Abstract

In the highly volatile realm of global security, the necessity for leading-edge and effectual border resilience tactics has never been more imperative. This PRISMA 2020 guided systematic literature review (SLR) examines the intersection of artificial intelligence (AI), open-source intelligence (OSINT), and social media intelligence (SOCMINT) for enhancing border protection. Our systematic investigation across major databases (IEEE Xplore, Scopus, SpringerLink, MDPI, ACM) and grey literature sources yielded 3932 initial records and, after screening and eligibility assessment, 73 studies and reports from acknowledged organizations, contributing to the evidence synthesis. Three research questions (RQ1–RQ3) were addressed concerning the following: (a) the effectiveness and application of AI in OSINT/SOCMINT for border protection, its (b) data, technical, and operational limitations, and its (c) ethical, legal, and societal implications (GELSI). Evidence matrices summarize the findings, while narrative syntheses underline and thematically group the extracted insights. Results indicate that AI techniques—fluctuating from machine learning (ML) and natural language processing (NLP) to computer vision and emerging large language models (LLMs)—produce quantifiable improvements in forecasting irregular migration, detecting human trafficking, and supporting multimodal intelligence fusion. However, limitations include misinformation, data bias, adversarial vulnerabilities, governance deficits, and sandbox-to-production gaps. Ethical and societal concerns highlight risks of surveillance overreach, discrimination, and insufficient oversight, among others. To our knowledge, this is the first SLR at this intersection. We conclude that, AI-assisted OSINT/SOCMINT presents transformative potential for border protection requiring, nonetheless, balanced governance, robust validation, and future research on LLM/agentic AI, human–AI teaming, and oversight mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has evolved from a research concept into a transformational technology with wide-ranging implications for security and defense. Being defined broadly as computational systems capable of performing tasks requiring human-like cognition—including perception, reasoning, and decision-making—AI incorporates subfields like machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), natural language processing (NLP), and computer vision (CV) [1,2]. Contemporary developments include the amalgamation of AI in predictive modeling and multimodal analytics to empower autonomous systems to perform tasks such as surveillance, anomalies’ detection, and intelligence processing at an unprecedented scale [3,4,5].

Concurrently, the conventional perception of border security, which has been historically ingrained in physical barricades and human patrols, is undergoing a profound alteration. This evolution is impelled by the increasing sophistication of transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) and irregular migration networks that leverage advanced digital platforms and communication technologies. The present-day threat environment spreads far beyond physical checkpoints, as malicious networks are stage-managing cross-border operations across continents, exploiting an ever-growing toolset ranging from encrypted messaging/social media platforms [6] to cryptocurrencies [7]. Simultaneously, novel threats unfold within a globalized information ecosystem characterized by an overwhelming deluge of publicly available information (PAI) [8], a fundamental change which necessitates a reconsideration of traditional border security archetypes, moving towards a knowledgeable integration of advanced technology and human expertise.

The concept of open-source intelligence (OSINT)—the systematic collection and analysis of publicly available information—has deep historical roots in military and intelligence contexts. OSINT traditionally referred to monitoring newspapers, radio, and other open communications, expanding gradually its scope to include online news, public records, free-web satellite imagery, and digital platforms [4,9], adjusting to the digital transformation of information ecosystems. Social media intelligence (SOCMINT), a subset of OSINT, has gained prominence due to the exponential growth of platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and Telegram, where migration flows, political unrest, and criminal networks often leave identifiable traces [10,11]. SOCMINT or social media monitoring for security-related tasks, as more periphrastically defined in relevant literature, while providing real-time situational awareness and crowdsourced indicators of emerging security threats, may also raise concerns regarding privacy, ethics, and legality in democratic societies [12].

Border management and protection constitute an area where these innovations converge. Modern border security extends far beyond physical checkpoints, encompassing a multilayered architecture of migration forecasting, risk assessment, critical infrastructure protection, and hybrid threat mitigation [13]. As irregular migration is increasingly influenced by climate change, geopolitical conflicts, an array of interwoven megatrends [14], and its instrumentalization for geopolitical gains from external state actors [15], promising data-driven, evidence-supported solutions emerge to predict and manage cross-border flows [3]. AI-enhanced OSINT and SOCMINT are therefore positioned as strategic tools for early warning, decision support, and operational coordination across national and supranational levels.

The legal and ethical governance of AI-supported intelligence diverges across geographical jurisdictions, with this divergence resonating on the applied operationalization approaches. Within the European Union (EU), the AI Act (2024) [16] and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provide robust regulatory frameworks emphasizing risk classification, proportionality, and data protection. Frontex, the European agency mandated with integrated border management, has commissioned an exploratory study drafted by a prominent think-tank to map adoption pathways for AI technologies in border control, highlighting both opportunities and constraints, Nevertheless, it lacks reference to the potential benefits of AI-assisted OSINT/SOCMINT in border management [5]. Currently, Frontex and the European Union Agency for Aylum (EUAA) use PAI for risk analysis, without engaging in any form of social media monitoring, while previous relevant initiatives were retracted: namely, EUAA’s social media monitoring reports analyzing user posts across platforms, which were permanently banned by the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) in 2019 due to data protection violations, and Frontex’s 2019 tender for social media analysis (including sentiment analysis) which was canceled following regulatory changes [12].

In contrast, U.S. practices underscore a focus on operational deployment and tactical effectiveness, as characteristically illustrated by the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) own AI Use Case Inventory, which details at least 140 active AI systems across its components [17,18]. The inventory reveals a significant investment in AI for border and immigration functions, particularly within Customs and Border Protection (CBP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). Deployed systems include not only facial recognition and cargo scanning technologies but also a suite of OSINT/SOCMINT tools for threat analysis, which use publicly available information from social media and the open web to support investigative and screening missions [19,20]. This extensive, operational-priority approach often precedes the establishment of comprehensive, systemic privacy guarantees, reflecting a different balance between innovation and regulation compared to the EU model [10]. Despite not directly linked to border protection, two paradigms are deemed as valuable to be mentioned, at this point, to further enrich the context of AI-supported intelligence in the broader security milieu. NATO has also underscored the dual-use nature of AI, calling for balance between innovation, interoperability, and ethical safeguards in defense contexts [21]. China’s military intelligence apparatus, is reported to employ LLM and agent-based schemes to perform OSINT related tasks and support all the functions of the intelligence cycle, including collection and analysis [22].

Although AI, OSINT/SOCMINT, and border protection are either individually or in tandem, extensively discussed in the literature, the intersection of these three domains has not yet been addressed collectively. Existing research is mainly characterized by an increased degree of compartmentalization: technical studies focus on algorithmic accuracy (e.g., drone-based tunnel detection using YOLOv8 models), while policy papers emphasize ethical oversight or legal frameworks [13]. Systematic syntheses that bridge technical innovation with policy and operational practice in border management are scarce from current bibliography.

Consequently, the present SLR pursues the following: (a) systematically map the academic and institutional literature at the under-explored intersection of AI, OSINT/SOCMINT, and border protection, (b) identify thematic clusters of research, including primarily technical innovations and operational practices, and secondarily legal frameworks and ethical concerns that affect the operationalization of AI-assisted exploitation of free web/social media-derived data, and (c) contribute an open Supplementary Dataset (https://osf.io/kr5as/overview, accessed on 15 November 2025) of compiled annotated metadata from the included studies to the research community, under CC-BY-4.0, serving as a foundational pathfinder for future investigations at the AI-assisted OSINT/SOCMINT-border protection intersection.

