Abstract

The physical conquest of European powers on the rest of the world for the imposition of an accumulation of wealth monopoly and the destruction of native societies remains the foundation of the current global economy. Despite concepts of human flourishing, a term connected to empowerment that acts as an architectural structure within the development and sustainability discourse, the destruction of our planet and collective human wellbeing is not at the forefront of international political agendas. Scholars argue that the development agenda is maldevelopment due to the unrequested interventions delivered to communities, mainly in the Global South. Thus, despite the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the implementation of inner dimensions that facilitate empowerment and are an integral part of development is missing from these sophisticated global frameworks. This research article repositions empowerment and compassion at the centre of the sustainable development discourse by drawing on the Inner Development Framework, particularly goal one—Being—‘Relationship to Self’ and goal three—Relating—‘Caring for others and the World’ and the Capabilities Theory as a guiding theoretical underpinning. On this basis, this article presents a qualitative interpretative study that examines the lived experience of women and their journeys to empowerment. The key findings indicate an intricate relationship between wellbeing and empowerment and the realisation of inner development as a tool to re-imagine alternative futures. In addition, industries are profiteering from a sustainability and development agenda that is failing to address the disablement of communities by a paternalistic approach to empowerment.

1. Introduction

Despite the rise and expansion of technological development, humans remain in a perpetual state of conflict with each other and the planet [1]. The plague of uneven development has surged from a chronically ill social and economic system that, through colonial projects, has marginalised communities and rendered rural and indigenous women vulnerable [2]. The power of ‘othering’, which at its core is the ability to shape a narrative of division between each other, ourselves, and the planet, has seeped into mainstream development and sustainability approaches. In this same vein, the ownership of empowerment and what empowerment is are contested debates [3]. Inner Development draws on Goal 1, Being: Relationship to Self and Inner Development 3, Relating: Caring for others and the World, as part of the theoretical framework for this article. Concepts of compassion are compromised daily by the neoliberal agenda [4,5,6,7]. As part of the ethnographic accounts of the women in this study, my study reveals that the women in this study are already empowered. Thus, empowerment is an inner process of realisation, or better put, a journey of ‘becoming’ beyond the prerequisites of being formally educated or formally employed to be recognised as such [8]. To bestow empowerment through the participation of development programmes primarily designed to aid women in the Global South, mostly by Western interventions, has failed to integrate communities as equal partners. Equally important is the ability to learn from pragmatic approaches to sustainability and philosophies promoting oneness despite marginalisation [8]. Within this individualistic ideology that has shaped much of our approaches to education, health, and sustainability, complex ecosystems are being driven to the brink of extinction, equally putting the wellbeing of humans in peril. The link between climate change and human health is gaining interest. The impact of unhealthy environments, like pollution, pesticides in our food, and soil degradation, to name a few, expose the colonisation of the mind. And within this disorientation, empowerment becomes a crucial paradigm to re-imagine and create alternative futures. Understanding empowerment from the ontological and epistemological experiences of the key stakeholders in this study resists the paternalistic approach to development policies that have taken ownership of what empowerment means to women in its multidimensional form [9]. Similarly, despite the many forums that advocate for sustainability and development within the boundaries of planetary health, progress has been slow, partly due to the dominant neoliberal policies that leave communities and the planet in fragile circumstances [1].

By examining the relationship between sustainability and inner development, this article proposes an alternative paradigm of empowerment to cultivate human development and planetary health. Traditional knowledge systems and approaches have the same relevance as Western mainstream approaches yet are side-lined despite representing knowledges to achieve sustainable development solutions. Women from an uneven development context from the Global South and indigenous communities hold more than mere wisdom [10]. The good intentions of aid workers, health professionals, and teachers shape the narrative around an uncontested assumption that marginalised women and affected communities are devout of empowerment. In this, the political, economic, cultural, and environmental factors that create vulnerable settings and proliferate uneven development are misconstrued as states of disempowerment [11], legitimising a colonial approach to agenda setting within development and sustainability. The racism and discrimination against non-mainstream pedagogical approaches are evident in universal terms like knowledge and science, commonly used to legitimise a singularity in epistemology, whilst there is, in fact, knowledges and sciences that are yet to be understood and applied as solutions to modern challenges like disasters and conflicts that are increasing in complexity and magnitude [10]. This research article draws on women’s narratives from the Global South to elicit the core qualities of empowerment from their lived experiences that are fundamental to reshaping current approaches to sustainable development processes.

The strict confines of professionalism suffocate mainstream institutions, including the caring professions, and as a result, presence, care, and mutual collaboration become inefficient in an economic system that values profit over wellbeing [12]. Similarly, this same outward approach is present in mainstream sustainability and development as it, too, is within a needs–service economy. The dependency of services signal to systems that disable community to perpetuate need and erode self-governance and sovereignty, hence the vulnerability labels and separation between educated and uneducated, skilled, and unskilled [13,14,15,16].

