Abstract

This study focuses on Quanti Xinlun (1851), translated and compiled by the Protestant missionary Benjamin Hobson in the late Qing dynasty, examining how the Western anatomical knowledge it introduced challenged and reshaped the traditional Chinese conception of the body grounded in Visceral Manifestation theory. The research finds that the book’s influence was achieved through multiple mechanisms, including conceptual innovation, visual representation, and the creation of terminology. Although Hobson’s original motivation for translation was rooted in Natural Theology, its scientific core was selectively appropriated by the late Qing intellectual community, becoming a tool to address indigenous academic and ideological predicaments. This study argues that Quanti Xinlun facilitated a significant paradigm shift: on the level of the conception of the body, it used the physical body to challenge the traditional perception of a functional, qi-based organism; on the epistemological level, it invoked the authority of empirical positivism to challenge the scholarly method of text-based classicism. This fundamental shift in epistemology not only spurred the medical trend of thought known as “Convergence of Chinese and Western Medicine” but also laid the cornerstone for the modernization of modern Chinese medical education and even the entire knowledge system.

1. Introduction

The late Qing dynasty witnessed intense transformative pressures on China’s traditional knowledge and ideological systems. In this context, missionaries arriving in China adopted an indirect approach to more effectively propagate their faith. They systematically introduced Western scientific and medical knowledge, aiming to attract Chinese interest and alter prevailing mindsets, thereby laying the groundwork for the acceptance of Christianity. This evangelism, mediated through knowledge dissemination, objectively cast missionaries in the role of modern intellectual enlighteners. Academia has widely recognized the contributions of missionaries to knowledge transmission, whether in modern education (Li and Xiao 2018), the translation of legal terminology (Qu 2014), ideological fields such as philosophy and evolutionary theory (Lu et al. 2023), or natural sciences such as biology (Sun and Ma 2023). Translation plays an important role in the process of knowledge dissemination. Translation, as a product of history, is constrained by history while simultaneously reacting upon it (M. Lu 2012, p. 243). Therefore, situating missionary translation activities within their specific historical context facilitates a deeper understanding of their practical impact on Chinese society.

Among the various branches of Western learning introduced by missionaries, their contributions to medicine are particularly noteworthy. Scholars have conducted in-depth research on missionaries’ roles in practical and institutional spheres, such as the establishment of modern medical education (X. Sun 2008), the founding of missionary hospitals (Chen and Chen 2022), the development of professional nursing ethics (Chou and Wang 2024), and opium addiction treatment (Zheng 2025), as well as in textual and linguistic work, like the translation and publication of medical books (Chen and Zhang 1997; Tu 2023; Y. Song 2020) and the standardization of medical terminology (Gao 2008; C. Li 2005; D. Zhang 1994). Beyond merely introducing Western medicine, they also actively observed and documented local medical practices, as seen in the records of Traditional Chinese Medicine within The China Medical Missionary Journal (Li and Yan 2025).

In the process of introducing Western medicine, Benjamin Hobson, one of the earliest missionaries to systematically translate Western medical knowledge in the late Qing period, became a focal point of research. Hobson’s work not only influenced China but also resonated widely across East Asia, particularly in Japan (Bosmia et al. 2014; van der Weiden and Mori 2014). In previous studies, Z. Sun (2010), focusing on Yixue Yinghua Zishi 醫學英華字釋 (A Medical Vocabulary in English and Chinese), explored Hobson’s contributions to establishing modern Chinese medical terminology; Su (2020) meticulously examined Hobson’s biography and the translation and publication history of his representative work, Quanti Xinlun 全體新論 (Treatise on Physiology). Furthermore, studies by Zhao (1991) and Chan et al. (2013) discussed the influence of Hobson’s Western medical works on modern Chinese medicine and revealed his underlying strategy of competing for cultural discourse by demonstrating the superiority of Western medicine.

Recently, Wong (2024), using Hobson as a case study, provided a profound analysis of how Hobson subordinated medicine to his ultimate evangelistic purpose when dealing with the relationship between Chinese and Western medicine. However, while Wong’s (2024) research deeply reveals Hobson’s motivations and strategies in using medicine to serve evangelism, there remains room for further exploration. Building upon this, the present study will, first, narrow the focus from the broad field of “medicine” to its foundational discipline, “anatomy”. Second, this study will shift the analytical emphasis. While acknowledging his missionary motives, it will pay greater attention to the process, methods, and effects of translating and disseminating anatomical knowledge as an independent intellectual system. Consequently, this paper aims, through an in-depth analysis of the textual and visual language in Hobson’s anatomical translations, to reveal how his pioneering work laid a crucial epistemological foundation for the modern transformation of Chinese medicine. Specifically, this paper argues that Hobson played a pivotal role not merely as a translator, but as a promoter of a new cognitive perspective. Through the Quanti Xinlun, Hobson introduced a Western structural anatomical body that differed from the functional, qi-based body of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM); furthermore, the dissemination of this work prompted late Qing intellectuals to acknowledge a standard of truth based on visual evidence rather than canonical authority.

Therefore, from the aforementioned research perspective, this paper will first outline the paradigm of the functional and relational conception of the body within the TCM tradition. Building on this foundation, the paper will focus on Hobson’s anatomical translations, conducting a thorough analysis of his translation strategies, use of images, and contributions to terminology creation. It will specifically interpret how this new knowledge system challenged and reshaped the traditional framework of bodily cognition. Finally, this paper will argue how Hobson’s translation practice, as a socio-cultural phenomenon, functioned within the modern transformation of Chinese medicine, thereby affirming its positive contribution to the modernization process of China’s knowledge system.

2. The TCM View of the Human Body Before the Introduction of Western Medicine: A Functional and Qi-Based Anatomy

The conceptual foundations upon which TCM and modern Western Biomedicine rest diverge profoundly. Western medicine, rooted in the philosophy of mechanism, conceives of the human body as an intricate machine and prizes anatomical dissection as the principal path to truth. In stark contrast, the TCM worldview is characterized by a dynamic, process-oriented understanding of life, often termed “qihua guocheng” 氣化過程 (qi-transformation process). This entire philosophical divergence is well-articulated by Marié (2011, p. 11). The divergence lies between the Western mechanical view and the Chinese principle of not denying the “structural reality of the body” but refusing to accord it determining influence. Marié succinctly notes that in TCM, a right knowledge of the living cannot be deduced from observations made on dead bodies. Building upon this foundation, this chapter posits that the pre-modern TCM view of the body constituted a unique dual-composite system. It encompassed not only a “xingti jiepou xue” 形體解剖學 (physical anatomy) derived from direct observation but was fundamentally predicated upon a theoretical framework of “zangxiang jiepou xue” 藏象解剖學 (visceral manifestation anatomy), centered on life activities and the correspondence between humanity and the cosmos.

TCM’s exploration of human morphology was not a blank slate; its anatomical activities can be traced back to the pre-Qin and Han dynasties. According to the Hanshu: Wang Mang Zhuan 漢書·王莽傳 (Book of Han: Biography of Wang Mang), imperial physicians collaborated with butchers to perform human dissections, measuring the five organs and using bamboo tubes to trace the paths of the blood vessels, in order to understand the structure of the viscera and vessels to aid treatment (Ban 1962, p. 4145). The Huangdi Neijing 黃帝內經 (The Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic), compiled from the Warring States period to the Western Han, summarized the anatomical achievements of its time, detailing the lengths, weights, and capacities of human bones, organs, and blood vessels. Most of these anatomical names, such as those for bones and the five major organs, are still in use today. Shaw et al. (2022, p. 1213) have “demonstrated that the 300–200 BCE Mawangdui medical texts represent the oldest surviving anatomical atlas in the world, predating Galen by about a thousand years”. This shows that as early as the Han dynasty, China had already carried out anatomical practices and illustrated them in atlases. Thereafter, through the Wei, Jin, Sui, Tang, and into the Song and Yuan dynasties, TCM anatomy reached its zenith. Among these developments, the creation of the Song dynasty’s Ouxifan Wuzang Tu 歐希范五臟圖 (Ou Xifan’s Anatomical Illustrations) and Cunzhen Tu 存真圖 (Anatomical Atlas of Truth) was particularly outstanding. The latter, as an imperially commissioned anatomical atlas, systematically depicted visceral morphology and meridian distribution, and corrected errors of previous generations (such as correctly pointing out that the larynx and pharynx are two distinct passages, not three). It served as the blueprint for later visceral atlases for over seven hundred years (Jin and Jin 1996, p. 280). However, in the period following the Song dynasty and prior to the introduction of Western anatomy in the late Ming and early Qing, the development of TCM’s physical anatomy based on direct observation saw no significant advancement.