2. Methodology

In performing this SLR, we have employed a methodology guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [23] (see Supplementary Materials) to achieve the foundational level of academic rigor and transparency in our search and selection practices. The present SLR, including the followed protocol, were retrospectively documented on 17 October 2025, in the Open Science Framework (OSF) registry (available online on https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/Z3WG6, accessed on 15 November 2025). While registration was not initially planned, and motivated by the fact that the present SLR is the first one that systematically studies the exact intersection of AI, OSINT/SOCMINT, and border security, we opted to proceed with ex post facto registration. According to PRISMA 2020 guideline’s interpretation [23], such a registration can still contribute to transparency and reproducibility, thus serving as a guiding tool for future researchers aiming to replicate or build upon this review. Grammarly’s generative AI assistance was employed for language editing purposes, to enhance the clarity and fluency of the manuscript. This assistance was solely utilized for linguistic refinement purposes, without impacting the original data collection, processing, interpretation, and presentation, as well as the overall intellectual contributions presented in this systematic review.

2.1. Defining the Research Questions (RQs)

The research questions (RQs) guiding this SLR were refined iteratively through scoping reviews and thematic exploration of existing literature at the intersection of our core thematic components (AI, OSINT/SOCMINT and border security). The final RQs are as follows:

- •

- RQ1 (Effectiveness and Application of AI): How are specific AI technologies (e.g., natural language processing, computer vision, machine learning, generative AI, agentic AI) being applied to leverage open-source and social media data toward enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of border protection, and what tangible improvements and operational gains have been observed or are theoretically possible compared to traditional methods and other areas of the wider security domain?

- •

- RQ2 (Limitations): What are the principal technical, operational, and data quality limitations (including issues of misinformation, data veracity, bias, and scalability) encountered in deploying AI with open-source and social media data for border protection, and how do these limitations impact the reliability and practical utility of AI-driven insights?

- •

- RQ3 (Ethical, Legal, and Societal Implications): What are the critical ethical, privacy, and legal implications (e.g., surveillance overreach, human rights infringements, data sovereignty, lack of transparency, and potential for discrimination) associated with the use of AI in analyzing open-source and social media for border protection, and how do different stakeholders perceive and address these concerns?

2.2. Developing the Search Strategy

In this step, specific criteria and tools were established to systematically identify relevant publications across academic databases and conventional search engines. The search strategy for this SLR was purposefully designed to capture a wide array of literature, reflecting both academic and practical perspectives, in order to pursue academic rigor and ensure relevance to practitioners. We conducted an initial search cycle across various academic databases and conventional search engines, as detailed below, until 15 July 2025, to collect a set of pertinent literature. A repetitive search cycle was performed on 15 September 2025, to identify newly emerged literature and verify the completeness of the initial search. The search strategy was implemented as follows:

- •

- Search Academic Databases: Utilize selected keywords to search academic databases such as IEEE, Scopus, ACM, Springer Link, MDPI and an academic search engine (Google Scholar). Search Strings/Boolean queries were adapted for each database:

- IEEE Xplore/SpringerLink/MDPI:(“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “generative AI” OR “large language model” OR “agentic system”) AND (“open-source intelligence” OR OSINT OR SOCMINT OR “social media intelligence” OR “social media” OR “dark web”) AND (“border protection” OR “border security” OR “irregular migration” OR “smuggling” OR “trafficking” OR “terrorism” OR “cybercrime” OR “customs” OR “illegal migration”)

- 2.

- Scopus:TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “generative AI” OR “large language model” OR “agentic AI”)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“open-source intelligence” OR OSINT OR SOCMINT OR “social media intelligence” OR “social media” OR “dark web”)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“border protection” OR “border security” OR “irregular migration” OR “smuggling” OR “trafficking” OR “terrorism” OR “cybercrime” OR “customs” OR “illegal migration”)) AND PUBYEAR > 2019 AND PUBYEAR < 2026

- 3.

- ACM Digital Library:[[All: “artificial intelligence”] OR [All: “machine learning”] OR [All: “deep learning”] OR [All: “generative AI”] OR [All: “large language model”] OR [All: “agentic system”]] AND [[All: “open-source intelligence” OR OSINT OR SOCMINT OR “social media intelligence” OR “social media” OR “dark web”]] AND [[All: “border protection” OR “border security” OR “irregular migration” OR “smuggling” OR “trafficking” OR “terrorism” OR “cybercrime” OR “customs” OR “illegal migration”]] AND (publication date: [2019 TO 2025])

- 4.

- Google Scholar (through the “Publish or Perish” automated extraction software):(“Artificial Intelligence” OR AI OR “Machine Learning” OR “Deep Learning” OR “Natural Language Processing” OR “Computer Vision” OR “Generative AI” OR “Large Language Models” OR LLM OR “Agentic AI”) AND (“Open Source Intelligence” OR OSINT OR “Publicly available information” OR “internet” OR “web search” OR “Social Media Intelligence” OR “Social Media”) AND (“Border management” OR “Border Protection” OR “Border Security”).

- •

- Conventional Search engines: Selected keywords were utilized to research conventional search engines such as Google, Bing, and Yandex, to identify relevant material from organizations and agencies (governmental or intergovernmental) involved in border security, like the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) and the US CBP/ICE.

2.3. Identifying and Screening Papers

This subsection delineates the sequential identification and screening workflow that operationalized the PRISMA 2020 process across all sources, by utilizing Zotero 7.0.27 (64-bit). First, records retrieved from IEEE Xplore, Scopus, SpringerLink, MDPI, ACM Digital Library, Google Scholar, and grey sources were imported into a unified Zotero library, preserving source tags and dates of retrieval. Zotero Duplicate Items feature was then used to identify and merge exact and near-duplicate records prior to screening; removal counts are reflected at the Identification stage of the PRISMA flow. The deduplicated library was exported to spreadsheets for title/abstract screening against the inclusion–exclusion criteria, followed by full-text screening of eligible items.

- •

- Initial Evaluation: Screen the title, keywords, and abstract of identified articles to exclude non-relevant studies.

- •

- Apply eligibility criteria

- 1.

- Inclusion Criteria:

- ∘

- Study designs: Empirical studies, case studies, technical reports, government documents, and white papers.

- ∘

- Time period: Emphasis on the last 2019–2025 period, with the exception of landmark studies from authoritative sources outside this period, that may serve as a comparison point, to comprehend the advancements in the given subject.

- ∘

- Geographic scope: Global, with emphasis on high-implementation regions (e.g., EU external borders, US borders, Southeast Asia, etc.)

- ∘

- Language: English and other major languages with translation.

- ∘

- AI applications: AI technologies and AI-based methodologies that process internet-found, publicly available, and social media data in contexts relevant to border protection, where outputs can be operationalized by border agencies as actionable OSINT/SOCMINT. Include studies even if they do not use the terms “OSINT” or “SOCMINT” explicitly, provided they describe open-source or social media data collection, analysis, fusion, or decision-support techniques applicable to border security tasks (e.g., detection, monitoring, forecasting, attribution, or resource allocation). Include AI-driven methodologies that a) augment cyber threat intelligence, crucial for the digital infrastructure security of border enforcement agencies [17,18], and b) support broader security and intelligence tasks, as the concept of “intelligence led’ or “intelligence-informed” border protection is closely interwoven with the organizational fabric of relevant agencies [17]. Emphasize methods with clear pipelines and potential for operational deployment, evaluation metrics, or integration with agency workflows.

- 2.

- Exclusion Criteria:

- ∘

- Opinion pieces without supportive data

- ∘

- Studies focusing solely on technical specifications without implementation data

- ∘

- Studies outside the focus chronological period (2019–2025), without any AI-assisted technological automation, and not bearing the characteristics of a landmark study.

