1. Introduction

Some of the Khotanese texts discovered inside the Dunhuang library cave are written on the verso of Chinese scrolls containing Buddhist scriptures, creating an intriguing combination of languages, scripts and texts. The manuscripts attest to the close connections between the two oasis cities, each located at a strategic point along the trade routes of Central Asia. Because there is no obvious relationship between the contents on the two sides of the scrolls, modern scholarship has tended to interpret this phenomenon in terms of paper shortage, viewing it as the recycling of scrolls that were no longer needed. This view is probably not wrong, but it may not be the complete picture. This paper revisits the practice of reuse and argues that the repurposing of Chinese scrolls to write Khotanese texts cannot be explained solely in terms of paper scarcity or the desire to economise on costs. Rather, the paper situates these manuscripts within a broader range of reuse practices attested across manuscript cultures in Asia and beyond. The central argument advanced here is that reuse involved a deliberate engagement with earlier textual layers, which retained aspects of their meaning and value even as new texts were added and the manuscript’s function evolved.

Khotanese texts from Dunhuang form a small but conspicuous group of manuscripts, representing an invaluable body of material for the study of Khotanese language and history. Hiroshi Kumamoto classifies the Khotanese manuscripts discovered in the Dunhuang library cave into two categories. The first consists of monolingual

pothī manuscripts, predominantly featuring Khotanese versions of Buddhist scriptures and medical texts (

Kumamoto 1996, pp. 90–98; see also

Emmerick 1992, p. 5 and

Yoshida 2015). An example is Pelliot khotanais 428 (1068, FM 25, 1), a fragment of the

Bhaiṣajyaguru-sūtra (

Medicine Buddha Sūtra). This is one of the earliest Mahāyāna texts, extant in many languages, including Chinese, Sanskrit, Sogdian, Old Uyghur and Khotanese. In addition to the Pelliot manuscript, Khotanese fragments of the same text are preserved in the British Library in London and the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts in St. Petersburg. Earlier scholarship believed that the Khotanese version diverged from other linguistic traditions and may have belonged to ‘an independent Central Asian tradition’.

1 More recently, however, the late Diego Loukota established that the Khotanese text was in fact translated from Chinese and shows a close affiliation with the version found in

juan 卷 12 of the

Guanding jing 灌頂經 (

Consecration Sūtra) (

Loukota 2019).

The second category of Khotanese writings contains those written on the verso of Chinese Buddhist scrolls, numbering about 90 manuscripts in total (

Kumamoto 1996, pp. 90–8; see also

Yoshida 2015). The Khotanese texts preserved in these scrolls comprise a diverse body of material. According to Yoshida Yutaka, they were produced for practical purposes by Khotanese officials during their stay in Dunhuang (

Yoshida 2015). The material includes drafts of letters and reports written to the Khotanese court, accounts and contracts, writing exercises, narrative works such as the

Rāmāyaṇa and

Sudhanāvadāna, lyrical poetry, medical treatises and Buddhist texts. In contrast to the textual and visual homogeneity of the Chinese sūtras, the Khotanese writings on the verso display far greater variety, reflecting everyday concerns, activities and interests.

The current paper focuses on this second category of bilingual manuscripts; however, rather than examining the Khotanese texts themselves, significant as they may be, I turn my attention to the Chinese side of the scrolls. This is the side written first, without anticipating that the blank verso would later be reused for another purpose. The Chinese texts are, for the most part, popular Mahāyāna sūtras, which survive in Dunhuang in hundreds or even thousands of copies and are also well known in transmitted editions. Precisely for this reason, these scrolls do not offer unexpected insights into the textual history of the scriptures, which is also part of the reason why they have failed to attract more scholarly attention.

One could argue that Chinese scrolls with Khotanese text on the verso do not constitute a meaningful category, since the Khotanese scribes could have selected Chinese scrolls at random from what was available to them, without regard to their content or origin. This assumption aligns with the common view that the Chinese scrolls were reused simply because their blank verso offered a convenient writing surface. If this were the case, we would not expect to observe patterns beyond those found in a random selection of manuscripts. Yet this is not what the evidence suggests. Instead, the Chinese scrolls with Khotanese texts tend to resemble each other, both in terms of content and physical characteristics. The internal consistency of this group raises the possibility that the scrolls do not represent an entirely random selection.

Apart from the Khotanese texts on the verso, the most obvious pattern in this group is the similarity of the Chinese texts. They were copied in a standard kai 楷 (regular) script on yellow or brownish paper, mostly following the 17-characters-per-line format. This was the standard script in Buddhist scrolls from the late sixth century onward, and throughout the Tang period. The sūtras were among the most popular Mahāyāna scriptures, such as the Miaofa lianhua jing 妙法蓮華經 (Lotus Sūtra), Jin’gang bore boluomi jing 金剛般若波羅蜜經 (Diamond Sūtra), Da banniepan jing 大般涅槃經 (Great Parinirvāṇa Sūtra), Da bore boluomiduo jing 大般若波羅蜜多經 (Great Sūtra of the Perfection of Wisdom) and Jin guangming zuisheng wang jing 金光明最勝王經 (Golden Light Sūtra). Besides scriptures, there are only occasional examples of other types of Buddhist writings, such as the Da zhidu lun 大智度論 (Great Wisdom Treatise) in P.2739 or the Apidamo shunzhengli lun 阿毘達磨順正理論 (Treatise Conforming to the Correct Logic of Abhidharma) in P.2745 and P.2834. Yet even these normally feature a similar layout and calligraphy, accentuating the visual consistency of the Chinese side of the scrolls.

This relative uniformity could have been the result of two distinct scenarios. The first is that this was the type of manuscript—typically scrolls of popular Mahāyāna scriptures—accessible to Khotanese visitors. A possible reason for this is that a considerable portion of manuscripts surviving from before the tenth century were just these types of manuscripts. In other words, the uniformity of the scrolls was not the result of selection on the part of Khotanese individuals but a function of the available material, which in turn may have been the result of the type of manuscripts produced in Dunhuang during the period leading up to the time of close contacts with Khotan. According to this interpretation, the scrolls were valued solely for their physical material and their reuse was motivated by the scarcity of paper in the region.

The other scenario, advocated in this paper, is that Khotanese visitors showed a clear preference towards certain types of Chinese manuscripts. They deliberately chose sūtra scrolls from a larger pool of material available to them, and in doing so, they were to some extent motivated by piety. In reusing the sūtras, they were hoping to benefit from the spiritual efficacy of those, rather than aiming to economise on the cost of paper. Put differently, the scrolls were reused not exclusively for their paper, but just as much, or even more so, for the power they possessed. This explanation refocuses on the religious significance of scriptures, contending that they retained some of their value even as their primary function—and at times their physical form—changed. They were not waste but sacred objects that kept their potency while being re-appropriated for new purposes.