Nevertheless, physical anatomy was not the endpoint of TCM’s cognition of the human body, but rather the starting point. The ancient sages of TCM clearly recognized that the static structure of a dead body could not fully explain the complex dynamic processes of a living body. Therefore, upon the foundation of physical anatomy, they developed a more profound and central theoretical framework: “Zangxiang” 藏象 (visceral manifestations) theory. This system proceeds from the living, animate person. Its theoretical core shifts from physical organ entities to the functional relationships expressed through concepts like “tianren heyi” 天人合一 (unity of heaven and man), “yinyang wuxing” 陰陽五行 (“Yin-Yang” and the Five Phases), and the cyclical laws of day, night, and the four seasons. Through methods such as “siwai chuainei” 司外揣內 (deducing the interior from the exterior) and “quxiang bilei” 取象比類 (analogical reasoning), it established a functional model system centered on the “wuzang” 五臟 (five zang-organs): Lung, Heart, Spleen, Liver, and Kidney. In other words, the human organism is understood as a composite of physical body and visceral manifestations (Z. Song 2018, p. 3759).

This concept of dual unity is profoundly reflected in the TCM classics. TCM classics, for instance, detail the anatomical features of the five zang-organs (such as their size, length, capacity, and weight) and also expound on their relationships with “shen” 神 (spirit), “hun” 魂 (ethereal soul), “po” 魄 (corporeal soul), “yi” 意 (intention), and “zhi” 志 (will) (Y. Li 2017, p. 818). The former details are a manifestation of the “physical body,” while the latter relationships represent the “visceral manifestation” aspect of the TCM understanding of the body. This latter emphasis on the interrelation of function, spirit, and even natural phenomena is precisely the core and essence of the “visceral manifestation” doctrine.

The term “zangxiang” 藏象 first appears in the Suwen: Liujie Zangxiang Lun 素問·六節藏象論 (Basic Questions: Discourse on the Six Rhythms and Visceral Manifestations). “Zang” 藏 (to store) refers to the internal organs hidden within the body, while “xiang” 象 (phenomena) refers to the physiological and pathological phenomena manifested externally (Tian 2005, p. 18). The theory of “zangxiang” is the doctrine that studies the physiological functions, pathological changes, and mutual relationships of all the zang-organs. In this theory, the human body’s interior is interconnected and interacts with the external natural environment, forming a single whole. The theoretical framework of the TCM body is built on three core concepts: “qi” 氣 (vital energy), used to explain the origin and generation of human life; “yinyang” 陰陽 (Yin-Yang), used to explain the life activities of a person, presenting a dynamic interplay between complementary opposites; and “Wuxing” 五行 (Five Phases), primarily used to explain the physiological functions of the five zang-organs and, through the five phases, to link these organs with the external natural environment. The body’s physiological activities are understood through the “zang-fu” 臟腑 system, wherein the “zang” 臟 (zang-organs) store vital essences, while the “fu” 腑 (fu-organs) transform and transport food and fluids. The channels that connect the interior and exterior and circulate “qi” and blood are the “jingluo” 經絡 (meridian network).

In summary, the TCM view of the human body prior to the introduction of Western medicine was a mature and self-consistent cognitive system. It originated from intuitive physical anatomy but did not stop there; rather, it made a conceptual leap to develop a theory of visceral manifestation centered on life activities and imbued with profound philosophical thought. It does not demand a one-to-one correspondence with morphological structures but instead dedicates itself to constructing a functional, relational model capable of explaining complex life phenomena and guiding clinical diagnosis and treatment. In contrast to the mechanical model of Western biomedicine, TCM emphasizes holism, individual variation, and resonance with nature (Dal Lin et al. 2020, pp. 4–6), offering a distinctly different but extremely valuable perspective on understanding life.

3. The Messenger and His Message: Benjamin Hobson’s Medical Evangelism and the Birth of the Quanti Xinlun

3.1. “Academic Evangelism”: Hobson’s Motives and the Strategy of Natural Theology

Before writing and publishing the Quanti Xinlun 全體新論 (Treatise on Physiology), Benjamin Hobson had already been engaged in medical and missionary work in China for over a decade. He followed the traditional model, supplementing his medical practice with oral preaching and the distribution of religious printed materials to spread doctrine. However, this traditional model, despite some success, encountered deep-seated cultural resistance and progressed slowly. In his Brief Notice of the Hospital at Kum-le-fau in Canton, during the Year 1851 (Hobson 1852), Hobson expressed his undisguised disappointment with the state of evangelism.

He reflected with distress, “especially after he has been for years engaged in the work, apparently to little purpose, and feels his youthful ardor giving place to a painful sense of his own insufficiency” (Hobson 1852, p. 1). The specific difficulties manifested themselves in several respects. The appeal of religious gatherings was declining. As Hobson observed, “Praise, reading the Scriptures, addresses, and prayer to God, have been solemnly performed; and the congregations, though not so large as formerly” (Hobson 1852, p. 1). Religious publications were even more widely scorned: “Repeated evidence has been afforded to us that the religious tracts and books distributed in the public streets and shops in this city are treated with great disrespect” and that “they are usually condemned at once, or set aside after inspection of the title-page” (Hobson 1852, p. 2).

Facing this dilemma, Hobson attributed it to the inherent cultural barriers of Chinese society, believing that “yet the mind clogged with prejudice is unwilling to abandon notions stereotyped by age, and to receive in their place those which are new and of foreign origin” (Hobson 1852, p. 1). He also sharply criticized TCM, stating that all Chinese medical practice was based on what he considered “their absurd system of physics” (Hobson 1852, p. 1).

The limited success of traditional evangelism methods prompted Hobson to explore a new path, which became the central motive behind his turn toward “xueshu chuanjiao” 學術傳教 (academic evangelism). He began compiling the Quanti Xinlun, hoping to employ advanced Western scientific theory to challenge traditional Chinese thought, thereby creating a more receptive ground for the spread of Christianity. As he described in his report, his intention went far beyond the mere dissemination of knowledge: “The aim of the author was to communicate knowledge on a subject of high importance to the medical art, and at the same time not devoid of interest to scholars and the common people; and while thus endeavoring to impart information on an interesting branch of science, the opportunity was not lost of drawing the reader’s attention to the many striking evidences of design, and the wisdom, power and goodness of the great Designer” (Hobson 1852, p. 2). This model of combining knowledge dissemination with religious concern had already been successfully practiced by figures like Matteo Ricci in the late Ming dynasty.

To achieve this dual purpose, Hobson adopted Natural Theology as the core argumentative framework in Quanti Xinlun. This idea, prevalent in Europe since the 18th century, aims to demonstrate the existence of an omnipotent God by highlighting the exquisite complexity of natural creation, especially the human body. This strategy is embodied in the book as a fixed narrative pattern: first, a detailed description of the morphology and function of a human organ, followed by the attribution of its astonishing perfection to divine design. For example, Hobson and Chen (1851, pp. 14–15) distinguish between the body’s voluntarily controlled systems (like the hands, feet, and sense organs) and the autonomous systems beyond the will’s control (like the heart, lungs, stomach, and intestines). He contrasts their physiological characteristics, noting the former “grows weary” while the latter “is never tired nor rests”. Citing specific data like “the heart beats 108,000 times [per day]” (心跳十萬八千次), he portrays the body as a precisely operating, autonomous creation far beyond human control, arguing that its perfect operation is empirical evidence of the Creator’s (God’s) existence. This a posteriori reasoning aimed to introduce the core concept of Christian monotheism through objective, neutral scientific language, bypassing the cultural resistance that direct preaching might provoke. Ultimately, the text’s narrative focus shifts naturally from physiological knowledge to praise for God: “We rely on the Lord’s great virtue and endowment for man, without which we cannot exist for a moment; how can we not deeply ponder and respect this” (上主之鴻庥大德、錫賦於人者、吾人頼之、不容少間、可不深思而敬佩也哉) (Hobson and Chen 1851, pp. 14–15). This clearly reveals his fundamental intention: to use bodily cognition as a medium to elevate the reader from awe at the human structure to reverence for the “Creator”.

