Abstract

In 2021, two small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes were unearthed from a tomb from the Eastern Han Dynasty in Chengren Village, Xianyang City, Shanxi Province. The excavation team believe that these statuettes are from the late Eastern Han Dynasty and represent the earliest independent gilt bronze Buddha statuettes ever discovered in China through archaeological excavations, a belief that has attracted widespread interest and debate among scholars worldwide. However, because the tomb had been looted in the past, the publication of these findings immediately sparked considerable debate, particularly over the dating of the statuettes. The main controversy revolves around two dating proposals: the “Late Eastern Han Dynasty” and the “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms”. This paper proposes a third viewpoint by examining previously overlooked aspects and materials regarding the statuettes and by placing them within the context of the Guanlong region’s tradition of small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes. We contend that the two statuettes were not created at the same time: we believe that the standing Buddha statuette dates from the end of the “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms”, whereas the flat five-Buddha statuette was likely crafted between the Yanxing 延興 era and the early Taihe 太和 era of Emperor Xiaowen 孝文帝 of the Northern Wei Dynasty. The styles, combinations of forms, and themes in these statuettes are not distinctive and are, in fact, typical of small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes from the late “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms” to the mid-Northern Wei Dynasty in the Guanlong region.

1. Introduction

In May 2021, archaeologists from the Shaanxi Academy Archaeology excavated two small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes from a family tomb from the Eastern Han Dynasty in Chengren Village, Hongdu Yuan, Xianyang City. The statuettes were excavated from M3015 and consist of a standing Buddha with the Abhaya Mudrā (Figure 1) and a flat five-seated Buddha statuette (Figure 2). Furthermore, a pottery jar inscribed with a date marking the first year of the Yanxi era of the Eastern Han Dynasty 延熹元年 (158 AD) was also discovered in the adjacent tomb, M3019, providing a solid foundation for dating the family tomb. The excavation team, through comprehensive research, concluded that these statuettes were the earliest gilt bronze Buddha statuettes ever discovered in China through archaeological means. They are believed to have been locally crafted in a style influenced by Gandhara. These statuettes are of great significance in studying the introduction of Buddhist culture to China and the Sinicization of Buddhism.1

Figure 1.

The standing Buddha statuette excavated from M3015 in Chengren Village, Xianyang (taken from Shaanxi 2022).

Figure 2.

The flat five-seated Buddha statuette excavated from M3015 in Chengren Village, Xianyang (taken from Shaanxi 2022).

The academic significance of these two Buddha statuettes is undeniable, and their unveiling promptly drew widespread attention and sparked intense debate within the international academic community.2 An overview of the excavation of the family tomb from the Eastern Han Dynasty, along with the preliminary research and scientific analysis3 of the statuettes, was swiftly published (Shaanxi 2022, pp. 3–27; Ran et al. 2022, pp. 82–94; Li et al. 2022, pp. 123–28). However, following this publication, the fact that M3015 had been looted in the past led to a considerable rift in the interpretation of these Buddha statuettes. The main controversy revolves around two dating proposals: the “Late Eastern Han Dynasty” and the “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms”. Despite the ongoing sharing of new research, these disagreements seem to have not only persisted, but intensified. The core issues pertaining to these gilt bronze Buddha statuettes are yet to be resolved and represent an open academic question, the discourse around which continues to be a topic of great interest. This paper proposes a third viewpoint by examining previously overlooked aspects and materials regarding the statuettes and by placing them within the context of the Guanlong region’s tradition of small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes.

2. Current Research Status and Existing Issues

The research on these two Buddha statuettes is quite extensive, covering a wide range of topics, such as their dating, origin, manufacturing techniques, features, artistic style, cultural provenance, function, community of believers, and relation to different forms of belief. Scholars such as Ran Wanli 冉萬里 and Li Ming 李明, who were among the first to conduct specialized research on these statuettes, have offered in-depth analyses from nine distinct perspectives (Ran et al. 2022, pp. 82–94). Among all the issues discussed, the most fundamental is the dating of the Buddha statuettes, which lies at the heart of the debate surrounding them. Currently, two main viewpoints dominate the discourse: the “Late Eastern Han Dynasty” and the “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms”.

The dating of the Buddha statuettes is highly significant, as it represents a cornerstone for addressing most other pertinent issues. In essence, if the chronological framework on which the research is based is fundamentally flawed or disproven, then the discussion of other related topics loses its significance. For instance, it is only relevant to investigate whether these Buddha statuettes were “independently consecrated” or “manufactured locally in China” if they can be confidently dated to the late Eastern Han Period. Similarly, re-examinations of “the route of Buddhism’s introduction to China”, “the developmental sequence of early gilt bronze Buddha statuettes in China”, and “the community of believers during the Eastern Han Dynasty” all hinge on the accurate dating of these statuettes. Therefore, establishing the date of the Buddha statuettes represents a critical issue and the primary question that must be resolved in the related research on this topic.

Regarding the debate over the dating of the Buddha statuettes, Ran Wanli and the excavation team were the first to propose the theory of the “Late Eastern Han Dynasty” (Shaanxi 2022, p. 27; Ran et al. 2022, pp. 82–94). This view has been supported by subsequent publications from scholars like Lothar von Falkenhausen, Li Min 李旻, Robert L. Brown, Huang Chunhe 黃春和, and Cui Mengze 崔夢澤, each offering varying levels of detail and nuanced perspectives in their discussions. For example, Lothar von Falkenhausen believes that “the previous art historical sequence may have been founded on a misinterpretation of styles.” (Lei 2022a). Huang Chunhe suggests that “the religious significance and value of these two Buddha statuettes are similar to the numerous statuettes found in tombs in southwestern China at that time, serving merely as general deities for sacrifices rather than independent representations of religious belief.” (Huang 2022, pp. 47–56). Cui Mengze’s latest research article does not discuss the dating controversy, but instead directly builds its argument on the assumption of the “Late Eastern Han Dynasty” theory (Cui 2024, pp. 73–76). Given the significant disagreements surrounding the dating of these statuettes, Cui’s research is fraught with risk and could potentially be entirely invalidated.

