Abstract

Religious symbols and figures are gaining new life in popular culture. Reinterpretations of symbols rooted in the visual arts tradition are appearing in film, TV series and short audiovisual forms presented on the Internet, especially on social media. This also applies to angels, to which the author’s research would be devoted. This article discusses images of “secular angels”, decontextualized religious symbols, popularized throughout the 20th and 21st centuries in the visual media of Western culture. From the rich research material, the most characteristic images are selected for discussion and interpretation and subjected to interpretation in the spirit of discourse analysis. The images of modern “angels” in the texts of popular culture refer not so much to their biblical prototypes, but to the moral condition of man in consumerist, individualistic societies focused on living for pleasure. Film, TV series and Internet images of “angels” also show the controversies and social problems (such as racism) faced by contemporary Western societies.

1. Introduction

The main objectives of this essay are to explore several dimensions of the transformation of the image of angels in popular culture, primarily the infantilization of the image of the angel in connection with the development of consumer society and the Americanization of the message of angels in 20th-century audiovisual culture, and, in contrast, the “apocalyptization” of their image in the 21st century, which results in post-apocalyptic imagery. Topics such as the gendering and sexualization of angelic images and moral ambiguity in the chosen visual presentation of angels are also included1. The inspiration for this article arose from questions such as the following: what is the role of angelic imagery in contemporary culture? The goal of this essay is to demonstrate how popular culture has transferred angels from the religious dimension to the secular sphere based on examples from visual culture. The point is that secular angels in popular culture have also undergone an evolution, through the humanization of these figures, making angels flawed and, therefore, close to humans; to images rooted in “fidelity to Scripture” narratives; and to visions of both benevolent angels, as well as menacing angels of the apocalypse that herald the end of the Earth and the coming of the new world. Due to the fact of convergence in culture2, all angelic images in various forms—disseminated in religious oil painting3, church sculpture (in the form of photographs or as film elements), feature films and documentaries, as well as in social media clips—coexist as a cultural content, without forming a coherent narrative or a unified ideology.

Literally, as St. Augustine maintains, “an angel is a function, not nature”, it is neither a figure, character, or individual personality (cf. Bowker 2004, p. 43). The differences in the understanding of angels—good and fallen ones—between Judaism and Christianity are quite significant. Both traditions interpret certain passages of the Old Testament Scriptures4 differently. This essay does not aim to resolve theological nuances but rather to describe the angelic imaginarium in contemporary visual popular culture. In the art of letters, visions of angels, their tasks and hierarchy were considered by theologians and philosophers (Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, and after him, for example, St. Thomas Aquinas, called “the Doctor Angelicus”), poets and writers—Dante, John Milton and others. In contrast, the angel as a function, as a messenger, may have been difficult to visualize in the fine arts. In the Judaic tradition, according to the second commandment5, personal representations of God and heavenly beings are not allowed. In the Christian tradition, certain elements of the angel’s image such as wings or a halo — are fixed. All other features of the visualization—age, sex, race, facial characteristics with facial expressions, size, robes, as well as their form and color—have not gained a single “canonical” interpretation, applicable to all artists. The wings themselves give the angelic character a heavenly appearance. The matter becomes more complicated when different types of angels are presented in popular narratives. Following the traditional description is not always easy, e.g., in the literature, nine angelic orders are given by Christian tradition thanks to the treatise on The Celestial Hierarchy by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite6, and other names such as guardian angel, angel of vengeance, angel of doom, etc. are in usage, which may confuse the audience.

Although biblical accounts do not always mention angels’ wings, winged angels already dominate in fine arts representations. Rare cases7 of wingless angels from the first centuries of Christianity (known, for example, from the Roman catacombs) were not conducive to understanding the meaning of the image (Ward and Steeds 2005). The symbolism of the representation of angels was only developing at the time. There are no known images that were destroyed during the iconoclasm (Besançon 2000). However, despite waves of iconoclasm, since the 5th century, wings have become a permanent feature of angels. In the case of the three archangels mentioned by name—Michael, Gabriel and Raphael—a male image was also adopted, assigning them that gender. Other types of angels are depicted as either male or female, and sometimes androgynous. Corporeality is not their essential feature; and ethereal robes seem to indicate the ephemeral and spiritual nature of these divine beings. In contrast, angels in popular culture gain a more tangible corporeality (thanks to the actors who play their roles), and in audiovisual productions of the 20th and 21st centuries, there is no single, universally recognized image. Film angels, who blend into everyday life of modern people are most often wingless, although they occasionally present these wings to prove the divine origin of their mission.

The form of angel wings is deeply symbolic; in fine arts, they most often resemble eagle or swan wings. According to some calculations, the location of such wings on the shoulder blades would actually prevent these angels from flying8. The size and shape of the wings in angelic visualizations has evolved further with the involvement of AI in the creation of angelic images9. In fine arts, particularly historical iconography, even the color of angelic wings has not been standarized. For example, the angels of Giotto, one of the first geniuses of religious painting, had wings (as well as angelic robes) that were sometimes white, sometimes green or red, or even multi-colored. Other artists followed a similar path. Visualizations of angels from the higher angelic orders (seraphim and cherubim) were rather ambiguous and tended to present variants of heads or figures with six or four pairs of wings10.

In fine arts—especially in drawing, painting and sculpture—angelic images have evolved from ancient times to the present day with the changing artistic styles and character of the era. Extensive studies have also been written on these subjects (Berefelt 1968; Buranelli et al. 2007; Giorgi 2003; Jaritz 2011; Ward and Steeds 2005). Tracing the transformation of the image of the angel in Western culture is a very extensive task, far beyond the scope of this article. Thus, selected contexts of angelic and para-angelic imagery will be examined. Furthermore, trends in the aestheticization of angelic images, drawing from many cultural areas and ethnic traditions, are significant. In addition, the transformations of religiosity resulting from the spread of New Age (Heelas 1996; Baer 1989; Heelas and Woodhead 2005) and apocalyptic movements symptomatic of the turn of the century will be considered.

The research material—physical objects and virtual artifacts—comes from popular culture, which is a dynamic, multidimensional and multinational creation, full of contrasts and paradoxes. These include disconnected/related and similar/contradictory ideas, standardized versus original products, etc. In popular culture, especially in social media, one can find both works of art by established, respected artists as well as amateurs (Danesi 2008; Keen 2007). However, most contemporary formal and thematic transformations are taking place in American culture, spreading intensively across the globe. Concepts concerning cultural imperialism and the transformation of religiosity in the modern world will determine the theoretical framework of this essay. This essay is written from a sociology of culture perspective11. Methods of discourse analysis and techniques from digital humanities will be used to analyze material collected online12 (e.g., visual and audiovisual materials from platforms like Instagram, YouTube13 or TikTok).

2. The Infantilization of Angelic Iconography

Cultural studies on angels and the hereafter discuss beings and angel-like spirits from non-European cultures14. Among them are presented as winged creatures from Egyptian tombs, as well as depictions of hybrid creatures from the preserved heritage of ancient Persians, Indians and other peoples from all regions of the world. It is usually recognized that the wings here symbolize the role of these beings (messenger and intermediary). Such characters are present in all mythologies of the world. In the aforementioned books, significant attention is devoted to the presentation of Old Testament and Christian ideas about angels and their hierarchy.

Particularly interesting are the “genetic” connections of various angelic forms in popular culture: Christian beliefs and their representations coexist with pre-Christian myths and fairy tales from various parts of the world. Religious symbolism coexists with secular embellishments. Sometimes, the connections are much deeper and more dramatic—one image may be a hybrid of these different representations15. These forms create an iconography that includes both the guardian angel from religious pictures given to children for baptism, during religious lessons, or as a souvenir of the traditional “carol service”; various forms of secular “angelic” figures with ambiguous meaning and symbolism (Figure 1); as well as mischievous little angels (which seem to be hybrids of elves and cupids).

Figure 1.

A set of kitchy angel-like gadgets. Photo: Author.