However, Hobson was not satisfied with indirect philosophical arguments. He also adopted more direct religious propaganda in the book. This is reflected in his dedication of the final two chapters to Zaohua Lun 造化論 (“On Creationism”) and Linghun Miaoyong Lun 靈魂妙用論 (“On the Wondrous Use of the Soul”). These systematically preached the complete Christian doctrine, from God’s creation of man and original sin to redemption, and explicitly declared: “Christ the Savior is the physician of the soul; the Old and New Testaments are the prescriptions for the soul” (救世主基督、靈魂之醫師也、新舊約聖書、靈魂之方薬也) (Hobson and Chen 1851, p. 71). This structural arrangement thoroughly revealed his ultimate goal: not purely medical enlightenment, but the salvation of the soul. As Su (2020, p. 154) states, Hobson’s original intention in translating was to use the dissemination of medical knowledge to make the Chinese people accept the Christian faith. Gao (2024, p. 113) further points out that missionaries consciously used anatomy as a sharp weapon to criticize and negate Chinese medicine.

This knowledge dissemination model, with science as its medium, produced marked effects. On one hand, progressive Chinese intellectuals like Liang Qichao 梁啟超 showed receptivity to the Western view of the body; on the other hand, the TCM community, facing significant challenges, began a path of scientization and self-reform (see Section 5). The missionaries’ translation activities thus became a microcosm of the Sino-Western cultural power dynamic. They constructed a new cultural authority based on scientific discourse, such as anatomy, but their deeper religious core was ultimately selectively received and indigenously transformed by Chinese readers. This historical episode not only reflects the complex process of Western science’s eastward spread but also profoundly illuminates the inherent tensions in the dynamics among power, faith, and reception in knowledge dissemination.

3.2. From Manuscript to Printed Book: The Publication and Dissemination of the Quanti Xinlun

According to Su (2020, pp. 139–42), the compilation and translation of the Quanti Xinlun was not accomplished in a short period of time. Hobson had conceived the idea of writing a medical textbook as early as 1848 and formally began writing around 1849. The book was originally conceived as lecture notes for Hobson’s Chinese apprentices. The main content of the book was compiled and translated from the fourth edition (1837) of Jones Quain’s Elements of Descriptive and Practical Anatomy for the Use of Students.

The Quanti Xinlun, in one volume comprising 39 chapters, systematically introduced foundational knowledge of the human body’s composition, the functions of major organs, blood circulation, and the digestive and reproductive systems. The book also included over 200 detailed human anatomical illustrations. As the first systematic work on Western medical anatomy in the Qing dynasty, Hobson deliberately adopted a popular and easy-to-understand language style, aiming for concise content. This choice was a response to the context, as overly profound and complex content would have become an obstacle to knowledge dissemination for Chinese readers who had no foundation in Western medicine.

The book was met with great popularity as soon as it was published. Hobson recorded in his 1851 report that “1200 copies have been printed” of the first edition, and the market response was enthusiastic that within less than a year, the printing of a “second edition of 2000 is now commenced” (Hobson 1852, p. 2). He wrote: “The book has met with acceptance, and has been spoken of in terms of commendation by several Chinese scholars and native doctors” (Hobson 1852, p. 2). The famous modern Chinese thinker Wang Tao (王韜, 1828–1897) mentioned the Quanti Xinlun several times in his diary. A friend of Wang Tao’s praised the Quanti Xinlun, stating it was “universally acclaimed far and wide, and buyers did not balk at the high price” (遠近翕然稱之,購者不憚重价) (Wang 2015, p. 288).

The strong market demand also gave rise to unauthorized recarved editions. The earliest pirated edition appeared as early as January 1852, a testament to its popularity. Subsequently, the Shanghai Mohai Shuguan 墨海書館 (The London Missionary Society Press) published it under Hobson’s authorization, and this edition became the most widely circulated version in later years. The book’s dissemination path was not limited to traditional book circulation. From 1853 to 1856, the Quanti Xinlun was also serialized in Hong Kong’s earliest Chinese monthly, the Xia’er Guanzhen 遐邇貫珍 (Chinese Serial). The serialization in this popular periodical, which had a circulation of 3000 copies per issue, greatly expanded its readership. Its influence even crossed national borders. As early as 1857, a recarved edition of the Quanti Xinlun appeared in Japan (Zhao 1991, p. 76), once again demonstrating the rapid and extensive dissemination of the work.

4. The Shock of New Knowledge: Cognitive Reshaping and the Visual Revolution of Anatomical Knowledge

The anatomical knowledge brought by the Quanti Xinlun deeply challenged the previous TCM understanding of the human body. While anatomical practices existed in ancient China, Hobson introduced a markedly different structural paradigm. This cognitive concept of Western medical anatomy, which emphasizes the concrete and empirical, gradually changed TCM’s bodily cognition, which emphasizes holism and connection. A separate but related impact occurred in linguistics. During the process of translating these anatomical works, missionaries like Hobson repeatedly deliberated on medical terminology. Many of these translated terms were later adopted, laying a foundation for modern medical translation.

4.1. New Anatomy: The Challenge from “Heart Governs the Spirit” to “Brain Governs the Spirit”

The translation, publication, and dissemination of the Quanti Xinlun introduced an entirely new body of knowledge about the human body, impacting the medical knowledge system that was still dominated by TCM at the time. The Quanti Xinlun described in detail the position, morphology, and functions of each organ of the human body, and explained the functional roles of the skeletal, muscular, circulatory, and respiratory systems. These represented theoretical frameworks fundamentally distinct from those of TCM.

Among these, highly representative was the shock of the Western medical view of “nao zhu shenming” 腦主神明 (Brain Governs the Spirit) to the TCM view of “xin zhu shenming” 心主神明 (Heart Governs the Spirit). Traditional Chinese medicine prioritized the “Heart” and marginalized the “Brain”, regarding the “Heart” as the “junzhu zhi guan” 君主之官 (monarch official), the master of life activities, and the “wuzang liufu zhi zhu” 五臟六腑之主 (lord of the five “zang” and six “fu” organs), endowed with the function of governing the operations of the viscera. The “Brain”, meanwhile, was merely a supplement to the “zang-fu” theory system (Xin et al. 2023, p. 515). Its core concept, “Heart Governs the Spirit”, originates from the Suwen: Linglan Midian Lun 素問·靈蘭秘典論 (Basic Questions: Discourse on the Orchid Pavilion Secret Classic), meaning the Heart is the physiological basis for mental, conscious, cognitive, and emotional activities (Tian 2005, p. 17). This view united body and mind, locating the center of cognition and emotion in the “Heart” within the chest cavity.

From the perspective of Western anatomy, however, empirical observation and localization suggested that the cerebral cortex functions as the center of higher neural activity, responsible for logic, memory, perception, and consciousness. This anatomical model presented a structural challenge to the TCM emphasis on the “Heart,” asserting within its own framework that the “Brain” is the master of the body. This is clearly stated in his chapter “Discourse on the Brain as the Master of the Whole Body” (Nao wei quanti zhi zhu lun 腦爲全體之主論), which begins: “The ancients said man is the spirit of all things, and all matters arise from the heart; in reality, they did not know the spirit resides in the brain…” (古人云、人爲萬物之靈、萬事皆發於心、實未知霊之在脳…) (Hobson and Chen 1851, p. 16). This anatomical model relocated the seat of cognitive and perceptual functions from the “Heart” to the “Brain” within the Western medical framework. The shift was revolutionary because it reduced the abstract “shen” 神 (spirit) of TCM theory to the physiological function of the brain, employing empirical scientific reasoning to challenge and contest the traditional doctrine of “Heart Governs the Spirit”. It thereby compelled the TCM community to re-examine the functions and status of both the “Heart” and the “Brain”.

