Abstract

Around the figure of Zöhre Ana, a contemporary female mystic in Ankara, Turkey, considered by her followers a saint and known for her healing powers, has grown a substantial cult followed by hundreds if not thousands of devotees, with its own mythology, cosmology, discursive tradition, and praxis. As with any religiocultural tradition, the cult of Zöhre Ana has developed a unique experiential world at the interface between her and her followers that engages all of the senses of participants. This study explores the visual dimension of this world, consisting specifically of the visions Zöhre Ana has had, the visible setting of the cult in specially arranged physical space, and the iconography of the saint. The visual elements of these dimensions reflect the Alevi cultural–historical milieu she and most of her followers come from, and this shapes the experience that occurs as participants interact with the visual world of Zöhre Ana.

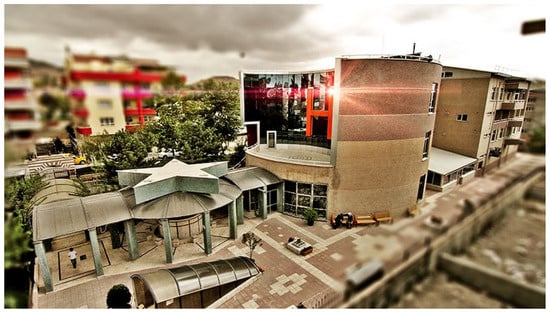

Seen from above, the structural form of the three-story building would reveal the shape of a star and crescent, the emblem of the modern Republic of Turkey. From the front, the curve of the crescent conveys the eyes to an imposing central red letter H—obviously symbolic but with no immediately obvious referent, though those who frequent the building will tell you it stands for Hızır, the mythical immortal figure said to possess knowledge of the unseen. Entering into the foyer, one walks through a gift shop selling framed pictures of a particular woman, past dozens of people waiting to see the woman in person, and in through the door of a large ceremonial room where at the other end one might catch a glimpse—sitting upon a throne-like seat beneath portraits of Shi‘i religious figures and the founding president of modern Turkey—of the woman herself: Zöhre Ana. Who is she? Why do large numbers of people come to see her? What happens when they are there? And how do they see her? By exploring these questions, we can reveal something of the visual world of Zöhre Ana and the experience that occurs within it.

Born Süheyla Höke in 1957 in a village in the central Anatolian province of Yozgat, Zöhre Ana moved at a young age to a semi-urban district on the outskirts of Ankara called Mamak, where she married and started a family. In 1982, however, she is said to have had her first ecstatic experience and soon came to be known for her healing powers. Visitors began to pour in, and, to accommodate the growing numbers, she eventually moved her operations from her home first to a repurposed complex formerly used as a coal distribution facility, and later to her own enormous specially designed “Service Building” (Hizmet Binası). Visitors, sometimes numbering hundreds per day, come seeking healing or just to see Zöhre Ana, and are guided there by the numerous staff who volunteer their time out of devotion to the saint, often because they themselves were healed. Besides her mystical experiences and her healing services, she has taken on the role of spiritual and ritual leader, even leading cem rituals in the fashion of the Alevi tradition that she and most of her followers come from. In the traditional Alevi milieu, it is rare for a woman to assume such a role, which is usually an inherited one among men of certain lineages. And uniquely, she did not reach this position because of her status as some man’s wife or daughter, but because of her own charisma, her healing abilities, and because she is seen as an evliya, a saint—someone who lives in this phenomenal world but has experiences that put her in contact with the noumenal world, and shares these experiences or passes on their benefits back in this world.1 She is even known by the title of pir—usually reserved for great men with spiritual authority, either living or dead. With her status as an evliya or pir she is of course treated with the utmost respect—those visitors seeking healing approach her crawling on the floor. Her healing power is enacted as she waves a green cloth over them, though she has stated that the cloth is just for show and that what is actually effective is the prayer she makes for them. Those who frequent her complex, both visitors and those who volunteer their service, are emphatically devout, and swear by her powers, often illustrating this by sharing their own personal accounts of being healed or witnessing miracles.2

It can thus be said that a cult has formed around the figure of Zöhre Ana, and that the basis of the cult is experience.3 The formation process begins, naturally, with Zöhre Ana’s own experience: her slipping into an ecstatic state, seeing visions, interacting with long-dead saints, uttering ecstatic verses, and dispensing healing. Such extraordinary experiences—which are, it should be noted, mediated through the mostly verbal reporting of herself or witnesses—mark her as charismatic and thus draw people to her. As her attractive power is maintained and people continue to come, a cult begins to form and organize around her. Things take shape and fall into patterns—guided mostly by Zöhre Ana and those in her inner circle, but necessarily resonant with the expectations of the milieu in which they occur. Aspects of the cult that form in this way include: a characteristic discourse of explanation, with certain terms, expressions, and tones assumed when giving meaning to the experiences that occur there; a mythology—a set of narratives of Zöhre Ana’s experiences, told, heard, repeated, written down, and read; a cosmology—an understanding of a universe consisting of two worlds: the one in which we live and the other, to which Zöhre Ana and other saints have access; and a praxis—a style of appropriate conduct in interactions between devotees and the saint, and ritual forms followed on special occasions. More materially, the space in which the cult meets likewise takes a certain shape, being arranged for the emplacement of people and things and the performance of actions intended by the cult; the space thereby begins to reflect the character and symbolism of the cult and can thus be said to represent it. All of this then becomes the world in which devotees, coming together, experience Zöhre Ana, the cult, and themselves as part of it—within a patterned ordering of intended experience.