The poor examination of power imbalances within sustainability and development has become an accepted status quo propped up by modernity’s philosophy that human worth can be commoditised, similar to education, care, and health [10,13,14,15,16]. In order to challenge policymakers, the humanitarian industry, academics, and development practitioners to rethink mainstream approaches and seek more compassionate paradigms, disabling definitions of empowerment need to be replaced by an inner development approach. Currently, there remains a monopoly of Western approaches to sustainability and development that is encroaching on alternative paradigms; for example, the hard stance taken by small-scale farmers, environmental activists, and indigenous groups to boycott the UN food summit over agendas that protected agro-businesses’ interests over ecological preservation highlights the citizenship in these social groups and an uncolonised mind that demonstrates a push-back on this monopoly [17]. Resistance and civil disobedience to what was deemed a form of ‘corporate colonization’ is an act of empowerment that contradicts the broad brushstrokes of vulnerability that paint affected communities by powerful development agendas [8,17,18]. Sustainability is the foundation for today’s leading global framework, the SDGs for 2023. Attention should be paid to definitions and the language adopted within these discourses as this sets the scope of policy and impact. Sustainable development is defined as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’ This broad definition misses the opportunity to explicitly outline core concepts of sustainability that can reverse the extractive methods within the current economic system and thus missing indigenous principles and codes of ethics that promote reciprocity [19]. The definition addresses human needs without setting boundaries on greed and excess, “Earth provides enough to satisfy every [hu]man’s needs, but not every man’s greed” Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1944). In this, there is no commitment to re-imagining sustainability. The absence of explicit consideration of planetary health cements its vagueness and, more critically, puts into question the credibility and relevance of a Western-led sustainable agenda when, to this day, the colonial legacy and history of extractive policies continue to play into current world affairs.

In the name of sustainable transport solutions and modernisation, one million displaced Congolese, driven by a thriving tech industry dependent on the cobalt mines of the Democratic Republic of the Congo for its $484.8 billion smartphone industry and a projected $858 billion electric car sector by 2027, are being plundered [20]. A critical discussion point is that, like in the case of the Congo, the plundering of its resources supports a Western-led ‘sustainable’ agenda with little to no benefit to local communities. Zambia is another case study that has a rich Copperbelt region, yet despite its rich resources, there is a 60 per cent illiteracy rate amongst the children in the region working the mines [2]. Such rampant examples delineate the distorted link between development and sustainability within the current economic landscape. These case studies showcase the exploitation and marginalisation of specific social groups that are the result of a discriminative system that was never built to provide freedoms to all. The application of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international legal frameworks on humanitarian law and human rights law states the right to life for all. However, at best, international law has become an aspiration [21]. The deliberate departure by many, including the vagaries of Western liberalism, calls into question the applicability of primarily externally focused systems. The blatant disregard for some lives is seen in the disproportionate burden placed on the Global South that is in the forefront of the climate crisis.

In many ways, modern society has been conditioned to normalise high levels of violence. Fanon [22] argues that external violence represents a more profound internal conflict within ourselves. The normalisation of deprivation sustains industries that profit from suffering and misery [23]. Machiavellianism, similar to colonialism, possesses a cunningness and ability to manipulate and benefit from the misery of others for its economic gain. Undeniably so, the current sustainable development agenda, rooted in a neoliberal capitalist system, can only bring about exploitation and depravation [9]. As argued by Kleinman [24] (p. 101).

“There are routinised forms of suffering that are either shared aspects of human conditions—chronic illness or death—or experiences of deprivation and exploitation and degradation and oppression that certain categories of individuals (the poor, the vulnerable, the defeated) are especially exposed to and others relatively protected from”.

2. Materials and Methods

This study examined the pedagogical approaches that facilitated the empowerment of women from an uneven development context. In accordance with the problematic applicability of sustainability, this study aims to examine modern philosophies and ancient wisdoms that outline the qualities of empowerment from the lived experience of women. The guiding philosophical underpinnings of this study took on a critical and emancipatory stance in line with indigenous, critical, and liberatory methodologies [25]. The overarching research question is as follows: What is the experience of empowerment through education for women in an uneven development context? The interest of this research question is that it facilitates an inquiry into missing concepts of resistance, self-determination, and empowerment from non-Western women that remain uncolonised in a geo-political ecosystem that breeds dependency and disablement that has ultimately shaped our relationship with each other and our approaches to planetary health. The methodological framework uses a qualitative research design, a three-method process of (1) an ethnographic account of seeking empowerment through education, (2) a participant observation of a virtual community, and (3) key informant, semi-structured interviews. The methodological framework draws from various methodologies, methods, and theories, breaking away from the strict confines of Western scientific protocol [26,27]. The interview texts were analysed through grounded theory, thematic analysis, interpretative phenomenological analysis, and a gonzo journalist analysis. Therefore, the three-method process provides a systematic rigour to the research led by a question-driven approach instead of a method-driven one [28,29].

