Abstract

While divine justice is central to Christian faith, theologians disagree about its nature and dimensions. This study examines Christian belief in a just world (CBJW) as a psychological belief system through which Christian believers construe justice in the world by referring to God’s Justice. Drawing on the psychological concept of belief in a just world, which emphasizes deservedness, we develop and validate a measure of CBJW. In the pilot study, 34 items were selected from biblical texts with the help of an expert review. In Study 1, exploratory factor analysis supported a four-factor solution—God’s Punishment, Reward, Sovereignty, and Forgiveness—yielding a 27-item scale. A confirmatory factor analysis indicated good fit, and internal consistency was strong. These results suggest that CBJW functionally overlaps with secular BJW in its emphasis on reward and punishment while adding theologically distinctive dimensions of sovereignty and forgiveness. Moreover, in Christian belief, justice is construed as distinct from divine love and is oriented toward an eschatological horizon, thereby differentiating CBJW from secular conceptions of justice.

1. Introduction

This article examines the features of Christian belief in a just world (CBJW) from a psychometric perspective. Considering long-standing debates over the nature and dimensions of divine justice within Christianity, we draw on the social-psychological construct belief in a just world (BJW) to probe how Christians psychologically construe justice in the world through their beliefs about God’s justice. As established by Lerner (1965, 1970, 1980), BJW is a psychological orientation in which individuals assume that people generally get what they deserve and deserve what happens to them. Although it is often a protective illusion, BJW can also help people make sense of innocent suffering.

Because deservedness is central to many biblical portrayals of retributive justice, we developed a measurement of Christian belief in a just world (CBJW) grounded in texts that emphasize accountability and rectification. The final item set and its dimensional structure illuminate key features of Christian belief in a just world.

Notably, although the dimensions identified in the present study are labeled with reference to divine attributes, the construct under investigation is not a theological account of God’s justice but a psychological account of believers’ representations of divine justice. In this sense, CBJW captures how Christian believers organize beliefs about justice in the world by referencing God’s actions, authority, and moral order. Such representation functions analogously to secular BJW by providing expectations of deserved outcomes, even though their content is explicitly theological.

Two brief reviews frame the present study: (1) BJW and its measurement and (2) theological discussions of divine justice.

1.1. Belief in a Just World and Its Measurement

In his initial research, Lerner used BJW to explain people’s seeming “indifference” to victims of injustice, including those who suffer from poverty or illness (Lerner 1965, 1970, 1980; Lerner and Miller 1978). According to Lerner, when confronted with the suffering of innocent victims, people attempt to restore justice in one of two ways: either by compensating the victim or by persuading themselves that the victim somehow deserves their suffering. The latter tendency is central to the just-world belief. Lerner further proposed that the psychological development of BJW unfolds in three stages. In the first stage, children adopt what Piaget called “immanent justice,” which is the belief that transgression automatically brings punishment (Lerner 1980, p. 15). In the second stage, as people mature, they discover that the world is not consistently just: erring individuals may prosper, for example. In the third stage, however, because BJW is so “central a part in the organization of the human experience,” the child’s belief in a world of “immanent justice” is not abandoned but rather modified to another form, “the unassailable assumptions of ‘ultimate justice’” (Lerner 1980, p. 26).

Since the publication of Lerner’s foundational work, research on BJW has advanced in multiple directions. A major line of BJW research has focused on self-report scales (Furnham 1998). Rubin and Peplau (1973, 1975) introduced an early comprehensive measure spanning domains such as health, family, school, politics, and criminal justice (Rubin and Peplau 1975, p. 69). Dalbert and colleagues later proposed a general BJW scale in German (Dalbert et al. 1987) and an expanded English version (Dalbert 1999), distinguishing personal and general BJW. Lipkus (1991) introduced a global BJW measure and worked with colleagues to refine it by separating BJW-Self and BJW-Others into parallel eight-item scales (Lipkus et al. 1996). This self–other bidimensional model has been widely adopted (Bègue and Bastounis 2003; Sutton and Douglas 2005; Sutton et al. 2017) and converges with Dalbert’s personal–general distinction (Chobthamkit et al. 2022).

Subsequent work added nuance. Lucas et al. (2007, 2011) differentiated between procedural and distributive justice. Researchers have also incorporated religious and cultural perspectives: White et al. (2019) developed a Karma Scale grounded in South Asian traditions, while Linhares et al. (2022a, 2022b) measured BJW using popular sayings that may resist social desirability bias, including religious aphorisms (e.g., “Live by the sword, die by the sword,” Matt 26:52; “You reap what you sow,” Gal 6:7). Relatedly, some Asian studies interpret similar sayings as karmic expressions (Duong et al. 2024). In short, whereas early BJW measures were strictly secular, newer approaches tend to draw on religious and cultural resources—providing precedent for an explicitly Christian measure.

However, our point is not that there is a functional analogy between Karma and God’s justice. Rather, our point is that these developments suggest that BJW is not confined to secular formulations but can be meaningfully expressed through culturally and religiously embedded narratives of moral causality, thereby providing a methodological precedent for an explicitly Christian operationalization of just-world belief.

1.2. Theological Discussions of Divine Justice Within Christianity

The following overview is theological, but it is not intended as a normative account of divine justice. Rather, it provides a conceptual map of the belief content that informs how Christian believers interpret justice, deservedness, and moral order in lived experience.

Simply speaking, Christian thought has oscillated between retributive and restorative emphases of divine justice. Although the traditional view asserts that Christian justice requires retributive punishment, some scholars argue for the opposite position (e.g., Wolterstorff 2011). However, it is important to note that retributive justice emphasizes deservedness more than punishment. People can easily find that the Bible contains robust retributive motifs—God rewards the righteous and punishes the wicked—not only in Deuteronomistic theology but across the canon. Such motifs presuppose deservedness. For example, Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount invokes giving each their due (Thom 2009, p. 338). Similar ideas appear in the Old Testament: “Whoever digs a pit will fall into it …” (Eccl 10:8); “The righteousness of the righteous shall be his own, and the wickedness of the wicked shall be his own” (Ezek 18:20). In this regard, retributive justice resonates with the psychological concept of BJW.