The Zöhre Ana cult has formed within a particular social, cultural, religious, political, and historical milieu, elements of which are reflected in the various aspects of the cult. The religious background that Zöhre Ana comes from is that of the Alevis, a minority community in Turkey and surrounding countries that shares much of its discourse with the Islamic, especially Shi‘i and Sufi, tradition, yet in terms of practice diverges substantially from the Sunni majority that dominates Turkey.4 Her discourse thus follows specifically Alevi discursive patterns and motifs, with emphasis on figures revered in Shi‘i Islam such as Ali, Hüseyin, the Twelve Imams, and the holy family of the Ehl-i Beyt, along with particularly Alevi and Bektashi saints and poets, as well as aligning in part with a broader Sufi mystical discourse. Most of her devotees are likewise Alevi, though there are Sunnis as well, and the cult, while presenting many Alevi symbols, emphasizes its lack of discrimination against any other religious or cultural group and its welcoming attitude toward all. The arrangement of her cultic space and the rituals that take place there also derive in large part from Alevi tradition. Along with the Alevi–Sufi aspect come certain expectations for what saints should be and how they should be treated, and Zöhre Ana and her cult fulfill these through the arrangement and symbolism of the cult, especially in the presentation of a distinct mystique—a mystical, mysterious, esoteric, otherworldly air about her and the cult. The Alevi–Sufi tradition also brings expectations regarding the functions of a dergâh (Sufi lodge) and the social responsibility that this entails, which are reflected in the organization and operation of the Service Building. In addition to the Alevi–Sufi factor, the cult has emerged in the context of modern republican Turkey, and—as is so often the case among Alevis—has come to emphasize the motifs and values of the Republic: Atatürk as a leader (in fact, a saint, according to Zöhre Ana discourse), patriotic Turkish nationalism, secularism, and various aspects of modernism. So, as Zöhre Ana and her followers interact within the context of the cult, what they experience is shaped in part by these forces, though since most of them are themselves Alevi, their experience in this context is in large part one of reinforcing, or reiteration. Zöhre Ana has emerged at the nexus of these forces and has found her niche there. The cult in its organization reflects this, and an important part of how this occurs is through the experiential mode of vision.

Within the arrangement of the cult, people act and talk and sense and feel, and from the repetition of these occurrences, an experiential world has emerged—a patterned tradition of people engaging with an ordered environment and with others within it, and being thereby affected by the experience. Much of this experiential world involves the senses—all of the senses in fact—so we can speak of a cultic aesthetics. And perhaps the primary element of this aesthetics is the visual. The visual aesthetics includes many aspects—what people see, how they are directed to see, and how the motif of sight operates in their discourse—and all of these make up the visual world of the cult. It is perhaps relevant that the name the saint has taken in lieu of her given name is Zöhre, the name of Venus (the brightest “star” and the first to appear in the evening), which comes from the Arabic root meaning becoming manifest or visible, and is related to the Sufi term zahir (the manifest) as opposed to batın (the hidden). What she does cosmologically and experientially is to operate at the crux of a process: She sees otherworldly realities in the batın realm, and then expresses her visions—makes them manifest—to her followers in the zahir realm. The manifestation passes through various media—verbal discourse, photographic images, spatial arrangement—and takes various forms. Her followers, as they experience these forms, are induced to see aspects of what she is purported to have seen and are thereby affected by this transmission of vision.

The visual world of Zöhre Ana is complex, but we can perhaps see it more clearly by looking at it from three perspectives. The first—maybe the starting point of the whole process—would be what Zöhre Ana herself sees (and others hear reported)—that is, her vision. The second might be what the cult has arranged for her devotees to see her and themselves in the midst of, the mise-en-scène of the cult—that is, a vision of her world as reflected in physical space. The third would then be what her followers are led to see her as—that is, a vision of her in the light of all of this. These are some of the aspects of the visual world of the Zöhre Ana cult, and in describing them, we can draw for material from several sources, most of which can be considered authoritative for the cult, including the books written by and about her, her voluminous poetry, and information and images from her official website and social media pages,5 along with the views of some of her devotees and observations of the physical space gained from several visits to the Service Building. We can then explore how all of these visual phenomena come together in practice.

What Zöhre Ana Sees

Zöhre Ana is known to on occasion slip into a state of ecstasy that occurs all of a sudden, without the stimulation of any ritual or substance or, seemingly, any external prompt at all. Her going into ecstasy is referred to in the cult’s discourse as ummana dalmak—“plunging into the Ocean”—and it is in this state of ecstasy, the umman or Ocean, that she sees her visions. Since this is a personal, subjective, and not immediately disclosed experience, what exactly happens in the Ocean and what she sees are ultimately known only to her; others have only what has been reported to rely on, with the inner aspect of her experiences related by her own accounts and expressions, and the outer aspect by the accounts of those who witness them—and all of these reports are expressed verbally. The process is then one of experience followed by expression. While the accounts of witnesses to Zöhre Ana in this state are usually reported in prose narratives, her own accounts are expressed through various forms of discourse, including after-the-fact prose accounts, but also in-the-moment ecstatic utterances, which often take verse form. The verbalizations are processed through the discourse of the milieu the cult operates within: the Alevi–Sufi mystical idiom. She thus interacts with mythological figures from the Alevi pantheon, such as Ali, the preeminent Anatolian saint Hacı Bektaş, and the great Turkish mystical poet Yunus Emre, as well as the modernist saint of the Republic, Atatürk. The verse utterances likewise fall in the form of fragments of Turkish lyrical poetry, drawing on themes and phrasings of the Alevi mystical poetic tradition. Sometimes her experience leads her to utter unintelligible language—what in English might be called speaking in tongues, but among her cult is said to be Persian, though supposedly in an archaic form not recognizable to contemporary Persian speakers. In whatever form the expressions take, we are left with verbalizations with which to surmise what the actual experience and vision would have been. We hear, or read, what she sees.

To get an idea of what she sees in the Ocean, we can examine her first ecstatic experience, which she related to journalist İsmet Solak in the book Cemden Gelen Nefesler (“Breaths Coming from the Gathering”), published in 1991 with her approval. In Solak’s (1991, pp. 87–88) report of her account, Zöhre Ana recalls:

We can see from Zöhre Ana’s description that her first ecstatic experience was a multisensory one. It begins with hearing sounds, and this is what tips Zöhre Ana off that it is to be an otherworldly experience. Later, in the matter of the stove, it involves touch, and this too leads to an extraordinary experience, as the burning hot stove does not in fact burn Zöhre Ana when she embraces it. There is also an undefined sense she has, an awareness: “as if” there were another present. But after feeling that presence, she seeks to confirm it with sight—“I couldn’t see,” she notes, and begins to search—and we find the dominant sensory mode of the experience: vision. This works through the motif of light; the experience report begins with the lighting of a lamp, the sudden appearance of a green smoke, and seeing the nur—the divine, mystical light—which serves as the key sign of the otherworldly experience. The visual mode also allows her to highlight the otherworldly aspect by contrasting it with this-worldly perception: “I see the light, but I also see the house.” And in the end, just before she returns to this world and her children, she sees the effects of the nur displayed on the walls in the form of a spread of color. Vision allows her to experience the otherworld and to report it to others in this world.Just as I was lighting the lamp, I began to hear the sounds that I had been hearing for a few days but had not told anyone of. It was as if somebody were inside. But I couldn’t see. I began to search. As I lit the lamp, everywhere was covered by a green smoke. I didn’t know the nur [the divine light] was in the house. I see the light, but I also see the house. Because the stove was burning hot I ran and embraced it. The stove was in its place. It didn’t burn me. I recited a besmele [Islamic invocation] and sat on my knees. That nur became smoke and was spread to the walls with colors like a rainbow. The stove was in its place, my children were looking with wonder. I pulled myself together. I gave them their dinner.

