Abstract

The literature of the Malay world, profoundly influenced by Indian traditions, frequently adheres to the narrative patterns found in Indian literature. With the rise of Islam, literary works in the Parrot Story collection were used to propagate Islamic teachings, while subsequent adaptations and reinterpretations have led to relatively independent content. Within the framework of Sanskrit culture, the Jātaka Tales have also exerted a significant influence. Before the widespread adoption of written texts, these tales were transmitted orally and gradually evolved into written literature as local languages developed. Traveling along maritime trade routes, these tales were adapted through the use of indigenous vocabulary, reinterpretation of plots, and structural imitation in the Malay world. While grounded in Buddhist thought, these tales also reflect the social and cultural realities of the Malay world. The dissemination of Jātaka Tales across Southeast Asia underscores the broader religious and cultural diffusion patterns facilitated by maritime networks. This paper situates Jātaka literature within a broader context of religious and cultural exchange throughout the Asian maritime realm, examining the intersection of Jātaka Tales with early Malay regional narrative traditions and Indian literature. Specifically, it compares several parallel Jātaka stories in parrot stories such as the Persian version Tūtī Nāmah and its Malay translation Hikayat Bayan Budiman, demonstrating their transformation across various languages and cultures, revealing a complex process of cultural negotiation. In addition to Indic influences, the Malay literary tradition was shaped through interactions with Sinitic religious and artistic currents, fostering a syncretic environment where Hindu, Buddhist, and later, Islamic elements coexisted and merged, illuminating the dynamic interplay of Indic and Sinitic influences on the development of Malay literary traditions.

1. Introduction: The Islamization and De-Indianization of the Parrot Story Collection

The period between 1400 and 1650 was a significant era in the dissemination of Islam throughout the region known as “The Land Below the Winds” (Reid 1988, p. 1). This was marked by the conversion of Malacca to Islam in the 15th century, which subsequently led to the city’s emergence as a major port for the propagation of Islam in the Malay Peninsula and along the coasts of East Sumatra, among other areas. Islamic teachings have brought fundamental changes to the social, political, and cultural life of the Malay Archipelago. The Parrot Story collection1, a prominent example of this genre, is believed to have originated from an ancient Sanskrit folktale collection dating back to the 10th–12th century India. Subsequently, it was translated into various language versions, such as Persian (Tūtī Nāmah), Turkish, Uyghur, Urdu, Malay (Hikayat Bayan Budiman), Javanese (Hikayat Bayan Budiman), and so on. Among them, the Persian translation Tūtī Nāmah features the inclusion of an aged individual who connects the human community with the divine figure. This device adds to the narrative’s realism. During the 16th century, the period of peak Malay civilization, the literature of various countries became inextricably linked with Malay culture due to the free trade in Southeast Asia on the islands and the region’s privileged location (Reid 2000, p. 39).2 Among them, the Jātaka Tales, a collection of tales compiled in Pali by Indian Buddhists in the third century BCE, also spread to the Malay world via maritime networks.

The Persian translation Tūtī Nāmah, a seminal text of the early Islamic period, has elicited sustained interest due to its critical religious attributes and humanistic overtones (Liaw 2013, p. 279).3 While some research findings in Indonesia bear similarities to the present paper, they are mainly brief and focused on the teachings of the stories. Unfortunately, most of these studies on the meticulously Malay refined texts, Indonesian versions, and Javanese rhymes (metrum) were conducted in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. There has been a recent stagnation in the field without incorporating more recent research findings. The research situation in Malaysia has also not received much attention. Although the scholarly community has placed the collection of Malay parrot stories, Hikayat Bayan Budiman (Winstedt 1960, p. 9)4 under scrutiny from multiple micro and macro perspectives, there are still significant disparities in the narratives.

Stories may have a particular historical value.5 The rich literary traditions of Indian Buddhism provided a substantial reservoir of narratives for pre-Islamic literature. Early Sufi thought acted as a mediating force between the two cultures; through gradual adaptation, Sufi ideals emerged as a dominant belief system in society, enriching the literary landscape of this early transitional period (Braginsky 2004, p. 33).6 However, over time, these narratives became increasingly Islamic through various mechanisms, including filtering, substituting, and assimilating cultural elements. Islam strategically absorbed these stories using participation, digestion, fusion, and other methods, effectively achieving their de-Indianization. Under Islamic influence, oral traditions were reorganized, resulting in the emergence of new cultural languages. The Arabic script began to document the language of the Malay ethnic group, and traditional Arabic calligraphy and handwritten manuscripts experienced varying levels of dissemination. The narratives often employed reductionist frameworks to diminish the original religious context, characterizing it as primitive or fearsome while substituting alternative elements. The moral principles and behaviors endorsed in these stories align with religious virtues, and the artistic expression within the narratives serves to garner greater attention and support for Islam.

The profound influence of Indian Buddhist culture on the development of early Islamic literary works is evident in the numerous stories that inspired them. Islamic teachings emphasize Allah’s love and advocate for universal equality, explicitly rejecting social class distinctions among humans. The spread of Islam was facilitated by the adoption and adaptation of various narratives, which allowed for the assimilation of its ideological and cultural elements into local ethnic groups. Nevertheless, certain stories continue to reflect the enduring influence of traditional Indian ideological frameworks.

Pan (2016) conducted a comprehensive study of significant parrot story collections from around the world, clarifying the textual transmission of the Malay translation within the global context of adaptation and identifying its two primary sources. Nevertheless, as Winstedt’s research demonstrates, the processes of change and variation remain highly complex. The Malay refined edition of Hikayat Bayan Budiman (The Tale of the Clever Parrot) was produced through a meticulous collation of more than ten historical manuscripts and holds significant scholarly value. This study takes that critical edition as its primary object of analysis. In his 1920 editorial work, Winstedt, drawing on his literary expertise and the resources of the colonial archival network, filtered and omitted portions of the text deemed doubtful in origin or of inferior quality. He employed the L version as his principal base text. Through systematic comparison with the R version and the A version, he established the definitive text of this Malay classical translation (Winstedt 1985, pp. xvi). Notably, the early twentieth-century Javanese translation, derived from Winstedt’s 1920 edition, vividly reflects the multiple layers of adaptation and retransmission the text underwent during its circulation. The fragmentary translation produced by Muhammed A. Simsar (Simsar 1978) exhibits considerable narrative parallels with the critically edited Malay recension. Comparable motifs and storylines are likewise discernible in Ziyauddin Nakhshabi’s collection of tales (Braginsky 2009, pp. 59–117). Chronologically, these two works may be regarded as among the earliest extant adaptations in the corpus of New Persian literature. In sum, Hikayat Bayan Budiman, as a key textual source, provides invaluable evidence for reexamining the trajectories of cross-cultural transmission linking India, Persia, and maritime Southeast Asia.

In this study, I explore the interplay of contradictions, substitutions, and cultural alienation as a catalyst for the emergence of new folk literature, exemplified by the Hikayat Bayan Budiman in the Malay world. The dissemination of the Parrot Story Collection, with particular reference to the role of oral traditions and the impact of Islamic scholarship, shaped these narratives. This study situates the Hikayat Bayan Budiman within the context of broader sociopolitical and religious transformations, thereby highlighting its significance as a reflection of the cultural hybridity of the period. The findings of this study underscore that the collection offers an enriching and sustainable reading experience. The collection is notable for its significant theoretical value, which facilitates a deeper understanding of the complexities inherent in cultural exchange and adaptation. Among the twenty-four tales in Hikayat Bayan Budiman, two—Cerita Raja dengan Seorang Shaikh dan seekor ular serta seekor katak (The Raja Who Made Friends with a Shaikh, a Snake and a Frog) and Cerita Raja Hidustan Menurut Kata Kambing (Raja of Hindustan Who Took a Goat’s Advice)—have identifiable counterparts in the Persian versions compiled by Nakhshabi or Qadiri. Compared with the newly added narratives found elsewhere in the collection, these two represent some of the earliest layers of the source material. By examining the interstitial spaces between various cultural influences, the Hikayat Bayan Budiman emerges as a pivotal text for exploring the dynamics of identity and narrative formation in a transitional societal landscape.

2. Stories: Śibih/Sivi-Jātaka (Jātaka 499)7 and The Raja Who Made Friends with a Shaikh, a Snake and a Frog—A Tale of Exploration of Gratitude and Transformation

The Śibiḥ Jātaka is a relatively old story of the gratitude (B391) type8 that recounts the quest of King Śibiḥ for Buddhist enlightenment. According to the narrative, Indra metamorphoses into an eagle, and Viśvakarman becomes a dove, which flies to King Śibiḥ and implores him for aid. The king consents to exchange his flesh for the bird’s life. This narrative, known in the Malay world in its handwritten form as The Raja Who Made Friends with a Shaikh, a Snake and a Frog, exhibits striking parallels with the Śibiḥ Jātaka, wherein a prince selflessly cuts into his flesh to preserve the well-being of a frog. The Malay rendition recounts how the prince meticulously removes a portion of his leg’s flesh, offering it to the snake in exchange for the frog’s life.

