Abstract

In traditional China, when confronting real-world problems, people might invite masters to perform rites of residential fengshui rectification for a healthy and prosperous life. However, no concrete cases have previously emerged to demonstrate what exorcism scriptures and ritual implements were actually employed during the adjustment process. A recently unearthed pottery basin from Linyi County, Shanxi, bearing a vermilion inscription on proper fengshui restoration, offers new insight into how Daoist masters played a practical role in maintaining everyday life. For the first time, we demonstrate what religious implements and texts were employed and the proper timing of their use. Identifying specific details of the entangled status of the Han Daoist ideology and fengshui adjustment rituals for the living broadens our observational and conceptual understanding of early Daoist involvement in family and community life.

1. Introduction

Fengshui 風水 (traditional Chinese geomancy) and Daoism 道教 have been inseparable from each other since ancient times. Daoism provides ideological support for fengshui while fengshui provides a way for the Daoist priests to serve the community life. However, on the concrete fengshui practices—rather than textual statements—for the living, there are actually no archeological examples available for one to observe and study before; while in the past, what people could observe were often traces of numerous exorcism (zhenmu 鎮墓 and jiezhu 解注) rituals associated with burial artifacts.

This study draws on religious documents and archeological artifacts unearthed recently from Han remains, including exorcistic texts, starry constellations, with the support of archeological materials of Daoist exorcism rituals in Han tombs and related works. To some extent, as we can compare, it also relates to previous studies of unearthed Chinese representations. They include Daniel P. Morgan’s work on iconographic and diagrammatic irregularities in the representation of constellations in Han tomb art (Morgan 2018). Similarly, Ho Peng Yoke has a work on Chinese mathematical astrology, published in the Needham Research Institute Series (Ho 2003), while Sun Xiaochun and Jacob Kistemaker explore starry constellations as seen in the Han (Sun and Kistemaker 1997).

Due to the inherent limitations of these excavated materials, archeological research on early Daoism has been confined to closely related issues such as funerary rituals and contemporaneous views of the afterlife. Now, scholars are ready to take on a broader investigation into the specific ways early Daoists participated in the residential and community life of their time.

But how early it might be? The particular nature of the research on the origins of Daoist religion has given rise to many differing views. Thus, the concept of “Daoism” used in this article may not fully align with its usually understood meaning (i.e., the received ideas).

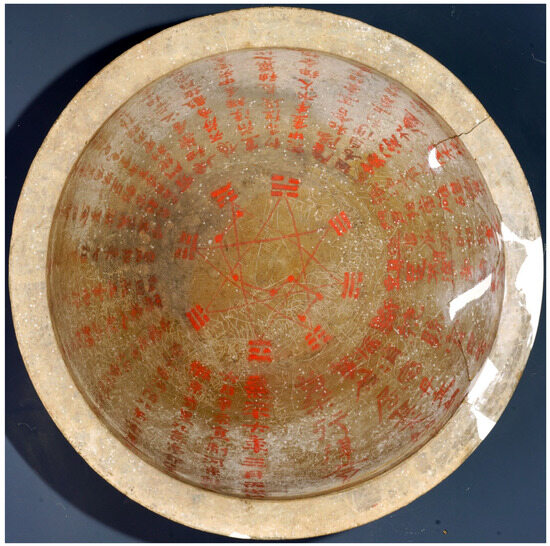

In 1983, a pottery basin was unearthed in Shangwang 上王 Village, Linyi 臨猗 County, Shanxi Province. Its inscription clearly dates it to the sixth year of the Xiping 熹平 reign period of Emperor Ling 靈帝 of the Eastern Han dynasty (177 CE). The inner base of the basin is painted in vermilion, showing the seven stars of the Northern Dipper 北斗 (the Big Dipper) and the eight trigrams of the Yijing 易經 (Book of Changes), while its inner wall has large characters, also in vermilion. As the following analysis will demonstrate, this pottery basin was used by Daoist followers in apotropaic rituals for residential rectification. The discovery of this object breaks through the limitations of previous findings and scholarship, which had only identified similar artifacts as being used in Han tomb exorcisms. It thus becomes possible to explore the techniques of residential fengshui rectification in the Han dynasty and understand the specific details of early Daoist involvement in family and community life.

2. Basic Information and Key Issues

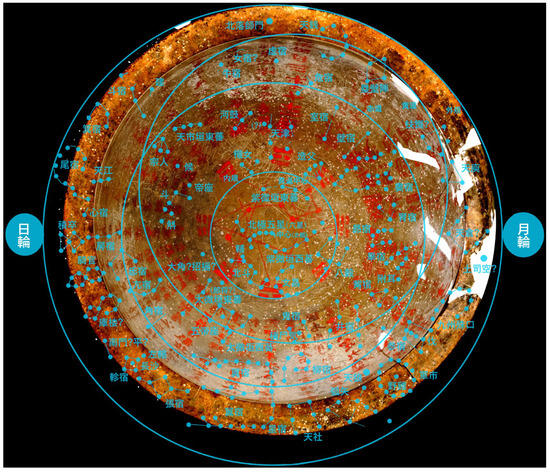

Unearthed physical remains of residential fengshui rectification practices being very rare, this pottery basin (the Linyi County Museum Collection Total Registration Number 0016) has been designated a Grade I National Cultural Relic (Zhang 2013). It is round, with a height of 16 cm, an opening diameter of 34.3 cm, a base diameter of 16.8 cm, and an inner base diameter of 14 cm. The rim is 2.5 cm wide. The exterior is plain and slightly yellowish. The inner base is painted in vermilion with diagrams showing the eight trigrams in their later-heaven arrangement of the “Shuogua zhuan” 說卦傳 (Commentary on the Trigrams) of the Yijing and the seven stars of the Northern Dipper. The inside is covered with 28 lines of vermilion script, written in columns from the base towards the rim and arranged clockwise (see Figure 1). Based on my transcription and count, the total number of characters in the vermilion text is 283. In addition, there are numerous small white specks visible all the way along the inside and up to the rim. These have not been discussed in previous research (Qiao and Han 2000) and are generally assumed to be the result of long-term burial. In the past, scholars did not pay sufficient attention to it; and previous research pursued different directions, in-depth research remains necessary.

Figure 1.

Overhead photograph of the Xiping-era earthenware gray pottery basin with the Seven Stars, Eight Trigrams, vermilion script, and small white specks unearthed in 1983 in Shangwang Village, Linyi, Shanxi. Photo by the author in May 2018 at the Linyi County Museum.

