Abstract

The background of the paper is that there are currently no specifications or guidelines for the design of a user interface for an augmented reality system in an industrial context. In this area, special requirements apply for the perception and recognition of content, which are given by the framework conditions of the industrial environment, the human–technology interaction, and the work task. This paper addresses the software-technical design of augmented reality surfaces in the industrial environment. The aim is to give first design examples for software tasks by means of sample solutions. For a user-oriented implementation, the methods of personas and an empirical investigation were used. Personas are a stereotypical representation of end users that reflect their characteristics and requirements. For the subsequent development of the pattern catalog, different prototypes with layout and interaction variants were tested in an empirical study with 50 participants. By observing the current realizations, these can be examined more closely in terms of their specific use in an industrial environment. The result is a pattern catalog with 26 solutions for layout and interaction variants. For the layout variants, no direct favorite of the testers could be ascertained; the existing solutions already offer a wide spectrum, which are chosen according to personal preferences. For interaction, on the other hand, it is important to enable fast input. During the study, gesture control revealed weaknesses in this regard. This can be supportive in the development of an industrial augmented reality system regarding a user-oriented representation of the interface.

1. Introduction

Virtual augmented reality is currently experiencing a surge in development [1]. Smartphones and computers of all kinds have a camera as basic equipment and are constantly improving in terms of computing power. Recording the real environment and combining content at the same time is becoming easier.

Digitization in the industrial sector forms the basis for the integration of augmented reality (AR) [2]. It promotes the shift from analog to digital data. For example, data sent to servers by machines or products throughout the production process are processed digitally. The development effort for companies needs to be lowered so that AR can become more widespread and naturally integrated into industrial workflows.

The high heterogeneity of the user interface (UI) in commercially available head-mounted displays (HMD) makes it difficult for developers to find an ergonomically high-quality solution for the specific tasks in the production environment [3]. To maintain a high ergonomic level in the UI of an AR system in an industrial context, already proven UI elements and standards should be used. It is relevant to pay attention to consistency, controllability, self-descriptiveness, learning conciseness, and task appropriateness. In the production environment, which is characterized by many task-relevant stimuli, information in the AR glasses should be perceived and recognized very quickly and transferred into actions [4]. Currently, there are no generally applicable regulations that deal with the design of a user-oriented UI. Several de facto standards have been formed by the market leaders of AR glasses. Problematically, no ergonomic quality of these solutions has been studied, but each model addresses some reported user difficulties. This results in a cognitive effort for the user, who is confronted with different layout solutions and interaction sequences of the manufacturers and must adapt to them. This reduces efficiency and effectiveness and increases the error rate. Regarding the industrial environment, no findings have yet been published and defined. Therefore, generic sample solutions for the user interface should be developed, which support the development and are valid for different industries. This paper deals exclusively with the software realization of the layout and selected basic interaction. A differentiated analysis of the hardware is not included.

2. State of the Art

A report from 2018 shows the development of AR/VR in comparison to 2016. It is clear that developments in gaming are declining and that the focus is more on research, marketing and retail [5]. Furthermore, reports clearly show that user experience is still the driving force behind the use of the technology and that attractive usage can only be achieved within the next three years [5]. However, the report also shows that there is great potential for specific tasks in the production environment.

In recent years, the interface of AR has been intensively studied. In 2016, Dey et al. analyzed 291 AR papers from 2005 to 2014 [2]:

- About 10% dealt with the industrial environment;

- About 35% dealt with HMDs, with a decreasing trend since 2010;

- About 24% obtained their results in field and pilot tests.

Thus, the research results from 2005 to 2015 provide little evidence to answer the above research question due to the heterogeneity of the technology used, application field, and evaluation method. In the years from 2015 onward, there have been only a few publications dealing with AR applications in an industrial context. Like Takatsu et al. [6], most papers dealt with the technical realizations, such as a digital service platform, exploring the integration of CAD data in an AR system [6]. Design guidelines and interface patterns were also developed by Billinghurst et al. [7] in their 2015 paper. They referred to the Games in Handhelds application domain. Nilsson [8] also investigated design patterns. He looked at display utilization, interaction mechanisms, and general design in handhelds. For the specific tasks in the industrial environment and the product life phases, Danielsson et al. [9] dealt with possible applications in the respective services. The various product life phases and the resulting generic tasks are discussed in Section 3.3.

