Abstract

Role-based access control (RBAC) continues to gain popularity in the management of authorization concerning access to knowledge assets in organizations. As a socio-technical concept, the notion of role in RBAC has been overemphasized, while very little attention is given to the precursors: role strain, role ambiguity, and role conflict. These constructs provide more significant insights into RBAC design in Knowledge Management Systems (KMS). KMS is the technology-based knowledge management tool used to acquire, store, share, and apply knowledge for improved collaboration and knowledge-value creation. In this paper, we propose eight propositions that require future research concerning the RBAC system for knowledge security. In addition, we propose a model that integrates these precursors and RBAC to deepen the understanding of these constructs. Further, we examine these precursory constructs in a socio-technical fashion relative to RBAC in the organizational context and the status–role relationship effects. We carried out conceptual analysis and synthesis of the relevant literature, and present a model that involves the three essential precursors that play crucial roles in role mining and engineering in RBAC design. Using an illustrative case study of two companies where 63 IT professionals participated in the study, the study established that the precursors positively and significantly increase the intractability of the RBAC system design. Our framework draws attention to both the management of organizations and RBAC system developers about the need to consider and analyze the precursors thoroughly before initiating the processes of policy engineering, role mining, and role engineering. The propositions stated in this study are important considerations for future work.

1. Introduction

Security on knowledge resources is of higher priority to most organizations. Organizations lose grip of their competitiveness when there is much disregard for knowledge security and protection. Typically, employees in organizations share knowledge through the use of KMS. KMS is defined as the technology-based knowledge management tool used to acquire, store, share, and apply knowledge for improved collaboration and knowledge-value creation. In the KMS environment, users can create, store, share, and utilize knowledge in ways that improve their job performance [1,2]. Access to knowledge resources for use or reuse requires user authentication and authorization [3]. Despite the rationale of KMS as a knowledge-sharing platform, the system has to provide security for the knowledge packages shared or transferred within the organization. Typically, organizations deploy security models in their KMS for controlling and managing knowledge resources more securely and protectively [4,5]. One such commonly deployable models are the role-based access control (RBAC) model. Though there is still a debate on the suitability of access control models in general, and RBAC in particular in KMS, the extent of restrictions on knowledge resources relates to specialized roles and the intent of a specific KMS [3]. Thus, the view of the authors suggests that security is a serious concern when considering unauthorized access to knowledge resources. As noted by [6], this level of recognition of security awareness on knowledge resources by organizations affirms the need to introduce access control policies that build trust and confidence between people and to facilitate knowledge sharing.

From an organizational perspective, roles are defined for actors to carry out specific expected behaviors that commensurate with their functions and obligations. In a social sense, roles involve interactions and set the premise for expectations that can lead to effective collaboration. Transitioning from a social context to a technical setting, [7,8] used the term “roles” to mean access privileges in the design of RBAC to curtail misuse of data stored in databases of a system. Users assigned to roles can interact with other people, devices, or software applications through clearly defined access permissions. Unlike roles used in a sociological sense, roles, as used in RBAC, are predefined but scalable and can assume different occupants. Because roles are not negotiated in a technical system, it is relatively easy to ensure that role-takers function only per that role expectations [9]. However, it is generally tedious to explicitly and sufficiently define the boundaries of role-taking or role-making because of the dynamic nature of roles as a social concept.

By the principle of RBAC, the use of roles relates to users engaging in some predefined activities given access permissions [10]. As much as roles in RBAC involve some interactions as either role owners, makers, or takers, RBAC is recognized in this paper as a socio-technical concept. The recognition of RBAC in computer-based security systems is wholly due to the dynamism in roles that make it possible to opt for separation of duty (SoD) such that role conflicts are sufficiently avoided. In a broader sense, many knowledge management (KM) initiatives address knowledge security-related problems by the direct deployment of RBAC for access restrictions on knowledge resources [11]. We emphasize that the use of this socio-technical RBAC in the KMS arena, in particular, has precursors (1) role strain, (2) role ambiguity, and (3) role conflict that influence the role mining and role engineering processes. Though these precursors are sociological or social psychological concepts [12,13], they are very critical for RBAC design and use in KMS. As a result, there is still a gap in the existing KMS literature between the deployment of RBAC as an access control measure and the potential role stressors (i.e., the precursors) that complicate RBAC design, particularly on role definitions for user assignments. Having reviewed past studies, it is necessary to discuss both the social and technical perspectives of RBAC and the transitional effects of the precursors on RBAC. Moreover, the issues about these precursors originate from the nature of the organizational structure in which traditional roles associated with statuses can complicate the technical design of RBAC. The idea of role in RBAC policy in knowledge management initiatives still lacks a comprehensible, socio-technical, theoretical foundation to provide a firm empirical application. Thus, this paper examines these precursors of the socio-technical RBAC and contributes to an enriched understanding of RBAC design guidelines. Considering information systems (IS) and KMS literature from past studies, we provide in this study a precursory socio-technical RBAC model. We further state that this article focuses on the effect that these precursory factors can have on the design of RBAC.

Our paper is organized as follows. Section two gives the method or approach to this study. Section three discusses related works, while section four explains the socio-technical perspective of RBAC. Section five gives an insight into the precursors of RBAC. Section six presents an illustrative case study. Section seven discusses the implications of the study, and section eight gives the conclusions of the study.

2. Methods

Several works have documented the deployment of RBAC as a network security tool for systems in organizations. From the core RBAC developed by [10] to the many extensions presented in the works such as [8,14,15], RBAC continues to gain much recognition in IS/KMS literature. Our conceptual framework draws on cross fields of research such as strategic management, sociology, social psychology, systems theory, role theory, policy analysis, and engineering, network privacy and security, and organizational capability. We searched scholarly literature through online databases and identified these fields of study for consideration in our article. Initially, we reviewed the literature on the precursors—role strain, role ambiguity, and role conflict peculiar to the fields of sociology and psychology.

With the understanding of how these concepts interplay in social settings vis-à-vis organizational behavior, we extended the review to include role theory as applied in role engineering in the context of system’s security. Individually, articles on RBAC were scrutinized, and the concept of roles as used in RBAC design was analyzed to determine its transitional use in the technical sense. Publications that dwell on RBAC as a security control mechanism in KMS were considered useful to this study. Besides the precursors, our review considered some crucial concepts such as role mining, role engineering, policy engineering, individual status/position, governing team, and role dimensionality.

Analysis and synthesis followed the initial review. At this stage, we correctly identified articles that matter to this study. Primarily, issues related to access control models and how RBAC fits into KMS adoption were identified to aid the understanding of the technical aspect being considered. Besides, discussions on the precursors, including their dimensions, were also examined. Beyond this point, our focus shifted to analyzing only those ideas that emphasize RBAC as a socio-technical tool in KMS and how the precursors can impact the intractability of RBAC design. This approach to reviewing the literature was an in-depth one and systematically based on themes. After the review and analysis, we synthesized the role-related factors or dimensions that emerged to develop our conceptual framework provided in this study. We focused on only the key ideas concerning the dimensions of roles in either the sociological sense or technical sense or both. The attempt to bring these perspectives of roles together was to facilitate the development of a balanced approach. This clarifies RBAC as a socio-technical phenomenon in a KMS environment.

