Abstract

This article presents a multilevel framework for understanding religion as operating simultaneously at individual, interactional, and institutional levels. Drawing on the multilevel theory of gender as a conceptual parallel, it synthesizes existing perspectives in the sociology of religion into a coherent analytical framework. While many sociological theories implicitly recognize multiple levels, empirical research has typically focused on individual religiosity, treating religion primarily through measures of personal belief, behavior, and belonging. The 3I framework—individual, interactional, and institutional—makes this implicit multilevel thinking explicit, providing conceptual scaffolding for both theoretical development and empirical practice. The framework is illustrated through application to contemporary American religious change, revealing how apparently contradictory patterns of religious decline and spiritual persistence reflect differential change across levels.

1. Introduction

Is the world secularizing or is religion persistent or even resurgent? Scholars marshal evidence for competing claims: secularization theorists point to declining institutional participation while others highlight persistent individual belief and emerging forms of spirituality. This apparent contradiction dissolves when one recognizes that religion operates simultaneously at multiple levels of social reality—and that patterns across these levels can change at different rates and in different directions.

This parallels the multilevel theory of gender that emerged to conceptualize gender as something that structures social life. Gender operates not just as an individual attribute, but also as something people “do” that structures society (P. Y. Martin 2004; Risman 1998, 2004; West and Zimmerman 1987). At the individual level, people develop gendered selves. At the interactional level, they “do” gender through performances that others evaluate. At the institutional level, gender structures organizations and power arrangements. These three levels are analytically distinct yet interconnected: changes at one level need not translate to changes at another, yet patterns at each level shape the others. This resolved persistent puzzles: for example, women making educational gains as individuals while organizational hierarchies remained male-dominated reflects differential change across levels, not theoretical incoherence.

Religion similarly operates as a multilevel social structure. At the individual level, religion encompasses personal faith and private practices. At the interactional level, religion is something people do together—shared rituals and mutual affirmation or sanctioning of religious identities. At the institutional level, religion exists in organized form through denominations, hierarchies, and broader cultural norms. Patterns at one level can diverge from those at another: individual belief can persist even as institutional participation declines; new interactional forms can emerge outside formal organizations; institutional power can remain concentrated even as individual practices diversify. Recognizing these levels as analytically distinct while empirically interrelated provides conceptual scaffolding for understanding religious change, difference, and persistence.

This article makes explicit what many seasoned scholars already grasp intuitively. While the field’s veterans navigate the varied aspects of religion instinctively, newcomers do not always find this laid out explicitly in one place but have to pick it up and put it together. Existing multidimensional approaches to religious commitment provide important foundations but typically focus on different ways individuals experience religiosity rather than different levels at which religion operates as a social structure. I synthesize and extend this work, proposing the 3I framework—individual, interactional, and institutional—as analytical scaffolding for both theoretical development and empirical research.

This framework is more synthesis than innovation. The levels identified draw on work on other social structures, including gender, and can be found implicitly in existing theories about religion. Religious market theories invoke individual consumers, interactional goods, and institutional regulation (Finke and Stark 2005; Iannaccone 1991). Secularization theories address institutional differentiation, cultural authority, and individual belief (Berger 1967; Bruce 2002). Dobbelaere’s (2002) neosecularization framework explicitly distinguishes individual, organizational, and societal levels. Lived religion perspectives examine personal practices, communal expressions, and institutional constraints (Ammerman 2007, 2021; McGuire 2008). What has been missing is a systematic framework that makes multilevel analysis of the individual, interactional, and institutional levels central to how the field conceptualizes and studies religion. This parallels longstanding calls in sociology for more explicit theorizing of levels and their relationships (Coleman 1990; Hedström and Swedberg 1998).

I illustrate the framework’s utility through application to contemporary American religious change. I apply it to these patterns not because religious change or the United States are the only places to apply the framework—in fact, this framework could be illustrated in any number of ways in any number of societies and religious contexts—but simply because it is one of the most commonly debated topics in the sociology of religion given ongoing questions about secularization and questions about whether the United States is a counterexample to secularization hypothesis. Apparently contradictory patterns—institutional decline alongside spiritual persistence, disaffiliation coupled with continued belief, organizational exit accompanied by new forms of religious community—become comprehensible through a multilevel lens, revealing differential change across levels with institutional measures declining faster than individual ones and interactional religion transforming rather than disappearing.

2. From Multidimensional Religiosity to Multilevel Analysis of Religion as a Social Structure

The recognition that religion is multidimensional has deep roots. Glock (1962) developed a five-dimensional scheme for religious commitment encompassing belief, knowledge, experience, practice, and consequences. Stark and Glock (1968) later divided practice into ritual and devotional dimensions. These frameworks spurred other proposals and numerous empirical studies testing how different dimensions of religious commitment relate to one another and to other social phenomena (Clayton and Gladden 1974; Cornwall et al. 1986; Hill and Hood 1999). More recently, Ammerman (2021) has been advancing a multidimensional approach to religious practice emphasizing embodiment, materiality, emotion, esthetics, moral judgment, and narrative.

These multidimensional approaches made important contributions. They demonstrated that religious commitment cannot be reduced to a single measure, that belief and behavior need not align perfectly, and that different dimensions may relate differently to other social phenomena (Cornwall et al. 1986; Glock and Stark 1965). They pushed scholars beyond crude “religiosity scales” toward more nuanced operationalization. Contemporary survey research remains deeply indebted to this multidimensional tradition, particularly the widely used “three Bs” of believing, behaving, and belonging (Cadge and Konieczny 2014).

Yet these frameworks share a fundamental limitation: they focus largely on different dimensions of individual religiosity. The classic three Bs all measure individual-level religious commitment—what someone believes, how they behave, which group they belong to. Even expanded frameworks, while enriching understanding of individual religious experience, often remain centered on personal dimensions. These are individual-level constructs applied to individual-level phenomena.

This creates two problems. First, it can lead to conceptual slippage wherein religion itself, and our sense of what is happening with it in the world, becomes conflated with individual religiosity measured with a traditional set of items. When religion is operationalized primarily through surveys asking people about their beliefs, behaviors, and identifications, there is an implicit reduction of a complex social structure to its manifestation in individual lives. This echoes a broader tendency in sociology to reduce macro-level phenomena to aggregations of individual-level data—what Durkheim ([1895] 1982) warned against in insisting that social facts exist at the level of the social and cannot be reduced to the individual. It obscures how religion also operates through face-to-face interaction and institutional organization in ways not fully captured by aggregating individual responses.

Second, multidimensional approaches to individual religiosity often employ measures that only make sense in particular institutional contexts. Religious service attendance assumes congregation-based religion. Belief in God presumes monotheism. Denominational affiliation requires formal religious organizations with membership boundaries. These measures work reasonably well for studying modern monotheistic Abrahamic religion, and especially Christianity, in Western contexts, but prove limited for understanding religion in societies where it remains less differentiated from other spheres, or for examining religious forms that do not map neatly onto organizational templates (Cadge and Konieczny 2014; Nongbri 2013). The problem is not that these measures are wrong, but that their institutional embeddedness remains underexamined—they take a particular institutional configuration as natural rather than historically and culturally specific.

One must distinguish between multidimensional approaches to measuring individual religiosity and multilevel frameworks for analyzing religion as operating at different levels of social organization. This distinction connects to longstanding debates about levels of analysis and social ontology and provides a lens for big-picture conceptualization of religion across cultures and traditions.

Multidimensional religiosity examines different dimensions of how individuals are religious—belief, practice, identification, experience. These approaches recognize that religion is not unidimensional at the individual level, that someone might be high on belief but low on practice, or belong to a religious tradition without fully accepting its doctrines. These are typically phenomena at the individual level. The question is: “How religious are you and in what different ways are you religious?”

Multilevel religion examines religion as a social structure operating at different levels of social organization—individual, interactional, and institutional. These represent distinct analytical levels, not just different measures of the same level. The question is: “At what level of social reality is religion manifesting and in what ways?” This connects to longstanding debates about micro-meso-macro linkages and the relationship between individual action and social structure (Alexander et al. 1987; Coleman 1990).

Put concretely: asking about religious practices, beliefs, and identity captures different dimensions of individual religiosity—they are different, but just largely different types of individual level factors reflecting the multidimensional nature of personal religious commitment. In contrast, comparing personal prayer (individual level), communal worship (interactional level), and denominational hierarchies (institutional level) captures religion at multiple levels. The first distinguishes types of individual religious expression; the second distinguishes levels of social organization at which religion operates.

Even what might be seen as one type of practice in the multidimensional approach, prayer, can be performed in a variety of ways, reflecting multiple levels depending on context and framing. Prayer done alone is individual-level religion—a private practice. Prayer done together with friends is interactional-level religion—shared religious activity. Prayer that religious organizations require or structure (daily offices, scheduled prayer times) reflects institutional-level religion—organized prescription of practice. In some places, that becomes a part of the culture with calls to prayer over speakers that can be heard throughout a neighborhood or city. The same activity—prayer—manifests at different levels and can be informal and deeply personal or highly institutionalized or delineating creeds. This illustrates the duality of structure—practices that are both constituted by and constitutive of social structures (Giddens 1984).

