Abstract

This article examines the contributions of Turkish screenwriter Ayşe Şasa (1941–2014) to Turkish cinema and visual culture through her engagement with Sufism and metaphysical themes. It explores how Şasa draws on esoteric Sufi concepts such as the oneness of being (waḥdat al-wujūd), asceticism (zuhd), and inspiration (ilhām), using cinema as a vehicle for spiritual inquiry and the quest for truth (ḥaqīqa). Her films—including Hear the Reed (Dinle Neyden), The Night That Never Was (Hiçbir Gece), and My Friend the Devil (Arkadaşım Şeytan)—are explored through thematic and interpretive approaches that uncover their Sufi dimensions. The methodological approach combines Gillian Rose’s visual methodology, Klaus Krippendorff’s content analysis, and Arthur Asa Berger’s interpretive model. Rose’s framework facilitates an exploration of symbolic narrative in Şasa’s films and writings, while Krippendorff’s methods identify recurring metaphysical motifs. Berger’s approach uncovers layered meanings in visual and narrative elements. Through narrative structure, symbolic imagery, color, setting, costume, light, and sound, Şasa constructs a spiritually resonant cinematic esthetic that challenges the secular paradigms of modern cinema. Ultimately, this article argues that Şasa develops a distinct cinematic language grounded in Sufi metaphysics, enriching Turkish visual culture with a profound spiritual and moral sensibility.

Keywords:

Ayşe Şasa; Turkish cinema; Sufism; Ibn ʿArabī; mystical thought; female vision; visual culture 1. Introduction

Ayşe Şasa (1941–2014), a well-known screenwriter of Turkish cinema, stands out for her Sufi orientation, which profoundly shaped her artistic and spiritual journey. Key life events influenced both her religious beliefs and her screenplay writing. Her orientation towards Sufism led to significant changes in her cinematic production. As a representation of a female figure in Turkish cinema who underwent an artistic and spiritual transformation, Şasa has cinematically expressed the Sufi teachings of self-knowledge in her works. The principles of Sufism that lead the individual away from the material world and toward the search for spiritual fulfillment are a prominent theme in Şasa’s films. Themes such as asceticism (zuhd) and trust in God (tawakkul) are intricately woven into her visual and narrative frameworks. Notably, the concept of the ‘unity of being’ (waḥdat al-wujūd), derived from the ideas of the mystic Ibn ʿArabī (1165–1240), occupies a central place in his metaphysical thought. According to this doctrine, there is only one being—God—and all forms of existence are manifestations or reflections of this one being (Chittick 1989, p. 79). This teaching emphasizes the absolute connectedness of creation to the divine and finds powerful symbolic expression in Hear the Reed (Dinle Neyden). Through metaphors such as whirling dervishes and the nay (Turkish ney, reed flute), the film symbolically conveys the mystical worldview in which all existence aspires to return to its origin in the one (Chittick 1989, pp. 115–21).

Through her screenplays, Şasa rejects the secular and materialist views she associated with Western culture. This perspective is deeply rooted in her engagement with Sufism and her critiques of modernity. In this context, visual culture theory is essential for understanding Şasa’s cinema.

Visual culture profoundly shapes the way individuals make sense of events, with cinema serving as one of its most powerful instruments. Nicholas Mirzoeff emphasizes cinema’s narrative capacity to convey specific worldviews to the audience, arguing that visual culture functions as a medium through which beliefs, ideologies, and intellectual frameworks are communicated (Mirzoeff 2002, p. 10). Şasa’s cinematic approach resonates with Mirzoeff’s perspective, particularly his view of cinema as a form of visual activism (Mirzoeff 2016, p. 283).

In this context, Şasa’s films, grounded in Sufi concepts, transform cinema into a vehicle for visual culture that seeks to affect both the individual and society, extending beyond mere entertainment. As Mirzoeff’s notion of visual activism suggests (Mirzoeff 2002, p. 10), her work communicates Sufi thought in a way that invites viewers into an intellectual and spiritual space. Drawing on the doctrine of waḥdat al-wujūd, Şasa uses natural elements—such as wind, snow, forest, and sea—alongside Sufi rituals and distinctive sounds to give visual and auditory form to this metaphysical worldview. In doing so, she engages in visual activism by bringing the spiritual principles of Sufism into cinematic expression.

Guy Debord critiques the role of visual culture within the modern capitalist system, arguing that authentic experiences have been supplanted by spectacles, leaving individuals trapped in an “illusion of reality”. In this framework, he argues that visual culture should transform into a space where individuals can resist this illusion of reality and produce real meaning (Debord and Knabb 2002, pp. 4–7). Şasa’s cinema stands apart from Debord’s “society of the spectacle”; her films do not fall prey to superficiality in favor of spiritual depth and human experience. With this approach, she opposes the dominant paradigm’s vacuous and detrimental cinematic production, offering instead a cinema grounded in the search for meaning and personal transformation.

Thomas Elsaesser and Malte Hagener argue that cinema, as a facet of visual culture, provides not just narrative content but an emotional and visual experience—what they term a “technology of perception”—capable of shaping both individual and collective sensibilities (Elsaesser and Hagener 2009, pp. 1–10). Şasa’s screenplays also assume such a role. Through musical elements and evocative religious spaces—such as mosques and graveyards—her films cultivate a sensory and spiritual resonance. Moreover, Şasa foregrounds female Sufism by centering female characters in her narratives, depicting their spiritual quests and tawakkul (trust in God). In doing so, she enriches visual culture with representations of women’s spiritual agency and deepens the cinematic portrayal of the female Sufi experience.

This article examines how Şasa visualizes Sufi concepts, symbols, and ideas in her films and writings, with particular attention to how these themes are reflected through both visual and auditory elements. It asks the following questions: What vision of Sufism emerges from the symbols, motifs, and themes she employs? How do elements such as music, natural sounds, clothing, color, and setting articulate Sufi teachings? It also considers Şasa’s contribution to visual culture in relation to female Sufism, offering insight into women’s spiritual experiences. Finally, the analysis explores the transformative journeys of her characters, identifying the Sufi concepts that best explain their inner change. To address these questions, her screenplays were examined alongside her books, interviews, and relevant academic studies.

A thematic and interpretive analysis was applied to Şasa’s creative works. Drawing on Gillian Rose’s visual methodology, this study explores how visual elements convey symbolic and thematic narratives (Rose 2016). Klaus Krippendorff’s framework supports the examination of the contextual meanings and communicative effects of visual media (Krippendorff 2018). John Berger’s approach further informs the analysis, emphasizing the discovery of deeper meanings through close reading of media content (Berger 1991, pp. 77–95). These methodologies collectively inform the interpretive lens through which Şasa’s work is approached.