Her ability to see in both realms simultaneously also proves to her that this is a real experience, and not a dream, as she continues:

So, we see that Zöhre Ana’s first vision was, in her telling, like a dream but at the same time real, including mystical elements like a supernatural light and an association with a great saint, but also real, normally visible sights like her house and the table, which she touches. The account of her initial experience that night then continues toward morning with her being introduced to a group of saints. One of them announces to her, “You will be heard and spread around the world. We are opening this place as a convent to those who love, those who respect, those in need. And you will give healing to those who come” (Solak 1991, p. 89). She thus receives her calling. When she awakens in the morning, she tells her family what she has seen, but they do not at first believe her. So, the gist of Zöhre Ana’s first mystical experience is that she can see what is otherwise unseen.I woke up again. I am aware that I am in the house but I also see that it is the convent of Hacı Bektaş [the great Alevi-Bektashi saint], and I see the table in the house. On one side I see a convent. I am holding the table. So I am not in the realm of dreams.(Solak 1991, p. 88)

We see these themes recur when we look to her subsequent experiences in the umman, the ocean of ecstasy, most of which are not documented with the level of first-person prose narrative detail her initial experience elicited. Often, she would speak while in the Ocean—sometimes in incomprehensible speech, other times in Turkish poetic fragments—and it is from these verbal traces of her ecstasy that we can get some sense of what she experienced and saw there. Many such experiences are reported by the above-mentioned journalist, who, when preparing his book, accompanied her on trips to her home village and to the tombs of certain saints. She would go into ecstasy and utter the poems, which the journalist recorded, adding his own prose account and commentary. In his reporting (Solak 1991, p. 14), episodes would transpire in this manner:

Beyond Zöhre Ana seeing them, though, the saints often seem to possess her, or to speak through her. She is quoted (Solak 1991, p. 179) as describing what is happening thus: “How would I know these things? In the Ocean, the saints speak and I transmit.” Often in the poems (Zöhre Ana 1996, p. 227), the voice will even refer to Zöhre Ana in the third person—as Zöhrem, “my Zöhre”:

Zöhre Ana might here appear as an image, but she has been removed from the poetic voice, and we appear to be hearing directly from the saints inhabiting the otherworld—which shatters the subject–object dynamic of a normal experience.

Zöhre Ana then begins to speak in Turkish, apparently in conversation with saints unseen in this world, and eventually her words take poetic form, usually in quatrains, as is typical in Alevi poetry. Though the verses are fragmented and shift topics and even voices abruptly—as one might expect from in-the-moment ecstatic utterances—through this record we can picture the world she goes to: it is a world populated by saints, and usually it is the saints that she sees. In one quatrain (Solak 1991, p. 18), she reports:Then she looked at a spot on the wall. I was taken aback. As for Zöhre Ana, she plunged into the Ocean. She muttered some things I didn’t understand. I turned on the tape recorder. Her brother Hasan Aydoğan explained: “That’s Persian … But it’s not the Persian we know. Only Ana speaks this, Ana deciphers it.”

| Her ırmak Şahı Ali | The Shah of every river, Ali |

| Dört kapının Piri Ali | The Pir of the four doors, Ali |

| Ben Ali’yi gördüm dostum | I saw Ali, my friend |

| Kemer bestim Allah belli | My girded one, Allah, certain |

| Oturur köşede ötüşür benle | (S/he) sits in the corner, sings with me |

| Ben görünmem, Zöhrem görünür size | I don’t appear, my Zöhre appears to you |

In one poem—titled Çağırayım Alim Seni (“I call to you, my Ali”)—that is set to music and recorded on her first cassette with her singing, at one point in the flow of semi-structured ecstatic verses, is a section that goes:

Here, we hear another voice shift, as the poet alternates between the first- and third person. The lines she sings in the first-person both use the verb okumak, which can mean either to read or to recite; since the object of the first line is the Four Books (of the monotheistic religions, according to Islam), the line might refer to either reading the books (and thus the “I” understands all of religion), or reciting them (and thus the “I” has internalized all of religion and is now expressing it with these words), while the latter first-person line clearly claims that the words spoken (nefes means literally breath, but refers in the Alevi context to mystical poetry) are divine, and the poet is commenting on the mystical character of the expression. But with the repeated line—“Zöhre Ana’s in the Oceans”—the voice pivots to the third person, and comments on the ecstatic state, the experience, that brought about the expressions previously mentioned, reporting it as if the voice were witnessing it, seeing Zöhre Ana as an object in this state. Is this Zöhre Ana’s voice abstracted from self-consciousness? Is it the voice of some other being in the otherworld seeing Zöhre Ana in this state and commenting on her experience, using her poem as a vehicle? Has another being possessed her? Zöhre Ana is the subject of the experience described, but who is the subject of the expression of it? Who has therefore seen her?

| Dört kitabının okurum | I read/recite the Four Books |

| Zöhre Ana ummanlarda | Zöhre Ana’s in the Oceans |

| Allah’tan nefes okurum | I recite a breath from Allah |

| Zöhre Ana ummanlarda6 | Zöhre Ana’s in the Oceans |

Setting aside the search for the logical implications of ecstatic utterances, the effect that this has on us, the audience, is that we can see in our mind’s eye the image of her in the Ocean, but since the words are now coming out of her mouth, it is as if she is seeing herself in the Ocean and reporting that sight to us. So, when we hear her, we see her, as she sees herself.

Whatever the particular voice entails, we are left with expressions of an extraordinary experience. We are led to understand that Zöhre Ana has seen/experienced the umman, the otherworld—what is inaccessible, inexperienceable, invisible for most people. This experience is then expressed in words, whether the prose accounts of eyewitnesses or the ecstatic utterances of Zöhre Ana herself. It is the witnessing of her in this state and the hearing expressions of it that set her apart and draw people to her. The verbal expressions have been written down, and this constitutes the material of the mythology of the cult around her. A hearing or a visual reading of this verbal material produces a mental image in the receiver—a vision received, so that a version of the experience has been transferred to an audience through words. The audience—individuals, really—perceive the image, sense the extraordinary essence of the experience imagined, feel an attraction to the subject of that experience, and then—if adequately affected—become devotees of Zöhre Ana. Her vision is part of her attractive power, a mobilizing force in the formation of her cult.