2.1. Data Collection

The data collection uses three sets of group participants that were informed by the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Table 1. Purposeful sampling was used to identify and select information-rich cases [30]. This study only includes female participants, with no exception to race, sexuality, religious beliefs, or ethnicity, who have broad experience working with women’s empowerment and a diverse set of educational experiences and activities from various regions in the Global South. The first of the methods is an autoethnographic account of the lives of the author, grandmother, and mother, followed by two-stage virtual meetings with ten key stakeholders, and the final method of the third method process is an observer participation of a feminist humanitarian network of thirty female members that represent either INGOs, NGOs, or women’s rights groups over a four-month period. The key stakeholders have experienced poverty, discrimination, war, and displacement in different degrees. This is relevant to the findings and overall discussion, as mainstream ideals on empowerment would suggest that these are vulnerable women that need empowerment. In the anarchist vein, notions of neutrality and objectivity are contested, particularly when imparting a feminist lens. Feminist researchers argue that objectivity is a mere appearance, and ‘neutrality’ harbours a politicised position in itself [31]. This study took on this particular research design to close the gap between researcher and participant. The three-method process dispels these invisible power dynamics, responding to the key stakeholders as both women and as a researcher. The different modalities in this study provided the opportunity for the observation of different settings, dynamics, experiences, and demographics. Observation is a fundamental method running deep within the three-method process of all three stages of the methods. When delving into the different sets of ethnographies, learning is an intrinsic part of these stories. What we are taught both in school and out of school, how we learn to deal with and process challenges, is what ultimately determines who we ‘become’ and how we understand empowerment. Due to COVID-19, the interviews were carried out remotely using Zoom. All of the interviews in the second method process were recorded and transcribed; the same process was followed with the main questions asked to all participants. The semi-structured nature of the interviews and observation of the virtual community facilitated a deep exploration into what empowerment and wellbeing mean from the lived experience of women. Compassion, inclusivity, oneness, and self-governance were amongst the emerging themes that characterise empowerment. In addition, the sincerity of these engagements sheds light on the commonalities that link women to women.

Table 1.

Key themes (author’s own).

Emerging Themes through Thematic Analysis

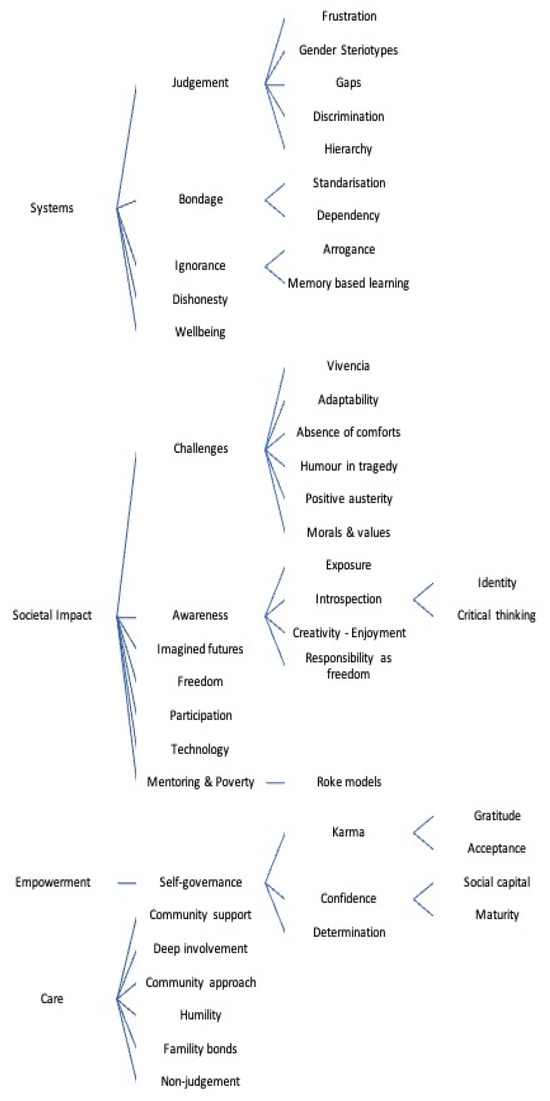

The themes that emerged through thematic analysis identified patterns within the rich data set [32]. The immersion into the anthropological narratives of the three-method process gave the flexibility to listen deeply and accommodate questioning more specific to the particular social, cultural, political, geographical, and religious context of the key stakeholders in all three of the methods, bringing a phenomenological lens to ethnography [33]. The four overarching themes are as follows:

- Systems;

- Societal Impact;

- Empowerment;

- Care.