Fundamental work on the classification of tasks and interactions in virtual contexts was done by Bowman, who distinguished between selection, positioning, and rotation tasks [10]. The following table shows Bowman’s guidelines from 2005, which were adapted to current requirements by LaViola et al. in 2017 [11].

The guidelines for selection and manipulation require that existing techniques are used and that an exception is only made if there is identifiable added value. A trade-off should be made between technique, design, and the environment model. The guidelines for system control consider various forms of interaction techniques, for example, the forms of object visualization in 3D or 2D representations and control via gestures or focusing. The existing representation rules mainly refer to the design of the layout and the visibility of the feedback as well as to the interaction possibilities. In the layout design, the focus is on showing end user content that is perceived well and quickly. The guidelines on user comfort and safety deal with the temporal and spatial correspondence of the virtual and real worlds. Different colors or visible feedback can be used to guide the user. In this context, physical and virtual barriers can also be used to limit the free space. Table 1 shows the current recommendations for the realization of 3D user interfaces. Very partial guidance is given and not a holistic view of UI design. The guidelines of Bowman and LaViola are not fixed rules and are not focused on the specific context of the industrial environment. This current state, therefore, leads to the need for a separate study.

Table 1.

Comparison of Bowman and LaViola 2005 and 2017 design guidelines.

For the present paper, the following guidelines (see Table 2) can be derived from a combination of analytical and empirical analysis. The analytical studies summarize the heterogeneous design guidelines collected in widespread publications. The empirical studies focus on the reflection of these rules in the context of expert interviews. In this context, 10 experts from the industrial sector were interviewed, using a guideline.

Table 2.

AR system specific operationalization of the dialog principles according to DIN EN ISO 9241-110 [12].

For the specific requirements, the dialog principles from DIN ISO 9241-110 [12] were categorized for task appropriateness, self-descriptiveness, conformity to expectations, learning conciseness, controllability, tolerance for errors, and being individualizable. For example, it is required that information in the AR system should be understandable independently of upstream or downstream processes; otherwise, the information volume would be too high for the completion of the individual task. Furthermore, the status information should clearly distinguish between permanent and situational displays. The main menu and orientation displays should always be available to the user, while messages should be faded in and clearly recognizable. For the industrial context, the field of view of the AR system should also be used to its full extent to correspond to the human field of view. If, in addition, information about physical tools is transmitted via the AR system, reality can be completely overlaid with virtual content.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Persona

For the paper, a specific examination of the end user is relevant to capture special needs and characteristics. Personas are suitable for this purpose. These give a fictitious but specific representation of the end user. By using stereotypes, the goals and behaviors of real users can be derived. Personas are derived from information about future users and reflect characteristics relevant to the AR system [36,37,38].

In the literature, despite the emphasis on different advantages (see Table 3), there is a consensus that personas generate a better understanding of the target groups in design teams [38,39,40]. Using personas can be considered a powerful and versatile design tool. In the paper, the persona method is used across all studies to continuously focus on the end users and the work task. In this way, identification with the users takes place, which is still important in the development of the layout variants.

Table 3.

Advantages of using personas.

In the paper, five aids from Cooper et al. [36] are used. The focus is especially on the users’ goals and the identification of behavior patterns [36]:

- The basis for the design effort is formed by personal goals and tasks.

- Personas provide a basis for design decisions and help to ensure that the user is in focus at every step of development.

- Personas make it possible to form a language and thus a common understanding.

- Design decisions can be measured by a persona as well as by real subjects.

- Multiple business units within a company can make use of personas.

For making personas, both Cooper et al. and Pruitt and Adlin [36,37] identified characteristics and behavioral variables that should be captured in a persona. The following should also be included in an adapted manner:

- Description: Name and picture.

- Characteristics: Age, education level, lifestyle, role/professional position.

- Knowledge: Basic attitude, technology knowledge, and technology attitude.

- Concerns and goals: Expectations, qualifications, and goals.

- Activities: Tasks and activities.