The emphasis on restorative justice complicates the picture in at least three ways, all calling for clarification. First, some construe restorative justice as God’s pardoning and restoring offenders. Yet forgiveness is commonly conditioned on repentance. For instance, the book of Isaiah states, “Zion shall be redeemed by justice, and those in her who repent, by righteousness. But rebels and sinners shall be destroyed together, and those who forsake the LORD shall be consumed” (Isa 1:27; cf. Matt 13:43). In this sense, restoration remains tied to deservedness.

Second, restorative justice can be framed eschatologically: full rectification occurs at the end of time rather than being exhausted by present outcomes (Volf 1996; Wolterstorff 2011). Thus, Paul instructs believers to defer vengeance to God, entrusting ultimate judgment to the divine (e.g., Rom 12:19: “Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave room for the wrath of God; for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord’”). This emphasis does not conflict with retribution, which also has an eschatological horizon (e.g., Rev 22:12: “See, I am coming soon; my reward is with me, to repay according to everyone’s work”).

Third, appeals to restorative justice often link divine forgiveness to mercy. For instance, it is argued that God is just and merciful at the same time because a perfectly just God can consistently spare a sinner who deserves eternal condemnation (e.g., Mann 2019). However, as noted, forgiveness is typically conditioned by repentance and cannot be taken for granted (Wiegman 2017, p. 213). Divine mercy is thus framed by divine justice.

Alongside retributive/restorative debates, biblical discourse also raises distributive and procedural concerns at various points in the canon and tradition. For example, “Let justice roll down like waters …” (Amos 5:24) addresses distributive/procedural justice, as does Isa 1:17: “Learn to do good; seek justice, rescue the oppressed, defend the orphan, plead for the widow.” Scholars note that this social–ethical dimension is especially prominent in the Old Testament (Adam 2015; Raphael 2001, p. 11). While retributive and distributive/procedural justice have different foci, they are not contradictory, as oppressors are to be punished. For instance, Paul taught that “it is indeed just of God to repay with affliction those who afflict you, and to give relief to the afflicted as well as to us” (2 Thess 1:6–7; cf. Rev 22:12; 2 Pet 2:9). In this way, retributive justice addresses distributive injustice, even if they are not identical.

1.3. Purpose of the Present Study

Building on the BJW literature reviewed above, we conceptualize CBJW as a psychologically structured belief system through which Christian believers interpret justice in the world by reference to God’s justice. We develop and validate a CBJW scale grounded in biblical texts, with the aim of clarifying the dimensions through which Christian believers construe deservedness, accountability, and ultimate rectification. Rather than offering a theological theory of divine justice, the present study provides an empirical framework for examining how Christian beliefs about God shape the believers’ just-world reasoning. Our whole study consists of two sub-studies. Some of the data from the study involves informed consent and is temporarily not fully disclosed.

2. Pilot Study: Item Selection

The pilot study selected items for the Christian belief in a just world scale (CBJWS) from biblical texts, with an assumption that Christians in general are more familiar with the Bible than with theology based on it. The item selection process proceeded in four stages.

2.1. Initial Identification (57 Biblical Passages)

A comprehensive reading of the Bible (NRSV) was conducted to identify passages explicitly referring to retributive justice. The focus was on passages rather than narratives because otherwise there would have been too many candidates, including the Eden story and flood narrative, etc. Additionally, the selection was based on the concept of retributive justice, specifically the notion of deservedness, rather than the term “justice” itself, as this term can have multiple meanings, including social justice or a relationship with God, in its Hebrew or Greek counterparts. Lastly, because Deuteronomistic Theology emphasizes retributive principles, some closely related passages were consolidated to reduce redundancy. This process yielded an initial pool of 57 passages.

2.2. Refinement (45 Biblical Passages)

The initial list was narrowed to 45 passages by removing near-duplicate passages from the same biblical book and excluding those focused primarily on legal justice (e.g., lex talionis formulas such as “eye for eye, tooth for tooth”). These 45 passages were then classified into three conceptual categories: (a) Christian general belief in a just world (20 items), (b) Christian belief in a just world for self (13 items), and (c) Christian belief in a just world for others (12 items). The former category is based on some passages that deal with humanity in general, and the latter two correspond to the bidimensional model of BJW.

2.3. Simplification (36 Statements)

To improve clarity and readability, the 45 passages were paraphrased into concise statements with the aid of the Simple English Bible and consultation with a native English speaker, who is also a Christian and an elementary school English teacher. This step involved reducing the number of items to 36, with redundant items being combined.

2.4. Expert Review and Finalization (34 Initial Items)

The 36 statements were reviewed with two biblical scholars from the Catholic University of America, two theologians from Baylor University and Hong Kong Baptist University, and one philosopher of religion from Wake Forest University. All interviewees had known the first author for at least three years and were familiar with this study. The reviews focused on which items should be deleted and whether any items should be added.

Both theologians stated that God’s love should be considered when discussing God’s justice. Similarly, the philosopher mentioned the comprehensive characteristics of God. Accordingly, two items were added: “Whether I love God or not, God still loves me,” and “Whether other people love God or not, God still loves them.”

The theologian from Baylor University stated that God’s main characteristics for this study, namely that God is just, should be added. This comment resulted in one additional item: “God is just.”

Both biblical scholars mentioned the biblical bias; that is, the potential participants of the survey might choose to agree with the contents of the items merely because they were from the Bible instead of because they aligned with their beliefs. Thus, some items were rewritten to avoid the biblical bias. For the same reason, we replaced the terms “righteous people” and “evil people” with “good people” and “bad people.” Due to a concern that the participants might be confused about who was a good person and who was a bad person, we also added a new item: “God judges who is good and who is bad.”

Overall, four items were added, and redundant items were combined, resulting in an initial 34-item scale divided into three conceptual categories. A native English speaker from Hong Kong Baptist University, who is also a theologian and familiar with this study, helped revise the items to make them readable and understandable. This 34-item version of the CBJWS (see Appendix A) served as the basis for Study 1.

3. Study 1: Christian Belief in a Just World Scale

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

Three rounds of surveys were conducted using Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) and Prolific, two widely used online participant recruitment platforms. All procedures were approved by the University’s Ethics Committee, and questionnaires were administered through Qualtrics.

Participants were recruited from Christian populations in the United States, including Catholics, Protestants, and Eastern Orthodox adherents. Data collection yielded three independent samples (see Table 1):

- Sample 1: A total of 258 responses were collected through Prolific. After excluding participants who failed the embedded attention check or displayed extreme high or low values, 18 invalid responses were removed, resulting in 240 valid cases (a 93% effective response rate).

