Abstract

A common trope in Anglicanism is to refer to the Book of Common Prayer as “the Bible rearranged for public service.” This paper unpacks the complex and varied ways in which the 1979 American Book of Common Prayer uses and appropriates Scripture in the text of its liturgies. Relying on an earlier essay in Studia Liturgica where the author proposed a taxonomy to describe the various ways that any liturgical rite can use Scripture as a source within the text of the rite, he applies that taxonomy to the English and American Prayer Book tradition more generally and the current American BCP more specifically. He demonstrates not only that this taxonomy is just as applicable to modern liturgical texts as it is to ancient ones, but also that it provides a means to describe accurately the range of ways in which this particular BCP can rightly be said to be scriptural.

1. Introduction

A common trope in Anglicanism is to refer to the Book of Common Prayer (hereafter referred to as BCP) as “the Bible rearranged for public service” (Butterworth 1881, p. 116; Haller 2015, p. 12). But is this true? Is it any truer for the BCP than for other historic rites? This paper unpacks the complex and varied ways in which the Prayer Book tradition more generally and the current 1979 American BCP specifically uses and appropriates Scripture in the text of its liturgies. Chauvet (1992, pp. 121–33) points out that, “according to the living tradition of the Church, the only liturgy, in the true Christian sense, is one that is shaped by the Bible,” and there is no doubt that Thomas Cranmer would agree completely. The Bible has not only always been a liturgical text for Christians because it has always been read publicly when they gather for worship; the liturgical rites and the corresponding ceremonies also require the Scriptures for their meaning and interpretation.

2. Results

2.1. The Four General Categories

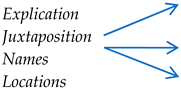

This exploration of the BCP’s use of Scripture is ordered around a taxonomy I developed elsewhere to precisely and clearly describe the various ways that a liturgical text can appropriate scripture (Olver 2019). This classification system is made up of a total of 12 categories arranged in a specific relationship to each other. The first four (Suggestion, Allusion, Quotation, and Appropriation) are the general strata into which all uses of Scripture in a liturgical text can be situated. The next five (Therefore, Pattern, Imitation, Composite, and Amended) are particular uses or subcategories of three of the main categories (namely, Allusion, Quotation, or Appropriation). The last four classifications (Explication, Names and Locations, and Juxtaposition) are not really categories at all, but rather additional features or qualities that can characterize any of the previous categories. The relationship of these categories, subcategories, and possible characteristics is best understood when they are depicted visually (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Visual depiction of the ways that Scripture is appropriated by liturgical texts.

In the earlier article, my examples were drawn exclusively from early Greek and Latin anaphoras. This article not only demonstrates that this taxonomy is just as applicable to modern liturgical texts but also describes with new precision and clarity the varied ways that the wider Prayer Book tradition, including the current American BCP, use Scripture as a source in some way or another. For each part of the taxonomy, I will briefly describe it and then provide several examples from throughout the BCP. Because the English BCP tradition was influenced most especially by the Roman Rite (especially the Sarum Use, originating at Salisbury Cathedral) and its eucharistic prayer, the Roman Canon Missae, I also will include examples from other liturgies, particularly from the liturgy that is the closest kin to the BCP tradition, the Roman rite, or from Eastern rites, if they were influential on the text in question. This form of the Roman Rite pre-dates the reforms of the Council of Trent and the Missal of Paul V which is promulgated. A comprehensive discussion of every use of Scripture in the American BCP would require a monograph; as such, this discussion is limited to noteworthy examples. Any reader familiar with the BCP undoubtedly will find that many other examples spring to mind as they read.

2.2. Suggestion

A Suggestion is the use of phrases or sentences from more than one place in Scripture whose purpose appears to be little more than to sprinkle the rite with a scriptural fragrance or “aroma” (2 Cor. 2.15). A Suggestion may often have the characteristic of what Hays (1989, p. 29) calls an “echo”; namely, that it “does not depend on conscious intention.” Determining authorial intention in this category and the next is quite difficult, especially when the identity of the author/redactor of a liturgical text is not clear. It is possible that an author or redactor who makes use of a Suggestion may not even have a specific passage or set of passages in mind when incorporating the words or phrases. The desire for the liturgical language to be Scriptural may just as well be expressed through the conscious use of Scriptural language as the less explicit use. The American BCP is full of such Suggestions.

One of the most wonderful collects in the BCP tradition which goes back to the first book of 1549 is that used for the first Sunday of Advent:

This is a representative example of Cranmer’s rhetorical brilliance and skill as a translator. As Jacobs (2019, p. 63) explains,Almighty God, give us grace that we may cast away the works of darkness, and put upon us the armor of light, now in the time of this mortal life in which thy Son Jesus Christ came to visit us in great humility; that in the last day, when he shall come again in his glorious majesty to judge both the quick and the dead, we may rise to the life immortal.(The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 159)

It was C. S. Lewis’s belief that the virtuosity [of Cranmer’s prose] arises from the need to adapt Latin devotional language to the very different character of English: Latin translated over-literally tends to be precious and pompous, and Cranmer was determined to avoid these traps. The Latin originals were [to quote Lewis] ‘almost over-ripe in their artistry’; the English of the BCP ‘arrests them, binds them in strong syllables, strengthens them even by limitations, as they in return erect and transfigure it. Out of that conflict the perfection springs.

This collect uses Scripture in several different ways, some of which I will return to later. For now, I only highlight the phrase “glorious majesty,” which is intentionally contrasted with “great humility.” This is the only place where “glorious majesty” appears in 1549, though it is used twice in the Coverdale psalter: first in Ps. 90.17 (“And the glorious majesty of the Lord our God be upon us”) and then again 104.31 (“The glorious majesty of the Lord shall endure forever”).1 “Glory” and “majesty” are both words that are frequently used in English translations of the Bible, and forms of both words are often found in proximity to each other (e.g., 1 Chron. 29.11; Job 40.10; Ps. 21.5; 45.3; Isa. 2.10, 19, 21; Dan. 4.36, 5.18; Heb. 1.3; Jude 1.25). But the source of the phrasing is much more complex. It is likely that “glorious majesty” is constructed from a tissue of scriptural borrowings, and the longer phrase “when he shall come again in his glorious majesty to judge both the quick and the dead” is combination of two identifiable biblical texts, modified to agree with the wording of the Nicene Creed, and incorporating a “doubling” inspired by the Latin version of one of the biblical passages. The beginning of the phrase seems to be based on Mt. 25:31—32 from the 1540 Great Bible: “When the Son of man cometh in his glory, and all the holy angels with him, then shall he sit upon the seat of his glory, and before him shall be gathered all nations.” The second part of the phrase also seems to come from the Great Bible from 2 Tim. 4:1: “I testify, therefore, before God and before the Lord Jesu Christ, which shall judge the quick and dead at his appearing in his kingdom.” A common feature in sixteenth century translations of Latin is to double the term in English when a single Latin word lies behind it, such as rendering multiplica as “increase and multiply,” “easing the rhythm and giving a sense of accumulation towards abundance” (Cuming 1983, p. 54; Nichols 2010, p. 18). In fact, this doubling by way of two synonyms is both a marked characteristic of Cranmer’s translation style and one which has precedent in classical Latin: “sins and wickedness,” “sore let and hindered,” bountiful grace and mercy,” “supplications and prayer,” “vocation and ministry,” “governed and sanctified,” “truly and godly,” “sundry and manifold” (Gray 2007, p. 568; Olver 2026, p. 336). The synonyms “glory” and “majesty” would seem to be Cranmer’s way of using Matt. 25:31 from the Latin Vulgate, Cum autem venerit Filius hominis in maiestate sua, et omnes angeli cum eo, tunc sedebit super sedem maiestatis suae: et congregabuntur ante eum omnes gentes, where maiestatis is rendered by the synonyms “glory” and majesty.”2 Thus, the use of the phrase in the collect gives the reader/speaker a heightened sense that this is the language of the Bible.

