Abstract

This article reviews the state of the art, implementation barriers, and emerging trends in industrial digitalization, drawing on studies published between 2020 and July 2025. It analyzes how classical Industry 4.0 technologies, simulation and modeling, and Industry 5.0 priorities are transforming production processes in smart factories, yielding higher productivity, reduced downtime, and improved quality. At the same time, the literature documents persistent obstacles, including system integration and interoperability, security and data-privacy risk, and financial constraints, especially for SMEs. Looking ahead, future directions point to a gradual shift towards sustainable intelligent manufacturing with human–robot collaboration and data-centric operations. In addition, the article proposes and validates a conceptual framework for the digitalization of manufacturing companies and provides practical recommendations for stakeholders seeking to leverage digital technologies for operational excellence and sustainable value creation.

1. Introduction

In recent years, manufacturing industries have accelerated digital transformation by adopting technologies associated with the Industry 4.0 paradigm [1]. The Fourth Industrial Revolution integrates cyber–physical systems (CPS), pervasive connectivity, and embedded intelligence across design, shop-floor operations, and in-service use, enabling fully networked smart manufacturing systems [2]. Since 2020, COVID-19 disruptions and intensifying competition have further emphasized the need for remote operations and organizational resilience [3], prompting firms to deploy digital tools not only for productivity and efficiency but also for agility and sustainability.

Many countries have launched strategic initiatives, such as Germany’s Industrie 4.0 and China’s Made in China 2025, to leverage digital technologies for innovation and improved industrial performance [4,5]. At their core is a set of interconnected information technology (IT) capabilities [6]: industrial automation and robotics [7], the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) [8], cloud computing [9], artificial intelligence (AI) [10], and big data analytics [11]. In practice, automated equipment and robots instrumented with IIoT sensors stream real-time data to cloud platforms, where AI and big data models detect anomalies, predict failures, and optimize operations; insights are then fed back for adaptive control, closing the CPS loop. While Industry 4.0 emphasizes autonomy, interoperability, and real-time optimization, the emerging Industry 5.0 paradigm [12] extends the vision by centering human value creation and resilience through advanced human–machine collaboration.

Despite clear benefits, adoption introduces challenges and risks [13], including heightened cybersecurity and safety concerns [14] and tensions with sustainability targets [15]. Other key obstacles include legacy system integration, solution selection amid rapid tool proliferation, limited interoperability standards, fast technology cycles that threaten long-term compatibility, data quality and bias issues in AI, and workforce upskilling needs [16]. Consequently, it is essential to understand not only the individual capabilities of these technologies but also their convergence, integration pathways, and barriers to realizing their full potential.

To support a better understanding of the evolving digital landscape and its challenges, this review sets out two main objectives:

- Synthesize recent research on smart manufacturing ecosystems—state of the art, key challenges, and future directions for Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0, with emphasis on flexibility, adaptability, and scalability.

- Propose and validate a framework that reengineers core business processes across functional areas in industrial companies.

The main contributions of this paper include:

- A systematic literature review of manufacturing digitalization technologies and tools from the perspectives of evolutionary development and application needs;

- An integrated mechanism for implementation and for assessing capabilities and improvement potential across manufacturing processes;

- Actionable guidance for planning and evaluating investments in Industry 4.0 and related digital technologies, including applicability to SMEs.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 details the research methodology, including database selection and analytical methods for processing. Section 3 synthesizes prior reviews on innovative digitalization technologies identifying unresolved questions. Section 4 presents a thematic review of research articles drawn from our corpus, highlighting publication trends and the evolution of core themes. Section 5 introduces a systematic framework for industrial digitalization and demonstrates its applicability and effectiveness through a proof-of-concept deployment and a SIRI-based maturity assessment. Section 6 analyzes key challenges and emerging opportunities for manufacturing digitalization, with attention to flexibility, adaptability, and scalability in the contexts of Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0. The last section concludes by summarizing the main findings, outlining implications for theory and practice, offering guidance for stakeholders, and proposing directions for future research.

2. Research Methodology

The methodological process was designed to capture recent and impactful research on digital transformation in industrial companies, with emphasis on key technological enablers. The study followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [17], a widely recognized protocol for structured literature reviews in technical domains (Supplementary Materials).

To capture the core technologies underpinning contemporary smart manufacturing, we focused on English-language, peer-reviewed journal articles and review papers published from 2020 through to the search date. This window prioritized the field’s rapid evolution and the most recent contributions. Consistent with our open-science stance, we applied an open-access filter to ensure full-text availability for analysis. Searches were conducted in two major bibliographic databases—Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall literature review process following PRISMA guidelines. Remarks: All identified documents were screened and assessed for eligibility, after which they were initially classified by digital technologies [6]. The numbers in parentheses indicate the total number of articles, followed by the number of review articles shown as total/reviews for each main classification group.

The database queries returned 4029 records from Scopus and 87 from WoS. To ensure quality and relevance, we retained only articles indexed in both Scopus and WoS, yielding 75 publications. Manual screening then excluded seven records that did not meet full open-science criteria (e.g., institution-restricted access) and seven records whose focus was predominantly economic, managerial, or educational, with insufficient technological analysis. The final dataset comprised 61 articles: 17 review papers providing consolidated insights and thematic syntheses, and 44 original research articles presenting technological developments or empirical findings.

We included peer-reviewed journal articles (Research Article or Review Article) published in English between 2020 and 2025, with open-access full text available, indexed in both Scopus and WoS, situated in industrial or manufacturing contexts. We excluded duplicates; items without open-access; non-journal formats (editorials, letters, notes, conference abstracts); studies outside industrial or manufacturing domains; papers focused solely on economic, organizational, or educational themes without material technological analysis; and records indexed in only one of the two databases.

Beyond PRISMA, the analysis proceeded in three complementary steps that combined bibliometric meta-analysis with qualitative review. First, we computed yearly publication frequencies, fitted linear trend lines for publication counts and author keywords, and conducted a keyword co-occurrence analysis. Second, two researchers independently coded full texts and abstracts, grouped codes into themes, and reconciled discrepancies through discussion to reach consensus on the final topic set without relying on automated topic modeling software. Third, we synthesized these results to propose a systematic framework for industrial digitalization, selecting the most appropriate technologies for key functional activities and work processes. To establish validity, we implemented proof of concept (PoC) and assessed digitalization maturity using a multi-criteria approach.

The methodology both maps the digital transformation landscape and supports the development and empirical validation of the proposed framework, thereby ensuring transparency and reproducibility.

3. Related Work: Review Articles on Industrial Transformation

This section reviews prior review articles from the selected corpus to establish the study’s foundation. Collectively, these works provide a consolidated perspective on industrial digitalization and outline practical applications.

Several reviews are technology-centered, with AI and machine learning (ML) dominating the focus. Çınar et al. [18] review ML for predictive maintenance, identifying supervised methods such as random forests, support vector machines, and neural networks as prevalent, while noting low industrial adoption and advocating hybrid models and cloud-based solutions. Burzyńska [19] examines AI/ML in defect diagnosis within a Quality 4.0 context, highlighting strong model accuracy but significant data-quality and deployment barriers. Gargalo et al. [20] analyze hybrid modeling in (bio)chemical engineering, showing its potential for optimization and sustainability alongside integration and interpretability challenges. Ghosh et al. [21] evaluate AI-driven surface-roughness assessment, noting deep-learning effectiveness but a lack of benchmark datasets and transparency. A distinct cluster of reviews addresses digital-twin (DT) technology and its integration. Onaji et al. [22] present a layered DT framework for manufacturing, emphasizing predictive-maintenance and optimization benefits while noting infrastructure challenges, and Wang et al. [23] highlight DT’s role in improving efficiency and sustainability in the energy sector.