The theory of blood circulation was another area of knowledge with far-reaching implications, deeply challenging the TCM “jingluo” 經絡 (meridian network) theory. The TCM meridian network system is a channel network connecting the body’s interior and exterior, circulating “qi” and blood. “However, the meridians themselves do not have a particular anatomical structure. Instead, they are merely tracts of tissue whose normal function is impeded when the relevant abdominal organs are stressed” (Y. Zhang 2021, p. 2637). The Quanti Xinlun revealed a physical system composed of blood vessels and nerves distributed throughout the body, a system with a clear anatomical basis. When anatomical practice could not find macroscopic physical structures in the human body corresponding to the meridian atlases, the existence of meridians was questioned under the paradigm of empirical science. This reflected a conflict between two epistemologies: one based on clinical function and empirical induction, the other on material evidence and structural reductionism. Due to their “invisibility” to empirical observation, meridians gradually became marginalized within the discourse of modern anatomical science.

Furthermore, the Quanti Xinlun’s interpretation of the respiratory system, reproductive organs, and other physiological domains offered an explanatory framework that fundamentally differed from that of TCM. It enabled Chinese readers to apprehend the human body from a new, structurally oriented perspective grounded in anatomical description.

In summary, the translation of the Quanti Xinlun introduced not only new scientific knowledge but also an empiricist worldview centered on “seeing is believing”. It redefined the human body from a dynamic functional organism animated by “qi” 氣 (vital energy) and “shen” 神 (spirit) into a physical and mechanistic structure composed of organs and tissues that could be dissected and analyzed. This paradigm shift, from macroscopic function to microscopic structure, posed an unprecedented challenge to TCM’s philosophical foundations, diagnostic logic, and therapeutic principles.

4.2. The Cognitive Power of Visual Revelation: Anatomical Atlases

Beyond its textual content, the more than 200 illustrations in the Quanti Xinlun exerted an equally deep impact. On a visual level, with an unambiguous directness, it transformed an abstract, functional “qihua shenti” 氣化身體 (the qi-transformed body) into a concrete, structural “shiti shenti” 實體身體 (physical body). The power of this visual evidence was, in many cases, more subversive than textual exposition alone. By systematically visualizing the interior of the human body, the work constructed a new cognitive framework for bodily understanding.

This visual revolution first manifested in the Quanti Xinlun’s revelation of certain anatomical structures that traditional TCM atlases had scarcely depicted in detail. Within the traditional TCM worldview, the human body was perceived as “dark, private, and largely invisible” (Liu 2018, p. 54). Therefore, in TCM’s visual knowledge system, most of the body’s structures were “invisible”. Its atlas drawings were mostly limited to the core “zang-fu” 臟腑 (viscera) organs, lacking precise morphological depictions of muscles, blood vessels, nerves, or even the internal structures of the brain, eyes, and ears. However, the Quanti Xinlun presented these once “invisible” tissues, such as the forms of muscles, the paths and distribution of blood vessels, with unambiguous realism. Among these, Western anatomy’s emphasis on musculature marked a distinct cultural divergence. As Kuriyama (2002, p. 111) observes, in the ancient periods of many countries such as China, “ignorance” of musculature was actually the rule. He further elucidates that the Western focus on muscular definition is not a universal perception but a historical product, arguing that present intuitions about human muscularity are largely indebted to the history of Western art (Kuriyama 2002, p. 112). The visual presentation in the Quanti Xinlun generated a far-reaching cognitive impact on contemporary readers and vividly demonstrated the empirical basis of Western medicine grounded in this specific artistic and anatomical tradition.

On the “zang-fu” diagrams, which both Chinese and Western medicine had depicted, the collision between the two bodily views was most intense.

By comparing the traditional TCM atlas Wuzang Zhengmian Tu 五臟正面圖 (Front View of the Five Zang-organs) from the early Qing text Xunjing Kaoxue Bian 循經考穴編 (An Investigation of Meridian Acupoints) with the Pou Qianshen Jian Zangfu Tu 剖前身見臟腑圖 (Anatomical View of the Viscera from the Front) from the Quanti Xinlun, we can observe a striking contrast between schematic representation and realistic depiction.

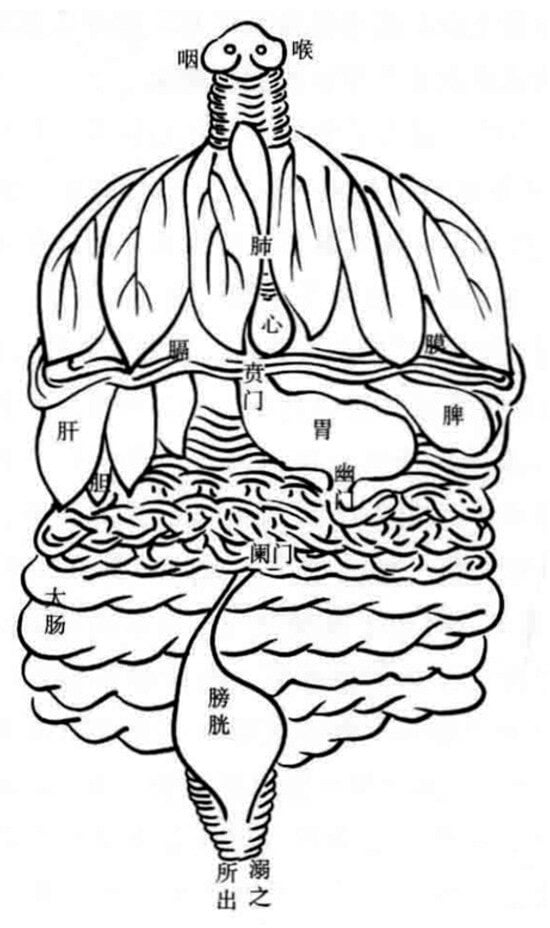

Traditional TCM atlases like the Wuzang Zhengmian Tu (Figure 1) were primarily diagrammatic in purpose rather than physically representational (Chen 2023, p. 40). This image is highly schematic and conceptual, aiming to display the functional relationships and approximate locations of the five zang-organs within TCM theory. For example, the image depicts the Lungs as a splendid canopy covering the Heart, vividly illustrating the functional concept of the Lungs as protecting the monarch organ (the Heart) and governing the circulation of all vessels. The organs in the chart are arranged orderly, but the lines are simple and completely planar, lacking realistic three-dimensionality, spatial relationships, and volumetric proportion. This reflects that the TCM understanding of the “zang-fu” is focused on the visceral manifestation doctrine, which emphasizes the functions, attributes, and connections with the meridians of the “zang-fu” organs, rather than their physical morphology. It depicts a philosophical body that is meant to be understood through interpretation rather than observation.

Figure 1.

Wuzang Zhengmian Tu (Front View of the Five Zang-organs) from Xunjing Kaoxue Bian. The Chinese labels indicate the primary internal organs, including: pharynx (咽), larynx (喉), lungs (肺), heart (心), liver (肝), gallbladder (胆), spleen (脾), stomach (胃), large intestine (大肠), and bladder (膀胱). Source: (Yan 2021, p. 118).

