Abstract

Anthropologists of religion are preoccupied with questions of identity, community, performance and representation. One way they cope with these concerns is through a reflexive examination of their ethnographic positionality in the field. This provides an opportunity to engage not only with “the other”, but also to explore their own identities and background. This article presents an autoethnographic analysis of Pride Shabbat, a special service held in June to celebrate the intersection of Judaism and queerness. The service took place at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah (CBST) as part of their 50th-anniversary celebration. Since the 1970s, CBST has been known as the largest gay synagogue in the world and provided diverse religious and spiritual services to the Jewish LGBTQ+ community. Based on my participation in this specific event in June 2023, I draw distinct differences between the Israeli Jewish LGBTQ community and the American Jewish LGBTQ community, such as issues related to ageism and multigenerational perceptions within the gay community, the internal dynamic for gender dominance, as well as diverse trajectories of queerness, religiosity and nationality. Symbolically, contrary to the common perception that the diaspora looks to the state of Israel for symbolic and actual existence, this inquiry sheds light on the opposite perspective; the homeland (represented by the ethnographer) absorbs and learns from the queer Jewish practices and experiences taking place within the diaspora (the American Jewish LGBTQ community). This is an opposite movement which reveals the cracks in the perception of the gay community as a transnational community, as well as the tense power relations between Israel and American Jewry.

1. Introduction

23 June 2023, Masonic Hall, New York City. Amidst resounding cheers accompanied by the sound of the shofar1, on the stage in front front of Congregation Beit Simchat Torah (CBST) Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum, welcomed in Pride Shabbat, commemorating fifty years of community resilience. This specific event did not take place in the synagogue building, but a special hall was rented for it. In addition, it was streamed live on Facebook2, so that CBST congregants across the country and around the world could virtually participate.

“Shabbat shalom—and Hag Samech”, Rabbi Kleinbaum proclaimed with palpable excitement, prompting the community choir to launch into song with “Open the Gates of Justice for Me”. Following the poignant piyyut, she delved into a retrospective of one of the most pivotal events in American and global LGBTQ history—the Stonewall Riots. Transitioning from history to the present, she then turned to address the audience, drawing parallels between the community’s modest beginnings and its enduring relevance today. In front of almost 1000 congregants and visitors, with her excited voice she declared:

Her sermon demonstrates one of the most difficult dilemmas of LGBTQ Jewish people: the negotiation between their religious identity and gender/sexual identity. This issue has prompted anthropologists to focus on contemporary diverse religious perceptions and practices of LGBTQ people and Judaism by bipolar axes: the conservative and progressive. For instance, when () examined Orthodox Jewish LGBTQ persons people and the way they established internal organizations and groups, () explores the meanings of queer mikveh for non-Orthodox transpeople. This contemporary post-modern egalitarian discussion is developed also in broader discourse about other religious and spiritual communities and their responses to diverse homosexual and non-binary identities (; ).“…It’s so moving to be here tonight in our fiftieth anniversary year given that CBST invented Pride Shabbat. So here we are celebrating Pride Shabbat which has become almost as ubiquitous as the rainbow flag, a part of part the way Jews celebrate pride, but it started here. And tonight, we celebrate history as we look forward to a great future. But in this observance of Pride Shabbat, we want to remember why and how it’s here in this last Friday night of every June.So, let’s remember back […] In 1973 a small group of people insisted on their rights both to be deeply Jewish and openly gay. Nobody had done that before 9 February 1973 in New York City. Before [that date] you had to make a choice if you wanted to remain to all connected to the Jewish community you had to completely hide your, sublimate, deny, whatever word you would like to use, being gay. And if you’re in a gay community there was there is no place to put those together. So those few people [...] changed history, and tonight we stand on their shoulders. We’re here knowing ex-distance out of Egypt and a certain amount of distance out of the terror but we know we are far from being in the Promised Land, and we know that we are facing hate today on the scale on what was faced on 1969. We are here together because like the truth that they told us we will together fight the evil that is confronting us in this country and around the world. Together, any identity we have, will be joined by the values of the commitment to fight against this evil, and will create the pathway to that promised land. So, we are here tonight because we are not just proud, we understand the power of community and the power of God’s sitting on our shoulders giving us the strength to do what we should do in this scary time that we find ourselves”.

This ethnographic study examines a special ritual Pride Shabbat for celebrating CBST’s 50th anniversary. This particular service is observed every June, the Pride Month, in Reform (Progressive) Jewish congregations around the world, in order to creatively promote discourse and liturgy about inclusion of LGBTQ people, such as new prayers, sermons and ritualistic performances to symbolize the egalitarian message: LGBTQ acceptance, diversity and solidarity. Through various kinds of liturgical and ritualistic changes in the Kabbalat Shabbat (and Ma’ariv) structure, this performance demonstrates how queerness reshapes Jewish tradition and uses Jewish text, narrative, and ritual as a political resource ().

By using autoethnographic method, based on my participation in the ritual, and return virtual netnographic observation in the ritual’s video, I examine how the performance illuminates diaspora-homeland relations in a queer context. Via view on American Jewish LGBTQ agenda, values, and socio-cultural perceptions, I point out how this diasporic performance invites me—as an Israeli gay male—to think about gender/sexual identity, affiliation and community both in religious and queer aspects. The reflexive writing points out different, sometimes contradictory, socio-cultural perceptions between the Israeli gay community and American Jewish gay community.

Ethnographers see autoethnography as textual opportunity and phenomenological reflexive introspection to clarify their relationship with the field, and by that, to summarize and conclude about the macro level (). The researcher’s standpoint during fieldwork, whether as an active participant or a passive observer, transcends mere rational choice; it is a framework that shapes the researcher’s sense of self. Autoethnography, as a qualitative analysis approach, facilitates and validates the integration of fieldwork with identity exploration ().

According to (), the anthropological perspective must be examined through the personal biography of the researcher himself. Following () who argues that in communities where sexuality is a controversial issue, the ethnographer must be reflexive during fieldwork, I suggest that even in religious communities that embrace homosexual sexuality, reflexivity should be preserved, since “the sexual and other intersecting identities and personal experiences of a researcher matter in research on vulnerable sexual minorities and should be a basis for critical reflections in qualitative feminist research” ().

Based on this analytic landscape, and especially as an Israel Jewish gay ethnographer, always busy with issues of identity and affiliation, I find this method so naturalistic for me. In my previous studies (, ), I delve into how scrutinizing my experiences both in the field and academia prompted me to develop a deeper understanding not only of myself but also of broader themes within the field. Through this exploration, I unearth insights into various realms such as queer politics, gender dynamics, and Israeli/diaspora relationships.