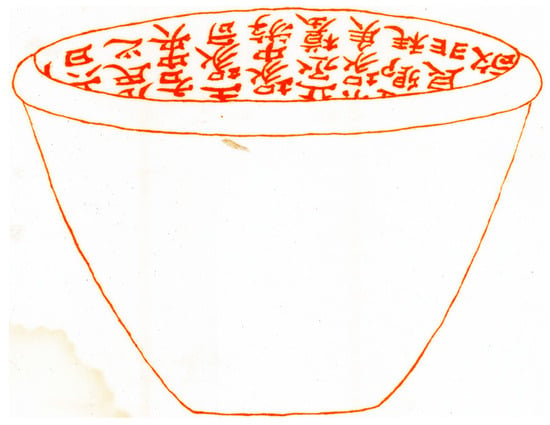

In 2018, I was fortunate to be able to examine this basin in detail. Although there are some repaired cracks, the main body is in good condition. Its form is similar to the vermilion-script pottery basin from the tomb of Zhang Shujing 張叔敬, dated to the second year of Xiping (173 CE) and discovered in Xin 忻 County, Shanxi in 1935. That basin also has a plain exterior and 23 lines of vermilion script on its inside, which can be compared with the ink drawing edition made by Ma Jianchen of Xin County in 1938 (Ma and Guo 1938, see Figure 2). The two are similar symbolic artifacts used in Daoist rituals. Regrettably, the Zhang Shujing basin was lost during the fall of Shanxi during the War of Resistance against Japan in 1937. As a result, the Linyi basin unearthed in 1983 is currently the only extant physical example of its kind.

Figure 2.

Pottery basin from the Han tomb of Zhang Shujing (173 CE) discovered in Xinzhou, Shanxi in 1935, ink drawing by Ma Jianchen (Ma and Guo 1938).

The surface of the basin’s inside is in good condition, and most of the vermilion script is clear and legible. The full text, transcribed and collated, is as follows:

It is the sixth year of the Xiping reign period (177 CE), the third month, the 26th day. May this benefit the family of Jing Chongze, the first residence at north of the west river path, located within the northern boundary of the hamlet precinct of Dongqi Village, Lü Township, Xie County, Hedong Commandery.

熹平六年三月丙戌朔廿/六日辛亥, 宜利河東解縣旅/鄉東奇里北邑亭部北界格/(恴)千西河陌北第一宅景沖則/之家.

Heaven is dark and earth is yellow, the four seasons and five phases operate smoothly, and man resides in the center. (But) a family member disturbed the earth, causing reciprocal harm and obstruction. The dominant phase was assailed and died, the minister phase was imprisoned, and thus the qi of the earth came to stray off.

天玄地黃, 四時五行, 民居/中央. 家人起土, 轉相害放(妨), 王/相囚死,土氣由(遊)行.

The residence, therefore, is now in a state of disarray, so that inauspiciousness rides over good fortune. The seven spirits are unsettled, bringing harm to the people and causing the family to decline. There is no success in agriculture and sericulture, the six domestic animals do not thrive, legal battles come frequently, and illnesses never cease. Ghost qi flourishes and the Director of Destinies is disquieted. The cooking pots are damaged while mole crickets and rats bore through the gates. Earth-punished ghosts as revenant specters appear in the central seat.

宅居逆順, /吉凶相乘, 七神不寧, 害及人民, /令家衰減,不宜田蠶, 六畜不/息, 縣官數至, 疾病不止,(鬼)氣利/益, 司命不安, 釜鳴見懐(壞), 螻䑕(鼠)/𥥯(穿)門,地刑鬼而歸精於中𡋑(坐).

Let the divine medicine of eternal virtue come to reside in the center, then above and below get in proper succession, the auspicious exorcizes the inauspicious accordingly. The talismans of heaven bear right fortunes, while the talismans of earth carry correct commands. The presiding spirit official of the residence causes all of them to return to the proper center. The declining residence prospers anew, the shortened life span is again long.

常/德神藥居之, 上下相承, 吉凶相/應. 天符有數, 地符有節, 宅/直符使歸居中央,宅衰複/利, 命短複長.

The divine medicine enters the earth and circulates within the residence. The spirit and qi and essences of [the phases]—metal, wood, water, and fire—connect smoothly with each other. Yin and yang are in harmonious union, and the five qi follow each other in good succession. The people are robust and secure, each finding their best benefit. Above is the cyan [heaven], below is the yellow [earth]: man resides in the center. The eight mansions and nine lodges as well as the nine palaces are all open and well arrayed.

神藥入地, 回行/宅中, 金木水火, 神氣精相通, /陰陽和合, 五氣相承, 人民龐(磐)/固, 各自便利, 上倉下黃, 民/居中央, 八宅九廬, 九宮(開)/張.

We now rectify all that is adverse, such as trees growing helter-skelter, doors facing each other, pestles and mortars being placed to the east, well and stove set up in a direct line with the latrine, and beds placed to cause mutual obstruction. The head and foot of the residence will no longer be slanted to one side. Valuables are applied for this rectification, (from now) the slander of legal battles is eliminated, and all illnesses are dissolved and disappeared.

治之有逆, 樹木縱橫, /門戶相當, 碓磑依東, 丼/造(灶)當廁, 𤴷(床)臥相放, 宜宅/頭足, 不得徧(偏)旁. 珎利以𣳮(治), /斷絕縣官口舌, 疾/病消忘(亡).

This vermilion text is like an arrow: the yellow stone rests beneath it. In accordance with the divine medicine and the proper execution of the statutes and ordinances!

丹文如矢, /黃石居其下, 如神/藥, 行律令.

To what extent can this pottery basin expand our understanding of Han-dynasty Daoist rituals and intervention in popular life? How can its vermilion text be interpreted accurately? How should the information contained within the text be understood? What is the purpose of the diagrams of the eight trigrams and seven stars? What are the numerous white specks? How was the exorcistic ritual implemented? These are the main questions explored in the following parts, and even, interesting fengshui treatment sample to modern people.

3. Fengshui Rectification in the Vermilion Text

The text can be divided into four parts. It begins with a preamble, introducing the auspicious time chosen for the ritual and formulated in the classical pattern of reign year, month, sexagenary sign of its first day, followed by the date of the event and its sexagenary symbol. All this is common at the period and also consistent with other Eastern Han tomb-exorcism texts. In addition, the text specifies the precise spatial coordinates of the ritual’s subject, that is, the administrative division and geographical orientation.