The analysis focuses on Sufi elements in Şasa’s oeuvre within the broader framework of visual culture. Key themes—such as character development, locations, color symbolism, musical motifs, lighting, soundscapes, dialog, and narrative structure—were identified and systematically examined to understand how Sufism is visually and textually expressed. Only works with explicit Sufi content were included. This study began by identifying central Sufi themes, such as tawakkul, followed by an analysis of how these were expressed and communicated to the audience. Krippendorff’s method of data coding helped guide this stage of interpretation (Krippendorff 2018).

Reliability was ensured by repeatedly reviewing Şasa’s films and writings throughout the process of theme identification and analysis. Validity was supported through an extensive review of the relevant literature and close reading of recurring themes and motifs. The findings were interpreted by situating these themes within the broader Sufi framework, examining how Şasa expresses Sufi ideas visually, aurally, and narratively—particularly in her films. In doing so, this study highlights the presence and articulation of Sufi elements in her cinematic work.

2. Early Life and Education: Loneliness and Trauma

Şasa was born in Istanbul on 1 February 1941 to a conservative and wealthy family. The fact that she was a girl was a disappointment to her family, who were bound by patriarchal traditions. Rejected by her mother, who refused to nurse her, she was raised by a Jewish nanny until the age of five. This early experience influenced her initial conception of God, whom she referred to as Lieber Gott (“dear God” in German)—a term she later described as alienating (Şasa 2012, pp. 26, 33). The nanny, who had strong ties to Christian culture and spoke German through her close association with German friends, played a formative role in Şasa’s early spiritual outlook (Şasa 2012, p. 34).

Raised by Christian nannies thereafter, Şasa frequently visited churches and identified with the suffering of Jesus, which influenced her interest in Christian literature and shaped her feelings of guilt and depression (Şasa 2012, pp. 37, 43–44). At the American College for Girls, Şasa excelled academically and creatively, producing plays and magazines. The school’s anti-Islamic and humanist philosophy drove her away from her religious beliefs and into Marxism and nihilism (Şasa 2012, pp. 55, 74–75).

Şasa’s upbringing in a family characterized by gender inequality created a sense of loneliness. Growing up with Jewish and Christian nannies also led to religious and cultural identity confusion. This confusion continued almost throughout her life.

3. Youth and Early Screenwriting

Şasa began her screenwriting career after graduating from college. At just 18 years old, she married the famous Turkish theater and cinema director Atilla Tokatlı (1934–1988), divorced a year later, studied Business Administration at Boğaziçi University for a short time, and started writing screenplays again (Şasa 2012, pp. 76, 82, 91). In 1964, Şasa became the secretary of the renowned Turkish director Atıf Yılmaz (1925–2006) and later married him. Thus, she became a part of Yeşilçam cinema, the golden age of Turkish cinema (Şasa 2012, pp. 93–98). During the Yeşilçam period (1950–1980), important films were produced by many talented filmmakers, screenwriters, and actors. Influenced by her conversations with prominent Turkish filmmakers of the time, such as Halit Refiğ (1934–2009) and Metin Erksan (1929–2012), Şasa stated that she was drawn into Marxism—a worldview she had already been exposed to throughout her education (Şasa 2010, p. 17). Consequently, in the early years of her cinematic experience, she adopted an anti-Western Marxist stance, advocating for cultural authenticity and resisting alienation (Aksoy 2014, p. 120; Şasa 2010, p. 62). She strongly opposed attempts to model Turkish cinema after Western cinematic traditions (Şasa 2010, p. 62). Following major personal challenges, including the death of her close friend, the prominent Turkish author Kemal Tahir (1910–1973), and her divorce from her husband, Atıf Yılmaz, she experienced severe psychiatric disorders. As a result of these difficulties, Şasa was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1979 (Şasa 2012, pp. 107–17).

4. Spiritual Crisis and the Quest for Truth: ‘Rebirth’

Şasa discovered Sufism during her struggle with schizophrenia. She first encountered Ibn ʿArabī’s name in a book catalog and ordered Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam (The Bezels of Wisdom), though she initially left it unread. During this period, she battled sleeping pill addiction and survived two suicide attempts (Kara 2020, p. 133; Şasa 2012, p. 120). Şasa started reading Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam in 1981 or 1982 and initially had difficulty understanding its terms. After a while, she was enlightened while reading the book, and her worldview transformed. The ḥadīth (reports attributed to the Prophet Moḥammad) “I was a hidden treasure, and I wanted to be known” became an important starting point for her religious beliefs. Viewing the book as a divine favor, Şasa saw her illness as a chance to shed falsehoods and attain true spiritual awakening (Şasa 2012, pp. 127–28). After 18 years of struggling with schizophrenia, Şasa stated she was cured through reading Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam (Şasa 2012, p. 131).

Şasa joined the Nureddin Cerrahi Tekke (dervish lodge) in Karagümrük, Fatih, and became a disciple of Safer Dal Efendi (1926–1999), the pūstnishīn of the tekke (Kara 2020, pp. 137–38; Şasa 2012, p. 141). Nureddin Cerrahi (1672–1721) was the first pūstnishīn of this tekke belonging to the Cerrahi (Jerrāhī) branch of the Halveti Sufi order (Tanman 2007, p. 253; see Yola 1982). In 1985, Safer Dal became pūstnishīn and continued to guide the dervishes (Dal 2013, p. 15; Geels 1993, p. 54). Safer Dal, the successor of the Jerrāhī shaykh Muzaffer Özak (196–1985), was deeply interested in Turkish Sufi music and transmitted his knowledge of music and tekke culture to his disciples during his spiritual discourses (Çakır and Dal 2020, p. 303). Although tekkes were officially closed by law in Turkey in 1925, many continued to function unofficially. This particular tekke, operating under the guise of a foundation for preserving Turkish Sufi music, became one of the most important centers of Sufi culture and music in Istanbul (Tanman 2007, p. 254).

Şasa attended Safer Efendi’s spiritual discourses for seven years (Çakır 2015, p. 59; Demirel Uyar 2015, p. 31). These sessions likely deepened her understanding of waḥdat al-wujūd. Safer Efendi played a crucial role in guiding her out of spiritual darkness by introducing her to the metaphysical teachings of Ibn ʿArabī. He affectionately referred to her as “Ibn ʿArabī’s daughter” (Çakır 2015, p. 57). During her illness, he spoke to her about the impermanence of the world and the nature of death, remarking, “Death is a delicious thing, death.” He also urged her to “Die before dying”, encouraging the transcendence of ego and selfish desires before physical death as a means to attain union with the divine. Through this deeply personal guidance, Safer Efendi helped Şasa grasp the essence of waḥdat al-wujūd, linking its abstract metaphysical dimensions to her lived experience (Çakır 2015, pp. 58–59).