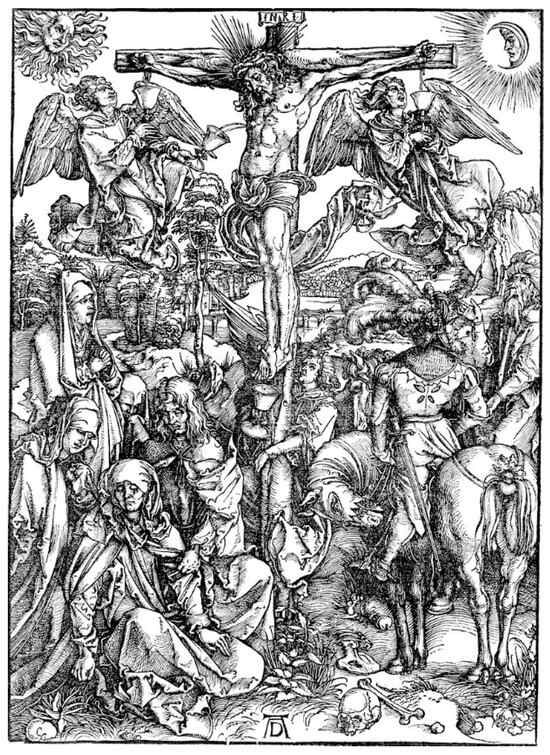

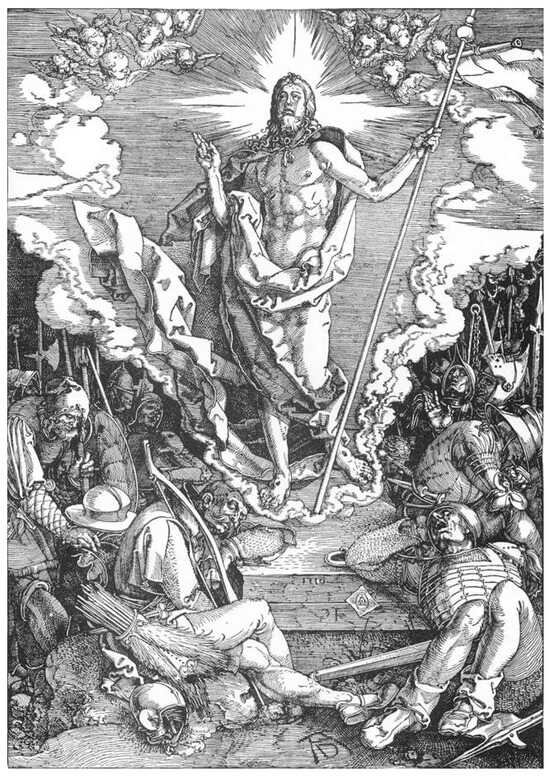

Sometimes in audiovisual culture, there is a contradictory image of a “ghostly angel,” as in the sitcom series Teen Angel (1997–1998), in which a deceased teenager appears as a ghost; however, there is not much “angelic patience” in him, as he is sometimes malicious and certainly not heavenly. The aforementioned ambiguities of angelic portrayals are not just the result of modern transformations marked by the New Age. Angelic depictions do not form a coherent story. For example, “childlike” angels have been known in Christian iconography for centuries, such as those depicted in a series of woodcuts in Albrecht Dürer’s Great Passion (1497–1510), which includes both adult and child angelic figures (Figure 2 and Figure 3 below).

Figure 2.

A plates from Great Passion (known also as Large Passion) by Albrecht Dürer with the ”adult” type of angels.16

Figure 3.

A plates from Great Passion by Albrecht Dürer presents bodyless angels of childlike faces.17

In the Preface to the 1961 Edition of The Screwtape Letters, C.S. Lewis ironically comments on the transformations of angelic portraits:

…Christian theology has nearly always explained ‘the appearance’ of an angel in the same way. It is only the ignorant, says Dionysius in the fifth century, who dream that spirits are really winged men.

In the plastic arts, these symbols have steadily degenerated. Fra Angelico’s angels carry in their face and gesture the peace and authority of heaven. Later come the chubby, infantile nudes of Raphael; finally the soft, slim, girlish and consolatory angels of nineteenth-century art, shapes so feminine that they avoid being voluptuous only by their total insipidity—the frigid houris of a tea-table paradise. They are a pernicious symbol. In Scripture, the visitation of an angel is always alarming; it has to begin by saying “Fear not”. The Victorian angel looks as if it were going to say “There, there”.(Lewis 2013)18

Art historians would probably be outraged at such simplifications; however, for the purposes of this study, Lewis’s take is sufficient. A clear tendency to infantilize the image and transform its function is marked. An example of infantilization can be seen in the following account of “juvenile” angels: in the fifteenth-century depiction proposed by Crivelli (Figure 4), the angels, although depicted as children, do not trivialize the scene and do not distract from the main theme—suffering, death, grief. Instead, they express the mood of the scene. On the other hand, the “decorative soap” angel is detached from religious context; it could just as well be a cat or dog with an adorable face. Infantilization, i.e., emphasizing fun, innocence and pleasure (cf. Barber 2007, pp. 19–20; Wilk 2001), serves consumerism as best as it can: angels sell well.

Figure 4.

Carl Crivelli’s painting The Dead Christ Supported by Two Angels, 1470–1475, National Gallery, London, Great Britain.19

A separate “species” is the advertising angel, most often frivolous in a secular context. This represents a separate problem, which likely needs to be elaborated and reinterpreted. Pioneering works in the field on the connection between religiosity and advertising are already exploring this topic (e.g., Turek 2002). Images of angels emphasize lightness and purity (in laundry detergent ads) but also wink at the viewer. There are angels that are lazy, sleepy and restless—more like obese monks from satirical stories than miraculously perfect beings. In general, “creatures with wings” are used quite freely in this sphere of popular culture. Sometimes, their sexuality is emphasized, making them unearthly, beautiful and seductive. Consumerism encourages simplification, and here, too, one can see the trivialization and infantilization of angelic imagery, even in relation to the already simplified representations of the 19th century.

The catalog of pop culture images of God’s beings would be incomplete without including film and television angels. Images have been prevalent in Western cinematography since the advent of film. Thus, the topic is very broad and inconsistent. The images of angels in religious films correspond to the ancient records of holy books, and their features and functions are more important than their graphic representation. In stories about the lives of the saints, in religious films on the story of salvation—traditionally aired before Christmas—angels are bright figures. Some documentaries also explicitly deal with religious themes, sometimes trying to undermine them20. In film titles, “angel” does not foreshadow religious content or the presence of holy angels in the narrative. For example, Face of an Angel (dir. Tadeusz Chmielewski, 1970) takes place in a children’s concentration camp, and the film Drunken Angel (dir. Akira Kurosawa, 1948) is a socio-psychological drama from post-war Japan. The film images are also simplistic, but their role is somewhat different from the infantile functions of angelic gadgets or postcards.

3. The Americanization of Film Depictions of the Angel

This part of the text will focus on selected productions, characteristic of different eras of cinematography, such as The Kid (dir. Charles Chaplin, 1921); It’s a Wonderful Life (dir. Frank Capra, 1946); Der Himmel über Berlin (dir. Wim Wenders, 1987) and its American version, City of Angels (dir. Brad Silberling, 1998); Dogma (dir. Kevin Smith, 1999); Michael (dir. Nora Ephron, 1996); and selected TV series. In the aforementioned films and TV series, angels take human form and attempt to help people—and often, that is where the similarities with biblical angels usually end. Moving closer to our era are films like Constantine (dir. Francis Lawrence, 2005); Angels and Demons (dir. Ron Howard, 2009)—a film based on Dan Brown’s novel; or the TV series Lucifer (2016–2021).

Human or Angel?

- “Death makes angels of us all…

- And gives us wings

- Where we had shoulders

- Smooth as raven’s claws21”

- (Feast of Friends, Jim Morrison)

A popular stereotype is to call someone an “angel” if they have a good heart (or are nice and tender toward us). A second stereotype is connected with death—just like in the Jim Morrison’s poem—after death, we inevitably become angels. The aforementioned films speak openly about death; in the TV series “with angels”, there are more often difficult scenes, such as the death of patients during surgery, or as the result of an accident, as in City of Angels. However, the fate of man after death is specifically understood here, as stereotypical motifs are reproduced. There is an assumption that man, after death, passes into a higher state and experiences a kind of “evolution” to an angelic form22. In the public consciousness, such thinking is quite popular. For example, on some graves of young children, one can find echoes of this belief: the inscription “He/she enlarged the circle of angels” can be found in children’s sectors in a lot of European cemeteries in the 21st century as well. The persistent belief in the popular imagination that a person becomes an angel after death appears in many films, starting with The Kid in 1921. This idea also appears in movies, e.g., in the abovementioned American film It’s a Wonderful Life. In the last one, “a second-class angel” admits that he is wearing the suit that his wife dressed him in for the funeral. The angel, who turns out to be such a deserving man, is the guardian angel of George, the main character. The film shows the spirit of solidarity of the residents of a small town, opposition to exploitation and the collective spirit of building together—not so much the country, but the prosperity of the local community.