Similarly with attendance: attending worship can involve multiple levels. At the individual level, it reflects personal commitment and choice, typically leading to participation in institutional religion. At the interactional level, it involves doing religion with others through shared ritual, what Collins (2004) analyzes as interaction ritual chains that generate emotional energy. At the institutional level, it represents engagement with organized religion, reproducing the institution through participation (Berger and Luckmann 1966). When patterns diverge—someone continues praying alone (individual) but stops attending services (institutional and interactional)—this reflects differential change across levels and could be seen as a deinstitutionalization of religious life (Putnam 2000; Schnabel et al. 2025).

This distinction matters for both theory and research. Theoretically, it helps avoid reducing religion to individual religiosity, recognizing instead that religion is constituted through interpersonal interaction and institutional organization—it is an “institutional fact” that exists beyond individual minds (Searle 1995). It connects to broader sociological insights about how social phenomena exist at multiple levels: individuals act, but those actions are shaped by interactional contexts and institutional structures, which are themselves reproduced or transformed through interaction and individual action (Sewell 1992).

Empirically, it directs attention to phenomena and processes that might otherwise be overlooked. It allows analysis of how different levels may change at different rates or even in different directions—essential for understanding contemporary religious transformation. Most importantly, it provides conceptual tools for bridging persistent divides in sociology between individual-level and structural analysis, between agency and structure, between micro and macro.

Multidimensional approaches to measuring individual religiosity remain invaluable for studying individual religious commitment. At the same time, they are not sufficient for capturing religion’s full complexity. What the field needs is not replacement of multidimensional frameworks, but their integration within a broader multilevel perspective that attends to individual, interactional, and institutional dimensions. This parallels broader calls in sociology for multi-level analysis that can link individual action to structural patterns without reducing one to the other (Hedström and Swedberg 1998; Gross 2009).

Although a multilevel frameworks have often been more implicit than explicit, multilevel thinking is already present in many theories. Dobbelaere’s (2002) neosecularization theory may be most directly parallel, distinguishing among individual, organizational, and societal levels. He examines declining personal religious belief and practice (individual level), how religious organizations adapt or decline (organizational level), and institutional differentiation with religion’s declining public authority (societal level). This explicitly multilevel approach has proven highly influential, particularly in European sociology of religion (Casanova 2007; Gorski and Altınordu 2008).

The 3I framework builds on Dobbelaere’s insights while offering refinements. Where Dobbelaere focuses specifically on secularization processes, the 3I framework provides a more general analytical scheme applicable to studying any religious phenomenon—not just changes in how religious people or the world are. The interactional level receives more explicit attention in the 3I framework, drawing on interaction ritual theory (Collins 2004) and practice theory to theorize how religion is actively accomplished through face-to-face engagement. And the framework more directly parallels the multilevel gender approach that has proven so productive in gender scholarship, facilitating theoretical cross-fertilization.

Religious market theory also embodies multilevel logic, though often implicitly (Finke and Stark 2005; Iannaccone 1991; Stark and Finke 2000). At its core lies individual-level religious “consumers,” interactional-level religious “goods,” and institutional-level “markets.” The theory works because it attends to dynamics at each level: how individual demand drives organizational supply, how institutional regulation constrains organizational competition, how successful organizations meet individual needs through compelling interactional experiences. This mirrors Coleman’s (1990) boat diagram of macro-micro linkages, though market theorists have not always been explicit about these levels.

Classical secularization theory similarly operates at multiple levels, though this remained largely implicit in early formulations (Berger 1967; Bruce 2002; Wilson 1982). The theory posits institutional differentiation (religion’s separation from politics, economy, education), declining cultural authority (religion’s diminished public influence), and individual secularization (declining personal belief and practice). More sophisticated neosecularization approaches recognize them as analytically distinct while theorizing their interrelations (Casanova 1994; Gorski and Altınordu 2008; Stolz 2020). The persistence of individual belief despite institutional decline only appears paradoxical if one does not distinguish levels. A multilevel framework reveals these as empirically possible patterns, much as loose coupling theory (Meyer and Rowan 1977) showed how formal structures can become decoupled from actual practices.

Approaches emphasizing religious disaffiliation from organizations and lived religion similarly make implicit multilevel arguments. The argument that it is primarily organized religion that is on the decline (Bellah et al. 1985; Davie 2015; Hout and Fischer 2002, 2014; Luckmann 1967; Roof 1993; Taylor 2007) is fundamentally about changing relationships between levels. It argues that individual religious commitment persists or transforms even as institutional participation declines and interactional religion moves outside formal organizational contexts. Lived religion perspectives distinguish individual practices, interactional communities, and institutional structures while examining their interplay (Ammerman 2007, 2021; McGuire 2008; Orsi 1985), drawing on practice theory’s insights about how people navigate between institutional schemas and everyday action (Bourdieu 1977; de Certeau 1984).

Making multilevel thinking explicit rather than keeping it implicit offers several advantages. First, it aids precision in theoretical debates and helps identify sources of apparent disagreement. Some controversies stem from scholars focusing on different levels. Does religion decline with modernization? The answer depends on which level one examines and in what ways—institutional religion may decline while individual spirituality is more persistent or, depending on how it is measured, even on the rise. Explicitly naming levels helps identify where scholars actually disagree versus where they are examining different phenomena. This parallels broader recognition that many seemingly intractable debates reflect unacknowledged differences in levels of analysis (Abbott 2001).

Second, explicit frameworks facilitate research design and interpretation by providing conceptual scaffolding. They guide decisions about what to measure, how to operationalize constructs, and how to interpret findings. A multilevel framework reminds researchers that measuring individual belief, however thoroughly, does not tell us about institutional power or interactional dynamics. It encourages thinking about relationships across levels. This addresses persistent challenges about linking individual-level data to institutional patterns, what Hedström and Swedberg (1998) frame as specifying “social mechanisms” that connect different levels.

Third, explicitness serves pedagogy by providing cognitive scaffolding for understanding complex phenomena. When teaching about religion, instructors inevitably navigate its multiple dimensions. But without an explicit framework, this often remains intuitive and sometimes less systematic. An explicit multilevel framework provides a roadmap, helping students see religion’s complexity while organizing their understanding.

Fourth, explicit frameworks enable cumulative knowledge building by facilitating dialog across studies. When studies implicitly invoke different levels without naming them, comparing findings or synthesizing insights becomes difficult. Making levels explicit helps see both what is known and what still needs to be learned. It could, among other things, help bridge the quantitative survey research that tends to focus on individual religiosity with qualitative work that examines people interacting within community.

Fifth, systematic multilevel analysis helps avoid category errors and misplaced reductionism. It prevents treating phenomena at one level as equivalent to patterns at another level—institutional decline is not the same as individual secularization, organizational bureaucratization is not identical to personal religious commitment, interactional religious community can exist outside institutional contexts. This connects to broader concerns about “levels of analysis” problems and the classic ecological fallacy (Robinson 1950; Schnabel 2021).

3. The 3I Framework

Religion operates simultaneously at three analytically distinct yet empirically interrelated levels. At the individual level, religion encompasses personal faith, private practices, beliefs, and one’s sense of connection to the sacred. This includes personal beliefs about the sacred, divine, or transcendent; private religious and spiritual practices such as prayer alone, meditation, contemplation, and personal study; individual religious experiences like feelings of connection, transcendence, and meaning; one’s religious or spiritual identity; personal meaning-making through religious frameworks; and subjective importance of religion in one’s life.

Individual religion can exist independently of participation in religious organizations. Someone can hold deep personal faith without ever attending services or affiliating with institutions. Conversely, institutional involvement does not guarantee individual belief—one can attend services for social reasons while personally nonbelieving (Bengtson et al. 2013; Voas 2009).

Importantly, individual religion is not synonymous with internal belief and external behavior. Both individual beliefs and individual behaviors, as well as individual identity, exist at this level. What defines the individual level is not the type of phenomenon but its location in individual consciousness and action rather than emerging from interaction or institutional organization. To use prayer as an example again, private prayer is individual-level behavior; communal prayer during worship is interactional; prayer requirements mandated by organizations are institutional. The same practice manifests at different levels depending on its form. And the levels can interrelate such that prayer required by organized religion could happen individually or in interaction with others.

The individual level is where most survey research on religion has traditionally focused. Questions about belief in God, frequency of personal prayer, importance of religion in one’s life, and strength of religious identity all measure individual-level phenomena (Smith and Denton 2005; Stark and Glock 1968). This multidimensional approach to individual religiosity has generated valuable insights. But it is part of a larger whole. Understanding religion requires attending to the other levels as well—to how religion is accomplished through interaction and organized through institutions.

At the interactional level, religion is something people do together—shared practices, communal experiences, and the mutual construction and enforcement of religious meaning and identity. This encompasses shared religious practices and rituals; communal worship and the collective effervescence it generates (Collins 2004; Durkheim [1912] 1995); religious conversations and storytelling; social support through religious communities; mutual affirmation and sanctioning of religious identities; informal religious networks; and religious socialization within families and peer groups.