Finally, it is worth considering a third possibility, namely, that Khotanese visitors wrote their texts not only on the verso of sūtra scrolls but also on blank paper, even if those writings did not survive. Such posterior selection could have been related to the type of texts placed inside the Dunhuang library cave, which principally contained sūtra scrolls, as well as miscellaneous fragments collected with the aim of conserving them. When the cave was sealed in the early eleventh century, the Khotanese texts other than those on the verso of Buddhist scrolls may have simply not been deposited inside.

2 If this was indeed the case, the Khotanese writings owe their survival to having been written on the verso of sūtras. This scenario, however, does not explain why the Khotanese visitors did not write on the verso of other types of Buddhist texts, which were also preserved in the cave.

2. The Great Parinirvāṇa Sūtra and Diamond Sūtra

To illustrate the reuse of Chinese scriptures for writing Khotanese texts, let us examine manuscript P.2741 from the Pelliot collection in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

3 The verso contains the draft of a letter sent from Dunhuang by the Khotanese envoy Thyai Paḍä-tsä to the Khotanese court.

4 The letter recounts an eastward journey through Shazhou 沙州 (Dunhuang) to Ganzhou 甘州 (modern-day Zhangye 張掖) and describes the chaotic conditions in the region, including the movements of various tribes. The envoys intended to proceed to China proper, but became stranded in Ganzhou, where they witnessed a series of violent events such as the siege of the city, widespread famine and a series of killings. As this and other letters testify, the delegation also attempted, ultimately without success, to escort seven Khotanese princes to China. These documents were written within a span of less than a year and record events unfolding at the beginning of the tenth century.

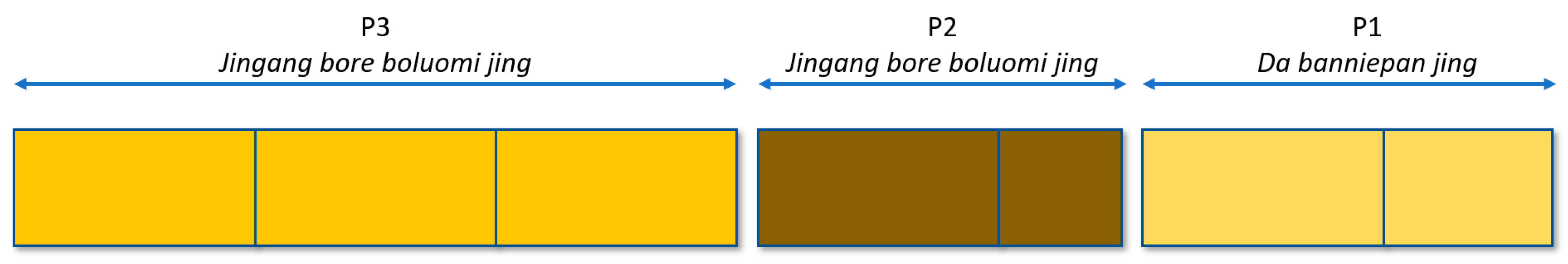

5In its present form, P.2741 measures 2.8 m in length and is composed of seven sheets of paper. Even a cursory inspection is able to reveal that it is not a single, continuous manuscript but a composite object made up of three separate fragments, each comprising two or three sheets. The heterogeneous nature of the scroll is particularly evident in the differing paper tones of the three parts and the changes in handwriting. For the sake of convenience, I refer to these parts (from right to left) as P1, P2 and P3. Their size and position within the composite scroll are displayed in

Figure 1.