Other reviews focus on integrating digitalization with established operational philosophies. Escobar et al. [24] discuss the transition to Quality 4.0 and recommend AI-enhanced predictive analytics supported by mechanisms for explainability. Benslimane et al. [25] examine the convergence of Lean Manufacturing and Industry 4.0, identifying mutual benefits as well as cultural, technical, and skills-related barriers.

Suuronen et al. [26] adopt strategic and ecosystem perspectives by examining Digital Business Ecosystems (DBEs) and their enabling conditions, benefits, and obstacles. Serey et al. [27] propose a framework that aligns Industry 4.0 adoption with organizational strategy. Voinea et al. [28] map industrial augmented-reality (AR) trends, noting integration with AI and IoT but highlighting cost and usability issues. Salierno et al. [29] compare Europe’s “digital factory” with China’s “cloud manufacturing” and identify interoperability as a shared challenge.

Sector- and connectivity-specific studies include those of Isoko et al. [30], who investigate Industry 4.0 enablers in biopharmaceutical manufacturing and call for standardized integration models, and Qiu et al. [31], who review IIoT adoption and advocate fully integrated architectures combining 5G, cloud, edge AI, and DT. Kamble et al. [32] propose a performance-measurement framework for automotive small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Reyes Domínguez et al. [33] provide bibliometric and cross-technology perspectives by exploring global Industry 4.0 research trends and urging stronger integration of sustainability with emerging technologies, while Wang and Jiao [34] focus on human–automation collaboration using adaptive AI and cognitive modeling.

Several of the 17 reviewed studies outline strategic or conceptual frameworks to guide smart manufacturing under the Industry 4.0 paradigm, each addressing different aspects such as technology integration, performance measurement, strategic alignment, or operational intelligence:

- Strategic alignment frameworks—Serey et al. [27] emphasize that digital transformation in industrial firms must align technological investments with business models, workforce reskilling, and integrated digital ecosystems. Isoko et al. [30] complement this work by proposing an operational roadmap for Bioprocessing 4.0.

- Technical and architectural frameworks—Onaji et al. [22], Wang et al. [23], and Salierno et al. [29] describe layered DT architectures that combine physical systems, data infrastructure, and decision-making analytics. Wang and Jiao [34] propose a framework that merges smart in-process inspection with human–automation symbiosis to support real-time defect identification and adaptive task allocation. Kamble et al. [32] outline and validate a multidimensional smart-manufacturing performance-measurement system for SMEs that links Industry 4.0 investments to outcomes such as flexibility, real-time analytics, and sustainability.

- Integration frameworks—Benslimane et al. [25] and Gargalo et al. [20] present integration frameworks that illustrate the convergence of technologies, such as Lean with Industry 4.0 or hybrid modeling with AI/ML and DT, while highlighting both synergies and structural barriers to adoption.

Despite valuable insights, most reviews examine technologies or strategic actions in isolation. In practice, industrial digital transformation is dynamic, multilayered, and interdependent: IoT data feed AI models, which drive CPS, which in turn inform DT simulations and optimization. The key challenge is to develop cross-technology frameworks that capture these feedback loops and address integration at both technical and organizational levels.

The selected review articles collectively characterize the technological, methodological, and strategic dimensions of industrial digitalization under the Industry 4.0 paradigm. Their scope ranges from technology-specific analyses to sector-focused studies and conceptual frameworks. However, most concentrate on one or two technologies and therefore provide limited cross-technology guidance.

4. Findings from the Literature Sample

4.1. Publication Trends, Keyword Dynamics, and Thematic Evolution

This section analyzes author keywords and their dynamics in a corpus of 61 peer-reviewed articles on industrial digitalization published between 2020 and 31 July 2025 [35]. The dataset shows both the rising prominence of specific concepts and an expanding terminological range. In total, 308 keyword instances were identified. The annual number of publications (light red bars) and the number of unique keywords per year (light green bars) both increase steadily through 2024, indicating sustained growth and thematic diversification in the literature on industrial digitalization (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Annual counts of publications and author keywords for 2020–2025 *. Note: The asterisk (*) indicates that data for 2025 cover only the first half of the year.

In 2020, the corpus contained four publications with 17 keyword instances. By 2024, it reached 23 publications and 111 keyword occurrences, indicating sharp growth in both research output and thematic breadth. Although only five publications from the first half of 2025 were included, they contributed 24 keyword instances, suggesting that the diversity observed in 2024 is likely to persist or increase as the year progresses.

Trend analysis shows a strong linear increase in publications (R2 = 82.9%), rising by approximately 4.1 papers per year, with 2024 notably above the fitted line, indicating acceleration. Author keywords also increase steeply (slope ≈ 19.9 per year; R2 = 80.7%), implying that the thematic vocabulary is expanding faster than publication counts. This widening suggests broader topical coverage and finer-grained tagging, consistent with a maturing field featuring more subtopics per paper and greater methodological and application diversity.

Throughout the period, Smart Manufacturing and Industry 4.0 remained the dominant, most persistent keywords, with 42 and 40 total occurrences, respectively, peaking in 2024 alongside the surge in publications. Table 1 lists the 16 most frequently used keywords, which together account for 179 occurrences and reflect the dominant thematic clusters and technological priorities. These terms serve as conceptual and technological anchors for research on industrial digitalization.

Table 1.

Yearly frequency of the most widely used consolidated keywords in smart manufacturing research, 2020–2025.

Several enabling technologies appear as consistent secondary themes. AI and ML occurred 14 and 10 times, respectively, reflecting sustained integration of intelligent, data-driven systems into industrial processes. CPS and IoT, each with nine occurrences, underscore the importance of interconnected, sensor-rich production environments. Industry 5.0, with eight occurrences concentrated in recent years, signals a shift towards human-centric, sustainable, and resilient manufacturing paradigms. Digital Twin(s), though less frequent (six occurrences), indicates growing interest in virtual representations for simulation and lifecycle management.

Other keywords, Big Data, Automation and Control, Cloud Computing, and Blockchain, appear less frequently but indicate specialized research directions. Their modest representation may reflect absorption into broader constructs (e.g., Industry 4.0 or AI) or a narrower topical focus within the reviewed literature.

Overall, the rising number of keywords per year and the diversification of themes indicate a shift from foundational technological enablers towards more complex, multidisciplinary studies that combine technology, organization, and sustainability.

4.2. Keyword Co-Occurrence

We analyze the co-occurrence structure of industrial digitalization keywords to understand how core concepts connect in practice and where the literature concentrates. Focusing on the top 20 terms (binary counting; minimum co-occurrence ≥1) and normalizing variants via a thesaurus, the map (Figure 3) shows how umbrella concepts (Industry 4.0, Smart Manufacturing) interface with enabling capabilities (AI, IoT), intermediate constructs (Digital Twin, Industry 5.0, Sustainability), and the control layer (Automation and Control, CPSs, Robotics). Node size is proportional to term occurrences, and edge thickness reflects co-occurrence weight. The code was implemented in Python 3.12 using NetworkX (nx.Graph) 3.3 for graph construction and Matplotlib 3.9.1 for rendering.

Figure 3.

Co-occurrence network of the top 20 keywords in industrial digitalization literature.

The co-occurrence graph exhibits a dense hub-and-spoke topology centered on “Industry 4.0” and “Smart Manufacturing”. These hubs connect strongly to “Digitalization”, “Artificial Intelligence”, and “Internet of Things”, indicating that practical work often sits where hub terms meet data and AI capabilities. “Digital Twin”, “Industry 5.0”, “Sustainability”, and control-layer terms (“Automation and Control”, “Cyber-Physical Systems”, “Robotics”) appear as linked satellites, consistent with an end-to-end stack from sensing and analytics to closed-loop control.

Occurrence counts confirm two anchors, “Industry 4.0” (37) and “Smart Manufacturing” (32), followed by “Digitalization” (18), “Artificial Intelligence” (13), and “Internet of Things” (9). Mid-tier terms (“Digital Twin”, “Industry 5.0”, “Sustainability”) indicate growing emphasis on virtualization, human-centric objectives, and efficiency. Overall, the corpus balances hub terms with enabling data/AI and emerging virtualized operations.