2.4. Selection Process

A total of 3932 initial records were retrieved across all sources. After de-duplication, 2467 unique items remained. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts, following this with full-text eligibility checks, without the use of automation tools. Disagreements were resolved by dialogic evaluation and consensus. The complete selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram in Figure 1, while Figure 2 presents the eligibility outcomes for studies identified via other methods, to explicitly highlight the subset of records excluded due to irrelevance of the AI-supported OSINT/SOCMINT-border protection nexus.

Figure 1.

PRISMAflow chart.

Figure 2.

Eligibility outcomes for studies identified via other methods.

2.5. Data Collection Process

Data extraction was performed systematically using a standardized template in Zotero, ensuring comprehensive and consistent capture of relevant information from the 73 included studies. The full extracted data is compiled and available as open Supplementary Material under the CC-BY-4.0 license at the OSF project repository. This dataset enables verification of the synthesis, meta-analyses, and extensions by other researchers, with an accompanying README.md for guidance.

For each study, we recorded the following fields, which form the basis of the open Supplementary Dataset to support reproducibility and further analyses:

- •

- Bibliographic details (Key [Zotero ID], authors, publication year, title, publication title [journal/venue], DOI/URL [95%+ coverage], abstract note, pages, volume, issue, ISSN/ISBN, language [primarily English], item type [e.g., journal article, conference paper]).

- •

- Study design (empirical, case study, experimental, systematic review, white paper, policy report; additional provenance like access date, date added/modified, library catalog).

- •

- AI technique applied (e.g., NLP, ML, CV, LLMs, generative AI, agentic AI; tagged via Manual Tags and Automatic Tags for categorization).

- •

- Application context (border protection, trafficking, migration prediction, cybercrime; including Extra field notes on geographic/operational scope, e.g., Eastern Europe borders).

- •

- Validation status (real-world-tested, simulation, theoretical; with transferability assessment [whether findings can be generalized to border contexts]).

- •

- Metrics reported (precision, recall, accuracy, F1 score, etc.; extracted quantitatively where available, e.g., +86% improvement over baselines).

- •

- Narrative summaries in Notes field, mapping RQs coverage.

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

In the present SLR, we opted not to apply an established risk of bias assessment tool (e.g., QUADAS-2 or ROBIS) due to the significant heterogeneity observed among sources comprising our corpus. Selected studies, expand from empirical studies to case studies, technical reports, white papers, and policy documents, employing diverse methodologies from experimental ML to conceptual frameworks. The exhibited methodological multiplicity—while essential for encapsulating the multifactorial intersection of AI, OSINT/SOCMINT, and border security—impedes uniform application of standardized bias assessment instruments that are designed for homogeneous study designs. Instead, we employed narrative quality assessments throughout data extraction, logging validation status, metrics reporting, and transferability limitations for each included study (detailed in evidence matrices, Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3). We acknowledge this represents a limitation, particularly for assessing certainty of evidence across heterogeneous source types, and address this through cautious certainty assessments elaborated in Section 4.

Table 1.

Evidence Matrix of RQ1: Effectiveness and Applications of AI.

Table 2.

Evidence Matrix of RQ2: Limitations.

Table 3.

Evidence Matrix of RQ3: Ethical, Legal, Social Issues.

2.7. Data Synthesis

Given the heterogeneous nature of the 73 included studies-spanning diverse AI modalities (e.g., ML, NLP, LLMs) and border contexts (e.g., trafficking vs. migration)—a quantitative meta-analysis was deemed impracticable, aligning with PRISMA 2020 guidelines for narrative synthesis in such cases. This section particularizes the qualitative approach, which organizes evidence thematically per RQ (RQ1: applications; RQ2: limitations; RQ3: GELSI) while incorporating quantitative descriptors (e.g., accuracy metrics) for rigor. The process involved iterative coding of extracted data into matrices (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3), cross-referencing for patterns, and validation against the protocol to ensure comprehensive coverage without overgeneralization, ultimately bridging methodological gaps to inform practical and research implications.

- •

- Effect Measures: Due to the heterogeneity of study designs and metrics, quantitative meta-analysis was reckoned as not feasible. Instead, qualitative synthesis and evidence tabulation were employed.

- •

- Synthesis Methods: Evidence matrices were developed for each RQ.

- •

- Sensitivity Analyses: Not applicable due to design heterogeneity.

- •

- Reporting Bias Assessment: Formal statistical assessment was not possible due to inclusion of grey literature; this is noted as a limitation.

- •

- Certainty of Evidence: As evidence spans academic, corporate, and policy sources, certainty assessments were cautious and are elaborated in the discussion.

3. Results

The 73 included studies and reports indicate a geographical concentration in North America and Europe, with a focus on the U.S.–Mexico border and EU external borders. The dominant AI technologies are classical ML and NLP, though recent studies increasingly explore DL, CV, and LLMs. In the following subsections, data extracted from our corpus are presented per each RQ. To visualize the distribution of clustered thematic areas in the included literature, we generated a word cloud from titles, abstracts, keywords (or index terms), where applicable, in our evidence base. This highlights the prominence of terms such as “artificial intelligence”, “migration”, “information”, “security”, “border”, “migration”, “OSINT”, “security”, “analysis”, etc. (Figure 3). Following, Figure 4 further illustrates the temporal progression of the included studies, exhibiting a marked acceleration in research activity from 3 publications in 2019 to 29 in 2024, underscoring the field’s prompt maturation amid advancing AI capabilities.

Figure 3.

Word cloud generated from the corpus.

Figure 4.

Temporal distribution of the studies.

3.1. RQ1—AI Effectiveness and Application of AI in OSINT/SOCMINT for Border Protection and Adjacent Functions

The first research question (RQ1) examined how AI technologies are applied to OSINT and SOCMINT in the context of border management and protection. The evidence matrix compiled from our bibliographic corpus provides a structured overview of empirical applications, experimental validations, and systematic reviews spanning border security and migration monitoring/forecasting, counter-trafficking and smuggling, linking and analyzing trafficking networks, cyber threat intelligence and broader intelligence, and security applications, as presented in Table 1.

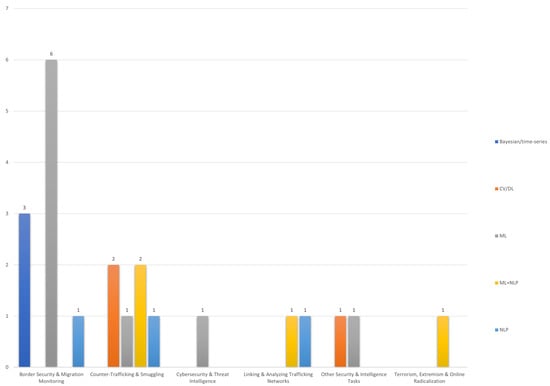

The research compiled in Table 1 comprises a total of 43 entries, across seven application categories, providing a detailed snapshot of AI adoption in OSINT/SOCMINT for border protection and associated tasks. The distribution of these entries per operational area indicate that “Border Security and Migration Monitoring” is the leading category with 12 entries, followed by “Other Security and Intelligence Tasks’ with 8 entries and the remaining categories, in descending order, being: “Counter-Trafficking and Smuggling” (7), “Systematic and Conceptual Reviews” (6), “Terrorism/Extremism” (4), and both “Cybersecurity and Threat Intelligence” and “Linking and Analyzing Trafficking Networks” with 3 entries each. In terms of technical approach, the full breakdown of prevalence across the evidence matrix indicates that classical ML and NLP dominate the landscape, accounting for the vast majority of studies with 19 and 17 entries, respectively. The following AI-supported approaches include DL (8), CV (7), LLMs/Agents (6), Bayesian/Statistical/Time series (3), and, lastly, KGs (2). These counts reflect mentions in individual or combined usages, as aggregated in the pivot table underlying Figure 5 and Figure 6. The most frequently utilized data sources reflect this focus on textual and official data, with Twitter/X (10), Official statistics (7) (from sources like UNHCR, World Bank, etc.), and News/NewsAPI/Google News (7) leading the way. Other common sources include Facebook/Instagram (6), the Dark/Deep Web (4), and Satellite/Imagery (4). Geographically, the studies are concentrated, with EU/Europe (13) and the U.S./USA (8) being the most prominent tags. Recurring regional focuses include Ukraine (5) and South Africa/China (2 each), alongside a broad set of general or global contexts (14).