Thus, this section highlights the underlining procedure or methodological approach that aided quality outcome of the discussion on related works in Section 3. From the reviewed literature, there are relationships between the precursors on the one hand—sociological context and relationships between roles, users, and permissions, on the other hand—technical context. In this article, our conceptual framework establishes a link between the sociological context and the technical context and explores the influences that the precursors have on RBAC design. We offer a detailed discussion later in this study.

3. Related Work

3.1. Knowledge Security in Organizations

To organizations, knowledge is a critical and competitive intangible resource (e.g., [16,17,18,19]). Past studies have discussed the value of knowledge, including how and why it is essential to manage knowledge. At each stage of the knowledge management process, individuals or departments are involved in knowledge identification, capturing, storing, sharing, and utilization. In KMS literature, in particular, only a few works have attempted to write about the security consciousness of knowledge resources because of the fear of endangering the crusade for the flexible knowledge-sharing environment. Like information security, knowledge security is so crucial that much more effort is required by organizations to define a secure knowledge trajectory for improved knowledge-value creation [17].

The notion of access control policies on knowledge resources is a prerequisite to controlling unauthorized access to knowledge assets. Granting access to people at different levels is one crucial mechanism supported by RBAC [20]. Most RBAC-based KMSs fail to achieve successes because of: (1) misalignment of KM initiative with the nature of deployable RBAC, (2) inappropriate user-role definitions relative to role demands of the organization, and (3) overly loaded status composition from structural and strategic policy perspectives. An important question that remains not answered in KMS literature is, “How do firms secure knowledge assets and at the same time promote knowledge sharing among people across different functional areas?” The challenge for KMS designers and practitioners lies in the kind of balanced approach that can effectively address issues relating to security capability and knowledge sharing. The two contrasting perspectives stem from isolating the technical concerns of RBAC from their social counterparts. Situations where the prior design of RBAC is seriously examined and considered as a socio-technical entity, its deployment in a KMS strategic initiative mostly yields positive results [21]. Thus, we argue that security consciousness is also cognitively related and that individuals’ understanding of security in the arena of knowledge sharing in an organization is essential.

To curtail the misuse and unauthorized access to knowledge assets, there is the need to institutionalize permission constraints through RBAC to ensure the integrity of the knowledge repository. In practice, business dynamics (both internal and external) sometimes tend to affect planned behaviors of individuals ascribed to specific roles in the organization. One important aspect that our study examines is the socio-technical notion of RBAC. Typically, in the IS/KMS literature, more attention has been given to the technical considerations of RBAC than the social contexts of it. Thus, we first discuss the technical context of RBAC and later dwell on the social elements and their relationships that facilitate RBAC design.

3.2. Overview of the Technical RBAC

The role-based access control (RBAC) model is a security control mechanism used to restrict both authorized and unauthorized users’ access to organizational intangible assets [22]. In respect of corporate assets, access to knowledge resources requires some level of security since knowledge resources are the strategic assets of an organization [23,24,25]. The model is commonly used in many computer-based network applications, including knowledge management systems, usually used for knowledge sharing. In IS/KMS literature, the model had gained much recognition and continued to be used by many practitioners and researchers for significant security benefits.

RBAC was first proposed by [26], and the notion is that privileges are associated with roles rather than users. This understanding gives an overview of the core RBAC framework. Thus, a user (e.g., a person), a role (e.g., a job function), an operation (e.g., a mode of access), an object (e.g., a knowledge item or a data record), and a subject (e.g., an active user process) form the basic elements involved in the specification and enforcement of security policies [27]. By functional illustration, operations represent actions, and they are associated with roles. Users from the user set belong to one or more roles of the roles set. The cardinality between the user set and the role set can be a many-to-many relationship. Thus, a user of a role membership can access one or more roles, and a role can have one or more users.

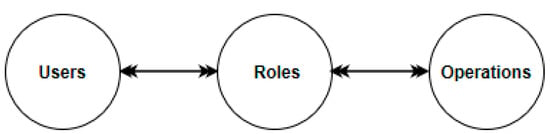

Constraints associated with operations dictate the specific actions a user belonging to a role membership can perform. For example, an “author” role may be constrained in terms of article submission. Within a session, an author may be limited to specific roles such as submitting an article for publication, tracking the status of a submitted article and responding to reviewers’ comments or suggestions. Thus, users are assigned to roles and the roles associated with operations. This simplified relationship is shown in Figure 1. In addition, in a role, there can be other roles such that a role hierarchy is identified. For a user to perform an operation on an object, the user must be authorized and admitted into that role by the security administrator, and be made active in that role.

Figure 1.

Users, roles, and operations.

From an authorization perspective, users are granted permission to become members of a role. For operations of a role, there has to be authorization so that authorized users can perform that role correctly. A session of a user is activated within a role [8]. Users are authorized to do specific operations on objects. Given this conception, role–role, role–permission, and role–user relations are paramount to specifying and enforcing access control policies. These interrelationship policies enhance administrative security capability. Technically, RBAC policies primarily border on specification and enforcement of users’ participation in roles to perform operations on objects [26].

Moreover, new users are allowed to be members of a role while membership of existing users can be revoked. Admission of new members into roles and revocation of old members is dependent on the competencies and responsibilities of users assigned to roles. Similarly, new operations can be established with existing roles, and old operations associated with some roles can be removed. While maintaining privileges, roles may be updated [20]. Thus, it is flexible to manage rights or permissions, especially in cases where there are more defined roles emerging from organizational mining.

From the basic development of the RBAC framework, several works have extended the model in ways that best fit the implementation of a particular system. For instance, Ref. [8] featured four reference models of RBAC framework, namely RBAC0 (with the entities as roles, users, sessions, and permissions), RBAC1 (RBAC0 plus role hierarchies), RBAC2 (RBAC1 plus constraints), and RBAC3 (RBAC1 plus RBAC2—symmetric RBAC). Their model further isolated administrative permissions and administration roles from regular roles and permissions. In 1997, this level of conceptualization introduced the administrative RBAC, named ARBAC97. In this sense, constraints executed as permissions are assigned to roles at the lower level, while administrative permissions are assigned purely to administrative roles at the higher level. Thus, there is a separation of the functions of access control and the security administration of RBAC.

In addition, [28] proposed the N-RBAC framework to improve the intractability of the structure of role hierarchy using namespace. Though the authors focused on local space for role hierarchy where there are independent subsidiaries, their model enhanced the decentralization of role administration. Similarly, [29] introduced the RBAC model with the novelty and granularity of decentralized administration for distributed systems. Their model emphasized local administrators as being highly responsible for dynamic assignments due to the rapid growth in group collaborations and departments. Compared with the work of [8], the authors extended RBAC3 with the notion that organizations also dynamically grow in roles, users, work teams, and departments, including their interrelationships. Thus, they exemplified their model using the Spread prototype to address authorization management issues applicable and suitable to group-based applications. In another perspective, [30] proposed a structural model consisting of data access control, access permission card, and functional operation control. These were operationalized using a multi-level authorization management approach. Moreover, [31] elaborated on the RBAC model based on the negotiation of authority between autonomous managers, and the entities involve which included security administrators, managers, role domains, and owners. Their framework reduces the centrally controlled authorization management, which is a significant drawback of the core RBAC.

In this work, we recognize the developmental transitions of RBAC over the years, especially on constraints and permission assignments enforced on authorized users for authorization management. With roles as the central construct in the core RBAC (see Figure 1) and its developmental trend, the term “roles” originated as a socially-oriented dimension. Hence, a consideration of the social context of RBAC is vital to provide an in-depth understanding of RBAC, and perhaps other future extensions of the model.