These are followed by 17 sub-themes and 36 codes. The data analysed do not provide definitions for the themes identified; rather, this study looks at an intricate descriptive narration of a dependent co-arising set of experiences as depicted in Buddhist thought, contrary to the Western notion of causality [27]. From the broad range of ethnographies, challenges and suffering were important themes that underpinned many of the experiences of the key stakeholders. The thick ties of care found in relating to others were closely linked to feelings of empowerment that dispelled notions of individualism.

The key stakeholders’ range of experiences within their empowerment journeys were closely interlinked with education within the broadest of terms. The wisdom of family members and cultural practices, both positive and negative, allowed them to develop an awareness of who they were and what they needed out of a system to get ahead. Despite our main institutions, like education, health, and governance, excluding the knowledges from the Global South to legitimise Western science as ‘science’ in its singularity, mounting anthropocentric world views are perpetuating the deteriorating state of planetary health [9]. The findings from the data analysed showed that there is not an inherent deficit of empowerment within women from marginalised backgrounds, but instead, governing structures and, to a degree, development programmes perpetuate vulnerability. The ability to recognise the many thousands of peasants and indigenous women in science, traditional healthcare practices, governance, soil scientists, ethnobotany specialists, water managers, and plant breeders is the systematic racism and discrimination that facilitates solutions from tech giants and multinational chemical companies that are principled on destruction and capital rather than the preservation of life [34,35]. If to be considered empowered, one must be only formally educated and, or part of mainstream politics, the range of community organisations and civil defence people like the white helmets, the women from the Chipko movement, the Indian farmers, and Colombia’s working-class communities that resist oppression are mistakenly discussed as being devout of empowerment [36]. Thus, key solutions and approaches to peace and reconciliation remain in the shadows of mainstream sustainability and development agendas.

The first of the themes, as shown in Figure 1, ‘Systems’, is found within all data sets and is an essential component of the key stakeholders’ ethnography. At its core, the experience of systems by the key stakeholders was discussed as hierarchal, both within formal and strict cultural norms that prevented freedom of Being. The underpinning of the themes is freedom—what is the freedom to be? To express oneself? To connect and be a part of a more expansive sense of identity? The disabling of people and communities through the continuous growth of service economies is a commodification of these basic capabilities that restrict relations with ourselves, others, and the planet.

Figure 1.

Inductive thematic coding (Source: author’s own).

3. Results

The findings and analysis of the data have exposed the frustration and illusion of care presented within bureaucratic structures. Here are some key findings.

3.1. Imagining Alternative Futures

The key stakeholders created their own identity through their experience of challenges and suffering, understanding that there was wisdom within the depths of misery:

“Now, having worked in Syria, like at the borders and seeing a lot of families, and reflecting on what she did, I don’t know how she was that resilient. I didn’t understand until today, and then, how you make things simple as a child, and maybe she did not know all the fancy words of mental health and social integration and this and that, and maybe she had this wisdom and knowledge that maybe comes with disasters and that I don’t think they teach in schools. I think there is some sort of knowledge that is not explicit that comes with misery”(Key stakeholder account)

The creative power in the unknown, in which there is freedom to create, was a key finding supported by other scholars who examined the effects of those living through suffering [18]. The uncolonised mind emerges from the pits of chaos that saw many of the key stakeholders flee from war, divorce, stigmatisation, and poverty:

“I sometimes resent it; also, I sometimes think, “Why did you do that?” but when I analyse it now, I realise that is what made us tough’’(Key stakeholder account)

“So later, I realised that was not the problem, because at first, that was a challenging situation. And during that time, when my mother died, of course, I grew up with my aunty, that’s why I had to go to school late, and no, I would do the housework while her children went to school. That’s how I came to grow old beyond class age… that would haunt me: why am I doing this, I am supposed to be at school, but I am not. I would be blaming maybe it was because I was an orphan and didn’t have a mother; all of those [thoughts] as you go, you find other people with different situations, even those with mothers and fathers who have everything. And then you say ah no, that is not the cause: maybe that’s pre-planned, and of course, I am a Christian(Key stakeholder account)

In turn, empowerment is discussed as an intrinsically intimate process that embarks on family and community instead of a self-serving individualistic economic betterment. The inclusivity attributed to empowerment unravelled the personhood in connection with nature. Their ability to connect demonstrates a greater consciousness and sense of ‘Becoming’. Therefore, the political fictions that dominate mainstream discussions on sustainability and development are grounded on the epistemological assumption of nature as external, objectified in theory, propagate the superhero, the self-made man, and the self-sufficient pioneer as ideals negating the essentiality of human interactions of care [1,37].

The power to define ourselves and recreate relationships based on compassion indicates that empowerment is a journey of realisation of the interconnectedness [36]. Thus, creative expression is a form of civil disobedience. The ability to think critically and challenge the status quo is epistemic disobedience that leads to processes of freedom [38]. The resistance demonstrated by peasants, indigenous, and marginalised women is similar to the non-violent movements that unshackled entire communities. Gandhi argued that his ability to take India to independence was made possible by ‘experiments’ in living [39] (p. 2). The current streamlining approach that has reduced mainstream education into primarily a memorising and repeating process acts as a tool that restricts creative expression [38].