Interactional religion exists in face-to-face encounters whether in formal settings like worship services or informal contexts like prayer groups and spiritual discussions. It is about how people “do” religion together, paralleling how people “do” gender (West and Zimmerman 1987). The interactional level involves how religious identity and practice are performed, evaluated, reinforced, or challenged through social interaction. This draws on insights from symbolic interactionism (Blumer 1969; Goffman 1959; Mead 1934) about how meaning emerges through interaction, as well as ethnomethodological perspectives (Garfinkel 1967) on how social order is accomplished through everyday practices.

This level has received less systematic theoretical attention yet it is essential for understanding how religion actually works. Drawing on interaction ritual theory (Collins 2004), the interactional level emphasizes that religious commitment is actively maintained, negotiated, and transformed through interaction. People learn to be religious through interaction with others—religious socialization is fundamentally interactional. They have their religious identities affirmed or questioned through others’ responses—identity is accomplished through recognition. They experience religion’s emotional power through collective ritual—what Durkheim ([1912] 1995) identified as collective effervescence. Successful interaction rituals generate emotional energy that individuals carry forward. This emotional energy is not reducible to individual psychology; it emerges from the interaction itself.

The interactional level is where “lived religion” often manifests—in actual practices and relationships through which people experience religion in everyday life (Ammerman 2007, 2021; McGuire 2008; Orsi 1985). It is also where “doing religion” parallels “doing gender”—religion becomes real and consequential through how it is performed and recognized in social interaction (Avishai 2008). Someone might hold individual beliefs, but how those beliefs are expressed and responded to in interaction shapes whether and how they matter socially. This connects to practice theory’s emphasis on how meaning is constituted through embodied practice (Bourdieu 1977; Schatzki et al. 2001).

Critically, interactional religion need not occur within institutional contexts. Friends can have spiritual discussions, families can develop their own practices, informal groups can gather—all outside formal organizational auspices. The rise of alternative spirituality and informal religious networks suggests that interactional religion can flourish even as institutional participation declines (Heelas and Woodhead 2005; Watts 2022). This represents transformation rather than disappearance of the interactional level.

At the institutional level, religion exists in organized structures that persist beyond particular individuals and interactions. This encompasses religious organizations such as denominations and congregations; organizational hierarchies and authority structures; formalized doctrines and systematic teachings; religious laws and normative expectations; institutionalized rituals and standardized practices; religious professionals including clergy; physical infrastructure like temples, mosques, synagogues, churches as well as seminaries and other religious schools; and broader cultural norms shaped by and shaping religion.

The institutional level is where religion achieves the most explicit social organization—denominations with membership rosters, congregations with budgets, hierarchies with clear authority, systematic theologies, professionalized clergy (Chaves 1994; Finke and Stark 2005). This connects to insights about rationalization and bureaucratization (Weber [1922] 1978) and how institutions create taken-for-granted structures that shape action (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Meyer and Rowan 1977).

The institutional level extends beyond particular organizations to include broader cultural patterns, it is the level that encompasses both the organizational and the society in Dobbelaere’s framework. Religion as an institution encompasses not just specific churches and denominations but also publicly shared sacred narratives, symbols, and rituals that structure collective moral life—what Bellah (1967) described as American “civil religion”—as well as “religion” as a differentiated social institution distinct from family, economy, or state (Casanova 1994). This is where power operates most visibly—hierarchies determine who has authority, who gets ordained, what counts as orthodox belief (Bourdieu 1991). Organizational structures include or exclude particular groups. Institutional power can constrain both interaction and individual practice.

Importantly, the institutional level includes diverse organizational forms as illustrated by different types of Christian traditions in the United States. Both high-church Catholicism with its elaborate hierarchy, centralized authority, and formal liturgy, and low-church Baptist congregations with minimal bureaucracy, congregational autonomy, and informal worship are institutional forms—they simply represent different modes of institutional organization (Chaves 1994). High-church traditions emphasize mediated access to the sacred through clergy, hierarchical authority, and standardized ritual. Low-church traditions emphasize more immediate relationships with the divine, congregational governance, and flexible worship. But both involve organized religion with structured roles, formalized membership, regular gatherings, and collective identity.

House churches, nondenominational congregations, and Pentecostal movements are still institutional religion insofar as they involve organized groups with roles, norms, and leadership structures. What varies is the degree and type of institutionalization, not whether institutionalization exists. Even seemingly “anti-institutional” movements often engage in institutionalization, creating routinized patterns and shared expectations.

A shift from Episcopal to Baptist congregations, or from denominational to nondenominational Christianity, represents change in institutional forms that could be indicative of deinstitutionalization but are not necessarily a shunning of all bureaucracy. The move from high-church to low-church traditions involves shifts from hierarchical to congregational polities, from mediated to immediate relationships with the divine, from formal to informal leadership, from liturgical to spontaneous worship—but all remain forms of organized, institutional religion. They represent what organizational theorists call different “organizing logics” (Thornton et al. 2012) or what Weber termed different types of authority, but they are all institutions though with arguably different levels of institutionalization.

Even when people exit organizations altogether—no affiliation, no congregation, no participation in formal religious organizations—they may be shaped by religious institutions through prior socialization, institutional legacies, or ongoing cultural influence, even as they are no longer actively participating. And individuals who exit institutional religion may maintain robust individual faith and create new interactional religious communities outside organizational contexts. Even secularists live in societies and surrounded by people where the institutional level of religion continues to affect their lives.

The levels, summarized in Table 1, are analytically distinct but empirically interconnected. They are nested and mutually constitutive—individual religious identities develop through socialization in interactional contexts shaped by institutional structures; interactional religious communities exist within institutional contexts that provide resources, frameworks, and constraints; institutions are built and maintained through individual commitment and interactional processes (Berger and Luckmann 1966; Pearce and Denton 2011). Change or stability at any level both shapes and is shaped by the other levels. This connects to the idea in structuration theory about how structure and agency mutually constitute each other.

Table 1.

Three Levels of Religion.

Yet despite this mutual constitution, levels can change at different rates and even in opposite directions. Institutional participation can decline while individual belief persists. New interactional forms can emerge outside traditional institutional contexts. Individual disengagement from organized religion can coincide with increased personal spiritual seeking. These apparently contradictory patterns reflect the analytical distinctness of levels—they are not contradictions but different aspects of change. This connects to “loose coupling” (Weick 1976), where different parts of social systems can vary independently because connections between them are loose rather than tight.

Relationships between levels are contingent and contextual. In some contexts, strong institutional religion fosters robust individual faith and vibrant interactional communities. In others, institutional rigidity provokes individual exit and alternative interactional spaces (Casanova 1994; D. Martin 1978). Arguments have been made that state churches breed secularism. Individuals navigate relationships between levels in diverse ways. Some maintain alignment across levels. Others experience dissonance—individually religious but institutionally unaffiliated, or institutionally involved but personally nonbelieving. Still others create new combinations—exiting institutional religion while maintaining individual faith and forming new interactional communities (Ammerman 2021). Individual agency in navigating levels means that aggregate patterns reflect diverse individual trajectories. This connects to practice theory’s emphasis on how individuals navigate between institutional schemas and situated action, with creative improvisation possible within structural constraints (Sewell 1992).

Power operates differently at each level. Institutional power is most visible—hierarchical authority, control over resources, cultural legitimacy (Bourdieu 1991). Interactional power works through inclusion, exclusion, and enforcement of norms in face-to-face contexts—who gets to participate, whose religious performances are validated (Collins 2004). Individual power involves the capacity to maintain religious commitment, exit institutions, or construct alternative spiritual frameworks (Hirschman 1970).

Cross-level power dynamics are complex. Institutions constrain individual practice by defining what counts as legitimate religion, by monopolizing sacred resources, by socializing individuals into particular frameworks. Yet individuals resist institutional authority by reinterpreting doctrines, by exiting when demands conflict with values, by forming alternative communities. Interactional communities can challenge institutional hierarchies by creating alternative spaces of meaning-making, or reproduce those hierarchies by enforcing institutional norms at the local level.

Without attending to multiple levels and their relationships, one misses both the complexity of religious phenomena and the dynamics of religious change. One might mistake decline at one level for comprehensive secularization, conflate change in institutional forms with a decline in institutions, interpret new interactional forms as mere individualism, or overlook how institutional power persists despite apparent liberalization.

4. Applying the Framework to Religious Change in the United States

Contemporary debates about American religion often frame the question as binary: Is religion falling or rising? Secularization-oriented scholars point to dramatic institutional indicators—religious “nones” rising from one in twenty to more than one in four, declining attendance, weakening denominational loyalty, plummeting confidence in organized religion (Hout and Fischer 2002, 2014; Putnam and Campbell 2010; Sherkat 2014). Critics counter by highlighting persistent individual belief, continued personal prayer practices, and emerging alternative forms of spiritual expression (Ammerman 2013; Bellah et al. 1985; Roof 1993; Watts 2022). A multilevel framework reveals these are not contradictory but complementary observations about different levels of religious change.

