Abstract

In the field of communication maintenance, Augmented Reality (AR) applications are critical for enhancing operational safety and efficiency. However, deploying the required multimodal models on resource-constrained terminal devices is challenging, as traditional cloud or on-device strategies fail to balance low latency and energy consumption. This paper proposes a Cloud-Edge-End collaborative inference framework tailored to multimodal model deployment. A subgraph partitioning strategy is introduced to systematically decompose complex multimodal models into functionally independent sub-units. Subsequently, a fine-grained performance estimation model is employed to accurately characterize both computation and communication costs across heterogeneous devices. And, a joint optimization problem is formulated to minimize end-to-end inference latency and terminal energy consumption. To solve this problem efficiently, a Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for DNN Partitioning (HGA-DP) evolved over 100 generations is designed, incorporating constraint-aware repair mechanisms and local neighborhood search to navigate the exponential search space of possible deployment combinations. Experimental results on a simulated three-tier collaborative computing platform demonstrate that, compared to traditional full on-device deployment, the proposed method reduces end-to-end inference latency by 70–80% and terminal energy consumption by 81.1%, achieving a 4.86× improvement in overall fitness score. Against the latency-optimized DADS heuristic, HGA-DP achieves 41.3% lower latency while reducing energy by 59.9%. Compared to the All-Cloud strategy, our approach delivers 71.5% latency reduction with only marginal additional terminal energy cost. This framework provides an adaptive and effective solution for real-time multimodal inference in resource-constrained scenarios, laying a foundation for intelligent, resource-aware deployment.

1. Introduction

In the domain of communication maintenance, ensuring the stability of complex network infrastructures is paramount. To this end, Augmented Reality (AR) applications on wearable devices like smart glasses are emerging as a key technology to empower field technicians with real-time guidance [1]. These applications rely on multimodal deep neural networks (DNNs) to fuse diverse data streams such as video, audio, and text [2]. However, deploying such models faces severe real-world constraints: terminal devices operate with limited computational capacity and constrained battery budgets, while network conditions exhibit significant heterogeneity in industrial environments. Traditional deployment strategies fail to address these challenges effectively. Full on-device execution leads to unacceptable latency and rapid energy depletion, while complete cloud offloading incurs prohibitive transmission delays unsuitable for time-sensitive on-site tasks [3,4]. Consequently, the Cloud-Edge-End collaborative inference architecture has emerged to resolve this conflict [5]. By partitioning a single DNN model and distributing its execution across the terminal, edge, and cloud tiers, this approach can theoretically balance latency, energy, and computational load [6,7]. Recent surveys on edge AI partitioning have systematically reviewed various splitting strategies, ranging from layer-wise partitioning for sequential CNNs to more sophisticated graph-based methods for complex DAG architectures, while highlighting the critical need for joint optimization of multiple objectives in heterogeneous environments [8,9].

Despite the promise of this architecture, determining the optimal partitioning strategy remains a complex optimization problem. An effective solution must identify a deployment plan that co-optimizes for inference latency and terminal energy consumption. Meanwhile, the functional integrity of its components is especially critical for multimodal models, where disrupting fusion blocks can degrade accuracy [10].

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a Cloud-Edge-End collaborative inference framework driven by a novel Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for DNN Partitioning (HGA-DP). Our approach first represents the multimodal model as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) of semantically coherent subgraphs to preserve functional integrity. The HGA-DP then efficiently navigates the vast search space of deployment strategies using two key innovations: a hybrid search mechanism that integrates global and local exploration to accelerate convergence, and a constraint-aware repair operator that ensures the validity of all generated partitioning solutions.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- We design an automated Cloud-Edge-End collaborative inference framework that intelligently partitions complex multimodal DNNs to co-optimize for inference latency and terminal energy consumption.

- We propose a novel Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for DNN Partitioning (HGA-DP), featuring a unique hybrid search strategy and a constraint-aware repair mechanism to efficiently find near-optimal solutions for this NP-hard problem.

- We construct a simulation platform covering cloud, edge, and terminal nodes with heterogeneous computational capabilities (40–600 GFLOPs at terminal, 10 TFLOPs at edge, and 100 TFLOPs at cloud) and realistic network bandwidths (300 Mbps to 1 Gbps) to evaluate that our framework achieves significant performance gains in both latency and energy, validating its practical effectiveness.

This research provides new insights and engineering methodologies for real-time DNN inference tasks in heterogeneous environments and offers a practical foundation for future work in intelligent, collaborative, and resource-aware deployment strategies for complex multimodal models.

2. Related Work

2.1. Cloud-Edge-End Collaborative Inference for DNNs

Deploying increasingly complex deep neural networks (DNNs), particularly large-scale multimodal models, on resource-constrained end devices presents a fundamental conflict between model performance and system constraints such as latency and energy consumption. To resolve this conflict, the Cloud-Edge-End collaborative inference architecture has emerged as a dominant paradigm [11,12]. This hierarchical approach strategically distributes the computational workload by leveraging the distinct and complementary capabilities of each tier: the virtually unlimited resources of the cloud for heavy, non-time-sensitive computations; the low-latency processing power of edge servers for intermediate, time-critical tasks; and the immediate data access and local processing capabilities of end devices for lightweight preprocessing or executing initial model layers [13,14].

Pioneering frameworks have firmly established the efficacy of this collaborative model. For instance, DDNN [15] demonstrated how model segments could be dynamically distributed across a cluster of devices to minimize execution time, while systems like DeepThings [16] and EdgePipe [17] highlighted the crucial role of the edge in creating efficient, privacy-aware, and high-throughput inference pipelines. These foundational works collectively affirm that distributing a single DNN across the network is a viable and effective strategy for overcoming the limitations of standalone devices.

The success of any collaborative inference system, however, is not determined by the architecture alone, but by the intelligence of its workload distribution strategy [18,19]. The core research challenge thus shifts from if a model should be distributed to how it should be optimally split to balance the trade-offs between computation and communication [12,20]. An influential early work, Neurosurgeon [21], which automatically partitioned a DNN between a mobile device and the cloud, laid the critical groundwork for this field. Consequently, the design of advanced and automated partitioning algorithms, often leveraging machine learning and dynamic adaptation, remains a primary focus of research in this domain [22,23,24].