During my observation of CBST’s Pride Shabbat, I developed a “political queer Jewish imagination” that allowed me to realize the profound impact of ritual in establishing and reflecting a utopian reality where Judaism and LGBTQ identities intersect harmoniously. I felt a sense of belonging to a Jewish-LGBTQ community that transcends discriminatory categories such as national identity, age, or gender. However, there were also moments when this imagination revealed its limitations. I became acutely aware of the disparities between myself and LGBTQ American Jews, particularly in terms of gender perceptions, intra-LGBTQ politics, and the significance of the geographical location of the “Jewish homeland” in shaping their sense of belonging.

In this discussion, I refrain from using the concept of “exile” and instead employ the concept of diaspora, both within the Jewish context and the LGBTQ community. This choice stems from the notion that the shift from “exile” to diaspora is intricately linked to the experience of freedom and the acknowledgment of civil rights that diasporic individuals have attained in their host countries. As per (), the usage of the term “exile” regarding Jews became less prevalent only after the modern emancipation of Jews in the USA and parts of Europe. However, given that Jewish LGBTQ individuals still face disparities in terms of equal rights, can they accurately be characterized as “exiles?”.

Initially, the concept of “diaspora” was primarily associated with the Jewish diaspora, highlighting the dispersion of a nation across two or more locations following a significant traumatic event (). The distinct traumas giving rise to various diasporas have profoundly influenced each diaspora’s identity, shaping how they perceive themselves and how others perceive them. Trauma acts as a catalyst for practices that foster internal connections within the diaspora, both with the homeland and within the community. These practices may vary in nature, ranging from ethnic or religious to secular, or even combining elements of both (). Within this framework, I’m curious about how the trauma—specifically the queer experience of concealment, shame, and secrecy—not only fosters connections among LGBTQ communities globally, including those in Israel and the United States, but also may highlight specific differences.

While previous studies have examined Israel/diaspora relationship via national, ethnic, religious or political lens (; ), I decipher this connection by adopting a queer-gender perspective. Building on () observation regarding the perception of Moroccan Jews viewing their homeland as a symbolic center rather than solely the Jewish ethno-national space, namely the State of Israel, I can draw parallels to how the LGBTQ identity of American Jews shapes their perception of America as a home. For them, America represents more than just a geographical location; it serves as a place where a Jewish community can thrive while also embodying principles of queer acceptance and recognition. Hence, although this view on particular ceremony doesn’t reflect the entire challenges and holistic landscape of CBST’s work, this glimpse may contribute to contemporary research on intersection of religion non-heteronormative gender and sexuality.

2. CBST: Exploring Its Historical and Anthropological Research Significance

This passage is from Rabbi Ayelet Cohen’s book Changing Lives, Making History: Congregation Beit Simchat Torah (2014). Since the beginning of the 1970s, CBST has been one of the most influential non-aligned progressive Jewish synagogues in the inclusion of LGBTQ people. The clergy and liturgy, the social activities offered, and collaborations with various social non-governmental organizations have positioned the congregation as a very important arena in the struggle of the gay community for acceptance in society, and especially for LGBTQ Jews.“…These past forty years have witnessed, among other things, the impact of AIDS, breakthroughs in reproductive technologies and the gay baby boom, the emergence of queer and trans movements, and major Supreme Court decisions in support of equal rights. Through it all, CBST has been at the epicenter. Our members and clergy have been the authors, the activists, the leaders, the foot soldiers, the victims, the protagonists, the lawyers, the board members, the executive directors, the staff, the demonstrators, the litigants, the litigators, the lovers, the parents, the children, the grandparents, and the teachers. At the same time and in the midst of these profound changes, CBST has created a spiritual sanctuary where so many individuals have been nourished and transformed on the deepest level of their souls”.(Cohen 2014)

CBST was a site for previous studies, associated with the important ethnographic study of the Israeli anthropologist Moshe Shokeid. In his book A Gay Synagogue in New York (), Shokeid examined the interactions between the gay and lesbian people, and analyzed new communal projects and services for people with HIV/AIDS. While his research was conducted two decades ago, my study suggests a contemporary relevant view on the congregation, in time that reestablished and changed the mandate of the gay community. At that time, there were only two visible gay synagogues in the States (and maybe in the world), one in San Francisco and one in Los Angeles (; ). In addition, unlike Shokeid, who does not engage in a homosexual lifestyle and did not provide an autoethnographic-analytic perspective, my positionality as a gay ethnographer encourages me to reassess the “insider-outsider” dynamic.

Similarly, (, ), in his historic studies, claims that CBST was a significant agent in creation of queer Jewish liturgy, especially the response to AIDS pandemic. Creation of new liturgical texts and poems to people with HIV/AIDS signed the synagogue as a political space to struggle against hate and stigma, and established radical reaction against Orthodox ideology.

My initial work at CBST began during my residency during the High Holy Day season of 2021. Following this, I engaged in participatory observations within the congregation’s practices and conducted interviews with several congregants. For instance, my ethnography of CBST’s Tashlich ritual (casting off), clarified me how the urban space discovered as dominant category in exploring Jewish queerness ().

In my second visit to Manhattan in June 2023, I initially planned to celebrate another High Holy Day (season) with CBST, but, that time, from a different perspective—it was a Pride Month. However, my plans took a different turn as I found myself during the Pride Shabbat experienced a range of emotions—feelings of solidarity and belonging intertwined with a sense of otherness. This shift in my perception prompted me to engage in an autoethnographic study, acknowledging my own positionality and its influence on my analysis and interpretations. As I navigated these diverse emotions, my heightened awareness of my position allowed me to develop deeper insights about my Jewish-gay identity and perceptions.

During the service, I made a conscious decision not to write or record, but instead to immerse myself fully in the moment, focusing on experiencing the event firsthand. Engaging in small talk before and after the service allowed me to connect with participants in a spontaneous manner, without any predetermined agenda. Perhaps, I was also aware that the event was being broadcasted online, providing an additional layer of accessibility to those unable to attend physically.

Drawing inspiration from () ethnography in religious community, who advocated for sharing ethnographic findings with informants to blur the boundaries between ethnographer and informants, I found this methodological approach fitting for my autoethnographic endeavor. By immersing myself in the experience and engaging with participants in an open and transparent manner, I aimed to deepen my understanding of the community and its dynamics.

Therefore, after processing my experiences and thoughts into a cohesive narrative, incorporating various theoretical frameworks, I made the decision to share the resulting autoethnographic text with a key informant, Harold Levine, who is has been a member since 2013 and serves as CBST’s vice president. This act of reciprocity was important to me, as it allowed for a mutual exchange of experiences and perspectives. By inviting my key informant to engage with my interpretation of the events, I sought to bridge the gap between researcher and researched, fostering a closer alignment between the studied field and the researcher’s interpretation. This collaborative decision also expresses the dialectic interaction between diaspora and Israel, thus, demonstrates how the methodology is grounded in the field and not only the theory.

