Abstract

Beginning in the 13th century, rivalry among Italian city-states intensified, transforming cultural competition into a strategic tool for asserting identity. Roman heritage was often contested, with cities emphasising their claims as the true heirs of Rome. Siena has faced criticism for its lack of major historical sites. In response, its municipal authorities and citizens developed the legends of the “she-wolf” and Saint Ansanus. These legends reinforced Siena’s urban identity through historical narratives and public art. During the Renaissance, Siena redefined its history to assert its legitimacy by drawing on classical culture. This re-articulation of identity addressed historical rivalries and revealed the enduring complexity of local identity formation in Italy. This study examines historical legends and uses historical materials, such as city archives and artworks, to research the Italian city of Siena during the Renaissance and to investigate the origins of urban legends, their controversies, and how Siena created the legends of the “she-wolf” and Saint Ansanus.

1. Introduction

“Historical legend” is a unique folklore genre, as many legends are often associated with particular historical figures or places (Zhong 2010, pp. 185–88). In the 19th century, the Whiggish school in England employed the legend of Martin Luther from the 16th century to classify the “progress” and “hindrance” of historical events and to judge the moral qualities of historical figures (Bartfield 2012, pp. 45–49). In the 20th century, the Soviet scholar Malinowski further explored the social function of historical legends (Malinowski 1948, pp. 125–26). He summarised the findings of Soviet anthropologists and Western sociologists and psychologists, articulating that the social function of “historical legends” is to legitimise specific systems and maintain the status quo of these systems (Burke 2019, p. 182). This social function has been demonstrated by scholars studying collective memory, resulting in the popularisation of linguistic constructivism and material media theory1. Since the onset of the 21st century, historians and anthropologists have examined historical legends through urban history, microhistory, and new cultural history to identify the collective commonalities within the narratives across different eras and the episodes that have been deliberately omitted or forgotten. From a cultural memory perspective, urban memories constituted by legends represent the people’s collective memories and social memories that can be passed on continuously. In addition, they are a source of historical identity for politicians and provide insights for people to investigate the distinctions between different eras (Assmann 2002, p. 171).

From the late Middle Ages to the Renaissance, almost every city in Italy documented its origins through legends. They used them to establish an identity that separated them from other cities (Beneš 2011). Identity is often based on memories formed by legends, with the memories of different people combining to create the identity of a family, city, or even country to the extent that it has been said that “the city depends on memory to exist” (Mumford 2004, p. 105). One such city is the central Italian city of Siena, located on the main transportation route of the Apennine Peninsula. It has served as an important banking and economic hub since the Middle Ages due to its proximity to the Via Francigena. This pilgrimage route connected France, Spain, and other European countries, heading south to Rome.

However, compared to its economic strength, Siena has a relative disadvantage in the cultural field because its opponents constantly question its historical heritage, and some literary and historical writings portray it as a city founded by barbarians (Perez 2023, pp. 175–76)2. To restore the city’s reputation, during the Renaissance, the rulers of Siena systematically constructed legends about the city’s origins, thus strengthening its political and cultural identity among its citizens. The memory of the city, formed by the legends, contributed to establishing an independent social and political identity. Utilising this identity, Siena maintained relative stability in the turbulent political environment of Renaissance Italy.

Although the scholarly community has addressed the issue of identity in Renaissance Siena, relevant studies predominantly emphasise two specific perspectives. First, the evolution of Siena’s communal political structures has been examined from the perspective of traditional political history. Researchers seek to identify the defining features of its political identity by examining the regime transitions among the wealthy nobles (Gentiluomini), the government of twenty-four (Ventiquattro), the government of nine (Nove), and the government of twelve (Dodici), which culminated in the Republic prior to Medici domination (Casciani and Hayton 2021; Ascheri and Franco 2020, pp. 65–84; Bowsky 1981; Caferro 1998). Second, from an art historical perspective, scholars have examined metaphors within the fresco series in Siena’s Palazzo, elucidating how these metaphors express republican ideals and reinforce the city’s political identity (Nevola 2008, pp. 157–73; Cantucci 1961, pp. 251–62; Christiansen et al. 1988; Funari 2002; Guerrini 2000, pp. 510–68). Although the above research perspectives reference the historical legends of Siena, they are mostly brief and do not generalise the recurring legendary images present in artistic or cultural endeavours. Moreover, pertinent studies predominantly originate from architectural landscapes, anchoring urban memory in a tangible form and highlighting its visibility and permanence. Although this elucidates the importance of architectural landscapes in memory preservation, it overlooks the dynamics of historical legends in memory, their emotional influence, and their potential impact on identity formation.

Legends are often modified or rewritten as times and societies change, and their adaptability allows narratives to conform to shifting societal standards. Historical figures and moral fables in legends are more likely to evoke emotional responses in audiences because of their narrative and symbolic nature. This connection allows historical legends to compensate for architectural landscape limitations regarding shaping urban memory and preserving memory continuity and adaptability. This study examines historical legends and uses historical materials, such as city archives and artworks, to research the Italian city of Siena during the Renaissance. This study investigates the origins of urban legends, their controversies, and how Siena created the legends of the “she-wolf” and the Saint Ansanus, also known as Saint Ansano. It also evaluates the effectiveness of these legends and memories in shaping Siena’s identity. Simultaneously, it explores the interaction between the complexity of Italian local history and culture and the shaping of identity through the construction of legends.

2. The Origin and Controversy of Siena’s Historical Legends

The 13th-century European commercial revolution (de Roover 1942, pp. 34–39) established Siena as a major urban republic in the Apennines. During Siena’s nine-member (1287–1355) governance, the city’s population and trade surged, driving continuous expansion. The rulers recognised identity as necessary and legitimate for maintaining urban governance and outward expansion. They began to construct political identities through intangible legends and tangible architecture (Starn and Partridge 1992, pp. 16–17; Zhu 2011, p. 120).

2.1. Historical Absence and Siena’s Identity

Siena’s identity is its weak point. Florence, Milan, and Rome possess numerous Roman monuments, but Siena lacks historical monuments directly associated with Rome. Flavio Biondo, a 14th-century Italian archaeologist, defined Siena as a “modern” city due to the absence of ancient sources referencing Siena (Biondo 2005, p. 87). The absence of historical records prompted medieval historians to perceive Siena as a descendant of the Gauls, who invaded the Apennines and plundered Rome rather than having Roman origins (Perez 2023, pp. 175–76). As rivalry and hostility between Italian cities intensified during the Renaissance, Siena’s extraterritorial and barbaric origins were once again utilised as a justification for attack by others. The claim that Siena was a barbaric city, or even descended from the inherently inferior French, gained prevalence throughout the Italian Peninsula, especially after the widespread reading of Dante’s Divine Comedy and Boccaccio’s paraphrasing of it (Alighieri 1991, p. 699; Boccaccio 1846, pp. 241–42). This statement reinforces negative stereotypes about Siena and makes questioning Siena’s identity even more problematic.

In response to external questions about their own identity, Siena’s rulers attempted to bridge the historical divide by shaping historical lore, giving Siena an identity linked to Roman Orthodoxy. In this process, the ‘she-wolf and the twins’ and the legend of Saint Ansanus3 became key to the construction of identity. The former emphasised Siena’s connection with Romanitas, freeing it from the impression of ‘Gallic origin’ and presenting its own history as a continuation of that of Rome. The latter consolidated Siena’s identity through the legend of Saint Ansanus. The latter, through the legend of Saint Ansanus, consolidated Siena’s legitimacy and religious authority in Christendom and achieved an internal identity of faith.

Although the shaping of these two legends points to the construction of Siena’s legitimacy, they have triggered fierce disputes in academic discussions about their origins. Who actually dominated the shaping of these legends? Was it the church, the secular government, or a joint effort? Did the formation of legends stem from local historical memory, or was it a re-creation based on political needs? These disputes not only affected Siena’s own historical identity but also reflected how Italian city-states in the Renaissance period shaped their own identities through historical writing and gained an advantage in cultural competition. This is why the legend of Siena’s origins has captivated Western scholars, who have sought to discover more about its identity. Were its origins from Giovanni Villani’s “eliminated” Gauls—“eliminated” because of their physical and mental disabilities (non-bene sani) (Villani 1991, pp. 80–82; Beneš 2011, pp. 98–111)—or is Siena of Roman descent, as claimed by Senius and Aschius since the 14th century?