3.3. The Socio-Technical Perspectives of RBAC

Roles are derivatives of statuses defined in terms of responsibilities assigned to people to accomplish some goals. Role hierarchies follow the representations of an organizational reporting structure in which a role at a higher level can inherit lower-level roles. With this phenomenon [8,26], there are structured roles in the RBAC model as a better means to reflect the functional responsibilities and authority of an organization. In a typical organizational structure, each functional node at any level relates to another node through some functional processes. The relationship is either vertical or horizontal, depending on the predetermined flow of work or information. The structure differs from one organization to another due to variations in the types of business, policy dimensions, and strategic direction. Broadly, the representation of the structure mostly starts from senior management down the lines through middle management to supervisors and operational staff.

Naturally, the interconnectedness suggests practical interactions between individuals, departments, or units. At the basic level, work teams or groups are the primary agents of socialization, and that is the most relevant aspect of socialization in which people appreciate the perceptions of others [32]. Entities such as departments prescribed with different obligations form the secondary level of socialization. This relational perspective establishes socialization across all functional areas.

3.3.1. RBAC as a Socialization Concept

In a broader sense, an organization is an agent of socialization. Socialization, in this context, means the individual and departmental levels of interactions within an organization. According to [32], “a major agent of socialization is the workplace.” (p. 167). Besides the process of socialization, the author argues that the way that an organization preserves its existing social structure enables individuals to attain cultural competency. This viewpoint is about the functional social stratification within an organization rather than the newcomer kind of socialization [33].

Structures in an organization reflect a multi-level sub-agent of socialization [34]. For this reason, an individual’s social self can be molded through interactions with others, along with the structures. The social self thus evolves through continuous interaction with other socializing agents [35]. For example, security administrators may interact with the user community for some time about a security policy intervention, which, to a more significant extent, removes the individuality of members on either side. In this sense, members of either side are regarded as “subjects” working together towards a successful implementation of the policy outcome. Thus, people belonging to decentralized departments, units, or divisions naturally interact, and they are guided by work ethics, culture, values, structures, rules, and norms of the organization.

3.3.2. The Status–Role Relationship

A role is a sociological concept and involves interactions [36]. A role, according to [37], is “a set of expectations about behavior for a position in a social structure.” (p. 155). Statuses involve roles and rules, and these are impersonal for the reason that it does not matter who occupies the positions to execute the roles (i.e., a policy in RBAC design). For many organizations, the existing structure and processes define roles, responsibilities, and rules that establish the basis of job routines and standard operating procedures. A good organizational structure can increase commitment to role execution [38]. A status ascribed to a position in a formal organization relates to a hierarchical structure, and every position within the structure has definitive roles [39]. Role performers are obliged to fulfill some expectations and behaviors that result in quality outcomes. In sociology and social psychology, a status–role relationship is multidimensional and has both functional and structural characteristics. Thus, this study recognizes [40]’s structural role theory to deepen the understanding of the precursors premising RBAC design.

Aside from job allocation, coordination, and management, the organizational structure indicates the flow of information across levels in the organization [41]. Given this premise, the structural elements within an organization include statuses or positions anticipated to be occupied by individuals towards the achievement of corporate goals.

Ref. [42] defines status as “a position in a social system involving designated rights and obligations” (p. 110). We define status as the level of credibility, position, rank, or standing of an entity such as a person relative to others within a social group, an organization, or an ecosystem. Status is an element of social structure, and it is more relational in context [43]. It is often understood according to the occupant or incumbent. For example, the status of the Chief Security Administrator is an elevated position relative to low-level or local security administrators. A status is characterized by specific role expectations actionable through role behaviors prescribed as a set of responsibilities and duties [44]. Statuses and roles exist independently as far as their occupants or incumbents are a concern. The occupant of a status is expected to understand the position being held and the roles associated with that status. As evidenced in the work of [45], social statuses constitute role relationships that consist of role transactions. Thus, a “status” is an umbrella term consisting of multiple roles (or responsibilities and duties), and that, for every status attributed with some roles, the occupant is expected to meet certain minimal role expectations.

Role behaviors conditioned on role expectations are assigned permissions to carry out only those tasks related to the status. An example is “professor” status. In an academic institution, the professor must know that, besides teaching students, doing research is also an obligation. Thus, the professor plays the role of teaching students and doing research. The higher the level of credibility of the status, the greater the number of role expectations and behaviors [44]. Hence, a role assumes a common denominator relative to one or more role expectations. For example, in the “professor” status with the teaching role, one or more role expectations such as preparing course materials, design course assessments schemes, and using appropriate teaching methodologies may be classified as minimal role expectations for the “teaching role.” This suggests that, if the teaching role is divided into four role expectations relative to that role, then there are three role expectations out of the four. Thus, the more role expectations, the higher the number of responsibilities expected of the occupant of a status. Practically, the status–role relationship is the bedrock for effective analysis of role engineering.

In situations of status inconsistency, some tasks may not be well accomplished or may become incomplete, and this can affect the achievement of goals. For example, an incumbent of a database manager ascribed to achieve the roles of a marketing group records is likely to perform two roles. Extending traditional work roles with non-traditional ones expose the incumbent to risks of status inconsistency. Importantly, the status that an incumbent achieves may not be congruent with the status ascribed to him or her. By this notion, statuses can be combined, but the particular combination of statuses is what matters such that there is no avenue for complicating role definitions during role engineering. Within a single status, there can be multiple roles in which conflict of role performance can arise. As traditional statuses are extended to include non-traditional ones, [46] argued that the complexity of role performance increases because some role behaviors cannot be realized completely. Thus, we argue that organizations should use such mechanisms during policy engineering or organizational mining. This effort helps to (1) minimize statuses’ combinations, (2) reduce roles set for a particular status, and (3) align exact role demands of statuses with specific intent and context of institutionalizing statuses. Thus, the perception of status inconsistency affects role definitions for RBAC design, especially concerning the separation of duty.

3.3.3. Expectations and Negotiations as Elements of RBAC

A deduction of roles from statuses generates sets of expectations and negotiations. A single status can have more than one role associated with multiple expectations. From the perspective of role theory, expectations are crucial in implementing RBAC protocols. In taking roles, there are often agreements such that the technical system provides users with precisely what functions to perform [9]. The authors argued that expectations are best represented using describable relations such as inter-role expectations and systemic expectations. In a social context, both inter-role expectations and systemic expectations are purely relational. In graph representations, inter-role expectations are represented as directed graphs in which a certain role originates from another role to which it shares some common properties. Systemic expectations do not involve a role in shaping another role but rather relying on agreed-upon rules expressed logically. In a technical sense, one such rule is the SoD in RBAC design. We argue that SoD is a social concept but can be complex to formalize when the social dimensions complicate the technical representations. Hence, a “root-role” analysis must exhibit some describable granularity. In addition, it must be unique to ease its technical representation.

In organizational management, negotiations concerning roles’ development involve role assignment, role-taking, and role modification. Either of these role dimensions is realized through negotiation and, sometimes, discussion. Extending this notion in a technical sense implies that a role engineering process should embrace the opinions of all stakeholders. This must be done not only at the initial design stages of RBAC but also during modifications and additions of new roles. Such an attempt is a means to control complications that arise when there is a likelihood of role conflicts and ambiguity.