These personas should be identified for all areas of product development. In a study on persona development, 40 representative people selected by the companies were interviewed. The subjects worked in four different companies (automotive consumer goods, industrial goods special machinery, industrial goods mechanical engineering, and research product development) and eight professional levels (development, management, engineer, marketing/sales, planning, quality control, engineering, and training) [41]. Using the interview method with subject-matter experts and developers from the industrial environment, the behavioral variables were analyzed. With the help of a guide, questions related to career path, current job, and work environment were asked. Table 4 and Table 5 show, following Pruitt and Adlin, the summary of the characteristics in relation to the traits and behavior variables.

Table 4.

Analysis of persona development data.—Gender and Age.

Table 5.

Analysis of persona development data.—Occupational specialties.

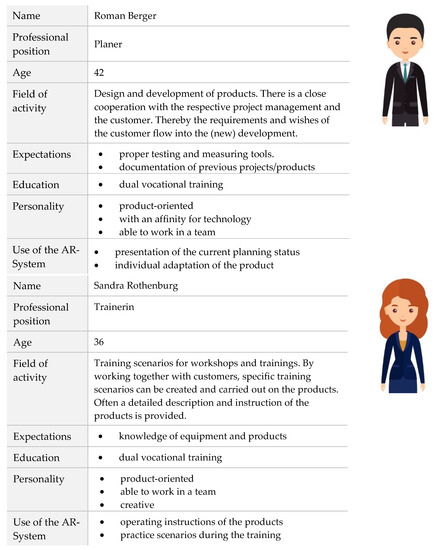

Based on the available results of the target group investigation, four personas were determined, which are representative. In this way, the persona’s planner, technician, quality inspector and trainer were defined. It was observed that the characteristics of the analyzed end users are reflected in the personas. The structure of the personas follows the pattern described above. Each persona was given a name and age, which were chosen fictitiously, and a professional position. Subsequently, the areas of responsibility, expectations and education were determined. Finally, the persona’s personality and its use of the AR system were described. Figure 1 shows the four personas (planner, trainer, quality inspector, and technician) that were extracted from the research.

Figure 1.

Persona (from top left to bottom right: planner, trainer, quality inspector, and technician).

Each persona is representative of a typical user in the life phases of product planning, development/design, manufacturing/assembly, and use. These personas are relevant to the following phases in the research design. They were obtained from the interviews conducted with the representative persons. The description of the range of tasks was given by the respective professional position. Different areas of the life phases were chosen for a wide range of activities. This field then also influences how the persona uses the AR end device. Personal differences occur in expectations and personalities. The interviews were chosen as the basis.

The visualization alternatives were matched to the tasks of the personas. Specifically, this means that icons and buttons, for example, should be generally understandable. Independent of the personas’ personal knowledge, an operation should be easy to learn and understand. This also results in the acceptance of the AR end device in everyday work. In this paper, these personas are a powerful methodological tool for the requirements of analysis, design definition, and pattern evaluation.

3.2. The Background of Pattern

In 1977, Alexander et al. [42] introduced the term pattern in their publication “A Pattern Language”. For problems that occur again and again, pattern solutions, so-called patterns, can support the solution. Patterns not only describe the problem, but they also describe the core of the solutions. These can then be reproduced infinitely [42]. These views were also supported by Mahemoff and Johnston in 1998 [43]. They saw patterns as a compromise for examining design alternatives for their suitability. Competing options can be considered to focus on the problem [43]. Similarly, van Duyen et al. [44] commented on this issue. Every solution also has opposing forces that need to be addressed. In this context, these forces can be seen as different needs and constraints. The patterns should show the advantages and disadvantages of each alternative solution and serve as decision support [44].

Patterns do not represent fixed regulations or specifications that restrict a development. They are intended to serve as tested suggestions for finding solutions to recurring problems in the development of user interfaces for AR systems in an industrial context and to inspire them. Each pattern can be flexibly transferred to other application areas according to the described solution [45]. For easy and clear manageability, the patterns should have the same shape. Each pattern solution should contain a picture as well as a description. In this regard, both the problem and the solution should be described in more detail so that it is apparent how the pattern can be helpful. The solution may include instructions on how to apply the pattern. Proof of validity is often provided by solutions proving themselves over time in everyday use. Since there is a high need for new technologies to have design quality early on, usability testing is used to empirically prove their worth [42].

