1. Introduction

Since the 1990s, researchers have demonstrated a growing interest in the intersection between medicine and religion (

Puchalski et al. 2014). Specifically, the emerging field of integrative medicine has begun to recognize the need for holistic patient care where one’s psychosocial and spiritual dimensions are integrated into assessment and treatment. In fact, many medical schools now include training on how to support patients’ religious and spiritual needs to help future physicians provide holistic, culturally informed care (

Zaidi 2018). When considering treatment modalities for patients, particularly those suffering from chronic pain, it is important to include various dimensions of life and to provide an individualized patient-centered approach to healthcare (

Puchalski et al. 2014). And yet, challenges exist in designing studies that center on this fruitful “marriage,” including developing relevant questions, adopting the most appropriate methodology, and parsing the results (

Astrow 2019;

Langevin 2023).

1.1. Background and Rationale

Presently, we are in a watershed moment within the Integrative Health Continuum for the incorporation of integrative and spiritual practices in the holistic care of patients (

Zaidi 2018). The concept of integrative care as a healthcare model gained some attention globally in the early decades of the 21st century.

Andersson et al. (

2012) presented a study in Sweden based on focus group discussions that were overall supportive of such a holistic approach to patient care. Stemming from these evolving views about new initiatives in team-based care, we continue to ponder potential new dichotomies in the medical approach to patient pain, namely, team-based versus patient-centered healthcare.

Wynia et al. (

2012) reviewed the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institute of Medicine (IOM), or, as it is now known, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM)’s working group on the topic of team-based healthcare, with or without the inclusion of the patient in such a team.

Of note, according to their website, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) is one of three academies that make up the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in the United States. The National Academies are private, nonprofit institutions that work outside government to offer advice based on the current state of knowledge in science, technology, and health issues (see

https://www.nationalacademies.org/about, accessed on 31 March 2025). Their paper highlights the potential difficulties of a patient-centered team, and it is especially insightful on the topic of accountability. Of note,

Wynia et al. (

2012) note that there are instances when a chaplain may constitute the more skilled leader due to the need for a professional’s training related to spirituality, which is not normally part of medical training.