- Sample 2: Of 832 responses collected through MTurk, 94 were excluded for failing the attention check or exhibiting extreme values, resulting in 738 valid cases (88.7% effective rate).

- Sample 3: A total of 413 responses were collected through Prolific, of which 51 were excluded due to attention check failure or outlier status, yielding 362 valid responses (87.7% effective rate).

All participants were at least 18 years old and had completed a minimum of a high school education.

Table 1.

Sample demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample demographic characteristics.

| Characteristic | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Prolific | MTurk | Prolific | |

| N | 240 | 738 | 362 | |

| Gender | Male (%) | 93 (38.75%) | 461 (62.47%) | 163 (45%) |

| Female (%) | 147 (61.25%) | 277 (37.53%) | 199 (55%) | |

| Age | >18 | >18 | >18 | |

| Religious (%) | Catholic | 107 (44.58%) | 665 (90.11%) | 22 (6.08%) |

| Orthodox | 19 (7.92%) | 54 (7.32%) | 1 (0.28%) | |

| Protestant | 114 (47.5%) | 19 (2.57%) | 339 (93.64%) | |

| Education Level (%) | High school education and above | High school education and above | High school education and above | |

3.1.2. Materials/Measures

Christian Belief in a Just World Scale (CBJWS). The initial 34-item version of the CBJWS, developed in the pilot study, was administered. Items were designed to measure three assumed preliminary dimensions of Christian belief in a just world.

Religious Commitment Scale (RCS). The Religious Commitment Scale was utilized, with minor revisions for Christians, to assess the criterion-related validity of the Christian belief in a just world construct. The scale demonstrated high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.688 (Koenig and Büssing 2010). Higher scores on this scale indicate more frequent participation in religious practices and activities.

3.1.3. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 29.0. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed on Sample 1 (N = 240), while confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on Sample 2 (N = 738) and criterion validity testing and inter-correlation analysis were performed on Sample 3 (N = 362).

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for the finalized Christian belief in a just world scale (CBJWS) are presented in Table 2. These statistics are based on the two independent samples used for validation purposes after the scale’s factor structure was established through exploratory analysis: Sample 2 (CFA) and Sample 3 (criterion validity testing). The means and standard deviations provide a reference for the distribution of scores in validation contexts. (The initial exploratory sample, Sample 1, is not included in this table as it was used for scale development prior to structural finalization).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of CBJWS across samples.

3.2.2. Discriminant Validity

Item analysis was conducted on the initially developed Christian belief in a just world scale (CBJWS) using Sample 1. Critical ratio (CR) values were calculated to evaluate item discrimination. The total scores of all items were summed, and participants were divided into high- and low-score groups based on the 27th and 73rd percentiles. An independent samples t-test was then performed to compare the differences between these two groups. The results indicated a statistically significant difference between the scores of the high and low groups (p < 0.001), demonstrating strong discriminant validity.

3.2.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Factor Analysis Suitability Test. The suitability of the data from Sample 1 for exploratory factor analysis was evaluated. The results indicated a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value of 0.877 (exceeding the threshold of 0.8), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a χ2 value of 4554.769 (df = 351, p < 0.001), confirming that the data were appropriate for factor analysis.

Principal Component Analysis. Principal component analysis was employed to perform EFA on the data from Sample 1. Initial results indicated the presence of eight factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. After several iterations, during which items with factor loadings below 0.5 or cross-loading on multiple factors were progressively removed, seven items were eliminated: Items 1, 8, 10, 15, 21, 26, and 32.

Item Analysis. Prior to the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), standard item analysis was conducted on the initial 34 items to refine the scale. This process combined three methods: critical ratio (CR) analysis using independent samples T-tests, item–total correlation screening (retaining items with r > 0.40), and assessment of internal consistency. Based on these criteria, seven items (1, 8, 10, 15, 21, 26, 32) were removed due to low correlations or unclear factor loadings. The remaining 27 items were retained for subsequent EFA.

Exploratory Factor Analysis. A subsequent EFA was conducted on the remaining 27 items. The results (see Table 3) revealed four factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1, which collectively accounted for 63.527% of the total variance. Based on the factor loadings and conceptual alignment, the four dimensions of the CBJWS were identified as God’s Punishment, God’s Reward, God’s Sovereignty, and God’s Forgiveness. The assignment of items to each dimension and their corresponding codes are presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Results of EFA for CBJWS (N = 240).

Table 4.

The structural matrix of CBJW after rotation (N = 240).