The second part narrates the fengshui problems that have afflicted the Jing family. Because a family member “disturbed the earth,” the harmonious cosmic order of the residence—where “heaven is dark and earth is yellow, the four seasons and five phases operate smoothly, and man resides in the center”—was compromised. As a result, the qi does not flow properly anymore, the five phases are in disarray, the qi of the earth, that means, the proper governing (yellow) power strayed off from the due central position; the disorder then makes the seven spirits (i.e., the Northern Dipper) unsettled, so the qi of earth-punished ghosts—under the yellow central Wuji earth (Zhongyang wuji tu 中央戊己土, see S. Jiang 2024, p. 193), the place for the dead—came to the control, bringing inauspiciousness and harms to the people, and therefore various kinds of misfortune haunt the family, causing the household to decline. Their gardens do not produce, their animals get sick, they suffer from numerous ailments, and are beleaguered by lawsuits.

This section of the text contains a wealth of content related to the cosmological views, numerological knowledge, and popular beliefs of the time. The opening line, about heaven and earth as well as the four seasons and five phases, clearly describes the stable cosmic order as understood at the time. The phrasing is common in many pre-Qin and Han classics, indicating the hierarchical order of heaven and earth and the operational laws of nature. The phrase “man resides in the center” appears twice in the text. It is not difficult to find that the foundation lies in Han cosmology (Csikszentmihalyi 2000, p. 54). It echoes the Taiping jing 太平經 (Scripture on Great Peace), a foundational Daoist scripture compiled in the Han, which presents systematic expositions on the position of humanity in the greater universe. For instance, the “Renbu” 壬部 (Division of the Ren Stem) section proclaims: “Man is the chief of the ten thousand things.” (M. Wang 1960, p. 710; c. f. Hendrischke 2006, p. 207). The “Sanwu youlie jue” 三五優劣訣 (Instructions on the Superiority and Inferiority of the Three and Five) states: “Heaven, earth, and man originally share the same primordial qi, which is divided into three bodies, each with its own ancestor.” (M. Wang 1960, p. 236) This emphasizes the common origin of the three powers, heaven, earth, and humanity. Based on this cosmology and related beliefs, the significance of the correct order represented by the phrase “man resides in the center” becomes clear, as does its core position in this fengshui rectification text.

Next, the description of the earth disturbance and the havoc it caused the rhythm of the five phases can be understand through related discussions by the Eastern Han thinkers Wang Chong and Wang Fu as well as through relevant statements in the Taiping jing. Disturbing the earth was considered a potentially hazardous activity in Han fengshui practice, requiring careful preventative measures. Wang Chong provides a detailed account of this in his Lunheng (Discourses Weighed in the Balance), outlining earth-disturbing taboos and related exorcistic techniques. To him, the phase in power at a certain time was “king” 王 (wang), and its following phase in the productive cycle was the “minister” 相 (xiang). In his “Nansui” 難歲 (Questions about the Year Star) chapter, he states: “When the king is assailed, it dies; when the minister is assailed, it is imprisoned; (because) in the broken positions of the king and minister, there is the qi of death and imprisonment.” (Wang and Huang 1990, p. 1024; c. f. Forke 1962, p. 407). This demonstrates the specific role of cosmological patterns such as the four seasons and five phases in guiding the daily proscriptions and prohibitions of the people, including disturbing the earth, and in divining auspicious and inauspicious outcomes.

From here, the text describes the various domestic calamities caused by the chaotic roaming of earth-qi due to the disturbance of the earth. The language is concise and easy to understand, although two features require some clarification, most importantly the seven spirits and the earth-punished ghosts as revenant specters. The seven Spirits appear various in texts found in Han tombs. For example, the vermilion text on a tomb-exorcism pottery jar from the second year of the Yuanjia 元嘉 reign (152 CE), unearthed in Luoyang, mentions that “the seven spirits determine the yin and yang of the tomb.” (Luoyang 1997). As noted in the “Tianguan shu” 天官書 (Treatise on the Celestial Offices) in the Shiji 史記 (Records of the Grand Historian), these seven are none other than the seven stars of the Northern Dipper, a major celestial constellation in charge of destiny and lifespan in Daoism (S. Jiang 2016, p. 52).

The earth-punishing ghosts and revenant specters be understood through related records in the Taiping jing. Its chapter “Sanzhe wei yijia yanghuo shuwu jue” 三者為一家陽火數五訣 (Instructions on Yang Fire Numbering Five and the Three Becoming One Family, ch. 119), states: “Yin and yang unite to give birth in the center… When things begin anew, there must not be any punishing and killing qi residing above and below. Only by placing virtuous qi and yang qi can the ten thousand things thrive and grow; if there is baleful qi within, they will be injured. Therefore, the punishing [qi] is expelled and removed.” (M. Wang 1960, pp. 676–77). The people of the Han believed that the subterranean world was inhabited by earth spirits, malevolent specters, and various kinds of ghost qi. For humans to reside above, they must first follow the “way of heaven” and center themselves on a harmonizing “life-generating qi,” also called virtuous or yang qi, that unites yin and yang. By choosing an auspicious time and using Daoist techniques to suppress the “punishing and killing qi” (death qi), they can live in peace. Prosperity and decline of a family are accordingly related to the auspiciousness or inauspiciousness, that is, vitality or decay, of their home.

The third part of the text elaborates on the “rectification” technique of the “divine medicine” and its power to resolve the various problems of decline faced by the Jing family. Its core principle of fate lies in borrowing the medicinal powers of the divine medicine to regulate heaven and earth, above and below, the auspicious and inauspicious, as well as the proper flow of the five qi. Burying the divine talisman or divine medicine “causes all to return to the proper center,” thereby restoring the prosperity of the residence and the longevity of its inhabitants. At this point, there is the proper order of yin and yang and a smooth flow of the five phases. This in turn ensures that the people are strong and secure, being free from disease as they occupy their correct position between heaven and earth: “man resides in the center.”

This section begins with the plea, “Let the divine medicine of eternal virtue come to reside in the center,” followed in the next paragraph by the statement, “The divine medicine enters the earth.” The fourth part again takes up the idea, referring to “in accordance with the divine medicine.” These three phrases reveal the ritual’s deep reliance on this element, indicating that as the basin was buried ritually, it was most likely placed upside down over a yellow stone, which represented the divine medicine. The use of a yellow stone has to do with the system of the five phases: among their five colors and associated five emperors, yellow governs the center, the seat of utmost power. Thus, we can understand what the text means when it refers to the divine medicine and appreciate the ritual process and sacred principles by which Daoist practitioners administered it.