Another phrase that is found six times in the first English BCP and four times in the 1979 BCP is “precious blood,”3 and then twice more in the Communion service by way of the phrase “the most precious body and blood.”4 “Precious blood,” appears only once in the Great Bible of 1539 (the most current English translation available to Cranmer while compiling the 1549 BCP): “For as moch as ye knowe, how that ye were not redemed wyth corruptible thynges (as syluer & golde) from youre vayne conuersacion, whych ye receaued by the tradicion of the fathers: but wt the precious bloude of Chryst, as of a lambe vndefyled, and wythout spot” (1 Pet. 1.19).5 The notion that Jesus’ blood is precious, however, is one that is repeated a number of times throughout the New Testament: the way Jesus speaks of his own blood in the institution narratives as being “for the remission of sins” (Mt. 26.28; see also Mk. 14.24; Lk. 22.20) certainly implies this, along with his teaching that to eat his flesh and drink his blood brings eternal life in Jn. 6.53-56 and Paul’s discussion of how the cup of blessing in the communion of the blood of Christ (1 Cor. 10.16); the preciousness of Christ’s blood is also communicated when Paul addresses the elders in Acts 20: “Take hede therfore vnto youre selues & to all the flocke amonge whom the holy ghost hath made you ouersears, to rule the congregacyon of God which he hath purchased with his bloude” (Acts 20.28 GB). Think especially of how the Epistle to the Hebrews emphasizes the power and effectiveness of Christ’s blood (Heb. 9.7, 12, 14, 20; 10.19, 29; 12.24; 13.12, 20).6

Two more examples may be helpful. The phrase “whole heart” is found in the new confession of sin in the Holy Eucharist and is used repeatedly in the Bible: it marks Solomon’s love for God in 1 Chronicles (28.9; 29.9, 19), is used repeatedly in the Psalms (9.1; 86.12; 111.1; 119.2, 10, 34, 69, 145; 138.1) and twice in Jeremiah in connection to repentance (3.10; 24.7).7 In Rite II, Prayer B, the final petition at the end of the eucharistic prayer begins with the phrase, “in the fullness of time,” which combines the distinctive language of both Eph. 1.10 and Heb. 1.2 in such a way as to highlight’s the prayer’s Scriptural reliance. This highlights that some uses of Suggestion may contain a quotation. What distinguishes this from the latter category of Quotation is that, with a Suggestion, the phrase in question is found in more than one place in the Bible.

Suggestions are distinguished because they both draw from more than one place in the Bible (whether directly or indirectly) and the purpose of the use seems to be limited to simply indicating that this is a text that is saturated in Scripture. A Suggestion indicates something fundamental about Christian liturgy: it is never without the aroma of Scripture.

2.3. Allusion

The second major category is Allusion,8 which is when a liturgical text “expresses the same theme as the biblical text, but in different words” (De Zan 1997, pp. 331–65). Like Suggestions, the Prayer Book tradition is saturated in Allusions.

A salient example is in the second question to parents and godparents in the 1979 baptismal rite: “Will you by your prayers and witness help this child to grow into the full stature of Christ?” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 302). The exact form of these two questions is new to this American BCP9 and the particular phrase “the full stature of Christ” draws on the famous passage about the Body of Christ in Ephesians: “…until we all attain to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ” (Eph. 4.11-13). The baptism liturgy here clearly alludes to Eph. 4.13 but does not quote it directly.10 One may also hear in this language an allusion to Lk. 2.52, where Jesus is described as increasing “in wisdom and in stature, and in favor with God and man,” which the 1928 BCP quotes in the final prayer at the end of the rite for the Churching of Women after childbirth: “Grant, we beseech thee, O heavenly Father, that the child of this thy servant may daily increase in wisdom and stature, and grow in thy love and service, until he come to thy eternal joy” (The Book of Common Prayer 1928, p. 307).

A second example also comes from the baptismal rite. In the Thanksgiving over the Water, the appeal is made to two Old Testament events as typological anticipations of Christian baptism. (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, pp. 306–7). The first of these—“Over it [the water] the Holy Spirit moved in the beginning of creation”—alludes to the second verse in the Bible: “The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the Spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters” (Gen. 1.2). The second typological reference—“Through it you led the children of Israel out of their bondage in Egypt into the land of promise”—alludes to the story of the Exodus, of course, and Israel’s deliverance at the Red Sea in Exod. 13.17-15.27, a portion of which is one of the bare minimum of two lessons that always must be read at the Easter Vigil.11 Similarly, the three descriptions of what baptism does are also Allusions: “In it we are buried with Christ in his death” is a direct allusion to Paul’s nearly verbatim claim in Rom. 6.3-4, as well as Col. 2.12; “By it we share in his resurrection,” picks up the very next verse in Romans 6, where Paul explains that “if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his” (Rom. 6.5); and the final phrase, “Through it we are reborn by the Holy Spirit” alludes both to how John the Baptist contrasts his baptism with the baptism that is to come (“he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit [and with fire]”; Mt. 3.16; Mk. 1.8; Lk. 3.16; cf. Acts 1.5 and 11.16) and to the famous claim that Jesus makes in his conversation with Nicodemus: “unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God” (Jn. 3.5). More broadly, the blessing over the water is an accumulation of images, piled on top of each other. The individual allusions, references, echoes are evocative, but it is also helpful to note that their effect as a sequence is to develop a dense picture of salvation through water, while not losing the sense of water’s power to destroy.

A similar set of allusions is found in the opening Exhortation of the marriage rite. Like in the blessing of the baptismal water, this construction also makes three allusions to a Scriptural foundation for marriage, plus a reference to an instruction about honoring marriage: “The bond and covenant of marriage was established by God in creation” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 423) refers again to Genesis 2, which describes God’s acknowledgment of the need for a certain sort of close relationality that is marked by both difference and fruitfulness (cf. Gen. 2.18-24). Both Matthew (19.5) and Mark (10.7) recount that Jesus quotes the end of Gen. 2.24 when he is teaching on divorce: “Therefore a man leaves his father and his mother and cleaves to his wife, and they become one flesh.” The second allusion in the marriage Exhortation, “our Lord Jesus Christ adorned this manner of life by his presence and first miracle at a wedding in Cana of Galilee” refers to Jesus’ first miracle. This is only recorded in John’s Gospel (2.1-12) and in his unique gospel construction, it also functions as the first of the “signs” that indicates the divine identity and mission of Jesus. This revelation is also connected to the last Scriptural allusion in the marriage Exhortation: “It signifies to us the mystery of the union between Christ and his Church.” This is clearly an allusion to Ephesians 5, where Paul speaks about marriage and, like Jesus, quotes Gen. 2.24. He then provides the explanation, which is the source of the allusion: “This mystery is a profound one, and I am saying that it refers to Christ and the church” (Eph. 5.32). This theological rationale concludes with the additional note that “Holy Scripture commends it [marriage] to be honored among all people,” a clear reference to Heb. 13.4: “Let marriage be held in honor among all, and let the marriage bed be undefiled.” Here, as in the baptism liturgy, the text of the rite is undertaking an exegetical task: to provide an authoritative rationale for the current liturgical action (this means that it is also a Pattern use, the second Subcategory discussed below).12

Another Allusion repeated throughout all classical liturgical prayer is the formula that concludes prayers addressed to the Father, the addressee of most liturgical prayers. That conclusion, at a minimum, is “through Jesus Christ” or “through Jesus Christ our Lord.” The New Testament contains at least 5 references to or examples of prayer or ascriptions of praise being made “through Jesus Christ” (Rom. 1.8; 7.25; 16.27; Heb. 13.21; Jude 1.25; plus a great many more uses of the phrase itself, but in different contexts). Twice in 1 Peter, there is an indication that prayer—and, in fact, everything—is to be done “through Jesus Christ,” particularly the famous exhortation in chapter 2, that we are, “like living stones” to be “built into a spiritual house, to be a holy priesthood, to offer spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ” (1 Pet. 2.5). All this is premised on a fundamental principle of Christian prayer, which is discussed in depth in the Epistle to the Hebrews and also laid out in the instructions about prayer in 1 Timothy chapter 2: “First of all, then, I urge that supplications, prayers, intercessions, and thanksgivings be made for all men… For there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (1 Tim. 2.1-5). Most Christian liturgical prayers—and basically all those in the traditional collect structure—conclude “through Jesus Christ our Lord.” This practice is an allusion to the clear teaching of 1 Tim. 2 and corresponds to a practice that the New Testament itself witnesses.

