Chain-of-Thought Prompt Optimization via Adversarial Learning

Abstract

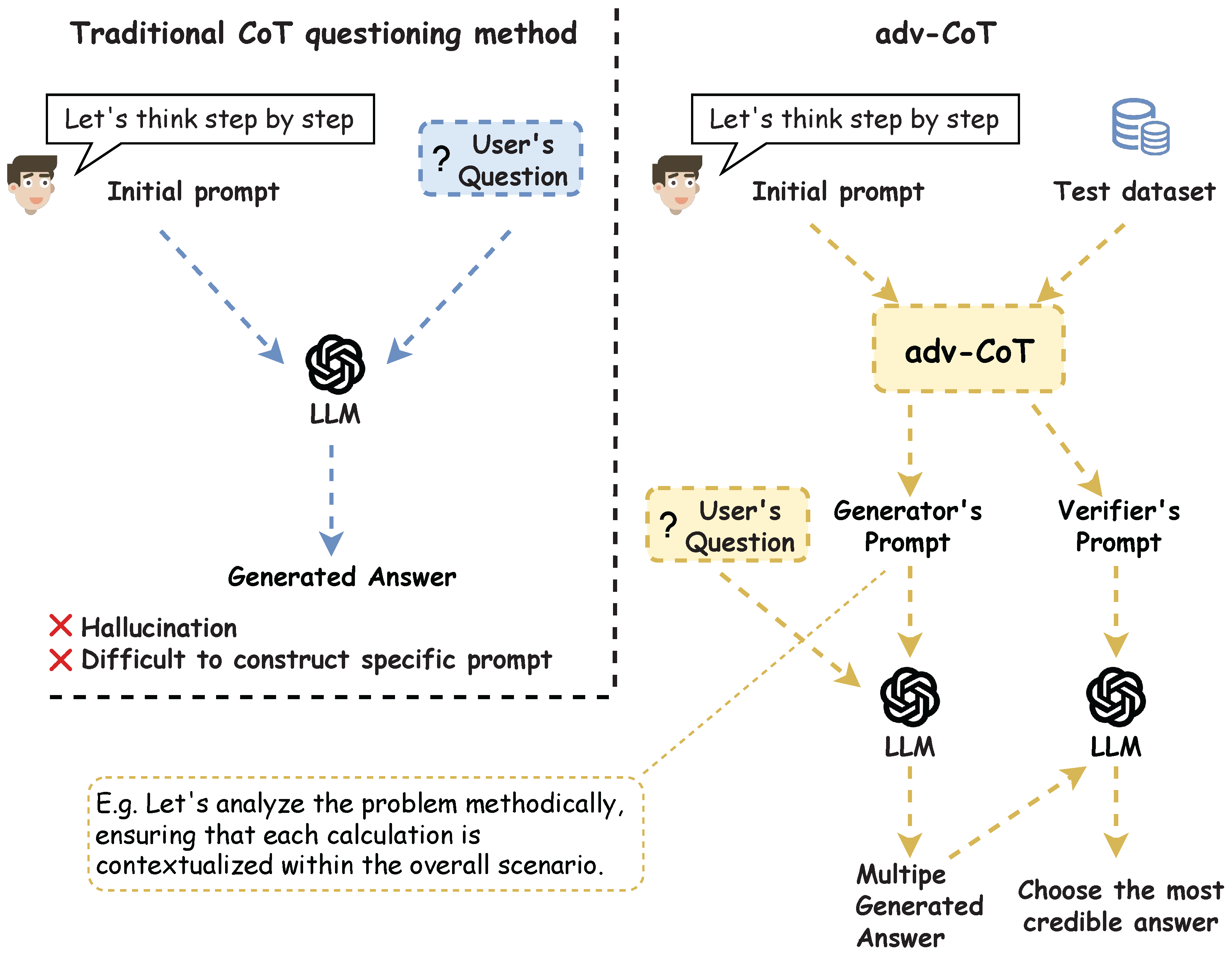

1. Introduction

- RQ1.

- How can we design a principled and scalable mechanism to refine CoT prompts without model fine-tuning, enabling iterative improvement through structured adversarial feedback?

- RQ2.

- Can adversarial interactions between generator and discriminator expose weaknesses in reasoning chains and drive more accurate, stable, and error-resistant CoT reasoning across diverse datasets and task types?