Furthermore, symbolically, this choice not only demonstrates methodological flexibility but also underscores one of the theoretical themes I explored regarding the interactions between gay men across different generations, as well as the dynamic between representatives of the Jewish diaspora and the one embracing Jewish ethno-national identity. (See Figure 1, CBST congregants during Pride Shabbat Service)

Figure 1.

CBST congregants during Pride Shabbat Service. This photo was taken by Gili Getz.

3. Reflections on Ageism and Gay Multigenerational

Pride Shabbat service began with a request to all Stonewall Riot participants to gather at the front of the stage to light Shabbat candles. “Anyone who came out of the closet in the seventies or before, or was among the first members of the community”, called Rabbi Kleinbaum. About twenty people slowly made their way through the crowd, excited, accompanied by thunderous applause, and blessed along with them: “to light a Shabbat candle. Amen!” (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Light Shabbat candles ritual. This photo was taken by Gili Getz.

The lighting of Shabbat candles is known as a feminine practice that takes place in the home space, and not a ritual used in the synagogue. However, in quite a few non-Orthodox communities the candle lighting ceremony is held also in the synagogue, because many community members do not perform this in their own homes, and also because women take an active part in worship and it’s another opportunity to embrace it. As Iosif reminds us “reclaiming biblical and traditionally religious tropes and reshaping them through a feminist lens could only be the stepping stone of Jewish feminism ().

In Judaism, the light symbolizes different ethos and values: heroism, commemoration, memory and nirvana. For instance, within synagogue, one of the efforts to uphold a connection to the ancient Temple involves the presence of the Ner Tamid, also known as the Eternal Light. It hangs above the Torah Ark, radiating continuously as a symbol of God’s eternal presence3. In this occasion, the lighting of the candles by pioneer gay representatives of Stonewall riots, the founding fathers and mothers of the gay struggle, was symbolic and important; the lighting of the proud instead of the darkness of hiding the LGBTQphobia.

I see this particular ceremonial choice to call the gay ancestors was to give a dimension of authenticity to this particular performance. Witnesses have a critical place in the preservation of memory and in the enterprise of commemoration4, and visibility is one of the important categories in marking the space as relevant and inclusive for LGBTQ+ people (). The presence of the congregants who initially attended Stonewall and later established the congregation is pivotal in legitimizing the community’s existence as a foundational institution within the broader narrative of the gay Rights movement, rather than solely within the context of the development of gay synagogues in America.

Furthermore, the concept of commemoration takes on a fresh interpretation as we consider the injunction to “keep and remember” the Sabbath day as holy, symbolized by the lighting of two Shabbat candles5. In this context, remembrance extends beyond traditional notions to encompass the acknowledgment of the pain of concealing one’s true self in the closet. It also entails preserving the emerging gay reality, advocating for progressive strides in liberation and the pursuit of gender and sexual freedom.

Beyond the intriguing politics of commemoration, I couldn’t shake the thought of their significance and what it means to embody the role of an elder gay men. Indeed, synagogues often serve as inclusive spaces that value and respect elders. Many congregations have a significant proportion of older members who play vital roles in establishing and maintaining religious identity. They serve as the custodians of tradition, passing down their knowledge to younger generations, and often continue to contribute to the community even after retirement. In addition, several studies in gerontology have examined the correlation between older age and the cultivation of religious-spiritual awareness, as well as the inclination towards religious practices as a therapeutic coping mechanism (; ).

However, I found myself awkwardly reflecting: when was the last time I found myself surrounded with elder gay individuals, particularly in a synagogue setting? What kinds of interactions or exposures have I had with them in queer spaces? How conscious am I of their experiences and perspectives? How do I perceive the substantial age gap between us, spanning almost more than three decades in gender/sexual context? These thoughts have lingered with me, intertwining with broader questions I’ve been exploring regarding my own age and the physical manifestations that accompany it.

Usually, the LGBTQ community prioritizes young representations and narratives, therefore old gays do not have much expression in LGBTQ spaces and they suffer from distinct manifestations of ageism (). The gay community is represented by colorful young people, the main organizations and institutions are intended for young people, therefore the old people fall between the gaps and suffer from double marginalization; both from the general society and from the gay community (). CBST challenges this ageism and prove the Jewish proverb “vehadarta pnei zaken” commandment call to respect the elderly (Leviticus 19:32).

During my fieldwork in a Reform congregation in central Tel Aviv (2014–2017), which was identified as a gay friendly place and was led by a lesbian rabbi, I had my first encounters with gay congregants who were in their sixties and seventies. It proved to be a deeply enriching and enlightening experience, providing me with insight into the history of the local LGBTQ community in Israel. As time went on, I realized that my interactions with these congregants were not only about learning from them but also about gaining a deeper understanding of myself. It forced me to confront my own fears about aging, including concerns about diminishing physical and cognitive abilities, and the apprehension of visibility and attractivity within the gay community as one ages, as () defines as “gay gym culture”. Despite these anxieties, I remained committed to fostering genuine and courageous friendships with them.

Indeed, my personal feelings of discouragement are indicative of a broader societal trend that transcends individual thoughts and emotions. The Tel Aviv gay scene sanctifies young athletic masculinity and the research on Israeli queer gerontology is tiny. For example, () discusses the impact of delayed coming-out on aging within the Israeli LGBTQ community. His autoethnographic study reveals tensions between concealing and expressing sexual identity in later life, competing social identities within the gay community, and the need for community-driven support.

Additionally, () conducted an ethnographic study on gay seniors, exploring their engagement within and beyond community centers. His findings reveal a spatial politics where individuals balance proximity to municipal authorities with asserting community influence internally, while also challenging existing norms and engaging with broader societal dynamics. This nuanced reality showcases a non-binary, dialectical tension, exemplified by the group’s operation at the community’s core, enabling political action within mainstream community constraints.

Unlike these former studies which overlooked the potential role of Jewish spaces in providing inclusion and support for elderly LGBTQ individuals6, CBST demonstrate an opposite situation; how a religious community could be a solution and a safe space for gay people who in their 50s and above. The ceremonial gesture in Pride Shabbat, which can be perceived as a corrective experience, and in general CBST provides a sense of reconciliation and dispelled any lingering guilt I felt, as I came to realize my own complicity in their exclusion, particularly through my participation in gay gym culture.