Kunert [45] showed in his dissertation that most developers of a user interface need certain information in a pattern. Furthermore, Kunert [45] dealt with the structure of patterns. In a study with UI designers, not only the relevant requirements were discussed, but also the structure of the patterns. In terms of content, the UI designers specified that the identification and integration of patterns should be described as part of the design process. Furthermore, a discussion and justification of the design alternatives should be made. For a uniform and clear presentation, the patterns should be written in table form. According to Kunert, this allows UI designers to get a direct overview of which layout problems the patterns describe and which alternative solutions are proposed. For the catalog with patterns of the AR system, the elicited template from Kunert’s dissertation is used, which deals with concrete problems [45].

Table 6 shows the description categories, such as problem, solution, proof, and potential, which proved to be helpful for the developers.

Table 6.

Structure of the pattern.

3.3. The Creations of Pattern

The creation of the patterns is determined based on two questions:

- Which core work tasks are performed in the production environment with AR glasses?

- Which core structures do the UIs of existing layout solutions on the market have?

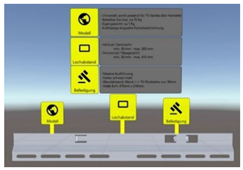

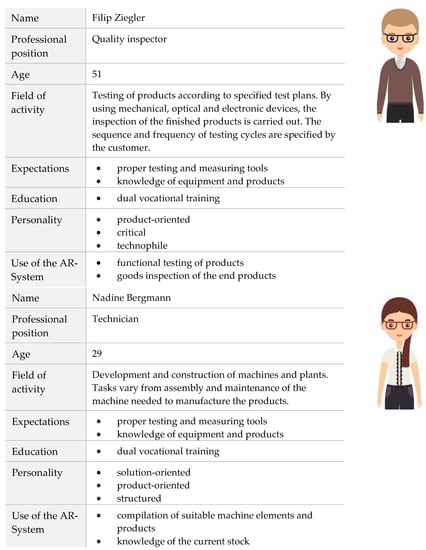

Patterns are to be extracted for the production environment based on the previously mentioned personas. The product life phases in which AR can be used range from product planning, design and manufacturing to assembly and use [4,46]. Figure 2 shows the systematic as well as the results of the task and interaction analysis conducted with all target groups following the personas.

Figure 2.

Representations of prototypical tasks in an AR system [3,47].

First, the generic tasks that are present in the use of AR in the product life phases were extracted:

- Selecting from the menu: The complex industrial content is prepared in a work-situated manner via entry points.

- Navigating documents: Manufacturing documents or assembly instructions are generally long documents with an average number of pages of about 20–30 DIN A4 pages.

- Deepening object information: Additional information is offered for the work objects in the real world.

- Selecting from the toolbar: Basic functions are arranged here, such as minimize, maximize, back, close, help, save, which are frequently used.

From these generic tasks, following Bowman et al. [10], the basic interactions were extracted that occur in every dialog:

- Position: The cursor is moved to buttons, such as toolbars.

- Select: The desired button is selected, and the system indicates the selection with an appropriate marker.

- Confirm: The input confirms the selection.

The selection of these actions seems limited, but it is exactly the lowest common denominator of the interactions that the named personas perform. They thus provide a stable, generic starting point for the differentiation of further interactions.

The study on the evaluation of layout variants in AR systems is based on an empirical investigation with best practice variants that have already been successfully established on the market. The goal is to extract proven solutions and describe them in patterns. The analysis of existing systems serves as a basis for further investigation and implementation. Four data glasses producers were considered for the study [41]. Microsoft HoloLens 1 and Daqri are representatives of glasses already found in manufacturing and industrial applications. Meta 2 and Magic Leap One are used in the consumer sector [41]. The heterogeneity of the layout makes it difficult to decide on an implementation variant for industrial use. This leads to testing the current possibilities among each other. The following table shows the different layout and interaction structures that were formed from the analysis of the manufacturers, which will be examined in more detail below.

The layout variants form possible variations for design options. As an example, Table 7 shows an example of a design of the main menu. Here, three variants (tile, list, circle) are examined with respect to gesture input and interaction by focus. The method of usability testing with a high number of test subjects is chosen. The test subjects correspond to the user profiles—the persona. The test task includes the generic basic interactions. For evaluation, the usability measures and the measure of usefulness are examined.