The fourth part of the text is a short formulaic clarification, that the text in vermilion ink is like an arrow that can shoot and destroy evil and is centered on the yellow stone symbolizing the center. It emphasizes the power of the vermilion text and the yellow stone and concludes with the ritual command to execute the divine order immediately. Especially, the last phrase, “In accordance with the divine medicine and the proper execution of the statutes and ordinances!” appears widely in both other secular and religious documents of the Eastern Han period.

In summary, the vermilion writing on the inside of the Linyi pottery basin describes a remedial method applied to disasters that were caused by the Jing family’s disturbance of the earth. Its specific principle is to rectify the disruption of the sacred order caused by the chaotic roaming of earth-qi, thereby achieving the effect of expelling evil and preventing future disasters. Based on a general understanding of the intellectual and religious landscape of the time and a detailed interpretation of this ritual text, this type of ceremony can be defined as an apotropaic ritual aimed at fengshui rectification.

It should be noted here that the related magical arts (fangshu) and ritual content described on the Linyi pottery basin were also preserved and transmitted to a certain extent in later Daoist scriptures. For example, there is a surviving fragment of the early Celestial Master scripture Zhengyi fawen 正一法文 (Covenant Texts of Orthodox Unity) known as the Zhengyi fawen jing zhangguan pin 正一法文經章官品 (Chapters and Bureau Ranks of the Orthodox One Covenant Scripture) in the Daoist Canon (Daozang 28: 534–57), which is also called Qian’erbai guanzhang jing 千二百官章經 [Scripture of the Twelve Hundred Bureau Petitions]. This contains seventy-seven entries in four scrolls, of which about thirty—nearly half—are related to the narrative on this pottery basin. A careful comparison of the religious narrative on the Linyi basin from 177 CE with the contents of this scripture reveals that the text indeed preserves content from the Eastern Han.

4. The Function of the Diagrams and Specks

In addition to exhibiting this vermilion text on its inside, the Linyi basin on its base also shows several diagrams: the seven stars of the Northern Dipper in the center, surrounded by evenly spaced symbols of the eight trigrams. Between the trigrams are sixteen red lines that connect them, in essence forming an eight-pointed star. The entire image is mysterious and powerful, its religious connotations and specific functions worthy of careful study.

The Northern Dipper held a unique position in the minds of the ancient Chinese. According to the “Tianguan shu” chapter of the Shiji, it presides over all existence from above, the Seven Governors—sun, moon, and five planets—aligning themselves around it. It was, in face, considered a symbol of the Celestial Emperor, the central ruler of the universe. Rotating in the center of the celestial vault, the Dipper was like an emperor riding his chariot on a tour of the celestial realm, controlling the passage of time, monitoring the change in the seasons, arranging the division of yin and yang, facilitating the smooth operation of the five phases, and so on. Almost the entire natural order between heaven and earth was controlled by the Northern Dipper (Sima 1959, pp. 1291–92; c. f. Pankenier 2013, pp. 459–60). According to the Hanshu (Book of the Han), Wang Mang 王莽 (r. 8–23 CE) even cast a five-colored bronze “Majestic Dipper” (威斗 weidou) to show his celestial mandates everywhere, and to ward off the rebel forces; even before being killed by the Han troops, he was working with an Astrological Gentleman with a diviner’s board before him, “for the day and hour he added [the appropriate] layout [on the board. Wang] Mang had turned about his mat and sat according to [the position] of the handle to the [Heavenly] Bushel, saying, ‘Heaven begat the virtue that is in me. The Han troops—what can they do to me?’” Until being killed, he was holding in his arms the mandates portents and the bronze “Majestic Dipper” (Ban 1964, pp. 4151, 4190; Dubs 1955, pp. 372–73, 463–64).

In the basin, the handle of the Dipper is painted to point towards the Gen 艮 position of the eight trigrams. According to the “Shuogua zhuan” (Commentary on the Trigrams) of the Yijing, “Gen is the trigram of the northeast, where the ten thousand things reach their completion and begin their formation. Therefore, it is said: ‘Completion is spoken of in Gen;’”and Gen represents the mountain and the “gate of ghosts and darkness.” (Li 2022, pp. 1115, 1131; c. f. Lynn 1994, pp. 122, 124) The Dipper handle pointing to its position indicates its control and attack of the gate of ghosts, a way of suppressing ghostly qi. In addition, the Dipper as it is painted on the base of the basin indicates the location of the “Central Palace 中宮,” the residence of the Celestial Emperor, which in turn corresponds to the text’s statement that (on the earth) “man resides in the center.” This feature, using the Northern Dipper as a symbol of the center, is frequently seen in Han tombs, one example being the astronomical chart on the wall of a mid-to-late Eastern Han tomb at Qushuhao 渠樹壕 Village, Jingbian 靖邊 County, in northern Shaanxi (Duan 2017).

As for the eight trigrams surrounding the Dipper, they appear in their later-heaven arrangement, but in reverse order from the standard pattern, —following the ancient idea of “the way of Heaven turns left.” Each trigram’s position is connected to two others by red lines, indicating some kind of relationship between them. Some speculate that the red lines represent the path or sequence of the trigrams’ circulation, with the Dipper in the center serving as the hub that directs their movement. Also, the connecting lines correspond to the statement in the vermilion text: that “metal, wood, water, and fire connect smoothly with each other. Yin and yang are in harmonious union, and the five qi follow each other in good succession.”

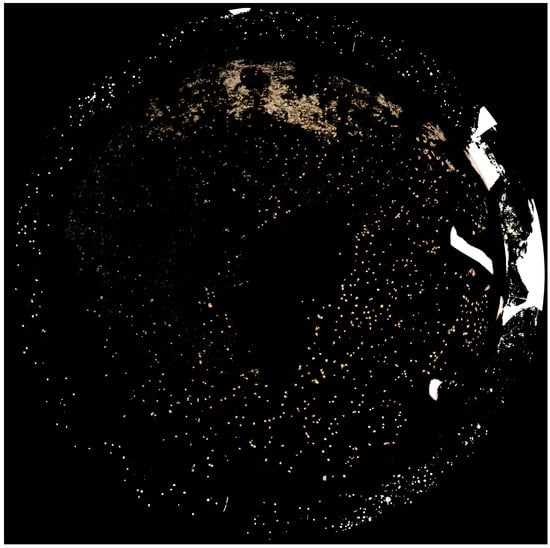

Beyond this, the entire inside and rim of the basin are covered with a large number of white specks. After taking high-resolution photographs of the basin, we applied image processing techniques to extract the white specks in more detail, gaining a fairly clear distribution map (see Figure 3). As is visible here, the specks vary in size and density in different areas, most having a diameter of less than a millimeter.