According to Harold Levine, CBST’s vice president, around half of CBST members are over 55, and many of those are still physically fit, working, traveling, hiking and enjoying themselves as much or more than they did in their 20s and 30s. In response to my perspective, he argues: “I am 67, but do not consider myself at all “elderly” […] and I do not see in NYC the same kind of divide between the younger “gym gays” and “gay elders” that I used to see. In NYC, “elderly” begins at 75 or so!”.

Levine’s claim highlights the localized nature of interpretation concerning the age dynamics within queer spaces and practices. While older gay men’s involvement in queer spaces may seem natural to a New Yorker, where distinctions between “young” and “adults” among gay men are less pronounced, it’s far from obvious to an Israeli gay ethnographer, hailing from a context that marginalizes older gay men.

Thus, my participation and interactions with CBST congregants reinforced the notion that queer spaces of belonging do not cease to exist as individuals age. Instead, they highlighted the potential for a Jewish and proud community to create a space that honors and values individuals of all ages; something which I would wish to happen also in Israel, but given the Orthodox monopoly I doubt it will happen. This diasporic gay synagogue, in essence, embodies the biblical principle of cherishing and respecting age. According to the familiar verse from the Psalms, “Al Tashliheni Leet Zikna” (Do not cast me off in the time of old age) become a real performance in front of my eyes, and not just a textual verse.

4. Hey, Men, Leave Them Women Alone

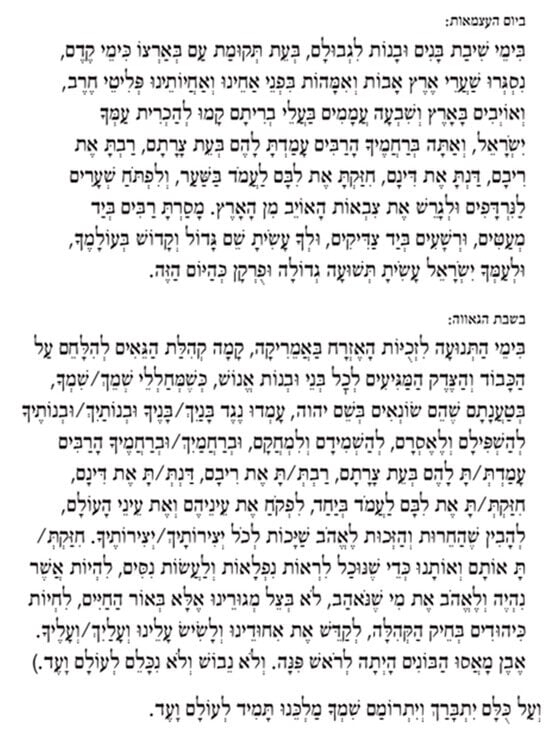

“This is our siddur and this is program (see Figure 3). You will have to use both. You also have a hairpin here for the kippa if you need it... even though you have short hair [laughs],” one of the Shabbat service organizers smiled at me at the entrance to the prayer hall. “Thank you very much, how beautiful”, I replied not before I admired the pride kippah on her head. “This is our community’s kippah. Where are you from?” She seen interested. “From Israel”, I replied and took the kippah off of my head and showed her my own colorful one. She smiled and summarized our small talk: “Well in Israel women don’t wear a kippah. Look how many women are here? You’ll get used to it quickly.” Figure 3. My kippah is placed on CBST Pride Shabbat’s program.

Figure 3. My kippah is placed on CBST Pride Shabbat’s program.

CBST is headed by clergy and lay leadership predominantly composed of queer women. Rabbi Kleinbaum, renowned as one of the first openly gay lesbian rabbis in North America, has been instrumental in leading the Jewish-queer discourse. Women hold significant roles within CBST committees and synagogue activities, reflecting an organizational ethos that emphasizes LGBTQ inclusion and empowerment, and a lesbian currently serves as President of the Board. This egalitarian approach is also an evident in the ritual representation of Pride Shabbat, where women predominantly occupy the stage and play key roles in organizing the event.

Since the end of the last century, CBST has undergone a transformation in the balance between genders in terms of leadership. () examined the women’s entrance into positions of spiritual and organizational leadership in a formerly male-dominated CBST. He draws the intricacies of women’s investment with authority in the public forum, and the reactions of men to the ‘intrusion’ into ‘their’ space—from resentment and protest to active acceptance.

Indeed, although the participation and leading of prayer by women is not now an unusual sight in non-Orthodox Jewish communities, it is still not a phenomenon that should be taken for granted in a historical genealogical Jewish view, when synagogues were and still continue to be a space that is mostly designed for and managed by men; both in terms of the patriarchal structure of the worship organization dominated by men, and from an ideological-theological point of view; the place where they turn to a God who Himself is seen as a male.

From () theology and () sociology emerge the importance of women’s intervention and shaping of Jewish worship and liturgy for the development of religious feminism. Indeed, the increasing participation of women and women’s leadership in Jewish worship and clergy since the middle of the last century doe undermine patriarchal orthodoxy. This trend sheds light on trends of feminization in liberal Judaism; a trend that led to the flight of men ().

Furthermore, the significant presence of women, and the feeling of being surrounded by lesbians, proved to me that I don’t often visit spaces where I meet women and especially not lesbian, bisexual or non-binary women. Most of my social encounters are with my peer group: gay men in my age. In general, gay male sub-groups often surround themselves with gay males, and usually, not typically in the sacred spaces. It certainly surprised me, and made me feel the sterilization of gay spaces and women. I remembered a discussion in the Israeli gay men community, that came up a few years ago about whether to allow women to enter homosexual male parties. There was a resistance among most of my peer group to including women in these party times.

I pondered whether my discomfort around gay women stemmed from a deep-seated reluctance towards women romantically or sexually. While I don’t have a definitive answer to this question, my experiences at CBST prompted me to reflect on my gender attitudes. As a cisgender gay man, I realized that my proud Tel Avivian perception may have inadvertently perpetuated a practice of excluding women in some way. This internal gender hierarchy between gay men and women in LGBTQ community, is described in ()’s conclusion: “it emerges that lesbian space is an exceptionally difficult homosexual space to claim since the more powerful and more established gay male community in that area does not particularly welcome women”.

Compared to the first years of the formation of the Israeli gay community, when the meeting between all identities was more frequent (), both due to the paucity of members who were outside the closet7 and because of the non-diverse scope of entertainment venues), today’s reality is one of polarization. () refers to the gendered politics of absence as a reification of lesbian, bisexual and transgender exclusion experienced by activists as a divestment of their power and voice.

