Abstract

This paper focuses on the image evolution of Shi Daoji (Ji Gong), a monk of the Southern Song Dynasty, and explores its important significance in the history of Chinese Buddhism. The historical authenticity of Dao Ji was once questioned, but the Epitaph written by Jujian, provides key evidence for his existence. It records Dao Ji’s origin, ordination, personality, and behavioral characteristics, establishing the prototype for later Ji Gong legends. Initially, Dao Ji existed as an “unconventional monk” with eccentric behaviors yet possessing spiritual legitimacy. During the Song-Yuan period, huaben (vernacular tales) and recorded sayings shaped him into a “San Sheng” (Uninhibited Sage), which conformed to the characteristics of Buddhism’s sinicization and gained widespread acceptance among the people. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, Dao Ji was further recognized as an “Arhat Yingzhen” (a realized Arhat), and his Chan lineage was gradually clarified in lamp records, with his status continuously elevated. The evolution of Dao Ji’s image reflects the process of Buddhism’s secularization and sinicization. It not only embodies the influence of folk beliefs on orthodox Buddhism but also reveals that Buddhism needs to integrate into people’s lives to complete its localization, providing a unique perspective for understanding the development of Chinese Buddhism.

1. Introduction

Monk Shi Daoji of the Southern Song Dynasty holds a particularly distinctive position in the history of Chinese Buddhism. As a monk within the lineage of orthodox Buddhist monks, he did not exert prominent influence during his lifetime. Although he was later recognized as the Sixth Patriarch of the Yangqi 楊歧 School of Chan Buddhism and inherited the Dharma lineage of Xiatang Huiyuan 瞎堂慧遠 (1103–1176), his actual impact on Buddhist doctrines remained relatively limited—a fact evident in the relevant historical records of the Southern Song Dynasty during his lifetime. However, the image of Jigong, portrayed as an incarnation of an Arhat, is undoubtedly one of the most influential symbols in the history of Chinese Buddhism and has exerted an incredibly profound influence on the secular lives of the general public. The Chinese academic community has produced a wealth of research findings on Jigong, which, on the whole, focus on three main directions:

The first is the research on Jigong-related literary works. These studies demonstrate the development of Jigong-related literature from simple early records to complex later creations, reflecting that literary creation is influenced by religion and folk culture, as well as the vital role of literature in the dissemination and shaping of Jigong’s image. Notable scholars include D. Wang (1989), Zhang and Su (1993), Hu (1999), Li (2012), Zhu (2013), and Xiang (2013). Next is the research on Jigong’s artistic image. The focus of the research lies in how Chan Master Daoji evolved into the image of Jigong, as well as the connotations and cultural significance of that image. Studies indicate that the evolution of Jigong’s image is influenced by multiple factors, including folk legends, literary creations, and religious culture, reflecting the values and cultural demands of different social strata. Notable scholars include Xu (1990), Tan (2014), Zhang (2020), and M. Wang (2025).

Finally, is the research on the Jigong belief. Studies show that the Jigong belief developed gradually from spontaneous folk worship, integrated various cultural elements, and exerted a positive influence on social ethics and cultural exchange, reflecting the spiritual desires and values of the people. Notable scholars include Lu and Peng (2008) and Xu (2012).

Some scholars have also recognized the significant impact of interactions between religion and folk cultures on the formation of the Jigong phenomenon: Xu (2012) focused on examining how Jigong was accepted by monasteries; M. Wang (2025) concentrated on textual research, arguing that the formation of Jigong’s image and narratives is not only a process where religious resources nourish literary narratives, but a two-way interaction in which popular discourse feeds back into Buddhist texts.

Previous Western scholarship on Chinese Buddhist history was predominantly based on a ‘Sacred Narrative.’ This paradigm shift began with Kieschnick (1997), as attention to the secular dimensions of Buddhism evolved into a prevailing research trend. The specialized study of Jigong should be regarded as a concentrated embodiment of this intellectual trend—though internationally. While scholarly monographs dedicated to Jigong remain relatively scarce, a prominent work in this field is Crazy Ji: Chinese Religion and Popular Literature by Israeli scholar Meir (1998), which presents his long-term research findings on Jigong from the perspectives of religion and literature. Meir Shahar’s research on Ji Gong represents the most comprehensive contribution in Western Sinology over the past half-century, particularly in synthesizing and enhancing foundational works from Ruhlmann (1960) to Mair (1990). In this book, the author narrates Daoji’s life in the form of a biography, explores how Daoji, as an eccentric monk, gained strong religious influence through the dissemination of popular literature, and conducts an in-depth study on the complex developmental process of the Jigong belief. As a significant work in the systematic study of Jigong, this book vividly demonstrates the complexity and diverse charm of Chinese religion by combining literary research with social and historical methodologies.

Over the past two decades or so, James Robson has been consistently focusing on the phenomenon of “eccentric monks” in Buddhism. While the focus of his research differs from that of this paper, it nonetheless indicates that “eccentric monks in China” is a phenomenon with vast appeal.1

It should be noted that, while Japan has invested considerable research efforts into Chinese traditions, no dedicated monograph on Ji Gong has been published to date. In general, Japanese Buddhist historiography tends to portray Ji Gong primarily as a rebellious figure, emphasizing his identity as a “mad monk.” Notable examples include Yanagida (1985), Ishii (1991), Kimura (1999), Ogawa (2010), and Yamaguchi (2004). These scholars generally regard Ji Gong as a unique phenomenon within Chinese religious and cultural traditions that cannot be replicated in Japan–a perspective that may partly explain the absence of specialized monographs on the subject.

Existing studies have primarily focused on the literary portrayal or religious connotations of Ji Gong’s image. Yet, few have systematically analyzed the complete context of its evolution by integrating the background of Buddhism’s sinicization and differences over history. Centered on literary research methods and informed by a cultural interpretation perspective, this study primarily examines texts that portray Ji Gong’s image across different periods. Through the analysis of these literary texts, the process, characteristics, and evolutionary logic of Daoji’s transformation from an “unconventional monk” to an Arhat are revealed, and the underlying religious and cultural connotations are explored. While drawing on historical contextual materials such as the era background of Buddhism’s sinicization and the development of folk beliefs, this paper does not focus on the historical verification of Daoji’s life and actions. The innovation of this study lies in clearly presenting the evolutionary trajectory of Daoji’s image from an “unconventional monk” to an “Arhat” through sorting out cross-period texts. By integrating this trajectory with the sinicization of Buddhism and the development of folk beliefs, it reveals the interactive relationship between literary image construction and the religious culture of the times, thereby providing a new analytical perspective for the research on religious figures.

In terms of research methods, unlike previous studies that analyzed literary texts or historical contexts in isolation, this paper constructs an integrated framework combining close reading of literature with cultural semiotics. It examines how Daoji’s image serves as a “negotiating symbol” between orthodox Buddhism and folk culture—tracking the evolution of its symbolic meanings across different text types and historical periods.

In terms of research perspective, existing studies mostly emphasize Daoji’s “madness” trait, while this study further explores the two-way dynamics reflected in the evolution of his image: it is not only how Buddhism adapted to secular society, but also how folk society actively reshaped Buddhist symbols to meet its own ethical needs. In other words, the formation of Daoji’s image results from a two-way interaction.

This paper is divided into three main parts, which are progressively structured to support the core argument: The first part focuses on Daoji’s initial image as an “unconventional monk,” his behavioral characteristics, and his early attempts to integrate into orthodox Buddhism. Section 2 explains how Daoji gained widespread acceptance in secular society through the unique symbol of “San Sheng” (Uninhibited Sage), a key sign of Buddhism’s sinicization, while the final segment explores how, in response to Buddhism’s need for secularization, Daoji completed the process of being recognized as orthodox within the Chan school by virtue of his identity as an “Arhat Yingzhen” 羅漢應真 (a realized Arhat).

2. Dao Ji: The “Unconventional Monk” of the Southern Song Dynasty

There has been a long historical debate over whether Dao Ji actually existed. For instance, Jiang Ruizao 蔣瑞藻 argued in Huachao Sheng’s Notes 花朝生筆記:

It is commonly said that there was a mad monk named Jigong in the Southern Song Dynasty, whose stories are filled with extraordinary and magical elements. Popular printed works such as Jigong Zhuan 濟公傳 (The Legend of Jigong), Jieda Huanxi 皆大歡喜 (All Rejoice Together), and Zhang Xinqi’s 張心其 opera script Zui Puti 醉菩提 (Drunken Bodhi) all elaborate on his deeds. In fact, there was no such person in the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279), the tales are misattributed to him, originating from the Buddhist monk Shi Baozhi 釋寳志 of the Six Dynasties (229–589) period. Baozhi’s supernatural and miraculous deeds are extensively recorded in Nanshi 南史 (The History of the Southern Dynasties), with particularly detailed accounts in Luoyang Jialanji 洛陽伽藍記 (Record of the Saṃghārāma of Luoyang) written by Yang Xuanzhi 楊衒之 of the Northern Wei Dynasty.(Jiang 1984, p. 627)

Jiang Ruizao held that there was no such person as Dao Ji in the Southern Song Dynasty; the various miraculous stories about Dao Ji fabricated by later generations actually originated from the deeds of Monk Baozhi. It was merely due to the erroneous spreading of these stories among the people that they became associated with Dao Ji. Jiang first put forward this view in 1912. Subsequently, in 1913, Qian Jingfang 錢靜方 also stated in Zui Puti Yuanben Kao 醉菩提院本考 (A Study of the Opera Script Drunken Bodhi):

Drunken Bodhi portrays Dao Ji, a mad monk of the Southern Song Dynasty, as an incarnation of a Bodhisattva and a disciple of Buddhism, who indulges in playful transcendence and pretends to be insane. In reality, this figure should be dated to the Six Dynasties period, yet the opera script mistakenly places him in the Southern Song Dynasty of the Zhao clan… There are numerous events in Baozhi’s life worthy of being recorded. Later generations, based on these events, created various extraordinary tales, but mistakenly attributed them to someone named Dao Ji and incorrectly set the time in the Southern Song Dynasty of the Zhao clan. As a result, various Buddhist monasteries around West Lake fabricated all sorts of miraculous traces to deceive the local common people. In fact, Jigong is a misnomer for Baozhi—there was no such person as Dao Ji at all.(Qian 1957, pp. 133–34)

This became the fundamental view denying Dao Ji’s actual existence in the Southern Song Dynasty, holding that all constructions of Dao Ji’s image were in fact based on Monk Baozhi and that there was no person named Dao Ji in the Southern Song Dynasty. Although this view was later refuted by substantial evidence, it still exerts some influence on the research of Dao Ji and related cultural phenomena.2

2.1. Daoji as a Historical Figure

In fact, Monk Jujian 居簡 (1164–1246), who lived slightly later than Dao Ji, clearly confirmed the undisputed authenticity of Monk Dao Ji’s existence in his work Huyin Fangyuansou Sheliming·Jidian 湖隱方圓叟舍利銘 濟顛 (The Epitaph for the Śarīra of Fangyuansou, the Hermit of the Lake·Jidian, hereafter, Sar.Epitaph). As the earliest documented record of Monk Dao Ji to date, this epitaph undoubtedly holds a prominent position in relevant research on Dao Ji. Jujian’s epitaph is relatively concise, and its full text is recorded as follows:

All those who consistently uphold goodness possess Buddhist relics; they were not seen because the jvāla (闍維 Buddhist cremation) ritual was not used. The townspeople of the capital were astonished and talked widely about the translucent clarity of the Buddhist Śarīra of Fangyuansou, the Hermit of the Lake, yet they knew nothing of his life.