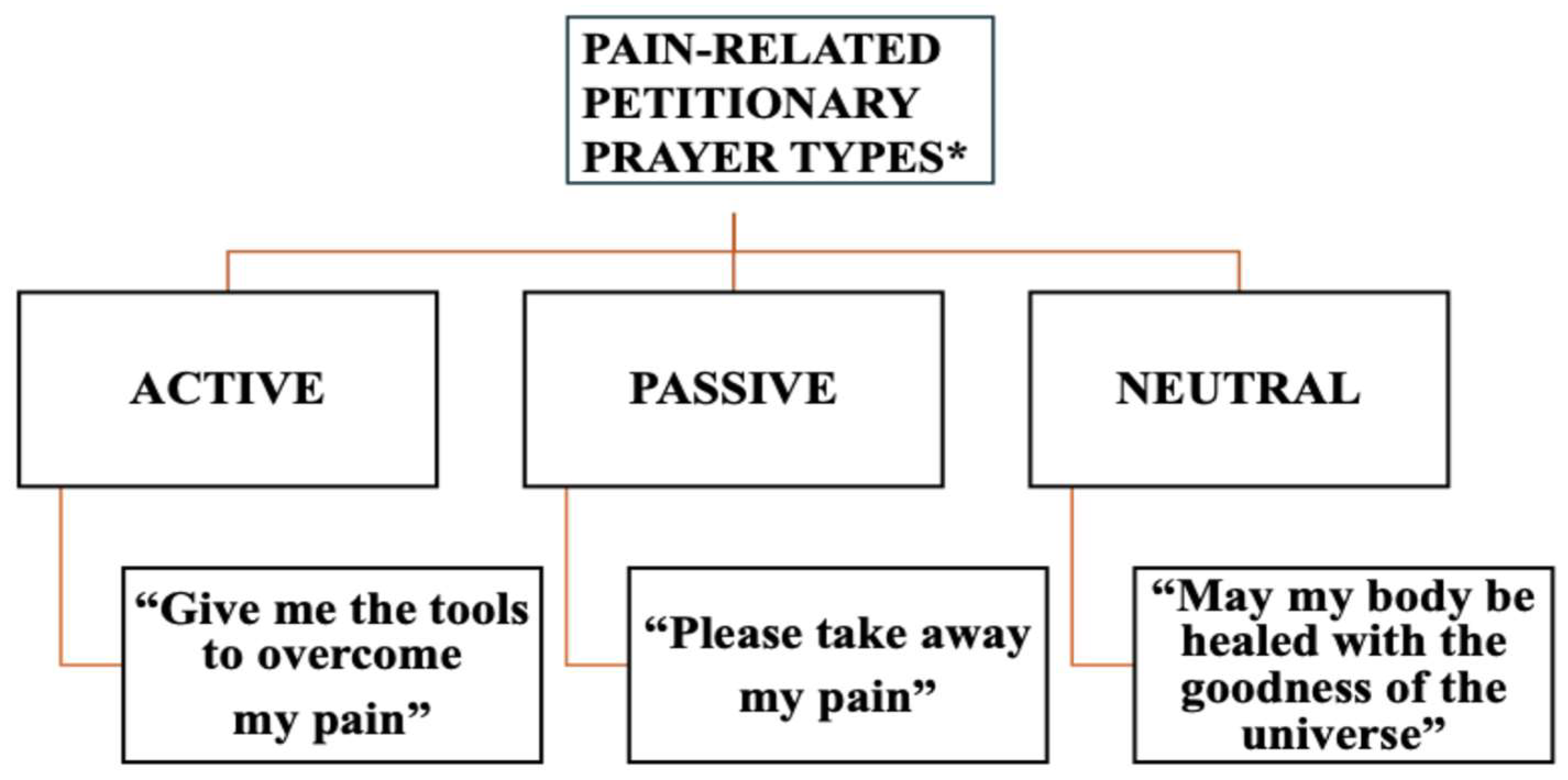

There is a central conundrum in the reconciliation of the work between church and academia. First, academic researchers often overlook the potential value in collaborating with theologically or pastorally trained researchers. While the former typically possess expertise in study design and methodology, they may lack cultural sensitivity to the religious milieu and fail to appreciate the nuanced practices of religious life. Early studies of prayer, for example, rarely characterized the various types of petitionary prayer—passive, active, neutral (

Meints et al. 2018)—nor did they account for the role of prayer in the specific religious expression of the adherents (

Benson 2008). The opposite also presents a challenge. That is, pastoral investigators may not consider how partnering with academic healthcare practitioners might generate empirical data relevant to religious life, physical health, and overall well-being. Thus, the lack of collaboration leads to deficits in research quality and scope and is a disservice to patients.

To mitigate these deficits, we suggest that the church presents a real-time, in vivo

laboratorium for clinical inquiry with broad relevance for healthcare practitioners, mental health researchers, and society at large. For example, large longitudinal studies have shown an association between religious service attendance and decreased all-cause mortality, even after controlling for confounding variables such as physical and mental health and social connections (

Li et al. 2016). What is more, many studies associate religious and spiritual observance with improved mental health (

Weber and Pargament 2014). However, the church typically possesses neither the resources nor the expertise to develop relevant clinical questions, design studies, and carry them through. It is not surprising, therefore, as a myriad of emergent studies in spirituality and healthcare have demonstrated, that having research teams composed solely of either group limits the value of studies on the holistic treatment of patients, especially those suffering from chronic pain.

1.2. The Knowledge Translation Continuum—A Suitable Blueprint

Knowledge translation is a platform bridging the gap between scientific inquiry and end-user healthcare tools, including pastoral tools. A key challenge of the knowledge to action (KTA) framework is overcoming barriers between researchers and end-users (

Graham et al. 2006). One example is the design of empirical studies on the intersection of medicine and religion. Collaboration of church leaders and academics shows promise of leveraging expertise from both domains. In recent pain- and prayer-related research (

Illueca and Doolittle 2020), an identified unmet need was the lack of a validated measure to characterize the types of petitionary prayer used by persons with chronic pain. To date, the only existing measure for prayer and pain, the Coping Skills Questionnaire (CSQ-R), does not cover a complete range of petitionary prayer types (

Rosenstiel and Keefe 1983). The aim of our collaborative effort was to create the first validated Pain-related PRAYER Scale (PPRAYERS) by building an interdisciplinary multi-institutional group of pain and theology experts in a novel “Church and Academia” research model. Central to our model are two key roles: the knowledge user (e.g., a pastor/theologian), who functions within the infrastructure of a religious community, and the academic researcher, who evaluates the mechanism of coping with pain from within the academic arena. The KTA framework is an ideal template for this collaboration.