Figure 5.

Distribution of AI technique families across application categories (top three values-systematic and conceptual reviews excluded).

Figure 6.

Medium/High-performing AI technique families by application category (studies reporting high-medium quantitative results only.

To summarize visually the above, a PivotTable (Figure 5) cross-tabulates the empirical studies of Table 1 (excluding systematic and conceptual reviews) by application category and AI technique family. The top three values emerging after the cross tabulation and as highlighted in Figure 5 include ML (9), ML + NLP (4), and NLP, CV/DL, and Bayesian each with three counts. While many entries mixed AI-assisted technics within a single study (e.g., ML plus NLP or CV/DL components), the distribution clearly indicates that the majority of “Border Security and Migration Monitoring” and “Other Security and Intelligence Tasks” is largely driven by pipelines built around classical ML and NLP, while CV/DL, Bayesian/time-series models, and LLM/agentic systems appear in more focused areas such as imagery-based surveillance, counter-trafficking/smuggling, cyber threat intelligence, and radicalization/unrest monitoring.

Following, Figure 6 refines the previous illustration, by applying a performance filter to the same set of non-review studies, utterly retaining only those that report at least medium-to-high quantitative results. In this context, “medium-to-high” denotes cases where studies provide clear numerical evaluation (e.g., error reductions, F1, accuracy, AP, or mAP) at reasonably good levels, with the ‘high’ subset typically achieving very strong values (around 0.9 or above or large gains over baselines). Even though many of the underlying systems combine multiple AI families within a single pipeline, the filtered PivotTable shows that migration-related forecasting and trafficking-linked applications remain the main clusters of stronger evidence, with ML, Bayesian/time-series, CV/DL, and LLM-based approaches most frequently associated with these higher performing deployments, while other security and intelligence areas continue to feature relatively fewer rigorously evaluated models.

The literature demonstrates an observable progression, from conceptual frameworks to operational prototypes and validated applications. In the area of border security and migration monitoring, time-series and ML models have shown significant predictive accuracy for irregular border crossings and asylum applications. Indicatively, authors of [24] applied Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART) to macro-level datasets, reporting an 86% root mean squared error (RMSE) reduction compared to Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (SARIMA) baselines in forecasting irregular immigration across the U.S.–Mexico border. In a similar manner, authors of [31] employed convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to geotag refugee-related tweets along Balkan routes, achieving strong performance (AP = 0.871) and demonstrating the operational value of SOCMINT for early warning of displacement events.

CV and UAV-based applications, in combination with publicly/online available datasets, are also expanding the operational toolkit. Authors of [3] achieved >95% accuracy in identifying ground pits from drone imagery, underscoring the applicability of vision-based AI to physical security contexts. Although validation is still limited, these studies indicate strong transferability to operational deployments.

For counter-trafficking and smuggling, AI-assisted systems leveraging OSINT and SOCMINT datasets are proving highly effective. Kodandaram et al. [11] demonstrated that human-smuggling advertisements on social media like TikTok and Facebook, often disguised as innocent travel or tourism-related adverts in regional languages, can be reliably detected with F1 scores surpassing 0.9, directly supporting border enforcement. Authors of [36] designed an automated OSINT pipeline for NGOs, showing measurable improvements in identifying trafficking suspects and victims across global contexts, highlighting the scalability of AI-enhanced SOCMINT, especially in cases where traditional policing lacks real-time visibility.

Within cybersecurity and predictive threat intelligence, AI enhances OSINT-based detection of adversarial activity. In [41], authors tested LLM-based chatbots for cybersecurity OSINT, achieving strong classification performance but weaker results in named entity recognition. Research conducted in [40] showed that OSINT-integrated AI models could reach 95% accuracy in predictive cyber threat modeling, a finding that underscores AI’s transferability beyond traditional border domains.

While the literature demonstrates measurable improvements across multiple domains, the transition from experimental validation to operational deployment remains uneven. Studies reporting operational deployments (e.g., DHS’s 105 active AI use cases, 140+ according to our analysis of [20]) often lack detailed performance metrics, while high-performing experimental systems (e.g., F1 scores > 0.9 for smuggling detection) have not demonstrated scalability to production environments. This deployment gap represents a critical limitation for agencies seeking to operationalize AI-enhanced OSINT/SOCMINT capabilities. Future research must address the sandbox-to-production transition, including infrastructure requirements, real-time processing constraints, and integration with existing border management workflows.

Above key takeaways considered collectively, RQ1 reveals that AI-assisted methodologies for processing and analyzing open-source/social media-derived data for border protection and adjacent tasks oscillate across multiple modalities (text, vision, audio, multimodal agents). The strongest quantitative improvements are reported in forecasting migration flows and detecting trafficking-related content, whereas conceptual and systematic reviews stress legal and operational integration. The evidence suggests a gradual, yet intangible shift from ad hoc research to scalable, transferable solutions that could transform border intelligence architectures.

3.2. RQ2—Limitations

Our bibliographic collection indicates that deploying AI with open-source and social media data for border protection faces significant limitations across data quality, technical, and operational domains. These challenges collectively impact the reliability and practical utility of AI-supported insights, often leading to biased, flawed, or impractical outcomes that risk undermining both security objectives and human rights, as it becomes apparent by the evidence matrix represented in Table 2.

Analyzing the data presented in Table 2, we observe that data quality stands as the most predominant of failure modes: Non-representative sampling (route/language/platform bias) and misinformation contaminate inputs; concept drift and weak ground truth impede validation. The main results deriving from this limitation are unstable forecasts and fragile detections across time/routes [25,26,31,76]. Gender biases intensify data quality challenges, especially in facial recognition and migration/trafficking detection. Intersectional disparities have been observed to misclassify darker-skinned women up to 34.7% vs. 0.8% for lighter-skinned men, skewing training data toward cisgender norms and causing false positives in profiling migrant women/LGBTQIA+ [69]. Automatic gender recognition fails trans/non-binary users (20–30% errors) via binary models ignoring expression [71]. Bias in audiovisual data amplifies this challenge, perpetuating stereotypes like associating women’s voices with lower threats [70].

Another observation is that engineering strain is structural: Real-time, multilingual, multimodal OSINT overwhelms ingestion, annotation, and model-serving; bottlenecks amplify latency and reduce coverage [31,49,73].

In addition, opacity and governance gaps undermine uptake. Limited explainability and unclear accountability chains conflict with DPIA/rights requirements in EU border contexts, constraining operationalization and public legitimacy [65,68,72,75].

Regarding the operational consequences, when these limits coincide, agencies face misallocation of patrol/screening (bias), alert fatigue (noise), non-portable models (drift), and contestation risk (opacity/legal gaps), eroding the reliability of AI outputs and their practical utility for timely, defensible decisions.

Notably, certain implications for deployment arise. Effective use requires (a) bias/coverage audits and robust baselines; (b) source verification and bot/rumor defenses; (c) drift/label pipelines with multilingual QA; (d) interpretable models or explanation layers; and (e) governance baked into contracts and MLOps (logs, DPIAs, redress). Absent in these, the literature converges that the AI-assisted exploitation of internet/social media data for border protection remains decision-fragile and hard to lawfully scale in live operations.