Immediately after the “Late Eastern Han Dynasty” theory was proposed, scholars introduced the “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms” theory. Yang Xin 陽新 was the first to publish an article elaborating on this new perspective (Yang 2021). Other representative scholars, including Yao Chongxin 姚崇新, Zhu Hu 朱滸, Li Wenwen 李雯雯, and He Zhiguo 何志國, have also published articles in agreement with this view. Both Yang Xin and Yao Chongxin both believe that the two Buddha statuettes were likely mixed into the tomb during later tomb-raiding activities. Yao Chongxin also performed a specific analysis of the nature of these two statuettes and the reasons for their entry into the tomb, suggesting that they might be portable miniature Buddha statuettes that were accidentally left behind by tomb raiders, serving as amulets. He also contends that even if the statuettes date to the “Late Eastern Han Dynasty”, they are not the earliest independent Buddha statuettes nor the earliest gilt bronze Buddha statuettes in China, a conclusion based on his analysis of the “Futu Jian” “浮屠簡” of the Eastern Han Period found at Xuanquanzhi 懸泉置 and other existing works from the Chinese literature (Yao 2022, pp. 17–29). Li Wenwen and Zhu Hu focused on the stylistic aspects of the statuettes and have identified the standing statuette as exhibiting a fusion of three distinct styles: the Gandhara style of the Kushan Period, the Mathura style of the Kushan Period, and the Mathura style of the Gupta Period. They challenge the idea that the statuettes were forgotten by looters and propose instead that they entered the tomb through secondary or multiple burials (Li and Zhu 2022, pp. 184–91). He Zhiguo conducted a more detailed analysis and comparative study of the statuettes’ characteristics. He remained circumspect about the exact reasons for the statuettes being mixed into the tomb, without providing a definitive conclusion (He 2023, pp. 122–31).

Researchers who support the “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms” theory have presented two key pieces of evidence. Firstly, they all reference a 1950s precedent involving the discovery of two small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes amidst scattered bricks in a looted Eastern Han tomb in BeiSong Village, Shijiazhuang City 石家莊北宋村 (Sun et al. 1959, p. 55). Secondly, in their comparative studies of the characteristics and artistic styles of the Buddha statuettes, they all highlight a bronze standing Buddha statuette in a private collection in Japan (Rhie 2002, pp. 424–25, fig. 2.67) that is similar to the standing Buddha statuette excavated from M3015. Previous research has dated all three statuettes to the Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms. However, proponents of the “Late Eastern Han Dynasty” theory find these pieces of evidence to be flawed. As Lothar von Falkenhausen notes, there has been a bias in the dating and classification of these small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes and that they should be re-examined (Lei 2022a). The discovery of the gilt bronze Buddha statuettes in Chengren village actually serves to correct the previous conclusions. Objectively, these two arguments are inadequate, particularly that regarding the bronze standing Buddha statuette in the Japanese private collection. It is an isolated case outside of Chengren, its current whereabouts are unknown, and the specifics of its excavation and provenance are unclear. The research on this statuette is still pending, and its use as evidence has significant limitations.

In terms of the methodology, researchers advocating for both the “Late Eastern Han Dynasty” and “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms” theories have largely employed the same three primary research methods, without much distinction. The first method focuses on establishing the relative chronological relationship between the Buddha statuettes and the tombs, i.e., whether the Buddha statuettes were original funerary objects or were introduced into the tombs at a later date. Given that M3015 was once looted, determining the chronological relationship between the statuettes and the tombs largely relies on logical reasoning. However, researchers on both sides of the debate have struggled to present a logic that can fully convince those with the opposing viewpoint. Even among scholars who support the “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms” theory, there are numerous different ideas about the specific ways in which the Buddha statuettes may have entered the tombs. History is often filled with contingencies and uncertainties, and it is difficult to reach the historical truth based solely on logical reasoning without substantial evidence. We believe that it is unnecessary to dwell excessively on this problem, as it leads to the risk of falling into fruitless debates in which each side simply repeats their own arguments. The resolution of this issue is not essential in fundamentally determining the creation dates of the Buddha statuettes.

The second method involves comparative studies of the form, artistic style, and subject composition of the Buddha statuettes to determine their creation date. Researchers generally agree on the selection of comparative objects, primarily focusing on stone Buddhist sculptures from the Kushan Empire with Gandhara and Mathura styles, Buddha statuettes unearthed from tombs in the Southwest and Jiangnan regions of China from the Eastern Han to Western Jin Periods, and small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes from Northern China up until the “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms”. However, due to the subjectivity of the researchers and variations in their starting premises, there are considerable variations in the analysis of the statuettes’ features and the selection of comparative focuses. This leads to an interesting phenomenon whereby different conclusions are drawn from the same materials, using the same research methodologies. This is largely attributable to the scope and effectiveness of these research methods. Within certain limits, comparative research of cultural factors undoubtedly represents an effective research method. However, when the comparative objects span a broad temporal and spatial range, with significant differences in their material, size, function, and user group, comparative research often allows for considerable subjective interpretation and can lack persuasiveness. For example, there is currently a comparative study of the two Buddha statuettes with Gandhara and Mathura statuettes. Such a wide-ranging cross-temporal and -spatial comparison can, at most, demonstrate the possible presence of individual Buddhist sculptures in China during the late Eastern Han Dynasty, but it fails to explain the specific creation dates of these two gilt bronze Buddha statuettes. Therefore, in comparative research, the selection of comparative objects is crucial. Generally speaking, the closer the temporal and spatial scope of the comparative objects, and the more similar their material, size, and function, the more reliable the conclusions are likely to be.

The third method involves utilizing natural sciences for the examination and analysis of the two Buddha statuettes. Due to the differences between metal and organic materials, scientific testing may provide insights into the manufacturing techniques used for these statuettes, and their origins. However, it is less effective in directly determining the exact dates of the Buddha statuettes.

It should be noted that previous researchers have overlooked two critical chronological issues. First, the creation date of a Buddha statuette must precede the date that it was placed in the tomb. Scholars have already demonstrated through the statuettes’ wear and tear that they were used for a long time (Yao 2022, p. 18). Therefore, if the statuettes were not placed into the tomb at a later time, then the tomb’s date can only be considered as the lower limit for the statuettes’ dates; the duration of their use before entering the tomb remains unknown. If the statuettes were indeed placed into the tomb at a later date, then even if their creation date, as speculated by scholars, falls within the “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms”, that date can only be considered as the upper limit for the statuette’s entry into the tomb. It may not necessarily correspond to the period during which scholars previously assumed that the statuettes were left in the tomb (Yao 2022, p. 29).

Secondly, it is necessary to consider whether the two Buddha statuettes share the same creation date. After all, although they were unearthed from the same site, they are distinct entities. The current research, whether intentionally or inadvertently, tends to assume that they are contemporaneous relics. However, there are significant differences between them in terms of their subject matter, sculptural features, artistic style, and alloy composition. Could these differences signify that they are from different periods? After all, it is very common in archaeological discoveries to find objects of different ages in the same tomb or Buddha statuette hoard. According to the fundamental principles of archaeological chronology, the later-dated statuette should be considered as the upper limit for when both statuettes entered the tomb. In summary, the two gilt bronze Buddha statuettes from the Eastern Han Dynasty tomb at Chengren Village should not be treated as a single entity, but must instead be considered individually.

3. The Dating of the Standing Buddha Statuette and Related Issues

Of the two Buddha statuettes unearthed in M3015 in Chengren Village, the standing Buddha statuette is notably better preserved, with its sculptural features being relatively clear and thus leading to more attention and discussion among researchers. As previously noted, extensive comparative studies have been conducted on this statuette by scholars. However, due to varying perspectives and the inherent limitations of the comparative objects, the conclusions have been quite divergent. Given the current state of research, it seems unlikely that further substantial breakthroughs in dating the statuette based on its facial features, robes, and posture will be made. Fortunately, we have discovered that the lotus petals on the lotus pedestal of the standing Buddha statuette are quite distinctive and can provide an important breakthrough for determining the date of the statuette.

