Abstract

This multidisciplinary study investigates the enduring vitality of Guan Di worship on Peninsular Malaysia’s West Coast by proposing and systematically testing ‘Interpretive Malleability’ as a core explanatory mechanism. This is achieved through an integrated methodology combining historical anthropology, GIS spatial data, and a dual comparative analysis. By examining cases across different regions and historical periods, this analysis, both synchronic and diachronic, assesses how the mechanism operates in varied contexts. The study defines ‘Interpretive Malleability’ as a two-part process: an ‘Inherent Potential’ within the symbol, rooted in the ‘Persistence of the Human Prototype’, and a ‘Local Generative Process’ activated by local actors. Findings reveal that the uniqueness and vitality of Guan Di’s cult are forged in practice-oriented domains through the creative agency of its followers. Ultimately, this study offers a mechanism-based, agency-centered framework for understanding religious resilience, highlighting the dynamic interplay between a symbol’s intrinsic structure and local creative engagement.

1. Introduction

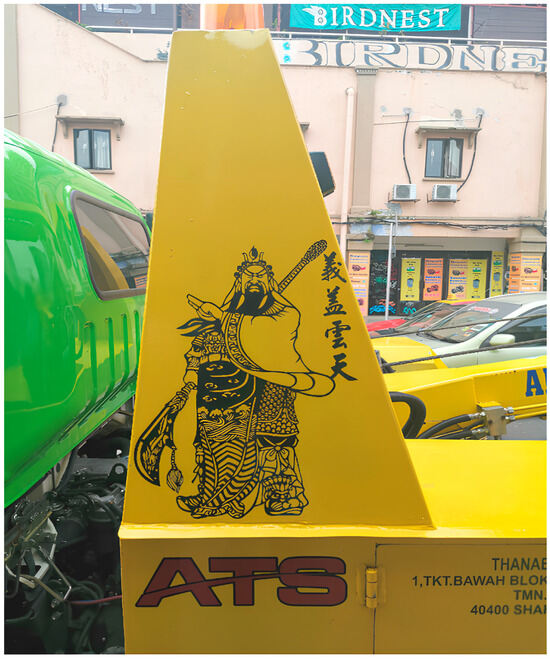

To walk along the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia is to witness the extraordinary and ubiquitous presence of a single deity. His image shifts and adapts to each new context. In a solemn temple, he might appear as a majestic warrior, clad in armor and wielding his iconic blade, a symbol of ultimate protection. Yet, in a quiet study or a clan association hall, he could be depicted as a robed scholar, thoughtfully reading the Spring and Autumn Annals (春秋), embodying civil virtues. Turn a corner into a bustling restaurant or a bus ticketing counter, and it is often that same imposing, martial effigy found overlooking the cash register, seamlessly transformed from a god of war into a powerful guardian of prosperity. He is just as present in modern shopping malls as he is in temples adorned with carved beams and painted rafters, where the smoke of coiled incense spirals around a constant stream of devotees. Then, amidst the daily traffic of Shah Alam, the astonishing adaptability of this deity comes into sharp focus. A yellow rescue vehicle stands out, not for its size, but for the immense totem emblazoned on its side: Guan Di, wielding his Green Dragon Crescent Blade, under the banner ‘Righteousness Covers the Heavens’ (義蓋雲天) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A rescue vehicle on the streets of Shah Alam, its body printed with an image of Guan Gong holding his blade. Image by author.

This capacity for functional application is then complemented by a spectacular display of his multifaceted nature during events like the Malaysia International Guan Gong Cultural Festival (MIGGCF). In 2023, the festival’s procession through Petaling Street (茨廠街) became a grand stage where his diverse Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist personas were simultaneously paraded and celebrated (Figure 2). Heralded by towering thirty-foot banners and led by lion dance troupes, the parade of Guan Di statues was escorted by a column of national and state flags. The event drew hundreds of participants and a diverse crowd of onlookers, including international tourists and non-Chinese devotees, transforming the city’s streets into a vibrant, cross-cultural ritual field.

Figure 2.

The 2023 MIGGCF procession passing through the main arch of Petaling Street, Kuala Lumpur.1 Image by author.

These vibrant contemporary scenes illustrate Guan Di’s astonishing adaptability and his multifaceted presence across diverse social domains. This raises the central inquiry of this study: What are the underlying mechanisms that grant this particular deity such exceptional vitality and malleability? This study argues that the answer lies in a unique mechanism termed ‘Interpretive Malleability,’ which is co-driven by the symbolic potential rooted in the ‘Persistence of the Human Prototype’ and the ‘Local Generative Process’ that activates it. Such a mechanism allows different communities to creatively reinterpret and utilize its symbolism to meet their own specific needs, thereby ensuring the faith’s enduring vitality and relevance.

2. Research Methods and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Research Site

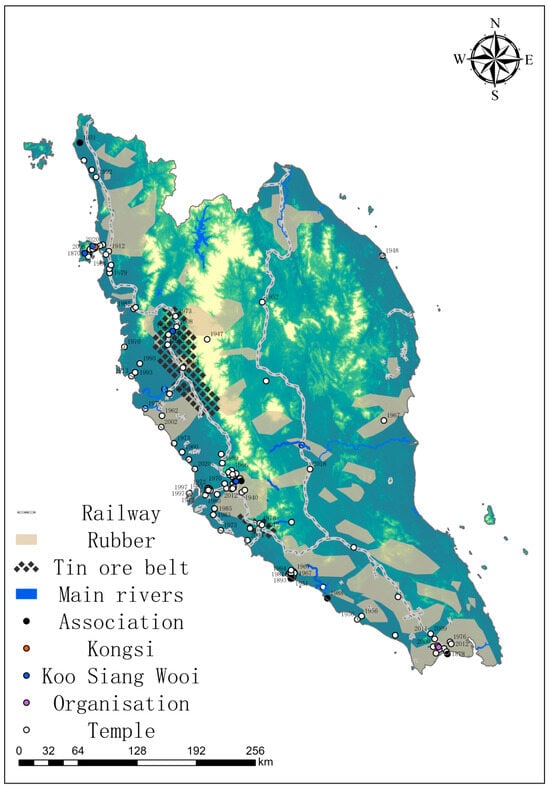

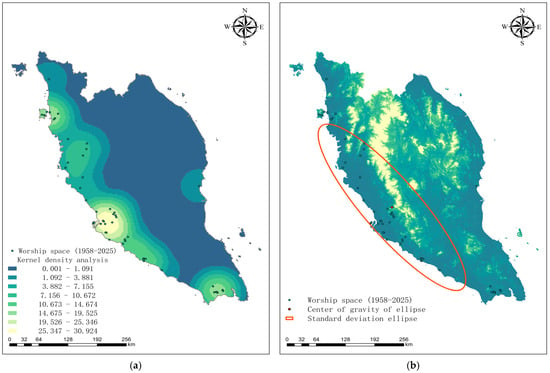

The selection of the West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia as the primary research site is empirically driven, establishing it as a unique socio-religious field (Bourdieu 1977) for this study. Guan Di worship flourishes here, vital to the lived religion of Malaysian Chinese (McGuire 2008). This study surveyed over 160 potential sites (Figure 3), with 89 investigated in-depth (as detailed in Table A1, which includes 69 temples, 10 associations, 6 Koo Saing Wooi Koon 古城會, 2 organisations, 1 Kongsi 公司, and 1 Clan).2 The analysis reveals a stark geographical concentration: 85 of these 89 investigated sites (95.5%) are located on the West Coast (Table 1). Complementing this spatial concentration is a significant temporal depth, as detailed in Table 2. The establishment of these worship sites spans from the early 19th century to the present day, with a notable peak during the post-independence era (1950–2000), a period of intense socio-economic transformation.

Figure 3.

Distribution GIS of 160 Guan Di Worship Sites on West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Image by author.

Table 1.

Distribution by Spatial Type (Total 89 Sites).

Table 2.

Distribution by Establishment Period (Total 89 Sites).

This profound spatio-temporal concentration, spanning from the early 19th century to the present, makes the region a microcosm of the Malaysian Chinese religious ecosystem. The West Coast’s history is deeply intertwined with the key arteries of economic activity, such as trade in its riverine and port city settlements, tin mining, and railway development, making it an ideal laboratory for examining the interplay between religious practice and socio-economic change. It is important to note that this study primarily focuses on sites where Guan Di is the main object of worship. If ancillary deity (配祀神) sites were also included, this geographical correlation would likely become even more pronounced. The West Coast is, therefore, the essential arena for this study. It was here that the social functions and cultural resonance of Guan Di worship were most acutely tested, proving the cult’s demonstrable vitality through the creative practices of ‘interpretive malleability.’

2.2. Research Methods

This study employs a multidisciplinary research design that synergizes qualitative historical ethnography with a multi-scale spatial analysis. The empirical core of this research is built upon three years of intensive multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork. This fieldwork involved investigating 89 confirmed sites of Guan Di worship, collecting their geographical coordinates (Table A1), and gathering photographic documentation and in-depth interview data.

Drawing inspiration from established frameworks in settlement geography, this study adopts a ‘macro-meso-micro’ analytical progression. The methodological objective is not merely to describe spatial layouts, but to use spatial patterns as an investigative starting point that prompts a deeper inquiry into how and why the exceptional ‘Interpretive Malleability’ of Guan Di worship manifests in different socio-historical contexts.

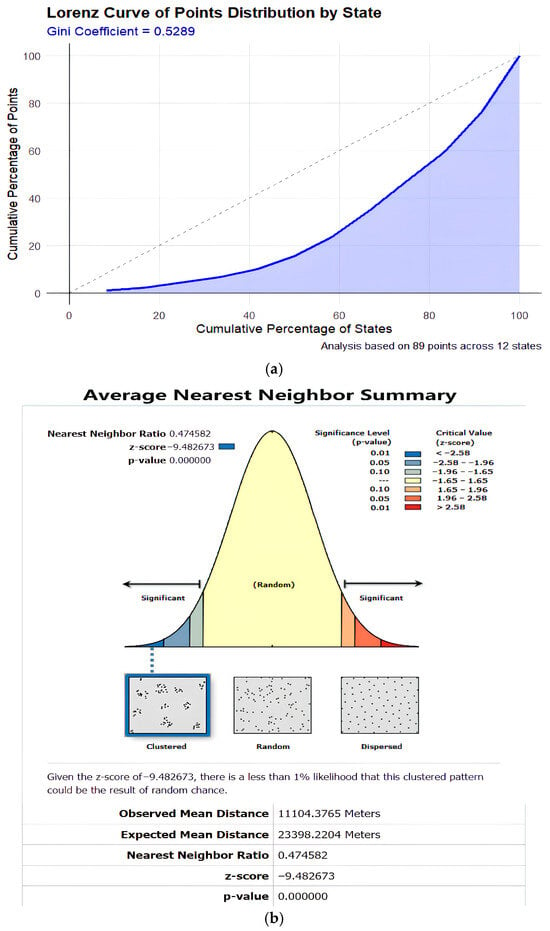

A dedicated GIS database was established using ‘OpenStreetMap’ as the foundational mapping platform. The GIS-based spatial analysis, conducted in ArcGIS, unfolds in a deliberate, multi-scale sequence. The analysis begins at the macro-scale with the overall distribution pattern. To quantitatively measure the degree of spatial imbalance across states, the Geographic Concentration Index (Gini coefficient) is used (calculated at 0.5289). Subsequently, the Nearest Neighbor Index (NNI) provides a quantitative baseline (R-value = 0.474582, Z-score = −9.482673, p < 0.01), statistically confirming that the overall point pattern is highly clustered, not random.

Moving to the meso-scale, this study delves into the spatial morphology of identified clusters. The analysis shifts to visualizing clustering intensity and identifying core hotspots through Kernel Density Estimation (KDE). To ensure the robustness of this analysis, the search radius for the KDE was determined in ArcGIS using the spherical function method. This approach is complemented by the use of Standard Deviational Ellipses (SDE), also executed within ArcGIS, to delineate and compare the directional trends and dispersion of the clusters over time. The integration of KDE with a robust bandwidth selection method and SDE provides a comprehensive understanding of the evolving spatial patterns of the clusters.

Finally, at the micro-scale, the analysis transitions from spatial description to functional interpretation. Having identified key clusters, the inquiry turns to why they formed in those specific ways. GIS is strategically used here to test hypotheses concerning the differing adaptations of Guan Di worship, for instance, within ‘Sin Sze Si Ya temples’ (仙四師爺廟) in the tin mining belt versus through the ‘fenxiang’3 networks and itinerant spirit mediums characteristic of Hokkien communities. This micro-level analysis, detailed in subsequent sections, is crucial for revealing the mechanisms of ‘Interpretive Malleability’ in action.

By adopting this multi-scale framework, this study transforms GIS from a descriptive tool into an analytical instrument, allowing the research to first map broad patterns and then ‘zoom in’ with rich ethnographic and historical data to explain the activation of a symbol’s unique potential.

Furthermore, to rigorously test the exceptionalism of ‘Interpretive Malleability,’ this study employs a dual comparative analysis, comprising both a synchronic contrast of Guan Di with other key deities (Mazu 媽祖, Guanyin 觀音, Datuk Gong 拿督公) and a diachronic exploration of his evolving personas. The diachronic lens, in turn, situates Guan Di’s trajectory alongside those of other foundational figures worldwide who have been similarly elevated into multifaceted symbols. While these global precedents point to the ‘Persistence of the Human Prototype,’ this study reframes this concept not as a monolithic mechanism, but as a spectrum of interpretive potential. The research then demonstrates that Guan Di’s symbolism occupies a uniquely potent position on this spectrum, characterized by a profound malleability that distinguishes it from other instantiations of the same underlying process. This analytical move enables the study to transcend mere typological comparison, facilitating an in-depth inquiry into the specific conditions that cultivate such exceptional symbolic resilience.

2.3. Theoretical Framework

Scholarship on Chinese religion in Malaysia has largely proceeded along two complementary paths: a historical approach tracing the ‘transplantation’ of social structures (Wang 1991; Yen 1986, pp. 35–40), and an ethnographic one detailing their subsequent ‘localization’ (Tan 2018; DeBernardi 2006). While powerfully illuminating the outcomes of adaptation, the analytical focus of these traditions often remains on external socio-cultural forces. Consequently, the cultural symbol itself is frequently treated as a passive receptacle, its own intrinsic properties that enable profound adaptability left largely unexamined. Yet, as anthropological work on Malaysian Hakka identity suggests, cultural persistence and change hinge on how communities actively and strategically interpret symbols to define themselves (Carstens 2005, pp. 101–27). This observation prompts this study’s central inquiry: what intrinsic qualities make a symbol like Guan Di so exceptionally potent and malleable for this process of creative, agentive interpretation within the Malaysian context?

To address this gap, this study proposes ‘Interpretive Malleability’ as its core analytical framework. This framework does not emerge from a vacuum; it draws significantly on and seeks to build upon existing scholarly work that illuminates the complex, adaptable, and historically layered nature of Guan Di’s symbolism. The concept of the ‘superscribed symbols’ is particularly pertinent, arguing that the meanings of potent symbols like Guan Di are not static but are formed and reformed through continuous historical interpretation and layering by different social actors. Crucially, this ‘superscribing’ theory also emphasizes a significant ‘path dependency’ in this evolutionary process: new ‘inscriptions’ of meaning occur within the constraints of existing historical discursive frameworks and memory carriers, allowing memory to demonstrate historical continuity even as it is ‘forged’ (Duara 1988). The construction and dissemination of Guan Di’s symbolic meaning often reveal a complex interplay between official power and folk practices. On one hand, as Watson (Watson 1985) observes in his discussion of the ‘standardization of deities,’ state power or cultural elites frequently attempt to unify and regulate diverse local deity worship. By promoting officially recognized narratives and rituals, they aim to shape a ‘standard’ image and ‘orthodox’ status for these deities. This perspective helps us understand the imperial enfeoffments and official sacrifices dedicated to Guan Di through various dynasties, reflecting deliberate efforts to sculpt his core symbolism around ‘loyalty and righteousness’. Ter Haar (2017)’s research, however, illuminates another dimension of belief emergence. He argues that the rise in Guan Di worship was not entirely driven by premeditated hero worship or official promotion but involved significant ‘contingency.’ In his view, oral culture—such as miracle stories and local legends spread by migrating populations—and ‘spontaneous diffusion’ among devotees played crucial roles in the faith’s initial construction. This outlook challenges traditional paradigms that may have overemphasized the decisive influence of official enfeoffment and elite literature in early belief formation, instead highlighting the original impetus of folk and spontaneous elements.

How, then, do these seemingly different, even tense, cultural layers coexist? Katz (2008)’s concept of ‘cogeneration,’ proposed in his research on The Cult of Marshal Wen (溫元帥信仰), offers a compelling explanation. He points out that a belief’s multiple cultural layers are not necessarily in a relationship of mutual replacement; in many cases, they can form and develop in parallel. Peng (2020)’s sociological analysis further corroborates this fusion of multiple forces. He emphasizes that Guan Di’s success as a popular deity lies not only in his ability to integrate diverse religious elements (Confucian, Buddhist, Daoist) and embody universal ethics, but also in the dynamic interaction between official recognition and popular worship within his cult. It is this interaction that allows Guan Di’s symbolism to effectively bridge the official and folk spheres, thereby gaining state-level reverence while simultaneously meeting the diverse needs of different social groups.

However, while existing frameworks adeptly explain the conditions that fostered his veneration, they do not fully elucidate the internal mechanisms that grant his symbolism such exceptional adaptability. Building upon these scholarly foundations, this study puts forth ‘Interpretive Malleability’ as the core analytical framework. This study defines it not merely as a static attribute, but as a dynamic, two-part mechanism that explains the enduring vitality and adaptability of Guan Di worship:

- (1)

- Inherent Potential: The Persistence of the Human Prototype. The first mechanism is the symbol’s ‘Inherent Potential’—a unique symbolic structure providing the rich ‘raw material’ for creative adaptation. Its primary engine is the ‘Persistence of the Human Prototype.’ Unlike deities whose perfected divine personas supersede their mortal origins, the historical, relatable, and morally complex figure of the human ‘Guan Yu’ is never fully erased. This enduring prototype creates a vast and fertile interpretive space between the flawed hero and the perfected sage-emperor, serving as the ultimate cognitive and emotional anchor that invites constant re-interpretation. In essence, the ‘persistence of the human prototype’ is the foundational reason why Guan Di’s symbolism is so polysemic and his narrative so open. It prevents the symbol from becoming a rigid, one-dimensional icon and instead maintains it as a dynamic, living narrative, furnishing his cult with a uniquely broad and resilient foundation for creative reinterpretation.

- (2)

- The Local Generative Process. The second mechanism is the ‘Local Generative Process.’ This process is activated when a ‘Generative Impetus’, an urgent functional or symbolic need within a local community, such as survival pressures, a crisis of trust, or identity anxiety, prompts local actors to creatively re-purpose the symbol’s inherent potential through a series of ‘Generative Mechanisms.’

It is this combination of inherent potential and a dynamic generative process that grants Guan Di his remarkable uniqueness, setting him apart from other deities. With this theoretical framework established, the following sections will employ this lens to analyze the specific manifestations of Guan Di’s Interpretive Malleability across different historical, cultural, and geographical contexts.

The concept of ‘the persistence of the human prototype’ also deepens the dialogue with broader theories of deification. It refines the classical model of Euhemerism, which often posits a linear process where a perfected divine persona substitutes and erases its complex human origin (Bulfinch 1867). In contrast, this framework argues for a dynamic co-existence. The human ‘Guan Yu’ is not a mere historical footnote but a perpetually accessible anchor for interpretation. This explains why his cult can simultaneously generate profound reverence and irreconcilable conflict. This concept also extends the Cognitive Science of Religion’s (CSR) theory of Minimally Counterintuitive Concepts (MCI). While the idea of a deified general is cognitively ‘sticky’ and easily transmitted (Boyer 2007), MCI theory primarily explains cultural transmission, not the profound interpretive generativity of a specific cult. The ‘persistence of the human prototype’ fills this gap by demonstrating that it is the rich, morally complex, and deeply human narrative, rather than just a simple counterintuitive tag, that provides the vast raw material for creative re-purposing.

This also helps explain why other historical figures, who might also possess complex human backstories, did not achieve the same level of adaptive success. They may have possessed a similar latent potential but missed the crucial ‘historical tailwind’ of the specific alignment of social, economic, and political pressures that propelled Guan Di’s cult to prominence. The ‘Interpretive Malleability’ of Guan Di was thus not merely an unfolding of its immanent nature. Instead, it was a dynamic process forged in the crucible of history, where symbolic structure met historical necessity.

3. Manifestations of Malleability: Comparative Studies

3.1. Exotic Imagination and Local Re-Creation

Guan Di’s image and associated narratives have a long history of dissemination, encompassing diverse interpretive dimensions far beyond their original Chinese cultural matrix. The cross-cultural journey of Guan Di worship powerfully illustrates this dynamic. These interactions, often filled with ‘creative misreadings’ and ‘proactive re-creations,’ attest to the remarkable elasticity of his symbolism. However, such imaginative engagement only deepens into systematic ‘appropriation’ when driven by a strong local impetus.

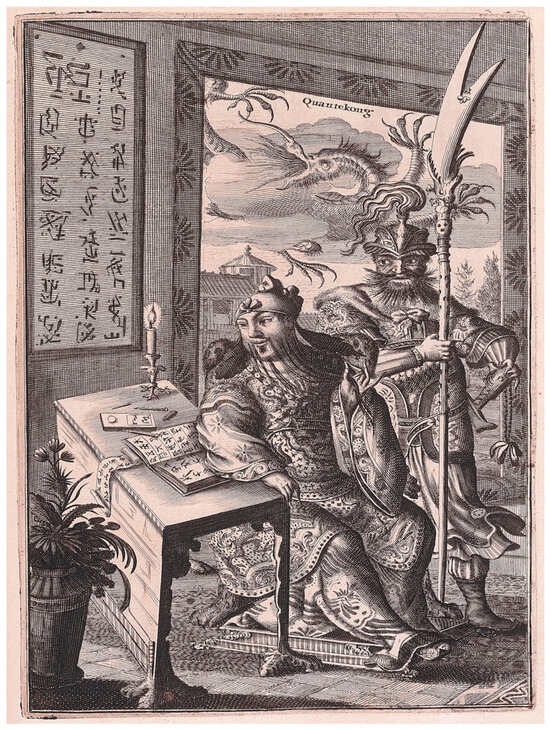

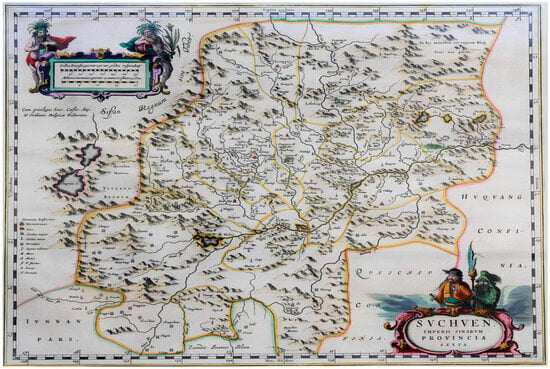

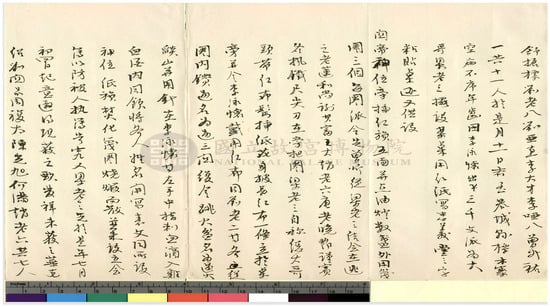

In Europe, this re-articulation was driven by a symbolic need to comprehend a distant and mysterious ‘Orient’. For instance, the 17th-century Dutch writer Olfert Dapper, based on second-hand accounts, performed a thorough functional reconstruction. In his influential yet imaginative ‘Image of Guan Di Gong Reading at Night (關公夜讀圖)’ by Figure 4, he ‘filled’ the symbolic vacuum of a Chinese founder by conflating Guan Di into a composite figure embodying ‘Vitey’ (黃帝) and ‘Tzintzon’ (秦始皇).4 Furthermore, in the authoritative Novus Atlas Sinensis, a visual re-imagining occurred (Martini 1655), where the cartouche of the Sichuan province map prominently features Guan Di, rendered in a European Baroque style (Figure 5). Even earlier, the late 16th-century Spanish Boxer Codex demonstrated a more subtle mechanism: cultural analogy. To meet the need for local comprehension, its Spanish text initiated a crucial semantic shift by drawing an analogy between Guan Di and Saint James, a military saint familiar to Western readers.5 Together, these works reveal the complex processes by which a potent cultural symbol is perceived and reinterpreted in early global encounters.

Figure 4.

Olfert Dapper. 1670 Quan tekong. ©National Museum of Taiwan History. Reproduced from Weng (2001).

Figure 5.

Martini, Martino, Suchuen, Imperii Sinarum Provincia Sexta. Reproduced from Amsterdam: Joh. Blaeu, 1655. Call Number: MAP Ra 300 Plate 7.

This phenomenal level of reshaping stands in stark contrast to the Western perception of another important deity from the same period, the sea goddess Mazu. Although Western documents record various transliterations of Mazu’s name, her core identity as a maritime protector was consistently recognized. People rarely see the kind of functional reconstruction applied to Mazu.6 This significant difference in reception indirectly highlights the remarkable complexity and polysemy inherent in Guan Di’s symbolic system.

Within the East Asian cultural sphere, this adaptive re-articulation was driven by more specific religious and political needs. In Japan, at ‘Manpuku-ji (萬福寺)’, a case of symbolic subsumption occurred. The need was to define the role of a three-eyed deity within the temple. This need was met by ‘filling’ the role with Guan Di, who had already absorbed the functions of the declining deity Hua Guang Da Di (華光大帝) to become the preeminent ‘Sangharama (伽藍菩薩)’. The monk ‘Muju Dōchū (無著道忠)’ recorded this identification in his Zenrin Shōkisen (禪林象器笺), despite significant iconographic deviations.7

Similarly, in Korea’s Chosŏn Dynasty, a political recalibration of the deity occurred, driven by the need to strengthen royal authority. Monarchs, particularly from the reign of ‘King Yŏngjo’ onwards, portrayed ‘Kwanje’ (Guan Di) in royal Korean regalia, such as a ‘dragon robe’ and an ‘iksŏngwan’ (winged coronet). This ‘regal portrayal’ was a perfect illustration of his ‘flexible iconography’ being strategically ‘re-calibrated’ to ‘fill’ a political function (Lee 2020).

While these cases show symbolic recalibration and subsumption, the modern Korean emerging religion, Jeungsanism (甑山教), offers an even more extreme example of systematic appropriation that deepens our understanding of ‘Interpretive Malleability’. As documented by scholar Kim Tak, this case reveals the framework’s mechanics when activated by a prophetic founder’s ultimate ‘Generative Impetus’: the creation of a new religious cosmology.

In this new theological system, the founder Jeungsan instrumentalizes Guan Di in a manner far beyond simple reinterpretation. He employs ultimate ‘Generative Mechanisms’ by systematically subordinating Guan Di to the rank of a subordinate general who serves Jeungsan’s own cosmic ‘public works’. This demotion is so absolute that Jeungsan claims the authority to dispatch Guan Di’s spirit to the West to start World War I, using him as a direct tool. Jeungsan’s creative authority is further asserted through his authoring of a powerful and unique chant, the ‘Chant of Yun-jang’ (雲長咒), and his ultimate demonstration of dominance by changing his own face into that of Guan Di.8

This complete appropriation was possible because the symbol’s ‘Inherent Potential’, Guan Di’s non-absolute divinity rooted in the ‘Persistence of the Human Prototype’, made him uniquely susceptible to subordination within a new pantheon. Thus, the Jeungsanism case serves as a profound supplement to our understanding, showcasing the furthest limits of ‘Interpretive Malleability’ by moving beyond syncretism into a model of complete theological instrumentalization driven by a prophetic founder.

If the adaptations in East Asia show appropriation within a shared cultural matrix, the most radical expression of ‘Interpretive Malleability’ is found in the crucible of New World diasporic communities. This adaptive re-articulation is found most notably in Cuba, a setting that shares a striking historical parallel with Malaya. Both regions witnessed a massive influx of Chinese migrants during the mid-to-late 19th century, a period of intense social formation under colonial economies.

It was in this crucible of cultural encounter that Guan Gong underwent a profound transformation in Cuba, resulting in the syncretic figure of ‘San Fancón’ (Gregor and Yang 2014). This triple fusion of Chinese, Catholic, and African traditions creates a profound tension, as the process involved a fundamental recharacterization that stands in stark contrast to Guan Gong’s original persona. In Cuba, San Fancón is described as a warrior, but also ‘a great talker, a womanizer, a boaster, a good friend, fond of partying, red wine, and apples,’ traits borrowed directly from the vibrant and tempestuous African Orisha, Changó. This personality is in direct opposition to the traditional image of Guan Yu, a paragon of Confucian virtues embodying solemn righteousness, loyalty, and unwavering gravity.

While other major transnational deities like Guanyin and Mazu also undergo syncretism, their transformations often follow a clearer path of functional analogy. Likewise, in Cuba, Guanyin merged with the Virgin Mary and the African Orisha Ochún, both figures of feminine compassion. Similarly, Mazu, the protector of seafarers, is often identified with Stella Maris (Star of the Sea), a maritime aspect of the Virgin Mary. In stark contrast, the transformation of Guan Gong into ‘San Fancón’—a new entity absorbed into a different mythological system and given a personality that subverts his original moral core—represents a more profound level of symbolic absorption and reconfiguration. This case powerfully demonstrates how the open structure of Guan Di’s symbolism can accommodate and integrate even radically different cultural inputs, a process that goes far beyond simple analogy or functional substitution.

3.2. Localization in Comparison

While the Cuban case highlights extreme malleability, comparing Guan Di with other deities in Malaysia reveals the specific social and cultural domains where his distinctiveness truly lies.

Jia and Li (2018) proposed a three-stage model for Guan Di worship in Southeast Asia: ‘family, community, and supra-community.’ While valuable, this focus on diffusion patterns, like other surveys of key temples and texts, may not fully capture the source of his distinctiveness.9 This study argues that Guan Di’s uniqueness lies not in a generic pattern of expansion, but in how his presence extends beyond the conventional domains of temples and household altars into an exceptional breadth of institutional and cultural spheres:

Guan Di’s influence permeates a unique spectrum of social spheres, demonstrating his exceptional interpretive malleability. He is a central figure in traditional ‘Kongsi’ (公司) and sworn brotherhoods (‘Koo Saing Wooi Koon’ 劉關張趙古城會; Figure 6), and his influence also extends to modern religious movements. In this domain, he holds a core position within the ‘Church of Virtue’ (德教会), a prominent syncretic religion harmonizing the ‘Five Teachings’. Furthermore, he has become the central figure for secular organizations like the MIGGCF Promotion Center, which frames him as a transnational cultural symbol. The MIGGCF’s sustained success and its unique model of rotational hosting across Southeast Asia represent a phenomenon rarely seen for other deity cults. This pervasive capacity to bridge diverse social and cultural domains offers a unique insight into his potential for symbolic abstraction and universalization (Gao 2020). Beyond the religious and secular, he is deeply embedded in folk-art and martial subcultures, widely venerated by countless ‘lion dance troupes’ (醒獅團). A prime example is the multiple-time world champion ‘Kun Seng Keng Lion & Dragon Dance Association’ (關聖宮龍獅團), for whom Guan Di serves as a patron saint embodying the martial virtue and righteous solidarity essential to their discipline. It is this exceptional capacity for institutional and cultural penetration that the present study seeks to explain.

Figure 6.

The Balik Pulau Koo Saing Wooi Koon. Image by author.

To test the exceptionality of Guan Di’s malleability, the most potent local comparison is with the ‘Datuk Gong’, a ubiquitous deity in Malaysia and a prime example of religious syncretism. As scholarly work by Wang and others has shown, the Datuk Gong cult is a dynamic fusion of Malay ‘keramat’ (sacred place/spirit) worship and Chinese ‘Tudi Shen’ (土地神) concepts. Its adaptability is undeniable, evolving to encompass various ethnicities, genders, and ritual forms, becoming a quintessential symbol of Malaysian Chinese identity (Wang 2022; Wang et al. 2020). More than just a syncretic phenomenon, ‘worshipping the Other’ in the form of the Datuk Gong carries multiple layers of meaning for Malaysian Chinese communities.

However, the malleability of Datuk Gong operates within a fundamentally different paradigm. At its core, the Datuk Gong is a territorial deity, a spirit whose authority is intrinsically anchored to a specific locality—a piece of land, a tree, a village, or a construction site. His function, though syncretic, is ultimately defined by his role as the guardian of that place. As Wang notes in his field research, a local village chief explained that: “the Datuk Gong manages our village, and he cannot cross the border.” The adaptability of the Datuk Gong cult, therefore, is best conceptualized as a ‘deepening of localization’: it modifies the identity of the local spirit to fit the multi-ethnic landscape, but its core function remains steadfastly tied to the land.

In stark contrast, Guan Di’s ‘Interpretive Malleability’ is characterized by a ‘transcending of functions’. His symbolic power is not anchored to any piece of land but to a portable, universalizable narrative of loyalty, righteousness, and brotherhood. This allows his symbol to be detached from any specific location and be reprogrammed for entirely different social and even abstract domains. This is reflected in his diverse roles, iconography, and nomenclature. His image can shift from a martial god to a civil scholar reading the Spring and Autumn Annals, and his titles range from the ‘imperial’ to the deeply personal and geographical, such as ‘Shan Xi Fu Zi’ (山西夫子), a name found on incense pouches carried by early immigrants.

This uniqueness is further underscored when Guan Di is compared with other deified historical figures prevalent among Chinese communities in Malaysia. For instance, the worship of ‘Lu Ban’ (魯班), the patron saint of craftsmen, remains largely confined to the sphere of artisans, his persona and functions steadfastly anchored to his historical role. Similarly, while other heroes from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, like ‘Zhao Zilong’ (趙子龍) and ‘Zhou Cang’ (周倉), are also venerated in their own temples across the peninsula, their images and narratives consistently adhere to the original epic. They are revered as the historical heroes they were, but they have not evolved into a multifaceted ‘Di’ (Emperor) capable of transcending their original context in the way Guan Yu has. It is precisely this capacity to transcend his historical origins and functional specificity that distinguishes Guan Di. The exceptional malleability of his symbolism, therefore, is not a universal trait of all deified figures but a unique structural property of his cult.

Having established his unique functional transcendence in comparison to other deities, this study now turns to a specific historical case—the secret societies—to examine how this malleability was applied in high-stakes practice.

3.3. The Secret Society Nexus

In the conflict-ridden social landscape of late imperial China, particularly in its southeastern regions, secret societies like the Tiandihui had already forged a powerful model for social mobilization. Amid rising social conflicts in late Qing China, especially prevalent clan conflicts and secret society activities in Fujian and Guangdong, Guan Di’s narrative of ‘sworn brotherhood among different surnames’ provided a powerful cultural template for ‘ritual kinship’ (Leyton 2018).

This model drew from a deep cultural repertoire, among which the epic Romance of the Three Kingdoms held a foundational impact. Its narrative of ‘loyalty and righteousness’ provided a potent moral and ethical framework for these societies. As Liu (2025) points out, Southeast Asian communities often ‘select what they need’ and ‘adapt for their own use’ when receiving ‘Chinese stories’, a process clearly evident in the secret societies’ engagement with the epic. The story of the ‘Oath of the Peach Garden’ (桃園結義), in particular, offered a sacred prototype for ‘ritual kinship’. This prototype was especially resonant for the many immigrants from these same feuding regions.

The study of these societies relies heavily on a combination of historical records from China and later observations in Malaya. Collectively, these sources confirm the existence of a highly symbolic and flexible ritual practice aimed at transforming literary narratives into living reality.10 These initiation ceremonies are not simple replications of traditional temple worship, but are creatively reinvented to serve the specific needs of a secretive, hierarchical organization. Rituals such as the symbolic crossing of the door, the jumping of the fire plate, and the drinking of blood wine are all designed to create a sacred, solemn atmosphere and forge an unbreakable brotherhood. Irrefutable historical evidence points to the centrality of Guan Di and the ‘Peach Garden’ narrative in these rituals. Official Qing Dynasty records, for instance, such as a minister’s report from 1817, explicitly mention the ‘Hall of Loyalty’ (忠義堂) and the ‘Spirit Tablet of Guan Di’ in connection with secret society activities (Figure 7). Even more compelling is the direct textual proof from within the societies themselves, exemplified by a sworn oath document from Tiandihui leader Lu Shenghai (盧盛海) in 1806, housed in the First Historical Archives of China. The oath’s declaration, ‘Since ancient times, none has surpassed Lord Guan in possessing both loyalty and righteousness’, positions Guan Di as the ultimate paragon of the society’s core values.11 Crucially, the line, ‘Tracing back to the Oath of the Peach Garden, brothers are no different from siblings born of the same parents’, explicitly invokes the narrative to construct a ‘fictive kinship’ that transcends blood ties. This invocation was not a rigid dogma; its spiritual core of ‘sworn brotherhood among different surnames’ (異姓結拜) and ‘sharing life and death’ (生死與共) possessed high malleability, allowing it to be translated into concrete mutual aid that addressed the basic survival needs of its members.

Figure 7.

Reproduced from Taipei, National Palace Museum, Box no. 2751; Packet 37, no. 53908, dated the 21st day of the 4th month of the 22nd year of the Jiaqing reign. ©National Palace Museum.

These historical accounts reveal a deep connection between the polysemy of Guandi’s beliefs and the mobilization strategy of the pragmatism of the secret society. These societies demonstrated a highly pragmatic strategy by flexibly activating Guan Di’s dual persona: his ‘martial valor’ was highlighted as a spiritual weapon during external conflicts, while his ethical symbolism of ‘loyalty and righteousness’ was emphasized to enforce internal discipline and cohesion.

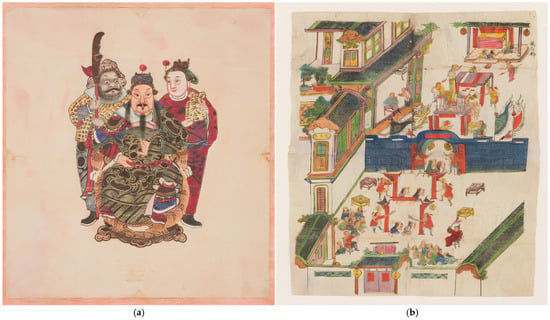

Once transplanted to Malaya, this cultural template was not just replicated but intensified. In the lawless frontier society, driven by fierce secular strife over resources like tin mines, the secret societies such as the Ghee Hin (義興公司, meaning ‘Rise of Righteousness’) and Hai San became the de facto governing powers.12 Material culture also provides corroborating evidence, such as the watercolors from the National Museum of Singapore (Figure 8), which depict Guan Di’s statue as the focal point of Tiandihui and Ghee Hin Kongsi initiation ceremonies.

Figure 8.

(a) Illustration of Guan Di used in Tiandihui initiation ceremony (Accession No.: 1996-02824); ©National Museum of Singapore. (b) Illustration of Ghee Hin Kongsi Lodge (Accession No.: 1996-02889). ©National Museum of Singapore.

The deep connection between Guan Di’s polysemic symbolism and the societies’ pragmatic mobilization strategies is most evident in their selective activation of his persona, a duality that reached its dramatic climax in the Larut Wars (拉律戰爭). The conflict between the Hai San and Ghee Hin societies starkly highlights the complexities and tensions inherent in applying ‘Interpretive Malleability’. On one hand, this very malleability enabled each group to flexibly utilize Guan Di’s symbolism for their own organizational needs. On the other hand, the same adaptive quality meant that in the face of fundamental conflicts of interest, the shared symbol was not enough to bridge the divide. As Ong points out, although the Tiandihui system revered Guan Di, its core objects of worship were actually the ‘Five Ancestors.’ Guan Di was more strategically used as a model deity emphasizing the value of loyalty and righteousness, which explains the phenomenon of these organizations accepting imperial titles from the Qing court while still maintaining their internal narratives.13

Furthermore, the syncretic nature of secret society rituals, drawing from diverse cultural wellsprings in their homeland, also found expression in the Malayan context. The interplay between Cantonese opera traditions and Tiandihui rituals, for example, illustrates this fusion. As documented by scholars (Mai 1940; Xiao 1969), initiates in certain Tiandihui ceremonies, when asked about the symbolic boat they journeyed on to attend the ritual, were required to name the deities enshrined on board: Hua Guang Da Di (the patron deity of opera performers) at the bow, Tian Hou (天後, the Empress of Heaven, patroness of seafarers) at the stern, and Guan Di in the cabin. The absence of this specific questioning in earlier Tiandihui ritual pamphlets indicates the probable later integration of Cantonese opera traditions, a syncretic development that likely migrated with its practitioners to Malaya. In this new context, the society’s symbolic repertoire expanded further. The inclusion of Guan Di, the archetypal martial saint, alongside highly localized deities, demonstrates a sophisticated mechanism for symbolic bricolage: the capacity to weave together diverse symbolic resources to address new social realities. This mechanism is crucial for understanding the social cohesion of specific immigrant groups, such as the Huizhou Hakka, from which the influential leader Yap Ah Loy (葉亞來) emerged. Their case illustrates how a flexible symbolic framework, centered on figures like Guan Di, was instrumental in forging a collective identity.

Antony’s research on the 1802 Tiandihui uprising in Huizhou, Guangdong, for instance, suggests these Hakka communities were already deeply immersed in secret society cultures and their syncretic ritual practices in their homeland.14 Indeed, fieldwork for the current study confirms that the Sin Sze Si Ya Temple in Kuala Lumpur, a prominent site with strong Hakka and Yap Ah Loy connections, continues to enshrine Hua Guang Da Di, Tian Hou, and Guan Di together, indicating a continuity of these syncretic and adaptive ritual practices. Furthermore, fieldwork at the Sin Sze Si Ya Temple in Kuala Lumpur led to the discovery of a spirit tablet inscribed with ‘Spirit Tablet for the Departed Souls of the Imperial Qing’s Righteous and Brave’ (皇清義勇列位先靈). The unearthing of this tablet offers fresh insight into the temple’s intricate symbolic system, where the term ‘Imperial Qing’ indicates a connection to the Qing Dynasty, while ‘Righteous and Brave’ directly extols virtues of loyalty and martial valor.

In the turbulent social milieu of 19th-century Malaya, particularly within the context of Chinese secret societies, the veneration of such loyal and courageous sacrifice found strong resonance with the core virtues embodied by Guan Di, notably loyalty, righteousness, and valor, and with the martial ethos and ideals of collective struggle championed by these societies. This tablet likely served to enshrine and memorialize individuals or groups who displayed martial valor and sacrifice akin to those associated with Guan Di. This observation lends further credence to the strategy in early Kuala Lumpur, shaped by prominent figures like Yap Ah Loy, where religious sites were instrumental in integrating diverse symbolic resources to consolidate the community and project an image of martial prowess.

Conflicts between societies such as Hai San and Ghee Hin, therefore, starkly highlight the complexities and tensions inherent in applying Guan Di worship’s ‘Interpretive Malleability.’ When faced with intense economic and social pressures, particularly fundamental conflicts of material interest, the cohesive power of faith reveals its limits, as even a shared sacred connection can be temporarily suspended or reinterpreted to serve immediate needs. This further underscores that understanding the social functions of religious belief in specific historical contexts requires examining it within concrete power relations, economic structures, and social contradictions, rather than merely focusing on a static analysis of doctrines or symbols themselves. This tension points to a deeper paradox in the application of Guan Di’s symbolism, one best understood through the lens of group conflict. Guan Di, the quintessential symbol of martial prowess and sworn brotherhood, would logically be the ultimate spiritual patron for warfare.

While Guan Di is revered as the God of War, his divine authority paradoxically recedes in the very context of actual warfare. In the endemic armed conflicts between lineages or villages (鄉村宗族械鬥) of his followers’ homelands, his role as a martial protector was ironically suspended. Zhang (2023)’s research on these ‘classified conflicts’ illustrates how folk religion was instrumentalized for mobilization, a function that demanded exclusive, not universal, symbols. In a conflict requiring an absolute demarcation between ‘us’ and ‘them,’ a universally revered deity like Guan Di loses his utility as an exclusive banner. His role as a god of brotherhood is eclipsed by the immediate need for a god that is only our god. This void was filled by fiercely local patron deities such as Kai Zhang Sheng Wang (開漳聖王) for immigrants from Zhangzhou or the Three Mountains Kings (三山國王) for many Hakka communities who could effectively unify a specific group and sanctify its struggle against rivals. Therefore, Guan Di’s ‘functional retreat’ from these localized quarrels is not a sign of weakness but the ultimate testament to his trans-local strength. His universal appeal, the very quality that made him unsuitable for small-scale, exclusive conflicts, was precisely what rendered him the ideal ‘maximum common denominator’ for large-scale, inclusive organizations like the secret societies in Malaya. This ability to transcend hyperlocal identities, even at the cost of receding in certain contexts, powerfully demonstrates the most profound dimension of his ‘Interpretive Malleability’.

Ultimately, the secret societies’ engagement with Guan Di, from ritual re-enactments of the Peach Garden Oath to the selective activation of his dual persona and his strategic deployment alongside local deities, vividly illustrates ‘Interpretive Malleability’ in action. The intense ‘symbolic need’ for survival and cohesion in Malaya’s frontier society served as the generative impetus, activating a series of creative cultural adaptations. Narratives from Romance of the Three Kingdoms were mobilized to forge social trust; Guan Di’s polysemous symbolism was deployed to reconcile the dual demands of internal order and external conflict; and his universal appeal was used to carve out a niche within a complex local pantheon. The history of Guan Di worship within these societies is thus not a simple story of transplantation, but a testament to how a symbol’s inherent plasticity, when catalyzed by urgent social demands, generates profoundly resilient cultural forms.

This complex deployment of Guan Di’s symbolism reveals how his malleability operates under pressure. The final section, therefore, will dissect the foundational structure of his symbolic system to understand why it possesses such unique potential.

3.4. The Persistence of the Human Prototype

The preceding analyses have demonstrated the exceptional scope of Guan Di’s malleability. This section delves into the foundational reason for it: a unique cognitive structure within his cult that this study terms ‘the persistence of the human prototype’. This contrasts sharply with the ‘substitutive deification’ process often seen in the worship of other major deities among Chinese devotees, most notably Guanyin and Mazu. While their pre-deification identities, such as Princess ‘Miao Shan’ (妙善) or ‘Lin Mo’ (林默), serve as foundational origin myths, they are largely superseded in worship by the ultimate, perfected divine persona—the compassionate goddess or the Empress of Heaven. The tension between their human origins and divine status is resolved through a process of substitution.

In the case of Guanyin, while her origins are rooted in the male bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, her extensive process of Sinicization involved a fundamental transformation into a female deity, epitomized by the popular legend of Princess Miao Shan. As scholars like Li (Li 2008) have extensively documented, this transformation was so thorough that the original male prototype was almost entirely superseded in popular Chinese worship. Similarly, while ‘Mazu’ worship also undergoes significant localization as it spreads internationally, her image and practices adapting to various cultural contexts (Zhang et al. 2024), the fundamental nature of her core symbolism as a maritime protector typically shows greater stability. The deification of these goddesses typically involves a process where their perfected divine personas supersede their human origins, leading to a relatively smooth and universal appeal that rarely incites deep-seated historical antagonism.

The trajectory of Guan Di worship, however, is far more complex, and its universalization is not without limits or contestation. The boundaries of his ‘Interpretive Malleability’ are vividly illustrated by cases of both active exclusion from without and principled resistance from within.

A telling example of external exclusion is the town of ‘Lücheng’ (呂城) in China. This animosity is vividly reflected in local lore, as documented in the ‘Zhiyi’ (摭遺) section of the Guangxu Danyang county annals (光緒丹陽縣誌).15 During the Qing dynasty, a period of nationwide proliferation of Guan Di temples, Lücheng famously refused to build one. For its residents, their local hero is Lü Meng (呂蒙), the general who defeated and executed Guan Yu. For these inhabitants, and for others who claim descent from ‘Yan Liang’ (顏良), another general slain by Guan Yu, Guan Di is not a universal protector but the historical enemy of their ancestors and local patron. This ‘active exclusion based on historical grievances’ demonstrates how local history and pre-existing belief networks can erect firm boundaries against even the most powerful of symbols. Simultaneously, a case of internal resistance is found in the stele inscription titled ‘Record of the Reconstruction of the Temple of Marquis Guan’ (重修關侯廟碑記) from Luoning, Henan, dated to the Qianlong reign. The author expresses profound dissatisfaction with the contemporary trend of elevating Guan Yu from a marquis (侯) to an emperor (帝). He critiques this as an act of impropriety that ‘improperly elevates a subordinate (Guan Yu) to the same level as his sovereign, Emperor Zhaolie, and his heir.’ (使侯上擬於昭烈父子) and dismisses popular legends about Guan Di’s divine status as ‘superstitious tales of ghosts and marvels.’ (說鬼而言怪) (Wang 2016). This ‘active resistance from within’, rooted in orthodox Confucian ritual principles, is a powerful testament to the ‘Persistence of the Human Prototype’. The author’s insistence on the title ‘Marquis Guan’ shows that the historical, human identity of Guan Yu as a loyal subject was so tenacious that it resisted even imperial attempts at full deification.

Taken together, these two cases of contestation, one from rival communities and one from a Confucian purist, underscore the profound paradoxes of Guan Di’s worship. They highlight a crucial distinction from the cults of Guanyin and Mazu, whose narratives seldom generate such irreconcilable historical conflicts. The very existence of such exceptions reveals the unique, often contested, nature of Guan Di’s ‘Interpretive Malleability’, a quality defined as much by its tensions and boundaries as by its flexibility.

The exceptional malleability of Guan Di is fueled by unique structural properties within his symbolic system, beginning with his very origins. The Guan Di symbol itself carries rich, even contradictory, meanings. This polysemy provides the foundation for different groups to selectively interpret based on their needs. As some scholars suggest, Guan Di’s worship may stem from early fierce ghost (祀厲) propitiation, notably linked to post-mortem plagues in Jingzhou (荊州), reflecting a hungry ghost belief (血食崇拜) aimed at averting disaster rather than seeking blessings (Zheng 1994; Xu 1999). While this early form of worship has been almost entirely superseded by his later, more benevolent personas, its historical trace contributes to the vast spectrum of his symbolic identity. This identity can be conceptualized as a spectrum bookended by two opposing poles: at one end lies this historical layer of a feared, demonic entity, and at the other stands the revered imperial sage-emperor, a perfected figure shaped by centuries of Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist interventions. The immense tension between these two poles—the demonic and the divine—creates an unparalleled interpretive field. Crucially, it is the historical personage of ‘Guan Yu’ that occupies the vast and fertile middle ground of this spectrum. He is neither purely a ghost to be feared nor a perfect god to be worshipped from a distance. Instead, as a figure marked by both celebrated virtues and tragic flaws, he serves as the stable, relatable median in this symbolic continuum.

This unique structure is what this study terms ‘the persistence of the human prototype’. Guan Di’s deification is ‘additive’, not substitutive, because the human prototype ‘Guan Yu’ is never erased; it persists as the cognitive anchor and the primary point of access for devotees. This allows for a remarkable flexibility of engagement: believers can move up the spectrum to connect with his divine power, or move down to identify with his human drama and moral complexities. This capacity to navigate between the poles of ghost and deity, with the historical hero as the enduring mediator, is a distinctive mechanism that furnishes his cult with a uniquely broad and resilient foundation for creative reinterpretation.

This concept of a ‘human prototype’ finds compelling ethnographic expression in the religious life of rural India, where anthropologist Bhrigupati Singh (2015) reveals a world in which deities are not remote sovereigns but intimate, and often contentious, partners. This dynamic relationship, rooted in the perceived humanity of the sacred, mirrors the very mechanisms that enable a symbol’s malleability. In Singh’s ethnography, where villagers can argue with their gods over sacrificial terms (“Baba…we won’t give a goat…Eat us if you must”), make demands during rituals (“You better do my work!”), and even compel a divine appearance through their own ascetic efforts (“Now he will have to come”) (Singh 2015, pp. 46, 48, 61).16

Crucially, these actions are a vivid embodiment of the ‘Local Generative Process.’ Driven by a ‘Generative Impetus’, such as an existential crisis (rooted in economic hardship and resource scarcity), villagers are not passive recipients of divine will. Instead, they actively employ their own moral reasoning and ritual technologies to activate the negotiable and arguable aspects of the deity’s ‘human prototype,’ thereby shaping the terms of human-divine engagement. This Indian case vividly illustrates the core principle: the potency of a ‘human prototype’ lies not in its perfection but in its capacity for a dynamic, human-like relationship. This same principle is central to understanding the enduring power of Guan Di.

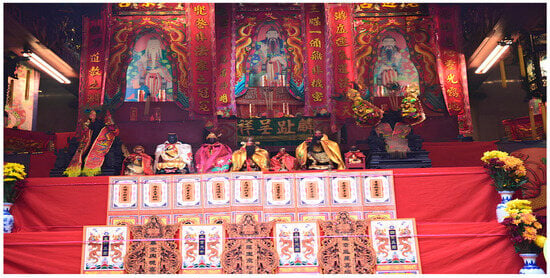

My fieldwork revealed a striking pattern. Whenever I asked devotees and temple committee members why they worship Guan Di, their responses consistently bypassed abstract theology or discussions of his origins as a fierce ghost. Instead, they told me stories. They spoke of the flesh-and-blood ‘Guan Yu’ from Romance of the Three Kingdoms, recounting his deeds and virtues. Their primary point of emotional and psychological connection was clearly with this relatable, albeit extraordinary, historical figure, not with a distant, perfected deity. This lived experience demonstrates that for his followers, Guan Di’s power is rooted in his compelling humanity.

It is precisely this grounding in a relatable human prototype that affords the faith its remarkable structural flexibility, a quality that manifests directly in its ritual practices. The ritual practices of Guan Di worship exhibit rich forms, inheriting traditions while constantly adapting. The Guan Di birthday celebration is the most important annual worship activity (Table 3), usually the time when the cohesion of the temple or related community is strongest. However, the specific date varies among different communities and temples, mainly falling on the 13th day of the 5th lunar month and the 24th day of the 6th lunar month, with the latter being the mainstream. This ‘dual birthday’ phenomenon is not mere historical confusion. The coexistence and general acceptance of these two dates within the Malaysian Chinese community precisely reflect key characteristics of traditional Chinese belief: syncretism, inclusivity, and flexibility (Feuchtwang 2010). As research on the logic of folk religious practices points out, folk beliefs often follow an operational logic different from institutional religions, emphasizing the proper execution of ritual actions and their effects, rather than unified doctrines or historical explanations. Such pragmatism, which prizes ritual efficacy over doctrinal correctness, lies at the utilitarian core of the belief system: as long as the ritual successfully unifies the community and delivers the expected sacred effects, its specific date and form become highly flexible.

Table 3.

Examples of Guan Di Worship Spaces on the West Coast.

The enduring power of this human prototype finds its ultimate expression in the secular realm of popular culture, where his image is continuously reinterpreted through video games and merchandise. Strikingly, these modern forms often present him not as the divine ‘Guan Di’ but as the historical ‘Guan Yu’. This ‘return’ to his human persona is distinct from other deities like Mazu or the Monkey King (孫悟空), whose popular representations typically rely on their divine myths. Guan Yu’s appeal, in contrast, stems from his rich human drama, allowing for a secular engagement that makes him accessible to a global, non-devotee audience. This demonstrates the ultimate form of his malleability: the capacity to strip away the divine and re-engage with the potent human narrative at his core.

Therefore, ‘Interpretive Malleability,’ as delineated in this section, is not intended to supplant the important theoretical contributions of previous scholarship. Rather, it builds upon them by opening the ‘black box’ of the symbol itself. Through a multi-layered comparative framework, this study has systematically demonstrated that Guan Di’s malleability is exceptional in both nature and degree. This study has argued that its engine is ‘the persistence of the human prototype’—a unique cognitive structure creating a vast psychological space for identification. However, a symbol’s potential is only actualized when it meets the specific demands of a community in a particular place and time. Therefore, this study now pivots from the symbolic structure to the social ground. The following analysis of the West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia will explore the spatial logic and social practices through which this malleability was put into action, shaping the contemporary religious landscape.

4. Spatial Logic and Social Practice: A GIS-Grounded Ethnography of the West Coast

At first glance, a Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis of Guan Di worship on the West Coast reveals a predictable, almost universal pattern for a diasporic faith: its distribution follows the currents of migration, concentrates around nodes of economic activity, and aligns with the development of natural resources and infrastructure. The clustering of temples in historic ports, tin-rich hinterlands, and along modern transportation arteries confirms that, at a macro level, the faith’s spatial logic mirrors that of many other deities, tracking the footsteps of its community.

However, it is precisely this seeming ordinariness that makes the GIS analysis a powerful and indispensable tool for this study. Rather than using it to prove the uniqueness of Guan Di’s distribution, this section employs GIS to establish a common ground—a cartographic baseline of settlement and economic history.

This section, therefore, employs the macro-meso-micro framework inspired by settlement geography to move from spatial patterns to social practices. Specifically, this section will investigate how two key networks—those led by Hakka miners and those by Hokkien merchants and their associated mediums (乩童)—activated different facets of Guan Di’s symbolism within these shared geographic zones. By examining the calculated inclusion of Guan Di in Hakka-led Sin Sze Si Ya temples as a potential form of ‘simulated kinship’, and by tracing the economic–ritual expansion of Hokkien fenxiang networks, this analysis aims to demonstrate how divergent social needs and practices can create distinct ‘maps of meaning’ upon a common geographical canvas.

4.1. The Common Ground: Spatial Logic of a Diasporic Faith

The spatial distribution of Guan Di worship sites reveals a clear and deliberate logic, rather than a random scattering. Quantitative analysis confirms a significant geographical imbalance. The calculated Gini coefficient of 0.5289 indicates a high degree of spatial concentration, moving significantly beyond a moderate imbalance and pointing towards a structured, non-arbitrary pattern. This is further visualized by the Lorenz Curve (Figure 9a), which starkly illustrates this disparity: the curve’s deep bow away from the line of perfect equality demonstrates that a small number of states command a disproportionately large share of these cultural landmarks. Specifically, the data shows that the top three states, Selangor, Penang, and Perak, which constitute only 25% of the regions studied (3 out of 12), collectively host approximately 53% of all documented worship sites (47 out of 89). This concentration is not merely a statistical curiosity; it is a geographical fingerprint of Malaysian history and socio-economic development. The high Gini coefficient and the skewed Lorenz Curve are more than just metrics of spatial inequality. They are quantitative expressions of a socio-historical narrative. The clustering of Guan Di worship sites is a map of the Chinese diaspora’s journey in Malaysia, charting its initial points of arrival, its economic endeavors, and its enduring community strongholds. The pattern is ‘deliberate’, not by a central plan, but as the cumulative result of generations of community-building in specific, historically significant locations.

Figure 9.

(a) The Lorenz Curve of the Distribution of Guan Di Worship Sites by State (The analysis is based on 89 worship sites across 12 states). (b) The Nearest Neighbor Index (NNI) Analysis of Guan Di Worship Sites. Image by author.

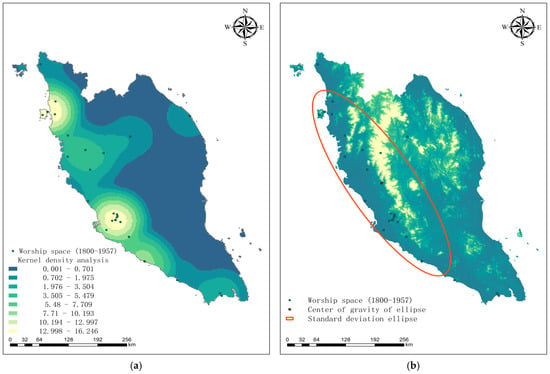

The Nearest Neighbor Index (NNI) confirms this pattern: a resulting R-value of 0.474582 and a Z-score of −9.482673 indicate that the distribution is statistically significantly clustered (p < 0.01), decisively rejecting the null hypothesis of a random pattern. The NNI results (Figure 9b) provide powerful, conclusive evidence that the spatial pattern of Guan Di worship sites is not random but is, in fact, highly clustered. This confirmed clustering provides the foundation for a deeper analysis of the field’s internal structure and evolution. This study conceptualizes the distribution of Guan Di worship not as a mere collection of sites, but as a dynamic ‘field of faith’ embedded within the specific geographical matrix of Peninsular Malaysia. To dissect this spatial logic, this section uses KDE, visualized in Figure 10a and Figure 11a, and SDE analysis (Figure 10b and Figure 11b), to dissect spatial patterns across two periods: 1800–1957 and 1958–2025. This chronological division is deliberate, with the year 1957 marking the independence of Malaya, a pivotal moment that initiated profound shifts in the nation’s political, economic, and social landscape.

Figure 10.

KDE (a) and SDE (b) Analysis of Guan Di Worship Sites on the West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia (1800–1957). Image by author.

Figure 11.

KDE (a) and SDE (b) Analysis of Guan Di Worship Sites on the West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia (1958–2025). Image by author.

The geography of the West Coast is characterized by a narrow coastal plain flanked by the Titiwangsa Mountains (Main Range). This topography decisively shaped the initial settlement patterns. During the colonial era (1800–1957), the spatial pattern of Guan Di worship was dictated by a port-hinterland economic structure. Early Chinese immigrants established communities along the coast and major river mouths (Kinta rivers) for agriculture and trade, while the discovery of tin pulled them inland towards the foothills of the mountain range. The KDE analysis (Figure 10a) confirms this geographical logic, revealing high-density clusters in the port cities of Penang and Malacca and the tin-rich Kuala Lumpur. This spatial pattern reflects the dominant economic models of the era: maritime port trade and inland resource extraction. Guan Di’s ‘interpretive malleability’ was key; his symbolism of ‘righteousness’ fostered cohesion in the ports, while his ‘martial attributes’ offered spiritual security in the often-turbulent mining frontiers.

In the post-independence era (1958–2025), a fundamental spatial recalibration occurred, mirroring Malaysia’s own economic transformation. The KDE map (Figure 11a) shows a decisive southward shift in worship hotspots toward the new economic powerhouses of Selangor and Johor. This was a direct response to the transition towards an urban industrial and service economy. The construction of the North–South Expressway, acting as the nation’s infrastructural spine, was a critical variable that reshaped the West Coast’s spatial dynamics. It facilitated the consolidation and integration of worship sites along this new economic artery, rather than being scattered. This interpretation is quantitatively supported by Table 2, which shows a peak in temple foundations (47.2% of the total) during this period of accelerated urbanization.

The SDE analysis quantifies this strategic geographical adjustment. A comparison of Figure 10b and Figure 11b shows the distribution’s center shifting southeast by approximately 66.14 km, a vector tracking the nation’s developmental axis. The ellipse’s area contracted (from about 60,291 km2 to 49,289 km2), reflecting a consolidation from scattered frontier settlements to an integrated network. This contraction suggests that as immigrant society matured and economic activities became more established, the faith’s primary spheres of influence shifted to more stable community centers. Concurrently, the ellipse’s orientation re-aligned with the dominant north–south geography. These metrics illustrate how the Guan Di belief system, activated by local actors, adapted its spatial presence in remarkable congruence with the evolving geographical and economic logic of modern Malaysia.The establishment of these permanent physical nodes created the stable, high-density hotspots identified by the KDE analysis and directly contributed to the spatial consolidation observed in the SDE analysis, making the faith’s distribution more defined and centralized. Therefore, this institutionalization was not merely a social development; it was a fundamental spatial practice.

4.2. Divergent Paths on West Coast: Hakka and Hokkien Adaptations

With the macro-spatial baseline established, the analysis now shifts to the micro level of social practice to reveal how ‘interpretive malleability’ was activated in divergent ways by different communities within these same geographical zones. The geographic proximity dictated by the West Coast’s economic landscape created a unique social dynamic. It forced communities that might have been segregated or even hostile in their homelands into a state of sustained interaction, a condition that not only generated conflict but also created the necessary grounds for eventual negotiation and understanding.

This trajectory from proximity-induced conflict to a form of emergent solidarity lies at the heart of the Malaysian Chinese diasporic narrative. It is precisely within this dynamic field of tension and accommodation that a figure like Guan Di, at once universally revered and highly malleable, became a crucial symbolic resource. His adaptable persona allowed disparate groups, each starting from their own unique social and historical positions, to ultimately converge towards a shared future, demonstrating a process of ‘arriving at the same destination by different paths’ (殊途同歸).

4.2.1. Economic–Ritual Networks: The Hokkien Case

Tracing the early dissemination and initial institutionalization of Guan Di worship on Peninsular Malaysia’s west coast leads us to the 19th and early 20th centuries. During this era, a massive wave of Chinese migration to Southeast Asia occurred, driven by survival pressures in mainland China and opportunities arising from colonial economic expansion in the region (Yen 1986, pp. 35–140). This period also witnessed the transition of Guan Di worship from the spiritual solace of individual immigrants into shared community ritual practices.

Many early Chinese immigrants, whether merchants, labourers, or others seeking a livelihood, also brought Guan Di worship to the Peninsular Malaysia’s west coast by carrying personal amulets. For example, Fu Boshi (傅伯石) from Anxi (安溪市), Fujian province (福建), brought a Guan Di statue about 30 cm high to Singapore’s Rambutan Ge Village (紅毛丹格) around 1910. Immigrants who moved from Bashe (八社), Anxi, to Pekan Nenas, Johor, carried with them ‘Guan Di incense ash pouches’ (關帝香火袋) inscribed with ‘Shanxi Fuzi’. Tracing earlier material evidence, fieldwork discovered a Guan Di incense burner dating back over six hundred years preserved in the Shui Yue Gong temple in Pulai, Kelantan, which might be considered one of the earliest physical proofs of Guan Di worship entering the region. Initially, this belief often manifested as highly individualized and private practices (family worship). Like Fu Boshi, who enshrined the Guan Di statue at home, immigrants in Peninsular Malaysia also hung these incense ash pouches, carrying the sacred power of their homeland, in their living rooms, setting up simple altars in homes, shops, or personal dwellings. This was not only to seek Guan Di’s protection in an unfamiliar environment, praying for safety, health, and business prosperity, fulfilling the basic needs for security and psychological comfort during the turbulent migration process, but also a way to transplant and maintain cultural capital in their homeland.

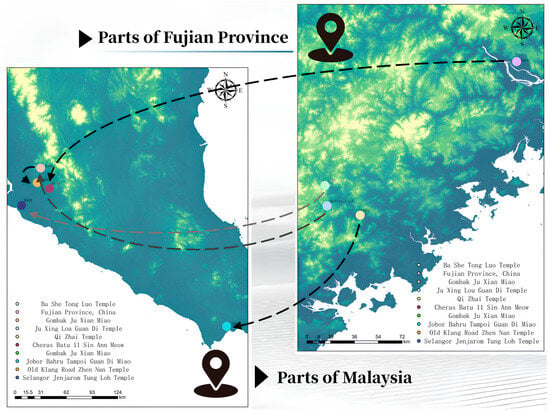

Following these initial, often individual or family-based modes of belief transplantation, ‘Fenxiang’ and ‘Fenling’ (分靈, dividing the spirit) emerged as crucial and more formalized mechanisms for establishing and validating Guan Di worship within nascent immigrant communities. This study’s fieldwork on the West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia primarily investigated Guan Di temples with clear fenxiang connections to the Southern Fujian (閩南) region, particularly areas like Quanzhou and Anxi.17 For example, the division of incense in the Jenjarom Tung Loh Temple (仁嘉隆銅鑼祖廟) was brought from the Ba She Tong Luo Temple in Hushan Township (安溪湖上鄉八社銅鑼廟), Anxi, by a disciple named Chen Bing (陳炳) in 1910, initially enshrined in a small hut on a gravel road. The spiritual connection of the Johor Tampoi Guan Di Miao originated in the 1920s when Soo Hng Hok (蘇遠福), an Anxi native, brought it from the Qi Zhai Temple in Hutou Town (安溪湖頭鎮七寨廟), his hometown, initially placing it in his own house. By Fenxiang from ancestral temples in their homeland or from earlier temples established locally, immigrants not only maintained cultural ties with their ancestral land in emotional and symbolic terms but, more importantly, this practice established a sacred genealogy.

It ‘replicated’ and ‘transplanted’ Guan Di’s sacredness to new locations, providing theological legitimacy for the establishment of new worship spaces, and gradually weaving an early transnational religious network across the west coast. The division of incense from Gombak’s Ju Xian Miao to Old Klang Road’s Zhen Nan Temple further illustrates the network’s growth within Malaysia itself (Figure 12, Table 4). It is noteworthy that Guan Di’s protective function was often extended in practice to cope with specific existential crises, especially in early immigrant society, lacking medical resources, where his divine power was interpreted by devotees as having healing potential. For instance, the origins of both the Jenjarom Tung Loh Temple in Selangor and the Sin Ann Meow in Cheras are related to immigrants carrying incense ash seeking Guan Di’s protection to overcome difficulties, including health issues. The successful founding and persistence of these new temples in areas like Selangor and Cheras are precisely what contributed to the formation of the new southern hotspots identified in the later period’s KDE map (Figure 11a).

Figure 12.

The Fenxiang relationship between Fujian Province, China, and Peninsular Malaysia. Image by author.

Table 4.

Examples of Fenxiang Paths for some Hokkien Guan Di Temples.

Horizontal connections between branch temples are also vital. Temples originating from the same ancestral temple, or those geographically close with overlapping devotee communities, often form ties through mutual visits, fellowship, and joint dharma assemblies. A clear example of this is the layered fenxiang process: through interviews and participant observation, it was learned that the incense from the Anxi Ju Xing Lou Guan Di Temple was brought to the Gombak Ju Xian Miao, which later further divided its incense to the Old Klang Road Zhen Nan Temple. This creates a regional chain of belief dissemination and an inter-temple interaction network, consolidating regional belief communities. Furthermore, these networks can extend to interactions with other deity cults, as seen in the close relationship between the Gombak Ju Xian Miao, the Old Klang Road Zhen Nan Temple, and the Selangor Ampang Nan Tian Gong Kau Ong Yah Temple (安邦九皇爺南天宮, Figure 13). The committee members of these temples have significant overlap, and Guan Di statues are even ‘invited’ to ‘assist’ during the Nine Emperor Gods festival celebrations, acting as ceremonial guards. This illustrates not only inter-temple collaboration but also the role of local elite networks in maintaining diverse belief practices.

Figure 13.

Two Guan Di Statues at the Nine Emperor Rituals. Image by author.

Secondly, the mobility of religious specialists, such as spirit mediums and Daoist priests, is another important factor. These specialists often serve multiple temples, connecting different belief nodes and promoting the exchange of ritual knowledge and practices. Taking Mr. Pang as an example, he not only holds positions in several temples but also, as early as 2000, traveled with Ms. Wen, the secretary of the Tampoi Guan Di Temple, to the ancestral Guan Di Temple in Haizhou (解州關帝廟), Yuncheng, Shanxi, China (Figure 14), for pilgrimage, and brought back incense ashes from the ancestral temple to be enshrined at Swee Foh Wan Tay. Another example is Mr. Wong, the general affairs manager of Ulu Hock Sui Tong in Kepong, who also provides divination services for devotees at the Gombak Ju Xian Miao.18 These ‘mobile nodes’ transmit information, share resources, and coordinate activities among different faith communities, playing an irreplaceable role in maintaining and expanding belief networks.

Figure 14.

Photo of Mr Pang’s visit to Haizhou Guan Di Temple in 2000. Image by author.

4.2.2. Simulated Kinship in the Mining Frontier: The Hakka Case

The fenxiang networks, tracing their origins to ancestral temples in Southern Fujian, established a sacred genealogy that legitimized new temples on the West Coast, creating a web of spiritual and economic interconnectedness. For these communities, Guan Di was often interpreted as a protector of commerce and a bestower of wealth. The role of mediums, who could channel the deity to provide specific advice for business or personal matters, became central. This adaptation highlights a more transactional and pragmatic engagement with the deity, where his ‘human prototype’ was accessed not just for his moral virtues but for his perceived efficacy and wisdom in navigating the complexities of the marketplace.

In essence, the practice of fenxiang acted as the engine for the spatial evolution of Guan Di worship. It translated individual belief into a structured, interconnected network, anchored new worship sites in developing regions, and provided the functional adaptability for the faith to thrive. The macro-patterns of consolidation and shifting hotspots observed via GIS are the cumulative, visible outcomes of these countless, localized ritual actions.

In the tumultuous social landscape of 19th-century Malayan tin mining frontiers, a domain predominantly shaped by Hakka immigrants and characterized by a severe gender imbalance, creating a largely male-dominated society, the figure of Guan Di was strategically activated. The worship patterns surrounding Sin Sze Si Ya, the deified Hakka Kapitan (甲必丹) Yap Ah Loy, who led the Hai San, provide the most vivid evidence of this strategy. While the previous chapter discussed the strategic use of Guan Di’s symbolism in frontier societies, this section provides quantitative and geographical evidence for this phenomenon by examining the relationship between Guan Di and the Hakka patron Sin Sze Si Ya.

An investigation of fifteen primary Sin Sze Si Ya temples reveals a stark pattern: thirteen also enshrine Guan Di. This geographical correlation is not random; twelve of these thirteen temples are situated squarely within the historical tin-mining belt of Selangor, Kuala Lumpur, Negeri Sembilan, and Pahang (Table A2). This calculated inclusion of the pan-Chinese hero Guan Di alongside a specific dialect-group patron was clearly a strategic act of symbolic coalition-building. The exceptions reinforce this conclusion: the two Sin Sze Si Ya temples lacking Guan Di are located outside this primary mining belt (Malacca and Johor). The relationship is also demonstrably one-directional, as temples dedicated to Guan Di rarely enshrine Sin Sze Si Ya. A notable exception, the Lieh Sheng Gong in Seremban, itself located in the tin belt, further underscores that this fusion was a specific adaptation to the frontier’s socio-economic conditions. It was here that the ‘persistence of the human prototype’ was activated, casting Guan Yu as the supreme patron for a simulated kinship network where expansive, ritualized brotherhood was paramount.

Additionally, when examining the complexity of the relationship between societies on the West Coast and Guan Di, a phenomenon worth further exploration emerges: the asymmetrical worship relationship between Guan Di belief and a specific local deity—Sin Sze Si Ya. Current investigations for this study reveal that among the identified Guan Di worship sites, only the Lieh Sheng Gong, established in 1876 in Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, also enshrines Sin Sze Si Ya. Conversely, out of fifteen temples in Malaysia primarily dedicated to Sin Sze Si Ya, only two do not also feature Guan Di as a venerated deity. This asymmetry might reflect the complex power structures and symbolic strategies within 19th-century West Coast Chinese society. Sin Sze Si Ya worship is closely linked to Yap Ah Loy, the pioneering founder of Kuala Lumpur, and the Hai San Society he led.

This study speculates that:

Borrowing Authority and Integrating Resources: Given Guan Di’s widespread recognition across regions and dialect groups and his symbolic power universally employed by various factions in society conflicts, incorporating Guan Di into Sin Sze Si Ya temples associated with the Hai San Society helped borrow his authority to enhance their own legitimacy and integrate this powerful symbolic resource to consolidate power.

Reasons for Fewer Sin Sze Si Ya Shrines in Guan Di Temples: In contrast, Sin Sze Si Ya’s symbolic meaning was highly localized and factionalized. For Guan Di temples serving broader communities or wishing to avoid involvement in specific factional disputes, incorporating Sin Sze Si Ya might lack necessity and could even cause identity confusion.