These few examples of Allusions should provide an indication of just how this use is also repeated throughout the 1979 BCP.

2.4. Quotation

The third of the major categories is Quotation, which is much more specific than the first two general categories and often easier to identify. A Quotation is the verbatim reproduction of a phrase or sentence within a liturgical text, usually from a single biblical text. The collect for Advent 1 is not only one of the most felicitous and poetically beautiful of Cranmer’s original English compositions (Hatchett 1980, pp. 165–66), but it also contains a pristine example of Quotation: “Almighty God, give us grace that we may cast away the works of darkness, and put upon us the armor of light…” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 159). The biblical source is an equally melodious passage in Romans 13:

Besides this you know what hour it is, how it is full time now for you to wake from sleep. For salvation is nearer to us now than when we first believed; the night is far gone, the day is at hand. Let us then cast off the works of darkness and put on the armor of light; let us conduct ourselves becomingly as in the day, not in reveling and drunkenness, not in debauchery and licentiousness, not in quarreling and jealousy. But put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires.(Rom. 13.11-14)

The RSV here follows the very first English translation of this passage in Tyndale’s Bible of 1534 and which remains through the Great Bible and the King James, in all respects save one. Tyndale translates the phrase as “dedes of darcknes” and the Great Bible follows him. But in 1549, Cranmer sets aside the alliteration of “dedes of darcknes” and instead renders the phrase, “workes of darknes,” the phrase that users of the 1979 BCP know well (Cummings 2013, pp. 32–33). What is interesting is that the Authorized “King James” Bible of 1611 follows Cranmer in the BCP, not Tyndale’s Great Bible. The KJV renders the verse, “The night is farre spent, the day is at hand: let vs. therefore cast off the workes of darkenesse, and let vs. put on the armour of light” (Rom. 13.12; KJV). Here we see an example of how liturgical language can affect not only the language of biblical translations, but sometimes even original language manuscripts of the Bible.

A second example is in Eucharistic Prayer A in Rite II. As in all the Rite II eucharistic prayers, the 1979 BCP introduces a congregational acclamation to introduce the anamnesis. The memorial acclamations in Rite II are different in each of the respective eucharistic prayers, and the introduction to said acclamation in Prayer A is well known: “Therefore we proclaim the mystery of faith.” The phrase “mystery of faith” appears just once in the Bible, in 1 Tim 3.9: “Deacons likewise must be serious, not double-tongued, not addicted to much wine, not greedy for gain; they must hold the mystery of the faith with a clear conscience.”13 The origin of its phrase here is the ancient Roman Canon, where it is inserted into the institution narrative over the cup: “Take and drink from this, all of you: For this is the cup of my blood, of the new and eternal covenant, the mystery of faith: which will be poured out for you and for many for the remission of sins. As often as you do this, you will do it for my remembrance” (Hänggi and Pahl 1968, p. 434). In the current Roman Missal, the revisers retained the venerable Roman Canon as Eucharist Prayer I, save for one major change: after the elevation of the chalice, the phrase “mystery of faith” is transferred from inside the institution narrative to just after it as the priest’s introduction to one of three memorial acclamations that are all addressed to God, such as “We proclaim your death, O Lord, and profess your Resurrection unto you come again.”14 Strangely, Hatchett (1980, pp. 374–75) fails to mention the origin of this phrase in his otherwise usually very comprehensive commentary on the American BCP.

Like Suggestions and Allusions, Quotations are also all over the BCP, but one more example will suffice. The third to last collect of the year, Proper 27, did not enter the BCP tradition until the 1662 revision and comes from the margin of John Cosin’s Durham book. There was no collect for the Sixth Sunday after the Epiphany; if there happened to be six Sundays after the Epiphany, the collect, Epistle, and Gospel for the fifth Sunday were simply repeated.15 The introduction of the new collect and lessons solved this occasional problem and served to gather up the season of Epiphany before taking the turn towards Lent with the three “gesima” Sundays that preceded Ash Wednesday.

O God, whose blessed Son was manifested that he might destroy the works of the devil and make us the children of God and heirs of eternal life: Grant us, we beseech thee, that, having this hope, we may purify ourselves even as he is pure; that, when he shall appear again with power and great glory, we may be made like unto him in his eternal and glorious kingdom.(The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 184)

This collect draws on several verses. The most obvious is the quotation at the beginning from 1 Jn. 3.8, “For this purpose the Son of God was manifested, that he might destroy the works of the devil.” But it also draws from the phrase “heirs of eternal life” from Tit. 3.7 (“we should be made heirs according to the hope of eternal life”; KJV); the reference to purification returns to 1 Jn. 3, first verse 3: “And every man that hath this hope in him purifieth himself, even as he is pure,” and then from verse 2: “we know that, when he shall appear, we shall be like him” (all KJV).

Quotations are often the easiest of the uses to identify and source.

2.5. Appropriation

One final category remains. While they may appear to be identical to Quotations, Appropriations turn out to be clearly distinct. This use is the complete transformation of part of Scripture into a liturgical unit. A portion of Scripture is not simply quoted within a larger composition. Rather, Scripture becomes the liturgical text. This can occur, however, in several different ways.

The most repeated example is the Lord’s Prayer. (Cross and Livingstone 2005, p. 996; Stevenson 2004; Freedman 1992, pp. 356–62). Matthew and Luke both give versions (Mt. 6.9-13; Lk. 11.2-4) and it is the Matthean version that becomes the normative basis for its liturgical use by the close of the first century. Didache 8 directs Christians to fast on Wednesday and Fridays and to say the Our Father three times a day, at the three hours of prayer. The prayer is quoted in the Matthean version with the doxology to which we are accustomed. Almost all Christian liturgical prayer appears to include the Lord’s Prayer, which seems to be a response to how Jesus introduces the prayer in Luke’s Gospel: in response to the question, “Lord, teach us to pray,” Jesus replies, “When you pray, say” this (11.1-2). There are no public liturgies in the 1979 BCP that do not have the Lord’s Prayer in it, except for the “Thanksgiving for the Birth of a Child,” but this is only because the rite presumes that it will be normally incorporated into either Morning Prayer or the Eucharist (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 439).16 Beyond the Lord’s Prayer, there are a couple of subcategories of Appropriation that can be clearly distinguished and a number of these mark the Divine Office, whose fixed text has more direct appropriation of Scripture than any other type of Christian liturgical rite.

The first type of Appropriation is when whole chapters—or, at least, lengthy sections of a passage—are fixed into a rite. One of the earliest of these uses is the daily use of Ps. 95[96] at the first office of the day in Chapter 9 of the Rule of St. Benedict, a practice which Cranmer retained in the BCP office of Matins or Morning Prayer (no doubt a response to the sermon on this psalm in the first few chapters of the Epistle to the Hebrews). Similar to this was the fixing of psalms that were appropriate to the times of day, such as Ps. 141 in the evening: “Let my prayer be set forth in your sight as incense, * the lifting up of my hands as the evening sacrifice.” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 797). In the 1979 BCP, the Offices of Noonday Prayer, whose structure broadly reflects the little monastic hours of Terce, Sext, and None, as well as Compline both feature the fixed use of Psalmody: 119.105-12; 121.1-8; and 136.1-7 at the former and 4.1-8; 31.1-5; and 91.1-16 at the latter (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, pp. 103–5; 129–31).17 A practice that developed somewhat later, according to Bradshaw, is the appropriation of portions of Scripture outside the Psalter and which are already hymnic in nature, often called canticles: the Benedictus Dominus Deus, Zechariah’s song from Lk. 1.68-79, at the morning office; the Magnificat, the song of the Blessed Virgin from Lk. 1.46-55 at Vespers (or, in the BCP tradition, Evensong); the Nunc Dimittis, the Song of Simeon from Lk. 2.29-32 at Compline (Bradshaw 1992, pp. 35–52).

In the Office, as in the Mass, a basic principle is in operation: when Scripture is read or proclaimed, Christians respond to Scriptures in the words of Scripture (the use of the Te Deum and the Gloria in excelsis in the Offices are obvious exceptions). Scripture is not proclaimed without a response: in the Offices, the responses are called Canticles; in the Mass, the response to the Epistle was the Gradual, which was a portion of the Psalter, plus a brief text with an Alleluia antiphon in preparation for the Gospel (the only reading that does not have a response, save for the homily). In the post-reformation period, particularly in the last few centuries, these responses of Scripture come to be replaced by hymnody. This is especially true in the BCP’s Communion liturgy, where all the Minor propers disappear; in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, hymns are often used in these locations.