3.2. Inner Development

Central to the re-imagining of alternative futures, is the unfolding of one’s personhood—the broad brushstrokes that form a sense of becoming. The absence of a mainstream inner development approach within frameworks of sustainability and development is an implicit finding within this study. The key stakeholders emphasise the importance of community, care, and inner processes as a cornerstone in their journey to empowerment. Whilst education is discussed as at times unhelpful with regard to empowerment:

“So, I think maybe I was. The whole structure in Syria… it was more of like schools were not something nice, it was very… more like military, like a lot of discipline. This is how everything in Syria was actually. It was all imposed by the Syrian regime at that time. For example, you have to only wear black socks; even your socks had to be a certain colour, even actually our uniform was. It looked more like military; it was a dark green, so it was more like military than a school, but still, I think…”(Key stakeholder account)

“Now, having worked in Syria, like at the borders and seeing a lot of families, and reflecting on what she did, I don’t know how she was that resilient. I didn’t understand until today, and then, how you make things simple as a child and maybe she did not know all the fancy words of mental health and social integration and this and that, and maybe she had this wisdom and knowledge that maybe comes with disasters and that I don’t think they teach in schools. I think there is some sort of knowledge that is not explicit that comes with misery”(Key stakeholder account)

From the results, the key stakeholders all experienced taking more control of their lives through exposure and lived experiences:

“Personally, for me, it’s to do anything I want, say anything I want, to make a difference because, in my personal life, I don’t even have to speak about empowerment, from my father to my husband to my son. I’m always a little bit feminist, and I don’t feel a need to prove anything because I know I am the greatest thing to ever happen to the household: that’s a joke, but you know what I mean, but on the outside world, for me, it’s to be able to live in Sri Lanka, not to be scared to speak, to give my opinion, and to be recognised. I mean empowerment doesn’t only come from within, but from the people around you and how they deal with you, and I feel really empowered when I speak with people, when I deliver a lecture, or when I’m at a social gathering. For example, last week, we went out with a bunch of lawyers, and I felt really empowered because the men were in a very patriarchal profession but would listen to my opinion and seek my opinion, and that’s empowerment for me. I feel very powerful”(Key stakeholder account)

Within the diverse settings and the distinct geographical, religious, political, and economic backgrounds of the key stakeholders, self-governance was an underlining theme understood as freedom. An important distinction must be made between understanding freedom as devout of discipline. Instead, from a phenomenological lens, freedom is the mastery of self-creation that draws on discipline, determination, and perseverance. Exercising compassion and inclusivity requires discipline and living in awareness. Creating safe spaces and reflection was also an important finding within the data set. A particular pedagogical approach was contemplation as a method to induce awareness. Being still in thought allows our True Self to unravel as a path of freedom [40].

From a health and wellbeing lens, empowerment is discussed as taking back control of their lives. In different ways, the key stakeholders navigated institutional structures and had their health compromised by either stress, unfulfillment, or discrimination. From a Hindu and Buddhist lens, this is Samsara—the protracted delusion of the mind/the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth [41] (p. 250), commonly known as the ’rat race’ [42]. At the core of the key stakeholder engagement, the findings show the inextricable connections between self-governance, empowerment, and wellbeing:

“Well, we have a medicine industry here that is very interested in pain and disease; this is a fact, and there is an industry around pain, a very big industry around pain everywhere, and even an industry around disaster.”(Key stakeholder account.)

The above poignant extract unmasks the fiction of care in healthcare professions [14,24,37,43]. The extract indirectly applies to the commercialisation and acquisition of women’s agency [8,14]. In the analysis of this extract, the key stakeholders demonstrate an awareness or a ‘knowing’ regarding the structures that engulf them personally and professionally.

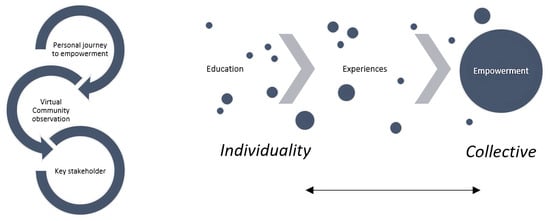

3.3. Navigating the Unknown

The key findings on societal structures and cultural norms that imposed constricting rules preventing the exploration of self-development and the enhancement of capabilities were found to be oppressive. The data analysis drew on Marxist, feminist, and indigenous theories to reveal the disabling nature of market-driven economies for those operating within these systems [8]. The findings further showed the key stakeholders oscillated between acting collectively and individually within different aspects of their lives, as shown in Figure 2. For example, one of the key stakeholders in her professional life had to adapt to a calculated, individualistic manner whilst, in her family setting, her South African familial dynamics of collectivism were in stark contrast to her working world. The key stakeholders, when discussing the various challenges and suffering, did not discuss this with resentment.