2.2. Controversy About the Origin of the ‘She-Wolf and the Twins’ Legend

Compared to the ‘Gallic’, the legend of the ‘She-wolf and the twins’ in Siena traces the city’s history back to ancient Rome and its descent from Remus, one of the Roman twins. Yet recent archaeological research has revealed a historical reality that is very different from these legends: archaeological data indicate that Siena’s identity originated from Etruscan influences rather than Gallic or Roman, tracing back to the Middle East (Turkey, Jordan, and Syria). They left many frescoes and pottery in Siena, which led to the assumption that the Etruscan civilisation peaked in the 6th century (Achilli et al. 2007, pp. 766–67; Stoddart 2009, p. 37). The name ‘Siena’ seems to derive from the prominent family, Saina, who resided in the area, with the name being Latinised to Saena during the Roman conquest. Recent archaeological research, particularly the studies of Achilli et al. (2007) and Stoddart (2009), has demonstrated that the Renaissance ‘Gallic’ and ‘Roman’ origins of Siena are not substantiated historical facts. Nonetheless, these two urban legends were constructed to undermine rivals and defend political legitimacy. This underscores the significance of Roman origins in the historiography of the city-state during Renaissance Italy, establishing that this ‘Roman descent’ was the foundation of the city’s culture.

Archaeological discoveries have directly challenged the authenticity of the legend of the she-wolf of Siena, thereby sparking controversy within the academic community. The central question is whether Siena’s identity is rooted in real history or if it is a political construct. According to the “ecclesiastical-led theory”, Pope Pius II (1405–1464), Archbishop of Siena and then Pope, encouraged the earliest systematic documentation of Sienese historical lore during his pontificate (Nevola 2000, p. 119). Cronache Senesi, the earliest record of the legend of the she-wolf and twins, is thought to have been written by humanist Francesco Patrizi under the pseudonym Tisbo at the request of the Pope. Pope Pius II attributed a lengthy, illustrious, and remarkable urban beginning to his birthplace, Siena, a long, noble, and striking urban origin through the legend of the twins Senius and Aschius, countering earlier claims by Flavio Piando and Giovanni Villani that Siena was a “new” city in Tuscany (Lisini and Iacometti 1931–1939, pp. xxvi–xxix). Tisbo’s Chronicle enriches the legend of the she-wolf and twins in Siena’s founding history more than the previous nine-member government’s emphasis on public art promotion. The twins were inspired by Apollo, the sun god, to ride a white horse and a black horse (the colours of Siena’s coat of arms and flag) while fleeing from their uncle. They ended up, along with a Roman statue of the she-wolf, with a tribe of shepherds at the foot of a mountain in Etruria. This tribe lived on the banks of the river Tresa and worshipped the moon goddess Diana. They were welcomed and honoured by the tribe and soon became the leader and governor (Lisini and Iacometti 1931–1939, pp. xxvi–xxix).

Another group of scholars proposes that the origin of the legend be traced to the earlier nine-member government of the late medieval period, emphasising that its leadership was predominantly secular rather than ecclesiastical. Carrie Beneš, for example, emphasises that the legend comprises a series of narratives detailing the city’s succession to Rome authored by several rulers across different periods. The widespread depiction of the she-wolf in Sienese sculptures4, frescoes, and seals during the rule of the nine-member government established it as a recognisable and potent symbol of the city (Beneš 2011, p. 9). For instance, in 1297, the government commissioned a statue of a she-wolf feeding twins at the city’s entrance, symbolising Siena’s ancestral connection to Rome. It provided the physical basis for Pius II’s subsequent ’refinement’ of the Sienese legend. Benes also referenced other Italian cities: Padua as a remnant of the Trojan kingdom after the Trojan Horse, Genoa as the embodiment of the Roman God Janus, and the Roman cities as imaginative constructs imbued with legends of the she-wolf nursing her twins, which emphasised Roman heritage and were commonly used by rulers to shape the memory of Italian cities. Benes’s study of legend perceives it as a medium of memory, a practice used in Connerton’s writing to transform memory for historical reconstruction (Connerton 2000, pp. 10–11).

Although the legend of the she-wolf and the twins endowed Siena with Romanitas, a purely secular historical narrative was insufficient to anchor the city’s identity. Historical legitimacy derives not only from the construction of secular power but also from religious affiliation. Within the Italian city-state system, a city required both a traceable historical origin and a recognized sacred status within the Christian world to attain broader social acceptance (Webb 1996, pp. 4–6). Thus, Roman origins alone were inadequate; Siena also required a narrative that reinforced its religious legitimacy. Against this backdrop, the rulers of Siena gradually cultivated the sacred image of Saint Ansanus, establishing him as the city’s official patron saint and employing this legend to reinforce Siena’s religious identity. This process of ‘dual reconstruction’ illustrates how medieval and Renaissance Italian city-states forged their identities through historical narratives, ultimately constructing a cohesive urban identity—one that combined historical legitimacy with alignment to the Christian world’s framework of identity.

2.3. ‘Secularising’ the Legend of Saint Ansanus

The legend of Ansanus originated from the prolonged medieval contest between the bishops of Siena and Arezzo regarding control over neighbouring dioceses (Webb 1996, p. 38), but was gradually used by secular governments for identity construction. As generally recognised in academic discourse, this conflict spanned 5 centuries. It revolved around territorial and fiscal claims over several small rural sanctuaries (Cappella di Dofana) dedicated to Ansanus’s relics. These sanctuaries, spread across approximately 700 square kilometres, became focal points of the enduring rivalry (Bezzini 2015, pp. 19–29; Webb 1996, p. 37).

After Siena received the Ansanus relics in 1108, the Church of Siena commemorated the event by writing Translatio Sancti Ansani (hereafter referred to as Translatio). It became a foundational text in shaping the religious memory of the Sienese Church. Subsequently, the Church of Siena issued the Ordo Officiorum, which further regulated the recitation of Translatio in church on the morning of the anniversary of the arrival of relics in Siena (Trombelli 1766, pp. 273, 304). These texts not only underscored Siena’s triumph in the diocesan dispute but also reinforced the city’s internal cohesion by constructing a sacred narrative of Siena’s ‘defeat of Arezzo.’ For instance, one of them (Lectio I) describes the origin of the relics and ends with the statement that “some people from the neighbouring regions got together and tried to steal the relics of Ansanus in secret”, alluding to the fact that their neighbour, Arezzo, had been “stealing” them for years. Lectio II emphasises the piety of the Sienese and their joy at the recovery of the relics; it mentions that, when the relics were returned to Siena, a loud noise was heard over the city as if by divine providence, and citizens were called upon to honour their patron, Ansanus, as a child would honour his father. Lectio III describes how the citizens of Siena crushed the neighbours during their ‘attempted theft’—‘when they pursued them, the men scattered and ran about like flies without heads!’ (Baluze and Mansi 1764, p. 65). Research has shown that the legend of Saint Ansanus was not shaped exclusively within a religious framework. The narrative of Siena overcoming its rival Arezzo to ‘seize’ Ansanus not only elevated a fundamental ecclesiastical memory into a marker of communal identity but also became a crucial emblem for Siena in sustaining its urban identity and affirming the unity and autonomy of its civic community.

In addition to the attack on Arezzo, Translatio emphasises the strong links between the saint and Siena. The text explicitly describes Ansanus’s “2-month” stay in Siena to “perform many miracles” and his “torture in Siena” by the emperor’s lieutenant, Litia (Baluze and Mansi 1764, p. 62). In a narrative dominated by the Sienese diocese, Ansanus’s preaching brought good to Siena, and the relics he left behind after his death became pillars of faith and symbols of protection for the Sienese. The most iconic of these are the prayers describing Ansanus’s miraculous ability to heal others, often typical of medieval episcopal saints (Baluze and Mansi 1764, p. 64). It was predicted that all Sienese baptised by Ansanus would be cured as a sign of the saint’s patronage over Siena. Some scholars believe that including this healing power was a response to earlier claims that the Sienese had descended from sickly Gauls (Anderson 2019, pp. 249–50). This aligns with the creation of the legend of the she-wolf and twins, which aims to establish the historical origins of Siena and reinforce its identity through mythologised narrative devices.