The strongest pairs, “Industry 4.0”–“Smart Manufacturing” (19) and “Industry 4.0”–“Digitalization” (15), locate the core between strategy and implementation. Other high-weight links, “Smart Manufacturing”–“Artificial Intelligence” (7), “Smart Manufacturing”–“Digitalization” (7), and “Industry 4.0”–“Artificial Intelligence” (7), show AI embedded in shop-floor programs. The tie “Industry 4.0”–“Sustainability” (6) suggests that environmental aims now co-evolve with digitalization.

Three clusters are evident. Cluster 1 (n = 10) is the platform/operations core around “Industry 4.0”, “Smart Manufacturing”, and “Digitalization”. Cluster 2 (n = 7) groups data/AI/connectivity (“Artificial Intelligence”, “Internet of Things”, “Industry 5.0”), reflecting analytics-driven, human-centered transitions. Cluster 3 (n = 3) captures control/actuation (“Automation and Control”, “Cyber-Physical Systems”, “Robotics”). The layering maps cleanly onto strategy/operations–data/AI/connectivity–control.

Neighbor sets reinforce hub roles. For “Industry 4.0”, leading ties are to “Smart Manufacturing” (19), “Digitalization” (15), “Artificial Intelligence” (7), “Sustainability” (6), “Internet of Things” (4), and “Automation and Control”/“Digital Twin” (4). For “Smart Manufacturing”, the strongest neighbors are “Industry 4.0” (19), “Digitalization” (7), “Artificial Intelligence” (7), and “Internet of Things” (5). Impactful studies therefore combine hub terms with AI/IoT and, increasingly, twins and sustainability.

Cross-clustering is led by Cluster-1–Cluster-2 with a summed weight of 71, well above Cluster-1–Cluster-3 (16) and Cluster-2–Cluster-3 (9). Most bridging therefore occurs between platform/operations and data/AI/connectivity, rather than between analytics and pure control topics.

The strongest bridges link Cluster-1 terms (“Industry 4.0”, “Smart Manufacturing”) to Cluster-2 terms (“Artificial Intelligence”, “Internet of Things”, “Industry 5.0”), marking the corridor where analytics is translated into shop-floor outcomes. Bridges to the control cluster are fewer and weaker, indicating that although control/robotics is present, it is less frequently the primary integration frontier in this corpus.

Using co-occurrence weights (normalized to [0, 1]) converted to a precomputed distance matrix, the silhouette coefficient for the three detected communities is 0.037. By convention, values near 0.5 indicate well-separated clusters, 0.2–0.3 moderate separation, and values near 0 indicate substantial overlap. Thus, 0.037 suggests highly overlapping themes: many terms connect across communities, consistent with an integrated stack in which hub terms, analytics, and control are frequently co-mentioned. Methodologically, this argues for caution with hard partitions and, where appropriate, for reporting overlapping structures (e.g., edge-weighted bridges and hub roles) rather than emphasizing discrete topic silos.

The obtained map depicts a field organized around two top-level anchors that bind enabling AI/IoT to a growing layer of virtualized and sustainability-oriented practices, with thinner but present links to control/actuation. The low silhouette score supports the view that boundaries are porous; the most informative signals lie in the bridges (Industry 4.0/Smart Manufacturing–AI/IoT) and mid-tier constructs (Digital Twin, Industry 5.0, Sustainability) that shorten the path from data to operations. Stronger integration with the control layer (latency-aware, safety-assured, repeatable patterns for SMEs) and systematic reporting of operational KPIs would improve interpretability and evidence of impact.

These results motivate a thematic analysis that organizes the literature into its principal topics.

4.3. Identification and Synthesizing of Key Research Topics

This section provides a chronological synthesis of the key research topics identified in the reviewed literature on industrial digitalization. To trace the evolution of scholarly focus, the analysis is organized by publication year and highlights how dominant themes and methodological approaches shifted from 2020 to 2025.

The year 2020 marked a formative stage in Industry 4.0 scholarship, characterized by a strong focus on establishing the technological and methodological foundations of smart manufacturing. Three dominant themes emerged. The first centered on smart manufacturing infrastructure and enabling technologies, framing the digital backbone of modern factories through the convergence of IoT, IIoT, CPS, edge and cloud computing, blockchain, and cybersecurity. This line of research reflected a growing awareness of the need for integrated, interoperable platforms capable of supporting real-time data exchange and distributed intelligence [36]. The second theme addressed performance measurement and operational optimization, particularly within small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMMEs). Scholars sought to formalize evaluation frameworks and decision-support tools that link technological adoption to measurable performance gains [32]. The third focus area was AI-driven predictive maintenance and data analytics, where machine learning techniques were leveraged for intelligent fault detection, condition monitoring, and sustainability-oriented asset management [18].

In 2021, research momentum accelerated towards integration and digital adoption across industrial ecosystems. Studies increasingly examined the challenges of transitioning from conceptual frameworks to operational implementations, emphasizing CPS-centric architectures and maturity models to guide Industry 4.0 adoption. A prominent thread explored IoT- and IIoT-enabled DT, where virtual replicas interact dynamically with physical systems to enhance predictive logistics and system validation [37]. Meanwhile, the Quality 4.0 paradigm gained traction by integrating AI, big data analytics, and process optimization techniques to advance precision, traceability, and decision intelligence in manufacturing [24]. Parallel research combined edge, fog, blockchain, and cloud infrastructures with machine learning to improve workload balancing and secure data transactions [38]. A notable shift towards sustainability and the nascent Industry 5.0 vision also emerged, emphasizing Green IoT and circular economy principles as essential dimensions of digital transformation [39]. Together, these studies illustrate how the early 2020s laid the groundwork for a more interconnected, data-intensive, and sustainability-aware manufacturing paradigm.

Research in 2022 began to expand beyond the Industry 4.0 paradigm towards the emerging vision of Industry 5.0, emphasizing human–machine collaboration, sustainability, and systemic integration. Akundi et al. [40] identified key Industry 5.0 research themes, including smart and sustainable manufacturing, IoT- and AI-driven transformation, and human–machine connectivity. Another prominent focus in 2022 was the advancement of DT technologies as a cornerstone of smart manufacturing. Onaji et al. [22] proposed a conceptual DT model emphasizing interoperability between product and process dimensions to enhance flexibility and real-time responsiveness in production. Expanding this perspective, Wang et al. [23] examined DT implementation in energy systems, demonstrating the convergence of IoT, big data, and cloud computing for efficient energy management and sustainability monitoring. In parallel, research on IoT-based infrastructures and big-data analytics gained further momentum. For instance, Gellert et al. [41] proposed a hybrid model for adaptive assembly support, and Kahveci et al. [42] presented a modular big-data platform for IoT-enabled factories. At the organizational level, Sofić et al. [43] highlighted digital servitization as a driver of firm resilience, while Suuronen et al. [26] analyzed digital business ecosystems as frameworks for collaborative value creation. Finally, Šverko et al. [44] examined how SCADA system evolution under Industry 4.0 is reshaping control architectures towards greater interoperability. Collectively, these studies indicate that 2022 marked a turning point towards more integrated, intelligent, and human-centered manufacturing ecosystems, laying important technological and conceptual foundations for Industry 5.0.