Where Zöhre Ana Is Seen

Once sufficient devotees are attracted and the cult begins to form, a mythology, cosmology, social organization, and praxis also begin to take shape. These are put into practice when Zöhre Ana and her devotees come together, and this has to occur in a space. The space, then, along with the other facets of the cult, also begins to take shape, and its arrangement comes to reflect certain aspects of the cult. When people gather there and act, they see Zöhre Ana in this setting, which serves to frame how she is seen. We can then take this spatial arrangement as a second aspect of her visual world—the mise-en-scène of the cult—and explore what it highlights and how it does so. Like the visions Zöhre Ana sees that we understand through reports of them, the space is arranged in certain ways: designed by Zöhre Ana, but executed by managers, architects, contractors, workers, and serving devotees. It is through the forms produced in this manner that observers see the cult. And just as Zöhre Ana’s visions reflect the Alevi–Sufi mythology and cosmology along with other features, the cult’s spatial arrangement likewise reveals aspects of the milieu in which it has emerged.

Seeing requires space, which helps establish relations between things, and thereby allows for perspective. We see an object within an environment, and in relation to other things in the same environment, so how is an intentional space such as that of a cult arranged to facilitate the intended visions? It involves distancing, hierarchization, and orientation as it draws attention to certain people, places, things, and actions, emplacing them with respect to others. When occasions come up and practice occurs there, participants then have the opportunity to experience—to see—what is intended as it is intended. So, how is the Zöhre Ana cultic space arranged, and what might thereby be intended?

The space that has come to house the operation of the Zöhre Ana cult—replacing her home, and then the converted coal distribution facility—is a large three-story building known as the Hizmet Binası—the Service Building—with a small garden in front and the entire complex being surrounded by a wall (see Figure 1). The complex, completed in the late 1990s, is said to have been designed by Zöhre Ana herself, so the symbolism we see in its structure can be attributed to her as the instigator, and be seen as reflective of the cult. As mentioned above, the front section of the building, when seen from above, is constructed in the shape of a crescent moon, with a star atop the ablution fountain opposite its tips to complete the Turkish national emblem. As few would see the two-dimensional star-and-crescent image from above, the effect this design has on most visitors looking at and entering the building would be the sense that one is within a three-dimensional star-and-crescent, immersed in the national symbol.

Figure 1.

Zöhre Ana’s Service Building, Ankara.

But when one looks up at the inside of the crescent, one sees a large, prominent red letter H, which is said to stand for Hızır (Khidr), the immortal figure popular especially in mystical strains of Islam like Alevism, who is understood as having access to knowledge of the unseen. There is thus a mysterious mythological sign branded on the inner face of the modern national emblem, providing a fair introduction to the complex idiom of the cult of Zöhre Ana. This dual nature of the cult’s presentation is mentioned proudly and defiantly in the official website’s description of the Service Building:

While the design represents Zöhre Ana’s personal vision, the Service Building, as its name might imply, is a multipurpose complex that follows the tradition of the Sufi lodge (tekke or dergâh) in providing space and facilities for various functions related to accommodating and serving visitors, and the building is in fact often referred to as the Dergâh. Since many visitors come in order to fulfill a vow, they might, following the tradition of this milieu, bring a sheep to be sacrificed and its meat cooked and distributed to other visitors. To accommodate such needs, the building includes a slaughter room and a large kitchen—both clean and with modern facilities, with great attention paid to hygiene—for preparation. A large pantry stores dry foodstuffs such as bulgur, which is usually cooked to accompany the meat of the sacrifice. There is of course a large dining hall, where every day all who visit the complex are fed, served by volunteers.

The Service Building also houses a small library, with books mostly about Alevism, and other small meeting rooms and offices, and some guest rooms. There are spaces for the performance of life-cycle rituals: a wedding hall, and a mortuary for the washing and preparation for burial of the dead. And, to support the functioning of the building, there is a gift shop where Zöhre Ana’s books, music cassettes, and other items are sold. Most of these spaces of the complex are designed to fulfill functions other than seeing: this is where people sacrifice, cook, eat, study, sleep, marry, and even lie dead. So, the levels of experience go much deeper than that of just seeing, as visitors are induced to service and social responsibility. But the spaces are arranged in certain ways and arrayed with certain symbols that allow us to see what the cult chooses to highlight as these other experiences take place.

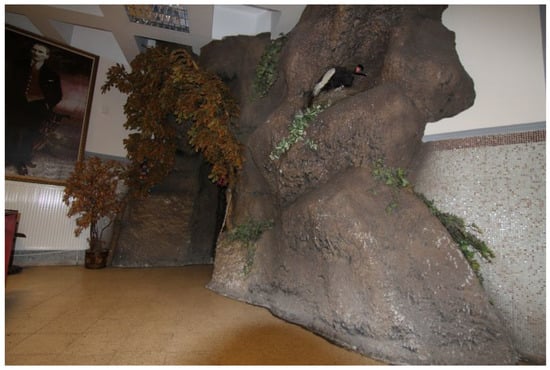

One section of the Service Building that seems designed primarily for vision, and is—perhaps for this reason—the most unique feature of the complex, is the artificial cave in its basement. On one side of the foyer, past the gift shop, one sees a mass of faux rock jutting from the wall, with a dark entryway beckoning (see Figure 2). Stepping down a staircase, the eeriness one feels while descending through the tunnel-like passageway into the mysterious unknown is tempered when one notices the colorful handmade village items bedecking the walls. Reaching the bottom, one finds oneself in a dimly lit museum of the Zöhre Ana cult—the faux rock-walled room housing a sort of ethnographic museum display, with traditional village implements strewn about, some with mannequins in traditional village costume doing traditional village work with them, while other costumed mannequins stand frozen in glass cases (see Figure 3). Combining the otherworldly and the rural-worldly motifs is a traditional-looking well—complete with an unused rope and bucket—which is reportedly an actually dug well, producing water that is supposedly equivalent to the Zamzam water of Mecca, and has its own healing powers. To one side, there is a space where Zöhre Ana, before the larger ceremonial space upstairs was finished, used to meet visitors—her sitting area raised above the floor level, marked with columns and sheepskins. And, as befitting a sacred space, there is a niche in the cave wall for votive candles to be lit.