- RQ3.

- How can explicit verification signals be integrated into the optimization loop to evaluate and enhance the reliability of the generated reasoning paths and final answers?

2. Related Work

2.1. Prompt Optimization for Chain-of-Thought Reasoning

2.2. Adversarial Training

3. Key Components and Terminology

4. Methods

4.1. Adversarial Learning

4.2. Feedback

4.3. Adversarial Learning Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Adversarial Chain-of-Thought Optimization |

|

4.4. Verifier

5. Experimental Setup

5.1. Datasets

5.2. Backbone Models

5.3. Baselines

5.4. Evaluation Metrics

5.5. Implementation Details

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Results

6.2. Significance Analysis

6.3. Ablation Study

6.3.1. Ablation Study on Feedback and Verification Modules

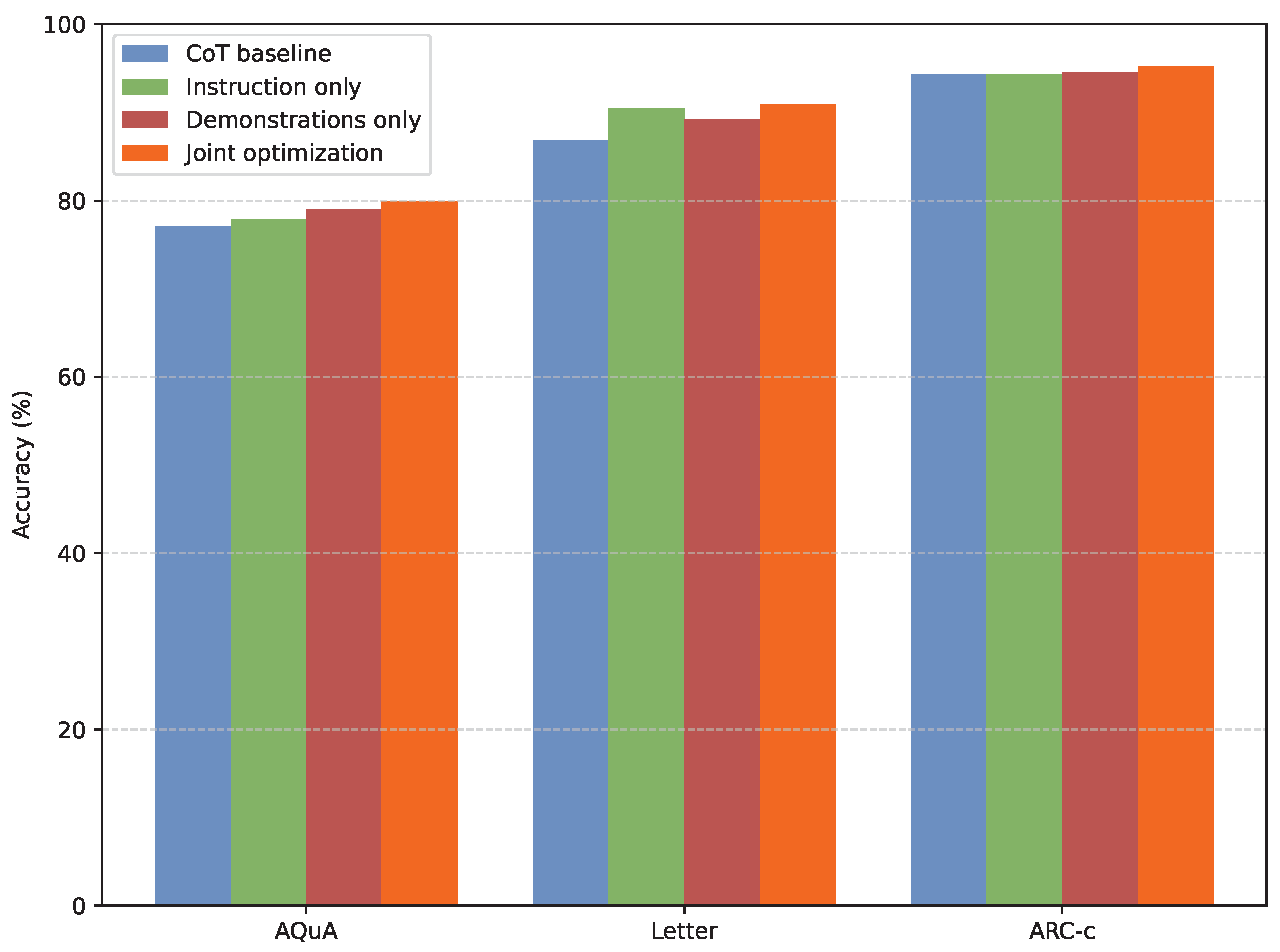

6.3.2. Ablation on Instruction–Demonstration Contributions

6.4. Discussion

6.4.1. Difference Between Verification and Self-Consistency

6.4.2. Cross-Model Generalization Analysis

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| adv-CoT | Adversarial Chain-of-Thought |

