Imperial Identity and Religious Reformation: The Buddhist Urban Landscape in Northern Wei Luoyang

Abstract

1. Introduction

| 代人傷往二 | Lamenting the Past, On Behalf of Others: No. 2 |

| 庾信 | Yu Xin |

| 雜樹本惟金谷苑, | The jumbled trees were once Golden Millet Garden, |

| 諸花舊滿洛陽城。 | Various flowers used to blossom all over Luoyang city. |

| 正是古來歌舞處, | This was the site of singing and dancing in ancient times, |

| 今日看時無地行。 | When you gaze at it today, there is no path for access. |

至武定五年,歲在丁卯,余因行役,重覽洛陽。城郭崩毀,宮室傾覆,寺觀灰燼,廟塔丘墟,牆被嵩艾,巷羅荊棘。… 始知麥秀之感,非獨殷墟,黍離之悲,信哉周室!

In the fifth year of Wuding reign (547 CE), the year of Dingmao, I traveled and visited Luoyang again due to some official affairs. The city walls were destroyed, the palaces were torn down, the monasteries were burnt to ash, the pagodas were ruined, the walls were covered with weeds, and the lanes were overgrown with brambles. … I then realized that the sigh of Wheat is not only related to the devastation of Yin; the sorrow of Millet, is truth for the Zhou. (In this paper, I made minor modifications to Yi-t’ung Wang’s translation of Luoyang qielan ji and tried to be more literal; I changed Wade-Giles spellings in Wang’s translation to pingyin. I added the page numbers of Yi-t’ung Wang’s version for reference.

2. Representation of Northern Wei Imperial Identity

2.1. Cultural Memory of Pre-Luoyang Northern Wei

太祖欲廣宮室,規度平城四方數十里,將模鄴、洛、長安之列。

The Great Emperor wanted to enlarge the palace and halls, and he ordered Pingcheng to be 10 li on each of the four sides to resemble Ye, Luoyang (of Wei and Jin time), and Chang’an.

城西有天壇,立四十九木人,長丈許,白幘、練裙、馬尾被,立壇上,常以四月四日殺牛馬祭祀,盛陳鹵簿,邊壇奔馳奏伎為樂。

There was a Heaven Altar in the west of the city. Forty-nine wood men have been erected, each about one zhang high. They wore white headdress, silk skirt and horsetail quilt, standing on the altar. [Northern Wei people] always kill cows and horses on the fourth day of the fourth month to sacrifice. Grand chariots and guard of honor were displayed, and on the side altars, there were horse running, and music playing for entertainment.

其郭城繞宮城南,悉築為坊,坊開巷。坊大者容四五百家,小者六七十家。每南坊搜檢,以備奸巧。

To the south of the palace, there was a walled district. It was filled with residential wards and the wards were connected with the lanes. The bigger wards could accommodate four to five hundred households, the smaller ones could accommodate sixty to seventy households. In the south house of each ward, there were inspecting corps to prevent the fraudulent and deceitful.

(元)嘉表請於京四面,築坊三百二十,各周一千二百步,乞發三正復丁,以充茲役,雖有暫勞,姦盜永止。詔從之。

Lord Yuan Jia presented a memorial to suggest the construction of 320 wards around the imperial city, each of 1200 steps in circumference. He also asked for three governors and numerous laborers to serve for this construction. [He thought] this might be temporarily labor consuming but would stop the fraudulent and thieving forever. The emperor permitted.

廟社宮室府曹以外,方三百步為一里,里開四門,門置里正二人,吏四人,門士八人,合有二百二十里。

Excluding monasteries, shrines, palaces, and such government buildings as ministries and bureaus, each ward was the equivalent of three hundred square paces. It also had four gates. For each gate, there were two ward superintendents, under which were four assistants and eight wardens. There were altogether two hundred and twenty wards.

市東有通商達貨二里。里內之人,盡皆工巧。屠販為生資財巨萬。

市南有調音樂律二里。里內之人,絲竹謳歌,天下妙伎出焉。

市西有延酤治觴二里,里內之人多釀酒為業。

市北慈孝奉終二里,里內之人以賣棺槨為業,賃輀車為事。

To the east of the marketplace were the two wards, Ward of Conducting Trade and Ward of Shipping Merchandise. All residents of these wards were shrewd, making living as butchers or tradesmen. They were wealthy, owning thousands of coins.