There are other, later examples of this sort of appropriation that are not found in the BCP liturgies. For example, the Benedicite Omnia Opera, from the Song of the Three Young Men (which was a canticle at Morning Prayer), began to be recited by the priest in the Roman Rite during his recession after the Mass18 (Bradshaw 1992, p. 46). Later, in the tenth century, Ps. 43[42] was introduced into the beginning of the Latin Mass into the so-called “prayers at the foot of the altar”: “I will go unto the Altar of God, even unto the God of my joy and gladness.”19 Similarly, the recitation of Ps. 26 became incorporated in the silent prayers said by the Priest during the offertory as the hands are washed:

Here, a large portion of text is made into a liturgical unit.I will wash my hands in innocence, O Lord, *that I may go in procession round your altar,Singing aloud a song of thanksgiving *and recounting all your wonderful deeds(The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 616).20

A different kind of Appropriation is when a verse from Scripture—almost always a Psalm—is transformed into a versicle and response, which is a short petition begun by the officiant, to which a response is provided by the congregation or choir (Cross and Livingstone 2005, “Versicle”, p. 1689). The opening versicle and response at the first night office, “Lord, open thou our lips/And our mouth shall show forth thy praise,” is appropriated completely from Ps. 51.15. Cranmer incorporated this not only at the beginning of Matins, but interestingly at Evensong as well. Similarly, the versicle and response that said at the opening of all the offices in the Latin rite, “O God, make speed to save us/O Lord, make haste to help us,” is taken directly from Ps. 70.1[69.2]. Cranmer keeps these also in his two offices.21 Another common versicle and response in the Latin office tradition, “Domine, exaudi orationem meam; * et clamor meus ad te veniat,” comes directly from Ps. 102.2. Similarly, after the Lord’s Prayer in Morning and Evening Prayer, the BCP Offices contain what the book properly calls “Suffrages.” Their origin is from litanies of intercessions in the Frankish and Gallican tradition that were imported into the Latin breviary, but were then replaced by capitella or suffrages, which are “psalm verses which were used both for petition and response.” (Cross and Livingstone 2005, “Intercession” p. 255; “Suffrages”, p. 451). In Cranmer’s offices, the same set of suffrages was used at both Morning and Evening Prayer, drawn primarily from the office of Prime in the Sarum breviary, each of which are psalm verses just as in the medieval practice.22

Then the Priest standing up shall say,

| O Lord, shew thy mercy upon us. | |

| Answer. | And grant us thy salvation. [Ps. 85.7] |

| Priest. | O Lord, save the Queen. |

| Answer. | And mercifully hear us when we call upon thee. |

| [adapted from Ps. 20.923] | |

| Priest. | Endue thy Ministers with righteousness. |

| Answer. | And make thy chosen people joyful. [Ps. 132.9] |

| Priest. | O Lord, save thy people. |

| Answer. | And bless thine inheritance. [Ps. 28.11] |

| Priest. | Give peace in our time, O Lord. |

| Answer. | Because there is none other that fighteth for us, |

| … | but only thou, O God. [Ps. 122.7] |

| Priest. | O God, make clean our hearts within us. |

| Answer. | And take not thy Holy Spirit from us. [Ps. 51.11a and 12b] |

These suffrages are retained in the 1979 revision as the first option in both Morning and Evening Prayer, though in a slightly revised form that dates to the 1892 BCP.24 A similar set of suffrages was appended quite early in the medieval period to the fourth-century hymn known as the Te Deum and follows the pattern of complete psalm sentences arranged as versicles and responses.25 The English BCPs retained the Te Deum with these appended suffrages. The 1979 BCP removes those suffrages from the end of the Te Deum in Morning Prayer in both Rite I and Rite II but transfers them to be the second option for suffrages in Morning Prayer. In all these instances, the fact that the text of Scripture has simply been appropriated and become a liturgical text often obscures to the participant the source material, whereas the Scriptural origin of the fixed canticles or psalmody are much more obvious.

The 1979 BCP introduces a new set of versicles and responses in the revised baptism rite, which are to be said before “the Lord be with you” that introduces the collect of the day:

| Celebrant | There is one Body and one Spirit; |

| People | There is one hope in God’s call to us; |

| Celebrant | One Lord, one Faith, one Baptism; |

| People | One God and Father of all. (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 299). |

Like in traditional versicles and responses, a biblical text is placed into the recognizable format. The main difference is that the source is not the Psalter but the New Testament, Eph. 4.4-6a, in this case. In this set of examples, a whole category of liturgical construction—the versicle and response—is marked most of the time by being the direct appropriation of a verse from the psalms.26

There are still other ways that verses from Scripture are appropriated into liturgical rites and become liturgical text. Similarly to the fixed use of particular psalms at particular times of day, the capitulum or “Little Chapter” was an invariable (except for the season) verse of Scripture that was also a fixture in the Latin breviary (Cross and Livingstone 2005, “Chapter, Little”, p. 320). This again is found in Noonday Prayer where three “Little Chapters” are given as options (Rom. 5.5; 2 Cor. 5.17-18; and Mal. 1.11) as well as at Compline: (Jer. 14.9, 22; Mt. 11.28-30; Heb. 13.20-21), plus “Be sober, be watchful. Your adversary the devil prowls around like a roaring lion…” from 1 Pet. 5.8-9a, a text that was often fixed at the very opening of Compline in the Latin rite, just before the Confession. Reformation liturgies began adding instances like this. In the 1552 revision, Cranmer added a General Confession to the beginning of Morning and Evening Prayer and introduced it with 11 sentences from Scripture, “eight from the Old Testament and three from the new, all of a penitential character” (Hatchett 1980, p. 91). Interestingly, these have their origin in the “Little Chapters” there were appointed in the medieval office during Lent, or from the traditional penitential psalms27 (Hatchett 1980, p. 91). The American BCPs began to expand the options in these sentences in order to strike not just penitential notes but also point to the season or feast day. The English BCPs kept the Offertory sentence, but in an altered form. Instead of it being one of the minor propers, Cranmer provided a list of options from which the priest chose. His original list was focused on giving of alms to the poor. Anglicanism slowly began to re-receive the oblationary and sacrificial character of the Eucharist such that by the 1928 American Book, the theological themes have expanded to include the idea of offering something to God as an act of praise and thanksgiving (Bradshaw 2002, “Offertory”, p. 338).

Another instance of Appropriation that is a hallmark of the Anglican office is the fixing of what is often called “The Grace” at the end of Matins and Evensong, 2 Cor. 13.14: “The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the love of God, and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit, be with us all evermore.” It was first introduced in the BCP of Elizabeth I in 1559, both to the end of the Litany and the Offices (Bradshaw 2002, “Grace”, p. 232; Hatchett 1980, pp. 131–32). As Hatchett puts it, “the Grace has served both as a final trinitarian doxology and as a prayer for the principal gifts of the Three Persons of the Trinity” (Hatchett 1980, p. 132). This same verse replaces the simple salutation of the Latin rite (“The Lord be with you/and with your spirit”) at the opening of the Eucharistic prayer in some of the Eastern rites, such as in Anaphora of Sts. Addai and Mari and Anaphora of St. James.28 The rite for Ash Wednesday contains a rather unique example of appropriation. As ashes are administered on the forehead of the faithful, the minister repeats the concluding words of the curse given to Adam for the primordial sin in Gen. 3.19: “You are dust, and to dust you shall return”29 (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 265).

All uses of Appropriation should be distinguished from the reading of Scripture in the Mass or Office according to a lectionary. This is not only because psalm texts are never “proclaimed” as lessons but also because they are not presented in the rite as Scripture to be proclaimed for our edification. Rather, Scripture is put on our lips as liturgical prayer or expression. Thomas Merton puts it beautifully: “The Psalms are not only the revealed word of God” but they are also “the words which God Himself has indicated to be those which He likes to hear from us” (Merton 1956, p. 8). This could be said, of course, for much of the rest of the Scriptures.