| adv-ICL | Adversarial In-Context Learning |

| CoT | Chain-of-Thought |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| SC | Self-Consistency |

Appendix A. Statistics of Datasets

| Dataset | Number of Samples | Average Words | Answer Format | Licence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSQA | 1221 | 27.8 | Multi-choice | Unspecified |

| StrategyQA | 2290 | 9.6 | Yes or No | Apache-2.0 |

| OpenBookQA | 500 | 27.6 | Multi-choice | Unspecified |

| ARC-c | 1172 | 47.5 | Multi-choice | CC BY SA-4.0 |

| Sports | 1000 | 7.0 | Yes or No | Apache-2.0 |

| BoolQ | 3270 | 8.7 | Yes or No | CC BY SA-3.0 |

| Last Letters | 500 | 15.0 | String | Unspecified |

| Coin Flip | 500 | 37.0 | Yes or No | Unspecified |

| GSM8K | 1319 | 46.9 | Number | MIT License |

| SVAMP | 1000 | 31.8 | Number | MIT License |

| AQuA | 254 | 51.9 | Multi-choice | Apache-2.0 |

| MultiArith | 600 | 31.8 | Number | CC BY SA-4.0 |

- CSQA [49]: This is a multiple-choice question answering dataset that evaluates models’ ability to apply commonsense knowledge in reasoning tasks. It contains diverse questions that require understanding everyday situations beyond factual recall. The homepage is https://github.com/jonathanherzig/commonsenseqa (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- StrategyQA [50]: This is a commonsense QA task with a Yes or No answer format. We use the open-domain setting (question-only set) from [53]: https://github.com/google/BIG-bench/tree/main/bigbench/benchmark_tasks/strategyqa (accessed on 3 December 2025). The original dataset is from https://github.com/eladsegal/strategyqa (accessed on 3 December 2025), MIT license: https://github.com/eladsegal/strategyqa/blob/main/LICENSE (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- OpenBookQA [51]: This is a multi-choice QA task to evaluate commonsense knowledge. The original dataset is from https://allenai.org/data/open-book-qa (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- ARC-c [52]: This is a multiple-choice commonsense QA task. The original dataset is from https://allenai.org/data/arc (accessed on 3 December 2025). CC BY SA-4.0 license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Sports understanding from BIG-Bench [53]: The answer format is Yes or No. The homepage is https://github.com/google/BIG-bench/tree/main/bigbench/benchmark_tasks/sports_understanding (accessed on 3 December 2025). Apache License v.2: https://github.com/google/BIG-bench/blob/main/LICENSE (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- BoolQ [54]: This is a knowledge-intensive task, and the format is Yes or No. The original dataset is from https://github.com/google-research-datasets/boolean-questions (accessed on 3 December 2025). CC BY SA-3.0 license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Last Letters & Coin Flip [9]: These are novel benchmarks to evaluate whether the LLM can solve a simple symbolic reasoning problem. The last letters dataset is from https://huggingface.co/datasets/ChilleD/LastLetterConcat (accessed on 3 December 2025). The coin flip dataset is from https://huggingface.co/datasets/skrishna/coin_flip (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- GSM8K [55]: This is a dataset of grade school math word problems that evaluates a model’s ability to perform multi-step numerical reasoning. The homepage is https://github.com/openai/grade-school-math (accessed on 3 December 2025). MIT license: https://github.com/openai/grade-school-math/blob/master/LICENSE (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- SVAMP [56]: This is a benchmark of elementary math word problems designed to test a model’s ability to generalize reasoning by altering problem structures and wording. The homepage is https://github.com/arkilpatel/SVAMP (accessed on 3 December 2025), MIT license: https://github.com/arkilpatel/SVAMP/blob/main/LICENSE (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- AQuA [57]: This is a dataset of algebraic word problems with multiple-choice answers, aimed at evaluating the mathematical reasoning and problem-solving skills of models. The homepage is https://github.com/deepmind/AQuA (accessed on 3 December 2025), license: https://github.com/deepmind/AQuA/blob/master/LICENSE (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- MultiArith [58]: This is a dataset of arithmetic word problems that require multi-step reasoning to combine numbers and operations for the correct answer. The homepage is https://huggingface.co/datasets/ChilleD/MultiArith (accessed on 3 December 2025).