This motif of Śibiḥ Jātaka (B391) is recurring in ancient folk tales, with different stories sharing the same core plot. Similar stories can be found in the Persian book Bakhtiar Nāma and the parrot stories of Turkish, Uyghur, Malay, and Javanese translations. Overall, the various translated versions demonstrate the richness and diversity of the story plots.

The episodes numbered 1–6 are taken from a summary of Hikayat Bayan Budiman “The Raja Who Made Friends with a Shaikh, a Snake and a Frog”:

- (1)

- The second prince, having been unsuccessful in his quest for the throne, departs from his familial home and encounters a dancing elder.

- (2)

- The prince rewards the elder with a pound of gold, whereupon the elder transforms into his attendant.

- (3)

- Upon observing a snake capturing a frog in a pond, the prince carves flesh from his leg and offers it to the snake in exchange for the frog.

- (4)

- In gratitude, both the snake and the frog transform into human beings.

- (5)

- When the king’s ring falls into the water and a poisonous snake bites the princess, the snake and the frog resolve these two issues.

- (6)

- Ultimately, the prince and the princess are united in marriage, while the three benefactors return to their original forms and bid farewell to the prince.

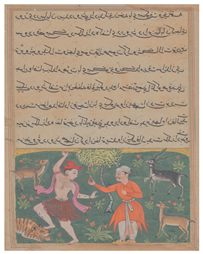

In all the translated versions, the protagonist is the second prince who fails to gain the throne. In the Malay translation, the elder brother inherits the throne, while the younger brother leaves the country, fearing for his life. In the Javanese translation, the second prince leaves home in search of inner peace. In the Uyghur translation, the prince encounters a dancing dervish in the desert and wishes to purchase happiness (Illustration 1 in Table 1).

A structural analysis of the story reveals that the prophecy propels the prince’s actions (see episode 1). The role of the older man in the middle of the road, who is likely a Sufi ascetic, is shrouded in mystery for two reasons. First, during their spiritual practice, Sufi ascetics often recite divine prophecies while in a state of people-unification (Jin 1987, p. 238).9 Second, Sufi ascetics typically live as begging monks in poverty. Consequently, the act of the prince bestowing a monetary gift upon the elderly individual assumes a more profound symbolic significance, signifying the receipt of divine grace and favor. (see episode 2).

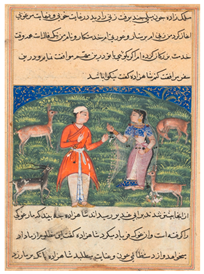

Subsequently, a transformation occurs, whereby the elderly man is metamorphosed into a young man who becomes a servant to the prince. (see episode 3) Examining the Malay translations from 1920 and 1957 reveals that the elder is portrayed as a female character. In the Turkish and Uyghur translations, the first individual encountered on the journey is depicted as a woman who frequently serves the saint and is willing to become the king’s servant (Simsar 1978, p. 125). This suggests that the source of the refined edition narrative is likely rooted in a female character (Illustration 2 in Table 1). However, in the 1985 and 2016 Malay versions, this role was modified to that of a young man, indicating a shift in the narrative’s focus.10 The gender substitutions observed across various versions introduce subjectivity into the master-servant relationship, potentially rationalizing the plot and aligning it more closely with the realities of everyday life.

Following the prince’s act of dismembering his flesh, the populace that offers recompense to him manifests successively. Subsequently, themes of justice and loyalty emerge—the use of the lack of writing technique in the narrative effectively presents certain objective elements, imbuing them with human subjective thoughts, temperaments, and feelings. the Parrot Story Collection employs analogous writing techniques, with the characters assigned to specific social functions. From the perspective of the transliteration of names, the names in various versions are very similar, all referring to the same characters, thereby suggesting that these texts share a common origin. As previously mentioned, the roles of these four individuals (Shaikh, Taksal, Khalis, Mukhalis) are not found in the earliest Jātaka version, conveying the notion that animals and humans possess equal value in terms of existence.

The concept of repayment is a recurring theme in folk narratives, and these themes exhibit a discernible reader-oriented orientation. The conjunction of Quranic almsgiving obligations and readers’ appreciation for morality is a critical factor in the widespread dissemination of the story. The repayments manifest as assistants, and their counterparts recognize their acts of repaying the prince. Within the narrative, two notable instances highlight the assistance provided by these assistants in resolving complex issues. The underlying transformation process, which is the focus of this analysis, can be interpreted through two main aspects: the interpretation of the flesh-cutting plot and the mystique of animal transformation for gratitude.

The first aspect is the interpretation of the flesh-cutting plot.

The plot of cutting flesh as an exchange for hungry animals can be found in many folk stories, such as the Hamutai Story.11 The story of King Śibiḥ Saving the Pigeon can be found in the Sutra of Wise and Foolish and the Sutra of the Garland of Birth Stories of Bodhisattvas, as well as the Mahāyāna-sūtra-alaṅkāra12 and Liudu Ji Jing13. In the story of King Śibiḥ Saving, the eagle tells King Śibiḥ that the pigeon is its rightful food and asks King Śibiḥ to return the food, so King Śibiḥ cuts off a piece of flesh from his thigh and gives it to the eagle. The Persian, Urdu, and Uyghur translations briefly describe the flesh on the body, while the Malay translation vividly describes and sets up the flesh-cutting plot.

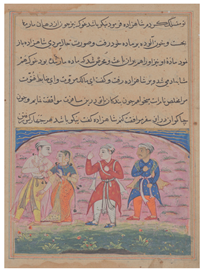

The prince in the Malay version complains to the male snake, saying that he has no conditions for exchange and only has his body left. Therefore, the prince cuts off a piece of flesh from his leg, the size of a frog, and gives it to the snake. (Illustration 3 in Table 1). This is similar to the episode from the Jātaka Tales, where King Śibiḥ weighs his flesh against that of a dove until the two weights are equal, showing the transformation of Jātaka Tales in Malay literature. In the Malay translation, the prince estimates the volume of the frog’s flesh, omitting the weighing process. All translations depict a scenario where the female snake finds the meat that the male snake brought back this time exceptionally tasty and inquires about its source. The Javanese translation is the sole exception; when the male snake reveals the origin of the meat, the female snake, upon receiving the prince’s flesh, cannot bring herself to consume it. At that moment, she is accepted as a human and follows the prince. The Javanese text mentions being accepted, suggesting the presence of an intangible, supernal energy that imbues the story with a sense of the sacred. The themes and values expressed here diverge from those articulated in the Malay translation, potentially relating to the unique Islamic doctrines based on Indian Buddhism in Java. The narrative style of the Javanese text downplays appeals for external assistance and emphasizes inner awareness and repentance. Notably, the Javanese text advocates for self-liberation and self-improvement, concepts integral to the awakening process in Southeast Asian Theravada Buddhism. Having undergone multiple revisions, the Javanese translation merges with local religious culture to present content distinct from other language versions. Additionally, the Turkish translation incorporates two supplementary vignettes: “The Gathering of the Prophets” and “Moses Cutting Flesh to Offer” as a Substitute for the Dove. Incorporating the Quranic narrative concerning the relinquishment of bodily flesh serves to underscore the religious significance of flesh-cutting within the context of the text.14

In this context, the keywords “frog’s flesh” and “give” in the Malay translation facilitate a more profound comprehension and interpretation of the flesh-cutting episode. The Malay translation reveals a size comparable to that of frog flesh and respectfully presents the act of giving to the male snake. This is in marked contrast to the more generalized descriptions of a piece of flesh or a small quantity of meat found in other translations, which often entail a tossing motion. The relationship between the prince and the male snake in the Malay translation thus transcends the realm of mere transactional exchange, embodying a religious dimension of charity and acceptance.

The Malay translation provides two clues regarding the size of the frog. First, the prince observes two animals chasing one another in the pond, noting that the frog’s size is too large, preventing the male snake from succeeding in swallowing it. Second, the dialog between the male and female snakes reveals that the male snake initially failed to capture the big-sized frog. Thus, the snake can only feed through the prince’s charity, deepening its gratitude toward the prince. The male snake’s discourse reveals both an awareness of its limitations and an appreciation for the prince’s generosity.