Unlike the heterotopia heteronormative situation in Israel, which is particularly apparent in leisure culture and inter-subjective non-religious encounters, CBST demonstrates how Jewish space can contribute to challenge reproduction of power relationship between gay men and female, and creating a temporal queer “communitas”, as () coined.

Furthermore, the choice of a pride kippah demonstrates above all the visual attempt to merge gayness and Judaism through the material object that is transformatively appropriated for the mission (). In addition, it not marked only male heads, and, thus, emphasizes the reclaiming of masculine material object of the women in the performance. Also, our small talk exposed me to the CBST member’s understanding that this is not a common sight in Israel, implies a fragrance of achievement that has been successfully registered in America, compared to backward Israel. The saying about getting used to it also refer to underground gender tensions that the ritual practice manages to blur thanks to queer communitas.

In addition, the presence of women in public worship not only goes against a history of excluding women, but also breaks the automatic association of women with children. Often over the years they also used to mark the absence of the women and likewise the children—which marked this exclusion, since the children were not present in the prayer space. In this event, the disappearance of the children does not shed light on gender exclusion, some simply do not have children, some have older children, and also, it’s most common that NYC congregations, the children rarely attend the Friday evening services8.The intuitive search for the children during the prayer service reminded me of the child I was, how I would collect candy on Shabbat and at Bar Mitzvahs. It reminded me of the moments my mother joined in prayer only when she accompanied me; when I wasn’t there she wasn’t. I mean, I’m the one who made it possible for her to come to the synagogue, especially on high holidays.

So, the absence of the children, either because of the late hour at which the prayer takes place or due to life circumstances, does not necessarily indicate exclusion and gender discrimination. This is a move that challenges the historical conclusion of the exclusion of basically heterosexual cisgender women from the space of prayer which assumed that the absence of children condemned the absence of women. In CBST the presence of women is accompanied without children. In addition, in a conversation I also had with one of the congregants, he stated that quite a few youths are afraid to come to a gay synagogue because they do not identify as LGBTQ. That is, the mechanism of shame and removal did not disappear, and is restored even among queer families.

5. Trajectory of National/Queer Independence and Recognition

Just before the end of the service, Rabbi Kleinbaum invited the public to recite a special prayer for miracles (“Al HaNissim”) written for the congregation by Rabbi Ayelet Cohen (see Figure 4). There are different versions for this prayer (for instance, to Independence Day the state of Israel), and traditionally it recited as an addition to the Amidah9 and Birkat Hamazon10 on Hanukkah and Purim. On both holidays, it starts off with a short paragraph, beginning with the words for which it is named. After that, each holiday has a unique paragraph, describing the events for which that day is celebrated. According to (), this prayer affirms the people of Israel and their relationship to G-d, via a confession of praise, and empower motif of redemption, victory and salvation.

Figure 4.

From CBST’s Siddur B’chol L’vav’cha.

As an Israeli first-generation person, an observant Jew, I always felt conflicted about this text. On one hand, the concept of a miracle has been ingrained in my Israeli upbringing. Since childhood, the military narrative has revolved around the founding of Israel, portraying it as a miraculous existence of a Jewish state in the Middle East. It encouraged to recognized the militant power and the devotion of the soldiers who fell in battle: “Muscular Judaism”, coined by Max Nordau. On the other hand, I had a spiritual view on the establishment of the state of Israel—based on my belief that it’s a divine intervention. As a Jew, I would like to continue and feel belonging to historical tradition of “L’Shana Haba’ah B’Yerushalayim”—”Next year in Jerusalem”, the diasporic Jewish blessing to return to their homeland, as my father said in his kindergarten as a child in Casablanca.

However, at CBST, this prayer, written especially for CBST by Rabbi Ayelet Cohen, has undergone a transformation and praises another miracle—the miracle of queer freedom that allowed LGBTQ people to fight for equal rights. This queer version of a traditional piece of liturgy, which is considered by CBST clergy a major liturgical innovation, glorifies and praises the gay movement and emphasizes the importance of coming out of the closet, the political struggle for public recognition by virtue of the theological confirmation of creation in the image of G-d, B’tselem Elohim. In addition, the expressions describing the condemnation are manifestations of shame and concealment are taken from other liturgical texts. As Levine explains, “the liturgists at CBST attempted to identify what made a celebration “official” in Judaism, and determined that a special Al Hanissim was vital” (March 2024). In addition, the Shabbat morning service for Pride weekend uses the story of Noah and the rainbow as a Maftir reading in the Torah service, and the Haftarah for Machar Chodesh, the story of the love between David and Jonathan, is substituted for the regular text.

My excitement for discovering this prayer was great. Thoughts of queer suppression, exclusion and concealment floated through my mind. I didn’t believe in my pink dreams that I would find such a prayer in the Siddur of Shabbat service. In those moments, childhood scripts of LGBTQphobia flashed through my mind; I remembered how I used to pray for a miracle that maybe I wouldn’t be gay, that maybe the hatred would stop and I would feel equal. The liturgical text revealed itself to me as a particular life story, which is one of the few prayers during the evening that was read as it is in Hebrew, in my native language. I felt the power of the language, the everyday Hebrew in my mouth; in my ethno-national identity.

Surprisingly, on the very same page in the Siddur, right at the top, I found the Al Hanissim for the establishment of the State of Israel. This prayer version for the miracles as a national liturgy11 to praise the resurrection of the Jewish people in the State of Israel. Although this prayer was not recited at Pride Shabbat, since it’s not the Israeli Independence Day, I could not help thinking painfully of the irony that this page reflected in my eyes; the same disconnect between the two miracles; Israel vs. the American Gay Jewish community.

Another experience I’ve encountered is a critical reflection on my own country. It’s disheartening to witness some leaders in my country express concern about the continued existence of our society due to the recognition of LGBTQ individuals. Despite progress in the LGBTQ rights movement and the government’s efforts to portray Israel as a haven for LGBTQ individuals in the Middle East, we still hear frequent statements against the gay community, and discriminatory laws persist. I thought to myself, is it only in the diaspora, particularly in North America, that LGBTQ Jews can fully embrace the intersection of their identities? Are the conditions for this intersection primarily rooted in Jewish communities outside of sovereign territories?

Indeed, there was no denial of the existence of the State of Israel or any anti-Israeli atmosphere in the crowd, but during the entire prayer performance the word Israel, referring to the modern state, was not mentioned. The Israeli flag was also not hung, for example, like in other communities in the US. In general, CBST doesn’t hold back when it comes to criticizing the Israeli government, mainly due to political ideological circumstances in the issue of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the discrimination against the non-Orthodox currents and of course the discrimination against the LGBTQ community. On the other hand, CBST shows a keen interest in Israeli human rights issues and actively supports Israeli LGBTQ NGOs, such as Israeli gay organizations, often has Israeli speakers and fosters diverse Israeli/American partnerships. Additionally, following the October 7th attack, CBST has initiated various volunteering and philanthropic initiatives in support of diverse causes.