Fangyuansou was a distant descendant of Li Wenhe 李文和, the Duwei 都尉 (military commander) of Linhai in Tiantai. He was ordained by Master Fohai 佛海 (Xiatang Huiyuan) of Lingyin Temple, known for his wild yet detached nature, his integrity, and his purity. His writings were unpolished and often deviated from conventional norms, yet they transcended ordinary bounds, embodying the free-spirited elegance of renowned monks and scholars from the Jin and Song dynasties.

He wandered half the world on faith, drifting destitute for forty years, traversing Mount Tiantai 天台, Mount Yandang 雁宕, Mount Kanglu 康蘆, and the Mountain Qianwan 潛皖, leaving behind inscriptions and calligraphy of exceptional elegance. He had no decent clothes in summer or winter—if given money, he would quickly hand it over to the tavern keeper. With no fixed place to sleep or eat, he would bravely procure medicine and food for the elderly and ailing monks. When invited to visit relatives’ homes, he would refuse without reason. He was somewhat similar to the Sichuan monk Juelao, though Juelao was more humorous.

When Master Jue died, Fangyuansou asked me to write a eulogy for him, saying: “Alas! In our Dharma, the depth of one’s learning is tested by how well they understand the moment of life and death—hence the saying, ‘Life and death are the greatest matters.’ Those who attain profound enlightenment and broad vision view birth and death as naturally as coming and going, day and night; even in hardship and urgency, how can they be troubled by life and death? It is like staying at an inn: once one has eaten and rested, they depart gracefully—how could they linger any longer? Monk Jue was unrestrained; his humor carried sharp wisdom. Though he did not follow ordinary conventions, he never overstepped moral boundaries. He often traveled alone in white socks, his mind serene and detached from worldly dust. Having transcended the gate of transmigration, a single day to him felt like a thousand years—he had long transcended the mundane world, facing life and death with ease even in casual conversation. Foolish people fail to understand this truth: some exploit the Dharma for personal gain; some flee to desolate wastelands, far from towns and cities; some cling rigidly to old rules, suppressing the opinions of others. They regard this vague, traceless state as the true Dharma, and dismiss clear teachings as mere jest. They denounce the practice of ‘sitting in extinction’ or ‘standing in passing’ (a state where accomplished practitioners pass away peacefully while sitting or standing) as heresy, casting it aside like driving away sheep—merely to promote a false version of Buddhism. These people gather to discuss: ‘This is not the Dharma we speak of.’ Yet, for those truly enlightened and transcendent, if they are not criticized by such people, they cannot be said to have understood the true Dharma.”

At that time, Fangyuansou added: “Alas, this eulogy can also be used to mourn me!” When he passed away, his state of calm transcendence was indeed no less than Monk Jue’s. Now, I offer this text as a memorial to him, fulfilling my promise.

Fangyuansou’s secular name was Dao Ji; “Hermit of the Lake” and “Fangyuan” were titles bestowed on him by people of his time. On the 14th day of the fifth lunar month in the second year of the Jiading era (1209 CE) of the Southern Song Dynasty, he died at Jingci Temple. The townspeople divided his Śarīra and enshrined them at the foot of Shuangyan (Twin Crags). The epitaph reads: If a jade disc does not break, who would cast it aside? His relics, like scattered stars around a plate, shine bright as the sun; if a merman does not weep, who would bring forth pearls? His relics, like large and small pearls rolling on a jade plate, glitter brilliantly (Mingfu 1981, vol. 5, p. 160).3

Master Jujian was a disciple of Zhu’an Deguang 拙庵德光 (1121–1203), who in turn was the direct Dharma heir of Dahui Zonggao 大慧宗杲 (1089–1163). Both Dahui Zonggao and Xiatang Huiyuan were Dharma heirs of Yuanwu Keqin 圓悟克勤 (1063–1135). This makes Daoji not only Jujian’s Dharma brother but also his senior uncle in monastic lineage. Moreover, Jujian had deep ties to Daoji’s birthplace, Taizhou, having served as abbot of Huangyan Banruo 般若 Temple and Taizhou Bao’en Guangxiao 報恩光孝 Temple. Before Daoji’s passing, Jujian visited Mount Tiantai. As he recorded:

In the spring of the second year of the Jiading 嘉定 era (1209 CE), I climbed Huading 華頂 Peak, crossed Shiliang 石梁 Bridge, visited Guoqing 國清 Temple, and rested at Folong 佛隴 Mountain. I was unexpectedly nourished by Daoist cultivation. I ascended the summit of Chicheng 赤城 Mountain and found the Huanchang well 浣腸井 dried up. After clearing it, a sweet spring gushed forth, its water milky-white in hue. Standing atop Shuji Cliff 書記岩, I overlooked the landscape, then descended to the Fenhao Pool 焚槁池, resting beneath Shiqian Rock 釋簽岩. The surrounding mountains and rivers left me lingering in awe. I couldn’t help but marvel: What a magnificent spectacle! The efforts of those who came before us had forged such splendor.4(Mingfu 1981, vol. 5, p. 17)

Amid these contextual relationships and Jujian’s consistently rigorous scholarly approach, his accounts of Daoji must be considered highly reliable. This brief epitaph contains information of profound significance for later generations:

- Lineage: Daoji was a descendant of Li Wenhe from Tiantai.

- Ordination: He became a monk under Xiatang Huiyuan at Lingyin Temple.

- Personality: “Wild yet detached, upright and pure”—an eccentric figure with the lingering spirit of Wei-Jin literati.

- Appearance: Ragged robes and constant companionship with wine.

- Actions: Skilled in medicine, aiding the common people, fearless of authority.

- Lifestyle: A wanderer adept in poetry and prose.

- Monastic names/titles: His dharma name, aliases, and date of death.

- Divine aspect: His relics glowed with crystalline brilliance.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the Stupa and statue of Ji Gong at Hupao Temple embodies his iconic traits—tattered robes, a bamboo fan in hand, and a playful yet compassionate expression—reflecting the integration of secular and divine attributes in his image. Comparing these traits with later depictions of Ji Gong in folklore, it is clear that the core characteristics of Ji Gong are already fully formed here, though embellishments of supernatural feats vary. In this sense, Jujian’s Relic Inscription can be regarded as the archetype for all subsequent Ji Gong legends.

Figure 1.

Jigong’s Stupa and Statue at Hupao Temple, Hangzhou.

2.2. Behavioral Trait of an Unconventional Monk: Madness

Equally noteworthy, in this inscription, Jujian explicitly refers to Daoji as Ji Dian (濟顛, literally “Mad Ji”). In Jujian’s time, the fundamental characterization of Daoji’s conduct was dian (顛), which, in its simplest sense, denotes divergence from common sense and norms—a reversal of expectations. This term underscores Daoji’s behavior, which was fundamentally at odds with conventional wisdom. Living in madness was, in fact, the prevailing judgment of Daoji’s contemporaries during the Southern Song Dynasty. Similar evaluations appear among his fellow monks from the same or slightly later periods. For instance, Master Po’an Zuxian 破庵祖先 (1136–1211) wrote in Please praise Ji Dian, lay Buddhist of Jian 戢庵居士請讚濟顛:

“The son of Xiatang, the descendant of a prince. In all his actions, he defies convention. Sage or mortal—impossible to discern, wild and rare, he shakes the cosmos. With a fist, he shatters the void, startling Mount Sumeru to stumble”.5

Master Yun’an Puyan 運庵普岩 (1156–1226) praised “Mad Ji, the Scribe” 濟顛書記 with the following verses:

Neither to condemn nor to praise—such a monk emerged from Tiantai, like a thunderclap in the clear sky, shocking the world. He roamed the capital, yet none could trace his steps. Bound by karma, he lived wildly, until a final somersault freed him from the dust of the world. Turning his back on the mundane, he forged a clarity as vast as heaven and earth. I bow to Mad Ji, yet still cannot fathom his truth. When we met on a narrow path, he pinched his nose, even the people of Puzhou laughed and called him a “mad thief.

Master Tiantong Rujing 天童如淨 (1163–1228) Praises “Mad Ji” 濟顛: “Five hundred oxen graze in Tiantai’s mountains, yet one leaps forth, wild and free. He outshines all worldly glories, with a tail in disarray, he turns the wheel of life” (Rujing Heshang Yulu n.d., in T (1983, vol. 48, No. 2002a, p. 131)8). (天台山裏五百牛, 跳出顛狂者一頭。賽盡煙花瞞盡眼, 尾巴狼藉轉風流.) Tianmu Wenli (1167–1250) praised “HuYin Ji Scribe” 湖隱濟書記 with these words: “He roams freely, chasing pleasures without restraint, yet his aim is to enlighten—once done, he moves on. Where do the alms he gathers go? Straight to the tavern, without a trace of shame” (Chanzong Zaduhai n.d., in Z (1994, vol. 65, No. 1278, p. 60)). (隨聲逐色恣邀遊, 只要教人識便休, 邏供得錢何處去, 堂堂直上酒家樓.).

