Abstract

The weather imagery of the nickname “Sons of Thunder” (Mark 3:17) for James the Greater and his brother John the Evangelist, conflating the noise of thunder with the sound of the heavenly voice, invited vivid analogies—vocal, natural, and supernatural—in interpretations of this biblical passage and its liturgical adaptation. Yet, although James and John were both venerated in the medieval Western liturgy as thunderous witnesses to the Gospel, their voices were heard differently. Comparative analysis of medieval liturgical music and readings for St James the Greater, particularly at the pilgrimage site of Santiago de Compostela, and St John the Evangelist across the medieval West reveals how thunder imagery was voiced by the clergy to promote the apostolic mission of St James and to highlight the visionary sublimity of St John. These largely overlooked examples demonstrate more broadly how the sonic environment of the natural world influenced the performance and perception of divinely-inspired voices in Christian worship.

1. Introduction

Among the inner three of the twelve disciples, James the Greater and his brother John the Evangelist were nicknamed by Christ as “The Sons of Thunder” (Mark 3:17)—an unexplained appellation that generated numerous legends. Some imagined that they were hot-tempered, while others speculated that James and John spoke loudly, and others still associated their preaching with the weather.1 Rain might symbolize a downpour of divine grace, and thunder, the boom of the heavenly voice. This latter interpretation—identifying James and John as thunderous witnesses of the Gospel—resounded in the music and readings of the medieval Western liturgy alongside other vivid analogies, both natural and supernatural.

The sonic identity of James and John as the “voice of thunder” (vox tonitrui) in late medieval liturgical observances for each of the two saints invites comparative analysis. In liturgical music for both saints, the vox tonitrui is frequently articulated in conjunction with Gospel speech—the quotation of passages from one of the four New Testament Gospels. Music and sermons for the feasts of the Vigil and Passion of St James explicitly compare the thunderous voices of the two apostles, while chants for the principal feast of St John the Evangelist interpret his thunder as a sign of his visionary exceptionalism. Despite the shared tempestuous association of their Biblical names, the thunderous voices of James and John were thus perceived and performed differently. Yet how exactly did these liturgical adaptations of the same natural metaphor signal saintly difference? And in what ways did the sound of the vox tonitrui vary in liturgical performance?

Recent scholarship on natural imagery in early Christian spirituality and medieval hagiography has emphasized the importance of metaphor—at once a window into perceptions of the world, both natural and supernatural; and a symbol of potential connections between the human and the divine. Approaching hagiography from the perspective of environmental history, Ellon Arnold has urged medievalists across the humanities to investigate more profoundly the use and religious significance of a single natural metaphor to represent contrasting phenomena, such as sin and salvation.2 Liturgical invocations of the thunder of both James and John as simultaneously destructive and salvific provide a prime example of this duality, with considerable potential for interpretation. Moreover, the representation of thunder as a communicative medium between the heavenly and human realms is emphasized by Erica Loic in her textual and image-based study of early Christian and medieval conceptions of God as the thunderer (Loic 2019, pp. 405–7). Noting at once that the thunderer represents an “explicitly vocal conception of God,” which could be channeled by the celebrant,3 Loic observes the call-and-response dynamic of prayer and other human vocalizing with divine thunder, sometimes transmitted through an apostolic or prophetic messenger.4 The vocal veneration of James and John as the “voice of thunder” presents an exceptional opportunity to explore the liturgical dynamics of human-divine communication, both in the textual content of the music and readings and through liturgical sound.

The identification of the thunder of James and John specifically as a voice highlights its liminal position between human and non-human—a vocal dynamic observed more broadly in sound-centered studies of medieval culture.5 Significantly, in the chants for James and John, the thunderous vox becomes at once the subject and substance of its performance. This vocal convergence is especially intense in situations where the verbs tonare and intonare (both meaning to thunder) conflate the natural sound of the apostles’ thunder with the musical sound of the singers’ voices.

Inspired by these dynamic studies of natural imagery and voice, my comparative analysis of medieval liturgical music and readings for St James the Greater and St John the Evangelist examines intersections between the sonic qualities of thunder and varied types of vocal performance. I argue that the liturgical voicing of thunder imagery by the clergy aimed to promote the apostolic mission of St James, particularly in his veneration at the pilgrimage site of Santiago de Compostela, and to highlight the visionary sublimity of St John among religious communities across the medieval West. Biblical and hagiographic narratives, as interpreted in biblical exegesis and liturgical commentary, provide the interpretive framework for understanding the language and symbolism of the liturgical texts. Musical settings of these texts in a variety of chant genres—particularly responsories (sung in response to readings) for the Office and sequences (sung just prior to the Gospel) for the Mass—showcase a wide range of expressive devices to emphasize key words and their vocal performance. My concluding consideration of the singing of these chants in conjunction with the intonation of the Gospel foregrounds the liturgical context in which Gospel speech was vocalized and heard. Through these examples, my study aims at once to draw attention to the largely overlooked liturgical vocality of thunder imagery and to demonstrate more broadly how the sonic environment of the natural world influenced the performance and perception of divinely-inspired voices in Christian worship.

2. Sons of Thunder: Biblical and Hagiographic Narratives

According to the Gospel of Mark, when Christ ascended a mountain where he chose his twelve disciples, he renamed the brothers James and John Boanerges—“The Sons of Thunder” (3:17). Modern interpretations of this designation note the use of names, in Jewish tradition, to confer a specific duty, in this case identifying James and John as potential witnesses of the thunderous heavenly voice (Culpepper 1994, pp. 39–40). Yet what is the broader biblical context for this association between stormy weather and divine speech? And how did this biblical analogy influence legends of the two saints? Through a synthesis of the most prevalent depictions of thunder in the bible and in relevant hagiographic sources, common patterns emerge that provide a narrative basis for interpreting the imagery of late medieval liturgical music for James and John. Across these various traditions, the fearsome sound of thunder provides a medium for divine communication.

Both the Old and New Testaments associate thunder with divine speech, as noted by medieval commentators (Loic 2019, p. 413)6. Throughout the bible, the power of the thunderous voice is terrifying, particularly when accompanied by other natural phenomena such as lightning and earthquakes. Prior to the dictation of the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai, for example, God appears to Moses amidst thunder, lightning, clouds, and a loud trumpet, filling the Israelites with fear (Exodus 19:16). More widespread effects of the divine thunderstorm are especially vivid in Psalm 76, in which the believer cries out to God and meditates on God’s omnipotence: “Great was the noise of the waters; the clouds sent forth their voice, for thy arrows pass, the voice of thy thunder in a wheel. Thy lightnings enlightened the world; the earth shook and trembled” (Psalm 76: 18–19).7 In the influential Expositions of the Psalms, the Church Father St Augustine (354–430) considers the vocal emission of the clouds, asking “What clouds are we to understand here?” to which he responds, “Among all nations ‘the clouds sent forth their voice’ for it was by preaching Christ that the clouds gave utterance.”8 Interpreting the next verse locating the voice of thunder in a wheel, Augustine explains, “Those clouds we heard about rolled around the whole round world; they circled it, thundering and flashing their lightning. … They thundered their teaching and coruscated [i.e., sparkled] with miracles, for their sound went forth throughout the world” (Augustine of Hippo 2002, p. 87). Augustine thus equates the circular trajectory of the thunderer’s voice with the evangelizing mission and the spread of Christianity. As we shall observe in liturgical worship, the thunderstorm imagery of Psalm 76 and its interpretation became associated specifically with the preaching missions of James and John. Indeed, St John the Evangelist himself noted that perceptions of the thunderous voice might vary according to the spiritual state of the listeners. Responding to Christ’s plea to God, “Father, glorify thy name” the fourth Gospel states, “A voice therefore came from heaven: ‘I have both glorified it and will glorify it again.’ The multitude therefore, that stood and heard, said that it thundered. Others said, ‘An angel spoke to him’” (John 12:28–9). Commenting on this passage, another Church Father St John Chrysostom (347–407) explains, “Some merely detected the sound, while others knew that the voice was articulate, but they did not yet comprehend what it meant” (John Chrysostom 2000b, p. 230). Thus the Evangelist explicitly recognizes that divine thunder could be simultaneously heard as a natural noise and as a form of supernatural communication.

The New Testament designation of James and John as Boanerges became a key source for subsequent biblical associations and hagiographic narratives in the cult of St James. As we will observe in greater detail in the Jacobean liturgy, the apostle’s reception of his special name alongside John and Peter on a mountaintop is compared to the privilege of witnessing the Transfiguration of Christ on Mount Tabor (Matthew 17:1–13, Mark 9:2–13, Luke 9:28–36). The three apostles become fearful when the mountain is covered by a cloud, from which a voice proclaims, “This is my beloved Son; hear him” (Luke 9:35). Although there is no reference to thunder, the fear-inducing voice from the cloud shares notable parallels with the aforementioned stormy associations of the divine voice and calls to preach. Indeed, the preaching voice of James is described with exceptional sonic force in the widely known Golden Legend compiled by the Dominican friar Jacobus de Voragine (ca. 1230–98), who explains that St James the Greater is called the Son of Thunder because of “the thunderous sound of his preaching, which terrified the wicked, roused up the sluggish, and by its depth attracted the admiration of all” (Jacobus de Voragine 1993, vol. 2, p. 3). Voragine further emphasizes the sheer volume of James’s voice by quoting the Venerable Bede (672/3–735): “‘He spoke so loudly that if he thundered but a little more loudly, the whole world would not have been able to contain him’.”9 On the verge of sonic excess, the apostle’s preaching voice has the power to terrify unbelievers, motivate procrastinators, and impress all listeners.