During the Renaissance, several scholars, including Magdalino, and Casciani and Hayton, argued that the Sienese city government gradually asserted dominance over the legend of Saint Ansanus. The figure of Saint Ansanus was progressively integrated into the secular government of Siena, becoming an integral element of communal politics. One explanation is Siena’s transition from a pro-papal (Guelph) stance to a pro-imperial (Ghibelline) stance, commencing in 1198 and culminating in 1250 (Magdalino 2002, p. 84, Cited in Hiestand, Rudolf. 1986. Manuel I. Komnenos und Siena. Byzantinische Zeitschrift 79: 29–34). This transformation marked the gradual liberation of Siena from episcopal control, beginning in the mid-12th century and leading to the establishment of the independent Republic of Siena (Casciani and Hayton 2021, p. 4). However, it is essential to note that while emancipating itself from episcopal control, the city government did not fully secularize. Instead, it actively reconfigured religious symbols to reinforce the legitimacy of secular rule. The nine-member government also dominated the placement of Ansanus images in churches. Between 1287 and 1288, the government commissioned the painter Duccio di Buoninsegna to paint the stained-glass window of the main cathedral in Siena, featuring Ansanus, the first patron saint of Siena, placed to the left of Madonna. In 1308, the government commissioned Duccio to paint the altarpiece of Siena’s main cathedral, titled the Madonna in Majesty, which depicts Ansanus in the foreground of the painting, dressed in the iconic black-and-white robes that represent Siena.

Therefore, the Republican government propagated the legend of Ansanus, extending it to communal spaces other than churches. In 1315, the nine-member government commissioned Simone Martini, a representative of the Sienese School of Painting, to paint a large fresco, 10 m long and 8 m wide, titled Maestà. The painting was placed in the Palazzo Pubblico in the Council Chamber. On the right-hand side of the fresco, Ansanus kneels to listen to the Virgin Mary, holding a scroll with petitions to the Mother of God for the protection of Siena (Frugoni 2019, p. 41). Ansanus, in the Palazzo Pubblico, at this point, acted as a bridge between the divine and the secular, demonstrating to all who visited the hall his sentiments for the city: ‘I died in Siena, but I am the new Siena’ (Necem Mihi Sena Ego Senae Vitam) (Gori 1576, p. 2). A public holiday honouring Ansanus was first commemorated in 1326, when the government of Siena issued a communiqué inviting all citizens to light a candle annually on 1 December. Thus, Ansanus is the only one of Siena’s four patron saints commemorated annually by municipal authorities and citizens (Webb 1996, p. 277). Over time, the masses and prayer services began to include musical compositions inspired by Ansanus legends, reflecting the legend’s integration into Siena’s cultural and religious practices (D’Accone 2007, p. 104). This close connection to civic and communal spaces ensured Ansanus’s continued significance in present-day Siena, even as he later faced competition from newer saints like Saint Catherine.

This series of public artworks and festivals from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance demonstrates that Siena’s municipal government did not sever ties with religious traditions but instead reinforced its legitimacy through the reinterpretation of religious symbols. The worship of Ansanus diminished due to the Black Death in the 14th century, subsequent social unrest in Siena over the next 50 years, and the conquest of the Republic by the Medici family of Florence in 1555. The situation did not change until the 1930s when the Archbishop of Siena, Mario Toccabelli, revitalised Ansanus (Parsons 2006, p. 51). Although the cult of Saint Ansanus fluctuated over time, its central role remained unchanged: he served as both a symbol of religious devotion and a unifying element of communal identity. Rather than ‘secularising’ the image of Ansanus, the Sienese government integrated his cult into civic governance, incorporating religious symbols into secular rule.5

In writing Siena’s history, the church and the secular government collaborated to create the she-wolf and twin legend. In contrast, the Ansanus legend was transformed from a religious to a secular narrative, shifting focus from the church to the city’s founder. This is not merely a strategy of identity construction in Siena but also a representative example of how Renaissance Italian city-states crafted their image through multilayered historical narratives. These legends gave the community a sense of Roman origin and identity, legitimising the church and the nascent local government and conferring an advantage in competition with neighbouring cities. Research on the ongoing composition of legends illustrates the increasing importance of secular governance during the Renaissance as a factor in shaping identity. Cities reinforced their identity by memorialising legends in tangible structures that combined fiction with historical elements and artistic propaganda within public spaces.

3. Characterisation and Construction of the Sienese Legend in Urban Historiography

The Florentine historian Giovanni Villani, in his twelve-volume Nuova cronica, explains why the city histories of Renaissance Italy were so full of legends: “As a daughter of Rome, we (Florence) are rising, and many great things happened before her. In contrast to Rome, which is in decline, it was appropriate for me at this time to write a new chronicle of the events and origins (fatti e cominciamenti) of the history of Florence (Villani 1991, p. 563).” Villani, who was in Rome then and had read Roman legends written by ancient scholars such as Virgil and Livy, hoped to emulate his ancestors by preserving historical memory and providing lessons to the people of Florence. During that period, Italian cities such as Florence, Milan, and Siena actively sought to strengthen their popular identity through Roman lore (Jones 1997, pp. 55, 445–46), illustrating the city’s ‘Romanitas’ and linking elements of Roman legend to the city, a vital aspect of humanist urban historical writing.

Simultaneously, conformity to tradition implied that a secondary characteristic of the literature during that period was its inseparability from Christian culture. Although the pagan elements of Roman history gave legitimacy to rulers, they did not meet the needs of the faith of the time. Consequently, while chronicling the city’s history, humanists integrated Roman heritage and historical legends concerning ancient Christian martyrs into the city’s memory. This tension between secularism and religion is a common theme in European historical writing, but it was particularly accentuated in Italian cities during the Renaissance (Yin 2023, pp. 13–15). The integration of ‘Romanity’ and Christian martyrdom into Siena’s collective memory, as reflected in the historical writing of legends, can be analysed in relation to the city’s identity formation, which involves a combination of fictional and biographical narratives and public art promotion.

3.1. Combining Fiction and Historical Biography

In response to Florence’s questioning and attack on the city’s identity in the 13th century (Villani 1991, p. 64; Bowsky 1981, pp. 159–74), Siena established a festival in honour of Ansanus to follow in the ‘footsteps’ of the saint. In the 14th century, Republican rulers further developed the legend of Siena’s Roman origins around the “twins and the she-wolf”, integrating this iconic element into the city’s narrative and highlighting Siena’s Roman heritage. Siena reinforces its Roman origins through classical legends and Christian imagery and reflects the influence of Renaissance Italy’s antiquity and the northern city-state’s intense political and cultural rivalry.

The Sienese legend of the twins and she-wolf (Lupa Senese) is almost identical to the Roman story of the city’s founding. Only the protagonists are changed from the Roman brothers, Romulus and Remus, to two sons, Senius and Aschius, who are forced to leave Rome to escape their uncle Romulus and find Siena under the patronage of the she-wolf. Siena’s version of the she-wolf legend allows the city to trace its identity directly to Rome, proving that Siena descends from a long line of ancient Roman gods and disproving earlier claims of Gallic ancestry. Why did Siena create a legend that would become a lasting memory for its citizens and, thus, fulfil the city’s identity? In what way has the legend of the she-wolf survived to become a symbol of the city of Siena?