This diasporic embrace-contradiction, or erasure-presence, of Israel reflects the complicated relationship of the American Jewish community in relation to Israel, especially in the shadow of the BDS boycott movement identified with queer spaces. According to (), young American Jews are more critical of Israeli government policies compare to their parents, and feel more sympathetic towards the Palestinians than older American Jews. As a result, hostile reactions towards American Jews, who are always suspected of being pro-Israel, expand the discourse in the constructions of anti-Semitism and anti-Israelism (). In the queer context, “pinkwashing” fuels this trend, and also makes the general queer arenas unsafe for pro-Israel LGBTQ Jews ().

Furthermore, I wondered about the elusiveness of the “independence”/”recognition” category that emerges from this page; the essence of the state, the essence of the LGBTQ community and the essence/separation of the American Jewish community. On the one hand, the idea of Jewish peoplehood12 is an integral part of my identity concept in the way I perceive the Jews of the Diaspora. Especially as a first generation in Israel, as my father was born In Morocco, and mother in Israel, this encounter between natives and foreigners, between native and exile, has always characterized my home. Independence is indeed an important element in recognition, and perhaps precisely on this page, in the choice to place these prayers side by side, lies a prayer for the connection between the communities that are all disconnected so. Perhaps, is there any chance for Jewish (queer) peoplehood? Especially since the gay community itself is a transnational community, so maybe it will be able to reconnect Zion Jewry and New York Jewry?

According to Kochavi, the politicization of relations between Israel and the Diaspora, put the idea of community into a trap (). In Reconsidering Israel-Diaspora Relations () Reinharz argues that since Jewish unity does not exist, we should continue our search for an apt metaphor that reflects reality (p. 66): “given multiplicity of types of Jews, some of whom are organized intro groups, people interested in promoting Jewish peoplehood should devise ways of having these groups accept each other as Jews”.

Based on that, CBST, and symbolically the political landscape of these particular prayers, plays a crucial role in fostering the necessary disillusionment and awakening within the State of Israel, which should advocate for the recognition of Jews in all their diverse identities, encompassing gender and sexuality. This double recognition is essential for the sustained acknowledgment and independence of the Jewish people, starting with how they perceive themselves, and the LGBTQ identities among their in the Jewish state and abroad. In light of the mounting threat of anti-Semitism alongside LGBTQphobic expressions, this intersection may emerge as a pivotal and potentially existential solution.

6. Discussion

This autoethnographic study delves into my participant observation at the CBST Pride Shabbat, capturing my reflexive insights during the ritual and shedding light on several themes. These include the socio-cultural significance of multigenerational dynamics within the gay community, the intricate dynamics between gay men and gay women, and the complexities of Israeli-American tensions within both national and queer contexts. Throughout this exploration, I uncovered how my own homosexual identity, along with my Israeli habitus, influenced my prayer experience, prompting profound inquiries into the communities I am part of—both the Jewish community and the Israeli gay community.

This queer autoethnography offers a profound reflection, delving into both my personal gay identity and the broader LGBTQ community, uncovering the mechanisms of instructional paralysis and fragmentation. In contrast, CBST is portrayed as confronting these obstacles head-on, skillfully navigating the complexities of heterotopia. The congregation nurtures a unified religious-queer environment that transcends age and gender barriers. This starkly contrasts with Israeli LGBTQ culture, which frequently revolves around secular, segregated spheres, encompassing separate venues for gay men and women, as well as meager specialized spaces for elderly LGBTQ members.

() in his ethnographic work examined SAGE (founded as Senior Action in Gay Environment) a group for men whose weekly meetings were observed in New York City, emphasized how this kind of particular session can create “affective fellowship”. I would like to continue this claim and assert that the emotional brotherhood can be created not only among the old participants themselves, but also in an encounter between a young gay and an older gay and gay man and gay women, when the community space allows this and supports it, as CBST is demonstrated.

Thus, following () who invite us to think about the inherent connection between queerness and Jewishness, I found myself in a more conservative position, seeking to shine a light on the structure (the state/the community) instead of on the individual, who still strangely perceives the appearance of older women and gays—thereby affirmed my familiar perceptions regarding age and gender in the Israeli gay community. Did I become a participant in my intuitive reactions to those exclusionary, supervisory and regulatory moves? Or are these innocent moments of “standing up for the difference”?

Encountering American queer Judaism compelled me to reassess my perceptions of both my Israeli Judaism—recalling life experiences from synagogue and acknowledging religious beliefs, such as the notion of miracles—and my perceptions of homosexuality and the Israeli gay community. Thus, in contrast to () suggestion that ethnographic Jewish reflexivity develops through encounters with non-Jews, I contend that encounters with “other Jews” or “other queer identities” also stimulate introspection and prompt inquiries about identity, belonging, and community.

Perhaps, this discussion highlights differences and similarities with previous autoethnographic reflections and the experiences of other insider (or quasi-insider) Jewish ethnographers. For instance, () noted that his Jewish background meant that he was ‘neither fish nor fowl’ in the field, which proved to be both an obstacle and an opportunity for conducting the research. This polar experience, relevant to my own, serves to challenge the conceptual use of the term ‘community’, “which encompasses a great deal of diversity but obscures the nuanced differences that can apply to a social body,” as () concludes. In () ethnography, she presented reflexive insights as a non-Orthodox Jew studying Orthodox Jews, demonstrating how this contributed to her anthropological understanding.

In my case, though, the clear distinction is blurred because I am not studying a liberal religious community, which makes the distinction between “me” and “them” even more challenging. It’s not merely an egalitarian social agenda or a desire for a religious communal affiliation that could set me apart from my informants (categories that Fader suggested for differentiation). Instead, it’s the very performance itself—the rituals or other ceremonial elements—that might also emerge spontaneously and jeopardize my perceived ethnographic role or my religious identity and beliefs.

By the analysis of my prayer experience, which sheds light on intra-communal and extra-communal tensions and trajectories, the question floats, if the whole year is “proud”, and the discourse on acceptance and inclusion characterizes all the religious and social services that the synagogue provides to its members, why is there a need for a dedicated ceremony—on Pride Shabbat? Hasn’t the goal already been achieved in the fact that the synagogue is a proud house of prayer?

