as well as increase equipment performance and life. As a result, it reduces risk and increases safety. By tracking abnormalities, machine learning can predict maintenance problems such as unusual vibrations or temperature spikes [15,16]. Similarly, the IIoT gives opportunities to design new architectures as resource methods [17] as well as increase system performance and reduce cyber threats [18]. The IIoT brings connectivity, automation and data-driven decision making, bringing significant changes to manage their operations such as remote monitoring systems. The IIoT enables businesses to enhance their productivity levels, efficiency and creativity by bring the automation and the integration of industrial equipment such as machines, sensors and gadgets into a networked environment. These connected sensor nodes collect real-time data from industrial operations, including manufacturing processes, supply chains, logistics and energy consumption. The data are then sent to a centralized platform where powerful analytics and machine learning algorithms process it into actionable insights [19]. Machine learning models can be used to predict the remaining useful life (RUL) using advanced deep learning techniques [20,21].

Predictive maintenance is an important technique in industrial systems to avoid unplanned equipment breakdown. Compared to preventive or reactive maintenance, where it acts after the failure has occurred or on a time-based schedule, predictive maintenance enables timely action based on actual machine conditions. This is accomplished mainly through technological advancements in the IIoT, where sensor-enabled devices monitor operation parameters such as temperature, pressure, vibration, and flow in real time. Real-time sensor measurements are the foundation of smart decision making and predictive fault prediction. While they are helpful, predictive maintenance models are typically marred by imbalanced datasets, which is primarily because failure occurrences are sparse compared to regular operating information. Machine learning models trained on such skewed data will end up performing badly in identifying minority class instances, which in this scenario refer to the failure states of interest. To counter the problem, synthetic data generation techniques are employed to synthetically oversample the minority (failure) classes [22].

The proposed GenIIoT is a two-step hybrid framework that solves the tradeoff between the stability of the SMOTE and the realism of GAN-based data synthesis. The SMOTE is first applied to expand the minority class and stabilize GAN training, which would otherwise fail due to the extremely small number of fault samples. In the second stage, the GAN performs nonlinear refinement on SMOTE-generated data and learns the complex IIoT fault distribution. It generates high-fidelity synthetic samples () that are more diverse and realistic than interpolation-based methods, effectively addressing the limitations of SMOTE alone.

Two algorithms have been employed for synthetic data generation: the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) and generative adversarial networks (GANs). However, there are some practical differences when applied to IIoT-based predictive maintenance. The SMOTE is light in computation because it creates new instances of the minority class by linear interpolation. It corrects the imbalance but does not exactly follow the variability to replicate the real-world complexity of faults [23]. Conversely, GANs generate data more close to real data, while the variational autoencoders (VAEs) produce overly smooth data. GANs can better learn the data distribution and thus capture complex fault behaviors. Similarly, while denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPMs) have high-quality generation capability, the high training cost and slow generation speed might limit their use in real-time industrial environments [23].

GANs can create high-fidelity synthetic data that are highly comparable to real IIoT fault patterns, which is critical to train trusted proactive models. Compared to VAEs, which create blurred or averaged samples, or DDPMs, which are too computationally demanding for resource-constrained IIoT edge devices, GANs offer a balance between sample fidelity and efficiency [12]. The SMOTE extends GANs to address class imbalance in fault datasets, which is a common issue in the IIoT, through local interpolation. Although DDPMs or VAEs can also generate synthetic data, the simplicity and low computational complexity in SMOTE make it more efficient for real-time fault management. The main contribution is the hybridization of GANs and the SMOTE to take advantage of their complementary strengths where GANs produce diverse fault scenarios and the SMOTE fine-tunes minority-class samples for maximizing classifier fairness [24]. Furthermore, it addresses the dynamic nature of IIoT faults’ non-stationary distributions using the feedback mechanism wherein the output of GAN is recursively validated against real-time fault logs for adaptive sample quality [19,25,26].

Abundant failure data are required for particular equipment for its on-time management using predictive maintenance. A GAN is a technique used to generate data. Similarly, SMOTE is a data-generated technique used in cases of data inadequacy. Machine learning models such as support vector machine (SVMs), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), and decision tree classifiers are used for predictive maintenance. Deep learning models such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) are used for predictive maintenance. The proposed method aims to develop a new and useful predictive maintenance system to assist in equipment maintenance. The core contributions of the proposed work are outlined below:

- A generative AI-enabled predictive maintenance system framework is proposed to proactively predict equipment faults before they occur within an IIoT network.

- The generative AI framework consists of data-generated techniques, including the SMOTE and GANs: the former is skilled at balancing class distribution and producing synthetic failure data, while the latter enables the generation of failure data with unmatched realism and diversity. It mimics the intricate behaviors of real industrial machinery, producing predictive data for maintenance.

- Three different data categories, i.e., real, GAN-generated, and SMOTE-generated, are applied to machine learning to evaluate their precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy performance.

- The IIoT network performance is measured using inter-data with a machine learning models comparison as well as an inter-model comparison of machine learning models, such as SVM, KNN, and DTC, and deep learning models, such as CNN and LSTM.

2. Related Work

Class imbalance, where minority groups are underrepresented, creates major challenges in real-world machine learning, leading to biased models and unreliable evaluations. The data augmentation techniques such as the SMOTE and GANs individually help mitigate this problem, but they have notable limitations. This review introduces a unified taxonomy that classifies the causes, types, and effects of class imbalance in various ML tasks. It also explores recent advances in hybrid models combining the SMOTE and GANs and evaluates related datasets, metrics, and methodologies. This study provides practical insights and outlines future research directions to effectively manage class imbalance in machine learning applications [27]. In the digital age, effective transaction fraud detection (TFD) is essential to ensure financial security. The significant class imbalance, in which the number of legitimate transactions significantly exceeds the number of fraudulent transactions, is a significant challenge for TFD models to accurately identify fraudulent patterns. While existing sample-balancing strategies effectively address class imbalance in many contexts, they often fall short in TFD due to the sophisticated concealment tactics of fraudsters, leading to apparent behavioral overlap between fraudulent and legitimate transactions. In this paper, a novel generative adversarial network-based hybrid sampling method (GANHS) is proposed to effectively address the class imbalance issue. GANHS employs a dual-discriminator generative adversarial network to generate synthetic samples that accurately reflect the characteristics of fraudulent activity, while an adaptive neighborhood-based undersampling technique refines these samples to minimize overlap with legitimate samples. By producing high-quality samples, this hybrid strategy not only increases the model’s capacity to identify fraud tendencies but also strengthens its resistance to highly concealed fraudulent activity. With gains of 0.5–8.7% in mean F1-score and 1.0–7.0% in mean G, GANHS outperforms its rivals in experiments conducted on public and real-world datasets, underscoring its enormous potential to increase the dependability and efficacy of TFD systems in intricate and high-risk financial scenarios [28].

A significant contribution to predictive maintenance in the oil and gas industry was made by [29] who used large language models (LLMs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) to enhance early problem diagnosis and maintenance planning. High sensor noise and inadequately tagged failure data are frequent issues for traditional predictive maintenance systems, the study emphasized. Paroha proposed employing GANs to improve dataset balance, produce realistic-looking artificial sensor signals, and help machine learning models better identify rare failure patterns. Additionally, textual reports and maintenance logs are examined using LLMs, which provided contextual information to support forecasts based on sensors. This coupled approach demonstrated improved accuracy, stability, and operational reliability, highlighting the potential of generative AI to support data-driven and energy-efficient decision making in industrial settings [30].

