Abstract

The Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra Dazhidu lun 大智度論 is often regarded as the “king of commentaries”; a total of 574 manuscript scrolls have been identified among the Dunhuang manuscripts, many of which constitute dispersed fragments that can be reassembled. In addition to comparing physical features such as format, handwriting style, and paper dimensions, the presence of shared textual variants serves as a key criterion for assessing their potential for reconstruction. Advances in the work of rejoining fragments provide a crucial foundation for further research. However, since the Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra is a commentary on the Mahāprajñāpāramitāśūstra and follows a format that first cites the sutra text and then provides an explanation, there is an overlap in content between the two types of texts. As a result, even after rejoining, 355 scrolls still cannot be definitively attributed to a specific source. Under such circumstances, shared textual variants become the key basis for reattributing these dubiously titled scrolls. Through an examination of three cases of rejoined scrolls exhibiting identical variants, along with three instances of scroll renaming, in this study, we demonstrate the crucial role of textual variant collation in the foundational research of Dunhuang manuscripts.

1. Introduction

The Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra (Great Treatise on the Perfection of Wisdom), composed by the ancient Indian master Nāgārjuna and translated into Chinese by Kumārajīva of the Later Qin dynasty, is a systematic commentary and exposition of the Mahāprajñāpāramitāśūtra Mohe Bore Boluomi Jing 摩訶般若波羅蜜經.1 Its contents span Buddhist doctrine, history, and other fields, and it preserves a wealth of folktales and legends once current in North India. Hailed as the “King among Treatises” and a “Buddhist encyclopedia,” it remains an indispensable source for the study of Mahāyāna Buddhism and ancient Indian culture.

As a commentary on the Mahāprajñāpāramitāśūtra, the Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra routinely reproduces the sūtra text before explicating it, so the two works overlap at the level of scriptural passages. Moreover, the Dunhuang manuscripts are predominantly fragmented, with over 400 fragments remaining unidentifiable as to whether they originate from the sūtra itself or the śāstra. Consequently, determining appropriate titles for manuscripts containing passages that appear in both the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra and the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Śāstra has become an urgent issue to resolve.

Whether it involves the analysis of textual versions, research in the field of linguistics, or explorations of doctrinal interpretations, all rely fundamentally on the reconstruction and accurate designating of early manuscripts. However, how to precisely assign titles to manuscripts whose content appears across multiple works, and how to rejoin fragments that cannot be seamlessly reassembled, remains a question worthy of deep consideration. Given that manuscripts were entirely reproduced through manual copying by scribes, variations inevitably exist across scriptures transcribed by different hands—and even within those copied by the same individual. It is precisely due to this inherent unpredictability in the copying process that the probability of identical variants appearing independently across different manuscript fragments is exceedingly low. After conducting a comprehensive comparison of manuscript versions of the two sūtras alongside numerous printed editions, we have collected over 9500 instances of textual variants. Utilizing these variants enables us to effectively determine relationships between manuscripts and printed editions, thereby laying a solid foundation for subsequent in-depth research.

2. Case Studies in Variant-Based Rejoining

Dunhuang manuscripts survive primarily as fragmented scrolls and disparate pieces. The physical and textual rejoining of these fragments is a fundamental philological practice that restores portions of the original documents, thereby providing a more complete basis for scholarly research.2 This process of reconstruction relies on a confluence of evidence, including: textual content; the physical contours of tear lines; the alignment of columns and layout; scribal hand and calligraphic style; and paper quality, size, and shape. A representative example is the successful rejoining of fragments designated BD11978 and BD1245.

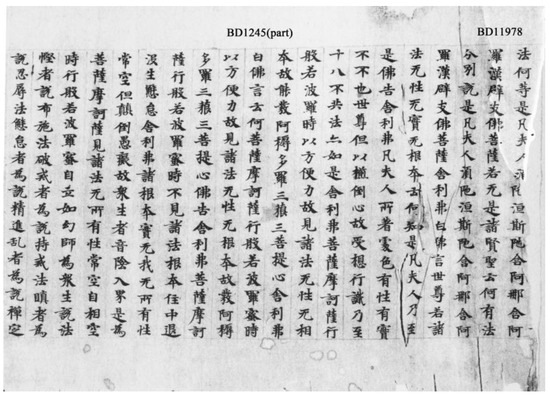

BD11978 + BD1245

(1) BD11978 (L2107), from Guotu (國圖) vol. 110, p. 182B.3 The fragment is incomplete on both the front and rear portions, with additional damage along the lower edge. As shown in the right portion of the Figure 1, two lines of text are preserved, each containing 6–8 characters. Ruling is visible. The original scroll did not bear a title; Guotu has tentatively identified the content as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 25.” According to the Guotu catalogue, the manuscript is written in regular script and dates to the Six Dynasties period (6th century CE).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the rejoining of BD11978 + BD1245.

(2) BD1245 (Bei 3467; Lie 45), from Guotu (國圖) vol. 18, pp. 311A–315B. The manuscript is in scroll format and comprises eight conjoined sheets. The beginning and end are missing. The front portion of the manuscript is shown on the left in the Figure 1 and preserves 213 lines of text, averaging approximately 17 characters per line, although the first 2 lines are partially damaged, containing only 1 to 10 characters, and the final line is incomplete, with merely 5 characters. Ruled lines are visible. The original scroll bears no title; the Guotu catalogue has tentatively identified it as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 91”. Palaeographic analysis in the catalogue attributes this manuscript to the Northern and Southern Dynasties period (6th century CE) and identifies the script as regular script.

These codicological and paleographic features provide strong evidence for their physical conjunction. After rejoining, the reconstructed portion begins with the remnant left dot of the character (zhu) “諸” in the phrase (Rushi wuxing zhufa) “如是無性諸法” [Thus, all dharmas are without inherent nature], and ends with the partial right stroke of (ti) “提” in the phrase (jin Xuputi ying zizhi) “今須菩提應自知” [Subhūti, you should now realize this for yourself]. The corresponding passage is located in the Taishō Tripiṭaka at T25, no. 1509, pp. 700a14–702b25.

The contents of these two manuscripts are consecutive and can be physically rejoined. As shown in the Figure 1, the first two lines of BD11978 and BD1245 connect seamlessly from left to right, with the edges at the join aligning perfectly. Six characters—(luo) “羅”, (han) “漢”, (pi) “辟”, (zhi) “支”, (fo) “佛”, and (pu) “菩”—that were originally split between the two fragments are now reintegrated into a continuous text. Moreover, the manuscripts share identical material and graphic features: they are of equal height, possess matching upper margins, and display clearly ruled lines with consistent line spacing. The calligraphic style is uniform, characterized by connected strokes, shortened verticals, distinct nà (捺) stroke tips, and pronounced dun (頓) pauses at the end of horizontal strokes. A comparison of common characters such as (fa) “法”, (he) “何”, and (shi) “是” further confirms that the handwriting is consistent, suggesting that they were copied by the same scribe.

Furthermore, a textual comparison confirms that BD11978 contains passages that are completely identical to both the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 25, and the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 91. However, since the text preserved in BD1245 includes commentary material, it can be definitively identified as a fragment of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 91. Given that these two fragments have now been successfully rejoined, BD11978 must also be re-designated as part of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 91.

Palaeographic analysis further indicates that the manuscript is written in a mature form of standard regular script (kaishu 楷書), which differs from the “clerical script” (lishu 隸書) or “clerical-regular script” (likai 隸楷) previously recorded in the National Library catalogue.

Based on the precise alignment of fractured edges and the successful rejoining of divided characters between BD11978 and BD1245, it can be conclusively determined that these two fragments constitute a single original manuscript. When comparing the preserved text of the fragments, it is often found that there are identical variant readings in some manuscripts that can be rejoined together.

For instance:

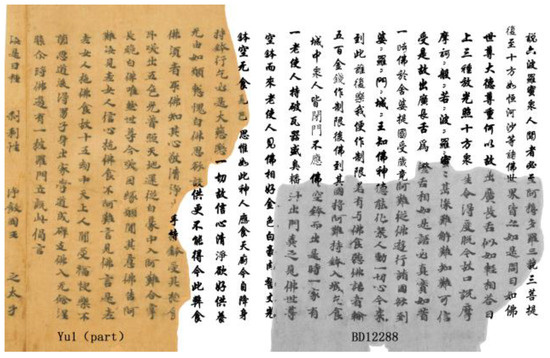

2.1. BD12288⋯Yu14

(1) BD12288 (L2417), from Guotu vol. 111 p. 16B. The fragment is incomplete on both the front and rear portions, with additional damage along the upper edge. As shown in the right portion of Figure 2, thirteen fragmentary lines of text are preserved, containing between 7 and 11 characters per line (the final line retains only remnant strokes of six characters on the right side). Ruling is visible. The script is clerical. The original scroll did not bear a title; Guotu has tentatively identified the content as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 8.” According to the Guotu catalogue, the manuscript dates to the Northern and Southern Dynasties period (5th–6th century CE).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the rejoining of BD12288 and Yu1.