2.2. DNN Model Partitioning for Computation Offloading

In Cloud-Edge-End collaborative systems, computation offloading is the overarching strategy for shifting intensive workloads from constrained devices to more powerful remote nodes [18]. For modern AI applications, this strategy is primarily realized through DNN model partitioning, a technique that splits a neural network into segments for distributed execution across the Cloud-Edge-End hierarchy [20]. The central goal is to find optimal partition points that minimize end-to-end latency and device energy consumption by intelligently balancing local computation with data communication costs.

As research progressed, partitioning strategies evolved to address two major complexities: increasingly sophisticated model architectures and dynamic runtime environments.

Modern DNNs are often structured as complex Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) rather than simple sequential chains. To tackle this, researchers developed advanced algorithms to navigate the vast solution space. Some approaches rely on specialized graph-based heuristics, like those in DADS [25] and QDMP [26], to accelerate the search process for real-time inference. For multi-device scenarios, algorithms were designed to minimize bottleneck latency in edge clusters by jointly optimizing partition and placement decisions [27]. One major branch of work employs search-based metaheuristics, such as Genetic Algorithms, to find high-quality static partition plans offline [28]. However, existing GA-based partitioners predominantly target layer-wise splitting for sequential CNNs and lack semantic-aware mechanisms to preserve the functional integrity of complex fusion blocks in multimodal architectures, often resulting in accuracy degradation when attention or cross-modal interaction modules are disrupted.

To adapt to fluctuating network bandwidth and resource availability, the focus shifted from static, offline optimization to dynamic, automated decision-making. Here, machine learning, particularly reinforcement learning (RL), became a key enabler. Unlike search-based methods that find a single fixed plan, RL-based frameworks like Auto-Split [22], EdgeML [23], and others [24] train agents to learn adaptive partitioning policies. These policies can respond to real-time system conditions, jointly optimizing for latency, accuracy, and resource usage in dynamic environments [29]. While these adaptive approaches excel at handling runtime variability, they incur non-trivial profiling overhead and typically operate on pre-defined partition candidates rather than solving the structural partitioning problem from scratch, making them complementary to rather than replacements for offline optimization frameworks.

However, despite these advancements, existing model partitioning techniques face significant and unique challenges when applied to multimodal DNNs. These models introduce a new layer of complexity that current methods are ill-equipped to handle.

Multimodal architectures feature specialized branches for different data types (e.g., vision, text) that converge at one or more fusion layers. These fusion points create tight structural dependencies, severely constraining where partitions can be placed without disrupting critical inter-modal alignments [30]. Arbitrary partitioning can break semantic integrity and degrade model accuracy.

The data streams for different modalities vary dramatically in size and characteristics. This heterogeneity means that cost models based on simple data volume are no longer sufficient, requiring a more nuanced, modality-aware approach to balancing computation and communication [31,32]. Moreover, most existing partitioning solutions focus solely on latency optimization and neglect energy consumption at terminal devices, failing to address the critical battery constraints of wearable AR systems where prolonged operation is essential.

In summary, while model partitioning is a mature field for unimodal models, directly applying these established algorithms to multimodal networks is often suboptimal or even detrimental. This highlights a critical research gap: the need for structurally aware and modality-aware partitioning strategies designed explicitly for the unique topologies and data characteristics of multimodal deep learning.

3. System Model and Problem Formulation

3.1. System Architecture

To deploy large-scale multimodal models, we adopt a standard three-tier Terminal-Edge-Cloud architecture. This hierarchical paradigm creates a flexible execution environment by distributing computation across tiers with distinct characteristics:

- Terminal Device: The end-user device (e.g., AR glasses), offering less processing latency but severely constrained by computational power and a finite energy budget.

- Edge Server: An intermediate computing node geographically close to the terminal, providing moderate computational resources.

- Cloud Server: A centralized data center with virtually unlimited computational resources, but subject to significant communication latency due to its remote location.

This three-tier system creates a flexible execution environment where a multimodal model can be partitioned and its computational segments can be strategically placed across the tiers to optimize for specific performance goals.

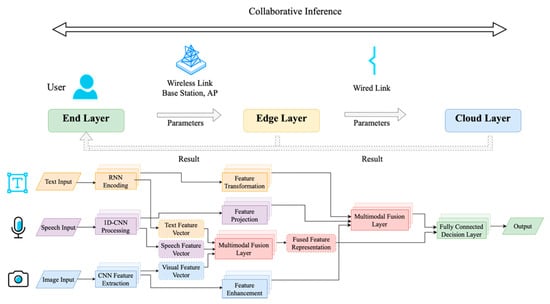

The overall conceptual framework is illustrated in Figure 1, which depicts a representative multimodal inference workflow distributed across the Terminal-Edge-Cloud continuum. In this example, the Terminal is responsible for initial data ingestion (e.g., text, speech, image) and lightweight feature extraction. This stage transforms raw, high-volume data into compact feature vectors. These vectors are then offloaded to the Edge, which handles more complex intermediate processing, such as feature transformation and initial multimodal fusion, leveraging its balanced profile of moderate computation and low latency. Finally, the Cloud utilizes its substantial resources to perform the most computationally demanding final fusion and decision-making tasks to produce the final output.

Figure 1.

Multimodal inference workflow in Cloud-Edge-End architecture.

This illustrative partitioning demonstrates the core principle of our approach: strategically mapping functional segments of a multimodal model to the most appropriate computational tier based on their resource requirements and data dependencies. This structured, hierarchical system provides the essential physical backbone for our optimization problem. To solve it, we next formalize the application model itself and define the performance metrics used to evaluate different partitioning schemes.

3.2. Application Model as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)

While simple neural networks can be conceptualized as a linear sequence of layers, this representation is insufficient for modern multimodal models. These architectures feature complex, non-linear topologies with parallel processing branches and intricate fusion points. To accurately capture these data dependencies and computational structures, we model the multimodal application as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG).