Figure 3.

Image extraction of the white specks distributed on the inner side and rim of the pottery basin (horizontally flipped).

Since the pristine exterior of the basin makes the “stains” inside easily and naturally overlooked, leading people to assume they are due to contamination from long-term burial (as told by the local authorities). Still, they are too regular and too clear to be just odd patterns of contamination. In fact, they are mostly circular, with a few resembling short dashes. Close inspection reveals that the circular ones have mostly smooth edges, not at all like stains caused by soil infiltration. Nor do they exhibit any drip-like features that would result from splashed liquids (if one were to assume they resulted from accidental liquid splatter). Rather, they appear to be deliberately applied by human hand.

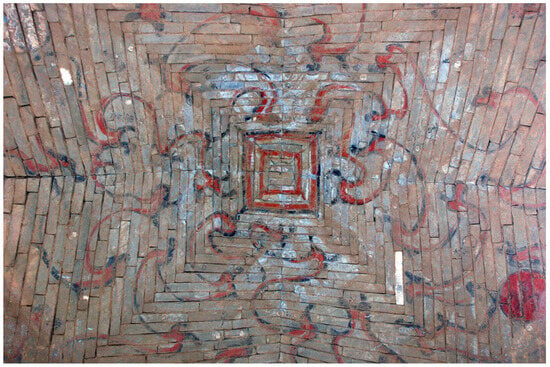

A comparative examination of related artifacts from the same period confirms that white specks of varying sizes, uneven distribution, and uniform color were indeed deliberately created by the maker to represent the stars in the sky. Through this kind of symbolic imagery, when the pottery basin is applied, it should be placed upside-down, by this way its inner side presents an ancient cosmological map of the starry sky centered on the Northern Dipper as outlined in the then-standard canopy-heaven (蓋天 gaitian) theory. That is, the scattered white specks symbolize the myriad stars filling the firmament, while the round inside and flat base of the basin perfectly simulate the (canopy) “shape” of the sky (Zhao 1938). A case from the same period—as the author has been informed and provided with photographs by local authorities—is a Han dynasty tomb (no. 82) discovered in 2004 in Wanrong 萬榮 County (see Figure 4), northern neighbor of Linyi County, featured a dome top in the frontal chamber—simulating the canopy-heaven—painted with curved clouds and white dots depicting celestial bodies on the ceiling, illustrating the Twenty-Eight Lunar Mansions with many inscriptions such as “Tai Bai” 太白 (Venus), “Mu xing” 木星 (Jupiter), and “Bi xing” 畢星 (Hyades), etc. Regrettably, the tomb has since been backfilled and remains unexcavated. Thus it is not difficult to understand that the inverted basin is just like the dome-shaped tomb with the inner painting of celestial constellations.

Figure 4.

Painting of curved clouds and white dots depicting celestial bodies on the ceiling of the Han dynasty tomb no. 82 discovered in 2004 in Wanrong County, Shanxi.

The practice of using small white dots to represent stars in tomb painting is not only widely seen in other astronomical star maps of the same period but was also transmitted in later generations, even spreading to neighboring Japan and Korea. As evident in Han and Tang tombs, such “celestial maps” depict the stars as twinkling white lights against a dark or near-black background, signifying that the tomb is located in the gloomy subterranean world. This painting method naturally continued in murals on domed ceilings after the Han. For example, the tomb of Prince Yi-de of the Tang, excavated in 1971, and that of his sister, Princess Yongtai (Li Xianhui) both have “celestial maps” on the ceilings of their rear chambers. Here “the dome is coated with a silver-gray base, and the sky is filled with stars and the Milky Way painted as white dots”; similarly, the tomb of the famous scholar Prince Zhanghuai of the Tang, excavated in 1972, has celestial maps in both its front and rear chambers, where “the celestial map in the rear chamber is more refined than the one in the front… the stars are painted as white dots.” (Pan 1989, p. 160).

In 1998, an astronomical chart was discovered on the ceiling of the Kitora Tomb in Nara, Japan, dated to around the year 700 CE. In his study, Prof. Miyajima Kazuhiko points out that the chart is a circular composition, centered on the celestial North Pole. It contains a large number of constellations and stars and, while closely resembling a real star chart, also has strong decorative aspects. The constellations here, like those on the ceilings of ancient tombs in China and Korea, are based on traditional Chinese astronomy (Miyajima 1999).

Comparing the Kitora Tomb chart with the image inside the Linyi pottery basin (see Figure 5), it becomes clear that the hundreds of solid white dots of varying sizes on the basin’s inside and rim, with their differing densities and brightness in various locations, are basically consistent with those in the Kitora star chart. According to my own count, approximately 370 white dots can be seen on the remaining part of the rim, and about 1040 on the remaining part of the inside, for a total of over 1400. While the Dunhuang Star Chart, now in the collections of the British Museum, depicts 1359 stars using three methods: open circles, black dots, and circles colored yellow. And, during the Three Kingdoms period, Chen Zhuo of the state of Wu unified the entire sky, creating a star catalog with 283 asterisms and 1464 stars, historically known as the “Chen Zhuo Standard.” 陳卓定紀 (Fang 1974, p. 289).

Figure 5.

A simulation of the Linyi pottery basin as a canopy-heaven, based on the Kitora Tomb astronomical chart. Courtesy of Prof. Miyajima Kazuhiko for providing the latest version.

This shows that the “celestial map” on the Linyi basin, although part of a symbolic object used for a religious ritual, was created with reference to contemporaneous star charts and is far from an arbitrary creation.

To sum up, the diagrams painted on the base, inside, and rim of the Linyi basin all have specific connotations and functions. The Northern Dipper in the center of the base symbolizes both the sacred Central Palace of the space where the basin is buried and, through its divine might, expels the “punishing and killing qi” that has usurped the central position, thereby re-establishing the subterranean authoritative order. Radiating outwards from the central constellation of the Dipper, the interconnected diagram of the eight trigrams provides necessary knowledge and numerological support during the fengshui rectification ritual by leveraging the laws of yin and yang and the five phases as outlined in the Yijing. The myriad stars, symbolized by the white specks enveloping the center, likewise serve to assist the main deity of the Dipper while simultaneously co-constructing a complete celestial map with the central diagram. When the basin is inverted and placed in the ground, it thus creates a unique sacred field beneath the house.