2.6. The Five Possible Sub-Categories

2.6.1. Subcategory 1: Therefore

The first of these subcategories is what I call a Therefore use, which is when a rite either alludes to or quotes Scripture within a context that indicates that what is happening is a response to a divine command given in Scripture. The introduction to Lord’s Prayer often indicates this. In the Roman Rite, the language has been and remains quite stark: “At the Savior’s command and formed by divine teaching, we dare to say, ‘Our Father…’” (The Roman Missal 2011, p. 663). Cranmer’s version was quite similar: “As our Saviour Christe hath commaunded and taught us, we are bolde to saye” (Cummings 2013, p. 32). A Therefore usage, in other words, assumes an institution. These uses can often be further qualified as a strong or weak.

While it seems that eucharistic prayers probably did not contain institution narratives until the third or fourth century, by the end of the fourth century, the vast majority of them contain a recounting of the last supper and Christ’s institution of the memorial, often an amalgamation of two or more of the five narratives found in the New Testament (1 Cor. 11.23-25; Mt. 26.26-29; Mk. 14.22-25; Lk. 22.15-20; Jn. 13-17). This is one of the strongest examples of a Therefore use. Some have puzzled whether the narratives entered the liturgy for pedagogical purposes. With the huge influx of converts after the legality of Christianity was guaranteed through the Edict of Milan in 313, the theory is that it made sense to introduce an explanation and warrant for the action taking place for those who were new and poorly formed.30 However, the evidence seems to be that most anaphoras were not audible to the congregation starting in the fourth and fifth centuries, will raises questions about this theory. Until revisions in the twentieth century, most institution narratives were situated within subordinate clauses, which means that it is often easy to see how the prayer would have looked without the institution narrative. In the Roman Canon, for instance, the narrative is introduced with the coordinating conjunction qui (who) (See Serra 2003, pp. 99–128):

The main request is for the Father to make the offering acceptable so that it would become Christ’s Body and Blood, and the institution narrative functions to clarify who this Jesus is. Cranmer places the narrative in the same grammatical situation in 1549:O God, we beseech you to make in every respect blessed, approved, ratified, spiritual (reasonable) and acceptable, so that it may become for us the Body and Blood of your most beloved Son, Jesus Christ our Lord, who, on the day before he suffered, took bread in his holy and venerable hands.

Even Rite I, Prayer I retains this by introducing the narrative with the word “for,” used not as a proposition, but in its older, and now much less common usage, as a conjunction: “…and in his holy Gospel command us to continue, a perpetual memory of that his precious death and sacrifice, until his coming again. For in the night in which he was betrayed, he took bread…” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 334). The point is that in the institution narrative, a biblical text is being quoted (or we should say more accurately, paraphrased) in order to provide the warrant for the current action. We are doing this because, on the night Jesus was betrayed, he took bread. Therefore uses of Scripture assume a Scriptural institution. Some modern eucharistic prayers express the “therefore” that often follows the institution narrative (the Unde et memores in the Roman Canon) in ways which disguise this, such as “And so, Father, calling to mind…” in Prayer B of Common Worship (Church of England 2000, p. 190) or “We now obey your Son’s command” in Eucharistic Prayer I of the Scottish Liturgy (Scottish Episcopal Church 2022, p. 9).Heare us (o merciful father) we besech thee: and with thy holy spirite and worde, vouchsafe to blesse and sanctifie these thy gyftes, and creatures of bread and wyne, that they maie be unto us the bodye and bloude of thy moste derely beloved sonne Jesus Christe. Who in the same nyght that he was betrayed: tooke breade….(Cummings 2013, pp. 30–31)

It turns out that the Therefore use is rather common in liturgies for many of the sacraments. They are often at pains to communicate that we are undertaking this rite not at our own initiative, but because we are commanded to do so, or because its origin is a divine directive. The current American BCP does not provide an explicit indication of institution for Baptism within the rite itself, though the six Scriptural allusions that I discussed earlier are more oblique versions of an appeal to divine institution: in other words, it is talked about all throughout the New Testament; therefore, it was instituted by God. None of the Gospel lessons for a baptism include the dominical institution at the end of Matthew 28, but this is probably because the baptismal formula itself embeds the dominical direction found there. The current Roman Rite, on the other hand, lists many ancient, divine actions as the basis for baptism and blessing the water, which concludes, “After his resurrection he told his disciples, “Go out and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”31

A few more examples are worthwhile. In the 1928 American BCP, after the candidates are presented to the bishop for Confirmation, Acts 8.14-16 was read, which describes when Peter and John came to Samaria and learned that those who had been baptized “in the name of the Lord Jesus” had not received the Holy Spirit, “the apostles laid their hands on them and they received the Holy Spirit,” thus making apostolic practice serve as the Scriptural authority for the practice. (The Book of Common Prayer 1928, p. 296). 32 I noted earlier the way the Exhortation at the opening of the Marriage rite makes an appeal to Scripture as a basis for its institution. Note how that appeal includes an explicit appeal to natural law in the claim, “The bond and covenant of marriage was established by God in creation” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 423). Further, in the rite for the reconciliation of a penitent, the absolution begins with a Scriptural warrant: “Our Lord Jesus Christ, who has left power to his Church to absolve all sinners who truly repent and believe in him, of his great mercy forgive you all your offenses; and by his authority committed to me, I absolve you from all your sins: In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 448). The Scriptural source is almost certainly the post-resurrection appearance of Jesus to the apostles at the conclusion of John’s Gospel, where he breathes on them and says “Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained” (Jn. 20.22b-23). Recall that the central formula for the ordination of a priest in the English ordinal, and then in the American one until the 1979 revision, is a direct appeal to this verse and situates the priesthood on the apostolic ministry regarding the forgiveness of sin: “Receive the Holy Ghost for the Office and Work of a Priest in the Church of God, now committed unto thee by the Imposition of our hands. Whose sins thou dost forgive, they are forgiven; and whose sins thou dost retain, they are retained. And be thou a faithful Dispenser of the Word of God, and of his holy Sacraments; In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost” (The Book of Common Prayer 1928, p. 546).

The central ritual actions for Christians in which the Church teaches that Christians can be assured of God’s gracious action can make this audacious claim, not on the basis of the ritual, but based on divine institution. The rites themselves nearly always provide this scriptural warrant within the prayers. These are the Therefore uses.

2.6.2. Subcategory 2: Pattern

The second subcategory is a Pattern use, which is the appeal of a ritual text to the past as a warrant for the particular manner or the actual request in the present. Sometimes this appeal is to a pattern of divine action, which serves as a basis for asking God to act in the same way now as he did in the past. Other times, the appeal is simply to a pattern of previous ways of praying that the rite assumes is an authoritative pattern for the present liturgical petition. In other words, this sort of praying assumes both a consistency to God’s action as well as the importance of praying in continuity with one’s religious forbearers.

Probably the most common experience of the Pattern use is in the collect form, which is used in all public liturgies. Western liturgy has the Pattern use imbedded in its fundamental structure. It begins by invoking God in some manner (“Almighty God,” “Merciful God,” “Most loving Father”), followed by “the reason why God should hear and answer the prayer” (Bradshaw 2002, “Collect”, p. 119). The reason is often an aspect of the divine nature or a past action of God. The aspect of God, or an example of past action, serves as the basis for the request that follows, the third part of a collect. The petition traditionally bears a relationship to the characteristic or past action of God, which creates a clear thematic unity to the collect. Finally (as I already mentioned), collects conclude at least with a prepositional phrase that is usually either “through Christ our Lord” or “through Jesus Christ our Lord” and then the longer trinitarian conclusion.

An ancient collect for the nativity of Christ splendidly exemplifies this pattern: “O God, who wonderfully created the dignity of human nature and still more wonderfully restored it, grant, we pray, that we may share in the divinity of Christ, who humbled himself to share in our humanity.”33 The God who is addressed is identified by not just one, but by two past actions: the creation of a human nature that is endowed with dignity and also has the restoration of that dignity, which presumably was lost or tarnished at some point. The petition that follows is directly connected to these divine activities: the request is that those present at the liturgy may share in the divine life of Christ, the one who both created human nature and acted to restore it through his incarnation and the paschal mystery. Thus, the predominant variable prayer of the Mass in the Western liturgy, as well as the daily office in all Anglican BCPs, are structured precisely according to this Pattern use.