Central to the creation of the historical legend was the establishment of Siena’s link to the elements of the legend. Senius and Aschius are mythological figures, but the lack of ancient monuments makes it difficult for Siena to associate Roman twins directly with the city. For this reason, Siena has sought to obtain relics from the Roman period outside of the city to reinforce its connection to antiquity by relocating them there. In contrast to the twin founding of the city, referenced solely by an anonymous author in the 15th century (Rondoni 1886, pp. 8, 25), wolves are documented in Sienese legal literature as early as the 13th century: the Commune of Siena had tamed wolves in the town hall as a diplomatic gift. It enacted legislation to reward the capture of live wolves (especially females) (Zdekauer 1897, p. 80). As a result, foreign states often chose wolves as gifts for Siena. For example, a diplomatic document recorded by Montelupo in 1322 reads: “Honourable and powerful lords (of Siena), we (Montelupo) present to you a wolf which, although it was born large and powerful, is more docile and tamer than a puppy. This is because we took it from its mother before it was weaned and carefully fed by our children, so it is an honour to offer it as a token of our respect and goodwill towards Siena” (Miscellanea storica senese 1893, pp. 28–29). As a symbol of political diplomacy, the wolf in the town hall became the link between Siena and Rome during the Renaissance, providing the basis for the legend. In addition, the depiction of the Sienese wolf gained widespread acceptance throughout the remarkable journeys across Europe in the 17th century. In The Voyage of Italy, Richard Lassels characterises Siena, while under Florentine control, as “the wolf has been muzzled” (Lassels 1670, p. 235).

The commemoration of Saint Ansanus has a dual nature: on the one hand, it reinforces Siena’s historical ties to the Roman Empire; on the other hand, Ansanus, as the first believer to preach in Siena, is both a symbol of the city’s conversion to Christianity and a symbol of the early Christian tradition. Ansanus and Siena’s Roman origins are inextricably linked in all traditional accounts of the city’s early history (Malavolti 1968, p. 13). As stated above, from the 7th century onwards, Siena and Arezzo engaged in military conflicts concerning the ownership of Ansanus’s remains, culminating in Siena’s triumph 5 centuries later. According to the records of the Siena municipal assembly in 1326, the city instituted a festival in December dedicated to the commemoration of Ansanus. Detailed regulations stipulated that all citizens must cease work and participate in the celebrations (Bowsky 1981, p. 263). City officials at all levels had to attend on time and pay their respects by holding candles.

In a manner analogous to the incorporation of the legend of the she-wolf into the city’s chronicles, the Sienese composed a substantial body of hymns, prayers, and communion settings for the festival, with Ansanus serving as the unifying theme (D’Accone 2007, pp. 98–99, 118–38). The thematic mass that took place in Siena served to laud the martyrdom of this noble Roman aristocrat. The city again established a connection between its Roman nature and early Christian culture, consolidating its identity. In addition to utilising textual materials to emphasise its dual legitimacy as both Roman and Christian, Siena also initiated the employment of local artists to create art in public spaces. The emergence of the renowned Siena School of Painting during the Renaissance was further bolstered by a substantial influx of patronage from the city government.

3.2. Art in Public Spheres

Current academic opinion posits that the earliest written record of the Siena twins and the wolf is of the 13th century, yet this does not imply that the rulers of Siena relied solely on texts to shape their ‘Roman’ identity. As early as 1297, when the government of nine ruled Siena, a sculpture of a she-wolf nursing two baby boys was erected in the Palazzo Pubblico. In 1372, two additional reliefs of she-wolves were placed at the centre of the round arch at the main entrance. Concurrently, the government commissioned a sculptor to craft a new silver seal, a task that necessitated the incorporation of the she-wolf motif (Biccherna 1344). In 1327, when Siena expanded its city walls and rebuilt one of its gates, the Porta Romana/Porta Nuova, two large stone sculptures of a she-wolf nursing twins were added to each side of the gate6. The city gate was an important landmark along the Via Francigena pilgrimage route to Rome. The wolf statue was erected to convey Siena’s Roman heritage to citizens, travelling merchants, and travellers.

This initiative was accompanied by government penalties for any creations that compromised the image of the she-wolf. In 1264, the Capitano del Popolo (Captain of the People) of Siena confiscated the painting and fined the painter, Ventura di Gualtieri, Lira 35 for painting a shield with a lion (the symbol of Florence) defeating the she-wolf (Milanesi 1873, p. 43). It is a coincidence that in the early 15th century, Florence also designed a sculpture of a lion capturing a wolf for placement in front of the city hall. This was interpreted as a symbolic reference to Siena, which was engaged in discord with Florence during this period (Johnson 2015, p. 156). As was stated previously, Siena’s inability to produce a convincing case for its Roman identity is due mainly to the paucity of relics directly connected to ancient Rome. Consequently, Siena has persistently procured antique artefacts from the Roman era and Roman-produced stone materials, situating them in prominent locations. This practice of creating an artificial ‘local’ Roman identity, in conjunction with the iconic image of the she-wolf, has been a central feature in Siena’s construction of a Roman identity in public spaces. An example of this phenomenon can be observed in the ancient Roman columns that grace the exterior of the city hall (Bargagli-Petrucci 1906, pp. 22–23).

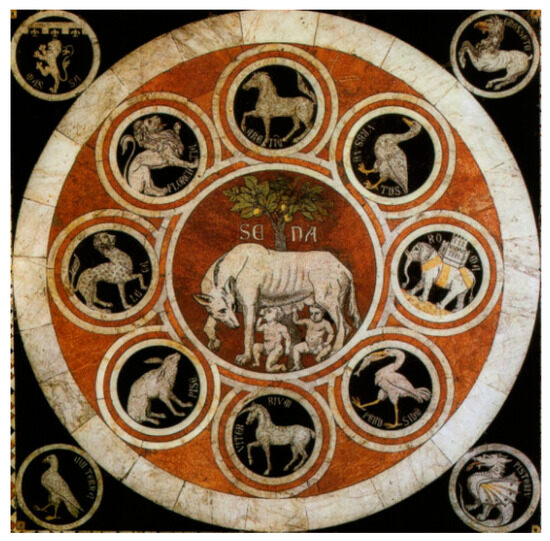

Moreover, the Lupa Senese (she-wolf) symbol is included in the Duomo di Siena (Cathedral of Siena), which is closely associated with the lives of its citizens. The circular symbol in the entrance aisle of the main church was crafted using the marble intarsia technique. It depicts allies (in the form of animals) surrounding the Lupa Senese (she-wolf) (Figure 1). During the Renaissance period, a significant number of wolf-themed icons and sculptures were commissioned and created for the rulers of Siena. These artistic creations were placed in prominent public spaces, including city squares, landmarks, and halls. The incorporation of the she-wolf reinforced the wolf’s status as a symbol of Siena’s identity within ecclesiastical contexts and positioned it alongside images of saints. This aided the faithful in their prayers through ancient Christian practices and icons.

Figure 1.

Lupa Senese (the ‘she-wolf’) in the Duomo of Siena.