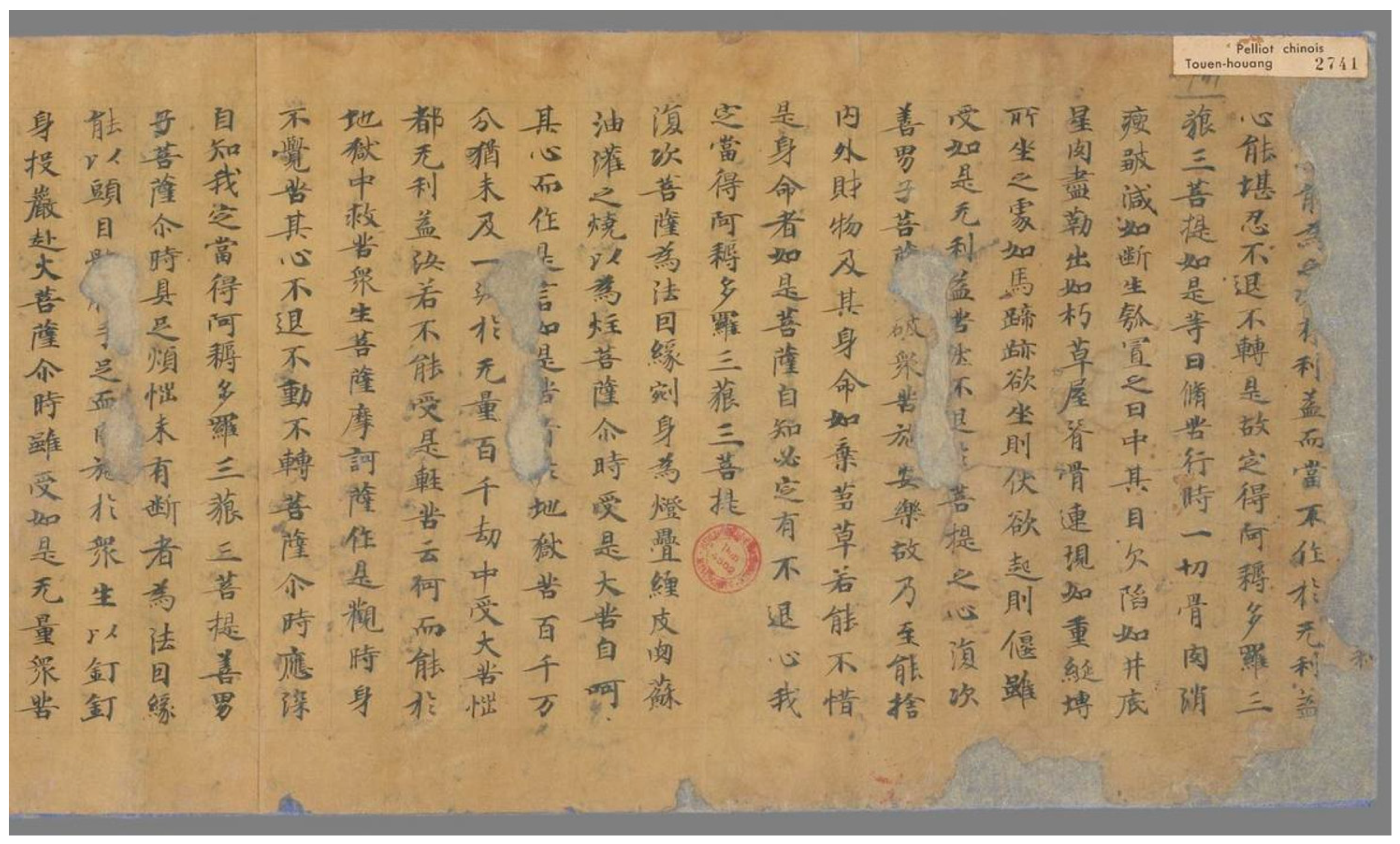

P1 is composed of two sheets joined together in a skillful and professional manner. The first sheet is missing the beginning and is slightly shorter, but the second one is complete. The style of calligraphy indicates that the copying could not have taken place earlier than the beginning of the seventh century. A conspicuous feature of P1 is a sequence of holes occurring at regular intervals of every six to seven lines, gradually diminishing in size (

Figure 2). This pattern is characteristic of damage sustained by a scroll while rolled up, producing a tapering series of perforations. In fact, the shape of the tear along the right edge of P1 reveals that the tear must have been caused by the same damaging event that created the subsequent holes. In this sense, the tear constitutes the first hole in the sequence. Notably, the holes do not extend into P2, proving that the damage occurred when P1 still existed as an independent scroll. This observation is of importance because this may have been the damage that made P1 reusable in the first place.

The text in P1 is a section from the

Da banniepan jing, translated by Dharmakṣema (Ch. Tanwuchen 曇無讖, 385–433). This scripture was exceptionally popular in Dunhuang, as evidenced by the large number of copies recovered from the library cave, many of which predate the Tang period. In the early period, it was arguably the most widely copied sūtra in Dunhuang, produced by both lay devotees and monastics.

6 The passage in P1 corresponds to

juan 32 of T.374, known as the ‘Northern version’ of the text. The same passage, with minor differences, also appears in

juan 30 of T.375, the revision of Dharmakṣema’s translation undertaken by Huiyan 慧嚴 (363–443) and others, which is commonly referred to as the ‘Southern version’. Overall, P1 aligns closely with the text of T.374, aside from a few inconsequential variants.

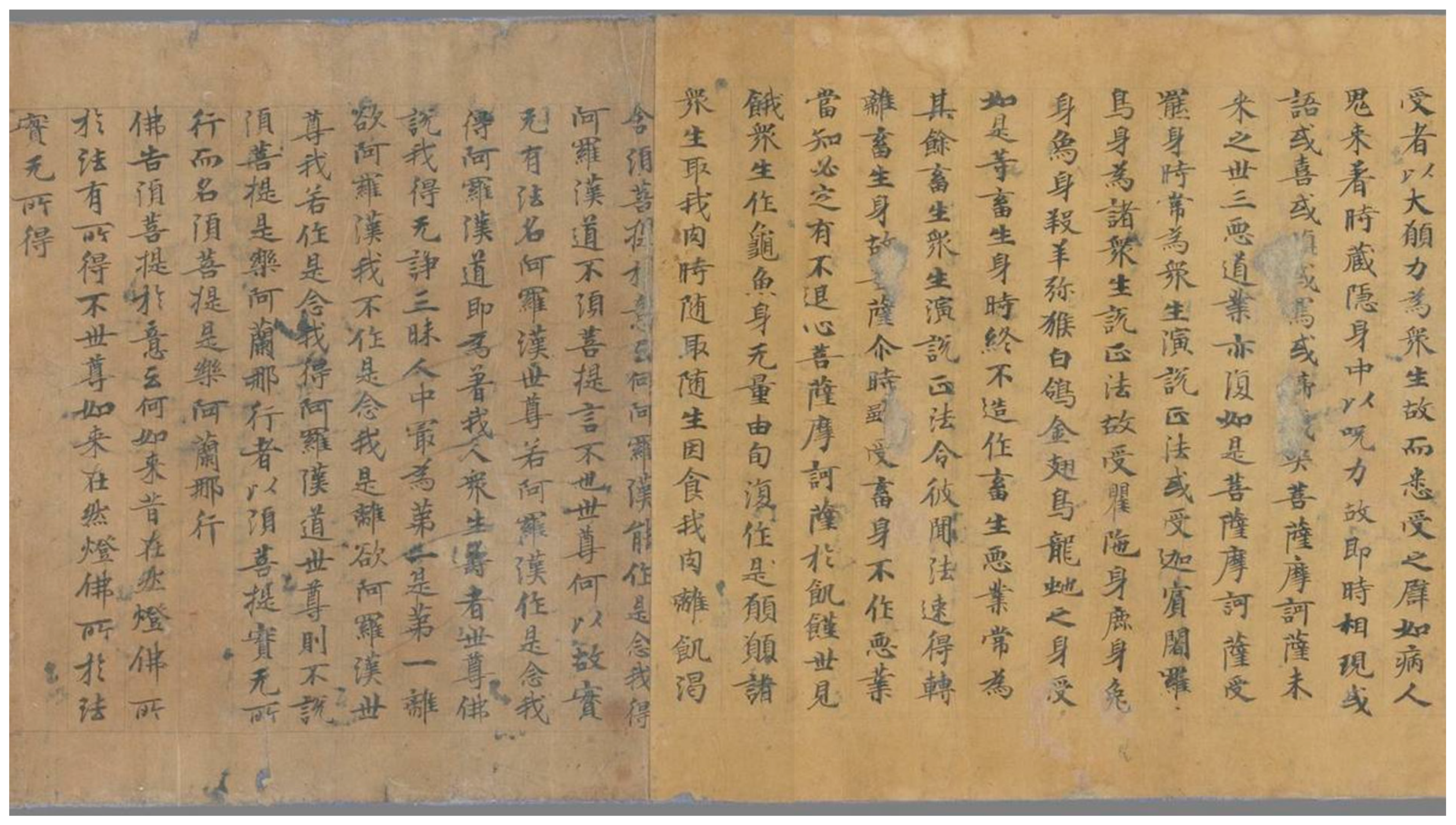

7Moving further to the left in P.2741, the ochre-coloured paper of P1 gives way to the darker brown tone of P2 (

Figure 3). The contrast is obvious and immediately signals a disruption, which is further confirmed by the change in handwriting. In itself, the shift in paper colour within the same scroll is not unusual, as there are many Dunhuang manuscripts with similar variation.