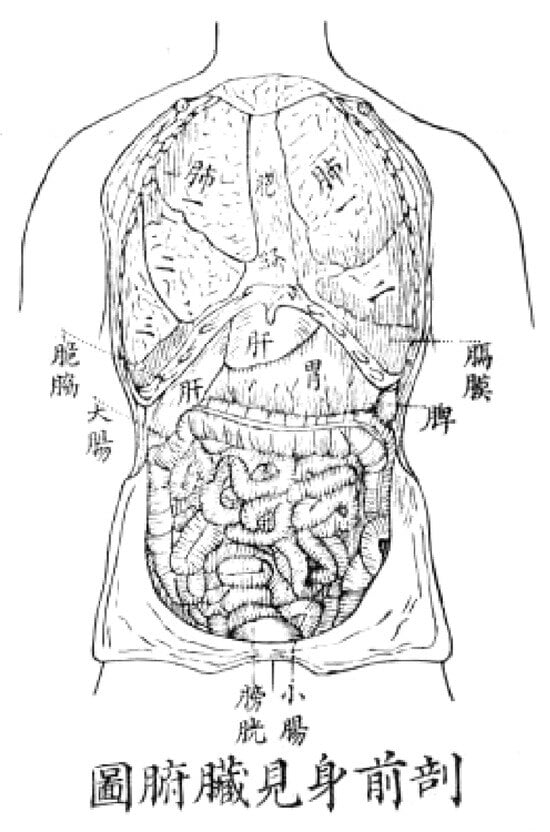

In stark contrast is the Pou Qianshen Jian Zangfu Tu (Figure 2) from the Quanti Xinlun. This image emphasizes visual accuracy and anatomical realism, striving to objectively and faithfully record the internal structure of the human body. It employs shading and intersecting lines to convey three-dimensional depth, presenting a tangible, structurally coherent “physical body” to the viewer. In the image, the position of the diaphragm, the enormous volume of the liver and its partial covering of the stomach and intestines, and the true state of the intertwined small and large intestines are all depicted in accordance with anatomical facts. It is not meant to illustrate the generation and overcoming cycles of the “Wuxing” (Five Phases), but to present the anatomical configuration of physical space. It displays a physical body that can be “viewed”.

Figure 2.

Pou Qianshen Jian Zangfu Tu (Anatomical View of the Viscera from the Front) from Quanti Xinlun The Chinese labels identify the primary organs, including: lungs (肺, with numbered lobes), heart (心), diaphragm (膈膜), liver (肝), gallbladder (胆), stomach (胃), spleen (脾), large intestine (大腸), small intestine (小腸), and bladder (膀胱). Source: Modified from (Hobson and Chen 1851, p. 38).

When the two are juxtaposed, a striking cognitive contrast emerges at the visual level. The “facts” presented by the Pou Qianshen Jian Zangfu Tu, which could be directly observed, forced the viewer to re-examine the meaning of the Wuzang Zhengmian Tu. The authority of the latter’s abstract and schematic nature, as a form of knowledge, was shaken in the face of the former’s unambiguous materiality. This impact was fundamental: it was no longer a debate between two theoretical systems, but one side presenting “seeing is believing” evidence. This overwhelming visual advantage effectively established the discursive authority of Western medicine’s empirical rigor and precision, and fundamentally challenged the traditional position of TCM theory, which could only be understood within its own self-contained conceptual framework.

4.3. The Language of a New Body: Terminology Creation and Transformation in Hobson’s Translation

The introduction of Western medical anatomy in the late Qing period encountered a central challenge in the translation of medical terminology. Confronted with an entirely new knowledge system, Hobson adopted two core strategies: borrowing with transformation and direct creation. This process constituted not merely a linguistic conversion but a cognitive reconstruction.

First was the “geyi” 格義 (matching concepts) strategy of borrowing and transformation. Hobson strategically adopted existing TCM vocabulary, stripping it of its functional and relational connotations, endowing it instead with precise, physical anatomical definitions.

One example was his adoption of the “zang-fu” 臟腑 (viscera) framework. While he retained familiar “zang-fu” terms like “Xin” 心 (Heart), “Gan” 肝 (Liver), “Fei” 肺 (Lungs), and “Shen” 腎 (Kidneys), his descriptions in the Quanti Xinlun were based entirely on physical morphology, location, and function, dissolving their traditional connections to “Yin-Yang”, the “Wuxing”, and “qi”.

A second, more direct example was his translation of “vessel” into the existing term “mai” 脈. Hobson then subdivided this term informed by new anatomical knowledge, translating “arteries” into “xuemaiguan” 血脈管 (lit.: “blood-circulating vessels”) and “veins” into “huixueguan” 迴血管 (lit.: “blood-returning vessels”). This translation strategy, however, masked a fundamental ontological gap. As Kuriyama (2002, p. 48) elucidates, the traditional Chinese concept of “mai” cannot be simply equated with Western anatomical definitions of blood vessels or the pulse. Rather than static anatomical conduits as conceived in Western medicine, “mai” represented dynamic pathways intimately tied to the flow of “qi” and blood. This distinction is further supported by Lo and Barrett (2018, p. 70), who argue that the term “mai” is difficult to reconcile with “blood vessel” or “pulse” and suggests that a neutral term like “channel” is a better translation to capture its multidimensional nature. By mapping “vessel” directly onto “mai”, Hobson effectively reconfigured a fluid, functional concept into a fixed structural entity. This method infused the familiar term “mai” with new scientific knowledge of the circulatory system, thereby fundamentally distinguishing it from the traditional “mai” in the “jingluo” 經絡 system.

The second was the strategy of lexical creation and establishment to address conceptual voids. When lacking suitable old words for transformation, Hobson sought to construct a coherent knowledge system through the creation of new terms. Hobson and Chen (1851, Preface) noted: “This book has many names for the whole body. For those not found in China, new names are occasionally created, striving to match the name with the reality” (是書全體名目甚多、其爲中土所無者、間作以新名、務取名實相符).

A significant example was his creation of the term “xueguan” 血管 (lit.: “blood vessel”) to translate “blood vessel”. This new compound word precisely defined the tubular structure and continues to be used as the standard medical term today.

Additionally, Hobson used the term “quanti” 全體 (lit.: “the whole body”) as the translation for “anatomy”, a practice that gained acceptance from many contemporary scholars. For instance, Dudgeon’s Quanti Tongkao 全體通考 (A General Treatise on the Whole Body) and Osgood’s Quanti Chanwei 全體闡微 (An Elucidation of the Subtleties of the Whole Body) both adopted the “quanti” term. Chinese intellectuals of the time also accepted this translation, as seen in Liang Qichao’s 梁啟超 Bianfa Tongyi 變法通議 (A Discussion on the Necessity of Reform): “For the medical discipline, one is qualified who understands “quanti xue” 全體學 (anatomy studies), knows the pharmacopeia of all nations, and is versed in Chinese and Western disease names and treatments” (Liang 2002, p. 61). The wide acceptance and continued use of these neologisms by both missionaries and Chinese intellectuals represented a further internalization and acceptance of Western anatomical knowledge.

Therefore, terminology translation is not a mere linguistic detail in the history of dissemination but a core mechanism of cognitive transformation. Language thus became the arena where new knowledge and inherited conceptual frameworks clashed and converged. Through the scientization of existing vocabulary and the coining of new words to fill conceptual voids, Western anatomy gradually reshaped the basic imagination of the human body among the late Qing intellectuals, laying a solid cognitive foundation for modern medicine to take root in China.

4.4. The Transformation of the Cognitive Paradigm: The Shift from “Functional Organism” to “Physical Body”

The introduction of new knowledge, the visual shock of anatomical images, and the subtle transformation of terminology—Hobson’s multifaceted efforts in the Quanti Xinlun—collectively reshaped the conceptions of the human body among late Qing intellectuals. To a certain extent, this enriched and reconfigured the Chinese understandings of human physiological structure and function. While contemporary scholars and physicians continued to inherit and trust the fundamental theoretical systems and practical principles of TCM, such as “Yin-Yang”, the Five Phases, and the “zang-fu” 臟腑 organs, they also gradually began to accept, within specific medical practices and processes of knowledge reception, the explanatory frameworks of Western medicine grounded in anatomy, physiology, and empirical observation.

As Xiong (2010) observes, the distinction between Chinese and Western medicine lies in their underlying epistemic orientations: Western medicine best captures the spirit of classical Western science, which emphasizes the concrete and speaks of empirical evidence; Chinese medicine best captures the verve of traditional Chinese culture, which emphasizes the whole and speaks of connections (Xiong 2010, p. 578).