In the KMS environment, the concept of negotiation is a dynamic entity and requires strategic tools to deepen its understanding of proper roles definition and modifications. In a collaborative sense, it enhances knowledge sharing regardless of RBAC as a security measure. Moreover, it facilitates a collective conscience among individual users towards agreed-upon solutions regarding the addition of new roles [9]. In RBAC, a role may interact with another role either through inheritance in the case of role hierarchy or overlap in terms of responsibilities [10]. As explained by [47], cooperative RBAC enhanced with negotiation-based role hierarchy in a virtual environment could provide security management on multiple agent servers. The authors posited that, in a virtual role hierarchy, multiple agent servers could negotiate on flexible terms without compromising any security rule. Essentially, negotiation-based schemes lead to socialization of roles adaptable to specific contexts. We argue, therefore, that RBAC is a socio-technical access control measure, particularly in the KMS environment, and requires a balanced approach to deploy RBAC for managing knowledge resources effectively. Often, most KMSs vary in purpose, context, and content. Because of the dynamic nature of organizations influenced by external and internal factors, social perspectives leading to technical RBAC design should be of much priority to both practitioners and researchers.

3.3.4. Dimensions of Roles

Ralph Linton (in sociology) and George Herbert Mead (in social psychology) are the proponents of role theory in 1934. Role theory posits that social statuses identified in a social system involve multiple roles such that the role incumbent faces role demands that often result in role conflict [48]. A role, according to [49], refers to the sets of activities that an individual performs guided by predefined norms [45] defines a role as “a set of prescriptions defining what the behavior of a positioning member should be” (p. 29). For adequacy of role definition, [9] refers to a role as putting together all the behavioral expectations within a social system concerning the owner of a role.

In sociology and social psychology literature, various perspectives have been put forward regarding the concept of a role. Common among these perspectives are the functional, structural, organizational, symbolic interactionism, and cognitive role theories (see Table 1). For instance, in an organizational context, structural roles are defined as those roles that the organization gives to its role members based on assumed normative expectations and behaviors. The first three perspectives focus on the individual as a representative of status. The remaining two are directed towards the individual as a person. For example, knowledge-sharing platform specialists or local security administrators act on a role-play based on organizational values, norms, and culture to rightfully discharge their duties for effective knowledge management or security. Role theorists continue to introduce other dimensions and derivatives of the role concept, and these included the subjective role contexts facilitating better role focus and definitions. Such dimensions make role concept more versatile in other fields such as the semantic use of the term “role” in RBAC.

Table 1.

Role perspectives in a social system.

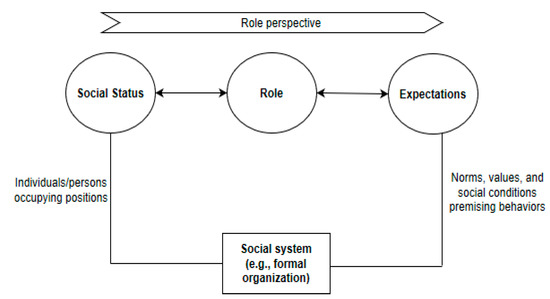

Whether structural, functional, or dramaturgical role theory, the sociological understanding of roles continues to gain stronger roots in technical systems. Essentially, the definition of a role embodies linkages from the functional perspective to cognitive theory. In a social system, individuals occupy identified positions associated with roles, and these roles have prescribed expectations which are accomplished through cognitive behaviors of the role members (see Figure 2). The expectations are expressible through norms, rights, attitudes, duties, or some behaviors. Roles thus define expectations of behaviors, but expectations are relational in context. This suggests that roles are tied typically to elements such as a position, an existing actor, a function, an individual, or one’s image. A role may be defined in terms of an element within a certain context. Thus, a propositional role theory may evolve from this fundamental understanding of roles in terms of the kinds of elements.

Figure 2.

Social status, role, and expectations.

Technically, there is a symbolic mapping between the sociological role and the term “role” in RBAC. This level of transition is visible when Figure 1 is compared with Figure 2, a situation in which similar relationships can be identified. This illustration shows the socio-technical nature of RBAC. From the perspective of access control on knowledge resources in the KMS environment, SoD is pivoted on this notion of sociological role theory. Though translating roles into technical sense can be complex sometimes, it is worth examining and essential to avoid instances of role conflicts and role ambiguity. To secure knowledge resources, for example, the term “role” as used in RBAC is a derivative of the sociological role typifying user expectations based on permission constraints. The notion of role remains a vital phenomenon not only in the studies of sociology or social psychology but also in the fields of software applications’ development and technology-based devices. To transition the ‘sociological role’ to a ‘technical role’, several other factors become relevant to ensure proper definition of roles generally in a technical sense.

Many studies have been done on RBAC design and implementation concerns in information systems, particularly in securing KMS. While some studies have been successful in securing KMSs with RBAC, others had failed to achieve such success. Today, some studies combine RBAC with blockchain technology for stronger security measures on corporate intellectual capital. For example, the works of [3,11,50,51,52] secured KMSs with RBAC. Others, like [21,53,54] saw significant challenges in using RBAC to protect intellectual assets. In addition, [55,56] enhanced RBAC with blockchain technology to protect and secure knowledge resources effectively. Thus, the innovative ways to define roles for member users for effective SoD are of high priority. An important concern evolves from inadequate examination and pre-analysis from the perspective of the precursors of RBAC. This paper recognizes the significant effects of role strain, role ambiguity, and role conflict as three important precursors of RBAC design.

4. The Precursors of RBAC

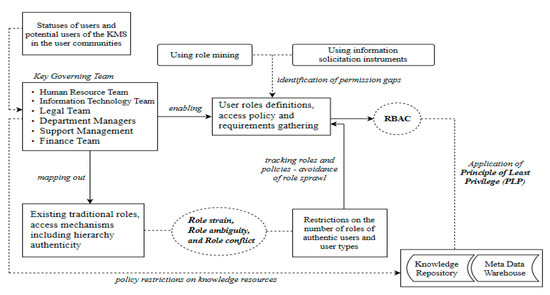

From the sociological viewpoint, role overload, role ambiguity, and role conflict precursors are the residual of status inconsistency in which more than one status implies more than one role [73]. Moreover, [74], in their study, attempted to explore instances where role conflict is similar to status inconsistency. Overlooking statuses from policy engineering perspective towards role engineering context lead to three fundamental concerns (i.e., role overload, role ambiguity, and role conflict) that complicate role engineering at the initial stages. Figure 3 shows the precursors and their relationship with the RBAC model. We thus emphasize that organizational mining processes explicate these precursors in ways that distinctively allow for appreciating the relationships among the precursors. Many works have discussed these precursors either in isolation or in combination across different disciplines, but no such works studied their antecedent role in RBAC for access control in KMS. We recognize the semantic meaning of the terms as applied in other disciplines, and extend its application in a technical sense in the RBAC system.

Figure 3.

The precursors and their relationship with the RBAC model.