With the inspiration derived from Safer Efendi’s discourses, Şasa began to understand Sufi ethics more deeply. Safer Efendi advised Şasa to “embrace the path of a dervish, to serve God with love, and to approach everything in the world with compassion” (Çakır 2015, p. 57). Şasa passed away on 16 June 2014 in Istanbul, leaving many films and books behind (Bayraklı 2016, p. 44; Kara 2020, p. 141).

5. The Transformation of Şasa’s Screenwriting: From Marxism to Sufism

The transformations in the intellectual, psychological, and mystical orientations of Şasa’s life lead us to consider her artistic works in three periods. In the early years of her screenwriting career, 1960–1970, Şasa was influenced by Marxism. In films such as Oh Beautiful Istanbul (1966) and Arif of Balat (1967), Sasa defended preserving local identity and resisted cultural alienation (Aksoy 2014, p. 120; İşler Sevindi 2018, pp. 90–104; Şasa 2010, pp. 62–63). She strongly opposed efforts to make Turkish cinema similar to Western cinema (Şasa 2010, pp. 62–63). During these years, she used cinema as a tool for Marxist criticism.

Between 1970 and 1980, the second phase of her screenwriting career, Şasa renounced Marxism and embraced Islam. She described her 1972 film Shame (Utanç) as “an exploration of the Jewish and Christian influences that shaped his childhood and youth”, highlighting themes of social morality. The screenplays Şasa wrote from 1980 to 2008 mark the third phase of her career, characterized by a focus on mystical and moral themes. These works visualize moral decline and offer spiritual paths toward renewal. In My Friend the Devil (1988), she tells the story of a singer who sells his soul to the devil for wealth and fame, leading to moral and spiritual collapse. The Night That Never Was (1989) explores the dilemmas of modern life and the search for spiritual fulfillment. Her final screenplay, Hear the Reed (2008), follows the inner journey of a Mevlevi dervish through self-purification and transformation, drawing on the teachings of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī (1207–1273) and exploring themes of divine love, asceticism, and spiritual renewal.

6. Artistic Expression of Reality: Cinema and Sufism in the Modern World

After encountering Sufi thought in the 1980s, Şasa began to view cinema as a medium for conveying moral and spiritual teachings. Integrating this vision into her writings and films, she developed a distinctive cinematic language to communicate esoteric Sufi concepts—particularly the teachings of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī and Ibn ʿArabī—to a broader audience.

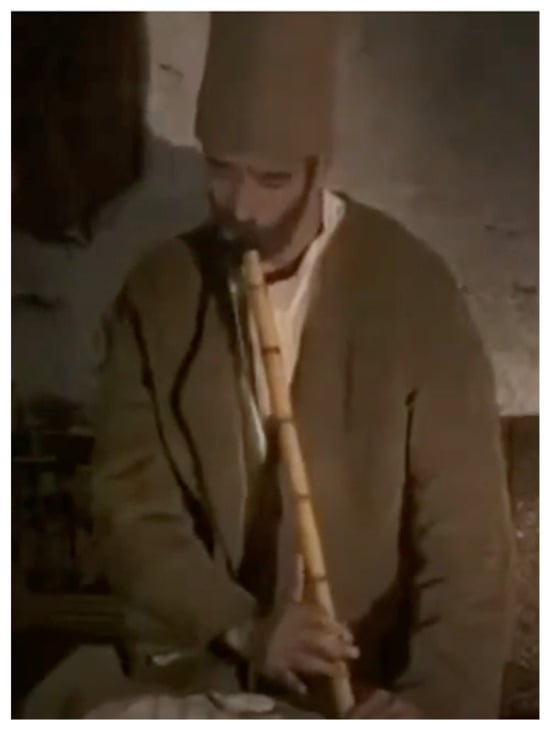

By placing tawḥīd (unity of God)—the core belief of Islam is to believe in the oneness of God with the mind and heart—at the center of her cinematic narrative (Şasa 2010, p. 17), Şasa advocated an approach that emphasized tawḥīd in Turkish cinema (Şasa 2010, p. 135). In Hear the Reed, Şasa visualizes tawḥīd through Rūmī’s metaphor of the nay. In Rūmī’s thought, the nay represents the human soul’s separation from God and longing to reunite (Rūmī 2002, 1: 7). In the film, the nay is used as a visual and auditory element that expresses the dervish character’s longing for God and his realization of tawḥīd (Figure 1). His prayers and monologs also contain content expressing the tawḥīd theme.

Figure 1.

Nay-playing dervish in Hear the Reed (2008, 95 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

My Friend the Devil is narrated in the context of tawḥīd, showing the repentance of a singer who made a deal with the devil. Under the control of the devil’s evil, the singer turns away from God and pursues his material ambitions. However, this leads him to spiritual dilemmas. This demonic characteristic underlined by Şasa coincides with Rūmī’s view that the person who follows the devil loses his dignity and spiritual values (Awn 1983, p. 62). Realizing the wrongness of following the devil, the singer returns to belief in tawḥīd. In the film, the scenes in which the devil’s evil dominates are dark, while the scenes in which tawḥīd and faith come to the fore are bright (Figure 2). This use of light strengthens the visual narrative. At the end of the film, the devil and the singer, sitting in front of a mosque to the sound of the call to prayer (azān), evoke the concept of tawḥīd, having a dialog about the oneness of God. The devil repents and believes in God and is then visualized as a winged angel (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The singer strikes a deal with the devil in a dark scene from My Friend the Devil (1988, 87 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

Figure 3.

The devil transforms into a winged angel in My Friend the Devil (1988, 87 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

In her cinematic thought, Şasa criticizes modernism and secularism, proposing approaches that reflect universal reality (Şasa 2010, p. 121). According to her, Sufism provides this depth and offers artists the approach they need to go deeper into the inner depths of the audience (Şasa 2006, p. 125). Şasa’s point of view reflects her belief in the core teachings of Sufism because, according to Sufis, to reach the truth, one must recognize one’s self and undergo the necessary spiritual transformations. The concepts of self-knowledge (maʿrifa al-nafs) and knowledge of God (maʿrifa Allāh) define this path. Early-period Sufis believe that purifying negative traits and fostering virtues lead to self-discovery, ultimately revealing God and truth (al-Qushayrī 1914, p. 315; Kāshānī 1996, p. 321).