Due to Industry 4.0’s rapid development, there are now more opportunities than ever before to apply artificial intelligence (AI) in industrial processes. One of the AI paradigms, generative adversarial networks (GANs), has developed into a powerful tool that can create simulated datasets that appear realistic. Predictive maintenance, which aims to foresee likely equipment breakdowns and optimize maintenance practices, frequently faces issues with data shortages and class imbalance. This is particularly valid for critical but rare failure scenarios. This study explores how GANs can simulate equipment failure scenarios, increase model accuracy, and close gaps in predictive maintenance datasets. GAN-based techniques are investigated for generating synthetic sensor signals, failure patterns, and degradation trajectories to enhance prediction models. The technique includes a detailed analysis of GAN topologies, training strategies, and validation procedures. The discussion evaluates GAN applications across several industries, points out problems like overfitting and domain adaptation, and considers the ethical and legal implications of producing synthetic data. Findings indicate that GANs could transform predictive maintenance by reducing unplanned downtime and enabling sound, data-driven decision making [28].

To increase the forecast accuracy necessary for predictive maintenance, a number of techniques have been put out and progressively improved. Cutting-edge research is conducted on deep adversarial learning, intelligent manufacturing systems, predictive maintenance strategies, and AI techniques, such as RNNs, that improve the lifespan and functionality of industrial machinery [31]. Because of the growing number of sensors and functional complexity, intelligent manufacturing systems are more likely to make mistakes that could result in large losses [32]. Conventional maintenance techniques, like reactive and preventive maintenance, are ineffective because they take up too much time and money and cannot handle forecasting and real-time decision-making issues at the same time [33]. A potent substitute is predictive maintenance (PdM), which is made possible by machine learning algorithms. For instance, LSTM-GAN, a revolutionary deep adversarial learning technique, has been proposed to address problems like mode collapse and vanishing gradients. While the GAN component aids in the generation of synthetic fault data, hence resolving the issue of data imbalance and lack of error samples, the LSTM component gains from long-term dependency learning, which improves forecasting [34].

Prediction and maintenance decisions are the two key components that make up the PdM model. These modules employ AI to assess the state of the machine and estimate the likelihood of faults, which are subsequently converted into workable maintenance schedules. With a 99% fault prediction accuracy in equipment diagnostics, LSTM-GAN models have shown great promise for industrial IoT-based settings [35]. The significance of creating synthetic data with GANs has also been highlighted by recent research. To guarantee that these synthetic data accurately reflect the statistical characteristics of actual data, quality control is necessary. When paired with GANs, data balancing techniques like the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) enhance learning by resolving class imbalance, which is a prevalent problem in fault detection datasets. A hybrid SMOTified-GAN method is proposed that improves F1-scores in classification tasks by 9% [36]. Industrial equipment’s remaining useful life (RUL) is predicted using RNN-based architectures such as LSTM and GRU. Tasks involving temporal dependencies in sequence learning are especially well suited for these models. For instance, multivariate time-series defect data have been synthesized using gated recurrent units (GRUs) in conjunction with conditional GANs (C-GANs), which has improved RUL estimation accuracy by 0.15. Predictive defect management in the context of smart construction includes Building Information Modelling (BIM) in conjunction with GANs and IoT. These technologies enhance fault monitoring systems and enable real-time data flow for facility management. Although BIM and IoT are becoming more popular, there are still sparse yet promising studies integrating these technologies into federated learning systems. Automated generative models and unsupervised learning have also been investigated for steganography and facial recognition applications. Visual inspection systems for manufacturing environments may benefit from the cross-applications of these GAN-based models, which concentrate on feature disentanglement and latent space manipulation [37].

Intensive errors that may cause extremely large losses are pressured by the intelligent manufacturing system’s increasing number and functional diversification. The disadvantage of passive, or any other conventional maintenance methods, is that the aforementioned processes take a lot of time and are unproductive. In addition, it is almost impossible to predict the forecasting and maintenance requirements of an intelligent manufacturing system simultaneously, whereas the basic preventive maintenance process utilizes solely one model [9]. Consequently, this paper proposes an innovative predictive maintenance (PdM) method: an LSTM-GAN deep adversarial learning method planned to be more prolonged. Since the LSTM network has a long-term dependency, it can cure vanishing gradient and mode collapse from GAN. The elements of the predictive maintenance model are the two prediction models and the maintenance decision model. Specifically, certain assessments concerning the state of the machine and possible failures can be provided by the parameters created using the above-mentioned prediction models. Later, the maintenance decision model communicates the maintenance plan to the maintenance personnel. LSTM-GAN is an intelligent manufacturing system for equipment diagnostics and prediction. In particular, the error prediction accuracy reaches up to 99%.

By applying IIoT data and RUL evaluations, PdM and AI enhance the industry’s productivity with minimal maintenance downtime [8]. The majority of printed studies take into account the availability of training data, as well as several normal and erroneous samples, when analyzing different scenarios for machine state. Although there are no error data in the real-world scenarios, it is suggested that a non-uniform training set should be adopted. Since this failure leads to the non-prediction of errors in RUL estimation methodologies, this problem results in erroneous outcomes [38,39]. A brand new forecasting paradigm grounded on DGRU networks and C-GANs is introduced. Multivariate errors can be instantiated by the framework, and thus, the data imbalance issue can be solved by the proposed framework, enabling the accurate estimation of RULs of complex systems. As opposed to earlier works using imbalanced data on the C-MAPSS dataset [40], the authors showed that DGRU training, data augmentation, and learning error samples with a noise basis distribution for RUL prediction have increased accuracy by 0.15 [11].

Similarly, one of the target areas of predictive fault management is the monitoring and maintenance of buildings. For this purpose, Building Information Modeling (BIM) is linked with GANs [41]. According to prior research, building maintenance management mainly involves appropriate maintenance parameters and standards. However, these limitations also imply that the purpose of this research is to work with modern technology to introduce a program of predictive maintenance. BIM and the IoT can enhance FMM by exchanging data, facilitating the management of facilities, and exploring efficient solutions [42,43]. While BIM and the IoT have been employed in the industry, and multiple concepts employing the mentioned approaches exist, their integration in federated machine learning is still rather limited. A PdM planning framework is introduced, centered on analyzing data for FMM to enhance the maintenance approaches regarding construction equipment. It consists of two layers: the database layer and the information layer. The basis of this technology is in the IoT and BIM. The information layer gathers information from the FM systems, IoT networks, and BIM models used to support the predictive maintenance notations. The application layer can be divided into four submodules [44].

A new architecture has been developed to identify human faces using the unsupervised and automated learning of various facial features [45]. It also aids in creating new images of variants using freckles and hair. It makes synthesis controllable. It is important to note that the utilized GAN generator advances the state of the art in conventional distribution quality attributes, and it results in established changed characteristics and a sufficiently accurate extraction of the latent dimensions of variability. It deals with interpolation and disentanglement; for these qualities to be enhanced, a new method was developed, which is better for any generator that is used in GANs. Distortion in steganography is carried out using GANs, whereas a media object that is used in digital communication to accommodate other information refers to steganographic distortion. This is an important constituent of the covert communication method whose name is steganography. The objective of such systems is to conceal the existence of secret communication.