Figure 2.

The entrance to the cave in the Service Building, Ankara.

Figure 3.

Down in the cave. Service Building, Ankara.

The cave seems to be the expression, the outward manifestation, of the theme of the mystique—the mystical, mysterious, esoteric nature of the unseen realm that Zöhre Ana has seen and experienced—and its purpose to guide visitors through it so that they see this and appreciate Zöhre Ana’s powers. But the mystique is here blended with the folkloric. This is not entirely incongruous if we remember that Zöhre Ana and many of her followers themselves come from rural backgrounds, and most subscribe wholeheartedly to the values of the modern, nationalist Republic, which idealizes the rural Anatolian past. And the integration of the mystique and the mundane might also recall Zöhre Ana’s initial vision, where she saw at the same time both the divine light and the physical house. Down in the cave, the rural nostalgic provides a this-worldly backdrop from which can be seen to emerge the otherworldly experience of Zöhre Ana. Since she no longer meets visitors there, the purpose of the cave is now solely for seeing. It is a museum one strolls through, gazing upon what is displayed.

Another space that one enters from the foyer of the Service Building is the ceremonial room, referred to on Zöhre Ana’s website as Büyük Ziyaretçi Salonu—the Grand Visitor Hall. As it is designed to accommodate large numbers of attendees at ritual events, it is indeed grand, reportedly seating 1000 people. It is a rectangular room, resembling the typical Alevi ritual space known as cemevi, in which attendees sit on the floor along the walls facing the central space, where the ritual services of the cem are conducted and the semah—the ritual dance—is performed. There are thus no chairs on the carpeted floor. Like other functional facilities in the complex, the décor even in the ceremonial hall is plain and unemphatic, with little symbolic signage on the walls. There is not much to distract attention from the central focus of the space.

It is in this space that visitors can see Zöhre Ana. Occasions for such interaction include formal cem rituals in the Alevi style, in which the central space is left open for the performance of the rites and the semah dance, and attendees are seated along the walls facing the center and at times gesture with their bodies. There are also other less structured events in which Zöhre Ana speaks and attendees listen, in which case attendees may sit in the central area as an audience facing Zöhre Ana who is seated at one end of the room. These events follow the general patterns of Alevi praxis; as Zöhre Ana and many of her followers are Alevi, it is thus an easy adaptation from what they are familiar with. What happens in this space is seen by attendees but also heard and perceived through the other senses. The audience members are at the same time themselves participating in the event, so they are experiencing the ritual at many levels, kinetic as well as sensual. But because the rituals performed here, though following Alevi cem patterns, feature the added element of Zöhre Ana’s presence, with the special status due to her charisma, she is highlighted in the space, so that visual attention is directed toward her.

For an illustration of how Zöhre Ana is highlighted in the cultic arrangement we can look to how she is positioned in the ritual space. She naturally assumes a place of distinction, separated and marked off from the rest of the space in several ways. Her place in the Grand Visitor Hall is within an ornate recess like a church sanctuary within the wall opposite the door, with the length of the room leading the eye up to it (see Figure 4). Her seating area is raised two steps above the floor of the room, and at the center of it is an elaborate armchair with a sheepskin at its foot, and this is where Zöhre Ana sits.9 The chair is flanked by flags and vases of flowers, and behind it is a niche from which looks out a portrait of Atatürk, its arch lined with pictures of the Twelve Imams.

Figure 4.

Zöhre Ana’s seating space. Service Building, Ankara.

Her positioning in this ritual space highlights her more distinctly than the traditional cemevi’s positioning of its officiant, the dede. In a typical Alevi cem, there may in fact be more than one dede, and they are usually seated next to each other, and sometimes with the musicians seated in the same section. This section might or might not be raised on a low platform, but its position is marked as privileged mostly because that is where the prayers are recited and the music and singing come from. The presiding dede is to some extent the focal point of the cem—it is toward him that attendees often face, and semah dancers bow when passing before his presence. In the Zöhre Ana space, though, the focal figure is considered a saint, and her position is thus more elevated, elaborately delineated, and separated from the rest of the space. Her magnified positioning is a sign of her charisma, which has allowed her to assume a ritual role usually performed by male dedes, whose authority is inherited and institutional. Their status might be marked horizontally in the space, but Zöhre Ana’s displays more of a vertical dimension as well. Eyes are led ineluctably toward her.

The arranged space as a whole is a reflection and a representation of the cosmic world of the cult, of the cultural–historical milieu from which it emerged, and also of the cult’s hierarchical social world. When participants take their own places within it and play their part, they bring these representations into reality. Much of this occurs through the vehicle of vision, and what is seen is what the cult has shown, which is at the same time an image of the otherwise invisible world that can be imagined around the Zöhre Ana cult. The spatial arrangement reflects the worlds from which it has come to be and serves as the setting for how Zöhre Ana is to be seen.

How Zöhre Ana Is Seen

In a song on her first music cassette, Zöhre Ana punctuates a few of her ecstatic verses with a repeating line borrowed from the great Turkish Sufi poet Yunus Emre: Gel gör beni aşk neyledi (“Come, see what love has made of me”). If we accept the invitation, what do we see? What we see is not so much Zöhre Ana in her entirety as a result of her ecstatic experiences, but more so the persona that the cult has inclined to present of her, and this persona is a composite image, pieced together from the various aspects the cult finds relevant to the intended perception of her. As with the spatial arrangement in which the cult operates, the intended appearance of Zöhre Ana highlights her mystique, but also includes other facets that reflect the milieu from which the cult emerges and the cosmology and mythology that gives her charisma meaning. We can see this better in the light of the photographic tradition of the cult, as illustrated by images of her in her books, website, and social media pages—thus those images sanctioned by the cult.

One common theme in the iconography of Zöhre Ana is her association with beauty. This is usually represented in pictures in the form of flowers; she is often photographed next to or holding a flower—especially a rose—in a garden, smelling one, or seated and surrounded by potted or cut flowers (see Figure 5). Those devotees skilled in graphics are fond of superimposing floral frames around portraits of her. The association of Zöhre Ana with flowers and beauty may derive in part from the fact that she is a woman, but beauty is also a valued theme in Sufism, and the rose is its quintessential symbol.

Figure 5.

Zöhre Ana smells a rose.