To the south of the marketplace were the two wards, Ward of Musical Tones and Ward of Musical Notes. All residents of these wards were musicians and singers. The most skillful performing artists of the empire came from here.

To the west of the marketplace were the two wards, Ward of Wine-buyer and Ward of Wine-server. Residents of these wards were mostly in the business of making wine.

To the north of the marketplace were the two wards, Ward of Motherly Love and Filial Piety, and Ward of Enshrining the Deceased. All residents of these wards were sellers of inner and outer coffins and handlers of hearse rentals.

(常景)又共芳造洛陽宮殿門閣之名,經途里邑之號。

Chang Jing, in cooperation with Liu Fang, designated names for the palaces, halls, gateways and towers, as well as titles of roads, streets, lanes and districts.

2.2. Imperial Identity and Architectural Elements

中有九層浮圖一所,架木為之,舉高九十丈。上有金剎,復高十丈,合去地一千尺。去京師百里,已遙見之。

Within the precincts [of the monastery) was a nine-storied stūpa, built of wood. It rose ninety zhang above the ground. There was one gold spire on the top of it, which was another ten zhang. The total height added up to one thousand chi. From hundreds li outside the capital city, people were able to see it.

浮圖北有佛殿一所,形如太極殿。

寺院墻皆施短椽,以瓦覆之,若今宮墻也。四面各開一門。南門三重,通三閣道,去地二十丈,形製似今端門。

North of the stūpa was a Buddhist hall, which was shaped like the Palace of the Great Ultimate.

The walls of the monastery were all covered with short rafters beneath the tiles in the same style as our contemporary palace walls. There were gates in each of the four directions. The south gate was three-storied, each connected with an archway, and rising twenty zhang above the ground. It was shaped like the present-day Gate Duan (meaning South Gate).

盧生說始皇曰:臣等求芝奇藥仙者常弗遇,類物有害之者。方中,人主時爲微行以辟惡鬼,惡鬼辟,真人至。人主所居而人臣知之,則害於神。真人者,入水不濡,入火不爇,陵雲氣,與天地久長。今上治天下,未能恬倓。願上所居宮毋令人知,然后不死之藥殆可得也。於是始皇曰:吾慕真人,自謂真人,不稱朕。乃令咸陽之旁二百里內宮觀二百七十復道甬道相連,帷帳鍾鼓美人充之,各案署不移徙。行所幸,有言其處者,罪死。

Scholar Lu advised the First Emperor [to conceal his whereabouts]: “This vassal and others who look for magic mushroom and elixirs of long life and immortals regularly failed to find them. It seems that there were things impeding the effort. There is one method among many [to remedy this]. If a ruler from time to time disguises himself as a commoner and walks around to exorcise evil demons, then the evil demons will be expelled and the Perfected will come. If the place a Lord stays is known to his vassals, then it impedes the spirit. The Perfected can walk on water without getting wet, through fire without getting burned. They ride on the misty clouds and endure as long as the heavens and the earth. Now the way Your Highness is ruling the world, you will not be able to remain undisturbed. I hope that Your Highness will not let anyone know of a residence wherein you stay; then the elixir of long life may be obtained.” Thus the First Emperor said: “I long to meet the Perfected. I will call myself the Perfected, no more chen 朕 when referring to myself!” He then ordered that all the 277 palaces and towers within the 200 li surrounding Xianyang be connected by elevated walkways and walled corridors. Curtains, bells and drums, and beautiful girls filled the palaces; each was registered and assigned to a place and never transferred. Wherever he went, those who spoke of his whereabouts were sentenced to death.

平等寺,廣平武穆王懷捨宅所立也。在青陽門外二里御道北,所謂孝敬里也。堂宇宏美,林木蕭森,平臺複道,獨顯當世。

The Pingdeng Monastery was established at the former residence of Yuan Huai, the Lord Wumu of Guangping. It was on the north side of the Imperial Drive, two li outside the Qingyang Gate, and within the so-called Ward Xiaojing. The halls and rooms were vast and beautiful, sheltered by stately trees that presented a solemn atmosphere. Its raised foundation and covered passageway (elevated walkways) were outstanding structures of the time.

3. Reformation of Buddhism

Emperor Wu of Liang created a new idea or policy of “Emperor-Bodhisattva,” which carries both political and religious significance. As an idea, it consists of the Chinese kingship “emperor” and the Indian ideal kingship of “cakravartin轉輪聖王.” This kingship of Emperor Wu is a fusion of the Chinese ideal kingship of the sagely king and the Indian ideal kingship of “cakravartin”. It can be understood as a syncretism of three teachings in one, i.e., a combination of Confucianism, Buddhism and Daoism; or a politico-religious policy, or even a policy in which he ruled his state with the image of “Emperor-Bodhisattva”, hoping to establish a Buddhist empire, or to unite the North and the South after a long period of disunion.