Patterns are found in many different Christian liturgical forms, as Baumstark points out.34 In the Ministration to the Sick, not only is the classic passage from James 5 (“Is any among you sick?”) provided as an optional reading, the collect for the blessing of the Oil of the Sick also makes a Pattern appeal: “O Lord, holy Father, giver of health and salvation: Send your Holy Spirit to sanctify this oil; that, as your holy apostles anointed many that were sick and healed them, so may those who in faith and repentance receive this holy unction be made whole” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 455). The logic is straightforward: the Holy Spirit is asked to act upon the oil so that its function now in anointing those who were sick might be the same as when the apostles anointed the sick and healed them. In the older Roman Rite for the Commending of a Soul at Death, there is a litanal form with the repeated formula, “Deliver, O Lord…as you delivered [name] in the past.” For example, “Deliver, O Lord, the soul of your servant, as you delivered Enoch and Elijah from the death all must die.” One of the repeated constructions in exorcism prayers is quite similar with the repetition of the phrase, “Yield to God, who [and here is inserted an event in the Scripture]. For example, “Yield to God, who, by the singing of holy canticles on the part of David, His faithful servant, banished you [evil spirit] from the heart of King Saul.” (Rituale Romanum Pauli V 1834, pp. 108–9, 295–96).

An important example of Pattern is also one of the distinguishing features of the Roman Canon. Near the end, the divine acceptance of the three historical sacrifices of Abel, Abraham, and Melchizedek functions as the basis for the request that God accept the offering of the eucharistic sacrifice.35

The causal connection between the acceptance of the ancient sacrifices and the request that God favor and accept the sacrifice of those making an offering in the present is indicated by the adverb sicuti (just as). The appeal is not primarily to the act of offering undertaken by Abel, Abraham, and Melchizedech. Rather, the appeal is to God’s acceptance of those sacrifices. One of the most noteworthy aspects of this example is that the appeal is not to one or two particular passages, but to a whole collection of them, both the set of passages in Genesis that describe each of these sacrifices plus the mention of these events throughout the New Testament, especially in Hebrews. This example from the Roman Canon highlights a connection that is often seen between Pattern uses of Scripture and a characteristic I call “Explication,” which I discuss near the end.Upon these sacrifices, be pleased to look with a favorable and kindly countenance, and to accept them as you were pleased to accept the dutiful offerings of your righteous servant Abel, and the sacrifice of our patriarch Abraham, and that which your high priest Melchizedek offered to you, a holy sacrifice, a spotless sacrificial offering.

A distinctive feature of the 1549 eucharistic prayer, as well as those in the Scottish and American prayer book traditions (which differ in some significant ways from the English one), stands uniquely amongst post-reformation prayers with the repeated request for acceptance, following the practice of the Roman Canon. The second request in 1549 is modeled directly on the Roman Canon, as we can see in Table 2.

Table 2.

Roman Canon and 1549 BCP.

One of the changes that Cranmer makes is to remove the Pattern use and thus not make an appeal to God’s acceptance of the ancient sacrifices as a basis for the request for the acceptance of our prayers. The reason for this is likely because he wished to express a very different notion of sacrifice as it concerns the celebration of Holy Communion. While the Latin tradition understands that the material offering of bread and wine is one constitutive feature of the celebration of the Eucharist, Cranmer speaks of sacrifice in only three ways in the prayer book eucharistic prayers: the historical sacrifice of Christ on the cross; the self-offering of those present; and the offering of verbal praise.

2.6.3. Subcategory 3: Imitation

The third subcategory is Imitation, which is when an Allusion or a Quotation is used as an appeal to a Biblical action as the basis for a similar bodily action within a liturgical rite. Imitation springs from a human desire to make possible a ritual experience of a specific biblical event. However, it differs in a critical way from the Therefore because it is not based on a divine command in the Scriptures (unlike what is often found in the rites for sacrament); and Imitation is also distinguished from the Pattern use because the Pattern does not appeal to a past human action (outside of prayer) in the Bible, but to a way the God has acted or the faithful people have prayed in the past. One of the changes that Cranmer makes is to remove the Pattern use and thus not make an appeal to God’s acceptance of the ancient sacrifices as a basis for the request for acceptance here, no doubt because he wished to express a very different notion of sacrifice as it concerns the celebration of Holy Communion.

Imitation uses were often the object of reform and deletion in the sixteenth-century, though some were restored in the current American book, and these are seen especially in the Proper Liturgies for Special Days (pp. 264–95). The 40-day fast of Lent36 is clearly conceived as an imitation of Christ’s forty-day fast at the beginning of his ministry (Mt. 4.2; Mk. 1.13; Lk. 4.2). In parts of Egypt, the Imitation was more literal, and the forty-day fast began directly following the Epiphany and the celebration of his baptism (Bradshaw 2002, pp. 35–52). The use of ashes as “a sign of our mortality and penitence,” is based not just on the fact that we are created from the dust (see Gen. 2.7 and 3.19) but also the repeated use of ashes as a sign of penitence throughout the Old Testament (2 Sam. 13.19; Est. 4.1, 3; Job 2.8; Isa. 58.5; even the divine injunction in Jer 6.26). The carrying of palms while singing “All glory laud and honor” and or Ps. 118.19-29 (p. 271) is a conscious imitation of a few key aspects of our Lord’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem at the beginning of the week of his Passion (see Mt. 21.1-11; Mk. 11.1-11; Lk. 19.28-44; Jn. 12.12-19). The Footwashing on Maundy Thursday is an imitation of Christ’s washing the feet of his disciples (Jn. 13.1-20), especially the way that it has been undertaken in the Roman Rite for about 800 years. The kindling of a fire “in the darkness” followed by the lighting of the Paschal Candle “from the newly kindled fire” that is then processed into the church at the beginning of the Easter Vigil is a ritual expression of the prophetic word of Isa. 9.2 (“the people who walked in darkness have seen a great light”) and the strong theme of Jesus as the light in John’s Gospel (1.5; 8.12; 12.35, 46).37 The rhetorical structure of the Exsultet echoes later Jewish Passover ritual prayer (“This is the night…”), whose institution is given in Exodus 12. The Exsultet reads the Passover by way of the Pauline interpretation of Christ as “our paschal lamb” (1 Cor. 5.7).

There are other Imitation uses outside the BCP tradition. Not surprisingly, these are the types of liturgical actions that fell victim to sixteenth-century reforms. A good example of this is the Apertio or Effeta, where spittle was used on the ears and lips as part of a pre-baptismal rite (in imitation of Jesus’ healing of the deaf mute in Mk. 7.32-5) (Bradshaw 2002, pp. 35–52). An image of this is burned into many of our heads from the first Godfather film, when Coppola cuts back and forth between Michael in church as his child is baptized in the older Roman Rite and the execution of the murders he has just ordered.

The Imitation use is when a biblical event is taken up as a model for a ritual action, but where the biblical source is not interpreted a specific “institution” of the ritual action.

2.6.4. Subcategory 4: Composite

Allusions, Quotations, and Appropriations can all be modified as Composite uses, which is when two or more portions of Scripture are combined within a fixed liturgical text. The most common example of this is the institution narratives in eucharistic prayers. Interestingly, until the Reformation, there are almost no examples of an institution narrative that directly quotes one of the last supper narratives from either 1 Corinthians or the Synoptic Gospels. Instead, they are always an amalgamation of two or more of them, sometimes with additional text thrown in as well (as I mentioned earlier in the Roman Canon, where the adjective “eternal” is added to the phrase “new covenant” and the phrase “mystery of faith” is inserted from 1 Tim. 3.9). An even more common example of a Composite quotation is the Lord’s Prayer, which began to be used before the end of the first century, as Didache 8.2 demonstrates. There, two portions of Scripture are combined to make a fixed liturgical text (Mt. 6.9-13 and 1 Chron. 29.11). Two of the fixed, choral chants in the Mass and which are retained in the BCP tradition are examples of Composite Quotations: the Sanctus and Benedictus combine a quotation of Isa. 6.1-3 with the acclamation of the people to Jesus as he triumphally enters Jerusalem in Mt. 21.9.