(2) Yu(羽)1, from Miji(秘笈) vol. 1 pp. 1B–12A5. The manuscript is in scroll format and consists of twenty conjoined sheets. The front portion is damaged, while the rear remains intact. The front portion is as shown in the left portion of Figure 2 and preserves 436 lines of text, with each line containing between 3 and 20 characters. Ruled lines are visible. The script is Clerical. The end title reads “Mahāyāna Sūtra, juan 8 (《摩訶衍經》卷八).” The Miji (秘笈) catalogue tentatively identifies this content as Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 8, and provides a transcription of the colophon at the end of the scroll as follows: “On the fifteenth day of the eleventh month in the eighth year of the Great Unity era of the Great Wei Dynasty, the Buddhist disciple, wife of Deng Yan—Governor of Gua Province and Princess Changle of the Yuan family,6 reverently copied one hundred volumes of the Mahāyāna Sūtra. May the Emperor’s Majesty revive the nation’s fortune, and may all eight directions follow the rule.7 Also, may the disciple’s current husband, wife, children, family members, and the four great elements be healthy and free from disasters forever. In future lives, may all sentient beings universally attain perfect enlightenment together.” The colophon is followed by three vermilion seals: “Li Pang,” “Secret Collection of the Dunhuang Stone Chamber,” and “Li Shengduo and His Entire Family Devoutly Offer.”

The two manuscripts described above contain consecutive portions of text and can be physically rejoined. Although the fragments do not directly connect upon reconstruction, comparison with the complete canonical text indicates that three characters are missing between the remnant ink trace at the end of the last line of BD12288 and the first character at the beginning of Yu1. These missing characters have been restored based on the Taishō Tripiṭaka edition, as illustrated in Figure 2. After completing all damaged and omitted characters, each full line contains approximately 20 characters. Specifically, the surviving character (guang) “光” at the end of BD12288 aligns seamlessly with the missing sequence (bo kong wu) “鉢空無” at the start of Yu1.

Textual variants further support their physical conjunction: in instances where the Fangshan Stone Canon and the Taishō edition’s critical notes reference the “Sheng version” reading (zhongsheng) “衆生” [sentient beings], both fragments consistently use (zhongren) “衆人” [multitude of people]. Moreover, the character (qi) “棄” appears in its vulgar form (qi) “ ” in both manuscripts. These shared idiosyncrasies confirm that the two fragments once formed part of the same original scroll.

” in both manuscripts. These shared idiosyncrasies confirm that the two fragments once formed part of the same original scroll.

” in both manuscripts. These shared idiosyncrasies confirm that the two fragments once formed part of the same original scroll.

” in both manuscripts. These shared idiosyncrasies confirm that the two fragments once formed part of the same original scroll.Codicological and paleographic features also reinforce this connection: the fragments share identical lower margin height and exhibit uniform calligraphic style. Comparative analysis of common characters such as (qie) “切”, (da) “答”, (luo) “羅”, and (yuan) “緣” reveals consistent scribal habits—for example, the “土” radical is simplified as “十”, the “⺮” radical appears as “䒑”, and the “糹” radical is written in a connected cursive form as “纟”.

Upon rejoining, the reconstructed portion begins with the phrase (shuo liu boluomi) “説六波羅蜜” [expounding the six pāramitās] and concludes with the sutra tail title “Mahāyāna Sūtra, juan 8” (卷八). The corresponding passage is located in the Taishō Tripiṭaka at T25, pp. 115a7–121b13.

Moreover, as noted in Modern Chinese Scholars on Japanese Sinology, “The version of the Móhēyǎn jing preserved in Echoes of the Whistling Sand and housed in the Beiping Library is, in fact, Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra. Texts associated with the Three Stages School likewise frequently refer to this treatise as the Mahāyāna Sūtra (《摩訶衍經》), suggesting that this was a commonly used appellation during the Northern Dynasties period.” (Jia 2018). This assessment is remarkably astute.

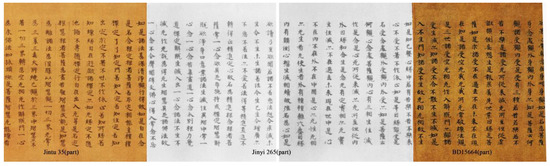

2.2. (BD15664 + Jinyi 265) + Jintu 35

(1) BD15664 (Jian 57862), from Guotu vol. 144, p. 136A. The fragment lacks its beginning, and its end has become detached. As shown in the right portion of Figure 3, eighteen lines of text are preserved, containing 12–17 characters per line; ruling is visible throughout. The surface of the scroll exhibits areas of damage with holes. The original scroll is untitled; the Guotu catalogue provisionally identifies it as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 19” (《大智度論》卷十九). Palaeographic analysis in the catalogue attributes the manuscript to the Northern and Southern Dynasties period (6th century CE) and describes the script as standard regular script.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the rejoining of (BD15664 + Jinyi 265) + Jintu 35.

(2) Jinyi 265, from Jinyi vol. 6, pp. 30–31B8. The manuscript takes the form of a scroll comprising three conjoined sheets; both the beginning and end of the scroll are missing. The front and rear portions are shown in the central section of Figure 3. A total of 60 lines of text are preserved on the manuscript, averaging 17 characters per line. Ruled lines are clearly visible. The original scroll is untitled; the Jinyi catalogue has provisionally identified it as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 19” (《大智度論》卷十九). The catalogue description attributes the manuscript to the Sui dynasty and identifies the script as regular script.

(3) Jintu 35, from Jintu 22–239. The fragment is missing both its beginning and end. As shown in the left portion of Figure 3, twenty lines of text are preserved, containing 17–18 characters per line; ruling is clearly visible. The original scroll is untitled; the Jintu catalogue provisionally identifies it as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 19” (《大智度論》卷十九) and attributes it to the Northern and Southern Dynasties period.

Material evidence further supports this reconstruction: the fractured edges of the two fragments align neatly, and their horizontal ruling lines match continuously. Additionally, the two manuscripts share identical formatting features—equal margin height, presence of ruled lines, consistent character density (approximately 17 characters per line), and comparable character size, character spacing, and line spacing. Palaeographic analysis also indicates a consistent calligraphic style, characterized by connected strokes, pronounced finishing tips on na (捺) strokes, and distinct pauses at the termination of horizontal strokes.

Despite the absence of perfectly interlocking divided characters along the fracture, the available evidence is insufficient to confirm their physical rejoining. The presence of identical idiosyncratic scribal variants—such as (ai) “礙” written as (ai) “㝵” and (ran) “染” written as (ran) “ ”—provides conclusive textual evidence for their common origin and confirms that the two fragments can indeed be rejoined. Following reconstruction, the combined text begins from the remnant left side of the character (guan) “觀” in the phrase “(Xunshen guan shishen, wuwo) 循身觀是身,無我” [Contemplating the body by following its nature, one realizes that this body is without self] and concludes with the character (zhong) “衆” in “(Zhi wuzui zhongsheng gen) 知無罪衆生根” [Knowing the faculties of beings who are without fault]. The corresponding passage is found in the Taishō Tripiṭaka at T25, no. 1509, pp. 203b28–204c17.

”—provides conclusive textual evidence for their common origin and confirms that the two fragments can indeed be rejoined. Following reconstruction, the combined text begins from the remnant left side of the character (guan) “觀” in the phrase “(Xunshen guan shishen, wuwo) 循身觀是身,無我” [Contemplating the body by following its nature, one realizes that this body is without self] and concludes with the character (zhong) “衆” in “(Zhi wuzui zhongsheng gen) 知無罪衆生根” [Knowing the faculties of beings who are without fault]. The corresponding passage is found in the Taishō Tripiṭaka at T25, no. 1509, pp. 203b28–204c17.

”—provides conclusive textual evidence for their common origin and confirms that the two fragments can indeed be rejoined. Following reconstruction, the combined text begins from the remnant left side of the character (guan) “觀” in the phrase “(Xunshen guan shishen, wuwo) 循身觀是身,無我” [Contemplating the body by following its nature, one realizes that this body is without self] and concludes with the character (zhong) “衆” in “(Zhi wuzui zhongsheng gen) 知無罪衆生根” [Knowing the faculties of beings who are without fault]. The corresponding passage is found in the Taishō Tripiṭaka at T25, no. 1509, pp. 203b28–204c17.