The practice of self-fashioning into the image of Buddharāja Maitreya彌勒佛王 did not begin with Emperor Wu himself. The Buddhist beliefs of the Liang were basically inherited from the Song (420–479) and Qi (479–502) dynasties that preceded it.

3.1. Northern Wei Context of Politico-Religious Reformation

初,法果每言,太祖明叡好道,即是當今如來,沙門宜應盡禮,遂常致拜。謂人曰:能弘道者人主也,我非拜天子,乃是禮佛耳。

Back then, Faguo always delivered such a talk that the Great Ancestral Emperor (Tuoba Gui) was wise and fond of the Way and he was the Tathāgata of today, therefore the monks should worship and respect him. So he always kneels to him. He tells other people that the man who can propagate the Way is the Master of people, and he is not worshipping the Son of Heaven, but the Buddha.

太宗踐位,遵太祖之葉,亦好黃老,又崇佛法,京邑四方,建立圖像,仍令沙門敷導民俗。

The Great Emperor (Tuoba Si 拓跋嗣) ascended the throne, and followed the examples of the Great Ancestral Emperor. He also liked doctrines of Emperor Huang and Laozi, and admired Buddhist teachings. In the four directions of the capital city, he ordered the establishment of portraits and statues of Buddha, and ordered the monks to instruct the local residents of proper customs.

至我正光中,造明堂於壁雍之西南,上圓下方,八牎四闥。汝南王復造磚浮圖於靈臺之上。

During the Zhengguang period (520–524 CE) of our dynasty, the Hall of Illumination was built to the southwest of the Piyong Hall (Imperial Academy). It had a round top on a square base, with eight windows and four gates. The Prince of Runan added a brick stūpa atop the Imperial Observatory.

3.2. Ancestral Memory in Sacred Space

(太極殿)中有丈八金像一軀,中長金像十軀,繡珠像三軀,金織成像五軀,玉像二軀。作工奇巧,冠於當世。

In the Palace [of the Great Ultimate] was a golden statue of the Buddha one zhang and eight chi high, along with ten medium-sized images—three of sewn pearls, five of woven golden threads, and two of jade. The superb artistry was matchless, unparalleled in its day.