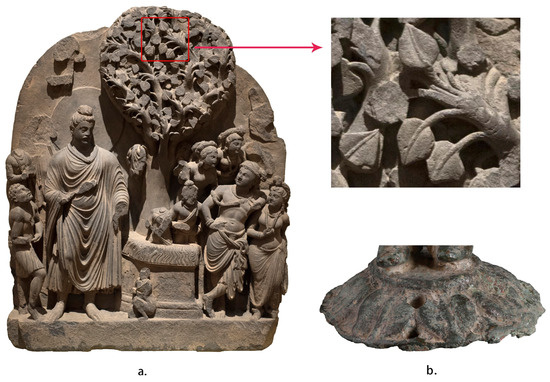

The characteristics of the lotus petals on the pedestal of the standing Buddha statuette unearthed in Chengren Village are as follows: the petals are thick, with a raised longitudinal vein in the center; the widest part can be found slightly towards the back of the middle, narrowing in an arc shape towards the tip, with a concave indentation in the middle at the tip and a protrusion in the front center, and the length of the petals slightly exceeds their width (Figure 3b). Previous researchers, after comparative studies, have consistently concluded that these petals share similarities with the lotus petal patterns on the halo and umbrella cover of the gilt bronze Buddha statuette unearthed in Yudu Township, Jingchuan 涇川玉都鄉 (Yang 2021). In fact, these are two completely different lotus petal patterns. The widest part of the lotus petals on the Buddha statuette from the Yudu Township Buddha statuette is not at the back but at the front, and from there, they taper straight back; the length of the petals is much greater than the width, leading to an elongated appearance overall (Figure 3a). Apart from the central raised longitudinal vein, all other aspects of these petals differ significantly from those of the petals on the standing Buddha statuette’s pedestal in Chengren Village.

Figure 3.

Comparative illustration of the lotus petal patterns on the lotus pedestal of the standing Buddha statuette from Chengren Village and the Buddha statuette from Yudu Township, Jingchuan ((a). the Buddha statuette from Yudu Township, provided by Jingchuan County Museum; (b). the lotus pedestal of the standing Buddha statuette from Chengren Village. Graphic created by the author).

The shape of the lotus petals on the standing Buddha statuette from Chengren Village is very consistent with the Bodhi leaves prevalent in Gandharan Buddhist art (Figure 4). In Gandharan Buddhist art, this shape of Bodhi leaf is not only frequently carved as an edge decoration on the stone slabs of stupas and temple steps, but is also extensively used as decoration within specific scenes of the Buddha’s life stories. For example, it is widely depicted in images such as the Buddha’s asceticism, the subjugation of demons to achieve enlightenment, the offering of the bowl by the Four Heavenly Kings, Brahma’s invitation, and the approach to the Bodhi throne4 (Figure 4a). The related iconography is extremely rich and is too extensive to list in full.

Figure 4.

Comparative illustration of the lotus petals on the lotus pedestal of the standing Buddha from Chengren Village and Bodhi leaves in Gandhara style ((a). a sculpture showing “the Approach to the Bodhi throne”, collected in the Cleveland Museum of Art, USA, with the image sourced from the official website exhibition; (b). the lotus pedestal of the standing Buddha statuette from Chengren Village. Graphic created by the author).

In China, it is not unusual to find lotus petals styled as Bodhi leaves on small gilt bronze Buddha figures. The Palace Museum houses a small gilt bronze standing statuette of Maitreya Bodhisattva with a lotus throne, with a total height of 9.9 cm. This statuette was purchased in Xi’an in the early 1960s and is cataloged as image No. 21 in Chinese Gilt Bronze Buddha Statues 《中國金銅佛》 (Li 1995, pp. 40, 229) (Figure 5a). The lotus petals on the throne of this statuette also take the form of Bodhi leaves, almost identical to those on the lotus throne of the standing Buddha from Chengren Village (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparative illustration of the lotus pedestal of the standing Buddha from Chengren Village and Statuette No. 21 in the Palace Museum ((a). Statuette No. 21 in the Palace Museum, taken from Li 1995, p. 40; (b). the lotus pedestal of the standing Buddha statuette from Chengren Village. Graphic created by the author).

In addition, the same Bodhi leaf-shaped petals are cast in the center of the double-lion pedestal of the famous gilt bronze Buddha statuette from the second year of the Shengguang era of Daxia 大夏勝光二年 (429 AD) (Figure 6). The second year of the Shengguang era saw the reign of Helian Ding 赫連定, the king of Daxia 大夏. At that time, Tongwan City 統萬城 had fallen, and Helian Ding fled to Pingliang 平凉 (Huang 2015, p. 6). Shi Wen 施文, the devotee of the statuette, held the position of “Zhongshu Sheren” 中書舍人, a close minister who accompanied the monarch. The creation site of the statuette is expected to be in Pingliang (Huang 2015, p. 6), part of the Longdong region 隴東地區, which is close to the location of the two statuettes mentioned above, all of which belong to the Guanlong cultural sphere.

Figure 6.

Comparative illustration of the lotus pedestal of the standing Buddha from Chengren Village and the Buddha statuette from the second year of the Shengguang era ((a). the Buddha statuette from the second year of the Shengguang era, taken from Luo 2010, p. 40; (b). the lotus pedestal of the standing Buddha statuette from Chengren Village. Graphic created by the author).

The same Bodhi leaf-shaped lotus petals also appear in numerous early small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes found outside the Guanlong region in China, such as those excavated in Xiguancheng, Yi County, and Hebei 河北易縣西貫城 (Figure 7a), as well as those collected in the Zhengzhou Museum 鄭州博物館 (Figure 7b), the National Palace Museum, Taipei (Figure 7c), the Nelson Atkins Museum in the United States (Figure 7d), and the Idemitsu Museum of Arts in Japan. Each of these statuettes also cast the same Bodhi leaf-shaped lotus petal at the center of the double-lion pedestal. Moreover, these Buddha statuettes are highly consistent in terms of posture, robe style, clothing patterns, sleeve flares, tenons, and the form of the two lions, indicating that they belong to the same phase of the evolutionary sequence of early small meditative gilt bronze Buddha statuettes in China (Zhang 2024, pp. 49–58). Taking the second year of the Shengguang era of Daxia as a chronological reference, it becomes evident that this Bodhi leaf-shaped lotus petal pattern was a common and popular design on small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes in the late Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms across the Guanlong region and even the entirety of northern China.

Figure 7.