Understanding contemporary religious change requires recognizing that the relationship between individual faith, interactional religious practice, and institutional organization has varied dramatically across history and context. A multilevel framework helps us see that what we now take as the natural form of religion—systematized, institutionalized, organizationally bounded—is actually a relatively recent development, and that current transformations may represent shifts in relationships between levels rather than simple linear or unidirectional change.

The conception of religion as a distinct, systematized institution separate from local culture is a fairly modern—and mostly Western—invention (Asad 1993; Fitzgerald 2007; Nongbri 2013; W. C. Smith 1963). In a multilevel framework, this represents a particular configuration where the institutional level became increasingly elaborated, differentiated, and dominant. But this configuration is neither universal nor inevitable. Outside developments in the Abrahamic world, individual and interactional dimensions of religion remained more tightly integrated with broader cultural life rather than organized into separate institutional structures. Traditions were fluid, syncretic, and embedded rather than bounded and reified (Masuzawa 2005). These contexts had robust individual faith and interactional religious practice without the highly elaborated institutional level that characterizes modern Western religion.

This matters for measurement and theory. Standard measures focused on individual belonging, behaving, and believing in congregation-based monotheistic contexts assume a particular multilevel configuration—one where institutional structures are highly elaborated and individual religiosity is channeled through institutional affiliation. These measures struggle to capture religion in contexts where the institutional level is less differentiated or where multiple traditions coexist without exclusive organizational boundaries (Finke and Bader 2017; Sun 2013, 2020). The multilevel framework clarifies what’s missing: not religion itself, but a particular form of institutional organization.

Even religions we now see as highly institutionalized were not always so. As W. C. Smith (1963) argued, early Christianity and Islam started as dynamic faith movements—strong at individual and interactional levels but with minimal institutional structure. Zoroaster, Jesus, the Buddha, and others sought to challenge established religion in favor of more dynamic faith. Their movements, at least initially, operated primarily at individual and interactional levels. What happened? Over time, institutions developed around these traditions that challenged prior traditions. Beliefs rationalized, practices routinized, movements became systems, communities became formal organizations (Weber [1905] 1930, [1922] 1978). The institutional level became increasingly elaborated—denominations formed, hierarchies emerged, theologies systematized, clergy professionalized. This institutionalization process reached its zenith in mid-20th century America when institutional religion was highly organized and culturally dominant.

The multilevel framework helps us see that institutionalization can create the conditions for its own undoing. The more elaborated institutional structures become, the more potential for tension with individual autonomy and authentic interactional experience. When institutional structures grow too rigid, too rationalized, too bureaucratic, people may rebel—not against religion itself, but against its institutional form (Schnabel et al. 2025). Even movements to return to pre-institutionalized roots—like the Protestant Reformation—can themselves become institutionalized (Hatch 1989).

The multilevel framework reveals these are not contradictions but predictable dynamics of how different levels relate. High institutionalization can constrain individual authenticity and interactional spontaneity, creating pressure for deinstitutionalization. Low institutionalization can create demand for structure and organization, creating pressure for institutionalization. What looks like simple cycles of rise and decline becomes comprehensible as shifting relationships between levels of a multilevel structure.

The secularization debate has dominated discussions of religious change. Early theorists from Comte to Weber predicted religion’s decline in modernity, with secularization theory forecasting widespread decline in the salience of religion (Berger 1967; Gorski and Altınordu 2008). Yet contradictory evidence emerged—religious radicalization, demographic trends favoring religious populations, religion’s persistent political influence—leading even proponents like Berger (1999) to recant. The debate produced increasingly polarized positions, from claims that modern Europe is more Christian than medieval Europe (Stark and Iannaccone 1994) to declarations of the 21st-century as “God’s century” (Toft et al. 2011).

Trends in the United States have helped fuel the debate. Often seen as a counterexample to the secularization thesis (Finke and Stark 2005), many religious traditions made their way out of the private sphere and onto the public stage by the 1980s in a newly politicized way (Casanova 1994), drawing on longer-standing public sacred symbols and moral narratives that Bellah (1967) described as American civil religion. However, perhaps in response to politicized religion, we now see a rapid rise in Americans with no religious affiliation (Hout and Fischer 2002, 2014), and some now claim the U.S. fits the secularization thesis (Voas and Chaves 2016).

A multilevel framework reveals why both sides of the debate are right but their either-or duality obscures a both-and understanding. Work distinguishing between private and public religion or between religious commitment among people and religious authority in society gets at this distinction (e.g., Dobbelaere 1981). A multilevel lens illuminates how secularization and resurgence could be better conceptualized as deinstitutionalization and a return to individual faith—what I call the individualization of religion. Highlighting how the levels affect each other, just as things happening with organized religion led some to want to leave it and become more individualized in their pursuit of meaning and purpose, that leaving has contributed to fears of religious decline among religious people that prompted religious forms that can make religion as relevant as ever in the public sphere as illustrated by Christian nationalism, the overturning of Roe v. Wade, and challenges to same-sex marriage.

We have seen evidence of a shift away from some types of institutionalized religion in the midst of a global resurgence of more charismatic religion (e.g., Pentecostalism, Sufism, general syncretism often labeled “new age”). In some countries, including the United States, people are distancing themselves from institutionalized religion but not necessarily faith and spirituality (Edgell 2012; Martí and Ganiel 2014), with a rising “spiritual but not religious” ethos playing out. People may be seeking to return to pre-institutionalized faith, such as community congregations and house churches, or they may be exiting institutions altogether and exploring new religious forms, individualized spirituality, or secularism. We could think of this shift as deinstitutionalization or decentralization of religion, the emergence of a “centrifugal force” in American religion (Warner 1993), or, alternatively, individualization (Schnabel et al. 2025). This shift is driven by a variety of factors, including frustrations with the exclusivity and perceived hypocrisy of institutions, broader societal trends toward individualization and autonomy, and a desire for pre-institutionalized faith untainted by organizational accouterments (Bock 2021; Frost and Edgell 2022; Hout and Fischer 2002, 2014).

An excerpt from a phone survey interview in 2015 I supervised while working in the Center for Survey Research at Indiana University illustrates this trend poignantly. The survey was not about religion, but one respondent regularly brought up her beliefs, religious friends, religious community, and pastor irrespective of the topic at hand. She selected the highest option for frequency of religious service attendance. But when asked how religious she is, she identified herself as “not-at-all religious.” Without prompting, she explained her answer by discussing her own religious life, her religious community, and things her pastor said. She explained that some people are too into religion and miss what truly matters, and how her pastor always says they are not following a religion—they are following Jesus. She concluded by offering a phrase she had used repeatedly to explain what truly mattered: her “personal relationship with Jesus.”

These responses and explanations highlight the difference between personal piety and institutional religion. The respondent was personally devout and clearly regularly involved with a religious community but distanced herself from the label of institutionalized religion. This post-institutional distancing from “religion” is occurring among those disaffiliating from organized religion (Hout and Fischer 2002, 2014), but may also be occurring among people who remain quite personally pious and involved in a faith community. Some fundamentalist groups have even tried to reframe around “Jesus plus nothing” to get back to simple faith in Jesus before religious institutions arose (Sharlet 2008).