Table 7.

Generic tasks that are examined in the study.

DIN EN ISO 9241-11 defines usability as “the extent to which a product can be used by specific users in a specific context of used to achieve specific goals effectively, efficiently, and satisfactorily.” [48] The AR system is thus used by users in the context of the work task in an industrial environment. To determine whether the goal of user-friendliness is achieved, the usability measures are taken as an aid. In this context, the three terms are defined by ISO standard 9241-11 [48]:

- Effectiveness.

- Efficiency.

- Satisfaction.

By separating the product life phases into generic tasks and basic interactions, the individual steps to be performed with the AR system become clear. Figure 2 (see page 11) illustrates the four tasks that are generically applicable to all six product life phases. For example, “selecting from menu” is extracted. This task is relevant for the user to access the available options via the main menu. Furthermore, it must be possible to call up additional information of the objects as well as the function bar. Finally, “navigating in documents” is relevant so that the user can carry all documents with him/her and access them at any time. All generic tasks contain the basic interactions of positioning and selecting with the cursor and the subsequent confirmation of the input.

The derivation of these basic interactions from the generic tasks were used as test tasks for the evaluation of the layout variants. For the design of the layout variants, existing data glasses layouts were considered to consider all design components for high usability and usefulness.

The study on the evaluation of layout variants in AR systems was based on an empirical investigation. The goal was to extract proven solutions and describe them in patterns. The layout variants formed possible variants for design options. The method of usability testing with a high number of test persons was chosen. The test persons corresponded to the personas (Section 3.1) and were all from the industrial environment.

4. Evaluation of the Pattern Catalog

As shown in Section 3.3, the layout variants were evaluated in a direct comparison of the usefulness measure and the usability measure for the different alternatives. Figure 2 shows the five different tasks that were performed by the test persons. For the evaluation, 50 probands from the industrial environment were selected according to the personas. Table 8 and Table 9 show the evaluation with respect to the demographic data [41]. For each of the generic tasks, several layout variants are provided, which must be evaluated in direct relation to each other. It is important whether the layout of the test task supports the respondent, how effective and efficient the presentation is and how satisfied the respondent is with it. For the interpretation of the results, and thus as a conclusion for the hypotheses, it is relevant that at least one dimension shows a significant difference. The evaluation illustrates which alternative was rated better by the 50 test persons.

Table 8.

Evaluation of demographic data.—Gender and Age.

Table 9.

Evaluation of demographic data.—Occupational specialties.

The complex industrial content is presented in a work-oriented manner via menu entry points. On average, there are about five menu options to choose from. The menu is shown to the user in the AR system at the beginning and is then hidden so that the display is available to show other content. In the course of the work process, it must then be consciously called up again. The menu options of the main menu are thus only available situationally. The different alternatives for selecting from the main menu showed that the circle display was favored over both the tile and the list. These ratings indicate that familiar representations were important to the subjects for the layout.

5. Final Catalog with Pattern

In the UI study, the individual layout variants were examined and assessed regarding the criteria of effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction as well as usability for the respective design problem. The results were summarized as a starting point for the development of the catalog with patterns for an AR interface in industry. For the study, 50 subjects from the industrial environment from different industries were interviewed [41]. The findings show that good solutions already exist for the design of certain functions and that different solutions for a problem achieve comparably good results in the evaluation. The degree of fulfillment of each criterion can range from a maximum value of 5 (exceptionally good) to a minimum value of 1 (extremely poor). The Table 10 shows the mean values (M) for each alternative. If one of the four criteria contains a value below three, the layout or interaction variant is considered critical and it is to be used with reservation. From two values below three, the variant is not included in the catalog with pattern, because they cannot be considered to be a proven sample solution.

Table 10.

Extract from the evaluation of layout variants.

This evaluation also suggests that the user interface in an industrial context should allow for multiple alternatives in both layout design and interaction. The composition of the patterns is based on these results. As described in Table 6 (see page 10), the patterns are all built according to the same pattern [41]. Table 11 shows an example of a complete pattern for the “Select from menu” layout variant list.

Table 11.

Example of a pattern: Select from menu-list.