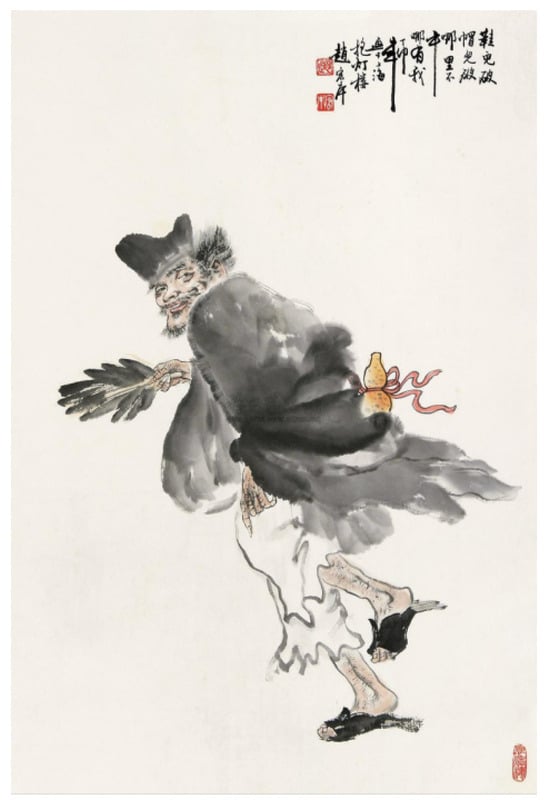

From these evaluations of Daoji, madness and eccentricity emerge as his defining traits. Though the perspectives vary, they collectively reflect his contemporaries’ fundamental view of him. As visually captured in Figure 2, Jigong’s 颠僧 Image, Painted by Zhao Hongben—the portrait depicts him in tattered robes, holding a bamboo fan, and wearing a playful grin, embodying the “madness” referenced in historical accounts. The epithet “Mad Ji” is referenced directly or indirectly across these accounts, revealing a shared consensus of the time. This consensus indicates two key points: Daoji’s lifestyle and behavior starkly contrasted with typical monks. While most monks adhered strictly to monastic discipline, he indulged in wine, freely expressed emotions, and championed justice for the oppressed. However, despite his defiance of norms, Daoji was undeniably a monk—his spiritual legitimacy remained unquestioned.

Figure 2.

Jigong’s 颠僧 image, painted by Zhao Hongben.

As a monk who defied monastic rules and lived in a unique way, Daoji’s behavior was extraordinary. Thus, madness became the most apt description—not a condemnation, but an affirmation of unconventional value. This tradition has deep roots in Chinese culture, akin to the madness and integrity of scholars. While both denote uniqueness, madness more strikingly embodies unconventional behavior, emphasizing individual expression. This behavior carries dual implications:

- Defying Common Sense: Its abnormality draws more attention because it defies common sense.

- Upholding Core Values: Despite appearances, it reinforces societal norms.

Historically, such madness flourished in post-Wei-Jin Dynasties, notably among scholars like Ruan Ji (famed for his “green eyes,” expressing appreciation, and “white eyes,” expressing disdain). With Buddhism’s rise, since the Wei, Jin, and Six Dynasties, this kind of uninhibited and unconventional behavior has frequently appeared in Chinese traditions. Examples include Monk Baozhi of the Southern Dynasties, as well as Hanshan, Shide, and Fenggan of the Tang Dynasty. Traditional responses were paradoxical: contemporaries often critiqued madness to uphold orthodoxy, yet tacitly acknowledged its spiritual merit. As seen in the writings of Jingshou Jujian, Po’an Zuxian, Yun’an Puyan, and Tiantong Rujing, madness was a contested but integral part of monastic discourse.

2.3. Attempts to Integrate into Orthodoxy: Similar to the Sichuan Monk Jue Lao

Jujian’s Sar.Epitaph is exceptionally unique and holds profound significance for Daoji-related research. As a scholar, Jujian demonstrated rigorous academic discipline—evident from other writings in the Beijian Collection 北磵集. Upon closer examination of the Sar.Epitaph, numerous aspects warrant deep scrutiny, including at least five critical questions:

- Why is it titled “Śarīra Epitaph” rather than “Pagoda Epitaph”?

- Why, as a native of “Buddhist Cave and Divine Source” Tiantai, did Daoji seek a eulogy from Fohai Huiyuan at Hangzhou’s Lingyin Temple instead of closer options?

- Why does Jujian address Daoji as “Sou” 叟 (elder) rather than “Shi” 師 (master)?

- Why is Daoji’s birth year omitted?

- Why does the text use “died” instead of “nirvāṇa” (ji 寂)?

Regarding these questions, our explanation is that it lies in the inscriptions. In fact, Jujian adopted a very special manner of expression, which is similar to the traditional Chinese “Chunqiu Bifa” (春秋筆法)—a technique of subtle historical critique. Jujian’s unconventional phrasing suggests Daoji was a contentious figure in monastic circles. A “mad monk” could not swiftly gain orthodox acceptance, forcing Jujian to reconcile Daoji’s legitimacy with institutional norms, thus crafting this paradoxical epitaph. Simply put, Jujian’s epitaph reflects a deliberate and painstaking effort: to secure public recognition for Daoji, the “mad monk,” he employed an unconventional approach.

Equally significant is the inclusion of the Shu monk Zujue (蜀僧祖覺, that is the Sichuan monk Juelao mentioned in the previous text), whose eulogy occupies nearly half the text—a narrative choice laden with intent. As Mr. Huang (2007) argues “Zujue may have been Daoji’s literary prototype, justifying Jujian’s extensive focus on him. However, I contend that Jujian’s juxtaposition of Zujue and Daoji carries deeper implications. While their behaviors were strikingly similar—with Zujue being ‘even more whimsical’—the critical distinction lies in Zujue’s posthumous recognition as a revered Chan master” (pp. 197–207). This establishes a compelling precedent: if Zujue’s eccentricity was sanctified, how much more should Daoji’s be tolerated? Jujian’s strategic framing thus serves as a bridge between Daoji’s iconoclasm and orthodox monastic acceptance.

If we broaden our perspective slightly and examine the the Lamp Records of Chan Buddhism compiled during the Southern Song Dynasty—such as Wu deng hui yuan 五燈會元 (Compendium of the Five Lamps) and Jiatai pu denglu 嘉泰普燈錄 (The Universal Lamp Record of the Jiatai)—we find no mention of Daoji. Similarly, in contemporaneous Buddhist historical texts like the Fozu tongji 佛祖統記 (Comprehensive History of the Buddha), Fozu lidai tongzai 佛祖歷代通載 (The General Record of the Buddha’s Successive Eras), and Wulin xihu gaoseng shilue 武林西湖高僧事略 (Biographies of Eminent Monks at West Lake in Wulin), Daoji’s deeds are conspicuously absent. This omission reveals the orthodox monastic establishment’s view of Daoji: he was considered an unconventional monk. From this vantage point, Jujian’s distinctive writing style in the epitaph becomes entirely comprehensible.

Furthermore, we can discern Daoji’s fundamental status in the Southern Song Dynasty: he was a monk whose lifestyle and conduct differed markedly from conventional monastic norms—essentially an outlier among monks. However, Chan Buddhism during this period remained “the dominant form of elite monastic Buddhism” (Van Overmeire 2017). As an unconventional Buddhist monk, Daoji’s eccentric behavior was clearly difficult for the orthodox monastic community to accept. Nevertheless, in the process of Buddhism’s sinicization, it was inevitable that Buddhism would be influenced by Chinese culture, giving rise to witty and alternative eminent monks like the monk Zujue from Sichuan—and this helped lay the groundwork for Daoji’s acceptance by orthodox Buddhism.

3. The “San Sheng”: The Pivotal Point in the Transformation of Daoji’s Image

3.1. San Sheng: A Special Symbol of Buddhism’s Sinicization

The term “San Sheng” 散聖 (Uninhibited Sage) refers to a highly distinctive figure in Chinese Buddhism, particularly within the Chan 禪宗 tradition. As noted in The Song gaoseng zhuan 宋高僧傳 (Biographies of Eminent Monks of the Song Dynasty): “Among Chan practitioners, those who leave written works are considered ‘awakened speakers’ (發言先覺), while they relegate Puhua 普化 to the category of ‘San Sheng,’ stating that such figures are ‘not part of the regular ranks’ (非正員)” (Zanning 1987, p. 511). (禪宗有著述者, 以其發言先覺, 排普化為散聖科目中, 言非正員也矣.).

From this definition, an “Uninhibited Sage” in Buddhism must meet two key criteria:

- Awakened speaker: They must possess unique insights, articulating what others have not yet perceived—thus embodying the role of a pioneer.

- Not part of the regular ranks: They exist outside the orthodox lineage, lacking formal recognition within institutionalized Buddhist traditions.

The concept of the “San Sheng,” as delineated in the Song gaoseng zhuan 宋高僧傳, emerges as a distinctive manifestation of the sinicization of Buddhism—a fusion of Chan Buddhist thought with traditional Chinese intellectual paradigms. This archetype fundamentally represents the convergence of Buddhist doctrines with indigenous Chinese ideals of sageship and reclusion. In Chinese tradition, sages denote individuals of prophetic insight and exemplary conduct, serving as aspirational ideals and moral compasses for society. Parallel to this, the philosophy of reclusion, deeply rooted in Daoist thought, transcends literal withdrawal from society; it emphasizes attaining inner tranquility through harmonizing with the dust of the world (heguang tongchen 和光同塵)—a mode of spiritual engagement that prioritizes mental equanimity within mundane existence. This latter aspect is particularly significant, as it directly bridges transcendent ideals with the lived experiences of ordinary people. Thus, the “San Sheng” epitomizes the creative synthesis of these traditions: a figure who embodies Chan’s radical simplicity while mirroring the Chinese cultural valorization of sagely wisdom and adaptable reclusion.

The emergence of the “San Sheng” archetype represents a profound synthesis of Chan Buddhist thought and traditional Chinese cultural paradigms. This figure embodies three defining characteristics that resonate deeply with Chinese intellectual traditions:

- Sagely Insight as Prerequisite: All individuals designated as uninhibited sages are recognized as awakened pioneers (xianzhi xianjue 先知先覺), possessing the moral stature of Confucian sages. This sagely character explains their elevated historical evaluation—their unconventionality is tolerated precisely because it reflects a higher wisdom beyond rigid formalism.

- Transcendent Conformity: Their behavior manifests Confucius’ ideal of acting freely without transgressing boundaries 從心所欲不逾矩. While outwardly eccentric, their conduct demonstrates spiritual mastery that transcends external norms, aligning with the Daoist principle that true sages are not bound by forms 聖人無常形.