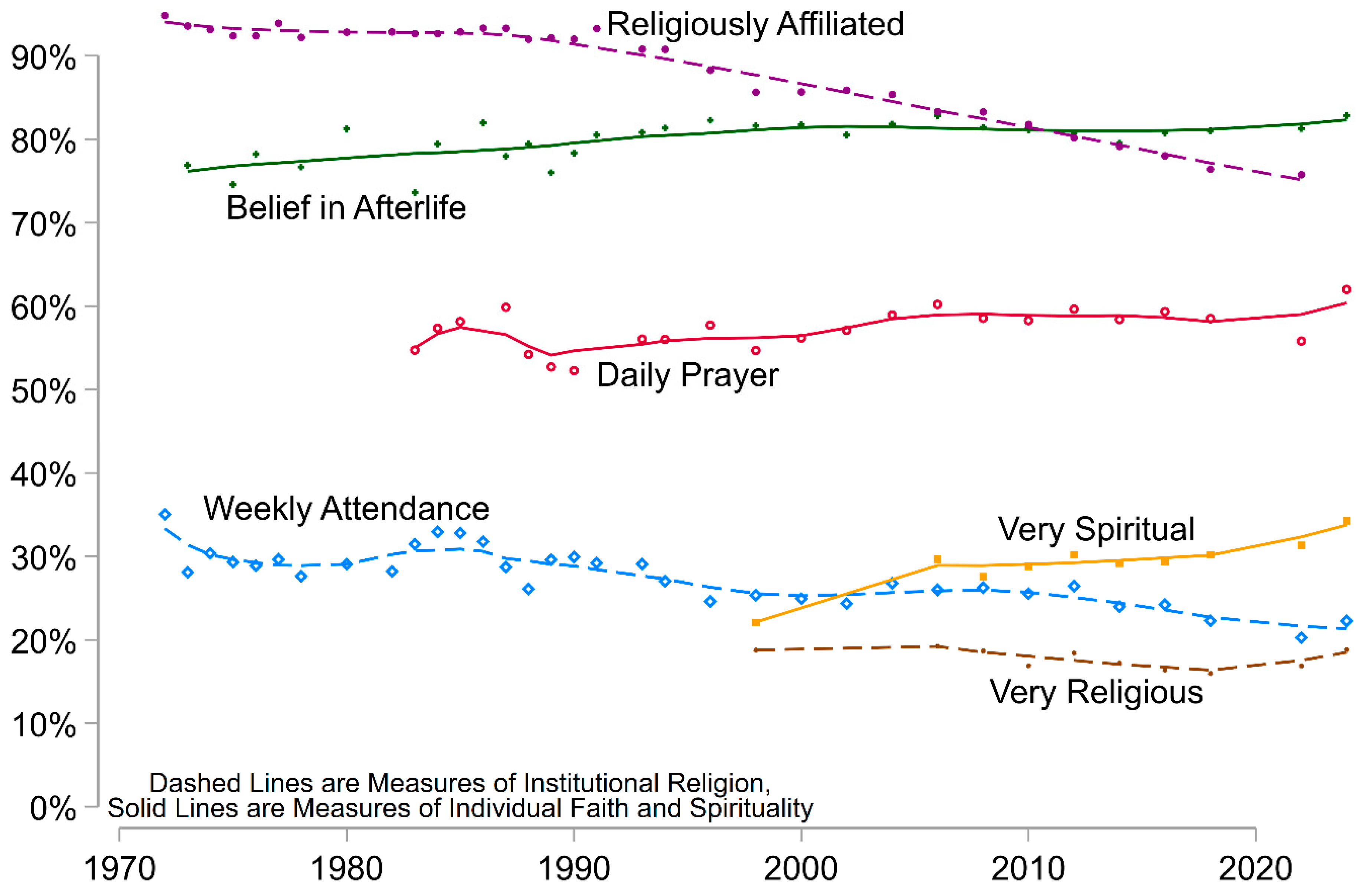

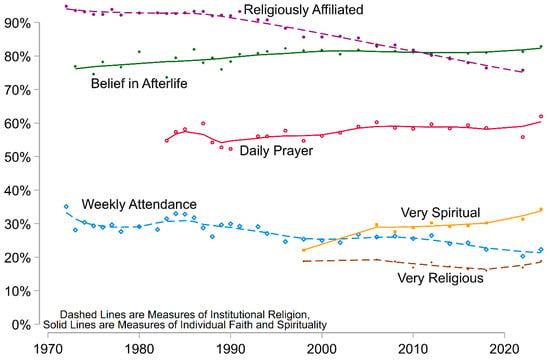

We can put the framework to use by examining and interpreting various measures that tap into either people’s involvement in institutional religion or their individual faith and spirituality. Notably, these are measures asked of individuals and are more “individual” types of measures though they tap into aspects related to more institutional and more individual aspects. Do they move similarly (as might be expected if looking for unidimensional rising or falling of religion) or differently (as expected in a multilevel framework)? General Social Survey data shown in Figure 1 reveal striking differential patterns that would be paradoxical without a multilevel lens but become comprehensible when we distinguish between individual, interactional, and institutional dimensions.

Figure 1.

Institutional Religion vs. Individual Faith and Spirituality over Time. Source: GSS, 1972–2024 (focusing on non-web cases1; N varies by measure availability from 21,363 for spiritual salience to 67,630 for attendance).

Institutional-level indicators show the steepest declines. Religious affiliation dropped from approximately 95% in the early 1970s to around 70%, with particularly sharp declines after 1990. Weekly religious service attendance fell from about a third to about a fifth. The percentage who said they are “very religious” declined though has had a slight uptick post pandemic. Based on these measures alone, one might conclude religion is declining and America is secularizing. But religious life does not occur just once a week or only in connection with organizations—people experience and live out their faith and spirituality in everyday lives in a variety of ways (Ammerman 2021; Orsi 2005).

Individual-level indicators more distinct from organized religion showed more modest change and in some cases even increased. Belief in an afterlife went up from about 75% before leveling off at about 80%. Daily prayer held steady and, depending on where you start, may have increased some. Identifying as “very spiritual” increased over time. Based on these measures alone, one might conclude faith is holding steady if not rising.

The key insight from looking at these patterns from a multilevel perspective: these apparently contradictory patterns are not contradictory at all. They reflect differential change across levels of religion as a social structure. Even in these items measured based on individual responses to surveys we can see a shift from markers of institutional religion while people retain if not increase their involvement in individual faith and spirituality. The secularization debate as it presently exists is in some ways a tug of war between those who say religion is either rising or declining when it ought to be envisioned as a game of chess where different pieces can move in different directions. We need to consider the breadth and magnitude of measures to understand religious change in all its directions and configurations.