Alhiyari and Domartzaki introduced SMOGAN (synthetic minority oversampling with GAN refinement), which is a two-stage oversampling framework for imbalanced regression problems. In the first step, SMOGN generates initial synthetic samples in sparse regions using interpolation. In the second step, a distribution-aware GAN (DistGAN) refines these samples by reducing MMD losses to better align them with the real data. This blend of SMOTE-based and GAN-based techniques improves the diversity and realism of synthetic data, enhancing model performance on rare target values [46]. GACNet (Generate Adversarial-Driven Cross-Aware Networks) improves wheat variety identification from hyperspectral images. The framework integrates a semi-supervised GAN (SSGAN) for realistic data augmentation and a cross-aware attention network (CANet) for effective feature extraction using 3D and 2D convolutions with an embedded attention mechanism. Using the Hyperspectral Wheat Variety Dataset (HWVD) of 4560 samples from 19 categories, GACNet achieved superior accuracy over existing methods, demonstrating the strength of GAN-based enhancements and attention-driven learning in hyperspectral classification [31]. AGANet (Attention-Guided Generative Adversarial Network) is used to overcome data scarcity in hyperspectral corn seed detection. The model integrates attention modules and a classifier within the GAN framework to generate realistic, class-specific hyperspectral images, enhancing spatial feature extraction and reducing the need for large labeled datasets. Experimental results showed that AGANet produces highly realistic synthetic samples, improving data augmentation for deep learning-based agricultural imaging [32].

In digital twin (DT) systems, generative adversarial networks (GANs) play an important role by generating synthetic sensor data and simulating rare fault scenarios that are difficult to capture in real operation [47]. The generator creates realistic data reflecting potential system behavior, while the discriminator differentiates between real and synthetic data, thereby continuously improving the quality of generation. This process increases data diversity, addresses data imbalances, and supports more accurate fault detection and predictive maintenance. By integrating GANs, DT systems can model degradation, predict failures in advance, and enable real-time, data-driven decision making in Industry 4.0 and 5.0 environments [48].

Conditions for applying remote sensing data for land cover include the classification of the diverse and detailed land use and cover classifications and reliable classifications [24]. In the field of terrestrial remote sensing, the random forest, a strongly developed method of machine learning classifier, has not been globally publicized as the common pattern recognition mechanism. Also, the specific functions incorporated in the RF can perform the basic methods for imputing missing values among several data analysis techniques. Other data analysis tasks performed by the RF include survival, regression, classification, and unsupervised learning. In detail, this paper seeks to discuss the efficiency of the algorithm using factors such as the mapping precision level, the mapping scale, and the level of noise. The Kappa Coefficient values of the RF of and overall accuracy of the result are 92% and 0, respectively. More than just improving the RF model with one decision tree, a full improvement is noticed at p < 0.00001 McN.

Another challenge that affects classifiers is a severe class imbalance in the dataset. This is due to most of the positive classifications that lead to a poor prediction for the training sets with a high True False Rate (TPR) but low True Negative Rate (TNR) [36]. In the proposed method, the SMOTE and GANs are combined with the knowledge transfer method, and a two-stage resampling method is introduced. In case higher-order GANs have problems with minority data alone, we transform overgeneralized or unrealistic samples of SMOTE into real data. Hence, the approach involves the use of the above-mentioned small set of pre-sampled data obtained from the SMOTE to train rather than randomly generated data. Experimental works presented for different benchmark datasets reveal that the quality of the samples belonging to the minority class is better. It noted a improvement to the comparatively conventional algorithm in the F1-score evaluation criterion for the classification of given data using a neural network; the resampled data from the minority class must be in the same proportion as the data in the majority class. Furthermore, to analyze the results on the entire dataset without applying any technique of data augmentation, experiments are performed [17].

2.1. AI Techniques in Predictive Maintenance

Various methods have been proposed and gradually advanced to improve the forecast accuracy essential for predictive maintenance. The following section describes the state-of-the-art research on deep adversarial learning, predictive maintenance approaches, intelligent manufacturing systems, and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques, including RNNs enhance the lifetime and performance of industrial machines [49]. Intelligent manufacturing systems are increasingly facing errors that may cause significant losses due to the rising number of sensors and functional complexity [35]. Traditional maintenance strategies, such as reactive and preventive maintenance, are inefficient because they consume excessive time and resources, and they are unable to simultaneously address forecasting and real-time decision-making challenges. Predictive maintenance (PdM), supported by AI models, has emerged as a powerful alternative. For example, a novel deep adversarial learning approach known as LSTM-GAN has been proposed to tackle issues such as vanishing gradients and mode collapse. The LSTM component benefits from long-term dependency learning, which enhances forecasting, while the GAN component helps generate synthetic fault data, thereby addressing the problem of data imbalance and lack of error samples.

The PdM model generally consists of two core modules: prediction and maintenance decision. These modules use AI to analyze the machine’s condition and provide fault probability estimations, which are then translated into actionable maintenance plans. LSTM-GAN models have demonstrated a high fault prediction accuracy up to 99% in equipment diagnostics, showing significant potential in industrial IoT-based environments. Recent work has also emphasized the importance of synthetic data generation using GANs. However, the quality control of this synthetic data is essential to ensure it mirrors the statistical properties of real data. Data-balancing methods, such as the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE), when combined with GANs, further improve the learning process by addressing class imbalance, which is a common issue in fault detection datasets.

2.2. RUL Estimation Using RNNs and GANs

Remaining useful life (RUL) prediction in industrial equipment has been a common application of artificial intelligence, particularly RNN-based architectures like LSTM and GRU [49]. Tasks involving temporal dependencies in sequence learning are especially well suited for these models. For instance, multivariate time-series defect data have been synthesized using gated recurrent units (GRUs) in conjunction with conditional GANs (C-GANs), which has improved RUL estimation accuracy by 0.15. Predictive defect management in the context of smart construction includes Building Information Modelling (BIM) in conjunction with GANs and IoT. These technologies enhance fault monitoring systems and enable real-time data flow for facility management. Despite their growing popularity, BIM and IoT integration into federated learning infrastructures is currently limited but shows promise. Unsupervised learning and automated generative models have also been explored for facial recognition and steganography applications. These GAN-based models focus on feature disentanglement and latent space manipulation, which offer potential cross-applications in visual inspection systems for manufacturing environments. The hybrid data augmentation framework proposed in the paper, combines generative adversarial networks (GANs) and the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE), employs a two-stage resampling method based on knowledge transfer. The collaborative mechanism between both the technologies is as follows.

2.3. Preliminary Minority Sampling (Role of SMOTE)

The SMOTE is first used to generate a small set of pre-sample data from the minority class (failure sample). The strength of the SMOTE lies in balancing the class distribution through interpolation. However, the data generated by SMOTE may be “noisy and unrealistic”.

2.4. Synthetic Data Refinement and Diversification (Role of GAN)

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) are trained using this small set of pre-sampled data obtained from the SMOTE to train their generators rather than using randomly generated data. This approach aims to take advantage of GAN’s superior ability to transform the SMOTE’s overgeneralized or unrealistic samples into realistic data. GANs increase quality by generating failure data with “unmatched realism and diversity”, effectively fine-tuning the minority class samples generated by the SMOTE. In short, the SMOTE performs an initial, low-complexity oversampling, and the GAN subsequently acts as a refinement mechanism to increase the accuracy and diversity of those initial synthetic samples.

3. Proposed GenIIoT Mechanism

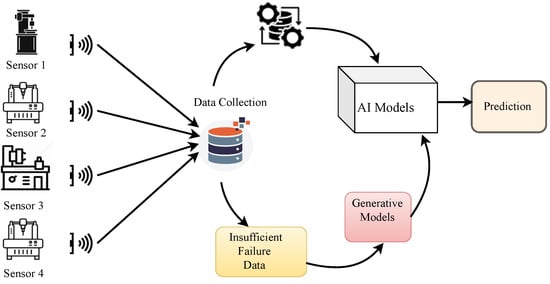

A framework is proposed for predictive maintenance using generative learning to predict the fault in machines prior to its occurrence, as shown in Figure 1. Three different datasets such as APS, SECOM an AI4I with different categories and sample count as illustrated in Table 1 are used.