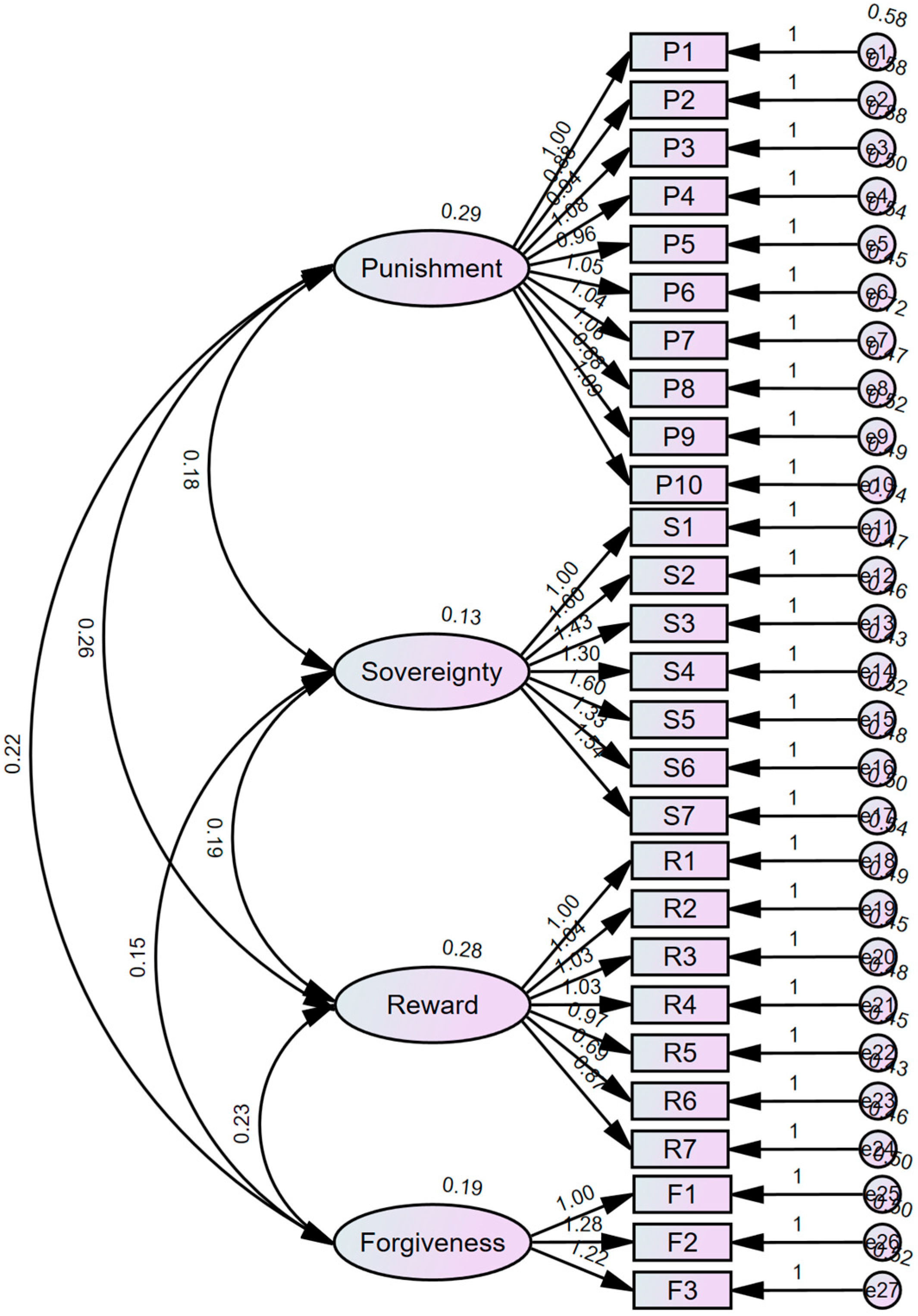

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the CBJWS using the maximum likelihood method. The results indicated that the four-factor model (see Figure 1) demonstrated a good fit to the data. Specifically, the comparative fit index (CFI = 0.942), the normed fit index (NFI = 0.899), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI = 0.936), the incremental fit index (IFI = 0.943), and the goodness-of-fit index (GFI = 0.936) all exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.80. Additionally, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.040) was below the criterion of 0.06, and the ratio of χ2 to degrees of freedom (χ2/df = 2.182) further supported the model’s acceptable fit (Hu and Bentler 1999). All standardized factor loadings were significant and substantial, and the communalities indicated that a significant portion of each item’s variance was explained by its respective latent factor (see Table 5 and Table 6). These indices collectively indicate that the four-factor structure of the CBJW is well supported.

Figure 1.

The validation path diagram of CBJW.

Table 5.

Confirmatory factor analysis results of CBJW (N = 738).

Table 6.

Confirmatory factor analysis results: factor loadings, communalities, and psychometric properties of CBJWS (N = 738).

Internal Consistency Reliability. The scale’s reliability was assessed using multiple indices. For the full 27-item scale, Cronbach’s α was 0.929 in Sample 2 (N = 738), indicating excellent internal consistency. The Cronbach’s α for the subscale Punishment was 0.837; for Reward, it was 0.789; and Sovereignty was 0.770, exceeding the 0.70 threshold, which showcased the adequate reliability of these latent constructs. The Cronbach’s α for the 3-item Forgiveness subscale was 0.600, which was marginally acceptable (See Table 6).

3.2.4. Criterion-Related Validity and Inter-Correlation Analysis

Criterion-Related Validity. To examine the criterion validity of the CBJW scale, Pearson correlation analysis was conducted on Sample 3 (N = 362). As shown in Table 7, the total score of the CBJWS demonstrated a significant positive correlation with scores on the RCS (r = 0.420, p < 0.01). This provides strong evidence for the scale’s criterion-related validity. At the subscale level, all four dimensions were also significantly and positively correlated with religious commitment. The strength of association varied across dimensions, with God’s Sovereignty showing the strongest correlation (r = 0.462, p < 0.01), followed by God’s Forgiveness (r = 0.320, p < 0.01), God’s Punishment (r = 0.287, p < 0.01), and God’s Reward (r = 0.272, p < 0.01). These results collectively confirm that the CBJW construct, both globally and in its specific dimensions, is meaningfully related to a core aspect of religious engagement.

Table 7.

Correlation analysis between CBJWS and RCS (N = 362).

Inter-correlation Analysis. The inter-correlations among the four dimensions of the CBJW scale and its total score were also analyzed (see Table 7). The total score was strongly correlated with each of its constituent dimensions, and the correlations among the four subscales were all positive and statistically significant. This pattern of moderate inter-correlations provides empirical support for the distinctiveness of the four proposed dimensions while confirming their shared relationship with the overarching CBJW construct. The correlation between God’s Punishment and God’s Forgiveness was the weakest (r = 0.132, p < 0.05), suggesting these two dimensions represent more distinct theological facets within the belief system.

4. Discussion: The Features of Christian Belief in a Just World

The above results indicate the internal reliability and validity of the developed scale for CBJW, which has 27 items distributed across four dimensions. The significant positive association between CBJW and religious commitment further supports the convergent validity of the CBJW scale, suggesting that individuals who exhibit higher levels of commitment to their faith also tend to more strongly endorse Christian belief in a just world.

The following discussion interprets the findings within a psychological framework. Although the CBJW scale employs language drawn from Christian theology, it assesses not divine justice as such, but Christian believers’ psychological representations of divine justice; that is, how Christian believers construe justice, deservedness, and moral order in the world by reference to God.

4.1. Divine Justice and Christian Belief in a Just World

The present study does not seek to define divine justice as theological reality but to examine how Christians psychologically construe justice in the world through their beliefs about God. In this sense, Christian belief in a just world (CBJW) should be understood as a belief system that mediates between theological concepts of divine justice and everyday just-world reasoning. While divine justice refers to God’s moral governance as articulated within Christian theology through biblical texts, CBJW captures believers’ representations of that governance as it relates to deserved outcomes, moral accountability, and ultimate rectification. The distinction is that the CBJW scale assesses not what divine justice is, but how beliefs about divine justice function psychologically to organize meaning and expectations of justice in Christian believers’ daily lives.