Appendix B. Extended Experiments

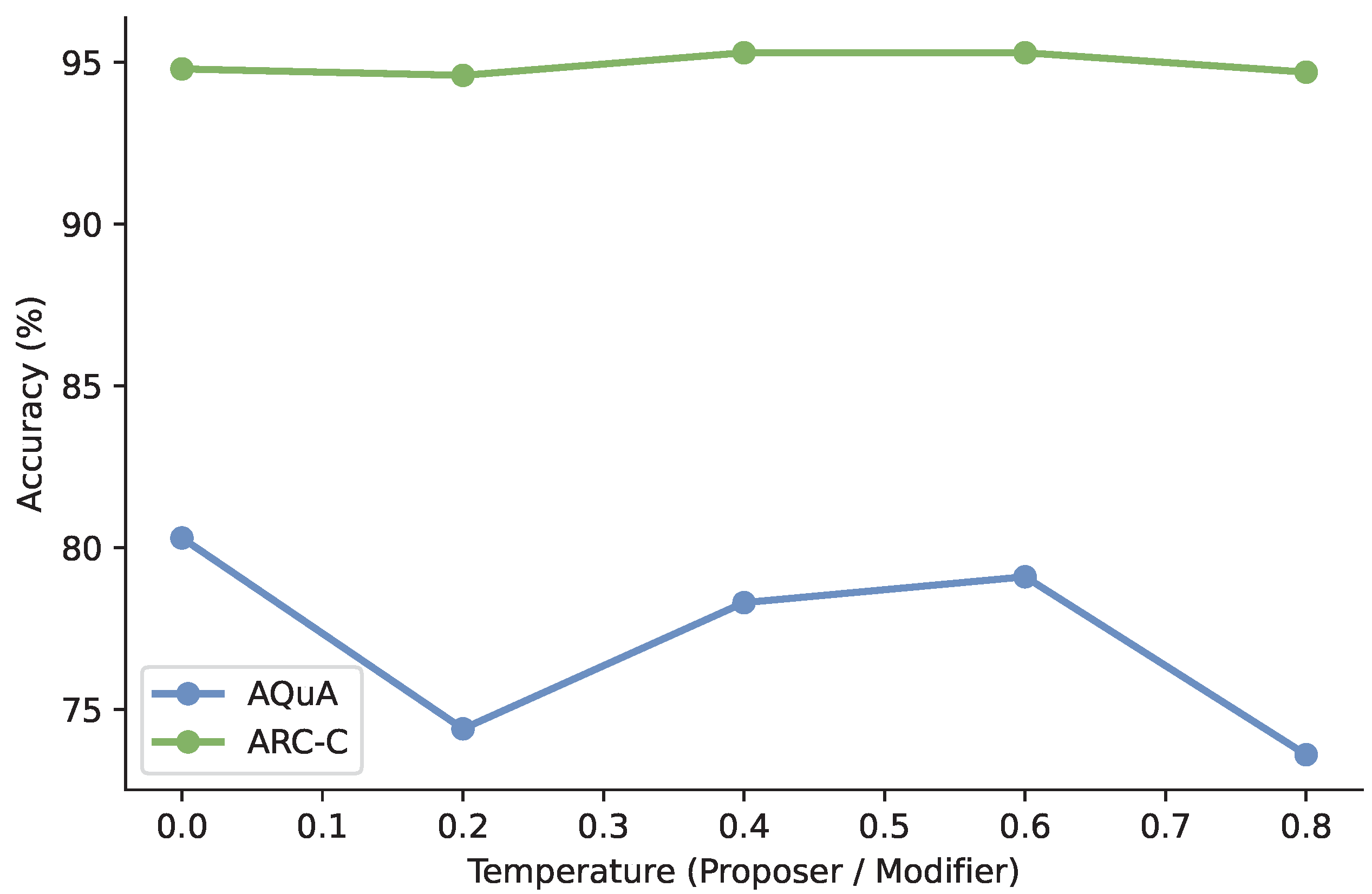

Appendix B.1. Temperature of Proposer and Modifier

Appendix B.2. Ablation Studies on Number of Iterations and Data Samples

| MultiArith (%) | ARC-C (%) | Sports (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 97.6 | 72.7 | 60.1 |