For multimodal models, the initial stages typically consist of multiple parallel branches, where each path is a dedicated encoder for a specific modality, such as a CNN for images or a Transformer for speech. These parallel branches subsequently converge at one or more complex fusion stages, which implement sophisticated mechanisms like cross-modal attention, tensor concatenation, or gating. This convergence creates intricate inter-dependencies between modalities, resulting in a non-linear graph structure that cannot be captured by a simple linear model.

To accurately capture these data dependencies and computational flows, we model the multimodal application as a DAG, denoted by . In this representation, is the set of nodes, with each vertex representing a fundamental computational operator in the model. is the set of directed edges, where an edge represents a data dependency. It signifies that the output tensor of operator serves as an input to operator . This initial, fine-grained DAG is automatically generated by tracing the model’s forward pass using tools like torch.fx, and each node is profiled to obtain its precise computation cost (FLOPs) and communication cost (output data size).

This DAG-based formalization provides a comprehensive and flexible foundation for our partitioning problem. It allows us to reason about arbitrary model structures and accurately model the trade-offs between local computation and remote communication, which is the cornerstone of the optimization framework presented in Section 3.3.

3.3. Model Partitioning Scheme

A fine-grained DAG representing a state-of-the-art multimodal model can contain hundreds or even thousands of nodes. Treating each individual operation as an independent unit for partitioning creates an exponentially large search space, making the optimization problem computationally intractable. More importantly, partitioning at such a low level can break apart functionally cohesive modules, leading to inefficient communication patterns where large intermediate tensors are unnecessarily transmitted between devices.

To address this challenge, we introduce a structured, two-stage partitioning approach based on functional subgraphs. Instead of operating on individual layers, we group nodes in the DAG into meaningful and structurally cohesive blocks, guided by the model’s semantic architecture. This transforms the problem from partitioning a complex graph of micro-operations to scheduling a simpler graph of macro-modules.

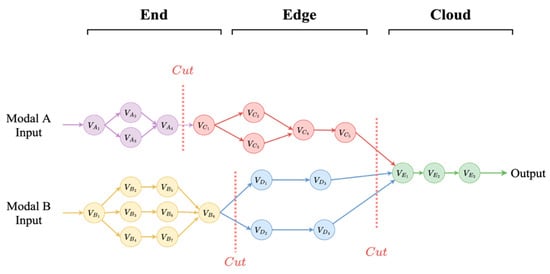

This process effectively transforms the original fine-grained DAG, , into a coarse-grained Grouped Directed Acyclic Graph (GDAG), denoted as . In this GDAG, each node in represents an entire functional subgraph (e.g., a complete language layer or cross-modal attention block), and each edge in represents the data dependencies between these subgraphs, as illustrated in Figure 2. The transformation is automated: nodes in the fine-grained DAG are algorithmically grouped based on their parent module in the model’s hierarchy. The aggregated computation cost of a GDAG node is the sum of its constituent nodes’ costs, while its communication cost is the sum of all data transfers that cross the group’s boundary.

Figure 2.

GDAG-based partitioning of the model DAG.

Crucially, this grouping is performed with an awareness of the model’s multimodal semantics. Key fusion layers, such as the cross-modal attention blocks, are intentionally grouped into single, indivisible subgraphs. This ensures that these semantically critical operations are never split across devices, which could otherwise introduce prohibitive communication overhead or even disrupt the model’s functional integrity. By encapsulating these fusion semantics within the nodes of the GDAG, we transform the problem into one where the algorithm can operate on these macro-blocks, thereby simplifying the optimization while preserving model correctness.

This GDAG representation strikes an optimal balance between structural fidelity and optimization tractability. It preserves the essential dataflow and functional semantics of the multimodal model while significantly reducing the dimensionality of the partitioning problem. This subgraph-based model forms the basis for our problem formulation, allowing us to define latency and energy costs at a modular level, as detailed in the following section.

3.4. Performance Models

With the application model as a Grouped Directed Acyclic Graph (GDAG), , and a deployment strategy defined by the mapping function , we formulate the performance models for latency and energy consumption. These models are essential for evaluating the quality of any given deployment strategy .

To formally model our system, we quantify the performance of each tier using key parameters, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Table of parameters of different platform.

We define the computational capability of tier as (in FLOPs/s) and the data transfer rate between tiers and by the inter-tier bandwidth . Critically, to address the constraints of mobile devices, we model the terminal’s energy cost of local processing as (in nJ/FLOP). This quantitative framework is the foundation upon which we build the latency and energy models for our optimization problem.

3.4.1. Inference Latency

The end-to-end inference latency is the total time elapsed from when the input data is provided to the first subgraph until the final output is produced by the last subgraph. In a system with parallel execution paths, this is not a simple sum of all processing times. Instead, the latency is determined by the critical path of the GDAG—the longest path of dependent computation and communication delays from a source node to a sink node.

To calculate this, we first define the latency components for individual subgraphs and the data transfers between them.

- Computation Latency of a Subgraph

The computation latency of a single subgraph is the time it takes to execute its operations on its assigned computing tier. This depends on the subgraph’s computational workload and the processing power of the target device.

Let be the total computational workload of subgraph , measured in Floating Point Operations (FLOPs). Let be the computing tier (Device, Edge, or Cloud) where subgraph is deployed, according to the deployment strategy . The computation latency for subgraph is then given by:

- 2.

- Communication Latency between Subgraphs

Communication latency occurs when the output of one subgraph must be transmitted to a successor subgraph located on a different computing tier. For a directed edge in , which represents a data dependency from subgraph to : If both subgraphs are on the same device, the communication latency is considered negligible as it involves local memory access. If they are on different devices, a network transfer is required.

Let be the size of the output data (tensor) from subgraph measured in bytes, determined by the tensor’s dimensions and data type. Let denotes the available bandwidth between tiers and , measured in bytes per second. The communication latency for edge is:

- 3.

- Critical Path Latency Calculation

The total end-to-end latency, , is the finish time of the final subgraph in the GDAG. We can calculate this by traversing the graph topologically. Let be the time at which subgraph completes its execution. This time is determined by when all its prerequisite data has arrived, plus its own computation time.