Another theme we can find in her photographic portraiture is the image of Zöhre Ana as a modern woman, especially as shown in her dress and hairstyle (see Figure 6). This is in line with Alevis’ general predilections for modernity and progress, and in the case of dress contributes to their self-juxtaposition to what they consider backward Islamic dress, especially in terms of the Islamic head covering for women. We see this emphasized in the journalist İsmet Solak’s (1991, p. 8) book about her, which begins with a description of the saint:

Note that this begins with a physical description—what the observer sees—and quickly moves to how she looks at the world. In her photographic appearance, she projects modernity, especially a Turkish modernity, which is in line with Alevi aspirations. The modern dress and short hairstyle at the same time distinguish Zöhre Ana’s appearance from that of village women, with the modern here associated with urban styles. As seen in the cave, rural attire has been relegated to the museum. Zöhre Ana, in photographs, embodies a living modernity.Zöhre Ana is not covered, not veiled. She doesn’t like the veil at all. Her head is bare, her face without makeup. In short, she is a modern Turkish woman. She’s cheerful-faced and she looks at the world with love.

Figure 6.

Zöhre Ana embodies modernity.

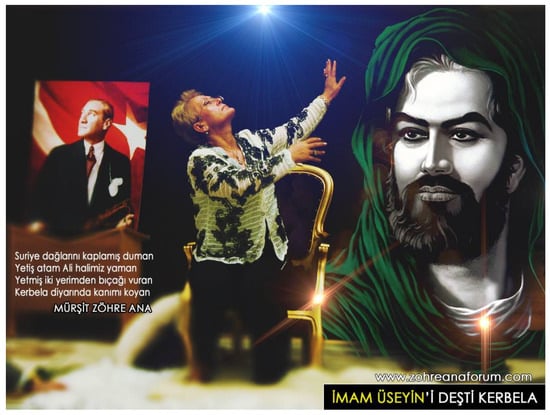

The Zöhre Ana and Alevi predilection for modernity is perhaps best encapsulated in their love of Atatürk, whom they revere as the great leader and founder of the Republic who freed the country from the bonds of the Islamic legal tradition and social order under which they feel they suffered during Ottoman times and led it toward its modern state. This progress involved advances in science and education—both of which are emphasized in Turkish modernist discourse, and by Alevis and Zöhre Ana—and also in the freedoms of women. Atatürk’s modernist reforms also, it must be noted, closed the Sufi lodges, banned many Sufi symbols, and generally disparaged the kinds of traditions Alevis and the Zöhre Ana cult still maintain, such as saint cults, shrine pilgrimage, and seeking healing from charismatic individuals not trained in modern medicine.10 But since these practices are generally allowed to continue, though frowned upon and with occasional legal pressure applied, Atatürk’s other modernist reforms far outweigh these matters in Alevis’ estimation. Atatürk is even, in the cosmology of the Zöhre Ana cult, considered an evliya, a saint. It is in the light of all of this that we can understand the frequent presence of Atatürk images appearing in the portraiture of Zöhre Ana (see Figure 7). As in her seating area in the ceremonial room, there is often a portrait of Atatürk behind her anyway, so it is natural for him to appear there in photographs of her. In addition, she will intentionally pose next to portraits or statues of Atatürk, and has made very public visits to his mausoleum in Ankara. And of course her graphics devotees have produced countless images of Atatürk superimposed on a photograph of Zöhre Ana.

Figure 7.

Zöhre Ana and Atatürk.

Also frequently superimposed on her photographs are images of Ali. The Alevis share much of their cosmology with other forms of Shi‘i Islam—the name Alevi itself derives from that of Ali—so the Zöhre Ana cult follows this inclination by featuring images of Ali, Hasan and Hüseyin, the Twelve Imams, and the Ehl-i Beyt in its iconography, and quite often these are combined with those of Zöhre Ana, linking her to them cosmologically. Ali is naturally the prime figure in this aspect; his image is on the cover of her third book, which is titled Ali Pirimdir Yolu Bizimdir (“Ali Is My Pir, His Way Is Ours”), and appears at the top of her website’s homepage, along with the motto Hz. Ali’siz Yol Yürünmez (“The Way Is Not Walked Without Ali”); the same motto also constitutes the name of her Instagram account. Along with Ali, Hüseyin—in Zöhre Ana orthography, Üseyin—is frequently portrayed, and his martyrdom in Kerbela is commemorated every year with a fast, though not coinciding with the Islamic month of Muharrem but rather always in the first half of March.

Because of the particular form Alevism has taken as it has evolved in the Republican period, it is not at all surprising or inconsistent to see Zöhre Ana in her portraiture flanked by Atatürk on one side and a Shi‘i–Islamic figure like Ali or Hüseyin on the other (see Figure 8). Such images are in fact concise summaries of the cosmology of the Zöhre Ana cult.

Figure 8.

Zöhre Ana with Atatürk and Üseyin.

Besides the saints Ali and Atatürk, Zöhre Ana’s association with other saints is also emphasized. It is they who inhabit the realm she visits, whom she contacts there, and who occasionally speak through her. She has explained the relationship thus:

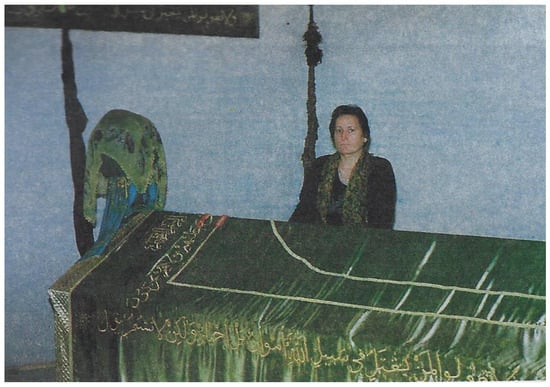

While the vague, anonymous saints she sees in the otherworld cannot be portrayed in her iconography, what we get instead are scenes of Zöhre Ana next to their this-worldly markers. Zöhre Ana would occasionally go on road trips with members of her inner circle to visit the tombs and graves of saints throughout Anatolia and would pose for a photograph next to the sarcophagus (see Figure 9). Such photographs are found in abundance in her second book, Mehtaptaki Erenler (“The Saints in the Moonlight”), so they constitute part of the canonical iconography of the cult. Such images of her presence at such sacred sites help establish in the imaginations of her followers a link, and thus an identity, between her and the saints, recalling and reinforcing the verbal accounts of her experiences with them.These saints have been drawing me into their own realm for 14 years and in this way I have frequently left behind my identity, my ego, my transitory existence, been transported into their enlightened realm and been their mouth and their tongue. I am a door opening from their real realm to humanity.(Zöhre Ana 1996, p. 5)

Figure 9.