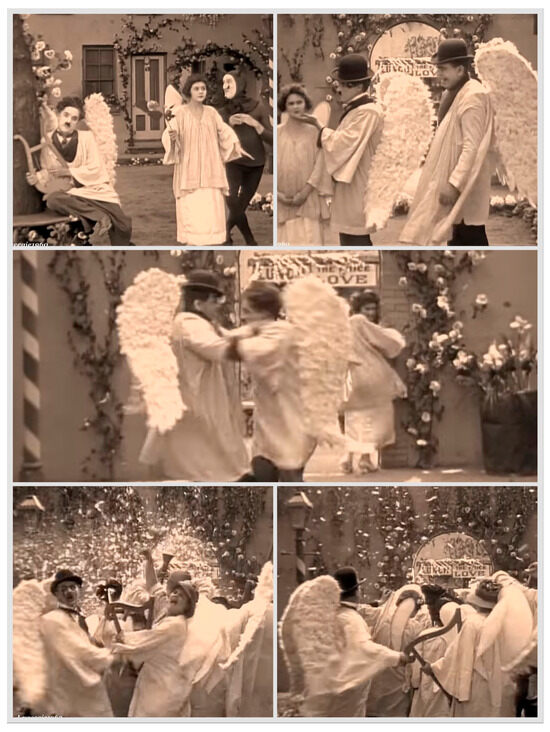

Let us focus for a moment on the film The Kid, in which the portrayal of heaven seems to serve as a model for later productions. The protagonist of the film dreams that he went to Dreamland, where, in the appropriate store, he purchases accessories such as wings and a palm tree (well, even in heaven, nothing is free, illustrating the expansion of consumer society, the consumer lifestyle and consumer practices that transcend worlds). Heaven does not seem very different from his everyday life: our hero lives in a poor neighborhood and meets the same neighbors and children, as well as familiar policemen. The atmosphere is decidedly non-metropolitan, non-urban—idyllic and pleasant. However, this paradise is disrupted when the devil, also traditionally depicted (horns, tail and a black outfit), breaks in and attempts to convince citizens to partake in evil, bringing along temptations, seduction and jealousy (Figure 5). The evil one manages to cause conflicts, including a fight, during which angelic feathers fall from his wings, finally concluding happily when the dream breaks. Heaven is dull; it is associated with passivity; and as Alexis de Tocqueville suggested, a democratic society such as in the U.S. should fear passivity and weakness in its citizens (de Tocqueville 2006, vol. 2). One may wonder to what extent the fear of passivity or inaction is inherent in the American ethos, or whether it is typical of capitalist societies in the productive stage of development. In consumer societies, citizen passivity is the order of the day (cf. Barber 2007, passim; Fromm 1968, p. 123; Schor 2004). However, such a vision of paradise is resented there as well.

Figure 5.

Collage based on the movie The Kid: the conflict between the “angels”23.

The addition of evil in an attractive form can be among the key factors in the success of film and television narratives. Thus, it is worth mentioning that audiovisual portrayals of angels of darkness are identified with Satan and called devils or demons; popular imagination rarely calls them fallen angels. In turn, they are often much more attractive than angels. This also applies to visions in other cultural fields, as C.S. Lewis discusses: “The literary symbols are more dangerous because they are not so easily recognized as symbolical. Those of Dante are the best. Before his angels we sing in awe. His devils, as Ruskin rightly remarked, in their rage, spite, and obscenity, are far more like what the reality must be than anything in Milton. Milton’s devils, by their grandeur and high poetry, have done great harm, and his angels owe too much to Homer and Raphael. But the really pernicious image is Goethe’s Mephistopheles. It is Faust, not he, who really exhibits the ruthless, sleepless, unsmiling concentration upon self which is the mark of hell. The humorous, civilized, sensible, adaptable Mephistopheles has helped to strengthen the illusion that evil is liberating” (Lewis 2013)24. This idea can be similarly applied in films. For example, in the old 1926 film Faust (dir. F. W. Murnau, 1926), Satan is an awe-inspiring but appealing creature. The same vision was propagated almost a century later in the series Lucifer (2016–2021). Film angels of the late 20th century who remain in God’s service often have “demonic” qualities (e.g., they rebel against God). These traits are downplayed or even valued as markers of individualism. Rebellion is attractive, and the wayward angel becomes a peculiar hero for modern man, for whom precepts are a sign of enslavement (cf. Fromm 1994), while morality is detached from Christian spirituality or any spirituality, with the ethical measure being man himself (cf. Rand 1964). Rebellion or independence? Independence, so prized in American culture, is often popularized—in sometimes surprising forms—globally.

In turn, in many narratives, a very special vision emerges: the angel is depicted as “a man of success”25, where earthly success leads to God (both—angels and human beings) and to success in the next life, fulfilling God’s commands. The road to success leads through work and fulfilling missions. For example, in the movie It’s a Wonderful Life, the previously mentioned “second-class angel, without wings” seeks to “earn” his wings by helping the protagonist of the film (saving him from committing suicide). Audiovisual angels, however, simultaneously distort the religious message. If even angels have to “try”, how can one understand God’s unconditional love for humanity? It is highlighted that these angels are imperfect and that they undergo development. A similar portrayal is found in the series Touched by an Angel26 (1994–2003), where an angel sometimes cries, makes mistakes in judgment and makes wrong choices. According to Scripture, in God’s word, angels are perfect and endowed with graces from the moment of creation (cf. CCC 1993, p. 330). They do not have to achieve anything and do not have to earn anything. In contrast, the cinematic image is rooted in the culture of success associated with American role models (cf. Grzeszczyk 2003, pp. 25–44; Wyllie 1966). Merit, work and success are typically earthly values that ensure a person’s happiness.

Besides, humanity is a fascinating concept for film angels. For example, in the film Der Himmel über Berlin and its American remake City of Angels, angels circulate among people, listen to their thoughts, enjoy sitting in the library and so on. A few of them decide to transform and become human (an angel must commit suicide and fall from high to the ground). This goes against the theological understanding of an angel. An angel cannot long to be someone else; he loves his position. As a perfect being, he cannot be dissatisfied—this is a satanic trait; it is also devilish to refuse to cooperate with God.27 Sensuality is mysterious and appealing to angels because it is inaccessible. And, to be human is to experience the world through the senses: in the film City of Angels, Seth, an angel who, through the aforementioned fall to Earth, underwent a transformation into human form, in conversation with his fellow angel, rejoices that he has exchanged eternity for sensory impressions. Even after the death of the woman for whom he gave up being an angel, when asked by a colleague, “was it worth it?” [to become a man], Seth responds that “he would have preferred the one time he could smell her hair, just one kiss, just one touch—the tinkle of her hand—than a whole eternity without it.” So, this is a clear glorification of corporeality, the swap of immortality for sensuality seems both Faustian and anti-Faustian at the same time. Perfection, spirituality and consent to God’s plan are not as appealing and important as primitive life in bodily form, finite and full of suffering. An appreciation of experience and belief in man, who here on Earth achieves his fullness through individualism, entrepreneurship and courage (especially understood, as will be discussed later), can be considered as the “Americanization” of the film’s message (cf. Rollin 1989).

4. Sexuality and Gender of the Angel

Gender is the most difficult depiction here, for according to Christian understandings, a being who is made up of pure spirit and intelligence is devoid of human weaknesses. Angels have no gender, which is difficult to convey in their depictions. In Western paintings, there seem to be more angels whose appearance is a mixture of both genders. On the other hand, in fine arts and film, fallen angels in the form of demons and devils, if they are not inhuman monsters, have a clearly marked male gender. For example, in the film The Exorcist (dir. William Friedkin, 1973), the demon is also of the male gender, and a large phallus in one of the film’s depictions confirms the gender and entanglement of the angels of darkness in violent sexuality and impurity.

An unusual depiction, then, are the above angels, painted on the vault in the church of the Jesuit Fathers in Kalisz (Figure 6). Here, the gender is very clearly marked, the bearded angels carry the word of God along with other intercessors of the Lord—apostles and saints.

Figure 6.

Fragment of an 18th century polychrome fresco by Valentine Zebrowski on the vault of the Church of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Kalisz, Poland. Photo: Author.

In audiovisual messages, on the other hand, the imagery is not always the “houris” or undefined figure mentioned by C.S. Lewis; here, the angels have a specific gender. In the movies It’s a Wonderful Life, City of Angels (as well as in its German prototype, Der Himmel über Berlin) and in the series Highway to Heaven (1984–1989), the angels are men. In the TV series Touched by an Angel, on the other hand, in the permanent angel team, one angel has taken a male form, two others appear in female forms, one of whom is dark-skinned. The male angel has the difficult task of carrying people “to the other side”.

In contrast, in the TV miniseries Angels in America (2003), which portrays the problems of AIDS patients and the homosexual community, the angel, as seen by a man suffering from AIDS, is a hermaphrodite. He not only reveals his sexuality but also uses it, taking off his robes and copulating with a mortal man. This angel is also ambiguous in image, just like the biblical angels. He inspires trepidation, as well: at times, he is a luminous figure (with impressive white wings), but at other times, he is angry, taking on the hues of the “angel of darkness”, appearing in a dark blue “version” (with white only marked on the tips of his wings). In this “version”, the angel, in turn, indulges in lesbian love.

Sensuality associated with gender gives satisfaction, as angels fit in the pursuit of pleasure and carnal pleasures. Gender deepens the connection to the world of sensuality. The masculinity of the angel awakened love for the earthly woman in Der Himmel über Berlin and City of Angels. And, if an angel wants to be a man, it means that it is excellent to be a man. For modern man, the message is simple: an angel is actually one of us, with the same needs, longings, flaws and sins as humans. Success for an angel is to remain on Earth, to carry out his will, even against God’s plans. In the case of these angels, independence and individualism count, as well as the pursuit of happiness, specifically earthly happiness (which is typical of the American set of values; cf. Bannister 1972). The narratives also suggest an inferior ideal and an aversion to an unknown “eternity”.