- Grassroots Empathy: Unlike cloistered monks, uninhibited sages live among common people—whether retreating to mountains or dwelling in cities—with an innate capacity to perceive popular aspirations.

This accessibility makes their spiritual authority more compelling than institutional pedigree: what matters is their authenticity in addressing people’s inner yearnings, rather than orthodox lineage or ritual solemnity. In this sense, the “San Sheng” symbolizes the most successful phase of Buddhism’s sinicization—the creation of spiritually potent figures who bridge transcendent ideals with everyday life. As the most distinctly Chinese Buddhist school, Chan’s greatest impact was realized in this archetype. Remarkably, both monastic authorities and laypeople regarded uninhibited sages with high esteem, reflecting a cultural phenomenon where unconventionality and sanctity coexist harmoniously.

3.2. The Characteristics of San Sheng in Traditional Chinese Culture

Thus, we may conclude that in the Chinese tradition, once an individual is recognized as a “San Sheng,” it essentially signifies broad acceptance—both in the social fabric of common people and within Buddhist monastic circles. The Jingde chuan deng lu 景德傳燈錄 (The Jingde Record of the Transmission of the Lamp) classifies ten such figures—including Master Baozhi 寳志, the Great Master Shanhui 善慧, Master Huisi 慧思, Master Zhiyi智顗, the monk Sengjia of Sizhou 泗州僧伽, Monk Wanhui 萬回, Master Fenggan 豐干, Hanshan 寒山, Shide 拾得, and the Budai Monk 布袋—as a distinct group. Many of these figures were renowned for their miraculous deeds and eccentric conduct, exerting profound influence in traditional society. The Jingde chuan deng lu 景德傳燈錄 describes them as “Chan masters of profound insight, though not formally ordained, were widely celebrated in their time.”

This assessment is profoundly insightful, encapsulating three layers of meaning: “Chan masters of profound insight” signifies their spiritual attainment, recognized by monastic traditions; “though not formally ordained,” denotes their reclusive, non-confrontational lifestyle; and “were widely celebrated in their time” attests to their broad societal acceptance. Thus, “San Sheng” were not only distinguished by their exceptional Chan cultivation and unconventional conduct, but also by their immense social influence. Historical records in texts reveal that such figures emerged recurrently since the Wei-Jin 魏晉 period, including luminaries like Master Baozhi, Fenggan, Hanshan, Shide, the Budai Monk, Puhua 普化, the Xianzi 蜆子 Monk, Master Duan Shizi 端師子, Lingcheng 靈澄, the Pig-Headed Monk 豬頭和尚, Guquan Dadao 穀泉大道, and Daoji. A comparative analysis of their depictions in monastic records reveals five defining traits:

- Unconventional Conduct: Their speech and behavior defied both societal norms and Buddhist precepts, often manifesting as mad wisdom. This eccentricity demonstrated their mastery of Chan principles—transcending rigid formalism to embody the essence of no-mind.

- Miraculous Abilities: In terms of behavioral characteristics, most “San Sheng” possess supernatural powers. Supernatural power is a significant issue in the history of Buddhism: as a religion, if Buddhism was to gain acceptance among the secular world, supernatural power served as a crucial catalyst. Fundamentally, however, Buddhism opposes the use of supernatural powers. Thus, according to biographies of monks, those who generally employed such powers would typically leave their local area or pass away (parinirvāṇa) to be reborn in another realm after using them. If one constantly displayed supernatural powers without restraint, they would inevitably meet a violent end, an untimely death, or a tragic demise. For the “San Sheng,” nevertheless, in the Degenerate Dharma Age (paścimakāla), supernatural power became an extremely important ability for them to manifest Buddhist teachings.

- Divine Incarnation: In terms of their origin, most “San Sheng” are regarded as the upasaṃhāra (responsive manifestations) of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. For instance, Baozhi is seen as the responsive manifestation of Avalokiteśvara 觀音菩薩, Chan Master Fenggan as the incarnation of Amitābha Buddha 阿彌陀佛, Hanshan as the incarnation of Mañjuśrī 文殊菩薩, Shide as the incarnation of Samantabhadra 普賢菩薩, Budai as the incarnation of Maitreya 彌勒, and the “Pig-Head Monk” as the responsive manifestation of Dīpaṃjana Buddha 定光佛. Precisely because of this, in later Buddhist biographies and Lamp records, they are often referred to as “Responsive Manifestation Sages” (Yinghua Shengxian 應化聖賢) or “Responsive Manifestation Sages from the Western Paradise and the Eastern Land” (Xitian Dongtu Yinghua Shengxian 西天東土應化聖賢).

- Unaffiliated Lineage: Unlike mainstream Chan masters with documented lineages, figures like the Budai Monk, Fenggan, Hanshan, and Shide lacked clear dharma transmission records, existing outside institutional orthodoxy.

- Adaptive Pedagogy: Their influence stemmed from skillful means (upāya-kauśalya) rather than rigid rituals. Mirroring their own spontaneity, they tailored teachings to individual capacities—akin to teaching in accordance with aptitude. This flexibility rejected uniform methodologies, embracing diverse forms to resonate with practitioners’ varying dispositions.

3.3. From an Unconventional Monk to San Sheng: Daoji’s Wide Acceptance by Secular Society

If we examine the Jidian Daoji chanshi yulu 濟顛道濟禪師語錄 (Recorded Sayings of Chan Master Daoji, Known as Jidian, hereafter, RS of Chan Master Jidian) and other later huaben 話本 (vernacular tale) and novels about Jigong, it becomes evident that the portrayal of Daoji in these later works clearly exhibits the aforementioned characteristics—particularly in his unconventional conduct, which vividly embodies these traits. In fact, such features were already discernible in Southern Song-era accounts, whether in Jijian’s Sar.Epitaph or the descriptions by ancestors like Po’an Zuxian Yulu 破庵祖先語錄 (Recorded Sayings of Ancestor Po’an). These records present Daoji as a “San Sheng,” though later huaben and novels expanded and embellished his image with more detailed, intricate, and dramatic narratives, thereby refining and enriching the historical figure of the “mad monk” Daoji.

The earliest explicit record designating Daoji as a “San Sheng” appears in the RS of Chan Master Jidian. Following his parinirvāṇa, eminent monks from Hangzhou monasteries presided over his funeral ceremony with cremation, composing six liturgical texts in accordance with Buddhist protocol: Text for the Ritual of Enshrining the Spirit Portrait (rukan wen 入龕文), Text for the Ritual of Conveying the Coffin to the Cemetery (qikan wen 起龕文), Text for the Ritual of Hanging the Portrait of the Deceased Venerable (guazhen wen 掛真文), Text for the Ritual of Igniting the Cremation Fire (binghuo wen 秉火文), Text for the Ritual of Exhuming the Deceased’s Remains (qigu wen 起骨文), and Text for the Ritual of Interring the Remains in the Stupa (ruta wen 入塔文). These texts meticulously chronicle Daoji’s legendary life of eccentricity. As Xuan Shiqiao 宣石橋 proclaimed, “Among the company of ‘uninhibited monks’ (who flout conventions), he acts beyond mundane norms yet adapts to enlightenment; before the gates of ‘Uninhibited Sages’ (who transcend formalities), he seeks truth through down-to-earth efforts and aspires to lofty spiritual realms” (Du 1980, p. 1244). (皮子隊裏, 逆行順化; 散聖門前, 掘地討天.).

Ningji An 寧棘庵 further eulogized, “The Tiantai “San Sheng” went unrecognized, reclining on willow, drifting among flowers in abandon” (Du 1980, p. 1245). (天台散聖無人識, 臥柳眠花恣飄逸.).

The use of “San Sheng” signifies this text’s foundational affirmation of Daoji’s identity. As the earliest huaben about Daoji, RS of Chan Master Jidian established the archetype for all subsequent Ji Gong novels. The oldest extant edition dates to 1569 (Longqing 隆慶 era), but bibliographic evidence—including Yang Shiqi’s 楊士奇 Wenyuan Ge Catalogue 文淵閣書目 (1366–1444)—suggests its circulation predates the Ming Dynasty (Yang 1937, p. 215). Given the oral transmission patterns of huaben, its composition likely formalized during the Yuan 元 Dynasty, shortly after Daoji’s lifetime (Southern Song Dynasty). By this period, his legend had already spread widely through the dissemination of folk narratives.

The rise of huaben played a pivotal role in defining Daoji’s image as a “San Sheng.” From Southern Song Dynasty epitaphs to Chan master records, earlier textual portrayals of Daoji primarily framed him as an “unconventional monk” within Buddhist institutions—his erratic behavior coexisting with profound societal influence. However, huaben, targeting common folk, diverged sharply from clerical narratives. The public cared more about Daoji’s outrageous antics and their resonance with everyday life than about his monastic discipline. Thus, the huaben tradition heavily relied on compiling legends and supernatural tales. This amalgamation was not a direct borrowing from historical prototypes (e.g., Baozhi or Zujue) but a creative synthesis: based on Daoji’s documented traits, it logically grafted diverse miraculous stories—potentially attributed to other figures—onto his persona. Consequently, Daoji in huaben and novels became a composite of numerous legendary mystics and events. Some scholars speculate that due to the appearance of abnormal phenomena attributed to Buddhist relics (śarīra), Ji Dian was initially deified by the people, thereby “laying the foundation for the embryonic form of the Jigong belief” (Lu and Peng 2008). It was through this folkloric process that the “San Sheng” archetype was solidified and refined. Crucially, the widespread circulation of huaben gave Daoji mass appeal, transforming him from a niche monastic figure into a cultural icon. This grassroots acceptance later facilitated his canonization within orthodox Buddhist traditions, underscoring how vernacular storytelling bridged the gap between marginality and mainstream veneration.