Table 12 and Table 13 show short excerpts from the other pattern that were created in connection with the main menu. Part 1 shows the three patterns for the design of the layout and part 2 shows examples for the design of the interaction.

Table 12.

Examples from the catalog with pattern. Part 1: Variants of the layout.

Table 13.

Examples from the catalog with pattern. Part 2: Variants of interaction.

6. Discussion

The paper aims to draw attention to the importance of layout design in the industrial sector. However, this is only the first step, and investigations are still very general.

From the point of view of software technology, many further developments can still be included over the next few years. Long-term ergonomic studies are still required for the permanent use of data glasses. These can look at the effects of permanent use of the data devices in the workplace for employees and include occupational health and safety. The present paper is still general in its industrial orientation. Here, too, subsequent studies can deal more intensively with the industry-specific subtasks. Especially in the layout design, differentiation is important for the coming years so that there are explicit ways of looking at the different workflows and tasks. In addition to the layout, other interaction possibilities must always be considered. Gesture control is always developed further and here, it requires an iterative review as to which interactions are applicable in the industrial field. This paper is intended to be the initial impetus for further investigations and would like to focus on industry in the technical developments.

7. Conclusions

The background of the paper is the processing of data from Industry 4.0 in quality assurance with AR glasses. The research objective is to explore how the user interface of an AR system can be designed in an industrial environment. The goal is to create a standard on a high ergonomic level that makes it possible to create consistency between AR applications. The experiment results showed that there is no difference in the ergonomic quality of the four de facto standards on the market in terms of layout. However, in terms of interaction, focusing was preferred over gesture control. This led to the finding that the solutions on the market already have a certain ergonomic quality that has grown over time. No clear preferences could be found among users regarding the layout design. The limitations lie in reducing the information to fit the task and context. The pattern catalog is intended to serve as the first aid for developers when designing user interfaces for AR end devices in the industrial sector. Furthermore, the paper provides a starting point for future research. Recognizing decision patterns is important, which can be achieved by combining information technologies, such as business and operational intelligence.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, R.K.; writing—review & editing, H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

AssiQ Assistance system for quality monitoring; Duration: 1 May 2017 to 31 October 2019, Project funding: Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Plutz, M.; Große Böckmann, M.; Siebenkotten, P.; Schmitt, R. Smart Glasses in der Produktion: Studienbericht des Fraunhofer-Instituts für Produktionstechnologie IPT; Fraunhofer: Munich, Germany, 2016; pp. 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A.; Billinghurst, M.; Lindeman, R.W.; Swan, J.E., II. A Systematic Review of Usability Studies in Augmented Reality between 2005 and 2014. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality, Merida, Yucatan, Mexico, 19–23 September 2016; Veas, E., Langlotz, T., Martinez-Carranza, J., Grasset, R., Sugimoto, M., Eds.; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koreng, R. AR in production: Development of UI patterns. In Proceedings of the Mensch und Computer 2019 on—MuC’19, Mensch und Computer 2019, Hamburg, Germany, 8–11 September 2019; Alt, F., Bulling, A., Döring, T., Eds.; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 658–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlenspiel, K.; Meerkamm, H. Integrierte Produktentwicklung. Denkabläufe, Methodeneinsatz, Zusammenarbeit, 5th ed.; Hanser: München, Germany, 2013; pp. 312–317. [Google Scholar]

- Karl, D.E.; Soderquist, K.A.; Farhi, M.; Grant, A.H.; Pekarek Krohn, D.R.; Murphy, B.; Schneiderman, J.; Straughan, B. 2018 Augmented and Virtual Reality Survey Report: Industry Insight into the Future of AR/VR; Perkins Coie LLP: Seattle, WA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Takatsu, Y.; Saito, Y.; Shiori, Y.; Nishimura, T.; Matsushita, H. Key Points for Utilizing Digital Technologies at Manufacturing and Maintenance Sites. Fujitsu Sci. Tech. J. 2018, 54, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Billinghurst, M.; Clark, A.; Lee, G. A Survey of Augmented Reality. In Foundations and Trends® in Human–Computer Interaction; Alet Heezemans: Delft, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 8, pp. 73–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.G. Design patterns for user interface for mobile applications. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2009, 40, 1318–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oscar, D.; Magnus, H.; Anna, S. Augmented Reality Smart Glasses for Industrial Assembly Operators: A Meta-Analysis and Categorization. Adv. Transdiscipl. Eng. 2019, 9, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, D.A.; Krujiff, E.; LaViola, J.J., Jr.; Poupyrev, I. 3D User Interfaces. Theory and Practice; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 6–8, 139–181, 255–285, 313–347. [Google Scholar]