Şasa visualizes the theme of self-knowledge in Hear the Reed, primarily through the characters’ inner dialogs, accompanied by the sound of the nay. These conversations reflect the human journey of self-knowledge and the search for truth. In Rūmī’s thought, the nay symbolizes the nothingness of the human. Like the nay, an empty flute, humans only gain meaning through divine breath. Furthermore, as the nay’s sound closely resembles the human voice, it is regarded as the instrument that most accurately symbolizes the human essence (Schimmel 2001, pp. 198–99). The sound of the nay reminds the dervish character of his emptiness—his nothingness—and helps him to realize his existential state. In the film, the nay appears as a visual element describing the dervish’s path from self-knowledge to knowing God.

Another Sufi concept that Şasa visualizes in Hear the Reed is riḍā—contentment with and acceptance of God’s will without resistance or complaint (al-Jurjānī n.d., p. 148; al-Qushayrī 1914, pp. 193–94; al-Sarrāj al-Ṭūsī 1960, p. 80). Şasa illustrates this notion through the story of a Mevlevi shaykh. The shaykh’s acceptance of his suffering is presented as a path to nearness with the divine. In the scene depicting the progression of his illness, birds chirping in the background signal his inner peace and acceptance, while snowfall at his funeral visually evokes the serenity and finality of his surrender (Figure 4). The shaykh’s riḍā aligns with Rūmī’s own teachings, as expressed in the Mathnawī: “Some saints who are content with the divine ordinances and do not pray and beseech (God) to change this decree” (Rūmī 2002, 3: 207), describing the state of contentment of the shaykhs with God’s will.

Figure 4.

Snow falls at a funeral in Hear the Reed (2008, 95 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

The most notable aspect of Şasa’s cinematic approach is her emphasis on the concept of universal reality, or, in other words, eternal wisdom. This concept of eternal wisdom lies at the heart of traditionalism, which was represented in the 20th century by intellectuals such as René Guénon (1886–1951), Frithjof Schuon (1907–1988), and Martin Lings (1909–2005). Traditionalism recognizes that all religions and mystical traditions are based on a single universal reality and rejects modernism’s denial of faith and spirituality (Guenon 1975; Huxley 1947; Lings 1975; Schuon 1993). Şasa frequently referred to the works of these intellectuals, particularly Guénon and Lings, and adopted their metaphysical and spiritual perspectives on Islam as a guiding framework for her artistic works (Şasa 2006, p. 147; Şasa 2010, pp. 117–18; Yalsızuçanlar 1997, p. 8).

Şasa’s The Night That Never Was visualizes the spiritual emptiness of the modern world through the character of Sevda. Sevda’s loneliness and depression reflect on screen the most important problem of people in modern times. In some scenes, Sevda, who lives a secular life and drinks constantly, is told that she is unsatisfied with fame and wealth; this depicts mental breakdown and restlessness, and the meaninglessness of the temporary pleasures of modern life is emphasized. The most striking religious motif in the film is in a bar scene. In a bar, the wall paintings of Jesus Christ and Mary draw attention to Sevda’s search for love (Figure 5). The photographs of the human body opposite these wall paintings refer to temporary pleasures (Figure 6). Sevda’s life is like these two opposites. On the one hand, there is modern life and fame; on the other hand, there is the search for inner peace. Sevda is in search of self in this dilemma in modern life. This narrative of Şasa’s undoubtedly reflects the influence of Christianity from her childhood.

Figure 5.

Wall paintings in the bar in The Night That Never Was (1989, 81 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

Figure 6.

Photographs on the wall depicting the human body in The Night That Never Was (1989, 81 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

In My Friend the Devil, Şasa emphasizes the power of the devil, arrogance, and greed to lead people away from universal reality. The singer makes a deal with the devil for more money and fame. This deal destroys his world of faith and inner happiness, making him a failure in every sense. In one scene, the devil’s remark about wanting to “make people ordinary” symbolizes modern superficiality and materialism. Through the singer character who loses his peace by following the path of the devil, Şasa suggests getting rid of the traps of modernism.

According to Şasa, Sufi thought approaches media and cinema as a “veil of insight”. This insight ultimately reveals the divine and the reality behind existence. She emphasizes the concept of inspiration (ilhām) (Şasa 2006, p. 107; Şasa 2010, p. 88; Yalsızuçanlar 1997, p. 15). Ilhām is the spiritual knowledge and understanding God gives to the servant’s heart (al-Qushayrī 1914, p. 84; Kāshānī 1996, p. 232). Şasa believes that artists should try to produce films with divine inspiration to offer the audience an approach to the truth.

In Hear the Reed, Şasa mainly uses the contrast between darkness and candlelight to depict ilhām visually (Figure 7). Candlelight illuminates the environment in scenes with characters searching for truth, while darkness is used in scenes that contextually depict ignorance or worldly ambitions. Thus, Şasa uses light to refer to divine inspiration, the endeavor to reach the truth, and darkness to depict ego and ignorance. The candle is a light that dispels the darkness, illuminates the dervish’s path to God, and symbolizes divine inspiration. In the film, the candlelight is visualized very faintly. This image suggests that the dervish must be patient and stroll to reach God. As the candle slowly melts and disappears, it symbolizes the release of the ego and the realization of the state of nothingness. In this narrative of Şasa, there is a trace of the views of Rūmī and her shaykh Safer Efendi. Indeed, Rūmī explains this with the ḥadīth “Die before you die” (Rūmī 2002, 1: 39), expressing the dervish’s need to kill his bad attributes and acquire good virtues to reach divine inspiration. This theme also brings to mind Safer Efendi’s words during Şasa’s illness: “Death is a delicious thing, death” (Çakır 2015, pp. 58–59).

Figure 7.

Candlelight and dervish in Hear the Reed (2008, 95 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

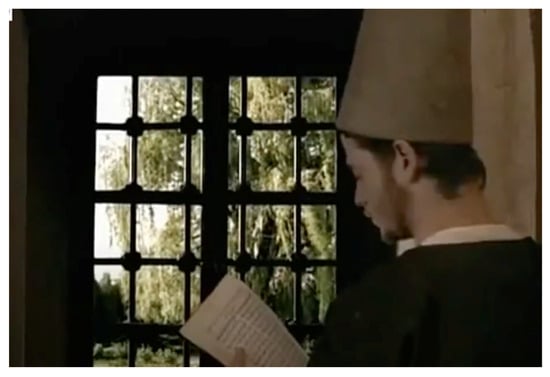

Other key elements through which Şasa visualizes ilhām are “window” and “light”. The wind blowing behind the sick shaykh tells him of God’s ilhām and favor (Figure 8). The window contextually symbolizes a situation that opens from the world to the divine realm. The subtle light seeping into the room through the window symbolizes divine inspiration and represents the gradual enlightenment of the soul.

Figure 8.