Figure 1.

Proposed framework for predictive maintenance using generative learning.

Table 1.

Class distribution across predictive maintenance datasets.

3.1. Artificial Intelligence Dataset for Industry (AI41)

The dataset contains 10,000 samples discretized from the time series, with 14 features, which include seven thermal, three mechanical, one rotary, one cutting, and two fault types, including thermal, feed, surge, torque, and random faults. A binary variable identifying the status of a machine at the time of taking a sample as a machine failure flag (1 for failure, 0 for normal), reveals 96.6% of data for active machines and 3.4% of failed ones, as illustrated in Table 2. Data were obtained from the AI4I 2020 dataset [50], which collects real-time measures through sensors for forecasting servicing needs. Changes in temperature, vibration, and rotational speeds are measured and recorded to capture both healthy and faulty states to inform the evaluation of failure modes. As for the 3.4% failure rate, oversampling techniques are used such as the SMOTE. To maintain the homogeneity of data, the features are standardized in terms of temperature, speed, and torque values. Some of the fault types have been converted into 0 and 1 to ensure they are easily distinguishable. This confirms and corrects for the missing data and also for the duplicity of some data.

Table 2.

Data distribution across different sampling methods.

3.2. Semiconductor Manufacturing (SECOM) Dataset

There are 1567 samples in total with 592 features in this dataset. Each sample stores one or more sensor readings collected from the industrial process; parameters may include temperatures, pressures, rotation speed, and various fault signals and symptoms. The dataset also has a Pass/Fail label in which “−1” is given to represent a failure, while “1” is given to describe a successful operation. The data were collected continuously by using various sensors and focused on the operational data of the machinery. The objective was thus to try and establish when the machinery fails to make some useful inputs into the models used in prescriptive maintenance, the dataset information is illustrated in Table 1.

3.3. Air Pressure System (APS) Dataset

This dataset includes 60,000 samples, each containing 171 features related to sensor readings and operational metrics from industrial equipment, as shown in Table 1. The samples are labeled in the class column, where pos indicates a failure and neg indicates normal operation. Each feature captures measurements such as temperature, pressure, and flow rates for various components within the system. Data were collected from APS (Air Pressure System) units in trucks, where sensors monitored conditions that might lead to a failure. These data help identify failures and support predictive maintenance models by capturing conditions before both normal operations and breakdowns.

3.4. Data Preprocessing Techniques

Thorough preprocessing procedures are used to guarantee the robustness and dependability of the suggested predictive maintenance system. Occasional missing readings from gearbox problems or sensor malfunctions make up the dataset. For the numerical properties of the sensors, data imputation methods such as mean imputation are employed. In this method, the missing values are replaced with the feature-wise mean values, aiming to retain the statistical characteristics of each feature and avoid bias. Furthermore, feature normalization enables stable and efficient training of both the GAN and the downstream predictive model. Therefore, the values of the features are scaled into the range [0, 1] employing min–max normalization. It reduces the impact of the significant difference between the feature values that accelerate convergence during training. Prior to synthetic data generation, the dataset is partitioned into training and testing subsets using a stratified split, ensuring that the class distributions, e.g., normal and failure proportions, are preserved. Importantly, synthetic data generation through GAN and SMOTE techniques is applied to the training data to prevent data leakage, as shown in Figure 2. Moreover, data analysis (EDA) is applied to identify and exclude sensor features with near-zero variance or high inter-feature correlation, i.e., Pearson correlation coefficient > 0.95. It reduces redundancy and enhances model generalization. Considering this, explicit outlier removal is avoided to preserve the integrity of real-world operational data, as shown in Figure 1. The data are normalized as

Figure 2.

Comparison of the distributions of real and generated data.

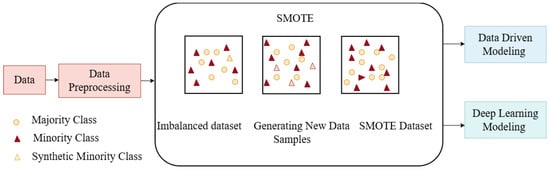

3.5. SMOTE Technique

This technique solves the class imbalance problem prevalent in target data regarding machine learning models. In particular, the class disparity refers to the condition in which one of the classes has considerably fewer samples in contrast with other classes, as shown in Figure 3 [51]. Task B reduces the distorted contribution of the numerous classes to learning by leveling the contribution of classes in the dataset through placing the minority class samples together through synthesized data, as shown in Figure 4. Before performing the balancing of effects of classes, an individual has to decide which class is the minority one that needs to be sampled to bring it to par with another class. However, there are two classes; the ratio in their actual dataset has to be determined first before applying the SMOTE, aiming to increase the percentage of the minority class. It balances the class distribution of the dataset by using a small percentage of data from the minority classes for the improvement of the model generalization, leading to enhanced model performance [35].

Figure 3.

Proposed workflow of machine learning models with the SMOTE.

Figure 4.

Illustration of the SMOTE workflow for minority class oversampling.

The workflow of SMOTE analysis is shown in Figure 3. For this purpose, subsequently, the AI4I dataset is used [50], which has a skewed class distribution, since minority class samples are significantly less compared to the majority class samples. Therefore, a string of characters with a random row N is chosen. Then, its nearby numbers are identified to find the nature of the nearby data. One of the nearest points, which is the closest to the chosen one, is randomly selected using K nearest neighbors (KNN). In this case, when synthesizing the sample, the number of closest neighbors is . For creating a new synthetic sample for SMOTE, feature vectors of the selected sample and the KNN of the selected sample are used [33]. Average measures of KNN for the classification of the sample of a particular minority class are determined by using the Euclidean distance between the chosen minority class and the majority class. The Euclidean distance between the two points and can be defined as [52]

It generates synthetic samples by linear interpolation between the feature vectors of the selected sample and some of its nearest neighbors. A new synthetic instance, , from an original minority sample and a randomly selected neighbor , can be generated as

where represents the newly generated synthetic sample, is the randomly selected minority class instance, represents a neighbor chosen from the k-nearest neighbors of , and is a random number drawn from a uniform distribution between 0 and 1. As a preprocessing step, data imputation is carried out to replace the missing values using the mean of the whole feature represented as

where denotes the value assigned to replace a missing entry in the dataset. The term refers to the mean of the corresponding feature column, which was calculated from the available data. Here, N represents the total number of non-missing observations for that feature, and indicates the ith observed value within that feature. These parameters are collectively used to compute the imputed value based on the existing observations.