By 2023, there was a clear consolidation of Industry 4.0 principles towards intelligent, sustainable, and strategically aligned manufacturing systems, with an increasing focus on the integration of AI, advanced automation, and cognitive technologies. A central research stream in 2023 focused on the strategic influence and adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies. Studies such as Abdullah et al. [45] and Serey et al. [27] emphasized that the success of digital transformation depends on systematic evaluation and alignment of emerging technologies with corporate strategy (indicating the growing importance of organizational and process improvements). Another dominant theme in 2023 was the rise of machine intelligence and automation as drivers of adaptive manufacturing. Chen et al. [46] proposed a structured roadmap for implementing machine learning in production systems, while Nagy et al. [47] explored the role of autonomous robotics and deep learning within small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Sustainability and energy efficiency also emerged as critical priorities. Chinnaithai et al. [48] proposed a digital life-cycle management framework for sustainable smart manufacturing in energy-intensive industries. Similarly, Inyang et al. [49] discussed applications of sustainable smart manufacturing in the automotive industry, emphasizing how CPS, smart sensors, and cloud-based analytics can reduce energy consumption and environmental impact while maintaining competitiveness.

Finally, the evolution of connectivity and human roles within the digital factory gained renewed attention in 2023. Martínez-Gutiérrez et al. [50] advanced the notion of hyperconnectivity, demonstrating the potential of real-time communication between human, physical, and cyber assets. This aligns with Ryalat et al. [51], who showcased a practical design for a smart factory based on CPS and IoT technologies, confirming the feasibility of intelligent, modular production architectures. The human element was highlighted by Hozdić et al. [52], who traced the transformation of worker involvement from digitalization to “cognitization”, proposing the emergence of Cognitive Cyber-Physical Production Systems (C-CPPS) to leverage human intellect in tandem with automation. In parallel, Voinea et al. [28] mapped the evolution of industrial augmented reality (IAR), identifying its growing application in training, maintenance, and human–machine interaction. Taken together, the research landscape of 2023 illustrates a maturing convergence of intelligence, sustainability, and human participation in manufacturing. The focus had decisively shifted from mere technological experimentation towards strategic alignment, cognitive integration, and sustainable value creation, paving the way for the industrial ecosystems envisioned in Industry 5.0.

The research landscape of 2024 reflects a decisive evolution of industrial digitalization from the implementation of isolated Industry 4.0 technologies towards intelligent and sustainable production ecosystems. This year was marked by a growing emphasis on the maturity, interoperability, and human-centric evolution of digital systems, as well as on conceptual bridges between the Industry 4.0 paradigm and the emerging Industry 5.0 vision. A first dominant theme in 2024 concerned the maturity and performance assessment of digital manufacturing systems. Studies such as Ahn et al. [53] and Bianchini et al. [54] developed structured frameworks and maturity models to evaluate the implementation level of MES and to quantify automation capabilities within production operations. Simultaneously, research increasingly emphasized the synergy between sustainability and digital transformation. Works by Ali et al. [55] and Martín-Gómez et al. [56] illustrated how enabling technologies—including IoT, additive manufacturing, and AI—can support sustainable development goals through resource efficiency, waste reduction, and environmentally conscious production. The strategic and organizational dimensions of digitalization also gained prominence: Basile et al. [6] and Bezerra et al. [57] showed that the success of digital transformation depends on multi-level readiness (spanning firms, industries, and regions) and on aligning corporate and sustainability strategies, particularly in complex sectors such as shipbuilding.

A further key research direction in 2024 focused on modest cross-technology convergence, typically combining two or three digital technologies, resulting in hybrid, intelligent systems. Ryalat [58] and Singh [59] exemplified this trend through their work on integrating mechatronic systems, robotics, and DT to enable real-time data exchange and simulation in smart factories. Similarly, Mu [60] and Kim et al. [61] proposed AI- and sensor-fusion-based monitoring systems that enhance precision, defect detection, and adaptability—demonstrating the growing maturity of cyber-physical integration. Complementary to these technological advancements, Ghosh et al. [21] and Khalil et al. [62] showcased the potential of machine learning and fuzzy logic for predictive quality control and process optimization, moving manufacturing closer to the vision of autonomous, self-optimizing production systems. Another notable topic in 2024 was the intersection of lean manufacturing principles with Industry 4.0 technologies, as discussed by Benslimane et al. [25]. Their analysis highlights a reciprocal relationship between the two paradigms: lean methods can facilitate digital adoption, while digital tools amplify efficiency and sustainability. This synthesis of operational simplicity and technological sophistication signals a transition towards Industry 5.0, where collaboration, adaptability, and human value creation become central. Finally, meta-analyses and bibliometric studies (e.g., Rosak-Szyrocka [63], Reyes Domínguez [33]) provided an overarching view of global research dynamics, confirming the consolidation of topics such as AI, IoT, smart manufacturing, and sustainability as dominant pillars of industrial digitalization. These studies also revealed expanding international collaboration networks and a shift towards multidimensional, interdisciplinary approaches. In summary, the body of research published in 2024 signifies a phase of consolidation, integration, and conceptual expansion in industrial digitalization. The year stands out for bridging the gap between technological sophistication and strategic, sustainable transformation—an essential step towards realizing the Industry 5.0 manufacturing ecosystems.

Research published in the first seven months of 2025 marks a shift from technological experimentation to intelligent integration and conceptual maturity within digital manufacturing. The focus expanded from connectivity and automation to explicitly human-centered, sustainable, and adaptive systems, aligning with the emerging Industry 5.0 paradigm. Qiu [31] emphasizes the convergence of IoT, IIoT, and CPS as a foundation for smart manufacturing, underlining the importance of AI, machine learning, and 5G communications in enabling real-time data exchange and secure industrial networks. Extending beyond Industry 4.0, Zhang [64] introduces Digital Twin Systems Engineering (DTSE) as a bridge to the Industrial Metaverse, showing how AI-driven digital twins can connect physical and virtual domains through intelligent, human-centric design. Overall, the studies of 2025 illustrate a strategic transition from digitalization to cognification, highlighting inclusivity, intelligence, and sustainability as core principles guiding the evolution towards Industry 5.0.

An overview of these shifts appears in Table 2, which consolidates the period focus, key technical and organizational threads, and representative sources for each period.

Table 2.

Topic evolution in industrial digitalization (2020–2025).

Between 2020 and 2025, research on industrial digitalization progresses from building core infrastructure and measurement, through human-centered and ecosystem perspectives with scaled AI, to mature, production-grade applications and pragmatic solutions for SMEs.

Foundations and consolidation (2020–2021)—The field concentrates on wiring factories for data and trust, building out IoT/IIoT and cyber-physical systems, and pushing computation to edge and cloud with security, and occasionally blockchain, as the trust layer. In parallel, researchers formalize performance measurement and optimization, and predictive maintenance becomes the clearest early AI value case. By 2021 these ingredients are packaged into more integrated stacks that support real-time quality (Quality 4.0), while DT enter regular use and sustainability is framed explicitly through Green IoT and early Industry 5.0 language.

Human-centered turn and AI scale-up (2022–2023)—Attention shifts from “what to deploy” to “how people and organizations create value with it”. Human-centered Industry 5.0, collaboration, skills, and HMI come to the fore, even as plants deepen IoT–big-data pipelines and modernize SCADA/ICS for interoperability. At the same time, AI/ML scales from pilots to shop-floor routine: defect detection, predictive analytics, and process optimization operate at meaningful scope. Enterprises begin governing digital transformation more programmatically, with readiness, capability-building, and change management becoming part of the research conversation.

Application maturity and pragmatic synthesis (2024–2025 to 31 July 2025)—Work becomes decisively application-heavy and production-speed. Machine-vision quality inspection using deep learning and line-scan hardware runs in real time on the line. DT pipelines mature, often coupling simulation environments with robotics under tight latency and fidelity constraints. Formal maturity/readiness models help firms benchmark MES and production-system progress. Domain expansion is visible in bioprocessing and chemicals, while sensor-fusion “digital shadows” and acoustic-emission monitoring deliver continuous, predictive process intelligence. In early 2025, two complementary strands dominate: integrative reference architectures and reviews that stabilize best practice around IIoT and AI-enhanced DT (including the industrial Metaverse), and cost-aware, SME-friendly methods such as current-sensor fingerprinting, alongside sector-specific digitalization with stronger sustainability and supply-chain lenses. The smaller number of 2025 papers reflect the selection cut-off of 31 July 2025.