| 2 | 95.0 | 76.6 | 51.1 | |

| 3 | 98.1 | 80.8 | 50.8 | |

| 4 | 97.8 | 81.9 | 65.6 | |

| 5 | 96.6 | 78.4 | 64.1 | |

| 3 | 1 | 98.3 | 78.7 | 61.9 |

| 2 | 98.3 | 80.5 | 66.1 | |

| 3 | 98.8 | 80.7 | 78.9 | |

| 4 | 98.6 | 79.9 | 71.3 | |

| 5 | 98.0 | 79.7 | 58.0 | |

| 5 | 1 | 98.1 | 71.9 | 82.1 |

| 2 | 97.6 | 75.1 | 76.9 | |

| 3 | 98.3 | 79.9 | 88.7 | |

| 4 | 97.6 | 78.8 | 57.5 | |

| 5 | 97.8 | 77.8 | 76.4 | |

| 7 | 1 | 97.6 | 73.8 | 85.6 |

| 2 | 98.0 | 75.4 | 89.5 | |

| 3 | 98.0 | 82.4 | 80.7 | |

| 4 | 97.5 | 79.9 | 77.8 | |

| 5 | 97.5 | 80.7 | 84.8 |

Appendix C. Prompt

Appendix C.1. Generator Initial Prompt

Appendix C.2. Discriminator Initial Prompt

Appendix C.3. Proposer Prompt for Generator’s Instruction

Appendix C.4. Proposer Prompt for Generator’s Demonstrations

Appendix C.5. Proposer Prompt for Discriminator’s Instruction

Appendix C.6. Proposer Prompt for Discriminator’s Demonstrations

Appendix C.7. Modifier Prompt for Generator’s Instruction

Appendix C.8. Modifier Prompt for Generator’s Demonstrations

Appendix C.9. Modifier Prompt for Discriminator’s Instruction

Appendix C.10. Modifier Prompt for Discriminator’s Demonstrations

References

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Rae, J.W.; Borgeaud, S.; Cai, T.; Millican, K.; Hoffmann, J.; Song, F.; Aslanides, J.; Henderson, S.; Ring, R.; Young, S.; et al. Scaling Language Models: Methods, Analysis & Insights from Training Gopher. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.11446. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Zhu, J. Foundations of large language models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.09223. [Google Scholar]