8 What is more striking here is the abrupt change in textual content: the

Great Parinirvāṇa Sūtra is followed without transition by Kumārajīva’s (Ch. Jiumoluoshi 鳩摩羅什, 344–413) translation of the

Diamond Sūtra (

Jin’gang bore boluomi jing 金剛般若波羅蜜經). Despite these differences, both P1 and P2 are written in regular

kai script, follow the 17-character-per-line format and share a broadly similar layout and overall appearance.

P1 and P2 are joined together rather clumsily, in a way that the first line of P2 slants to the right and is increasingly obscured underneath P1. On the left side, the seam between P2 and P3 shows untidy traces of glue (

Figure 4). Even within P2 itself, the two sheets are connected in a rushed manner, with the first line of the second sheet noticeably slanting to the right. The pattern that emerges is clear: in both P1 and P3, the sheets were joined with care, likely by trained craftsmen, whereas in P2 they were assembled with far less precision.

9 As for the creation of the composite scroll P.2741, the three constituent parts—P1, P2 and P3—were evidently glued together hastily by someone without adequate training or the motivation to do this with care. The result is a makeshift, home-made construction with little regard for quality or visual coherence, which is consistent with the idea of it having been glued together for the sake of reuse.

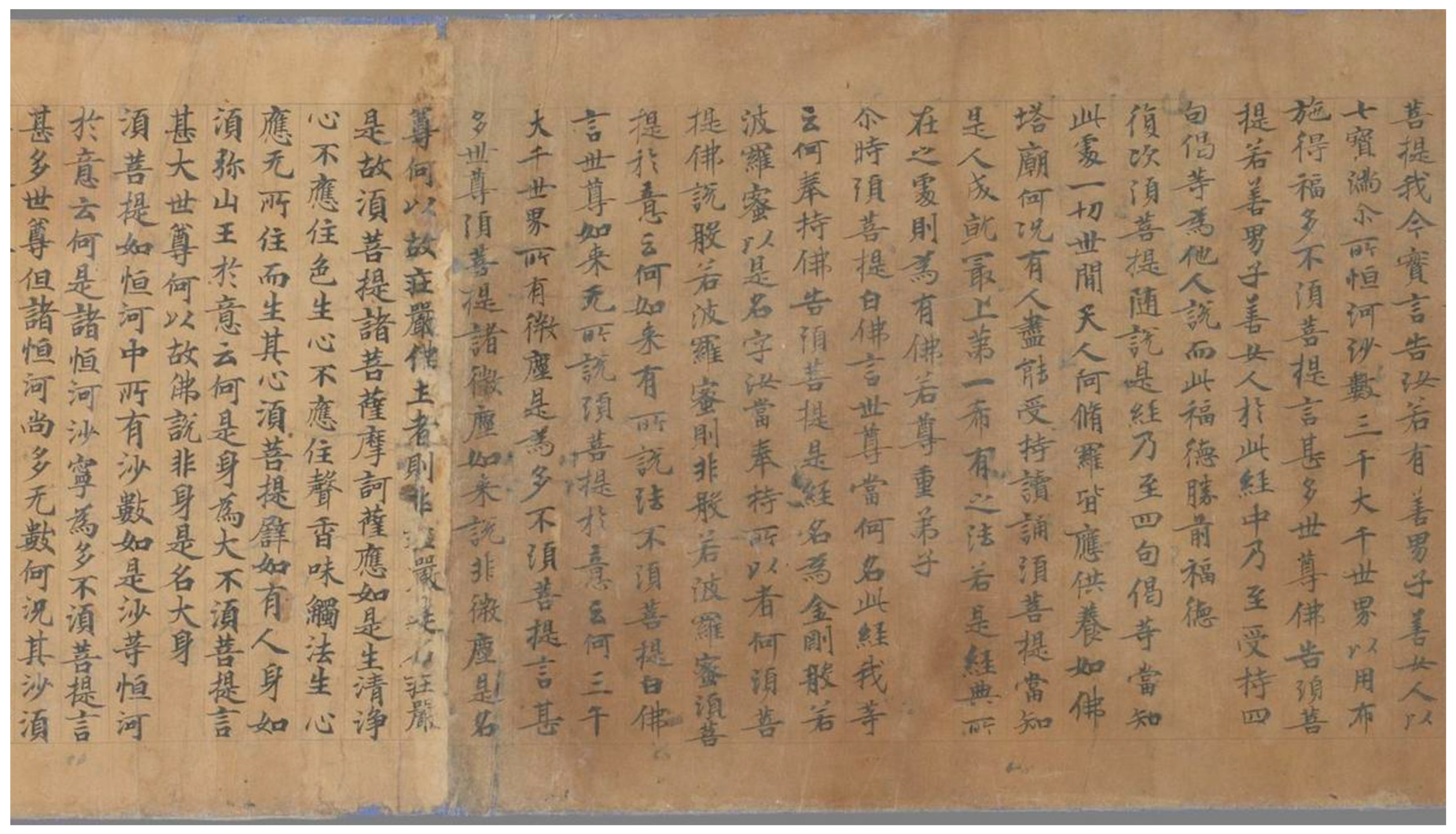

The transition from P2 to P3 is once again marked by an abrupt change in paper colour, returning to a lighter ochre tone (

Figure 4). The handwriting is similar but not identical, showing that P3 once also existed as a separate manuscript. Although the text in P3 continues the

Diamond Sūtra, it does not resume from where P2 ends. Instead, it begins almost a full sheet earlier, repeating a substantial portion of the text already present in P2. Despite this obvious overlap, the person who assembled the scroll made no effort to correct or conceal the glitch, even though it would have been apparent to even a superficial observer. Evidently, the compiler had little interest in restoring the text of the scripture and did not view the discontinuity as a problem.

P3 is the longest of the three parts of P.2741, accounting for nearly half of the scroll’s total length. It consists of three complete sheets (each with 28 lines), coming from the central section of the sūtra. None of the three parts of P.2741 is complete, and the text is not continuous from one part to the next. As a scroll, P.2741 is heterogeneous not only in structure but also in its content. Presumably, the person who pasted the three scrolls together in this manner was hoping to maximise the available blank writing surface on the verso, ensuring sufficient space for the Khotanese text. Indeed, the verso of P.2741 is entirely covered with Khotanese writing, which also proves that the Khotanese text was added only after the three parts had been assembled into a single scroll.

P.2741 is, of course, not the only instance with the

Diamond Sūtra presented in a non-consecutive form. A particularly noteworthy example is the three printed copies of the text (Or.8210/P.11, P.4515 and P.4516), each folded into a small concertina booklet. According to the colophons preserved in two of the copies, the printing was commissioned in 950 by Cao Yuanzhong 曹元忠 (r. 944–974), Military Commissioner of the Guazhou-Shazhou 瓜沙州 region. Each booklet contains only a fraction of the complete text of the

Diamond Sūtra, amounting to fewer than three of its thirty-two sections. Yet in their present form, the booklets appear to be complete and intentional artefacts, arranging the text in an abbreviated form by design rather than as a result of loss or damage (

Galambos and Wang, forthcoming).