Figure 2.

Understanding collectiveness and individualism (Source: author’s own).

In many of the cultures and traditions of the key stakeholders that come from the Global South, death, for example, was accepted and merged in their cultural norms with common proverbs like Ayni—‘Hoy por ti, mañana por mí’—which means today for you and tomorrow for me, wisdoms that acknowledge life as uncertain and dangerous [7]. Thus, the key findings showed that joy, peace, and empowerment were internal qualities that, despite the challenges experienced, the key stakeholders were able to enjoy and persevere as best they could. In addition, through thematic analysis, what emerged was the dialectical play between suffering and self-governance. Another interesting observation is meaningful ‘choices’ demonstrated by the key stakeholders within their decision-making. At the core are determination, resistance, and adaptability without anaesthetising the discomfort of self-reflection. One of the commonalities within the results was from external circumstances, and that challenges are born beyond anyone’s control. Thus, it is through an independent co-arising of joy and suffering that learning and commonalities emerge [27,42]. However, how one responds to these external circumstances draws on the individual’s morals and values. The absence of internal approaches in modern industrial societies has resulted in an over-dependence on external frameworks that are failing to teach people how to be happy and healthy. The glue that brings communities together has faded in the drive to individualism, and from the findings, care and compassion were central to the empowerment of the key stakeholders and their lived experience of the phenomena.

4. Discussion

The Internal Development Goals are important theoretical underpinnings within the overall discussion of this article and enrich the analysis of the data gathered by the semi-structured interviews with ten women key stakeholders, one virtual community, and an autoethnographic account of the author’s life and narratives of her mother and grandmother. To define empowerment would be to perpetuate the disabling approach that modern agencies adopt in their development programmes [36]. The Chipko movement by the rural women in India who belonged to the Bishnois community began over 300 years ago. Chipko, which means to hug in Hindi, saw women sacrificing their lives to save their sacred Kherji trees by clinging to them. It is within these narratives of women from all walks of life that demonstrate that empowerment surges from all diverse settings [8]. The fundamental linkage between women’s empowerment from rural and indigenous backgrounds is their largely uncolonised minds and their relation to nature [36]. There remains a reluctance to accept the status quo of a state of separateness [1]. Therefore, returning to the feminine principle that embarks on all that is oneness, regeneration, and reciprocity paves the way for a methodological pathway to reconcile humanity with each other and the planet [8].

At the forefront of this critical examination of sustainable development is an absence of inner development as an integral part of modern approaches, which contributes to the dehumanisation of affected communities [38]. The alternative paradigm proposed in this research article is that empowerment paradigms rooted in reciprocity, compassion, inclusivity, and self-governance shift the current trend of external approaches to integrative world views and actions accessible through inner development. In the same vein, the pathway to reaching the Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 (SDG) favours development actors over a mobilisation of communities; this is notable in the language of the SDGs that fail to harness the empowerment of populations, framing the goals as noble causes replicating language and objectives of humanitarian actors over the everyday resistance of communities surviving disasters and crisis [44,45]. SDG No. 2, ’Zero hunger’, is morally sane but nonetheless a by-product of the immorality of capital accumulation in the dominant neoliberal economic architecture that destabilises communities and principles of sovereignty [46]. The creation of the SDGs comes from a legacy of failed attempts by Western powers to bring sustainability, peace, and compassion to modern society without addressing the deprivation and systematic oppression from extractive practices shouldered by the Global South [2]. Sustainability, as a relatively new term within the development lexicon, is evolving and, to some degree or other, has influenced the direction of development commonly framed as economic progress. Greater global awareness and scientific research from the international community are adding to the pressure on governments and global market economies to address conflicting practices pushing planetary health beyond the hope of recovery. Consequently, wellbeing is a condition from which only a few benefit.

The multi-dysfunctionality in global approaches to address modern challenges like the current education crisis, the climate crisis, and the rise in humanitarian issues has excluded the principle of femininity that encumbers a reckoning that we and nature are not separate [36]. Discussing carbon emissions and greenhouse gases is vital in understanding the climate crisis. However, more emphasis needs to be placed on the adverse impact currently experienced by countries rich in natural resources that sit in the low ranks of the Human Development Index (HDI) [47]. It is not a coincidence within this statistical analysis that links to coloniality have prevented a local and meaningful reimagination of alternative futures since these countries gained independence. Modern neoliberal capitalist systems are shaping the agendas that govern sustainability. Sustainability’s negative trade-offs are shouldered by communities already affected by routinised suffering [24]. The current state of disorientation discussed in this article refers to the social dynamics of violence that tinge on both internal and external relations, impacting society at large.