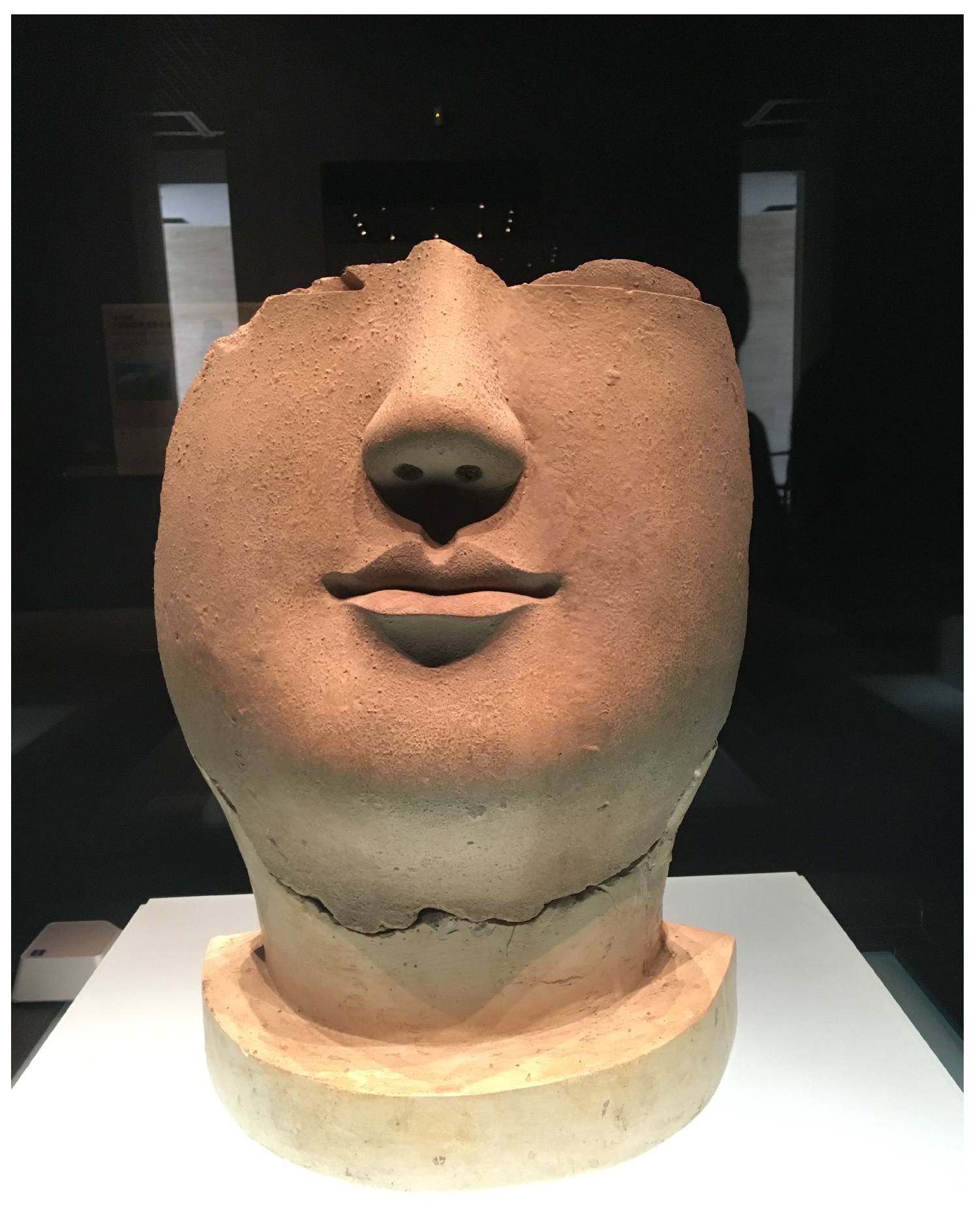

詔有司為石像,令如帝身。既成,顏上足下,各有黑石,冥同帝體上下黑子。論者以為純誠所感。

[Wencheng Emperor] ordered the administrative officers to engrave a stone statue in the emperor’s image. Once it was finished, on the face and foot, each had a black stone, just subtly looked like the Emperor’s moles up and down. Those who talked about it thought it is the resonance due to piousness.

興光元年秋,敕有司於五級大寺內,為太祖以下五帝,鑄釋迦立像五,各長一丈六尺,都用赤金二十五萬斤。

In the fall of the first year of the Xingguang Reign (454 CE), Emperor ordered the administrative officers to build five standing statues of Sakyamuni for five emperors, starting from the Great Ancestral Emperor, in a grand five-storied temple. Each of the statues was one zhang and six chi, costing 250,000 jin of gold.

According to the Ritual records, a Zhou dynasty king visiting his family shrine would initially pass between the tablets of his father and grandfather and then between the tablets of his great-grandfather and great-great-grandfather. These would be arranged with the even-numbered generations or zhao 昭 to the visitor’s right and odd-numbered generations or mu 穆 to his left. After passing his four most recent forebears in their zhaomu positions, he then came to two collective altars where all the older zhao- and mu-tablets sat in order led by the Zhou dynastic founders, King Wen and Wu. Finally, he passed beyond his own dynastic history to confront the clan altar, that of the legendary Hou Ji 后稷.

東有秦太上公二寺,在景明寺南一里。西寺,太后所立,東寺,皇姨所建。並為父追福,因以名之。

報德寺,高祖孝文皇帝所立也,為馮太后追福,在開陽門外三里。

To the east, one li south of the Jingming Monastery, there were two temples in honor of Father Qin of the Supreme Empress. The one on the west was established by the empress dowager, whereas the one on the east was founded by her younger sister. Both were dedicated to the posthumous happiness of their father and so were they named.

The Baode Temple was established by Emperor Xiaowen, [otherwise known as] Gaozu, and dedicated to his grandmother Empress Feng for her posthumous happiness. It was located three li outside the Kaiyang Gate.

永寧寺,熙平元年靈太后胡氏所立也。

The Yongning Temple was constructed in the first year of the Xiping reign, (516 CE) by decree of Empress Dowager Ling (?–528 CE)), whose surname was Hu.