By contrast, biblically-derived thunder imagery in the cult of St John the Evangelist is more varied. In the Golden Legend, Voragine overlooks the thunder of the Evangelist’s voice altogether in favor of a more tranquil scene, stating “When Saint John was about to write his gospel … [and] retired to the remote place where he was to write the divine book, he prayed that he might not be disturbed at his work by wind or rain; and even today the elements maintain the same reverence for the spot” (Jacobus de Voragine 1993, vol. 1, p. 55). Other accounts, however, are more dramatic. Among them is a fifth-century narrative of John’s ministry, the Acts of John attributed to Prochorus, that circulated widely in Byzantium but was also known in some parts of the later medieval West, including the dioceses of Metz and Liège.10 In this story, John is accompanied in his ministry on the island of Patmos by his disciple, Prochorus, whom he leads to a deserted mountain to pray for God’s assistance. As John is about to narrate his Gospel, the mountain shakes with thunder and lightning and Prochorus falls to the ground. John revives him, and after asking him to sit on his right side, John proclaims “In the beginning was the Word” and dictates the rest of his Gospel.11 Medieval and modern scholars alike have recognized parallels between this account of the Evangelist’s reception of the Gospel on Patmos and Moses’s reception of the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai, especially evident in the forceful effects of thunder (Exodus 19:16–18), thereby juxtaposing the Old Law of Moses with the New Law of John (Boxall 2013, pp. 111–12; and Ševcenko 2013, p. 6). Moreover, for Christians of the medieval West, Patmos was more commonly associated with the site of what was believed to be John’s vision of the Apocalypse. Indeed, throughout this prophetic text, John’s vision of the throne of God features lightning, voices, and thundering (Revelation 4:5, 8:5, 16:18) frequently accompanied by the sound of trumpets, while John hears the heavenly voice “as the voice of great thunder” (Revelation 14:7). These thundery associations of John’s evangelical voice and prophetic vision provided a vivid soundscape for the convergence of John’s preaching and prophetic identities in liturgical worship.

Studying the depiction of thunder in Late Antique and medieval Christianity, Loic observes: “The auditory characteristics of thunder also made it appropriate to settings where music, oratory, and other ritual sounds were recurrent” (Loic 2019, p. 420). Moreover, Loic notes the resemblance of the Latin verb tonare (meaning to thunder, or to speak in thunderous tones) and the noun tonus (meaning a sound or tone; Loic 2019, p. 406), as explained in a tenth-century gloss on the Ars grammatica by Donatus stating “tonos come from tonando, ‘thundering,’ as if in singing or for the purpose of song” (Atkinson 2003, p. 202; 2009, p. 52). These vocal associations thus prompt the question: How were James and John linked to thunder in late medieval liturgical music and how did singers give resonance to their thunderous voices?

3. Apostolic Thunder in Music and Sermons for St James

Although St James the Greater was venerated by Christian communities throughout the medieval West, the most extensive compilation of music and readings for his liturgical feasts is preserved in the Liber sancti Iacobi, transmitted in the Codex Calixtinus,12 prepared in the twelfth century (between 1139 and 1172) for the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in present-day Spain.13 There the shrine housing the apostle’s bodily remains, brought by his disciplines to Galicia where James was believed to have preached the Gospel, became a major pilgrimage site. As a “monument” to the cathedral’s patron saint (Fuller 2001, p. 183), the Liber sancti Iacobi—consisting of five books—contains a diverse assortment of texts and music: sermons, liturgical chant, liturgical rubrics, miracle stories, an account of the translation of the apostle’s relics from Jerusalem to Galicia, a chronicle of Charlemagne’s legendary exploits in Spain, a pilgrim’s guide, and supplementary materials including music for multiple voices (i.e., polyphony). The compilation of the Liber sancti Iacobi appears to have been motivated by several interrelated contemporaneous factors: the suppression of the ancient Visigothic rite in Compostela in favor of the Franco-Roman liturgy, thereby displacing the liturgical observance of the Passion of St James from 30 December to 25 July; the disciplinary reform of the Compostelan clergy; and the construction of a new cathedral building and promotion of the shrine at Santiago de Compostela as equal in status to pilgrimage sites in Rome and Jerusalem.14 As specified in the prefatory letter attributed to Pope Calixtus,15 of prime concern is the authority and authenticity of the texts—particularly those of the liturgy—as a corrective to former reliance on apocryphal tales and non-Jacobean chants for martyrs, confessors, or other saints such as John the Baptist and Nicholas (Coffey and Dunn 2021, pp. 6–7). Prioritizing texts from the bible and the Church Fathers, the letter instructs that “whatever is sung for Saint James must be of great authority” (Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. 9), for the benefit of the Compostelan clergy and visiting pilgrims. As we shall presently observe in the music and sermons for St James, biblical references to the apostle’s thunder enhance his apostolic status as an extraordinarily vociferous and powerful preacher.

In the Liber sancti Iacobi, the most concentrated liturgical emphasis on the Gospel passage narrating the renaming of James and John as “Sons of Thunder” occurs on the Vigil of St James (24 July). Singers give musical voice to the thunder of James and John in a variety of chants sung at services during the night and day. As shown in Table 1, thunder references on the Vigil occur primarily in the Office chants of Matins (during the night), with two responsories, and especially at Lauds (at daybreak), with six antiphons, leaving only one chant for the Mass (around 2pm, as specified in the rubric) sung prior to the reading of the Gospel from Mark 3:13–19. Recurring quotes from this Gospel passage take two principal forms.16 Most frequent is the Ihesus vocavit text, in which Christ calls James and John “Boanerges” (Mark 3:17). An alternative is the Redemptor imposuit text, which includes the preceding verse (Mark 3:16) in which Christ renames Simon as Peter, thereby verbally distinguishing the three favored disciplines. Both textual forms might combine in the same chant, exemplified at Matins in the first responsory Redemptor imposuit Simoni with the verse Ascendens Ihesus, or they might appear in close succession, as heard at Lauds in the first two antiphons Imposuit Ihesus Simoni and Vocavit Ihesus Iacobum.

Table 1.

Vigil of St James (24 July), principal chants referencing the Sons of Thunder. Latin texts are in E-SC, Codex Calixtinus, fols. 102r-3r, 114v. All translations are from (Coffey and Dunn 2021, pp. 323–27, 364). Abbreviations: A (antiphon), Ab (Benedictus antiphon), L (Lauds), M (Matins), R (responsory).

Yet other biblical references intermingle with the Gospel quote to amplify and even differentiate the thunderous voices of James and John. On the Vigil, the second responsory of Matins and third antiphon of Lauds share the same allusion to the earthquake caused by the thunderstorm in Psalm 76:19, as interpreted in the sermon Celebritatis sacratissime for the Passion of St James (25 July) attributed in the Liber sancti Iacobi to Pope Calixtus.17 The sermon embellishes the name “Sons of Thunder,” paraphrasing Mark 3:13 and 17, with the following assertion: “For just as the sounds of thunder echo on earth and cause it to tremble, so also the whole world resounded and trembled with their voices” (Coffey and Dunn 2021, pp. 76–77). The thunderous voices of the two apostles reverberate throughout the world with such force that they cause an earthquake. This statement concludes by associating these thunderous voices specifically with preaching, paraphrasing Mark 16:20: “When they preached everywhere with the Lord working with them and confirming their word with accompanying signs” (Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. 77, mistakenly identified as Matthew 16:20). In this context, the earthquake accompanying the apostles’ thunderous voices might be understood as a divinely-inspired sign validating the authority of their preaching. At Lauds, the preaching analogy becomes explicit in the fourth antiphon Recte Filii Tonitrui, in which the Sons of Thunder are differentiated by the heavenly sound of John’s Gospel speech, quoting the distinctive opening phrase “In the beginning was the Word” (John 1:1). This biblical connection derives from the compilation sermon Festivitatem electionis attributed in the Liber sancti Iacobi to St Jerome, St Augustine, St Gregory, and Pope Calixtus for the Octave of the feast of the Translation of St James, observed at Compostela on 5 January.18 The section from Jerome alludes to Psalm 76:19 to describe the worldwide resonance of the apostles’ preaching immediately before explaining the following:

Jerome thus equates the theological singularity of the most distinctive passage from John’s Gospel with the extent of John’s thunder, testing the limits of human comprehension. Yet Jerome quickly returns to the worthiness of both apostles in the next sentence, paraphrased in the fifth Lauds antiphon Iacobus et Iohannes tonitruum, referencing the Transfiguration: “But both were worthy to be led up to Mount Tabor by the Lord and to perceive the terrific sound from the cloud at one point: ‘This is My beloved Son. Listen to Him’” [Luke 9:35] (Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. 307). In the antiphon, the sound or voice from the cloud is identified specifically as thunder. This reference to the Transfiguration, also witnessed by Peter, emphasizes the inclusion of James and John among the three favored disciplines heard previously at Lauds in the first antiphon Imposuit Ihesus Simoni. As a series, the lauds antiphons are particularly rich in biblical and homiletic references that underscore the sonic dimension of the apostles’ perception of divinity and divinely-inspired preaching.And they are fittingly called “Sons of Thunder.” One of them called out and from the heavens thundered the theological utterance that no one previously had known how to express: “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and God was the Word.” [John 1:1] He left this utterance, which is so deep and weighty so that if one ever wanted to thunder more, the world could not grasp it.(Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. 307)