Another notable point is the performance–safety tradeoffs in testing environments. Sandboxed deployment of AI systems for OSINT/SOCMINT analysis introduces substantial computational overhead and operational constraints. Research indicates a negative correlation (r = 0.31) between tool use efficiency and safety risks in controlled environments, suggesting that safety measures can impede operational effectiveness. This creates a critical gap between testing and production environments, as single-turn interaction evaluations present biased pictures of safety risks compared to multi-turn interactions that more accurately reflect real-world complexity.

As a final observation for this RQ, it should be noted that an evaluation-to-deployment gap is created, as the emulation of tool execution using LLMs in sandbox environments may not accurately execute tool-calling actions, potentially leading to false positives or negatives in risk assessment. Heavy containment measures impose prohibitive costs that could cause agencies to fall behind in competitive scenarios, while legacy operational technology environments remain highly susceptible to disruption during security testing [80,81].

3.3. RQ3—Ethical, Legal, Societal Issues

Subsequent Table 3, group studies from our bibliography that examine the ethical, privacy, legal, and societal implications of applying AI to open-source/social-media data in border contexts. Entries are organized by category and specific risk, and each cell distills how the concern affects rights and society.

Table 3 indicates a three-pillar risk profile, in which privacy and surveillance concerns dominate. Large-scale OSINT collection and AI-assisted inference can exceed necessity/proportionality tests, expose vulnerable populations, and chill lawful speech or movement; several studies tie these effects to weak purpose limitation, long retention, and cross-context reuse. Second, accountability and transparency issues recur: Complex, often opaque models undermine explainability and reason-giving in high-stakes border decisions; overlapping EU/US legal regimes and interoperable systems create fragmented accountability and unclear redress paths. Third, bias and fairness risks emerge from non-representative social data (language, connectivity, platform effects), which can skew risk scores and operational prioritization—amplifying discrimination and digital exclusion. Gender biases heighten risks to women/LGBTQIA+ migrants in border applications, as per recent studies. Predictive analytics for trafficking/migration exhibit 20–40× misclassification for darker-skinned women, erring risk assessments and increasing exploitation/deportation vulnerability [69]. AGR in surveillance misgenders trans/non-binary individuals, endangering asylum via outing/denied protection [71]. Biases in audiovisual data overlook gendered smuggling dynamics, violating privacy/non-discrimination rights and distorting aid [70]. Impacts include safety threats and unequal rights enforcement. Mitigation demands diverse data validation and DPIAs with trans input, and misclassification redress appeals for proportionality.

Stakeholder views diverge predictably: operational agencies emphasize efficiency and situational awareness; regulators/DPAs and courts press for DPIAs, lawful bases, and auditable processes; civil society and affected communities highlight profiling, opacity, and limited contestability. Convergence appears around remedies: integrate DPIAs as design inputs, enforce purpose limitation and data minimization, require meaningful human review and reasons-giving, maintain immutable logs and model/data lineage for audit, implement fairness/accuracy monitoring (with multilingual/representation checks), adopt strict retention and access controls, and provide clear redress channels. Overall, the evidence indicates that AI-enabled OSINT for border protection is only societally and legally sustainable when these safeguards are embedded into engineering, procurement, and day-to-day operations—not appended after deployment.

4. Discussion

This systematic review explored what are the current and potential applications of AI technologies in conjunction with open-source/social media-derived data, to empower border protection, identifying not only their effectiveness but also their limitations and ethical, legal, and societal implications. The synthesis of evidence across the three research questions (RQ1–RQ3) reveals a complex landscape characterized by rapid technological advances, persistent operational and governance challenges, and ongoing debates regarding the balance between security and human rights. In the present section, our discussion will orbit around the cross-thematic discourses of our RQs, the gaps identified in the current literature and will conclude with suggestions for future research directions, including a creative synthesis part, in which we envision the prospective Human-Agent Teaming for border protection.

4.1. Cross-Thematic Discussion on RQ1 to RQ3

Regarding RQ1, AI applications for border protection exhibit a growing diversity. Techniques range from CV for geolocation and anomaly detection [58], to ML–based migration forecasting [31,33], agentic multimodal OSINT systems [52], and LLM-driven SOCMINT analytics [41,53]. These methods yield clear benefits. They offer tangible improvements, such as enhanced precision in detecting smuggling ads or refugee flows. They also provide qualitative gains, like reducing analysts’ cognitive load. Yet, challenges persist in validation and transferability. Several studies provide empirical evaluations in security-adjacent fields [44], but relatively few report direct operational deployments at borders. Forecasting and SOCMINT applications have shown promise in humanitarian or crisis contexts [7,14], suggesting transfer potential, but real-world border security adoption remains limited.

With respect to RQ2, evidence highlights four major clusters of limitations:

- •

- Data quality and veracity: Misinformation, data inadequacy, and adversarial manipulation (e.g., smuggling networks adapting their digital signals) were consistent concerns [57].

- •

- Bias and representativeness: Models often reproduce systemic biases, disproportionately affecting marginalized groups [16,61].

- •

- Operational scalability: Deploying AI at border scale requires infrastructure and real-time processing capacities that are not always available.

- •

- Integration challenges: Interfacing AI with existing border management systems and legal protocols still pose an impediment.

These limitations undermine both reliability and usability. A repeating debate concerns whether AI should augment human judgment (hybrid models) or move toward greater autonomy. Current evidence favors human–AI teaming approaches as a safeguard against over-reliance on algorithmic decision-making.

Findings from RQ3 converge on three central areas of concern:

- •

- Privacy and surveillance: The extensive use of OSINT and SOCMINT risks infringing upon fundamental rights, including freedom of expression and association [68,86].

- •

- Fairness and accountability: Black-box AI systems exacerbate opacity in risk profiling, challenging due process and non-discrimination norms [72,94].

- •

- Governance deficits: Regulatory frameworks lag behind technological innovation, creating governance gaps in areas such as cross-border data flows, transparency, and redress mechanisms [65,95].

A key tension lies between efficiency gains and human rights safeguards. While LLMs and agentic AI promise breakthroughs in multimodal fusion and real-time monitoring [41,52], they also raise novel risks, including hallucinations, data poisoning, and surveillance overreach.

The three RQs reveal deeply interconnected challenges. Findings show deep links across effectiveness, limitations, and implications. Technical limitations in RQ2 heighten ethical risks from RQ3. Data quality issues, bias and scalability constraints, directly worsen concerns like fairness and privacy. Examples highlight these overlaps. Over-representation of digitally connected groups in training data causes technical unreliability. It also raises ethical issues, exposing underrepresented populations to surveillance and poor threat modeling. The black box problem bridges RQs 2 and 3. It complicates troubleshooting (RQ2) and accountability (RQ3). Solutions require holistic design. Explainability demands integrated approaches across technical, operational, and governance areas—not isolated fixes. Table 4 visualizes these interconnections, by mapping challenges’ impacts on operations.

Table 4.

Synthesis of Cross-Cutting Challenges.

4.2. Gaps in the Current Literature

Despite the maturing body of research on AI-powered utilization of open-source/social media data for border management associated tasks, several significant gaps persist, revealing research grounds that are prolific for further academic inquiry and practical development.