The introduction of Western medical anatomy reshaped the cognitive framework of the human body for contemporary scholars, promoting a shift from the concept of a functional, qi-based organism to that of a physical body. The traditional TCM view of the body, centered on “qixue yunxing” 氣血運行 (the circulation of “qi” and blood) and “yinyang wuxing” 陰陽五行 (“Yin-Yang” and the Five Phases), emphasizes the dynamic balance and holistic coordination of the “zang-fu” 臟腑 (viscera) organs and “jingluo” 經絡 (meridian network). Its depictions of the “zang-fu” organs were often functional and symbolic, such as “xin zhu shenming” 心主神明 (Heart Governs the Spirit) and “gan zhu shuxie” 肝主疏泄 (Liver Governs the free flow of “qi”), and did not rely on precise anatomical morphology.

In contrast, Western anatomy, since the Renaissance, has been based on physical dissection and organology, seeking to reveal the true internal structure of the body through the decomposition of corpses. The anatomical atlases first introduced in the Qing dynasty through translated works like the Quanti Xinlun not only provided unprecedentedly intuitive images but also depicted the body using organs, tissues, bones, and blood vessels as the basic units. This visual culture and empirical knowledge, emphasizing “seeing is believing”, redefined the human body from a functional, qi-based organism into a physical body: a machine composed of tangible, measurable, and analyzable parts. This conceptual transformation not only challenged the traditional mode of thinking that relied on theoretical deduction and empirical judgment. It also laid the cognitive foundation for later modern medical education and pathological research.

Secondly, the introduction of anatomy through the Quanti Xinlun redefined the source of medical legitimacy, shifting it from canonical authority to empirical observation. The academic system of TCM had long based its legitimacy on citing classics and referencing canons. A physician’s authority derived mainly from familiarity with classics like the Huangdi Neijing 黃帝內經 (The Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic) and the Shanghan Lun 傷寒論 (Treatise on Cold Damage), and from the continuation of received teachings. In comparison, Western anatomy emphasizes repeatable and verifiable observational results; its knowledge authority is built on evidence visible to the naked eye. In the late Qing, as Western medical translations and anatomical atlases spread, more scholars came to see that medical reliability rested on direct observation and experiment, rather than textual exegesis. Consequently, the epistemological foundation of medicine was fundamentally shaken: ancient canons ceased to be the sole source of medical authority, and empirical methods emerged as new credentials for knowledge. This methodological innovation not only impacted the medical field but also reflected onto the broader intellectual world. It pushed late Qing scholars to rethink what constituted “credible knowledge” and to gradually accept the principle that scientific knowledge requires verification through experimentation and observation. In other words, the introduction of Western anatomy led Chinese society to shift its epistemic foundation from reliance on canonical authority to validation through empirical observation, opening a new cognitive path for the modernization of medicine and science.

In summary, the introduction of Western anatomy in the late Qing was far from simple knowledge grafting; it was a significant cognitive restructuring. It shifted the understanding of the human body among late Qing intellectuals from a “functional, qi-based organism” to a “physical body”, and the criterion of knowledge legitimacy from text-based classicism to empirical positivism.

5. From Blueprint to Reality: The Practical Significance of the Quanti Xinlun in China’s Medical Modernization

The value of the Quanti Xinlun lies not only in its pioneering dissemination of anatomical knowledge, but also in the fact that after its publication, like a stone cast into a lake, it created ripples throughout the Chinese medical world from the late Qing to the early Republican era, moving from a theoretical blueprint toward substantial practical reform. Its influence is mainly reflected in the following three aspects.

5.1. Laying the Cornerstone for Modern Medical Education

During the late Qing and early Republican periods, the modern medical education system was still in its formative stage, urgently needing systematic standard textbooks. Missionary translations played a core role in this context. As scholar Gao Xi states, medical textbooks of this period were primarily translated and introduced by missionaries (Gao 2023, p. 176). Hobson’s Quanti Xinlun, published in 1851, was recognized as the first relatively systematic Western medical textbook introduced to China (Tu 2023, p. 122) due to its detailed systematic exposition and precise anatomical illustrations. For thirty years, until the appearance of Osgood’s Quanti Chanwei in 1881, it remained the authoritative reference for anatomical instruction in China.

The book’s profound influence even left a distinct imprint on the personal memory of the literary giant Lu Xun 魯迅. As Lu Xun recalled in his 1922 “Preface” to Nahan 吶喊 (Call to Arms): “Physiology was not taught, but we saw some woodblock printings of the Quanti Xinlun and Huaxue Weisheng Lun 化學衛生論 (Treatise on Chemistry and Hygiene) and the like” (X. Lu 1976, p. 3). This reminiscence suggests that even in 1898, nearly half a century later, students at the Jiangnan Naval Academy (Jiangnan Shuishi Xuetang 江南水師學堂) still regarded the Quanti Xinlun as their introductory reader to Western physiology. Furthermore, the medical terminology established in the book was later integrated by Hobson into dictionaries and the Yixue Yinghua Zishi 醫學英華字釋 (A Medical Vocabulary in English and Chinese), laying a solid foundation for subsequent medical education and standardization.

5.2. Catalyzing the Self-Reform of Traditional Chinese Medicine

Western empirical medicine, as represented by the Quanti Xinlun, exerted a significant intellectual impact on the traditional TCM community, while also becoming a catalyst for its internal reform. Against this backdrop, the Zhongxi Huitong Xuepai 中西匯通學派 (the Convergence School of Chinese and Western Medicine), which sought to integrate China and the West, emerged. This school advocated using the empirical knowledge of Western medicine (especially anatomy) to reinterpret and supplement traditional TCM theories.

The Quanti Xinlun served as the core source of intellectual nourishment for the Convergence School of Chinese and Western medicine. One of its founders, Tang Rongchuan 唐容川, in his work Zhongxi Huitong Yijing Jingyi 中西匯通醫經精義 (The Essential Meaning of the Medical Classics of the Convergence of Chinese and Western Medicine) (published in 1892) (see Tang 2013), not only extensively cited Western medical theories but also directly used terms Hobson had pioneered in the Quanti Xinlun, such as “xueguan” 血管 (blood vessel), “tianrou” 甜肉 (lit.: “sweet meat” [pancreas]), and “naoqi jin” 腦氣筋 (lit.: “brain-qi sinews” [nerves]). Another representative figure, Zhu Peiwen 朱沛文, in his Huayang Zangxiang Yuezuanyan 華洋臟象約纂 (A Combination of Chinese and Western Anatomy Illustration) (1893), made extensive use of the anatomical atlases from the Quanti Xinlun, intending to systematically elucidate TCM’s “zangxiang” 藏象theory by introducing Western anatomical knowledge (Zhu 2014). Thus, the Quanti Xinlun not only provided the Convergence School with theoretical tools and visual resources but also became a key ideological driver of this important academic movement.

5.3. Shaping the Paradigm for Subsequent Medical Translation

The influence of the Quanti Xinlun is also manifest in its translation strategy, which established an important paradigm for later medical translation and introduction. Hobson adopted a “localization” translation strategy: linguistically, he strove for popular and easy-to-understand language that fit Chinese reading habits; theoretically, he strategically introduced existing TCM concepts, and his terminology translation largely adhered to the established expressions within the TCM system to lower the threshold of acceptance for contemporary intellectuals.

The success of this strategy not only significantly encouraged the missionary community, which subsequently stimulated further medical translation efforts, but its methodology also exerted a profound influence on later key translated works such as the Quanti Chanwei 全體闡微 and the Quanti Tongkao 全體通考. Many of the terms first translated by Hobson in the book that were widely accepted were adopted by later translators, becoming the foundation of the modern Chinese medical lexicon. The Quanti Xinlun not only introduced knowledge but also established a method for its dissemination, thereby exerting far-reaching historical influence.

6. Conclusion: Translation, Transformation, and Reshaping—The Significance of the Quanti Xinlun in the History of Knowledge Development

As an intersection of Christian dissemination and knowledge development in the late Qing, Hobson’s Quanti Xinlun serves as a lens to reveal the significant disruptions and profound transformations experienced by the traditional knowledge system under the influence of Western learning. Through an examination of its translation strategies, knowledge system, and dissemination practices, this study highlights the crucial role of this pioneering translation in the process of knowledge transformation in modern China.