For any subgraph , its finish time is calculated recursively:

where is the set of all immediate predecessor subgraphs of . For source subgraphs (those with no predecessors), the ‘max’ term is 0.

The final end-to-end latency for the entire model under deployment strategy is the maximum finish time among all sink subgraphs (those with no successors):

where is the set of all sink nodes in the GDAG. This critical path-based model provides an accurate estimation of the end-to-end latency, correctly accounting for parallel processing branches and communication bottlenecks inherent in the distributed execution of the multimodal model.

3.4.2. Terminal Energy Consumption

We model the terminal energy consumption, , as the energy consumed exclusively by the computation performed on the device. This cost is directly proportional to the total number of floating-point operations (FLOPs) executed locally.

As defined in Table 1, the energy cost per FLOP on the terminal is denoted by (in nJ/FLOP). The energy consumption of the end device for a given deployment strategy is calculated by summing the computational costs of all subgraphs assigned to the device:

With the models for both latency and energy consumption now established, we have the foundation to formally define our optimization problem.

3.5. Problem Formulation

Having established the performance models, we now formally define the deployment optimization problem. The goal is to find an optimal partitioning strategy, , that maps the application’s subgraphs across the Device-Edge-Cloud continuum to minimize a weighted sum of latency and energy consumption.

Our objective is to minimize a unified cost function that balances end-to-end latency and terminal energy consumption . We use a weighted sum of normalized metrics, where and are user-defined weights (). Normalization is performed against baseline values (, ) derived from an all-terminal deployment. The optimization problem is thus:

This optimization is subject to a critical data flow directionality constraint: data can only be transferred forward through the hierarchy (from Device to Edge to Cloud), prohibiting backward communication to ensure efficiency. This constraint, combined with the task of assigning subgraphs to 3 tiers, creates an NP-hard combinatorial problem with a search space of . An exhaustive search is computationally infeasible. Therefore, to navigate this large and constrained search space effectively, we propose a Genetic Algorithm (GA) to find a high-quality, near-optimal deployment strategy .

4. A Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for DNN Partitioning

To address the problem of partitioning multimodal DNNs across a Cloud-Edge-End architecture, this chapter details our proposed Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for DNN Partitioning (HGA-DP). We will first elaborate on the core components of the algorithm. Finally, we will integrate these components to present the complete algorithmic framework.

4.1. Chromosome Design and Fitness Function

To apply the genetic algorithm to the DNN partitioning problem, we first define the solution encoding. A deployment strategy is represented by a chromosome, an integer vector of length , where is the total number of subgraphs in the model:

Each element , or gene, represents the deployment decision for the -th subgraph. The value of is an integer from the set of available deployment tiers , corresponding to the Terminal, Edge, and Cloud, respectively. The algorithm’s population is initialized by creating such chromosomes, each with genes randomly assigned a tier from .

The quality of each chromosome is quantified by a fitness function, which consolidates the two conflicting objectives: end-to-end latency and terminal energy consumption. The evaluation begins by calculating the two raw performance metrics for a given solution : total latency and terminal energy .

To combine these metrics, which differ in units and magnitude, they are first normalized using baseline values ( and ) derived from a reference ‘All-Terminal’ deployment. The final fitness score, , is defined as the reciprocal of a weighted cost function, ensuring that lower-cost solutions yield higher fitness:

Here, and are user-defined weights satisfying , balancing the importance of latency and energy. is a small positive constant to prevent division by zero.

4.2. Evolutionary Operators

The evolutionary process is driven by selection, crossover, and a specialized mutation operator.

We employ Tournament Selection which is used to select individuals for the mating pool. In each round, () individuals are randomly sampled from the current population, and the one with the highest fitness value is selected to enter the mating pool.

Once the mating pool is formed, the crossover operator is applied to generate new offspring from the selected parents. Given two parent chromosomes, and , a random integer crossover point is selected. Two new offspring, and , are generated as follows:

The crossover operation employs a single-point strategy, where a random cut position divides each parent chromosome into two segments. This preserves contiguous deployment decisions for adjacent subgraphs, maintaining structural locality in the partitioning scheme.

To complete the generation of new solutions, the offspring are subjected to mutation. This step is crucial for balancing exploration and exploitation. We implement a Dynamic Mutation Rate to achieve this balance. The per-gene mutation probability, , decreases linearly with the generation number from an initial rate to a final rate over tal generations. The rate for generation is calculated as:

where . When triggered by the dynamic rate, each gene is randomly reassigned to one of the three tiers {0, 1, 2} with uniform probability. This strategy encourages broad exploration in early stages and promotes fine-tuning of solutions as the algorithm converges.

4.3. Constraint-Aware Repair Mechanism

Standard genetic operators are oblivious to the problem’s hierarchical data-flow constraints, frequently generating invalid offspring. To enforce feasibility, we introduce a mandatory and deterministic Constraint-Aware Repair Mechanism.

A chromosome is considered valid if the deployment tier for any subgraph is at least as high as the tiers of all its predecessors. Formally, this hierarchical constraint is:

where is the set of predecessors for .

The repair mechanism enforces this property by iterating through the subgraphs in a fixed topological order, which guarantees that all predecessors of a subgraph are valid before it is processed. For each , the mechanism identifies the minimum required level, . If the current assignment violates the constraint (i.e., ), it is elevated to . Otherwise, it remains unchanged.

This process ensures that every chromosome in the population is valid, confining the evolutionary search to the feasible region of the solution space. The detailed logic is presented in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Constraint-Aware Repair Mechanism (Repair_Chromosome) | |

| Input: Chromosome , Subgraph DAG | |

| Output: A valid (repaired) chromosome | |

| 1: | for each subgraph in topological order of do |

| 2: | ← |

| 3: | if then |

| 4: | |

| 5: | end if |

| 6: | end for |

| 7: | return |

4.4. Hybridization with Neighborhood Search

To accelerate convergence and refine solution quality, we enhance the standard GA with a Neighborhood Search (NS). The NS operator is applied once per generation to the current fittest individual, or elite chromosome, . It systematically explores the local solution space by generating a set of “neighbor” solutions. A neighbor is created by modifying a single gene with a level offset , effectively attempting to shift a subgraph’s deployment to an adjacent tier.