4.2.1. Inadequate Empirical Data on Long-Term Effectiveness and Societal Impact

Much of the current literature focuses on the theoretical potential and initial implementation benefits of AI technologies leveraging open-source/social media originated data towards improving tasks within the scope of border security agencies’ missions, such as increased efficiency, speed, and accuracy in threat detection. However, there is a notable lack of wide-ranging empirical studies that provide long-term data on the actual effectiveness of these integrated systems in real-world operational environments. Hence, in-depth, longitudinal studies are considered necessary to quantitatively assess the sustained impact on reducing illegal crossings, dismantling criminal networks, and improving overall border security metrics, a gap which is particularly noticeable for the nascent applications of LLMs and agents; while initial experiments show promising accuracy improvements [42], long-term performance, adaptability to evolving threats, and real-world operational reliability remain largely unexamined. In this direction, an interesting perspective for border protection agencies would encompass the research and development of integrated platforms that harness LLMs for end-to-end migration flow assessment and border incident analysis, employing combined multiple specialized capabilities such as the following: (a) continuous monitoring of diverse SOCMINT and OSINT sources—including social media platforms, online communications, citizen-generated content, and grey data—for indicators of irregular migration and facilitation networks; (b) automated pattern recognition across multilingual datasets to identify emerging smuggling routes, shifts in migration corridors, and coordination among transnational criminal organizations; (c) early warning mechanisms that provide strategic foresight to operational contingents and decision-makers regarding evolving changes in migratory pressures; and (d) knowledge graph construction that fuses heterogeneous information streams into actionable intelligence products. The development of proof-of-concept prototypes validated against curated SOCMINT datasets would address the empirical gap identified in RQ2, demonstrating how LLM-supported approaches can move from theoretical promise to operational utility.

4.2.2. Lack of Comprehensive Legal and Ethical Frameworks for Rapidly Evolving Technologies

The rapid pace of technological advancement in AI and intelligence gathering has outstripped the development of adequate legal and ethical frameworks. While some regulations, like the EU AI Act, classify border control AI as “high-risk”, there is a broader absence of globally harmonized standards for data collection, processing, and sharing, particularly concerning sensitive information derived from OSINT/SOCMINT. The definitional debates surrounding OSINT, especially regarding the legality of “grey data”, highlight a critical need for clearer legal guidelines. This challenge is further aggravated by LLMs and agents, which can process and infer from extensive, unstructured datasets, raising new questions about data provenance, consent, and the boundaries of “publicly available” information. Thus, thorough frameworks, continuously adapting to engulf the rapid developments of AI, are needed to address issues of algorithmic bias, accountability for AI-supported decisions, and the protection of individual rights against potential misuse or of these technologies.

4.2.3. Challenges in Data Integration and Interoperability Across Diverse Systems

Effective AI-supported OSINT/SOCMINT for border management relies on the seamless integration and interoperability of diverse data sources and technological systems, with literature, however, indicating significant challenges in this area. Data is often sparse and complex, and criminal networks are dynamic and secretive, making it difficult to gather useful information [96]. While some systems aim to correlate sensor data into an integrated operational picture, the broader challenge of integrating disparate datasets from various government agencies, international partners, and open-source platforms remains significant. The US CBP agency emphasizes interoperability as central to information-sharing among federal agencies, but the technical and bureaucratic hurdles to achieving this are not fully explored in the provided material. Research gaps exist in the incorporation of pre-existing OSINT tools with AI and the underutilization of alternate data sources, suggesting that comprehensive data ecosystems are yet to be fully realized or studied. The integration of multimodal LLMs and agents, which can process diverse data types (text, audio, video, images), presents both an opportunity and a challenge for creating truly integrated intelligence platforms.

4.2.4. Under-Explored Applications and Methodologies

While the literature covers various applications of AI and OSINT/SOCMINT, certain areas and methodological approaches remain under-explored. For instance, the specific application of advanced ML techniques, beyond general object detection or facial recognition, to nuanced OSINT challenges is not always detailed. There is a call for more research into the creation of AI-based OSINT models that apply to specific intelligence requirements beyond general threat detection, such as penetration testing or highly specialized criminal typologies. The potential of merging ML with broader AI and cognitive skills for even more efficient processing of immense volumes of information is recognized but requires further investigation. Furthermore, while the general benefits of AI in streamlining immigration processes are noted, specific case studies or detailed methodological analyses of AI’s role in complex immigration decision-making, beyond basic application triaging, are less prevalent.

Additionally, the full scope of how LLMs and agents can be creatively applied to OSINT/SOCMINT for border protection is still largely theoretical. A particularly promising angle could potentially involve the development of integrated platforms that employ LLMs for end-to-end migration flow assessment and border incident analysis. However, caution should be exercised with regard to hallucinations, which is highlighted as the prevalent disadvantage of LLMs. Continuously enriched bibliography indicate that the methodology of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), which integrates external knowledge retrieval with generative models, may remedy LLM hallucinations and enhance output verifiability. This feature is of paramount importance for intelligence tasks where misinformation can lead to misallocated resources, flawed threat assessments, or even more catastrophic results. In OSINT contexts, RAG frameworks like the FABULA system [97] (selected for exemplificatory purposes), ground LLM responses in real-time retrieval from verifiable sources (e.g., social media archives, news feeds, or satellite imagery). Initial pilots in cybersecurity show RAG achieving 25.7% higher detection accuracy over un-augmented models [98], suggesting potential for border applications like fusing SOCMINT signals with official migration data. However, evaluations in operational border environments are lacking, paving the way for future research on RAG-integrated systems to enhance RQ2 reliability while enabling scalable, evidence-based forecasting

Such approaches are reported to achieve up to 25.7% higher detection accuracy and 31% faster triage times, when compared to standard LLMs in their default configuration. For border protection, federated RAG variants could enable privacy-preserving analysis across agencies, fusing multilingual SOCMINT signals without centralizing sensitive data. Despite these benefits, empirical studies on RAG’s deployment in operational border environments remain scarce, representing a methodological gap, highly suitable for investigation to bridge RQ2 limitations in data veracity and scalability. LangChain, an open-source framework designed for building LLM applications, integrates seamlessly into the above scheme, and can be characterized as a force multiplier. LangChain provides modular components like document loaders, text splitters, embedding models (e.g., OpenAI), vector stores (e.g., FAISS or Pinecone), retrievers, and chains to orchestrate retrieval and generation. This enables efficient pipelines where external data retrieval grounds LLM outputs, reducing hallucinations. Official LangChain documentation and tutorials demonstrate end-to-end RAG setups, including agentic workflows via LangGraph for dynamic querying [99].

Empirical research on practical integration, efficacy, and limitations of human supervision in deployed AI-assisted systems is also among the under-explored methodologies, despite its conceptual emphasis as a safeguard against bias and opacity in border applications. Structured human-in-the-loop (HITL) protocols, which embed human oversight at critical stages like data validation and decision triage, represent a promising hybrid approach but lack validation in operational border settings. Authors of [100] provide a framework for tracing harm sources across the machine learning lifecycle, recommending iterative human audits to mitigate unintended risks such as erroneous profiling in surveillance tasks. In another important work in this field, authors of [69] expose intersectional biases in commercial gender classification, encouraging diverse human review to promote fairness in AI-aided identity verification at borders. In [101], its authors examine model inversion attacks under data protection laws, proposing HITL with explainability tools and audit trails to curb privacy breaches in inference processes. To bridge this gap, future work should conduct longitudinal pilots testing these HITL methodologies in OSINT/SOCMINT pipelines, evaluating their impact on accuracy, ethical compliance, and resource efficiency in real-world border deployments.

4.3. Limitations of This Study

While this review provides a comprehensive synthesis of the literature on AI-supported exploitation of open-source/social media-derived data (either explicitly labeled as OSINT and SOCMINT, or periphrastically described as such) for border protection, several limitations must be acknowledged, the majority of which stem from the heterogeneity of our data sources.

Specifically, the inclusion of non-peer-reviewed materials introduces potential risks of reporting bias and asymmetrical methodological rigor. Despite the systematic screening of sources and application of inclusion/exclusion criteria, the miscellany of publication types confined our ability to apply uniform quality benchmarks.