Although the first two responsories of Matins and first three antiphons of Lauds feature similar texts and imagery, the contrasting musical styles of these chants would have created greater variety in performance.19 The Lauds antiphons of the Vigil are relatively brief and declamatory in comparison to the Matins responsories, with melismas (flourishes of several notes on a single syllable) that musically prolong and embellish key words. Significantly, the longest melismas in both responsories, Redemptor imposuit Simoni and Vocavit Ihesus Iacobum, fall on “Boanerges” and “Tonitrui.” Moreover, the placement of these melismatic words maximizes their prominence resulting from the following form: respond (initially intoned by a soloist, continuing with the full choir)—verse (solo)—repetendum (choral response of the second half of the respond). In Redemptor imposuit Simoni, for example, the melisma on “Boanerges” occurs at the end of the respond, which is repeated in the repetendum at the end of the verse. The same repetition scheme applies to the melisma on “Tonitrui” in Vocavit Ihesus Iacobum. These stylistic and formal characteristics thus combine to musically highlight the apostles’ thunder. As we shall presently observe, the thunderous voices of James and John receive even more musical attention in the liturgy for the following day.

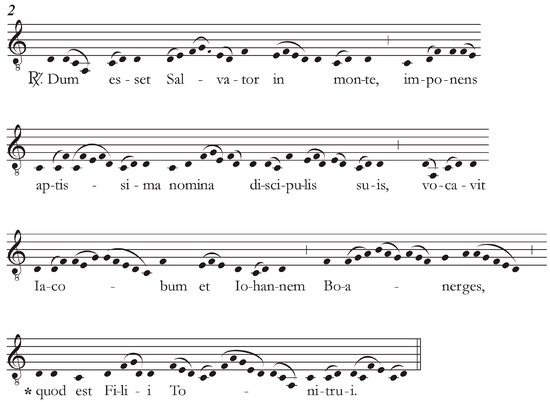

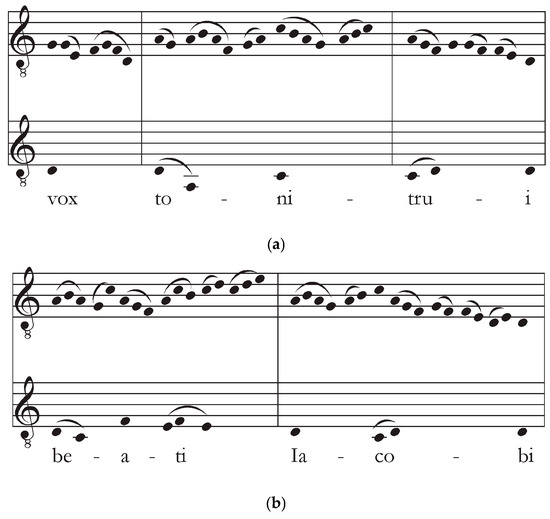

On the feast of the Passion of St James (25 July), the Ihesus vocavit text (quoting Mark 3:17) predominates in a few isolated chants of the Office and with greater frequency in those of the Mass (see Table 2). Passing references to the Boanerges in the hymn Felix per omnes for First Vespers and the sequence Gratulemur et letemur, sung immediately prior to the Gospel reading at Mass are paired with the scene of the Transfiguration. Musically, the most elaborate chants are the Matins responsory Dum esset Salvator and the Mass offertory Ascendens Ihesus in montem, both of which combine the Gospel quote with thunder imagery from Psalm 76. The rubric for the responsory Dum esset Salvator identifies Jerome’s contribution to the aforementioned compilation sermon Festivitatem electionis (for the Translation on 5 January) as a textual source,20 and indeed the verse Sicut enim vox tonitrui derives from the following passage, in which Jerome combines imagery from Psalm 76:19, Psalm 18:5, and Romans 10:18: “According to the Gospel of Mark they were called ‘Boanerges’ or ‘Sons of Thunder’ by the Lord, because ‘each sounds like the voice of thunder on the wheel of the world’ [Psalm 76:19] and thus their sound went to the ends of the entire earth, and their words went forth to the ends of the world [Psalm 18:5 and Romans 10:18] (Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. 307). Inspired by the orbicular trajectory and worldwide resonance of the apostles’ thunderous voices, the responsory verse prioritizes the preaching voice of St James. This Jacobean emphasis of the verse text is anticipated by the respond melody (shown in Figure 1), in which a twelve-note melisma on the name “Iacobum” overshadows the perfunctory declamation of “Iohannem.”21 Although the subsequent melismatic treatment of “Boanerges” and especially “Tonitrui” at the end of the respond—repeated after the verse—follows a similar strategy to the aforementioned responsories of the Vigil, these melismas in Dum esset Salvator are more virtuosic due to their length and extended melodic range. The seventeen-note melisma on “Boanerges” ascends to the highest pitch (b) of the entire chant, followed by a twenty-two-note melisma on “Tonitrui” that spans the range of a full octave (from high a to low A). Descending scalar passages of five to six notes in these three melismas further connect “Iacobum” to his thundery names “Boanerges” and “Tonitrui” and distinguish these passages from the rest of the melody. Moreover, the polyphonic appendix to the Liber sancti Iacobi in the Codex Calixtinus includes a two-voice setting of the solo sections of Dum esset Salvator, attributed to Master Ato, Bishop of Trier.22 The lengthy melismas of the choral respond are omitted, but the seven notes of “vox tonitrui” in the verse, quoted in the lower voice, are embellished with thirty-one notes in the upper voice (shown in Figure 2a). Similarly, the verse’s sonic emphasis on the preaching of St James culminates with thirty-three notes in the upper voice on “beati Iacobi” (shown in Figure 2b). Both in the monophonic respond and polyphonic verse, singers musically highlight the voice of St James as a thunderous preacher.

Table 2.

Passion of St James (25 July), principal chants referencing the Sons of Thunder. Latin texts are in E-SC, Codex Calixtinus, fols. 104v–7v, 118r–21v. All translations are from (Coffey and Dunn 2021, pp. 331–33, 338, 343, 371–78). Abbreviations: 1V (First Vespers), A (antiphon), H (hymn), M (Matins), R (responsory).

Figure 1.

Responsory Dum esset Salvator for the Passion of St James (respond only). Source: E-SC, Codex Calixtinus, fol. 107v.

Figure 2.

(a) Polyphonic setting of Dum esset Salvator, attributed to Master Ato (melismas on vox tonitrui). Source: E-SC, Codex Calixtinus, fol. 216v (alternate foliation 187v). (b) Polyphonic setting of Dum esset Salvator, attributed to Master Ato (melismas on beati Iacobi). Source: E-SC, Codex Calixtinus, fol. 217r (alternate foliation 188r).

Other expressive devices enhance the imagery of the Mass offertory Ascendens Ihesus in montem. The verse Et enim sagitte condenses Psalm 76:18–19 to compare the worldwide projection of the Lord’s thunderous voice to the Lord’s piercing arrows (or thunderbolts),23 omitting the ensuing depiction of lightning and an earthquake. This militant analogy, comparing the sound of thunder to a weapon, recalls other biblical texts associating storms with divine force, such as Psalm 17:14–15, “And the Lord thundered from heaven, and the Highest gave his voice, hail and coals of fire. And he sent forth his arrows, and he scattered them,” and Revelation 8:5, describing the actions of the angel at the golden altar before the throne of God: “And the angel took the censer and filled it with the fire of the altar and cast it on the earth, and there were thunderings and voices and lightnings and a great earthquake.”24 These textual associations resonate with the apocalyptic context of the chant’s melodic model, based on the offertory Stetit angelus for the warrior St Michael. Paraphrasing Revelation 8:3–4,25 Stetit angelus focuses on the smoke of the incense in the golden censer that ascends before God prior to the emptying of its destructive contents. In a detailed intertextual reading of the two offertories and their shared melody, Konstantin Voigt notes the extraordinary length of the forty-six note melisma on “Boanerges” in Ascendens Ihesus, which matches almost exactly the melisma on “ascendit” in Stetit angelus (shown in Figure 3).26 The accuracy of this musical quotation from a widely known chant increases the likelihood that singers and celebrants could have recognized the broader biblical and liturgical contexts in which divine thunder signals punishment.

Figure 3.

Comparison of melismas on Boanerges in the offertory Ascendens Ihesus for the Passion of St James and ascendit in the offertory Stetit angelus for St Michael. Sources: A = E-SC, Codex Calixtinus, fol. 121r; B = F-Pn lat. 776, fol. 117r.