4.1. Role Strain

Formerly, [75] defined role strain as “difficulty in meeting given role demands” (p. 485). The author emphasized that the sum of role obligations of an individual is generally over-demanding to the extent that managing role system for anticipated normative commitment becomes more complicated [76] refers to role strain as the discrepancy between what an individual achieves and the perceived role expectations. The author assesses how a role incumbent enacts roles through negotiation mechanisms that achieve higher role price or performance. Considering role strain in terms of probability, [32] defined role strain as “when the demands of a particular role are such that the incumbent is hard-pressed to meet them all” (p. 125). In addition, [77] defined role strain as the inconsistent demands that compel a person to experience some levels of exhaustion, tension, and burden. From organization management context, we thus refer to role strain as the sum of complications that an individual occupying a status or a position experiences when enacting a given role or a set of roles. Within a status, an incumbent is exposed to a range of roles constrained by the norms, beliefs, and values of the organization. Moreover, role strain is a function of role overload, role conflict, and role ambiguity [78]. Thus, out of strain, a person can abuse access rights which can be costly to the organization because some other roles have to be compromised. Overlooking this intricate aspect of role strain is likely to affect RBAC design.

Normative commitment and conformity by individuals assigned to specific roles entangle them to make decisions which exert strain or stress in their efforts to perform all roles. In other words, an individual occupying an identified status is challenged with conflicting demands given limited resources (e.g., time), which often lead to compromise of some role expectations. Interestingly, the nature of the social structure existing in an organization can sometimes escalate either the role set, the status set, or both. In any of the situations, individuals try to engage in negotiations (i.e., role or status bargains) to perform less for more role or status price. Thus, the interconnectedness of institutional structures vis-à-vis role relationships (role networks) inherently sets forth stress resulting from role demands and obligations [59].

The definition of status can present tricky scenarios when roles associated with statuses seem to cause either role conflict or role strain. However, the flip-side argument for role enhancement encourages firms to overlook status accumulation. For positive outcomes, [79] posited that a person occupying more than one role within a status benefits from status security, social prestige, control over resources for status enrichment, and self-gratification. If there are two distinct statuses with each having its role set, then role conflict can arise—inter-role conflict. In addition, if two related statuses are classified as a single status such that each has a separate role set, then role strain occurs as there are opposing role demands. By this premise, a role engineering process that aims at providing an effective RBAC system has to initiate mining techniques from statuses rather than isolating them despite the significant emphasis placed on roles. We argue that the more complex the statuses set, the higher the degree of role demands that are likely to cripple role definitions and further complicate permission constraints during RBAC design. Organizations prefer systems that offer the best security functions for much comfort, trust, suitability, and, above all, increase performance. Status mining approaches are prerequisites to role mining or role-engineering techniques. Over concentration on role mining methods tend to relegate the status engineering process, which affects the social perspective of RBAC systems.

In the KMS context, a person may assume more than one status. To deploy and enforce any access control measure with the RBAC system, it is not sufficient to assign a status to only one person without considering the overall status set of the person. This attribution can sometimes be tricky as a person may be assumed to possess only one status and abuse privileges, for example, an investor, a financial analyst, and a stockbroker of a company. In this case, the status set has three elements, and each element has an associated set of roles. Suppose there are more defined roles for each element in the analyst–investor–broker status, roles might oppose other roles and create role tension within that status set. Thus, regardless of the role-engineering optimization method supported by cardinality and user-oriented exclusive constraints [80], role strain is likely to occur and complicate the RBAC system. Hence, it is appropriate to consider SoD from the status context through an optimized status engineering method that can reduce the knottiness of RBAC design.

4.2. Role Ambiguity

Role ambiguity is the situation where there is a lack of adequate information about the demands of a role, and the role occupant does not know how to fulfill those demands [81]. As regards an individual’s behavior towards a role enactment, [65] refers to role ambiguity as a situation in which the individual is faced with incomplete role expectations. According to [75], role ambiguity is the state in which the role incumbent lacks sufficient or complete expectations to guide actual behavior. In addition, [82,83] refer to role ambiguity as the unclear expectations which make the role incumbent uncertain about what ought to be done. Moreover, [37] defines role ambiguity in terms of predictable outcomes, given the inputs from the environment to guide one’s behavior. Primarily, role ambiguity emphasizes a lack of clarity about roles, which often distracts the role-taker as to what exactly to do regarding role performance. Thus, role ambiguity is a critical factor in the design of the RBAC system.

Users in an organization perform various functions and responsibilities. In executing the role engineering process for the RBAC system, role expectations of users must reflect as accurately as possible those functions or duties. If within a single status, there are multiple roles such that two or more roles may overlap to create ambiguous role expectations, then unclear and unstable role assignments to users can occur. Role ambiguity can manifest in the uncertainty of role selection. The effect is that the choice of roles for user-permission assignments become more problematic [84] illustrated that role selection for each user-permission assignment must reduce the level of ambiguity so that roles are managed effectively. The authors posited that it is best to reduce (or, if possible, eliminate) role-selection ambiguity involved in managing user-permission assignments. In addition, useful and efficient algorithms can help identify all candidate roles that exhibit features of ambiguity. We argue, therefore, that, first, role ambiguity must be tackled from policy and functional perspectives so that the use of optimized role-mining techniques can minimize the number of expected role–user assignments and, second, improve the administration effort of the RBAC system.

4.3. Role Conflict

Role conflict, in a sociological context, is a structural condition and can destabilize the formal structure of an organization. Conflicts among roles occur when there are competing expectations for resources such as time and energy of the role incumbent [65] defines role conflict as “the concurrent appearance of two or more incompatible expectations for the behavior of a person (p. 82). While [32] refers to role conflict as a clash between actual demands of roles, [83] rather defined role conflict as the extent of the inappropriateness of role expectations. Similarly, when roles contradict one another and occur simultaneously, [82] expresses such contradictory expectations as role conflict because they hinder completion of tasks of the role incumbent. Role conflicts may be inbound (i.e., within the same status) or outbound (i.e., across a combination of statuses). As identified by [85], inter-role conflict, person-role conflict, intra-sender conflict, and inter-sender conflict are some of the essential forms of conflict that characterize behavioral requirements of roles. It is thus important to examine these concepts thoroughly during the role engineering process.

Further, [37] saw role conflict as the dimensions of consistency-inconsistency found in the behavioral requirements of a role. The authors also explained that a violation of either the principle of unity of command or chain of command could cause role conflicts in an organization. Thus, there is a multiplicity of factors that can lead to conflicting roles within the organization, and these may include conflicting policies, standards, instructions, processes, and structures. In any instance that one of these exerts pressures of congruency-incongruency of role expectation, role conflict occurs.

Technically, one major priority of the RBAC system is to resolve conflicting roles faced by organizations both explicitly and implicitly for efficient security management of corporate knowledge assets. When defined roles are not harmonized well, there is role malintegration, or a user of a role faces many role expectations or responsibilities—role overload [37,75], the intricacies of role interactions require efficient, optimization role-mining techniques to achieve successful role–permission assignments. As more users become role members, the role network widens with an increasing number of permissions. To manage permissions effectively, users must be assigned to the right roles devoid of conflicts. Thus, there have to be mutually exclusive roles such that local administrators can do the delegation and decentralization of user-role assignments without any fear of security breach. Given this principle, permission constraints are used as checks on abuse of privileges. Therefore, if role conflicts are eliminated or reduced from organization management’s perspective, it becomes easier for the RBAC designer to tailor system requirements appropriately with specific role demands.