The implementation of this local search is detailed in Algorithm 2. The algorithm generates all valid, single-move neighbors from the elite, evaluates them, and returns a list of any neighbors that yield a fitness improvement. These superior solutions are then injected back into the population, replacing weaker individuals. This strategy allows the algorithm to perform a greedy local refinement around promising solutions, improving the convergence speed and the quality of the result.

| Algorithm 2: Neighborhood Search (Neighborhood_Search) | |

| Input: Elite chromosome , Subgraph DAG , Number to inject | |

| Output: List of top improved neighbors | |

| 1: | ← |

| 2: | ← Fitness (, ) |

| 3: | for each gene in do |

| 4: | for each level offset do |

| 5: | ← |

| 6: | new_level ← |

| 7: | if new_level is a valid device level then |

| 8: | ← new_level |

| 9: | ← Repair(, ) |

| 10: | ← Fitness(, ) |

| 11: | if > then |

| 12: | Add (, ) to |

| 13: | end if |

| 14: | end if |

| 15: | end for |

| 16: | end for |

| 17: | Sort in descending order of fitness |

| 18: | ← top unique solutions from |

| 19: | return |

Having detailed the fundamental components of our approach, we now integrate them into a cohesive whole. The overall process, formally outlined in Algorithm 3, begins with generating an initial population and then iteratively refines it through generations of selection, crossover, and mutation. This evolutionary loop is guided by the fitness function, systematically searching the solution space for a deployment strategy that optimally balances latency and energy. Algorithm 3 encapsulates this entire hybrid strategy, providing a step-by-step procedure for finding a near-optimal DNN partitioning solution.

| Algorithm 3: Main Steps of the Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for DNN Partitioning (HGA-DP) | |

| Input: Subgraph DAG , population size , max generations , etc. | |

| Output: The best deployment solution | |

| 1: | // 1. Initialization Phase |

| 2: | ← InitializePopulation(, ) |

| 3: | Evaluate fitness for all individuals in using objective function |

| 4: | ← Fittest individual from |

| 5: | // 2. Evolutionary Loop |

| 6: | for generation = 1 to do |

| 7: | ← Fittest individual in |

| 8: | ← Neighborhood_Search(, , ) |

| 9: | ← ∅ |

| 10: | Add top individuals from to |

| 11: | Add all individuals from to |

| 12: | while do |

| 13: | , ← Tournament_Selection() |

| 14: | ← Crossover(, ) |

| 15: | ← Mutate() |

| 16: | ← Repair(, ) |

| 17: | Add to |

| 18: | end while |

| 19: | ← |

| 20: | Evaluate fitness for all new individuals in |

| 21: | // Update Best-So-Far Solution |

| 22: | end for |

| 23: | return |

5. Results

5.1. Experimental Setup

To rigorously evaluate the performance of our proposed Hybrid Genetic Algorithm (HGA-DP), we established a simulated experimental environment based on a standard multimodal architecture and a well-known benchmark.

- Benchmark Model and Dataset

We utilize LXMERT, a prominent transformer-based model for vision-and-language reasoning. LXMERT’s architecture, which includes separate encoders for visual and language inputs followed by a cross-modal encoder, naturally lends itself to our subgraph-based partitioning approach. For our experiments, the model was profiled and partitioned into 22 functional subgraphs. The computational load (FLOPs) and intermediate data size for each subgraph were pre-calculated to serve as inputs for our performance models. The experiments are conducted using the COCO 2017 dataset, where each inference task consists of an image and a corresponding textual question, simulating a realistic visual question answering (VQA) scenario.

- 2.

- Simulated Environment and Parameters

We simulate a typical three-tier Cloud-Edge-End architecture. A critical aspect of our optimization is the battery life of the end device; therefore, we model the terminal’s energy consumption at 3.0 nJ per FLOP. Energy consumption for the edge and cloud servers is not considered, as they are assumed to have persistent power supplies. The specific parameters for the hardware, network, and the HGA-DP algorithm are consolidated in Table 2. These settings, including the dynamic mutation rate, were chosen to balance exploration and exploitation during the search process.

Table 2.

System and HGA-DP Algorithm Parameters.

Furthermore, the weights for the objective function were set as and . This weighting is deliberately application-driven, prioritizing terminal energy consumption over latency because field technicians rely on wearable devices for extended periods. Our chosen weighting therefore represents a pragmatic balance: it strongly prioritizes the most critical non-functional requirement (energy conservation) without excessively compromising the performance objective (latency), aligning our optimization goals with the practical needs of the target application.

- 3.

- Baseline Methods

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed HGA-DP, we compare its results against three standard baseline deployment strategies:

- All-Terminal: The entire LXMERT model is executed on the terminal device. This strategy yields the lowest possible latency if the device is powerful enough, but at the cost of maximum terminal energy consumption.

- All-Edge: The entire model is offloaded and executed on the edge server. This strategy serves as an intermediate option, offloading computation from the terminal while potentially offering lower network latency than the cloud. Its effectiveness, however, is contingent on the edge server’s processing power and the quality of the local network connection.

- All-Cloud: The model is executed entirely on the cloud server, with only raw data being transmitted from the terminal. This approach minimizes terminal energy consumption but typically results in high end-to-end latency due to network communication overhead.

- DADS (Dynamic Adaptive DNN Surgery): We also benchmark against DADS, a prominent heuristic that models DNN partitioning as a min-cut problem. Its sole objective is to find a partition that minimizes end-to-end latency. As a single-objective algorithm, DADS exclusively focuses on latency and ignores terminal energy consumption, making it a strong latency-centric baseline. We adapt its original two-tier design to our three-tier system using a hierarchical approach.

To quantify the computational cost of our proposed algorithm, we also evaluated its runtime performance. We benchmarked the total execution time of the full HGA-DP against a standard GA and a version enhanced only with our repair mechanism, under identical experimental conditions. This analysis allows us to measure the overhead introduced by the repair and neighborhood search components.