Given the lack of clear research guidelines in the evaluation of the spiritual aspects of pain, we developed the present blueprint and coined the term Church and Academia Model to provide a powerful infrastructure for the design and implementation of empirical research at the intersection of religion and health.

This report details the Church and Academia Model, with the goal of encouraging similar efforts in the emerging area of spirituality and health research to bridge the chasm between scientific inquiry and patient experience.

1.3. Project Aims

Levin’s (

2020) comprehensive text on religion and medicine describes the long collaboration between the church and the academy. The earliest universities—from Padua and Paris to Oxford and Cambridge—grew out of the church. The earliest hospitals emerged from the church mission to care for the poor and the pilgrim.

Koenig et al.’s (

2023) far-reaching

Handbook of Religion and Health records the seminal research projects in the modern peer-reviewed literature pertaining to religion and health in recent decades.

Our model epitomizes the collaborative process that researchers have endeavored to emulate for decades. We hereby propose that the Church and Academia Model is an ideal fit for the integrated knowledge translation (iKT) category of the knowledge exchange paradigm and a welcome addition to the emerging field of Integrative Health. As explained in the Materials and Methods section, the key stages of a knowledge to action (KTA) framework are all distinctively illustrated by our model.

The intricacies of the knowledge to action (KTA) cycle have been tackled by

Graham et al.’s (

2006) seminal paper and are beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, Graham’s shared stages of the various KTA theories are all represented sequentially in our model, as depicted graphically (

Figure 1). These stages start with the identified unmet need (i.e., a pain-related psychometric scale), informed by research relevant to the knowledge gap (

Illueca and Doolittle 2020;

Meints et al. 2015,

2018). The corresponding research data is then adapted to the creation of the PPRAYERS instrument, and barriers to its design and validation are solved by the Pain and Prayer Collaborative, housed within the Church and Academia Model. Through this project, we are then able to fully design and carry out the scale’s validation study through grant and protocol writing, IRB approval, and study team set-up. Finally, the evaluation, monitoring, and dissemination of the newly acquired knowledge are rolled out through a robust publication strategy, the derivative bedside prayer tool, and collaboration with other research groups. This latter phase assures the sustainability of the data through its translation/validation in other languages and the collection of metrics, as applicable.

This report of a formal mainline church and academia collaboration is notable for the inclusion of theologians, in full participatory capacity, working hand in hand with academics and clinical psychologists, with direct input in all elements of the clinical research study design, including dedicated church grant-writing, data interpretation, and dissemination. This collaboration has resulted in the successful validation of a novel psychometric instrument, whose use will be applicable to clinical research in its original form, with a derivative product, the bedside prayer tool, created for pastoral care and patient self-management. A variety of products from this project will be of practical application within both the theological and scientific fields tending to patients with chronic pain. The sustainability of the data will be monitored through the training of healthcare/pastoral practitioners in the use of the new tool, the future collection of outcome metrics, implementation, where applicable, in the community at large, and the expansion of the use of the tool in other languages. More iKT research work, carried out with our breakthrough model, is needed to provide tangible contributions to the field of spirituality and medicine.

2. Results

We report three key initial outputs resulting from the Pain and Prayer Collaborative:

First, the Church and Academia Model successfully functioned to oversee the creation and validation of the PPRAYERS measure. The study set-up and enrollment completion proceeded from 2020 to 2021. Data analysis for the reliability and validity of the measure was completed following structural equation modeling guidelines. All data analyses supported a three-factor model with distinct prayer subtypes (active, passive, and neutral) based on our theoretical model (

Figure 2), which has been described elsewhere (

Meints et al. 2023).

Second, based on the resulting scale, and the highlighted prayer types, the lead researchers created a derivative bedside prayer tool (

Pain and Prayer Project 2021), a simplified self-administered version of the PPRAYERS measure to be used by both chaplains and healthcare providers caring for chronic pain patients. This tool represents tangible output accessible by the end-users of this new research scale, and a pilot version is available online at a dedicated project website (

www.painandprayer.com, accessed on 7 June 2025).