The RS of Chan Master Jidian serves as a cornerstone in the construction of Daoji’s legendary biography. Its narrative storytelling and supernatural portrayal laid the foundation for the later development of the Ji Gong archetype. Within these accounts, Daoji’s “San Sheng” persona is both vividly embodied and explicitly affirmed. While in the Southern Song Dynasty, Daoji was still perceived as an “unconventional monk”—a figure met with mixed praise and criticism for his unorthodox behavior—the huaben and recorded sayings transformed him into a universally beloved “San Sheng.” By creatively refining and adapting the behavioral traits already acknowledged during the Southern Song, these texts sculpted Daoji into an amiable, unconstrained, and omnipotent figure dedicated to public welfare—a quintessential “San Sheng.” This positioning is unmistakably evident from the very beginning of the RS of Chan Master Jidian, particularly in the Wujingzai Zan Huyin 無競齋讚湖隱 (Praise of Lake Hermit, the No-Striving Studio), which clearly establishes this iconic portrayal:

Neither secular nor monastic, neither mortal nor immortal. He clears the thorny forest, penetrates the diamond ring. His brows are knotted, his nose points to the heavens. He burns his protective talisman, letting the ashes scatter like clouds. At times, he builds a hut and meditates atop a desolate mountain peak; at times, he sleeps in a tavern in the bustling streets of Chang’an. His spirit spans the nine provinces, yet his pockets hold not a single coin. When the time comes, he vanishes like a cicada shedding its shell. His relics emerge—eighty-four thousand in number. Praise is endless, yet he utters a final verse: Alas! This is why he is called Ji Dian (the Mad Monk)!(Du 1980, p. 262)9

By this point, Daoji’s image as a “San Sheng” had been successfully established. This demonstrated that while he held no special status within Chan Buddhism, his secular influence was vast, transforming him into the beloved and anticipated “Living Buddha” figure embraced by the populace. The folk reverence and adoration for Daoji naturally impacted orthodox Buddhism, with this influence manifesting in later Chan traditions. Thus, Daoji—once an “unconventional monk”—entered the lives of common people and became a “San Sheng,” marking a pivotal moment in the evolution of his iconic persona.

4. The Arhat: The Establishment of Daoji’s Legitimacy in Chan Orthodoxy

4.1. Daoji’s Image Meets the Needs of Buddhism’s Secularization

The formation of the “San Sheng” image, in a sense, marks the legitimation of Daoji within the Chan orthodoxy, as “San Sheng” itself constitutes a Buddhist archetype. The huaben and yulu indeed shaped Daoji’s persona from a Buddhist perspective, aligning it with the spiritual needs of commoners. This process naturally influenced how Chan institutions accepted Daoji’s image.

In reality, analyzing Chan Buddhism’s acceptance of Daoji is not overly complicated, given his inherent identity as a monk with a clear lineage—just like any ordained practitioner. The core question here is how the Chan orthodoxy chose to incorporate him. During the Southern Song dynasty (Daoji’s lifetime), his lifestyle blatantly violated monastic precepts, leading to his rejection by fellow monks. As recorded in Records of Jingci Temple, “Due to his eccentric habits—‘madness, alcoholism, meat-eating’—fellow monks complained, Xiatang Huiyuan said: ‘The Buddha’s realm is vast; why can it not accommodate a mad monk?’ From that time onward, people began calling him Ji Dian (Mad Ji)” (Du 1980, p. 259). (風狂嗜酒肉, 寺僧訐之, 瞎雲: “佛門廣大豈不容一顛僧”, 自是人稱濟顛.). The Sar.Epitaph thus served dual purposes: highlighting his behavioral traits and his exclusion by orthodox monks. Jujian’s Sar.Epitaph inscription for Daoji employed peculiar rhetoric precisely to address Daoji’s marginalized status. The fact that Daoji was not included in the lamp records, monastic histories, or monastic biographies of the Song and Yuan dynasties all indicates that the orthodox Chan school did not recognize Daoji’s image. However, with the popularity of yulu and huaben, the image of Daoji became deeply ingrained in the hearts of the people. As a “San Sheng”, Daoji embodied the profound significance of Buddhism in the daily lives of ordinary people. For Buddhism, this was of paramount importance, as it was through the popular acceptance and dissemination of Daoji’s image that Buddhism gained widespread influence and enduring vitality.

In this sense, the sinicization of Buddhism required more than just the adaptation of its doctrines—it had to penetrate deeply into the everyday lives of ordinary people, shaping and guiding their daily existence. Only then could it truly be considered an effective form of sinicization. And as a “San Sheng,” Daoji’s image fulfilled this function. Through this archetype, people in their lived reality embraced Buddhism. The folk construction of Jigong’s sanctity coincided perfectly with the need of orthodox Buddhism to interpret Jigong’s uniqueness, thus providing a usable legalized model for Jigong’s integration into orthodox Buddhism. By the late Ming Dynasty, Chan Buddhism placed greater emphasis on engagement with secular life, and its emphasis on Jigong was precisely a product of this secularization process (M. Wang 2025). In response, Buddhism naturally adopted a more affirmative stance toward Daoji’s image. Later, during the Hongwu 洪武 (1368–1398) reign of the Ming dynasty, Ju Ding compiled Xu Chuandenglu 續傳燈錄 (Continuation of the Lamp Records), formally recognizing Daoji as a disciple of Lingyin Xiatang Huiyuan and listing him as the 17th-generation successor of the Linji sect 臨濟宗, Master Dayan. This marked Daoji’s elevation to an orthodox position within Buddhism, signified by his inclusion in the legitimate Chan transmission lineage.

4.2. From San Sheng to Arhat: A Successful Case of Buddhism’s Secularization

This process of orthodoxy did not end there. If we refer to our earlier characterization of the “San Sheng,” as manifestations of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, then Daoji, as a true “San Sheng,” must naturally be such a manifestation. In this regard, even Master Tiantong Rujing pointed out, “Five hundred oxen graze in Tiantai’s mountains, yet one leaps forth, wild and free. He outshines all worldly glories, with a tail in disarray, he turns the wheel of life.” Since Tiantai was regarded as the gathering place of the Five Hundred Arhats 五百羅漢, and Daoji, as a monk from Tiantai, exhibited such miraculous deeds, Tiantong Rujing viewed him as one of the Five Hundred Arhats. This notion of Daoji as an incarnation of an Arhat became a crucial aspect of his later depictions, closely tied to Tiantai’s status as a sacred site of Arhats. Thus, Daoji’s rebirth as an Arhat became a foundational belief, consistently portrayed in yulu and huaben. However, this description was not entirely definitive in the RS of Chan Master Jidian. While the text identifies Daoji as the reincarnation of the Golden-Bodied Arhat, it also associates him with Maitreya’s advent.10 Subsequent legends, however, uniformly positioned Daoji as the reincarnation of the Golden-Bodied Arhat, aligning with Buddhism’s later canonization of his image. From a Buddhist perspective, Tiantong Rujing’s yulu was the earliest to link Daoji with Arhat reincarnation. This tradition was later adopted by orthodox Chan texts, such as Chuan Deng’s Tiantaishan fangwai zhi 天台山方外志 (Records of the Extraordinary in Tiantai Mountain):

Chan Master Jidian, a native of Tiantai, was born to Li Maochun, a descendant of Li, the son-in-law of Emperor Gaozong of the Song Dynasty, who served as a Chunfang Zan Shan (a court role in charge of advising imperial family members on ethics and studies) before retiring to Tiantai. His mother, Lady Wang, dreamed of swallowing sunlight before giving birth to him. At the age of eighteen, after losing both parents, he renounced the world and entered Lingyin Temple in Hangzhou, later residing at Jingci Temple. His actions defied convention—sometimes erratic, sometimes profound—and his miraculous deeds in aiding others and manifesting divine powers were numerous, as recorded in the RS of Chan Master Jidian. He was regarded as one of the Five Hundred Arhats incarnate in Tiantai.(Du 1985, p. 204)11

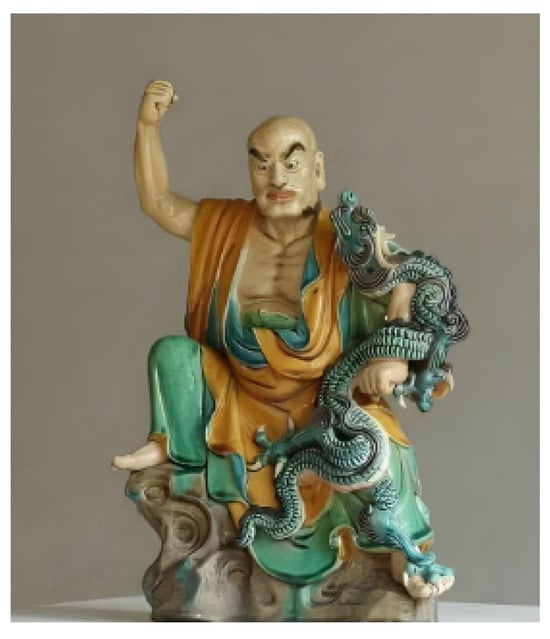

This indicates that orthodox Buddhist records had already embraced the fundamental concept of yulu and huaben, using the Five Hundred Arhats’ incarnations as an explanation for Daoji’s origins—an influence that profoundly shaped later generations. As illustrated in Figure 3, the Arhat Subduing the Dragon (Xianglong Luohan 降龙罗汉) is regarded as Ji Gong’s Buddhist prior incarnation in Chinese religious tradition.

Figure 3.

The Arhat subduing the dragon (降龙罗汉) is regarded as Ji Gong’s Buddhist prior incarnation in Chinese religious tradition.

Naturally, the question arises: Why was Daoji regarded as an Arhat’s incarnation? Beyond his Tiantai origin and the region’s status as the sacred site of the Five Hundred Arhats, this belief was deeply intertwined with the widespread Arhat veneration in Song Dynasty (960–1279) China. Positioning Daoji as an Arhat’s reincarnation unequivocally demonstrates orthodox Buddhism’s acceptance of him. This is of paramount significance.

The Arhat was initially introduced to China as the highest attainment in Theravada practice. Conceptually, it entails three layers of meaning:

- Eradication of Suffering: Liberating devotees from worldly afflictions.

- Worthy of Offerings: Receiving veneration from humans and celestial beings.

- End of Rebirth: Liberating beings from the cycle of saṃsāra.

In essence, the Arhat embodies the triple virtues of kleśa-hantā (sha zei 殺賊, destroying afflictions), yogyapūjya (ying gong 應供, being worthy of offerings) and anutpāda (wu sheng 無生, transcending birth-death cycles)—the ultimate attainment for one of the Buddha’s disciples. All those who have attained the Arhat fruit (Arahantship) are pure in body, mind, and the six sense faculties. They have eliminated ignorance and afflictions; they are worthy of respect and offerings from humans and celestial beings; and they have liberated themselves from the cycle of birth and death, attaining nirvāṇa. Before their lifespan is exhausted, they still abide in the world, practicing pure conduct with few desires, upholding precepts and virtues, and guiding and delivering sentient beings in accordance with conditions.