5.2. Results Comparison

We evaluate our proposed algorithm (HGA-DP) by benchmarking it against key baselines and a standard Genetic Algorithm (GA). The evaluation is based on three metrics: total inference latency, terminal energy consumption, and the overall fitness score. To ensure the statistical reliability of our results, each experiment was repeated 10 times with different random seeds. The final reported metrics are the average values from these 10 runs.

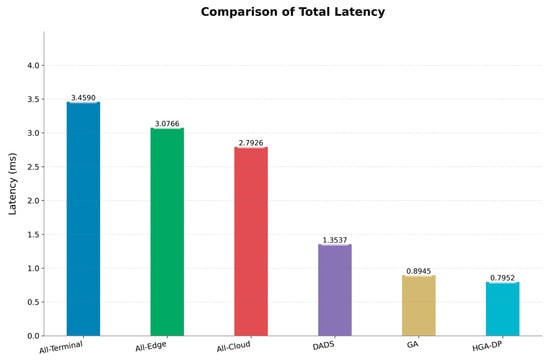

- Total Inference Latency

As shown in Figure 3, deployment strategy significantly impacts total inference latency. The network-intensive All-Cloud (2.79 ms) and All-Edge (3.08 ms) strategies suffer from high communication overhead. Conversely, the All-Terminal strategy (3.46 ms), while free of network delay, is constrained by on-device computation. The DADS heuristic, which focuses on minimizing latency, reduces this to a more competitive 1.35 ms. In contrast, optimization-based methods deliver substantial improvements. A standard GA reduces latency to 0.89 ms, but our HGA-DP sets a new benchmark at just 0.80 ms. This represents an 77% reduction from the All-Terminal baseline and a further 11.1% improvement over the standard GA, showcasing its superior balancing of computation and communication.

Figure 3.

Inference latency comparison across deployment strategies.

- 2.

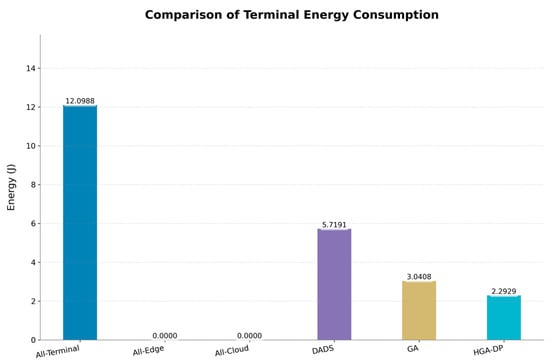

- Terminal Energy Consumption

From the perspective of terminal device sustainability, energy consumption is a critical factor. Figure 4 illustrates that the All-Terminal strategy is the most power-intensive, consuming 12.10 J. While the All-Cloud and All-Edge strategies eliminate terminal computation energy entirely, they do so at the cost of the high latencies shown previously. Notably, the latency-centric DADS approach consumes a considerable 5.72 J, underscoring the trade-off of its single-objective focus. The standard GA offers a reasonable compromise, reducing energy to 3.04 J. Our HGA-DP excels further, lowering the terminal energy consumption to only 2.29 J.

Figure 4.

Terminal energy consumption comparison.

This is an 81.1% reduction compared to the All-Terminal baseline and a 24.6% improvement over the standard GA. This result validates HGA-DP’s effectiveness in offloading high-compute modules to more powerful tiers, significantly extending the battery life of energy-constrained devices.

- 3.

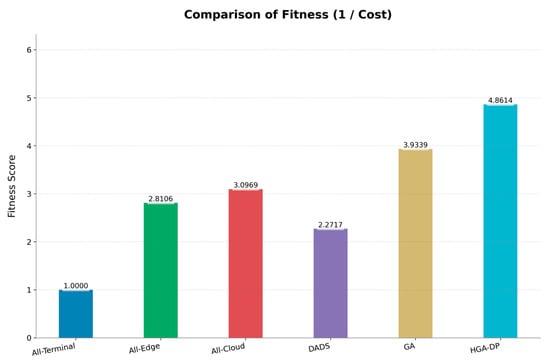

- Overall Fitness and Global Optimality

To assess the overall quality of the deployment solutions, we use a fitness function that unifies latency and energy into a single objective (where higher is better). As shown in Figure 5, the baseline strategies demonstrate the value of optimization.

Figure 5.

Fitness comparison across deployment strategies.

While the All-Terminal strategy is normalized to a fitness of 1.0, the full-offloading strategies (All-Edge and All-Cloud) achieve better scores of 2.81 and 3.10, respectively. DADS performs similarly with a fitness of 2.27, highlighting that optimizing for latency alone does not yield a globally optimal solution. The standard GA improves the solution quality significantly, achieving a fitness of 3.93. Crucially, our HGA-DP reaches a fitness score of 4.86, which is approximately 1.24 times higher than the standard GA and nearly 4.9 times better than the All-Terminal baseline. This demonstrates that HGA-DP does not merely optimize for a single metric but discovers a globally superior partitioning strategy that harmonizes the competing demands of performance and energy efficiency.

- 4.

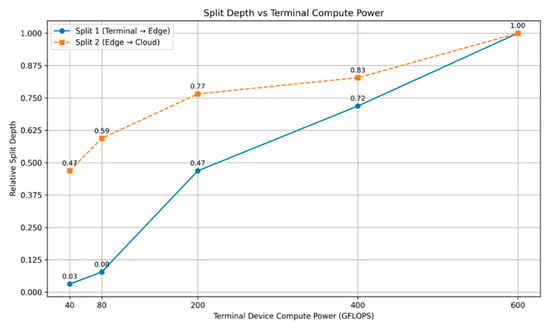

- Impact of Terminal Capability

To further investigate the adaptability of our proposed HGA-DP algorithm, we conducted a sensitivity analysis on the impact of the terminal device’s computational capability. We varied the terminal’s power from a low-end 40 GFLOPS to a more capable 600 GFLOPS to observe how the algorithm adjusts the optimal partition points. The results, visualized in Figure 6 clearly demonstrate the algorithm’s adaptive partitioning strategy.