The relevance of the potentially destructive and unquestionably resonant sound of the thunderous preaching voice of St James to the Compostelan clergy is elaborated in additional sermons that complement the chants of the Liber sancti Iacobi. In the Codex Calixtinus, the opening epistle attributed to Pope Calixtus explains that if these sermons cannot be read on the various feast days of St James during Matins and the Mass, due to their great length, then they should be read afterwards in the refectory (Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. 6). The sermon Vigilie noctis sacratissime, attributed to Pope Calixtus, comments on the Gospel reading (Mark 3:13–19) for the Vigil and interprets the sonic threat of thunder in a positive light:

The rain accompanying the apostles’ worldwide thunderous preaching is thus perceived by believers as a sign of divine mercy, and the lightning as a sign of the miraculous. Those who are receptive to the Gospel message receive spiritual refreshment and insight from the storm clouds of the apostles.Thunder makes frightful sounds, it irrigates the earth with rains, and it sends out lightning. Similarly, these two brothers [James and John] sent out frightful sounds when ‘their sound went out into the whole world, even their words unto the limits of the orb of the earth.’ [Romans:10:18] They irrigated the earth with rains when with their preaching, they made known to the minds of believers the rain of divine grace. They sent out lightning bolts when they gleamed with signs and miracles.(Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. 41)

Conversely, the sermon Exultemus in Domino for the seventh day within the Octave of the Passion of St James (31 July), attributed to the otherwise unidentified Pope Leo, contrasts the benefits of apostolic rain for Christians with the threatening force of apostolic thunder for non-Christians. After observing that “thunder strikes the clouds, emits lightning, makes the earth tremble, and irrigates with rains” (Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. 211), the sermon explains that James thundered before John because he was the elder of the two brothers. The target of his thunderbolt is specifically the Jews:

Here the thunder of James attacks Jewish “malice” or persecution of Christians, “harshness” or resistance to Christian interpretations of Old Testament prophecy, and “envy” or rejection—even criminalization—of Christian spirituality. In this stormy battle between the Old and New Law, James triumphs by “illuminating the hearts of the simple” who accept Christianity, flashing with miracles and pouring out “salubrious rain” (Coffey and Dunn, p. 212). Both the destructive and nurturing associations of thunder in these sermons might have helped the clergy to reflect on and interpret references to the worldwide circulation of the apostles’ voices in chants such as the offertory Ascendens Ihesus in montem and the responsory Dum esset Salvator.The most blessed James, filled with the Holy Spirit, struck the Jewish clouds with his preaching. For he disclosed their malice, upbraided their harshness, confounded their envy. … Above all, James exposed them to Jesus Christ when he showed the promise from the law and from the prophets. He reminded them of the favors He had procured, and he made known to them the eternal torments—if they were ungrateful for these great favors—unless they should do penance. Thus, the most blessed James thundered with threats by dissipating the thickness of their sins.(Coffey and Dunn 2021, pp. 211–12)

For the Compostelan clergy venerating St James as an apostolic model, the aforementioned sermon Exultemus in Domino, attributed to Pope Leo, invokes apostolic action in language that was echoed musically in the polyphonic appendix to the Liber sancti Iacobi. After summoning the clergy to “celebrate the solemnities of Saint James … with devout minds” (Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. 217), the sermon concludes with a sonorous appeal:

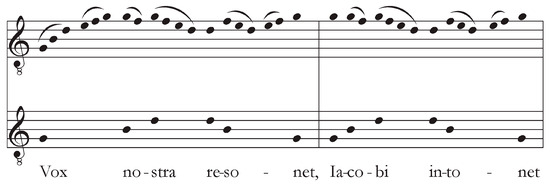

This succinct yet resonant call to the singers to thunder, instead of sing, praise for St James differs from the aforementioned chants referencing the Boanerges and describing their thunder through use of the hortatory subjunctive. Now the singers harmonize their own voices to thunder for the benefit of their apostolic patron. In performance, the upper voices would have showcased their virtuosity in the opening six-note melisma on “vox” spanning an octave (from low G to high g)—the full range of the melody (shown in Figure 4). Moreover, melodic repetition in both the lower and upper voices matches the sound of the singers’ resounding voices ([Vox] nostra resonet) with the thunderous praise of James (Iacobi intonet). By thundering themselves, the singers vocally model the process of imitation advocated by Pope Leo.

Just as the thunderous preaching voice of St James was perceived to dissipate the clouds of the sinful and irrigate the hearts of believers, so the clergy should embody the “sons of thunder” through virtuous living and apostolic teaching. Similarly, the singers performing the two-voice hymn Vox nostra resonet, attributed to Iohannes Legalis, give voice to the apostle’s thunder:Let us imitate, therefore, Saint James, and with our imitation of him and with help from him, let us become sons of thunder! Let us break asunder the clouds of our sins with our preaching! … Let us water the hearts of the simple with the salubrious rain of preaching, and let us offer the seeds of virtue with our admonitions! If we have truly acted in this way, we will be sons of thunder!(Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. 218)

| 1 | Vox nostra resonet, Iacobi intonet laudes Creatori.27 | Let our voices resound and thunder the praise of James to the Creator.28 |

Figure 4.

Polyphonic hymn Vox nostra resonet, attributed to Iohannes Legalis (first two phrases). Source: E-SC, Codex Calixtinus, fol. 216v (alternate foliation 187v).

The music and sermons of the Liber sancti Iacobi emphasize and embellish central themes in the Gospel account of the Boanerges and other biblical depictions of thunder to promote the reach and relevance of the apostle’s exemplary preaching. Rooted in the authority of the bible, intersections between the key Gospel passage (Mark 3:17) and related texts (especially Psalm 76) vividly illustrate the worldwide resonance and divinely-sanctioned force of the apostle’s thunderous voice and its coexisting salubrious/destructive effects. Inspired by the authority of the Church Fathers, the thunder of James is further differentiated from that of John, both textually and musically. Through prolonged melismas, extended melodic range, and musical quotation, the singing clergy sound the impact of James’s thunder and assume his apostolic voice.

4. Thunderous Preaching, Prophecy, and Sublimity in Chants for St John the Evangelist

Compared to the explicitly apostolic resonance of the thunderous voice of James, liturgical and hagiographic interpretations of the thunder of his younger brother John are less consistent, reflecting the diversity of the Evangelist’s attributes and epithets. The variety of John’s attributes is emphasized in a fourteenth-century commentary on one of the most widely-circulating chants specific to the Mass observed on the Evangelist’s principal feast (27 December), the sequence Verbum dei. The commentary associates each of John’s epithets with those of a different biblical or saintly figure, embellishing the standard interpretation of John’s name as “the grace of God”:29

These and even more diverse epithets appear in decorative initials of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century graduals (chant books for the Mass) for each versicle of Verbum dei, with three particularly sonorous examples: Boanerges, vox tonitrui, and tuba verbi (trumpet of the word) (Hamburger 2008a, pp. 168–69). While the aforementioned choir books were conceived for one particular religious community, the Dominican convent of Paradies bei Soest in present-day Germany, these sonorous epithets circulated widely in chants of the Johannine liturgy sung by various communities throughout the medieval West. Indeed, both the standardized and localized components of the Johannine liturgy juxtapose the Evangelist’s different attributes in ever-shifting combinations, to underscore John’s distinction as the most beloved and insightful of Christ’s disciples.31 By examining pairings of John’s thundery epithets with several of his other attributes—as a martyr, virgin, visionary, and prophet—in a variety of chants with imagery that is explained in well-known sermons and commentaries, the following analysis demonstrates the many different ways that singers gave voice to John’s evangelical and prophetic sublimity.John is interpreted as the grace of God or in whom there is grace, since God furnished him with several gifts of grace. For Isaiah considered it great grace that God made him a prophet. Peter considered it great grace that God made him an apostle. Luke considered it great grace that God made him an evangelist. St. Lawrence considered it great grace that God made him a martyr. St. Augustine considered it great grace that God made him a confessor and a doctor. St. Catherine considered it great grace that God made her a virgin. All this is found in John. For he was a prophet, an apostle, an evangelist, a martyr, a doctor, and a virgin.30

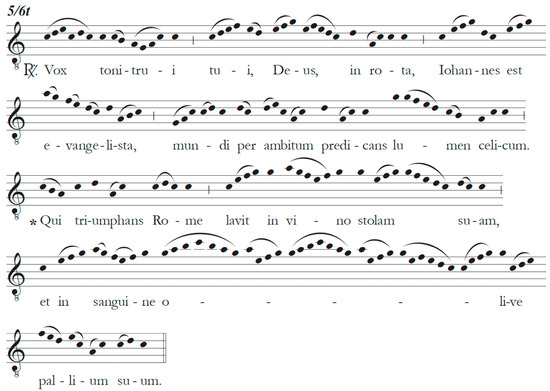

Among the standard chants of the Office (Hesbert 1963–1979, vols. 3–4), only one for the Evangelist’s principal feast associates John with the voice of thunder, the responsory Vox tonitrui:

The responsory begins with a direct quote from Psalm 76:19 invoking the thunderous voice of God before identifying John the Evangelist as a preacher disseminating the light of the Gospel throughout the orbicular world. The divinely-inspired vocal model for John’s preaching reflects the widespread belief that John had spread the Gospel by speech alone until the death of his persecutor, the Roman emperor Domitian (r. 81–96)—as explained, for example, in a homily for the feast of the Evangelist by the Venerable Bede: “From the time of the Lord’s passion, resurrection, and ascension into heaven, up until the last years of the ruler Domitian, during about sixty-five years, he had preached the word without any supporting base in writing.”33 The responsory’s vivid description of John’s preaching voice leads directly to an equally vivid account of the Evangelist’s miraculous survival from submersion in boiling oil at the Latin Gate in Rome, inspired by apocryphal and patristic narratives of the Evangelist’s corporal punishment by Domitian for having refused to deny his Christian faith and to cease his preaching mission.34 The description of John’s ordeal in the responsory text derives from Genesis (49:11) “he shall wash his robe in wine and his garment in the blood of the grape,” replacing the grape with the olive. This word substitution simultaneously equates the oil, commonly known as the “blood” of the olive, in which John was boiled with the blood of martyrdom. That John had been spared the suffering of a martyr’s death was attributed to his virginity,35 hence the ensuing reference to John’s virginal body dancing in the oily flames.

| R: Vox tonitrui tui, Deus, in rota, Iohannes est evangelista, mundi per ambitum predicans lumen celicum. Qui triumphans Rome lavit in vino stolam suam, et in sanguine olive pallium suum. | Respond: The voice of thy thunder, God, in a wheel; John is the evangelist preaching the heavenly light throughout the orbit of the world. Who, triumphing in Rome, washed his robe in wine, and his cloak in the blood of the olive. |

| V: Victo senatu cum Cesare, virgineo corpore tripudiat in igne. | Verse: Having overcome the senate and Caesar, with his virginal body he dances in the fire. |

| (Repetendum: Lavit in vino stolam suam, et in sanguine olive pallium suum.)32 | (Repetendum: [He] washed his robe in wine, and his cloak in the blood of the olive.) |

The responsory’s vivid language is matched by its melodic virtuosity (see Figure 5). Particularly striking are the ascending scalar passages on “vox” spanning the interval of a third (from c to e), “tui” spanning a fourth (c to f), and “Iohannes” spanning a fifth (c to g), the highest of the three leading up to the descending scalar passages on the words “Evangelista” spanning an octave (from a’ to a) and “lumen” spanning a sixth (from g to b), referencing the heavenly light of the Gospel. In these phrases focusing on John’s preaching, the musical highpoint (rising to a’) further highlights the Evangelist. The ensuing account of John’s martyr-like ordeal—repeated in the repetendum at the end of the verse—extends the melodic range even higher (rising up to c’ twice) in an elaborate melisma, with as many as thirty-six notes on the word “olive”. All of these expressive features would have showcased the singers’ voices, heard, perhaps in this context, as an earthly echo of the heavenly voice of thunder.

Figure 5.

Responsory Vox tonitrui for the principal feast of St John the Evangelist (respond only). Source: NL-SHbhic 149, fols. 22v-23r. Adapted from (Saucier 2021, p. 19).

In a more obscure versified Office for the feast of John’s ordeal at the Latin Gate (6 May),36 the responsory Rorat celum equates the heavenly dew that was imagined to have protected the Evangelist’s virginal body from the heat of the boiling oil with the rain of his preaching before depicting the physical force of John’s thunder against the enemies of the Gospel:37

John’s battle name “Son of Thunder” anticipates his war-like attack on heretics.40 The choice of the word telum, meaning alternatively an offensive weapon such as a javelin, spear, or arrow and a beam of light or lightning, effectively merges the martial and tempestuous associations of the thunderbolt. Equally significant are the names of the heretics—Ebion, Cerinthus, and Marcion—against whom John was believed to have written his Gospel.41 The identification of these heretics as “antichrists” resonates with the language of the aforementioned homily by Bede, who denounces their tactics: “But when he [John] was sent into exile by Domitian, … there were heretics forcing their way into the Church, like wolves into a sheepfold devoid of a shepherd—Marcion, Cherinthus, Ebius, and other antichrists, who denied that Christ had existed before Mary, and who soiled the simplicity of the gospel faith with their perverse teachings.”42 The urgency of this resistance to the apostolic mission, believed to have intensified during the period of John’s exile on the island of Patmos following his survival from the boiling oil in Rome, is overcome by the destructive power of John’s thunderbolt. Both responsories, Rorat celum and Vox tonitrui, pair the voice of thunder with an impending threat—heresy or corporal punishment—to demonstrate the strength of John’s faith and the power of his preaching.

| R: Rorat celum, nubes pluit, Filius Tonitrui mittit telum, hostis ruit sacri evangelii, ut tres isti antichristi Ebion, Cerintus | Respond: Heaven drips with dew, the cloud rains, the Son of Thunder hurls [his] thunderbolt; the enemies of the sacred Gospel fall, notably these three antichrists, Ebion, Cerintus, |

| V. Et Marcion, heretici, Christi crucis inimici, zizania seminantes in medio tritici.38 | Verse: And Marcion, the heretical enemies of the cross of Christ sowing weeds in the midst of wheat.39 |

The contrasting effects of John’s thunder, at once destructive and illuminating, are evident in commentaries on one of the most widely-circulating Johannine chants of the Mass, the aforementioned sequence Verbum dei. The sequence text itself identifies the Gospel writer and “Son of Thunder” as the virginal guardian to the Virgin Mary, alluding to the well-known Gospel passage in which Christ on the Cross entrusts John with his mother’s care (John 19: 26–27):

| 5a | Iste custos uirginis archanum orginis diuine misterium scribens ewangelium mundo premonstravit. | The protector of the Virgin showed the world the arcane mystery of divine origins, writing his gospel. |

| 5b | Celi cui sacrarium Christus suum lylium Filio Tonitrui sub amoris mutui fide commendavit.43 | The heavenly shrine— his lily—Christ entrusted to the Son of Thunder in the faith of mutual love.44 |

An interpretation of this versicle in the aforementioned commentary on Verbum dei departs from the allusion to this scene at the foot of the cross to emphasize John’s dual identity as the author of the fourth Gospel and of Revelation:

Quoting Revelation (6:1) “And I saw that the Lamb had opened one of the seven seals, and I heard one of the four living creatures as it were the voice of thunder saying, ‘Come, and see’,”46 the sequence commentary conflates John’s apocalyptic vision with his Gospel message. The ensuing distinction between the polarized perceptions of his thunderous voice—as terrifying and illuminating—resembles a seventh-century commentary on the Apocalypse by Andrew, Archbishop of Caesarea, who differentiates “the fearsome and astonishing aspect of God against those unworthy of his long-suffering” from those “who are worthy of salvation” for whom lightning and thunder “inspire enlightenment, the one to the eyes of the mind and the other to the spiritual ears.”47 Thus, the sound of John’s thunder at once destroys heretical beliefs and stimulates spiritual insight. As we shall presently observe, the imagery of this combined apostolic-apocalyptic interpretation of Verbum dei and the virginal associations in the sequence’s original text are similarly found in other examples conceived for different religious communities.John is called the Son of Thunder or the voice of thunder, whence he relates in the Apocalypse: “I saw one of the four living creatures and I heard him as it were a voice of a great thunder.” The evangelists are alluded to by the four living creatures, among whom he himself was the voice of thunder, just as the church sings of him. For he terrifies with the sound of thunder and at the same time illuminates on account of the glory of the one who is coming. Thus St John terrified and expelled the heretics with his doctrine and fruitfully enlightened the minds of the faithful; therefore he is called the voice of thunder.45

Just as John’s thunder might stimulate varied forms of sensory perception, his voice became associated with varied forms of sonic production in more localized sequences sung on the Evangelist’s principal feast. John’s symbol, the eagle—reflecting the attribution of the four beasts in Ezekiel (1:10) and Revelation (4:6–15) to the four evangelists—invited vibrant comparisons between his heavenward flight and the lofty resonance of his voice. The sequence Dies ista que sacrata, preserved in thirteenth- and sixteenth-century sources from Compiègne and Amiens in present-day northern France, describes the Son of Thunder as a celestial eagle thundering from a cloud:48

The allusion to the Son of Thunder’s special status as God’s “secretary” or keeper of divine mysteries and protector of the Virgin Mary justifies his eagle-like ascent to heaven, from which the eagle thunders. The implied rain emitted from the thundercloud becomes the source for the fluid dissemination of the Gospel—typically associated with the four rivers of Paradise.50 The confluence of aquiline, aquatic, and sonic imagery in the third versicle resembles the prophet Ezekiel’s description of the sound of the four eagle-faced beasts (1:24): “And I heard the noise of their wings like the noise of many waters, as it were the voice of the most high God.” That the heavenly sound of the eagle is specific to the thunder of John is explained by St Augustine in his commentary on the Fourth Gospel:

| 2a | Hic electus et dilectus Dei secretarius | This chosen and beloved secretary of God |

| 2b | est probatus et vocatus Tonitrui filius. | is esteemed and called the Son of Thunder. |

| 3a | Amor prolis, tutor matris, celi prepes aquila, nube verbi tonat orbi scripturarum flumina.49 | Beloved of the progeny (i.e., the disciples), protector of the mother (i.e., the Virgin Mary), the swift eagle of heaven thunders in a cloud the rivers of the scriptures of the Word to the world. |