This framing helps clarify why the dimensions identified in the present study are labeled with reference to divine attributes. These labels reflect the content of belief representations rather than doctrinal claims about God, and they indicate how theological concepts are appropriated within believers’ psychological frameworks.

Notably, throughout the present study, references to belief in a just world (BJW) serve as a theoretical and conceptual function rather than an empirical one. The CBJW scale was developed within the broader BJW tradition, drawing on established theoretical accounts of deservedness, moral order, and outcome justice. Accordingly, when parallels are noted between certain CBJW dimensions (e.g., beliefs concerning reward and punishment, as will be discussed in Section 4.5 below) and existing BJW constructs, these similarities are intended to indicate conceptual and functional overlaps, not empirical equivalence or direct scale comparison. Empirical comparisons between CBJW and established BJW measures remain an important task for future research but fall beyond the scope of the present initial validation study.

4.2. Theoretical Expectations and Empirical Refinement of CBJW

The initial conceptualization of the CBJW scale was informed by established research on belief in a just world, particularly the distinction between beliefs oriented towards self, others, and the world in general, which we have described in the Introduction. This tripartite framework has proven theoretically fruitful in secular BJW research and therefore served as a heuristic starting point for item development in the present study.

However, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses did not support this distinction as an organizing principle for Christian just-world belief. Instead, items clustered according to their theological content, yielding four dimensions: God’s Punishment, God’s Reward, God’s Sovereignty, and God’s Forgiveness. This finding suggests that, in Christian belief representations, just-world reasoning is structured less by the target of belief (self vs. others) and more by the perceived modes of divine action through which justice is enacted.

Notably, this result should not be interpreted as contradicting the self–other distinction that is central to BJW research, but rather as indicating, perhaps, that this distinction operates at a different analytical level. Whereas the present scale captures content-based dimensions of belief about divine justice, self/other-oriented just-world beliefs may emerge as secondary differentiations within these dimensions. The absence of explicit self–other subscales in the current instrument thus reflects a feature of the empirical structure rather than a conceptual oversight. Thus, future research may build on the present findings by developing subscales that integrate content-based dimensions with self–other distinction, thereby allowing a more fine-grained analysis of how Christian just-world beliefs operate across interpersonal contexts.

4.3. The Relationship Between Divine Justice and Divine Love

As briefly surveyed in the introduction of this paper, it is debatable whether the feature of divine justice should be discussed together with divine love. If they should go together, then it is more appropriate to speak of comprehensive divine attributes rather than analytically independent ones. However, the present findings suggest that, at the level of belief representation, Christian believers may psychologically distinguish between justice-related beliefs and beliefs concerning unconditional divine love.

Our initial item pool, resulting from the pilot study, included two explicit statements of unconditional divine love (“Whether I love God or not, God still loves me”; “Whether other people love God or not, God still loves them”). Both items concern divine mercy. In the factor analyses in Study 1, neither item met the loading threshold and so both items were dropped. Why would explicit love statements fail to function as indicators of justice belief?

Seen from the measurement perspective, the deletion does not imply that respondents rejected divine love. Instead, it indicates that such items were psychologically organized as adjacent to, but not diagnostic of, latent justice constructs. In other words, participants distinguished between (a) God’s unconditional benevolence and (b) beliefs about rectification—God’s governance, judgment, and restoration. This is a healthy sign of construct specificity.

Theologically, love and justice are perfections of the same God, not rivals. Love names God’s self-giving benevolence, while justice names God’s rectifying work. If unconditional love items failed to load, a plausible explanation is ceiling/consensus effects (near-universal assent reduces covariance) combined with the fact that justice beliefs are teleological—concerned with how God makes things right, not simply that God loves. In other words, justice and love could be independent characteristics of God; Christians can talk about one characteristic without necessarily mentioning the other.

Although the present account of the relationship between divine justice and divine love is theoretical in nature, it lends itself to empirical examination in future research. Subsequent studies may operationalize beliefs about divine love using established measures of perceived divine love or benevolence and examine how these beliefs relate to different dimensions of Christian belief in a just world. Such research could clarify whether representations of divine love function primarily as a moderating, mediating, or complementary factor in just-world reasoning, particularly in relation to forgiveness and perceived moral order.

4.4. Divine Justice and Secular Justice

Two retained items in the initial 34-item scale were drawn from wisdom traditions where moral cause-and-effect is often stated without explicit invocation of God. These are Item 7, “Anyone who works hard will have a good life,” and Item 9, “Good people will receive the rewards that they deserve.” That these items loaded well indicates that Christians recognize certain moral regularities that are intelligible even when stated proverbially. For Christians, such regularities are ultimately grounded in God’s governance, but they can be expressed in public or “secular” idioms (Barton 2003; Davis 2000). According to the comments of two biblical scholars on our initial 34 items, Christians believe that practical wisdom from the Christian wisdom tradition is universal rather than merely for Christians.

Notably, two other items from the wisdom tradition were deleted: Item 8, “Anyone who does not work hard will have a bad life,” and Item 10, “Bad people will receive the punishment that they deserve.” These item behaviors may indicate two features of Christian understanding of practical life concerning justice.

First, there is an asymmetry related to the connection between one’s work and one’s life. While Item 8 was deleted, Item 7 was retained, as discussed above. This contrast suggests the following belief: that hard work leads to a good life does not necessarily mean that lack of hard work leads to a bad life. Determining how to define a “bad” life is crucial, because such a definition could be highly personal.

Second, deleting Item 10 is more conceptually revealing because two similar items were retained, although they were not from the wisdom tradition. Item 6 states, “When bad people do bad things, God will curse them,” and Item 12 claims, “If a good person starts doing bad things, God will punish them.” Thus, the point here may be related to the ambiguity of the term “bad people” in Item 10, as opposed to “bad things” in Items 6 and 12.

One more point in this regard deserves a brief discussion. As mentioned in the Introduction, Brazilian scholars (Linhares et al. 2022a, 2022b) have developed measurements for BJW based on popular sayings. A couple of items from their scales are from biblical texts, such as “Live by the sword, die by the sword” (Matt 26:52) and “You reap what you sow” (Gal 6:7). Interestingly, some Asian studies interpret similar sayings as karmic expressions (Duong et al. 2024). These parallels suggest that religious belief in a just world, including the Christian one, overlaps with secular belief in a just world. The reason behind this might be the fact that the just-world belief is fundamental in human hearts, whether they are religious or not.