Small meditative gilt bronze Buddha statuettes with Bodhi leaf-shaped lotus petals cast at the center of the double-lion seat ((a). excavated in Xiguancheng, Yi County, with image taken from Zhejiang 2018; (b). in the Zhengzhou Museum, with image taken from Zhejiang 2018; (c). in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, with image taken from Chen 1996; (d). in the Nelson Atkins Museum, with image taken from Jin 1994).

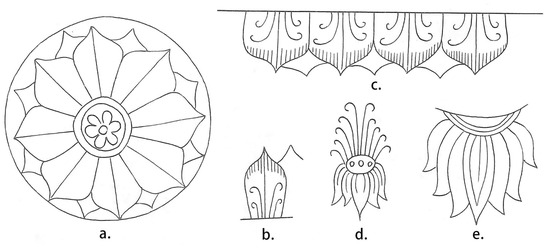

To the best of our knowledge, the Bodhi leaf-shaped lotus petal pattern has not appeared systematically on other Chinese Buddhist statuettes beyond the early small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes. Within the evolutionary sequence of early small meditative gilt bronze Buddha statuettes in China, the lotus petal pattern, as an important component, also exhibits strong characteristics of distinct stages. A Buddha statuette dated to the fifth year of the Taichang era 泰常五年 (420 AD), excavated in Sidaoying, Longhua County 隆化四道營, is another benchmark piece with an inscribed date in the evolutionary timeline of these statuettes (Figure 8). Buddha statuettes belonging to the same stage as this one include statuette No. 2 unearthed in Beisong Village, Shijiazhuang, a selected statuette from the Baoding Native Products Management Department 保定土產經理部, Statuette No. 4 in the collection of the Palace Museum, and a statuette unearthed in Yudu, Jingchuan County (Liu 2002, pp. 377–82, 385–87). The prevalent lotus petal patterns from this stage are highly uniform in shape and represent an earlier phase than the Bodhi leaf-shaped lotus petal pattern. Taking the well-preserved statuettes from Yudu and from Beisong Village, Shijiazhuang (Statuette No. 2) (Figure 9) as examples, it can be seen that lotus petal patterns are extensively cast on the halo, umbrella cover, and pedestal, as well as the pedestals of miniature meditative seated Buddha or Bodhisattva statuettes attached to the halo. The lotus pedestal of the small Buddha statuette on top of the Buddha statuette selected from the Baoding Native Products Management Department also features petals of the same shape (Figure 10).

Figure 8.

The Buddha Statuette with an inscribed date of the 5th year of the Taichang era (taken from Zhejiang 2018).

Figure 9.

Illustration of the petal pattern on Buddha statuette No. 2 unearthed in Beisong Village, Shijiazhuang ((a). Lotus petal on the canopy; (b). Lotus petals on the backdrop; (c). Lotus petals above the disciple statuette; (d). Lotus petals located at the center of the Double Lion Throne. (e). Lotus petals on the front of the Buddha’s pedestal. All taken from Liu 2002).

Figure 10.

The Buddha Statuette Selected from Baoding Native Products Management Department (taken from Zhejiang 2018).

The small meditative gilt bronze Buddha statuette in the collection of the Idemitsu Museum of Arts in Japan is a remarkable artifact that captures the evolutionary transition of lotus petal patterns. This statuette displays lotus petals in two distinct styles: Those at the center of the Buddha’s double-lion pedestal and on the inverted lotus seats within the halo are shaped like Bodhi leaves, indicative of a later stage (Figure 11). Conversely, the lotus petals on the inverted lotus seats of the standing Bodhisattva figures flanking the pedestal reflect an earlier form. Similarly, the lotus petal pattern at the center of the double-lion seat of the Yudu statuette also shows a clear transitional state, blending casting and carving techniques. It maintains the elongated petal pattern style seen in Statuette No. 2 from Beisong Village, Shijiazhuang, from the earlier stage (Figure 9e), while also beginning to adopt the basic form of the Bodhi leaf-shaped lotus petals of the next stage, though the outline remains relatively slender (Figure 12). In the absence of inscribed dates on these statuettes, we can use the slightly earlier Buddha statuette date to identify the fifth year of the Taichang era (420 AD) (Liu 2002, p. 386) as the upper limit for determining the appearance of the Bodhi leaf-shaped lotus petal pattern in the small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes.

Figure 11.

The Buddha Statuette in the collection of the Idemitsu Museum of Arts in Japan (taken from Jin 2002).

Figure 12.

Schematic illustration of the evolution of the lotus petal pattern at the center of the double-lion pedestal ((a). Buddha Statuette No. 2 from Beisong Village; (b). the Buddha statuette from Yudu Township; (c). a Buddha Statuette from the second year of the Shengguang era. Schematic created by the author).

Finally, we will discuss the lower limit for the time of the popularization of the use of Bodhi leaf-shaped lotus petal patterns on small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes in northern China. In 439 AD, the Northern Wei Dynasty unified northern China, bringing about a significant transformation regarding the development of Buddhism in northern China. According to the record of Wei Shu Shi Lao Zhi 《魏書·釋老志》, during the Taiyan era of the Northern Wei Dynasty, the Liangzhou region was conquered and its inhabitants were relocated to the capital. The Samanas followed them eastward, bringing Buddhist beliefs, which led to the further development of Buddhism in the capital. “太延中,涼州平,徙其國人於京邑,沙門佛事皆俱東,象教彌增矣” (Wei 1974, p. 3032). Correspondingly, significant changes also occurred in Buddhist art.

The popularity of early small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes, once centered in the Hebei Province, has waned over time. The existing Buddha statuettes from the early Northern Wei Dynasty, specifically during the Taiping Zhenjun era 太平真君年間, show numerous innovative developments (Liu 2002, pp. 383–84). Among the most notable changes are the lotus petal patterns on Buddhist statuettes, which are distinct from the Bodhi leaf-shaped lotus petal design that was extremely popular around 429 AD. The most distinctive feature of the new lotus petal patterns is the division of each petal into two sections, with a kidney-shaped protrusion at the middle of each part. For example, the lotus petals on the pedestals of the Buddha statuettes devoted by Zhu Xiong 朱雄 in the first year of the Taiping Zhenjun era (440 AD), the Buddha statuette devoted by Wanshen 菀申 in the fourth year of the Taiping Zhenjun era (443 AD) (Figure 13), and the Buddha statuette devoted by Zhuyewei 朱業微 in the fifth year of the Taiping Zhenjun era (444 AD) all exhibit this new style. Moreover, this style persisted in popularity until the fall of the Northern Wei Dynasty and became the primary lotus petal motif on Buddhist statuettes in northern China. In contrast, the Bodhi leaf-shaped lotus petals that enjoyed a brief time in vogue during the late “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms” did not reappear. Therefore, the year 439 AD marks an important milestone in Chinese Buddhist history and art and could be considered as the lower limit for the time of the popularization of the Bodhi leaf-shaped lotus petal patterns on small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes in northern China. In summary, I believe that the standing Buddha statuette unearthed in Chengren Village would have been created in the late period of the Sixteen Kingdoms, around the early 5th century.

Figure 13.