5. Who Performed the Ritual?

In the past, due to the longstanding lack of understanding regarding the Han religious history, many scholars (including the author) failed to comprehend and grasp the belief structures and connotations of Daoism of its formative period. Regardless of whether one holds affirmative or negative views, these can only be the judgments based on partial evidence. Without grasping the overall historical landscape, it is impossible to arrive at scientific conclusions consistent with historical facts. Consequently, both sides can only persist in their respective subjective judgments, making it difficult to converge toward a mutually acceptable and rational understanding.

Who applied the pottery basin? What was the religion of the Han people during the period when this pottery basin was applied?

J. J. M. de Groot pointed out that fengshui is “an essential part of the Chinese Religion in its broadest sense” (Walters 1989, p. 15); but he was unable to answer how and when fengshui and Daoism came to merge. At the same time, in the past, we were unable to present a historical landscape of the origins of Daoism as a religion. Due to longstanding gaps in understanding the religious history of the Han Dynasty, many scholars struggle to comprehend and grasp the belief structures and connotations during the formative period of Daoism. Whether holding affirmative or negative views, they often base their judgments solely on partial evidence. However, without grasping the overall historical context, it is impossible to arrive at scientific conclusions that align with historical facts. Consequently, they remain entrenched in their respective judgments, making it difficult to converge toward a mutually approximating rational understanding. Anyway, many scholars have deeply examined the unearthed materials from Han tombs and come close to the idea that the rituals were performed by Daoist masters.

In 1930, Luo Zhenyu proposed that the exorcism artifacts of the Han Dynasty were applied by Daoist priests who may have relationship with the Five Pecks of Rice sect (Luo 2003, p. 360). Chen Zhi discerned Zhang Jiao’s Yellow Turban sect through the Han pottery unearthed from Zhang Shujing’s tomb (Chen 1957). Anna Seidel and Marc Kalinowski summed up the major elements of immortal belief in Han tombs which led to organized Daoism (Seidel and Kalinowski 1982). By the study of the funerary texts applied in Han tombs, Anna Seidel stressed that “organized proto-Daoist religion gave itself in its own documents, several decades before Han historians starts to mention the ‘Rice Bandits’ 米賊 and the ‘Way of Great Peace’ 太平道… Those who still date the use of the term Dao-jiao 道教 for the Daoist religion as late as the fifth century A.D. should find here some food for thought” (Seidel 1987, p. 40. Note: except for main titles, hereafter all references of Wage-Giles spellings have been converted to pinyin). By examining the exorcism materials, Jiang Dazhi proposes that the use of talismans and the Five Stones indicates that in the Eastern Han, Daoism had replaced folk shamanism for spiritual communication (D. Jiang 1995). Liu Zhaorui takes the thought of the Scripture on Great Peace as the basis of the exorcism texts in Han tombs (Liu 1992). Wang Yucheng believes that those who applied the exorcism materials in Han era are the earliest Daoist masters (Y. Wang 1999). Barbara Hendrischke holds that these may have been part of early Daoist rituals (Hendrischke 2000, p. 158). Zhang Xunliao and Bai Bin also take the Han tomb exorcism texts as products of Celestial Master Daoism activities. (Zhang and Bai 2006, p. 287).

In recent years, religious studies of archeological materials from Han tombs show that the Han dynasty religion—previously unknown and now termed Old Daoism of the Han—which existed prior to the late second century CE (S. Jiang 2016, 2025, pp. X, 11, 53, 149, 151), underwent transformation during the late Eastern Han period by “Celestial Masters” seen in the Scripture on Great Peace (S. Jiang 2023). This transformation gave rise to the received “Daoism” represented by the name “Zhang Daoling” in the late Eastern Han era: according to the early Daoist scripture “The Commands and Admonitions for the Families of the Great Dao” (Dadaojia lingjie 大道家令戒), Zhang Daoling 張道陵 founded the Heavenly Master Daoism in the first the Han-an year (142 AD) of Emperor Shun’s reign (Daozang 18: 236; Bokenkamp 1997, p. 171). As Michel Strickmann said, it “came into social being with the Way of the Celestial Masters in the second half of the second century AD” (Strickmann 1977, p. 2), and this is approved by Terry Kleeman (Kleeman 2016, p. 3). In the past, it was generally believed and received.

With the study of the vermilion text here we can better understand that Max Kaltenmark’s idea on the dating of the Taiping jing is right: “we shall find indications which make it possible to believe that one part of our text does go back to the Han and even to a period prior to the Five Pecks of Rice or the Taiping Dao of Zhang Jue. In this part the Celestial Master is a really celestial being and not the leader of a sect. Most important of all is the fact that the element symbolizing the prince is Fire and that his color is Red. This stands in contrast to the Yellow that was the color whose advent was announced by the Yellow Turbans and probably also by the leaders of the Five Pecks of Rice (we should not forget that the Wei chose Yellow to symbolize their dynasty). This shows how, besides the similarities between the system of the TPC (i.e., Taiping jing) and the organization of the Five Pecks of Rice, one notices differences that cannot be explained if our text had first been written by the historical Celestial Masters of the Five Pecks of Rice or if it had been produced at a later date.” (Kaltenmark 1979, pp. 20–21; also see Schipper and Verellen 2004, pp. 277–80; Penny 2008, pp. 938–40).

Meanwhile, Jiang Sheng’s recent studies (S. Jiang 2016, pp. 392–98) show that the interesting depictions or sculptures of sacred birds with jars containing the elixir on their wings or holding elixir pills in their beaks found in Han tombs correspond to the Taiping Jing: according to the Taiping Jing, the birds are envoys from the gods bringing the elixir of immortality (M. Wang 1960, p. 339; Daozang 1988, 24: 429; c. f. S. Jiang 2025, p. 163). This allows the dating of the scripture (at least the chapters on the birds curing ailments and living beings by exerting vital essence) to the Eastern Han.

Therefore we may conclude that what the Taiping jing presents is a system of Daoist belief taught by the divine Celestial Master, accepted and disseminated by the late Han Daoist sects led by the celestial masters Zhang Xiu 張脩 and Zhang Jue 張角.