In Buddhist narratives, the prince cutting his flesh and weighing it symbolizes equality. Moreover, the prince’s act of giving in the Malay translation, as opposed to the term “throw” employed in other translations, does not carry a connotation of arrogance or disdain; instead, it reflects compassion and care for all living beings. Within the Islamic context, it is noteworthy that Allah is aware of the prince’s assistance to the frog. This act of charity is rooted in the highest Buddhist view of compassion. It demonstrates the creative expression of Buddhist imagination, which is rooted in a reverence for an idealized, transcendent world. The borrowing and appropriation of various Buddhist elements in Hikayat Bayan Budiman’s narrative illustrate this thought component. These elements influenced the Malay world, and the story’s integration of different cultural and religious elements indicates this influence. The Malay narrative under scrutiny in this study embodies the idea of renouncing worldly attachments and advocates for compassion to benefit all sentient beings. The notion that the unrestrained expression of life’s demands by humans and animals constitutes the foundation of the value of life is a central tenet of the Malay text. The prince’s profound inclination to sacrifice enriches the narrative, lending greater emotional depth to the story and serving as the crux of the plot.

The second aspect is the mystique of animal transformation for gratitude, which includes the following two parts: the themes of transformation and the repayment task execution within the narrative.

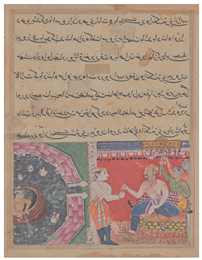

Historically, human and animal relationships have been inseparable, with the motif of metamorphosis between human and animal forms being a recurring theme in the literature. (see episode 4) This narrative is classified under the theme of transformation, wherein humans metamorphose into animals and vice versa (A1715)15, with variations in descriptions across translations. The Malay translation provides an exceptionally detailed and mystical account of the transformation process, exhibiting rich narrative qualities. Once transformed into human form, the animal’s character is vividly delineated (Illustration 4 in Table 1).

The tales of debt repayment leading to animal form have deep roots in the collective consciousness of Indian culture. The concept of reincarnation in Hinduism is frequently employed in narratives concerning transformed animals. Thematic substitution is a commonplace feature in Buddhist narratives, wherein characters are often transformed into animals, thus serving as a recurring storytelling format. The moral teachings conveyed through the selection of animals resonate with the cultural background from which the story emerges. Within the specific context of the narrative, the presence of the snake and the frog—both commonplace animals—assumes particular significance. It is worth noting that the snake is often associated with the worship of Śiva.

Islamic thought imbues these original images with new cultural meanings, providing novel interpretations of their doctrines. A fundamental aspect of this Islamic interpretation is the utilization of the motif of transformation and illusion, through which the faithful are gradually drawn in, and the characteristics of transformative animal tales disseminate the faith. The subsequent discussion will elaborate on the themes of transformation and the repayment task execution within the narrative.

First, the thematic element of transformation highlights the transformative power of religion, as evident in the various renditions of the narrative in question. A comparative examination of these versions reveals the uniformity in their depiction of the male serpent’s metamorphosis into a human entity. In Persian, Turkish, and Uyghur translations, the snake and the frog adopt human form through their strength alone, without recourse to divine intervention. In the Uyghur translation, the female snake is taken aback by the flesh brought back by the male snake; in her understanding, humans are often perceived as harming animals, which transforms her perception of humanity. The female snake invokes the creation of Adam by Allah to illustrate the reality that humans tend to kill each other, reflecting the duality of the world. In the Malay translation, the female snake chastises her husband, viewing him as a liar in contrast to the prince’s kindness. Consequently, the male snake prays to the exalted Allah, seeking to transform into a human to repay the prince’s benevolence. The Malay, and Persian translations highlight the power of prayer, emphasizing Allah’s grandeur. The narrative thus serves to underscore the potency of worship as depicted in the Quran (2: 30). Javanese missionaries, in particular, have an intense veneration for the concept of transformation, which has contributed to the favorable social conditions for the dissemination of Islam. The transformation motif is a recurring theme in the Malay translation, appearing up to nine times. The mention of the exalted Allah implies that it is preordained that the large snake or frog will become human. Significant external forces are highlighted throughout this transformation process, as praying serves as a crucial means of guiding such forces, with the ultimate goal being to extol the greatness of Allah.

The theme of transformation is a characteristic of early Malay classical literature. In terms of narrative structure, the story in Malay translation meticulously reconstructs the subjects of gratitude and the divine content within a religious framework. It can be posited that Islam has adapted existing folk narratives, thereby endowing them with a sacred nature. As a result of this adaptation process, religious doctrines gradually become the core ideas of the story, reshaping the original narrative. This transformation bears both secular and religious meanings. Throughout the transformation process, the characters exhibit meticulous behavior to avoid exposure, creating an aura of mystery. This ensures that the prince becomes the primary beneficiary, ultimately achieving the goal of repaying kindness.

Second is the mystique of the repayment mission execution process.

The mystique of the two repayments is mainly reflected in the following plot points, where someone who executes repayment undergoes transformation in a secluded and private setting. Firstly, the repayments mysteriously dive into the water to retrieve the ring. Mukalis (the frog) goes down into the river, transforms into a frog, and dives into the water to search for the ring that the king lost. (see episode 5) After successfully obtaining the ring, he transforms into human form and resurfaces to hand the ring to the prince (Illustration 5 in Table 1). From this description, it can be inferred that the underwater world provides a hidden space where animal transformations, the search for the ring, and the retrieval of the ring all occur in the water. Next, the place where the princess is treated is a secluded medical space. In the Malay translation, Khalis (the male snake) and the prince enter, where the princess rests and instructs the curtains to be lowered, and everyone else is dismissed, leaving only Khalis and the prince. Khalis instructs the princess to be wrapped in a blanket, with only her big toe exposed. Khalis then transforms into a snake. He bites the princess’s big toe, sucks out the venom three times, and spits it out three times. In the Malay translation, the setting is a domestic environment, creating a space for medical treatment within golden curtains, and includes detailed descriptions such as wrapping the princess up. In the Javanese translation, Khalis feels extremely shy when he realizes the prince is nearby after sucking the wound. The Persian and Uyghur translations also depict the sucking of the poisonous substances from the princess’s body with the mouth (Illustration 6 in Table 1). In ancient times, women were not quickly in contact with men. In the Malay translation, the princess only exposes her big toe, a more euphemistic way of writing, aiming to conduct the treatment more discreetly. This detail varies in different translations of the stories in the same Islamic region. Finally, the prince thanks the generous benefactors who have shared his hardships. In the Malay translation, the prince asks the friends who have shared his hardships not to leave.

The comparison of various translations reveals that the Malay translation is characterized by a tightly woven and logically coherent plot and the emphasis on royal lineage. In terms of character arrangement, the prince requires the assistance of a young person. He has supernatural animal helpers to aid him in solving complex tasks, ultimately enabling him to marry successfully and ascend as the new king. This observation suggests that the story collection in Malay translation exhibits discernible elements of court narrative. In contrast to other versions, the Malay version places significant emphasis on the legitimacy of royal lineage, which lays the foundation for the princess’s marriage. Other translations do not mention lineage at all. Additionally, the two trials that the prince faced can be interpreted as tests of his ability to marry.

Furthermore, the Malay translation emphasizes themes of loyalty and repayment. This detail may have influenced the Javanese translator in the Malay version, where Khalis secures a promise from the king to marry, creating a narrative in which he receives two commitments from the king. In the Javanese adaptation, the king does not honor the initial promise and only fulfills it on the second occasion, highlighting the importance of honoring one’s obligations in Malay world through the comparison. This analysis showcases the sophistication of local Malay world literary techniques, which may also be linked to the rich oral tradition, where performers have continually refined the oral text.

The local population’s acceptance of the foreign belief system, a key element in the spread of Islam, was aided by incorporating knowledge into the concept of power derived from this foreign belief system. In the previously translated narratives, the Turkish version preserves the storyline of the Buddhist tale of King Sibiḥ. A comparison of the various translations shows that the Malay translation retains the narrative structure of the Buddhist story while reinterpreting the original teachings. The circulation of cultural carriers, through which the narrative cleanses the social and ideological framework, is supported by narrators who possess mysterious supernatural abilities.

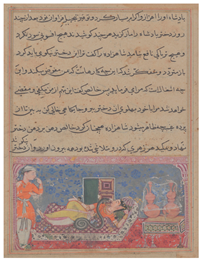

Regarding narrative strategy, the writing of this story plot depicts events at a slower pace. This is evidenced by juxtaposing a dynamic scene depicting the pursuit and act of butchering with a subsequent depiction of a more languid event. This deliberate structuring of the narrative underscores the significance of virtue, enriching the reader’s experience and offering a nuanced interpretation of the text. Religion adroitly taps into human curiosity in this context, employing metamorphosis and animal fables to disseminate its teachings. The significant scenes of the story are depicted in the meticulous paintings from the Mughal period of India during the reign of Akbar. These paintings are housed in the collection at the Cleveland Museum of Art (Table 1).

Table 1.