The Buddha statuette devoted by Wanshen in the fourth year of the Taiping Zhenjun era (taken from Jin 2002).

4. The Dating of the Flat Five-Seated Buddha Statuette and Related Issues

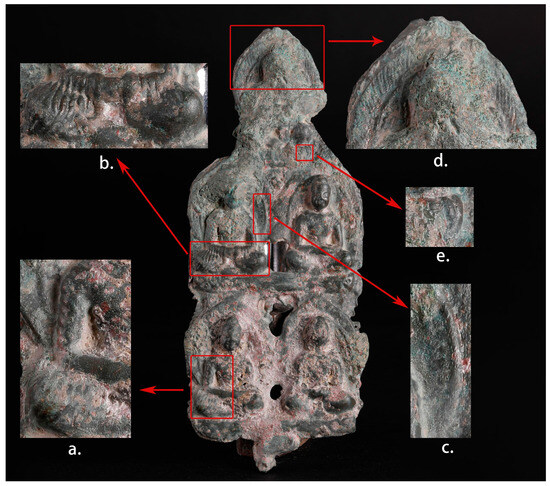

Each Buddha on the flat five-Buddha statuette has suffered varying degrees of damage, but it is possible to approximate the complete appearance of the Buddha images by piecing together the clear remaining parts of the figure. The Buddha statuette features a long, round face and is seated with a dhyana mudra in front of a peach-tip-shaped halo. The folds on the right arm of the lower-right Buddha statuette are obvious, indicating that it is adorned with a full-shoulder-style kasaya (Figure 14a). The sleeve cuff of the Buddha statuette in the second row on the right remains intact, and the pleats are largely visible, symmetrically covering both knees (Figure 14b). The left side of the halo still retains a clear belt-shaped joint bead pattern (Figure 14c). The same band-like beaded pattern is also visible on the right side of the halo of the uppermost Buddha statuette, the outer edge of the halo is adorned with clear parallel radiating flame patterns (Figure 14d), and beneath the left knee of this figure, a relatively clear piece of a petal pattern on the pedestal is visible and is of a style that became common in northern China after unification under the Northern Wei Dynasty (Figure 14e). Therefore, the petal pattern alone refutes the assertion that the flat five-Buddha statuette dates from the late Eastern Han Dynasty, and it also indicates that the flat five-Buddha statuette from the Chengren tomb is from a later date than the standing Buddha statuette.

Figure 14.

Details of the flat five-Buddha statuette ((a). the right arm of the lower-right Buddha statuette, (b). the sleeve cuff of the Buddha statuette in the second row on the right, (c). the left side of the halo of the Buddha statuette in the second row on the right, (d). the right side of the halo of the uppermost Buddha statuette, (e). a petal pattern on the pedestal of the uppermost Buddha statuette, graphic created by the author).

In fact, there are also some Buddha statuettes within the Guanlong region that share the same style as the Buddha figures on the flat five-Buddha statuette. Among them, the Lingtai County Museum 靈臺縣博物館 houses a well-preserved flat nine-Buddha statuette (Wei 2018, p. 1436), where each figure is strikingly similar in appearance (Figure 15) and highly consistent with the images of the Buddha figures on the flat five-Buddha statuette excavated from M3015 in Chengren Village. It is important to note that this consistency is not limited to individual elements, but extends across all aspects of the statuettes. A number of elements display a high degree of similarity, from the facial features and postures of the Buddha figures to the clothing patterns on their arms, the shape and texture of the sleeve cuffs, the detailed representation of the hand mudras, the shape of the halo, the position and form of the band-like joint bead patterns and parallel radiating flame patterns on the halo, and even the shape of the lotus petals on the pedestals.

Figure 15.

The flat nine-Buddha statuette, currently in the Lingtai Museum, and its details (provided by Lingtai Museum. Graphic created by the author).

The flat nine-Buddha statuette in the collection of the Lingtai Museum has a total height of 18.5 cm, and each individual Buddha statuette is the same height as those in the five-Buddha statuette, i.e., approximately 4.9 cm. This statuette was acquired from Xitun Township, Lingtai County 靈臺縣西屯鄉, which is adjacent to the Guanzhong region and has been deeply influenced by the Guanzhong culture, thus belonging to the same cultural sphere. The similarity between these two statuettes is also evident in their special forms; both the five-Buddha and nine-Buddha statuettes are essentially multi-Buddha statuettes composed of many small meditating Buddha figures.

The Palace Museum also has a similar flat multi-Buddha statuette in its collection, consisting of two identical meditating Buddha statuettes and one flying apsara statuette. It is catalogued as Statuette No. 6 in Chinese Gilt Bronze Buddha Statues (Li 1995, p. 24) (Figure 16). The entire statuette is 6.7 cm tall, with each meditating Buddha statuette about 4.9 cm tall, matching the size of the previously mentioned multi-Buddha statuettes. Moreover, the features of each part of the Buddha figures, the shape of the halo, and the decorative patterns closely resemble those on the two previously discussed statuettes. The band-like beaded patterns decorating the halo of these Buddha figures are a prevalent decorative motif in the gilt bronze Buddhist statuettes of the Guanlong region and are rarely found on small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes from elsewhere (Zhang and Wei, forthcoming). This statuette was purchased in Xi’an, and it is highly probable that it also originates from the Guanzhong region, where Xi’an is located. The three flat multi-Buddha statuettes referenced above can be classified as the same type of Buddha statuette; they were manufactured and popularized in close proximity and are likely of a similar age.

Figure 16.

Buddha Statuette No.6 at the Palace Museum (taken from Li 1995).

In terms of the subject matter of the flat five-Buddha statuette, the ancient Qinzhou region, adjacent to Guanzhong, has also yielded small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes with a composition of five Buddhas. The Tianshui Museum 天水市博物館 houses a meditating gilt bronze Buddha statuette with a short-footed couch-style pedestal, on the halo of which, five seated Buddhas are cast (Zhejiang 2018, p. 75) (Figure 17). Similar Buddha statuettes are also owned by private collectors. The consistency of the five-Buddha composition in the Tianshui Museum statuette with that unearthed at Chengren village is no mere coincidence. This can be confirmed through comparison with the nine-Buddha combinations discovered in the Guanzhong and Qinlong regions.

Figure 17.

The Buddha statuette with five seated Buddhas on its halo in the collection of Tianshui Museum (taken from Zhejiang 2018).

In addition to the Buddha statuette with a halo cast with five Buddhas, Tianshui Museum also has a similar meditating gilt bronze Buddha statuette in its collection, with a halo cast with nine Buddhas. There are a considerable number of similar meditating gilt bronze Buddha statuettes with a nine-Buddha combination, with examples unearthed from Xi’an 西安, Zhenyuan 鎮原, and Guyuan 固原, among other places (Zhai 2003, pp. 46–47; Wei and Wu 2003, pp. 16–21; Guyuan 1984, p. 35) (Figure 18). Moreover, there are many such Buddha statuettes spread among public and private collections both in China and abroad (Saburo 1995 [Plates], pp. 55–59). As previously mentioned, the nine-Buddha statuette from Lingtai County and the five-Buddha statuette from Chengren village are also the same type of statuette. It can be seen that both the flat multi-Buddha statuettes and the meditating Buddha statuettes with short-footed couch-style pedestals, which are unique to the Guanzhong and Qinlong regions, feature combinations of five and nine Buddhas. These two types of statuette show a clear corresponding relationship in terms of their Buddha composition.