The window behind the shaykh in Hear the Reed (2008, 95 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

Şasa describes Russian director and screenwriter Andrei Tarkovsky (1932–1986) as a mystically inspired artist who elevated cinema into a spiritual art form. She suggests that Turkish filmmakers, too, explore mystical dimensions (Şasa 2010, p. 88). Tarkovsky rejected viewing cinema as inherently connected to spirituality, and championed a narrative grounded in the soul’s journey toward the divine (Tarkovski 2008, pp. 27–28). Following in Tarkovsky’s footsteps, Şasa was inspired by his artistic vision and reflected this inspiration in her films and writings on cinema. His seminal work Sculpting in Time, in which he critiques modern cinema as a disposable commodity, played a key role in shaping Şasa’s critique. Tarkovsky argued that cinema should probe the deeper meaning of human existence and the cosmos (Tarkovski 2008, p. 28), a perspective that resonated deeply with Şasa’s own cinematic philosophy.

Şasa criticizes visual media, including cinema and television, for promoting consumption, violence, and secularism, often lacking spirituality (Şasa 2010, p. 53; Ural 2015, p. 270). She argues that while some films glorify darkness, others invite viewers toward spiritual revelation. Şasa praises Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublyov (1966) as a prime example of cinema that conveys a spiritual awakening, a journey of inner transformation. The protagonist, Rublyov, is portrayed as a mystic and artist dedicated to serving humanity through his art (Tarkovski 2009, pp. 14–18).

According to Şasa, Tarkovsky diminishes the audience’s engagement with the profane through this film, directing people to the depths of their hearts and the sacred (Şasa 2010, p. 53). Şasa describes the film with the words “It is exciting to watch how the technique of cinema, the product of the technological society, in the hands of a dervish, serves the complete negation of this civilization.” (Şasa 2010, p. 53; Ural 2015, p. 270). Şasa appreciates Tarkovsky for dealing with deep existential and metaphysical issues in his films and using cinema as a spiritual tool.

Şasa, in Hear the Reed, emphasizes the protagonist’s spiritual journey, as in Tarkovsky’s film Andrei Rublyov. Much like Rublyov’s art is portrayed as a path toward truth, Şasa uses the sound of the nay as a symbol guiding the dervish toward divine truth. Andrei Rublyov’s search for spiritual peace and his journey to the truth is the defining element of the screenplay. Despite depicting different religious and cultural elements and different historical periods, the protagonists’ journeys into their inner worlds in both films are told in long sequences and slow-moving scenes. This visual narrative draws the audience’s attention to spiritual themes.

While criticizing modern and secular approaches to cinema, Şasa advocates a spiritual perspective in cinema. For Şasa, cinema is not only a visual narrative tool but also a tool that can lead people to spiritual realizations. In this context, Şasa emphasizes the Sufi concept of zuhd, which involves distancing oneself from worldly desires and detaching the heart from everything except God (al-Qushayrī 1914, pp. 115–19). One who wants to strengthen his connection with God should control their ego and distance themself from worldly desires (al-ʿAfīfī n.d.a, pp. 63–65).

Şasa emphasizes the reflections of zuhd in Hear the Reed through the use of color. The pure earth tones in the characters’ clothes, locations, and decorations symbolize simplicity and purity (Figure 9). Earth is also a motif that tells us that humans come from earth at the beginning of creation and will return to earth when they die. For this reason, earth tones are used in the film as a visual element that reminds people of death and the transience of worldly pleasures. In the film, the dervishes’ brown hat and black robe are a visual element in the Mevlevi tradition, symbolizing the tombstone and the grave, showing the world’s transience and detachment from it (Özcan 2004, p. 466; Kılınç 2011, pp. 814–15; Gündüzöz 2008, pp. 42–45; Gürer and Ulupınar 2023, p. 113).

Figure 9.

Use of color in Hear the Reed (2008, 95 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

In The Night That Never Was, Şasa visualizes the protagonist Sevda’s spiritual crisis within bars and crowded settings while her search for peace unfolds in scenes by the sea or the forest (Figure 10). Through these contrasting spaces, Şasa portrays moments when the human soul disconnects from worldly attachments and finds simplicity in the sea’s vastness and the forest’s quiet. Elements of nature, such as the sea and the forest, are narrative elements that suggest Sevda’s approach to inner peace as she begins to move away from worldly desires. Her conversations with a man she flirts with about loneliness and the unsatisfying nature of material things also evoke Sevda’s spiritual awareness and the concept of zuhd.

Figure 10.

The sea and the forest scene in The Night That Never Was (1989, 81 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

Şasa describes the Bengali director Satyajit Ray’s (1921–1992) film Pather Panchali (Song of the Road 1955) as “the poetry of trust in God (tawakkul)”, highlighting themes of poverty, spiritual wealth, patience, and reliance on divine will (Şasa 2010, p. 54). Tawakkul means trusting Allāh completely, surrendering to His will, and transcending worldly hardships through faith (al-Kalābādhī 1977, pp. 92–93; al-Sarrāj al-Ṭūsī 1960, p. 78). She asserts that the film embodies the vision of a saint and finds it significant that such a film, rich in mystical themes, originates from the East (Şasa 2010, p. 54). In Hear the Reed, Şasa underscores the concept of tawakkul through a painting that reads tawakkul (Figure 11). While the shaykh is struggling with a serious illness, this painting on the wall symbolizes his trust in God, submission, and patience. With this scene, Şasa draws attention to the function of Sufism in providing spiritual endurance during hardship and presents this painting to the audience as a symbolic indicator of this function.

Figure 11.

Calligraphy of tawakkul in Hear the Reed (2008, 95 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

Şasa also compares the film to the vision of the murshid, a spiritual guide in Sufism who exemplifies wisdom and moral virtue (Schimmel 1975, pp. 101–5). Rūmī describes the murshid as a doctor who heals spiritual ailments (Rūmī 2002, 3: 299). In Hear the Reed, the character of the doctor symbolizes this role. His calm and careful preparation of medicines reflects the murshid’s spiritual mastery, while his healing of patients parallels the guide’s role in curing the dervishes’ inner illnesses (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

The doctor in Hear the Reed (2008, 95 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

Şasa’s review of Erden Kıral’s (1942–2002) film Blue Exile (Mavi Sürgün) highlights the Mevlevi samāʿ—an audible and physically enacted form of dhikr (divine remembrance) in the Mevlevi order, characterized by ritual music and whirling as a means of spiritual remembrance and union with the divine (Şasa 2010, pp. 107–8)—as a ritual symbolizing creation and humanity’s return to God (Ankaravī 2008, pp. 115–39; Lewis 2000, pp. 461–64; Schimmel 1992, pp. 196–204). As in Blue Exile, Şasa visualizes the Mevlevi samāʿ ritual and whirling dervishes as a cinematic symbol of the Sufi journey (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

The samāʿ ritual in Hear the Reed (2008, 95 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

7. Cinema and Waḥdat al-Wujūd: Şasa’s Cinematic Vision Inspired by Ibn ʿArabī

Şasa’s illnesses, existential struggles, and accumulated experience in cinema provided her with a new perspective on ontological issues and offered her a fresh outlook (Badeci 2015, p. 49). In a letter, she openly expresses this influence, stating “Whenever I draw near to Sufi thought and the world of Ibn ʿArabī, I distance myself from material surroundings and daily events” (Kaplan 2015, p. 196). She credits her turn to Islam and Sufism entirely to Ibn ʿArabī (Şasa 2006, p. 97).