However, rather than suggesting a direct equivalence between karmic and Christian frameworks, the similarity mentioned may point to the possibility that just-world reasoning is grounded in shared moral intuitions that are variously articulated across religious traditions. From this perspective, religiosity may function as a culturally structured medium through which fundamental human intuitions about justice, deservedness, and moral order are expressed and sustained.

4.5. Two Unique Features of Christian Belief in a Just World

In our scale for CBJW, the content of the items in the dimensions of God’s Punishment and God’s Reward resembles the corresponding content in most items of existing scales for BJW, except that the punishment and reward there are not performed by God (e.g., Lipkus 1991; Lipkus et al. 1996; Lucas et al. 2007, 2011; White et al. 2019). Both frameworks, CBJW and the existing scales, emphasize expectations of deserved outcomes—negative consequences following wrongdoing and positive outcomes following moral behavior—as central elements of just-world reasoning. We understand that this resemblance is intended in a conceptual and functional sense rather than as an empirical or item-level equivalence.

At the same time, our analyses identified two distinctively theological dimensions—God’s sovereignty and God’s forgiveness—that are not reducible to secular BJW.

God’s Sovereignty. This feature distinguishes CBJW from BJW, just as the concept of Karma makes the belief in Karma different from BJW (White et al. 2019), despite similarities between them.

Theologically, God’s sovereignty can be seen as the teaching that all things come from and depend upon God, and God judges his creation on the basis of his profound moral character (Leonard 1991). Philosophically, God’s sovereignty means that by virtue of his creative activity, God is solely responsible for the world and its entire history (McCann 2012). No matter how one defines it, sovereignty is central to Christian faith; it is accepted by all denominations, despite some minor differences regarding how to define it (Pinnock 1996). Also, it is clearly expressed in some biblical texts, such as Job 42:2: “I know that you can do all things, and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted.” Thus, the inclusion of this dimension of Christian belief in a just world reflects the significance of God’s sovereignty for Christian faith, making this belief unique and distinct from secular BJW.

Notably, the factor of sovereignty contains items expressing the eschatological vision of Christian faith. In the initial items, there are three eschatological ones: Item 4, “When Jesus comes again, he will reward the good people and punish the bad people,” Item 14, “When Jesus comes again, he will give me what I ought to receive,” and Item 25, “When Jesus comes again, he will give other people what they ought to receive.” Initially, these items corresponded to the distinction between BJW for self, BJW for others, and BJW in general. However, the EFA and CFA support the distribution of these three items in one dimension instead of three. This result does not merely reveal a unique feature of Christian belief in a just world but also indicates the eschatological dimension of God’s sovereignty.

Interestingly, the eschatological element of Christian belief in a just world resonates with a unique dimension of the belief in Karma, which involves the future life, expressed in items such as “If a person does something bad, even if there are no immediate consequences, they will be punished for it in a future life” (White et al. 2019, p. 1187). The condition “in a future life” sounds like the counterpart of the condition “when Jesus comes again” in CBJW. Both items indicate the uniqueness of religious belief in a just world compared to the secular belief in a just world. At the same time, however, these two items have different contents, indicating the difference between Christianity and South Asian religions (Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism) regarding their understanding of justice.

God’s Forgiveness. Another unique feature of Christian belief in a just world is its dimension of God’s Forgiveness, which connects retributive justice with restorative justice in Christianity.

Theologically, there is consistency between divine justice and sin-bearing divine forgiveness (Mihut 2023). At first glance, divine forgivingness seems to be in tension with the demands of God’s retributive justice to punish people according to what they deserve. However, a closer examination reveals the association between the two because “divine retributive justice entails that God, as the ultimate moral legislator, fittingly visits intentional and proportionate harm upon sinners because of their sin” (Mihut 2023, p. 77).

Divine forgiveness in Christianity is restorative because, according to the doctrine of original sin, the human heart and mind work in a world that is fragmented through sin and thus invite a compassionate God to offer redemption (Ely 2018). As another theologian has pointed out, “it is necessary to restore right relationship with God through forgiveness” (Wiegman 2017, p. 187). Therefore, the dimension of God’s Forgiveness in CBJW speaks to the Christian understanding of the human–God relationship and God’s function in maintaining this relationship. It portrays the Christian understanding of Divine justice as different from the secular one.

Psychological research has reported numerous findings about the correlation between BJW and forgiveness, which indicate an asymmetry between the BJW–self and BJW–others regarding their association with forgiveness (Lucas et al. 2010; Strelan 2007; Strelan and Sutton 2011). Because the measurement developed in this study did not emphasize this distinction between self and others, it becomes challenging to explore the correlation between Christian belief in a just world and forgiveness. The subscales discussed in Section 4.2 above will help in this regard.

5. Limitations

While helping to clarify the features of Christian belief in a just world, the present study has some limitations in both its methods and theoretical assumptions.

Methodologically, the samples were drawn exclusively from American participants, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to Christians from other cultural contexts. Moreover, the use of self-report data may have introduced social desirability bias, particularly given the religious content of the items, although we have tried our best to avoid biblical bias. Finally, as detailed in Section 4.2 above, the CBJWS does not explicitly distinguish between self- and other-oriented just-world beliefs, as proposed in the bidimensional BJW model and anticipated by our initial distribution of 34 items into three categories. Future research would benefit from developing subscales to separately assess Christian beliefs in a just world for self, for others, and for humanity in general.

Theologically, although it makes sense to focus on retributive justice when discussing Christian just-world belief, the former does not exhaust all the dimensions of the latter. It will be constructive to integrate restorative justice and distributive justice into the definition of divine justice. In doing so, a discussion of the features of Christian belief in a just world, or Christian justice belief, will be more comprehensive.

In addition, the present study did not consider cross-cultural and denominational differences in the understanding of retributive justice. Nor did it explore how unique the Christian understanding of the belief in a just world is, compared to the understanding within other religious traditions, like Buddhism. Thus, it will be beneficial to research Christian belief in a just world across various Christian denominations and across Christianity in different cultures. It will also be helpful to compare Christianity and Buddhism in just-world beliefs further, as other dimensions of comparison have yielded interesting results (White and Norenzayan 2022).