Zöhre Ana beside the tomb of the saint Ümmü Kemal in Bolu, Turkey (Mehtaptaki Erenler, p. 270).

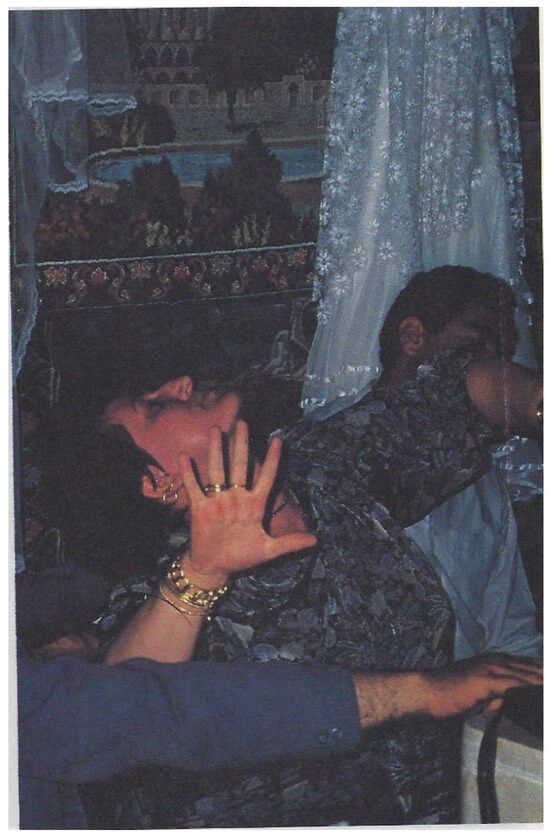

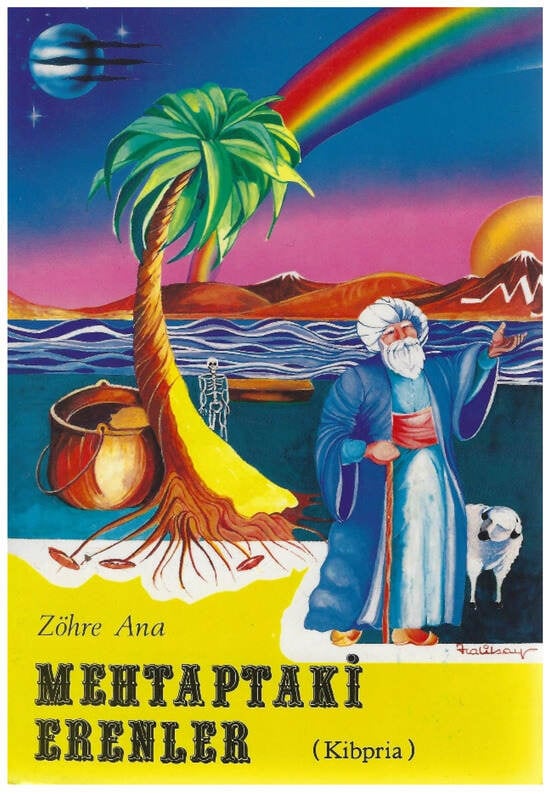

Zöhre Ana’s cosmological position among the saints is part of her overall mystique, which draws from the source of her charisma: her ecstatic experiences and the power they entail. There are a few photographs in circulation that were taken of her when she was in a state of ecstasy, and these serve as visual proof of the experiences for those who did not witness them (see Figure 10). They match up with memories of what she is reported to have seen, so that she is seen as the mystic saint in touch with the unseen. This image of her is then supported by the other mystique-inducing elements of the cult, such as the many obscure symbolic displays. Among other places, these displays appear in full force on the covers of her books and cassettes. A full explication of the complex symbolism illustrated on the cover of her second book, The Saints in the Moonlight, for instance, is well beyond the scope of this study (see Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Zöhre Ana in the ocean of ecstasy. “While Zöhre Ana was ‘reeling’ [semah dönerken], those around here were under the influence of this atmosphere. Some were moaning ‘Allah Allah,’ and some were swaying their heads to both sides and weeping.” (Cem’den Gelen Nefesler, opposite p. 122).

Figure 11.

Cover of Zöhre Ana’s second book, The Saints in the Moonlight.

Through the iconography of the cult, Zöhre Ana is seen not in her totality, which is ultimately invisible, but in assorted aspects. Different pictures highlight different aspects, and these images come together into a composite in the imaginations of observers, who thus see her not necessarily as she is, but how she is shown to be. The form of this composite intended Zöhre Ana reflects the features of the milieu in which the cult has come to be, and prepares observing devotees by increasing their receptivity to their own experiences to come.

Seeing, Believing, Experiencing

Because Zöhre Ana is at the center of a cult that has been building up for four decades and has become institutionalized, how she is seen is very much a product of how she is shown, and this is—in line with the values and expectations of the dominant tradition among her devotees—as a charismatic woman with the deepest mystical powers expressing them through an Alevi–Sufi idiom, while also projecting Turkish national modernity. This image is then magnified when she is seen placed in the setting that has been arranged for her, orienting devotees toward her spiritual greatness. And this then highlights her own visual experience—what she has seen in the other realm and has related in words so that others can virtually see it too. The visual world emerges at the nexus of scenes in the designed environment, observers with their cultural–historical expectations, and the object of their orientation and energy, and all of these come together when people, space, time, and praxis come together in a visual whole.

All of this coming together then contributes to the realization of the intended experiences of devotees. Seeing Zöhre Ana amid all that has been built up around her gives her devotees a sense of something greater and deeper than themselves, reinforcing whatever power comes from her presence. They can thus more fully experience her charisma. Many come with the aim of being healed for various afflictions, and the visual world, as it allows for the realization of a cosmology, mythology, praxis, and physical space, provides a natural environment for healing to be efficacious—even if these operate below the level of consciousness as all attention is focused on the orientational point of Zöhre Ana. And it is in this orientation toward Zöhre Ana that vision and experience converge into a single phenomenon. So often in the accounts of those who were healed by her do we hear expressed the theme of seeing-is-believing: “When I saw with my eyes and found healing, I believed,” one says (Solak 1991, p. 244); and another, “I began to cry. Not because of my suffering, but I was crying because I saw her blessed face” (Solak 1991, p. 275). Yet another (Solak 1991, p. 293) sums it up, “Anyone who hasn’t seen, hasn’t experienced this, doesn’t know, doesn’t understand, can’t explain.” Or, as one devotee, Cafer Hoca, put it to me plainly, Gel, gör, yaşa—“Come, see, experience.”