Holy, holy, holy Lord, God of power and might,

heaven and earth are full of your glory.

Hosanna in the highest. [Isa. 6.1-3; cf. Rev. 4.8]

Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.

Hosanna in the highest. [Mt. 21.9]

Similarly, the Agnus Dei combines a repeated quotation of John the Baptist about Jesus from Jn. 1.2938 with the repeated refrain, “have mercy upon us,” which itself is a petition directed as Jesus that is repeated throughout the Gospel:

Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world:have mercy on us.Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world:have mercy on us.Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world:grant us peace.

The Offices contain several Composite Appropriations. The variation of the Venite that was introduced in the first American BCP is a key example. There, verses 8–11 of the psalm were excised and replaced with verses 9 and 13 from Ps. 96, but put together to appear as if they are one composition.39 Also in the Invitatory of Morning Prayer, the anthem “Christ our Passover” is a Composite Appropriation of 1 Cor. 5.7-8, Rom. 6.9-11, and 1 Cor. 15.20-22 (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, pp. 46, 83).

Composite Appropriation is quite common in the Mass of the Roman Rite, in what are known as the minor propers or variable chants of the Mass (introit, gradual, alleluia or tract, offertory, and communion).40 The first of the “Little Chapters” in Compline is a combination of Jer. 14.9b and 14.21a (though the BCP lists it as 14.22).41 The portion from Ps. 51 for the Morning in Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families are presented as a unit but is, in fact, Ps. 51.16, 11-13. Also in Daily Devotion, the Reading At Noon is a combination of Isa. 26.3 and 30.15b (and in a new translation, not from the RSV).

Like the opening of the Marriage rite, another feature of the BCP tradition that is known well beyond the average churchgoer is the anthems in the burial office. The opening anthem begins, “I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord.” Since the 1549 book, the service begins with three brief anthems, all of which are passages of Scripture and all of which remained unchanged through the 1928 American book (see the discussion in Hatchett 1980, p. 485): Jn. 11.25-26; Job 19.25-27; and 1 Tim. 6.7 and Job 1.21b. The BCPs texts of these texts do not match either of the English source Bibles: until 1662, the source was the Great Bible, after which they switched to the King James Bible. Even then, the BCP alters the texts slightly: “saith the Lord” is added to the John passage and Job 19.25 begins in 1549 “I know that my redeemer liveth,” even though the Great Bible reads “For I am sure that my redeemer lyueth” (the KJV would follow the BCP in their translation). The likely reason for these differences is that they both had sources in the Sarum rite and so it is probable that Cranmer is translating from them, rather than looking to an English translation of the Bible. The final anthem, which was Cranmer’s own creation, is a Composite Appropriation and adheres more strictly to the English Bible (first to the Great Bible, and then in the 1662 BCP, to the King James Version). The third anthem, however, is removed in the 1979 revision and replaced with two others: Rom. 14.7-8 (KJV in Rite I and what appears to be an original translation in Rite II) and Rev. 14.13. The latter text was used in both Sarum and in the earlier BCPs through the 1928 American book as an anthem after the committal at the graveside and was moved from there to this location at the opening of the liturgy.

There were similar anthems that were used at the graveside, titled the Committal in the 1979 BCP: Job 14.1-2 (“Man that is born of woman…”) followed by a famous anthem (“In the midst of life we are in death”) which is not Scriptural but which appears to date to the ninth century and the pen of Notker the Stammerer, a monk of St. Gall in Switzerland (d. 912). Until 1662, the Burial Office assumes that the anthems from the previous paragraph were used for the procession to the graveside and that then the entire service would be conducted there. In 1662, however, the rite is altered. The body is born into the Church with the aforementioned anthems, after which two psalms and a lesson from 1 Cor. 15 are to be read. Only then are the verses from Job 14 and the anthem used, “when they come to the grave, while the corps is made ready to be laid into the earth.”42 The 1928 American book added two prayers to conclude the service in the church and then follows the English order of beginning the graveside with this second anthem, a variation of the Composite Appropriation. Here, a biblical text is combined with a non-biblical text in such a way that it is quite likely that many will assume that the entire unit is Scriptural. This second anthem is provided as a second option for the opening anthem in Rite II, but with two alterations that restore it to the form of its original composition: the opening verse from Job are cut and each line is interspersed with the Trisagion (See Hatchett 1980, p. 485). This anthem (minus the verses from Job) is also provided in Rite I as the first of two anthem options at the Committal. The second option (which begins, “All that the Father giveth me”) originates in the 1928 American book and is a Composite Appropriation of Jn. 6.37, Rom. 8.11, and Ps. 16.9 and 11. In Rite II, the rubric permit either of the two anthems provided at the opening of the Burial Office, plus a contemporary version of this new Composite anthem.

The Composite character of a Quotation or Appropriation can thus either be entirely Scriptural or, in some instances, the fusion of a Biblical text with a text from another source. Both types create the sense that the collation is a single unit, despite its composite source.

2.6.5. Subcategory 5: Amended

The last subcategory are Amendments, which can occur with both Quotations and Appropriations. An Amendment is when something in the original text is altered, either by substitution or insertion, but without obscuring the source of the biblical quotation. One example with which users of the 1979 BCP are most familiar is the new fraction anthem that was introduced in both Rite I and Rite II. This text is not a completely new innovation but is based on an anthem that Cranmer composed for the first BCP of 1549, which did not survive the revision in 1552 and disappeared for over 300 years:43 “[Alleluia.] Christ our Passover is sacrificed for us; Therefore let us keep the feast. [Alleluia.]” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, pp. 337–64). In this instance a brief passage from 1 Corinthians 5 is Quoted and then Amended. The original text is this: “For Christ, our paschal lamb, has been sacrificed. Let us, therefore, celebrate the festival, not with the old leaven, the leaven of malice and evil, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth” (1 Cor. 5.7b-8). The quotation is actually amended in more than one way. Instead of Christ described as “our Passover lamb,” he is simply “our Passover.” But maybe more significant is the amendment of the verb tense. In I Cor. 5.7, the verb thúo, which means “to sacrifice or immolate” is in the third person, passive verb in the Aorist tense. The immediate context of 1 Corinthians 5 does not seem to be eucharistic and it refers to Christ’s sacrifice on the cross as a past event. But, changing the verb sense to the present, active—“Christ our Passover is sacrificed for us”—the rite is expressing in a more literal way the sort of anamnesis (a rich sense of remembering) that Christians have assumed takes place in the Eucharist. In other words, “Christ our Passover is sacrificed for us” is a claim that the past, once-for-all sacrifice is made present in the Christian Eucharist’s sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving, a response to Christ’s institution and command to “do this.”44

The Offices also contain several examples of Amended Appropriations. Two alternatives to “The Grace” (2 Cor. 13.14; first printed as a conclusion to the Litany and both Offices in 1559) are given at both Morning and Evening Prayer. The first is listed as Rom. 15.13, though it has been amended slightly:

| Rom. 15.13, RSV | 1979 BCP (pp. 60, 73, 102, 126) |

| May the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing, so that by the power of the Holy Spirit you may abound in hope. | May the God of hope fill us with all joy and peace in believing through the power of the Holy Spirit |

The third option alters the text enough that it could arguably be categorized as an Allusion:

| Eph. 3.20-21, RSV | 1979 BCP (pp. 60, 73, 102, 126) |

| Now to him who by the power at work within us is able to do far more abundantly than all that we ask or think, to him be glory in the church and in Christ Jesus to all generations, for ever and ever. Amen. | Glory to God whose power, working in us, can do infinitely more than we can ask or imagine: Glory to him from generation to generation in the Church, and in Christ Jesus for ever and ever. Amen. |