- Min, S.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Hajishirzi, H. Metaicl: Learning to learn in context. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA, 10–15 July 2022; pp. 2791–2809. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Q.; Li, L.; Dai, D.; Zheng, C.; Ma, J.; Li, R.; Xia, H.; Xu, J.; Wu, Z.; Chang, B.; et al. A survey on in-context learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 1107–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Dherin, B.; Munn, M.; Mazzawi, H.; Wunder, M.; Gonzalvo, J. Learning without training: The implicit dynamics of in-context learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.16003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, T.; Gu, S.S.; Reid, M.; Matsuo, Y.; Iwasawa, Y. Large language models are zero-shot reasoners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 22199–22213. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Yu, D.; Zhao, J.; Shafran, I.; Griffiths, T.; Cao, Y.; Narasimhan, K. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 11809–11822. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Y.; Zhu, M.; Xia, F.; Li, B.; He, S.; Liu, S.; Sun, B.; Liu, K.; Zhao, J. Large language models are better reasoners with self-verification. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 2550–2575. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, A.; Li, M.; Smola, A. Automatic Chain of Thought Prompting in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, N.; Frieske, R.; Yu, T.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; Ishii, E.; Bang, Y.J.; Madotto, A.; Fung, P. Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Ren, R.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, W.X.; Nie, J.Y.; Wen, J.R. The dawn after the dark: An empirical study on factuality hallucination in large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.03205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Jain, S.; Kankanhalli, M. Hallucination is inevitable: An innate limitation of large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.11817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yin, Z.; Guo, Q.; Wu, J.; Qiu, X.; Zhao, H. Benchmarking hallucination in large language models based on unanswerable math word problem. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.03558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Schuurmans, D.; Le, Q.; Chi, E.; Narang, S.; Chowdhery, A.; Zhou, D. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.11171. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Du, C.; Pang, T.; Liu, Q.; Gao, W.; Lin, M. Chain of Preference Optimization: Improving Chain-of-Thought Reasoning in LLMs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; Globerson, A., Mackey, L., Belgrave, D., Fan, A., Paquet, U., Tomczak, J., Zhang, C., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 37, pp. 333–356. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, S.; Wang, P.; Lin, Y.; Pan, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T. Active prompting with chain-of-thought for large language models. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; pp. 1330–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Gong, S.; Chen, L.; Zheng, L.; Gao, J.; Shi, H.; Wu, C.; Jiang, X.; Li, Z.; Bi, W.; et al. Diffusion of Thought: Chain-of-Thought Reasoning in Diffusion Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; Globerson, A., Mackey, L., Belgrave, D., Fan, A., Paquet, U., Tomczak, J., Zhang, C., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 37, pp. 105345–105374. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, W.; Jia, P.; Zhao, X. TAPO: Task-Referenced Adaptation for Prompt Optimization. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025—2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Hyderabad, India, 6–11 April 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Larionov, D.; Eger, S. Promptoptme: Error-aware prompt compression for llm-based mt evaluation metrics. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.16120. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P.F.; Tsai, Y.D.; Lin, S.D. Benchmarking large language model uncertainty for prompt optimization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.10044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2014/hash/f033ed80deb0234979a61f95710dbe25-Abstract.html (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Radford, A.; Metz, L.; Chintala, S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.06434. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Zaremba, W.; Sutskever, I.; Bruna, J.; Erhan, D.; Goodfellow, I.; Fergus, R. Intriguing properties of neural networks. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6199. [Google Scholar]

- Biggio, B.; Corona, I.; Maiorca, D.; Nelson, B.; Šrndić, N.; Laskov, P.; Giacinto, G.; Roli, F. Evasion attacks against machine learning at test time. In Proceedings of the Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Prague, Czech Republic, 22–26 September 2013; pp. 387–402. [Google Scholar]

- Long, D.; Zhao, Y.; Brown, H.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, N.; Kawaguchi, K.; Shieh, M.; He, J. Prompt optimization via adversarial in-context learning. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; pp. 7308–7327. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Muresanu, A.I.; Han, Z.; Paster, K.; Pitis, S.; Chan, H.; Ba, J. Large language models are human-level prompt engineers. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, Online, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pryzant, R.; Iter, D.; Li, J.; Lee, Y.T.; Zhu, C.; Zeng, M. Automatic prompt optimization with “gradient descent” and beam search. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.03495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Liu, X.; Zheng, K.; Ke, P.; Wang, H.; Dong, Y.; Tang, J.; Huang, M. Black-box prompt optimization: Aligning large language models without model training. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.04155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.; Wistuba, M.; Klein, A.; Golebiowski, J.; Zappella, G.; Merra, F.A. Hyperband-based Bayesian optimization for black-box prompt selection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.07820. [Google Scholar]

- Lightman, H.; Kosaraju, V.; Burda, Y.; Edwards, H.; Baker, B.; Lee, T.; Leike, J.; Schulman, J.; Sutskever, I.; Cobbe, K. Let’s verify step by step. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Wang, W.; Feng, F.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chua, T.S. Robust prompt optimization for large language models against distribution shifts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.13954. [Google Scholar]

- Ashok, D.; May, J. Language models can predict their own behavior. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.13329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledig, C.; Theis, L.; Huszár, F.; Caballero, J.; Cunningham, A.; Acosta, A.; Aitken, A.; Tejani, A.; Totz, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Photo-realistic single image super-resolution using a generative adversarial network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4681–4690. [Google Scholar]

- Ganin, Y.; Ustinova, E.; Ajakan, H.; Germain, P.; Larochelle, H.; Laviolette, F.; March, M.; Lempitsky, V. Domain-adversarial training of neural networks. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2016, 17, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng, E.; Hoffman, J.; Saenko, K.; Darrell, T. Adversarial discriminative domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7167–7176. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, G.; Talavera, E.; Díaz-Álvarez, A. A survey on GANs for computer vision: Recent research, analysis and taxonomy. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2023, 48, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Cai, Y.; Li, Q. Unlocking the Power of GANs in Non-Autoregressive Text Generation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.03977. [Google Scholar]