5. Moral Ambiguity of Popular Imagery

Angelic missions are related to angels carrying out tasks in relation to humans, thereby carrying out God’s commands. However, in cases where angels obediently carry out missions, there are some notable pop cultural distortions. Even the afflicted archangel Michael (in the movie Michael) had a specific task: “It’s a difficult thing—to return a man’s heart…,” he sighs. Postmodern ambiguity does not serve the uniformity of the image. Film angels are very active and disregard scripture; they appeal to God but sometimes commit transgressions, while also focusing on earthly matters. In the movie It’s a Wonderful Life or in the TV series Touched by an Angel, angels taking human form are companions, guardians, and advisors (guardian angels), or messengers who direct human destiny by guiding people in their missions. In the latter series, beings sent from heaven not only perform therapeutic functions—talking to people who are at pivotal points in their lives—but also try to stop them or persuade them to take certain actions. According to biblical tradition, an angel, as a messenger, only prompts and gently supports a person; they are not pushy. The angel exemplifies the power and goodness of God.

Sometimes, these angels talk about the “boss”, i.e., God, but they are reluctant to talk about the cross and salvation. After all, the cross is “so depressing”, as a Catholic Church cardinal says in the ironic narrative of the movie Dogma. Angels tell people that God loves them, assuring them that “it’s going to be alright” (which is a typical slogan of positive thinking inherent in American optimism).

These angels—concrete and very substantive—appear at difficult moments in a person’s life, intervening in their fate. In the movie It’s a Wonderful Life, this is done by showing the possible consequences of a wrong decision that the film’s protagonist might make (he is considering suicide). In the series Highway to Heaven, the angel Jonathan Smith, while carrying out his mission, is accompanied by an earthly helper, burdened with many defects and lost in life. Often, too, the angel’s efforts disturb the physical laws of the functioning of earthly reality, such as the unusual rate of plant growth in one episode. In order to carry out a plan that will lead to a change in a person’s fate, the angel performs tricks (they can hardly be called “miracles”), including causing minor inconveniences or obstacles (e.g., someone’s car engine breaks down, someone cannot catch a cab, etc.), which influence an individual’s decision. The angel thus forces the person to change their mind, behavior and actions. In this sense, the angel does not merely benevolently support and accompany the individual but rather steers their life. What is noteworthy is that the series is dominated by a realistic “life-like” approach to problems: sorrow is part of our lives; not everything can be fixed in this life; and much depends on us, but also on the help of others. The series tries to revive the spirit of community in a culture of commercialism and individualism28.

The individualism of angels in the audiovisual messages in question signifies a celebration of diversity, independent thinking and independence (including from God), while simultaneously accepting an ethical code full of contradictory values. American individualism is one of the important yet repeatedly criticized determinants of U.S. society (cf. Grzeszczyk 2003, pp. 35–38; Fischer 2008; Lasch 1991). In many scenarios, angels do something against God’s will; they have their own will, which is, after all, “better” because it is closer to life than a distant God. Sometimes, they do something without consulting “upstairs”. They see man’s suffering and his bad choices, which are reduced to mortal misery and death in the narratives. Eternal life is most often not mentioned, with the emphasis placed on our earthly existence and the order of things in temporal and ordinary life and not the “supernatural” world beyond.

Angels in films of the turn of the century usually wrestle with God, are rebellious and do not like everything. Therefore—according to theological findings—they are automatically on the side of darkness. However, the message of many of these productions is not aesthetically and ethically clear. The moral indifference or leniency towards human acts of one side of the angelic spectrum is counterbalanced by the harshness and vengeance of the other group of angels. Angels themselves are also weak characters, or to put it religiously, sinful. Undoubtedly, they are more perfect beings than humans, but the fact of their privilege, wisdom and greater abilities—including supernatural (or paranormal)—does not free the cinematic celestial creatures from the flaws typical of humans when they take on earthly human forms.

Wingless angels are typical as well in Western imaginary. A good example of this is the film Michael, made in the convention of not so much morality as comedy. The film portrays the archangel Michael in an earthly form, given over to sensuality. Archangel Michael’s behavior shows an utter disregard for the conventional values of angels, unconcerned about the health consequences of using various substances and stimulants—he smokes, drinks and consumes large amounts of sugar. He is interested in the world in the “mega” version (he absolutely must see the “biggest roll of twine”, the biggest this or that—America in the record version). In addition, he constantly violates the Decalogue; he is also unfamiliar with SALIGIA, the Latin name for the seven deadly sins, especially gula—gluttony (besides, good manners are not his strong point, as he eats very indecently)—and luxuria—debauchery. In addition, he uses violence. While in a bar, he gets into a brawl, shouting “Battle!” and even confronts a bull grazing by the roadside. Jonathan Smith, the angel from the series Highway to Heaven, is also characterized by his belligerent temperament; he gets into a brawl in a bar as early as the first episode, standing up for his future sidekick.

Archangel Michael of the movie Michael, however, is loyal to his world and also emphasizes “I do not criticize other angels”. Other film angels, on the other hand, have typically human flaws: they are jealous and spiteful and criticize and laugh at the failures of others. It is a good example of such humanization of the angelic world in the movies. By contrast, in the film Dogma, the angels banished from heaven openly criticize each other: “Sodom and Gomorrah? You started a few fires, and that’s it”, Loki29 hears from a colleague. Meanwhile, the angel of destruction explains how difficult it is to pour tar on screaming people and concludes: “genocide and soccer are damn exhausting”. For “angelic” accessories, the film adds a gun.

Indeed, in the movie Dogma, an important motif of angelic activity is anger and revenge: banished from heaven for refusing to obey an order, the angels track down the irregularities of social life. These “angels” are also rebellious, having broken free from the “heavenly” leash. The film is very ironic and entertaining, and in the credits before the screening, the director urges the audience not to take the content presented in the film seriously: “…do not take this film seriously. And remember that God also has a sense of humor, otherwise he wouldn’t have created the pecker”.

The confusion of moral codes promoted in these films, however, can lead to the ridicule of religiosity, especially since, on the one hand, the angels point out hypocrisy (“hypocritical even before themselves”), sins and human transgressions, and the evils that people cause (idolatry, marital infidelity, incest, raping children, disrespect for parents, etc.), and such accusations could be found in many a sermon by Christian clergymen. On the other hand, the accusation is followed by retribution and punishment, as seen during the film studio’s board meeting, where the angel Loki shouts “Faith, only faith!” while shooting at the previously accused people. The joyful background music reminds us of the humorous convention in which the film was made. It also changes the tenor of the previous accusation by making it part of the game, especially since a few scenes earlier, the angels talk and conclude “Let’s do something good”, only to follow with “We’ll go kill”, causing consternation among the people listening to them.

There are many jokes about prophets, angels, God (who in this film is a woman), Christ and religiosity. An alternative version of Old and New Testament events is also presented here, and characters suspended between angels of light and darkness appear—such as Muse, who is not mentioned in Scripture, or the thirteenth apostle, the black-robed Rufus, wandering in the hereafter. The new image of Christ, in the fair version (winking an eye and, of course, indicating OK with a hand gesture), is supposed to be a consolation for people, since “the crucifix is too depressing”, as I mentioned earlier. The new positive message, according to the principles of the “Catholicism, wow!” campaign, is to make religious symbolism more modern. Despite the fact that it is intended as entertainment and the director announced that it is not to be taken seriously, this undermines the content, which may resonate with a portion of the religious audience. Besides, if we are talking about the cultural context, Alexis de Tocqueville’s observation made more than 150 years ago about American contradictions still seems relevant and can help understand the context correctly: “…It is astonishing how free and harsh the morality of the same nation can be at the same time” (de Tocqueville 2006, vol. 2). The film highlights this bifurcation of American morality, and the voices of protest against the film should come as no surprise.

Moral ambiguity already appears at the level of aesthetics. Usually, angels, as personifications of purity, are presented in pastel colors30, and black is typically the color of evil in European iconography. There are also exceptions, such as the occasional depiction of St. Michael the Archangel as a knight. In turn, the knight’s armor may have a dark hue, such as in Hans Memling’s painting The Last Judgment, in which the Archangel is the central figure and his armor shines with a dark glow. The reversal of the symbolic color order (white/black) occurs in many productions; for example, the “angels” in the film City of Angels are dressed in black, and in the movie Dogma, it is one of the Satanists who dresses in white. A similar motif can be seen in the futuristic series Dark Angel (2000–2002), which tells the story of the deeds of a genetically enhanced human being who rebels against her “creators”. The girl is now working for the good of the people and walks around dressed in black, and the backdrop is often night. She works distributing packages, which echoes the biblical imagery of the angel messenger.

Can an Angel Fall?

This question is answered negatively by a representative of contemporary Chassidism in one of his internet videos31: An angel cannot fall because he is perfect and also he has no will. He cannot make decisions. He is a messenger, carrying out God’s instructions. How can we understand Satan? Satan is simply assigned such a role—to accuse man before the throne of God32. In the biblical literature, one can find similar explanations. “The most commonly offered concerns and/or objections to the angelic-fall thesis are” among others: “God calls the completed creation good and very good […]; All of creation, even the violent aspects, is claimed as God’s work […]; 3. Values come from disvalues […]; 4. Satan cannot be a co-creator with God” (Emberger 2022, pp. 230–232).