To quantify these thematic shifts, Table 3 counts the number of reviewed articles addressing each major topic by year.

Table 3.

Number of articles discussing each topic by year (2020–2025).

As shown in Table 3, the literature initially concentrates on foundational Industry 4.0 technologies in 2020–2021, when IoT/IIoT, CPS, and related infrastructure dominate. From 2022 to 2024, Industry 5.0–oriented work expands, reflecting a shift towards human-centric and sustainability goals, while contributions in simulation and AI (e.g., DT) remain steady throughout. In 2024, Quality 4.0 research spikes, driven by studies on intelligent monitoring and predictive quality control. By early 2025, the share of papers focused primarily on core Industry 4.0 technologies declines further as attention moves to higher-level integration and impact themes.

The trajectory of the literature content from 2020 to 2025 indicates a clear shift from introducing discrete digital technologies towards orchestrating holistic industrial transformation. However, the predominance of single-technology perspectives limits their usefulness for guiding comprehensive change. Only a minority propose implementation-oriented frameworks, and cross-technology relationships are seldom examined. This fragmentation reinforces the need for a systematic, integrative framework that synthesizes existing knowledge and maps interdependencies among multiple Industry 4.0 technologies, operational strategies, and business-specific requirements. To address these gaps, the next section introduces a unified, adaptive framework for integrating modern digital technologies and tools.

5. Proposed Conceptual Framework for Industrial Digitalization

This section presents a conceptual framework for the digitalization of industrial companies within the Industry 4.0 context (Figure 4). The framework offers a structured approach that supports core functional areas and business processes. It serves both as a strategic compass—aligning digital initiatives with long-term business objectives, and as an operational roadmap, coordinating implementation across technical, human, and organizational domains. Its purpose is to help companies move from fragmented, technology-driven projects towards value-centered smart manufacturing ecosystems, in which interconnected IT solutions work synergistically to enhance productivity and competitiveness.

Figure 4.

The flowchart of proposed framework for industrial digitalization. Remark: In this infrastructure architecture, solid black arrows denote direct client–service communication, while dashed black arrows represent service-mediated interactions. The exact configuration may vary with company-specific solutions.

5.1. Framework Architecture and Design

The proposed framework is built as a multi-layered, intelligent architecture that integrates machines, data, software, and people into a unified industrial ecosystem. Layer 1 (physical layer) encompasses all production assets, from semi-automated workstations involving human operators to fully automated systems such as robotic arms, computer numerical control (CNC) machines, and automated guided vehicles (AGVs). Equipped with sensors and actuators, these assets continuously capture key operational data (e.g., temperature, pressure, motion, and quality indicators), serving as a bridge between the physical and digital worlds.

Data generated in Layer 1 is immediately transferred to Layer 2 (device/edge layer), where real-time acquisition and initial processing occur. IoT gateways, programmable logic controllers (PLCs), and edge computing devices handle machine-level data close to its source. In some cases, edge AI enables immediate actions such as defect detection, equipment-failure prediction, or alarm triggering. This layer is critical for rapid responsiveness, particularly in time-sensitive or safety-critical operations. In semi-automated systems, it is also the point of human–machine interaction, often supported by smart interfaces or augmented-reality tools.

Layer 3 (fog layer) acts as an intermediate coordination layer between the edge and the cloud. In this layer, data from multiple machines and edge devices across the plant is aggregated, synchronized, and analyzed. Fog nodes, typically hosted on local servers or industrial PCs, enable high-resolution analytics and the coordination of production activities without sending all data to the cloud. This layer often incorporates local information system (LIS) and DT, providing real-time workflow visibility, scenario simulation, and dynamic process adjustments. In facilities with both human-operated and robotic stations, Layer 3 functions as the central hub that integrates diverse processes into a unified and optimized production flow.

A special case within this layer is the warehouse system. Due to its complexity and logistics-specific needs, it often requires dedicated software. Modern Warehouse Management Systems (WMS) handle inventory tracking, automated storage and retrieval systems (ASRS), picking strategies, order consolidation, and logistics coordination. In highly digitalized environments, WMS can integrate with mobile robots, barcode scanners, and RFID systems, collecting data in real time and making autonomous adjustments to inventory flows. These systems are commonly coupled with MES and enterprise resource planning (ERP) platforms, enabling synchronized production and delivery schedules. In some settings, warehouses also use edge computing for local optimization and buffering, while leveraging cloud analytics for broader supply-chain visibility.

Layer 4 (cloud layer) operates above the plant level, aggregating data from multiple facilities or departments to provide enterprise-wide intelligence. It encompasses platforms for data storage, ML, business analytics, and enterprise systems such as ERP, CRM, and SCM. Within this layer, DL algorithms can be trained on extensive historical datasets, enabling long-term trend analysis, predictive modeling, and global optimization across product lines or geographic regions. For example, cloud-based AI can forecast market demand, recommend supply chain adjustments, or detect efficiency gaps across facilities, extending digitalization from individual machines or factories to the entire organizational ecosystem.

The Decision support layer bridges the operational layers (edge, fog) and enterprise-wide intelligence (cloud), translating automated processing and AI insights into actionable guidance. It aggregates data from MES, WMS, ERP/MRP, and AI analytics to support transparency, interpretability (XAI), and human-in-the-loop control, including scenario simulation and what-if analysis via DT. It aligns operations with strategy and strengthens responsiveness and coherence across the organization. It is applied across functional areas—manufacturing (R&D, process engineering, manufacturing planning), marketing and sales, HRM, and accounting and finance—through role-appropriate dashboards, alerts, and decision aids.

In the framework diagram, the strategic-management block is positioned above cloud-based ERP and other operational systems because it defines the overarching vision, long-term objectives, and resource-allocation principles that guide how digital tools are selected, integrated, and leveraged, ensuring that technology adoption aligns with business goals rather than driving them in isolation.

The key advantages of this digitalization framework lie in its scalability, responsiveness, and intelligence. By distributing data processing across edge, fog, and cloud layers, the system achieves both low-latency control and long-term strategic insight. This architecture supports real time decision-making on the factory floor while enabling enterprise-wide optimization from the cloud. Moreover, the integration of semi-automated workstations ensures that human skill remains embedded in the digital workflow, making the system more resilient to uncertainties such as changes in product types, customer demands, or supply-chain disruptions.

Another important benefit is modularity. Companies, especially SMEs, which often operate with limited capital, lean IT teams, and heterogeneous legacy equipment, can adopt the framework gradually, starting with low-cost sensorization and edge-level analytics, then integrating fog coordination, cloud-based intelligence, and AI tools as capabilities mature. SMEs can prioritize quick-win pilots with clear ROI, leverage off-the-shelf hardware and managed cloud services to reduce upfront costs, and rely on open standards to avoid vendor lock-in and ease interoperability. This flexible, layered approach enables cost-effective digital transformation tailored to the organization’s size, maturity, and sector-specific needs.

In summary, this multi-layered architecture provides a robust, intelligent, and human-centered structure for achieving industrial digitalization. It supports hybrid workflows with both operator-driven stations and autonomous systems, enabling enhanced productivity, quality, and strategic agility in a connected manufacturing environment.