3.3. Buddhism in Public Space

四時祭祀,周孔所教,欲人勿死其親,不忘孝道也。求諸內典,則無益焉。殺生為之,翻增罪累。若報罔極之德,霜露之悲,有時齋供,及七月半盂蘭盆,望於汝也。

Offering sacrifices in each of the four seasons is the teaching of Zhougong and Kongzi. They want people not to forget their deceased parents and not to forget the filial piety. Continually referring to Daoist texts does not make any good. If you kill lives for sacrifice, you add to your evil. If you want to repay my ultimate kindness, and to relieve your sorrow in misty and dewy days, you can just sacrifice to me occasionally. And once it is the Buddhist Ghost Festival in the mid of seventh month, you could remember to offer sacrifices to me.

四月七日京師諸像皆來此寺。尚書祠部曹錄影凡有一千餘軀,至八日節,以次入宣陽門,向閶闔宮前,受皇帝散華。於時金華映日,寶蓋浮雲,旛幢若林,香煙似霧,梵樂法音,聒動天地;百戲騰驤,所在駢比;名僧德眾,負錫為群,信徒法侶,持花成藪;車騎填咽,繁衍相傾。時有西域胡沙門見此,唱言佛國。

On the seventh day of the fourth month all images in the capital were assembled in this monastery, numbering more than one thousand, according to the records of the Office of Sacrifices, Department of State Affairs. On the eighth day, the images were carried one by one into the Xuanyang Gate, where the emperor would scatter flowers in front of the Changhe Palace. At this moment, gold-colored flowers reflected the dazzling sunlight, and the bejeweled canopies for the images floated in the clouds. Banners were as numerous as trees in a forest, and incense smoke was as thick as a fog. Indian music and the din of chanted Buddhist scriptures moved heaven and earth alike. Wherever variety shows were performed, there was congestion. Renowned monks and virtuous masters, each carrying a staff, formed a throng. The Buddhist devotees and their companions holding flowers resembled a garden in bloom. Carriages and horses choked and jostled each other. A foreign monk from the Western Regions saw it, and chanted and said it was just the Buddha’s land.

有像一軀。舉高三丈八尺。端嚴殊特。相好畢備。士庶瞻仰。目不暫瞬。此像一出市井。皆空炎先。騰輝赫赫。獨絕世表。

In the Zongsheng Temple was a Buddha image that was three zhang and eight chi. Its countenance was unusually grave, and it had all [the thirty-two marks and eighty signs on the body]. People held the statue in high esteem and could not take their eyes of it. Whenever the statue was on parade, [they would leave their homes or the marketplace to see it, so that] all the homes and marketplaces were virtually empty. The aureole of this statue had no parallel in its time.

(景樂寺)有佛殿一所,像輦在焉,雕刻巧妙,冠絕一時。堂廡周環,曲房連接,輕條拂戶,花蕊被庭。至於大齋,常設女樂。歌聲繞樑,舞袖徐轉,絲管寥亮,諧妙入神。

(元悅)召諸音樂,逞伎寺內。奇禽怪獸,舞抃殿庭,飛空幻惑,世所未睹。異端奇術,總萃其中。剝驢投井, 植棗種瓜,須臾之間皆得食。士女觀者,目亂睛迷。

[In Jingyue Nunnery] there was a Hall of Buddha that housed a carriage for the sacred image. The deftness shown in carving had no parallel at the time. Halls and corridors encircled each other, while inner rooms followed one after another. Soft branches brushed the windows; blooming flowers covered the courtyard. At the time of Great Fast posadha, music performed by female artists was often provided: the sound of singing enveloped the beams, while dancers’ sleeves slowly whirled in enchanting harmony with the reverberating notes of stringed and pipe instruments. It was rhythmical and breathtaking.