Something that directly links the printed booklets of the Diamond Sūtra to Khotan are the words ‘written and sealed by the Heavenly Empress’ 天皇后書封 on the back of P.4516. Stamped over this note is the empress’s seal. The title ‘Heavenly Empress’ refers to the wife of the Khotanese king Li Shengtian 李聖天 (r. 912–962/966/967), who was also the sister of Cao Yuanzhong. These officially printed booklets confirm that, at this time, the Diamond Sūtra could be used in such a non-consecutive way. Despite the fragmentary nature of the text, the booklets were meant to bestow blessings and protection on the ruler and its domain. In a sense, these copies recycled the text of the scripture, repurposing it in a new and creative way to harness its efficacy. It is clear that the text was not meant to be read, or rather, this was not its main function.

3. The Sūtra of Limitless Life

A fascinating aspect of the reuse of Chinese sūtra scrolls for Khotanese content is the substantial time gap that often exists between the two sides. Most Khotanese writings from Dunhuang are thought to date to the tenth century, or at most the late ninth. Yet many of the sūtra scrolls they used were copied before or during the Tibetan control of the region (786–848), in the seventh, eighth, or first half of the ninth century. This means that Khotanese visitors were sometimes writing on scrolls that were over a century old. Once again, such a practice makes it less likely that the sūtras were selected randomly. Rather, it points to a deliberate preference for older manuscripts, especially since newly produced manuscripts would have presumably been more readily accessible.

Because explicit dates are rare in this body of manuscripts, it is often difficult to determine the exact time gap between the copying of a sūtra scroll and the writing added on the verso. One case in which the temporal difference is more apparent is in manuscripts of the

Sūtra of Limitless Life (

Dacheng wuliang shou jing 大乘無量壽經, T.936). The translation of this text is attributed, perhaps incorrectly, to the famous bilingual teacher and translator Wu Facheng 吳法成 (Tib. ’Go Chos grub, d. ca. 864) (

Dotson and Doney 2025, p. 86). The distinctive layout of these scrolls shows that they were produced as part of a sūtra-copying project organised during the 820s, with some manuscripts possibly copied as late as 844.

10 The sūtras were intended as a gift to the Tibetan emperor and were primarily copied in Tibetan, although the number of surviving Chinese copies is also substantial.

11 Contrary to the original plan, they never reached Central Tibet but remained in Dunhuang (

Dotson and Doney 2025). Brandon Dotson and Lewis Doney describe their function as follows:

The manner in which they were wrapped up en masse in bundles of twenty to one hundred rolls suggests that reading and chanting these sutras was secondary, and that holding and storing them was primary. Thus in these temples, and in temples all over the Tibetan Empire, the sutras likely would have been kept mostly unread—as sacred objects that offered blessings and protection and relics of the meritorious act of copying that had produced them.

In other words, these sūtras were not meant to be read or recited. They could be simply deposited in a temple, and by virtue of their physical presence they fulfilled their function as sacred objects. Yet despite their intended function, decades after their original production, long after the end of the Tibetan period, some of them were reused for writing Khotanese. A concrete example is manuscript P.2740 + IOL Khot S 5, a scroll originally consisting of four sheets, the first of which later became detached.

12 The verso contains partly corrupted—or hybridised—Sanskrit verses written in the Khotanese Brāhmī script, accompanied by Khotanese annotations.

13 What makes the content especially valuable is that it includes part of an early version of the

Ratnagotravibhāga (Ch.

Baixing lun 寳性論) (

Bailey and Johnston 1935;

Kanō 2012;

Kano 2016, pp. 24–7).

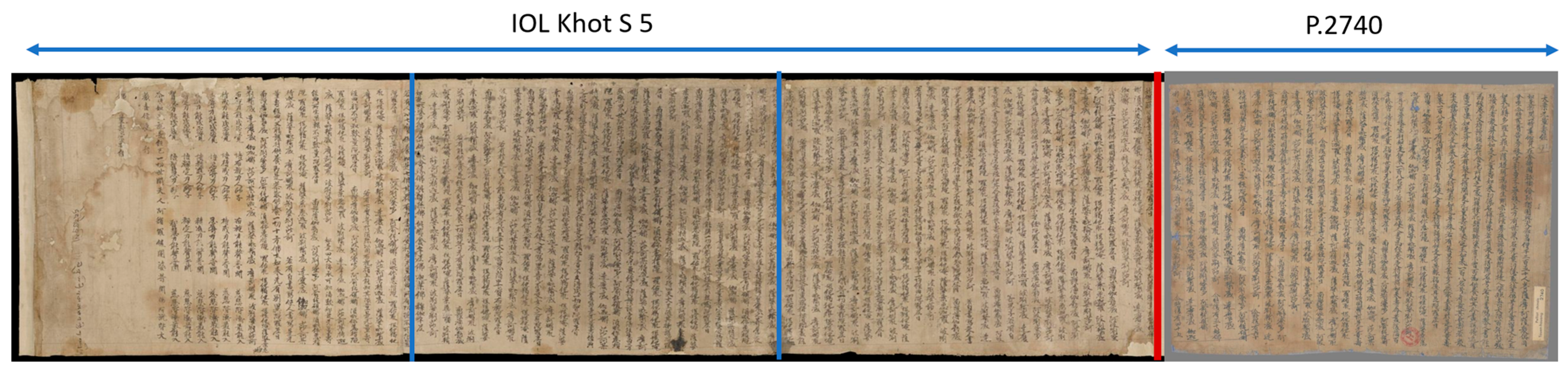

Figure 5 shows the entire length of the re-joined scroll with the Chinese text of the

Sūtra of Limitless Life. The boundary between P.2740 and IOL Khot S 5 is marked in red, whereas the internal seamlines between individual sheets are indicated in blue.

Neither side of the scroll contains a date, but the sūtra is followed by a short colophon in Tibetan, identifying Heng je’u and Le’u as the scribes who copied the text. Despite being written in the Tibetan script, both names are Chinese, as is the text of the sūtra. Of the two scribes, Heng je’u also features in several colophons to Tibetan copies of the

Sūtra of Limitless Life (Kanō 2012, p. 170 and

Kano 2016, p. 25. For specific examples, see

Dotson and Doney 2025). Phonetically, Heng je’u can be linked with Xingchao, the personal name of a certain Cao Xingchao 曹興朝, whose signature appears in several Chinese copies of the sūtra, as well as at the end of two other scriptures.