This research first demonstrated how the Quanti Xinlun, with its knowledge system based on empirical anatomy, fundamentally challenged the traditional TCM body view, a qi-centered functional model rooted in the visceral manifestation doctrine. This process, initiated by translation, was not merely an introduction of new knowledge but a cognitive revolution: it encouraged the Chinese intellectual world to adopt an empiricist worldview grounded in direct observation, transforming the body from an abstract philosophical construct into a physical body that could be observed and dissected, thereby promoting the modernization of China’s traditional knowledge system.

Building on this, this paper further clarifies the threefold practical significance of this knowledge transformation. At the educational level, the Quanti Xinlun publication became a foundational textbook for Chinese medical education; in the medical field, it served as a stimulus for the self-reform of the Convergence School of Chinese and Western Medicine, and in the field of translation, its localization strategy established an influential paradigm for subsequent translations of Western knowledge.

However, the final historical echo of this knowledge dissemination, initiated by a Christian missionary, took a direction not anticipated by the author, illustrating the transformative nature of knowledge in cross-cultural communication. Hobson’s original intention was to prove the existence of the Creator through the logic of Natural Theology, serving his religious faith. But this blueprint, with theology at its core, underwent selective acceptance in the Chinese context. The late Qing intellectual world eagerly embraced the scientific methodology in the book but did not accept its underlying theological framework wholesale.

The translation of the Quanti Xinlun was not a passive infusion of knowledge, but a profound paradigm shift within the Chinese intellectual sphere. What late Qing scholars absorbed was not only anatomical knowledge itself, but a new knowledge authority independent of traditional canonical exegesis: the “empirical” spirit. The empirical evidence in the Quanti Xinlun fundamentally challenged the traditional scholarly method centered on citing classics and referencing canons, forcing scholars to re-examine and re-verify ancient discourses that had once been considered indisputable. This methodological impact not only gave rise to academic attempts to reconcile new and old knowledge, such as the Convergence School of Chinese and Western Medicine, but also altered the rules and standards of academic debate. This transformation was therefore not merely an increment of knowledge, but an iteration in the very methodology of knowledge production, marking a shift from the authority of text-based classicism to that of empirical positivism.

In summary, the case of the Quanti Xinlun exemplifies the complex role played by Chinese Christianity in knowledge development. It not only reshaped the medical elites’ and reformist intellectuals’ cognition of their own bodies but also, at the levels of education, medicine, and thought, provided a key blueprint for Chinese society’s modern transformation—a blueprint which, though penned by missionaries, was ultimately colored in by the Chinese people themselves. This history is not only one of medical evolution but also a cross-cultural history of how knowledge is translated, selected, transformed, and finally, woven into the fabric of indigenous intellectual life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.M. and S.M.; methodology, N.L.; investigation, S.M. and N.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, W.M.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TCM | Traditional Chinese Medicine |