(Yuan Yue) summoned a number of musicians to demonstrate their skills inside the nunnery. Strange birds and outlandish animals danced in the courtyards and flew into the sky, and changed into bewildering shapes. They presented a show never seen before in the world. Unusual games and spectacular skills were all performed here. Some magicians would dismember an ass and throw the cut-up parts into a well, only to have the mutilated animal quickly regenerate its maimed parts. Others would plant date trees and melon seeds that would in no time bear edible fruits. Women and men who watched the performance were dumbfounded.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brashier, Kenneth E. 2011. Ancestral Memory in Early China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jenner, William. 1981. Memories of Loyang. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, Kathy Cheng-Mei. 2010. The Buddharāja Image of Emperor Wu of Liang. In Philosophy and Religion in Early Medieval China. Edited by Alan Chan and Yuet Keung Lo. Albany: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Liang 李亮. 2022. Beichao suiting ducheng kongjian quhua zhidu de yanbian:yi fang li de shiyong wei zhongxin 北朝隋唐都城空间区划制度的演变——以坊里的使用为中心 (The evolution of the sytem of space division in capitals from the Northern Dynasties to the Sui and Tang Dynasties: Based on the Fang and Li). Zhongguo lishi dili luncong 中国历史地理论丛 37: 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhijun 李智君. 2020. Beiwei fojiao dui luoyang ducheng jingguan de shikong kongzhi: Yi jingguan gaodu yanti he shijian jielü bianhua weili 北魏佛教对洛阳都城景观的时空控制——以景观高度演替和时间节律变化为例 (Buddhist Manipulation of Luoyan’s Spatial and Temporal Landscape in the Northern Wei Dynasty). Xueshu yuekan 学术月刊 52: 155–70. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, Ichisada 宮崎市定. 1960. Chūgoku niokeru sonsē no sēritsu: Kodai tēkoku hōkai no ichimen 中國における村制の成立: 古代帝國崩壞の一面 (On the Appearance of Villages in China: An Aspect of the Ruin of the Ancient Empire). Töyöshi kenkyū 東洋史研究 4: 569–90. [Google Scholar]

- Nienhauser, William H., Jr., ed. 1994. The Grand Scribe’s Records: The Basic Annals of Pre-Han China. vol. 1. By Ssu-ma Ch’ien. Tsai-fa Cheng, Zongli Lu, William H. Nienhauser, Jr., and Robert Reynolds, trans. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Guoxiang 錢國祥. 2006. Beiwei Luoyang de fojiao shiku yu yongning si zaoxiang北魏洛陽的佛教石窟與永寧寺造像(Buddhist grotoes in Northern Wei Luoyang and statues in Yongning Monastery). In 2004 nian longmen shiku guoji xueshu yantaohui wenji 2004年龍門石窟國際學術研討會文集 (Collected Papers of 2004 International Conference on Longmen Grotto). Edited by Zhengang Li 李振剛. Zhengzhou: Henan renmin chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Qian 司馬遷. 1959. Shi ji 史記 (Records of the Grand Historian). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yinggang 孙英刚. 2013. Zhuanlun wang yu Huangdi: Fojiao dui zhonggu junzhu gainian de yingxiang 转轮王与皇帝:佛教对中古君主概念的影响 (Cakravartin and Emperor: Buddhist Influence on Medieval Concept of Ruler). Shehui kexue zhanxian 社会科学战线 11: 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yinggang 孙英刚. 2017. Cong fulousha dao chang’an: Sui Tang jiandu sixiang zhong de yige fojiao yinsu 从富楼沙到长安:隋唐建都思想中的一个佛教因素 (From Purusapura to Chang’an: Buddhist Influence on Sui and Tang Capital Construction). Shehui kexue zhanxian 社会科学战线 12: 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Liqi 王利器. 1993. Yanshi jiaxun jijie 顏氏家訓集解 (Collected Commentaries on Yan Family Instructions). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Shou 魏收. 1974. Wei Shu 魏書 (Book of Wei). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Zixian 蕭子顯. 1972. Nan Qi Shu 南齊書 (Book of Southern Qi). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Shangwen 顏尚文. 1999. Liang wudi 梁武帝 (Emperor Wu of Liang). Taipei: Dongda tushu gongsi. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Xuanzhi 楊衒之. 1984. A Record of Buddhist Monasteries in Lo-yang. Translated by Yi-t’ung Wang. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Zumo 周祖謨. 2010. Luoyang qielan ji jiaoshi洛陽伽藍記校釋 (Commentaries on the Record of the Monasteries of Luoyang). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ling, C. Imperial Identity and Religious Reformation: The Buddhist Urban Landscape in Northern Wei Luoyang. Religions 2024, 15, 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050551

Ling C. Imperial Identity and Religious Reformation: The Buddhist Urban Landscape in Northern Wei Luoyang. Religions. 2024; 15(5):551. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050551

Chicago/Turabian StyleLing, Chao. 2024. "Imperial Identity and Religious Reformation: The Buddhist Urban Landscape in Northern Wei Luoyang" Religions 15, no. 5: 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050551

APA StyleLing, C. (2024). Imperial Identity and Religious Reformation: The Buddhist Urban Landscape in Northern Wei Luoyang. Religions, 15(5), 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050551