Lastly, as the present study represents an initial stage of scale development, our approach to external validity was intentionally conservative. Rather than employing multiple external measures, we selected the Religious Commitment Scale (RCS) as a well-established and psychometrically reliable criterion to provide initial evidence of convergent validity. Although relying on a single external criterion is necessarily limited, using a robust and theoretically relevant measure at this early stage helps ensure that observed associations are interpretable and not confounded by measurement error. In this sense, the present findings should be understood as establishing preliminary validity rather than offering a comprehensive validation of the CBJW scale. Broader examinations of external validity, incorporating additional constructions and comparison measures are important for subsequent research.

6. Conclusions

The present study sets out to examine the features of Christian belief in a just world (CBJW) by developing and validating a psychometric scale grounded in biblical texts and informed by belief in a just world theory. Conceptualizing CBJW as a psychological belief system through which Christian believers construe justice, deservedness, and moral order by reference to God, the study identified a four-dimension structure comprising God’s Punishment, God’s Reward, God’s Sovereignty, and God’s Forgiveness. The findings indicate that Christian just-world belief overlaps with secular BJW in its emphasis on deserved outcomes, while extending it through theologically mediated dimensions that enable believers to sustain just-world reasoning in the face of delayed, hidden, or eschatological justice. In this way, CBJW represents a distinctive form of just-world belief shaped by religious content but operating through familiar psychological functions.

By clarifying the structure and features of CBJW, this study contributes to research on belief in a just world, psychology of religion, and interdisciplinary dialogue between psychology and theology. Future research may further refine the scale by incorporating self–other distinctions, examining convergent validity with established BJW measures, and exploring denominational and cross-cultural variations in Christian just-world belief.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L.; Methodology, X.L. and L.L.; Validation, L.L.; Formal analysis, X.L.; Data curation, L.L.; Writing—original draft, X.L. and L.L.; Writing—review and editing, X.L. and L.L.; Visualization, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Social Science Fund of China: 24BZJ044 and John Templeton Foundation via the University of Birmingham: 3218139.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethical Review Board of the School of Philosophy and Social Development at Shandong University (no code, date of approval: 3 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Initial Items for Christian Belief in a Just World Scale

- Christian general belief in a just world

- 1.

- God is just.

- 2.

- God judges who is good and who is bad.

- 3.

- God rewards and punishes people justly.

- 4.

- When Jesus comes again, he will give people what they ought to receive.

- 5.

- When good people do good things, God will bless them.

- 6.

- When bad people do bad things, God will curse them.

- 7.

- Anyone who works hard will have a good life.

- 8.

- Anyone who does not work hard will have a bad life.

- 9.

- Good people will receive the rewards that they deserve.

- 10.

- Bad people will receive the punishments that they deserve.

- 11.

- If a bad person confesses their sins to God, God will forgive them.

- 12.

- If a good person starts doing bad things, God will punish them.

- Christian belief in a just world for self

- 13.

- God rewards and punishes me justly.

- 14.

- When Jesus comes again, he will give me what I ought to receive.

- 15.

- Whether I love God or not, God still loves me.

- 16.

- If I reject God, God will reject me.

- 17.

- When I experience misfortune, that is God’s punishment because of my previous behavior.

- 18.

- When I experience good fortune, that is God’s reward because of my previous behavior.

- 19.

- If I do good things, God will reward me.

- 20.

- If I do bad things, God will punish me.

- 21.

- If I obey God, God will reward me.

- 22.

- If I disobey God, God will punish me.

- 23.

- If I confess my sins to God, God will forgive me.

- Christian belief in a just world for others

- 24.

- God rewards and punishes other people justly.

- 25.

- When Jesus comes again, he will give other people what they ought to receive.

- 26.

- Whether other people love God or not, God still loves them.

- 27.

- If other people reject God, God will reject them.

- 28.

- When other people experience misfortune, that is God’s punishment because of their previous behavior.

- 29.

- When other people experience good fortune, that is God’s reward because of their previous behavior.

- 30.

- If other people do good things, God will reward them.

- 31.

- If other people do bad things, God will punish them.

- 32.

- If other people obey God, God will reward them.

- 33.

- If other people disobey God, God will punish them.

- 34.

- If other people confess their sins to God, God will forgive them.

Appendix B. Christian Belief in a Just World Scale

| Christian Belief in a Just World Scale | |

| All items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) | |

| Factor I God’s Punishment | |

| 5 | When bad people do bad things, God will curse them. |

| 9 | If a good person starts doing bad things, God will punish them. |

| 12 | If I reject God, God will reject me. |

| 13 | When I experience misfortune, that is God’s punishment because of my previous behavior. |

| 16 | If I do bad things, God will punish me. |

| 17 | If I disobey God, God will punish me. |

| 21 | If other people reject God, God will reject them. |

| 22 | When other people experience misfortune, that is God’s punishment because of their previous behavior. |

| 25 | If other people do bad things, God will punish them. |

| 26 | If other people disobey God, God will punish them. |

| Factor II God’s Sovereignty | |

| 1 | God judges who is good and who is bad. |

| 2 | God rewards and punishes people justly. |

| 3 | When Jesus comes again, he will reward the good people and punish the bad people. |

| 10 | God rewards and punishes me justly. |

| 11 | When Jesus comes again, he will give me what I ought to receive. |

| 19 | God rewards and punishes other people justly. |

| 20 | When Jesus comes again, he will give other people what they ought to receive. |

| Factor III God’s Reward | |

| 4 | When good people do good things, God will bless them. |

| 6 | Anyone who works hard will have a good life. |

| 7 | Good people will receive the rewards that they deserve. |

| 14 | When I experience good fortune, that is God’s reward because of my previous behavior. |

| 15 | If I do good things, God will reward me. |

| 23 | When other people experience good fortune, that is God’s reward because of their previous behavior. |

| 24 | If other people do good things, God will reward them. |

| Factor IV God’s Forgiveness | |

| 8 | If a bad person confesses their sins to God, God will forgive them. |

| 18 | If I confess my sins to God, God will forgive me. |

| 27 | If other people confess their sins to God, God will forgive them. |

References

- Adam, Samuel L. 2015. The justice imperative in Scripture. Interpretation 69: 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, John. 2003. Understanding Old Testament Ethics: Approaches and Explorations. Louisville: Westminster John Knox. [Google Scholar]

- Bègue, Laurent, and Marina Bastounis. 2003. Two Spheres of Belief in Justice: Extensive Support for the Bidimensional Model of Belief in a Just World. Journal of Personality 71: 435–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chobthamkit, Phatthanakit, Robbie M. Sutton, Ayse K. Uskul, and Trawin Chaleeraktrakoon. 2022. Personal Versus General Belief in a Just World, Karma, and Well-Being: Evidence from Thailand and the UK. Social Justice Research 35: 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbert, Claudia. 1999. The World is More Just for Me than Generally: About the Personal Belief in a Just World Scale’s Validity. Social Justice Research 12: 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbert, Claudia, Leo Montada, and Manfred Schmitt. 1987. Glaube an eine gerechte Welt als Motiv: Validierungskorrelate zweier Skalen. Psychologische Beitrage 29: 596–615. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Ellen F. 2000. Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs. Louisville: Westminster John Knox. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, Cong Doanh, Trong Nghia Vu, Thi Viet Nga Ngo, Nhat Minh Tran, and Ngoc Xuan Vu. 2024. How Karmic Beliefs and Belief in Just World Interact to Activate Social Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Polynomial Regression with Response Surface Analysis. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 16: 1805–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, Peter B. 2018. Adam and Eve in Scripture, Theology, and Literature. Sin, Compassion, and Forgiveness. Lanham, Maryland and London: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, Adrian. 1998. Measuring the Belief in a Just World. Pages In Responses to Victimizations and Belief in a Just World. Edited by Leo Montada and Melvin J. Lerner. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 141–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1−55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G., and Arndt Büssing. 2010. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): A five-item measure for use in epidemiological studies. Religions 1: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, William. 1991. Sovereignty of God. In Holman Bible Dictionary. Edited by Trent C. Bulter, Marsha A. E. Smith, Forrest W. Jackson and Chris Church. Nashville: Holman Bible Publishers, p. 1296. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, Melvin J. 1965. Evaluation of Performance as a Function of Performer’s Reward and Attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1: 355–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, Melvin J. 1970. The Desire for Justice and Reactions to Victims. In Altruism and Helping Behavior. Edited by Jacqueline Macaulay and Leonard Berkowitz. New York: Academic Press, pp. 205–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, Melvin J. 1980. The Belief in a Just World: A Fundamental Delusion. New York: Plenum. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Melvin J., and Dale T. Miller. 1978. Just World Research and the Attribution Process: Looking Back and Ahead. Psychological Bulletin 85: 1030–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhares, Layanne Vieira, Ana Raquel Rosas Torres, and Cícero Roberto Pereira. 2022a. Live by the sword, die by the sword: Measuring belief in a just world with popular sayings. Personality and Individual Differences 195: 111673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhares, Layanne Vieira, Ana Raquel Rosas Torres, and Cícero Roberto Pereira. 2022b. Validation of the revised belief in a just world scale based on popular sayings. Aáalise Psicolōgica 40: 147–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipkus, Isaac M. 1991. The Construction and Preliminary Validation of a Global Belief in a Just World Scale. Personality and Individual Differences 12: 117–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipkus, Issac M., Claudia Dalbert, and Ilene C. Siegler. 1996. The Importance of Distinguishing the Belief in a Just World for Self Versus for Others: Implications for Psychological Well-Being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 22: 666–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Todd, Jason D. Young, Ludmila Zhdanova, and Sheldon Alexander. 2010. Self and other justice beliefs, impulsivity, rumination, and forgiveness: Justice beliefs can both prevent and promote forgiveness. Personality and Individual Differences 49: 851–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Todd, Ludmila Zhdanova, and Seldon Alexander. 2011. Procedural and distributive justice beliefs for self and others: Assessment of a four-factor individual differences model. Journal of Individual Differences 32: 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Todd, Sheldon Alexander, Ira Firestone, and James M. LeBeton. 2007. Development and initial validation of a procedural and distributive just world measure. Personality and Individual Differences 43: 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, William E. 2019. Anselm on divine justice and mercy. Religious Studies 55: 469–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, Hugh J. 2012. Creation and the Sovereignty of God. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mihut, Christian F. 2023. Gracious Forgiveness. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnock, Clark H. 1996. God’s Sovereignty in today’s World. Theology Today 53: 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, David D. 2001 Concepts of Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rubin, Zick, and Anne Peplau. 1973. Belief in a just world and reactions to another’s lot: A study of participants in the national draft lottery. Journal of Social Issues 29: 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Zick, and Letitia Anne Peplau. 1975. Who believes in a just world? Journal of Social Issues 31: 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelan, Peter. 2007. The prosocial, adaptive qualities of just world beliefs: Implications for the relationship between justice and forgiveness. Personality and Individual Differences 43: 881–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelan, Peter, and Robbie M. Sutton. 2011. When just world beliefs promote and when they inhibit forgiveness. Personality and Individual Differences 50: 163–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, Robbie M., and Maren M. Douglas. 2005. Justice for All, or Just for Me? More Evidence of the Importance of the Self-other Distinction in Just-world Beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences 39: 637–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, Robbie M., Joachim Stoeber, and Shanmukh V. Kamble. 2017. Belief in a Just World for Oneself versus Other, Social Goals, and Subjective Well-being. Personality and Individual Differences 113: 115–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, Johan C. 2009. Justice in the Sermon on the Mount: An Aristotelian Reading. Novum Testamentum 51: 314–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volf, Miroslav. 1996. Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation. Grand Rapids: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, Cindel J. M., and Ara Norenzayan. 2022. Karma and God: Convergent and Divergent Mental Representations of Supernatural Norm Enforcement. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 14: 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Cindel J. M., Ara Norenzayan, and Mark Schaller. 2019. The content and correlates of belief in Karma across cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 45: 1184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegman, Isaac. 2017. Divine Forgiveness and Merch in Evolutionary Perspective. In Connecting Faith and Science: Philosophical and Theological Inquiries. Edited by Matthew Nelson Hill and Wm. Curtis Holtzen. Claremont: Claremont Press, pp. 183–213. [Google Scholar]

- Wolterstorff, Nicholas. 2011. Justice in Love. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.