In some texts apocryphal to Catholic doctrine, like the Book of Enoch—parts of which are included in the Torah—there is information about angels that lived on Earth as watchers, who also fathered children with human females, giants called Nephilin. In popular culture, this motif is present in the TV series Ancient Aliens (2009–present) and in some clips found on social media. Angels here are interpreted as aliens from outer space, who are mistaken for heavenly creatures by humans. While intriguing, this does not add any new images or visions to the angelic imaginarium.

Returning to the topic of fallen angels, The Book of Revelation describes the struggle of angels and the fall of Lucifer, which culminates in Lucifer being placed in charge of hell. An attempt to respond to these depictions is the TV crime series Lucifer. Here, however, we have more fallen angels than just Lucifer and demons—even his brothers, such as the previously righteous angel Amenadiel, can also go astray, refusing to follow holiness and instead loving earthly life. The series, however, does not refer to scripture, but rather to colloquial perceptions, and attempts to shape heaven/hell in an earthly way, just like other pop culture depictions. However, we see traces of feminism—the Lord here has a wife, a rather reckless and cruel “mom”, whom “dad”, as Lucifer mentioned to his therapist, banished and imprisoned in hell for thousands of years. However, she got out of hell and ended up on Earth, where she performs actions more akin to hell rather than heaven. Her time on our planet ended soon—she flew out through a vagina-like opening to build her own universe. However, in the final series of Lucifer, the parents reconcile and Mr. God submits to his wife, following her to her universe.

The TV series Lucifer presents Christian faith and beliefs, along with their inversions. St. Michael, who is the most powerful of the biblical angels in the series, is portrayed as a person with great flaws, on top of which he also has a physical defect after a childhood fight with Lucifer. They are twins. Actually, in Catholic angelology, all angels were created at the same moment, that is—they are all twins…. In the first parts of the TV series Lucifer, the main character fulfilled the task of administering punishment upon people for their evil deeds. He constantly accuses various people—but before themselves and himself as the ultimate authority. As in a mirror, selected cultural trends are reflected here, such as the elimination of God from public life, which is symbolized in the series by the retirement of God. We don’t want the old God; we prefer the young one (Lucifer at the end). Evil is portrayed as tempting and not unambiguous. The devil tempts because he is beautiful and handsome in the human world. And, human nature is good, a belief often emphasized by many contemporary spiritual schools and New Age concepts, seeking to convince their followers. Interesting here is also the perception of luxury and wealth in the spirit of late capitalism, seen as the basis for a good and comfortable life.

Another trend in visualizing angels reflects evolving changes in perceptions of race, which can be seen as a form of affirmative action for people of color. In the TV series Lucifer, the devil is white—though not pale, with a slightly swarthy complexion and black-haired—while his brother, the angel who comes after him, is black. Anyway, he also eventually becomes “fallen”. Admittedly, he does not lose his wings. Similarly, “God”, who is about to retire, is also black-skinned. These angels carry a menacing aura and often appear demonic, creating further confusion between celestial and infernal images.

6. After the End of the World? Angels of the Apocalypse

Angels in popular culture are not rooted in any particular denomination33. Numerous images present angels known by name—Michael, Gabriel and Raphael; in addition to these archangels recognized by the Catholic Church, names known from the Kabbalah and Zohar appear—Uriel, Haniel, Raguel, Zadkiel, Cassiel, Selapheil and Metatron. Their faces are not always shown. However, sometimes instead of traditional pale angelic faces, brown and black ones are visible. The presentations of the angels—they stand or move either in the temple, in the open space above people heading to paradise or in the ruins of the old world34—are accompanied by music, such as Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, or other equally sublime music. Not every one of these clips tells stories directly related to the Bible. Sometimes they consists solely of a series of angelic portraits.

The question arises, what is the role of these visually attractive, beautiful images in shaping the social imagination? Can they encourage exploration of the history of angels and religious conversions? In the era of patchwork religiosity ushered in by the New Age, they can also be incorporated into a person’s belief system, introduced as tutelary spirits, not necessarily linked to the Bible or adherence to any of the great religions. There is not enough space here to address the reception of these videos in detail; however, the comments on these videos, typed in various languages, can be divided laboriously into several categories: (1) prayerful (“Gloria ha Dios35”; “Arch Angels36 of God, please protect us from the evil and guide us to follow the path to the kingdom of our Almighty God amen  ”)—often thankful (people thank God without specifying for what specifically; in others, they give thanks for faith, for Jesus Christ, for angels, etc.); (2) provocative—for example, attributing beauty to demons (a comment on the series of beautiful, named angels), or “oh so Angels also wear clothes?”, evoking the second commandment “tu ne te feras point de représentation quelconque des choses qui sont en haut des le ciel37”; (3) perfunctory—“amen”, “Michael”, “beautiful” and “God is wonderful”; (4) questioning—“Which is my guardian?”; “Mais qui vous a dit que cet créatures ont cette forme mes frère. Arrêtez de vous faireembrouillé ainsi38.”; and (5) claiming—“if you believe in God, Jesus Christ—text affirm (AMEN) to my inbox now to receive a big blessing to pay up ur rent and bills E.T.C.” (this comment is not from the person posting the material online). Although these clips generate extensive commentary, not all viewers leave a trace of their feelings or their thoughts in the comments. The impact in popular consciousness of such AI-created narratives requires long-term and multifaceted research. It is worth remembering that AI introduced to create web content is still in the learning stage; and is burdened with many biases—gender (Walsh 2017, pp. 161–162), racial39 and cultural (Jarecka and Fortuna 2022). Is AI also burdened by religious biases? This is an interesting topic, worthy of separate studies.

”)—often thankful (people thank God without specifying for what specifically; in others, they give thanks for faith, for Jesus Christ, for angels, etc.); (2) provocative—for example, attributing beauty to demons (a comment on the series of beautiful, named angels), or “oh so Angels also wear clothes?”, evoking the second commandment “tu ne te feras point de représentation quelconque des choses qui sont en haut des le ciel37”; (3) perfunctory—“amen”, “Michael”, “beautiful” and “God is wonderful”; (4) questioning—“Which is my guardian?”; “Mais qui vous a dit que cet créatures ont cette forme mes frère. Arrêtez de vous faireembrouillé ainsi38.”; and (5) claiming—“if you believe in God, Jesus Christ—text affirm (AMEN) to my inbox now to receive a big blessing to pay up ur rent and bills E.T.C.” (this comment is not from the person posting the material online). Although these clips generate extensive commentary, not all viewers leave a trace of their feelings or their thoughts in the comments. The impact in popular consciousness of such AI-created narratives requires long-term and multifaceted research. It is worth remembering that AI introduced to create web content is still in the learning stage; and is burdened with many biases—gender (Walsh 2017, pp. 161–162), racial39 and cultural (Jarecka and Fortuna 2022). Is AI also burdened by religious biases? This is an interesting topic, worthy of separate studies.

”)—often thankful (people thank God without specifying for what specifically; in others, they give thanks for faith, for Jesus Christ, for angels, etc.); (2) provocative—for example, attributing beauty to demons (a comment on the series of beautiful, named angels), or “oh so Angels also wear clothes?”, evoking the second commandment “tu ne te feras point de représentation quelconque des choses qui sont en haut des le ciel37”; (3) perfunctory—“amen”, “Michael”, “beautiful” and “God is wonderful”; (4) questioning—“Which is my guardian?”; “Mais qui vous a dit que cet créatures ont cette forme mes frère. Arrêtez de vous faireembrouillé ainsi38.”; and (5) claiming—“if you believe in God, Jesus Christ—text affirm (AMEN) to my inbox now to receive a big blessing to pay up ur rent and bills E.T.C.” (this comment is not from the person posting the material online). Although these clips generate extensive commentary, not all viewers leave a trace of their feelings or their thoughts in the comments. The impact in popular consciousness of such AI-created narratives requires long-term and multifaceted research. It is worth remembering that AI introduced to create web content is still in the learning stage; and is burdened with many biases—gender (Walsh 2017, pp. 161–162), racial39 and cultural (Jarecka and Fortuna 2022). Is AI also burdened by religious biases? This is an interesting topic, worthy of separate studies.