The significant scenes of the story are illustrated in the meticulous paintings from the Mughal India period during the reign of Akbar.

Table 1.

The significant scenes of the story are illustrated in the meticulous paintings from the Mughal India period during the reign of Akbar.

| Illustration | Caption |

|---|---|

| Illustration 1: The prince meets a carefree dancing dervish whose good fortune he purchases for his ring, from a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Eighteenth Night, c.1560. Mughal India, court of Akbar (reigned 1556–1605). Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; overall: 20.3 × 14 cm (8 × 5 1/2 in.); painting only: 6.9 × 10.5 cm (2 11/16 × 4 1/8 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.131.b16 |

| Illustration 2: Nikfal, the fortune of the prince in the form of a woman, offers to accompany him, from a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Eighteenth Night, c. 1560. Mughal India, court of Akbar (reigned 1556–1605). Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; overall: 20.3 × 14 cm (8 × 5 1/2 in.); painting only: 11.2 × 10.3 cm (4 7/16 × 4 1/16 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.132.a17 |

| Illustration 3: The prince, having deprived the snake of its natural food, a frog, feeds the snake with a piece of his own flesh, from a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Eighteenth Night, c. 1560. Mughal India, court of Akbar (reigned 1556–1605). Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; overall: 20.3 × 14 cm (8 × 5 1/2 in.); painting only: 9 × 10.1 cm (3 9/16 × 4 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.132.b18 |

| Illustration 4: The prince and Nikfal are joined by Khalis and the Mukhlis who are the grateful snake and frog in human form, from a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Eighteenth Night, c. 1560. Mughal India, court of Akbar (reigned 1556–1605). Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; overall: 20.3 × 14 cm (8 × 5 1/2 in.); painting only: 8.2 × 10 cm (3 1/4 × 3 15/16 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.134.b19 |

| Illustration 5: The prince, with the help of Mukhlis who changes into a frog, recovers the ring lost in the sea, and returns it to the king, from a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Eighteenth Night, c. 1560. Mughal India, court of Akbar (reigned 1556–1605). Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; overall: 20.3 × 14 cm (8 × 5 1/2 in.); painting only: 7.5 × 10.4 cm (2 15/16 × 4 1/8 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.135.b20 |

| Illustration 6: Khalis repays the prince for his kindness by changing into a snake and sucking the poison from the king’s daughter, from a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Eighteenth Night, c. 1560. Mughal India, court of Akbar (reigned 1556–1605). Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; overall: 20.3 × 14 cm (8 × 5 1/2 in.); painting only: 6.5 × 10.2 cm (2 9/16 × 4 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.136.a21 |

3. Stories: The Mystical Kharaputta-Jātaka (Jātaka 386)22 and Raja of Hindustan Who Took a Goat’s Advice—A Tale of Unraveling Animal Language and Symbolism

The Kharaputta Jātaka story, which includes knowledge of animal language (B216)23, is a tale of acquiring supernatural power and knowledge and exemplifies the relationship between humans and animals (Thompson 1955). This narrative is notably stable and consistent across texts from India and neighboring countries. The story can be found in Old Miscellaneous Avadāna Sūtra24. It is widely disseminated in local Javanese culture and shares a plot centered on secrecy. This article traces the origins of two classic Javanese texts, Sri Maha Raja Aridarma and Anglima. Based on their widespread dissemination within Javanese culture—having existed both as independent tales and as entries incorporated into various story collections—these independently transmitted versions belong to distinct historical stages and transmission pathways compared to the later Javanese translations derived from the Hikayat Bayan Budiman.

By situating them within a cross-temporal comparative framework, we are able to observe the evolution of these stories as they entered the Malay classical literary system during different periods. Comparative analysis reveals that, despite spatiotemporal shifts, these narratives have maintained remarkable stability in their core plot structures.

The episodes numbered 1–4 are taken from a summary of Hikayat Bayan Budiman—Raja of Hindustan who took a goat’s advice:

- (1)

- The king saw two snakes mating and killed the male snake. The female snake, having escaped, complained to her husband, the Snake King.

- (2)

- Upon hearing the false accusation from the female snake, the Snake King covertly entered the palace and killed the king, only to discover the truth later. In an act of repayment, the Snake King bestowed upon the king the ability to comprehend the language of animals.

- (3)

- On one occasion, the king expressed unrestrained mirth due to his newly acquired ability, a sentiment that provoked the queen’s ire.

- (4)

- After overhearing a conversation between two goats, the king ceased to place any credence in the queen’s utterances.

The narrative of the Jātaka Tales (386) begins with the Snake King being beaten by village children while searching for sustenance and subsequently being rescued by the king. In gratitude, the Snake King sends a snake woman to serve the king as a maidservant and imparts a spell to him. The protagonist of the tale is typically depicted as a king or hunter at the outset of the narrative. As he progresses on his journey, he encounters a variety of snakes engaged in mating behavior, which subsequently evokes a desire to destroy them. In the Malay and Javanese renditions of the tale, the protagonist encounters a pair of snakes on his return journey. In the Javanese Sri Maha Raja Aridarma and Anglima, after a period of asceticism, the protagonist comes across a snake and a dragon. (see Table 2, row 5: A Pair of Serpents)

In all iterations of the story, the protagonist assists the animals and is rewarded. The Snake King instructs the protagonist on the taboo, teaching him to acquire the language of animals. The Snake King is depicted as having a multifaceted character characterized by profound emotional depth and extraordinary abilities. His amiable relationship with humans facilitates his comprehension of animal language and thought, signifying a connection to primitive hunting culture. The ensuing discourse delves into the three levels: the Snake King, the enigmatic knowledge of animal language, and the symbolism of a pair of goats in Indian culture.

First, in Indian culture, snakes are regarded as creatures that comprehend human nature and can traverse diverse environments with ease, thereby eliciting a sense of respect from the populace. These reptiles are often seen as symbols of ancestral spirits, embodying familial guardianship, perpetual motion, and robust vitality. The protagonist’s observation of two snakes, rather than a pair, evokes a sense of discontent.

In the Malay language version, the actions of the snakes are analogous to human behavior. The depiction of the male and female snakes as esthetically dissimilar, with the female portrayed as attractive and the male as unappealing, reflects cultural perceptions of gender roles and beauty standards in Malay world. The Malay narrative implies that the union of these two snakes is considered immoral, akin to a human’s betrayal of a marital partner; thus, the king’s decision to remove the male snake is portrayed as a just act, despite the harm it causes to the female snake. (see episode 1)

The tale of Javanese Anglima exemplifies the fusion of two distinct ethnic groups and the exploration of unequal identities. In some versions, the protagonists are depicted as black snakes, mottled snakes, water snakes, and so on—representing the lower caste of the snake clan—and the king ultimately kills them. The act of slaying snakes in the aforementioned story reflects the inherent class thinking in human culture, where judging a character’s worth by appearance reveals India’s hierarchical concept.

In contrast, the Malay version only uses different types of snakes to describe them, and animal language is distinguished by color. Folk stories translated by the Indonesian Mamba, Gajo, and Badak tribes used black and white snakes to distinguish the types and told the story of a white snake being bullied by a black snake (Liaw 2013, p. 1).25 The Malay language version has incorporated elements from the Jātaka Tales, and the ethnic and class colors of the story have gradually been softened under the influence of Islamic teachings.

In the narrative of Javanese Anglima, the Snake King undertakes a journey to the kingdom of Malawabati, traversing from the underworld to the ocean’s surface. This passage is accompanied by a formidable auditory manifestation, contributing to the dreadful atmosphere. The translator’s portrayal of the Snake King and the king inhabiting distinct spatial domains concretely expresses the disparity between the two realms. The depiction of the Dragon King’s domain in the underworld is also significant, imbued with a sense of mystery.

Animal language can be classified as a rhythmic poem, as evidenced by the following passage: His tail immediately made a moving “clacking” sound, and when he left, he also made a “rustling” sound as his body rubbed against the leaves.26 The use of onomatopoeia in describing the Snake King’s actions, combined with the poem’s rhythmic cadence, enhances the vividness of the Snake King’s image and delineates the hierarchical distinction between the Snake King and humans.

In the Malay translation, the potency of the male snake is accentuated. Upon the female snake’s return to the male’s side and subsequent complaint, the male, unaware of the falsehood, becomes enraged, believing that the king disregards its venomous nature. The only way to appease the male snake, who is the Snake King on the ground, is to kill the king. It is important to note that snakes are significant in Indian culture, and the depiction of their malevolent nature profoundly affects the readers.