Third, the dissemination and sustainability of the data continues at the time of writing, along with a thorough plan that has resulted in two publications in academic journals, including the present one. Currently, formal presentations have been given in academic medical and religion meetings, which include the 2022 Conference for Medicine and Religion and various specialty society annual meetings (American Academy of Pain Medicine, U.S. Association for the Study of Pain, and the World Congress of Pain). The latter included poster and Special Interest Groups’ presentations. In addition, a topical symposium with a panel of four spirituality and health experts that included some of our authors (M.I., S.M.M. & B.R.D.) was presented at the U.S. Association for the Study of Pain 2023 Annual Meeting. In addition, both preliminary and complete PPRAYERS study data have been the subject of graduate and medical student conference presentations (2022 Massachusetts Psychological Association and the 2021 University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV)—School of Medicine Research Colloquium). Thus, we are also field testing the model among trainees who will then be able to implement it in their future endeavors.

The next phase of the project is ongoing. The work to translate and culturally validate the PPRAYERS measure in Spanish-speaking populations, especially in the U.S. and Latin America, formally started in 2024. Data from the original PPRAYERS validation will provide a solid foundation for the Spanish validation study.

The proposed model has also been the subject of consultative panel participation and curriculum content development for programs within the American Academy for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)—Dialogue on Science, Ethics, and Religion (DoSER) in May 2024, and Duke Divinity School’s curriculum for the “Integral Health and the Mission of the Church” course for the Hispanic/Latino Pastoral Initiative (HLPI), a Master’s equivalent international program (

Illueca 2025, personal communication, June 7). The latter initiatives also illustrate avenues for the dissemination and sustainability of data gathered by this model.

Limitations

There are several limitations to be considered. First, the collaboration between the church and the academy raises important questions of bias. Would negative or unflattering studies about religious observance be published, especially if denominational leadership subjected projects to their authority? It is important to agree a priori on how the data will be disseminated and to strive for the publication of the study regardless of the directionality of the results. Given that bias exists within the academy, and it is often suspicious of religion and spirituality (

Denberg 2006;

Sloan et al. 2000), we believe that each domain must hold each other accountable.

Second, the Church and Academia Model risks limiting the research questions to a narrow, sectarian perspective. To compensate for this, the research team must be intentional about reaching out to groups composed of people with diverse religious perspectives. In our model, the lead researcher’s ties to the Episcopal Church certainly highlighted this issue. In response, the team solicited participants in several online forums and other religious outlets, including those who were not Christian and members of other non-religious groups. Hence, the final demographic complement was not a function of shortsighted recruitment outreach; rather, it reflected the North American religious landscape trends (

Pew Research Center 2007–2014).

Finally, in developing a psychometric instrument like PPRAYERS, new questionnaires utilize constructs or non-observable variables that cannot be measured or observed directly (e.g., prayer) but rather surmised by the observer. In current spirituality and health research, precise instruments to measure those non-observable variables central to spiritual practice (prayer, meditation, contemplation, etc.) are lacking. Likewise, high heterogeneity in the use of definitions and data presentation is the rule rather than the exception, hence the value of the core study, with the creation of PPRAYERS, to address a knowledge gap with the provision of a duly validated prayer instrument.

3. Discussion

The Church and Academia Model is an ideal fit for the integrated knowledge translation (iKT) category of the knowledge exchange paradigm. This innovative collaboration is notable for the inclusion of theologians, in full participatory capacity, working cooperatively with academics and clinical psychologists, with direct input in all elements of the study design including grant-writing/-procuring, data interpretation, and dissemination. This model resulted in the successful validation of a novel psychometric instrument, applicable to clinical research in its original form, with a derivative product, the bedside prayer tool, created for pastoral care and patient self-management. The sustainability of the data includes the training of healthcare/pastoral practitioners on the new tool, the collection of outcome metrics, implementation, where applicable, in the community at large, and the expansion of the use of the tool in other languages. More iKT research work, represented by our model, will provide tangible contributions to the field of spirituality and medicine.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a mutual, synergistic collaboration between a mainline church denomination and an academic medical center, with direct theological input in all elements of clinical protocol design, dedicated church-grant-writing, and the creation and validation of a novel, non-sectarian, prayer instrument applicable to research and patient care. In this respect, the new role, the Clergy–Medical Liaison (M.I.), provided strategic oversight for the conduct of the project and organized administrative support, participant recruitment, and future training for pastoral and healthcare providers. This project was successful, due in large part to the collaborative trailblazing of the leading researchers. Notably, the first author (M.I.) and senior author (B.R.D.) are both physicians and ordained clergy.