Figure 6.

Split depth vs. terminal compute power.

In this analysis, we held the edge and cloud resources constant while only varying the terminal’s power. For each power configuration, we ran the HGA-DP algorithm to find the optimal partitioning scheme and recorded the locations of the two primary split points: from Terminal to Edge (Split 1) and from Edge to Cloud (Split 2). The y-axis in the figure, “Relative Split Depth,” is a normalized metric that quantifies the cumulative fraction of the model’s total FLOPs executed before the split. A depth of 0.0 represents the model’s input layer, while 1.0 represents its final output layer.

The analysis of Figure 6 reveals our algorithm’s clear adaptive behavior. For capacity-constrained terminals, HGA-DP adopts an aggressive offloading strategy, placing the split point (Split 1) very early in the model’s computational graph (depth ≈ 0.03–0.09) to avoid creating a local bottleneck. As the terminal’s capacity grows, the algorithm intelligently pushes this split point progressively deeper, retaining a larger portion of the model for local execution. This shift demonstrates a sophisticated trade-off, leveraging increased local compute power to reduce latency-inducing communication overhead.

- 5.

- Algorithm Efficiency

In addition to performance gains, we analyzed the computational overhead of our HGA-DP. Table 3 presents the runtime comparison.

Table 3.

Algorithm Runtime Overhead Analysis.

The results indicate that the repair mechanism adds a minimal overhead of approximately 2.9%, while the neighborhood search, the primary driver of solution quality, increases the total overhead to 24.4%. This moderate increase is a justifiable trade-off for a one-time, offline optimization process, as it leads to a superior deployment strategy that yields significant long-term performance benefits in latency and energy during online inference.

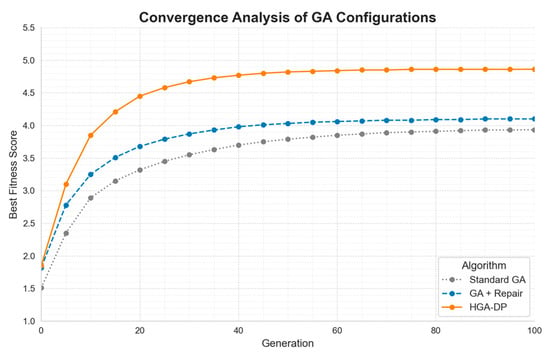

To provide a more comprehensive view of algorithm efficiency, we also analyzed the convergence behavior, as shown in Figure 7. The graph clearly demonstrates that the additional operations in HGA-DP, which incur a modest runtime overhead (Table 3), are a highly effective investment. While the baseline GA stagnates at a suboptimal level, our HGA-DP not only converges significantly faster but also achieves a superior final fitness score. This rapid convergence to a high-quality solution directly justifies the computational cost, affirming that the extra operations are crucial for escaping local optima and discovering a better deployment strategy.

Figure 7.

Convergence analysis of different GA configurations.

6. Conclusions

This research addresses the critical challenge of deploying complex multimodal models for AR-assisted communication maintenance, where real-time performance on resource-constrained devices like smart glasses is paramount. By abstracting the model into a Grouped Directed Acyclic Graph (GDAG), we established a formal foundation that accurately captures the intricate data dependencies of modern neural architectures, enabling a structured approach to the partitioning problem.

The core contribution of this work is a novel Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for DNN Partitioning (HGA-DP), designed specifically to navigate the NP-hard solution space of this problem. Our algorithm introduces two key innovations: a constraint-aware repair mechanism that ensures all generated partitions are valid by respecting data dependencies and a hybridization with local search that balances global exploration with local refinement. This dual approach allows the algorithm to efficiently escape local optima and discover superior deployment configurations that co-optimize for both latency and energy.

While simulation results demonstrate substantial performance improvements, we acknowledge several limitations that guide our future work. The primary next step is validating our framework on a physical hardware testbed to assess its real-world efficacy. Furthermore, we plan to extend our evaluation to a broader range of multimodal architectures to confirm the generalizability of our approach. Finally, addressing privacy concerns by integrating privacy-preserving techniques is another important direction for deploying such systems in sensitive industrial settings.

In summary, this work delivers a practical and automated framework to make advanced, real-time multimodal AI feasible on edge devices. By combining a system model with a sophisticated, problem-aware hybrid genetic algorithm, our solution effectively navigates the complex trade-offs between latency and energy. This research lays a practical foundation for intelligent, collaborative, and resource-aware deployment strategies, and future work will build upon this by extending to dynamic runtime adaptation under varying network conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y. and X.L.; methodology, R.Z.; software, X.L. and J.W.; validation, R.Z., X.L. and W.D.; formal analysis, R.Z.; investigation, C.Y.; resources, C.Y. and S.S.; data curation, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z. and C.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.S.; visualization, W.D. and J.W.; supervision, C.Y. and S.S.; project administration, C.Y. and J.W.; funding acquisition, C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ningxia Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 2023AAC03846.