”—provides conclusive textual evidence for their common origin and confirms that the two fragments can indeed be rejoined. Following reconstruction, the combined text begins from the remnant left side of the character (guan) “觀” in the phrase “(Xunshen guan shishen, wuwo) 循身觀是身,無我” [Contemplating the body by following its nature, one realizes that this body is without self] and concludes with the character (zhong) “衆” in “(Zhi wuzui zhongsheng gen) 知無罪衆生根” [Knowing the faculties of beings who are without fault]. The corresponding passage is found in the Taishō Tripiṭaka at T25, no. 1509, pp. 203b28–204c17.Guo Xiaoyan has previously rejoined the first two manuscripts. It is now proposed that the latter two fragments—Jinyi 265 and Jintu 35—also contain consecutive textual content and are likely to be physically rejoined. As reconstructed in Figure 3 (note that due to the considerable length of Jinyi 265, only its initial and concluding sections are reproduced, with the central portion omitted for clarity), the final line of Jinyi 265, (Yixin nian, buling shengwen, Pizhifoxin deru, changnian buwang) “一心念,不令聲聞、辟支佛心得入,常念不忘” [Single-mindedly contemplate so that the minds of Śrāvakas and Pratyekabuddhas cannot enter, and constantly maintain this mindfulness without forgetfulness], connects seamlessly both textually and physically with the opening line of Jintu 35, (Rushi zhufa, shenshen qingjing, guanxing degu, de rushi zizainian) “如是諸法,甚深清淨,觀行得故,得如是自在念” [These dharmas are profoundly pure; through the practice of contemplative observation, one attains such autonomous mindfulness], with no characters missing between them.

Moreover, since the three fragments can be physically rejoined to form a continuous scroll, divergent assessments of their script type and dating are no longer tenable. Palaeographic analysis confirms that the hand is regular script with clear residual clerical elements. From a codicological perspective, the sheet is ruled for twenty lines containing approximately seventeen characters per line—a format characteristic of manuscript production during the late Northern and Southern Dynasties period.

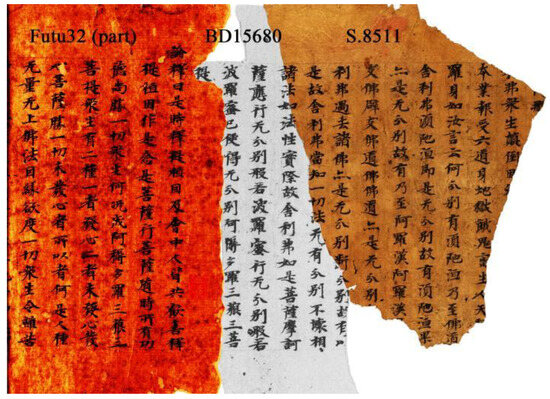

2.3. S.8511 + BD15680 + Futu32

(1) S.8511, from the International Dunhuang Project (IDP)10. The fragment is incomplete at both the beginning and end, with additional damage at the top and bottom edges. As shown in the right portion of Figure 4, ten fragmentary lines of text are preserved, containing between 3 and 17 characters per line. The script is regular script, executed between ruled lines. A red square seal—now largely illegible—is impressed in the upper margin. The original scroll is untitled; while no identification has been assigned in the IDP database, Fan (Fan 2018) has provisionally designated it as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 19” (《摩訶般若波羅蜜經》卷十九).

Figure 4.

Illustration of the rejoining of S.8511 + BD15680 + Futu32.

(2) BD15680 (Jian 57862), from Guotu vol. 144 p. 144A. The fragment is incomplete at both the beginning and the end. As shown in the central section of Figure 4, six lines of text are preserved, containing 1–17 characters per line; ruling is clearly visible. The original scroll is untitled; the Guotu catalogue has tentatively identified it as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 19” (《摩訶般若波羅蜜經》卷十九). Palaeographic analysis in the catalogue attributes the manuscript to the Northern and Southern Dynasties period (6th century CE) and identifies the script as regular script.

(3) Futu 32, from Futu pp. 309B–321A.11 The manuscript is in scroll format and comprises twelve conjoined sheets; it is incomplete at the beginning but intact at the end. The front part is shown in the left portion of Figure 4, preserving 314 lines of text and averaging approximately 17 characters per line. The script is regular script, executed between ruled lines. A largely illegible red square seal is impressed at the beginning of the scroll. The text includes a mid-scroll title reading “Chapter 65: Commentary on the Praising of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra” and a closing title “Commentary on the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 78”. The Futu catalogue provisionally identifies the manuscript as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 78”.

The first two fragments contain consecutive textual content and demonstrate a high probability of successful physical rejoining. As illustrated in the right portion of Figure 4, the last three lines of S.8511 connect seamlessly with the beginning of BD15680, with no textual lacunae. When aligned horizontally, the fractured edges show precise morphological continuity, and both horizontal and vertical rulings maintain perfect alignment. Furthermore, the fragments share identical codicological features: matching upper and lower margin heights, the presence of ruled lines, a consistent density of approximately 17 characters per line, and comparable character spacing and script size. Palaeographic analysis reveals a unified calligraphic style characterized by connected strokes, dense ink application, pronounced finishing tips on na (捺) strokes, and distinct dun (頓) pauses at the termination of horizontal strokes—all indicating production by the same hand. Critically, the nine characters (duan fen) “斷分”, (qie fa wu) “切法无”12, and (zhu fa ru fa) “諸法如法”, originally split between the two fragments, are now fully reintegrated. This combination of textual, physical, and palaeographic evidence conclusively establishes that these two fragments originated from a single manuscript that was subsequently torn apart.

Determining the feasibility of rejoining the latter two manuscripts presents greater complexity. First, the titles provisionally assigned to these manuscripts are inconsistent. Second, the closing line of BD15680—(Biande wufenbie anouduoluo sanmiao sanputi) “便得無分别阿耨多羅三藐三菩提” [Then one attains non-discriminatory anuttarā-samyak-saṃbodhi]—serves as the definitive concluding sentence of the 64th chapter of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra, making it difficult to ascertain whether any expository content originally followed thereafter.

A thorough comparison with the Buddhist canonical texts reveals that the first two fragments contain passages nearly identical to both Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 19 and Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 78. Their textual content is consecutive with that of the third fragment (Futu 32), with no missing characters between them, strongly suggesting their physical continuity. As shown in the left portion of Figure 4, BD15680 and Futu 32 align perfectly when rejoined: their fractured edges match closely, and both horizontal and vertical rulings maintain continuous alignment.

Furthermore, the three fragments share consistent codicological features—including matching formatting rules—and exhibit highly similar calligraphic style and handwriting characteristics. Crucially, they also contain identical variant forms of characters; for instance, (dian) “顛” is written as “(dian) 㒹”, “(tuo) “陀 as (tuo) “阤”, (ban) “般” as (ban) “ ”, (wu) “無” as (wu) “无”, (duan) “斷” as (duan) “断”, and (wudao) “五道” as (liudao) “六道”. This combination of textual, physical, and graphic evidence confirms that all three fragments originated from the same manuscript before being separated.

”, (wu) “無” as (wu) “无”, (duan) “斷” as (duan) “断”, and (wudao) “五道” as (liudao) “六道”. This combination of textual, physical, and graphic evidence confirms that all three fragments originated from the same manuscript before being separated.

”, (wu) “無” as (wu) “无”, (duan) “斷” as (duan) “断”, and (wudao) “五道” as (liudao) “六道”. This combination of textual, physical, and graphic evidence confirms that all three fragments originated from the same manuscript before being separated.

”, (wu) “無” as (wu) “无”, (duan) “斷” as (duan) “断”, and (wudao) “五道” as (liudao) “六道”. This combination of textual, physical, and graphic evidence confirms that all three fragments originated from the same manuscript before being separated.After rejoining, the reconstructed text begins from the lower remnant stroke of the character (a) “阿” in the phrase (Anahan) “阿那含” [Anāgāmin] and ends with the closing title “Commentary on the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 78”. The corresponding passage is located in the Taishō Tripiṭaka at T25, no. 1509, pp. 609b25–613b21.

Manuscripts are inherently unstable, and the prevalence of textual variants is one manifestation of this. Buddhist scriptures copied by different scribes, or even those copied by the same scribe, often exhibit various discrepancies. By identifying commonalities among these variations, we can establish connections between different manuscripts. In other words, the presence of textual variants is a normal characteristic of manuscripts. If several fragments share “identical variants” along with clearly matching external features—such as consistent paper, layout, and similar handwriting—even if they cannot be perfectly rejoined, as in the case of Figure 2, it can be determined that these fragments originally belonged to the same scroll before being separated. This low-probability “consistency,” emerging from the uniqueness and instability of manuscripts, can be described as “textual consistency.” It thus serves as crucial supporting evidence for determining relationships between manuscript fragments.

3. Case Studies in Variant Texts, Physical Rejoining, and Manuscript Designation

Since the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra is a commentary on the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, its format typically involves transcribing a portion of the sūtra text, followed by systematic exegesis and argumentation. This structural overlap results in shared sūtra passages across both works, making it difficult to determine whether a given fragment belongs to the sūtra proper or to the commentary. In such cases, physical rejoining of fragments often serves as the most accurate and effective method for manuscript identification. For example, as previously demonstrated, BD11978—which initially preserved only two fragmentary lines—could be conclusively re-designated as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 91” following its rejoining with BD1245.