In effect, a critical examination of the precursors enables RBAC system developers to better understand the status–role relationship from the perspective of organization management. Contrarily, if the management of organizations ensure that statuses together with their role expectations are unambiguous and non-conflicting, there is the possibility of no greater complications in the separation of duty policy for the RBAC model. Moreover, role mining and role engineering are important elements of the RBAC model, and they can be very costly when there are multiple iterations in these processes for secured KMS. Thus, we argue that status set analysis is imperative to ensure clear role definitions and to necessitate uncomplicated RBAC design.

5. Description of the Proposed Integrative Model

Statuses assigned to users within an organization are a reflection of the functional structure of the organization. Senior management and other functional leaders (i.e., key governing team) occupy positions associated with critical responsibilities. The governing team maps out and defines authentic, traditional roles assigned to users to accomplish job performance. The team helps to address issues relating to policy restrictions concerning authorization management of the knowledge repository. From an organizational management viewpoint, the key governing team premises role definitions in terms of role expectations and establishes policies and procedures on access to knowledge resources. This effort facilitates the technical design and implementation of access control policies on knowledge assets. By this understanding, the processes of role mining and information solicitation can help to identify permission gaps for efficient permission-constraint assignments. In addition, norms, culture, and practices within a formal organization sometimes lead to status inconsistency, which further leads to ambiguous or conflicting roles. Thus, role strain, role ambiguity, and role conflict become important antecedents to RBAC design, and will require effective separation of duties during role engineering process. If roles are analyzed from this perspective, there is a greater chance of avoiding role sprawl unnecessarily. Hence, in KMS environment, the socio-technical perspective of RBAC design is an essential consideration for successful deployment of RBAC system. A detailed description of the model is provided below.

Statuses of users in user community: Statuses have varying perceptual weights, and the stronger the conviction and credibility for a particular status, the higher the degree of role expectations and role behaviors [43,44]. This explains why some statuses are accompanied by very demanding roles in the KMS environment. For example, top management and functional leaders of the governing team occupy statuses that have higher role demands, which include mapping out roles, determining policy restrictions on knowledge assets, and defining role expectations of users. In an organizational setting, users of KMS occupy statuses, and each role occupant has a defined set of role expectations.

Key Governing Team: The governing team comprises of the primary internal stakeholders responsible for ensuring effective and efficient implementation of the organization’s strategies aimed at sustaining the competitiveness of the business. Typically, in most formal organizations, the governing team maps out the existing traditional roles and determine the access control mechanisms on corporate intellectual assets. Such access mechanisms sometimes may or may not follow the principle of chain of command. In this regard, the governing team helps in formulating rules and policy guidelines for what ought to be done by whom and how it must be done. By policy, we mean both objective (e.g., password policy) and subjective (e.g., senior management’s policy on specialized access privilege) implementation protocols. Thus, statuses associated with roles stand to be the by-products of the policy engineering process operationalized by the governing team.

Traditional roles and access mechanisms: Traditional roles refer to the built-in roles aligned with statuses within the formal structures and processes of an organization [44]. They are the ascriptive roles based on typical traditional policies and culture of an organization [86]. These roles are mostly laden with inconsistencies emerging from statuses defined through organizational structure or hierarchy. For example, roles defined for a systems administrator’s position may be ambiguous or functionally related to those of the network administrator. If similar instances are enshrined in most positions, designers of RBAC are expected to be extra careful about the kind of access control mechanisms to deploy. This suggests that the right access control mechanisms have to be employed to ensure that only verified and authorized users can access the knowledge assets. However, if it is not recognized early or poorly done, user permissions can undergo several modifications which can result in system inefficiency likely to affect overall security quality.

User role definitions and access policies: Curtailing role definitions from policy engineering context enables RBAC designers to streamline all role definitions. To facilitate the role engineering process, requirements are gathered to meet job functions which are in tandem with organizational system policy. This suggests that the governing team is responsible for affirming the definition of roles prior to the process of RBAC design. This attempt helps to enhance role engineering process to achieve the expected quality design. Thus, the RBAC practitioner finds it relatively easier to execute SoD. At this point, management can be certain about what to expect from the system because RBAC design process considers what roles exist in the organization.

Restrictions on user roles: Restricting the number of roles to only verified and authorized users in a technical manner complements management’s effort to control access rights. However, the nature of the behavioral requirements of traditional roles is mostly identified to contain multiplicity of roles, unclear role definitions, and conflicting roles. As explained by [87], it is appropriate to optimize the roles sets so that only authentic users are assigned permissions to use the system. The effects of role ambiguity, role conflict, or role strain can influence the user of a role to abuse access rights. In the context of traditional roles and the restrictions on the number of roles influenced by these precursors in one way or the other, it is expedient to track roles and policies that may lead to any role sprawl that can further worsen future RBAC modifications. This suggests that role–permission assignments for the RBAC system can be implemented consensually and effectively if these elements are well examined in the design phase.

Role mining and information solicitation: In user-knowledge resource mapping, the right user-permission assignments are based on information concerning job characteristics, competency, responsibility, and authority. Role mining and the use of suitable information solicitation instruments become so essential to identify permission gaps for effective and efficient authorization management. Thus, providing solutions to identified gaps increases system security quality.

Knowledge repository: A knowledge repository is the location where knowledge-based information is stored, organized, and retrieved for use or reuse. For example, a cloud-based storage facility can be used to store all relevant knowledge across an organization in different geographical regions. With the deployment of KMS as an enhanced knowledge management strategy, organizations institutionalize policy restrictions on knowledge resources as a means to restrain the abuse of privileges. This effort is meant to secure and protect the knowledge repository. Thus, the RBAC system in KMS helps to achieve the required access control level for security management. The description of these important aspects of the model is also shown in Figure 3.

From the discussion, we argue that roles and statuses are social concepts, and separation of duty must take its root from examining the nature of roles and statuses prior to RBAC design and implementation. Knowing the status in general, and understanding the role expectations in particular, enable any incumbent of status to execute role behaviors appropriately. Thus, an organization mining process must consider identifying and minimizing overlapping role expectations associated with statuses to reduce the intractability of SoD during RBAC design. In the existing KMS literature, many of the studies focused on roles, their users, and permissions regarding RBAC, but very little is studied on statuses that contain the roles. Hence, this study draws attention to the status concept during organizational mining and policy engineering.

6. An Illustrative Case Study

In this section, we present a case study to illustrate the relevance of the proposed model by considering two companies in Ghana. SoftCity Technologies Limited and theSOFTtribe Limited are two well established information technology (IT) service provision firms that offer software and security-related solutions to most private and public knowledge-based enterprises in Ghana. Services provided include knowledge management systems, general software development, computer security, Web Application development, Networking, Multimedia, ICT training, and Virtual IT platforms. In recent years, these companies had partnered other giant foreign firms such as Microsoft in the delivery of standard quality software and security products and services to Ghana and beyond.

With vast experience in the design and implementation of software development including access control policies, both companies are operational in RBAC design for enterprises that needed to secure their knowledge assets in KMS environment. Given the constraints of the nature of traditional roles existing in most organizations, IT professionals find it quite challenging to speedily and flexibly design RBAC systems that suit the numerous system requirements of many of the enterprises, especially in the KMS environment. Despite this challenge, knowledge assets still need to be well protected and secured to sustain the competitiveness of enterprises that deploy RBAC as part of their knowledge management strategies. Thus, it is relevant to consider the status–role relationship and the kind of conflicts, ambiguities, and strains that are observed to affect RBAC system design.