While we have highlighted the academic and research implications of the Church and Academia Model, it is important to also understand how this model can be implemented in the pastoral practice space. For example, long-established programs of Clinical Pastoral Education in the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand require hospital and bedside rotations for pastors and chaplains-in-training (

Cobb et al. 2012). This hands-on and theoretical training is also an integral part of seminary education in various religious denominations, yet it lacks a unified core curriculum around evidence-based medical approaches to spirituality in patient care. Having a model that exemplifies a collaborative approach to rigorous and unified scientific knowledge content is an emerging area of interest for the use of models like ours.

To ensure the viability of such a collaboration, we developed a set of criteria when implementing the Church and Academia Model. First, leadership must build trust, establish credibility, and foster a corps d’esprit within both church and academia. Historically, the church and academia have regarded each other with ambivalence (

Astrow 2019). Of note, it was crucial that a priest and physician (M.I.) represented both church and academia and served the Diocese from where grant-writing, grant award, and participation in protocol design and study implementation were spearheaded.

Notably, such bi-vocational investigators are a hard find, for dual training in theology and healthcare is unusual and in need of a public registry. Second, a strong base must exist within the church; clinical questions need to be drawn from the lived experience of both religious and non-religious participants. In our model, published empirical studies highlighted in a recent publication informed the study’s initial questions (

Illueca and Doolittle 2020). Third, a strong, objective, unbiased humility must exist from academia to ensure methodological rigor, to guide the study, and to provide data analysis and appropriate dissemination.

4. Materials and Methods

As stated in our introduction, to implement the project, the research model composed of church and academia collaborators was developed by modeling a knowledge to action (KTA) framework template (

Figure 1). This framework integrates the knowledge of experts situated in two typically disparate fields (

Graham et al. 2006), such as that in a landmark study of prayer and chronic pain (

Meints et al. 2023). In this synergistic model, church-based and academic researchers have formed a mutual partnership to address a heretofore unmet need within the area of spirituality and pain research. To approach this in a culturally appropriate way, our team also considered the healthcare practitioners’ own beliefs, or lack thereof, to ensure a patient–doctor functional and synergistic unit.

An exemplar of the model is found in the creation of the Pain-Related PRAYER Scale (PPRAYERS) by the study leads (M.I. & S.M.M.), a validated measure of active, passive, and neutral petitionary prayer in response to pain (

Meints et al. 2023). Starting in May 2019, a collaborative project was established between a lead of the Episcopal Church in Delaware (a medical professional/theologian) and an academic/clinical lead (a pain psychologist/researcher) from Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) in Boston. The project goals included the development of a prayer-based psychometric measure and the creation of a bedside prayer tool for use in pain-related chronic conditions. In consultation with academic experts, the study leads (MI and SM) created the PPRAYERS and an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol to validate the instrument.

This project included grant writing, recruitment, data analysis, and the dissemination of findings. Additionally, there was a due diligence consultation with experts from five academic centers—Duke, Harvard, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI), Tufts, and Yale—on the protocol guidelines for the content and validation of the new psychometric measure.

A theoretical template about personal and petitionary content types was used to develop the PPRAYERS measure with the purpose of addressing an unmet clinical and research need, and relevant to our model, a practical tool for chronic-pain patients drawing from medical knowledge and religious resources. The plan included an IRB-approved protocol to validate the newly created instrument based on empirical data supporting the potential benefits of certain types of prayers (i.e., active versus passive prayer) in the context of coping with chronic pain (

Meints et al. 2018).

The expanded collaboration consisted of the church team (a priest, a seven-member volunteer group for outreach/recruitment, diocesan support, and interfaith and international networks) and the academic team (a psychologist/lab manager from BWH’s Pain Research Lab, a research intern from Boston University’s Master of Medical Science program, and a psychologist/statistician from IUPUI). The church lead (M.I.) wrote, applied for, and received the 2020 United Thank Offering Grant from the Episcopal Church in the United States to support both the creation of the Clergy–Medical Research Liaison position for the Diocese of Delaware and the church side of the study project.