In Indian culture, the Sanskrit word nāga means a large snake, and such creatures are regarded as sacred. The Dragon King can metamorphose into a serpent, while the Snake King can assume the form of a diminutive serpent. Within Javanese tradition, specifically in the tales of Javanese Sri Maha Raja Aridarma and Anglima, the dragon kings undergo a dramatic transformation, gradually reducing their size to that of snakes to deceive the inhabitants of the palace. The snake metamorphoses into a decorative element in the Malay version. This transformation signifies the Dragon King’s or Snake King’s capacity for identity metamorphosis. The Malay language later adopted the terms nāga and ular to distinguish between these two entities, thereby facilitating the differentiation between these species. (see Table 2, row 8: Transformation)

During his quest for retribution, the Snake Husband or Snake King becomes aware of the truth and compensates for this by teaching the king the language of animals. (see Table 2, row 10: Imparting Knowledge) The ability to understand this language is also subject to taboos, and the taboo motif illustrates that the nature of gift bestowed by the gods upon humans ultimately remains uncertain; it may become either a disaster or a blessing. In the Jātaka, the goat recites in verse, “He who his special treasure on his wife will throw away.”27 This act encapsulates the ultimate nature of the gift.

In Indian culture, the relationship between deities and humans is intricately woven, with the responsibilities and expectations of the former toward the latter articulated through contractual agreements. The structure of these contracts delineates the boundaries between the divine and human realms. The fulfillment of these contracts is believed to bestow blessings such as bountiful harvests, protection, and longevity. Conversely, breaches of these agreements may result in adverse consequences, including illness, poverty, peril, and even death. It is widely acknowledged that accidents, prohibitions, violations, and punishments are generally considered taboo subjects. The ancient taboo motif is a recurring theme in the narrative’s plot development.

Second, the concept of comprehending animal language originates in ancient Norwegian and Greek mythology, wherein serpents or dragons instruct the protagonists in this faculty (Thompson 1955, p. 103). In Indian culture, snakes are frequently associated with serpent deities and demonic imagery, underscoring their symbolic importance. A notable instance of this can be found in the Quranic narrative of the prophet Solomon, who, according to specific translations, is taught the ability to understand all languages by the dragon king Aridarma. This may reference the story’s connection to the Quranic account of Solomon’s ability to converse with ants and comprehend the language of birds. This perspective lends significant depth to the multi-religious symbolism present in Javanese Aridarma’s narrative.

The Snake King’s gift as a reward can be classified as a mysterious gift (J1170)28, and the language teaching process is more mysterious in Jātaka. The animal language knowledge is described as “sarva rūta jnana mantaṃ” in Pali, which translates to “a spell knowing all sounds”. Here, rūta is translated as encompassing both sound and meaning, indicating that it includes the meaning of all sounds, including those made by animals. According to the original knowledge tradition in Indian culture, knowledge is divided into two types: Śruti (Vedic revelation) and Smṛti (Tradition). This Jātaka 386 is full of the mysticism of Śruti. Therefore, we can further trace the range of animal language knowledge and the understanding of animal language story types. In later translations of the Parrot story collection, the range of sound and meaning is narrowed down, and language is used instead. In ancient Javanese, it is referred to as basa, and in Malay, as Bahasa, both originating from the Sanskrit word bhāṣā. The plot of the Jātaka story shows that the sounds of snakes, male and female flies, ants, and male and female goats can be heard, highlighting the extensive range of animal language knowledge and the ability to hear even the slightest sounds. (see Table 2, row 12: Animals)

The capacity of understanding animal language is considered to be a sacred gift. In the Malay translation, the king informs the Snake King that this is a gift he can bestow and receive, signifying that the recipient must possess the necessary qualifications to accept this sacred gift. The king’s recitation of this language is said to result in the acquisition of related knowledge, indicating the king’s aptitude for receiving knowledge and its sanctified character, which surpasses human capabilities and exemplifies a demonstration of the miraculous. The mystical auditory phenomenon (cittabyañjanā) involves the articulation of abstract consonants or syllables imbued with focus and depth, seemingly conveying sacred wisdom. In Java, the concept of animal language is a reinterpretation of Listening to Goats’s Talk and has been adapted to align with the local cultural connotations of Java.

The basis of this gift can be traced back to the external knowledge referred to by Buddhists. The bestowal of gifts in Javanese Anglima is considered sorcery, locally referred to as black magic, which necessitates a purification ritual to eradicate the prohibited consequences. The narrative in Javanese Anglima recounts the calamities associated with the forbidden knowledge of understanding animal language.

Following the advent of Islam in the Malay world, spells aligning with Islamic doctrine were retained. When recited, they were always invoked in the name of Allah, concluding with praises directed to Allah. Sorcery incantations that were inconsistent with Islamic teachings were discarded. These recitations have become a unique form of incantatory literature (mantra) in the archipelago, showcasing the distinct sacred wisdom (marifat) of the local culture.

Early Javanese and Malay folktales gradually transitioned to monotheistic forms while retaining narratives about teaching animal language for educational and doctrinal purposes. This phenomenon underscores the religious character of these early local folktales, which derive from Indian cultural roots while exhibiting a progressive narrowing of scope regarding sound and meaning, reflecting the selective absorption and creative transformation of Indian culture by the Malay world, demonstrating the process of intercultural interaction.

Within Indian culture, characterized by a deep respect for all life forms due to its animistic beliefs and long-standing religious traditions, sentience is attributed to a wide range of creatures, from elephants to ants. The Manusmṛti, a text dating back to the 2nd century BCE, outlines specific penalties for harming these creatures.29 This suggests a certain degree of harmony between the human and animal domains, and the narrative, excluding the animal theme, fulfills the human imagination of the animal world. The theme of animal stories is longstanding, wherein natural forces are personified and assigned social attributes. In Indian literature, animal metaphors and human actions coincide. A notable example of this can be seen in the Jātaka Tales, which utilize anthropomorphic descriptions of ants, including their verbal expressions, physical movements, and audible cries (Huang 2014, pp. 424–54).30 The Jātaka Tales emphasize human action and symbolic meaning, highlighting the human experience of imagining or learning from animal behavior. Stories originating from neighboring countries and being orally translated maintain humorous and playful elements to facilitate learning.

Third, the symbolism of a pair of goats in the Jātaka Tales is widely considered to embody the profound essence of Buddhist teachings. (see Table 2, row 15: Two Goats/Deities) The narrative in the Jātaka Tales frequently features a pair of goats in the context of the king’s instruction to his wife. (see episode 4) In the tale known as Donkey’s Son, the male goats are said to represent the Bodhisattva Śakra, while the female goats are identified as the daughter of the deity Asuras, Sujā. In such narrative, Śakra utters an incantation that renders their movements perceptible only to the king, excluding all others. He then pretends to be intimate with Sujā, the female goats, prompting the Sindh horse to make imprudent remarks about goats, implying a lack of intelligence and shame. The symbolism of goats in this context is noteworthy, as they are often associated with virility and shamelessness. This association is further reinforced by the belief that the Bodhisattva Śakra is incarnated as a goat, suggesting a symbolic transformation of identity and role. The Jātaka Tales place significant emphasis on the power of the Bodhisattva.

Following two cycles of divination, the queen is ultimately struck, acquiring an understanding of the sanctity of life and relinquishing her inquiries regarding disseminating knowledge. In the context of the Aryans in India, the concept of divine intervention in human affairs, accompanied by the protective role of deities over their subjects, is a prominent belief.31 Consequently, the god perceives King Sjanak as foolish and metamorphoses into a divine ram. Simultaneously, folk tales also feature supernatural powers that transform into goats (D134.4).32

The primary structure of the Buddhist scripture employs a narrative approach, incorporating stories set in this life and those corresponding to past and present lives, with karma serving as the underlying principle that governs events. The Buddhist scripture emphasizes the enhancement of moral character and highlights the power and wit of the Bodhisattva Śakra, who transforms into a goats to offer counsel and devise plans. The narrative effectively conveys the symbolism of redemption, a motif frequently employed in translated stories. In the Jātaka Tale under scrutiny, the eponymous goats, Sujā, bases her request on her pregnancy. This notion of pregnancy, akin to certain other narrative variations, is a salient theme in the text.

Similarly, the Malay translation’s conclusion portrays a pair of conventional goats as the pivotal protagonists of the narrative. However, given that this narrative is entitled The Raja of Hindustan Who Took a Goat’s Advice, it is evident that it draws upon Indian cultural elements. Upon comparison, the intention of the divine is not explicitly stated. When translators retold the story, they employed metaphors rather than the narrative precepts found in the Buddhist scripture. At critical moments in the story, goats are imbued with even more significant symbolism. The ram’s speech is more neutral, indicating that a woman’s request can be either medicine or poison.

Finally, in the description of the fire ritual in Javanese Anglima, a pair of goats also appears. The ewe claims to be pregnant and requests that the ram proceed to the ashes to retrieve green leaves. The ram acquiesces to the ewe’s request, stating that he would not submit to his wife’s authority as the king had done. The king, having had a sudden realization, departs from the altar. The property bestowed upon the sage by the king serves as the reward for religious purity (prāyaścittānira). Subsequently, the wife and the ewe are thrown into the fire and burned to death.