It is, therefore, no coincidence that peace is a rare state in modern society. One can argue that peace is shifting in meaning and is being re-defined as an absence of armed conflict [48]. The common application of peace is a negotiation between warring parties. For example, Angola’s extended history of war between 1992 and 1994, which saw over 300,000 deaths, provides a poignant example of the preferred short-term resolutions of negotiated agreements that quickly crumble that paved the way for indiscriminate violence [49]. The question is whether peace can be negotiated or if it is a process of reconciliation facilitated by principles of inner development. Within a humanitarian lens, peace has been commoditised to terms of agreement, leaving the root issues unaddressed. The current state of wars and failed mediations support the presumption that to establish long-lasting peace and not simply the absence of armed conflict, the internal violence within ourselves needs to be addressed through inner development. With only 26 days of peace experienced globally since World War II, following the creation of the United Nations, there lies a disconnect between development that should arise from the enhancement of human capabilities [9]. The standard approach to Human Development relies heavily on benchmarks, targets, and indicators from various international bodies that dictate progress, usually within economic standards. Thus, there is a need to ignite a discussion on an alternative paradigm that draws on non-missionary notions of compassion when rethinking sustainability.

Discussions that involve empowerment are intrinsically ontological pursuits to understanding one’s personhood [50].

5. Conclusions

This article promotes empowerment as an alternative paradigm to facilitate health and wellbeing and to better understand women’s and girls’ empowerment from an uneven development context. The uncontested assumptions around external empowerment and its interlinkage to schools and jobs restricted the multidimensionality of empowerment from an internal perspective. The research findings are ethnographies that take the reader through the empowerment journeys of the key stakeholders. In many ways, understanding empowerment from women from marginalised and rural experiences is a form of political activism against the European and North American metric that asserts women’s formal participation in the marketplace. This article provides a critical focus on issues of coloniality and modernity of knowledge monopoly regarding empowerment, wellbeing, and education through its enquiry into uneven development. In conclusion, the development discourse is a neo-colonial project, despite its complex global reach and ethos for human flourishing [8,51]. The development and sustainability discourse too readily debilitate the role of women in decision-making from crisis-affected rural and indigenous communities, imposing a vulnerability paradigm. Although there are precarious and vulnerable settings that perpetuate both the physical, cultural, and epistemic displacement of these social groups, one must address the root disruptors of peace [11]. The drive to empower women through mainstream development programmes is premised on false assumptions of a deficit of empowerment [8]. Rather, empowerment is an internal quality, and the conversation needs to shift to address the disproportionate shouldering of misery that is being maintained by illegal deforestation and multinational fossil fuel projects that deepen planetary and human health concerns. Concepts of conscientisation, empowerment, and peace are internal processes that need to be facilitated by internal frameworks materialising in critical expressions that form alternative futures principled on wellbeing. The fundamental issue is not to control challenges and suffering as they belong to life’s landscape, but rather, how can one expand human flourishing in all of life’s uncertainties, remembering that much like a vessel, we may think because we are seated in different compartments, we are navigating alone, the actuality is we share each other, and this planet; thus, the vessel is all our homes collectively.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy considerations.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Smith, N. Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space; Blackwell: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Prashad, V. Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism; Barat, F., Ed.; Haymarket Books: Chicago, IL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z. Empowerment in a socialist egalitarian agenda: Minority women in China’s higher education system. Gend. Educ. 2011, 23, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawickrama, J. Humanitarian Aid System Is a Continuation of the Colonial Project. Al Jazeera. 24 February 2018. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2018/2/24/humanitarian-aid-system-is-acontinuation-of-the-colonial-project (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Jayawickrama, J. “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together”: Outsiders learning from insiders in a humanitarian context. Interdiscip. J. Partnersh. Stud. 2018, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawickrama, J. If they can’t do any good, they shouldn’t come’: Northern evaluators in southern realities. J. Peacebuilding Dev. 2013, 1, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, A. What Really Matters: Living a Moral Life Amidst Uncertainty and Danger; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shiva, V. Staying Alive: Women, Ecology, and Development; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Page, N. and Czuba, C.E. Empowerment: What is it? J. Ext. 1991, 37, 3–9. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ594508#:~:text=Journal%20of%20Extension%20%2C%20v37%20n5,SK (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Mignolo, W.D. Coloniality: The darker side of modernity. Cult. Stud. 2007, 21, 155–167. Available online: https://monoskop.org/images/a/a6/Mignolo_Walter_2009_Coloniality_The_Darker_Side_of_Modernity.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. The Force of Non-Violence: An Ethico-Political Blind; Verso: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman, A. Presence. Lancet 2017, 389, 2466–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illich, I. The Right to Useful Unemployment; Marion Boyars: London, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Illich, I. Disabling Professions; Salem, N.H., Ed.; Marion Boyars: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Illich, I. Tools for Conviviality; Marion Boyars: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Illich, I. Deschooling Society; Marion Boyars: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, J. Farmers and Rights Groups Boycott Food Summit over Big Business Links: Focus on Agro-Business rather than Ecology Has Split Groups Invited to Planned UN Conference on Hunger. The Guardian. 4 March 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/globaldevelopment/2021/mar/04/farmers-and-rights-groups-boycott-food-summit-overbig-business-links. (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Solnit, R. A Paradise Built in Hell; Penguin Random House: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerer, R.W. Braiding Sweetgrass; Penguin Book: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J. Entertainment Industry Becomes More Vocal about the Cobalt Situation in the Congo. Forbes, 15 March 2023. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/joshwilson/2023/03/15/entertainment-industry-becomes-more-vocal-about-the-cobalt-situation-in-the-congo/?sh=7e0addd4ddf3 (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Nyabola, N. International Law Matters Even When the West Abandons It. The New Humanitarian, 7 November 2023. Available online: https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/opinion/2023/11/07/international-law-matters-even-when-west-abandons-it?utm_content=buffer6028e&utm_medium=social&utm_source=linkedin.com&utm_campaign=buffer (accessed on 17 September 2023).