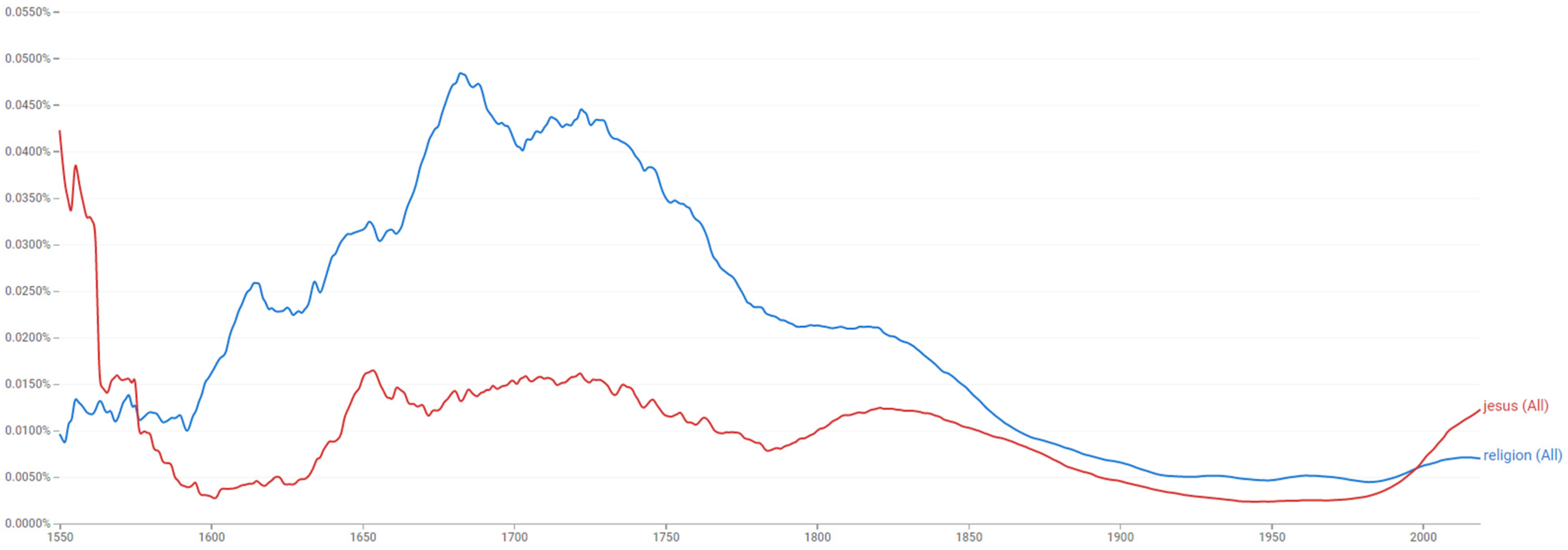

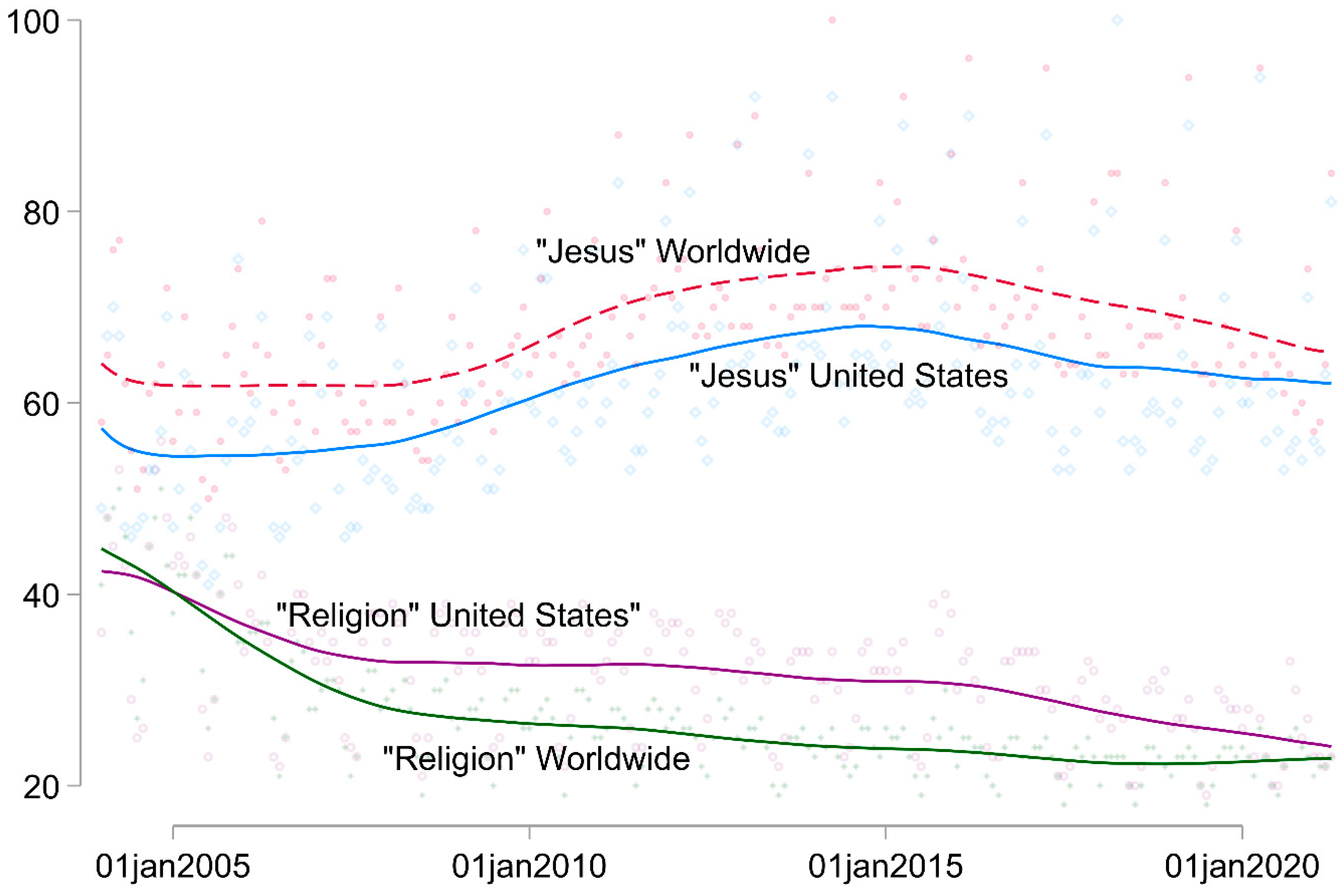

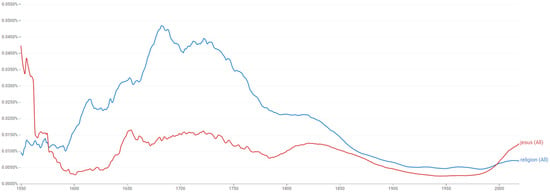

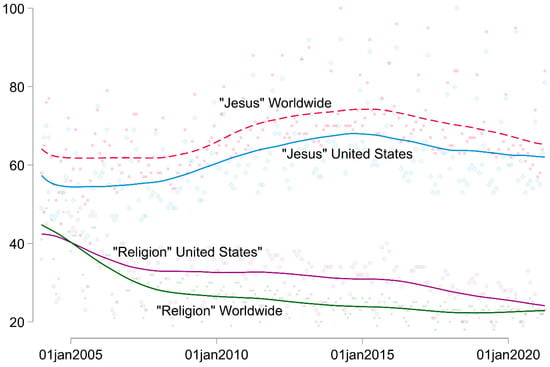

Cultural evidence reinforces these patterns. Google Books data (Figure 2) show a declining presence of the term “religion” in published books over time alongside references to “spirituality” increasing. Google search interest data (Figure 3) similarly reveal shifts from “religion” toward “spirituality” and more personal spiritual terms. This linguistic shift from “religion” to “spirituality” reflects the broader deinstitutionalization of faith—people are distancing themselves from the language and framework of organized religion while maintaining engagement with transcendence and meaning through alternative vocabularies and practices.

Figure 2.

Presence of the Terms “Religion” and “Jesus” in English Language Books Over Time. Source: Google Books Ngram.

Figure 3.

Google Search Interest for the Terms “Religion” and “Jesus” in the United States and Globally Over Time.

Beyond the patterns for markers of more individual faith and institutionalized religion, interactional-level religion and spirituality shows transformation rather than simple decline. While formal worship attendance has declined dramatically, informal spiritual practices have persisted and new interactional forms emerged—informal spiritual gatherings, meditation groups, online religious communities including both more formal communities and also more informal interactions on social media, forums, and elsewhere. Alternative spiritual practices like yoga and meditation increased even as traditional worship has declined (Heelas and Woodhead 2005; Schnabel et al. 2025). Americans have not stop doing “sacred” things with others; they started doing them in different ways and different spaces outside traditional institutional contexts. And sometimes they are done so far removed from religion that they are essentially secular “sacred” practices such as when an atheist goes to a yoga class to be present with their body and connect with their community.

A multilevel framework makes sense of what could otherwise appear paradoxical. The “nones” are rising sharply (institutional disaffiliation), yet most Americans remain spiritual in some way (individual spirituality persists). Religious attendance plummets (institutional participation declines), yet many who leave still pray on their own (individual practices continue). Traditional congregations weaken (institutional erosion), yet new spiritual communities form (interactional religion transforms). These are not contradictions but patterns of multilevel change—what organizational theorists would recognize as loose coupling, where different parts of a system can vary independently. The framework reveals that debates framed as “decline versus resurgence” create false dichotomies. Both are happening, at different levels. Institutional decline does not automatically translate to individual secularization even as they are loosely coupled. Levels can and do change at different rates and some forms could persist or even be resurgent (some types of spirituality, holism, and even extremism) even as others decline (institutional religion and some traditional approaches). Even secular materialists make meaning and purpose and find a sense of wonder in the universe at the same time they would never darken the doors of a church. We could say that is not “religion,” but it would be harder to say there is no sense of the “sacred”—even if the “sacred” centers on concern for the environment or the right for all to pursue happiness, love, and self-actualization.