The two goats referenced in Javanese Anglima are said to be reincarnations of the gods who came to guide the king who had erred. The goats in this narrative are regarded as divine, akin to the Donkey Son in the Jātaka. In the original fable, the speaking domestic poultry, such as the rooster, is predominantly male. During the agricultural era, the relationship between domestic poultry and humans was more amicable, and it was easier to embody and preach after becoming incarnate (Thompson 1955). Additionally, within the folklore of the Indonesian Gayo and Badak tribes, there exist accounts of a pair of goats, a chicken, and a hunting dog (Liaw 2013, p. 1). Consequently, within the context of Islamic translation, the narrative encompasses a range of versions, extending beyond the aforementioned dialog between the two goats, highlighting the diversity of the story text. This can be seen as an animal metaphor (A670)33 story, with simple, exciting statements demonstrating the shallow proselytizing effect.

A comparison between the ancient Jātaka, Javanese tales and the Malay The Raja of Hindustan Who Took a Goat’s Advice reveals that the core plot remains largely unchanged. (Table 2) The literary tradition of the Malay world is characterized by a relatively stable plot with minimal Indianized story elements. This stability may be attributed to the vivid and humorous nature of animal stories, which have been popular for centuries. The analysis of two distinct periods of dissemination and transmission reveals that the story originated from the Indian cultural context. While the fundamental narrative remains constant, the plot undergoes modifications in various sections. The story has gained significant popularity in the Indonesian archipelago, with numerous instances of borrowed plot elements across different variant texts.

For instance, in the ancient Javanese folk story Maha Basuparicāra, the king gains knowledge of the animal language (Zurbuchen 1976, pp. 42–43). Most handwritten copies referenced are from the 19th century or earlier, and some original manuscripts are partially damaged. In circumstances where the copyists had no alternative, they were compelled to recreate and form new parallel texts, which constitutes one of the factors that led to the formation of new texts. The significant scenes of the story are depicted in the meticulous paintings from the Mughal period of India during the reign of the Mughal Court of Akbar (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of plot elements between Kharaputta Jātaka and the Story of the Hindustani King Who Listens to Goats: similar story types and related content34.

Table 2.

Comparison of plot elements between Kharaputta Jātaka and the Story of the Hindustani King Who Listens to Goats: similar story types and related content34.

| Languages | Pali35 | Javanese36 | Javanese37 | Malay38 | Javanese39 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Story | Kharaputta Jātaka | Sri Maha Raja Aridarma | Anglima | Raja of Hindustan Who Took a Goat’s Advice | A Person Who Understands Animal Language |

| Setting Characters | King of Benares (Bārāṇasi), Serpent King; Sahalsah | Sri Maha Raja Aridarma, Serpent King | Malawapati Kingdom, Serpent King | Hindustani, Serpent King | Indian Kingdom (Ngindhi), Serpent King |

| Origin | The king, while strolling in the garden, saves the Serpent (nāga) King and grants him a serpent girl. | Returns from hunting | Returns from ascetic practices | Returns from hunting | Returns from hunting |

| A Pair of Serpents | The serpent girl and water serpent engage in transgressive behavior. | A dragon and a black snake copulate. | A dragon and a common snake copulate. | The female snake possesses esthetic appeal, while the male serpent is notably unattractive. | The female serpent displays vibrant coloration, entwined with a male serpent. |

| Actions of the King | Injures the serpent girl with a bamboo board. | Wounds the female serpent with a knife. | Accidentally injures the female serpent with an arrow. | Unsheathes a sword and beheads the male serpent. | Unsheathes a dagger and kills both serpents. |

| Actions of the Female Snake | Complains to the king. | Informs her father, who compels the king to take her as his wife, allowing her to escape. | Lodges a complaint with her husband. | Informs her partner. | Lodges a complaint with a partner. |

| Transformation | Dispatches four serpents (nāga youth) to kill the king using their nostrils. | Transforms into an ascetic and enters the palace as a small snake. | Transforms into a small snake. | Hides within a flower and transforms into an ornament. | Transforms into a small snake within the palace. |

| Hiding Place | Enter Senaka’s bed-chamber | Under the bed. | (Not explicitly stated). | Under the bed. | (Not explicitly stated). |

| Imparting Knowledge | Teaches the king a mantra enabling comprehension of all sounds and meanings. | Instructs on animal language proficiency. | Imparts the skill of understanding the languages of all creatures, as taught by Solomon. | A servant presents the capability of understanding all animal languages to the king. | Respectfully invites the recipient to learn about the significance of understanding animals. |

| Secrecy | Affirmative | ||||

| Animals (Insects) | Ants, male fly, female fly | Cockroaches | Cockroaches | Cockroaches | Cockroaches |

| Animal Dialog | (1) The ant remarks that the honey pot is cracked. (2) The female fly states that the perfume powder has fallen, leading her to rest on the king’s back for a while. (3) The ant cries that a wagon of rice has broken. | The male cockroach feels envious of the intimacy shared between the king and queen, as his wife does not treat him similarly. | Cockroach dialog | If the queen retains a trace of perfume, she could apply it to the king. | Aromatic fragrances of lemongrass and nine ripe fruits waft, creating an atmosphere for massage with oil. |

| Queen’s Thoughts | Believes the king is mocking her. | Believes the king is mocking her. | Develops jealousy, thinking her husband loves the dragon king Naga Pertala more. | The king incessantly laughs at the queen’s shortcomings. | Feels discomfort, believing her husband lacks courage. |

| Two Goats/Deities | Incarnations of Sakka, king of gods, and Sujā, daughter of the Asuras. They feign copulation to attract attention./Yes | Female goats Bengal/Bangali and male goats Wiwita seek tender green leaves./Not explicitly stated. | The female goats and male goats named Manggali are incarnations of deities; the female goats leaps into the fire./Yes | The female goats, nearing labor, considers consuming grass./Not explicitly stated. | Even in challenging circumstances, the female goats desires the male goats to fetch grass./Not explicitly stated. |

| Location of Grass | (Not explicitly stated.) | Adjacent to the cremation site. | (Not explicitly stated.) | Inside the pool. | Next to the palace. |

| Dialog with the Male Goats | The male goats engage in conversation with a trustworthy Sindh horse, initially asserting that goats are foolish and shameless, to which the goat counters that the horse is also foolish, and the owner, Senaka, is even more so. | The male goats remarked to the female goats that the palace is guarded by soldiers wielding weapons. This declaration caused the female goats considerable displeasure, as she interpreted it as a sign of her husband’s unfaithfulness. | (Not explicitly stated.) | The male goats articulated to the female goats that his hesitation was not a reflection of unwillingness; rather, it stemmed from the fact that the water was exceedingly deep, which put him at risk of drowning. | The male goats mentioned that he could reach the thick grass growing near the palace of Baligambhu to collect some for her. |

| Outcome of the Queen | She was beaten and not mentioned again. | The female goats and the queen committed self-immolation. | They chose to self-immolate. | Remained silent. | Experienced a multitude of emotions. |

Table 3.

The significant scenes of the story are illustrated in the meticulous paintings from the Mughal India period during the reign of Akbar.

Table 3.

The significant scenes of the story are illustrated in the meticulous paintings from the Mughal India period during the reign of Akbar.

| Illustration | Caption |

|---|---|

| Illustration 7: The snake, hidden in a basket of flowers, reveals himself to the Raja who has just sent away his wife, from a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot): Forty-third Night, c. 1560. Mughal India, court of Akbar (reigned 1556–1605). Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; overall: 20.3 × 14 cm (8 × 5 1/2 in.); painting only: 10.6 × 10.8 cm (4 3/16 × 4 1/4 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A. Dean Perry 1962.279.278.b40 |

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study elucidates the complex processes of cultural transmission and transformation within Malay literary traditions, revealing a multilayered interplay of Indian, Buddhist, and Islamic influences. The analysis demonstrates that the Hikayat Bayan Budiman represents not merely a literary artifact but also a significant site of cultural negotiation, wherein de-Indianization and Islamization were strategically employed to facilitate religious and cultural transition. The findings highlight three critical dimensions of this literary evolution: first, the adaptive mechanisms of narrative transformation through filtering, substitution, and the assimilation of Islamic elements; second, the enduring presence of Indian Buddhist cultural markers despite extensive Islamization; and third, the emergence of distinctive folk literature through dynamic intercultural interaction.

The theoretical implications of this study extend beyond literary analysis, offering valuable insights into the mechanisms of cultural adaptation and religious transformation in Southeast Asia. The case of the Jātaka stories within Malay literature exemplifies how literary texts function simultaneously as vehicles for ideological transmission and as sites of cultural preservation and innovation. This dual function underscores the Hikayat Bayan Budiman’s enduring significance as both a historical document and a living tradition, providing a sustainable framework for understanding the complexities of cultural exchange in the Malay world.