All these allow us to see that the maker of the pottery basin in the year 177 AD should be a new Daoist who, during the transitional period between old and new, wielded the authority of celestial masters to relieve the suffering of the people. Here the traditional art of fengshui was naturally incorporated into the Daoist practices and techniques. By this way, Daoism enriched its esoteric arts, while fengshui gained further promotion through the support of Daoist ideology.

6. Conclusions

How did Daoists, as fengshui masters, judge and regulate geomantic issues for the people? There is hardly any physical evidence and very little textual information left. Now, for the first time, with the fine earthenware basin from Linyi, we understand how early Daoists adjusted and rectified the fengshui of people’s residences.

The 283-character text on the inside of the pottery basin provides a detailed record of the essential elements of the apotropaic ritual as it was performed in 177 CE: time, location, origin, principles, specific methods, and core techniques. Through a character-by-character transcription and analysis, we have come to understand that the Han-dynasty art of fengshui for the living developed on the basis of the then-prevalent cosmological understanding of the three forces of heaven, earth, and humanity, the esoteric knowledge of the mutual generation and transformation of yin-yang and the five phases, as well as the specific belief practices derived from them, such as rectifying the earth, expelling evil, and eliminating malevolent entities.

The diagrams of the Northern Dipper and the eight trigrams on the base of the basin, along with the star map of white specks scattered on its inside and rim, form the iconographic representation of the ritual: the Dipper symbolizes the Central Palace and is in charge of rectifying the order of the place, the eight trigrams guide the circulation and mutual transformation of yin-yang and the five phases, and the star map protects the central hub of the Dipper and assists in the reconstruction of the subterranean authoritative order.

This complete ritual narrative, combining image and text, essentially reconstructs the process of the apotropaic ceremony: a Daoist practitioner writes and paints both text and images with clearly marked temporal and spatial coordinates inside the round pottery basin, then chooses an auspicious time to bury it in the house center (i.e., the proper position) of the Jing family, which has been plagued by continuous misfortunes and illnesses among both people and livestock. The process of burying was likely accompanied by corresponding oral incantations and the application of talismans. The basin had to be buried inverted, placed like a lid over a yellow stone symbolizing the “divine medicine.” In this way, the vaulted basin became a canopy-heaven, forming a sacred field complete with the Northern Dipper and a complex star map. The divine medicine resides beneath the Central Palace, the eight mansions and nine palaces are open and in motion, ultimately rectifying the chaotic earth-qi and allowing people to reclaim their proper position of the center. This, in turn, leads to the end of all diseases and misfortunes.

The ritual narrative of the Linyi pottery basin, with its contents partially mirrored in contemporaneous and later Daoist scriptures, for the first time allows us to look beyond the art of tomb exorcism seen in other Han tombs and to note the participation of Daoist practitioners in the domestic and community life of the living people through the fengshui rectification of residences. This opens our observational and cognitive horizons regarding Daoist fengshui adjustment rituals for the living, and helps us understand the specific details of early Daoist masters’ involvement in family and community life.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his gratitude to Linyi County Museum and Yuncheng Cultural Relics Workstation of Shanxi Province. Special thanks to Qi Zhang for his technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ban, Gu. 1964. Hanshu 漢書 [Book of the Han]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R. 1997. Commands and Admonitions for the Families of the Great Dao. In Early Daoist Scriptures. Translated by Stephen R. Bokenkamp. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Zhi 陳直. 1957. Han Zhang Shujing zhushu taoping yu Zhang Jiao huangjin jiao de guanxi 漢張叔敬朱書陶瓶與張角黃巾教的關係 [The Relationship Between the Pottery Jar of Zhang Shujing of the Han and Zhang Jiao’s Yellow Turban Sect]. Journal of Northwest University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 1: 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mark. 2000. Han Cosmology and Mantic Practices. In Daoism Handbook. Edited by Livia Kohn. Leiden: E.J. Brill, pp. 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Daozang 道藏. 1988. The Daoist Canon. 36 vol. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. Shanghai: Shanghai shudian. Tianjin: Tianjin guji chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Yi 段毅, Wenhai Li 李文海, Wenbao Zhang 張文寶, Jizhu Sun 孫繼祖, Xiaolei Wang 王小壘, Jinyang Zhang 張錦陽, Xiaobing Wang 王小兵, Shenglong Lei 雷升龍, Xiaoxiao Wang 王嘯嘯, Junrong Song 宋俊榮, and et al. 2017. Shaanxi Jingbian xian Yangqiaopan Qushuhuan Dong Han bihua mu fajue jianbao 陝西靖邊縣楊橋畔渠樹壕東漢壁畫墓發掘簡報 [Brief Report on the Excavation of the Eastern Han Mural Tomb at Qushuhuan, Yangqiaopan, Jingbian County, Shaanxi]. Kaogu yu wenwu [Archaeology and Cultural Relics] 1: 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dubs, Homer H. 1955. The History of the Former Han Dynasty 漢書. In Volume 3: Imperial Annals XI and XII and the Memoir of Wang Mang. Baltimore: Waverly Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Xuanling 房玄齡. 1974. Jinshu 晉書 [Book of Jin]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Forke, Alfred. 1962. Lun-Hêng, Part 2: Miscellaneous Essays of Wang Ch’ung, 2nd ed. New York: Paragon Book Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrischke, Barbara. 2000. Early Daoist Movements. In Daoism Handbook. Edited by Livia Kohn. Leiden: E.J. Brill, pp. 134–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrischke, Barbara. 2006. The Scripture on Great Peace: The Taiping jing and the Beginnings of Daoism. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Peng Yoke 何炳郁. 2003. Chinese Mathematical Astrology: Reaching Out for the Stars. London: RoutledgeCurzon. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Dazhi 江達智. 1995. You donghan shiqi de sangzang zhidu kj dao yu wu de guanxi 由東漢時期的喪葬制度看道與巫的關係 [The Relationship Between Daoism and Shamanism as Seen Through the Funeral System of the Eastern Han]. Daojiao Xue Tansuo 5: 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Sheng 姜生. 2016. Han diguo de yichan: Han gui kao 漢帝國的遺產: 漢鬼考 [Heritage of the Han Empire: Ghosts in Han China]. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Sheng 姜生. 2023. Han shihuangdi kao: Tianzi junquan yu tianshi jiaoquan zhi yuan 漢始皇帝考: 天子君權與天師教權之源 [Textual and Iconographic Evidence of the First Emperor of the Han: Imperial Power and Religious Authority]. Wen shi zhe (Journal of Literature, History, and Philosophy) 3: 57–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Sheng 姜生. 2024. Hechu shi Zhonghua: Zhonghua jiqi fuzhi chuanbu 何處是中華: 中華及其複製傳佈 [Where Is Zhonghua: Zhonghua and Its Replication and Dissemination]. Hanjiang xuekan [Journal of Han Chiang] 4: 173–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Sheng 姜生. 2025. Religion of the Han Empire: Postmortem Transformation, Immortality, and the Rise of Daoism. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenmark, Max. 1979. The Ideology of the T’ai-p’ing ching. In Facets of Taoism: Essays in Chinese Religion. Edited by Holmes H. Welch and Anna Seidel. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kleeman, Terry F. 2016. Celestial Masters: History and Ritual in Early Daoist Communities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guangdi 李光地. 2022. Zhouyi zhezhong 周易折中 [The Moderate Approach to the Book of Changes]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Zhaorui 劉昭瑞. 1992. Taiping jing yu kaogu faxian de donghan zhenmu wen 《太平經》與考古發現的東漢鎮墓文 [The Scripture on Great Peace and the Exorcistic Texts Excavated in Eastern Han Tombs]. Shijie zongjiao yanjiu [Studies in World Religions] 4: 111–19. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Zhenyu 羅振玉. 2003. Zhensong tang ji gu yiwen 貞松堂集古遺文 [The Zhensong Collection of Ancient Literature]. Beijing: Beijing Library Publishing House, vol. 2, (reprint of the 1930 lithographic edition). [Google Scholar]