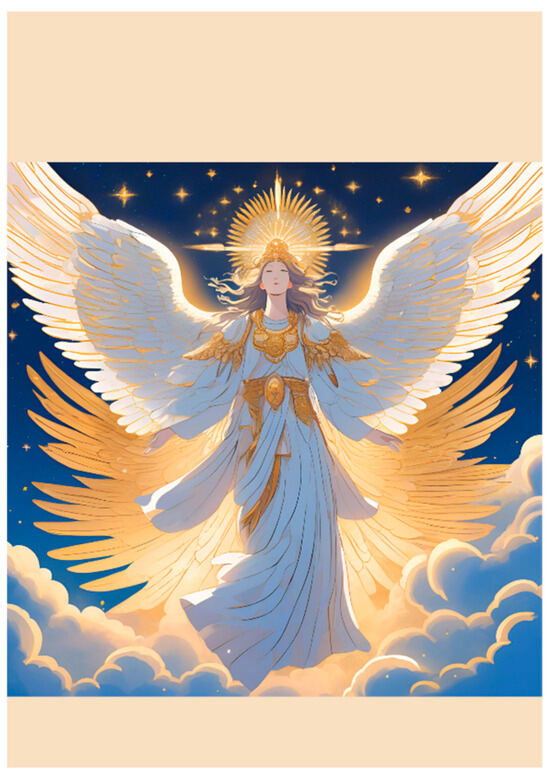

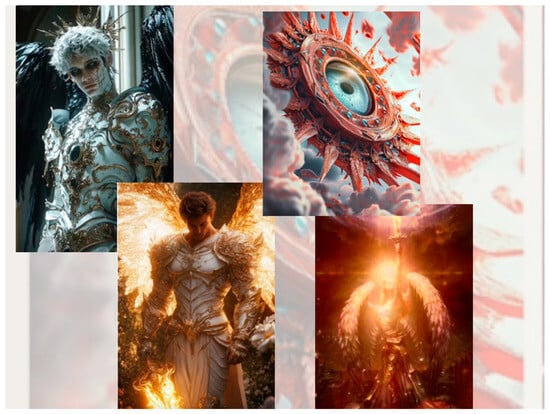

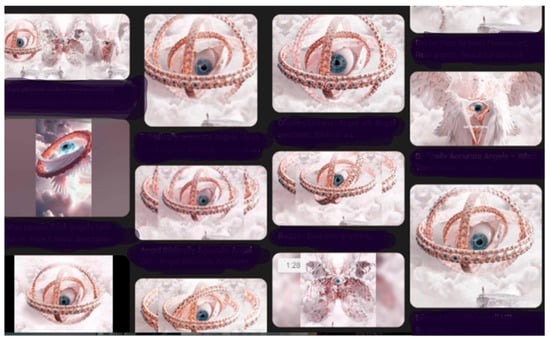

”)—often thankful (people thank God without specifying for what specifically; in others, they give thanks for faith, for Jesus Christ, for angels, etc.); (2) provocative—for example, attributing beauty to demons (a comment on the series of beautiful, named angels), or “oh so Angels also wear clothes?”, evoking the second commandment “tu ne te feras point de représentation quelconque des choses qui sont en haut des le ciel37”; (3) perfunctory—“amen”, “Michael”, “beautiful” and “God is wonderful”; (4) questioning—“Which is my guardian?”; “Mais qui vous a dit que cet créatures ont cette forme mes frère. Arrêtez de vous faireembrouillé ainsi38.”; and (5) claiming—“if you believe in God, Jesus Christ—text affirm (AMEN) to my inbox now to receive a big blessing to pay up ur rent and bills E.T.C.” (this comment is not from the person posting the material online). Although these clips generate extensive commentary, not all viewers leave a trace of their feelings or their thoughts in the comments. The impact in popular consciousness of such AI-created narratives requires long-term and multifaceted research. It is worth remembering that AI introduced to create web content is still in the learning stage; and is burdened with many biases—gender (Walsh 2017, pp. 161–162), racial39 and cultural (Jarecka and Fortuna 2022). Is AI also burdened by religious biases? This is an interesting topic, worthy of separate studies.What does the Bible really say about angels? This question is addressed in numerous clips presented on YouTube, TikTok and sometimes Instagram. Instead of sweet childlike figures or feminine, smooth and mysterious, warm angel-ladies based on imagery from the 19th century (Figure 7), as noted by C.S. Lewis, the imaginarium offers male figures in armor as God’s warriors (Figure 8 and Figure 9), or frightening figures—hybrids blending elements from the human world, the animal kingdom and the fantasy realm of horror movies. And, what is more important, some of these new types of angels are depicted as only eyes, or mechanical constructions based on circles, built from eyes and feathers/wings. They are present on the internet thanks to AI. This represents a new medium of creation, where “everything” is possible due to the development of new technologies driven by algorithms and applications based on textual descriptions. Colors play a significant role in this angelic imaginarium—some images (videos) are mostly white, and some accents of color are connected with structures like eyes or human silhouettes, elements of horses, etc. Gold—as a symbol of heavenly origin—is typical for the images of Archangel Michael, Gabriel or angels who still belong to God’s Kingdom. Dark colors like black are often associated with apocalyptic imagery, regardless of whether the angels are good or fallen (Figure 10).

Figure 7.

Seraph as visualized by AI, in the Manga style, and as a female (the author used Canva to generate this image).

Figure 8.

The contemporary angelic imaginarium on TikTok constists of AI generated images (a collage created from pictures appeared on the search for “angels”).

Figure 9.

The contemporary angelic imaginarium on TikTok (a collage from the AI-created clips).

Figure 10.

Print screen of illustrations of the forms of dark, apocalyptic angels generated by AI, the result of the internet search.40

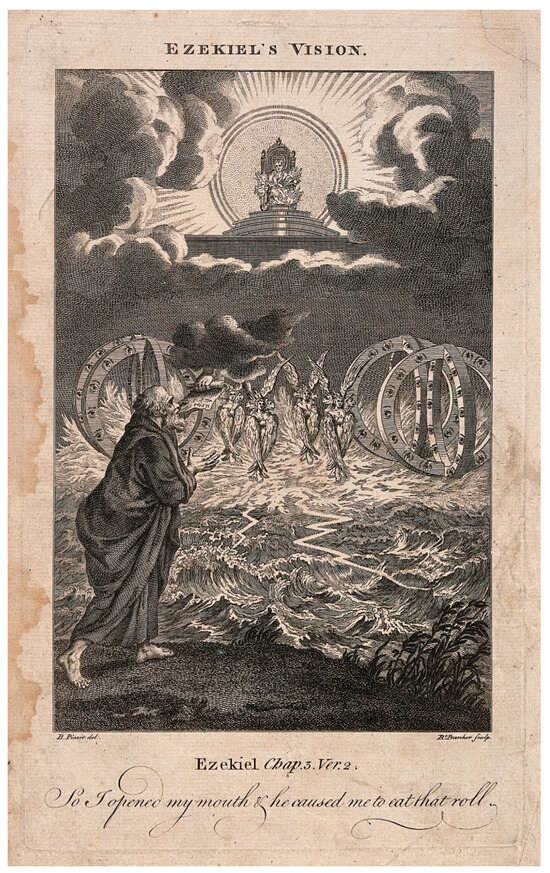

In social media—for example, on Instagram and TikTok—especially in 2023–2024, one can observe a “harvest” of non-anthropomorphic angels. The authors of these clips refer to the Holy Scriptures, noting that angels are described quite differently than we imagine, as the eye itself, as a series of eyes, as a great radiance, etc. Some authors of these clips try to convince viewers that these frightening figures are the “real ones,” just like the one presented in Ezekiel’s vision (see Figure 11). Again, as C.S. Lewis mentioned, biblical, historical angels were scary. The image below presents a cherubim from Ezekiel’s vision, an angel close to God’s throne, as popularly depicted on social media.

Figure 11.

“Accurate” angels as depicted in the Bible. Print screen from net searching with AI-created pictures based on Ezekiel’s vision.41

This kind of visualization is rooted in historical drawings, such as the above from the 18th century by R. Pranker after B. Picart. Visualizing Ezekiel’s vision is a challenge for every artist (Figure 12). Here is an excerpt of its mention in the Bible: “Now as I looked at the living creatures, behold, a wheel was on the earth beside each living creature with its four faces. The appearance of the wheels and their workings was like the color of beryl, and all four had the same likeness. The appearance of their workings was, as it were, a wheel in the middle of a wheel. When they moved, they went toward any one of four directions; they did not turn aside when they went. As for their rims, they were so high they were awesome; and their rims were full of eyes, all around the four of them. When the living creatures went, the wheels went beside them; and when the living creatures were lifted up from the earth, the wheels were lifted up. Wherever the spirit wanted to go, they went, because there the spirit went; and the wheels were lifted together with them, for the spirit of the [d]living creatures was in the wheels. When those went, these went; when those stood, these stood; and when those were lifted up from the earth, the wheels were lifted up together with them, for the spirit of the [e]living creatures was in the wheels” (Ezekiel 1: 15–21).

Similar information about angels not being “in the likeness of man” is confirmed by followers of Judaism. On the internet, one can easily find AI-generated images that further serve to confirm the problematic nature of angels as depicted in the Christian tradition, which popular culture continues to distort. These are not “nice” and “sweet” angels—these are angels of wrath, prowess, vengeance and apocalyptic might.

Algorithm-generated images and videos are used as moralizing clips—serving as mementos of our lives, and mementos of a world hostile to man and its new rules. In these videos, passages from the Bible, often from Revelation, are featured and presented in a visually interesting short form—either edifying or frightening. There are also longer videos on TikTok explaining the nature of the present (end of times), or encouraging prayer or the listening of Scripture—even with eyes closed, the images are not visually or emotionally moving; rather, they are static, allowing you to engage in prayer in spiritual concentration.