Afterimages of Ana

On 6 August 2020, as research for this study was being conducted, Zöhre Ana passed away. Those of us on the outside of her cult would say she died, but for those on the inside, she is considered to have passed on to another realm or plane, and still to exist in the cosmos. Death—that great migration to the unseen otherworld—can be conceptualized in various ways, as can its companion concepts such as the afterlife and the continuance of some form of the subject, like a soul. But when the passing subject is considered a saint or similarly extraordinary figure, the eschatological explanations often take elevated form. For her devotees, Zöhre Ana is a True One, and as they say, Gerçekler ölmez—"True Ones don’t die.” Zöhre Ana (n.d., p. 1) herself gives such an interpretation on the afterlife fates of saints: “These True Ones never die, they have only changed form”—and she notes this in a book that was published posthumously. A press release on her website announcing her passing is slightly more specific about what has become of her: Pir Zöhre Ana’mız gayba girmiştir—“Our Pir Zöhre Ana has entered absence” (or perhaps “invisibility”).11

In any case, Zöhre Ana underwent a significant transformation, and so, no doubt, will her cult, though it is not yet clear in what forms. The mythology narrating what Zöhre Ana saw and experienced has been well documented and can be read and imagined indefinitely, the cosmology it has formulated is still available to give meaning to these experiences, her iconography is still up on Instagram for all to see, and the ritual patterns remain and wait to be enacted. Her Service Building is still open every day, and visitors still come to pay their respects and to offer votive sacrifices. Since her passing came in the first year of the coronavirus pandemic, large ritual gatherings have not been allowed since that time. If they do resume, and the charismatic orientational point is no longer visible, where will visual attention be directed? What will future devotees experience who can no longer see her in the material world? In short, what will become of her visual world?

For now, devotees can continue to remember her on visits to the Service Building. They can seek a blessing on a visit to the tomb built for her in her village in Yozgat. And no doubt many will continue to see her in their dreams. But in whatever form people see her, these visions will have been shaped by the patterns that have coalesced in the cult through time.

Afterimage of Zöhre Ana. © Mark Soileau.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | It is her charisma and her special abilities that have allowed her to gain the title of ana (literally, “mother”), along with other women in this milieu who have either displayed their own special qualities or been associated with men with spiritual charisma or power or who hold institutional roles. Such men are likewise often given descent-based titles: baba (“father”) or dede (“grandfather”). |

| 2 | Zöhre Ana and her cult are described and analyzed in detail in (Dole 2012). See also (Koçer 2018). She is also mentioned in (Fliche 2013). |

| 3 | I recognize that use of the term “cult” has become problematic in English due to the negative connotations it has acquired through its frequent and often pejorative application to groups considered false or extreme, or characterized by the exploitation of followers by a charismatic leader and obstacles to voluntary exit from it. It should be clear, however, that I am not using the term in this way, but rather with the general meaning of a sociocultural system oriented around a central figure or phenomenon, especially characterized by practices of veneration of and devotion to the phenomenon. That this term is in fact used for sociocultural systems oriented around figures who are considered saints is seen in the abundant literature on “cults of saints” (e.g., Brown 1981; Wilson 1983). It is likewise used for saint cults in the Islamic context: (Taylor 1999; Meri 2002). |

| 4 | There is an abundant literature on Alevis in Turkish, and increasingly in English and other Western languages as well. For a general overview of Alevis in the modern era, see (Shankland 2003). |

| 5 | Images 1–8 are taken from Zöhre Ana’s website and social media pages, and images 9–11 are from her books; all are included here with the permission of her heirs. |

| 6 | Zöhre Ana, “Çağırayım Alim Seni”, Pir Nefesi Haktır (audiocassette). |

| 7 | Hak Muhammet Ali refers to the Alevi cosmological triad, with Hak (“the Real”) referring to God. The Ehl-i Beyt (sacred family of the Prophet) and the Twelve Imams are Shi‘i–Alevi cosmological conceptualizations. |

| 8 | https://zohreana.com/hizmet-binasi/, accessed 16 February 2022. |

| 9 | The sheepskin—post in Turkish—is a common feature of Alevi, Bektashi, and other Sufi ritual settings, marking the place where especially the authority figure sits. While the leader traditionally sits on the sheepskin on the floor, it is notable that Zöhre Ana sits in an armchair with her feet resting on the post. |

| 10 | Christopher Dole’s Healing Secular Life explores the ways Zöhre Ana and other healers in semi-urban Ankara negotiate their positions between tradition and the dominant modernist biomedical discourse. |

| 11 | https://zohreana.com/gercekler-olmez/, accessed 20 February 2022. |

References

- Brown, Peter. 1981. The Cult of Saints: Its Rise and Function in Late Christianity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dole, Christopher. 2012. Healing Secular Life: Loss and Devotion in Modern Turkey. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fliche, Benoît. 2013. Mais où sont les dede d’antan?: Les transformations de l’autorité religieuse chez des alévis d’Anatolie centrale (1919–2009). In L’autorité Religieuse et ses Limites en Terres d’Islam. Edited by Alexandre Papas, Nathalie Clayer and Benoît Fliche. Leiden: Brill, pp. 153–68. [Google Scholar]

- Koçer, Velimert. 2018. Alevi Kadın İnanç Önderliği Bağlamında ‘Yaşayan Pir Zöhre Ana’ ve Kültürel İşlevi. Uluslararası Folklor Akademi Dergisi 1: 155–68. [Google Scholar]

- Meri, Josef W. 2002. The Cult of Saints Among Muslims and Jews in Medieval Syria. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shankland, David. 2003. The Alevis in Turkey: The Emergence of a Secular Islamic Tradition. London: RoutledgeCurzon. [Google Scholar]

- Solak, İsmet. 1991. Zöhre Ana: Cemden Gelen Nefesler. İzmir. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Christopher. 1999. In the Vicinity of the Righteous: Ziyara and the Veneration of Muslim Saints in Late Medieval Egypt. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Stephen, ed. 1983. Saints and Their Cults: Studies in Religious Sociology, Folklore and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zöhre Ana. 1996. Mehtaptaki Erenler (Kibpria). Ankara. [Google Scholar]

- Zöhre Ana. n.d. Ali Pirimdir Yolu Bizimdir. Ankara.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).