In contrast to existing approaches, which often emphasize specific facets of industrial digitalization, such as hybrid modeling [20], digital twin integration [22,59,64], quality management [24,30], lean implementation [25], strategic alignment [27], performance metrics [32], human–automation collaboration [34], life-cycle management [48], or sustainability [56], the proposed framework adopts a more comprehensive perspective. It synthesizes these diverse elements into a unified, multi-layer architecture that spans shop-floor devices, edge intelligence, cloud analytics, and strategic coordination. While retaining the strengths of prior models, such as alignment with business objectives and closed-loop feedback mechanisms—the framework adds further value by integrating technologies across domains, enabling modular scalability, and bridging the gap between technical infrastructure and organizational processes. This results in a cohesive, human-centric roadmap for industrial digitalization, tailored for dynamic and interconnected manufacturing environments.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. The interconnected modules depend on edge, fog, and cloud infrastructures for data exchange and coordination which, while enabling flexibility and scalability, also introduce performance dependencies and cybersecurity risks. Such risks can be particularly challenging for SMEs, which often lack the IT capacity and specialized expertise needed for effective mitigation. The framework’s reliance on LIS further creates the potential for bottlenecks if not properly optimized. In addition, even with a modular adoption pathway, successful implementation requires ongoing staff training and organizational adaptation—demands that may be especially difficult for smaller teams to meet.

Overall, the proposed framework enables low-latency, intelligent control while ensuring strategic coordination across manufacturing processes. It aligns with the objectives of Industry 4.0 by embedding intelligence across system levels and promoting scalability, operational flexibility, and autonomous decision-making. The design ensures seamless integration and coordination among core business functions while preserving the flexibility needed to adapt to dynamic manufacturing environments, where resource performance, operational conditions, and production demands may shift over time.

5.2. Framework Validation

This subsection validates the applicability and effectiveness of the proposed digitalization framework through a PoC in an electronics manufacturer. The goals are to demonstrate feasibility, map current capabilities to the framework’s layers, and verify that targeted interventions yield measurable maturity gains. One co-author participated in the implementation (process mapping, MES configuration, edge-analytics pilots), ensuring traceability between design and deployment.

In 2023, the company moved to a new facility, automated a large share of line operations, and reported higher throughput and quality. In 2024, one of the main production lines was fully automated and overall capacity expanded. In 2025, the company adopted the framework as a PoC, deploying collaborative robots; adapting the barcode system to support typical MES functions; integrating with ERP; and introducing advanced planning within an edge/fog environment (Figure 4).

Layer mapping showed the following. Layer 1 comprised semi- and fully automated stations (robotic arms, CNCs, AGVs) with partial sensorization. The framework closes sensing gaps on bottleneck assets. Layer 2 used PLC/IoT for partial real-time data but lacked edge analytics. The PoC introduced edge AI for predictive maintenance and rapid fault detection. Layer 3 had a basic MES focused mainly on technological/process operations, with no fog layer or DT; the framework prescribes fog-level coordination, station-level twins, and WMS–MES integration. The warehouse used barcode-based inventory without advanced WMS or mobile robotics. The plan links WMS to MES and evaluates AS/RS. Layer 4 relied on ERP with limited cloud analytics; the plan extends cloud AI for demand forecasting and long-horizon optimization. Decision support was previously dashboard-only. The framework adds XAI and scenario simulation for transparent human–AI decision-making.

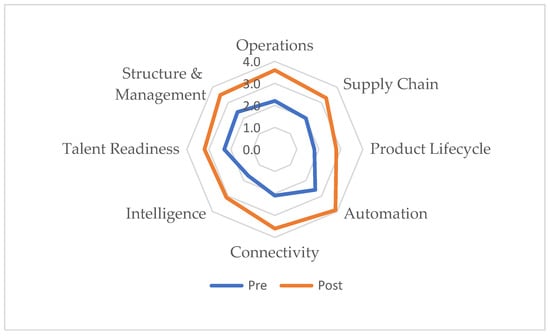

To triangulate the layer-level findings, we assessed digital maturity using the Smart Industry Readiness Index (SIRI) [65]. Three domain experts independently rated each SIRI dimension before the PoC interventions and after the changes described above. Table 4 reports the mean of the three ratings (1 = initial; 5 = leading) before and after the interventions, together with the improvement observed.

Table 4.

SIRI digital maturity scores for the case study.

The SIRI assessment indicates broad, consistent gains. Within the Technology pillar, Automation and Connectivity improved with added sensorization, PLC/IoT deployment, and shop-floor integration, while Intelligence rose with the introduction of edge analytics and early-stage AI for maintenance and quality monitoring. In the Process pillar, Operations and Supply Chain advanced with MES deployment and tighter logistics synchronization, whereas Product Lifecycle remains mid-range due to limited PLM/engineering integration and the absence of end-to-end DT. In the Organization pillar, Structure and Management improved through clearer governance and KPI alignment, and Talent Readiness rose with targeted training for operators and planners. These results align with the framework’s recommendations and the observed performance gains.

Technology maps primarily to Layers 1–3 (automation and sensorization; real-time connectivity and edge analytics; cross-station coordination via MES and DT). Process maps to Layer 3 (operations–logistics integration) and Layer 4 (enterprise planning and analytics). Organization maps to Layer 4 and Decision Support (governance, KPI cascades, XAI-enabled decision support, and workforce upskilling). The largest SIRI gains in Table 4 align with PoC interventions at these layers—sensor expansion, edge analytics, MES rollout and functional expansion, and data-driven decision support. By contrast, the lower post-intervention score in Product Lifecycle indicates the next priority: deeper PLM/engineering integration and model-based engineering beyond isolated cells. Overall SIRI increased by 1.2 points from 2.1 to 3.4 (SD change 0.2), as reported in Table 4.

As a result, the following recommendations can be made:

- Short term—Develop detailed resource-utilization planning and achieve complete sensor coverage on bottleneck assets, with dynamic schedule adaptation to current conditions (e.g., operator availability, unexpected failures, material shortages). Scale edge AI for predictive maintenance. Extend MES to all lines and core operations, and link WMS–MES for closed-loop materials tracking.

- Medium term—Introduce lightweight station-level DT. Pilot cloud-based demand forecasting linked to S&OP. Formalize data governance and tiered KPIs. Deploy AI across all key control operations to cover 100% of processed modules and critical materials.

- Longer term—Integrate PLM with MES/ERP for end-to-end lifecycle visibility. Expand operator and planner training. Deploy XAI dashboards to provide explainable recommendations for scheduling, quality, and maintenance.

We use SIRI as an external benchmark and document change by (1) reporting pre- and post-scores by pillar and dimension (Table 4; Figure 5 and Figure 6), (2) linking each intervention to the specific SIRI dimension(s) it targets, and (3) verifying that maturity gains align with movement in operational KPIs (throughput, quality, lead time). Ratings are anchored in documentary evidence (screenshots, standard operating procedures, network diagrams, MES/WMS logs) and in the framework’s layer logic to reduce subjectivity.

Figure 5.

SIRI maturity radar—Pre- vs. Post-scores by dimension.

Figure 6.

SIRI maturity delta by dimension (Δ = Post − Pre); bars sorted by magnitude.

Figure 5 shows a radar plot of pre- vs. post-SIRI dimension means. The post-polygon (orange) consistently extends beyond the pre-polygon (blue) across all eight dimensions, indicating a broad-based maturity lift rather than isolated wins. The largest outward shifts occur in Connectivity, Automation, Intelligence, Operations, and Supply Chain—the areas targeted by the PoC (sensorization, PLC/IoT integration, MES rollout, edge analytics, intralogistics synchronization). Product Lifecycle expands but modestly, signaling that PLM/engineering integration and DT remain the next frontier. Talent Readiness also improves, though less than the technology-heavy dimensions, consistent with targeted but early-stage training. Overall, the radar indicates coherence (no regressions), coverage (all dimensions improve), and alignment with the layer-level intervention logic reported above.

Figure 6 presents a bar chart of dimension-level deltas. Gains rank as Connectivity (+1.5) > Intelligence/Operations (+1.4 each) > Supply Chain/Automation (+1.3 each) > Structure and Management (+1.1) > Product Lifecycle (+1.0) > Talent Readiness (+0.9). This ordering mirrors the PoC focus on shop-floor data flow, analytics, and execution systems, and highlights two priorities: (1) lifecycle integration remains the main lagging area; and (2) human-capability uplift trails technology uplift and requires a second wave of interventions (skills, new roles, governance routines).