- Maus, N.; Chao, P.; Wong, E.; Gardner, J. Black box adversarial prompting for foundation models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.04237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y. Seqgan: Sequence generative adversarial nets with policy gradient. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, W.; Narodytska, N.; Patel, A. Relgan: Relational generative adversarial networks for text generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Lu, S.; Cai, H.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J. Long text generation via adversarial training with leaked information. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, C.; Gan, Z.; Wang, W.; Shen, D.; Wang, G.; Wen, Z.; Carin, L. Improving Adversarial Text Generation by Modeling the Distant Future. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 2516–2531. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Qian, Z.; Huang, K.; Zhang, R.; Xiao, J.; He, Y.; Lu, C. Robust generative adversarial network. Mach. Learn. 2023, 112, 5135–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, Q.; Li, X.; Gao, M. Boosting language models reasoning with chain-of-knowledge prompting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.06427. [Google Scholar]

- Talmor, A.; Herzig, J.; Lourie, N.; Berant, J. COMMONSENSEQA: A Question Answering Challenge Targeting Commonsense Knowledge. In Proceedings of the NAACL-HLT, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4149–4158. [Google Scholar]

- Geva, M.; Khashabi, D.; Segal, E.; Khot, T.; Roth, D.; Berant, J. Did aristotle use a laptop? a question answering benchmark with implicit reasoning strategies. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2021, 9, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylov, T.; Clark, P.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A. Can a suit of armor conduct electricity? a new dataset for open book question answering. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1809.02789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, P.; Cowhey, I.; Etzioni, O.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A.; Schoenick, C.; Tafjord, O. Think you have solved question answering? Try arc, the ai2 reasoning challenge. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.05457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Rastogi, A.; Rao, A.; Shoeb, A.A.; Abid, A.; Fisch, A.; Brown, A.R.; Santoro, A.; Gupta, A.; Garriga-Alonso, A.; et al. Beyond the imitation game: Quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 2023, 1–95. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C.; Lee, K.; Chang, M.W.; Kwiatkowski, T.; Collins, M.; Toutanova, K. Boolq: Exploring the surprising difficulty of natural yes/no questions. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.10044. [Google Scholar]

- Cobbe, K.; Kosaraju, V.; Bavarian, M.; Chen, M.; Jun, H.; Kaiser, L.; Plappert, M.; Tworek, J.; Hilton, J.; Nakano, R.; et al. Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.14168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Bhattamishra, S.; Goyal, N. Are NLP models really able to solve simple math word problems? arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.07191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W.; Yogatama, D.; Dyer, C.; Blunsom, P. Program induction by rationale generation: Learning to solve and explain algebraic word problems. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.04146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Roth, D. Solving general arithmetic word problems. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.01413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Yang, A.; Fan, A.; et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods | Commonsense & Factual | Symbolic | Arithmetic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSQA | Strategy QA | OpenBook QA | ARC-c | Sports | BoolQ | Letter | Coin | GSM8K | SVAMP | AQuA | MultiArith | |

| GPT-3.5-turbo | ||||||||||||

| CoT | 78.2 | 73.8 | 85.6 | 88.4 | 87.3 | 69.2 | 65.6 | 77.2 | 82.2 | 83.3 | 62.2 | 97.6 |

| Auto-CoT | 77.2 | 66.2 | 83.3 | 86.1 | 86.3 | 70.1 | 70.3 | 100 | 78.2 | 82.3 | 59.8 | 96.6 |

| adv-ICL | 77.8 | 66.6 | 86.4 | 87.2 | 86.3 | 73.1 | 74.6 | 96.8 | 80.4 | 84.1 | 60.2 | 98.5 |

| adv-CoT | 78.2 ± 0.0 | 73.3 ↓ 0.5 | 86.8 ↑ 0.4 | 89.5 ↑ 1.1 | 91.8 ↑ 4.5 | 73.5 ↑ 0.4 | 76.0 ↑ 1.4 | 98.4 ↓ 1.6 | 85.9 ↑ 3.7 | 85.3 ↑ 1.2 | 66.1 ↑ 3.9 | 99.1 ↑ 0.6 |