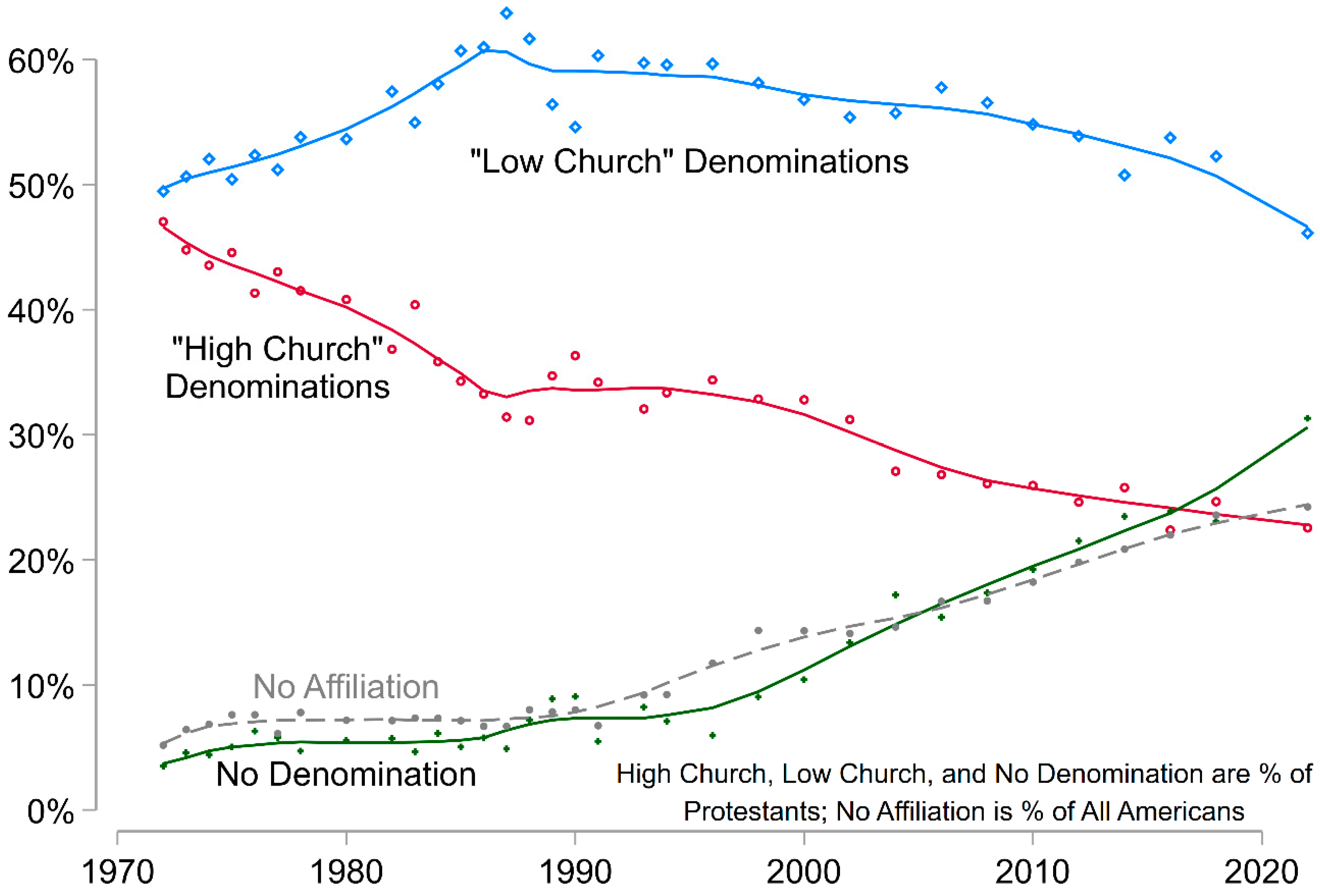

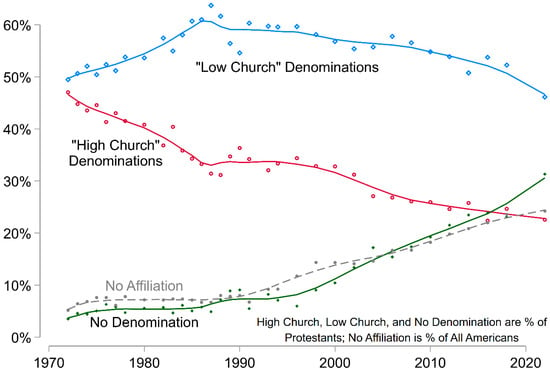

The multilevel framework also clarifies what’s occurring at the institutional level itself. If American religion is deinstitutionalizing—with individual and interactional dimensions persisting or transforming while traditional institutional forms weaken—we should see evidence not just in declining affiliation overall, but in compositional shifts within institutional religion toward less institutionalized forms. Protestant denominations provide a revealing test case.

Protestant denominations differ substantially in their level of institutionalization. Mainline Protestant denominations are typically “high church”—more formal, ritualized, professionalized, communally structured, and institutionalized (e.g., Episcopal, most Methodist and Lutheran). Evangelical denominations are typically “low church”—more informal, emotional, individualized, and less institutionalized (e.g., Baptist, Pentecostal). In high-church denominations, professional clergy act as intermediaries between congregations and God; in low-church congregations, people commune more directly with God. Both are institutional religion—organized groups with roles, norms, leadership—but they represent different degrees and modes of institutionalization and bureaucracy.

If deinstitutionalization is occurring, the multilevel framework predicts compositional shifts within Protestantism away from more institutionalized forms toward less institutionalized forms and toward no denomination at all. The data confirm this prediction. In the early 1970s, high-church and low-church denominations each comprised approximately half of American Protestantism, and non-denominational Christians were negligible (Figure 4). From the 1970s through 1980s, major restructuring occurred—low-church denominations came to dominate while high-church declined. Then around the time religious “nones” started rising rapidly, denominational “nones” within Protestantism also began increasing. Their proportion grew rapidly, drawing largely from high-church at first and to a lesser extent low-church categories. However, in more recent years “no denomination” Christians seem to be pulling from low-church denominations as well. Today, low-church denominations remain the largest Protestant group, but denominational “nones” have grown dramatically and are now higher than the high-church proportion. If current trends continue, “no denomination” may eventually become the largest category.

Figure 4.

Protestant Composition over Time with No Affiliation for Comparison. Source: GSS, 1972–20222 (focusing on non-web cases; N = 38,649 for Protestant composition [limited to Protestants] and N = 65,879 for no affiliation [all Americans with affiliation information]). Note: Protestant composition categories largely follow RELTRAD with the following changes to make the categories “high-church,” “low-church,” and “no denomination” instead of mainline, evangelical, and Black Protestant: historically Black churches sorted into “low-church” and “high-church,” Methodists who do not know their type go with “low-church” (RELTRAD counted as mainline), all “other denomination” get counted as “low-church,” no denomination gets its own category (and people who say “just Christian” instead of Protestant on the RELIG question get included in it as well) instead of being sorted based on attendance frequency.

This reveals an important insight from the multilevel framework: deinstitutionalization is occurring both across American religion generally (the rise of religiously unaffiliated) and within institutional religion itself (the rise in those who are religiously affiliated but reject denominational labels and structures). Both groups share common ground—distancing themselves from bureaucratic, institutionalized forms of religion in pursuit of authenticity and autonomy. The multilevel framework clarifies that these parallel trends are not coincidental but reflect the same underlying process: a broad-based shift away from bureaucratic organized religious forms at the institutional level, while individual faith and interactional communities persist or transform in new ways.

Those without a denomination may be skeptical of institutional labels, seeking to reduce bureaucracy in favor of returning to what they see as faith’s foundations. Those without any religious affiliation have distanced themselves more fully from organized religion but some may still maintain individual spirituality and interactional religious communities. The multilevel framework reveals these as different trajectories through the same structural transformation—deinstitutionalization is creating multiple pathways as people maintain different combinations of individual, interactional, and institutional engagement.

The multilevel framework not only describes these patterns but sheds light on the mechanisms driving them. Several dynamics help explain why the three levels are decoupling—why institutional religion can decline while individual faith persists, why new interactional forms emerge outside traditional structures.

First, value conflicts between institutional stances and individual commitments create pressure for disengagement at the institutional level while maintaining engagement at other levels. When religious institutions are perceived as marginalizing sexual minorities, constraining women, or demonstrating hypocrisy, people—especially those valuing personal autonomy and social justice—experience conflict between institutional religion and deeply held values (Hout and Fischer 2014). This is particularly acute around LGBTQ rights and gender equality. In a recent longitudinal study on religious change, one young man who started out quite religious and got fed up with religion over time put it this way: “I was tired of going to church and hearing about how we cannot let the gays get married… I said, ‘For a church that says they are accepting… you guys are pretty discriminatory… I used to love coming to church, I do not anymore’” (Schnabel et al. 2025, p. 13).

The multilevel framework clarifies what’s happening: institutional religion is rejected for its stances and practices, but individual faith and spirituality need not be abandoned. Someone can exit the Catholic Church while maintaining belief in God and prayer practices. They can leave evangelical congregations while continuing to value spiritual connection. The institutional and individual levels decouple—engagement at one does not require engagement at the other. This is loose coupling at work: different parts of the religious system can vary independently because connections between them are flexible rather than rigid. Certainly, some who leave become secular materialists but there are still far more spiritual people than atheists in the United States.

Second, life course transitions create opportunities for reconstructing relationships between levels. The transition to adulthood involves developing autonomous identity distinct from inherited institutions (Arnett 2000; Pearce and Denton 2011). In earlier eras, institutional scripts structured this transition—young people followed parents into established affiliations, married within their communities, continued established patterns. Contemporary young adulthood is less institutionally structured, requiring individuals to author their own lives. This creates opportunity for religious reconstruction.

Third, and most fundamentally, movement away from institutional religion need not mean abandoning engagement with the sacred. Qualitative research reveals that many who leave organized religion describe not losing faith but finding more personally meaningful ways to engage spiritually (Schnabel et al. 2025). They replace institutionally mediated connection with direct personal experience. They trade formal services for informal gatherings, individual contemplation, or nature-based spirituality. They construct personalized frameworks drawing eclectically from multiple traditions.

As one young woman from the longitudinal study mentioned above described it: “I still really believe like the core beliefs, in God and Jesus… living in a way that pleases God is important. And that to me is—beyond just like following rules—is a way to show that you love God. But also by sharing love, and being a servant to people around you” (Schnabel et al. 2025, p. 17). She exited institutional religion while maintaining robust individual faith and commitments to living religiously. The multilevel framework reveals this is not paradoxical but predictable: individual religion persists or transforms, new interactional forms emerge, but institutional religion faces exit and declining authority. The three levels are decoupling—individual faith need no longer align with institutional affiliation, interactional religious community need no longer occur in institutional contexts. Those who identify as religious and those who identify as spiritual are not one and the same.

One must acknowledge that broader secularization, at least in relation to organized religion, is also occurring for substantial portions of the population. A growing number of Americans report no engagement with religion at any level (Sherkat 2014; Zuckerman et al. 2016). The multilevel framework helps recognize both patterns without treating them as contradictory. Among those remaining religiously engaged, individualization is prominent—maintaining religion at individual and interactional levels while disengaging institutionally. Simultaneously, a growing population disengages at all levels, embracing secular worldviews. Both trajectories are real. Different populations follow different paths, contributing to religious polarization (Hout and Fischer 2014; Schnabel and Bock 2017).

The multilevel framework’s explanatory power lies in revealing that debates framed as “secularization” versus “resurgence” miss the point. Religion is not simply rising or falling—it is transforming through differential change across levels, decoupling, and polarizing. Throughout recorded history we have seen religions move through multiple stages: from pre-institutionalized faith to institutionalized religion and now toward post-institutionalized and individualized faith—what Schnabel et al. (2025) term “breaking free of the iron cage” of institutionalized religion. The multilevel framework helps us understand not just that this is happening, but why: loose coupling between levels means they can change at different rates, creating new configurations of religious engagement that mix persistence at some levels with transformation or decline at others.