In this sense, Arhats take on the mission of protecting and propagating the Dharma in the human world after the Buddha’s parinirvāṇa. Since the Five Dynasties 五代 (907–960) and the Wuyue Kingdom 吳越 (907–978), the belief in Arhats has flourished, and the creation of Arhat statues has become prevalent across regions. Tiantai Mountain, as a sacred site for the Five Hundred Arhats, can be traced back to the Eastern Jin 晉 Dynasty according to Hui Jiao’s 慧皎 Gaoseng Zhuan 高僧傳 (Biographies of Eminent Monks)—a claim widely recognized in the Buddhist community. For instance, Records on the Western Regions 西域記 states, The Buddha said, In the human world, at Fangguang Sacred Temple on Tiantai Mountain in 震旦 (Zhendan, referring to China), reside the Five Hundred Great Arhats” (Du 1985, p. 66). (佛言震旦天台山方廣聖寺, 五百大羅漢居焉.). Within this historical and cultural context, the Arhat belief evolved into a distinctive faith that embodied both temporal and regional characteristics. The fusion of these two aspects crystallized the iconic image of Daoji as the “羅漢應真” (a realized Arhat). The acceptance of Daoji through the lens of Arhat authenticity reflects the high degree of recognition he received from orthodox Buddhism—a process profoundly influenced by folk Buddhist traditions.

4.3. Daoji Gained a Clear Chan School Dharma Lineage

Accompanying this process was the confirmation and consolidation of Daoji’s position within the orthodox Dharma transmission system. It had already been a settled during the Southern Song Dynasty that Daoji was a disciple of Chan Master Xiatang Huiyuan of Lingyin Temple. However, regarding Daoji’s specific position in the Chan lineage, there were no records in the biographies of monks or lamp records from the Song and Yuan dynasties onward.

The earliest confirmation of Daoji’s Dharma lineage can be found in Xu Chuandenglu 續傳燈錄 (Continuation of the Lamp Records) compiled by Juding 居頂 in the Ming Dynasty. In vol. 31:

The 17th Generation descended from Dajian (Huineng 慧能, the Sixth Patriarch)–nine Dharma heirs of Chan Master Huiyuan of Lingyin Temple, it is recorded: Chan Master Dongshan Qiji 東山齊己, Chan Master Shushan Rubin 竦山如本, Shangren Jue’e 覺阿上人 (Venerable Jue’e), Lay Buddhist Neihan 內翰Zeng Kai 曾開 (Neihan 內翰, a senior literary official), Lay Buddhist Zhifu 知府Ge Tan 葛郯 (Zhifu 知府, prefectural magistrate) [no further records exist for the above five]; Chan Master Jidian 濟癲 Shuji (Daoji, styled Shuji, a Secretary Monk), Chan Master Shouzuo首座Yao 堯 (Senior Monk Yao), Chan Master Liao Cheng 了乘 of Shanglan, Chan Master Huichong 慧沖 of Gongan [no further records exist for the above four].(Lan 2004, vol. 16, pp. 456–58)

This text clearly identifies Daoji as a lineage holder of Xiatang Huiyuan, a 17th-generation Chan master descended from Dajian. Additionally, Daoji ranks sixth among Huiyuan’s nine major Dharma heirs.

Subsequently, in Zeng Ji Xu Chuan Deng Lu 增集續傳燈錄 (Supplemented Collection of the Continuation of the Lamp Records), compiled by Nan Shi Wenxiu 文琇 in the 15th year of the Yongle 永樂 reign of the Ming Dynasty (1417), the entry “the 17th Generation Descendant of Dajian” was supplemented based on Wu deng hui yuan 五燈會元 (Compendium of the Five Lamps). In this supplement, Huyin Jidian Shuji (Dao Ji, styled Huyin 湖隱 Lake Hermit, and holding the position of Shuji, a Secretary Monk), was listed as a Dharma heir of Chan Master Xiatang Huiyuan of Lingyin Temple (Lan 2004, vol. 16, p. 708).

Checking Wu deng hui yuan 五燈會元 (Compendium of the Five Lamps) (Z 1994, vol. 80, No. 1565), under the entry “The 16th Generation of the Nanyue 南嶽 Branch of the Linji 臨濟 Sect,” five Dharma heirs of Chan Master Huiyuan of Lingyin Temple are recorded: Chan Master Dongshan Qiji 東山齊己, Chan Master Songshan Rubin 竦山如本, Shangren Jue’e 覺阿上人, Lay Buddhist Neihan Zeng Kai 曾開, and Lay Buddhist Zhifu Ge Tan 葛郯 (Lan 2004, vol. 8, pp. 1366–69). It can be seen that Wenxiu 文琇 supplemented the deficiency of Wu Deng Hui Yuan by adding Dao Ji to Huiyuan’s Dharma lineage.

In Chan Deng Shi Pu 禪燈世譜 (Genealogy of the Chan Lamp), compiled by Wu Tong 吳侗 and edited by Dao Tai 道忞 in the 4th year of the Chongzhen 崇禎 reign of the Ming Dynasty (1631), Volume 5, “Genealogical Chart of the Yangqi 楊歧 School of the Linji 臨濟 Sect under the Nanyue Branch” records the 16th-generation Dharma lineage and identifies nine Dharma heirs of Chan Master Huiyuan of Lingyin Temple: Songshan Rubin, Dongshan Qiji, Secretary Jidian (Dao Ji), Shouzuo Yao, Shangren Jue’e, Liao Cheng of Shanglan, Huichong of Gongan, Neihan Zeng Kai, and Zhifu Ge Tan. Notably, Dao Ji is ranked third here, indicating that he received greater recognition (Lan 2004, vol. 14, p. 1185).

In the catalogue of Xu deng zheng tong 續燈正統 (Continuation of the Orthodox Lamp Records) (Z 1994, vol. 84, No. 1582), compiled by Xing Tong 性統 in the 30th year of the Kangxi 康熙 reign of the Qing Dynasty (1691), under the entry, “The 17th Generation of the Linji Sect Descended from Dajian,” nine Dharma heirs of Chan Master Xiatang Huiyuan of Lingyin Temple are recorded: Chan Master Dongshan Qiji, Chan Master Songshan Rubin, Shangren Jue’e, Secretary Jidian (Dao Ji), Lay Buddhist Neihan Zeng Kai, Lay Buddhist Zhifu Ge Tan, Chan Master Liaocheng of Shanglan (with no recorded successors thereafter), Chan Master Huichong of Gongan, and Shouzuo Yao. Dao Ji also holds a relatively high position here, ranked fourth (Lan 2004, vol. 24, p. 13).

In the “16th Generation of the Nanyue Lineage” in the Wu Deng Quan Shu 五燈全書 (Complete Collection of the Five Lamps), compiled in the 32nd year of the Kangxi 康熙 Reign (1693), it is recorded that Chan Master Lingyin HuiYuan had six Dharma heirs, and Daoji was the fourth among them (Lan 2004, vol. 25, p. 94). Additionally, Volume 46 includes an entry for “Chan Master Dao Ji Jidian of Jingci Temple in Hangzhou” (Lan 2004, vol. 26, p. 1033), with content consistent with that in Xu deng zheng tong 續燈正統 (Continuation of the Orthodox Lamp Records).

In Xu zhi yue lu 續指月錄 (Continued Record of Pointing to the Moon), compiled by Nie Xian 聶先, Volume 1 records, under the entry “The 17th Generation of the Linji Sect Descended from the Sixth Patriarch,” six Dharma heirs of Huiyuan of Lingyin Temple: Chan Master Qingyuan Quan’an Qiji, Chan Master Lin’an Lingyin Jidian, Chan Master Fuzhou Shushan Ruben, Shangren Jue’e, Lay Buddhist Neihan Zeng Kai, and Lay Buddhist Zhifu Ge Tan. Here, Dao Ji is ranked second among Huiyuan’s six major Dharma heirs, marking a significant elevation of his status (Lan 2004, vol. 13, p. 24).

Finally, in An hei dou ji 揞黑豆集 (Chan Collection of Covering Black Beans), under the entry “The 17th Generation Descended from the Sixth Patriarch,” Dao Ji is directly placed ahead of Quan’an Qiji, Jue’e, and Ge Tan, ranking first among Huiyuan’s Dharma heirs (Lan 2004, vol. 28, pp. 19–21).

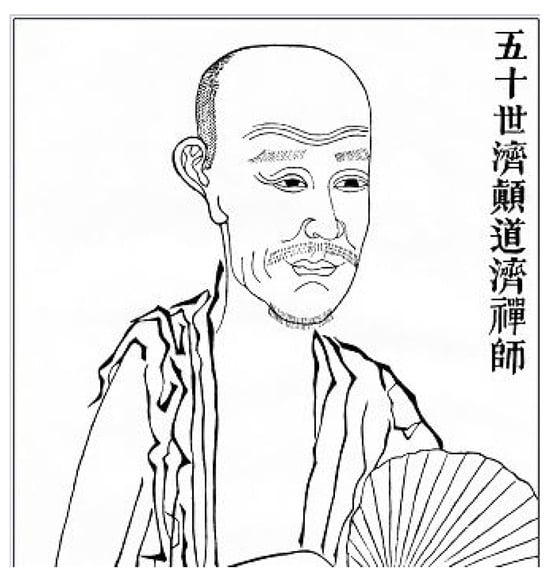

From this brief examination, we can roughly discern Daoji’s status within the orthodox Chan tradition from the Ming and Qing dynasties onward. Daoji was absent from the Chan lineage records of the Song and Yuan Dynasties (960–1368); however, beginning in the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368–1912), he not only appeared consistently in these records but also saw a steady rise in his ranking. This indicates that Daoji gained increasing recognition and received growing attention within the orthodox Buddhist community. Through the changes spanning from the Southern Song Dynasty to the Ming and Qing dynasties, Daoji finally secured an orthodox position in Buddhism. As reflected in Figure 4—the depiction of Ji Gong by Xuyun (虚云), the 50th Patriarch of Zen, in Buddha’s Image—this iconic Buddhist text, which systematically records the lineage of eminent monks and authenticates orthodox Dharma transmission, further consolidates Daoji’s recognition as a legitimate figure within the Chan tradition. By including Daoji in its compilation of revered Buddhist masters, Buddha’s Image endows his status with authoritative endorsement, marking his formal integration into the orthodox Chan lineage.