In practice, however, the utility of rejoining is subject to significant limitations. First, the decision to rejoin fragments cannot rely solely on consecutive text, compatible format, or similar calligraphic style; it frequently requires supporting evidence from shared variant readings. The case of BD15680 and Futu 32 illustrates this well: although the sutra texts on these two fragments were initially attributed to different scriptures, and although their fracture alignment is only approximate rather than perfect, the presence of identical idiosyncratic scribal variants provided the necessary evidence to confirm their physical continuity.

Second, even when rejoining successfully identifies the general scriptural affiliation of a manuscript, the vast number of transmitted Buddhist textual traditions often makes it difficult to determine the specific edition, chapter, or fascicle from which it originates. Moreover, most manuscripts from the Dunhuang library cave are small fragments; even after rejoining, the text may remain too limited to permit secure identification. Some longer fragments may also lack original titles, and without knowledge of the content that may have followed, precise designation remains challenging.

In such contexts, we may adopt the “benchmark artefact” dating method used in bronze inscription studies by identifying Dunhuang manuscripts with clear titles and dates as “benchmark manuscripts.” By extensively collecting variant versions and analyzing the distinctive linguistic features of different editions, we can then compare these with manuscripts of uncertain attribution. If a questionable manuscript demonstrates high consistency with a benchmark manuscript—sharing identical patterns of omissions, redundant characters, errors, or non-standard forms—it can be determined that both manuscripts originated from the same source. Furthermore, if it can be demonstrated that certain errors in one manuscript were derived from another, this establishes a genetic relationship between the two manuscripts.13 (Guo et al. 1989).

3.1. Дх12229…Дх12281(3–1)

(1) Дх12229, from the Russian Collection vol. 16, p. 75A14. The fragment is missing its beginning and end, with additional damage along the lower portion. As shown in the right part of Figure 5, fourteen incomplete lines are preserved, containing 2–12 characters per line (only character fragments remain in the first line). The script is clerical script, executed between ruled lines. The original scroll is untitled; it remains unidentified in the Russian Collection, but the Catalogue of the Dunhuang Manuscripts in the Russian Collection (Tai 2019) provisionally designates it as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 8, Mie Zheng Pin 31” (《摩訶般若波羅蜜經》卷八·滅諍品第三十一).

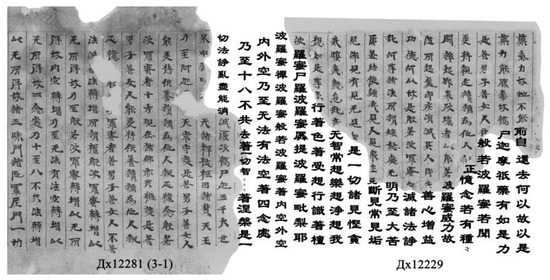

Figure 5.

Collation diagram of Дх12229…Дх12281 (3–1).

(2) Дх 12281(3–1), from the Russian Collection vol. 16, p. 75A. The fragment is missing its beginning and end, with damage also present on the lower edge. As shown in the left part of Figure 5, twenty-three lines of text are preserved, containing 3–16 characters per line. The script is clerical script, written between ruled lines. The original scroll is untitled; it remains unidentified in the Russian Collection, but the Catalogue of the Dunhuang Manuscripts in the Russian Collection (Tai 2019) provisionally designates it as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 56, Shi Mie Zheng Pin 30” (大智度論》卷五十六·釋滅諍品第三十).

A textual comparison with the Buddhist canon reveals that Дх12229 shares nearly identical phrasing with both Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 8 and Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 56, while Дх12281 (3–1) aligns closely with the received text of Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 56. Their contents are adjacent, suggesting potential physical continuity. As reconstructed in Figure 5, the two fragments do not connect directly; according to the complete text, approximately 52 characters across two lines are missing between them. Both fragments are ruled for approximately 16 characters per line and exhibit consistent handwriting and script style.

Critically, they also share identical variant character forms: (qin) “親” is written as (qin) “ ”, and characters derived from (ta) “它” are consistently rendered as (ye) “也”—e.g., (she) “蛇” appears as (she) “虵” in Дх12229, and (tuo) “陀” is written as (tuo) “虵” in Дх12281 (3–1). These idiosyncratic scribal practices confirm that the two fragments originated from the same manuscript.

”, and characters derived from (ta) “它” are consistently rendered as (ye) “也”—e.g., (she) “蛇” appears as (she) “虵” in Дх12229, and (tuo) “陀” is written as (tuo) “虵” in Дх12281 (3–1). These idiosyncratic scribal practices confirm that the two fragments originated from the same manuscript.

”, and characters derived from (ta) “它” are consistently rendered as (ye) “也”—e.g., (she) “蛇” appears as (she) “虵” in Дх12229, and (tuo) “陀” is written as (tuo) “虵” in Дх12281 (3–1). These idiosyncratic scribal practices confirm that the two fragments originated from the same manuscript.

”, and characters derived from (ta) “它” are consistently rendered as (ye) “也”—e.g., (she) “蛇” appears as (she) “虵” in Дх12229, and (tuo) “陀” is written as (tuo) “虵” in Дх12281 (3–1). These idiosyncratic scribal practices confirm that the two fragments originated from the same manuscript.Furthermore, since Дх12281 (3–1) can be securely identified as part of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, and the two fragments have been rejoined, Дх12229 must also belong to the same commentary. However, three variant readings distinguish this manuscript from received editions:

Line 4: The character (shi) “是” in the phrase (shi shannanzi) “是善男子” [this virtuous man] is present in the fragment and in many versions of the Śāstra, though the Taishō Tripiṭaka apparatus notes its absence in the Shengyu Canon version.

Line 5: (taren) “他人” [others] appears in the fragment, as well as in the Fangshan Stone Sutra (The Buddhist Association of China 中國佛教協會 and The China Buddhist Library and Museum 中國佛教圖書文物 1994) and Jinzang versions, and is cited in the Taishō apparatus (Yuan, Ming, and Shisan Temple editions); however, the Lizang and Taishō main text read only (ta) “他” [others].

Final line: (zantan) “讚歎” [to praise] is used in the fragment, as in the Fangshan version (The Buddhist Association of China 中國佛教協會 and The China Buddhist Library and Museum 中國佛教圖書文物 1994) and the Shisan Temple edition cited in the Taishō apparatus, whereas most other editions abbreviate to (zan) “讚” [to praise].

In summary, the textual variants in these fragments align most closely with the Fangshan Stone Sutra (The Buddhist Association of China 中國佛教協會 and The China Buddhist Library and Museum 中國佛教圖書文物 1994) and the Shisan Temple edition of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, indicating a common textual lineage. It is therefore appropriate to designate the rejoined manuscript as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 61”, corresponding to the passage found in the Fangshan Stone Sutras vol. 15, pp. 116a1–117b1.

3.2. BD9760 + S.8398

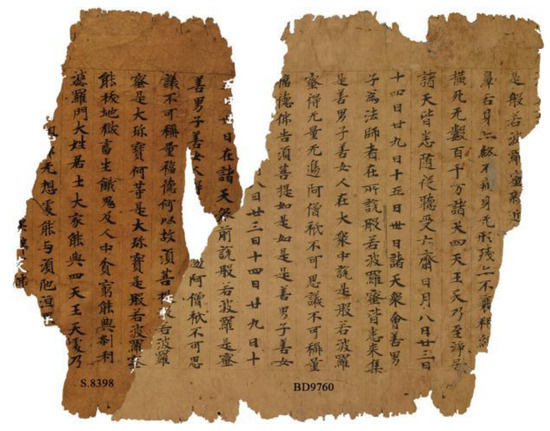

(1) BD9760 (Zuo 81), from Guotu vol. 106, p. 257A. The fragment is partially preserved; as shown in the right portion of Figure 6, this portion contains fifteen lines of text, each consisting of approximately 17 characters. The first three lines are incomplete at the bottom, and the last five are incomplete at the top. The script is regular script, executed between ruled lines. The original scroll is untitled; the National Library catalogue has tentatively identified it as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 12” and attributes it to the Northern and Southern Dynasties period (6th century CE).

Figure 6.

Illustration of the rejoining of BD9760 + S.8398.

(2) S.8398, from the International Dunhuang Project (IDP). As illustrated in the left portion of Figure 6, the fragment preserves eight lines containing 4–17 characters per line. The text is written in regular script between ruled lines. The scroll is untitled and remains unidentified in the IDP database.

A textual comparison with the Buddhist canon confirms that the two fragments contain passages essentially identical to both Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 12 and Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 65, and their contents are consecutive, permitting physical rejoining. As shown in Figure 6, the fragments align precisely along the fracture: the edges fit closely, and both vertical and horizontal rulings maintain continuous alignment. The four originally divided characters—(zhong) “衆”, (ti) “提”, (bo) “般”, and (mi) “蜜”—are now fully reintegrated.

Furthermore, the fragments share identical formatting (matching upper and lower margin height, ruled lines, and consistent line spacing, character density, and script size), a uniform calligraphic style (marked by distinct tips on na (捺) strokes and clear dun (頓) pauses at stroke terminals), and palaeographically consistent handwriting—as confirmed through comparison of common characters such as (shan) “善”, (shi) “是”, (bo) “般” and (re) “若”.