Thus the eagle-like John alone merits the distinction of thundering from the highest heavens—reflecting the sublimity of his Gospel message.In the four Gospels, … the holy Apostle John, not unjustly compared to an eagle because of his spiritual understanding, has elevated his preaching more highly and much more sublimely than the other three. … He thundered at the beginning of his discourse, elevated himself not only above the earth and above all the circuit of air and sky, but also above even the whole host of angels and above the whole hierarchy of invisible powers; and he came to him through whom all things were made, saying “In the beginning was the Word”.(Augustine of Hippo 1993, Tractate 36, p. 81)

Other sequences quote or paraphrase the distinctive opening of the Fourth Gospel, “In principio erat verbum” (John 1:1), specifically in John’s thunderous voice. An exceptional concentration of sensory descriptors embellishes the melodious praise of John’s Gospel speech and eloquence in the sequence Celum laudes moduletur.51 Preserved in a late thirteenth- and early-fourteenth-century gradual for the Dominican convent of St Mary Magdalene of Val di Pietra in present-day Bologna,52 the sequence lauds the aquiline Evangelist not only as a trumpet, herald, and thunderer, but also as a “symphonist”:

In the second versicle, John pours forth his Gospel, the new law, of which he is the trumpet and herald—conflating John’s identities as a preacher and a prophet. The trumpet was typically associated with prophecy, as exemplified through the divine summons in Isaiah (58:1) to “Lift up thy voice like a trumpet.” Moreover, in Revelation (1:9) John hears the “great voice as of a trumpet” calling him to prophecy to the seven churches in Asia. As divinely-inspired messengers, prophets were also considered to be heralds (Vauchez 2012, p. 67). Yet some exegetes associated the trumpet with the Gospel, as stated explicitly by Pope Leo the Great (d. 431) comparing the testimony of the Law and the oracles of the prophets to the “trumpet of the gospel” (Leo the Great 1994, Sermon 27, p. 139), and applied to John in the aforementioned epithet tuba verbi (trumpet of the word). In the third versicle, John is portrayed as “the lawgiver of the highest Word,” equating the New Testament Evangelist with the Old Testament lawgiver Moses. Subsequently, John soars above the highest heaven, where, as a visionary, he contemplates the luminous divinity. In the fourth versicle, John’s Gospel vision inspires his Gospel speech, embracing the dual meaning of the Latin adverb alte to equate the height of John’s intellectual ascent with the volume of his thunderous voice. Similar imagery characterizes a widely-transmitted homily on the prologue to the Fourth Gospel by the exegete John Eriugena (flourished 850–70),54 which begins by emphasizing the Evangelist’s voice:

| 2a | Fons doctrine hic Iohannes, qui celestes fudit annes per totam ecclesiam, | John, this fount of doctrine, who poured forth the heavenly streams through the whole church, |

| 2b | Paranimphus novi regis, novus doctor nove legis, tuba, preco, signifer. | [is] the bridesman of the new king, the new teacher of the new law, the trumpet, herald, standard bearer. |

| 3a | Hic electus, predilectus flos pudoris, sal dulcoris, verbi summi legifer, | This chosen, beloved flower of chastity, salt of sweetness, lawgiver of the highest Word, |

| 3b | Velud avis transvolavit celi summa, hic intravit et transcendit omnia. | just like a bird, flew over the summits of heaven; here he looked into and transcended all [things]. |

| 4a | Fontem lucis contemplatur, lux a luce, admiratur, raptus ad celestia; | He contemplates the fount of light; light from light, he marvels, rapt to the heavens; |

| 4b | Alte volans, alte videns, alte tonans, alte dicens, verbum in principio. | flying high, seeing high, thundering loudly, saying loudly: “The Word in the Beginning.” |

| 5a | O celestem symphonistam, O mirum evangelistam, O dulce eulogio; | O heavenly symphonist, O wonderful evangelist, O sweet eulogist!; |

| 5b | Arca novi testamenti, splendor veri firmamenti, aquila mirabilis.53 | ark of the New Testament, splendor of the true firmament, marvelous eagle. |

Both in the homily and in the sequence, the loudness of John’s voice and loftiness of his vision reflects the contemplative sublimity of his Gospel message. John’s vocality persists in the fifth versicle, praising him as a “symphonist” or chorister, evangelist, and eulogist. Moreover, the description of John’s voice as high, loud, and sweet resonates with conceptions of a vocal ideal. Isidore of Seville’s (ca. 560–636) patristic Etymologies, which circulated well into the fourteenth century, define the “perfect voice” as “high (alta), sweet (suavis), and loud (clara): high, to be adequate to the sublime; loud, to fill the ear; sweet, to soothe the spirits of the listeners.”55 As vocalized by the singers of the sequence, these idealized sensory attributes stimulate listeners to reflect on the many forms of John’s sublimity.The voice of the mystical eagle sounds in the ears of the Church. Let our exterior sense catch the sound that passes; let our mind within penetrate the meaning that abides. This voice is the voice of the high-flying bird, not he that flies above the material air and aether and the limits of the whole sensible world, but he that transcends all contemplation. … He does this with the swift-flying wings of profound theology.(O’Meara 1988, pp. 158–59)

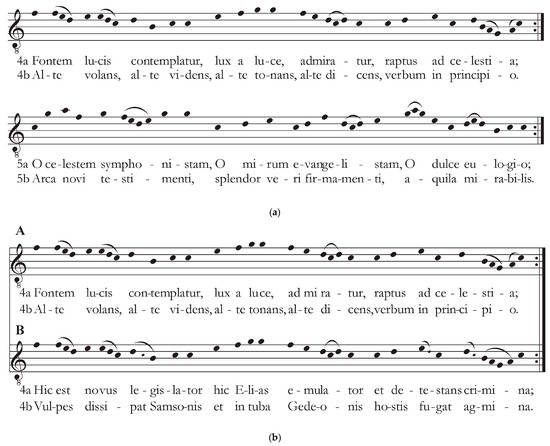

The melody of Celum laudes moduletur underscores the sensory references in the text. The paired versicle structure—repeating the same melodic phrase for the two stanzas of each couplet, typical of most sequences—is especially expressive in the fourth versicle (shown in Figure 6a). Here, John’s contemplation of the fount of light aligns with his lofty flight and vision, his luminous wonderment aligns with the loudness of his thunder and voice, and his heavenly rapture aligns with his Gospel speech, “The Word in the beginning.” Moreover, the lofty language of the fourth and fifth versicles coincides with the melody’s rising range, ascending to a high g for the first time on the words “lux a luce” and again on “alte tonans,” and to high g’s and a’ to praise the “celestem symphonistam,” echoed in the exclamatory “O” invoking the sweet eulogist. Although the sequence melody rises even higher (to b’ and c’) in subsequent versicles, the gradual ascent of the singers’ voices may have been perceived as a musical counterpart to the upward flight of the aquiline Evangelist.

Figure 6.

(a) Sequence Celum laudes moduletur for the principal feast of St John the Evangelist (versicles 4–5). Source: I-Bmm 518, fols. 192v-93r. (b) Comparison of versicle 4 in the sequence Celum laudes moduletur for St John the Evangelist and the sequence In celesti ierarchia for St Dominic. Sources: A = I-Bmm 518, fol. 192v; B = D-DÜl D 11, p. 592, transcribed in (Hamburger et al. 2016, vol. 2, p. 66).

The expressivity of Celum laudes moduletur increases when we consider its melodic connections to another sequence, In celesti ierarchia,56 for St Dominic, who founded the Order of Preachers and was venerated as an apostle (Jacobus de Voragine 1993, vol. 2, p. 44). Included in the Dominican liturgy standardized by Humbert of Romans in the mid thirteenth-century, In celesti ierarchia summons the singers to “sound forth with full voice,” perhaps inspired by the fact that St Dominic was known to have favored loud and fervent singing (Fassler 2004, p. 258 n. 81). A striking textual parallel to Celum laudes moduletur occurs in the fourth versicle (see Table 3), in which Dominic is hailed as a “new lawgiver” who uses the “trumpet of Gideon” to combat enemies of the faith. Here Dominic’s preaching against heresy is compared to Gideon’s divinely-assisted battle against the enemies of the Midianites, which he waged to the sound of three-hundred trumpets (Judges 7:16–22). A melodic comparison of the fourth versicle in the two sequences (shown in Figure 6b) reveals how Gideon’s trumpet call aligns with John’s thunder, as the singers declaim the words “alte tonans, alte dicens” and “et in tuba Gedeonis” to the exact same melody, reaching the musical highpoint on the words “tonans” (thunder) and “tuba” (trumpet). The melodic convergence of these ideas may have reminded Dominican singers of the similarities between the loud and threatening sounds of thunder and the war trumpet, both signaling immanent destruction. Thus, even in the context of the sublime, mystical imagery of Celum laudes moduletur, John’s loud and thunderous Gospel voice—musically modeled on Gideon’s war trumpet in In celesti ierarchia—retained its capacity to instill fear among the Gospel’s opponents.

Table 3.

Comparison of versicle 4 in the sequence Celum laudes moduletur for St John the Evangelist and the sequence In celesti ierarchia for St Dominic.

Indeed, early Christian commentators were careful to distinguish the sound of the Evangelist’s thunderous voice, as perceived by believers, from the mere noise of natural phenomena. St John Chrysostom observes: “Thunder truly arouses terror in our souls because it has an unexplained sound. The voice of this man [John], however, does not disturb any of the faithful, but even frees them from terror and confusion. It terrifies only demons and their slaves” (John Chrysostom 2000a, Homily 1, p. 7). Drawing on a musical analogy, Chrysostom further describes John’s voice as “more sonorous than thunder” and observes, “It is truly a wondrous thing that the sound, though so great, is not harsh or discordant, but sweeter and more pleasing than all musical harmony” (John Chrysostom 2000a, Homily 1, p. 4).