A questionnaire was used to solicit the opinions of IT professionals engaged in the numerous activities of KMS and RBAC system design, development, and implementation about the effects of the precursors on RBAC design (see Appendix A). The items in the questionnaire focused on role conflict, role ambiguity, and role strain and their effect on RBAC design. Out of 100 questionnaires sent through email system, 63 were received representing a response rate of 63%. Ref. [88]’s measures for the constructs were adopted and modified in KMS context. All the items were on a five-point Likert scale anchored between 1—strongly disagree to 5—strongly agree. Collected data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 23. For internal consistency reliability of the items, Cronbach’s α of 0.759 was obtained, which is good because α greater than or equal to 0.70 is acceptable as evidenced by [89]. As part of the analysis, we performed correlation and multiple regression analysis to examine the effects of the precursors on RBAC design.

Results and Discussion

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the respondents considered for this empirical illustration. Out of the 63 respondents, 11 were females and 52 were males representing 17.46% and 82.54%, respectively. Obviously, males engage in more technology-based professions than females can be perhaps due to the technical and challenging nature of such professions. This partly supports the study by [4], which found among the IT professionals 35 (68.6%) males and 16 (31.4%) females that used KMS (i.e., Developer’s Corner) secured with RBAC. In terms of work experience, a total of 48 (76.19%) had acquired experience between 1 to 6 years, which indicates familiarity with enterprises they offer various IT-based solutions such as RBAC-KMS.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics.

Furthermore, correlation and multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between RBAC design and the precursors. Table 3 shows the ANOVA results and the values obtained for the Mean Square, F-value, and Significant value are 9.239, 15.929, and 0.000, respectively. Table 4 depicts the means, medians, and standard deviations of the items used to measure the constructs. In addition, Table 5 shows the model summary where the R2 and the Adjusted R2 values are 0.448 and 0.419, respectively. Thus, Table 6 presents summary of results consisting of the means, standard deviations, correlations, and regression coefficients.

Table 3.

ANOVA.

Table 4.

Statistics of questionnaire items.

Table 5.

Summary of model results.

Table 6.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and coefficients.

It is clear from Table 6 that each of the precursors: RConf, RAmbi, and RStrn positively and significantly correlated with RBAC design. This indicates that the complications in these precursors increase the difficulty in the RBAC design. Moreover, the multiple regression model with all three predictors produced R2 = 0.419, F (3, 59) = 15.929, and p < 0.001. This means that RConf, RAmbi, and RStrn had positive and significant regression weights, and hence indicate that the precursors are expected to increase the difficulty in RBAC design in KMS.

It is important to emphasize that complications in these precursors are themselves stressors which indirectly affect the RBAC designer for secured KMS. This finding is consistent with the work of [90] which found that role ambiguity and role strain can lead to technostress when there are inconsistencies in roles and statuses to a larger extent that it affects technology design and implementation. Thus, RBAC design for secured KMS cannot be examined ordinarily and directly from mere user roles and permission assignments but must evolve from status–role relationships where these precursors are more pronounced.

Role expectations are defined based on the status set of the role occupant in organizational management perspective. This prominent feature of roles may not be completely formalized in a technical RBAC system because of the inherent conflicts and ambiguities in roles. Impliedly, the positive and significant correlation between the precursors and RBAC design for secured KMS suggest that it is appropriate to examine the precursors prior to role mining and role engineering activities. This finding supports the study by [9], which identified the precursors as elements of systemic expectations (e.g., informal notions and discrepancies) affecting the design of secured computer-supported collaborative learning. In addition, as seen from Table 6, RConf has a greater relative effect on RBAC design than RAmbi and RStrn, and this perhaps explains why RBAC designers are more emphatic on resolving role conflicts through separation of duties. Such studies include [7,8,10,14,15,20,22]. Thus, the concept of role in both organizational management perspective and technical context remains a crucial element in designing RBAC for secured KMS.

We argue that the findings of this illustrative example suggest that further future studies are required to address problems relating to role conflict, role ambiguity, and role strain that significantly affect the design of RBAC systems for secured KMS. To a greater extent, organizations are to be mindful of their assignment of statuses and roles so that inconsistencies or discrepancies are reduced or eliminated. In addition, resolving the complications inherent in these precursors can reduce or eliminate the technostress of RBAC designers. Thus, it takes a balance effort of both organizations and RBAC-KMS professionals involved in KM initiatives to minimize or avoid the effects of these precursors. Given this premise, this study opens up avenues for future research by outlining eight propositions concerning these precursors for consideration by both researchers and practitioners.

7. Research Implications

With the increasing extension of the RBAC model and its re-alignment with changing organizational security needs, there are vast opportunities for both practitioners and scholars to advance further and deepen the understanding of the evolution of the role concept in RBAC in terms of the precursors. A thorough review of literature in sociology, social psychology, computer security, and knowledge management that facilitated the creation of the precursory socio-technical RBAC model presented in this paper offers opportunities for future research in the following areas:

- Study related to the nature of knowledge security in organizations

- Study related to the socio-technical perspective of RBAC in KMS environment

- Study related to the precursory RBAC factors

According to [65], the term “role” remains an interesting concept among theorists, and its evolution and application by authors in newer innovative ways continue to span across various fields of research. The author posited that the role field would evolve in different contexts and domains as propositional theories in the near future. Like this paper, the idea of role in RBAC policy in knowledge management initiatives still lacks a comprehensible, socio-technical theoretical foundation to provide a firm empirical application. Today, organizational preferences, norms, beliefs, and values have effects on how RBAC policy initiatives and configurations should address corporate security management, especially in the KMS environment. Thus, the challenge to many researchers and practitioners is the ability to identify, understand, and define roles as used in RBAC correctly so that the effects of role conflict, ambiguity, or overload are significantly reduced or eliminated.

Based on the model that this paper presents and the three main study areas stated above, we thus suggest the following propositions:

Proposition 1.

The nature of knowledge security in the environment of KMS in organizations is complicated, especially across different organizations, and requires an effective policy engineering process to unearth all security-related issues for successful knowledge-sharing efforts.

Arguably, there is still a debate on the suitability of the RBAC model for secured KMS. The primary questions that continue to challenge both scholars and practitioners alike for future studies in this area are: How can the RBAC system secure and protect knowledge resources without compromising knowledge-sharing efforts within or across organizations? Will knowledge security still matter when thinking of promoting effective knowledge sharing among employees empirically?

The second area of research interest focuses on an oversimplification of RBAC as a mere technical concept, while, indeed, RBAC is a socio-technical concept. Hence, we suggest that:

Proposition 2.

The RBAC model transitions from a socially-oriented perspective to a technical context, and its adoption in KMS is subject to both perspectives regardless of the improvisation of the model.

Proposition 3.

A proper analysis of the status–role relationship provides a well-established basis for the successful role engineering process.

A balanced approach to understanding the social and technical dimensions of RBAC is inevitable to the successful integration of the RBAC system in organizational security infrastructure. The generalization of RBAC purely as a technical system makes it sometimes difficult to fit well in the KMS environment. Thus, an approach that harnesses the social dimensions of RBAC works better in the KMS domain.

The third area that offers study opportunities relates to the antecedent factors that make the RBAC system complex in both design and implementation. We thus suggest that:

Proposition 4.