The answer is maybe in () latest book Fragments from an Ethnographic Mosaic: Encounters, Reflections, Insights, as he asserts: “I continue to visit CBST events whenever I come to New York, but I have to admit, I wouldn’t choose CBST as a fascinating subject for research these days. With the achievements of gentrification and the legitimacy that the community won for them, but the radical unique dimension—perhaps some would argue the “exotic”—of the institution that intrigued me when I first came to it” (84). Perhaps, the answer is negative. The ritual as a temporary temporal space can nevertheless forget moments of violence and hostility and produce a different utopia ().

According to Heaphy “our sociological narratives about lesbian and gay reflexivity tend to be underpinned by overly affirmative and normative projects, and are often narratives about how lesbian and gay life should be. Our narratives about lesbian and gay reflexivity sometimes confuse analysis with prescription, and actualities with potentialities” (p. 188). The autoethnographic analysis can help navigate this epistemological challenge by revealing a dialectical interplay between utopia and dystopia, between the familiar and the foreign, and between sovereignty and diaspora.

Symbolically and metaphorically, the closeted experience of LGBTQ individuals—characterized by concealment, alienation, and shame—can be likened to a state of exile. However, the act of coming out is not a singular event; rather, it necessitates repeated instances of disclosure throughout one’s life (). Thus, coming out of the closet mirrors emerging from exile or establishing a transient state of estrangement. This notion was palpably evident in the tension I encountered among CBST members—a tension that illuminates the dialectic between centrality and periphery, familiarity and otherness, and belonging and alienation, both internally and externally.

In sum, based on the autoethnographic descriptions, this study may continue previous ethnographic insights according to which studies in synagogues may shed light on social trends and significant cultural transformations that occur outside the moment of prayer itself, and teach about mechanisms of supervision and authority, continuity, change, identification and multigenerational (; ). However, the way to reveal this cannot be skipped with the ethnographer him/herself participating in the synagogue for the experience of the occurrence. I shall suggest that the ethnographic present is not external to the ethnographer, but also internal; this is how from the inside I learnt about the outside, and recognize identifications, cracks and ideological clashes.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Ariel University (AU-SOC-EBL-20220823, approved on 22 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | An ancient musical horn which according the Jewish tradition is hearing on high holidays rituals. |

| 2 | https://www.youtube.com/@BeitSimchatTorah (accessed on 1 March 2024). |

| 3 | Although that such a custom exists in many synagogues, that was not the case in the ancient temple. |

| 4 | According to () Holocaust survivors play a crucial role in preserving the memory and in the struggle to eradicate the Holocaust, meeting them is critical to justifying the narrative of destruction and pain. |

| 5 | In Exodus (20:8)—“Remember (zachor) the day of Shabbat and make it holy”. This encompasses all of the positive commandments associated with sanctifying Shabbat. In Deuteronomy (5:12) the people are instructed, “Keep (shamor) the day of Shabbat and make it holy”. This encompasses all of the negative prohibitions associated with Shabbat. To represent acceptance of both aspects of Shabbat observance, we light two candles (Tur and Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chaim 263:1). |

| 6 | I assume that these previous conclusions stem from the prevailing Orthodox Jewish consciousness within the Israeli public, including among researchers who may self-identify as “secular” and do not regularly engage in religious practices at the synagogue. |

| 7 | It’s important to note that lesbian women tend to come out later compared to men (). |

| 8 | It’s important to mention that there are children among CBST families and couples, and the congregation offered rite of passages for them. |

| 9 | Also called the Shemoneh Esreh ‘-eighteen’ is the central prayer of the Jewish liturgy. |

| 10 | Grace After Meals. |

| 11 | A national liturgy includes a set of rituals and texts that use symbolic and stylistic elements drawn from traditional religion and national symbolism to provide rhetorical, interpretive and mobilizing content for the national ideology and rituals of the state. According to () this symbolic system seeks to help strengthen the victorious image of the state and takes part in the patriotic effort to imagine the state as a sacred partnership. |

| 12 | This term “Jewish Peoplehood” actually emerged in the United States in the 1930s, where it was introduced by American Jewish leaders, most notably Rabbi Stephen Wise and Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, with close ties to the Zionist movement. Although the attempt to define Judaism “as a civilization” is more comprehensive and reflets the globalization than the definition “Judaism is a religion”, as the concept of Jewish Peoplehood seeks to promote, this is not enough and does not make a real contribution; neither in the linguistic sense (that of the phenomenon) nor with the aim of realizing her sociological ambition. It is an inclusive attempt to maintain a unifying axis that will maintain an ethno-national bond that crosses borders and continents. However, this definition obscures power struggles, local identity politics, new concepts of space, immigration and communities (). |