Figure 18.

Buddha statuettes with nine seated Buddhas on the halo in the Guanlong region ((a–c). taken from Zhejiang 2018, (d). photographed by the author).

Through a comprehensive analysis and comparison of the style, size, origin, form, and subject matter of the five-Buddha statuette from Chengren Village, it can be concluded that this type of multi-Buddha statuette, comprising meditating gilt bronze Buddha statuettes approximately 4.9 cm tall, was a commonly popular type of Buddhist statuette in the Guanzhong and Qinlong regions during a certain historical period.

Next, we will discuss the dating of this type of flat multi-Buddha statuette. Chinese Gilt Bronze Buddha Statues suggests that the flat two-Buddha statuette dates to the first half of the fifth century, but does not give a detailed explanation (Li 1995, p. 24). There is also a very special type of plate-shaped Buddha statuette prevalent in the Guanlong region that can offer relatively reliable evidence for use in dating flat multi-Buddha statuettes. There are a total of five extant plate-shaped Buddha statuettes, four of which are dated. In 1980, a gilt bronze plate-shaped Buddha statuette made by the monks of the Zhuiyuan Temple 追遠寺 in the seventh year of the Taihe era 太和七年 (483 AD) was excavated in the Lianhu District in Xi’an City 西安市蓮湖區. It is generally believed that these statuettes were popular in the Shaanxi and Gansu regions (Li 2016, p. 27; Zhang 2016, p. 261). An undated plate-shaped Buddha statuette collected in Japan has two seated Buddha figures cast on its upper edge that closely resemble those on the flat multi-Buddha statuettes (Jin 2002, p. 399) (Figure 19a). The bottom of this statuette and the pedestal are connected by two complete “C”-shaped twin-dragon head knobs; a similar medallion connection joint can also be found on another plate-shaped Buddha statuette dated to the fourth year of the Yanxing era in the Northern Wei Dynasty 北魏延興四年 (474). Similarly, the Buddha figures on both sides of the flat nine-Buddha statuette from Lingtai County are also connected by a comparable “C”-shaped twin-dragon head knob (Figure 19b). Furthermore, a similar “C”-shaped twin-dragon head image also appears on a copper knocker ring unearthed from a painted coffin tomb from the early Taihe era of the Northern Wei Dynasty in Leizumiao Village, Guyuan 固原雷祖廟村5. The detailed features of the dragons, such as the mouth, the eyes, the ears, the mane under the ears, and even the incised lines and bead patterns on the body, are almost identical. This can serve as additional evidence for use in dating the nine-Buddha statuette from Lingtai.

Figure 19.

Comparative illustration of the undated plate-shaped Buddha statuette and the flat nine-Buddha statuette ((a). taken from Jin 2002, (b). provided by Lingtai Museum. Graphic created by the author).

According to the evolution of the plate-shaped Buddha statuettes, Li Jingjie argued that the undated plate-shaped Buddha statuette mentioned above predates the fourth year of the Yanxing era 延興四年 (474 AD); it is probably close to that of the first year of the Heping era 和平元年 (460 AD) (Li 2016, p. 24). If we adopt a cautious approach, then we could estimate that the creation date of the undated plate-shaped Buddha statuette is between the first year of Heping (460) and the seventh year of Yanxing (474), and it is certainly no later than the creation of the latest-dated plate-shaped Buddha statuette, which is from the seventh year of Taihe (483). This range of dates can also be used as the chronological range for the nine-Buddha statuette from Lingtai.

On the other hand, based on the corresponding subject matter combinations and relationships, the Buddha statuettes with nine-Buddha combinations on their halos unearthed in places such as Xi’an, Zhenyuan, and Guyuan, as mentioned above, can also provide evidence for use in dating flat multi-Buddha statuettes. According to research by Wei Wenbin 魏文斌 and others, this type of seated Buddha statuette was prevalent during the Taihe Period before Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei Dynasty 北魏孝文帝 relocated the capital to Luoyang 洛陽, corresponding to the second phase of the Yungang Grottoes (Wei and Wu 2003, pp. 16–21). Saburo Matsubara 松原三郎 also suggests that these statuettes date back to around 475 AD (Saburo 1995 [Texts], pp. 11–19).

To summarize, the production era of the flat multi-Buddha statuettes in the Guanzhong and Qinlong regions can be dated to the period between the Yanxing era and the early Taihe Period (around 471~484 AD), during the reign of Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei Dynasty. The five-Buddha statuette from Chengren Village, like many similar statuettes, is also likely to have been created during this time.

5. Conclusions

The two small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes unearthed in M3015 in Chengren Village, Xianyang, are not unique. Between the late “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms” and the mid-Northern Wei Dynasty, numerous examples of small gilt bronze Buddha statuettes that are similar, whether in specific features, combinations of forms, or subject matter, have been discovered in the Guanzhong and Qinlong regions.

These statuettes were not original funerary objects for the tomb, but were mixed into at a later period. The specific time and process of their burial, and the motivation behind it, are beyond the scope of this paper. This issue can currently only be addressed through logical reasoning and lacks concrete evidence; it may remain contentious for a long time. The two Buddha statuettes were created at different times. The standing Buddha statuette was likely created in the late “Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms”, around the early 5th century. And the flat five-Buddha statuette was likely created between the Yanxing era and the early Taihe era of Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei Dynasty (around 471~484 AD). Between the two, the five-Buddha statuette is from a later date and can be regarded as the later limit for when these statuettes entered the tomb, meaning that the two statuettes could not have been placed in the tomb earlier than the reign of Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei Dynasty.