Şasa’s cinematic approach is deeply informed by Ibn ʿArabī’s metaphysics, which shaped her understanding of both existence and film. A former anti-Western Marxist for three decades, she eventually rejected Marxism for perpetuating dualism and division (Şasa 2010, p. 144). She credits her turn toward waḥdat al-wujūd with overcoming this fragmentation. Her intellectual and spiritual transformation brought her cinematic vision into alignment with Ibn ʿArabī’s concepts of dream (ruʾyā) and imagination (khayāl).

In her article “The Ontology of Images”, Şasa draws on waḥdat al-wujūd, describing the world as God’s dream and life as a gradual unfolding of that dream to achieve knowledge of the divine. Quoting the ḥadīth, “People are asleep; they wake up when they die”, she links imagination to truth, revelation, and inspiration. She challenges filmmakers with the question “Is cinema the product of imagination or dreams?” (Şasa 2010, p. 73).

According to the metaphysics of waḥdat al-wujūd, the world is a dreamlike realm in which humans sleep until death awakens them (Ibn al-ʿArabī 1980, pp. 119–27; al-ʿAfīfī n.d.b, pp. 99–102; Chittick 1989, pp. 115–21; Corbin 1997). In the Cerrahi order, to which Şasa belonged, dreams are viewed as signs of the dervish’s spiritual development. She often asked her shaykh, Safer Efendi, about the significance of dreams, to which he replied that they are a form of divine knowledge (Yola 1993, p. 417; Dal 2013, p. 45). For Şasa, cinema functions much like a dream—emerging from human imagination and bridging the material and spiritual realms. Inspired by the notion that “this world is a dream”, she uses mystical imagery to explore divine realities through visual expression.

Şasa’s Hear the Reed emphasizes the transience of life through scenes of death and the graveyard, likening the world to a temporary dream (Figure 14). Although worldly life seems permanent, it is temporary and keeps the soul busy with unnecessary things. In this context, the graveyard scenes are visual elements that depict the end of this dream and the transition to the ultimate reality, the afterlife. The poems recited at the film’s opening emphasize death and the world’s transience and present a perspective against ambition and desire.

Figure 14.

The graveyard in Hear the Reed (2008, 95 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

In “Islam and the Media”, Şasa contrasts Eastern and Western views on cinema using Ibn ʿArabī’s theory of divine names (Şasa 2010, p. 95). Ibn ʿArabī teaches that Allāh manifests in the world through His names and attributes, with each being reflecting a specific divine name, revealing the connection between God and creation (Ibn al-ʿArabī 1980, pp. 82–89); al-ʿAfīfī 1939, pp. 44–56; Chittick 1994, pp. 15–30; Chittick 1998, pp. 39–40). Şasa critiques Western cinema for reducing the material and spiritual realms to the physical, interpreting this as reflecting God’s majestic (jalālī) names like Subduer (al-Qahhār) and The Avenger (al-Muntaqīm). She argues that cinema can also embody God’s beautiful (jamālī) names, such as The Most Compassionate (al-Raḥmān) and The Most Merciful (al-Raḥīm) (Şasa 2010, p. 95).

Cinema can reflect the jamālī names to the audience through images and motifs. In Hear the Reed, Şasa treats the character of the shaykh in a way that reflects God’s names, al-Raḥmān and al-Raḥīm. Although the shaykh is ill, he continues to show mercy and love to the dervishes. God is infinitely merciful. In this film, the dervish’s progress on the path of truth can be associated with God’s name, al-Hādī (The Guide). Allāh guides His servants to the right path. In the film, the shaykh’s patience and tawakkul in his illness are embodied in a painting inscribed with tawakkul. The shaykh does not rebel against Allāh because of his illness; he surrenders to Him. These scenes can be interpreted as a reflection of the name al-Ṣabūr (The All-Patient). The shaykh’s illness and death depict Allāh’s names, al-Ḥayy (The Living) and al-Bā‘ith (The Awakener). The shaykh’s death emphasizes the eternity of Allāh and refers to the name al-Ḥayy. The name al-Bā‘ith also comes to the fore, as death means resurrection in the Hereafter.

The scenes of light streaming through the windows symbolize the name of Allāh al-Nūr (The Light), signifying that wisdom and divine inspiration illuminate everything (Figure 15). In Ibn ʿArabī’s thought, inspiration is realized through the name al-Nūr, and through it, truth is apprehended (al-Ḥakīm 1981, pp. 1080–81)

Figure 15.

The light in Hear the Reed (2008, 95 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

The chirping of birds and the harmony of the beings in nature emphasize the belief that there is beauty in everything God has created. This harmonious sound helps the dervishes to realize Allāh’s name, al-Jamīl (The Most Beautiful). Indeed, her shaykh, Safer Efendi, stated “Everything glorifies Allāh in the most beautiful way; the wind and even the church bell.” (Çakır 2015, p. 57). Many scenes in the film refer to the idea of waḥdat al-wujūd by reminding us of Allāh’s name, al-Wāḥid (The Only One). The whirling of the whirling dervishes around a single center and their chanting together symbolize the belief of tawḥīd.

In her article “Non-existence is Never Absolute”, Şasa critiques Turkish director Kutluğ Ataman’s (b. 1961) claim that “Non-existence is absolute”, challenging what she sees as a nihilistic stance (Şasa 2010, p. 111). Central to her rebuttal is the metaphysical principle of waḥdat al-wujūd, which posits that existence (wujūd) is absolute because it reflects God’s necessary and infinite being, whereas non-existence (ʿadam) is merely relative—an absence that exists only as potential (al-ʿAfīfī 1939, pp. 1–9; Chittick 1989, pp. 79–81). Şasa argues that in this framework, non-existence is not a force in itself but a trace, a faint shadow of divine attributes such as al-Raḥmān and al-Raḥīm. Were non-existence truly absolute, she contends, creation would not be possible, and evil would prevail (Şasa 2010, p. 111). For Şasa, this ontological vision—derived from Ibn ʿArabī’s metaphysics—ought to shape not only spiritual understanding but also artistic and cinematic expression.