The SMOTE allows the creation of a ratio of up to 20% for the failure class and 80% for the non-failure class. It minimizes the dominance of the majority class through an approach that deals with the generation of new noisy data as described in Algorithm 1. Thus, the data obtained by the SMOTE are noisy and unrealistic, providing the enhancement of the lower impact of the generated non-failure data where the same challenge persists. This could help balance the effect of the major class by using the factors in the contending classes and typing in more classes. Hence, to offset the impact of the minority class, through data augmentation, the weights associated with the non-failure data can be created and augmented [34].

| Algorithm 1 SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

|

3.6. GANs Architecture

3.6.1. Proposed GAN Architecture

The proposed generative adversarial network (GAN) consists of two fully connected components: a generator and a discriminator, as shown in Table 3, which are both implemented using fully connected layers tailored to the dimensionality of the input feature space. The generator is composed of four dense layers designed to transform a 100-dimensional latent noise vector into a synthetic feature sample resembling the real data distribution. The generator follows the architecture with an input layer of size 100, which is followed by dense layers with 128, 256, and 128 units, respectively, and finally an output dense layer matching the size of the feature vector. ReLU activation functions are used in all hidden layers. In contrast, a sigmoid activation is applied at the output layer to ensure the generated features remain within a normalized range, as shown in Table 4. The discriminator is composed of three dense layers that process input samples to classify them as real or synthetic. Its architecture includes an input layer matching the feature vector size, followed by hidden dense layers of 128 and 64 units, and a final output layer with one unit for binary classification. LeakyReLU activation is employed in the hidden layers to support better gradient propagation, while the output layer uses a sigmoid function. Both networks are trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, set to 0.5, and set to 0.999 to ensure training stability and convergence. The loss function represents the standard minimax optimization used to train a GAN,

where G represents the generator network, which produces synthetic samples from a random noise vector, and D is the discriminator network that attempts to distinguish between real and generated samples. Let represent the distribution of the real data used to train the discriminator, and let represent the distribution of the input noise vector, which is typically sampled from a uniform or Gaussian distribution. The discriminator’s output for a real sample x is given by , which represents the probability that x is authentic, while is the discriminator’s output probability for a synthetic sample generated by G.

Table 3.

Sequential architecture of GAN generator and discriminator.

Table 4.

Hyperparameter settings for the proposed GAN model.

3.6.2. Hyperparameter Configuration

A combination of grid search and manual tuning was employed to fine-tune the model’s hyperparameters and mitigate overfitting. The final configuration is summarized in Table 4.

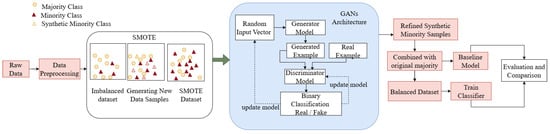

3.7. Machine Learning Models

The prepossessed data is fed to SMOTE to augment the data aiming to enhance the minority class. Then, the the data is fed to GANs to generate the fault data for accurately predicting the faults prior to its occurrence, as illustrated in Figure 5. Machine learning models are trained on the actual data, SMOTE generated data and GANs generated data respectively. The Machine learning models, such as SVM, KNN, and decision tree classifiers, and deep learning models, such as CNN and LSTM, are employed to feed actual data, where 3.4% are in the failure class and 96.6% are non-failure data [50]. The architectures of the LSTM and CNN models used are shown in Table 5 and Table 6, respectively. The performance of these models is low because of the small failure data. Thus, the SMOTE is used to increase the failure dataset. It is conceded that after applying the SMOTE, their findings are ambiguous because it synthesizes noisy data to address the class imbalance. Another employed method in the generation of data is GANs, where after adding newly generated data, the ratios are 20% failure class and 80% non-failure class.

Figure 5.

Proposed workflow model using data generating techniques.

Table 5.

LSTM architecture.

Table 6.

CNN architecture.

Since the failure data are very scarce, it directly affects the accuracy of the models. To have a meaningful impact of machine failure on the model performance, the size of the failures needs to be increased. For this purpose, the SMOTE is used to incorporate meaningful failure data in the dataset for training and testing. Once the data were generated, with 20% failure data and 80% non-failure data, the data were fed to the machine learning models.

In the next step, the failure dataset is generated with the help of the GANs technique, which is then fed to machine learning models for performance analysis [53]. The main difference between the SMOTE and GANs is that the former reduces the class imbalance by the interpolation of available classes, while the latter generates entirely new data considering the existing classes. SVMs can maximize any loss function and can be used both for regression and for classification [54]. The decision trees provide models that can be explained; they show decision-making processes, and KNN is a simple yet effective classification that distinguishes based on the nearest neighbors. Key performance measurement metrics are used to assess the efficacy of a model, such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score [55].

Predictive maintenance deals with equipment state classification using the SVM, which is categorized as normal or failed [13]. The SVM employs different kernel functions, like the polynomial kernel or radial basis function (RBF), for effectively dealing with the nonlinearity of feature relationships. KNN assists in anomaly detection in predictive maintenance, where it works by comparing a data point to the closest points to flag the outlying patterns that require little necessity for fine-tuning of the parameters. Decision trees assist in finding the characteristics and or elements that cause equipment failures. CNNs accommodate the spatial pyramids of data, which helps find anomalous or erroneous regions in machines. Comparatively, LSTM works better on sequential data that would be useful in assisting predictive maintenance, which depends on the data provided with time [16].

The system requirements for this research setup include support for Windows 10/11, Linux, or macOS operating systems. Hardware specifications require a minimum of 8 GB RAM and 4 GB GPU memory, and up to 16 GB RAM and 8 GB or more GPU memory are recommended for optimal performance. Additionally, a minimum of 10 GB of storage space is required to accommodate datasets and models. For improved computational efficiency, an NVIDIA GPU with CUDA support is recommended. The computing resources for the environment utilize Jupyter Notebook 6.5, Python 3.10 with TensorFlow 2.x, including GPU support for CUDA-compatible NVIDIA GPUs. The machine learning and deep learning frameworks rely on TensorFlow/Keras with automatic memory allocation in TensorFlow to ensure the efficient handling of large datasets. The effectiveness of the proposed technique is assessed through a structured evaluation process that combines several complementary strategies. First, hold-out validation is performed using stratified train–test splits (70/30 or 80/20 with fixed random seeds). All preprocessing steps are applied only to the training data, and augmentation methods such as the SMOTE or GANs are restricted to the training portion, while the test set remains entirely real and untouched. In addition, stratified five-fold cross-validation, with optional repetitions, is carried out to provide a more reliable estimate of model performance. Within each fold, preprocessing and class balancing are limited to the training split, and results are reported as the mean with standard deviation, with model selection guided by minority-class metrics such as PR-AUC and F1-score. To evaluate external validity, the pipeline is also applied to independent datasets, including APS and UCI SECOM, and domain-shift experiments are conducted by training on AI4I and testing on APS or SECOM after aligning the features. Further analysis is carried out through ablation studies, in which different class-balancing strategies (no balancing, SMOTE, and GAN-based augmentation), feature subsets, and robustness under controlled label-noise injection are compared. Hyperparameter tuning is performed through grid search within the training data using either nested cross-validation or an inner split, which is followed by retraining on the complete training set. Strict leakage prevention is ensured throughout the evaluation, meaning no synthetic samples or resampling are introduced into validation or test sets, and all preprocessing steps, such as scaling or encoding, are fitted exclusively on training data. Results are primarily reported in terms of PR-AUC and F1-score for the minority class, which are complemented by additional indicators including precision, recall, accuracy, confusion matrices, and threshold analyses derived from precision–recall curves with probability calibration applied when required.

4. Results and Discussion

The similarity between real and synthetic data is evaluated using a distributional comparison. Therefore, the distribution of real and generated data is compared using a histogram. The histogram distribution of key features is illustrated in Figure 2, where the blue and red represent real and GAN-generated distributions, respectively. The alignment of these curves demonstrates that the GAN-generated data resemble the underlying distribution of the original data. This method is commonly used to assess synthetic data fidelity. By integrating these evaluations, the synthetic fault data generated by the GAN closely mirror the statistical properties of the real dataset, supporting its applicability in training more robust predictive maintenance models. The closer the curves align, the better the quality of the data generated. The GAN model hyperparameters are listed in Table 4.