Further support was rendered by a physician and minister (B.R.D.) with experience in quantitative research on the faculty of Yale University School of Medicine and Yale Divinity School. The academic lead (S.M.M.), and her research lab, together with (D.O.), provided psychological expertise in study design and instrument development/validation. Further, the academic research team obtained Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and managed data collection, analysis, and tracking via the RALLY/RED Cap system for electronic enrollment and data capture. Additional support was facilitated by the National Institutes of Health (NIH K23AR077088) provided to (S.M.M.). Specifically, the latter provided protected time to conduct research but did not financially support project-related activities.

5. Conclusions

In this report, we describe a novel collaborative prototype of pastoral workers and clinical researchers that is faithful to the principles of participatory research. We have coined the term Church and Academia Model to describe what we consider an ideal fit within the emerging arena of the knowledge exchange paradigm.

Briefly, the latter is a scheme of “collaborative research, where researchers work with knowledge users who identify a problem and have the authority to implement the research recommendations” (

Kothari and Wathen 2017). More specifically, the knowledge to action (KTA) framework, as described by

Graham et al. (

2006), encourages collaboration between experts from two usually separate fields—such as our study on prayer and chronic pain (

Meints et al. 2023).

Therefore, we conclude that the Church and Academia Model offers a compelling blueprint for future research at the intersection of religion and health. This partnership allows researchers direct access to religious communities in order to design and evaluate relevant programs. In turn, it allows the church to benefit from the expertise of researchers—resources that are often out of reach. Historically, the church has relied on the tri-partite foundation of reason–scripture–tradition to guide its life and practice (

Grieb 2018). The Church and Academia Model aligns well with this tradition.

The Church and Academia Model activates the academy in real world, pressing questions that confront the church. In a time when the academy may engage in solipsistic, self-referential scholarship, the Church and Academia Model serves as a dynamic bridge between these two communities. This model challenges scholars to move beyond insular debates to embrace a broader mission that directly supports the moral, spiritual, and communal challenges of our age. In doing so, this model re-centers the academy on essential human concerns of pain, suffering, and community, re-infuses the academy with an elevated purpose, and holds the academy accountable to its core mission both to expand knowledge and to serve the public good.

Similarly, the Church and Academia Model holds the church accountable. This model challenges the church to re-evaluate long-held traditions that may no longer be effective and opens the church to new avenues of inquiry and growth. The academy need not threaten the authority of the church. Rather, the church becomes stronger, more relevant, more engaged in the life of its people. The data drives the conversation—especially in an age of post-modern skepticism. Empirical observation does not replace doctrine but rather complements discernment. For the church to be relevant to society at large, empirical investigation can translate the efficacy of religious observance to physical and mental health. In an era of institutional distrust, the Church and Academia Model demonstrates intellectual humility and public accountability. In turn, this fosters renewed trust and opens the doors to meaningful dialog among skeptics and believers alike.

The specific projects we describe—such as the PPRAYERS study—are replicable partnerships that can be implemented by similarly interested church and academic communities. The key elements of trust, credibility, humility, and a strong corps d’esprit are both barriers and opportunities within these two communities. Cultivating these qualities intentionally may transform historical tensions and enrich both the church and the academy. Pain and suffering are shared by many, and prayer is a cornerstone of religious practice. This makes our projects relevant and urgent to the life of the church.

And yet, there are many compelling questions that the Church and Academia Model might explore in future research. In a post-COVID-19 era where loneliness and anxiety are so prevalent, what is the association between religious observance and belonging? With an increased burden of chronic disease such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, and the newly recognized Long COVID syndrome, how might religious observance impact outcomes? Are there elements of religious observance that could be applied to secular settings that may improve health outcomes? At a time when communities are grappling with mental health challenges and cultural fragmentation, research that explores communal religious practice becomes even more essential.

Finally, the area of knowledge translation may benefit from the continued use of our research model, which leverages the strengths of both domains synergistically to address complicated research or clinical questions. At the same time, more integrated bedside collaborations by clinical and pastoral workers informed by our model are needed to provide tangible contributions to the field of religion and medicine, and to the real and ultimate end-user, that is, our patients.