In Hear the Reed, certain scenes vividly convey the concept of waḥdat al-wujūd, foregrounding Sufis’ longing for unity with God (Figure 16). In these scenes, the whirling dervishes function as potent symbols of detachment from the ego and the aspiration to enter into the presence of Allāh. Their circling movement—both around themselves and a shared sacred axis—signifies a return to a divine center and reflects the metaphysical idea that all existence revolves around and is ultimately subject to Allāh (Özcan 2004, p. 466). These scenes thus communicate a deeply spiritual message: all creation is encompassed by and oriented toward the divine.

Figure 16.

The whirling dervishes in Hear the Reed (2008, 95 min). Film still used for scholarly analysis under fair use.

8. Conclusions

Bringing a spiritual perspective to Turkish cinema, Şasa criticized the perception of modern cinema in the world in her films and books. Şasa dedicated her films to visualizing the teachings of Sufism, Rūmī, Ibn ʿArabī, and her shaykh Safer Efendi. She reflected on these teachings, such as zuhd, tawakkul, and waḥdat al-wujūd, inner journey, and the theory of divine names on the screen with audial and visual narratives.

Şasa sees cinema not only as an art form but also as a tool to benefit humanity. According to her, cinema is a unique tool for conveying society’s values, religious beliefs, moral virtues, and spiritual values. Şasa reacted to the superficial and materialistic films of her time, which emphasized modern life, and engaged in “visual activism” until the end of her life. In almost all the screenplays she wrote throughout her life, she rejected modernist paradigms that pushed the individual and society towards isolation and unhappiness. She tried to create a spiritual awareness and transformation in her audience by emphasizing humility, conviction, patience and benevolence. In this context, she made the most effort to visualize Sufi concepts and teachings.

Hear the Reed is Şasa’s most symbolically rich film. In this film, she visualized the doctrine of waḥdat al-wujūd and the tawḥīd by using the samāʿ ritual, whirling dervishes, and the nay as symbols. By skillfully integrating the rituals and musical elements of the Sufi tradition into her films, she invited her audience to live this spiritual experience. The opening scenes with the graveyards underline the transience of worldly life and the ultimate unity of all existence. Şasa’s contributions to visual culture also played a vital role in introducing Ibn ʿArabī’s teachings to a broader audience. She made the complex concept of waḥdat al-wujūd more tangible by illustrating it through visual and auditory symbols. She created a unique medium for conveying profound philosophical ideas by bridging metaphysical subjects with popular culture through cinema.

Tarkovsky was the most influential figure in Şasa’s cinematic language. Inspired by his perspective on cinema and his films, Tarkovsky’s approaches can be seen in Şasa’s films. As a matter of fact, like Tarkovsky, Şasa gives a vast space to the existential questioning and spiritual searches of the characters in her films. In My Friend the Devil, Şasa presents these quests and inquiries of the protagonist to the audience, and in The Night That Never Was, she writes the screenplay using a similar narrative.

Through her films, Şasa developed an alternative language to the modern cinematic narrative, contributing to the revival of a forgotten spiritual perspective and the quest for truth within society. As a screenwriter and writer, Şasa emphasized spiritual transformation by rejecting the dominant paradigms of the modern world and left a lasting mark on Turkish cinema by underlining the transformative power of cinema.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aksoy, Ahmet. 2014. Son Kuşlar’dan Yeşilçam Günlüğü’ne [From the Last Birds to the Yeşilçam Journal]. Mahalle Mektebi 18: 119–20. [Google Scholar]

- al-ʿAfīfī, Abū al-ʿAlāʾ. 1939. The Mystical Philosophy of Muḥyī l-Dīn Ibn al-ʿArabī. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- al-ʿAfīfī, Abū al-ʿAlāʾ. n.d.a. al-Taṣawwuf: al-Thawra al-Rūḥiyya fī l-Islām [Sufism: The Spiritual Revolution in Islam]. Beirut: Dār al- Shaʿb.

- al-ʿAfīfī, Abū al-ʿAlāʾ. n.d.b. Fuṣūṣ al-Ḥikam wa-l-Taʿlīqāt ʿAlayh [The Bezels of Wisdom and the Commentary on It]. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿArabiyya.

- al-Ḥakīm, Suʿād. 1981. al-Muʿjam al-Ṣūfī: al-Ḥakīm fī Ḥudūd al-Kalima [The Sufi Dictionary: al-Ḥakīm on the Limits of the Word]. Beirut: Dār al-Madā li-l-Ṭibāʿa wa-l-Nashr. [Google Scholar]

- al-Jurjānī, ʿAlī ibn Muḥammad. n.d. Kitāb al-Taʿrīfāt [The Book of Definitions]. Cairo: Dār al-Rayān li-l-Turāth.

- al-Kalābādhī, Abū Bakr. 1977. The Doctrine of The Sufis (Kitāb al-Ta'arruf: Li-Madhab ahl al-taṣawwuf). Translated from the Arabic of Abū Bakr al-Kalābādhī. Translated by Arthur John Arberry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- al-Kāshānī, ʿAbd al-Razzāq. 1996. Laṭāʾif al-Aʿlām [Subtleties of the Worlds]. Cairo: Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyya. [Google Scholar]

- al-Qushayrī, Abū al-Qāsim. 1914. al-Risāla al-Qushayriyya fī ʿIlm al-Taṣawwuf [The Qushayrī Epistle on the Science of Sufism]. Cairo: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿArabiyya al-Kubrā. [Google Scholar]

- al-Sarrāj al-Ṭūsī, Abū Naṣr. 1960. al-Lumaʿ [The Flashes]. Cairo: Dār al-Kutub al-Ḥadītha. [Google Scholar]