After rejoining, the reconstructed text begins with the character (shì) “是” in the phrase (shouchi shi bore boluomi) “受持是般若波羅蜜” [Uphold and preserve this perfection of wisdom] and ends with the fragmentary characters (guo, pizhi fo) “果,辟支佛” in the phrase (aluohan guo, pizhifo dao) “阿羅漢果、辟支佛道” [the fruit of Arhatship, the path of Pratyekabuddhahood]. Given that this passage appears in both the Sūtra and the Śāstra, the tentative title assigned in the Guotu catalogue (“Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 12”) may be inaccurate. A collation against major editions reveals three significant variant readings:

Line 1: (shannanzi wei fashi zhe) “善男子爲法師” [a virtuous man who becomes a Dharma master].

Sūtra: Matches BD14701, Shangtu (上圖) 87, and the Fangshan edition; all others read (shannanzi shannvren wei fashi zhe) “善男子善女人爲法師者” [virtuous men and virtuous women who become Dharma masters].

Śāstra: Matches the Goryeo Tripiṭaka, Vairocana Tripiṭaka, Fangshan, and Jin Tripiṭaka; only the Taishō edition reads (shannanzi shannvren wei fashi zhe) “善男子善女人爲法師者” [virtuous men and virtuous women who become Dharma masters].

Line 1: (bore boluomi) “般若波羅蜜” [prajñāpāramitā].

Sūtra: All editions read (bore boluomi chu) “般若波羅蜜處” [the locus of prajñāpāramitā].

Śāstra: Matches the Goryeo Tripiṭaka, Vairocana Tripiṭaka, and the Song/Yuan/Ming editions cited in the Taishō apparatus; the Fangshan, Jin, and Taishō main text read (bore boluomi chu) “般若波羅蜜處” [the locus of prajñāpāramitā].

Line 6: the character (shuo) “説” in the sentence (zhu tianzhong qian shuo) “諸天衆前説” [speak before the assembly of devas].

Sūtra: All editions read (shuo shi) “説是”.

Śāstra: Matches all editions except the Taishō, which reads (shuo shi) “説是”.

The variant profile of the rejoined fragments aligns most closely with the Goryeo Tripiṭaka and Vairocana Tripiṭaka versions of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, suggesting a common textual lineage. It is therefore appropriate to re-identify the manuscript as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 65: Shi wuzuo shixiang pin” (釋無作實相品) [Chapter on Explaining Non-Action and True Reality]. The corresponding passage is located in the Taishō Tripiṭaka at T25, no. 1509, pp. 515a8–26.

3.3. S.11870 + S.1379

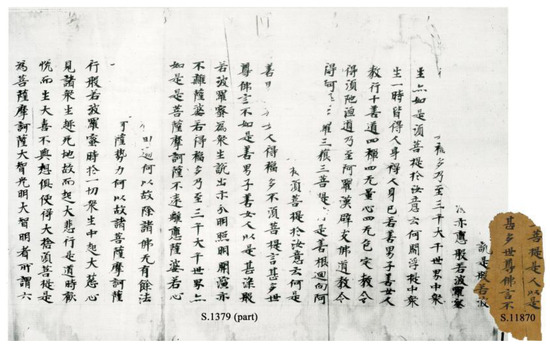

(1) S.11870, from the International Dunhuang Project (IDP). As shown in the lower right portion of Figure 7, the fragment preserves three partial lines of text, with 5–7 characters retained in the lower portion of each line. The script is regular script, executed between ruled lines. The original scroll is untitled and remains unidentified in the IDP database.

Figure 7.

Illustration of the rejoining of S.11870 + S.1379.

(2) S.1379, from Yingtu (英圖) vol. 21, pp. 240A–241B. The manuscript is in scroll format, consisting of three conjoined sheets, and is damaged at both the beginning and end. The front portion of the manuscript is shown in the left portion of Figure 7. It preserves fifty-five lines containing 6–18 characters per line; the first line is partially damaged, with only the left portions of its final 4 characters visible. The text is written in regular script between ruled lines. The original scroll is untitled. The British Library has catalogued it as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 18”; the New Index to the Dunhuang Manuscripts concurs with this identification, while Dunhuang Baozang tentatively identifies it as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 43”. The British Library catalogue attributes the manuscript to the Northern and Southern Dynasties period (6th century CE).

A textual comparison with the Buddhist canon confirms that the two fragments contain passages essentially identical to both Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 18 and Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 77. Their contents are consecutive, permitting physical rejoining. As shown in Figure 7, the fragments align precisely along the fracture, with the edges fitting seamlessly. The five characters (shuo shi bore bo) “説是般若波”, originally divided between the two manuscripts, are now almost fully restored.

Furthermore, the fragments share identical formatting: the margin height appears consistent, both contain ruled lines and exhibit similar line spacing, character density, and script size. Palaeographic analysis also indicates uniform handwriting and style, as evidenced by common characters such as (pu) “菩”, (ti) “提”, and (ren) “人”.

After rejoining, the reconstructed text begins with the three characters following the phrase (chi shi shangen huixiang anouduoluo sanmiao sanputi) “持是善根,迴向阿耨多羅三藐三菩提” [Dedicate these roots of virtue to Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi] and concludes with the seven characters following (ruoshi zhufa jie buxing bore boluomi) “若是諸法皆不行,般若波羅蜜” [if all these dharmas do not practice prajñāpāramitā]. Collation against major editions reveals six significant variant readings:

Line 14, the phrase (shuo chushi) “説出示” [to explain and demonstrate] is found in most versions of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, except the 30-juan version of the Fangshan Edition is not available for comparison, and the Jin Edition and Taisho Tripitaka versions of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra read (shuo xianshi) “説顕示” [To state and demonstrate]. However, the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra manuscript S.3673, as well as the Goryeo Edition, Chongning Edition, Fangshan Edition, and Jin Edition, all read (shuo chushi) 説出示 [to explain and demonstrate], but the Taisho Tripitaka collation note cites the Shengyu Zang version, which reads (shuo xianshi) “説顕示” [To state and demonstrate].

Line 25, the term (wochuang) “卧床” [bed] in the phrase (yifu、yin shi、wochuang、jiyao) “衣服、飲食、卧床、疾藥……” [clothing, food, bedding, medicine…] aligns with most Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra versions. This reading is also supported by the śāstra manuscript S.3673 and the Goryeo, Chongning, and Jin Editions of the śāstra. However, the Fangshan Edition and certain versions cited in the Taishō Tripiṭaka commentary read (woju chuangfu) “卧具床敷” [bedding and spreadings].

Line 26, the phrase (neng bi bao shizhu zhi en) “能畢報施主之恩” [able to fully repay the benefactor’s kindness] is consistent with the sūtra versions BD14018, the 40-juan Fangshan Edition, and the Taishō Tripiṭaka apparatus citation of the Shengyu Zang. The 30-juan Fangshan Edition is illegible here; other sūtra versions read (bi) “必” [must] instead of (bi) “毕” [fully]. Most the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra versions agree with the fragment, except the Sheng Edition reads (neng bi bao shizhu zhi si) “能畢報施主之思” [can fully repay the kindness of the benefactor] likely a scribal error where (si) “思” [thought] was written for (en) “恩”, [kindness].

Line 30, the phrase (ying changxing bore boluomi, xing...) “應常行般若波羅蜜,行……” [should constantly practice prajñāpāramitā, practice…] matches the sūtra versions BD14018, the 40-juan Fangshan Edition, and the Yuan, Ming, and Sheng versions cited in the Taishō apparatus. Conversely, the Chongning, Jin, Goryeo, and Taishō base text versions of the sūtra read (ying changxing bore boluomi, changxing) “應常行般若波羅蜜,常行……” [should constantly practice prajñāpāramitā, constantly practice…]. For the śāstra, manuscript S.3673 and the Goryeo, Chongning, Fangshan, Jin, and Taishō base text versions agree with the fragment. The Taishō apparatus, however, notes that the Shengyu Zang and Shisanji Temple commentary versions read (yingdang xing bore boluomi, xing) “應當行般若波羅蜜,行……” [ought to practice prajñāpāramitā, practice…].

In line 37, the character (wang) “忘” [to forget] in (wang ci dabao) “忘此大寶” [forget this great treasure] agrees with the Jin Edition, the re-engraved Goryeo Edition, and the Taishō Tripiṭaka version of the sūtra. Other sūtra versions, including BD14018, the Chongning Edition, the 40-juan Fangshan Edition, and the Song, Yuan, and Ming versions cited in the Taishō apparatus, read (wang) “亡” [to lose]. For the śāstra, manuscript S.3673 and the Taishō citation of the Shengben agree with the fragment using (wang) “忘” [to forget]. The Taishō base text of the śāstra reads (wangshi) “亡失” [to lose], while the Goryeo, Chongning, Jin, Fangshan Editions, and the Song/Yuan/Ming versions cited in its apparatus read “亡”, and the and version reads (wangshi) “忘失” [oblivion].