Together, Figure 5 and Figure 6 confirm broad, coherent gains, with the largest improvements where the PoC intervened most directly (Automation, Connectivity, Intelligence; Operations and Supply Chain). Product Lifecycle improves modestly, indicating that PLM/engineering integration and DT are the next frontier. Talent Readiness also rises, though less than the technology-heavy dimensions, consistent with targeted but early-stage training.

Taken together, the intervention-to-layer mapping, pre–post-SIRI gains (Table 4 and Figure 5 and Figure 6), inter-rater agreement, and sensitivity checks indicate that the framework is applicable, actionable, and delivers measurable maturity improvements in an industrial setting. Further gains are expected as PLM integration and advanced decision support are completed.

Adoption followed the framework’s core integration principles: aligning business processes with central ERP/MRP modules; deploying MES for real-time monitoring and control; and leveraging edge and fog layers to reduce latency, improve local data processing, and enable distributed decision-making. A performance review based on publicly available financial reports from three years before and after adoption shows consistent improvement across key financial performance indicators. Beyond financial performance, the company reported enhanced production flexibility, shorter lead times, and more efficient resource utilization. Importantly, these outcomes were achieved despite only partial implementation, suggesting that full deployment could deliver even greater benefits.

Overall, this PoC case study indicates that the proposed multi-layer digitalization framework is conceptually robust and practically feasible. Mapping the company’s capabilities to the framework showed strong alignment in basic automation and ERP-supported processes, while highlighting gaps in advanced analytics, edge AI, and cross-layer coordination.

5.3. Recommendations for Framework Implementation

The framework offers a practical pathway for integrating core digital enablers across the stack (operational technologies, connectivity infrastructure, data platforms, and intelligent analytics) rather than pursuing isolated initiatives. Industrial managers, including those in SMEs, should begin with a candid assessment of technological and organizational capacity, then adopt a phased roadmap that progresses from sensorization and edge analytics to fog-level coordination with MES and, ultimately, cloud intelligence and AI. Interoperability should be secured through open standards and well-defined interfaces to avoid vendor lock-in, while decision support should remain human-centered, using explainable AI and human-in-the-loop controls to retain domain expertise in critical processes. Policymakers can align incentives and funding with staged adoption, enforce baseline requirements for cybersecurity and data governance, and connect digitalization to sustainability and resilience objectives such as energy efficiency, circularity, and supply-chain transparency. Researchers can apply and extend the framework across sectors, study synergies among AI, DT, and robotics, and build evidence that links maturity gains to operational and sustainability outcomes, with special attention to architectures that are feasible for SMEs.

The framework’s layered design, PoC validation, and stakeholder guidance collectively provide a systematic and practical path for industrial digitalization at the company level.

6. Challenges and Future Perspectives in Industrial Digitalization

Industrial digitalization under the Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0 paradigms entail numerous challenges [16] alongside significant opportunities. Nonetheless, the outlook is positive: advances in AI, IoT, CPS, and cloud computing are enabling increasingly intelligent, connected factories. The subsections below summarize the principal challenges and future prospects across the key domains of industrial digitalization.

6.1. Challenges

Adoption of core Industry 4.0 technologies—IoT, robotics, cloud computing, and big data analytics—has transformative potential, but adoption is slowed by system-integration barriers. New tools often lack interoperability with legacy equipment and proprietary platforms; data heterogeneity and partial standards hinder seamless machine–software connectivity [19,50]. Financial constraints also weigh heavily—upfront investments in sensors, infrastructure, and training can be substantial, with delayed returns, particularly for SMEs and firms in less-developed regions [47,66,67]. Organizational constraints include workforce skill gaps [27,67,68], low digital maturity, and cultural resistance to change in traditional industries [30,49,57,66,69]. Finally, security and privacy risks rise with connectivity, elevating the stakes of breaches and industrial espionage and deterring full adoption in some contexts [31,70].

Operations and process improvement: Realizing digitalization’s benefits requires management and process change alongside technology deployment [16]. Integrating Lean manufacturing and Agile project management into historically rigid production systems is challenging [25]. Firms struggle to preserve Lean’s simplicity and waste-reduction focus amid complex, data-driven workflows, and Agile practices can clash with established hierarchies on the factory floor. Resistance is amplified where job displacement is feared or benefits are poorly communicated [57,69]. Skill shortages in both Lean and digital tools lead to underpowered initiatives and weak knowledge transfer [25,49]. Siloed functions limit cross-departmental coordination, constraining dynamic scheduling and just-in-time analytics.

Quality 4.0 (including equipment monitoring and maintenance): Comprehensive equipment monitoring is difficult in plants with older assets; retrofits face the same interoperability and protocol issues noted above [23,29,54,71]. Even when data is collected, firms encounter data overload and fragmentation across systems without common standards [19,23], hindering a holistic view of asset health. Predictive-maintenance models require large, high-quality labeled datasets that many organizations lack [21,46,72]; models can fail to generalize under changing conditions [61,71]. Edge-compute limits may constrain real-time analytics [39,67]. Organizationally, trust and explainability are recurring barriers when maintenance teams hesitate to act on opaque algorithmic recommendations [47,58], especially where ROI remains uncertain [16,30].

Simulation, modeling, and DT: Building accurate DT demands extensive data integration (CAD, sensor streams, historical traces) and consistent semantics; interoperability and data compatibility remain major hurdles [19,61]. Maintaining a real-time cyber–physical link can strain bandwidth and compute, particularly on legacy networks [20,59]. AI/ML models embedded in simulations may degrade under drift or configuration changes [61,71]. Latency for cloud-hosted analytics can undercut time-critical decisions [23,50]. Specialized expertise and coherent toolchains are still emerging, creating a skills/tools gap for many firms [64].

Security of industrial processes: As connectivity deepens, OT assets (robots, controllers, sensors) are exposed to cyber threats that can disrupt production or safety. Many legacy systems lack security-by-design, and IT–OT integration introduces additional attack surfaces [59,70]. Data privacy challenges grow with the volume and sensitivity of industrial data [31,38]. Ensuring secure, end-to-end communication across distributed sites and cloud services is non-trivial, especially when security frameworks are unevenly adopted across supply chains. Compliance and governance demands (e.g., audits, provenance) add overhead and require robust evidentiary mechanisms [64,73]. The rapid evolution of threats necessitates continuous adaptation and upskilling of IT/OT personnel.

Industry 5.0 (human role and sustainability): Transitioning towards human-centric, sustainable industry raises socio-technical challenges [52]. Effective human–machine collaboration requires trust, transparency, and ethics; black-box AI impedes acceptance [30,47,58], and questions of fairness and accountability persist [16,27,51]. The workforce needs new transversal and cognitive skills to collaborate with AI and robotics; concerns about displacement can fuel resistance. On sustainability, aligning digitalization with environmental and social goals remains uneven [33]. Without careful design, digital systems can increase energy use or e-waste; metrics and standards for “green” smart factories are still maturing [25,39].

6.2. Future Perspectives

While significant challenges remain, the digitalization technologies are fostering smarter, more adaptive, and sustainable manufacturing ecosystems capable of real-time decision-making and continuous learning [34,36].

Strategic alignment and maturity: Digitalization should be treated as a strategic transformation, not a standalone technical program. Maturity models and diagnostics help assess readiness and balance managerial with operational dimensions [45,53,54], guiding investment in enablers such as MES, AI analytics, and IoT infrastructure to accelerate movement toward advanced smart-factory models.

Human-centricity and workforce transformation: Shifts from deterministic automation to collaborative, probabilistic frameworks elevate human–machine complementarity and cognitive skills [40,68]. Executive sponsorship, interdepartmental collaboration, and structured workforce development are critical, particularly in supply-chain-integrated settings [71]. SMEs require tailored strategies that balance capital constraints with capability building and technology transfer [54,66].