Just as John had many epithets, his thunder could be vocalized and heard in different ways. Through the condensed contrasting phrases of the responsory and abridged narrative structure of the sequence, John’s thunder became linked to his martyrdom, virginity, Gospel preaching, and prophecy. As demonstrated by the exegetical contextualization of these musical examples, his thunder could serve equally varied purposes: to disseminate the Gospel, attack heretics, and enlighten believers. Highlighted through ascending phrases, a heightened vocal range, and melodic quotation, John’s thunder could be further perceived as threatening, resonant, or heavenly. When invoked in Christian worship, John’s thunderous voice—testing the limits of human perception—may thus have been understood by the faithful to sonically simulate some of the most perplexing and sublime mysteries of the faith.

5. Conclusion: Thundering Gospel Speech, Sounding the Supernatural

The thunderous voices of the brothers James and John were not only idealized through the music of liturgical worship but might also have been heard in the liturgical performance of Gospel speech. In the observance of the Mass, the reading of the Gospel was customarily differentiated from other texts both in sound, through a special tone, and in place, from an elevated location. On the feasts of the Boanerges, how did the musical sound of the apostles’ thunder intersect with the vocal performance of the Gospel?

The aforementioned medieval association of the Latin verb tonare (to thunder, or to speak in thunderous tones) with the noun tonus (a sound or tone) would have been especially relevant to the special tones used for the intonation of the Gospel—the tonus evangelii. To facilitate vocal projection, these formulae consisted primarily of a monotone, the pitch of which was designated as the tenor, or, in medieval sources, as the tuba (trumpet) to emphasize its loudness (Apel 1990, p. 204). When we recall that the preaching of James and John was perceived to have been exceptionally vociferous, the association of their thunder with the resonant Gospel tone would have been particularly vibrant during the intoning of the Gospel on their respective feast days: the reading of Mark 3:13–19, describing Christ’s mountaintop preaching call to the disciples and naming of the Boanerges, on the Vigil of St James; and the reading of John 21:19–24 in the Evangelist’s own voice, quoting Christ’s ambiguous statement that John would “remain” until His return, on the principal feast of St John. The Gospel intonation for St John was further distinguished, in some churches, with a more melodically elaborate tone (Hiley 1997, p. 55).

From early Christian times onwards, the Gospel was read by the deacon from a raised platform, and by the later Middle Ages, the eagle lectern had literally ascended to an ambo or rood-loft perched atop the rood-screen (also known as the jubé)—the highest position at the entrance to the choir.58 The Carolingian writer Amalarius of Metz (ca. 775–ca. 850) identifies the deacon at once as a minister of Christ and as a prophet who has “risen up” to be heard.59 From this elevated location, the deacon was expected to introduce and recite the Gospel alta voce, as documented by the thirteenth-century liturgical commentator William Durand (Guillaume Durand 1995–2000, vol. 140, pp. 338, 354), or, according to Amalarius, in a prophetic “trumpet call” (Amalar of Metz 2014, vol. 2, p. 109). These descriptors recall the lofty imagery of John’s thunderous voice, particularly in the sequences sung immediately prior to the recitation of the Gospel. In this liturgical context, John’s musical thunder would have anticipated the sonorous voice of the deacon, intoning the Gospel from on high. The resulting web of interrelated sonic associations may thus have prompted singers and listeners alike to open their “spiritual ears” to experience the sublimity of the Evangelist’s voice.

Comparative study of the medieval liturgies in which the thunder of James and John was vocalized demonstrates how the same tempestuous metaphor gave resonance to the individualized mission of each saint. The sonic properties of thunder provided an exceptionally sonorous, commanding metaphor for the vocal dissemination of the Gospel and the representation of Gospel speech in liturgical performance. Yet, natural imagery of all types permeates biblical, hagiographic,60 and liturgical narratives to signal the presence and influence of the divine. Just as environmental histories have emphasized the interplay of metaphor and materiality in the cultural meanings associated with the physical world (Bintley and Franklin 2023, p. 3), liturgical studies might further explore relationships between metaphor and sonority in representations of the otherworldly. The liturgical use of natural metaphors to symbolize the supernatural interprets the most elusive and intangible aspects of religious belief from the perspective of familiar, shared, physical realities. Moreover, through liturgical performance, sonic metaphors acquire vocal agency by the participating clergy and a vocal immediacy for attending believers. Rooted in lived experience,61 multisensory perceptions of the natural world are a point of intersection between religious studies and environmental history that merits more extensive inquiry. Greater attention to these varied natural metaphors, and especially their sonic manifestations in religious worship, has the potential to expose more broadly the spectrum of sounds and meanings associated with the confluence of natural elements and supernatural communication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

A preliminary version of this study was presented at the 59th International Congress on Medieval Studies (2024). I wish to thank the anonymous readers of this journal for their insightful suggestions and Zachary Bush for formatting the musical examples. All translations are my own unless otherwise noted. The orthography of the Latin texts follows that of the cited primary source or edition. Latin abbreviations are resolved without comment. Capitalization of proper names and punctuation is editorial. All biblical passages are quoted from (The Vulgate Bible: Douay-Rheims Translation 2010–2013). Library sigla follow RISM (https://rism.info/community/sigla.html, accessed on 20 October 2025), indicating country, city, institution, and selfmark.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AH | Analecta hymnica medii aevi, ed. Guido Maria Dreves et al., 55 vols. [Leipzig: O.R. Riesland, 1886–1922], http://webserver.erwin-rauner.de/crophius/Analecta_conspectus.htm (accessed on 20 October 2025) |

| BHL | Société des Bollandistes, Bibliotheca hagiographica latina antiquae et mediae aetatis, 4 vols. [Brussels, 1898–1901, 1911, 1986] |

| NL-SHbhic | ’s-Hertogenbosch, Brabants Historisch Informatie Centrum |

Notes

| 1 | (Culpepper 1994, pp. 38–40). The characterization of James and John as hot-tempered and outspoken derives from two Gospel passages in which they are rebuked by Christ: when the Samaritans refuse to receive Christ, James and John ask, “‘Lord, wilt thou that we command fire to come down from heaven and consume them?’ And turning he rebuked them” (Luke 9:54–55); and their request for heavenly glory, “Grant to us that we may sit one on thy right hand and the other on thy left hand in thy glory,” to which Christ responds, “To sit on my right hand or on my left is not mine to give to you” (Mark 10: 37 and 40). The Church Father St Jerome (d. 419/20) identified James and John as “Sons of Thunder” in his interpretation of their hot-tempered reaction to the Samaritans: “James and John, who were truly the sons of thunder, and Phinees and Elias, burning with ardent desire, wish to bring fire down from heaven and they are rebuked by the Lord” (Saint Jerome 1965, p. 318). Similarly, the Dominican friar Jacobus de Voragine (ca. 1230–98) emphasized the shared character of the brothers James and John, noting their zeal to avenge Christ (referencing Luke 9:54) and ambition (refencing Mark 10:37) immediately prior to his interpretation of their shared name Boanerges in his widely known Golden Legend (Jacobus de Voragine 1993, vol. 2, p. 3.). |

| 2 | (Arnold 2020, p. 363): “Dual and dualing use of natural metaphors to represent both sin and salvation, hope and fear is one that belies any simple arguments about connections between Christianity and nature.” Arnold advocates for a more interdisciplinary approach on p. 365: “Historians interested in the role of nature in the cult of saints should also draw on comparative humanities as we re-think, re-frame, and re-vision the function of medieval natural symbolism and metaphor.” |

| 3 | (Loic 2019, p. 420): “In and around altars, both portable and fixed, invocations of the Thunderer invited the celebrant to channel the vox domini much like the prophets and apostles before him.” |

| 4 | (Loic 2019, pp. 406–7): “References to the Thunderer regularly played on the idea of praying and thundering as part of a call and response. … The faithful addressed their vocal celebrations and appeals to the Thunderer, who had many means by which to respond, among them his earthly messengers.” |

| 5 | See, for example (Loic 2019, p. 413; Boynton et al. 2016; Pinet 2025). |

| 6 | See, for example, Hrabanus Maurus, De rerum naturis (dated 840s): “Thunder sometimes signifies the divine voice in the Scriptures.” Quoted by (Loic 2019, p. 413). |

| 7 | I have modified the Douai-Rheims translation, changing “the clouds sent out a sound” to “the clouds sent forth their voice” (vocem dederunt nubes in the Latin original). |

| 8 | (Augustine of Hippo 2002, p. 86). The editors note the frequency with which Augustine associates clouds with preachers. |

| 9 | Note, however, that the editor does not identify the source for this quotation and I have not found it in Bede’s sermon for St James. |

| 10 | For the Western transmission of the Acts of John by Prochorus, see (Kempf 2008, pp. 69–78) and (Saucier 2023). |

| 11 | My summary of this narrative is based on (Culpepper 1994, pp. 220–21) and (Ševcenko 2013, pp. 1–3). |