14 The repeated occurrence of this relatively uncommon name in both Chinese and Tibetan copies of the

Sūtra of Limitless Life suggests that Cao Xingchao and Heng je’u denote the same scribe.

Possibly another instance of a Tibetan transcription of the same Chinese name is in manuscript S.3762, which contains a name that Lionel Giles reads as Heng de’u (

Giles 1957, p. 150). The manuscript has not been digitised and unfortunately cannot be examined in person because of its fragile condition.

15 Considering that, to my knowledge, the name Heng de’u does not occur anywhere else in the Dunhuang corpus, while Heng je’u features repeatedly,

16 it is likely that the former is simply a misreading of the latter and both refer to Cao Xingchao.

Another name that features in both scripts in Chinese (e.g., S.339, S.1838 and S.1872) and Tibetan copies of the

Sūtra of Limitless Life is Lü Rixing 呂日興. This scribe usually signed his name in Tibetan manuscripts as Lu Dze shing or Lu Tse shing, although occasionally even in Tibetan manuscripts he used Chinese characters for his name (

Dotson and Doney 2025, pp. 134, 159–60).

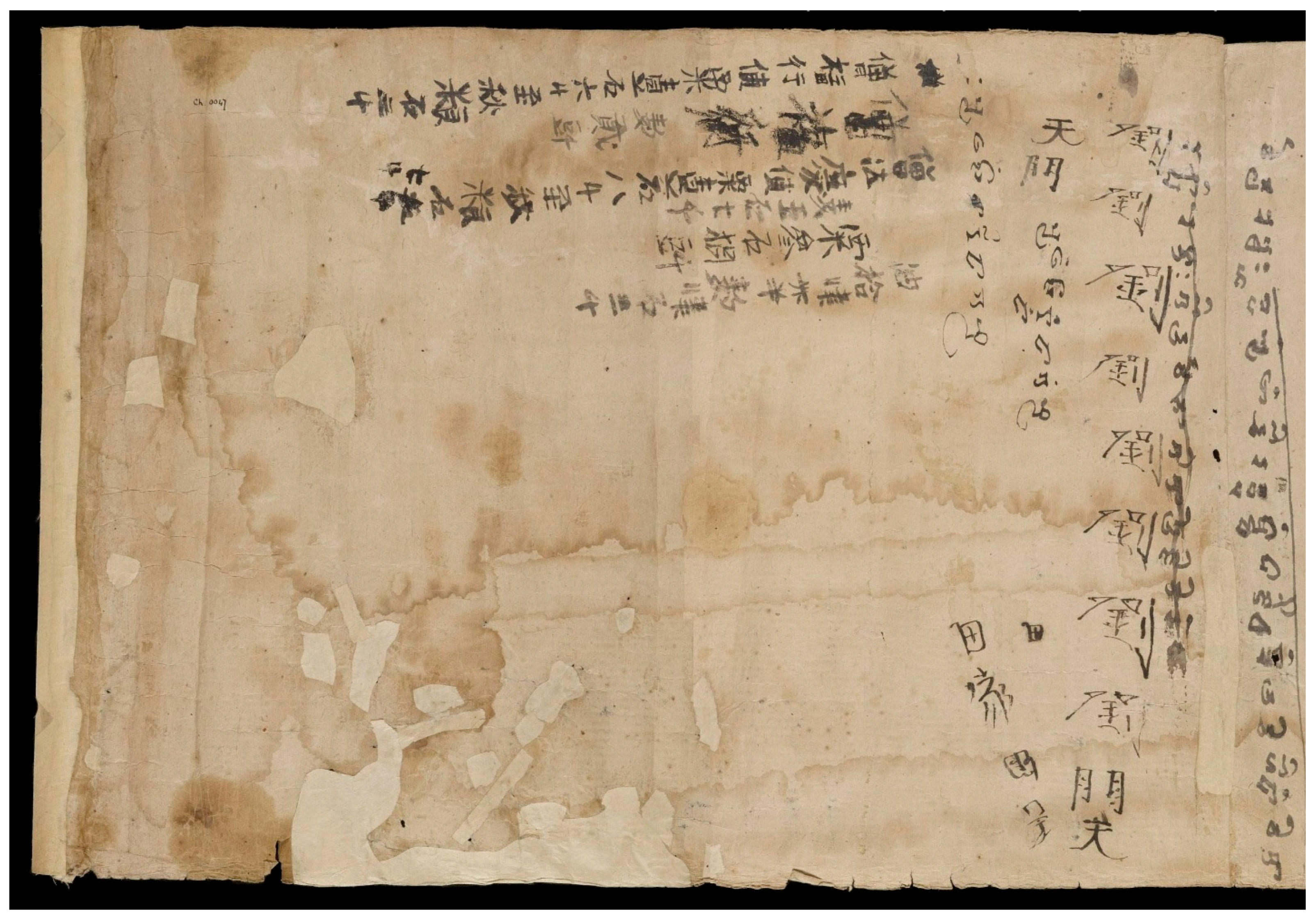

In IOL Khot S 5, the verso of the last sheet only contains three fragmentary lines of Khotanese text, leaving most of the surface blank. This leftover space contains several Chinese notes from a contract for the loan of grain (

Figure 6). The Chinese lines do not constitute a full document but are notes or excerpts written in a decidedly rudimentary hand, perhaps by a student or someone inexperienced in writing Chinese. In addition to this, the surname Liu 劉 is written eight times, without any context, in a line running perpendicular to the contract fragments. The repetition indicates a simple writing exercise. Based on their location relative to the Khotanese lines, the scribbled Chinese notes must have been added sometime after the Khotanese content had already been written on the verso. Kazuo Enoki notes that these characters were written with the same pen as the Khotanese text (

de la Vallée Poussin 1962, p. 265). If he is correct, then the time gap between the two languages would have been minimal. The Chinese characters

liu 劉,

tian 天,

men 門 and

tianjia 田家 are written in an idiosyncratic way, resembling the large character

chi 敕 in manuscript P.5538, containing the letter written by the Khotanese ruler Viśa’ Śūra (r. 967–977/978) in 970 to his maternal uncle Cao Yuanzhong.

17 The similarity in the style of characters suggests that these characters in IOL Khot S 5 were also written by a Khotanese person.

The above examination makes it possible to reconstruct the sequence in which the different layers of text were added to the scroll. Initially, four sheets were prepared and ruled for copying the Chinese version of the

Sūtra of Limitless Life. At a later stage, the scroll was reused, and the Khotanese text was written on the verso. The few practice-like Chinese characters were probably also added at this time. The Chinese lines relating to a contract were written after this, at some other point in time (

Kanō 2012, p. 956). The Chinese lines could not have been written after the scroll fell apart, because the verso of P.2740 contains four or five random-looking Chinese characters written in the same untrained hand as on the verso of IOL Khot S 5. Among these characters, the phrase

tian jia 田家 appears in both manuscripts, further proving the connection.