Funding

This research was funded by Major Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China “The History of Cultural Exchange between Gandhara and Chinese Civilization (Multi-Volume)” 犍陀羅與中國文明交流史(多卷本), grant number: 20&ZD220.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | On 9 December 2021, the Shaanxi Provincial Cultural Heritage Administration hosted a press conference to announce archaeological discoveries during the year. Following this, numerous media outlets, such as Guangming Daily 光明日報, China Cultural Relics Newspaper 中國文物報, and Shaanxi Daily 陝西日報 all carried special reports on the two gilt bronze Buddhist statuettes, with the content being largely consistent. For more details, see “Shanxi xianyang chutu guonei zuizao jintong foxiang” 陝西咸陽出土國內最早金銅佛像 [The Earliest Gilt Bronze Buddhist Statues Unearthed in China Discovered in Xianyang, Shaanxi]. Guangming Daily 光明日報 2021-12-10, page 09. |

| 2 | For example, on 26 December 2021, the Artistic Research Academy of Sichuan Normal University hosted an academic dialogue titled “Newly Discovered Gilt Bronze Buddha Statues in Xianyang”, in which some scholars raised questions about the dating of the two Buddha statues. Moreover, this new discovery also garnered extensive attention beyond the academic community. On 30 December 2022, Yang Xin 陽新 published an article on the WeChat public account “Taiyang Henda Gumeishu” 太陽很大古美術, conducting a detailed comparative study of these two statuettes with existing early Buddhist statuettes in China, concluding that these two statuettes were likely mixed into the tomb at a later period and date back to the era of the Sixteen Kingdoms. See https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/0LAq9l1218BhC4Olrvyxng (accessed on 4 July 2024). Additionally, from 25–26 February 2022, the Shaanxi Provincial Cultural Heritage Administration, in collaboration with the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), hosted a workshop titled “Discovering the Earliest Gilt Bronze Buddhist Statues in China”. More than ten scholars from the Shaanxi Provincial Cultural Heritage Administration, Hanyangling Museum, UCLA, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, The University of Chicago, Yale University, University of Southern California, and Thammasat University participated in a public online academic discussion, bringing this topic to the attention of the international academic community. The scholars present at the workshop also failed to reach a consensus on the dating and other issues related to these two gilt bronze Buddhist statues. For more details, see Lei, Jie 雷潔 (Lei 2022a) “Discovering the Earliest Gilt Bronze Buddhist Statues in China: Archaeological Inferences” 發現中國最早的金銅佛像——考古的推斷, The Paper: Private History 澎湃新聞·私家歷史. 2022-03-06, https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_16973851 (accessed on 4 July 2024) and Lei, Jie 雷潔 (Lei 2022b) “Discovering the Earliest Gilt Bronze Buddhist Statues in China: Issues in Buddhist History” 發現中國最早的金銅佛像——佛教史的諸問題, The Paper: Private History 澎湃新聞·私家歷史. 2022-03-26, https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_17295519 (accessed on 4 July 2024). |

| 3 | The scientific analysis includes ultra depth of field microscopy, X-ray photograph, SEM-EDS, and metallographic analysis. The results show that the two bronze statuettes were made of lead–tin bronze through mold-casting. See (Li et al. 2022, pp. 123–28). |

| 4 | Isao Kurita’s catalogue alone contains a large number of related statuettes; for further details, see (Isao 1988, pp. 31, 51–52, 59, 74, 76, 78, 97, 110–13, 116–17, 119, 122, 125–28, 213, 254–55). |

| 5 | The tomb dates to around the same period as Cave 9 and Cave 10 of the Yungang Grottoes, i.e., approximately the 10th year of the Taihe era (486 AD); see (Han and Han 1984, p. 47). For detailed arguments, see (Ningxia 1988, pp. 14–15). |

References

- Chen, Huixia 陳慧霞. 1996. Lidai Jintongfo Zaoxiang Tezhan Tulu 歷代金銅佛造像特展圖錄 [A Special Exhibition of Recently Axquired Gild-Bronze Buddhist Images]. Taipei: National Palace Museum in Taipei. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Mengze 崔夢澤. 2024. Xinchu xian xianyang chengrenmu donghan jintong foxiang yanjiu 新出西安咸陽成任墓東漢金銅佛像研究 [Reaserch on the Newly Discovered Bronze Buddha Statues of the Eastern Han Dynasty from the Chengren Tomb in Xianyang, Xian]. Zongjiaoxue Yanjiu 宗教學研究 2: 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Guyuan Wenwuzhan 固原縣文物站. 1984. Guyuanxian xinji gongshe chutu yipi beiwei fojiaozaoxiang 固原縣新集公社出土一批北魏佛教造像 [A batch of Buddhist statues from the Northern Wei was unearthed in Xinji Township, Guyuan County]. Kaogu Yu Wenwu 考古與文物 6: 35. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Kongle 韓孔樂, and Zhaomin Han 韓兆民. 1984. Ningxia guyuan beiweimu qingli jianbao 寧夏固原北魏墓清理簡報 [Excavation Report of Northern Wei Tombs in Guyuan, Ningxia]. Wenwu 文物 6: 47. [Google Scholar]

- He, Zhiguo 何志國. 2023. Xianyang chutu “Donghan qingtong foxiang” xianyi 咸陽出土“東漢青銅佛像”獻疑 [Questioning the Bronze Buddha Statue of the Eastern Han Dynasty from Xianyang]. Zhongyuan Wenwu 中原文物 6: 122–31. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Chunhe 黃春和. 2022. Xianyang chengren mu chutu foxiang de niandia chandi ji xiangguan wenti chutan 咸陽成任墓出土佛像的年代產地及相關問題初探 [Preliminary Exploration of the Date, Origin, and Related Issues of the Buddha Images Unearthed from the Chengren Tomb in Xianyang]. Shoucangjia 收藏家 11: 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Wenkun 黃文昆. 2015. Discussions on Early Archaeology and Buddhist Art in China 中國早期佛教美術考古泛議 [Discussions on Early Archaeology and Buddhist Art in China]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 1: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Isao, Kurita 栗田功. 1988. Gandhāran Art I: The Buddha’s Life Story ガングーラ美術Ⅰ·佛伝. Tokoy: Nigensha. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Shen 金申. 1994. Zhongguo Lidai Jinian Foxiang Tudian 中国历代纪年佛像图典 [Atlas of Chronological Buddhist Statues Through the Dynasties of China]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Shen 金申. 2002. Haiwai Ji Gangtaicang Lidai Foxiang Zhenpin Jinian Tujian 海外及港臺藏曆代佛像珍品紀年圖鑒 [Catalogue of Exquisite Chinese Buddhist Statues from Past Dynasties, Including Collections from Overseas, Hong Kong, and Taiwan]. Taiyuan: Shanxi Renmin Chubans. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Jie 雷潔. 2022a. Faxian Zhongguo Zuizaode Jintong Foxiang: Kaogu de Tuduan. 發現中國最早的金銅佛像——考古的推斷 [Discovering the Earliest Gilt Bronze Buddhist Statues in China: Archaeological Inferences]. The Paper: Private History 澎湃新聞·私家歷史, March 6. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Jie 雷潔. 2022b. Faxian Zhongguo Zuizaode Jintong Foxiang: Fojiao Shi de Zhuwenti. 發現中國最早的金銅佛像——佛教史的諸問題 [Discovering the Earliest Gilt Bronze Buddhist Statues in China: Issues in Buddhist History]. The Paper: Private History 澎湃新聞·私家歷史, March 26. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jianxi 李建西, Anding Shao 邵安定, Junhong Song 宋俊榮, Ming Li 李明, and Zhanrui Zhao 趙占銳. 2022. Xianyang chengren mudi chutu donghan jintong foxiang kexue fenxi 咸陽成任墓地出土東漢金銅佛像科學分析 [The Scientific Analysis of the Bronze Statues from an Eastern Han Tomb at the Chengren Cemetery, Xianyang]. Kaogu Yu Wenwu 考古與文物 1: 123–28. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingjie 李靜傑. 1995. Zhongguo Jintongfo 中國金銅佛 [Chinese Gilt Bronze Buddha Statues]. Beijing: Zongjiao Wenhua Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingjie 李靜傑. 2016. Beiwei jintong foban tuxiang suofanying jiantuoluo wenhua yinsu de dongchuan 北魏金銅佛板圖像所反映犍陀羅文化因素的東傳 [On Gandhara Culture Spreading to the Orient Reflected by the Golden-Bronze Buddha Plates’ Images of Northern Wei Dynasty]. Gugong Bowuyuan Yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 5: 27. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Jianhua 劉建華. 2002. Bweiwei taichang wunian mile tongfoxiang ji xiangguan wenti de tan tao 北魏泰常五年彌勒銅佛像及相關問題的探討 [Discussion on the Maitreya Copper Buddha Statue from the Fifth Year of Taichang era in the Northern Wei Dynasty and Related Issues]. In Subai Xianshen Bazhi Huadan Jinian Wenji 宿白先生八秩華誕紀念文集 [Commemorative Essay Collection for Mr. Su Bai’s 80th Birthday]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Wenwen 李雯雯, and Hu Zhu 朱滸. 2022. Xianyang chengren mudi chutu jintong foxiang fengge yanjiu 咸陽成任墓地出土金銅佛像風格研究 [Study on the Style of Gilt Copper Buddha Statues Unearthed from the Tomb in Chengren Village, Xianyang]. Zhongguo Meishu Yanjiu 中國美術研究 3: 184–91. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Shiping 罗世平. 2010. Zhongguo Meishu Quanji: Zongjiao Diaosu I 中国美术全集:宗教雕塑Ⅰ [The Complete Works of Chinese Art: Volume I—Religious Sculpture]. Hefei: Huangshan Shushe 黄山书社. [Google Scholar]