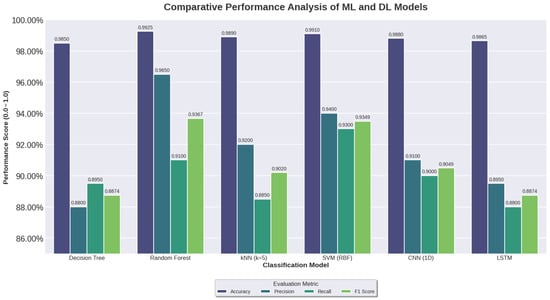

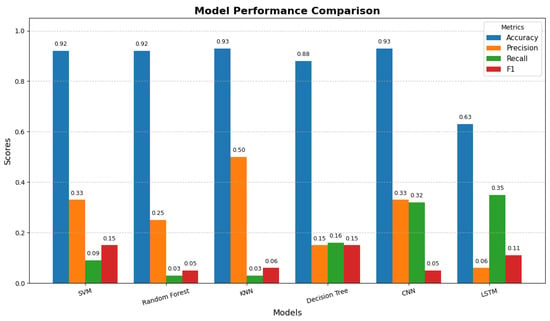

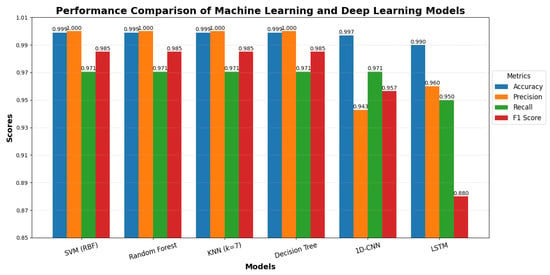

Three categories of data are used: AI4I, APS, and SECOM. The models’ performance is evaluated by feeding the three kinds of data to the models. For example, decision tree classifiers are fed with three types of data and categorized as decision tree classifier with normal data (DTC-normal), decision tree classifier with SMOTE-generated data (DTC-SMOTE), and decision tree classifier with GAN-generated data (DTC-GAN). Hyperparameter tuning for all conventional baseline models, including SVM, KNN, decision tree, random forest, and 1D CNN, in addition to the proposed LSTM architecture, is performed by varying key parameters, such as kernel type, regularization strength, gamma settings, neighborhood size, weighting scheme, tree depth, estimator count, learning rate, batch size, hidden units, dropout rate, and loss functions, with optimal configurations summarized in Table 7. The effectiveness of these models is assessed with key performance metrics as shown in Figure 6, including the accuracy and recall rate, as shown in Figure 7, the F1-score as depicted in Figure 8, and the level of precision as illustrated in Figure 9 using the hyperparameters listed in Table 7. In Figure 9, several models show accuracy and precision values close to 0.999 or 1.0, which is unexpected given the dataset’s strong class imbalance. However, synthetic data generation methods, including GANs and the SMOTE, are used to balance the APS training dataset, which enhanced the model’s ability to correctly identify minority class instances. Consequently, the elevated precision and accuracy scores reflect the effectiveness of the models when trained on a balanced dataset. Mathematically,

Table 7.

Comparison of hyperparameters tested for different models with their optimal values and corresponding classification accuracy.

Figure 6.

Representation of machine learning and deep learning models’ results using AI4I dataset.

Figure 7.

Representation of machine learning and deep learning models’ results using SECOM dataset.

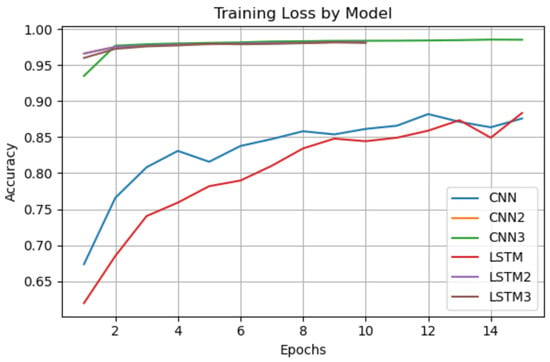

Figure 8.

Accuracy and epochs analysis of CNN and LSTM models.

Figure 9.

Representation of machine learning and deep learning models’ results using APS dataset.

The results of the hyperparameter optimization show differences amongst the models that are examined with the LSTM obtaining the maximum accuracy of 98.84%. Its balanced design (0.0005 learning rate, 32 batch size, 64 hidden units, 0.2 dropout, and binary cross-entropy loss) allowed for an efficient modeling of temporal relationships while reducing overfitting, which is responsible for this performance. With 100 estimators and a depth of 20, random forest came in second at 96.3%, capturing intricate feature interactions without introducing undue volatility. Using an RBF kernel with C = 1 and gamma adjusted to scale, the SVM achieved 95.8% accuracy, offering strong nonlinear decision limits. With five neighbors and distance-based weighting, which prioritized nearby, more pertinent samples, KNN fared best with 93.5%. The 1D CNN closely matched this at 93.8%, with 64 filters, a kernel size of 3, and a 0.0005 learning rate, enabling an effective extraction of local temporal–spatial patterns. The decision tree achieved 90.4% accuracy with a depth of 10 and a minimum split of 5, balancing complexity and generalization. Overall, the results confirm that while all models benefited from targeted hyperparameter tuning, deep learning approaches and specifically, LSTM outperformed classical methods, with random forest offering the strongest traditional alternative.

DTC-Normal demonstrates rather low performance. The reasoning behind this is the presence of very scarce failure data affecting the models’ performance, as shown in Figure 6. Comparatively, DTC-SMOTE and DTC-GAN achieve better results than DTC-Normal in terms of recall, accuracy, and F1-scores, as shown in Table 8. XGBoost achieves the highest accuracy of 0.9978, which is followed by KNN with an accuracy of 0.9966, and random forest with 0.9957. The deep learning models, such as LSTM and DNN, achieve 0.9884 and 0.9810, respectively, and perform well but were outperformed by the ensemble methods. On the other hand, SVM had the lowest accuracy of 0.9822.

Table 8.

Model comparison on test accuracy, parameters, FLOPs, and training time.

The computational efficiency of the models is compared in terms of the number of parameters, FLOPS used, and training time. The DNN has the fewest parameters of 11,009, while random forest has the most: 169,162 nodes. LSTM had a moderate count of 63,329. Comparatively, only neural models have an approximate FLOPs comparison, where LSTM has 126,560 and DNN has 21,888, as illustrated in Table 8. Furthermore, the training time of XGBoost is the lowest with 12.42 s, while SVM with 2587.13 s was the highest among them all due to an extensive grid search to achieve the optimal hyperparameters. The deep learning models have moderate training times due to hyperparameter tuning. The models’ comparison on test accuracy, number of parameters, FLOPS, and training time is summarized in Table 8.

Predictive maintenance (PdM) emerges as a critical application area within the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), relying heavily on time-series sensor data to forecast potential equipment failures. To properly analyze the temporal data, deep learning (DL) architectures and traditional machine learning (ML) algorithms were investigated. Long short-term memory (LSTM), convolutional neural networks (CNN), support vector machines (SVMs), K-nearest neighbors (k-NN), and decision trees (DTs) are among the models that have undergone considerable evaluation.