Role overload, role conflict, and role ambiguity are worth examining during the role engineering process to reduce the difficulty in adopting the RBAC system.

Proposition 5.

Role strain provides a shred of evidence for a change of behavior of the role occupant towards violation of security protocol during role enactment—a situation that explains attempts by role incumbents to abuse privileges.

Proposition 6.

The precursors interplay between the traditional structural roles and RBAC’s components (i.e., role–role, role–permissions, and user-role relationships) and tracking of both roles and policies to avoid role sprawl is crucial.

It is further essential for future studies to contribute to clarifying other vital factors that affect the RBAC system, whether or not there is a technical or social predisposition in the area of KMS. We thus put forward that:

Proposition 7.

Policy restrictions on knowledge resources take a dual responsibility of both management and technical system developers.

Proposition 8.

The use of information solicitation instruments and role mining techniques is suitable for identifying permission gaps for more precise role definitions and authorization management.

For RBAC adoption, a gap remains between practice and research to the extent that the idea of role in RBAC continues to evolve as organizations significantly increase investment in technology-based KMS [69,91,92]. Extensive studies have been done on the RBAC model in terms of its application and suitability in different contexts in the IS/KMS literature. The existing studies suggest that the RBAC system is reliable in handling authorization management and the protection of knowledge assets while at the same time ensuring flexible knowledge sharing. Though we acknowledge higher security system models such as a Zero Trust security model for securing cloud-based resources and services, the use of KMS for knowledge-sharing purposes makes RBAC still viable. However, there are few instances that challenge the fittingness of the RBAC adoption in the KMS environment on the basis of inflexible knowledge sharing. By this contention, both practitioners and scholars are to cooperate, identify, and examine the effects of the precursors on RBAC adoption in KMS. Moreover, future studies could consider policy engineering approaches to facilitate role mining and role engineering techniques. In this direction, conflicting reactions, expectations, instructions, and policies could be avoided to enrich RBAC policies to promote flexible knowledge sharing [93,94].

In the RBAC framework, roles naturally represent responsibilities that reflect functional structures in organizations. As roles are associated with positions, exploratory studies in an empirical sense could reveal conflicting role demands during the role engineering process in specific contexts. Thus, as part of the limitations of this conceptual paper, the standardized items for measuring the constructs were modified to enable the assessment of the precursors in RBAC-KMS context. Future work on the outlined propositions would help identify more phenomenal issues relating to the precursors of RBAC, particularly in selected study settings. Further research could help verify whether or not the effects of the precursors cut across many organizations and the methods used could permit generalization of results. Mainly, additional studies in this area may help identify other evolving role dimensions that influence RBAC design and have not been added to the existing IS/KMS literature.

8. Conclusions

Securing knowledge assets of an organization using the RBAC system is quite sophisticated in the KMS environment. Extensions of RBAC may not reflect the intended restrictiveness of the model because of the inadequate assessment of the social contexts before the technical requirements. The dilemma at stake is whether or not to implement a highly restrictive access control policy without inevitably derailing the primary objective of KMS. Obviously, the sequence of role performance based on multiple role obligations causes role strain, which significantly affects RBAC design. Thus, the precursory factors of RBAC are critical to the overall role engineering process.

RBAC is a socio-technical concept and requires a balanced perspective to sufficiently examine the status–role relationship that potentially complicates role engineering and role-mining efforts. This conceptual paper presented a precursory RBAC model that describes the status–role relationship. It also identifies the precursors as influencers of RBAC design and illustrates the interconnectedness between the key governing team, the precursors, and RBAC. Thus, we contribute to IS/KMS literature by emphasizing that the social dimension of RBAC is a prerequisite to providing a much profound understanding of the role engineering process, and to ease the complexity involve in RBAC system design. Hence, our approach will be useful to both researchers and practitioners when considering RBAC adoption to mitigate security constraints in specific contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.N. and Z.Q.; methodology, Z.Q.; validation, G.N. and Z.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, G.N.; writing—review and editing, G.N. and Z.Q.; supervision, Z.Q.; investigation, G.N.; and funding acquisition, Z.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the NSFC-Guangdong Joint Fund (Grant No. U1401257), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 61300090, 61133016, and 61272527), science and technology plan projects in Sichuan Province (Grant No. 2014JY0172) and the opening project of Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Electronic Information Products Reliability Technology (Grant No. 2013A061401003).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RBAC | Role-Based Access Control |

| KMS | Knowledge Management System |

| KM | Knowledge Management |

| SoD | Separation of Duty |

| IS | Information Systems |

| IT | Information Technology |

| RConf | Role conflict |

| RAmbi | Role ambiguity |

| SPSS | Package for the Social Sciences |

Appendix A

Measurement Items

| Role conflict I find conflicting roles of most employees to complicate RBAC design. I find conflicting tasks of most employees to complicate RBAC design. I find competing role demands of most employees to complicate RBAC design. Role ambiguity Incompatible jobs of most employees affect the design of RBAC Ambiguous roles of most employees make it difficult during RBAC design. Unclear role expectations of most employees are a challenge to RBAC design. Lack of adequate information about most employees’ roles affect RBAC design. Role strain Role strain leading to exhaustion, tension, and burden complicate RBAC design process. Most employees abuse access rights out of strain which further complicate RBAC design. Most employees are hard-pressed to meet all their role demands, which complicate RBAC design. RBAC design Role conflict, role ambiguity, and role strain complicate the overall design of RBAC. Conflicting roles, unclear role expectations, and tension to meet all role demands further complicate RBAC design. |

| Note: A 5-point Likert type scale was used to measure all items and they were anchored 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. |

References

- Alavi, M.; Leidner, D.E. Review: Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Q. 2001, 27, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Knowledge Management System Use and Job Performance: A Multilevel Contingency Model. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 811–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, N.; Daniels, T. Special issue on secure knowledge management. Inf. Syst. Front. 2007, 9, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, C.; Woon, I.M.Y.; Kankanhalli, A. Impact of Security Measures on the Usefulness of Knowledge Management Systems. In Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems; NUS Publisher: Bangkok, Thailand, 7–10 July 2005; pp. 529–542. [Google Scholar]

- Safa, N.S.; Von Solms, R. An information security knowledge sharing model in organizations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 57, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabion, L.; Nazari, N.; Bandarchi, M.; Farashiani, A.; Haddad, S. Knowledge sharing mechanisms in virtual communities: A review of the current literature and recommendations for future research. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2019, 38, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraiolo, D.F.; Barkley, J.F.; Kuhn, D.R. A role-based access control model and reference implementation within a corporate intranet. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. 1999, 2, 34–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, R.S.; Coyne, E.J.; Feinstein, H.L.; Youman, C.E. Computer role-based access control models. Computer 1996, 29, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, I.; Ritterskamp, C.; Herrmann, T. Sociotechnical roles for sociotechnical systems—A perspective from social and computer sciences. In AAAI Fall Symposium—Technical Report; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraiolo, D.; Cugini, J.; Kuhn, D.R. Role-based access control (RBAC): Features and motivations. In Proceedings of the 11th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 11–15 December 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Bakar, A.; Abdullah, R. A framework of secure KMS with RBAC implementation. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2015, 10, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Van Sell, M.; Brief, A.P.; Schuler, R.S. Role Conflict and Role Ambiguity: Integration of the Literature and Directions for Future Research. Hum. Relat. 1981, 34, 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]