While Hatchett does not indicate one way or another, it is possible that both of these are new translations of the Greek by members of the committee, which could explain the differences.45 He does explain that Canticle 9: The First Song of Isaiah (Isa. 12.2-6) is a translation by Charles M. Guilbert, which explains why they differ from the RSV. In fact, in the Rite II morning office, Guilbert translated the following, all of which are new to the 1979 BCP (except for the Song of Simeon): Canticle 8: The Song of Moses (Exod. 15.1-6, 11-13, 17-18), Canticle 10: The Second Song of Isaiah (Isa. 55.6-11), Canticle 11: The Third Song of Isaiah (Isa. 60.1-3, 11a, 14c, 18-19), Canticle 12: A Song of Creation (Song of the Three Young Men, 35-65), Canticle 13. A Song of Praise (Song of the Three Young Men, 29-34), Canticle 14: A Song of Penitence (Prayer of Manasseh, 1-2, 4, 6-7, 11-15), Canticle 17: The Song of Simeon (Lk. 2.29-32), Canticle 18: A Song to the Lamb (Rev. 4.11; 5.9-10, 13), and Canticle 19: The Song of the Redeemed (Rev. 15.3-4). As is apparent, a number of these canticles (8, 11, 14, 18, and 19) are Amended Appropriations because they remove particular verses from a passage and arranged it together so that it appears to be a single unit. The one responsory to remain in the BCP tradition (and the only one in the 1979 BCP) is found at the end of the Litany, listed in the 1979 BCP under the title “The Supplication.”46 While the structure varied somewhat depending on the diocese or monastic use, a common pattern for a responsory is “refrain; psalm verse; part of refrain; first half of the Gloria Patri; whole or part of refrain” (Harper 1991, “Responsory or Respond”, p. 407). In this case, the pattern is Ps. 44.26; Pss. 44.1; 44.26; entire Gloria Patri; Ps. 44.26.47 This turns out to be both an Amended and a Composite Appropriation: amended because Ps. 44.1 has been altered, and composite because two non-sequential verses are arranged together in this unit.

Like Composite Appropriations, Amended Appropriations are also common in the minor propers of the Roman Rite, sometimes in a way that is unimaginable in the Anglican Prayer Book tradition. For example, the Gradual and Alleluia for the Immaculate Conception (8 September) in the Roman missal serves as an example of just the type of liturgical construction that raised the ire of sixteenth-century reformers. The appointed Gradual Appropriates Jud. 13.18 but inserts the Virgin’s name in the midst of the text, and then combines it with Jud. 15.9: “Blessed art thou, O Virgin Mary, by the Lord most high God, above all women upon earth” (13.10); thou art the exaltation of Jerusalem, thou art the great glory of Israel, thou art the honor of our people (15.9).” By inserting Mary’s name, the Appropriation of this biblical verse is given an allegorical interpretation. The proper Alleluia does the same thing: it quotes the first part of Song 4.1, inserts Mary’s name, and then adds a dogmatic claim that is not a quotation of Scripture concerning the feast: “Thou art all fair, O Mary, and there is in thee no stain of original sin.” Analogous to the variable chants of the Mass are the antiphons appointed for Sundays and feasts to be used with the psalms and canticles in the Divine Office, which can evidence these same sorts of variations on Appropriation. The examples of this usage much rarer in the BCP tradition but remain common in the minor propers of the Roman Rite.48

2.6.6. Three Possible Characteristics

All of the uses that I have discussed thus far can also be marked or characterized by several additional features: Explication, Name and Locations, and Juxtaposition. It turns out that all of these have appeared in the examples used thus far, and so I will return to some of them in order to provide an even fuller picture of how biblical texts can be appropriated into liturgies.

Characteristic 1: Explication

The first of these three characteristics is what I called Explication, and this can be seen in both Allusions and Quotations, and their various subcategories. Explication is when one or more texts are interpreted and used in light of other parts of the biblical canon, often moving seamlessly between the Old and New Testaments, and often producing a theological conclusion (though the exegesis does not necessarily connect Old Testament to the New). One could maybe just as easily use the term “application” as “explication.” The use of Explication assumes that several interpretive steps exist between the text and its meaning in the Bible and the meaning produced by its use within or as liturgical text. This exegetical work is of a particular sort: what Henri de Lubac called “allegorical exegesis” and Jean Daniélou, “sacramental typology.”49 Paul’s reading of Israel’s life in 1 Cor. 10 is usually cited as the classic example and exposition of this approach within the confines of Scripture itself.50

I do not want you to be unaware, brothers and sisters, that our ancestors were all under the cloud, and all passed through the sea, and all were baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea, and all ate the same spiritual food, and all drank the same spiritual drink. For they drank from the spiritual rock that followed them, and the rock was Christ.(1 Cor. 10.1-4)

The text goes on to describe the relationship between those earlier events and Christ later in verse 11: “Now all these things happened to them as a type [tupikós in Greek; in figura in the Vulgate] and they were written for our correction.” For both testaments, what lies beyond the literal sense of their text is a spiritual sense that unites the various parts of the Bible into a true unity. The reason for this unity is precisely because of the coherence of action and will of the one God presented therein, specifically in the work of Christ the Son.51 The use of the Bible within liturgical texts can also exhibit this sort of exegesis.

In my earlier discussion of the Pattern use, one of the examples I used was the appeal that the Roman Canon made to the three sacrifices of Abel, Abraham, and Melchizedek. Geoffrey Willis makes the following insightful observation about why the Roman Canon appeals to these the three ancient sacrifices. These three were:

The choice to appeal to those sacrifices indicates a typological exegesis of each as a type or figure of the Christian sacrifice.…clearly chosen because Christian liturgists saw the Eucharist as the fulfilment, not of the Temple sacrifices, of the Old Covenant… but earlier offerings recorded in the Old Testament. These offerings were not offerings repeatedly offered, as were the Levitical offerings, by a succession of priests who were dying and constantly being replaced, but were in each case the offerings of one man, who had no successors.(Willis 1978, pp. 267–80)

This points to another example that I have already used, which reflects a very important point about early eucharistic theology and Biblical interpretation. Michael Vasey puts it like this: “Two facts are clear: the New Testament never speaks of the Eucharist as a sacrifice, and the early church very quickly began to do so.”52 From Didache onward, and as early as Irenaeus and Justin Martyr, Christian liturgies and theologians assume that the Eucharist is a sacrifice, despite the fact that the New Testament never says this.53 Furthermore, they speak of it as a sacrifice without really feeling the need to defend this claim. Hence, the amended quotation in the 1979 BCP of “Christ our Passover is sacrificed for us,” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, pp. 337, 364) rather than “has been sacrificed” for us is another example of Explication. Such a use of this verse from 1 Corinthians 5 indicates a set of exegetical moves that have been made that interprets a co-identity between the one sacrifice of Christ and the offering of the Christian Eucharist in response to the command of Jesus. The dominical institution is interpreted in light of other biblical passages in order to give the Last Supper event a meaning that could not be obtained from the five textual witnesses alone.

One feature that marks the Scottish-American eucharistic tradition in general, and the 1979 BCP in particular, is an embrace of sacrificial language for the eucharist and a corresponding explicit offering of the bread and wine as part of the eucharistic action. This contrasts with the English BCP tradition which never contained an offering of the bread and wine and which, from 1552 onward, avoids any language that could allow for an interpretation of the Eucharist as a sacrifice. Not only does the 1979 BCP stand in rather sharp contrast to the English tradition on this point, but it does also so by way of Explication in its liturgical language for the Eucharist.

Characteristic 2: Names and Locations

Allusions, Quotation, Appropriations, along with all the subcategories, can make use of biblical names and locations. The names of the Virgin Mary and Pontius Pilate are two of the most common since they appear in the Creeds. But these names are also allusions to a cluster of biblical narratives in the Gospels where they figure. Thus, names and locations are often rather dense in their use of biblical sources, as they often refer to more than one parallel biblical passage simultaneously and may also carry with them additional connotations or associations that may also be connected to the larger Christian reception history.

In discussing the Pattern use, I mentioned Abel, Abraham, and Melchizedek. These names are mentioned in the Roman Canon in the context of God’s acceptance of their sacrifices, and it is to these events that reference is made in the appeal for God’s acceptance of the eucharistic offering within the Roman Canon. Nonetheless, the very use of their names necessarily introduces the wider scriptural context and history of each individual. For example, though it is not mentioned in the Roman Canon, hovering in the background is the fact that Cain kills his brother Abel in jealousy precisely because God accepted Abel’s sacrifice and not Cain’s. Thus, that Abel offers an acceptable sacrifice and is then killed is a fact that may be viewed in a figural relationship to Jesus, who is not killed after the offering of his sacrifice, but who offers himself as he allows himself to be killed.