References

- Ban, Gu 班固. 1962. Hanshu 漢書 [The Book of Han]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bosmia, Anand N., Toral R. Patel, Koichi Watanabe, Mohammadali M. Shoja, Marios Loukas, and R. Shane Tubbs. 2014. Benjamin Hobson (1816–1873): His Work as a Medical Missionary and Influence on the Practice of Medicine and Knowledge of Anatomy in China and Japan. Clinical Anatomy 27: 154–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Man Sing 陳萬成, Yuen Mei Law 羅婉薇, and Wing Hang Kwong 鄺詠衡. 2013. Wanqing xi yixue de yishu: Yi Xiyiluelun, Fuyingxinshuo liangge gaoben weili 晚清西醫學的譯述:以《西醫略論》、《婦嬰新說》兩個稿本為例 [Revisiting ‘Collaborative Translating’ in Late Qing China: The Draft Manuscripts of Xiyi Luelun and Fuying Xinshuo]. Zhongguo Wenhua Yanjiusuo Xuebao 中國文化研究所學報 [Journal of Chinese Studies] 56: 243–93. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Lyu-Hua, and Li-Yun Chen. 2022. Discussion of Medicine and Religion: Study of Missionary Hospitals in Modern Shanghai, China. Chinese Medicine and Culture 5: 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Shuiping 陳水平. 2023. Hexin yishu “Quanti Xinlun” zhong jiepou chatu de shijue xiuci yiyi 合信譯述《全體新論》中解剖插圖的視覺修辭意義 [The Visual Rhetorical Significance of Anatomical Illustrations in Benjamin Hobson’s Translated Work Quanti Xinlun]. Shanghai fanyi 上海翻譯 [Shanghai Journal of Translators] 1: 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yongsheng 陳永生, and Sumeng Zhang 張蘇萌. 1997. Wanqing xiyixue wenxian fanyi de tedian ji chuban jigou 晚清西醫學文獻翻譯的特點及出版機構 [Features of Translation of Western Medical Literatures and Publishing Institutions in Late Qing Dynasty]. Zhonghua yi shi za zhi 中華醫史雜誌 [Chinese Journal of Medical History] 27: 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, Chuan Chiang, and Shu-Yi Wang. 2024. Christian Ethical Foundations of Modern Nursing in China. Journal of Christian Nursing 41: E32–E37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Lin, Carlo, Fabrizio Ferrari, Fabio Zampieri, Francesco Tona, and Elena Osto. 2020. From Traditional Mediterranean, Ayurvedic and Chinese Medicine to the Modern Time: Integration of Pathophysiological, Medical and Epistemological Knowledge. Longhua Chinese Medicine 3: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Xi 高晞. 2008. “Jiepouxue” zhongwen yiming de youlai yu queding: Yi Dezhen “Quanti Tongkao” wei zhongxin 「解剖學」中文譯名的由來與確定—以德貞《全體通考》為中心 [The Source and Determination of the Chinese Translation of “Anatomy”: With reference to J·Dudgeon’s Quan Ti Tong Kao]. Lishi Yanjiu 歷史研究 [Historical Research] 6: 80–104+191. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Xi 高晞. 2023. Yan ming zheng shen: “Geshi jiepouxue” yiben de shuming he shuyu—Jian lun xiyi zhishi zhongwenhua de lujing yu fangfa 驗名證身:《格氏解剖學》譯本的署名和術語—兼論西醫知識中文化的路徑與方法 [A Study on Authorship and Terminology of Gray’s Anatomy in Chinese with Some Remarks on Paths and Methods of Translation of Western Medical Knowledge]. Fudan xuebao (shehui kexue ban) 復旦學報(社會科學版) [Fudan Journal (Social Sciences)] 65: 167–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Xi 高晞. 2024. Shenti xinzhi: Zai ziran shenxue yu ziran kexue zhijian 身體新知:在自然神學與自然科學之間 [New Insights into the Body: Between Natural Theology and Anatomy]. Jindai shi yanjiu 近代史研究 [Modern Chinese History Studies] 1: 112–28+160–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, Benjamin. 1852. Brief Notice of the Hospital at Kum-le-fau in Canton, During the Year 1851. Guangzhou: [Kum-le-fau Hospital]. Available online: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/v3dwqh7f (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Hobson, Benjamin, and Xiutang Chen 陳修堂. 1851. Quanti Xinlun 全體新論 [Treatise on Physiology]. Guangzhou: Hui’ai Hospital, From the Harvard-Yenching Library. Available online: https://id.lib.harvard.edu/alma/990082133290203941/catalog (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Jin, Shiying 靳士英, and Pu Jin 靳朴. 1996. “Cunzhen Tu” yu “Cunzhen Huanzhong Tu” kao 《存真圖》與《存真環中圖》考 [Research on Cunzhen Tu and Cunzhen Huanzhong Tu]. Ziran Kexue Shi Yanjiu 自然科學史研究 [Studies in the History of Natural Sciences] 15: 272–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama, Shigehisa. 2002. The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Chuanbin 李傳斌. 2005. Yixue chuanjiaoshi yu jindai zhongguo xiyi fanyi mingci de queding he tongyi 醫學傳教士與近代中國西醫翻譯名詞的確定和統一 [Medical Missionaries and the Determination and Unification of Modern Chinese Western Medical Translation Terminology]. Zhongguo Wenhua Yanjiu 中國文化研究 [Chinese Culture Research] 4: 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Ling 李靈, and Qinhe Xiao 肖清和. 2018. Jidujiao Yu Jindai Zhongguo Jiaoyu 基督教與近代中國教育 [Christianity and Education in Modern China]. Shanghai: Shanghai Translation Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yanran, and Na Yan. 2025. Traditional Chinese Medicine Recorded by Missionaries (1887–1932): A Study Centered on The China Medical Missionary Journal. Chinese Medicine and Culture 8: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Youqiang 李有強. 2017. Zhongyi shenti guan ji qi yundong yangsheng sixiang 中醫身體觀及其運動養生思想 [How traditional Chinese medicine views the body and nurtures life with physical exercises]. Beijing Zhongyiyao Daxue Xuebao 北京中醫藥大學學報 [Journal of Beijing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine] 40: 817–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Qichao 梁啟超. 2002. Bianfa tongyi 變法通議 [A Discussion on the Necessity of Reform]. Beijing: Huaxia Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Tao 劉濤. 2018. Tuhui “xiyi de guannian”: Wanqing xiyi dongjian de shijue xiuci shijian 圖繪「西醫的觀念」:晚清西醫東漸的視覺修辭實踐 [Mapping the Idea of Western Medicine: Searching for Visual Rhetoric Practice of Western Medicine Discourse in Late Qing Dynasty]. Xinwen yu Chuanbo Yanjiu 新聞與傳播研究 [Journalism & Communication] 25: 45–68+127. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, Vivienne, and Penelope Barrett, eds. 2018. Imagining Chinese Medicine. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Mingyu 盧明玉. 2012. Wanqing chuanshi xixue fanyi yu qiangguo zhi ce de tansuo: Yi “Education in Japan” ji qi zhongwen yiben wei li 晚清傳教士西學翻譯與強國之策的探索—以“Education in Japan”及其中文譯本為例 [A Probe into the Western Learning Translations by Missionaries and the Strategy of Strengthening the Nation in the Late Qing Dynasty: A Case Study of “Education in Japan” and Its Chinese Translation]. Gansu Shehui Kexue 甘肅社會科學 [Gansu Social Sciences] 2: 240–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Mingyu, Tianxiang Zheng, and Keyu Wang. 2023. Reinterpreting and Remapping Philosophy, Evolutionism and Religion in Late Qing Missionary’s Translation of The Making of a Man. Religions 14: 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Xun 魯迅. 1976. Nahan 吶喊 [Call to Arms]. Beijing: People’s Literature Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Marié, Éric. 2011. The Transmission and Practice of Chinese Medicine: An Overview and Outlook. China Perspectives 2011: 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Wensheng. 2014. Chinese Translations of Legal Terms in Early Modern Period: An Empirical Study of the Books Compiled/Translated by Missionaries around the Mid-Nineteenth Century. Semiotica 2014: 167–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, Vivien, Rui Diogo, and Isabelle C. Winder. 2022. Hiding in Plain Sight—Ancient Chinese Anatomy. The Anatomical Record 305: 1201–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Yonglin 宋永林. 2020. Wanqing shiqi han yi xiyi shuji de bianji chuban gaikuang, tedian ji yingxiang 晚清時期漢譯西醫書籍的編輯出版概況、特點及影響 [The Editing and Publishing Situation, Characteristics and Influence of Chinese Translation of Western Medicine Books in the Late Qing Dynasty]. Tushuguan 圖書館 [Library] 9: 108–11. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Zhenxing 宋鎮星. 2018. Zhongyi jiepouxue xin xi 中醫解剖學新析 [New analysis of traditional Chinese medicine anatomy]. Zhonghua Zhongyiyao Zazhi 中華中醫藥雜誌 [China Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy] 33: 3759–62. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Jing 蘇精. 2020. Xiyi Laihua Shiji 西醫來華十記 [Ten Accounts of Western Medicine Coming to China]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Xilei 孫希磊. 2008. Jidujiao yu zhongguo jindai yixue jiaoyu 基督教與中國近代醫學教育 [Christianity and Modern Medical Education in China]. Shoudou Shifan Daxue Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) 首都師範大學學報(社會科學版) [Journal of Capital Normal University (Social Sciences Edition)] S2: 133–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yanbing, and Haoyuan Ma. 2023. Comments on Missionary Translation of Chinese Biology Treatises in the Qing Dynasty. Voprosy Istorii 1: 278–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Zhou 孫琢. 2010. Jindai yixue shuyu de chuangli—Yi Hexin ji qi Yixue Yinghua Zishi wei zhongxin 近代醫學術語的創立——以合信及其《醫學英華字釋》為中心 [The Creation of Modern Medical Terms—A Case Study of Benjamin Hobson (1816—1873) and His A Medical Vocabulary in English and Chinese]. Ziran Kexue Shi Yanjiu 自然科學史研究 [Studies in the History of Natural Sciences] 29: 456–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Rongchuan 唐容川. 2013. Tang Rongchuan Yiji Jingdian 唐容川醫籍經典 [Classic Medical Works of Tang Rongchuan]. Taiyuan: Shanxi Science and Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Daihua 田代華, ed. 2005. Huangdi Neijing Suwen 黃帝內經素問 [Basic Questions of the Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic]. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Yuqiu 塗雨秋. 2023. Cong zhishi chuandi dao sichao bianhua: Wanqing xiyi yizhu de yuedu yu yingxiang 從知識傳遞到思潮變化:晚清西醫譯著的閱讀與影響 [From Knowledge Transfer to Ideological Change: The Reading and Influence of Western Medicine Translations in the Late Qing Dynasty]. Chuban Kexue 出版科學 [Publishing Research] 31: 120–28. [Google Scholar]

- van der Weiden, R. M. F., and N. Mori. 2014. Benjamin Hobson (1816–1873): His Role in the Absorption of Western Medicine and Anatomy in Japan. Clinical Anatomy 27: 950–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Tao 王韜. 2015. Wang Tao Riji 王韜日記 [Wang Tao’s Diary]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Man Kong. 2024. An Encounter between Christian Medical Missions and Chinese Medicine in Modern History: The Case of Benjamin Hobson. Religions 15: 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Chen 辛陳, Yu Wang 王瑜, Jinsheng Yang 楊金生, and Peijing Rong 榮培晶. 2023. Zhongyi dui xin nao renzhi de yuanliu yu zouxiang 中醫對心腦認知的源流與走向 [The Origin, Development, and Trend of TCM’s Cognition of Heart and Brain]. Zhongguo Zhongyi Jichu Yixue Zazhi 中國中醫基礎醫學雜誌 [Journal of Basic Chinese Medicine] 29: 515–19. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Yuezhi 熊月之. 2010. Xixue Dongjian Yu Wanqing Shehui 西學東漸與晚清社會 [The Eastward Spread of Western Learning and Late Qing Society]. Beijing: China Renmin University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Zhen. 2021. Xunjing Kaoxue Bian 循經考穴編 [An Examination of Acupoints Along the Meridians]. Beijing: China Medical Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Daqing 張大慶. 1994. Zaoqi yixue mingci tongyi gongzuo: Boyi hui de nuli he yingxiang 早期醫學名詞統一工作:博醫會的努力和影響 [The Uniformity of Medical Terms in Early Period: A Review on the Work of the China Medical Missionary Association]. Zhonghua Yi Shi Za Zhi 中華醫史雜誌 [Chinese Journal of Medical History] 24: 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yi. 2021. Introduction of Human Anatomy before Modern China: The Preface of Anatomical Education in Mainland China. The Anatomical Record 304: 2632–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Pushan 趙璞珊. 1991. Hexin (Xiyi wuzhong) ji zai hua yingxiang 合信(西醫五種)及在華影響 [Benjamin Hobson’s (Five Western Medical Works) and Their Influence in China]. Jindai Shi Yanjiu 近代史研究 [Modern Chinese History Studies] 2: 67–83+100. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Shihan. 2025. Treating Opium Addiction in China: Medical Missionaries, Chinese Medicine, and the State, 1830–1910. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Peiwen 朱沛文. 2014. Huayang Zangxiang Yue Zuan 華洋臟象約纂 [A Combination of Chinese and Western Anatomy Illustration]. Guangzhou: Guangdong Science & Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.