In line 40, the phrase (xing zikong) “性自空” [nature is empty by itself] is consistent with most Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra versions, though the Taishō apparatus citation of the Shengyu Zang reads (zixing kong) “自性空” [inherent nature is empty]. All consulted versions of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra agree with the fragment in reading (zixing kong) “性自空” [inherent nature is empty].

The variant profile aligns most closely with S.3673 and other Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra witnesses, indicating a common textual origin. It is therefore appropriate to re-identify the rejoined manuscript as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 77: Shi Meng Zhong Buzheng Pin, Part 61” (釋夢中不證品第六十一) [Chapter 61: On Interpreting Dreams within the Assembly during the Orthodox Dharma Period]. The corresponding passage is located in the Taishō Tripiṭaka at T25, no. 1509, pp. 599b5–600a19. The British Library’s provisional title (“Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, juan 18”) is inaccurate.

4. The Basic Value of Textual Comparison

Traditionally, the primary method for designating unidentified fragments or scrolls has relied on textual comparison with canonical Buddhist scriptures. Major collections, including those held by the National Library of China, the British Library, the Russian collections, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France, as well as scattered individual manuscripts, have been systematically designated by comparing their preserved texts against the Taishō Tripiṭaka. For large-scale manuscript identification, this approach remains the most efficient and widely applicable.

Nevertheless, several significant limitations have emerged:

First, when a fragment’s content closely parallels or duplicates multiple Buddhist texts, sole reliance on the Taishō Tripiṭaka makes precise designation impossible.

Second, many manuscripts survive only as fragments or incomplete scrolls, often lacking sufficient textual material for meaningful comparison.

Third, Buddhist scriptures circulated in multiple versions through tradition due to centuries of copying and printing. Simply matching texts to the Taishō Tripiṭaka and adopting its fascicle and chapter titles may yield inaccurate attributions. For example, the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra survives in three major version systems: the 27-fascicle, 30-fascicle, and 40-fascicle recensions. Since the Taishō edition follows the 27-fascicle version, manuscripts compared exclusively against it would be misidentified as belonging to that recension, even if they originally formed part of another textual tradition.

Therefore, when the visible content of a fragment or scroll is insufficient to support a definitive conclusion, physical rejoining emerges as the preferred and most reliable methodological approach. The value of rejoining is demonstrated in three primary aspects:

First, it significantly enhances the completeness of Dunhuang manuscripts, allowing for the maximal reconstruction of the original scrolls. For instance, S.13171 is a fragment preserving only three incomplete lines with a total of seven characters. Similarly, BD10227, BD11714, BD10758, BD11070, BD9666, and BD7658 are all fragments lacking both beginning and end. Through comparative analysis, these seven fragments were identified as originally belonging to Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 30.15 Their rejoining has substantially restored the original textual sequence.

Second, rejoining provides a solid basis for the accurate identification or correction of scroll titles. For example, S.9215 is an untitled fragment, while S.4960—though incomplete at the beginning—has a complete end bearing the title “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 43”. After rejoining, the partially damaged characters (ming wei) “名为” from both fragments were fully integrated, confirming that they originated from the same scroll. Consequently, S.9215 should be re-identified as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 43” in accordance with S.4960.

Third, rejoining can clarify manuscript attributes and facilitate precise dating and scribal identification. BD12288, for instance, is an originally untitled fragment tentatively catalogued by the National Library as “Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, juan 8”. Palaeographic analysis, however, revealed that it was copied by the same scribe responsible for Yu(羽)1. Yu1, though incomplete at the beginning, has an intact end titled “Mahāyāna-sūtra, juan 8”, followed by a colophon: “Copied reverently on the fifteenth day of the eleventh month of the eighth year of the Dàtǒng era of the Northern Wei Dynasty by the Buddhist disciple Deng Yan, Governor of Guazhou, and his wife Princess Changle, Yuan [shi], one hundred copies of the Mahāyāna-sūtra. May the Emperor’s reign flourish and the eight directions know harmony; may the disciples, their spouses, children, and household remain free from calamity; and may all sentient beings ultimately attain Buddhahood.” The scroll also bears three red seals: “Li Pang”, “Dunhuang Grottoes Secret Collection”, and “Offering of Li Shengduo and His Family”. This evidence confirms that BD12288 was also produced by Princess Changle, Yuan shi, on the same documented date.

Rejoining constitutes a fundamental preliminary task in Dunhuang manuscript studies and serves as a critical prerequisite for subsequent research. Nevertheless, two significant challenges persist:

First, the determination of whether fragments can indeed be rejoined remains methodologically complex. Although the primary criteria for rejoining include (1) consecutive textual content, (2) perfectly aligned fracture edges, (3) characters that can be physically reintegrated, (4) identical layout and formatting, and (5) consistent handwriting and style, practical experience shows that not all rejoined fragments exhibit perfectly interlocking characters or fractures. In the absence of such clear physical matches, the presence of continuous text and palaeographic similarity can only suggest—not confirm—the possibility of rejoining.

Second, since the Mogao Grottoes functioned as a storage and restoration site for Buddhist scriptures under the supervision of Dao Zhen, the vast majority of surviving materials are fragmentary or incomplete scrolls. Consequently, even successfully rejoined scrolls may remain partial, and the limited textual length and scarcity of contextual information often impede the extraction of meaningful data regarding their origin and affiliation.

In this context, the analysis of textual variants offers a powerful complementary approach. Owing to the inherent unpredictability and individuality of manuscript production, even when the same scribe copies the same text, inconsistencies in character usage inevitably arise. Therefore, the presence of low-probability agreements—specifically, the occurrence of identical idiosyncratic variant characters across different fragments or scrolls—can establish meaningful connections not only between individual manuscripts but also between manuscripts and received editions.

4.1. Determining Whether Rejoining Is Possible

For example, with the fragments “S.8511 + BD15680 + Futu32,” the seams of the first two scrolls fit together seamlessly, and the nine characters (duan fen) “斷分”, (qie fa wu) “切法无” and (zhu fa ru fa) “諸法如法”, originally belonging to two scrolls can all be combined into one, which naturally indicates that they can be rejoined. However, between the last two fragments, no matching characters that can be perfectly combined are found, and the cracks do not fit perfectly either. Yet, all three scrolls share the same variants, such as “(dian)” 顛 all written as (dian) “㒹”, (tuo) “陀” all written as (tuo) “阤”, (wu) “無” all written as (wu) “无”, (bo) “般” all written as (bo) “ ”, (duan) “斷” all written as (duan) “断” and (wudao) “五道” all written as (liudao) “六道” This proves that these three fragments are indeed torn from the same scroll.

”, (duan) “斷” all written as (duan) “断” and (wudao) “五道” all written as (liudao) “六道” This proves that these three fragments are indeed torn from the same scroll.

”, (duan) “斷” all written as (duan) “断” and (wudao) “五道” all written as (liudao) “六道” This proves that these three fragments are indeed torn from the same scroll.

”, (duan) “斷” all written as (duan) “断” and (wudao) “五道” all written as (liudao) “六道” This proves that these three fragments are indeed torn from the same scroll.4.2. Maximizing the Designation or Correction of the Designation of Scrolls

In cases where the content of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra and the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra overlap, it can be challenging to determine whether a reconstructed fragment belongs to the sūtra text itself or to a cited passage within the śāstra—especially if the preserved portion precedes the exegetical section. Textual criticism based on variant readings can help establish whether such fragments originate from the same source as other scrolls or extant editions, thereby enabling more accurate attribution of scrolls with ambiguous origins.

For example, S.835 is a fragment lacking both beginning and end, containing 35 lines. No joinable fragments have been identified, and it remains unclear whether the original scroll included exegetical content after the preserved portion, making its classification difficult. The British Library’s tentative identification as “juan 13 of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra” should be reconsidered.

Through comparative analysis of variant readings across editions of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra and the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, three distinctive variants were identified in S.835. These align specifically with the Jin Edition and the Pilu Edition of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra, indicating a common source. Accordingly, the fragment can be more accurately identified as part of “juan 67 of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra: Shi Tan Xinxing Pin Zhiyu pin 45” (釋歎信行品第四十五之餘) [Remaining Part of Chapter 45: Commentary on the Chapter of Admiring Faithful Conduct]”, following the attribution of those editions.

4.3. Determining the System to Which the Scroll Belongs

Due to differences in translators and the base texts used by copyists during transcription, the same literature may have different translations and editions. For example, the Sanskrit text of the Twenty-five Thousand Verses Prajñāpāramitā has three Chinese translations: the Fangguang Prajñāpāramitā-sūtra, translated by Mokṣala (無羅叉), the Guangzan Prajñāpāramitā-sūtra translated by Dharmarakṣa (竺法護), and the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra translated by Kumarajiva (鳩摩羅什). Similarly, the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra also has different versions, such as the 27-juan version, the 30-juan version, and the 40-juan version. The differences between these translations and editions sometimes only involve a few words or characters, making it very difficult to determine the system to which a single fragment belongs. Textual comparison of variants is one of the bases for this. For example, BD14777(2) is a fragment with an incomplete beginning but a complete end, preserving 36 lines. The original scroll had no title, and the National Library tentatively titled it “juan 3 of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra.”