- Ningxia Guyuan Bowuguan 寧夏固原博物館. 1988. Guyuan Beiweimu Qiguanhua 固原北魏墓漆棺畫 [The Lacquered Coffin Paintings from the Tomb of Northern Wei Dynasty in Guyuan]. Yinchuan: Ningxia Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, Wanli 冉萬里, Ming Li 李明, and Zhanrui Zhao 趙占銳. 2022. Xianyang chengren mudi chutu donghan jintong foxiang yanjiu 咸陽成任墓地出土東漢金銅佛像研究 [Reaserch on the Bronze Buddha Statues from the Eastern Han Tomb at Chengren Cemetery in Xianyang]. Kaogu Yu Wenwu 考古與文物 1: 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rhie, Marylin M. 2002. Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia. Leiden: Brill, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Saburo, Matcubara 松原三郎. 1995. Zhongguo chuqi jintongfo de kaocha 中國初期金銅仏の一考察. In Zhongguo Fojiao Diaoke Shilun 中國佛教彫刻史論 [Discussion on the History of Chinese Buddhist Sculpture]. Yokoy: Yoshikawa Koubunkan. [Google Scholar]

- Shaanxi Academy Archaeology 陝西省考古研究院. 2022. Shanxi xiangyang chengren mudi donghan jianzumu fajue jianbao 陝西咸陽成任墓地東漢家族墓發掘簡報 [Preliminary Report of the Excavationof the Eastern Han Family Tombs at the Chengren Cemetery in Xianyang, Shaanxi]. Kaogu Yu Wenwu 考古與文物 1: 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Dehai 孫德海, Mingyuan Cheng 程明遠, and Hui Chen 陳惠. 1959. Shijia zhuang shi beisongcun qingli le liangzuo hanmu 石家莊市北宋村清理了兩座漢墓 [Two Han Dynasty Tombs were Excavated in Beisong Village, Shijiazhuang City]. Wenwu 文物 1: 55. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Shou 魏收. 1974. Weishu 魏書. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Wenbin 魏文斌. 2018. Gansu Shengzhi: Wenwuzhi 甘肅省志·文物志 [Gansu Province Annals: Cultural Relics Volume]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Wenbin 魏文斌, and Hong Wu 吳葒. 2003. Gansu zhengyuanxian bowuguan cang beiwei qingtong zaoxiang ji youguan wenti 甘肅鎮原縣博物館藏北魏青銅造像及有關問題 [A Bronze Sculpture of The Northern Wei Dynasty Treasured in The Museum of Zhenyuan County And Some Relative Questions]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 3: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Xin 陽新. 2021. Guanyu Xianyang Danghan Muchutu Tongfo De Niandai Fenxi 關於咸陽東漢墓出土銅佛的年代分析. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/0LAq9l1218BhC4Olrvyxng (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Yao, Chongxin 姚崇新. 2022. Guanyu xianyang chengren donghanmu chutu jintong foxiang de jige wenti 關於咸陽成任東漢墓出土金銅佛像的幾個問題 [Several Questions about the Gilt Bronze Buddha Statues Unearthed from the Tomb of Eastern Han Dynasty at Chengren in Xianyang]. Wenbo Xuekan 文博學刊 2: 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Chunling 翟春玲. 2003. Xi’an chutu beiwei tongfo zaoxiang yanjiu 西安出土北魏銅佛造像研究 [Research on the Bronze Buddha Statues of Northern Wei Dynasty Unearthed from Xi’an]. Wenbo 文博 5: 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Cong 張聰. 2016. Beiwei tongzhu foban kaolun 北魏銅鑄佛板考論 [An Examination and Discussion of the Gilt Bronze Buddha Plates’ Images of Northern Wei Dynasty]. In Meishuxue Yanjiu Vol. 5 美術學研究 5. Nanjing: Dongnan Daxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Liming 張利明. 2024. Hanjin Zhongguo Yu Guishuang Wenming: Yi Chutu Cailiao Wei Zhongxin 漢晉中國與貴霜文明——以出土材料為中心 [China and the Kushan Civilization from the Western Han to the Eastern Jin Dynasty: Centered on Excavated Materials]. Ph.D. dissertation, Zhejiang Daxue 浙江大学, Zhejiang, China; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Liming 張利明, and Wenbin Wei 魏文斌. Forthcoming. Beiwei zhongqi guanlong diqu xiaoxing jintong fojiao zaoxiang yanjiu: Jianlun chengren donghanmu chutu jintong foxiang 北魏中期關隴地區小型金銅佛教造像研究——兼談成任東漢墓出土金銅佛像. Wenwu 文物.

- Zhejiang Museum 浙江省博物館. 2018. Foying Lingqi: Shiliuguo Zhi Wudai Fojiao Fintong Zaoxiang 佛影靈奇:十六國至五代佛教金銅造像 [Gilt Bronze Buddhist Statues from the Sixteen Kingdoms to the Five Dynasties Period]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).