References

- Adler, Rachel. 1998. Engendering Judaism: An inclusive Theology and Ethics. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, Erick. 2010. Muscle Boys: Gay Gym Culture. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anteby-Yemini, Lisa. 2023. Negotiating Gender and Religion: Comparative Perspectives from Judaism and Islam. Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 39: 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averett, Paige, Intae Yoon, and Carol L. Jenkins. 2013. Older lesbian experiences of homophobia and ageism. Journal of Social Service Research 39: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avishai, Orit. 2023. Queer Judaism: LGBT Activism and the Remaking of Jewish Orthodoxy in Israel. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar. 2021. “Let Us Bless the Twilight”: Intersectionality of Traditional Jewish Ritual and Queer Pride in a Reform Congregation in Israel. Journal of Homosexuality 68: 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar. 2022a. “Casting Our Sins Away”: A Comparative Analysis of Queer Jewish Communities in Israel and in the US. Religions 13: 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar. 2022b. The sacred scroll and the researcher’s body: An autoethnography of Reform Jewish ritual. Journal of Contemporary Religion 37: 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar. 2024. Navigating Academic Identity: Autoethnography of Otherness and Embarrassment Among First-Generation College Students. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Rafael, Eliezer, Judit Bokser Liwerant, and Yosef Gorny, eds. 2014. Reconsidering Israel-Diaspora Relations. Boston: Brill, vol. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, Steven. 2005. Jewish diaspora in the Greek world. In Encyclopedia of Diasporas. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Boyarin, Daniel, Daniel Itzkovitz, and Ann Pellegrini, eds. 2003. Queer Theory and the Jewish Question. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Heewon. 2007. Autoethnography: Raising Cultural Consciousness of Self and Others. In Methodological Developments in Ethnography. Edited by Geoffrey Walford. Bingley: Emerald, pp. 207–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yung Y., and Harold G. Koenig. 2006. Do people turn to religion in times of stress?: An examination of change in religiousness among elderly, medically ill patients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 194: 114–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffey, Amanda. 1999. The Ethnographic Self: Fieldwork and the Representation of Identity. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Robin. 2022. Global Diasporas: An Introduction. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crasnow, Sharon J. 2017. On transition: Normative Judaism and trans innovation. Journal of Contemporary Religion 32: 403–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Monteflores, Carmen, and Stephen J. Schultz. 1978. Coming out: Similarities and differences for lesbians and gay men. Journal of Social Issues 34: 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkwater, Gregg. 2020a. Building Queer Judaism: Gay Synagogues and the Transformation of an American Religious Community, 1948–1990. Doctoral dissertation, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Drinkwater, Gregg. 2020b. Queer Healing: AIDS, Gay Synagogues, Lesbian Feminists, and the Origins of the Jewish Healing Movement. American Jewish History 104: 605–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elman, Miriam F. 2020. Antisemitism and BDS on US campuses: The role of Jewish Voice for Peace. Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism 3: 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Or, Tamar. 1992. Do you really know how they make love? The limits on intimacy with ethnographic informants. Qualitative Sociology 15: 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppler-Hattab, Raphael. 2023. Gay Aging in Israel: An Activist Autoethnographic Perspective. Sexuality & Culture 27: 1939–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fader, Ayala. 2007. Reflections on queen Esther: The politics of Jewish ethnography. Contemporary Jewry 27: 112–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, Jackie. 2016. A Jewish Guide in the Holy Land: How Christian Pilgrims Made Me Israeli. Indiana: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Jackie. 2022. Above the Death Pits, Beneath the Flag: Youth Voyages to Poland and the Performance of Israeli National Identity. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, Ofira. 2018. Innovative ordinariness and ritual change in a Jerusalem Minyan. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 17: 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesler, Wil, Thomas A. Arcury, and Harold G. Koenig. 2000. An introduction to three studies of rural elderly people: Effects of religion and culture on health. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 15: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartal, Gilly. 2015. The gendered politics of absence: Homonationalism and gendered power relations in Tel Aviv’s Gay-Center. In Lesbian Geographies: Gender, Place and Power. Edited by Kath Browne and Eduarda Ferreira. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, Lawrence A. 1979. The Canonization of the Synagogue Service. South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iosif, Stefana. 2019. From the Shabbat Candle to the Light of Freedom: The Jewish American Woman and Feminism. InterCulturalia 2018: 23. [Google Scholar]

- Kasstan, Ben. 2016. Positioning oneself and being positioned in the ‘community’: An essay on Jewish ethnography as a ‘Jewish’ ethnographer. Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis 27: 264–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Arsalan. 2018. Pious masculinity, ethical reflexivity, and moral order in an Islamic piety movement in Pakistan. Anthropological Quarterly 91: 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochavi, Noga. 2020. Jewish Peoplehood: A Concept in a Trap. Moreshet Israel Journal 18: 208–185. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, Nissim. 2008. Ethnic synagogues of Mizrahi Jews in Israel: Ethnicity, orthodoxy, and nationalism. Sociological Papers 13: 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, André. 2001. Center and Diaspora: Jews in late-twentieth-century Morocco. City & Society 13: 245–70. [Google Scholar]

- Maake, Tshepo. 2021. Studying South African Black Gay Men’s Experiences: A First-Time Researcher’s Experience of Reflexivity in a Qualitative Feminist Study. The Qualitative Report 26: 3771–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahomed, Nadeem. 2016. Queer Muslims: Between orthodoxy, secularism and the struggle for acceptance. Theology & Sexuality 22: 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumunyane, Keneuoe, and Dipane Hlalele. 2022. Geographies of becoming: Exploring safer spaces for coming out of the closet! Cogent Social Sciences 8: 2061685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meszler, Joseph B. 2009. Where are the Jewish Men? The Absence of Men from Liberal Synagogue Life. In New Jewish Feminism: Probing the Past Forging the Future. Edited by Anita Diamant. Woodstock: Jewish Lights Publishing, pp. 165–74. [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, Amy K. 2013. Colours of the Jewish rainbow: A study of homosexual Jewish men and yarmulkes. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 12: 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misgav, Chen. 2016. Gay-riatrics: Spatial politics and activism of gay seniors in Tel-Aviv’s gay community center. Gender, Place & Culture 23: 1519–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pianko, Noam. 2015. Jewish Peoplehood: An American Innovation. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Plaskow, Judith. 1991. Standing Again at Sinai: Judaism from a Feminist Perspective. New York: Harper One. [Google Scholar]

- Podmore, Julie A. 2001. Lesbians in the Crowd: Gender, Sexuality and Visibility along Montreal’s Boul. St-Laurent. Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 8: 333–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, Annette, Nigel Morgan, and Diane Sedgley. 2002. In search of lesbian space? The experience of Manchester’s gay village. Leisure Studies 21: 105–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, Jason. 2015. Pinkwashing, homonationalism, and Israel–Palestine: The conceits of queer theory and the politics of the ordinary. Antipode 47: 616–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokeid, Moshe. 2001a. Our group has a life of its own: An affective fellowship of older gay men in New York City. City & Society 13: 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Shokeid, Moshe. 2001b. ‘The Women Are Coming’: The Transformation of Gender Relationships in a Gay Synagogue. Ethnos 66: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokeid, Moshe. 2002. A Gay Synagogue in New York. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shokeid, Moshe. 2022. Fragments from an Ethnographic Mosaic: Encounters, Reflections, Insights. Jerusalem: Carmel Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Anthony D. 1992. National identity and the idea of European unity. International Affairs 68: 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Anthony D. 2003. Chosen Peoples: Sacred Sources of National Identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, Charles. 2018. Moral judgement close to home. Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 26: 117–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toktaş, Şule. 2006. Turkey’s Jews and their Immigration to Israel. Middle Eastern Studies 42: 505–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Victor. 1983. Passages, Margins, and Poverty: Religious Symbols of Communitas. Champaign: Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc., pp. 327–59. [Google Scholar]

- Waxman, Dov. 2017. Young American Jews and Israel: Beyond Birthright and BDS. Israel Studies 22: 177–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingrod, Alex, and André Levy. 2006. Social thought and commentary: Paradoxes of homecoming: The Jews and their diasporas. Anthropological Quarterly 79: 691–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkens, Jan. 2020. “Jewish, Gay and Proud”: The Founding of Beth Chayim Chadashim as a Milestone of Jewish Homosexual Integration. Potsdam: Universitätsverlag Potsdam, vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Woody, Imani. 2017. Aging out: A qualitative exploration of ageism and heterosexism among aging African American lesbians and gay men. In Community-Based Research on LGBT Aging. London: Routledge, pp. 145–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yonay, Yuval. 2022. “It Did Not Come Up”: The Double Life of a Mizrahi Single Man. Zmanim 147: 54–75. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).