5. Conclusions

Religion is not simply what individuals believe, what people do together, or how society organizes transcendence. It is all three simultaneously. Understanding religion requires attending to each level while examining how they operate in relation to one another. Making multilevel thinking explicit strengthens both theory and empirical research. By distinguishing clearly between individual, interactional, and institutional levels, the framework provides analytical scaffolding for conceptualizing religion’s complexity. By showing how these levels relate yet can change independently, it helps explain apparently paradoxical patterns. By offering considerations for measurement and analysis, it improves research design and facilitates cumulative knowledge building.

The framework builds on substantial existing scholarship—from Glock and Stark’s multidimensional approaches to Dobbelaere’s three-level secularization theory to religious market theory’s implicit levels to lived religion’s attention to multiple contexts. The multilevel theory of gender provides a powerful parallel. The 3I framework synthesizes these insights into a (hopefully) coherent, systematic approach that connects the sociology of religion to broader sociological theory about structure and agency, micro and macro, how social phenomena exist simultaneously across multiple levels that mutually constitute each other while remaining analytically distinct.

Illustration through contemporary American religious change demonstrates the framework’s utility. What appears contradictory through a single-level lens—institutional decline alongside spiritual persistence, disaffiliation and continued belief, organizational exit and sacred engagement—becomes comprehensible as multilevel transformation involving loose coupling between levels. Institutional religion faces dramatic challenges. Individual religion shows complex patterns of persistence, decline, and innovation. Interactional religion is shifting from traditional congregational forms to alternative spiritual communities. These levels are decoupling through loose coupling, creating new religious landscapes.

Several limitations point toward needed work. This study relied on the same type of survey data from individuals used in much past work. I am working on research for a book project that makes use of this perspective in data collection and analysis, but this theoretical paper used secondary data with the typical measures and simply conceptualized them a little differently and used the framework to interpret the patterns. Collecting data coming from multiple levels would be useful, but would require careful planning and multiple interrelated data collection efforts to examine the individual, interaction, and institutional levels and how they interrelate with one another on a given research question simultaneously. While the framework can have broad application, here it has been applied to American religion and religious change, highlighting the need for further application on more contexts and topics. Further application will reveal both limits and possibilities for refinement.

Despite limitations, it is my hope that the framework provides valuable analytical scaffolding. It makes explicit what often remains implicit, offers definitions, and generates testable propositions about religion as multilevel structure. More broadly, it contributes to conversations about religion’s role in contemporary society by clarifying what’s actually being debated. Claims about religious decline may be true at one level while not forming the full picture at another. Making levels explicit may facilitate more productive dialog on some questions and debates. The framework also speaks to broader sociological questions about relationships between individuals, interactions, and institutions—religion provides a rich case for examining how these levels mutually constitute each other while remaining distinct.

This framework is offered as a small contribution to ongoing conversation rather than a final answer. It aims to make implicit multilevel thinking explicit, to provide analytical tools that scholars can use and improve, and to demonstrate through application how such thinking generates insight. The framework will succeed if it provokes discussion, debate, and refinement leading to more sophisticated understandings of religion in all its complexity. As societies transform and religion evolves, this multilevel perspective can help track shifts—not by reducing religion to any single dimension, but by attending to its full complexity as a genuinely multilevel social structure that exists simultaneously in individual consciousness, in face-to-face interaction, and in organized institutions that shape and are shaped by one another.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study used publicly available secondary data.

Informed Consent Statement

The study used publicly available secondary data.

Data Availability Statement

General Social Survey data are publicly available from the General Social Survey website (https://gss.norc.org/get-the-data.html, accessed on 1 December 2025) and the Google ngrams (https://books.google.com/ngrams/, accessed on 1 December 2025) and trends in search data (https://trends.google.com/trends/, accessed on 1 December 2025) publicly available from Google.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | A methodological note: for the figures using GSS data, the results focus on cases not fielded over the web. The General Social Survey has traditionally relied on in-person interviews with some conducted over the phone and had high response rates. The 2020 GSS was delayed until 2021 and fielding focused on the web, with some surveys conducted over the phone. It had a drastically reduced response rate and I excluded this year completely (see Schnabel et al. 2024). In 2022, the GSS started to focus on both in-person and web, with some interviews conducted over the phone. Research shows a bias in the responses collected over the internet, resulting largely from certain people (including highly religious people) being less likely to agree to take the survey over the internet (Schnabel et al. 2024). In line with that research and at the suggestion of Jeremy Freese, one of the PIs of the General Social Survey who said that when looking at over time patterns you may want to focus on the same methods, I have opted to focus on responses not completed over the internet. |

| 2 | The denomination data only goes through 2022 as the 2024 GSS data release available as of July 2025 does not yet include this information; the GSS codebook says the variable is “not included in Release 1 but are expected in future releases.” |

References

- Abbott, Andrew. 2001. Time Matters: On Theory and Method. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Jeffrey C., Bernhard Giesen, Richard Münch, and Neil J. Smelser, eds. 1987. The Micro-Macro Link. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2007. Everyday Religion: Observing Modern Religious Lives. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2013. Spiritual But Not Religious? Beyond Binary Choices in the Study of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 258–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2021. Rethinking Religion: Toward a Practice Approach. American Journal of Sociology 126: 6–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2000. Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens through the Twenties. American Psychologist 55: 469–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, Talal. 1993. Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Avishai, Orit. 2008. ‘Doing Religion’ in a Secular World: Women in Conservative Religions and the Question of Agency. Gender & Society 22: 409–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, Robert N. 1967. Civil Religion in America. Daedalus 96: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, Robert N., Richard Madsen, William M. Sullivan, Ann Swidler, and Steven M. Tipton. 1985. Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson, Vern L., Norella M. Putney, and Susan Harris. 2013. Families and Faith: How Religion is Passed Down across Generations. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L. 1967. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. Garden City: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L. 1999. The Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religion and World Politics. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L., and Thomas Luckmann. 1966. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Garden City: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, Herbert. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, Sean. 2021. Conflicted Religionists: Ambivalence and Distancing among American Christians. Socius 7: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Genesis and Structure of the Religious Field. Comparative Social Research 13: 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2002. God Is Dead: Secularization in the West. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Cadge, Wendy, and Mary Ellen Konieczny. 2014. ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’: The Significance of Religion and Spirituality in Secular Organizations. Sociology of Religion 75: 551–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, José. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 2007. Rethinking Secularization: A Global Comparative Perspective. In Religion, Globalization, and Culture. Edited by Peter Beyer and Lori Beaman. Leiden: Brill, pp. 101–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, Mark. 1994. Secularization as Declining Religious Authority. Social Forces 72: 749–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, Richard R., and James W. Gladden. 1974. The Five Dimensions of Religiosity: Toward Demythologizing a Sacred Artifact. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 13: 135–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, James S. 1990. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Randall. 2004. Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, Marie, Stan L. Albrecht, Perry H. Cunningham, and Brian L. Pitcher. 1986. The Dimensions of Religiosity: A Conceptual Model with an Empirical Test. Review of Religious Research 27: 226–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, Grace. 2015. Religion in Britain: A Persistent Paradox, 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, Paul J., and Walter W. Powell. 1983. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review 48: 147–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbelaere, Karel. 1981. Secularization: A Multi-Dimensional Concept. Current Sociology 29: 1–153. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbelaere, Karel. 2002. Secularization: An Analysis at Three Levels. Brussels: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1982. The Rules of Sociological Method. Translated by W. D. Halls. New York: Free Press. First published 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1995. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Translated by Karen E. Fields. New York: Free Press. First published 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Edgell, Penny. 2012. A Cultural Sociology of Religion: New Directions. Annual Review of Sociology 38: 247–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, Roger, and Christopher Bader. 2017. Faithful Measures: New Methods in the Measurement of Religion. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finke, Roger, and Rodney Stark. 2005. The Churching of America, 1776–2005: Winners and Losers in Our Religious Economy. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, Timothy. 2007. Discourse on Civility and Barbarity: A Critical History of Religion and Related Categories. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Jacqui, and Penny Edgell. 2022. ‘I Believe in Taking Care of People’: Care-Centered Narratives among the Religiously Unaffiliated. Poetics 90: 101596. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, Harold. 1967. Studies in Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glock, Charles Y. 1962. On the Study of Religious Commitment. Religious Education 57: S98–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, Charles Y., and Rodney Stark. 1965. Religion and Society in Tension. Chicago: Rand McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, Philip S., and Ateş Altınordu. 2008. After Secularization? Annual Review of Sociology 34: 55–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, Neil. 2009. A Pragmatist Theory of Social Mechanisms. American Sociological Review 74: 358–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, Nathan O. 1989. The Democratization of American Christianity. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hedström, Peter, and Richard Swedberg, eds. 1998. Social Mechanisms: An Analytical Approach to Social Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heelas, Paul, and Linda Woodhead. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion Is Giving Way to Spirituality. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Peter C., and Ralph W. Hood, Jr., eds. 1999. Measures of Religiosity. Birmingham: Religious Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman, Albert O. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hout, Michael, and Claude S. Fischer. 2002. Why More Americans Have No Religious Preference: Politics and Generations. American Sociological Review 67: 165–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]