| 12 | E-SC, Codex Calixtinus. My study of the Codex Calixtinus relies on the following facsimile, edition, and translation: (Jacobus 1993); (Herbers and Santos Noia 1998); and (Coffey and Dunn 2021). The Codex Calixtinus is currently thought to be the oldest and most complete copy—perhaps even the original exemplar—of the Liber sancti Iacobi, as argued by (Moisan 1992, p. 27) and (Fuller 2001, p. 221). |

| 13 | My discussion of the Compostelan liturgy for St James draws from the following scholarship: (Rankin 2001; Förster Binz 2004; Corrigan 2011; Voigt 2016; Ruiz Torres 2017; Coffey and Dunn 2021). |

| 14 | These factors are discussed by numerous scholars, including the following: (Moisan 1992, pp. 40, 106–7; Fuller 2001, p. 183; Corrigan 2011, p. 3; Ruiz Torres 2017, pp. 87–89; Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. 23). |

| 15 | Pope Calixtus II (r. 1119-24) cannot be the actual author, since he had died fifteen years prior to the earliest date of the compilation of the Liber sancti Iacobi, as noted by (Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. xxv). |

| 16 | These are the first two of three variants identified by (Coffey and Dunn 2021, pp. 319–20, n. 11). |

| 17 | The textual connection with this sermon is suggested by the rubric “sermo Calixti pape” for the Lauds antiphon Sicut enim tonitrui in E-SC, Codex Calixtinus, fol. 102v. |

| 18 | The textual connection with the portion of this sermon attributed to St Jerome is suggested by the rubric “sermo Iheronimi” for the Lauds Antiphon Recte Filii Tonitrui in E-SC, Codex Calixtinus, fol. 102v. |

| 19 | For definitions and distinguishing characteristics of the principal chant genres of the Mass and Office, see (Harper 1996) and (Hiley 1997). |

| 20 | The rubric reads “sermo Marci et Iheronimi” in E-SC, Codex Calixtinus, fol. 107v. |

| 21 | The musical setting of “Iacobi” in the verse, however, is identical to that of “Iohannem” in the respond. |

| 22 | E-SC, Codex Calixtinus, fols. 216v-17r (alternate foliation 187v-88r). |

| 23 | (Loic 2019, p. 408) notes that medieval artists depicted thunderbolts as arrows. |

| 24 | (Loic 2019, pp. 408–9) references both passages in her discussion of the biblical association between storms and weaponry. |

| 25 | The text of Stetit angelus derives from a pre-Vulgate source, as noted by (Maloy 2010, p. 82). |

| 26 | (Voigt 2016, pp. 175–77, 181–83). Stetit angelus belongs to a larger group of musically-related offertories, but as Voigt demonstrates, the degree of melodic resemblance as well as textual correspondence between Stetit angelus and Ascendens Ihesus suggests that the connections between these two offertories in particular were deliberate. |

| 27 | E-SC, Codex Calixtinus, fol. 216v (alternate foliation 187v). |

| 28 | Translated by (Coffey and Dunn 2021, p. 437). |

| 29 | For this well-known interpretation of John’s name, see (Jacobus de Voragine 1993, vol. 1, p. 50): “John (Johannes) is interpreted grace of God, or one in whom is God’s grace, or one to whom a gift is given, or to whom a particular grace is given by God.” |

| 30 | Translated by (Kihlman 2008, p. 115). This commentary on Verbum dei survives in a manuscript dated 1356 from the Benedictine monastery of St Paul im Lavanttal in present-day Austria. See pp. 101, 104. |

| 31 | For a discussion of this phenomenon in the Office chants, see (Volfing 2001, pp. 71–83). |

| 32 | NL-SHbhic 149, fols. 22v-23r. Catalogued by (Hesbert 1963–1979, vol. 4, no. 7921). |

| 33 | (Bede the Venerable 1991, Homily 1.9, p. 93). Bede’s homily is among a handful of standard sources for the readings at Matins on the principal feast of the Evangelist, as discussed by (Volfing 2001, pp. 72–73). |

| 34 | The earliest account of this legend is in De praescriptione haereticorum by Tertullian (d. after 220), and it circulated subsequently in a commentary on the Gospel of Matthew by St Jerome (ca. 347–419/420), an interpolated version of the fifth-century Passio Iohannis (BHL 4321), and the sixth-century Virtutes Iohannis (BHL 4316), as documented by (Junod and Kaestli 1983, pp. 775–80) and (Volfing 2001, p. 18). |

| 35 | As stated by Bede in Homily 1.9. See (Volfing 2001, pp. 79–80). |

| 36 | AH vol. 26 nr. 54 and (Hughes 1994, IP 34). |

| 37 | For the association of dew with virginity referenced in other chants for the feast of John at the Latin Gate, as well as John’s fluid dissemination of the Gospel, see (Volfing 2001, pp. 47, 77, 79–80, 103–4). |

| 38 | AH vol. 26 nr. 54. |

| 39 | Translated by (Volfing 2001, p. 20, n. 17). |

| 40 | The epithet “Son of Thunder” is identified specifically as a battle name by (Heiner 2008, p. 88). |

| 41 | (Volfing 2001, p. 43). Volfing identifies Cerinthus as a second-century gnostic who denied that Christ was the son of God, the Ebionites as a sect of Jewish Christians who believed that Christ was the son of Mary and Joseph, and Marcion as a second-century docetic who rejected the Old Testament and most of the Gospels. |

| 42 | (Bede the Venerable 1991, Homily 1.9, p. 93). Previously, St Jerome had described Cerinthus and Ebion as “antichrists” in the prologue to his commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, as discussed by (Volfing 2001, p. 43). |

| 43 | (Hamburger 2008b, p. xxviii). See also AH vol. 55 nr. 188, with minor variants. |

| 44 | Translated by (Hamburger 2008b, p. xxviii), with minor modifications. |

| 45 | Translated by (Kihlman 2008, p. 123). |

| 46 | I have modified the Douai-Rheims translation, changing “the noise of thunder” to “the voice of thunder” (vocem tonitrui in the Latin original). |

| 47 | (Andrew of Caesarea 2011, p. 82). Andrew’s commentary was translated into four ancient languages—Latin, Armenian, Old Slavonic, and Georgian—and influenced the acceptance of Revelation in the Orthodox Church (Greek, Armenian, Georgian, and Russian). See pp. 3–4, 39–40. |

| 48 | Dies ista que sacrata survives in a thirteenth-century winter missal and proser (F-Pn lat. 17318, fols. 315r-16v) for the Benedictine abbey of Saint-Corneille in Compiègne; and in a sixteenth-century antiphoner and gradual (F-Pn lat. 906, fols. 287v-89v) for the chapel founded by Jacques of Vendôme (d. 1524) in Amiens. It shares a melody with the sequence Ad mirandum et laudandum for St Benedict. See (Meyer 2022, pp. 210–11, 358–60, 729). |

| 49 | AH vol. 9 nr. 248. |

| 50 | On the dissemination of John’s Gospel like a river of Paradise, see (Volfing 2001, p. 77). |

| 51 | AH vol. 40 nr. 249. |

| 52 | I-Bmm 518, fols. 186r-88r and 191v-94v. For previous studies of this chant book and its contents, see (Ruini 2010); and (Roncroffi 2009, pp. 75, 77, 147–50). My thanks to Stefania Roncroffi for sharing digital images of these folios. |

| 53 | I-Bmm 518, fols. 192r-93r. See also AH vol. 40 nr. 249. |

| 54 | Eriugena’s homily survives in over sixty manuscripts and could have been read to the clergy on Christmas day during mealtime in the refectory. See (O’Meara 1988, p. 158). |

| 55 | (Isidore of Seville 2016, Book 3.20.14, p. 143). My translation is inspired by (Barney et al. 2006, p. 97), with modifications. Isidore’s concept of a “perfect voice” consisting of these characteristics circulated widely for centuries and also influenced secular literature, as noted by (Dyer 2000, p. 167). On the broader medieval association of sweet singing with the divine, see (Carruthers 2006, pp. 1002–3) and (Carruthers 2013, p. 93). |

| 56 | Identified by (Roncroffi 2009, p. 77). The common practice of contrafactum, by which new texts were set to existing melodies, generated families of medieval sequences related by a shared melody, “creating an interplay of exegetical meanings,” as noted by (Hamburger et al. 2016, vol. 1, p. 213). |

| 57 | Translated by Margot Fassler and Nicolas Kamas in (Hamburger et al. 2016, vol. 1, p. 279). |

| 58 | (Thibodeau 2007, p. 20): “The rood-loft (analogium) is so called because the Word of God is read and proclaimed in it.” |

| 59 | (Amalar of Metz 2014, vol. 1, p. 427): “The reading of the Gospel is appropriate for the deacon, because he is a minister. … As long as Christ preached the Gospel, he was made our minister. … The deacon also has the gift of prophecy, and rightly so, because he performs the duty of the one about whom it is said: ‘A prophet shall God raise up unto you of your brethren, like unto me, hear him’.” |

| 60 | For a hagiographic perspective, see (Arnold 2020, p. 360): “Vitae, miracle collections, and other aspects of saintly dossiers, including records of mystical visions, can help scholars better interpret the meaning and symbolism of abstract and imagined nature in broader Christian cultural dimensions.” |