- Ankaravī, İ. Rusūhī. 2008. Minhacü’l-Fukara; Mevlevî Âdâb ve Erkânı & Tasavvuf Istılahları. Translated by Safi Arpaguş. Istanbul: Vefa Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Awn, Peter. J. 1983. Satan’s Tragedy and Redemption: Iblis in Sufi Psychology. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Badeci, Abdurrahman. 2015. Yuvası Aydınlanmış Hira Çocuğu [The Child of Hira Whose Nest Was Illuminated]. In Hayret Perdesini Temaşa [Contemplating the Veil of Wonder]. Edited by Serdar Arslan. Istanbul: İnsan Yayınları, pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bayraklı, Davut. 2016. Ayşe Şasa: Acı, Vuslat, Münzevi [Ayşe Şasa: Pain, Union, Hermit]. Mostar 141: 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, A. Asa. 1991. Media Analysis Techniques. California: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, William. 1989. The Sufi Path of Knowledge: Ibn al-ʿArabī’s Metaphysics of Imagination. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, William. 1994. Imaginal Worlds: Ibn al-ʿArabī and The Problem of Religious Diversity. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, William. 1998. The Self-Disclosure of God: Principles of Ibn al-ʿArabī’s Cosmology. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, Henry. 1997. Alone with the Alone: Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn al-ʿArabī. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Çakır, Adalet, and Dal M. Fahreddin. 2020. Dal, Safer. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi [Turkish Religious Foundation Encyclopedia of Islam]: Vol. EK-1. Ankara: TDV Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Çakır, Adalet. 2015. Evliya Kızı [The Daughter of a Saint]. In Hayret Perdesini Temaşa [Contemplating the Veil of Wonder]. Edited by Serdar Arslan. Istanbul: İnsan Yayınları, pp. 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Dal, Safer. 2013. Geydim Hırkayı: Safer Efendi’nin Sohbetleri [I Wore the Khirqa: The Discourses of Safer Efendi]. Istanbul: Dergah Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Debord, Guy, and Ken Knabb. 2002. The Society of the Spectacle. Canberra: Hobgoblin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Demirel Uyar, Ayşegül. 2015. Hayret Yaylasına Yolculuk [Journey to the Plateau of Wonder]. In Hayret Perdesini Temaşa [Contemplating the Veil of Wonder]. Edited by Serdar Arslan. Istanbul: İnsan Yayınları, pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Elsaesser, Thomas, and Malte Hagener. 2009. Film Theory: An Introduction Through the Senses. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, Antoon. 1993. A Note on the Psychology of Dhikr: The Halveti-Jerrahi Order of Dervishes in Istanbul. Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis 15: 53–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guénon, René. 1975. The Crisis of the Modern World. London: Luzac and Company Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Gündüzöz, Güldane. 2008. Mevlevi Sema Töreninde Yer Alan Sembollerin Anlamları [The Meanings of Symbols in the Mevlevi Sema Ceremony]. Dinbilimleri Akademik Araştırma Dergisi [Academic Journal of Religious Studies] 8: 109–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gürer, Betül, and Hamide Ulupınar. 2023. Tasavvufi Sembolizm Açısından Mevlevi Sema Ayini [The Mevlevi Sema Ritual in Terms of Sufi Symbolism]. Atatürk Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi İlahiyat Tetkikleri Dergisi [Atatürk University Faculty of Theology Journal of Theological Studies] 59: 110–19. [Google Scholar]

- Huxley, Aldous. 1947. The Perennial Philosophy. London: Chatto and Windus. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ʿArabī, Muḥyī al-Dīn. 1980. The Bezels of Wisdom. Mahwah: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- İşler Sevindi, Meltem. 2018. Ayşe Şasa’nın Sinemasal Düşüncesine Eleştirel Yaklaşım [A Critical Approach to Ayşe Şasa’s Cinematic Thought]. Master’s thesis, Marmara Üniversitesi, Istanbul, Turkey, July 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Yusuf. 2015. Üç Ayşe Şasa: Ve Düşünür ve Sanatçı ve Öncü [Three Ayşe Şasas: The Thinker, the Artist, and the Pioneer]. In Hayret Perdesini Temaşa [Contemplating the Veil of Wonder]. Edited by Serdar Arslan. Istanbul: İnsan Yayınları, pp. 169–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, İsmail. 2020. Dağ Ne Kadar Yüce Olsa: Portreler 2 [No Matter How High the Mountain: Portraits 2]. Istanbul: Dergah Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Kılınç, Nurgül. 2011. Mevlevi Sema Ritual Outfits And Their Mystical Meanings. Humanities Sciences 6: 809–28. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2018. Content Analysis An Introduction to Its Methodology. Singapore: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Franklin D. 2000. Rūmī: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teaching and Poetry of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī. Oxford: Oneworld. [Google Scholar]

- Lings, Martin. 1975. What Is Sufism. London: George Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 2002. The Visual Culture Reader. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 2016. How to See the World: An Introduction to Images, from Self-Portraits to Selfies, Maps to Movies, and More. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Özcan, Nuri. 2004. Mevlevi Ayini [The Mevlevi Ritual Ceremony]. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi [Turkish Religious Foundation Encyclopedia of Islam]. Ankara: TDV Yayınları, vol. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Gillian. 2016. Visual Methodologies An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rūmī, Jalāl al-Dīn. 2002. The Mathnawī of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī. Translated by Reynold A. Nicholson. Tehran: Suʿād. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel, Annemarie. 1975. Mystical Dimensions of Islam. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel, Annemarie. 1992. I Am Wind, You Are Fire: The Life and Work of Rūmī. London: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel, Annemarie. 2001. Rūmī’s World: The Life and Work of the Great Sufi Poet. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Schuon, Frithjof. 1993. The Transcendent Unity of Religions. Wheaton: The Theosophical Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Şasa, Ayşe. 2006. Delilik Ülkesinden Notlar [Notes from the Land of Madness]. Istanbul: Timaş Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Şasa, Ayşe. 2010. Yeşilçam Günlüğü [Yeşilçam Diary]. Istanbul: Küre Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Şasa, Ayşe. 2012. Bir Ruh Macerası [A Spiritual Adventure]. Istanbul: Timaş Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Tanman, M. Baha. 2007. Nureddin Cerrahi Tekkesi [The Nureddin Cerrahi Lodge]. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi [Turkish Religious Foundation Encyclopedia of Islam]. Ankara: TDV Yayınları, vol. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Tarkovski, Andrey. 2008. Mühürlenmiş Zaman [Sculpting in Time]. Istanbul: Agora Kitaplığı. [Google Scholar]

- Tarkovski, Andrey. 2009. Şiirsel Sinema [Poetic Cinema]. Istanbul: Agora Kitaplığı. [Google Scholar]

- Ural, Zeynep. 2015. Beni Mutlu Eden Filmlerim Değil, Kitaplarım [It Is Not My Films but My Books That Make Me Happy]. In Hayret Perdesini Temaşa [Contemplating the Veil of Wonder]. Edited by Serdar Arslan. Istanbul: İnsan Yayınları, pp. 251–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yalsızuçanlar, Sadık. 1997. Düş, Gerçeklik ve Sinema [Dream, Reality, and Cinema]. Istanbul: İz Yayıncılık. [Google Scholar]

- Yola, Şenay. 1982. Schejch Nureddin Mehmed Cerrahi und sein Orden: 1721–925 [Shaykh Nureddin Mehmed Cerrahi and His Order: 1721–1925]. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Yola, Şenay. 1993. Cerrahiyye [The Cerrahi Order]. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi [Turkish Religious Foundation Encyclopedia of Islam]. Ankara: TDV Yayınları, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).