7. Conclusions: Cultural Trends as Presented by Secular Angels

Movie angels appear primarily in morality narratives, typically set in realistic contexts, demonstrating the difficulty filmmakers have in depicting the dissimilarity between the two worlds: both humans and angels share similar challenges, stages of development and flaws. Nominally, pop culture “angels” are self-proclaimed beings, engaging in all possible sins. Disobedience is the order of the day here, marked by rebellion against God, doing things their own way, quarreling and sometimes aggressive behavior. These shortcomings of movie angels are treated with a pinch of salt because God will forgive anyway, understand anyway, or get a little angry and get over it; after all, he is merciful.

These angels have little to nothing in common with the biblical depictions of angels known in Western culture. An angel, a messenger, was a spirit (cf. CCC 1993, pp. 328–329) who sometimes appears as a human being to people when conveying a specific message from the Creator (CCC 1993, p. 332). Movie angels, on the other hand, introduce moral ambiguity, such as the following:

- -

- In human form, they exhibit worse traits than many humans (“rogue” Teen Angel l and the vengeful angel of death in Dogma) and plunge into sensuality like Nathaniel in the film City of Angels or the debauched and hedonistic titular Michael;

- -

- They are all too eager to help people straighten out their life paths, not only realizing the essence of the problems that overwhelm people (series such as Highway to Heaven, Touch of an Angel) but sometimes forcing them to change their decisions (Highway to Heaven);

- -

- They desire to become human, which is a glorification of human everyday life (Der Himmel über Berlin/City of Angels) and a degradation of perfect heavenly existence, expressing disagreement with God’s plans.

Angels once symbolized a realm on Earth inaccessible to man and testified to the magnificence of God. The pop culture movie angel no longer leads to the Creator. Instead, they lead first to themselves and then to man, who has the right to violate divine laws. They usually focus on man rather than God, disregarding the latter. These are not angels that point to eternity. Angels in pop culture sometimes have no connection at all with religiosity or piety, and they are not messengers; instead, they carry out their own will rather than God’s. Movie angels teach how to be good people, help work through problems and occasionally inspire hope that one can always rely on God’s assistance. They also highlight self-indulgence as a hallmark of the era, seemingly justifying almost every human choice and decision, ultimately reassuring us that God will forgive.

Thus, in the case of film narratives, we can safely speak of the Americanization of the image of the angel. What does Americanization mean in popular culture? It refers to the adaptation of the product to market requirements with all possible modifications. Alexis de Tocqueville, writing about the American character, emphasized the passion for wealth, recognizing that it constitutes a virtue in American society. He also highlights traits such as industriousness and the constant pursuit of novelty, of the unattainable—to achieve more and more, never being satisfied with what one has and has already achieved.

“Believe in yourself” is a very catchy slogan—in yourself, not in God. The power of positive thinking and prowess in life also point to Americanization (cf. Grzeszczyk 2003, 37 ff.). As Alexis de Tocqueville stated, “The Americans, who make a virtue of commercial temerity, have no right in any case to brand with disgrace those who practise it”.43 Such characteristics are also mirrored in the portrayal of pop culture angels—cocky and audacious, absolutely un-angelic. Angels, too, engage in all sorts of “business,” and they do it with aplomb. Besides, all the film angels encourage their charges to be brave, to become bold in facing life and its challenges. They point out new possibilities to individuals who are bitter because of illness, old age, multiple failures, disability, unrealized ambitions, etc. This reflects a typically American approach to life:

“To earn the esteem of their countrymen, the Americans are therefore constrained to adapt themselves to orderly habits—and it may be said in this sense that they make it a matter of honor to live chastely.

On one point American honor accords with the notions of honor acknowledged in Europe; it places courage as the highest virtue, and treats it as the greatest of the moral necessities of man; but the notion of courage itself assumes a different aspect. […] Courage of this kind is peculiarly necessary to the maintenance and prosperity of the American communities, and it is held by them in peculiar honor and estimation; to betray a want of it is to incur certain disgrace”44. American courage is about daring to endure the inconveniences of fate, downfalls, and problems, as well as the courage to start again, in case of failure.

In addition, these angels are unmistakable representatives of the culture of individualism, with their own opinions, demonstrating independence from God, disobedience45 and assertiveness. They have their own plan for life. In conclusion, a note on political correctness: Using post-modern terminology, angels are treated as “public relations” representatives of God and the Heavenly Court. Political correctness is marked in the narratives under discussion in various ways: by taking human form, angels are representatives of different races (e.g., the TV series Touched by an Angel and Lucifer; the film City of Angels); portrayals of God as a woman are a nod to feminism and gender correctness (the film Dogma and TV series Lucifer), while inclusivity towards homosexuality is shown in the representation of heavenly beings in the TV series Angels in America.

In the interpretation of the phenomena of AI-generated angels presented in social media, one can utilize sociological concepts and approaches rooted in visual anthropology to analyze new types of images. Apocalypse, or the end of times, is a popular motif in popular culture texts from the beginning of the century. As the year 2012 approached, numerous books, movies, and infotainment documentaries were produced on the topic (like 2012, dir. Roland Emmerich, 2009; 4:44 Last Day on Earth, dir. Abel Ferrara, 2011; TV series: 10.5: Apocalypse, 2006; Doomsday: 10 Ways the World Will End, 2016; etc.). The fear of doom present in today’s culture reflects an aspect of the human condition in the postmodern era. It is only one of the trends that sheds light on the evolving changes of the angelic imaginarium in the 21st century.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | It is worthwhile to analyze all these topics, if only to highlight the paradoxical tendencies and opposing phenomena permeating contemporary culture: real waste versus exhortations to austerity; surplus production versus the “zero waste” ideology; virtual wealth (e.g., bitcoin and NFT collecting) versus real poverty (huge individual and national debts); and creating a desire for new gadgets versus popularizing the ideology of minimalism. However, this essay is not the appropriate medium to elaborate on these topics. Moreover, in the context of this essay, one might add observable tendencies, such as the secularization of political and social life on the one hand (Taylor 2007), and on the other, the longing for spirituality (Ammerman 2013; Chowdhury 2018), for that which grows beyond the material expression of life on Earth. Religiosity and spirituality are not defined by statistics, but rather by human needs. |

| 2 | The concept of convergence culture by Henry Jenkins is followed here, where convergense means: “the flow of content across multiple media platforms, the cooperation between multiple media industries, and the migratory behavior of media audiences who will go almost anywhere in search of the kinds of entertainment experiences they want” (Jenkins 2008, p. 2). It is not only the technological process: “Convergence does not occur through media appliances, however sophisticated they may become. Convergence occurs within the brains of individual consumers and through their social interactions with others. Each of us constructs our own personal mythology from bits and fragments of information extracted from the media flow and transformed into resources through which we make sense of our everyday lives” (ibidem: 3–4). |

| 3 | The article deals with Western culture and omits examples from the Orthodox Church. The history of the icon has not entered popular culture as intensively as examples from Western painting. On the origins and meanings of the sacred image in Orthodox Tradition, see Ouspensky (1990). |

| 4 | The differences between religions also concern the understanding of the fall of angels, the tasks of Satan (Emberger 2022; Ryba 2018; Schatz 2008; Zarasi et al. 2015). |

| 5 | “You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the parents to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me, but showing love to a thousand generations of those who love me and keep my commandments”, Ex 20: 4–6 (https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Exodus%2020&version=NIV, accessed on 4 February 2025). |

| 6 | https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/areopagite_13_heavenly_hierarchy.htm, accessed on 4 February 2025. |

| 7 | A captivating example of wingless angels is Ecce Ancilla Domini! painted in 1850 by Dante Gabriel Rosetti. The painting which was not created for an ecclesiastical commission and can now be seen at the Tate Gallery in London. |

| 8 | “Angels depicted heralding the birth of Jesus in nativity scenes across the world are anatomically flawed, according to a scientist who claims they would never be able to fly” (https://www.telegraph.co.uk/topics/christmas/6860351/Angels-cant-fly-scientist-says.html, accessed on 11 February 2025). |

| 9 | In AI-generated clips created by artists and common Internet users presented on TikTik or Instagram, angels are powerful figures, often in armor, with huge wings, sometimes even exceeding the size of the angels themselves. The costumes here are more standardized than in historical art: one common style features —gold or white; while another one consists of white robes or armor with gold ornaments, or white with luminous elements in a chosen color, green, purple or blue. |

| 10 | Jesus Christ, who appeared to St. Francis in a vision in the form of a six-winged seraph and marked him with stigmata, is portrayed in this way. This visualization stems from the testimony of St. Francis. And, it was upheld by artists such as Giotto, Domenico Ghirlandaio and El Greco. |

| 11 | Research on this topic started more than 10 years ago and resulted in conference presentations and published article (Jarecka 2014). This essay builds upon the previous text with the use of new materials, collected after its publication. |

| 12 | It is worth mentioning some of the difficulties in web research. To estimate the interest in the web, one can use popular tools such as Google trends. In this section, one can find statistics divided between the “whole world”, continents, countries or even regions. To narrow down the results, one can use specific categories—“education”, “finances”, “garden”, “society”, “entertainment”, and “books and literature”; however, “religion” is not included. It is difficult to use this tool, as the algorithm is not adjusted to much of the important parts of human existence. Spirituality is not included either. The same problem occurs when using other search engines. Even if the Google search engine indicates 3,450,000,000 hits for the keyword “angel” in half a minute, the selection of the religious, spiritual or artistic context must be done not mechanically, but manually, using the researcher’s experience. |