| CoT+SC | 79.4 | 74.5 | 86.0 | 88.3 | 89.4 | 67.0 | 66.6 | 99.2 | 87.5 | 86.8 | 65.3 | 98.6 |

| GPT-4o-mini | ||||||||||||

| CoT | 84.9 | 77.4 | 94.1 | 94.3 | 92.3 | 77.1 | 86.8 | 100 | 93.4 | 93.6 | 77.1 | 98.1 |

| Auto-CoT | 84.3 | 67.8 | 94.6 | 95.3 | 56.2 | 77.3 | 89.0 | 99.8 | 90.1 | 93.8 | 79.1 | 98.6 |

| adv-ICL | 83.9 | 76.1 | 94.0 | 94.7 | 89.8 | 77.1 | 87.4 | 100 | 92.7 | 93.4 | 78.7 | 98.6 |

| adv-CoT | 84.8 ↓ 0.1 | 79.3 ↑ 1.9 | 94.8 ↑ 0.2 | 95.3 ± 0.0 | 93.1 ↑ 0.8 | 77.5 ↑ 0.2 | 91.0 ↑ 2.0 | 100 ± 0.0 | 93.7 ↑ 0.3 | 94.1 ↑ 0.3 | 79.9 ↑ 0.8 | 98.6 ± 0.0 |

| CoT+SC | 85.6 | 77.5 | 95.1 | 94.6 | 90.6 | 77.5 | 88.2 | 100 | 94.2 | 94.6 | 83.4 | 98.3 |

| Llama-3-8B-Instruct | ||||||||||||

| CoT | 73.6 | 61.3 | 77.0 | 80.3 | 86.8 | 59.4 | 57.1 | 89.6 | 79.6 | 86.7 | 48.4 | 97.5 |

| Auto-CoT | 68.8 | 51.3 | 67.6 | 69.1 | 63.7 | 49.1 | 66.0 | 92.8 | 66.7 | 62.6 | 50.0 | 78.1 |

| adv-ICL | 73.5 | 40.6 | 77.0 | 76.3 | 85.9 | 60.0 | 61.1 | 82.8 | 80.5 | 86.8 | 38.5 | 97.8 |

| adv-CoT | 74.0 ↑ 0.4 | 62.3 ↑ 1.0 | 74.6 ↓ 2.4 | 81.4 ↑ 1.1 | 83.8 ↓ 3.0 | 62.5 ↑ 2.5 | 61.6 ↓ 4.4 | 89.0 ↓ 3.8 | 82.3 ↑ 1.8 | 86.9 ↑ 0.1 | 53.1 ↑ 3.1 | 97.6 ↓ 0.2 |

| CoT+SC | 77.2 | 66.0 | 80.4 | 85.4 | 91.4 | 61.3 | 59.0 | 96.8 | 85.6 | 90.4 | 57.8 | 98.0 |

| Model | Mean Improvement (%) | Paired t-Test p | 95% Bootstrap CI | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-3.5-turbo | 4.44 | 0.0266 | [1.76, 8.04] | 0.739 |

| GPT-4o-mini | 1.08 | 0.0134 | [0.47, 1.83] | 0.849 |

| Llama-3-8B | 0.98 | 0.189 | [−0.32, 2.27] | 0.404 |

| Test Model | GPT-4o-mini | DeepSeek-V3.2-Exp | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Train Model | |||

| None | 77.1/86.8/92.3 | 88.1/96.3/95.3 | |

| GPT-4o-mini | 79.9/88.6/93.1 | 89.3/96.8/94.5 | |

| DeepSeek-V3.2-Exp | 80.7/86.2/93.0 | 89.7/96.4/96.2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, G.; Cai, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, J. Chain-of-Thought Prompt Optimization via Adversarial Learning. Information 2025, 16, 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121092

Yang G, Cai X, Wang S, Liu J. Chain-of-Thought Prompt Optimization via Adversarial Learning. Information. 2025; 16(12):1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121092

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Guang, Xiantao Cai, Shaohe Wang, and Juhua Liu. 2025. "Chain-of-Thought Prompt Optimization via Adversarial Learning" Information 16, no. 12: 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121092

APA StyleYang, G., Cai, X., Wang, S., & Liu, J. (2025). Chain-of-Thought Prompt Optimization via Adversarial Learning. Information, 16(12), 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121092