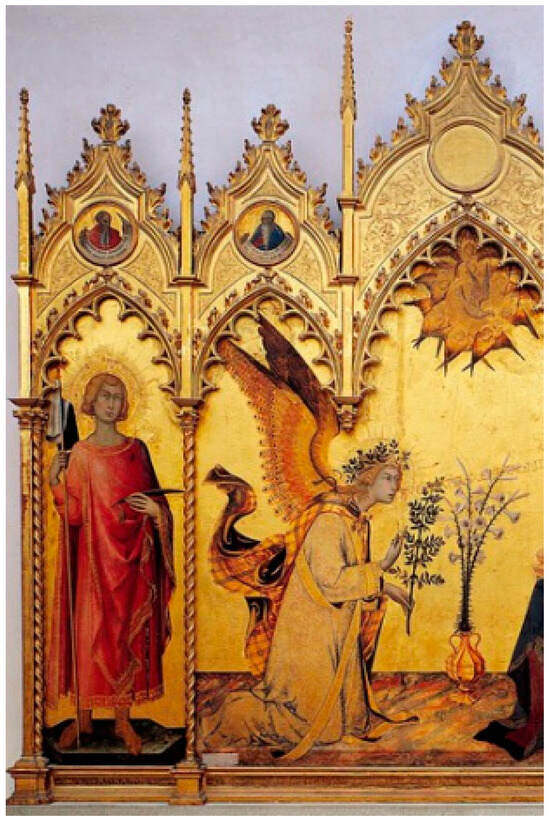

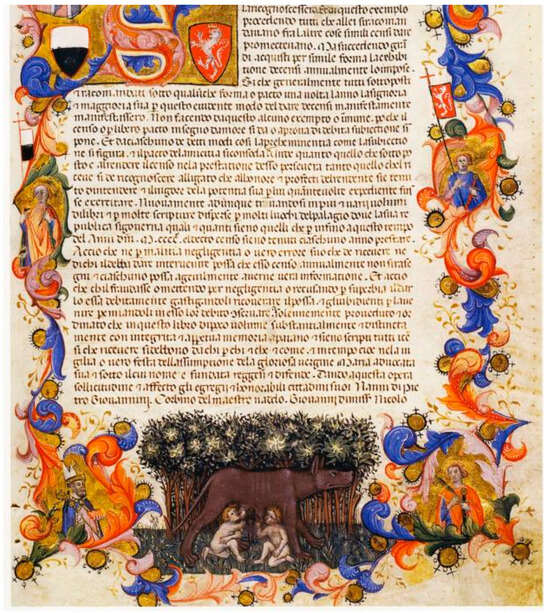

The most direct image of a saint is that of Saint Ansanus, and altarpieces featuring him have been representative works of Siena since the 13th century. In Annunciation (1333), a work painted by Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi for the Siena Cathedral, Ansanus is depicted wearing a red Roman toga and holding a black-and-white banner representing Siena in his right hand. He is positioned behind the angel who announces the birth of Jesus (Figure 2). The government also commissioned Martini to paint another altarpiece, Saint Ansanus. The bust, located in the Siena City Hall, also maintains the image of the martyr holding the black-and-white Siena city flag (Figure 3). The three characteristics of ancient Rome, Siena, and Christianity are ingeniously combined in Ansanus through art and repeatedly reproduced in Siena’s materials. For example, the front page of the Register (Libro dei Censi) (Figure 4), which recorded the population, land tax, and people’s offerings to the church in Siena in the 15th century, has the pattern of a she-wolf feeding her twins. In the upper left corner, Ansanus has completely retained his previous image of holding the city flag in a Roman toga (Steinhoff 2000, p. 167).

Figure 2.

Annunciation (1331–1333, detail), now in the Museo degli Uffizi.

Figure 3.

Saint Ansanus (1326). The artefact is housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Figure 4.

Libro dei Censi (1400).

The legends that have been created shape the city’s memory and the nation’s origins and establish the legends of Siena as the most diverse, well-preserved, and artistically significant cultural heritage of the Renaissance in Tuscany (Rondoni 1886, p. 8). The creation of legends has become significant material for subsequent scholars to analyse the political operations of the Italian commune. Moreover, the employment of legends to disparage rival cities’ identities was already a prevalent propaganda technique during this era. A notable example of this can be seen in the 15th-century conflict between the Florentine Republic and Milan under the Visconti, which was characterised by a dispute over the respective historical origins of the two cities7. The concept of Rome’s identity, perceived as an objective historical truth and a crucial element in developing medieval urban identities, warrants further scholarly investigation.

4. Immediate Impact: The Influence of Historical Writing and the Reconstruction of Siena’s Identity

This section will examine the effectiveness of the legends of the she-wolf and Ansanus in shaping Siena. The rulers aimed to construct a “new” urban history of Siena through legends for two primary reasons: first (external), to determine whether they had garnered the approval of foreign populations by enhancing the city’s image and diplomatic standing, and second (internal), to ascertain whether they had reconfigured collective memory to ensure that the people of Siena would perpetuate and accept the narrative of its Roman origins across generations.

Siena sought to establish its identity by refuting the ‘Gaulish theory’ proposed by Villani; this theory challenged Siena’s historical legitimacy. Therefore, the city promoted the legend of the she-wolf and Ansanus. These narratives provided a more profound historical foundation and a stronger connection to ancient Rome. The viewpoints of international tourists regarding the Grand Tour in Italy post-16th century might be utilised to evaluate the efficacy of Siena’s historical narrative, as evidenced by their accounts.

4.1. Travelogues and Scholarly Works

Montaigne provides a comprehensive account in his diary of the delegation from the recently Medici-governed city of Siena, which conveyed their congratulations to the Duke in Florence during the summer of 1581. He describes how “A young man dressed in black and white velvet came out, carrying a large silver dish and the Sienese she-wolf statue”. He presented them to the Grand Duke and delivered a short dedication speech. The young men exhibited an unrestrained demeanour, their behaviour indicating they were not participating in a solemn ceremony but rather in a game (De Montaigne 2017, pp. 179–80). These individuals represented the castles and territories that constituted the Siena region. In a letter to a friend written during a journey, the 18th-century English writer Horace Walpole stated: “Our guide exhibited the sculpture of the she-wolf of Siena and informed us that it had nursed the city’s founder”. However, Walpole subsequently expressed scepticism regarding the guide’s classical knowledge and deemed the origin explanation to be “extraordinarily superstitious” (Toynbee 1903, pp. 53–54). Another British naturalist, Sir Richard Colt Hoare, described the Siena coat of arms in his travelogue, A Classical Tour through Italy and Sicily, popular in 19th-century Britain. At that time, the Siena coat of arms still featured the twin and she-wolf motifs, emphasising that these motifs were repeatedly carved on pedestals in different parts of the city. Hall begins his discourse by stating that Siena was a Roman colony, Sena Julia. He recommends the Ansidei Altarpiece in the cathedral and the black-and-white mosaic floor, lauding the latter as an outstanding work combining Sienese characteristics with Renaissance artistic techniques (Hoare 1819, pp. 4–5).

In addition to travelogues, research on the history of Siena has gradually increased since the 20th century. A significant proportion of these studies have been produced by foreign scholars residing in Italy. Their exploration of Siena’s legends has brought to light the effectiveness and influence of shaping the city’s identity. In 1901, Langton Douglas’s A Story of Siena provided a comprehensive account of the historical legend concerning the city’s founding by a she-wolf and her twins. The author considered it of little significance to explore the legend’s truth but rather believed that it confirmed that, at a particular time, Siena’s strength was already a reduced version of Rome’s (Douglas 1902, pp. 5–7). Douglas challenges the traditional narrative of Ansanus by scrutinizing its historical foundations. He argues that, although it has long been a tradition for the Sienese to commemorate Ansanus, others perceive the historical portrayal of the saint as ‘vague and illusory’. He further comments that the Sienese’s familiarity with the saint’s image stems from exposure to stories about the city’s patron saint from a young age, through frequent depictions in churches and other venues (Douglas 1902, p. 17).

Another scholar of Renaissance history in modern America, Ferdinand Schevill, introduced Ansanus as the patron saint of Siena in Siena: The History of a Medieval Commune, lauding Siena’s veneration for Ansanus. Schevill’s work demonstrated how Ansanus’s veneration functioned as a unifying force among the city’s elite and its populace, thereby facilitating the resolution of inter-ethnic divisions within the Lombards and the Romans. This, in turn, is said to have contributed to forming the ‘new’ Italian identity (Schevill 1909, pp. 27–28). William Heywood’s Guide to the History and Art of Siena has been republished multiple times. In this text, the author presents the legend of Ansanus in an affirmative (though not entirely factual) manner. The author elects to expound Siena’s urban legends with artistic masterpieces. A notable example of this approach is the sculpture of Ansanus that adorns the town hall facade, dating back to the 14th century, accompanied by two Roman she-wolf motifs (Heywood 1924, pp. 18, 228).

Notably, Villani’s ’Gaulish’ remarks about Siena are not mentioned in the foreigners’ travelogues. Among the monographs on the history of Siena, only Langton’s History of Siena references Villani’s remarks. Langton believed that Villani’s comments were motivated by his hatred of Siena as a native of Florence (Douglas 1902, p. 5). It is evident that, when foreign travellers and scholarly works first introduced Siena, the legend of the she-wolf and her twins, along with Ansanus, dominated the historical record. This external validation serves as a testament to the legend’s widespread acceptance.