- Luoyang Municipal Cultural Relics Work Team 洛陽市文物工作隊. 1997. Luoyang Litun Dong Han Yuanjia er nian mu fajue jianbao [Brief Report on the Excavation of the Eastern Han Tomb from the Second Year of the Yuanjia Reign at Litun, Luoyang]. Kaogu yu wenwu [Archaeology and Cultural Relics] 2: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, Richard John. 1994. The Classic of Changes: A New Translation of the I Ching as Interpreted by Wang Bi. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Jianchen 馬鑒臣, and Xiangsheng Guo 郭象升. 1938. Han Zhang Shujing mu biyang gaoling, Han Zhang Shujing mu zhu shu biyang wapen wen kaoshi 漢張叔敬墓辟央告令 漢張叔敬墓朱書辟央瓦盆文考釋 [Ink-drawing and Research of the Vermilion-Inscribed Basin Text from the Han Tomb of Zhang Shujing]. Vermilion and black print on Xuan paper, private print.

- Miyajima, Kazuhiko 宮島一彦. 1999. Nihon no koseizu to Higashi Ajia no tenmongaku 日本の古星図と東アジアの天文學 [Ancient Japanese Star Charts and East Asian Astronomy]. Jinbun Gakuhō [Journal of Humanistic Studies] 82: 45–99. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Daniel Patrick. 2018. On Iconographic and Diagrammatic Irregularities in the Representation of Constellations in Han (206 BCE–220 CE) Tomb Art. In Visualization of the Heavens and Their Material Cultures I. Berlin: Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Nai 潘鼐. 1989. Zhongguo hengxing guance shi 中國恒星觀測史 [A History of Stellar Observation in China]. Shanghai: Xuelin chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Pankenier, David W. 2013. Appendix: Astrology for an empire: The “Treatise on the Celestial Offices” in The Grand Scribe’s Records (c. 100 BCE). In Astrology and Cosmology in Early China: Conforming Earth to Heaven. Edited by David W. Pankenier. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Penny, Benjamin. 2008. Taiping jing. In The Routledge Encyclopedia of Taoism. Edited by Fabrizio Pregadio. London: Routledge, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Zheng’an 喬正安, and Zhenyuan Han 韓振遠. 2000. Lun Linyi zhu shu bagua qixing pen 論臨猗朱書八卦七星盆 [On the Linyi Vermilion-Inscribed Basin with Bagua and Seven Stars]. Taipei: Shanxi wenxian [Shanxi Documents], vol. 55, pp. 123–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, Kristofer, and Franciscus Verellen, eds. 2004. The Taoist Canon: A Historical Companion to the Daozang. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, Anna. 1987. Traces of Han Religion in Funerary Texts in Tombs. In Dōkyō to Shūkyō bunka 道教と宗教文化. Edited by Akitsuki Kan’ei 秋月觀暎. Tokyo: Hirakawa, pp. 21–57. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, Anna, and Marc Kalinowski. 1982. Tokens of Immortality in Han Graves: A Review of Ways to Paradise. Numen 29: 79–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Qian 司馬遷. 1959. Shiji [Records of the Grand Historian]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Strickmann, Michel. 1977. The Mao Shan Revelations: Taoism and the Aristocracy. T’oung Pao 63: 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Xiaochun 孫小淳, and Jacob Kistemaker. 1997. The Chinese Sky During the Han: Constellating Stars and Society. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, Derek, ed. 1989. Chinese Geomancy: Dr. J. J. M. De Groot’s Seminal Study of Feng Shui, Together with Detailed Commentaries by the Western World’s Leading Authority on the Subject. Shaftesbury: Element Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chong 王沖, and Hui Huang 黄暉. 1990. Lunheng jiaoshi 論衡校釋 [Annotation on the Lunheng]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Ming 王明. 1960. Taiping jing hejiao 太平經合校 [Combination and Annotation of the Scripture on Great Peace]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yucheng 王育成. 1999. Donghan tiandi shizhe lei daoren yu daojiao qiyuan 東漢天帝使者類道人與道教起源 [Dao Masters of the Kind of Celestial Envoy in the Eastern Han Dynasty and the Origin of the Daoist Religion]. Daojia wenhua yanjiu 16: 203. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xiaojian 張曉劍. 2013. Qianqiu guibao hua Linyi 千秋瑰寶話臨猗 [A Discussion of Linyi through Her Eternal Treasures]. Taiyuan: Sanjin chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xunliao, and Bin Bai. 2006. Zhongguo daojiao kaogu 中國道教考古 [Archaeology of Daoism in China]. Beijing: Xianzhuang shuju, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Shuang 趙爽. 1938. Zhoubi suanjing, fu yinyi 周髀算經 附音義 [The Arithmetical Classic of the Gnomon and the Circular Paths with Pronunciation and Explanations]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).