Figure 4.

The depiction of Ji Gong by Xuyun (虚云), the 50th Patriarch of Zen, in Buddha’s Image (《佛祖道影》).

5. Conclusions: The Significance of the Evolution of Daoji’s Image in the Context of Buddhism

From an “unconventional monk” in the Southern Song Dynasty, to an “uninhibited sage” during the transition from the Song to the Yuan Dynasties, and an “Arhat” in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the evolutionary trajectory of Daoji’s status within Buddhism, while exceptional, does not serve as an additional validation of the widely acknowledged fact of “Buddhism’s sinicization.” As a native Chinese monk, his existence itself is a natural manifestation of Buddhism’s integration into Chinese society, and his appeal to the secular world has already been emphasized in previous studies. The core value of this paper lies in breaking away from the traditional research framework centered on the sinicization of Buddhist doctrines. Taking the evolution of Daoji’s image as an entry point, it focuses on its uniqueness as a “contested field” in Buddhism’s sinicization, analyzing the dynamic two-directional construction process between folk beliefs and orthodox Buddhism behind the image’s shaping, rather than a one-way establishment of doctrines or social acceptance.

Previous studies have mostly focused on the adaptability between Buddhist doctrines and traditional Chinese thought. While this perspective can reveal the theoretical characteristics of sinicized Buddhism, limiting research to this dimension will inevitably lead to an imbalanced and even severely distorted understanding of Chinese Buddhism as a historical phenomenon (Erik 1982). In contrast, the evolution of Daoji’s image precisely reveals the practical dimension of Buddhism’s sinicization: from its inception, his image has been fraught with controversy, becoming a common arena in which Buddhist elites and folk society negotiate the connotation of “sinicization.” Such controversies and divergences are vivid reflections of the frictions between multiple forces in the process of Buddhism’s sinicization.

The three-stage evolution of Daoji’s image clearly presents the two-way interaction between folk beliefs and orthodox Buddhism. On one hand, through oral traditions and novel creations, folk society endows Daoji with secular spiritual connotations, enabling him to penetrate the daily lives of ordinary people and become a core carrier of folk Buddhism. Chapters from Ji Gong novels in the 16th and 17th centuries were incorporated into the official historical records of Lingyin Temple and Jingci Temple; subsequent Buddhist biographies of Ji Gong drew on the novelistic image; and ultimately, the novels Zui Putuo 醉菩提 (Drunken Bodhi) and the RS of Chan Master Jidian were classified as Buddhist canonical works (Meir 1998, pp. 215–16). This process provides compelling evidence of folk beliefs’ reverse shaping of orthodox Buddhism. On the other hand, orthodox Buddhism, by absorbing Daoji’s image and conferring upon him the status of “Arhat,” incorporated folk faith symbols into its own Dharma lineage system—responding to the spiritual needs of the people while completing the orthodox integration of secular elements. This dynamic process breaks the cognitive inertia of “orthodox Buddhism unilaterally influencing the folk,” demonstrating the diverse paths of Buddhism’s sinicization.

In summary, the evolution of Daoji’s image provides a unique practical case for understanding Buddhism’s sinicization. Rather than re-verifying the established fact of Buddhism’s sinicization, this paper highlights the core role of folk beliefs and orthodox Buddhism in negotiating the connotation of “sinicization” by analyzing its construction as a “contested field.” This perspective of two-way dynamic construction not only supplements the limitations of previous studies that focused excessively on doctrinal dimensions but also fully presents the practical logic of Buddhism’s sinicization—sinicization is not a one-dimensional transformation of doctrines or social adaptation, but a continuous process of interaction and negotiation among multiple forces through specific faith symbols. The vitality of Daoji’s image lies in its embodiment of the complexity and inclusiveness of this interaction, offering a new theoretical dimension for Buddhist history research and the analysis of religious figures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.W.; Methodology, T.W. and S.H.; Writing—original draft, T.W.; Writing—review and editing, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In 2014 and 2016, Robson delivered relevant lectures themed “A Crazy History of Buddhism: From Monasteries to Mental Institutions” at Fudan University and Zhejiang University, respectively. Robson’s primary focus was on the relationship between Buddhist monasteries and psychiatric treatment. He argued that the issue of Buddhism and madness holds significant practical significance—nowadays, in many parts of the world, especially in the United States and Europe, modern doctors and psychologists have incorporated certain Buddhist concepts into their psychotherapeutic practices, developing new Buddhist-based psychotherapies. This serves as the starting point of Robson’s interest in the “crazy” history of Buddhism, with the relationship between Buddhism and medicine being the ultimate focus of his research. |

| 2 | Nowadays, few people regard Dao Ji as a result of misattribution to Baozhi; instead, there is a general consensus on the existence of Dao Ji’s actual history. However, this does not mean that the “Baozhi Theory”—first proposed by Jiang Ruizao, Qian Jingfang, and others—has lost its influence. On the contrary, the introduction of this theory has precisely opened up an alternative possibility for current relevant research: that Baozhi served as the prototype for the Jigong image. |

| 3 | 舍利,凡一善有常者咸有焉,不用闍維法者故未之見。都人以湖隱方圓叟舍利晶瑩,而聳觀聽,未之知也。叟天台臨海李都尉文和遠孫,受度於靈隱佛海禪師,狂而疏,介而潔,著語不刊削,要未盡合準繩,往往超詣,有晉宋名緇逸韻。信腳半天下,落魄四十年,天台、雁宕、康廬、潛皖,題墨尤雋永。暑寒無完衣,予之,尋付酒家保。寢食無定,勇為老病僧辦藥食。遊族姓家,無故強之,不往。與蜀僧覺老略相類,覺尤詼諧。他日覺死,叟求予文祭之,曰: “於戲!吾法以了生死之際驗所學,故曰生死事大。大達大觀,為去來,為夜旦,顛沛造次,無非定死而亂耶?譬諸逆旅,宿食事畢,翩然幹邁,豈複滯留。公也不羈,諧謔峻機,不循常度,輒不逾矩。白足孤征,蕭然蛻塵,化門既度,一日千古,迥超塵寰,於談笑間。昧者昧此,即法徇利,逃空虛,遠城市,委千住,壓萬指,是滉漾無朕為正傳,非決定明訓為戲言。坐脫立亡,斥如斥羊,欲張贗浮圖之本也。相與聚俗而謀曰: 此非吾之所謂道。靈之邁往,將得罪於斯人,不得罪於斯人,不足以為靈所謂道也。”叟曰: “嘻,亦可以祭我!”逮其往也,果不下覺。舉此以祭之,踐言也。叟名道濟,曰湖隱,曰方圓,皆時人稱之。嘉定二年五月十四,死於淨慈。邦人分舍利,藏於雙岩之下。銘曰: 璧不碎,孰委擲,疏星槃星爛如日;鮫不泣,誰泛瀾,大珠小珠俱走盤。 |

| 4 | Another crucial detail in this passage is the mention of Shuji Cliff (书记岩). According to Jujian, this cliff was undoubtedly located on Chicheng Mountain. Later, the Shuji Cliff was regarded as a natural portrait of Daoji, and its name may have originated from Daoji’s role as a shuji (书记, scribe) at Jingci Temple. If the name indeed derives from Jujian, the relationship between Jujian and Daoji becomes even more profound, underscoring Jujian’s significance in the later development of the Ji Gong cult. |

| 5 | 瞎堂之子,駙馬之後。出處行藏,一向漏逗。是聖是凡莫測,掣顛掣狂稀有。一拳拳碎虛空,驚得須彌倒走。 |

| 6 | Scriptures in the Zoku Dai Nihon Zokuzōkyō 卍续藏经 are cited using the abbreviation Z along with their number in the text (Fozu tongji n.d.; Jiatai pu denglu n.d.; Jidian Daoji Chanshi Yulu n.d.; Wu deng hu yuan n.d.; Wulin Xihu Gaoseng Shilue n.d.; Xu deng zheng tong n.d.). |

| 7 | 毀不得,贊不得。天台出得個般僧,一似青天轟霹靂。走京城,無處覓。業識忙忙,風流則劇。末後筋斗,背翻鍛出,水連天碧。稽首濟顛,不識不識。挾路相逢撚鼻頭,也是普州人送賊。 |

| 8 | Scriptures in the Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō 大正藏 are cited using the abbreviation T along with their number in the text (Gaoseng Zhuan n.d.; Jingde chuan deng lu n.d.). |

| 9 | 非俗非僧,非凡非仙。打開荊棘林,透過金剛圈。眉毛廝結,鼻孔撩天。燒了護身符,落紙如雲煙。有時結茅晏坐荒山巔,有時長安市上酒家眠。氣吞九州,囊無一錢。時節到來,奄如蛻蟬。湧出舍利,八萬四千。讚歎不盡,而說偈言。嗚呼!此其所以為濟顛者耶? |

| 10 | The RS of Chan Master Jidian concludes with a verse on Maitreya’s manifestation: “The ascendant departs for the Longhua Assembly, leaving divine imprints engraved in jade towers.” 上人身赴龍華會,遺下神容記玉樓。 The allusion to the Longhua 龍華 Assembly directly references Maitreya’s future advent to save all beings. |

| 11 | 濟顛禪師,天臺人,父李茂春,高宗李駙馬之後,拜春坊贊善,隱於天臺。母王氏,夢吞日光生師。年甫十八,二親繼喪,投杭靈隱寺出家,後居淨慈。逆行順行,言行叵測,其濟物利生、神通感應事蹟至多,見《濟顛語錄》。乃天臺五百羅漢應真之流也。 |

References

- Chanzong Zaduhai 禪宗雜毒海 [The Sea of Miscellaneous Toxins in Chan Buddhism]. n.d., In Zoku Dai Nihon Zokuzōkyō (卍续藏经). Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司, vol. 65, no. 1278.