- Fanon, F. The Wretched of the Earth; Penguin: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh-Cummings, N. Through the Looking Glass: Coloniality and Mirroring in Localisation. Humanit. Lead. Available online: https://ojs.deakin.edu.au/index.php/thl/article/view/1693 (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Kleinman, A. Writing at the Margin: Discourse Between Anthropology and Medicine; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, M.B.E. Decolonizing research paradigms in the context of settler colonialism: An unsettling, mutual, and collaborative effort. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaak, M.; Openjuru, G.L.; Zeelen, J. Non-formal vocational education in Uganda: Practical empowerment through a workable alternative. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2013, 33, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, J. Toward a Buddhist sociology: Theories, methods, and possibilities. Am. Sociol. 2012, 43, 203–222. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12108-012-9155-4 (accessed on 23 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Yanchar, S.C.; Gantt, E.E.; Clay, S.L. On the nature of a critical methodology. Theory Psychol. 2005, 15, 27–50. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0959354305049743?journalCode=tapa (accessed on 30 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Feyerabend, P. Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge, 1st ed.; Verso Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 1975; Available online: https://monoskop.org/images/7/7e/Feyerabend_Paul_Against_Method.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Coy, M.; Smiley, C.; Tyler, M. Challenging the ‘prostitution problem’: Dissenting voices, sex buyers, and the myth of neutrality in prostitution research. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 1931–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2008, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, B.E.; Witkop, C.T.; Varpio, L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2019, 8, 90–97. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2. (accessed on 14 May 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis-Petersen, H. Farmers’ Protests in India: Why Have New Laws Caused Anger? The Guardian. [Online]. 12 February 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/12/farmers-protests-india-whylaws-caused-anger. (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Torrado, S.; Hernandez Bonilla, J.M.; Osorio, C. Las Voces de la Peor Noche de Represión de las Protestas en Colombia: ‘Esto es Una Cacería. El Pais, 4 May 2021. Available online: https://elpais.com/internacional/2021-05-04/las-voces-de-la-peor-noche-de-represion-de-las-protestas-en-colombia-esto-esuna-caceria.html (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Adler, C.M. Beyond Schools and Jobs: How Education can Empower Women and Girls to ‘‘Become’’? Ph.D. Thesis, University of York, York, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman, A. The Soul of Care; Penguin: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 2nd ed.; Herder and Herder: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, M.K. An Autobiography, or, the Story of My Experiments with Truth; Penguin Group: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vivekananda, S. The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama. 1989. Available online: https://holybooks.com/complete-works-ofswami-vivekananda/ (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Sadhguru. Karma; Harmony Books: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, A.W. Wisdom of Insecurity: A Message for an Age of Anxiety. Rider; Penguin Random House Hose Group: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lindekens, J.; Jayawickrama, J. Where is the care in caring: A polemic on medicalisation of health and humanitarianism. Interdiscip. J. Partnersh. Stud. 2019, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.C. Weapons for the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance; Yale University Press: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield, D. A critique of seven assumptions behind psychological trauma programmes in war-affected areas. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 48, 1449–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz Montemayor, L. The Trouble with the UN SDGs 2030 Global Goals. 2018. Available online: https://medium.com/@lauraom/the-trouble-with-the-unsdgs-2030-global-goals-99111a176585 (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- World Population Review. 2023. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/hdi-by-country (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Bush, K.D. The Two Faces of Education in Ethnic Conflict: Towards a Peacebuilding Education for Children; Bush, K.D., Saltarelli, D.F., Eds.; UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre: Florence, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bercovitch, J.; Simpson, L. International Mediation and the Question of Failed Peace Agreements: Improving Conflict Management and Implementation. Peace Change 2009, 35, 68–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Women and Human Development; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rodney, W. How Europe underdeveloped Africa. London, UK: Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications. 1972. Available online: https://abahlali.org/files/3295358-walter-rodney.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).