4.2. Memory and City Spirit

However, the inner question remains whether the legend of the she-wolf and her twins achieved internal acceptance among the populace of Siena and whether it passed from one generation to the next, thereby contributing to the reshaping of collective memory. The following analysis seeks to observe this phenomenon through a contemporary lens by examining the city’s modern celebrations and imagery.

The citizens’ memory of Ansanus, Siena’s patron saint, provides the starting point. In addition to the 14th-century paintings of Ansanus that have already been referenced, the recent commemoration of the saint also reflects the process of the citizens’ acceptance of his memory (Parsons 2006, pp. 51–54). For example, in the mid-15th century, the government of Siena built a monastery named after Ansanus out of reverence for him on the former prison site where he was imprisoned before his execution after Siena was ruled by Florence in 1555. The annual early December festival gradually diminished in prominence, overtaken by the more religiously charged festival of Saint Catherine (Gigli 1854, p. 576). By the late 17th century, Ansanus’s statue had become a focal point of attention. Girolamo Gigli recorded that the city of Siena commissioned a statue of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus, crafted from pure silver, to express gratitude for the 1697 earthquake. Notably, this earthquake caused no significant damage to the city. Next to the Virgin is a statue of Ansanus holding a model of the city of Siena in his hands. He seeks the Virgin’s protection in a gesture of devotion, while the Virgin responds by covering the model of the city with her cloak (Gigli 1732, p. 216).

In November 1968, the district administrative body (Magistrato delle Contrade), with the unanimous approval of all districts (Contrade), formally reinstated the Feast of Sant’Ansano on December 1st. This festival, known as the “District New Year” (Capodanno Contradaiolo), marks the beginning of each Contrada’s annual cycle. Its revival was not merely an act of historical homage but a conscious effort to reaffirm Siena’s civic-religious identity in a period marked by increasing interest in cultural heritage preservation across Italy. The re-establishment of the Feast of Sant’Ansano reflects a deliberate endeavour to reclaim and reshape collective memory.

Once overshadowed by the rising prominence of Saint Catherine’s veneration, Sant’Ansano’s legacy was reintegrated into Siena’s public consciousness through carefully orchestrated ceremonies that underscored his historical significance as the city’s patron saint. A pivotal moment in the festival is the solemn commemorative Mass held at the Siena Cathedral, attended by six senior officials and six representatives from each Contrada, all clad in traditional historical attire. The celebrations culminate in a grand procession weaving through the city’s historic streets, ultimately passing by the Monastery of St. Ansano, originally built in the mid-15th century on the very site where the saint was once imprisoned (Parsons 2004, p. 99). More than a mere ritual, this festival serves as a modern reaffirmation of Siena’s deep-rooted historical consciousness and the enduring identity of its Contrade. By reviving Sant’Ansano’s veneration, the city not only honours its patron but also strengthens the historical bonds that connect past and present, ensuring that these traditions continue to shape its collective identity.

On the other hand, the she-wolf statue (Lupa), as a material embodiment of Siena’s urban legend, is widespread and diverse. It is mainly present in every district of Siena and essential places such as the town hall and the entrance to the city (Table 1), further demonstrating the identity of the legend among the city’s inhabitants.

Table 1.

Locations in Siena where representations of the she-wolf appear.

There are still 12 statues of the she-wolf in the city of Siena. The two gates that connect the north and south of the city and coincide with Pilgrim’s Way are each adorned with a she-wolf statue and serve as urban landmarks of Siena facing in the direction of Florence and Rome (Casciani and Hayton 2021, p. 360). In addition, the distribution of the she-wolf columns in each urban area located in critical public squares shows that the she-wolf is an urban symbol of Siena and a sign of community identity. The distribution of the she-wolf in places of everyday life, from the core religious (the Cathedral of the Lord of Siena) and political (the Town Hall) sites to the neighbourhoods and entrances to the city, makes the image of the she-wolf deeply embedded and part of the identity of the inhabitants of Siena.

The image of the she-wolf and her twins is a physical representation and a symbol of the spirit of the city of Siena. The ‘Grosso della lupa’ (silver she-wolf), minted in 1510, is not only characterised by legendary imagery but is also clearly modelled on the image of the she-wolf on Roman coins that were once unearthed in the prehistoric period (Grossman 2006, p. 111, quote from “Le monete della repubblica di Siena (1180–1559).” In Le monete della repubblica senese. Milan, 1992, pp. 329–31.). By the middle of the 16th century, the symbol of the Sienese she-wolf and her twins had become almost omnipresent, embedded in the collective consciousness of the Sienese. A typical example is a story about an older Sienese man in Alessandro Sozzini’s diary of the Florentine attacks on and occupation of the Republic of Siena, 1550–1555.

The Duke of Medici’s mercenaries captured a Sienese woman of about 75 years of age, and the soldiers demanded that she shout ‘Duke! Duke!’ (‘Duca! Duca!’) as a sign of submission. She continued to chant ‘she-wolf’, Siena’s symbol, even after being mistreated. Eventually, the soldiers gagged her with a cloth to stop her from shouting. The onlookers could still observe from her facial movements and eyes that she was still trying to shout ‘she-wolf’ and never gave in until she was tortured to death. Alessandro laments: “She held on to this crazy idea until she died. She may have gone to the she-wolf’s heaven because she was so devoted to it [Siena]” (Sozzini 1842, p. 543). By the middle of the 16th century, the legendary link between Siena and Rome was widely accepted and recognised as part of the identity of the Sienese people in their daily lives.8 The she-wolf became a symbol of Sienese solidarity, resistance, and struggle. Even today, in modern educational and tourist activities in Siena, the she-wolf is still an important tool and effective vehicle for transmitting Sienese legends and heritage from one generation to the next. It is an essential part of the city’s visual culture.

From the Middle Ages to the end of the Renaissance, Siena constructed an urban legend based on Ancient Rome and Christian elements, combining them with the city’s identity to shape its external image and self-identity. The dedication of the martyr Ansanus praises Siena’s ancient Christian tradition, while the legend of the wolf and the twins seeks to justify the city’s origins and territorial legitimacy. The paucity of historical monuments is the reason for the reinvention of Siena’s history as a city and the political and cultural need to use its history to define its identity and forge a consensus.

5. Summary and Implications

In response to the questioning of its history by other Italian cities during the Renaissance, Siena deliberately constructed a history of the city around the legend of the Roman she-wolf and the martyrdom of Ansanus, thus securing the city’s identity on a political level. Siena employed two methods to construct the city’s historical narrative. One was the combination of fictional mythological elements with existing historical monuments. The combination of reality and fiction facilitates the construction of a narrative regarding the city’s founding, predominately influenced by the legends of Senius and Aschius, through the appropriation of written records and sculptural monuments attributed to Chonwolf from the Middle Ages onwards. While ensuring that the city lived up to its divine origins, Siena continued to promote the sacred narrative of Saint Ansanus, emphasising the long historical links between the Sienese faith and Christian culture. The intricate historical narrative, reinforced through public artistic expressions and civic rituals, ultimately shaped Siena as a fusion of Roman divine heritage and Christian virtues. By strategically positioning monumental artworks in civic spaces—such as the frescoes of the Palazzo Pubblico and the ubiquitous she-wolf iconography—these legends were visually embedded into the city’s identity, setting Siena apart amid the intense city-state rivalries of the early modern period.

Furthermore, the public space was used for artistic promotion. The use of murals, music, and sculpture helped to create a standard urban memory for all Sienese through visual, auditory, and tactile means. For example, the statues and frescoes of the Town Hall and the floor paintings of the Cathedral of Siena in the public space are closely linked to the lives of the citizens, and this artistic propaganda, which penetrates everyday life, allowed the whole of Siena to participate in the construction of its historical vision and identity. By narrating the city’s history through legends, the Sienese replaced their original “foreign” origins with an urban narrative more aligned with the city’s identity as the progeny of Roman gods and the land of saints. The composition of Siena’s urban history serves as a ‘fictional’ narrative and an unseen ‘war’, enhancing its external image and internal cohesion.