The suggested LSTM model is compared to a number of cutting-edge classification methods documented in recent research in Table 8. With an accuracy of 98.84% and balanced precision–recall values (99% and 99%, respectively), the results show that the suggested LSTM has significantly improved over the traditional method. In contrast, the random forest model obtained an F1-score of 96.2% and accuracy of 96.3%, while KNN and the 1D CNN obtained accuracies of 93.5% and 93.8%, respectively, and the SVM model also showed impressive results with 95.8% accuracy. On the other hand, the decision tree showed limits in managing the dataset’s complexity, recording the lowest accuracy of 90.4%. While some conventional models are very accurate, the suggested LSTM model has significant advantages when it comes to managing the data’s temporal patterns and sequential dependencies. Because of these features, it is especially well suited for jobs where the sequence and timing of events are crucial to the accuracy of predictions.

Model interpretability is frequently just as crucial in industrial settings as prediction accuracy. Conventional machine learning methods like SVM, KNN, and decision trees are thought to be more interpretable and transparent. Decision trees, for instance, offer easily verifiable decision routes and rules that are accessible by humans as well as domain experts. Similar to this, SVMs provide decision boundaries that are either linear or kernel-based, which facilitates comprehension of the model’s decision-making process. On the other hand, because of their deep architectures and nonlinear transformations, DL models such as CNN and LSTM are frequently regarded as black-box systems. These models are more accurate when dealing with complicated data, but their lack of transparency may make them unsuitable for use in safety-critical or regulated applications [56]. This has increased interest in Explainable AI (XAI) methods, which try to improve the interpretability of DL models. LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanation) is a popular XAI technique [57]. as well as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanation), which offer post hoc justifications for model forecasts. These techniques provide a means of striking a compromise between interpretability and performance for both traditional and deep learning models. A thorough taxonomy of XAI approaches was presented by Arrieta et al., who emphasized that interpretability and accuracy should be taken into consideration when choosing models in crucial domains [56].

The lack of labeled fault data and its imbalance are two of PdM’s biggest problems. Researchers have used generative adversarial networks (GANs) to augment data in order to overcome this. In order to improve model generalization and robustness, conditional GANs (cGANs) are very good at producing synthetic sensor data that correspond to uncommon fault circumstances [37]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that cGANs and LSTM networks can predict RUL more accurately in situations with little labeled data. Another method, the SMOTified-GAN framework, improves fault classification in unbalanced industrial datasets by combining ensemble learning approaches with GAN-based oversampling. These techniques emphasize how crucial synthetic data generation and hybrid learning are to the development of PdM systems [36].

Three distinct datasets, KNN-Normal, KNN-SMOTE, and KNN-GAN, were fed into the KNN model. Among these, the KNN-SMOTE algorithm has better model performance in terms of recall rate, accuracy, and F1-score. In contrast, KNN-GANs perform better in terms of recall but less well in terms of precision. Conversely, KNN-Normal has poor positive classification outcomes. In a similar manner, SVM was fed the three dataset categories, SVM-Normal, SVM-SMOTE, and SVM-GAN. Accuracy, F1-score, and recall measures were used to evaluate the model’s performance. With a marginally higher F1-score, SVM-SMOTE and SVM-GAN outperform SVM-Normal in all three criteria. As illustrated in Figure 9, the argument goes that raising the failure class aids in lowering the false negative and false positive numbers.

However, because of its sequential structure, an LSTM model can assist in determining the impact in order to further analyze the minority class. Three datasets were utilized to assess the LSTM model’s performance for this purpose. However, the model accuracy approaches 87% on real data, on generated data, and up to 97% on merged data. Furthermore, the F1-scores for every dataset reach at least 0.97, which explains the model’s excellent performance in terms of recall and accuracy parameters. Because of its temporal dependencies and structures, the LSTM model has demonstrated its versatility and usefulness in a variety of data situations, particularly when applied to synthetic and mixed datasets, as illustrated in the Figure 8. Dense GANs often struggle to capture complex temporal fault behavior in industrial time-series data because they treat inputs as static feature vectors and lack explicit memory for sequential dependencies. Still, research shows that under certain conditions, they can approximate temporal structures indirectly. For example, a recent study on railway-track fault diagnosis used a basic GAN (on one-channel sequential data) and achieved synthetic samples close to real measurements: when those samples were trained on a CNN classifier using GAN-augmented data, test accuracy rose from 89% to 96% [28].

The CNN model’s performance was assessed using three datasets: produced data, hybrid data, and current data. An F1-score of , a recall rate of , and a precision rate of were obtained on real data. The model performed exceptionally well on generated data, achieving accuracy, an F1-score of , and recall. Additionally, the combined data demonstrated outstanding performance with recall, an F1-score of , and precision. The model exhibits improved predictive power and flexibility across various datasets. The CNN and LSTM models’ accuracy and epochs are examined in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Loss–epochs curve of CNN and LSTM models.

When applied to real data, the SVM outperforms the other traditional machine learning models in terms of accuracy and recall. This heave and swing immediately indicate that the SVM is capable of accurately and promptly predicting positive events in terms of accuracy, as demonstrated by the accuracy and recall comparative study in Figure 6. In a comparable manner, it can identify a high proportion of actual positive events in terms of memory without sacrificing any of the characteristics. Figure 7 illustrates how poorly both the KNN and the DTC perform when tested on actual data in terms of achieving high accuracy and high recall. This is because, as Table 8 demonstrates, these models frequently either incorrectly anticipate the positively labeled samples or misdiagnose positive cases in terms of low recall. The results illustrated in Table 8 show that when considering the optimized traditional models, XGBoost achieved 0.9978 and tuned KNN achieved 0.9966 accuracy compared to the tuned LSTM, which achieved 0.9884. This finding aligns with the established literature: when datasets are relatively small, have limited temporal depth, or exhibit strong feature separability, classical machine learning models often outperform deep learning architectures. In these cases, XGBoost effectively leverages gradient-boosted decision rules to handle nonlinear boundaries, while KNN benefits from well-defined cluster structures in the feature space [58].

Thus, comparing the results of the three models, SVM demonstrates a significantly better accuracy and recall rate than the two other conventional machine learning models when GAN-generated data are applied. Comparatively, the SVM can predict more positive cases with high precision as compared to KNN and DTC, as shown in Figure 9. Similarly, when data produced through the SMOTE are fed to the models, both KNN and DTC give reasonable precision and recall with up to and , respectively, as shown in Figure 7. The CNN model with GANs achieves up to , , and in precision, F1-score, and recall, respectively. Similarly, the LSTM model achieves up to , , and in precision, F1-score, and recall, respectively, as shown in Table 8. Using actual data, generated data, and merged data, LSTM and CNN models have been applied successfully. This was most probably true for the case of merged data. These models’ successful generalization on the fused data containing real-world data with artificial data also establishes their anticipations. As it enhances the stability and enlarges the variety of models’ applications, this universality has certain implications for practice in the case of a lack of real data. From the overall assessment of the results, LSTM and CNN models are proven capable of dealing with different types and distributions of data, as shown in Figure 7.

The comparative analysis described in Table 9 shows that using data augmentation significantly improves model performance, especially for datasets with imbalanced classes like AI4I. Classical models such as DTC, KNN, and SVM perform poorly on AI4I without augmentation, showing low precision and F1-scores. When the SMOTE or GANs are applied, their performance improves significantly, highlighting the importance of addressing class imbalance. KNN benefits the most from GAN augmentation, achieving nearly perfect precision, recall, and F1-scores, while the SVM also improves noticeably with both the SMOTE and GANs. Deep learning models like LSTM and CNN already capture complex sequential or spatial patterns, so augmentation provides smaller but still meaningful improvements. For example, GAN-augmented LSTM achieves the highest overall performance across all datasets, showing that GAN-generated samples are realistic and helpful for training. In datasets that are more balanced, such as SECOM and APS, all models perform reasonably well even without augmentation, suggesting that the benefits of SMOTE or GANs are strongest for imbalanced or difficult datasets. Overall, GAN-based augmentation provides consistent and reliable improvements across different models, particularly for those that are sensitive to data distribution like KNN and sequential models like LSTM.