- LaViola, J.J., Jr.; Kruijff, E.; McMahan, R.P.; Bowman, D.A.; Poupyrev, I. 3D User Interfaces. Theory and Practice; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 6–8, 18–19, 144–146, 258, 255–311, 379–413, 421–451. [Google Scholar]

- DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V. Ergonomie der Mensch-System-Interaktion—Teil 110: Grundsätze der Dialoggestaltung; ICS 13.180; 35.080; 35.240.20, DIN EN ISO 9241-110; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jerald, J. The VR Book. Human-Centered Design for Virtual Reality; ACM: New York, NY, USA; San Rafael, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 441–442. [Google Scholar]

- Preim, B.; Dachselt, R. Interaktive Systeme. Band 2: User Interface Engineering, 3D-Interaktion, Natural User Interfaces, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 45–108. [Google Scholar]

- Cohé, A.; Dècle, F.; Hachet, M. tBox: A 3D Transformation Widget designed for Touch-screens: CHI’11. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011; pp. 3005–3008. [Google Scholar]

- DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V. Ergonomie der Mensch-System-Interaktion—Teil 400: Grundsätze und Anforderungen für Physikalische Eingabegeräte; DIN EN ISO 9241-400; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dörner, R.; Broll, W.; Grimm, P.; Jung, B. (Eds.) Virtual und Augmented Reality (VR/AR). Grundlagen und Methoden der Virtuellen und Augmentierten Realität; Springer Vieweg: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Endsley, M.R.; Jones, D.G. Designing for Situation Awareness. An Approach to User-Centered Design, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, W. ARVIKA-Augmented Reality for Development, Production and Service. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.194.6733&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 31 May 2017).

- Gabbard, J.L. Researching Usability Design and Evaluation Guidelines for Augmented Reality (AR) Systems. Available online: http://www.rkriz.net/sv/classes/ESM4714/Student_Proj/class00/gabbard/index.html (accessed on 31 May 2017).

- Kratz, S.; Rohs, M.; Guse, D.; Müller, J.; Bailly, G.; Nischt, M. PalmSpace: Continuous Around-Device Gestures vs. Multitouch for 3D Rotation Tasks on Mobile Devices: AVI 12. In Proceedings of the International Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces, Capri Island (Naples), Italy, 22–25 May 2012; pp. 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Reisman, J.L.; Davidson, P.L.; Han, J.Y. A Screen-Space Formulation for 2D and 3D Direct Manipulation: UIST’09. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, Victoria, BC, Canada, 4–7 October 2009; pp. 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Theis, S.; Pfendler, C.; Alexander, T.; Mertens, A.; Brandl, C.; Schlick, C.M. Head-Mounted Displays—Bedingungen des Sicheren und Beanspruchungsoptimalen Einsatzes: Physische Beanspruchung beim Einsatz von HMDs; Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin: Dortmund, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-88261-162-5. [Google Scholar]

- Aragon, C.R.; Hearst, M.A. Improving Aviation Safety with Information Visualization: A Flight Simulation Study. In Proceedings of the CHI’05: SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Portland, OR, USA, 2–7 April 2005; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V. Ergonomische Anforderungen für Bürotätigkeiten mit Bildschirmgeräten—Teil 13: Benutzerführung; DIN EN ISO 9241-13; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V. Ergonomie der Mensch-System-Interaktion—Teil 154: Sprachdialogsysteme; DIN EN ISO 9241-154; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, S.K.; Nee, A.Y.C. Virtual and Augmented Reality Applications in Manufacturing; Springer: London, UK, 2004; pp. 129–183. [Google Scholar]