Italy’s national identity, characterized by its historical fragmentation, is intricately intertwined with the narratives of its city-states. Within these local mythologies and legends, a pivotal role has been played in shaping the collective consciousness of the nation. As Patrick J. Geary (Geary 2018, p. 115) observes, Italy’s failure to achieve national unification in the early modern period has positioned it on the periphery of European historiographical discourse. This fragmentation, however, is not merely a political failure; rather, it has been continuously reinforced by historical myths that shape distinct local identities, a phenomenon that persists today. The legend of the Sienese she-wolf (lupa senese) serves as a paradigmatic example, illustrating how myth became a central element of urban identity and was employed to resist external power.

This legend was employed throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance to assert Siena’s independence and played a key role in reinforcing collective consciousness amid political and military conflicts with Florence. The image of the lupa senese remains prominently displayed in Siena’s public spaces—including fountains, squares, and official insignia—symbolising the city’s distinct identity. Despite Siena’s subsequent annexation by Florence in 1555, the legend persisted, continuing to influence local historical consciousness. In contrast to the gradual integration of regional histories into national narratives observed in other European nations, Italy’s historical memory remains highly fragmented. Different cities and regions continue to preserve their own historical myths, which serve as the foundation of local identity.

The enduring presence of the she-wolf legend exemplifies the resilience of regional identity in Italy, which has remained more pronounced than national identity. This legacy is not only a reflection of Siena’s historical memory but also an indicator of Italy’s persistent struggle to construct a cohesive national identity. This persistence of local identity through myth can be observed in contemporary Italy, where historical narratives continue to shape regional identities and political discourse. While other European nations integrated their regional histories into cohesive national myths, Italy remains a patchwork of competing local identities, each with its own historical legitimisation. The continued prominence of the Sienese she-wolf in public monuments and civic rituals demonstrates how historical memory, once a tool of political cohesion, can also function as a mechanism of differentiation, contributing to the fragmented nature of Italian national identity today.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The “Constructivism” theory, as proposed by Hayden White, posits that the act of writing memory constitutes a form of “fiction” and “myth.” Conversely, the concept of “Material Mediators” encompasses the cultural landscape, which refers to the process by which humans reconstruct space by embedding elements such as customs, traditions, and lifestyles into the landscape. This process, therefore, results in the landscape becoming not only a material heritage but also a new cultural heritage, with the capacity to connect historical memory. See: Zhao (2021). |

| 2 | The claim that Siena originated from the Franks can be traced to the 12th-century English scholar John of Salisbury. In the sixth book of his Policraticus, he attributed the city’s founding to the Gallic leader Brennus. This account was later embraced and widely disseminated during the Renaissance by notable figures such as Giovanni Villani, Dante, and Boccaccio. Criticism of Siena’s historical narrative often highlights its alleged bloodline connection to France, contrasting it with the Roman heritage traditionally linked to Italy (John of Salisbury 1990, pp. 6, 17). |

| 3 | Ansano/Ansanus (285–304 AD) was a Roman nobleman by birth and is regarded as the first Christian to preach in Siena. He is believed to have been persecuted and martyred in Siena by the Roman Emperor Diocletian, making him the first patron saint of Siena. Ansano’s martyrdom marks a significant turning point in Siena’s transition from the Roman Empire to Christianity. His identity embodies both the universality of the Christian faith and the religious transformation of the late Roman Empire. In commemorating Ansano, Siena affirms its commitment to early Christian heritage and, through his martyrdom, situates itself within the historical context of the Christianisation of the Roman Empire. This narrative not only reinforces Siena’s religious orthodoxy but also challenges any notion of Siena’s historical absence, ‘localising’ the transformation of Rome and subtly linking the city’s origins to that of Rome. |

| 4 | The earliest recorded seal depicting the She-Wolf and the Twins is dated 1344 (Miscellanea storica senese 1895, p. 195). |

| 5 | The secular and the religious were not strictly opposed during this period, as illustrated by another of Siena’s religious symbols—the Virgin Mary. Her image was not merely a vestige of religious tradition but a political instrument deliberately employed by the government of the Nine to reinforce its authority. This is particularly evident in the Marian frescoes of Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico, where religious symbolism was not simply preserved but actively integrated into municipal governance. These frescoes ascribed to the Virgin a protective role over the city and its government, transforming religious imagery into a means of legitimising political power. Rather than discarding religious elements, the Nine strategically incorporated the figures of the Virgin Mary and Saint Ansanus into civic identity, intertwining religious devotion with secular governance to consolidate their rule (Bohn and Saslow 2013, pp. 71–72). |

| 6 | The Roman Porta, which exists today in Siena, was built in August 1328 by Agnolodi Ventura and Agostino di Giovanni to replace the destroyed Porta di San Martino. Differences in sculptural form: Roman she-wolves tend to have their heads tilted to one side, while those in Siena are in a forward position. |

| 7 | At the close of the 14th century, Milan and Florence were embroiled in conflict, with the polemics of their respective humanists expanding the battlefront to culture and public opinion. Notably, Antonio Loschi (1365–1441), secretary to the Duke of Milan at the time, published L’Invectiva in Florentinos (Reproach to the Florentines), to which Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406), secretary of state in Florence, responded with a rejoinder, thereby sparking further polemics. Loschi argued that Milan had a more ancient Roman heritage than Florence and denounced the republican myth of Florence’s supposed inheritance of Roman tradition as a later fabrication. He pointed out that Florence, despite its republican identity, was also expansionist and allied with France, demonstrating Florence’s hypocrisy and lack of a clear Italian stance. For Sarutati’s reply to Loschi, see: Coluccio Salutati (2014). |

| 8 | The official tourism website and brochures of Siena feature the city’s origins through the legend of the twin brothers Aschius and Senius. Resource: https://visitsienaofficial.it/siena-toscana/ (11 October 2024) “Una leggenda avvolge le origini di Siena: è quella di Senio e Ascanio, figli di Remo e nipoti di Romolo, che avrebbero fondato la città dopo essere fuggiti dalle intenzioni omicide del loro zio a Roma, portandosi dietro il simbolo della Lupa capitolina, che per questo motivo è divenuta il simbolo di Siena come Lupa senese”. |

References

- Achilli, Alessandro, Anna Olivieria, Maria Palaa, Ene Metspalub, Simona Fornarinoa, Vincenza Battagliaa, Matteo Accetturoa, Ildus Kutuevb, Elsa Khusnutdinovac, Erwan Pennarunb, and et al. 2007. Mitochondrial DNA Variation of Modern Tuscans Supports the Near Eastern Origin of Etruscans. American Journal of Human Genetics 80: 766–67. [Google Scholar]

- Alighieri, Dante. 1991. Commedia: Inferno. In Letteratura italiana Einaudi. Edizione di riferimento: I Meridiani, I edizione. Milano: Mondadori, p. 699. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Carol A. 2019. Sacred Histories: Remembering the Christian Past in Medieval Tuscany (1100–1500). Washington, DC: The Catholic University, pp. 249–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ascheri, Mario, and Bradley Franco. 2020. A History of Siena: From Its Origins to the Present Day. New York: Routledge, pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Aleida. 2002. The History in Memory: From Personal Experience to Public Presentation. Translated by Siqiao Yuan. Nanjing: Nanjing University Press, p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- Bargagli Petrucci, Fabio. 1906. Notizie di un Arco Romano in Siena. Rassegna D’arte Senese, vol. 2, It was not until the 19th century that archaeological techniques, through the analysis of fragments in the columns, established that these columns were in fact 15th century works and not the remains of the so-called Roman colonial period.