After textual comparison of variants, it was found that the preserved scriptures are highly consistent with Ganbo8 and S.4067,16 indicating that they are from the same source. Therefore, the tentative title by the National Library is incorrect. Ganbo28 and S.4067 both retain the original title “juan 4 of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra,” which should be the content of juan 4 of the 40-juan version, matching the 40-juan version of the Fangshan Stone Scriptures. Thus, BD14777(2) also comes from the 40-juan version. The tentative title “Volume 3 of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra” by the National Library was likely misled by the 27-juan version of the Taisho Tripitaka.

4.4. Determining the Scribal Relationships of the Scroll

Determining the scribal relationships between manuscripts is a fundamental task in manuscript studies. The examples above, which demonstrate “shared omissions, shared additions, shared errors, and shared non-standard forms” between manuscripts, indicate their common origin. Building on this foundation, if the errors in Manuscript A can be demonstrated to have originated from those in Manuscript B, it establishes their scribal relationship: the exemplar used for A was either B itself or a direct copy of B. For instance, in the phrase (Congzuzhiding zhouza baopi) “從足至頂周匝薄皮” [From the soles of the feet to the crown of the head, the entire body is covered with a thin layer of skin] the character (za) “匝” is consistently written as (za) “匝” across various editions, with the exception of BD14454 and the Chongning Canon edition. BD14454 records it as (za) “ ”, while the Chongning Canon edition writes it as (za) “

”, while the Chongning Canon edition writes it as (za) “ ”. The character “

”. The character “ ” is an archaic form of “

” is an archaic form of “ ”, and the two are graphically similar.

”, and the two are graphically similar.

”, while the Chongning Canon edition writes it as (za) “

”, while the Chongning Canon edition writes it as (za) “ ”. The character “

”. The character “ ” is an archaic form of “

” is an archaic form of “ ”, and the two are graphically similar.

”, and the two are graphically similar.Another example is the phrase (Shenzhong you famao zhao chi) “身中有髮毛爪齒” [Within the body there are hair, body-hair, paws and teeth], where the character (zhao) “爪” [paw] is uniformly written as (zhao) “爪” [paw] in other editions, yet only BD14454 and the Chongning Canon edition diverge: BD14454 writes it as (zhua) “抓” [to grab], while the Chongning Canon edition records it as (zhe) “折” [to break] also a case of graphical similarity leading to scribal error.

Therefore, it can be concluded that either BD14454 itself or a copy derived from BD14454 served as the source for the Chongning Canon edition.

4.5. Clarifying the Copying Date of the Scroll

Most Dunhuang manuscripts are incomplete at the beginning and end, and there are few manuscripts with explicit dates. In addition to judging the copying date through paper, layout, and rejoining, textual variants are also an effective method. For example, the S.55 manuscript is described in the British Library catalogue as “a 5th–6th century Northern and Southern Dynasties manuscript in clerical script, with discrepancies in chapter names compared to the Taisho Tripitaka.” Upon examination of the original manuscript, the characters are in regular script, with some strokes showing clerical script influence. There are also many textual variants (variant character forms) commonly seen in manuscripts from the Sui Dynasty and around, such as (se) “色” all written as (se) “ ”, (na) “那” all written as (na) “

”, (na) “那” all written as (na) “ ”, (nao) “惱” all written as (nao) “

”, (nao) “惱” all written as (nao) “ ”, (nao) “

”, (nao) “ ”, (nao) “

”, (nao) “ ”, (shou) “受” all written as (shou) “

”, (shou) “受” all written as (shou) “ ”, (sa) “卅” all written as (sa) “

”, (sa) “卅” all written as (sa) “ ”, and (miao) “藐” all written as (miao) “

”, and (miao) “藐” all written as (miao) “ ”, which can be dated to the late 6th century. The British Library’s determination of it as a 5th–6th century Northern and Southern Dynasties manuscript in clerical script is slightly too early.

”, which can be dated to the late 6th century. The British Library’s determination of it as a 5th–6th century Northern and Southern Dynasties manuscript in clerical script is slightly too early.

”, (na) “那” all written as (na) “

”, (na) “那” all written as (na) “ ”, (nao) “惱” all written as (nao) “

”, (nao) “惱” all written as (nao) “ ”, (nao) “

”, (nao) “ ”, (nao) “

”, (nao) “ ”, (shou) “受” all written as (shou) “

”, (shou) “受” all written as (shou) “ ”, (sa) “卅” all written as (sa) “

”, (sa) “卅” all written as (sa) “ ”, and (miao) “藐” all written as (miao) “

”, and (miao) “藐” all written as (miao) “ ”, which can be dated to the late 6th century. The British Library’s determination of it as a 5th–6th century Northern and Southern Dynasties manuscript in clerical script is slightly too early.

”, which can be dated to the late 6th century. The British Library’s determination of it as a 5th–6th century Northern and Southern Dynasties manuscript in clerical script is slightly too early.In summary, textual comparison of variants is an effective means for basic research on manuscripts. With the assistance of rejoining, it can provide us with more complete manuscripts, help us extract more effective textual variants, and make more accurate and detailed judgments. For example, as mentioned above in Section 3.3 “S.11870 + S.1379,” after joining these two fragments together, it is still impossible to determine whether they come from the Mahāprajnāpāramitā-śāstra or the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra. However, the patched-up manuscript can provide more effective textual information: after comparing variants with various versions of the Mahāprajnāpāramitā-śāstra and the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra, six main textual variants were found. According to the analysis of these variants, the preserved scriptures of S.11870 + S.1379 are completely consistent with those of S.3673, indicating that they are from the same source. Therefore, it is appropriate to denominate it as “Volume 77 of the Mahāprajnāpāramitā-śāstra, Commentary on the Chapter of Shi Meng zhong Bu zheng, Part 61,” following the latter.

5. Conclusions

In summary, while the reconstruction of fragments cannot resolve all challenges related to manuscript attribution, it offers a more accurate and reliable approach than titling based solely on content analysis. Through physical reconstruction, the completeness of manuscript scrolls can be enhanced, allowing for the extraction of more meaningful textual variants. By employing textual variant comparison alongside principles such as “textual consistency” and “consistent patterns of errors,” this method not only provides solid evidence for determining whether fragments can be rejoined, but can also be extended to the conjectural joining of non-adjacent fragments—maximizing the reconstruction of scattered manuscripts. Furthermore, it enables more precise identification of manuscript titles and dates, along with the inference of scribal relationships and textual genealogies. Ultimately, it plays a crucial role in foundational research on both handwritten and printed texts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing—original draft, L.F.; writing—review and editing, H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Research Program (No.24NDJC233YBM) and National Social Science Fund of China (No. 20VJXT01, 21BYY142).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Due to the absence of the original Sanskrit text and a Tibetan translation, the authorship of the Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra has long been a subject of debate, with several main theories emerging. Firstly, scholars such as Kato Junshō and Étienne Lamotte argued that the text was not composed by Nāgārjuna Bodhisattva. Kato (1988) proposed that it was a collaborative work between Kumārajīva and a scholar who had travelled to the Western Regions, while Lamotte suggested it was written by a scholar from Northwest India. Secondly, Akira Hirakawa and Ryūshō Hikata maintained that the text was originally authored by Nāgārjuna but later substantially edited or adapted by Kumārajīva. Meanwhile, Wang Rutong accepted partial Nāgārjuna authorship while acknowledging that certain sections remain questionable. Thirdly, Yinshun (Shi 2004) firmly defended the traditional attribution to Nāgārjuna and systematically refuted the arguments of the aforementioned four scholars. Here, we tentatively adopt the traditional view. After systematic reconstruction and identification, a comprehensive comparison with the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra might reveal relevant clues. The Mahāprajñāpāramitāśūtra, also composed by the master Nāgārjuna and translated by Kumārajīva, is a foundational work of Mahāyāna Buddhist thought. Its emergence expanded the influence of Prajñā and Mādhyamaka philosophy, and significantly advanced the development of Chinese Buddhist translations. |

| 2 | Rejoining is a crucial technique for the reconstruction of ancient texts, primarily applied in the fields of unearthed documents and archeology, such as with oracle bones, bamboo and wooden slips, and Dunhuang manuscripts. Monk Dao Zhen can be considered an early representative of those who practiced the rejoining of manuscript scrolls (Zhang et al. 2021). Nowadays, scholars such as Fang Guangchang (Fang 2013), Imre Galambos (Galambos 2016), Ikeda On (Yamamoto et al. 1978–1987), and Zhang Yongquan (Zhang 2021; Zhang and Zhang 2025), have all conducted in-depth research on this subject. |

| 3 | “BD” refers to manuscripts in the Dunhuang collections of the National Library of China, published in the series Dunhuang Manuscripts in the National Library of China (Ren 2012). “BD” is the conventional abbreviation for this series. |