| 13 | Many documentaries are available on this platform, including those on the history of angels https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xzxLDqXtlt4 (accessed on 5 January 2025 or the psychology of angels https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ErXWtdC2ZYI&t=1332s (accessed on 5 January 2025. |

| 14 | For example, in studies such as Angels by Paola Giovetti (2001), Angels. Images of Celestial Beings in Art by Ward and Steeds (2005) and Mythical Creatures and Demons. The Fantastic World of Mixed Beings by Heinz Mode (1975). Religious works, on the other hand, deal with Christian images, such as Angels in Salvation History by Rev. Marian Polak (2001). |

| 15 | This is typical of the New Age. The attractiveness of the New Age, as Rev. Witold Jedynak notes “…lies in its ability to gather elements from all religions and ages, and then transform them into a message of new strength and relevance for modern man” (Jedynak 1995, p. 4). |

| 16 | https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5f/Durer%2C_la_grande_passione_06.jpg (accessed on 29 January 2025). |

| 17 | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:D%C3%BCrer_-_Large_Passion_12.jpg#/media/File:D%C3%BCrer_-_Large_Passion_12.jpg (accessed on 29 January 2025). |

| 18 | The Screwtape Letters: Annotated Edition: https://www.google.pl/books/edition/The_Screwtape_Letters_Annotated_Edition/aSj_-mgwWbYC?hl=pl&gbpv=1, accessed on 10 December 2024. |

| 19 | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carlo_crivelli,_montefiore,_piet%C3%A0_di_londra.jpg (accessed on 5 January 2025). |

| 20 | Often, ostensibly “religious” films deal with political issues or talk about conspiracy theories linked to the Vatican, such as the documentary Angels and Demons Revealed by David McKenzie (2005), explores stories about the Illuminati, the KGB, blackmail, preparations for world war, assassination attempts on popes, etc. Similar stories are also included in the documentary Angels vs. Demons: Fact or Fiction? directed by Will Ehbrecht in 2009. The latter was made on the wave of popularity of Dan Brown’s (2001) novel Angels and Demons and the feature film inspired by it. |

| 21 | https://genius.com/Jim-morrison-a-feast-of-friends-lyrics (accesssed on 27 November 2024). |

| 22 | This idea is probably rooted in the works of Emanuel Swedenborg, who wrote that after death, the human mind “no longer thinks naturally, but spiritually […] it becomes wise like an angel, all of which confirms that the internal part of man, called his spirit, is in its essence an angel […]; and when loosed from the earthly body is equally in the human form and an angel” (1966, p. 314). |

| 23 | All pictures based on the movies or social media clips are created by the author with the usage of AI (apps available in Canva and Photoshop). |

| 24 | The Screwtape Letters: Annotated Edition: https://www.google.pl/books/edition/The_Screwtape_Letters_Annotated_Edition/aSj_-mgwWbYC?hl=pl&gbpv=1 (accessed on 10 December 2024). |

| 25 | Industriousness, perseverance, frugality, courage to take on challenges, etc., are typical qualities that enable a person to strive for success. Success itself is understood as primarily business success, cf. (Grzeszczyk 2003, pp. 38–43). In contrast, underachievement can lead to disbelief in oneself and bitterness. Paul Pearsall wrote of the toxic success syndrome, that it is “a chronic sense of inadequacy, doubt, disappointment and lack of connection” (Pearsall 2004, p. 59). These are the kinds of undeveloped states of mind that the series’ angels (in both Highway to Heaven [1984–1989] and Touched by an Angel [1994–2003]) help overcome. |

| 26 | The series’ creators also wrote: “Monica, Tess and Andrew are angels who are sent down to earth to help people who are in difficult situations. Monica is still an inexperienced angel, and Tess is her guide and teacher… [distributor’s description]”, from http://www.filmweb.pl/serial/Dotyk+anio%C5%82a-1994-93637 (accessed 10 December 2024). |

| 27 | “Satan or the devil and the other demons are fallen angels who have freely refused to serve God and his plan. Their choice against God is definitive. They try to associate man in their revolt against God” (cf. CCC 1993, p. 414). |

| 28 | Discussing American individualism, Ewa Grzeszczyk writes: “…Indeed, people who highly value individualism tend to isolate themselves from the rest of society, locking themselves in a tight circle of family and friends” (Grzeszczyk 2003, p. 37). |

| 29 | Film angels are given names. In some movies, one can identify an angel due to his biblical name (such as Michael); however, in film narratives, they are given ordinary names—Giordano, Lawrence, Monica and Tess. One can look for meanings related to history, e.g., Giordano Bruno or Monica, the mother of St. Augustine, but this is not the purpose of calling an angel by a name that can sound very anonymous, peculiar or strange—Giordano. He is one of us, perhaps a visitor from heaven, and seems like a normal, ordinary one. By contrast, in the movie Dogma, the angel of death, Loki, is named after a pagan god of destruction from Scandinavian mythology, which signals the ideological hybridity of such a character. |

| 30 | The heterogeneous colors of angelic representations are also typical of Western painting; there are no established or typical color patterns. Although, the “husband in a white robe” is an angel appearing after the resurrection, some of the angels from the history of painting wear more than just white robes. We can also find quite a few examples illustrating the symbolism associated with specific archangels. For example, in the scene painted by Lucas de Heere of Mary and Jesus with two angels (16th century), St. Archangel Michael kneels before the Mother of God in dark, graphite armor covered with a golden–red mantle, while symmetrically on the other side, Archangel Gabriel kneels in a white flowing robe with an imposed golden–green mantle. Gold is a companion color to angelic images throughout the history of painting and may form the background of the depiction, a halo or certain elements of the costume. For example, the painting Angels from the 14th century by Italian master Ridolfo Guariento depicts a host of armed angels, as warriors in soldier’s attire: golden belts, golden spears, golden epaulettes and halos, golden halves of their coats and other elements of their image, which set the tone for the whole painting, emphasizing the majesty of the holy spirits.Their armor is decorated with golden embroidery. Their wings are golden–red–black, and red complements the colors of their garments. |

| 31 | In the series “Tajemniczy śwat żydów” (The secret world of the Jews), episode Anioły w Judaizmie (“Angels in Judaism”), A Polish Chassidic Jew explains the nature of angels in the Torah: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QbhS86UqNIU (accessed on 10 December 2024). |

| 32 | These ideas are propagated not only in the movie, but such an explanation is also typical to the Judaica narrative: “…Rivkah Kluger claims that ‘the Hebrew Bible knows no Satan’, no rebel angel who challenges the authority of God and tempts man […]. Nevertheless the passages, which refer to a celestial Satan, point to a progressive development of this figure in the Hebrew Bible. Rivkah Kluger suggests that, over time, one can detect a process of ‘cleansing Yahweh of his dark side’. That is, from Job to Zechariah to the book of Chronicles, there is a notable shift from the source of provocation being a functionary on behalf, perhaps even as an aspect of God, to a projection of malevolence onto the other, Satan (as accuser in the Higher court)” (Rachel 2009, pp. 64–65). |

| 33 | The book by Peter G. Riddell and Beverly Smith Riddell (Riddell and Riddell 2007) is dedicated to various visions of angels in different Christian denominations and in Islam. Those who are interested in classical religious literature will find extensive information in the works of Aquinas St. Thomas (2025), which aligns with the Catholic tradition, and Emanuel Swedenborg (1966), whose works resonate in Protestant thought. |

| 34 | There are many possible contexts for presenting angels and angelic-like creatures; in some clips, “angels” appeared as models at a fashion show (one of TikToker’s @mongo.ai videos). |

| 35 | “Glory be to God”. |

| 36 | In all quotes from network comments—original spelling. |

| 37 | “thou shalt not make unto thyself any representation of the things which are in heaven above”. |

| 38 | “but who told you that these creatures have this shape my brother. stop being so foggy!”. |

| 39 | https://time.com/5520558/artificial-intelligence-racial-gender-bias/; https://www.ajl.org/ (accessed on 4 February 2025). |

| 40 | The internet search was done in June 2024 in the broser Microsoft Bing, the keyword - “angels”. |

| 41 | The internet search was done in June 2024, the broser Microsoft Bing, the keywords - “angels” and “Ezekiel’s vision”. |

| 42 | https://wellcomecollection.org/works/yebnb6mv (accessed on 3 November 2024). |

| 43 | Alexis de Tocqueville, Chapter XVIII: Of Honor In The United States And In Democratic Communities, (https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/de-tocqueville/democracy-america/ch37.htm, accessed on 3 November 2024). |

| 44 | Ibidem. |

| 45 | It has already been mentioned that the rebellious angels are demonic creatures, which is no longer commented on in the narratives. |

References

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2013. Spiritual But Not Religious? Beyond Binary Choices in the Study of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 258–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, Randall N. 1989. Inside the New Age Nightmare. Lafayette: Huntington House. [Google Scholar]

- Bannister, Robert C., ed. 1972. American Values in Transition. A Reader. New York: Harcourt. [Google Scholar]