- Bartfield, Herbert. 2012. The Whig Interpretation of History. Translated by Yueming Zhang, and Beicheng Liu. Beijing: The Commercial Press, pp. 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Baluze, Etienne, and Giovan Domenico Mansi, eds. 1764. Stephani Balugii Tutelensis Miscellanea: Noro ordine digesta et non paucis ineditis monumentis opportunisque animadversionibus aucta. Sancti Ansani, trans. Lucae: Junctinium, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Beneš, Carrie E. 2011. Urban Legends: Civic Identity & the Classical Past, 1250–1350. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bezzini, Mario. 2015. Controversia territoriale tra i vescovi di Siena ed Arezzo dal VII al XIII secolo. Florence: Il Leccio. Available online: https://www.unilibro.it/libro/bezzini-mario/controversia-territoriale-vescovi-siena-ed-arezzo-vii-xiii-secolo/9788898217380?srsltid=AfmBOopf-Ab_0u5c7mTJ6nE6zQPxL94IrRlwWJ_6lrfH5Raw6dhKBRfN (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Biccherna. 1344. Tavole di Biccherna. Siena: Archivio di Stato di Siena, No. 215, c. 148. December 20. [Google Scholar]

- Biondo, Flavio. 2005. Italy Illuminated. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Boccaccio, Giovanni. 1846. Chiose sopra Dante. Firenze: Tipografia all’Insegna di Dante, pp. 241–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bohn, Babette, and James M. Saslow, eds. 2013. A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bowsky, William M. 1981. A Medieval Italian Commune: Siena Under the Nine, 1287–1355. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Peter. 2019. History and Social Theory. Translated by Li Kang. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- Caferro, William. 1998. Mercenary Companies and the Decline of Siena. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cantucci, Giuliana. 1961. Considerazioni sulle trasformazioni urbanistiche nel centro di Siena. BSSP 68: 251–62. [Google Scholar]

- Casciani, Santa, and Heather Richardson Hayton, eds. 2021. A Companion to Late Medieval and Early Modern Siena. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, Keith, Laurence B. Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke, eds. 1988. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art: Distributed by H.N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Coluccio Salutati, Rolf Bagemihl, trans. 2014. Political Writings. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connerton, Paul. 2000. How Societies Remember. Translated by Nari Bilige. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- D’Accone, Frank A. 2007. The Civic Muse: Music and Musicians in Siena During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Montaigne, Michel. 2017. The Complete Essays of Montaigne. Translated by Ma Zhencheng. Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- de Roover, Raymond. 1942. The Commercial Revolution of the Thirteenth Century. Bulletin of the Business Historical Society 16: 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Langton. 1902. A Story of Siena. New York: E.P. Dutton Company. [Google Scholar]

- Frugoni, Chiara. 2019. Paradiso vista Inferno: Buon governo e tirannide nel Medioevo di Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Funari, Rodolfo. 2002. Un ciclo di tradizione repubblicana nel Palazzo Pubblico di Siena. Le iscrizioni degli affreschi di Taddeo di Bartolo (1413–1414). Siena: Accademia Senese Degli Intronati. [Google Scholar]

- Geary, Patrick J. 2018. History, Memory, and Writing. Translated by Xin Luo. Beijing: Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gori, Giovanni Battista. 1576. Vita del gloriosissimo S. Ansano: Uno de li quattro Avvocati e Battezzatore de la città di Siena. Siena: Luca Bonetti, p. 2. Available online: https://edit16.iccu.sbn.it/resultset-titoli/-/titoli/detail/CNCE21468 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Gigli, Girolamo. 1732. Diario Senese, vol. 2. Bologna: Arnoldo Forni. [Google Scholar]

- Gigli, Girolamo. 1854. Diario Senese (1723). Bologna: Arnoldo Forni. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, Max Elijah. 2006. Pro Honore Comunis Senensis Et Pulchritudine Civitatis: Civic Architecture and Political Ideology in the Republic of Siena, 1270–1420. New York: Columbia University, p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini, Roberto. 2000. Dulci pro libertate. Taddeo di Bartolo: Il ciclo di eroi antichi nel Palazzo Pubblico di Siena (1413–1414). Tradizione classica ed iconografia politica. Rivista Storica Italiana 112: 510–68. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood, William. 1924. Guide to Siena, History and Art, 4th ed. Siena: Libreria. [Google Scholar]

- Hoare, Sir Richard Colt. 1819. A Classical Tour through Italy and Sicily, 2nd ed. London: J. Mawman, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- John of Salisbury. 1990. Policraticus. Edited by Cary J. Nederman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 6, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Geraldine A. 2015. Art of the Renaissance. Translated by Li Jianqun. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Philip. 1997. The Italian City-State: From Commune to Signoria. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lassels, Richard. 1670. The Voyage of Italy. Paris: John Starkey. [Google Scholar]

- Lisini, Alessandro, and Fabio Iacometti, eds. 1931–1939. Rerum Italicarum Scriptores. Bologna: Forni Editore, vol. 15, Part 6. [Google Scholar]

- Magdalino, Paul. 2002. The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143–1180. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Malavolti, Orlando. 1968. Dell’Historia di Siena (1594). Bologna: Forni. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1948. Magic, Science, and Religion and Other Essays. Beacon: Beacon Press, pp. 125–26. [Google Scholar]

- Miscellanea storica senese, vol. 1. 1893. Siena: Stab. Tip. Carlo Nava.

- Miscellanea storica senese, vol. 3. 1895. Siena: Stab. Tip. Carlo Nava.

- Milanesi, Gaetano. 1873. Sulla Storia Dell’Arte Toscana: Scritti varj. Siena: Davaco Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, Lewis. 2004. The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. Translated by Junling Song, and Wenyi Ni. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press, p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- Nevola, Fabrizio. 2000. Revival or Renewal: Defining Civic Identity in Fifteenth-Century Siena. In Shaping Urban Identity in Late Medieval Europe. Edited by Marc Boone and Peter Stabel. Leuven: Garant Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Nevola, Fabrizio. 2008. Siena: Constructing the Renaissance City. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 157–73. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Gerald. 2004. Siena, Civil Religion and the Sienese. Derbyshire: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Gerald. 2006. Civil Religion and the Invention of Tradition: The Festival of Saint Ansano in Siena. Journal of Contemporary Religion 21: 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, Samantha. 2023. Popular Participation in Renaissance Siena’s Romanitas Program. Explorations in Renaissance Culture 49: 175–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondoni, Giuseppe. 1886. Tradizioni popolari e leggende di un comune medioevale e del suo contado: Siena e l’antico contado senese. Firenze: Uffizio della Rassegna nazionale. [Google Scholar]

- Schevill, Ferdinand. 1909. Siena: The History of a Medieval Commune. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Sozzini, Alessandro, ed. 1842. Diario delle cose avvenute in Siena dal 20 luglio 1550 al 28 giugno 1555. Firenze: Gio. Piero Vieusseux. [Google Scholar]

- Starn, Randolph, and Loren Partridge. 1992. Arts of Power: Three Halls of State in Italy, 1300–1600. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff, Judith B. 2000. Sienese Painting After the Black Death: Artistic Pluralism, Politics, and The New Art Market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart, Simon K. F. 2009. Historical Dictionary of the Etruscans. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press. [Google Scholar]

- Toynbee, Paget, ed. 1903. The Letters of Horace Walpole. Fourth Earl of Orford, vol. 1, Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trombelli, Joanne Chrysostomo, ed. 1766. Ordo Officiorum Ecclesiae Senensis ab Oderico ejusdem ecclesiae canonico anno MCCXIII compositus. Bologna: Ex typographia Longhi, pp. 304, 273. [Google Scholar]

- Villani, Giovanni. 1991. Nuova Cronica. Edited by Pietro Bembo. Parma: Guanda, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, Diana. 1996. Patrons and Defenders: The Saints in the Italian City-States. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Ming. 2023. Carnival in Rome: The Tension of Pope Paul II’s Dual Role Revisited. Religions 14: 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdekauer, Lodovico. 1897. Constituto del commune di Siena dell’anno 1262. Milano: U. Hoepli. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Zhengyuan. 2021. Cultural Landscape and Urban Memory: The Memory Reconstruction of Pukou Railway Station in Nanjing. Historical Review 6: 91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Jingwen, ed. 2010. Introduction to Folklore, 2nd ed. Beijing: Higher Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Ming. 2011. From Cathedral to City Hall: The Spatial Transformation of Siena in the Late Middle Ages. Historical Research 5: 113–25. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).