Additionally, the heterogeneity of the evidence base (e.g., included studies reporting conceptual models, prototypes, or pilot evaluations rather than field-tested deployments), limited the feasibility of conducting a quantitative meta-analysis, leading us to rely on qualitative syntheses and evidence matrices. These approaches, while providing systematized insights, cannot return pooled effect estimates or standardized performance benchmarks.

Finally, the variability of the types of selected studies, rendered the application of an established risk of bias assessment tool impractical, which is explicitly acknowledged as another limitation.

Collectively considering the above limitations, caution is suggested in generalizing the findings. Nevertheless, by combining evidence from diverse sources and presenting it transparently, this review provides a firm foundation for understanding the state of AI-assisted OSINT and SOCMINT in border security and identifying areas for future investigation.

4.4. Suggestions for Future Research

Focusing effectively on the identified gaps, necessitates a comprehensive approach to future research, mainly directing the efforts on technological advancement, ethical governance, and collaborative frameworks.

4.4.1. Development of Robust, Explainable, and Ethical AI Models

To address the empirical validation gap identified in RQ2, future research should prioritize the development of open-source prototype systems/frameworks that enable reproducible testing of LLM-enhanced OSINT/SOCMINT approaches, aiming to provide standardized evaluation environments where researchers and practitioners can assess system performance against curated datasets, representing diverse migration scenarios, threat typologies, and linguistic contexts. Open-source implementations facilitate transparency—a critical requirement for border agencies subject to austere legal accountability frameworks—while enabling the research community to identify failure modes, benchmark different approaches, and iteratively improve system effectiveness [102]. The importance of crowdsourced validation is underscored by research demonstrating that computational methods alone often produce high volumes of unverifiable information with low utility for expert analysts, requiring hybrid approaches that integrate human judgment [102]. The creation of domain-specific test datasets for migration flow assessment, including labeled social media corpora with ground truth annotations for events such as irregular crossings and smuggling operations, would establish essential evaluation infrastructure currently lacking in the field.

4.4.2. Longitudinal Studies on the Socio-Legal Impacts of AI-Assisted Border Management

To provide a more holistic picture of the efficacy and consequences of these technologies, future research should undertake meticulous, long-term empirical studies, which should extend beyond initial efficiency gains to assess the sustained operational impact of AI-assisted OSINT/SOCMINT systems on border security outcomes. Crucially, these research endeavors should also investigate the broader socio-legal implications, including the long-term effects on human rights, privacy, and civil liberties, particularly for vulnerable populations and non-citizens, while analyzing, in parallel, how the increasing digitalization of borders influences migratory patterns and whether it inadvertently pushes individuals towards more dangerous routes. Such studies would provide beneficial evidence for informing policy development and ensuring that technological advancements align with democratic values and human rights principles, an aspect which is highly pertinent to LLMs and agents, where the long-term societal effects of their widespread deployment in sensitive areas like border control are yet to be fully fathomed.

4.4.3. Fostering International Collaboration and Standardized Data Sharing Protocols

Given the transnational character of border security challenges and criminal networks, future research should investigate mechanisms for promoting greater international collaboration in the development and deployment of AI-supported intelligence systems. This involves investigating the creation of standardized data-sharing protocols that balance security imperatives with privacy protection and legal compliance across different jurisdictions. Research could examine successful models of cross-border intelligence sharing, particularly those leveraging unclassified OSINT, and identify the best practices for integrating diverse national systems. The aim should be to develop interoperable systems that enhance global security efforts while respecting national sovereignty and diverse legal frameworks. The ability of LLMs and agents to process and synthesize information from diverse sources could enhance this collaboration, but requires strongly defined, agreed-upon data governance frameworks.

Operationally, such collaboration could be facilitated through integrated monitoring frameworks that aggregate intelligence from multiple national sources while respecting data sovereignty constraints. For instance, a multinational early warning system for irregular migration flows could synthesize OSINT/SOCMINT signals from transit countries, destination states, and origin regions, providing participating agencies with shared situational awareness while maintaining appropriate access controls for sensitive national security information. LLM-based translation and cross-lingual information retrieval capabilities could enable seamless information-sharing among agencies operating in different linguistic contexts, addressing the multilingual scalability challenges highlighted in RQ2. Such systems could supplement existing bilateral and multilateral information-sharing mechanisms (such as Frontex’s operational coordination with EU member states) with automated, near-real-time intelligence fusion that enhances collective border management capabilities. Such synergetic efforts can be greatly facilitated by federated RAG variants, to enable privacy-preserving analysis across agencies, fusing multilingual SOCMINT signals without centralizing sensitive data [103]. Despite these benefits, empirical studies on RAG’s deployment in operational border environments remain scarce, representing a methodological gap fertile for investigation.

4.4.4. Exploring Novel Data Sources and Advanced Analytical Techniques

Continued innovation in data collection and analytical methodologies is vital. Future research could explore the utility of novel open-source data types and their integration with AI, moving beyond traditional social media and news sources. This might include exploring less conventional “grey data” sources while carefully navigating their legal and ethical implications. Methodologically, there is scope for further research into advanced ML techniques, such as graph neural networks for complex network analysis, reinforcement learning for optimizing resource allocation, or advanced natural language processing models for detecting subtle linguistic patterns in diverse dialects and slang used by criminal organizations.

Specifically, for LLMs and agents, future research should examine the following:

- •

- Multimodal Intelligence Fusion: Investigating how LMMs can effectively fuse and reason across diverse modalities (e.g., combining satellite imagery with social media text, or audio intercepts with dark web forum discussions) to create a fuller, more robustly framed intelligence picture for border security [104].

- •

- Proactive Threat Anticipation: Developing agentic systems that can autonomously monitor emerging online trends, identify nascent criminal typologies, and even simulate potential adversarial actions based on OSINT/SOCMINT data, providing early warnings to border agencies.

- •

- Automated Vetting and Insider Threat Detection: Researching the application of LLMs to analyze vast amounts of publicly available information and internal communications for vetting purposes, identifying subtle indicators of insider threat risk, while rigorously addressing privacy and bias concerns.

- •

- Adaptive Language Intelligence: Advancing LLMs to better understand and adapt to evolving slang, code-switching, and encrypted communications used by transnational criminal organizations, providing real-time translation and contextual analysis for border personnel.

- •

- Human–Agent Teaming Paradigms: Designing optimal human–agent teaming models where LLM-powered agents act as intelligent assistants, offloading repetitive tasks and providing rapid insights, while human analysts retain ultimate decision-making authority and provide critical ethical oversight. Integrating RAG via LangChain in human–agent teaming allows verification agents to dynamically retrieve evidence from external sources and reduce hallucinations in intelligence triage. Pilots could test this for border simulations, enhancing RQ2 reliability through modular, adaptive workflows [105].

- •

- Ethical Red Teaming for LLMs: Conducting rigorous red teaming exercises specifically for LLM and agent-based systems in border security to identify and mitigate potential biases, vulnerabilities, and unintended consequences before deployment.

Research into how to effectively train non-programmers in leveraging these advanced tools for OSINT analysis is also crucial for building future intelligence capabilities.

4.4.5. Creative Synthesis: Envisaging Prospective Human-Agent Teaming

Synthesizing the capabilities and addressing the challenges identified in the literature allows for the conceptualization of novel, integrated systems for border protection. These concepts are inspired from the current trajectory of peer-reviewed research and represent a shift from using AI as a simple tool to creating sophisticated human–agent teams where specialized agents perform distinct operational, analytical, and ethical functions. An envisaged Integrated Migration Flow Assessment System would deploy specialized LLM-powered agents operating in a coordinated fashion, as follows:

- •

- Source Monitoring Agent: Continuously ingesting and processing data from social media platforms (Twitter/X, Facebook, Telegram, etc.), online forums, news feeds, and media to identify migration-relevant signals in real-time across multiple languages and dialects. Research demonstrates that multimodal agents capable of handling text, images, and video can significantly enhance entity recognition and event interpretation for intelligence operations. Future multi-agent architectures could employ LangChain’s retriever chains with RAG to distribute OSINT queries across specialized agents, grounding outputs in federated vector stores to achieve accuracy gains in threat detection.