Furthermore, the materials compiled by Winstedt indicate that the provenance of the Malay recension remains highly complex (Winstedt 1958, pp. 87–110). The scribe may have translated directly from a Persian version, suggesting that the compiler of Hikayat Bayan Budiman was not necessarily aware that specific narrative components were originally of Indian cultural origin. Another plausible explanation is that the Persian version itself had already preserved these Indian elements, which were subsequently transmitted to the Malay Archipelago and retained without significant alteration, as they did not conflict with the prevailing religious doctrines of the time. This phenomenon is closely related to the widespread influence of Sufism in the Malay world—Sufi thought, with its inherent inclusiveness and rich metaphorical tradition, readily accommodated the moral allegories embedded in foreign narratives. Therefore, it may be concluded that Hikayat Bayan Budiman preserves Jātaka-type narrative elements derived from Persian tradition, exemplifying both the textual continuity and adaptability that characterize cross-cultural literary transmission.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research Base for Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education, China, grant number 22JJD750002. The research project is entitled “Interactions between Eastern Literature and Civilization: A Comparative Study of Multilingual Ancient Eastern Literary Illustrated Books 東方文學與文明互鑒:多語種古代東方文學插圖本比較研究 And The APC was funded by Guangxi University for Nationalities.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks go to the five anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and many constructive suggestions, which have greatly improved this article. I would also like to express my gratitude to the editors of Religions for their attentive guidance and support. I owe a particular debt to Professor Andrea Acri (PSL University, Paris) for his invaluable encouragement to pursue the publication of this work. Any remaining errors or shortcomings are, of course, entirely my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

CBETA Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association, https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh accessed on 30 June 2025.

Notes

| 1 | Parrot Story collection: The Parrot Story corpus originates from the Śukasaptati and TūtīNāmah, and the various versions that emerged throughout its transmission collectively constitute a distinctive narrative cluster. From these versions in different languages, we can trace the stable core narrative threads that persisted throughout the process of transmission, while also examining the specific details where variations and transformations occurred. |

| 2 | When Anthony Reed talks about the maritime trade in Southeast Asia, he mentions that: “The 16th-century merchant of Hikayat Bayan Budiman did business, leaving a parrot at home to protect his wife’s virginity. Johns explains that this is a product of Malacca’s new individualism and business spirit, but it is not conclusive”. |

| 3 | “This framed narrative arrived in the Malay world with the spread of Islam and was rendered into the Malay as well as the Buginese and Makasarese languages”. |

| 4 | “A story of the ingenuity of the bird we call a parroquet. The Malay version has been variously entitled the Ht.Bayan Budiman, Ht. Khojah Maimum, Ht. Khojah Mubarak and Cherita Taifah”. |

| 5 | (Needham 1960, pp. 232–62). |

| 6 | “This was all the more important as the exponents of Sufism (which, contrary to Hinduism and Buddhism could be propagated by numerous merchants”. |

| 7 | “How a prince gave his own eyes as a gift, and his reward.” See (Cowell et al. 1901, Vol. 4, pp. 250–56). |

| 8 | “Animal grateful for food”. (Thompson 1955, Vol. 1, p. 431). |

| 9 | “在蘇菲派合一狀態時, 會有真主潛入的意識, 言談和見地都是屬於真主的。” (Within the Sufi experience of mystical union (fanāʾ), there emerges an awareness of divine indwelling, wherein speech and perception are regarded as emanating from God rather than from the individual self). |

| 10 | “Maka dengan takdir Allah taala seketika lagi dilihat di belakangnya, maka adalah seorang orang muda mengikut dia.” (Winstedt 1985, p. 58). The 1920 and 1957 versions both depict the character as a woman (perempuan), while the 1985 and 2016 versions present a young person (seorang orang muda). In both the Turkish translation by Simsar and the Uyghur version, the servant expresses willingness to serve as the king’s maid, indicating a possibly consistent origin for the story. |

| 11 | In 2006, Kong Julan conducted a comparative analysis of the flesh-cutting episode in the Urdu translation, asserting that it exhibits parallels with the Buddhist narrative of King Śibiḥ saving the dove, wherein the prince also sacrifices flesh to save an eagle. She contends that the thematic underpinnings of these two narratives differ; the former embodies Buddhist principles, emphasizing the notion that good deeds are rewarded. (Kong 2006, p. 58). |

| 12 | 《大智度論》敦煌254窟屍毗王本生和摩訶薩埵本生, The Treatise on the Great Wisdom, Dunhuang Cave 254, comprises King Śibiḥ’s and Mahāsattva’s narratives. |

| 13 | 《六度集經》卷1: 「「昔者菩薩為大國王, 號薩達, 布施眾生恣其所索, 愍濟厄難常有悲愴。天帝釋覩王慈惠德被十方, 天神鬼龍僉然而曰: 『天帝尊位初無常人, 戒具行高慈惠福隆, 命盡神遷則為天帝。』懼奪己位, 欲往試之, 以照真偽。帝命邊王曰: 『今彼人王, 慈潤霶霈福德巍巍, 恐于志求奪吾帝位。爾化為鴿, 疾之王所, 佯恐怖, 求哀彼王。 彼王仁惠, 必受爾歸; 吾當尋後從王索爾。王終不還, 必當市肉, 以當其處。吾詭不止, 王意清真, 許終不違, 會自割身肉以當其重也。若其秤肉隨而自重, 肉盡身痛其必悔矣。意有悔者, 所志不成。』「釋即化為鷹, 邊王化為鴿。鴿疾飛趣于王足下, 恐怖而云: 『大王哀我! 吾命窮矣! 』王曰: 『莫恐莫恐! 吾今活汝。』鷹尋後至, 向王說曰: 『吾鴿爾來, 鴿是吾食, 願王相還。』王曰: 『鴿來以命相歸, 已受其歸, 吾言守信, 終始無違。爾苟得肉, 吾自足爾, 令重百倍。』鷹曰: 『 吾唯欲鴿, 不用餘肉, 希王當相惠。而奪吾食乎?』王曰: 『 已受彼歸, 信重天地, 何心違之乎?當以何物令汝置鴿歡喜去矣?』鷹曰: 『若王慈惠必濟眾生者, 割王肌肉令與鴿等, 吾欣而受之。』王曰: 『大善! 』即自割髀肉秤之令與鴿重等; 鴿踰自重, 自割如斯, 身肉都盡未與重等, 身瘡之痛其為無量。王以慈忍心願鴿活, 又命近臣曰: 『爾疾殺我, 秤髓令與鴿重等。吾奉諸佛, 受正真之重戒, 濟眾生之危厄, 雖有眾邪之惱, 猶若微風, 焉能動 太山乎?』「鷹照王懷守道不移, 慈惠難齊, 各復本身。帝釋、邊王稽首于地曰: 『大王! 欲何志尚, 惱苦若茲?』人王曰: 『吾不志天帝釋及飛行皇帝之位, 吾覩眾生沒于盲冥, 不覩三尊、不聞佛教, 恣心于凶禍之行, 投身于無擇之獄。覩斯愚惑, 為之惻愴。誓願求佛, 拔濟眾生之困厄, 令得泥洹。』天帝驚曰: 『愚謂大王欲奪吾位, 故相擾耳。將何勅誨?』王曰: 『使吾身瘡愈復如舊, 令吾志尚布施濟眾行高踰今。』天帝即使天醫神藥, 傳身瘡愈、色力踰前, 身瘡斯須 [29]豁然都愈。釋却稽首, 遶王三匝歡喜而去。自是之後, 布施踰前。菩薩慈惠度無極行布施如是。」」(CBETA 2025.R1, T03, no. 152, p. 1b12-c25). |

| 14 | In the literary work entitled Moses Cutting Flesh to Offer as a Substitute for the Dove, the male snake recounts the narrative of the dove being attacked by an eagle. This narrative parallels the flesh-cutting episode depicted in the tale of King Śibi saving the dove. In this story, the dove, seeking refuge, flies to Moses and expresses a desire to hide beneath his robe. The narrative features a substitution of the tested king with the renowned ancient prophet Moses, while the eagle and the dove are represented by Michael and Gabriel, respectively. The Turkish narrative of Moses Cutting Flesh to Offer as a Substitute for the Dove exhibits a striking resemblance to the Jātaka Tale of King Śibiḥ Saving the Dove, providing a deeper framework for contemplating the flesh-cutting incident. Following the flesh-cutting episode, the male snake returns home and recounts the same story again. This dual narrative reinforces the religious messages and experiences, showcasing powerful narrative examples. The Uyghur translation also preserves the episode of The Gathering of the Prophets. See (Simsar 1978, pp. 126–27). |