18 The final episode in the scroll’s history occurred when its first sheet became detached from the other three. From there on, the two parts were no longer kept together, which explains why M. Aurel Stein only acquired IOL Khot S 5, being unaware that he left behind another part of the same scroll. A few months later, Paul Pelliot purchased this other part and eventually shipped it back to Paris, where it became catalogued as P.2740.

That the reuse of the

Sūtra of Limitless Life for writing Khotanese texts was not entirely accidental is demonstrated by other comparable manuscripts. One of these is P.2898 + IOL Khot S 18 (Ch. 00327), the two parts of which likewise ended up in Paris and London. The recto contains the Chinese sūtra, while about a quarter of the blank space on the verso is taken up by a letter written by a Khotanese official in Dunhuang (

Kumamoto 2007, p. 2). Another example is IOL Khot S 6, the verso of which contains the

Pradakṣiṇā-sūtra and notes concerning Khotanese envoys in Shazhou.

19To be sure, Khotanese is not the only language found on the verso of scrolls with the

Sūtra of Limitless Life. For instance, manuscript P.3134, copied by a scribe named Zhang Yaoyao 張曜々, includes about two dozen lines of accounts of woolen cloth written in Sogdian with an admixture of Uyghur words (

Sims-Williams and Hamilton 2015, pp. 27–36). This shows that similar patterns of reuse, involving a combination of Chinese and Central Asian languages, were not an uncommon practice in Dunhuang during the long tenth century. Nonetheless, it is worth emphasising that amidst the more than a thousand Chinese copies of the

Sūtra of Limitless Life, such examples are not common.

The Chinese and Tibetan copies of the Sūtra of Limitless Life were produced as part of large sūtra-copying projects commissioned by the Tibetan authorities during the first half of the ninth century. Since the Khotanese texts on the verso were written in the tenth century, there is an obvious time gap between the two sides of these scrolls. In other words, in many cases, Khotanese visitors and residents of Dunhuang deliberately chose very old, one could say antique, scrolls. This pattern also applies to many of the sūtras produced during the Tang period, which were even further removed in time. In both cases, new texts were written on scriptures that were not only old but presumably also valuable.

4. The Reuse of Manuscripts

The fundamental question is whether the Khotanese visitors chose old scrolls as writing surfaces because they had limited access to new paper, which would have been difficult to obtain and expensive. One problem with a purely economic model is that it overlooks the religious significance of the texts involved, treating Buddhist scriptures as no different from other forms of writing. It assumes that damaged or obsolete scrolls had already become discarded waste, valued solely for their physical material. Yet the fact that these manuscripts were preserved and stored in large quantities for decades, or even centuries, before being used for new purposes, suggests that local communities continued to attach value to them. Had the cost of paper been the primary concern, the old sūtras could have easily been re-pulped to produce new sheets with both sides blank, doubling the available writing surface and simultaneously also eliminating the unwanted text.

Another consideration is that the overwhelming majority of Dunhuang manuscripts were produced during the ninth and tenth centuries—the very period in which the instances of reuse discussed in this paper occurred. The contents of the Dunhuang library cave represent the largest extant body of written material from premodern China, comprising tens of thousands of manuscripts written in Chinese, Tibetan and more than a dozen other languages. The Chinese manuscripts alone number approximately seventy thousand items, and the total corpus in all languages likely exceeds one hundred thousand. Although this figure includes a substantial number of fragments, these too originally began their existence as complete manuscripts, testifying to the massive scale of manuscript production during this period.

20 As in any manuscript culture, reuse undoubtedly remained a common practice, but this does not negate the fact that paper was manufactured on a large scale. Like any commodity, the price and availability of paper would have varied according to its quality and current market conditions, and contemporary sources occasionally complain of it being expensive or not readily available. Even so, recyclable paper could have been obtained through channels other than monastic repositories of obsolete sūtras, suggesting that economic necessity alone cannot account for the patterns of reuse observed here.

There are also numerous cases in which the Khotanese text does not make use of the full length of the underlying sūtra. Manuscript S.6701 measures approximately 5.6 m in length yet contains only about twenty lines of Khotanese text on the verso. Similarly, the 7.5 m long S.2469 carries merely seven lines of Khotanese. In both instances, nearly the entire available writing surface was left blank. Although it is possible that additional texts were intended to be added at a later stage, the manuscripts in their present state do not reflect a resource-conscious use of the available space.

The question, then, is whether the Khotanese visitors to Dunhuang had a preference for sūtra scrolls. The first step toward addressing this issue is to recognise that manuscript reuse was by no means confined to this admittedly small community active in the long tenth century. On the contrary, reuse is an intrinsic feature of manuscript cultures across periods. A substantial proportion of the manuscripts from the Dunhuang library cave bear traces of some form of repurposing, ranging from writing on the recto of existing scrolls to cutting up old sheets and refashioning those into codices. Furthermore, this phenomenon was not peculiar to Dunhuang or to any specific region of China: comparable practices are attested across East and Central Asia, in cultural contexts as far apart as Japan and the Uyghur kingdom of Gaochang 高昌.

In fact, manuscript reuse was just as common in the West, from ancient Egypt to medieval Europe and the Middle East.

21 As Elena L. Hertel writes, ‘papyrus manuscripts were reused throughout ancient Egyptian history, making the reuse of papyri a phenomenon as old as their use’ (

Hertel 2025, p. 335). Indeed, the impression one gets from manuscript cultures around the world is that use and reuse were two sides of the same coin; manuscript production went side by side with manuscript reuse. Reuse was not always an expediency necessitated by economic circumstances but an integral part of all scribal cultures. Although purely in monetary terms, parchment was certainly more expensive than papyrus, manuscripts made of both types of material were repurposed just as frequently for the creation of new manuscripts. For this reason, it is more constructive to regard reuse not as a practice driven by external necessities but ‘as a normal component of different use modes’ (

Hertel 2025, p. 352).