- •

- Pattern Analysis Agent: Employing advanced natural language processing and machine learning to detect subtle linguistic patterns, code-switching, and emergent terminology used by smuggling networks, enabling the identification of facilitation operations that evade traditional keyword-based detection [106]. Studies show that AI-powered narrative analysis can assist in mitigating the weaponization of social media through early detection of coordinated disinformation campaigns [107].

- •

- Network Mapping Agent: Constructing dynamic knowledge graphs that link entities—individuals, organizations, routes, transit hubs, and communication channels—to reveal the structure and evolution of irregular migration facilitation networks operating across borders. Graph foundation models have demonstrated efficacy in uncovering online information operations across multiple countries, suggesting applicability to transnational criminal network detection.

- •

- Strategic Foresight Agent: Synthesizing macro-indicators (fluctuating demographics, economic data, climate events, political instability, conflict zones, etc.) [14] with micro-level social media signals to generate early warning assessments of potential migration flow shifts [108], enabling proactive resource allocation and humanitarian response planning. This addresses the need for crowdsourced intelligence frameworks that can scale investigations while maintaining ethical oversight.

- •

- Human–AI Interface Agent: Providing operational analysts with natural language query capabilities to interrogate the integrated intelligence picture, asking complex questions such as ‘Correlate social media activity patterns in Region X with historical migration route data and identify anomalous movements in the past 72 h’ [44]. Recent advances in generative AI for critical infrastructure protection demonstrate that agentic AI systems can support proactive defense mechanisms while maintaining human oversight. LangChain’s LangGraph can orchestrate multi-agent RAG systems where exploration agents fetch SOCMINT signals and analysis agents fuse them with official databases, to achieve higher scores in entity recognition. This hybrid approach bridges RQ1 applications with real-time evidence grounding [105].

- •

- The GELSI Compliance and Oversight Agent: Addressing the critical governance gap identified in the literature, a dedicated “Ethical Oversight Agent” could be deployed. This agent’s sole function would not be intelligence gathering, but rather the real-time auditing of all other operational AI systems. Programmed with the specific constraints of data protection laws, human rights principles, and agency policies, this agent would act as an automated, internal overseer. It would monitor data access logs to prevent privacy violations, analyze the outputs of risk assessment models for statistical evidence of bias against protected groups, and create an immutable record of all AI-supported actions, to be reported to human overseers.

5. Conclusions

This SLR has synthesized evidence at the intersection of AI and OSINT/SOCMINT in the context of border protection, following PRISMA 2020 guidelines. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically integrate these three components, mapping both the technological opportunities and the governance challenges.

The findings structured around the three research questions reveal a nuanced picture. For RQ1 (Effectiveness and Application of AI), our evidence base, distributed per operational area, indicate that classical ML and NLP dominate the landscape, accounting for the vast majority of studies with 19 and 17 entries, respectively. The following AI-supported approaches, include DL (8), CV (7), LLMs/Agents (6), Bayesian/Statistical/Time series (3) and lastly KGs (2). LLMs, while innovative (e.g., for generative synthesis or multimodal fusion), are underrepresented—often limited to conceptual reviews, pilots, or post-2023 studies (ChatGPT era), as only ~14% of entries involve LLMs, reflecting RQ2 limitations like hallucinations and compute demands in critical environments. Yet, they exhibit an ascending trend within the short timeframe of their emergence, which calls for further research to validate their deployment in high-stakes environments, leveraging supportive technologies such as LangChain for RAG-enhanced reliability.

For RQ2 (Limitations), the review highlights persistent technical, operational, and data challenges, such as misinformation, dataset bias, adversarial manipulation, and issues of scalability. These limitations directly affect the reliability and trustworthiness of AI-generated insights, underscoring the need for stronger validation frameworks and standardized evaluation metrics.

For RQ3 (Ethical, Legal, and Societal Implications), concerns regarding surveillance overreach, privacy intrusions, accountability gaps, and potential discrimination are pervasive. Governance frameworks diverge significantly across contexts, with the EU favoring compliance-first approaches under the AI Act, and the U.S. prioritizing operational flexibility through DHS-led initiatives. This divergence illustrates the broader policy dilemma of balancing efficiency with ethical safeguards in high-stakes border management.

Beyond answering the research questions, this review makes three contributions. First, it consolidates a fragmented evidence base into a structured synthesis, clarifying where empirical validation exists and where conceptual/theoretical approaches preponderate. Second, it identifies critical gaps, particularly in empirical testing, standardized performance metrics, and models for human–AI teaming. Third, it situates the discussion within a policy context by comparing U.S. and EU approaches, offering insights into how governance choices shape both risks and opportunities. In this fragmented research landscape, which is dispersed across technical silos, policy debates, and pressing ethical dilemmas, our SLR may serve as a vital compass for future explorers. High fragmentation in AI-OSINT/SOCMINT for border protection call for special consideration: siloed studies overlook holistic integration, from multimodal fusion to governance. Authors should prioritize this convergence by using and enriching our publicly available dataset as a starting point to build unified frameworks, test LLM/agentic innovations, and validate cross-jurisdictional applications. This resource not only bridges gaps but ignites collaborative voyages toward resilient, rights-respecting border intelligence.

Industries to potentially benefit from this research include border management agencies (e.g., U.S. CBP and EU Frontex, handling 280 million annual crossings), law enforcement (e.g., Interpol for transnational crime networks), cybersecurity firms (e.g., those powering SOCMINT platforms like Recorded Future), and NGOs. These sectors face escalating threats to cross-border stability that may be further amplified by the malicious use of advanced technologies. The practical implications are clear: AI-assisted OSINT and SOCMINT should not be viewed as replacements for human expertise but as augmentative tools requiring careful integration, oversight, and ethical design. Policymakers must recognize that adversaries already exploit these technologies, making responsible innovation both urgent and necessary.

In conclusion, while AI-assisted OSINT and SOCMINT hold transformative potential for enhancing border protection; their promise can only be realized if operational deployment is accompanied by rigorous validation, robust governance, and sustained ethical oversight. By clarifying the current state of research, identifying critical gaps, and highlighting policy implications, this review provides a foundation for advancing both scholarship and practice in this evolving domain of global security.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/info16121095/s1, PRISMA Checklist [23].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and K.K.; methodology, A.K. and K.K.; formal analysis, A.K. and K.K.; investigation, A.K. and K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. and K.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K. and K.K.; visualization, A.K. and K.K.; supervision, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The curated evidence base is provided as open Supplementary Material under the article’s CC BY 4.0 license at an OSF project repository. No primary data was generated.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments, which have significantly enhanced the clarity, depth, and methodological rigor of this manuscript. Individual icons in the graphical abstract were generated using the Gemini 3 AI model (Nano Banana); The final conceptualization, structuring, and design of the image were executed by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| OSINT | Open-Source Intelligence |

| SOCMINT | Social Media Intelligence |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| CV | Computer Vision |

| LLM | Large Language Model(s) |

| LMM | Large Multimodal Model(s) |

| RQ | Research Question(s) |

| GELSI | Governance, Ethical, Legal, and Societal Implications |

| EU | European Union |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| EUAA | European Union Agency for Aylum |

| EDPS | European Data Protection Supervisor |

| CBP | Customs and Border Protection |

| DHS | Department of Homeland Security |

| TCO | Transnational Criminal Organization(s) |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| SARIMA | Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |