Abstract

The educational philosophy of the Nuns’ Buddhist Academy at Pushou Monastery, Mount Wutai, is based on the principles of “Hua Yan as the foundation, precepts as the practice, and Pure Land as the destination.” This philosophy draws upon Buddhist scriptures, integrating descriptions of the Pure Land practice found in the Avatamsaka Sūtra and the Amitābha Sūtra. This approach translates the textual teachings of Buddhist classics into real-life practice, expressing the concept of “the non-obstruction of principle and phenomenon” in the tangible activities of practitioners. It also allows for the experiential understanding of the spiritual realms revealed in the scriptures during theoretical learning and practice. The philosophy of the Nuns’ Academy embodies the practical emphasis of Chinese Buddhism, guiding all aspects of learning and practice. This paper argues that the pure land practice is living. In order to understand pure land practice, there should be a comprehensive viewpoint. It is needed to explore this way of practice through the analysis of textual analysis, figuring its root in Buddhis sūtra, as well as a sociological method to investigate its manifestation at the present society. Moreover, the spiritual dimension should not be neglected for a full-scale study. In this sense, the pure land school is living at present.

1. Introduction: A Review of Research on Pure Land Practice

The Nun’s Buddhist Academy at Mount Wutai is familiar to western Buddhist scholars. For instance, Amandine Péronnet had met Master Rurui, who is the abbess of Pushou Monastery on Mount Wutai (Péronnet 2020). Amandine’s research is a biography introducing Master Rurui in the view of charisma. In this article, we focus on the practical dimension of nuns in Buddhist Monastery lead by Master Rurui. The emphasis on practice is a Chinese interpretation of Mahāyāna Buddhist doctrine that reflects the Sinicization of Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism. In a practical sense, it expresses how local monks understand Buddhist texts. While pursuing the goal of liberation, Mahāyāna Buddhism also imbues the mission of saving sentient beings. Given sentient beings’ diverse conditions and capacities, the Mahāyāna perspective on sentient beings and the spirit of the Bodhisattva manifest in various forms in actual practice, encapsulated in the phrase “the ultimate enlightened mind, adapting to all of the circumstances of sentient beings.”1 Nianfo (the practice of reciting the Buddha’s Name, see Appendix A) is a relatively accessible method of practice that almost anyone can engage in. At the same time, it reveals varying depths of understanding; practitioners uncover profound meanings as practice progresses. Nianfo is described as “the profound essence of the Avatamsaka Sūtra 《華嚴經》 and the secret key of the Lotus Sūtra 《法華經》, the heart essence of all Buddhas.”2 The Nianfo method belongs to the Mahāyāna teachings of the Perfect Teaching 圓教. This paper uses the case of the “Intensive Buddha Retreats” at the Nuns’ Buddhist Academy (Yuci Mahāyāna Monastery) to explore how the practicality of Mahāyāna Buddhism is being realized in contemporary China.

The Pure Land school is one of the most representative sects of Chinese Buddhism. Throughout history, numerous scholars and monks have interpreted Pure Land texts and implemented the recorded methods into practice. Nowadays, scholars employ scientific research methods from various fields to study Pure Land practice, each with unique disciplinary characteristics. In the current Chinese Buddhist landscape, the most representative monastery focusing on Pure Land practice is Donglin Monastery in Lushan, Jiangxi.3 Master Da’an’s Pure Land School Textbook systematically explains Pure Land Buddhism’s history, canonical basis, practice, and goals (Shi Da An 2006). From a holistic perspective of Buddhism, the Pure Land school is not merely a sect of Chinese Buddhism but a pathway that connects to the core doctrines of Buddhism. Thus, it features a simple practice method that encompasses profound philosophical meanings. “Amitābha Buddha’s three bodies—Dharma body, reward body, and transformation body—are one and manifest according to circumstances (see Appendix A). By adorning the Buddha’s form, they evoke the inherent dignity of practitioners of pure practices, aligning with the ultimate reality of true suchness.” (Shi Da An 2006, p. 276).

The essence of reciting “Amitābha Buddha” is to attain an understanding of emptiness (see Appendix A). The reality of the Pure Land is evidenced by the achievements of numerous practitioners throughout its history. Many Buddhist texts address Pure Land ideas, and local monks have selected five scriptures and one treatise as the foundational texts of Pure Land Buddhism:

- The Larger Sūtra on Amitāyus (translated by Kang Sengkai 康僧鎧, during the Cao-Wei period: 252 CE);

- The Smaller Sūtra on Amitāyus (translated by Kumarajiva during the Yao-Qin period: 402 CE);

- The Sūtra on Contemplation of Amitāyus (translated by Kalayashas 畺良耶舍 during the Liu-Song period: 424–442 CE);

- The Avatamsaka Sūtra: The Chapter on the Conduct and Vows of Samantabhadra (translated by Prajna during the Tang dynasty: 795–798 CE);

- The Shurangama Sūtra: The Chapter on the Mahasthamaprapta Bodhisattva’s Recitation of the Buddha (translated by Pramiti during the Tang dynasty: 705 CE);

- Verses of Aspiration for Rebirth in the Land of Amitāyus (composed by Vasubandhu, translated by Bodhiruci during the Yuan-Wei period: 529 CE).

These five scriptures and one treatise comprehensively cover the doctrines of Pure Land Buddhism.

Gong Xiaokang’s “Integration and Continuity: A Study of Ouyi Zhixu’s Thoughts” elaborates on how the ninth patriarch of Pure Land, Ouyi Zhixu, integrated the thoughts of Tiantai, Hua Yan, Chan, and Yogacara into the practice of Pure Land Buddhism, achieving a transformation in the awakening of the mind and nature in the “one moment of experience” (Gong 2007). This research serves as a modern interpretation of “the profound essence of the ‘Avatamsaka Sūtra’ and the secret key of the ‘Lotus Sūtra,’ the heart essence of all Buddhas.” Chen Yuhao comprehensively reviews the research status of Chinese Pure Land Buddhism over the past century, categorizing it into four periods: the Republic of China, the period from the founding of the People’s Republic of China to before the Reform and Opening, the last twenty years of the 20th century, and the 21st century. The research content is divided into historical, theoretical, literary, and artistic studies. Historical and theoretical research has yielded fruitful results, while literary studies have also achieved particular accomplishments; however, artistic studies remain relatively weak. Overall, the existing achievements in Pure Land research do not match its historical impact, indicating a vast potential for further exploration (Y. Chen 2019). The author has systematically sorted the research on Pure Land Buddhism in China over the past century from a bibliographical perspective, offering a structural understanding of research outcomes based on periodization and research focus, which facilitates future studies and lays a foundation in the literature. At the same time, commentary on Pure Land doctrines requires further depth; it is crucial to note that research from various angles aims to substantiate the reality of Pure Land theory, ultimately directing attention to the practice of cultivation while not straying from the fundamental Buddhist goal of realizing emptiness and pursuing spiritual liberation. The division of research angles can provide a structural understanding of research outcomes but should not become a limitation.

Recent research indicates that methods from philosophy, psychology, sociology, and other fields have begun to be applied to the study of Pure Land Buddhism. Chen Yuanhong approaches the question of what the Pure Land is from a philosophical perspective. First, the concept of the Pure Land is broader than that of the Pure Land school in the context of Mahāyāna Buddhism, where there are infinite Buddhas, so there are also infinite Pure Lands. Secondly, the establishment of the Pure Land is rooted in the Buddha’s intent for skillful means in teaching. The distinction between impure and pure lands is not a matter of essential opposition but relates to the degree of discernment and attachment within the hearts of sentient beings; purity and impurity depend on sentient beings as conditions. Thus, the distinction between Pure and impure lands is similar to the relative establishment of good and evil in Tiantai’s concept of “interinclusiveness of the ten realms,” which must be understood from the perspective of sentient beings’ understanding of emptiness and their circumstances. The distinction between the mind-only Pure Land and the Pure Lands in the remote places arise from not having realized the true meaning of “mind-only.” If one understands that a single thought permeates the Dharma realm, one knows that the mind-only Pure Land is other Pure Lands. As a means of skillful teaching and salvation, the Pure Land practice aligns with the absolute emptiness of the first truth (Y. Chen 2024, p. 137).

Zhang Haibin and Cen Fujiang use psychological methods to interpret how reciting the Buddha’s Name in Pure Land practice can help adjust a person’s psychological state (Zhang and Cen 2020). The Pure Land ritual of reciting the Buddha’s Name can provide a sense of inner security. The concept of “rebirth” and the idea of “no-self” can help overcome the anxiety brought by death on both rational and emotional levels. Meanwhile, when confronting the image of Amitābha Buddha and narrating one’s life experiences, emotions can be channeled, expressed, and sublimated. Amitābha Buddha serves as a perfect archetype constructed within one’s heart, which can facilitate positive transformation and alleviate suffering caused by self-attachment. From the perspective of Jungian psychology, Amitābha Buddha is a religious expression of the self-archetype, which can integrate personality emotionally and rationally.4 The Mahāyāna Buddhist concept of the “Bodhisattva” can be viewed psychologically as a reconstruction of one’s relationship with the surrounding world after recognizing the illusory nature of the self, serving as a means to overcome loneliness. It is important to note that the practice of reciting the Buddha’s Name should be guided by the middle way and the Tiantai concept of the Perfect Teaching, avoiding attachment to the ideal circumstances constructed in the mind, which could lead to exclusiveness of real life, while achieving positive transformation in an ordinary state. The psychological interpretation provides a perspective that brings the understanding of Pure Land recitation closer to everyday language, making religious activities more accessible. However, it also diminishes the reality of Pure Land thought within a religious context, transforming it into a subjective psychological state.

In the field of social sciences, there are cases where phenomenological interview scales are used to study the meditative experiences of monks. One study collected interview records from monks and nuns of the Pure Land and Chan traditions through phenomenological interviews as data.5 Using a three-factor structure for data analysis suggests that religious mystical experiences likely have a common core. Interviews with Pure Land monks indicate that “the goal of reciting Sūtras is to cultivate wisdom, rather than to pursue a specific spiritual state.” (Chen et al. 2011, p. 661). Although Buddhism is atheistic, reports from Pure Land practitioners show that they experience the blessings of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas during their practice. In comparing the practices of Pure Land and Chan, Chan is seen as a technical vertical transcendence, while the recitation of the Buddha’s Name in Pure Land is accessible and equal for all beings. And when the scope of “the intensive Buddha retreat” is expanded, the Fo Guang Shan short-term monastic retreat enters the vision. In the framework of Humanistic Buddhism, the experience of ethical shortcomings can a positive instrument and aspect of religious striving, since the acceptance of the actual situation is the starting point of transformation into higher spiritual realm (Laidlaw and Mair 2019). The young adults attending Zen meditation camp also suggests that in the process of transformation, participants did not need to be worry about their imperfections (Song and Yan 2020). These interview of field research demonstrate the pivotal role of the acceptance attitude in the Buddhist practice, i.e., the transformation should be based on the real-life foundation rather than the imaginary perfection. Besides this, the inclusive attitude is consistent with the detachment thought in the Buddhist doctrine. Jones’ works lay a solid foundation for understanding Pure Land Buddhism (Jones 2019).

Furthermore, both Pure Land and Chan serve as paths to emptiness. In the context of Pure Land practice, one monk noted, “With one mind, I recite the Sūtras. I focus on each word, making sure to pronounce every one correctly. Suddenly, everything becomes empty; my mind has nothing. I am filled with joy sparked by the wisdom in the scriptures.” (Chen et al. 2011, p. 669). This reflects the essence of the interviews. The common core propositions revealed in the Buddhist context indicate an inherent logic of “emptiness—ineffable—practice.” The limitations of the data collected from interviews parallel the issues faced in the philosophy of language, as language itself is inherently limited in expressing reality. Only through practice can we overcome the limitations of language.

Empirical research findings also support this point. The experience of emptiness within the mind and actual experiences may seem contradictory, yet for those who have lived it, it is real: “Neither emptiness nor existence is the truth. This is somewhat astonishing, but it can be experienced.” “Do not try to understand it; instead, practice it. When you are there, you will know.” The Heart Sūtra articulates this paradox through a rhetorical device: “Form is emptiness; emptiness is form.”

The Pure Land sect in modern China has integrated with the idea of humanistic Buddhism, aiming to address the social issues Chinese society has faced since the modern era. It seeks to solve social problems through Buddhist wisdom, thereby establishing a humanistic Pure Land, which is essentially a good social living environment. In contemporary China, with the significant enhancement of national strength, the humanistic Buddhist thought has already addressed the social issues it once faced. Humanistic Buddhism has been imbued with new meanings in this historical phase.

The pressing question for humanistic Buddhism is how to respond to the Integration of traditional Buddhist teachings and modern artificial intelligence (Zheng 2024). AI technology has played an important role in translating Buddhist texts, developing Buddhist robots, and constructing online virtual practice environments. According to the theory of humanistic Buddhism, there is an expectation that AI technology will positively contribute to the realization of a humanistic Pure Land. However, the concept of “positive contribution” remains uncertain. The interactions between AI and humans impact human thoughts, emotions, and spirituality. Humanistic Buddhism, while interpreting the idea of “insentient beings having Buddha-nature,” suggests that AI might possess Buddha-nature.6 Thus, on one hand, AI can serve as a driving force for achieving a humanistic Pure Land; on the other hand, if AI does have Buddha-nature, it raises ethical questions about whether humans should submit to AI or whether AI should serve humans. As for the problem raised by AI, which could be generalized as to what extent technology could be used in the Buddhist practice. A short answer is that AI is not a new external idol for people to worship. Rather, Donglin Temple in Jiang Xi province, for example, uses the virtual vision technology to conduct the imaginary environment of pure land according to the text of sutra. The venue of Buddha retreat in Pushou Temple, similarly, presented the image of Amitabha Buddha through the electronic screen on the wall. It is noteworthy that the image built by electronic technology is to inspire people to reveal the pure state in people’s realm of mind, rather than there is a real Buddha external to hearts of sentient beings.

In summary, the practice of the Pure Land sect ultimately points towards emptiness. In this sense, the Pure Land path can be understood as the “the profound essence of the Avatamsaka Sūtra and the secret key of the Lotus Sūtra,” since all Buddhist practices tend towards the realization of emptiness for liberation. Moreover, scholars need to update their perspectives based on research findings regarding the Pure Land sect. Beyond the traditional fields of history, literature, and art, relevant studies in philosophy, social sciences, and artificial intelligence have already infiltrated the research of the Pure Land sect. Researchers often adopt a dualistic stance from an observer’s perspective, which, to some extent, obscures the insights revealed by the dimension of Buddhist practice. Any single method or perspective is insufficient to reveal the true meaning of Pure Land practice, thus in this paper, we adopt a comprehensive methodology with the combination of analysis of text and field research, in which we are the participants of the activity.

2. Research Method: Combining Buddhist Doctrine Study with Field Research

Pure Land Buddhism is an important sect of Chinese Buddhism, established through the localization of Mahāyāna Buddhist texts. This localization encompasses both the interpretation of doctrines within the Chinese context and the extraction of practical meditation methods from the scriptures. Current research on Pure Land Buddhism in China has thoroughly explored its history and doctrinal aspects. However, further field research is needed to examine the practical forms of Pure Land practice in modern society and its connections with other sects.

This paper primarily references Jones works (Jones 2021) and Master Da’an’s “Pure Land Buddhism Textbook,” the “Lotus Sūtra,” the “Avatamsaka Sūtra: The Ten Great Vows of Samantabhadra,” (《大方廣佛華嚴經》 2024) the “Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna,” (《大乘起信論》 2023) and Ouyi Zhixu’s “Essential Explanations of the Amitābha Sūtra” (《佛說阿彌陀經要解》) along with his selected “Ten Essentials of Pure Land.” (《净土十要》) Through the study of classical texts and contemporary interpretations by monks, one can gain insight into the formation of Pure Land Buddhism and comprehend its nuanced doctrinal structure and theoretical implications.

The recitation of Amitābha’s Name is widely popular, even among those who do not study Buddhism; many associate Chinese Buddhism with “Amitābha.” This simplistic impression reflects the significant social influence of Pure Land Buddhism. Reciting the Buddha’s Name addresses people’s existential anxieties about life and death, filling a theoretical gap in Confucian thought and providing a more comprehensive understanding of life for Chinese people. The perspective of the Tiantai school’s “perfect teaching” infuses the practice of Pure Land with a middle-way approach, reminding practitioners not to develop a rejection of worldly life due to attachment to Pure Land.

Pure Land Buddhism is a practical way within Buddhism that ultimately aligns with realizing emptiness. Therefore, it incorporates views from Buddhist schools such as Tiantai, Huayan, Yogacara, Chan, and Vinaya. In the sense of spiritual liberation, the aspirations of these sects converge. The Pure Land practice is a skillful means of embodying the essence of ultimate (spiritual) liberation. Reciting the Buddha’s Name should occur within the foundational framework of Integration and the middle way.

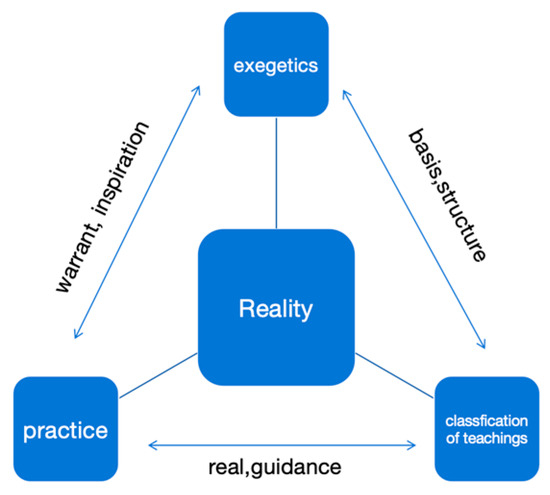

Building on a preliminary understanding of Pure Land doctrine, the researcher engaged in the “Buddha Retreats in seven days” activities at a monastery using methods akin to anthropology. Through this participation, the researcher experienced the manifestation of doctrines in real situations and understood the meanings conveyed by Pure Land Buddhism through the interaction of theory and reality. The following diagram interprets the fundamental inner structure of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism. For example, the Buddhist practice warrants and inspires the exegetics work, and vice versa (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The fundamental inner structure of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism.

The above diagram represents the structure of Chinese Buddhism, and the Buddha retreats could be categorized in the box of “practice.” At the same time, they are indivisible from other modules of this structure. This diagram is a specific form of the structure pointed by Chen Jian, whose is the generalized form (J. Chen 2007, p. 31.).

3. Research Content: “Intensive Buddha Retreats in Seven Days”

The “Intensive Buddha Retreats in Seven Days” took place in the Dharma Hall of the Dacheng Monastery. Dacheng Monastery is a branch of the Wutai Mountain Nuns’ Buddhist Academy, presided over by Master Ruirui, and is part of the Pusou Monastery’s “3+1” project (Péronnet 2020). Ji Zhe has made a list sangha educational organs of the Han tradition in China (Ji 2019, pp. 200–7), in which Mount Wutai Buddhist Academy for Nuns is under the number 25 (Ji 2019, p. 222).

3.1. Venue Arrangement

Dacheng Monastery is located in the southeast of the old town of Yuci, with the Complete Enlightenment Hall and the Great Buddha’s Hall aligned north to south along the monastery’s central axis. The Sūtra Storage Building is still under construction. The Buddha Seven is conducted in the Dharma Hall, where the nuns learn ordinarily, which is situated in the northeast corner of the monastery, facing west. The hall’s main entrance opens to a space in front of the Sūtra Storage Building. Upon entering through the main door, a circular hallway surrounds a central area that serves as a classroom.

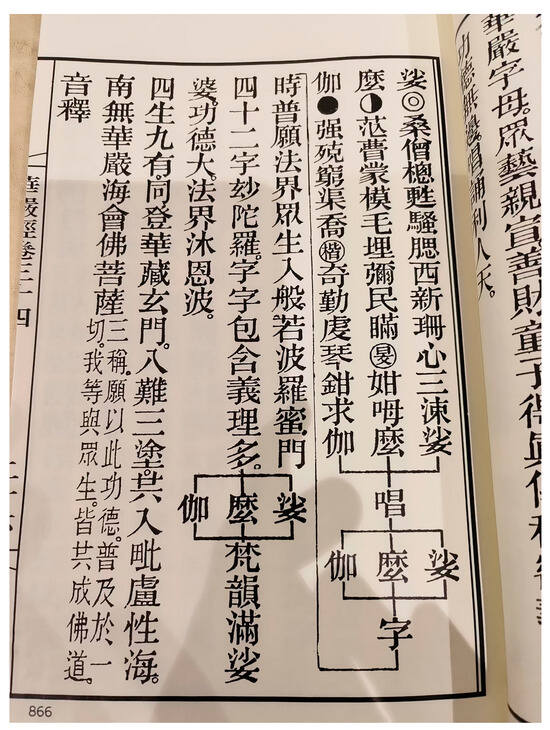

Inside the classroom, three large screens on the eastern wall display the standard image of Amitābha Buddha. A platform in front of the screens holds a statue of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, while a statue of Manjushri Bodhisattva is positioned at the center. On either side of the entrance along the central axis is a statue of Weituo Bodhisattva on the south side and a statue of Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva (Guandi) on the north side. The remaining classroom walls are lined with tall bookshelves that store copies of the “Avatamsaka Sūtra,” arranged in numbered order. The evening session before the Buddha Seven included the recitation of the “Avatamsaka Sūtra: Chapter on the Ten Grounds” (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A page sample of the chanted Avatamsaka Sūtra.

The glass doors of the bookshelves display the standard image of Amitābha Buddha and a welcoming image of the Pure Land in the West. Above the welcoming image is an inscription: “May I encounter no obstacles at the end of my life; may Amitābha Buddha come to greet me from afar.”7 The combination of Amitābha Buddha’s image with the “Avatamsaka Sūtra” reflects the mission of the Pusou Monastery Nuns’ Academy, which emphasizes “Avatamsaka as the doctrine, Pure Land as the spiritual lodge.” And it aligns with the theme of the Buddha Seven.

Wooden fish and inverted bells are placed beside the platform. The classroom is divided into southern and northern sections along the central axis, with about 225 cushions in each section, totaling approximately 450 spots. Each cushion features lotus embroidery. A nun is specifically assigned to arrange the cushions, ensuring that the edges of the round cushions maintain a tangent relationship with the gaps in the floor tiles, resulting in a very orderly appearance overall. The arrangement of the venue symbolically recreates the scene of the Pure Land as described in the Sūtras.

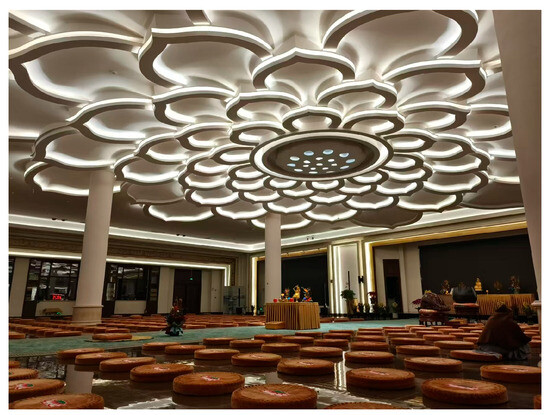

The community of nuns is the core of the ritual. The reason why the title of the school is “Nun’s Buddhist Academy” is this school is built especially for female practitioners. Master Rurui and her ancestor abbess Master Tong Yuan build and engage in the management of the school for women, which shows the gender equality both in the context of modern society between men and women and from the viewpoint of Buddha, since Buddha is also a feminist (Bai 2011, p. 165). Amandie has pointed out that it is the largest female Buddhist monastery in contemporary China. Moreover, it is for the female practitioners globally. There is a counterpart female Buddhist Academy of Tibetan Buddhism, i.e., Ya Chen Monastery 亞青寺, in Sichuan province, China (Bai 2011). In the process of the ritual, nuns played the crucial role. Firstly, there is a regular form of every section of the continuous process, and the movement was led by nuns, so that people could follow them orderly. Secondly, as the ritual is held in the hall, which is a close room, some nuns thus opened and closed doors and windows at the suitable moment according to the ritual process, for people to get fresh air and quiet practice environment simultaneously. Finally, the deeper meaning of nuns is that they are one of three treasures, i.e., Buddha, dharma, monks and nuns, in Buddhism. Their presence is not only functional but also meaningful itself. When people see them, the faith of Buddhist dharma in hearts can be enhanced. Moreover, from the viewpoint of equality in Buddhist context, everyone in the ritual could be a core. The peaceful environment of the venue is helpful for people to concentrate on their mindful practice. The following picture shows a meditating nun in the Dharma Hall (See Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A photo of the venue from a corner.

3.2. Schedule

The schedule of the practice manifests that to what extent this Buddha retreats ritual could be regarded as ‘intensive’, Table 1 is the necessary and fixed assignment that nuns need to do during this week.

Table 1.

2024 Da Cheng Temple Intensive Buddha Recitation Schedule. (From the 2nd to the 8th day of the first lunar month).

4. How Does the Pure Land in Scripture Manifested in Real-Life

According to the schedule of the Amitābha recitation session, it is evident that the recitation activities are intensive throughout the day, with only a one-hour break after lunch. There are six hours from the cessation of activities the previous day to the start of the next day’s sessions. There is no breakfast in the morning, and there are no evening meals. The morning sessions are adjusted to focus mainly on reciting the “Amitābha Sūtra” and chanting. The monastery opens the gate around 7:30 A.M., and laypeople can only participate in the recitation activities that begin at midday; the morning session is not open to the public.8

The recitation activities consist of several cyclic segments, including walking and chanting, seated chanting, meditation, and prostration. The walking and chanting are led by nuns who walk around the classroom while chanting, using the sound of the wooden fish and inverted bell to mark the rhythm of the Pathaka (梵唄), reciting “Namo Amitābha Buddha” in a sing-song manner. As the group progresses, a natural rhythm develops: “Namo” is aligned with the right foot, “Amitā” with the left, and “Buddha” with the right again. Following the group leads participants to merge into this rhythm naturally. This method highlights the convenience brought by Chinese characters. If “Namo Amitābha Buddha” is pronounced according to its original coherent sounds, it is difficult to sync with the rhythm of the march, reflecting the differences in application between square characters and linear scripts. The walking and chanting lasts for one hour, followed by 45 min of seated chanting, where the first 20 min continue with “Namo Amitābha Buddha,” and then the rhythm slightly speeds up to just “Amitābha Buddha.” After this, the sound of the wooden fish indicates the start of meditation. During this period, participants must silently chant “Namo Amitābha Buddha” in their minds. If it were a Chan session, participants would contemplate the question, “Who is reciting Buddha?” Recitation and meditation are two skillful methods that complement each other. When one attains the state of “Buddha recitation samadhi,” the distinction between subject and object dissolves, embodying a state of deep meditative absorption.

In meditation, “Who is reciting Buddha?”9 is a critical focus, requiring continuous concentration on this question and eliminating the distinction between subject and object in that focused state. Both seated chanting and meditation adopt the “cross-legged sitting” posture described in Buddhist scriptures. This posture is relatively stable and requires specific training; recitation is the main focus during the retreat session. Prostration occurs during the remaining time after collective activities and can be freely arranged. Dedicated nuns and lay practitioners will sincerely prostrate to Buddha on their mats or continue sitting in meditation.10 Some nuns might take out the “Avatamsaka Sūtra” from the classroom bookshelf to read or prostrate to the Sūtra. Prostration is a relatively relaxed period in schedule. The Parinamana at the end resembles a summary, with the content stating, “May I be reborn in the Pure Land, with nine grades of lotus flowers as my parents; may the flowers bloom and allow me to see Buddha and realize non-birth, accompanied by non-retreating Bodhisattvas.”11 The dedication text provides a brief summary of the content found in the “Amitābha Sūtra.”

The process of the Pure Land chanting is straightforward and simple in form. Regardless of an individual’s background knowledge of Buddhist teachings, anyone can join the chanting and easily integrate into the group. At the same time, the deeper meanings each individual can grasp are known only to themselves. A characteristic of Chinese culture is its emphasis on inner essence and practice. While the outward forms may not show significant differences, the inner essence and practice can vary greatly.

For example, in the “full/half lotus position,” untrained individuals may experience leg pain or numbness within minutes; trained Buddhists can sustain it for over an hour, and those who can enter deep meditation reach a higher level. Moreover, in the Buddhist context, chanting Amitābha has aspects of “response” or connection; different individuals may possess varying levels of faith and connection to Amitābha while chanting. This is considered a secret teaching in the Tiantai classification of teachings, often expressed as, “Just as a person drinking water knows whether it is cold or warm.”

From 15:30 to 16:30, there was an online theoretical teaching session led by Master Miaoguang from Wutai Mountain, who explained the related principles and practices of the Pure Land chanting online from Pushou Monastery. The Master’s explanations were indeed helpful for understanding the Buddhist background of the Pure Land activity and the meanings of Amitābha and the Western Pure Land. This knowledge provided cultural significance to the experiential activity of chanting and addressed many doubts that people have about it. Master Miaoguang’s explanations can be understood as imparting the meaning of life within the context of Mahāyāna Buddhism, which is to liberate sentient beings.

The goal of Buddhism is liberation, and in the Mahāyāna context, it focuses not only on individual liberation but also on the liberation of the community. Thus, Mahāyāna Buddhism interprets the meaning of life as the liberation of sentient beings. “Liberating sentient beings” unfolds into two aspects: “liberation” refers to skillful means in teaching, and “sentient beings” represents the core perspective of Mahāyāna Buddhism. In Mahāyāna Buddhism, the term “Bodhisattva” combines “awakening” and “sentient beings,” and the Bodhisattva spirit embodies the meaning of life that Mahāyāna Buddhism seeks to convey. The literature referenced for this session primarily includes Master Ouyi’s “Essentials of the Amitābha Sūtra” and the “Avatamsaka Sūtra: The Conduct and Vows of Samantabhadra Bodhisattva.”

The Avatamsaka Sūtra, Volume 51, states: “At that time, the Tathāgata (see Appendix A), with the unobstructed and pure wisdom eye, universally observed all beings in the Dharma realm and said: ‘Remarkable! Remarkable! How do these beings possess Tathāgata wisdom yet are deluded, ignorant, unaware, and unseeing? I shall teach them the holy path, enabling them to forever abandon false thoughts and attachments, so that from within themselves, they may perceive the vast wisdom of the Tathāgata, which is no different from that of the Buddha.’”12 This indicates that the thought of skillful teaching methods arose at the moment of the Buddha’s enlightenment, allowing sentient beings to reveal their inherent Buddha-nature by following Buddha’s guidance.

The Lotus Sūtra conveys the same principle through metaphor. In the fourth chapter, “Willing Acceptance,” the parable of the impoverished son describes, “For this reason his father let him continue to sweep dung for twenty years.” (Yuyama and Akira 2007, p. 18). This implies that teaching sentient beings must be tailored to their inherent capacities; directly revealing the ultimate truth to non-receptive people is ineffective. When teachers and students cannot achieve harmony, the teaching process cannot proceed effectively. In the second chapter, “The Skillful Means,” of the Lotus Sūtra, it is recorded that Śāriputra requested the Buddha to expound the teachings three times, yet when he spoke, five thousand individuals, including monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen, rose from their seats, paid their respects to the Buddha, and departed. This demonstrates that even when the Buddha teaches with an equal heart, the teachings may not suit the dispositions of all beings, leading to the withdrawal of those who are overly proud.

In the Avatamsaka Sūtra, within the chapter on entering the Dharma realm, the hearers are unable to perceive the state of the bodhisattvas: “The bodhisattvas are fully endowed with all virtuous practices; such matters are not seen by the śrāvakas and the many other disciples.” Śrāvkas are also unable to witness the Tathāgata’s transcendent powers: “Because the śrāvakas’ vehicle transcends the three realms, and they are satisfied with their own path, hence they cannot attain the wisdom of the non-possessive; they dwell in the ultimate truth, which is always joyful and serene, far removed from great compassion, constantly self-regulating, and detached from sentient beings. Thus, even when sitting face-to-face with the Tathāgata, they cannot perceive his miraculous transformations.” (《大方廣佛華嚴經》 2023, p. 675).

When the Buddha teaches, he must deliver teachings corresponding to different sentient beings’ capacities. Because sentient beings vary, so too do the Buddha’s teachings. The systematic arrangement of these teachings according to their pedagogical order leads to the classification of teachings.13 In this sense, Professor Chen Jian points out that “the classification of teachings is essentially a classification of the sentient beings.” Mahāyāna Buddhism is centered on sentient beings. According to the Tiantai school’s five periods of teaching, the Buddha’s teachings are categorized into the periods of the Avatamsaka period, Āgama period, Vaipulya period, Prajñāpāramitā period, and Lotus and Nirvāṇa period. Master Miaoguang provided a relatively accessible introduction to the five periods of teaching: the Avatamsaka period discusses the ultimate liberation realized at the moment of the Buddha’s enlightenment; the Āgama period primarily addresses the truth of suffering, aiming to inspire a sense of renunciation in sentient beings; the Vaipulya period encompasses a broader range of beings; the Prajñāpāramitā period teaches emptiness to counteract beings’ attachment to the impermanent as the permanent; and the Lotus and Nirvāṇa period asserts that all beings possess Buddha-nature and can attain Buddhahood.

In “The Outline of Teachings and Contemplations,” Master Ouyi systematically organizes the “Five Periods and Eight Teachings” using rigorous academic language. He explains the “Five Periods” from the thought of exposing the Three Vehicles and revealing the reality of the one method of salvation, as found in Lotus Sūtra, stating, “It is precisely because sentient beings have differing capacities that the Tathāgata skillfully speaks differently.” (Ouyi Zhixu 2014b, p. 299).

The Pure Land tradition places significant emphasis on faith in the Western Pure Land of Amitābha Buddha. According to the Tiantai school’s classification of teachings, it is categorized as part of the “vaipulya” phase, which asserts, “This is included within the Mahāyāna teachings of the vaipulya teachings.” Simultaneously, the Pure Land teachings incorporate elements from the Avataṃsaka, Agama, Prajnaparamita, Lotus, and Nirvana teachings, thus encompassing aspects from all five phases.

In addition to systematic theoretical instruction, Master Miaoguang shared personal experiences from his practice and his understanding of the scriptures. For instance, he noted that the precepts must be accompanied by the Cattāro Satipaṭṭhānā to achieve liberation.14 The term “monastic” is also referred to as “beggar,”15 prompting discussions on the relationship between Buddhist precepts and economic considerations in Buddhism.

Furthermore, maintaining an open attitude during the study is crucial; there are merits to both chanting the Buddha’s Name and Chan’s meditation, and one should not dismiss Chan’s practice in favor of Pure Land recitation. In establishing a connection between the Pure Land practice and the Avatamsaka Sūtra, Master Miaoguang highlighted that the Pure Land is synonymous with the Huazang (Flower Store) world, citing a verse from the “Samantabhadra’s Conduct and Vows” chapter: “Now that I have been reborn in that land (the Pure Land), I have fulfilled this great vow (the vow of Universal Virtue).”16 The realization of liberation requires the combined efforts of both the aspiration for liberation and the Bodhi mind.

For practitioners, the topic of ordination is inevitable, especially within the context of a Confucian-dominated cultural environment in China, which necessitates a harmonious interpretation. Master Miaoguang referenced the examples of Master Huineng and Milarepa. According to the “Platform Sūtra,” Master Huineng, while selling firewood, heard someone reciting the “Diamond Sūtra” and experienced an immediate awakening. Upon learning that it was the “Diamond Sūtra” from the Fifth Patriarch, Hongren, he resolved to pay his respects to him. “The Master often encouraged both monks and laypeople to hold the ‘Diamond Sūtra’ and realize their own nature, thus directly attaining Buddhahood. After receiving ten taels of silver from a benefactor to support his mother, Huineng settled his mother’s needs before seeking teachings from the Fifth Patriarch.” (《六祖大師法寶壇經》 2024, p. 348).

After completing his studies, Milarepa returned to his hometown, discovered his mother’s bones, and performed a seven-day liberation ceremony before cremating them. Having fulfilled his vows, Milarepa renounced the world, retreated to the mountains, and began a lifelong practice and wandering career, allowing the temple’s monks to focus on their studies and practice.

After the lecture, participants continued chanting the Buddha’s Name. Ideally, during the Buddha Recitation session, one should maintain a continual state of mindfulness of the Buddha in their heart.

5. The Pure Land Buddhism Is Living

5.1. An Interview with 9 Nuns and 2 Laypeople

During the process of the activity, we need to participate in the practice, and hence, the interview is conducted afterwards. The interview is designed by making a question list related to the practical and theoretical aspects about the Buddha retreat and teachings of Pure Land school into two categories of Nuns in the monastery and laypeople. We collected the feedback from the interview of these two parties and then syntheses their answers into a unified form. The following is our result of the interview:

5.1.1. A Record of the Interview with Nuns and Laypeople

1. How to understand the motto of the monastery: “the objective is rooted in Huayan, the practice is directed by precepts, and the pure land is the destination”?

Firstly, the central objective that “the dharma realm is a unity in the ultimate truth” and “there is no substantial obstacle among entities” interpreted in Avataṃska Sūtra, which manifests the inner Buddha nature of sentient beings are identical to the Buddha-realm, i.e., all things are the representation of the dharma nature (reality in Buddhist context). This view constitutes the foundation of the practice. Secondly, the practice should be consistent with precepts, by which we practitioners regulating our behaviors, utterances and thoughts, so that the afflictions caused by delusions will be overcome. For understanding this idea, we could imagine that the earth carries all things, and similarly the precepts guarantee the realization of the elaborated dharma, keeping the practical process on the right track. Thirdly, the reason why we hold the faith of birth in the Pure Land is that Amitabha had vowed to response to people who appeals to his name, for detaching from the samsara at the end of life and becoming a Buddha in his land. The three elementary teachings in this triple part structure complement one another, say, Huayan is the fundamental stage of insight, the practice according to precepts is necessary for the achievement, and the Pure Land is the ultimate destination. This triple structural motto constitutes the system for promoting the growth in both aspects of theoretical thinking and practice.

2. How to understand the expedient intention and the ultimate goal of nianfo?

Regarding the expedient intention, the recitation of “南无阿弥陀佛” is not difficult for no matter the young or old, wise men or the plain people, thus they can concentrate the mind through meditating the name of Buddha, planting the seed of elaborating. The specific goal of “birth in the pure land” responding to the instinctive pursuit of “transmission from suffering to happiness”, with the supportive power of Buddha, the inadequate self-competence of sentient beings can be overcome.

As for the ultimate truth, people need to know that the Amitabha Buddha is the manifestation of their own Buddha nature. In fact, the so-called “pure land” refers to the adornment of the heart of sentient beings. The main purpose of nianfo is to return the original condition of heart, revealing the inner Buddha nature, rather than approaching to another place. Nianfo is indivisible to all of other ways of Buddhist practices, where there is no distinction between “expedience” and “ultimate”, as Master Ouyi said in “the Essentials of Amitabha Buddha Sutra”: “if you capture the nature of the heart thoroughly, the perfect attainment of enlightenment will not withdraw.”

3. Does the religious experience of the response of appealing happen in the daily Buddha retreat?

Here, we need to clarify the meaning of responding to the appealing (ganying). The essence of ganying reflects a conditional that if your heart is pure, then it will happen. It is not excluded that some phenomenon may appear when the heart is purified during Buddha retreat. For example, the feeling of not oppressed will arise, the distractions decrease, as well as you can see Buddha in dream. It is noteworthy that this sort of experience should not be pursued, since the goal of attaining some special phenomenon may result in the obstacle in practice; the genuine ganying refers to the situation that the heart is identical to the spirit of Buddha, transforming from wave of afflictions to the calm and clear mind, from the mere individual private benefit to the compassion to others, which is the more fundamental “appealing and response” (感通).

4. What are the similarities and distinctions between Chan and Buddha retreat in practice?

It is common that various Buddhist ways of practice overlap with each other. In terms of the similarities between Chan and Buddha retreat, these two traditions share the goal of halting the delusive thoughts for seeing the nature of heart, through the mindful contemplating to focus on one thing. Therefore, the heart will be calmed down. In a subtle way, we restrict the scattered mind, meditating only one object during Chan practice. Likewise, nianfo requires us to concentrate on the sound of the name of Buddha we recite repeatedly again and again. These two methods both overcome the messy mind, as the result, “the power of concentration” can be cultivated.

If the similarities are interpreted on the level of fundamental teachings, the distinctions are mainly related to practical techniques. To realize the purpose of recognizing the nature of heart, we meditate the mind conditions or contemplate the deep meaning of emptiness during Chan; comparatively, nianfo is a specific event that is supportive in figuring out the truth of heart. By reciting the name Buddha, we receive the response from Buddha, on the base of Buddha’s vow. In this way, Buddha’s power constitutes the final achievement of the individual effort. Chan requires the capacity of inner meditating; thus it is suitable for the sharp minds. However, nianfo covers all kinds of people, especially for people at the age of dharma decline to initiate from an easy starting point.

5. How to deal with the relationship between nianfo and meditating emptiness?

Nianfo and meditating emptiness are not opposing to each other, while, in fact, these two methods are non-dual. The key to meditating emptiness is eradicating attachment, knowing that all dharma has no self-nature (svabhavah), so that the mind does not attach to the substantial distinction between “subjective mind” and the “objective Buddha”, avoiding the faith in the independent entity. In comparison, nianfo is to establishing something existential, which could be an expedient object in language, dwelling the mind at a point and then transforming from existence to emptiness. As “The Diamond Sutra” states that “fearless bodhisattvas should thus give birth to a thought that is not attached and not give birth to a thought attached to anything.” There is a dialectic insight that during the recitation of Buddha’s name, the mind does not attach to the existential image of Buddha. And correspondingly, in the meditation of emptiness, we do not deny the expedient meaning of nianfo. These two aspects combined together to result in “no attachment to Buddha during nianfo, and although no attachment, the image of Buddha still arise in mind.” (“念而无念,无念而念”).

6. How does master Ouyi fuse the practice of nianfo of Pure Land with the perfect teaching of Tiantai in “The Elementary of the Amitabha Sutra”?

The central idea of “the nature of one moment of mind” lays the foundation in Master Ouyi’s interpretation of pure land in the framework of “perfect teaching” of Tiantai Buddhism. “The subjective mind” “objective Buddha” and the “land where to bore at the end of secular life” do not beyond the realm of “the nature of one moment of mind”, in which there are “empty, provisional, and middle way” simultaneously. The glorious landscape of pure land is the manifestation of “one moment of mind” in essence. The so-called birth in pure land means that “if the heart is pure then the land is pure”, which has already demonstrated by the practice of perfecting. It is not the case that to pursuit other place out of the heart.

7. What is the reason for Master Ouyi saying that nianfo is “the deepest implication of the Avataṃsak Sūtra, and the crucial secret in the Lotus Sūtra”?

In terms of the consistency with the deepest implication of the Avataṃsak Sūtra, according to “the truth of the unity of dharma realm”, “the one moment of mind of Buddha’s name” is dependent on all of other dharma (by the infinity of dependent-origination). A representative example is that the ten great vows of Samantabhadra tell people the way to the Pure Land. Similarly, nianfo is a shortcut to fetch the “interpenetration of all phenomenon” in the teachings of Huayan. Regarding the crucial secret in the Lotus Sūtra”, “The Lotus Sūtra’s key theme is ‘opening the provisional to reveal the ultimate,’ dissolving expedient means into the One Vehicle.” This thought implies that all sentient beings can become a Buddha. According to this general principle, the fruit of Amitabha Buddha corresponds to the ultimate reality, the recitation of Buddha’s name is the provisional that connected with the vows of Buddha directly. Therefore, the causation and the result are indivisible as the Lotus Sūtra suggested. People can embark on the straight way demonstrated and suggested by Buddha, rather than experience the circuitous gradual process.

8. Do you feel disturbed in the Buddha retreat together with laymen and laywomen?

The laymen and laywomen are willing to participate this Buddha retreat activity, which suggests that they have good roots (kuśala-mūla). The sounds of recitation of Buddha’s name and our deeds promote each other rather than interference. Moreover, if we can focus on nianfo, the sounds from eternal environment are just like dreams, which could enhance the truth in the nature of heart, reaching the achievement of clear and quiet mind in the process of moving. Thirdly, as a dharma teacher, we have the responsibility to guide people how to make mind concentrated in this process according to their own situations. In this sense, the outer realm is supportive for training minds, and this is a specific practice of “klesha is indivisible from bodhi.”

5.1.2. The Interview with a Laity

1. Does the religious experience of the response of appealing happen in the daily Buddha retreat?

Some personal experiences caused by nianfo indeed happen in these years. At the early stage, the anxiety raised by life pressure was transformed during nianfo. I remember one time my mind became quiet during nianfo, and simultaneously I felt at home. It seems that the afflictions were eliminated by name of Buddha little by little, and since then, when I encounter with challenges, reciting the name of Amitabha Buddha helps me to get inner peace effectively. I also saw the glorious image of Buddha in a dream, which makes me happy after waking up. Although I know that phenomenon happened in a dream raised from my mind (that is neither objective nor eternal), this sort of experience enhances my faith in “empowering by Buddha”. The more important thing is the change in “nature of heart”, I was impatient and irritable in the past, while now able to be proactively aware of my mind and tolerant of others, and people around me say that my ‘temper has changed to be soft’, which may be the power of the subtle influence of chanting Buddha’s name.

2. How to deal with the relationship between the Pure Land in heart and Pure Land in other place which is mentioned in the Vimalakirti Sutra.

In “the Vimalakirti Sutra”, there is a proposition saying “As the minds of beings are purified, so the buddha-land is purified”. This thought is not contrary to “the pure land in other place”. The mind is the source or root of all dharma, so that if it is full of afflictions, even though in pure land, the glorious scene is still hidden. However, when the mind is purified, at the present moment you can feel the peace of “pure land”. The pure land in the remote location is a supportive condition, and the bliss world of Amitabha Buddha is the land of real reward, where is the perfect environment for Buddhist practice. When born there after the secular life, the sentient beings are capable of listening the Saddharma, doing the Buddhist practice, and finally attain the fruit of enlightenment.

3. How do you view the imperfections in real life after studying nianfo of Pure Land School?

Before I learnt Buddhism, I often complained about the shortcomings of reality (e.g., the difficulties in work, family conflicts, social injustice), but after I learnt to practice nianfo, my attitude towards life gradually changed. Knowing that the present situation is a manifestation of my past karma, and that imperfection is a representation of ‘impermanence’ rather than ‘the world is unfair to me’, I have become less angry and peaceful by accepting the present situation. The spiritual growth happens in the imperfection, when encountering conflicts, a single recitation of Buddha’s name can help me not to be wrapped up in emotions; when seeing the suffering of others, I will have the compassion of ‘wishing all sentient beings to be free from suffering and to be happy’, and transforming the imperfection of reality into a practice ground of ‘self-benefiting and altruistic’.

5.2. An Interpretation of the Collected Data

In the current context of Buddhism in China, the Pure Land school’s practice of reciting the Buddha’s Name is not merely a literary description in Buddhist texts; rather, it is actively implemented in monastic settings. This practice is rooted in the Amitābha Sūtra, which states:

“Śāriputra, one cannot attain birth in that land with few roots of good or a small store of merit. Śāriputra, if a good man or woman who hears of Amitāyus holds fast to his Name even for one day, two days, three, four five, six or seven days with a concentrated and undistracted mind, then, at the hour of death, Amitābha Buddha will appear with a host of holy ones. Consequently, when their life comes to an end, the aspirants’ minds will not fall into confusion, and so they will be born immediately in the Land of Utmost Bliss of Amitāyus.” (Inagaki and Stewart 2003, p. 93).

The seven-day period serves as a cycle for reciting the Buddha’s Name, emphasizing the importance of a focused mind. The state of “unwavering concentration” reflects a convergence of Pure Land and Chan practices. Beginners may experience discomfort while sitting in the lotus position, but the nun manager advised that it is permitted to adjust their sitting posture to maintain focus on the recitation.

The schedule for the recitation is intensive; however, the focused practice within the temple contrasts with the multitasking typical of daily life. The “Intensive Buddha Recitation” creates a relatively quiet environment that allows participants to concentrate on a singular task. This situation presents a unique aspect of Buddhist humor: While the time commitment may seem daunting, this focused practice serves as a form of rest. Through sustained training, the mind gradually quiets, leading to a paradoxical outcome: rather than feeling exhausted at the end of the day, participants often find that this “diligence” is, in fact, a restorative process.17 True concentrations do not lead to fatigue (Zhang and Li 2024).

The literature suggests that recitation has an emotional, cathartic effect, with some practitioners experiencing tears during the process. Although no interviews were conducted to verify the reasons for this emotional release, it can be inferred that participants may feel moved, find emotional expression, or experience a sense of peace. The tears observed are likely related to a sense of liberation within the context of the practice.18 This limitation underscores the need for further investigation; without interview data, the underlying reasons for these observations remain unverified. From a comparison perspective, there are “tears” in biblical context. In Luke 7:36–39 a woman anoints Jesus’ feet. “(She) stood at His feet behind Him weeping; and she began to wash His feet with her tears, and wiped them with the hair of her head; and she kissed His feet and anointed them with the fragrant oil.” The woman’s tears combined with her action of anointing Jesus’ feet show her faith.

As this research is mainly first-person perspective rather than the third perspective, it seems that there lacks an interview of the preceptees. However, a young adult accompanying us could be an interviewee. As for the question of why he came to the monastery during the spring festival holiday, he suggested that his family was in the Dacheng Monastery. His sister became a nun some years ago, then his mother followed his sister leaving the secular life as well. As he works in another place from hometown, only his father in home. At the time of retreat, his father played a role repairman in the monastery, so that he can meet daughter and wife in daily life. The young adult spent the spring festival with his family in the monastery. His family’s case is not the ordinary in the secular vision, while it also reflects a form of conciliation between the secular emotional bondage and the Buddhist doctrine; i.e., the strict monastic life requires one to leave home and enter the monastic group.

Combining theory and practice in recitation is essential. Guided by the principles of the Middle Way and Tiantai’s complete teachings, this approach can help individuals avoid the sense of exclusiveness of their current circumstances. The practice fosters a positive perception of the world, highlighting that “life is not lacking in beauty.”

6. Pure Land: A Spiritual Pursuit Rather than Attachment

James and Jonathan (Laidlaw and Mair 2019) and Yang and Libo (Song and Yan 2020) have described the short-term monastic retreat in detailed way. Although the activities happened at different time in different places, the Buddhist doctrine runs through these practices, and hence, the atmospheres expressed by the reports are similar to each other, and the interviewees also have the parallel experiences. Here we intend to interpret the retreat by figuring out the root in Buddhist scriptures to reveal how the words live in the current actual situation. Jones has laid a solid foundation and a panorama of the Pure Land story: “A story forms the heart and foundation of Pure Land Buddhism. Elements of the story are scattered across several texts, much the same way that the life of Jesus rests on four Gospels and a few other sources.”19 (Jones 2021). Although Jones work can provide a complete picture of the Pure Land, as the reality is like a flux, the content implied in the given elements is unfolded by the later Buddhist scholars. In this sense, we could go beyond the foundation. The further work of interpretation includes two aspects: one is to resort to the explanation of Ouyi Zhixu in Ming dynasty, who is an eminent Pure Land master (McGuire 2014, p. 31). And, more specifically, master Ouyi is the ninth “patriarch” of the Pure Land tradition (Jones 2019, p. 104). Another is that in the lectures this short-term retreat, the dharma teacher shows the Pure Land elements in Avatṃsaka Sūtra.

6.1. The Scriptural Basis of the Nianfo

The practice of Nianfo originates from the great vows of Bhikshu Dharmākara, who aspired to liberate sentient beings. In the “Sūtra on the Buddha of Infinite Life Delivered by Śākyamuni Buddha” (《佛說無量壽經》 2024, p. 265), Bhikshu Dharmākara expresses his vow to attain Buddhahood, promising that the sentient beings who are reborn in his Pure Land will cultivate and achieve liberation there. Among the forty-eight great vows, the twenty-first explicitly presents the Nianfo practice: “If, when I attain Buddhahood, sentient beings in the lands of the ten directions who, having heard my Name, concentrate their thoughts on my land, plant roots of virtue and sincerely transfer merits toward my land with a desire to be born there should not eventually fulfill their aspiration, may I not attain perfect enlightenment.” (Inagaki and Stewart 2003, p. 14). Through the power of Bhikshu Dharmākara’s vows, the Pure Land of the Western Paradise is established. Jones states that, in general, “nianfo” involves the oral chanting of Buddha’s name and visualization of Buddha-image. “For some meditators, this technique evolved into a process of visualizing the Buddha in great detail, and later it was supplemented by philosophical reflections on the ontological status of the buddha-image that one visualized and the relationship of this buddha with the practitioner.” (Jones 2021). Furthermore, “nianfo” is connected with other ways of practice.

The “joy” of the Pure Land differs fundamentally from the transient pleasures of the Sahā World, juxtaposed with suffering. According to the Buddha’s descriptions, the truths of suffering in the Sahā World do not exist in the Pure Land. As the Pure Land represents a sublime realm, the Buddha Śākyamuni leads sentient beings to be reborn there for further cultivation and ultimate liberation.

The legitimacy of the Western Pure Land is not limited to Pure Land scriptures; it is corroborated by references to the Nianfo practice in the “Lotus Sūtra” and the “Avataṃsaka Sūtra,” providing mutual corroboration among the texts. Thus, the Nianfo practice is central to Buddhist teachings both in theoretical and practical dimensions. The “Samantabhadra’s Conduct and Vows” section, derived from the version of forty chapters “Avataṃsaka Sūtra,” highlights its significance, with verses expressing the desire to remove all obstacles at the time of death and to see Amitābha, thereby achieving rebirth in the blissful realm. This indicates that the Forty Avataṃsaka reflects the guiding role of Samantabhadra’s vows in leading to the practice of Nianfo.

The Pure Land practice of reciting Amitābha’s Name, central to the Pure Land practice, is further validated by the “Lotus Sūtra.” The chapter “Ancient Accounts of Bodhisattva Bhaiṣajyarāja” discusses the Western Pure Land. It states:

“If there is any woman five hundred years after the parinirvāṇa of the Thatāgata who hears this Sūtra and practices according to the teaching, she immediately reaches the dwelling of the Buddha Amitāyus in the Sukhāvatī world, surrounded by great bodhisattvas, and will be born on a jeweled seat in a lotus flower. Never again troubled by the [three poisons] of greed, anger, or ignorance, by arrogance or jealousy, he will attain the bodhisattvas transcendent powers and the acceptance of the non-origination of all dharmas.” (Yuyama and Akira 2007, p. 285).

The term “Sukhāvatī world” refers specifically to Amitābha’s Pure Land. Thus, it can be observed that from specialized Pure Land texts to the “Avatamsaka Sūtra” and the “Lotus Sūtra”—the primary texts of the Tiantai School—there is a consistent doctrinal basis for the Pure Land practice of chanting. Additionally, the “Shurangama Sūtra” discusses the Pure Land practice in its chapter on the Mahasthamapratha Bodhisattva’s Recitation of the Buddha. Within the theoretical framework of Mahāyāna Buddhism, the method of single-mindedly chanting the Name of Amitābha to be reborn in the Pure Land is corroborated across various scriptures.

Moreover, the practice of Nianfo is not limited solely to the Pure Land School; it can also be regarded as a shared method among the Pure Land, Huayan, and Tiantai schools. While each sect of Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism emphasizes different theoretical aspects, there is a consensus across these traditions regarding the practice of chanting Amitābha’s Name.

6.2. The Spiritual Practice of Pure Land Thought (Mind & Emptiness)

After understanding the origins, canonical foundations, and doctrinal legitimacy of the Nianfo (recitation of Buddha’s Name) practice, we can explore the importance of one moment of thought to implement this in actual cultivation.

First, the Nianfo practice aligns with the fundamental principles of dependent origination, emphasizing that rebirth in the Pure Land is contingent upon fulfilling specific causes and conditions, i.e., the continuous and focused mind. Second, the practice involves continuously reciting the Name of Amitābha Buddha, which requires sustained attention. Third, one must achieve a state of “one mind without distraction,” referred to as the samādhi of Nianfo.

The term “one mind” here carries ontological significance. According to Master Ōuyi, “the mind of the present moment is not a physical lump, nor merely a shadow of conditions. It is timeless, without beginning or end, and remains unchanged amidst the myriad phenomena of the cosmos.” (Ouyi Zhixu 2014a, p. 382). The Chuandeng Master interprets the present moment’s mind as “the mind of ordinary beings when reciting the Buddha’s Name. It is minuscule and trivial yet encompasses the Buddha-lands beyond measure.” He further asserts that “this mundane mind arises from delusion; however, true understanding reveals the unity of the mind and the land.” (《淨土生無生論》 2024, pp. 382–83).

The “Treatise on the Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna” expands on the nature of sentient beings’ minds into three aspects: essence, characteristics, and functions, all reflecting reality itself. “Positively, the real is the efficient; negatively, the real is the non-ideal. The ideal is the constructed, the imagined, the workmanship of our understanding. The non-constructed is the real. The empirical thing is a thing constructed by the synthesis of our productive imagination based on a sensation. The ultimate real thing is that which strictly corresponds to pure sensation alone.” (Stcherbatsky 1962, p. 181) The real mind corresponds to the inherent nature or Buddha-nature, synonymous with existence—universal, imperishable, and unmoving.

In this context, “the Buddhas are the Buddhas within the minds of sentient beings, and sentient beings are the sentient beings within the minds of the Buddhas.” “The Western Pure Land is but a realm within my heart, and the Sahā World is also but a realm within my heart.” (《淨土生無生論》 2024, pp. 382–83).

From a practical perspective, “one moment of thought” is grounded in faith, encompassing self and others, cause and effect, and the nature of reality, all leading to the samādhi of Nianfo. Simultaneously, from an ontological viewpoint, “one moment of thought” represents ultimate reality; the Pure Land emerges from the thoughts of sentient beings without any subject-object duality. “One moment of thought” encompasses both the recitation of names and the realization of ultimate truth, including visualization practices that involve detailed contemplation of the Pure Land’s characteristics.

In the “The Sūtra on Contemplation of Amitāyus,” the Buddha presents sixteen contemplative items to Lady Vaidehi and Ānanda (Inagaki and Stewart 2003). Contemplation involves using the mind to construct an image of the Western Pure Land, based on the principle that “when the mind arises, various phenomena arise.” It is important to note that contemplation differs from delusion; it is an imagination rooted in the Buddha’s authentic teachings. While contemplating the Pure Land of Amitābha Buddha, one must also visualize the Buddha’s white hair tuft light. When asked, “Why should one also visualize the white hair tuft?” the answer is, “Both superior and inferior aspects are initially based on the white tuft. Thus, the wise consider the superior aspect of the tuft while examining the inferior aspect. The meaning here is elaborated.” (Ouyi Zhixu 2023, p. 83.)

The practice of chanting the Buddha’s Name inherently incorporates repentance, a theme explicitly addressed in both the Larger Sūtra and the Contemplation Sūtra (Inagaki and Stewart 2003). The essence of repentance lies in the reality of the mind; through repentance, one recognizes the original state of the mind:

“I, a disciple (such-and-such), sincerely repent. The Buddhas of the ten directions truly witness this. My nature, along with that of all sentient beings, is pure. The dwelling place of the Buddhas is called the realm of eternal rest and light, omnipresent in each moment and all phenomena. Yet I do not understand this and mistakenly conceive of myself. In the realm of equality, I make distinctions, and within the pure heart, I become attached. This inversion of the five desires leads to the cycle of birth and death, enduring through the three realms. I remain in this state, not seeking liberation.” (《往生淨土懺願儀》 2024, p. 491). The scripture states, “Vairocana pervades all places. His dwelling is known as the realm of eternal rest and light.” Therefore, it should be understood that all phenomena are none other than the Dharma of the Buddha. Yet I do not realize this and follow the stream of ignorance, thus perceiving impurity in enlightenment and becoming entangled in liberation. Today, I begin to awaken and repent (《往生淨土決疑行願二門》 2024, p. 146).

The initial practice of repentance primarily involved disclosing and regretting the violation of precepts. However, with the continuous spread of Mahāyāna teachings, the methods of repentance have become increasingly diverse, encompassing rituals of worship, chanting, praising the Buddha, reciting mantras, the five types of repentance, and meditation (Sun 2019, p. 22). Chanting the Buddha’s Name and repentance are practices aimed at attaining rebirth in the Pure Land, ultimately inseparable from liberation and the salvation of sentient beings.

The salvation of sentient beings necessitates teaching the Dharma in accordance with their foundational capacities and conditions, embodying the principle of skillful means or “teaching according to the capacity of the student.” This principle, as seen in the teachings of Chinese sects of Buddhism, reflects the Buddha’s skillful means in addressing different sentient beings with appropriate teachings, enabling them to accept the Dharma. In the “Lotus Sūtra,” the convergence of teachings into one and the revelation of the ultimate truth exemplify the implementation of skillful means. The “skillfulness” of teaching is achieved through the interaction between the teacher and the students. In this process, a higher standard is set for the teacher, or Bodhisattva, who must possess personal cultivation while also providing skillful means for the salvation of sentient beings, embodying the principles of “one mind, three contemplations” and “one mind, three wisdoms.” The principle of teaching is expressed in Buddhist contexts as “response and correspondence.” (Zhang 2023, pp. 311–14).

To achieve the pedagogical aim, various forms of salvation emerge corresponding to different types of sentient beings: firstly, in the practice of chanting the Buddha’s Name, Bhikṣu Dharmākara vows to establish the Pure Land to save sentient beings. Sentient beings in the ordinary realm of the Sahā world aspire to be reborn in the Pure Land to continue their practice and fulfill the aspirations of Samantabhadra to liberate others. As for the Bodhisattvas in the fruit stage, such as Avalokiteśvara, who is Amitābha Buddha’s left-hand Bodhisattva, they can manifest various forms to assist sentient beings in attaining liberation.

The practices of chanting the Buddha’s Name, visualization, and repentance constitute an organic whole, all aimed at attaining the state of samādhi in chanting the Buddha’s Name, thereby aligning with emptiness to achieve spiritual liberation. In the context of the intensive seven-day retreat, the daily morning prayers continue the regular practice and provide a theoretical foundation for the retreat itself. The forms of circumambulation, seated chanting, and meditation may appear somewhat monotonous; however, this simplified structure facilitates the Integration of chanting with Chan practices, preparing for the notion of “correspondence” within the Buddhist context.

7. Concluding Remarks

The “Intensive Buddha Retreat” aims to focus on chanting the Buddha’s Name over a week. “Diligence” is one of the “Six Paramitas” in Mahāyāna Buddhism, requiring a concentrated mind, often expressed in scriptures as “one mind without distraction.” In practice, this manifests as a structured schedule of intensive activities. Various static and dynamic practices—such as chanting, circumambulation, seated meditation, and prostration—facilitate focused chanting.

The Buddha being chanted is Amitābha, embodying the Pure Land teachings as revealed by Śākyamuni Buddha to his disciples. Through these concentrated activities, participants use the recitation of the Buddha’s Name to settle their minds. Chanting Amitābha’s Name is significant due to the deep karmic connections established during his bodhisattva path with the sentient beings of the Sahā world.

The practice of chanting is organized within monastic settings, led by a community of nuns, based on scriptural authority while respecting the autonomy of participants, whether they join out of curiosity or faith. Adherence to guidelines allows individuals to enter or exit the practice according to their own volition. The chanting method has traveled from India to China, continuing through the history of Chinese Buddhism to the present day. The practices described in Pure Land scriptures and Mahāyāna classics, such as the Avataṃsaka and Lotus Sūtras, remain vibrantly enacted in contemporary settings.

Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism, by its practical nature, unfolds as a dynamic process in which doctrines and methods from the scriptures are primarily transmitted through monastic communities. The profound teachings found in Buddhist texts provide legitimate justification and a solid foundation for these practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism is recorded in written form and expressed in lived reality. In this sense, the Pure Land school is living nowadays. Simultaneously, it is noteworthy that in the Pure Land practice, there should be the attachment to the imaginary pure land, which may result in the exclusive attitude towards the real-life. The pure land is compatible with and equal to this world in essence.

It should be acknowledged that this research lacks the sufficient interview of the participants, since during the process, on the one hand, in that atmosphere, people need to keep quiet and to concentrate on their own mind, so that the mindful intention results in the indifference of the surroundings; on the other hand, the researchers were not familiar with other participants, which could be a barrier of discussion with other people for knowing their personal experience. In the future research, this sort of limitation should be overcome.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and Y.L.; methodology, Y.Z.; resources, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; interview and data collection, J.W.; formal analysis, J.W.; investigation, J.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and Y.L.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by funded by the National Social Science Fund major project “Research on Civilization, Culture, and Building a Harmonious World” (12&ZD101). And the APC was funded by Yong Li.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. A Short Glossary

Nianfo: The Chinese translation of the Sanskrit word buddhānusmṛti was nianfo, a term burdened with ambiguity as to the form of practice it denotes. In many contexts, nianfo commonly signifies a mental recollection of a Buddha’s attributes. This discipline was also called nianfo sanmei (the samādhi of buddhānumṛti), an expression that reinforced a contemplative emphasis by alluding to the meditative trance in which the Buddha would appear. In yet other contexts, the term nianfo came to refer to invoking the Buddha’s name vocally. Despite this seeming contrast, it must be kept in mind that the recitation of the name, whether voiced or silent, chanted or spoken, was originally but one method of several in the mindful recollection of the Buddha (Buswell 2004, p. 699).

Three bodies: The Buddha of the origin teaching is often spoken of as the “eternal Buddha,” a term that, though easy to understand, flattens out a long and complex history of interpretation. Early Chinese exegetes disagreed over whether this Buddha’s life span was finite or infinite, or whether he was a Buddha in the dharma-body (dharmakaya), the recompense-body (sambhogakaya), or the manifested-body (ninmāṇakāya) aspect. In a dynamic synthesis, Zhiyi interpreted the original Buddha of the Lotus Sūtra as embodying all three bodies in one: The dharma body is the truth that is realized; the recompense body is the wisdom that realizes it; and the manifested body, a compassionate expression of that wisdom as the human Buddha who appeared and taught in this world (Buswell 2004, p. 473).

Emptiness: Within the nature of reality in Mahāyāna ontology, emptiness (śūnyatā) must be realized en route to enlightenment. The term śūnyatā has been glossed as “openness,” “inconceivability,” or “unlimitedness,” but is best translated as “emptiness” or “voidness.” It refers to what dharma (elements of reality) really are through what they are not: not as they appear, not conceptualizable, not distinguishable, and, above all, lacking permanent, independent, intrinsic existence (Buswell 2004, p. 809).

Tathāgata: Buddhism shares with other Indian system of religion and philosophy an interest in how the human self is constituted, including the nature and origin of the mental and the bodily broadly understood (nāmarūpa), as well as the nature of awareness (vijñapti) and consciousness (vijñāna). Early Buddhist speculation separated itself from other early śramaṇic systems by formulating unique theories about the embodied self (jīva and kāya) and the state of a liberated being (tathagata) as well as by formulating critiques of those who denied the consequences of intentional action (kriya), or of those who overemphasized the pervasiveness of moral causation (Buswell 2004, p. 680).

Notes

| 1 | “一極正覺,任機而通。” (萧齐) 昙摩伽陀耶舍 译,《無量義经》,《大正藏》, 第九册,第383頁. (《無量義經》 2024, p. 383). |

| 2 | “華嚴奧藏,法華密髓。一切諸佛之心要。” 《淨土十要》,《卍續藏經》第61冊,第646頁. |

| 3 | 江西廬山東林寺. |

| 4 | Archetype: the inherited part of the psyche; structuring patterns of psychological performance linked to instinct; a hypothetical entity irrepresentable in itself and evident only through its manifestations (Samuels et al. 1986, p. 26). |