In East and Central Asia, sūtra copying formed part of the everyday practice of Buddhist communities, and there are illuminating examples of manuscript reuse not being motivated by economic concerns. Halle O’Neal discusses Japanese ‘letter-sūtras’ (

shō-sokukyō 消息経), memorial scrolls produced for rituals commemorating the dead. Describing them as ‘memorial palimpsests’, she explains that mourners created ‘these textually layered compositions by reusing and even recycling the dead’s handwritten traces as paper for the transcription of sacred Buddhist texts (sutras)’ (

O’Neal 2024, p. 509). This often involved copying scriptures such as the

Lotus sūtra onto paper repurposed from letters written by a deceased parent. Because this practice was largely confined to elite circles, including the imperial family, the cost of paper could hardly have been a motivating factor. Rather, the reuse of letters constituted a deliberate requisition of a deceased loved one’s handwriting for salvific ends. Significantly, as the letters were being pasted together to form longer scrolls, they were often arranged out of sequence and at times even trimmed, suggesting that although the handwriting itself was intentionally made visible, legibility and communicative function were consciously subordinated to the ritual purpose of the new context (

O’Neal 2024, p. 513).

Unlike the Sino-Khotanese scrolls from Dunhuang, in the Japanese ‘letter-sūtras’ the scripture represented the secondary layer, written over a pre-existing textual substrate. There are, however, also closer parallels in which the scriptures themselves were repurposed as writing supports for new content. Lucia Dolce analyses a printed copy of the

Chū Hokekyō 註法華經 (

Annotated Lotus Sūtra) owned by Nichiren 日蓮 (1222–1282), who created a dense matrix of interlaced text by writing in the blank spaces in the margins and between the printed lines. As Dolce reminds us, Buddhist scriptures are ‘objects imbued with power, continuously activated through performative actions: reciting, copying, or simply holding them’ (

Dolce 2023, p. 41). Yet Nichiren made extensive use of the empty space in the eight printed scrolls to record a wide range of quotations from other texts. Beyond illustrating the intriguing interplay between print and handwriting, this example demonstrates that even highly devotional objects could undergo shifts in function over the course of their life cycle.

22Naturally, comparable examples can also be found among other clusters of Dunhuang manuscripts. Approaching manuscript reuse from the perspective of whether old manuscripts were ever conceptualised as ‘waste’, Li Channa examines two

pothī manuscripts containing multiple layers of Tibetan and Chinese text. Her analysis of their contents demonstrates that the two items originally formed a single manuscript and that the various layers are both structurally and conceptually interrelated. Whereas earlier scholarship interpreted these layers as unrelated texts produced through recycling a discarded manuscript, Li convincingly argues that they developed through a deliberate and sustained engagement with the earlier textual strata (

Li 2022). Each textual cluster served a distinct function, yet together they formed a coherent whole centred on the Vinaya. For the community that produced them, therefore, these manuscripts were neither discarded nor treated as waste.

5. Conclusions

Reuse is often understood as the repurposing of an unwanted or discarded object for a new function. Such an understanding presupposes that the object has lost its original value, or that it retains value only in a partial or residual sense. In modern scholarship on Dunhuang, manuscript reuse is therefore frequently explained in terms of paper scarcity and cost-saving strategies. If this were indeed the case, and old manuscripts were valued solely for the blank surface they provided, their existing textual content would have been treated as an inconvenience to be removed or obscured. Yet there is little evidence to support this view. Even when Chinese scrolls were reused for writing Khotanese, Tibetan, or other languages, the Chinese side was in most cases left fully visible, with no apparent attempt to erase, cover or suppress the earlier text.

Most of the scrolls reused by Khotanese visitors were incomplete or damaged, a condition that may have rendered them more acceptable for reuse. Yet their content was neither destroyed nor erased, nor was it deliberately concealed. In this sense, the process of reuse did not amount to an act of desecration or disposal. Rather, it involved a transformation of function that preserved the sacred text and privileged continuity over replacement.

As the comparative examples discussed above demonstrate, manuscript reuse was not a local response to material scarcity but an intrinsic feature of manuscript cultures in general. In many contexts, reuse entailed a deliberate and often creative engagement with existing textual artefacts, rather than a pragmatic attempt to economise on writing material. What makes the Sino-Khotanese scrolls from Dunhuang particularly interesting is that they entail the reuse sūtras to record contents of a lower degree of sacrality. This is all the more striking given that the Khotanese themselves were Buddhists and Khotan was famous as a centre of Buddhist faith. The continued visibility of the Chinese scriptures thus suggests that they remained an acknowledged and meaningful presence throughout the manuscripts’ subsequent use.

This is not to deny that economic considerations may at times have played a role. They cannot, however, have been the primary motivation in all cases, nor are they sufficient on their own to explain the practice of manuscript reuse. Paper may have been valuable, at times even expensive, but not prohibitively so. This is evident from the quantity of manuscripts produced in Dunhuang during the ninth and tenth centuries. Many manuscripts were copied by individuals of modest means, and the often mundane nature of their writings indicates that paper was affordable enough to be used for texts of limited significance. By contrast, old sūtras written in fine calligraphy, particularly those produced as part of centralised sūtra-copying projects, must have possessed a value far exceeding that of blank paper. The Khotanese officials and envoys who travelled to Dunhuang belonged to elite circles and would have likely had the means to acquire new paper when needed.

The Sino-Khotanese scrolls present a striking constellation of binary oppositions, juxtaposing the two sides at multiple levels. Most immediately, these manuscripts are bilingual objects that bring together distinct linguistic systems: Chinese, belonging to the Sino-Tibetan language family, and Khotanese, an Indo-European language. This binarity is mirrored at the level of the script, in the contrast between the discrete characters of the Chinese sūtras and the cursive flow of Brāhmī text. The scripts also differ in orientation and directionality: the Sinitic script is written in vertical columns from right to left, whereas the Brāhmī lines read in horizontal lines from left to right. Their cultural trajectories likewise diverge, the former rooted in the Chinese heartland of East Asia, the latter ultimately deriving from the Aramaic alphabet of West Asia.

Taken together, the bilingual scrolls testify to how, in tenth-century Dunhuang, the Sinitic heritage of the former Tang empire intersected with the Saka culture of Khotan. In the case of the copies of the Sūtra of Limitless Life, the blend was further complicated by the presence of a Tibetan substratum: the Chinese text was copied during the period of Tibetan control as part of an official sūtra-copying project and was intended as a gift to the Tibetan emperor. The Tibetan transcription of the names of Chinese scribes at the end of the sūtra exemplify the interpenetration of languages, scripts and cultural traditions.

In most cases, the two sides of the scrolls are also separated by a temporal gap, as the Chinese sūtras were typically copied well before the Khotanese text was added. The repurposed scrolls therefore provide a particularly clear illustration of how manuscripts can progressively accumulate layers of text and meaning over the course of their lives. By analysing each layer in sequence, it becomes possible to situate those within their respective historical contexts, reconstructing the manuscript’s complete biography. In the case of Dunhuang, the gradual accretion of textual material reflects the region’s political transformation, from the Tang era through the period of Tibetan rule and into the tenth century, when contacts with Khotan and the Uyghur states intensified.