Data-driven intelligence and learning ecosystems: ML-enabled real-time optimization, defect prediction, and quality enhancement are expanding [19,46]. Moving from big data to smart data improves interpretability and actionability, creating value beyond efficiency [54]. Future work should refine deployment pipelines, standardize implementation practices, and build adaptive intelligence that learns under uncertainty.

Sustainability and digital ecology: Integrating digital transformation with environmental goals advances resource efficiency, waste minimization, and energy transparency, strengthening contributions to the SDGs [55,57]. Combining Lean with IoT and analytics amplifies both efficiency and green outcomes [25]. Sectoral models (e.g., Shipyard 4.0) show how digitalization can support sustainable competitiveness in heavy industry [57].

Ecosystemic and multi-level integration: Benefits extend beyond single firms to networks, industries, and regions [6]. Future manufacturing will evolve within interconnected service ecosystems, where actors co-create value through data interoperability and shared infrastructure.

The next phase of industrial transformation will depend on synergistic integration of digital technologies, human capabilities, and sustainability imperatives. The landscape is shifting from adoption to orchestration, from automation to augmentation, and from efficiency to purpose-driven innovation.

7. Conclusions

This study reviews the state of industrial digitalization (2020–July 2025), synthesizing developments across classical Industry 4.0 technologies, operations and process improvement, Quality 4.0, and simulation/modeling (AI/ML and digital twins), while tracing the rise of Industry 5.0’s human-centric and sustainability priorities. We organize the literature longitudinally, quantify topic salience by year, and highlight how the field shifts from technology deployment to integrated, impact-oriented practice.

Building on this synthesis, we propose a layered, company-level framework that embeds intelligence across physical, edge, fog, cloud, and decision-support layers to enable low-latency control, coordinated operations, and strategic alignment. A field-based validation links framework-guided interventions to improvements in SIRI maturity and operational outcomes, indicating that even partial deployment can enhance flexibility, reduce lead times, and strengthen financial performance. For practitioners, the framework offers a phased path (particularly suitable for SMEs) from low-cost sensorization and edge analytics toward fog/MES coordination and cloud/AI capabilities, complemented by decision-support mechanisms that preserve human oversight. For researchers and policymakers, the results motivate work on interoperable standards, explainable AI for maintenance/quality, and ecosystem-level evaluation.

The proposed holistic framework has several advantages:

- Reveals interdependencies among technologies, resources, and organizational capabilities across time and layers (shop floor, MES/ERP, enterprise level).

- Enables dynamic orchestration of IT/OT by clarifying when and how to integrate automated systems, cloud computing, and AI so they reinforce one another rather than operate in isolation.

- Prevents fragmented initiatives in which isolated projects and siloed technology stacks create inefficiencies and duplicate costs.

- Supports SMEs through modular, phased adoption (low-cost sensorization–edge analytics–fog/MES coordination–cloud/AI), use of open standards to avoid vendor lock-in, and the option to leverage managed cloud services to reduce upfront investment and IT burden.

By embedding intelligence across the physical, edge, fog, cloud, and decision-support layers, the framework supports low-latency control, coordinated operations, and resilience in dynamic manufacturing environments. Looking ahead, effective digitalization will require not only technical integration but also continuous monitoring, iterative refinement, and alignment with evolving market, technological, and sustainability demands. The framework offers a structured pathway to achieve these goals, bridging the gap between conceptual models and real-world industrial implementation. The results indicate that even partial deployment yields measurable improvements in operational flexibility, lead-time reduction, and financial performance, with additional benefits expected upon full deployment. The results indicate that even partial deployment yields measurable improvements in operational flexibility, lead time reduction, and financial performance, with potential for greater benefits upon full deployment.

The review is limited to Scopus and Web of Science and English-language, peer-reviewed sources within 2020–2025; adjacent domains (e.g., safety, standards, regulation) are underrepresented, and, despite PRISMA procedures, screening/coding involve human judgment.

Future research should expand coverage beyond Scopus and WoS to include specialized repositories; incorporate gray literature and non-English sources to reduce language and publication bias; and consider earlier foundational studies to provide historical and technological context. It should also broaden the thematic scope to adjacent domains for a more holistic view of industrial digitalization under Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0. In parallel, studies should track the trajectory of digitalization technologies and identify under-deployed application areas where benefits appear plausible but evidence remains limited (e.g., PLM–MES–ERP integration, edge AI for latency-critical quality control, closed-loop scheduling across MES/WMS/intralogistics, and embedded sustainability analytics). Finally, stakeholder perspectives deserve dedicated attention: operators, planners, maintenance personnel, IT/OT security teams, and executives have different preferences and constraints. Therefore, usability, explainability, and organizational acceptance should be evaluated explicitly in real industrial settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/info16121080/s1, PRISMA Checklist. Reference [74] is cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.I. and T.Y.; framework, G.I.; validation, Y.I.; formal analysis, G.I., T.Y., P.S. and G.R.; resources, G.I. and T.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, G.I., T.Y., P.S. and G.R.; writing—review and editing, G.I., T.Y. and Y.I.; visualization, T.Y.; supervision, Y.I.; project administration, T.Y.; funding acquisition, G.I., T.Y., P.S. and G.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by Project BG16RFPR002-1.014-0013-C01, “Digitization of the Economy in a Big Data Environment”, under the “Research, Innovation and Digitalization for Smart Transformation” Program 2021–2027, and co-financed by the European Social Fund and Project BG05SFPR001-3.004-0016-C01, “Support for the Development of Project-based Doctoral Studies at the University of Plovdiv ‘Paisii Hilendarski’”, under the “Education” Program 2021–2027, co-financed by the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/vj2wvzm4y2/1 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the academic editor and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yuliy Iliev was employed by the company Teletek Electronics. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- The Rise of Industry 4.0 in 5 Stats. Available online: https://iot-analytics.com/industry-4-0-in-5-stats/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Culot, G.; Nassimbeni, G.; Orzes, G.; Sartor, M. Behind the definition of Industry 4.0: Analysis and open questions. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 226, 107617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid-Guijarro, A.; Maldonado-Guzmán, G.; Rodríguez-González, R. Unlocking resilience: The impact of Industry 4.0 technologies on manufacturing firms’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Manag. Decis. 2025, 63, 126–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. Industrie 4.0. Available online: https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/EN/Dossier/industrie-40.html (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- People’s Republic of China State Council. Made in China 2025 (English Translation). Available online: http://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latest_releases/2015/05/19/content_281475110703534.htm (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Basile, V.; Tregua, M.; Giacalone, M. A three-level view of readiness models: Statistical and managerial insights on Industry 4.0. Technol. Soc. 2024, 77, 102528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST Industrial Automation. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/industrial_control_system (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- NIST IIoT. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/industrial_internet_of_things (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- NIST SP 800-145. The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/145/final (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- NIST Artificial Intelligence. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/artificial_intelligence (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- NIST Big Data. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.1500-1r2.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Industry 5.0 European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation; Breque, M.; De Nul, L.; Petridis, A. Industry 5.0—Towards a Sustainable, Human-Centric and Resilient European Industry; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/308407 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Zhou, K.; Liu, T.; Zhou, L. Industry 4.0: Towards future industrial opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2015 12th International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (FSKD), Zhangjiajie, China, 15–17 August 2015; pp. 2147–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavese, D.; Mannella, L.; Regano, L.; Basile, C. Security at the edge for resource-limited IoT devices. Sensors 2024, 24, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieste, M.; Orzes, G.; Culot, G.; Sartor, M.; Nassimbeni, G. The “dark side” of Industry 4.0: How can technology be made more sustainable? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2024, 44, 900–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayem, A.; Biswas, P.K.; Khan, M.M.A.; Romoli, L.; Dalle Mura, M. Critical Barriers to Industry 4.0 Adoption in Manufacturing Organizations and Their Mitigation Strategies. J. Manuf. Mater. Process 2022, 6, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]