| 4 | This set of rejoined fragments is derived from pages 201–203 of Liting Fan’s (Fan 2022) doctoral dissertation from Zhejiang University, with the rejoining conducted in 2021. Both Ding Yuan’s report titled “On the Authenticity of Manuscripts in the Xingyu Shuwu Collection” (presented at the “Dunhuang Manuscript Forgeries and Current Research on the Silk Road” symposium on 19 March 2022) and the article by Zhang Yongquan and Zhou Simin, “A New Investigation into the Causes of Fragmentation in Li Shengduo’s Previously Collected Dunhuang Manuscripts” (published in Dunhuang Research, Issue 6, 2022), mention this set of rejoined fragments—a remarkable coincidence. However, the purposes and bases for the rejoining differ from those in this study. The latter two works do not involve discussions on the role of variant textual comparisons. |

| 5 | “Yu” refers to the “Dunhuang Manuscripts: The Secret Collection” facsimile of the Dunhuang documents held by the Konan Kinen Library in Japan, catalogued under Ōtani Hō’s “Yu” (羽) numbering system. |

| 6 | The character (shi) “氏” is missing in the original text. The Biography of Shen Hui of the Northern Zhou (北周·申徽傳) records that Deng Yan was the son-in-law of Prince Dongyang Yuan Rong. |

| 7 | The character (fang) “方” was mistakenly recorded as (wan) “万” in the Miji catalogue. |

| 8 | “Jinyi” refers to manuscripts in the Dunhuang collections of the Tianjin Art Museum, published in the series Dunhuang Manuscripts in the Tianjin Art Museum Collection (Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House 上海古籍出版社 and Tianjin Art Museum 天津市藝術博物館 1996–1998). “Jinyi” is the conventional abbreviation for this series. |

| 9 | “Jintu” refers to manuscripts in the Dunhuang collections of the Tianjin Library, published in the series Dunhuang Manuscripts in the Tianjin Library Collection (Beijing: Xueyuan Press, 2019). “Jintu” is the conventional abbreviation for this series. |

| 10 | “S.” designates manuscripts in the Stein collection of the British Library, with reference to the microfilm edition, Dunhuang Baozang (Taipei: Wenhua Publishing Company, 1981–1986), and the printed catalogue Dunhuang Manuscripts in the British Library (Guangxi Normal University Press, 2011). IDP refers to the International Dunhuang Project. |

| 11 | “Futu” refers to manuscripts in the Dunhuang collections of the Fu Ssu-nien Library, Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, published in the series Dunhuang Manuscripts in the Fu Ssu-nien Library (Fang 2013). “Futu” is the conventional abbreviation for this series. |

| 12 | Since the manuscript uses the simplified Chinese character “無”, the vulgar variant is retained here for intuitive representation. The same applies to the following instances. |

| 13 | Guo et al. (1989) first proposed the method of determining titles through collating textual variants in their article “An Example of Improper Selection of Base Texts in the Dunhuang Bianwen Ji: With Collation Notes on Two Vimalakīrti Sutra Transformation Texts.” |

| 14 | “Дх” designates manuscripts in the Dunhuang collections of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, Russian Academy of Sciences, published in the series Dunhuang Manuscripts in Russian Collections (Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, 1992–2001). “Russian Collection” is the conventional abbreviation for this series. |

| 15 | Liu Xian has successfully rejoined the latter six fragments; for details, see A Study of the Dunhuang Manuscript of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra (Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, 2011). |

| 16 | “Ganbo” refers to the Dunhuang manuscript numbers in the Dunhuang Manuscripts in Gansu Collections (published by Gansu People’s Publishing House in 1999, abbreviated as “Gancang”). |

References

- Fan, Liting 范麗婷. 2018. Mohe Bore Jing yu Da Zhidu Lun Yiwen Bijiao Yanjiu《摩訶般若經》與《大智度論》異文比較研究 [A Study of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra from the Chinese Dunhuang Manuscripts]. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Zhejiang University (浙江大學博士論文), Hangzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Liting 范麗婷. 2022. Dunhuang Hanwen Xieben <Mohe Bore Boluomi Jing> Yanjiu 敦煌漢文寫本《摩訶般若波羅蜜經》研究 [A Study of the Dunhuang Chinese Manuscript of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā]. Master’s thesis, Zhejiang Normal University (浙江師範大學碩士論文), Jinhua, China. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Guangchang 方廣錩, ed. 2013. “Zhongyang Yanjiuyuan” Lishi Yuyansuo Fu Siyan Tushuguan Cang Dunhuang Yishu “中央研究院”歷史語言所傅斯年圖書館藏敦煌遺書 [Dunhuang manuscript numbers in the Dun.huang Manuscripts in the Fu Ssu-nien Library of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica]. Taipei: Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica “中央研究院”歷史語言所. [Google Scholar]

- Galambos, Imre. 2016. Composite Manuscripts in Medieval China: The Case of Scroll P.3720 from Dunhuang. In One-Volume Libraries: Composite and Multiple-Text Manuscripts. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 355–78. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Zaiyi 郭在貽, Yongquan Zhang 張涌泉, and Huang Zheng 黃征. 1989. <Dunhuang Bianwen Ji> diben xuanze budang zhi yi li: Fu liangzhong <WeimojieJing JiangJingwen> jiào yì 《敦煌變文集》底本選擇不當之一例——附兩種《維摩詰經講經文》校議 [An Example of Improper Selection of Base Texts in the Dunhuang Bianwen Ji: With Collation Notes on Two Vimalakīrti Sutra Transformation Texts]. Beijing: National Ancient Books Collation and Publishing House 全國古籍整理出版公司. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Jingjing 賈菁菁, ed. 2018. Modern Chinese Scholars on Japanese Sinologyb近代中國學者論日本漢學 [Modern Chinese Scholars on Japanese Sinology]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House 上海古籍出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, Jyunsho. 1988. The world of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-upadeśa (Dazhidu lun). In Observations on Truth. Translated by Hong Yin. Taipei: Ti Kuan Cultural Enterprise Company., Limited. 諦觀文化事業有限公司. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Jiyu 任繼愈, ed. 2012. Guojia Tushuguan Cang Dunhuang Yishu 國家圖書館藏敦煌遺書 [Dunhuang Manuscripts in the National Library of China]. Beijing: Beijing Library Press 北京圖書出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House 上海古籍出版社, and Tianjin Art Museum 天津市藝術博物館, eds. 1996–1998. Tianjin Shi Yishu Bowuguan Cang Dunhuang Wenxian 天津市藝術博物館藏敦煌文獻 [Dunhuang Manuscripts in the Collection of Tianjin Art Museum]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House 上海古籍出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Yinshun 释印順, ed. 2004. Da Zhidu Lun Biji 《大智度論》筆記 [Notes on the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-upadeśa]. Hsinchu: Fu Yan Buddhist Institute 福嚴佛學院. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, Huili 邰惠莉, ed. 2019. E Cang Dunhuang Wenxian Xulu 俄藏敦煌文獻敘録 [Catalogue of Dunhuang Manuscripts in Russian Collections]. Lanzhou: Gansu Education Publishing House 甘肅教育出版社. [Google Scholar]

- The Buddhist Association of China 中國佛教協會, and The China Buddhist Library and Museum 中國佛教圖書文物, eds. 1994. Fangshan Shijing 房山石經 [Fangshan Stone Sutras]. Beijing: Huaxia Publishing House 華夏出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Tatsuro 山本達郎, Ikeda On 池田温, and Okano Makoto 岡野誠, eds. 1978–1987. Tonkō Torufan shakai keizaishi shiryō (敦煌吐魯番社會經濟史史料) [Tun-huang and Turfan Documents concerning Social and Economic History]. Tokyo: Tōyō Bunko (Tōyō Bunko Tonkō Bunken Kenkyūkai). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yongquan 張涌泉. 2021. Zhuihe yu Dunhuang Canjuan de Dingming-Dunhuang Canjuan Zhuihe de Yiyi Zhiyi 綴合與敦煌殘卷的定名——敦煌殘卷綴合的意義之一 [Reconstruction and Designation of Dunhuang Fragments: One Significance of Fragment Rejoining]. Wenxian 文獻 [The Documentation] 1: 103–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yongquan 張涌泉, and Lei Zhang 張磊. 2025. Pinjie SIlu de Wenming:Dunhuang Canjuan Zhuihe Yanjiu 拼接絲路的文明——敦煌殘卷綴合研究 [Piecing Together the Silk Road: Manuscript Fragments from Dunhuang]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yongquan 張涌泉, Mujun Luo 羅慕君, and Ruoxi Zhu 朱若溪. 2021. Dunhuang Cangjingdong zhi Mi Fafu 敦煌藏經洞之謎發覆 [Unlocking the Dunhuang Library Cave Mystery]. Zhongguo Shehui Kexue 中國社會科學 [Social Sciences in China] 3: 180–203+208. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).