| 15 | “Animals from transformed man.” (Thompson 1955, Vol. 1, p. 250). |

| 16 | For online photographic resources, see https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1962.279.131.b (accessed on 15 June 2025). |

| 17 | For online photographic resources, see https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1962.279.132.a (accessed on 15 June 2025). |

| 18 | For online photographic resources, see https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1962.279.132.b (accessed on 15 June 2025). |

| 19 | For online photographic resources, see https:https://www.clevelandart.org/print/art/1962.279.134.b (accessed on 15 June 2025). |

| 20 | For online photographic resources, see https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1962.279.135.b (accessed on 15 June 2025). |

| 21 | For online photographic resources, see https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1962.279.136.a (accessed on 15 June 2025). |

| 22 | “A king gets a charm from a nāga by which he understands the sounds of all animals. His wife tries to get the charm from him, but is foiled through Sakka’s advice.” (Francis and Thomas 1916, pp. 259–62). |

| 23 | “Knowledge of animal languages. Person understands them.” (Thompson 1955, Vol. 1, p. 400). |

| 24 | 《舊雜譬喻經》卷1: 「昔龍王女出遊, 為牧牛者所縛捶, 國王出行界, 見女便解之便使去。龍王問女: 「何因啼泣?」女言: 「國王枉捶我。」龍王曰: 「此王常仁慈, 何橫捶人?」龍王冥作一蛇, 於床下聽王, 王語夫人: 「我行見小女兒為牧牛人所捶, 我解使去。」龍王明日人現, 來與王相見, 語王: 「王有大恩在我許, 女昨行為人所捶, 得王往解之, 我是龍王也, 在卿所欲得。」王言: 「寶物自多, 願曉 百鳥畜獸所語耳。」龍王言: 「當齋七日, 七日訖來語, 慎勿令人知也。」如是王與夫人共飯, 見蛾雌語雄取飯, 雄言: 「各自取。」雌言: 「我腹不便。」王失笑, 夫人言: 「王何因笑?」王默然, 後與夫人俱坐, 見蛾緣壁相逢, 諍共鬪墮地, 王復失笑。夫人言: 「何等笑?」如 [A10]是至三, 言: 「我不語汝。」夫人言: 「王不相語者我當自殺。」王言: 「待我行還語汝。」王便出行。龍王化作數百頭羊度水, 有懷妊牸羊呼羝羊: 「汝還迎我。」羝羊言: 「我極不能度汝。」牸言: 「汝不度我, 我自殺。汝不見國王當為婦死。」羝羊言: 「此王癡為婦死耳, 汝便死謂我無牸羊也。」王聞之, 王念: 「我為一國王, 不及羊智乎?」王歸, 夫人言: 「王不為說者當自殺耳。」王言: 「汝能自殺善, 我宮中多有婦女, 不用汝為。」師曰: 「癡男子坐婦欲殺身也」。」(CBETA 2025.R1, T04, no. 206, p. 514b21-c15) [9]. |

| 25 | “There was once a husband who went in search of deer liver for his pregnant wife. In his quest, he killed a black snake which he found fornicating with a white snake. The black snake’s mate was very thankful to the man and granted him the gift of animal language. One day, the man heard a conversation between cockroaches which made him laugh. His wife asked him to teach her the language of animals. She said, ‘Alas, if you don’t teach me the language of the animals, I will die.’ The husband was in a quandary. He could not teach the language of the animals to his wife. If he taught her, he himself would die. In the end, he learnt, from a conversation he overheard between a billy goat and a nanny goat, and between a chicken and a hunting dog, how to deal with his wife. He threatened to throw a spear at his wife, and having frightened her off, later married a younger wife.”. |

| 26 | “9.//dene ta ing jati nira/pumamh sarpa neggih sarpa narpati/duk miyarsa aturipun yeku waduling garwa/nulya ngakak ngadug kang pethit lir pecut tutuk menga mijil wisa/kalangkung ngajrih ajrihi//10.//dyan budhal nyawara kumrasak gumarubug den iring angin angina nedya nyedani Sang Prabu/anyjurug ing kadhatyan lan sumusup sanalika santun wujud tan pisan yen kawistara/pan awarna sawer kisi//”. VII Tiyang mangretos dhateng basaning sato kewan. (Wiraga 1929, Vol. 1, p. 38). |

| 27 | “He who his special treasure on his wife will throw away, Cannot keep her faithful ever and his life he must betray.” (Francis and Thomas 1916, p. 262). |

| 28 | “Clever judicial decisions” (Thompson 1955, Vol. 4, p. 82). |

| 29 | For killing a cat, a mongoose, a blue jay, a frog, a dog, a monitor lizard, an owl, a crow, a man should perform the observance for killing a Śūdra.” (“mārjāranakulau hatvā cāṣaṃ maṇḍūkameva ca/śvagodholūkakākāṃśca śūdrahatyāvrataṃ caret” cf. (Olivelle 2005, p. 861). |

| 30 | “pipīlikānaṃ saddaṃ, viravantī carati, tassa ravaṃ”. (Huang 2014). |

| 31 | Defined as a real and unequivocal historical period dominated by Āryan socio-cultural guidelines, the Vedic Age established a distinct and influential paradigm for the subcontinent. This dominance is vividly illustrated in narrative traditions: the divine metamorphosis into a ram, for instance, encapsulates the Aryan belief in direct intervention as a mechanism of judgment. Furthermore, the dissemination of this motif into folk tales marks its assimilation from the religious into the secular sphere, demonstrating the pervasive influence of the Vedic paradigm. |

| 32 | “Transformations supernatural being into a goat”. (Thompson 1955, Vol. 2, p. 19). |

| 33 | “Nature of the lower world”. (Thompson 1955, Vol. 1, p. 135). |

| 34 | This table presents a sequence following the oldest versions of the stories among those listed. |

| 35 | (Francis and Thomas 1916, pp. 259–62). |

| 36 | “Raja Aridarma yang Mengenal Bahasa Hewan. 4.302–4.326”. (Soekatno 2009). |

| 37 | (Soekatno 2009, pp. 334–39). |

| 38 | (Winstedt 1985, pp. 50–56). |

| 39 | (Wiraga 1929). Serat Bajan Budiman Djilid I, VII: tiyang mangretos dhateng basaning sato kewan. Weltevreden (Jakarta): Balai Pustaka, Vol. 1, pp. 52–59. |

| 40 | For online photographic resources, see https://www.clevelandart.org/print/art/1962.279.278.b (accessed on 15 June 2025). |

References

- Braginsky, Vladimir. 2004. The Heritage of Traditional Malay Literature. Leiden: KITLV Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braginsky, Vladimir. 2009. Tissue and Repository of Quotations: Translations from Persian in Traditional Malay Literature with Special Reference to Persian Stories. In Sadur: Sejarah Terjemahan di Indonesia dan Malaysia. Jakarta: Gramedia–École Française d’Extrême-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Cowell, Edward Byles, Robert Chalmers, and William Henry Denham Rouse. 1901. The Jātaka or Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births. London: Cambridge University Press, Volume 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Henry Thomas, and Edward Joseph Thomas. 1916. Jataka Tales: Selected and Edited with Introduction and Notes. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B., trans. 2014. Baliyu duben 巴利語讀本 [A reader in Pāli language]. Shanghai: Zhongxi shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Yijiu 金宜久. 1987. Yisilan Gailun 伊斯兰教概论 [Introduction to Islam]. Xining: Qinghai renmin chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Julan. 2006. A Comparative Study of The Parrot Story and Indian Folk Tales. In Studies in the East: Ancient Eastern Civilizations. Edited by Zhang Yu’an. Beijing: Economic Daily Press, p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw, Yock Fang. 2013. A History of Classical Malay Lierature. Jakarta: Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, R. 1960. Jātaka, Pañcatantra, and Kodi Fables. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 116: 232–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivelle, Patrick. 2005. Manu’s Code of Law. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Shan 潘珊. 2016. Yingwu Yetan: Yindu Yingwu Gushi De Wenben Yu Liuchuan Yanjiu 鹦鹉夜谭——印度鹦鹉故事的文本与流传研究 [Nocturnal Discourses of the Parrot: A Study on the Text and Transmission of the Indian Parrot Stories]. Beijing: Zhongguo dabaike quanshu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, Anthony. 1988. Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce 1450–1680 The Lands Below the Winds. New Haven: Yale University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, Anthony. 2000. Charting the Shape of Early Modern Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Simsar, Muhammed A. 1978. Tales of a Parrot. Ohio: Cleveland Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Soekatno, R. A. G. 2009. Kidung Tantri Kediri: Kajian Filogogis Sebuah Naskah Jawa Pertengahan. Ph.D. dissertation, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]