Data Availability Statement

The experimental data supporting the findings of this study were generated through simulations based on the LXMERT model architecture and the publicly available COCO 2017 dataset (https://cocodataset.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2024)). The model profiling data, including computational workloads (FLOPs) and intermediate tensor sizes for each subgraph partition, were derived from the open-source LXMERT implementation. The simulation parameters and configurations used in this study are fully detailed in Section 5.1 of the manuscript. The code implementing the proposed HGA-DP algorithm and the simulation framework will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Cong Ye, Xiao Li, Wenlong Deng, and Jianlei Wang were employed by the company Information & Communication Company of State Grid Ningxia Electric Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Siriwardhana, Y.; Porambage, P.; Liyanage, M.; Ylianttila, M. A Survey on Mobile Augmented Reality with 5G Mobile Edge Computing: Architectures, Applications, and Technical Aspects. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1160–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. Deep Multimodal Representation Learning: A Survey. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 63373–63394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, D.; Jeong, M.; Lee, M. Investigation on performance and energy efficiency of CNN-based object detection on embedded device. In Proceedings of the 2017 4th International Conference on Computer Applications and Information Processing Technology (CAIPT), Bali, Indonesia, 8–10 August 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando, N.; Loke, S.W.; Rahayu, W. Mobile cloud computing: A survey. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2013, 29, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Lan, S.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y. End-Edge-Cloud Collaborative Computing for Deep Learning: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 26, 2647–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, B.; Yahya, W.; Lin, Y.-D.; Ali, A. A Survey on Offloading in Federated Cloud-Edge-Fog Systems with Traditional Optimization and Machine Learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.10628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Wang, X.; Zeng, R.; Li, Y.; Shi, J.; Huang, M. Joint optimization of multi-dimensional resource allocation and task offloading for QoE enhancement in Cloud-Edge-End collaboration. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 155, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, D.; Zhou, Y.; Hao, Y.; Hu, L.; Mo, Y.; Chen, M.; Humar, I. Multi-modal model partition strategy for end-edge collaborative inference. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2026, 208, 105189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhou, M.-T.; Ren, T.-F.; Jiang, C.-B.; Chen, Y. Partitioning multi-layer edge network for neural network collaborative computing. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2023, 2023, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-F.; Zhai, J.-H.; Xie, B.-J.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, X. Multimodal Representation Learning: Advances, Trends and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics (ICMLC), Kobe, Japan, 7–10 July 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Dai, F.; Xu, X.; Fu, X.; Dou, W.; Kumar, N.; Bilal, M. An adaptive DNN inference acceleration framework with end–edge–cloud collaborative computing. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 140, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeik, F.; Avgeris, M.; Spatharakis, D.; Santi, N.; Dechouniotis, D.; Violos, J.; Leivadeas, A.; Athanasopoulos, N.; Mitton, N.; Papavassiliou, S. Task offloading in Edge and Cloud Computing: A survey on mathematical, artificial intelligence and control theory solutions. Comput. Netw. 2021, 195, 108177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Dong, N.; Li, W.; Cao, J. Edge Computing with Artificial Intelligence: A Machine Learning Perspective. ACM Comput Surv 2023, 55, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T. Cloud-Based or On-Device: An Empirical Study of Mobile Deep Inference. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Engineering (IC2E), Orlando, FL, USA, 17–20 April 2018; pp. 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teerapittayanon, S.; McDanel, B.; Kung, H.T. Distributed Deep Neural Networks Over the Cloud, the Edge and End Devices. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 37th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Atlanta, GA, USA, 5–8 June 2017; pp. 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Barijough, K.M.; Gerstlauer, A. DeepThings: Distributed Adaptive Deep Learning Inference on Resource-Constrained IoT Edge Clusters. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2018, 37, 2348–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Dong, C.; Wen, W. Enable Pipeline Processing of DNN Co-inference Tasks in the Mobile-Edge Cloud. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 6th International Conference on Computer and Communication Systems (ICCCS), Chengdu, China, 23–26 April 2021; pp. 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, B.; Yahya, W.; Lin, Y.-D.; Ali, A. Offloading Using Traditional Optimization and Machine Learning in Federated Cloud–Edge–Fog Systems: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.; Tran, T.X.; Pompili, D. Energy-Latency-Aware Task Offloading and Approximate Computing at the Mobile Edge. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 16th International Conference on Mobile Ad Hoc and Sensor Systems (MASS), Monterey, CA, USA, 4–7 November 2019; pp. 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, J.; Zhang, H.; Lian, J.; Zhang, B. Partitioning DNNs for Optimizing Distributed Inference Performance on Cooperative Edge Devices: A Genetic Algorithm Approach. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Hauswald, J.; Gao, C.; Rovinski, A.; Mudge, T.; Mars, J.; Tang, L. Neurosurgeon: Collaborative Intelligence Between the Cloud and Mobile Edge. ACM SIGARCH Comput. Archit. News 2017, 45, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banitalebi-Dehkordi, A.; Vedula, N.; Pei, J.; Xia, F.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Auto-Split: A General Framework of Collaborative Edge-Cloud AI. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.13041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, K.; Ling, N.; Xing, G. EdgeML: An AutoML Framework for Real-Time Deep Learning on the Edge. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Internet-of-Things Design and Implementation, Nashville, TN, USA, 18–21 May 2021; ACM: Charlottesvle, VA, USA, 2021; pp. 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, X.; Fan, Q.; He, Q.; Wang, X.; Leung, V.C.M. Distributed DNN Inference with Fine-Grained Model Partitioning in Mobile Edge Computing Networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 9060–9074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Bao, W.; Wang, D.; Liu, F. Dynamic Adaptive DNN Surgery for Inference Acceleration on the Edge. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2019-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, Paris, France, 29 April–2 May 2019; pp. 1423–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Ding, B.; Wu, D. Towards Real-time Cooperative Deep Inference over the Cloud and Edge End Devices. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2020, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, A.; Krishnamachari, B. Partitioning and Placement of Deep Neural Networks on Distributed Edge Devices to Maximize Inference Throughput. In Proceedings of the 2022 32nd International Telecommunication Networks and Applications Conference (ITNAC), Wellington, New Zealand, 30 November–2 December 2022; pp. 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sada, A.B.; Khelloufi, A.; Naouri, A.; Ning, H.; Dhelim, S. Selective Task offloading for Maximum Inference Accuracy and Energy efficient Real-Time IoT Sensing Systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.16904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Kou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y. Real-Time Adaptive Partition and Resource Allocation for Multi-User End-Cloud Inference Collaboration in Mobile Environment. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 13076–13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudala, T.; Tsouvalas, V.; Meratnia, N. Fine-tuning Multimodal Transformers on Edge: A Parallel Split Learning Approach. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.06355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardellitti, S.; Scutari, G.; Barbarossa, S. Joint Optimization of Radio and Computational Resources for Multicell Mobile-Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Signal Inf. Process. Netw. 2015, 1, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Zheng, J.; Gao, L.; Niu, J.; Ren, J.; Wang, H.; Cao, R.; Ji, S. Generative AI-Aided Multimodal Parallel Offloading for AIGC Metaverse Service in IoT Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 13273–13285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).