- Schinke, T.; Henze, N.; Boll, S. Visualization of off-screen objects in mobile augmented reality. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Lisbon, Portugal, 7–10 September 2010; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 313–316. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, M.; Zühlke, D. Smartphones und Tablets in der industriellen Produktion: Nutzerfreundliche Bedienung von Feldgeräten. Autom. Prax. 2013, 55, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uratani, K.; Machida, T.; Kiyokawa, K.; Takemura, H. A study of depth visualization techniques for virtual annotations in augmented reality. In Proceedings of the IEEE Virtual Reality 2005, Bonn, Germany, 12–16 March 2005; Fröhlich, B., Ed.; IEEE Service Center: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diepstraten, J.; Weiskopf, D.; Ertl, T. Interactive Cutaway Illustrations. Comput. Graph. Forum 2003, 22, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V. Ergonomische Anforderungen für Bürotätigkeiten mit Bildschirmgeräten—Teil 16: Dialogführung Mittels Direkter Manipulation; DIN EN ISO 9241-16; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemian, A.M.; Riecke, B.E. Leaning-Based 360° Interfaces: Investigating Virtual Reality Navigation Interfaces with Leaning-Based-Translation and Full-Rotation. In Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality, Proceedings of the 9th International Conference, VAMR 2017, Held as Part of HCI International 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–14 July 2017; Lackey, S., Chen, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Preim, B.; Dachselt, R. Interaktive Systeme. Band 1: Grundlagen, Graphical User Interfaces, Informationsvisualisierung, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 245–281. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, C.; Waßmann, H. Wahrnehmungsgerechte Präsentati Wahrnehmungsgerechte Präsentation von Designentwürfen mit Hilfe von Augmented Reality; ViProSim-Paper; OWL ViProSim e.V.: Paderborn, Germany, 2009; pp. 405–419. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, A.; Reimann, R.; Cronin, D.; Engel, R. About face. Interface und Interaction Design; Mitp-Verlag: Heidelberg/Hamburg, Germany, 2010; pp. 77–88, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt, J.S.; Adlin, T. The Persona Lifecycle. Keeping People in Mind Throughout Product Design; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 11, 230–232. [Google Scholar]

- Miaskiewicz, T.; Kozar, K.A. Personas and user-centered design: How can personas benefit product design processes? Des. Stud. 2011, 32, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayas, C.; Hörold, S.; Krömker, H. (Eds.) Personas for Requirements Engineering. Opportunities and Challenges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Steinert, T.; Koreng, R.; Mayas, C.; Cherednychek, N.; Dohmen, C.; Hörold, S.; Krempels, K.-H.; Kehren, P. Offene Mobilitätsplattform (OMP): Teil 1: Rollenmodell & Typische Kooperationsszenarien. VDV-Schriftem 436-1; August 2019; Available online: http://docplayer.org/178259330-Vdv-schrift-2019-offene-mobilitaetsplattform-omp-teil-1-rollenmodell-typische-kooperationsszenarien.html (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Koreng, R. Entwicklung Eines Patternkatalogs für Augmented Reality Interfaces in der Industrie; Universitätsverlag Ilmenau: Ilmenau, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M.; Jacobson, M. A Pattern Language. Towns, Buildings, Construction, 41st ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. ix–xvii. [Google Scholar]

- Mahemoff, M.J.; Johnston, L.J. Principles for a usability-oriented pattern language. In Proceedings of the 1998 Australasian Computer Human Interaction Conference, OzCHI’98, Adelaide, SA, Australia, 30 November–4 December 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Duyne, D.K.; Landay, J.A.; Hong, J.I. The Design of Sites. Patterns, Principles, and Processes for Crafting a Customer-Centered Web Experience, 6th ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kunert, T. User-Centered Interaction Design Patterns for Interactive Digital Television Applications; Springer: London, UK, 2009; pp. 58–60, 142–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann, U. (Ed.) Handbuch Produktentwicklung; Hanser: München, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Koreng, R.; Krömker, H. Augmented Reality Interface: Guidelines for the Design of Contrast Ratios. In Proceedings of the ASME 2019 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Anaheim, CA, USA, 18–21 August 2019; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V. DIN EN ISO 9241-11: 2018-11, Ergonomie der Mensch-System-Interaktion_-Teil_11: Gebrauchstauglichkeit: Begriffe und Konzepte (ISO_9241-11:2018); Deutsche Fassung EN_ISO_9241-11:2018; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).