Table 9.

Performance metrics of models on AI4I, SECOM, and APS datasets.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

It is inevitable for industries to take proactive measures to identify equipment faults, as such failures may cause component degradation, equipment breakdown, and potentially result in human casualties, downtime, and high on-site maintenance costs. Therefore, providing industries with an AI-based predictive maintenance system to monitor installed equipment is essential. For this purpose, a generative artificial intelligence system is proposed for the IIoT network. The system consists of two data generation models, SMOTE and GANs, used to generate synthetic data with diversity, which is then applied to machine learning models, including SVM, KNN, and DTC, as well as deep learning models such as CNN and LSTM. Three different data categories, real, GAN-generated, and SMOTE-generated, are applied to the machine learning models to evaluate their performance. GAN-enabled AI models achieve significant performance when intra-dataset comparisons are performed, while deep learning models such as LSTM showed notable improvement when cross-model comparisons are considered. However, the proposed method has some limitations: (1) the synthetic data generation process, while effective, may not fully capture the complexity and variability of real industrial fault patterns; (2) the model is not yet adaptive to evolving fault characteristics in streaming IIoT environments; (3) multi-sensor integration for richer fault context is not implemented; (4) model interpretability for industrial operators remains limited; and (5) the system has not yet been tested under real-world deployment constraints, such as on edge devices. Future research will therefore focus on addressing these limitations by exploring more advanced data generation techniques to improve the diversity and realism of synthetic fault data, developing adaptive learning methods capable of updating in real time from continuous sensor inputs, incorporating data from multiple heterogeneous sensors to provide a more complete diagnostic view, enhancing interpretability to increase user trust, and performing extensive real-world testing particularly on resource-limited edge devices to evaluate practical deployment feasibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.Z. and A.I.; methodology, I.Z. and A.I.; software, I.Z. and M.K.; validation, I.Z., A.I. and M.A.A.; formal analysis, M.K. and N.A.; investigation, I.Z. and N.A.; resources, A.I.; data curation, I.Z. and A.I.; writing—original draft preparation, I.Z. and A.I.; writing—review and editing, A.I., M.A.A. and N.A.; visualization, I.Z. and A.I.; supervision, A.I. and M.K.; project administration, A.I. and M.K.; funding acquisition, N.A., M.A.A. and A.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Prince Sultan University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study can be accessed through the following links: AI4I dataset: https://doi.org/10.24432/C5HS5C; Secom dataset: https://doi.org/10.24432/C54305; Aps dataset: https://doi.org/10.24432/C51S51. All associated code is also available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16900443. The repository includes a README markdown file with detailed code usage and reproducibility instructions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prince Sultan University for paying the Article Processing Charges (APC) of this publication. They would also like to thank Prince Sultan University for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| IIoT | Industrial Internet of Things |

| PdM | Predictive Maintenance |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| RUL | Remaining Useful Life |

References

- Haseeb, K.; Rehman, A.; Saba, T.; Wang, H.; Alruwaili, F.F. Empowering Real-Time Data Optimizing Framework Using Artificial Intelligence of Things for Sustainable Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 39094–39102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.S.H.; Wang, W.; Hieu, N.Q.; Niyato, D.; Friedrichs, T. Predictive Maintenance Model for IIoT-Based Manufacturing: A Transferable Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 15725–15741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wen, R.; Han, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y. Intelligent Fault Identification for Industrial Internet of Things via Prototype-Guided Partial Domain Adaptation with Momentum Weight. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 16381–16391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhao, S. Remaining Useful Life Prediction of IIoT-Enabled Complex Industrial Systems with Hybrid Fusion of Multiple Information Sources. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 9045–9058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compare, M.; Baraldi, P.; Zio, E. Challenges to IoT-Enabled Predictive Maintenance for Industry 4.0. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 7, 4585–4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Yan, B.; Yang, T.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, W. Security-Enhanced Operational Architecture for Decentralized Industrial Internet of Things: A Blockchain-Based Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 11073–11086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeczot, G.; Rojek, I.; Mikołajewski, D.; Sangho, B. AI in IIoT Management of Cybersecurity for Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0 Purposes. Electronics 2023, 12, 3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.A.; Saeed, N.; Masood, M.; Fard, Y.M.; Alouini, M.-S.; Al-Naffouri, T.Y. Deep Learning in the Industrial Internet of Things: Potentials, Challenges, and Emerging Applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 11016–11040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tang, D.; Zhu, H.; Nie, Q. A Novel Predictive Maintenance Method Based on Deep Adversarial Learning in the Intelligent Manufacturing System. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 49557–49575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farman, H.; Shahzad, Y.; Jan, B.; Nasralla, M.M.; Sallam, K.M.; Munasinghe, K.; Jamalipour, A. IoT-Aware Real-Time Healthcare Diagnostic Framework for Diabetes Using Wearable Sensors Through Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 18183–18194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.; Misra, R. Generative Adversarial Networks Based Remaining Useful Life Estimation for IIoT. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2021, 92, 107195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.; Misra, R. A Multi-Model Data-Fusion Based Deep Transfer Learning for Improved Remaining Useful Life Estimation for IIOT Based Systems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 119, 105712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, A.; Breslin, J.G.; Intizar, M.A. Prediction of Machine Failure in Industry 4.0: A Hybrid CNN-LSTM Framework. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Lee, T.-J. Spatiotemporal Medium Access Control for Wireless Powered IoT Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 14822–14834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Lee, T.-J. GWINs: Group-Based Medium Access for Large-Scale Wireless Powered IoT Networks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 172913–172927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, A.; Al-Khazraji, H. A Hybrid of Convolutional Neural Network and Long Short-Term Memory Network Approach to Predictive Maintenance. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2022, 12, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, Y.; Guo, S.; Lei, C.; Liu, D.; Qiu, X. Cloud–Edge Collaborative SFC Mapping for Industrial IoT Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 18, 4158–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, K.; Saba, T.; Rehman, A.; Abbas, N.; Kim, P.W. AI-Driven IoT-Fog Analytics Interactive Smart System with Data Protection. Expert Syst. 2025, 42, e13573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yang, J.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Jiang, W.; Dai, J.; Hu, J. A2C-DRL: Dynamic Scheduling for Stochastic Edge–Cloud Environments Using A2C and Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 16915–16927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babayigit, B.; Abubaker, M. Industrial Internet of Things: A Review of Improvements Over Traditional SCADA Systems for Industrial Automation. IEEE Syst. J. 2024, 18, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Yang, D.; Xiang, Y. Deep-Learning-Enabled Predictive Maintenance in Industrial Internet of Things: Methods, Applications, and Challenges. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 2797–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, X. Scheduling for Minimizing the Age of Information in Multisensor Multiserver Industrial Internet of Things Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikalovic, A.; Suzic, N.; Bajic, B.; Piuri, V. Industry 4.0 Implementation Challenges and Opportunities: A Technological Perspective. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 2797–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arinez, J.F.; Chang, Q.; Gao, R.X.; Xu, C.; Zhang, J. Artificial Intelligence in Advanced Manufacturing: Current Status and Future Outlook. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2020, 142, 110804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ni, J.; Singh, J.; Jiang, B.; Azamfar, M.; Feng, J. Intelligent Maintenance Systems and Predictive Manufacturing. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2020, 142, 110805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]