- Du, Jiexiang 杜潔祥, ed. 1980. Jingci sizhi 淨慈寺志 [Records of Jingci Temple]. In Zhongguo fosi shizhi huikan 中國佛寺史志匯刊 [A Collection of Historical Records of Chinese Buddhist Temples]. Series 1; Taipei 臺北: Mingwen Shuju 明文書局, vol. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Jiexiang 杜潔祥, ed. 1985. Tiantaishan fangwaizhi 天台山方外志 [Records of the Extraordinary in Tiantai Mountain]. In Zhongguo fosi shizhi huikan 中國佛寺史志匯刊 [A Collection of Historical Records of Chinese Buddhist Temples]. Series 3; Taipei 臺北: Danqing Books Co., Ltd. 丹青圖書公司. [Google Scholar]

- Erik, Zurcher. 1982. Perspectives in the Study of Chinese Buddhism. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 114: 161–76. [Google Scholar]

- Fozu tongji 佛祖統記 [Comprehensive History of the Buddha]. n.d., In Zoku Dai Nihon Zokuzōkyō (卍续藏经). Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司, vol. 75, no. 1514.

- Gaoseng Zhuan 高僧傳 [Biographies of Eminent Monks]. n.d., In Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō 大正藏. Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司, vol. 50, no. 2059.

- Hu, Sheng 胡勝. 1999. Jigong xiaoshuo de banben liubian 濟公小說的版本流變 [A study on the version evolution of Jigong novels]. Journal of Ming-Qing Fiction Studies 明清小說研究 3: 156–64. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Xianian 黃夏年. 2007. Huyin Fangyuansou Sheliming Kaoshi 《湖隱方圓叟舍利銘》考釋 [Textual Research and Interpretation of the Sar.Epitaph]. Foxue Yanjiu 佛學研究 1: 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, Shūdō 石井修道. 1991. Sōdai Zenshūshi no Kenkyū 宋代禅宗史の研究 [Studies in Song Dynasty Zen History]. Tokyo 東京: Daizō Shuppan 大藏出版株式会社. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Ruizao 蔣瑞藻. 1984. Xiaoshuo kaozheng xubian shiyi (xiace) 小說考證附續編拾遺 (下冊) [Textual Research on Novels, with Supplementary Sequel and Posthumous Fragments (Volume 2)]. Shanghai 上海: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe 上海古籍出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Jiatai pu denglu 嘉泰普燈錄 [The Universal Lamp Record of the Jiatai]. n.d., In Zoku Dai Nihon Zokuzōkyō (卍续藏经). Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司, vol. 79, no. 1559.

- Jidian Daoji Chanshi Yulu 濟顛道濟禪師語錄 [Recorded Sayings of Chan Master Daoji, Known as Jidian]. n.d., In Zoku Dai Nihon Zokuzōkyō (卍续藏经). Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司, vol. 69, no. 1361.

- Jingde chuan deng lu 景德傳燈錄 [The Jingde Record of the Transmission of the Lamp]. n.d., In Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō 大正藏. Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司, vol. 51, no. 2076.

- Kieschnick, John. 1997. The Eminent Monk:Buddhist Ideals in Medieval Chinese Hagiography. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, Seikō 木村清孝. 1999. 中国仏教思想史 [A History of Chinese Buddhist Thought]. Tokyo 東京: Shunjūsha 春秋社. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Jifu 藍吉富, ed. 2004. Chanzong quanshu 禪宗全書 [The Complete Collection of Chan Buddhism]. Bejing 北京: National Library of China Publishing House 北京圖書館出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xiangming 李向明. 2012. Gigong xiaoshuo de yanbian jiqi xingxiang jianxi 濟公小說的演變及其形象簡析 [A brief analysis of the evolution of Jigong novels and their character images]. Journal of School of Chinese Language and Culture Nanjing Normal University 南京師範大學文學院學報 1: 117–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Yao 路遙, and Suqing Peng 彭淑慶. 2008. Gigong xinang xingcheng yanbian de jidian sikao 濟公信仰形成、演變的幾點思考 [Some reflections on the formation and evolution of Jigong belief]. Folklore Studies 民俗研究 3: 168–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, Victor H. 1990. The Mad Monk Ji Gong. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meir, Shahar. 1998. Crazy Ji: Chinese Religion and Popular Literature. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mingfu 明復. 1981. Chanmen yishu chubian 禪門逸書初編 [Initial Series of Unofficial Buddhist Zen Texts]. Taipei 臺北: Mingwen Shuju 明文書局. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, Takashi 小川隆. 2010. 語録の思想史——中国禅のスポーツライティング [A History of Zen Texts: The Cultural Archaeology of Chan “Recorded Sayings”]. Tokyo 東京: Iwanami Shote 岩波書店. [Google Scholar]

- Po’an zuxian Yulu 破庵祖先語錄 [Recorded Sayings of Ancestor Po’an]. n.d., In Zoku Dai Nihon Zokuzōkyō (卍续藏经). Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司, vol. 70, no. 1381.

- Qian, Jingfang 錢靜方. 1957. Xiaoshuo Congkao 小說叢考 [Collected Textual Research on Novels]. Shanghai 上海: Gudian Wenxue Chubanshe 古典文學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhlmann, Robert. 1960. Ji Gong, le moine fou [JiGong, the Crazy Monk]. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France (University Press of France). [Google Scholar]

- Rujing Heshang Yulu 如淨和尚語錄 [Recorded Sayings of Master rujing]. n.d., In Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō 大正藏. Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司, vol. 48, no. 2002a.

- Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō 大正藏. 1983. Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司.

- Tan, Wei 譚惟. 2014. Lu fojiao de yingxianghua chuanbo 論佛教的影像化傳播——以濟公形象探析為個案 [On the visual communication of Buddhism: A case study of Jigong’s image]. Journal of Yunmeng 雲夢學刊 3: 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Van Overmeire, Ben. 2017. Reading Chan Encounter Dialogue during the Song Dynasty: The Record of Linji, the Lotus Sutra, and the Sinification of Buddhism. Buddhist-Christian Studies 37: 209–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Dexiu 汪德羞. 1989. Cong Gigongzhuan kan you minjian wenxue chengwei wenren zuopin de bianhua 從《濟公傳》看由民間文學成為文人作品的變化 [A study on the transformation from folk literature to literati works through Jigong Zhuan (Biography of Jigong)]. Journal of Ming-Qing Fiction Studies 明清小說研究 1: 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Mingqi 王敏琪. 2025. Sengsu hudong yu huayu jiaorong--yi mingqing shiqi Jigong xingxiang ji xushi wei zhongxin 僧俗互動與話語交融——以明清時期濟公形象及敘事為中心 [Monastic-lay interaction and discourse integration: Focusing on Jigong’s image and narration in the Ming and Qing Dynasties]. Chinese Language and Literature Research 漢語言文學研究 2: 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wu deng hu yuan 五燈會元 [Compendium of the Five Lamps]. n.d., In Zoku Dai Nihon Zokuzōkyō (卍续藏经). Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司, vol. 80, No. 1565.

- Wulin Xihu Gaoseng Shilue 武林西湖高僧事略 [Biographies of Eminent Monks at West Lake in Wulin]. n.d., In Zoku Dai Nihon Zokuzōkyō (卍续藏经). Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司, vol. 77, no. 1526.

- Xiang, Muzhong 向牡忠. 2013. Jidian yulu xiaokanji《濟顛語錄》校勘記 [A study on the collation of Jidian yulu (The Sayings of Ji Dian)]. Journal of Hunan First Normal University 湖南第一師範學院學報 4: 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Xu deng zheng tong 續燈正統 [Continuation of the Orthodox Lamp Records]. n.d., In Zoku Dai Nihon Zokuzōkyō (卍续藏经). Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司, vol. 84, No. 1582.

- Xu, Shangshu 許尚樞. 1990. Lishi shang de daoji yu yishu zhong de Jigong 歷史上的道濟與藝術中的濟公 [Dao Ji in History and Ji Gong in Art]. Southeast Culture 東南文化 6: 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Shangshu 許尚樞. 2012. Cong fomen linglei dao siyuan redian--Jigong yu fojiao guanxi de jinxi bianhua tanyin chanyi 从佛门另类到寺院热点——济公与佛教关系的今昔变化探因阐义 [From an Eccentric Monk to a Temple Sensation: Exploring the Causes and Meanings of the Changing Relationship Between Ji Gong and Buddhism Past and Present]. Journal of Taizhou University 台州學院學報 4: 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, Hisakazu 山口久和. 2004. 中国近世の批判思想 [Critical Thought in Early Modern China]. Tokyo 東京: Kenbun Shuppan 研文出版. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagida, Seizan 柳田圣山. 1985. 禅と狂 (Zen to Kyō). Tokyo 東京: Shunjūsha 春秋社. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Shiqi 杨士奇. 1937. Wenyuan Ge Shumu 文渊阁书目 [Catalogue of the Wenyuan Pavilion]. Beijing 北京: The Commercial Press 商务印书馆. [Google Scholar]

- Yun’an Heshang Yulu 運庵和尚語錄 [Recorded Sayings of Master yun’an]. n.d., In Zoku Dai Nihon Zokuzōkyō (卍续藏经). Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司, vol. 70, no. 1379.

- Zanning 贊寧. 1987. Song gaoseng zhuan 宋高僧傳 [Song Biographies of Eminent Monks]. Beijing 北京: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jinhui 張錦輝. 2020. Lun nansong Daoji chanshi shige de chanxue sixiang 論南宋道濟禪師詩歌的禪學思想 [On the Chan (Zen) thought in the poems of Chan Master Daoji in the Southern Song Dynasty]. Journal of North University of China (Social Science Edition) 中北大學學報 (社會科學版) 1: 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Ying 張穎, and Chen Su 陳速. 1993. cong Jidian Yulu dao sanhui longhuapudu shouyuan yanyi --miaoxie fopusa ticai zhanghui shuobu de yige fazhan lunkuo 從《濟顛語錄》到《三會龍華普度收圓演義》——描寫佛菩薩題材章回說部的一個發展輪廓. From Jidian Yulu to Sanhui Longhua Pudu Shouyuan Yanyi: An Outline of the Development of Chapter—Style Novels on the Theme of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. Henan Normal University Journal (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 河南師範大學學報 (哲學社會科學版) 4: 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Gang 朱剛. 2013. Song huaben qiantang huyin Jidian chanshi yulu kaolun 宋話本《錢塘湖隱濟顛禪師語錄》考論 [A study on the Song dynasty storyteller’s script Qiantang Lake Hermit Ji Dian Chan Master’s Quotations]. Journal of Southwest Minzu University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition) 西南民族大學學報 (人文社會科學版) 12: 183–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zokuzōkyō 卍续藏经 [Zoku Dai Nihon]. 1994. Taibei 臺北: xinwenfeng chuban youxian gongsi 新文丰出版有限公司.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).